CHAPTER 7

Adding Server-Side TLS 1.0 Support

The previous chapter examined the TLS protocol in detail from the perspective of the client. This chapter examines the server's role in the TLS exchange. Although you should have a pretty good handle by now on what's expected of the server, the implementation includes a few gotchas that you should be aware of.

The good news is that you can reuse most of the code from the previous chapter; the supporting infrastructure behind encrypting and authenticating is exactly the same for the server as for the client. For the most part, implementing the server's view of the handshake involves sending what the client received and receiving what the client sent. After the handshake is complete, tls_send, tls_recv, and tls_shutdown work exactly as they do on the client side.

Implementing the TLS 1.0 Handshake from the Server's Perspective

You need to have a way to verify the server-side code, so add HTTPS support to the simple web server developed in Chapter 1. The startup and listen routine doesn't change at all. Of course, it's listening on port 443 instead of port 80, but otherwise, the main routine in Listing 7-1 is identical to the one in Listing 1-18.

Listing 7-1: "ssl_webserver.c" main routine

#define HTTPS_PORT 443 ... local_addr.sin_port = htons( HTTPS_PORT ); ... while ( ( connect_sock = accept( listen_sock, ( struct sockaddr * ) &client_addr, &client_addr_len ) ) != −1 ) { process_https_request( connect_sock ); }

As you can see, there's nothing TLS-specific here; you're just accepting connections on a different port.

process_https_request is just like process_http_request, except that it starts with a call to tls_accept in Listing 7-2.

Listing 7-2: "ssl_webserver.c" process_https_request

static void process_https_request( int connection )

{

char *request_line;

TLSParameters tls_context;

if ( tls_accept( connection, &tls_context ) )

{

perror( "Unable to establish SSL connection" );

}

else

{

request_line = read_line( connection, &tls_context );

if ( strncmp( request_line, "GET", 3 ) )

{

// Only supports "GET" requests

build_error_response( connection, 400, &tls_context );

}

else

{

// Skip over all header lines, don't care

while ( strcmp( read_line( connection, &tls_context ), "" ) )

{

printf( "skipped a header line\n" );

}

build_success_response( connection, &tls_context );

}

tls_shutdown( connection, &tls_context );

} #ifdef WIN32 if ( closesocket( connection ) == −1 ) #else if ( close( connection ) == −1 ) #endif { perror( "Unable to close connection" ); } }

And, of course, read_line, build_error_response, and build_success_response must be updated to invoke tls_send and tls_recv instead of send and recv as in Listing 7-3.

Listing 7-3: "ssl_webserver.c" send and read modifications

char *read_line( int connection, TLSParameters *tls_context )

{

...

while ( ( size = tls_recv( connection, &c, 1, 0, tls_context ) ) >= 0 )

{

...

static void build_success_response( int connection, TLSParameters *tls_context )

{

...

if ( tls_send( connection, buf, strlen( buf ), 0, tls_context ) < strlen( buf ) )

...

static void build_error_response( int connection,

int error_code,

TLSParameters *tls_context )

{

if ( tls_send( connection, buf, strlen( buf ), 0, tls_context ) < strlen( buf ) )

{

Other than tls_accept, all of the support functions referenced here were implemented in Chapter 6 and can be used exactly as is.

Notice the HTTPS protocol at work. The server accepts a connection and then immediately waits for a client hello message; if any attempt is made to send any other data, an error occurs. Although this is not strictly required by the TLS protocol itself, it is common when integrating TLS into an existing protocol.

tls_accept is a mirror image of tls_connect; it must wait for a client hello. (Remember that the client must always initiate the TLS handshake.) After the hello is received, the server responds with hello, certificate, and hello done messages back-to-back, waits for the client's change cipher-spec and finished message, sends its own, and returns. This is shown in Listing 7-4.

Listing 7-4: "tls.c" tls_accept

int tls_accept( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters ) { init_parameters( parameters ); parameters->connection_end = connection_end_server; new_md5_digest( ¶meters->md5_handshake_digest ); new_sha1_digest( ¶meters->sha1_handshake_digest ); // The client sends the first message parameters->got_client_hello = 0; while ( !parameters->got_client_hello ) { if ( receive_tls_msg( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) < 0 ) { perror( "Unable to receive client hello" ); send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 1; } } if ( send_server_hello( connection, parameters ) ) { send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 2; } if ( send_certificate( connection, parameters ) ) { send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 3; } if ( send_server_hello_done( connection, parameters ) ) { send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 4; } // Now the client should send a client key exchange, change cipher spec, and // an encrypted "finalize" message parameters->peer_finished = 0; while ( !parameters->peer_finished ) { if ( receive_tls_msg( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) < 0 )

{ perror( "Unable to receive client finished" ); send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 5; } } // Finally, send server change cipher spec/finished message if ( !( send_change_cipher_spec( connection, parameters ) ) ) { perror( "Unable to send client change cipher spec" ); send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 6; } // This message will be encrypted using the newly negotiated keys if ( !( send_finished( connection, parameters ) ) ) { perror( "Unable to send client finished" ); send_alert_message( connection, handshake_failure, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return 7; } // Handshake is complete; now ready to start sending encrypted data return 0; }

This listing should be easy to follow if you understood tls_connect (Listing 6-7). It starts by initializing its own handshake digest pair so that it can validate the final finished message as described in Chapter 6. It also references three new TLSParameter members that you haven't seen yet:

- connection_end: This requires a bit of explanation. Recall from Listing 6-37 that, when calculating keys, the first mac-length bytes were the client's MAC secret, and the next mac-length bytes were the server's. If you want to reuse the same code to compute keys, you must keep track of whether you are the client or the server, to know which keys to put into the active_send_parameters and which to put into the active_recv_parameters. Because tls_accept is only invoked by a TLS server, and tls_connect is only invoked by a TLS client, it's safe to set this flag here to control common functions.

- got_client_hello: Serves the same purpose in tls_accept as got_server_hello did in tls_connect. Each call to receive_tls_message processes the next available TLS message, regardless of what type it is — alert, data, handshake — so you must keep processing messages until you get the one you were expecting.

- peer_finished. The same as server_finished. In fact, you should delete server_finished from the TLSParameters structures and rename it peer_finished; the finished messages are identical whether they came from the client or from the server, so handling them is exactly the same either way.

Define these new members in 7-5.

Listing 7-5: "tls.h" TLSParameters with server-side support

typedef enum { connection_end_client, connection_end_server } ConnectionEnd;

typedef struct

{

ConnectionEnd connection_end;

master_secret_type master_secret;

random_type client_random;

random_type server_random;

ProtectionParameters pending_send_parameters;

ProtectionParameters active_send_parameters;

ProtectionParameters pending_recv_parameters;

ProtectionParameters active_recv_parameters;

public_key_info server_public_key;

dh_key server_dh_key;

// Internal state

int got_client_hello;

int server_hello_done;

int peer_finished;

digest_ctx md5_handshake_digest;

digest_ctx sha1_handshake_digest;

char *unread_buffer;

int unread_length;

}

TLSParameters;

Change references from server_finished to peer_finished and change the verify data label depending on the connection end in Listing 7-6.

Listing 7-6: "tls.c" peer_finished

static unsigned char *parse_finished( unsigned char *read_pos,

int pdu_length,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned char verify_data[ VERIFY_DATA_LEN ]; parameters->peer_finished = 1; compute_verify_data( parameters->connection_end == connection_end_client ? "server finished" : "client finished", parameters, verify_data ); ... int tls_connect( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters ) { ... parameters->peer_finished = 0; while ( !parameters->peer_finished ) { if ( receive_tls_msg( connection, NULL, 0, parameters ) < 0 )

And finally update the initialization routine in Listing 7-7.

Listing 7-7: "tls.c" init_parameters

static void init_parameters( TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

// Internal state

parameters->got_client_hello = 0;

parameters->server_hello_done = 0;

parameters->peer_finished = 0;

...

int tls_connect( int connection,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

init_parameters( parameters );

parameters->connection_end = connection_end_client;

TLS Client Hello

Of course, a client hello can be received by receive_tls_message now, so it must be added in Listing 7-8.

Listing 7-8: "tls.c" receive_tls_message with client_hello

static int receive_tls_msg( int connection,

char *buffer,

int bufsz,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

switch ( handshake.msg_type )

{

... // Server-side messages case client_hello: if ( parse_client_hello( read_pos, handshake.length, parameters ) == NULL ) { send_alert_message( connection, illegal_parameter, ¶meters->active_send_parameters ); return −1; } read_pos += handshake.length; break; ...

Parsing and processing the client hello message involves, at a bare minimum, selecting one of the offered cipher suites. The easiest way to do this is to cycle through the list of cipher suites that the client offers and select the first one that the server understands. Note that this is not necessarily the best strategy; ideally the server would select the strongest suite that both sides understand. On the other hand, client designers can meet server designers halfway and sort the cipher suite list by cipher strength so that the server's cipher selection code can be simpler. The specification states that the client hello should include its "favorite cipher first." However, there are no suggestions on what criteria it ought to use in selecting a favorite. This does imply that the server probably ought to select the first one it recognizes, but does not actually mandate this.

Parsing the client hello message is shown in Listing 7-9.

Listing 7-9: "tls.c" parse_client_hello

static char *parse_client_hello( char *read_pos,

int pdu_length,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

int i;

ClientHello hello;

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.client_version.major,

( void * ) read_pos, 1 );

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.client_version.minor,

( void * ) read_pos, 1 );

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.random.gmt_unix_time,

( void * ) read_pos, 4 );

// *DON'T* put this in host order, since it's not used as a time! Just

// accept it as is

read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) hello.random.random_bytes, ( void * ) read_pos, 28 ); read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.session_id_length, ( void * ) read_pos, 1 ); hello.session_id = NULL; if ( hello.session_id_length > 0 ) { hello.session_id = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( hello.session_id_length ); read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) hello.session_id, ( void * ) read_pos, hello.session_id_length ); // TODO if this is non-empty, the client is trying to trigger a restart } read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.cipher_suites_length, ( void * ) read_pos, 2 ); hello.cipher_suites_length = ntohs( hello.cipher_suites_length ); hello.cipher_suites = ( unsigned short * ) malloc( hello.cipher_suites_length ); read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) hello.cipher_suites, ( void * ) read_pos, hello.cipher_suites_length ); read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) &hello.compression_methods_length, ( void * ) read_pos, 1 ); hello.compression_methods = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( hello.compression_methods_length ); read_pos = read_buffer( ( void * ) hello.compression_methods, ( void * ) read_pos, hello.compression_methods_length );

This reuses the read_buffer function from Listing 6-21 to fill in the ClientHello structure.

After this structure is filled in, the server must select a cipher suite.

for ( i = 0; i < hello.cipher_suites_length; i++ )

{

hello.cipher_suites[ i ] = ntohs( hello.cipher_suites[ i ] );

if ( hello.cipher_suites[ i ] < MAX_SUPPORTED_CIPHER_SUITE &&

suites[ hello.cipher_suites[ i ] ].bulk_encrypt != NULL )

{

parameters->pending_recv_parameters.suite = hello.cipher_suites[ i ];

parameters->pending_send_parameters.suite = hello.cipher_suites[ i ];

break;

}

}

if ( i == MAX_SUPPORTED_CIPHER_SUITE )

{

return NULL;

}

parameters->got_client_hello = 1;

The specification isn't clear on exactly what the server should do if the client doesn't offer any supported cipher suites; OpenSSL just closes the connection without sending an alert. This implementation returns NULL here, which ultimately triggers a handshake failed alert back in the tls_accept code.

Finally, record the client random for the key exchange step and clean up.

memcpy( ( void * ) parameters->client_random, &hello.random.gmt_unix_time, 4 );

memcpy( ( void * ) ( parameters->client_random + 4 ),

( void * ) hello.random.random_bytes, 28 );

free( hello.cipher_suites );

free( hello.compression_methods );

if ( hello.session_id )

{

free( hello.session_id );

}

return read_pos;

}

TLS Server Hello

Sending a server hello is pretty much the same as sending a client hello; the only difference between the two structures is that the server hello only has space for one cipher suite and one compression method. This is shown in Listing 7-10.

Listing 7-10: "tls.c" send_server_hello

static int send_server_hello( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters )

{

ServerHello package;

int send_buffer_size;

char *send_buffer;

void *write_buffer;

time_t local_time;

package.server_version.major = 3;

package.server_version.minor = 1;

time( &local_time );

package.random.gmt_unix_time = htonl( local_time );

// TODO - actually make this random.

// This is 28 bytes, but server random is 32 - the first four bytes of

// "server random" are the GMT unix time computed above.

memcpy( parameters->server_random, &package.random.gmt_unix_time, 4 );

memcpy( package.random.random_bytes, parameters->server_random + 4, 28 );

package.session_id_length = 0;

package.cipher_suite = htons( parameters->pending_send_parameters.suite );

package.compression_method = 0;

send_buffer_size = sizeof( ProtocolVersion ) +

sizeof( Random ) + sizeof( unsigned char ) + ( sizeof( unsigned char ) * package.session_id_length ) + sizeof( unsigned short ) + sizeof( unsigned char ); write_buffer = send_buffer = ( char * ) malloc( send_buffer_size ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &package.server_version.major, 1 ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &package.server_version.minor, 1 ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &package.random.gmt_unix_time, 4 ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &package.random.random_bytes, 28 ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &package.session_id_length, 1 ); if ( package.session_id_length > 0 ) { write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * )package.session_id, package.session_id_length ); } write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &package.cipher_suite, 2 ); write_buffer = append_buffer( write_buffer, ( void * ) &package.compression_method, 1 ); assert( ( ( char * ) write_buffer - send_buffer ) == send_buffer_size ); send_handshake_message( connection, server_hello, send_buffer, send_buffer_size, parameters ); free( send_buffer ); return 0; }

The selected cipher suite is copied from pending_send_parameters and bundled off to the client. Notice that the session ID sent by this implementation is empty; this is permissible per the specification and indicates to the client that this server either does not support session resumption or does not intend to resume this session.

TLS Certificate

After the server hello is sent, the server should send a certificate, if the cipher spec calls for one (which is the case in the most common cipher specs). Because the certificate normally must be signed by a certificate authority in order to be accepted, it's usually pre-generated and signed, and it must be loaded from disk to be presented to the user. There's no realistic way to generate a new certificate with a new public key "on the fly."

Recall that the certificate handshake message was the length of the chain, followed by the length of the certificate, followed by the certificate, followed by (optionally) another length of a certificate/certificate, and so on. The simplest case is a certificate chain consisting of one certificate, so the certificate must be loaded from disk, the length must be checked, prepended twice, and the whole array serialized as a TLS handshake message. This is shown in Listing 7-11.

Listing 7-11: "tls.c" send_certificate

static int send_certificate( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters )

{

short send_buffer_size;

unsigned char *send_buffer, *read_buffer;

int certificate_file;

struct stat certificate_stat;

short cert_len;

if ( ( certificate_file = open( "cert.der", O_RDONLY ) ) == −1 )

{

perror( "unable to load certificate file" );

return 1;

}

if ( fstat( certificate_file, &certificate_stat ) == −1 )

{

perror( "unable to stat certificate file" );

return 1;

}

// Allocate enough space for the certificate file, plus 2 3-byte length

// entries.

send_buffer_size = certificate_stat.st_size + 6;

send_buffer = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( send_buffer_size );

memset( send_buffer, '\0', send_buffer_size );

cert_len = certificate_stat.st_size + 3;

cert_len = htons( cert_len );

memcpy( ( void * ) ( send_buffer + 1 ), &cert_len, 2 );

cert_len = certificate_stat.st_size;

cert_len = htons( cert_len );

memcpy( ( void * ) ( send_buffer + 4 ), &cert_len, 2 );

read_buffer = send_buffer + 6;

cert_len = certificate_stat.st_size;

while ( ( read_buffer - send_buffer ) < send_buffer_size )

{

int read_size;

read_size = read( certificate_file, read_buffer, cert_len );

read_buffer += read_size; cert_len -= read_size; } if ( close( certificate_file ) == −1 ) { perror( "unable to close certificate file" ); return 1; } send_handshake_message( connection, certificate, send_buffer, send_buffer_size, parameters ); free( send_buffer ); return 0; }

This loads the file cert.der from the current directory into memory, builds a certificate handshake message, and sends it on. Notice the use of fstat to allocate a buffer of exactly the right size for the certificate file, along with two three-byte length fields. The first length field is three more than the second because it includes the second length in its count. Of course, all of the lengths need to be given in network, not host, order. Although there's no three-byte integral type, it's doubtful that a certificate is going to be greater than 65,536 bytes in length, so this code just assumes two byte lengths and pads with an extra 0 to satisfy the formatting requirements.

You can almost certainly see an obvious performance improvement here; nothing in this packet changes from one handshake to the next. Although the code as presented here permits the server administrator to update the certificate without a server restart, the performance hit of loading the entire thing from file to satisfy every single HTTP connection is probably not worth this flexibility. This message ought to be cached in memory and sent from cache after it's generated the first time.

TLS Server Hello Done

As you can see from Listing 7-12, there's not much to the server hello done message:

Listing 7-12: "tls.c" send_server_hello_done

static int send_server_hello_done( int connection, TLSParameters *parameters )

{

send_handshake_message( connection, server_hello_done, NULL, 0, parameters );

return 0;

}

TLS Client Key Exchange

If you look back at Listing 7-4, you see that after the server sends the hello done message, it waits for the client to respond with a key exchange message. This should contain either an RSA-encrypted premaster secret or the last half of a Diffie-Hellman handshake, depending on the key exchange method chosen. In general, the server certificate is expected to have contained enough information for the client to do so. (You see in the next chapter what happens if this is not the case.)

So add the client_key_exchange message to receive_tls_message in Listing 7-13.

Listing 7-13: "tls.c" receive_tls_msg with client_key_exchange

static int receive_tls_msg( int connection,

char *buffer,

int bufsz,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

switch ( handshake.msg_type )

{

...

case client_key_exchange:

read_pos = parse_client_key_exchange( read_pos, handshake.length,

parameters );

if ( read_pos == NULL )

{

send_alert_message( connection, illegal_parameter,

¶meters->active_send_parameters );

return −1;

}

break;

parse_client_key_exchange reads the premaster secret, expands it into a master secret and then into key material, and updates the pending cipher spec. Remember that the pending cipher spec cannot be made active until a change cipher spec message is received.

TLS 1.0 supports two different key exchange methods: RSA and Diffie-Hellman. To process an RSA client key exchange, the server must use the private key to decrypt the premaster secret that the client encrypts and sends. To process a DH client key exchange, the server must compute z = Yca%p; Yc will have been sent in the client key exchange message. However, the server must have sent g, p, and Ys = ga%p in the first place. Although there's a provision in the X.509 specification to allow the server to send this information in the certificate itself, I'm not aware of any software that generates a Diffie-Hellman certificate. In fact, the specification for Diffie-Hellman certificates puts p and g in the certificate, which makes perfect sense, but it also puts Ys in the certificate. Because the whole certificate must be signed by a certificate authority, this means that the corresponding secret value a must be used over and over for multiple handshakes; ideally, you'd want to select a new one for each connection.

Does this mean that Diffie-Hellman key exchange is never used in TLS? It doesn't, but it does mean that it's usually used in a slightly more complex way, which is examined in the next chapter. This section instead simply focuses on the conceptually simpler RSA key exchange.

RSA Key Exchange and Private Key Location

RSA key exchange, then, consists of loading the private key corresponding to the public key previously transmitted in the certificate message, decrypting the client key exchange message, and extracting the premaster key. After this has been done, the compute_master_secret and calculate_keys functions from the previous chapter can be used to complete the key exchange (with one minor difference, detailed later, to account for the fact that this is now the server and the read and write keys must be swapped). You know how RSA decryption works; the rsa_decrypt function was developed in Listing 3-20; the padding used by TLS is the same PKCS #1.5 padding implemented there.

However, where does the private key come from in the first place? It's obviously not in the certificate. Recall from Chapter 5 that when you generated your own test self-signed certificate, you actually output two files: cert.der and key.der. key.der contained the private key. A DER-encoded file is a binary file that you can't read without special software, but a PEM (Base64-encoded) key file — which is actually the default in OpenSSL if you don't specifically ask for DER — can be loaded in a standard text editor.

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY----- Proc-Type: 4,ENCRYPTED DEK-Info: DES-EDE3-CBC,BD1FF235EA6104E1 rURbzE1gnHP0Pcq6SeXvMeP6b5pNmJSpJxCZtuBkC0iTNwRRwICcv0pVNTgkutlU sCnstPyVh/JRU94KQKS0e471Jsq8FKFYqhpDuu1gq7eUGnajFnIh2UvNASVSit6i 6VpJAAs8y1wrt93FfiCMyKiYYGYAOEaE2paDJ4E8zjyVB253BoXDY4PUHpuZDQpL Oxd2mplnTI+5wLomXwW4hjRpX61xfg7ed2RKw00jSx89dkqTgI3jv2VoYqzO88Rb EnQp+2+iSEo+CYvhO26c7c12hGzW0P0fE5olOYnUv5WFPnjBmheWRkAj+K2eeS6w qMTsv1OzKR02gxMWtlJQc2JmnUCfypjTcf9FSGHQKaPSDqbs/1/m+U9DzuzD6NUH /EUWR6m1WxQiORzDUtHrTZ3tJmuGGUEhpqIjpFsL//0= -----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

As the headers indicate, this file is encrypted by default; if you recall, you were prompted for a password before this was generated.

OpenSSL does have an option to write an encrypted RSA private key file in plaintext.

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ openssl rsa -in key.pem -out key_decoded.pem writing RSA key

Now the contents of the same key are output in a nice, neat, PEM-encoded ASN.1 structure like the ones you're used to.

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY----- MIIBOwIBAAJBALGybTND0yjFYJBkXg3cFpYy/C76CFtoqOAyLEjH8RRcPCt6CsTo bxaDC1Lmdaxddti4fbpRG+RPS8gVeCrzvwECAwEAAQJBAJrPX+Oxy11R1/bz+h0J CYSBlsM2geFhJP9ttrcRui6JWQlbEHHQiF1OI9sedv6hDbgynUKdh+Lgo4KHzCTD OYECIQDZ/iNMPqXJDNBd8JBHNsJIqU+tNWPS7wjvp/ivcCcVDQIhANCtu6MGz9tQ S7DkyIYQxuvtxFQsIzir62b6yx2KV7zFAiBatPrvEOpfHCvfyufeGhUBsyHqStr8 vGYVgulh5uL8SQIgVCdLvQHZPutRquOITjBj1+8JtpwaFBeYle3bjW0l1rUCIQDV dUNImB3h18TEB3RwSFoTufh+UlaqBHnXLR8HiTPs6g== -----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

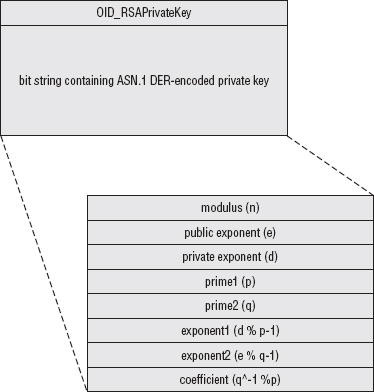

To read and use this, it's just a matter of writing code to parse it and extract the private key exponent. This is shown in Listing 7-14.

Listing 7-14: "privkey.c" parse_private_key

/**

* Parse the modulus and private exponent from the buffer, which

* should contain a DER-encoded RSA private key file. There's a

* lot more information in the private key file format, but this

* app isn't set up to use any of it.

* This, according to PKCS #1 (note that this is not in pkcs #8 format), is:

* Version

* modulus (n)

* public exponent (e)

* private exponent (d)

* prime1 (p)

* prime2 (q)

* exponent1 (d mod p-1)

* exponent2 (d mod q-1)

* coefficient (inverse of q % p)

* Here, all we care about is n & d.

*/

int parse_private_key( rsa_key *privkey,

const unsigned char *buffer,

int buffer_length )

{

struct asn1struct private_key;

struct asn1struct *version;

struct asn1struct *modulus;

struct asn1struct *public_exponent;

struct asn1struct *private_exponent;

asn1parse( buffer, buffer_length, &private_key );

version = ( struct asn1struct * ) private_key.children;

modulus = ( struct asn1struct * ) version->next;

// Just read this to skip over it

public_exponent = ( struct asn1struct * ) modulus->next;

private_exponent = ( struct asn1struct * ) public_exponent->next;

privkey->modulus = malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); privkey->exponent = malloc( sizeof( huge ) ); load_huge( privkey->modulus, modulus->data, modulus->length ); load_huge( privkey->exponent, private_exponent->data, private_exponent->length ); asn1free( &private_key ); return 0; }

This is a regular ASN.1 parsing routine of the kind examined in Chapter 5. It takes as input a DER-encoded buffer that it parses and uses to fill out the privkey argument, a pointer to an rsa_key structure. Remember that an RSA private key is structurally no different than an RSA public key, so the same structure is used to represent both here. Notice that the input is DER-encoded; the caller must ensure either that the file is loaded from the disk that way or that it's passed through the pem_decode routine from Listing 5-7 before being passed to parse_private_key.

The private key structure, as indicated by the comments to this function, contains quite a bit more information than just the modulus and the private exponent; these numbers in theory could be used to support a more optimized rsa_decrypt routine than the one presented in Chapter 3.

If you want to see this in action, you can put together a test main routine as shown in Listing 7-15.

Listing 7-15: "privkey.c" test main routine

#ifdef TEST_PRIVKEY

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] )

{

rsa_key privkey;

unsigned char *buffer;

int buffer_length;

if ( argc < 3 )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Usage: %s [-pem|-der] <rsa private key file>\n", argv[ 0 ] );

exit( 0 );

}

if ( !( buffer = load_file_into_memory( argv[ 2 ], &buffer_length ) ) )

{

perror( "Unable to load file" );

exit( 1 );

}

if ( !strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-pem" ) )

{

// XXX this overallocates a bit, since it sets aside space for markers, etc.

unsigned char *pem_buffer = buffer; buffer = (unsigned char * ) malloc( buffer_length ); buffer_length = pem_decode( pem_buffer, buffer ); free( pem_buffer ); } parse_private_key( &privkey, buffer, buffer_length ); printf( "Modulus:" ); show_hex( privkey.modulus->rep, privkey.modulus->size ); printf( "Private Exponent:" ); show_hex( privkey.exponent->rep, privkey.exponent->size ); free( buffer ); return 0; } #endif

This relies on the simple utility function load_file_into_memory shown in Listing 7-16.

Listing 7-16: "file.c" load_file_into_memory

/**

* Read a whole file into memory and return a pointer to that memory chunk,

* or NULL if something went wrong. Caller must free the allocated memory.

*/

char *load_file_into_memory( char *filename, int *buffer_length )

{

int file;

struct stat file_stat;

char *buffer, *bufptr;

int buffer_size;

int bytes_read;

if ( ( file = open( filename, O_RDONLY ) ) == −1 )

{

perror( "Unable to open file" );

return NULL;

}

// Slurp the whole thing into memory

if ( fstat( file, &file_stat ) )

{

perror( "Unable to stat certificate file" );

return NULL;

}

buffer_size = file_stat.st_size;

buffer = ( char * ) malloc( buffer_size );

if ( !buffer ) { perror( "Not enough memory" ); return NULL; } bufptr = buffer; while ( ( bytes_read = read( file, ( void * ) buffer, buffer_size ) ) ) { bufptr += bytes_read; } close( file ); if ( buffer_length != NULL ) { *buffer_length = buffer_size; } return buffer; }

Supporting Encrypted Private Key Files

If you run privkey on the previously generated private key file, you see the modulus and private exponent of your RSA key:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ ./privkey -pem key_decoded.pem Modulus:b1b26d3343d328c56090645e0ddc169632fc2efa085b68a8e0322c48c7f1145c3c2 b7a0ac4e86f16830b52e675ac5d76d8b87dba511be44f4bc815782af3bf01 Private Exponent:9acf5fe3b1cb5d51d7f6f3fa1d0909848196c33681e16124ff6db6b711ba2e8959 095b1071d0885d4e23db1e76fea10db8329d429d87e2e0a38287cc24c33981

Still, it seems a shame to require that the server user keep the private key stored in plaintext on a disk somewhere. As you can see from the header on the original, encrypted key file, this is encrypted using DES, which you have code to decrypt. Why not go ahead and implement the code to decrypt the encrypted file?

The file, by default, starts with two bits of information:

Proc-Type: 4,ENCRYPTED DEK-Info: DES-EDE3-CBC,BD1FF235EA6104E1

First, the Proc-Type tells you that the file is encrypted. The DEK-Info gives you the encryption algorithm, followed by an initialization vector.

Note that the key contents themselves are PKCS #1 formatted, but the extra header information is OpenSSL/PEM-specific. In fact, if you use OpenSSL to save the key file itself in DER format, you lose the encryption. Because there's no way to communicate the required initialization vector and encryption algorithm, OpenSSL saves you from shooting yourself in the foot and always stores a DER-encoded key file unencrypted, even if you ask for encryption.

A more standardized format, PKCS #8, describes essentially the same information. Although OpenSSL supports the format, there's no way to generate a key file in PKCS #8 format on an initial certificate request. You can convert an OpenSSL to a PKCS #8 private key via:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ openssl pkcs8 -topk8 -in key.der -out key.pkcs8 \ -outform der Enter pass phrase for key.der: Enter Encryption Password: Verifying - Enter Encryption Password:

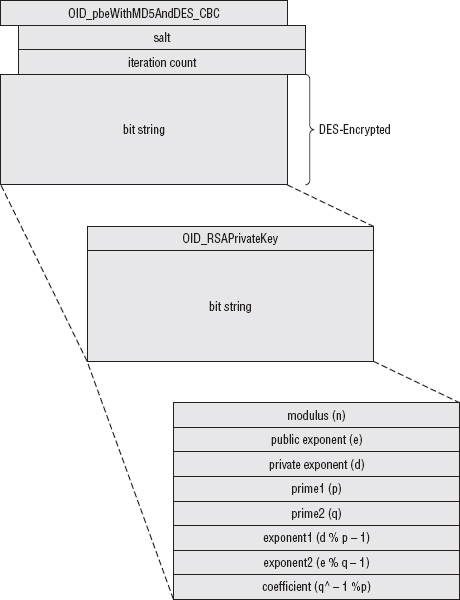

This, by default, encrypts the file using DES; other encryption options are possible, of course. The output is a triply nested ASN.1 DER encoded structure. At the bottom layer of nesting is, of course, the PKCS #1-formatted private key, which the parse_private_key routine of Listing 7-14 can parse correctly. That structure is bit-string encoded and wrapped up as shown in Figure 7-1 in another structure that includes an OID identifying the type of private key — for example, to allow a non-RSA private key, such as DSA, to be included instead.

This whole structure is bit-string encoded, encrypted, and wrapped up in the final, third, ASN.1 structure shown in Figure 7-2 that indicates the encryption method used and enough information to decrypt it before processing. This section bears a bit more explanation.

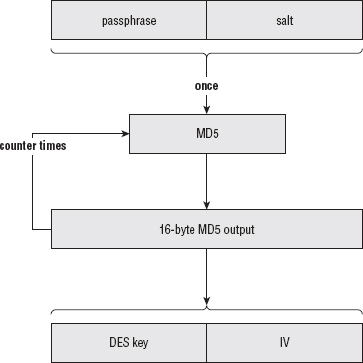

Recall from Chapter 2 that you examined examples of symmetric encryption where a passphrase such as "password" or "encrypt_thisdata" was used as a key input to the encryption algorithms. However, using human-readable text such as this is actually a bad idea when you want to protect data. An attacker knows that the keyspace is limited to the printable-ASCII character set that the user can type on the keyboard. However, you can't exactly require your users to type characters not available on their keyboards either. PKCS #5 describes a solution to this conundrum called password-based encryption (PBE). The idea here is to take the user's input and feed it into a one-way hash function to securely generate a key whose bits are far better distributed than the limited range of the available printable-ASCII character set.

By itself, this doesn't accomplish anything, though. An attacker can still easily mount a dictionary attack on the one-way hash function; the rainbow tables examined in Chapter 4 are perfect for this. Not only is the user's typed input fed into the hash function to generate the keying material, a salt is added to this to thwart dictionary attacks.

However, as you recall, salts/initialization vectors must be distributed non-securely so that both sides know what they are, and PKCS #5 is no exception. Therefore, a determined attacker (and remember we're talking about protecting the keys to the kingdom — the server's private key — here) could still mount a dictionary attack using the unencrypted salt value. He couldn't take advantage of a pre-computed rainbow table, but still, the input space of printable-ASCII characters is far smaller than the entire space of potential hash inputs. Especially considering that users generally pick bad passwords that follow the typing and spelling conventions of their native spoken languages, the attacker can probably mount an offline attack in a few weeks to a month. To slow the attacker down a bit, PKCS #5 finally mandates that the output from the first hash be rehashed and the output of that hash be rehashed, over and over again, up to a specified iteration count. Typically this is a large number, in the thousands – it's not a big deal for somebody with access to the correct passphrase to do a few thousand hashes, but it is a big deal for an attacker who has a large key space to search through. Finally, after all that hashing, the key material is taken from the final resultant hash value.

The top-level PKCS #8 structure indicates what encryption algorithm was used to encrypt the actual private key data — for instance "password-based encryption using the MD5 hash function and the DES encryption function." In the case of DES with MD5, because MD5 produces 16 bytes of output, the DES key is the first eight bytes of this output, and the initialization vector is the last eight bytes.

Thus, the final PKCS #8 structure looks like this:

Figure 7-2: PKCS #8-encoded private key file

To decode this, then, you must first unwrap the top level structure and then decrypt it to reveal the second level structure, and finally unwrap that to reveal the key. Listing 7-17 illustrates this process for the case of an RSA private key encrypted using PBE with DES/MD5.

Listing 7-17: "privkey.c" parse_pkcs8_private_key

static unsigned char OID_pbeWithMD5andDES_CBC[] =

{ 0x2a, 0x86, 0x48, 0x86, 0xf7, 0x0d, 0x01, 0x05, 0x03 };

static unsigned char OID_RSAPrivateKey [] = { 0x2a, 0x86, 0x48, 0x86, 0xf7, 0x0d, 0x01, 0x01, 0x01 }; int parse_pkcs8_private_key( rsa_key *privkey, const unsigned char *buffer, const int buffer_length, const unsigned char *passphrase ) { struct asn1struct pkcs8_key; struct asn1struct private_key; struct asn1struct *encryptionId; struct asn1struct *salt; struct asn1struct *iteration_count; struct asn1struct *encrypted_key; struct asn1struct *key_type_oid; struct asn1struct *priv_key_data; digest_ctx initial_hash; int counter; unsigned char passphrase_hash_in[ MD5_RESULT_SIZE * sizeof( int ) ]; unsigned char passphrase_hash_out[ MD5_RESULT_SIZE * sizeof( int ) ]; unsigned char *decrypted_key; asn1parse( buffer, buffer_length, &pkcs8_key ); encryptionId = pkcs8_key.children->children; if ( memcmp( OID_pbeWithMD5andDES_CBC, encryptionId->data, encryptionId->length ) ) { fprintf( stderr, "Unsupported key encryption algorithm\n" ); asn1free( &pkcs8_key ); return 1; } // TODO support more algorithms salt = encryptionId->next->children; iteration_count = salt->next; encrypted_key = pkcs8_key.children->next; // ugly typecasting counter = ntohs( *iteration_count->data ); new_md5_digest( &initial_hash ); update_digest( &initial_hash, passphrase, strlen( passphrase ) ); update_digest( &initial_hash, salt->data, salt->length ); finalize_digest( &initial_hash ); memcpy( passphrase_hash_out, initial_hash.hash, initial_hash.hash_len * sizeof( int ) ); while ( --counter ) { memcpy( passphrase_hash_in, passphrase_hash_out, sizeof( int ) * MD5_RESULT_SIZE );

md5_hash( passphrase_hash_in, sizeof( int ) * MD5_RESULT_SIZE, ( unsigned int * ) passphrase_hash_out ); } decrypted_key = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( encrypted_key->length ); des_decrypt( encrypted_key->data, encrypted_key->length, decrypted_key, ( unsigned char * ) passphrase_hash_out + DES_KEY_SIZE, ( unsigned char * ) passphrase_hash_out ); // sanity check if ( decrypted_key[ encrypted_key->length - 1 ] > 8 ) { fprintf( stderr, "Decryption error, bad padding\n"); asn1free( &pkcs8_key ); free( decrypted_key ); return 1; } asn1parse( decrypted_key, encrypted_key->length - decrypted_key[ encrypted_key->length - 1 ], &private_key ); free( decrypted_key ); key_type_oid = private_key.children->next->children; if ( memcmp( OID_RSAPrivateKey, key_type_oid->data, key_type_oid->length ) ) { fprintf( stderr, "Unsupported private key type" ); asn1free( &pkcs8_key ); asn1free( &private_key ); } priv_key_data = private_key.children->next->next; parse_private_key( privkey, priv_key_data->data, priv_key_data->length ); asn1free( &pkcs8_key ); asn1free( &private_key ); return 0; }

The first part is pretty straightforward; at this point, you're dealing with an ASN.1 DER-encoded structure just like the ones you examined in Chapter 5. Parse it with asn1parse and extract the information, after making sure that the encryption algorithm is actually the one supported by this routine.

asn1parse( buffer, buffer_length, &pkcs8_key );

encryptionId = pkcs8_key.children->children;

if ( memcmp( OID_pbeWithMD5andDES_CBC, encryptionId->data,

encryptionId->length ) )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Unsupported key encryption algorithm\n" ); asn1free( &pkcs8_key ); return 1; } // TODO support more algorithms salt = encryptionId->next->children; iteration_count = salt->next; encrypted_key = pkcs8_key.children->next;

The same caveat about error checking from Chapter 5 applies here, although at the very least, you're not dealing with data transmitted by some random stranger over the Internet. A mistake here is likely to be user or programmer error rather than a malicious attack.

Next, decrypt the encrypted private key structure following the PKCS #5 structure.

// ugly typecasting

counter = ntohs( *iteration_count->data );

// Since the passphrase can be any length, not necessarily 8 bytes,

// must use a digest here.

new_md5_digest( &initial_hash );

update_digest( &initial_hash, passphrase, strlen( passphrase ) );

update_digest( &initial_hash, salt->data, salt->length );

finalize_digest( &initial_hash );

memcpy( passphrase_hash_out, initial_hash.hash,

initial_hash.hash_len * sizeof( int ) );

while ( --counter )

{

memcpy( passphrase_hash_in, passphrase_hash_out,

sizeof( int ) * MD5_RESULT_SIZE );

// Since MD5 always outputs 8 bytes, input size is known; can

// use md5_hash directly in this case; no need for a digest.

md5_hash( passphrase_hash_in,

sizeof( int ) * MD5_RESULT_SIZE,

( unsigned int * ) passphrase_hash_out );

}

decrypted_key = ( unsigned char * ) malloc( encrypted_key->length );

des_decrypt( encrypted_key->data, encrypted_key->length, decrypted_key,

( unsigned char * ) passphrase_hash_out + DES_KEY_SIZE,

( unsigned char * ) passphrase_hash_out );

If PBE was used elsewhere in this program, this section might be useful to extract as a separate function call; it's instead included inline here:

- The initial hash is built as the concatenation of the passphrase, which was passed as an argument to the function, and the salt, which was part of the key file itself.

- This hash is hashed over and over, counter times, to generate the keying material.

- This keying material, along with the encrypted structure, is passed into des_decrypt. This process is illustrated in Figure 7-3.

Figure 7-3: PKCS #5 password-based encryption

Checking That Decryption was Successful

If the passphrase was wrong, you still get back a data block here; it's probably a bad idea to blindly continue with the data without first checking that it decrypted correctly. Fortunately, there's a simple way to check for success with a reasonable degree of accuracy. Remember that DES data is always block-aligned. If the input is already eight-byte aligned, an extra eight bytes of padding is always added to the end. Therefore, if the last byte of the decrypted data is not between 1 and 8, then the decryption process failed. Of course, it could fail and still have a final byte in the range between 1 and 8. Technically speaking, you ought to go ahead and check the padding bytes themselves as well to minimize the chance of a false positive.

// sanity check

if ( decrypted_key[ encrypted_key->length - 1 ] > 8 )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Decryption error, bad padding\n");

asn1free( &pkcs8_key );

free( decrypted_key );

return 1;

}

Finally, the decrypted data must be ASN.1 parsed. After parsing, double-check that OID really declares it as an RSA private key before passing it on to the previously examined parse_private_key routine to extract the actual key value.

asn1parse( decrypted_key,

encrypted_key->length - decrypted_key[ encrypted_key->length - 1 ],

&private_key );

free( decrypted_key );

key_type_oid = private_key.children->next->children;

if ( memcmp( OID_RSAPrivateKey, key_type_oid->data, key_type_oid->length ) )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Unsupported private key type" );

asn1free( &pkcs8_key );

asn1free( &private_key );

}

priv_key_data = private_key.children->next->next;

parse_private_key( privkey, priv_key_data->data, priv_key_data->length );

Completing the Key Exchange

Now that you can read a stored private key from disk, whether it's stored unencrypted or in the standardized PKCS #8 format (they're also sometimes stored in PKCS #12 format, which isn't examined here), you can complete the key exchange, as shown in Listing 7-18.

Listing 7-18: "tls.c" parse_client_key_exchange

/**

* By the time this is called, "read_pos" points at an RSA encrypted (unless

* RSA isn't used for key exchange) premaster secret. All this routine has to

* do is decrypt it. See "privkey.c" for details.

* TODO expand this to support Diffie-Hellman key exchange

*/

static unsigned char *parse_client_key_exchange( unsigned char *read_pos,

int pdu_length,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

int premaster_secret_length;

unsigned char *buffer;

int buffer_length;

unsigned char *premaster_secret;

rsa_key private_key;

// TODO make this configurable

// XXX this really really should be buffered

if ( !( buffer = load_file_into_memory( "key.pkcs8", &buffer_length ) ) )

{

perror( "Unable to load file" );

return 0; } parse_pkcs8_private_key( &private_key, buffer, buffer_length, "password" ); free( buffer ); // Skip over the two length bytes, since length is already known anyway premaster_secret_length = rsa_decrypt( read_pos + 2, pdu_length - 2, &premaster_secret, &private_key ); if ( premaster_secret_length <= 0 ) { fprintf( stderr, "Unable to decrypt premaster secret.\n" ); return NULL; } free_huge( private_key.modulus ); free_huge( private_key.exponent ); free( private_key.modulus ); free( private_key.exponent ); // Now use the premaster secret to compute the master secret. Don't forget // that the first two bytes of the premaster secret are the version 0x03 0x01 // These are part of the premaster secret (8.1.1 states that the premaster // secret for RSA is exactly 48 bytes long). compute_master_secret( premaster_secret, MASTER_SECRET_LENGTH, parameters ); calculate_keys( parameters ); return read_pos + pdu_length; }

This should be easy to follow. The private key is loaded into memory and parsed; the private key is then used to decrypt the premaster secret. Of course, the same points about storing and buffering the private key apply here as they did to the certificate in the previous section.

The master secret computation and key calculation are almost identical on the server side as on the client side. The only difference is that, now, as the server, the read and write keys are reversed. Because you want to go ahead and use the exact same tls_send and tls_recv functions as before, remember that tls_send is looking for the write key, and tls_recv is looking for the read key. This means that you have to add a check in calculate_keys to determine if the current process is the client or the server and adjust accordingly in Listing 7-19.

Listing 7-19: "tls.c" calculate_keys with server support

static void calculate_keys( TLSParameters *parameters )

{

...

if ( parameters->connection_end == connection_end_client )

{ key_block_ptr = read_buffer( send_parameters->MAC_secret, key_block, suite->hash_size ); key_block_ptr = read_buffer( recv_parameters->MAC_secret, key_block_ptr, suite->hash_size ); key_block_ptr = read_buffer( send_parameters->key, key_block_ptr, suite->key_size ); key_block_ptr = read_buffer( recv_parameters->key, key_block_ptr, suite->key_size ); key_block_ptr = read_buffer( send_parameters->IV, key_block_ptr, suite->IV_size ); key_block_ptr = read_buffer( recv_parameters->IV, key_block_ptr, suite->IV_size ); } else // I'm the server { key_block_ptr = read_buffer( recv_parameters->MAC_secret, key_block, suite->hash_size ); key_block_ptr = read_buffer( send_parameters->MAC_secret, key_block_ptr, suite->hash_size ); key_block_ptr = read_buffer( recv_parameters->key, key_block_ptr, suite->key_size ); key_block_ptr = read_buffer( send_parameters->key, key_block_ptr, suite->key_size ); key_block_ptr = read_buffer( recv_parameters->IV, key_block_ptr, suite->IV_size ); key_block_ptr = read_buffer( send_parameters->IV, key_block_ptr, suite->IV_size ); }

The benefit of this approach is that tls_recv and tls_send work exactly as before. They don't care whether they're operating in the context of a client or a server.

TLS Change Cipher Spec

After receiving the key exchange and parsing it correctly, the server must send a change cipher spec message. It can't send one until the key exchange is complete because it doesn't know the keys. This message informs the client that it is starting to encrypt every following packet, and it expects the client to do the same.

The send_change_cipher_spec function is the same one shown in Listing 6-40; it looks exactly the same when the server sends it as it does when the client sends it.

TLS Finished

Finally, the server sends its finished message. Recall from Listing 7-4 that the client sends its finished message before the server does. Making sure to keep this ordering straight is important because one of the finished messages includes the other one in the handshake digest. The protocol would have worked just as well if the client waited for the server to send its finished message first, but it's critical that they both agree on the order for interoperability.

The send_finished code from Listing 6-48 can be used almost as is; the only difference between a client finished and a server finished is that the label input to the PRF by the server is the string "server finished", rather than the string "client finished". This necessitates one small change to the send_finished function shown in Listing 7-20.

Listing 7-20: "tls.c" send_finished with server support

static int send_finished( int connection,

TLSParameters *parameters )

{

unsigned char verify_data[ VERIFY_DATA_LEN ];

compute_verify_data(

parameters->connection_end == connection_end_client ?

"client finished" : "server finished",

parameters, verify_data );

And that's it. Everything else continues on just as it would have if this were a client connection; TLS doesn't care which endpoint you are after the handshake is complete.

You can run this ssl_webserver and connect to it from a standard browser; the response is the simple "Nothing here" message that was hardcoded into it. You'll have problems with Firefox and IE, unfortunately, because they (still!) try to negotiate an SSLv2 connection before "falling back" to TLS 1.0. Most TLS implementations are set up to recognize and reject SSLv2 connections; this one simply hangs if an SSLv2 connection request is submitted. Of course, the HTTPS client from Chapter 6 should connect with no problems.

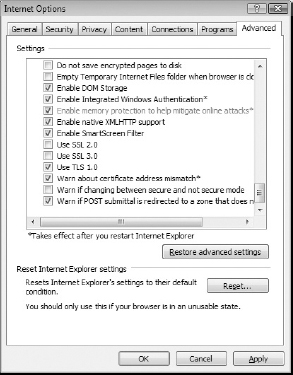

You can (and should!) disable SSLv2 support within IE8:

- Go to Tools

Internet Options

Internet Options  Advanced, and scroll down to the Security section.

Advanced, and scroll down to the Security section. - Uncheck the boxes Use SSL 2.0 and Use SSL 3.0

- Check the Use TLS 1.0 box, which is unchecked by default. Your Internet Options should look like Figure 7-4.

You should now be able to run the ssl_webserver example and connect to it from your browser. The page just states "Nothing here," but if you're feeling adventurous, you can easily change this to display anything you can think of.

If you run into otherwise inexplicable problems, ensure that the certificate file and the key file match. It's very easy to accidentally change a certificate file and forget to change the key file. One way to ensure that you've got the right key file for your certificate file is to compare the RSA moduli of each. If they're the same, the files are matches.

Figure 7-4: IE8 Internet Options

Also ensure that your client doesn't request one of the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocols; this server doesn't support those yet. This is addressed in Chapter 8.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls When Adding HTTPS Support to a Server

The server must pay closer attention to security than the client. If the client is compromised, one user's data is exposed; if the server is compromised, many users' data is at risk. The developer of the server code must be more careful to guard against security hazards such as data left over in shared cache lines. The topic of secure programming can, and does, span entire books. If you're developing code that will be deployed and used in a multi-user environment, you must be aware of these dangers.

When RSA is used for key exchange, the private key is especially vulnerable to attack. Ensuring that it's stored encrypted on disk using a solid, secure encryption method such as PKCS #5 is a good start. However, the private key itself must also necessarily be stored in memory, and you must take care to ensure that other users of the shared system that the server runs on can't, for example, force a core dump and then read the decrypted key at their leisure. Although a lazy system administrator can render all of your cautious coding moot, you must still ensure that a diligent system administrator's efforts don't go to waste.

Daniel Bleichenbacher discovered an interesting attack on the RSA private key. This attack wasn't on the server, but on most common implementations of TLS. His idea was to ignore the supplied public key and instead pass a specifically chosen bit string in the client key exchange message. At this point, the server has no choice but to attempt to decrypt it using its private key; it almost certainly retrieves gibberish. Because the server expects a PKCS 1.5-padded premaster secret, it first checks that the first byte is the expected padding byte 0x02; if it isn't, it issues an alert immediately.

Bleichenbacher took advantage of this alert — specifically that it was, at the time, always implemented as a different alert message than the alert that would occur later if a bad record MAC occurred. What would happen is that, most of the time, the server would immediately send an alert indicating that the RSA decryption failed. However, occasionally, the decrypted message would accidentally appear as a valid, padded message. The rest would decrypt in a garbled, unpredictable way, and the subsequent finished message would result in a bad record MAC, but the damage would have been done. The attacker knew that the chosen ciphertext did decrypt to a correctly padded message, even if he didn't know what that message was. In this way, TLS was leaking bits of information about the private key, which an attacker could exploit with about a million carefully chosen key exchanges.

The solution to this attack is simple: ignore padding errors and continue on with the key exchange, letting the final finished message failure abort the handshake. This way, the attacker doesn't know if the key exchange decrypted to a properly padded message or not. The implementation presented here doesn't address this, and is susceptible to the Bleichenbacher attack. If you want to tighten up the code to defend against the attack, you can either modify rsa_decrypt itself to go ahead and perform a decryption even if the padding type is unrecognized, but still return an error code, or modify parse_client_key_exchange to fill the premaster secret buffer with random values on a decryption failure and just continue on with the handshake, allowing the finished verification to cause the handshake to fail.

When a Browser Displays Errors: Browser Trust Issues

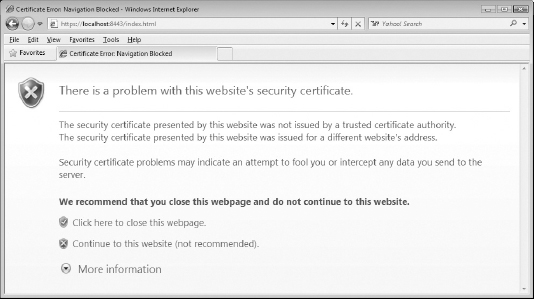

Of course, if you tried to connect to the SSL-secured web server described in this chapter, you almost definitely received some variant of the error message shown in Figure 7-5.

Figure 7-5: Certificate Error Message

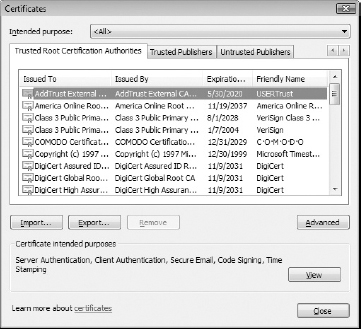

The error messages make sense. The server is using the self-signed certificate that you generated in Chapter 5, which is certainly not trusted. If you're so inclined, you can add it as a trusted certificate; go to Tools  Internet Options

Internet Options  Content

Content  Certificate

Certificate  Trusted Root Certification Authorities. (See Figure 7-6.)

Trusted Root Certification Authorities. (See Figure 7-6.)

Figure 7-6: Trusted root certification authorities

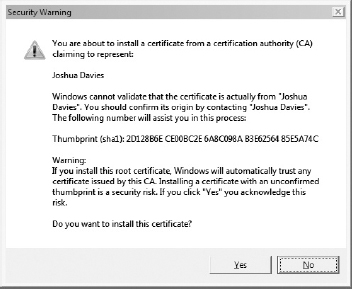

Click the Import button and follow the instructions in Figure 7-7 to import cert.der into your trusted certificates list.

Figure 7-7: New trusted certification authority

This clears up the first error that the certificate was issued by an untrusted certificate authority (it was issued by itself, actually). The browser still complains that the certificate was issued for a different website's address. You should understand by now that this means that the browser is connecting to localhost, but the certificate's subject has a CN of Joshua Davies. There's nothing stopping you, of course, from issuing a new certificate whose CN field is localhost, which makes this error disappear as well. As long as the certificate is signed by a trusted authority, the browser accepts anything that matches. If you click Continue to This Website, however, your browser remembers that you trust this certificate and automatically connects to it the next time you request it. IE 8 at least has the sense to display a red URL bar and provide a Certificate Error popup.

Watch the server and keep track of how an untrusted certificate error is handled. The client goes ahead and completes the handshake, but then immediately shuts down the connection. It then displays an error message to the user. If the user clicks through, it begins an entirely new SSL session, but this time with a security exception indicating that this site is to be trusted even if something looks wrong.

The only other common error message you might come across is "This site's certificate has expired." Of the error messages you might see, this one is probably the most benign, although it's certainly a headache for a server administrator because most TLS implementations give you no warning when a certificate is close to expiration. One day your site is working just fine; the next day the traffic has dropped to practically zero because your customers are being presented with a scary error message and bailing out. If you don't keep close track of logged error messages, you might have to spend some time investigating before you realize you've had yet another certificate expire.