CHAPTER 10

Other Applications of SSL

So far, this book has been almost myopically focused on the application of TLS to HTTP. Although HTTP was the primary motivation for the development of SSL in the first place, and continues to be the principal driver behind its evolution, HTTP is not the only protocol that relies on SSL/TLS to provide privacy and authentication extensions. This chapter examines a few of these other applications, and looks at some of the ways that the HTTP-focused design decisions in TLS complicate its adaptation to other protocols.

Adding the NTTPS Extension to the NTTP Algorithm

Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) is one of the oldest Internet protocols still in use. "In use" might be a charitable term — although the paramedics haven't pronounced NNTP dead, they've stopped resuscitating it and are just waiting for the heart monitor to stop beeping. I must admit I have a warm place in my heart for NNTP and the Usenet community that relied on it — before there was the National Center for Supercomputing Application's Mosaic or Mosaic's successor, Netscape Communicator, there was Usenet. I remember spending many hours in college, when I should have been working on programming assignments, in front of tin: the command-line, curses-based Unix Usenet reader. Although the newsgroups have since devolved into an unusable morass of spam, the early character-based Usenet is an example of what the Internet could be in its finest form. I blame high-speed connections and graphics-capable displays for the devolution of the once pure and beautiful Internet — now, you kids get off my lawn.

Although NNTP is an older protocol whose use is not nearly as widespread as it once was, it's useful as an example of an alternate means of initiating an SSL connection. HTTPS requires that you completely set up the SSL connection before a single byte of HTTP traffic can be sent. For this to be possible, the client must notify the server in some way of its intent to start with an SSL connection. HTTPS does this by assigning two separate ports to HTTP traffic. If the client wants a plaintext connection, it connects to port 80; if it wants SSL, it connects to port 443.

This is problematic in two ways:

- The use of multiple ports: If every protocol on the Internet needs two ports, the number of available ports is cut in half. TCP only allocates two bytes for the port number, which means that there are only 65,535 ports available to begin with.

- Switching from plaintext to encrypted communication requires a connection change: There's no provision in the TCP protocol for a connection to start using a new port. This isn't as bad with HTTP as with other protocols because HTTP is fundamentally stateless to begin with, but even HTTP has problems as a result. You've undoubtedly loaded a web page and have been presented with a security warning such as, "This page contains both secure and nonsecure items. Do you want to display the nonsecure items?" This happens when a web page is downloaded via HTTPS but some of the links within it are listed as using HTTP.

NNTP, defined in 1986 by RFC 977, was a stateful protocol. This was the only kind of protocol back in those days. The client software established a connection to the server on port 119 and sent text commands back and forth over this long-running socket connection. The socket itself would be held open until the session was complete. You could — and people did — interact with an NNTP server directly via telnet because the commands themselves were human-readable text.

At first, Usenet servers were provided by universities free of charge. Over time, though, Usenet traffic outgrew what could reasonably be provided for free, so commercial Usenet servers began to spring up, and they needed to support authentication to ensure that only paid-up users could send and receive. The original specification didn't provide for any means of client authentication, so RFC 2980 standardized an AUTHINFO extension to NNTP that allowed a user to provide a user name and password before issuing any commands.

Because you're reading a book about SSL/TLS, you can probably immediately spot the problem with this approach — NNTP is sent in the clear, with no provision for man-in-the-middle attacks or passive eavesdroppers. The simplest solution is to do what HTTP did and establish a new port for SSL-enabled connections. In fact, port 563 was assigned by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) for this purpose. A better approach, though, especially given that NNTP is a stateful protocol to begin with, is to establish a plaintext connection over port 119 and define a new command to switch to SSL. When the server receives this command, assuming the server recognizes, supports, and accepts it, the client should begin a TLS handshake as shown in Chapter 6.

NNTP uses the STARTTLS command for this purpose. When the client sends a STARTTLS command, the server must respond with response code 382 indicating that it supports TLS — if it doesn't, the client must either authenticate in the clear or terminate the connection. The server could even demand client-side authentication in this case, supplementing the password-based authentication described in RFC 2980. After the TLS handshake is complete, the NTTP session continues as it would have in the plaintext case, on the same socket that was originally established without TLS.

Although the same physical connection is used pre- and post-TLS negotiation, STARTTLS effectively resets all settings to what they were when the socket itself was first established. This is done because nothing that occurred prior to a successful TLS handshake can be trusted in a security-conscious setting; anything could have been modified by an active attacker, even if the client established the connection and immediately tried to submit a STARTTLS to secure it.

Implementing "Multi-hop" SMTP over TLS and Protecting Email Content with S/MIME

After the World Wide Web itself, email is about as fundamental and ubiquitous as Internet usage gets. Email has been around even longer than NNTP, and much longer than SSL or TLS, so it suffers from the same eavesdropping and man-in-the-middle vulnerabilities as NNTP, but the vulnerabilities are compounded by the complexity of email itself.

Understanding the Email Model

In the email model, individual users have mail boxes identified by email addresses such as joshua.davies@ImplementingSSL.com. These mail boxes are hosted by an email provider, typically at a different site than the actual user. A home email address, for example, is probably hosted by the user's Internet Service Provider. The email user connects periodically to check for new messages, but if a message is sent to a recognized email address, the hosting provider must store the message until the user connects to download it.

Additionally, the sender of the email doesn't generally establish a direct connection with the hosting provider of the recipient, but rather to his own hosting provider, who is responsible for correctly routing the email based on the email address domain. At a bare minimum, then, an email message probably passes through at least three distinct TCP connections, each unrelated to the other, and this can essentially occur at random times. The connection between the email's sender and his own hosting provider is governed by the SMTP protocol, and the connection between the receiver and his hosting provider is often governed by the POP protocol, although there are other protocols that can be used.

The SSL/TLS Design and Email

The whole point of the SSL/TLS design is to protect against the dangers of message exposure when messages are subjected to multiple hops. However, SSL can't do that unless it has end-to-end control over a socket that starts and ends the logical transaction. The sender must authenticate that the receiver is the actual receiver and not an impostor before transmitting any sensitive information. This is impossible in the context of email because the receiver — the holder of the email address — is probably not online when the email is sent and cannot provide credentials in the form of a certificate. This means that the client must implicitly trust the SMTP server not to expose any sensitive details about the email message in question, as well as negotiate a secure connection with the receiver's hosting provider.

Does this mean that TLS is useless in the context of email? Not exactly, but it doesn't provide the sort of end-to-end confidentiality and integrity that you probably want from a secure email relay service. However, TLS is very useful for an SMTP server because it strongly authenticates the sender and ensures that the sender is who it says it is, and it authorizes sending email through the SMTP service itself. Of course, it's also useful for the client to establish that the SMTP server is not an impostor either, and to guard against eavesdroppers on the local network.

To this end, RFC 3207 describes the STARTTLS extension for SMTP for senders of email and RFC 2595 describes the same extension for POP for the receiver of the email. Still, it would be nice to protect the message itself. This is less of a concern in the context of NNTP, where messages are always public, than in email, where messages are almost always private.

There have been a number of attempts to design email security systems that address end-to-end privacy; PEM and PGP both enjoyed some measure of success at various times as de facto standards. S/MIME, described by RFC 5751, however, is the official IETF email security mechanism. S/MIME is not actually an application of TLS because TLS was designed under the assumption that both parties are online and capable of responding to each other's messages synchronously throughout the whole exchange (such as is the case with HTTP). However, S/MIME is closely related and has all the same pieces.

An email message, at the protocol level, looks quite a bit like an HTTP message. It starts with a set of name-value pair headers, delimited by a single CRLF pair, after which the message itself starts. In fact, email and HTTP share a lot of the same name-value pair headers — email messages can have Content-Type, Content-Transfer-Encoding, and so on. A simple email message may look like this:

Received: from smtp.receiver.com ([192.168.1.1]) by smtp.sender.com with Microsoft SMTPSVC(6.0.3790.3959); Fri, 13 Aug 2010 04:58:25 −0500 Subject: I'm sending an email, do you like it? Date: Fri, 13 Aug 2010 04:58:31 −0500 Message-ID: <12345@smtp.receiver.com> From: "Davies, Joshua" <Joshua.Davies@ImplementingSSL.com> To: "Reader, Avid" <reader@HopefullyABeachInMaui.com> Hi there, I'm sending you an email. What do you think of it?

This is a pretty simple (not to mention mundane) plaintext email. The Received header indicates the path that the email took from sender to receiver; you can have several such Received lines if the email was transferred over multiple relays, as most are. The Subject is what appears in the summary area, and the remaining headers ought to be fairly self-explanatory. The actual body of the email in this example is the single line of text after the blank line.

Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME)

All modern email readers, for better or for worse, support the Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME) that allow the sender of the email to declare what are usually referred to by email reader software as attachments and which are offered as independent downloads to the message.

An email with attachments, at the wire-level, looks like this:

Received: from smtp.receiver.com ([192.168.1.1]) by smtp.sender.com

with Microsoft SMTPSVC(6.0.3790.3959); Fri, 2 Jul 2010 08:44:43 −0500

MIME-Version: 1.0

Content-Type: multipart/mixed;

boundary="----_=_NextPart_001_01CB19EC.B9C71780"

Subject: This email contains an attachment

Date: Fri, 2 Jul 2010 08:44:23 −0500

Message-ID: <12345@smtp.receiver.com>

From: "Davies, Joshua" <joshua.davies@ImplementingSSL.com>

To: "Reader, Avid" <reader@HopefullyABeachInMaui.com>

This is a multi-part message in MIME format.

------_=_NextPart_001_01CB19EC.B9C71780 Content-Type: text/plain; charset="iso-8859-1" Content-Transfer-Encoding: quoted-printable Hi there, this email has an attachment. I promise it's not a virus. ------_=_NextPart_001_01CB19EC.B9C71780 Content-Type: application/vnd.ms-excel; name="NotAVirus.xls" Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64 Content-Description: NotAVirus.xls Content-Disposition: attachment; filename="NotAVirus.xls" 0M8R4KGxGuEAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAPgADAP7/CQAGAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABAAAAKgAAAA EAAA/v///wAAAAD+////AAAAACkAAAD/////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ... ------_=_NextPart_001_01CB19EC.B9C71780--

This email contains a couple of new headers: MIME-Version and Content-Type. MIME-Version just indicates that the email reader must support MIME at a specific version; the second instructs the email reader how to parse the body of the email.

Content-Type should be followed by two strings that identify the type, separated by a forward-slash (/) delimiter, followed by a semicolon (;), followed by name-value parameters specific to the type itself. MIME content types are of the form text/html, text/xml, application/executable, image/jpeg. The first string identifies the broad classification of the type, and the second identifies a specialization of that class. In this case, the email's Content-Type is mulitpart/mixed, which indicates that the body itself consists of more than one mime type. The boundary="----_=_NextPart_001_01CB19EC.B9C71780" part indicates that the embedded MIME messages themselves are separated from each other by a long string that the email sender has verified doesn't occur within the message body itself.

There are two embedded MIME messages here:

- One of MIME type text/plain and a Content-Transfer-Encoding of quoted-printable

- Another of MIME type application/vnd.ms-excel and Content-Transfer-Encoding base64.

By convention, the email reader interprets the first message as text to display to the user in the body. The second, it makes available as a downloadable attachment. The attachment itself also declares a file name via the Content-Disposition header — this filename can be used, for example, to suggest a filename to save as if the user chooses to download the attachment.

Protecting Email from Eavesdroppers with S/MIME

There's no reason an email with an attachment must be a multi-part/mixed type. If there's just one attachment and nothing else, the Content-Type of the email header can perfectly and legitimately be the type of the attachment; the email reader just shows nothing except an attachment with no accompanying text. S/MIME takes advantage of this by creating an application/x-pkcs7-mime MIME type. As you can likely guess, this is another ASN.1 encoded structure.

An S/MIME encoded email message looks like this:

Received: from smtp.receiver.com ([192.168.1.1]) by smtp.sender.com

with Microsoft SMTPSVC(6.0.3790.3959); Wed, 21 Apr 2010 12:42:48 −0500

MIME-Version: 1.0

Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64

Content-Disposition: attachment;

filename="smime.p7m"

Content-class: urn:content-classes:message

Content-Type: application/x-pkcs7-mime;smime-type=enveloped-data;

name=smime.p7m;

smime-type=enveloped-data;

name="smime.p7m"

Subject: This message will self-destruct in 15 seconds

Date: Wed, 21 Apr 2010 12:42:47 −0500

Message-ID: <12345@smtp.receiver.com>

From: "Davies, Joshua" <joshua.davies@ImplementingSSL.com>

To: "Reader, Avid" <reader@HopefullyABeachInMaui.com>

MIAGCSqGSIb3DQEHA6CAMIACAQAxggNGMIIBnwIBADCBhjB4MRMwEQYKCZImiZPyLGQBGRY

MRUwEwYKCZImiZPyLGQBGRYFc2FicmUxEjAQBgoJkiaJk/IsZAEZFgJhZDEWMBQGCgmSJom

ARkWBkdsb2JhbDEeMBwGA1UEAxMVU2FicmUgSW5jLiBJc3N1aW5nIENBAgo84HbtAAEABSy

CsqGSIb3DQEBAQUABIIBAKHiUib4D3g8bA1AyInu2CkcB75mgMI/Sb5mQjmMNPo7Q0ypV1n

Regarding this email:

- Message body: This is a base64 encoded PKCS #7 envelope for which the email reader software must have a legitimate certificate in order to display. The body is simply an attachment.

- Headers: These describe the attachment in enough detail for the receiving email reader to interpret and decode it.

- Attachment: This is named via the Content-Disposition header element in the email message itself — in the case of S/MIME, the filename is important. S/MIME dictates old DOS-style three-character file extensions that indicate the type of the file. .p7m stands for "PKCS #7 Message." (.p7s, in contrast, is a PKCS #7 signature file.) The filename itself is usually smime.

PKCS #7 is slightly more complicated to parse than the X.509 certificates examined in Chapter 5 because PKCS #7 allows indefinite-length encodings. In other words, it follows the Canonical Encoding Rules (CER) rather than the DER (Distinguished Encoding Rules) that X.509 mandates. Indefinite-length encodings mean that the length is not explicitly output following that tag byte but instead, the application should read until it encounters two back-to-back 0 bytes. In other words, you process it just like a null-terminated C string, except that it has two null terminators instead of one. Parsing indefinitely encoded ASN.1 values can get somewhat complex because they can be nested inside one another.

The format of the message itself is currently described by RFC 5652, which refers to it as Cryptographic Message Syntax (CMS), a superset of PKCS #7.

PARSING PKCS #7

Parsing a PKCS #7-formatted S/MIME document is not for the faint of heart; I'll give an overview here, but if you're interested you should read the official specification document for complete details.

An S/MIME document body — such as the Base64-encoded .p7m part in the earlier example — is an ASN.1 sequence of what the specification refers to as content types. The most interesting case, and probably the most common, is when there is a single entry of content-type enveloped-data, which indicates that the content is encrypted. Of course, as you know, if anything is encrypted, a key is needed to decrypt it, so that key must be exchanged somehow. As you can probably guess, the key is exchanged using public-key techniques; if the sender has a certificate with the receiver's public RSA key, the content encryption key is encrypted using that key.

Securing Email When There Are Multiple Recipients

What about emails with multiple recipients? If you've ever sent an email, you know that there are often many recipients, some on the To: line and some on the CC: line. If this is the case, only one key is used to encrypt the message content, but that same key is public-key encrypted multiple times in the recipientInfo section of the .p7m attachment.

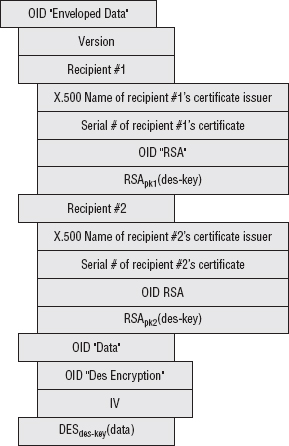

An encrypted S/MIME attachment with two recipients and a DES-encrypted attachment, then, takes the general form shown in Figure 10-1.

So, if you have the private-key corresponding to one of the public keys, you decrypt the symmetric key and use it to decrypt the message body. Notice that the certificate is identified by serial number, which is unique to an issuer; therefore the issuer must also be specified.

NOTE S/MIME also permits Key Agreement (for example, Diffie-Hellman) and pre-shared symmetric keys for encryption of the content encryption key.

Very often, when you finally decrypt the message body itself, you find that the contents are yet another S/MIME attachment! This is usually a plaintext email with a signature section, so that the recipient can authenticate the sender. S/MIME is a broad specification that permits messages to be signed but not encrypted and also covers certificate management.

Figure 10-1: S/MIME attachment format

Signing email messages can be a bit complex, though. Recall from Chapter 4 that computing a digital signature consists of securely hashing a set of data and then encrypting it using a public-key encryption algorithm with the private key. Verifying that same signature involves computing that same hash over the same data, decrypting the encrypted hash using the public key, and verifying that they match. It's important to the process that both sides agree on exactly what the data being hashed is; if even one bit of data changes between the generation of the signature and the subsequent verification, the signature is rejected. In the context of TLS, this is not an issue, because the message format is rigidly defined. The data that is signed is the data that is received; it's streamed over an open, established socket immediately after it's signed

However, email is a different story. The signature is generated sometimes days before it's verified, and traditionally, email relay systems have assumed impunity to modify the email message itself however they see fit in order to route the message from one place to another. If an email gateway feels the need to Base64-encode an email message, or convert from EBCDIC to ASCII, or change the charset from ISO-8859-12 to UTF-8, it does so and lets the receiver sort it all out later. This is a problem for email readers in general, and it's a showstopper for email signatures. As a result, both sides must agree rigidly on an email format and ensure that intervening gateways either don't modify the message content, or that the receiver can reliably undo whatever arbitrary transformations may have been applied en route. The easiest way to do this is to apply the most restrictive set of transformations to the message body, as detailed in RFC 5751.

S/MIME Certificate Management

One point that's been glossed over in the discussion so far is that of certificate management. TLS mandates a rigid means of certificate exchange; the client opens a connection and negotiates a key exchange, encryption, and MAC algorithm, and the server immediately responds with a certificate. The client uses that certificate to complete a key exchange. S/MIME is similar, but it's a delayed-reaction variant; the client in this scenario is the sender. In order for the sender to encrypt the content encryption key, this certificate must have been exchanged beforehand.

While TLS dictates specific rules on how this must happen and how this certificate must be validated and even what the certificate contains, S/MIME doesn't care at all; if you can uniquely identify a certificate, you can use its public key to encrypt. Whether you trust the validity of that certificate and whether you believe it belongs to the purported user is up to you. Of course, any email agent supporting S/MIME goes ahead and checks the trust-path of any certificate and warns you of any discrepancies in order to help you make a trust decision.

As you can see, neither TLS nor S/MIME is a complete solution to the email security problem — they're both required. TLS ensures that the SMTP server is really the SMTP server you think you're connecting to and that the SMTP headers themselves are private and not modified, and S/MIME (or some such equivalent) is required to ensure privacy of the email from the time it is written to the time it is received.

Securing Datagram Traffic

It's somewhat ironic that SSL, originally designed as an add-on to the stateless HTTP protocol, is itself so stateful. Everything about SSL/TLS requires that a context be established and maintained from the start of the handshake to the end of the tear-down; the sequence numbers must be maintained from one record to the next, the initialization vectors for CBC ciphers (prior to TLS 1.0) must be carried forward, and so on.

This is perfectly acceptable in the context of TCP, which keeps track of its own sequence numbers and internally handles reordering of out-of-sequence packets and retransmission of lost packets. However, TCP provides these services at a cost in terms of per-packet overhead and per-socket handshake time. Although on modern networks this overhead is practically negligible, a lighter-weight alternative, called User Datagram Protocol (UDP), has been part of TCP/IP almost from the beginning. With UDP, a packet is built and sent across the network with almost no header or routing information — just enough to identify a source and a target machine and a port.

This section examines the application of TLS concepts to datagram traffic.

Securing the Domain Name System

Chapter 1 presented, but didn't examine in-depth, the mapping between user-friendly hostnames and IP addresses. Ordinarily, a user doesn't connect to http://64.170.98.32/index.html but instead connects to http://www.ietf.org/index.html. This mapping of (arguably) human-readable domain names to machine-readable IP addresses is maintained by the Domain Name System (DNS). There's no automatic transformation that's applied here; the IP address isn't derived from the host name using some complex algorithm such as Base64; you can associate any host name with any IP address, as long as you can add an entry into the global DNS database.

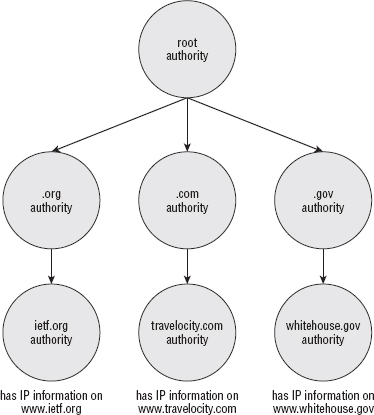

This database is huge and must be widely distributed. DNS describes a hierarchical management system where the top-level keeps track of the registrars for the ending parts of a DNS name such as .org, .com, .gov, and so on. These registrars, in turn, keep track of the registrars for the next-level — the part that comes before the .com. You can nest these names as deeply as you can imagine until an authoritative name server, which maps a completed domain name back to an actual IP address, is found. This hierarchy is illustrated in Figure 10-2.

There are thirteen master copies of the important top-level database, named A-M, distributed throughout the world and continuously synchronized. The website http://root-servers.org/ documents where these servers are physically located, what their IP addresses are, and who administers them. These copies are referred to as the Root DNS servers, and are considered authoritative. VeriSign, for example, operates the "J" root DNS servers, which have IP address 192.58.128.30. If VeriSign's root server states that .org is owned by a registrar at IP address XX.XX.XX.XX, then the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN)'s copy at 199.7.83.42 will say the same thing.

However, you probably don't (and probably shouldn't) request domain-name information from these root servers or the next-level registrars. Although each of these databases are replicated for load-balancing and redundancy purposes, there are many more slave copies of this same database distributed throughout the world. If you access the Internet through an ISP, for instance, your ISP almost certainly maintains a local cache of at least a subset of the master DNS data. You get the IP addresses of these local name servers when you get your own IP address at DHCP time. On a Linux system, you can see the IP addresses of the local copies under /etc/resolv.conf. On a Windows system, you can see them by going to Control Panel  Connection Status

Connection Status  Details and look under DNS Server. (Although I must warn you that this seems to change with every release of Windows, so you may have to hunt around a bit if you're on such a system.)

Details and look under DNS Server. (Although I must warn you that this seems to change with every release of Windows, so you may have to hunt around a bit if you're on such a system.)

So, when it comes time to resolve a human-readable, string host name to a machine-readable IP address, you typically call an operating system function, such as gethostbyname as illustrated in Listing 1-4. This function looks at /etc/resolv.conf (or wherever Windows hides it in its system registry), finds a name server, and asks it for the corresponding IP address. If the name server doesn't have the name/IP address pair cached already, it works backward through the domain name, first determining the authoritative name server for the top-level domain and then the authoritative name server for the next-level domain. When it finds an authoritative server for the actual requested host name, it issues a query to that server.

Using the DNS Protocol to Query the Database

You may be curious, though, about how gethostbyname actually queries the database. These days, if I say database, you may start thinking about SQL and SELECT statements, but the DNS naming system, thankfully, predates the relational database craze and instead defines its own Internet protocol. This protocol is named, unsurprisingly, DNS, and is an interesting protocol in the way it structures requests and responses.

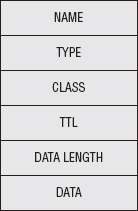

The DNS database is a collection of resource records (RR) as illustrated in Figure 10-3, each of which has a name, a type, a class, and a set of associated data that varies depending on the type. The most important type of resource record is type A, Host Address, which actually describes the mapping between a host name and an IP address. Type A, Host Address, RRs include an IP address in the associated data section. So, if a client has a host name for which it wants to query the corresponding IP address, it fills out as much information as it has on the RR, sends that to the server, and the server responds with as much information as it has — hopefully a completed record. The resource record itself is pretty open-ended — other available and common resource records include load-balancing information, redirect information, and mail server information.

Figure 10-3: Resource record format

Disadvantages of the DNS Query

Normally, this query is submitted not with a TCP socket, but with a UDP (datagram) socket, on port 53. UDP Requests and responses aren't rigidly matched like they are in TCP. After you send a UDP request, you just wait for data — any data at all — to be returned with the ports reversed. If a client has multiple outstanding DNS queries, it is responsible for correlating the responses correctly. DNS mandates that every request has a unique transaction ID for this purpose.

Herein lies the problem. Any malicious user on the network can easily spoof a DNS reply; all he needs to know is the source port (the destination port is always 53) and the transaction ID, both of which can be obtained with a packet sniffer. TCP is harder to spoof this way (but not impossible); UDP's stateless nature makes it simple. All the attacker has to do is to respond faster than the name server. The name server's response is received and ignored at a later time.

This gets even worse when you consider that if a name server doesn't have an IP address for a given domain name, it queries the next-higher name server, up to the root servers. An attacker can respond to the name server with his own bogus record. If he does so, then the name server dutifully caches the wrong information and then hands it out to all of the clients that it services. This is called DNS cache poisoning. In 2008, security researcher Dan Kaminsky showed how to subvert this process completely and poison the authority record, thereby taking over not just individual hosts, but entire domains.

Preventing DNS Cache Poisoning with DNSSEC

Although there are stopgaps to make DNS cache poisoning harder — better randomization of the transaction ID, wider variance of the request source port, and a check to see if multiple responses are received for the same query (a sure sign that something's amiss) — there have been efforts to roll out DNS Security (DNSSEC). This was specified back in 1999 by RFC 2535 and in spite of the flaws in the DNS system still has not been widely deployed. The idea behind DNSSEC is to deploy a public-key infrastructure around the domain-name system and sign each DNS record. If the receiver has a copy of a public key, the signature can be verified.

You can explore the DNS system using the dig tool that comes standard on all Unix systems. If you want to see the IP address for www.ietf.org, you can do this:

debian:ssl$ dig www.ieft.org ; <<>> DiG 9.3.4 <<>> www.ieft.org ;; global options: printcmd ;; Got answer: ;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 24804 ;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 0 ;; QUESTION SECTION: ;www.ietf.org. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION: www.ietf.org. 433 IN A 64.170.98.32 ;; Query time: 19 msec ;; SERVER: 209.18.47.61#53(209.18.47.61) ;; WHEN: Mon Sep 20 21:08:21 2010 ;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 46

This tells you that the IP address for www.ietf.org is 64.170.98.32. You can also view signature information for this domain name:

debian:ssl$ dig @209.18.47.61 www.ietf.org +dnssec ; <<>> DiG 9.3.4 <<>> @209.18.47.61 www.ietf.org +dnssec ; (1 server found) ;; global options: printcmd ;; Got answer: ;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 63769 ;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 2, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1 ;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION: ; EDNS: version: 0, flags: do; udp: 4096 ;; QUESTION SECTION: ;www.ietf.org. IN A ;; ANSWER SECTION: www.ietf.org. 1649 IN A 64.170.98.32 www.ietf.org. 1649 IN RRSIG A 5 3 1800 20110831142441 20100831132624 40452 ietf.org. mukwwlQll9RPzlKkWKgI2TnOka17jFrkgtavMEITvU5r4xTAhbZxXA3K mKAoK+d0OA0XiJC0u2GtsobAVtWVcrdqaeez1lw/TppW+otIj43ZzJ6e iKpytRJdFmJOS409mNLZaYjUgm6i154clMgmatOisLhX79snqQu18jG2 sRZE4faPmKw9kw9FNtOC8QuTCOGecTsmycuYpNbTxCSyD0Z4M1behKb9 rRzk1spXTBo6j2mn9vb8NYqY+Xa9JjLOe2Xw8bLGoQrdcB0+hBOBf4Od +bdgMKMIE1scO9QFqQvTD345v1u2FygXFe0UgE1l6KDz+ZA4prkvzbfo yPy53w== ;; Query time: 15 msec ;; SERVER: 209.18.47.61#53(209.18.47.61) ;; WHEN: Mon Sep 20 21:05:31 2010 ;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 353

RFC 4034 details the format of this signature record, the RRSIG record type. Of course, a signature is useless without a corresponding public key with which to validate it. The public key is held by the next higher level's authoritative name server:

debian:ssl$ dig ietf.org dnskey ;; Truncated, retrying in TCP mode. debian:ssl$ dig ietf.org dnskey +dnssec ; <<>> DiG 9.3.4 <<>> ietf.org dnskey +dnssec

;; global options: printcmd ;; Got answer: ;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 59127 ;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 4, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1 ;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION: ; EDNS: version: 0, flags: do; udp: 4096 ;; QUESTION SECTION: ;ietf.org. IN DNSKEY ;; ANSWER SECTION: ietf.org. 1800 IN DNSKEY 256 3 5 AwEAAdDECajHaTjfSoNTY58WcBah1BxPKVIHBz4IfLjfqMvium4lgKtK ZLe97DgJ5/NQrNEGGQmr6fKvUj67cfrZUojZ2cGRizVhgkOqZ9scaTVX NuXLM5Tw7VWOVIceeXAuuH2mPIiEV6MhJYUsW6dvmNsJ4XwCgNgroAmX hoMEiWEjBB+wjYZQ5GtZHBFKVXACSWTiCtddHcueOeSVPi5WH94Vlubh HfiytNPZLrObhUCHT6k0tNE6phLoHnXWU+6vpsYpz6GhMw/R9BFxW5Pd PFIWBgoWk2/XFVRSKG9Lr61b2z1R126xeUwvw46RVy3hanV3vNO7LM5H niqaYclBbhk= ietf.org. 1800 IN DNSKEY 257 3 5 AwEAAavjQ1H6pE8FV8LGP0wQBFVL0EM9BRfqxz9p/sZ+8AByqyFHLdZc HoOGF7CgB5OKYMvGOgysuYQloPlwbq7Ws5WywbutbXyG24lMWy4jijlJ UsaFrS5EvUu4ydmuRc/TGnEXnN1XQkO+waIT4cLtrmcWjoY8Oqud6lDa Jdj1cKr2nX1NrmMRowIu3DIVtGbQJmzpukpDVZaYMMAm8M5vz4U2vRCV ETLgDoQ7rhsiD127J8gVExjO8B0113jCajbFRcMtUtFTjH4z7jXP2ZzD cXsgpe4LYFuenFQAcRBRlE6oaykHR7rlPqqmw58nIELJUFoMcb/BdRLg byTeurFlnxs= ietf.org. 1800 IN RRSIG DNSKEY 5 2 1800 20110831142353 20100831132624 40452 ietf.org. hbpdgpVd3DHrRcO7S5Y8YfLgw+dj8YSLPU43wRzt7TLx+hdLXC3H7BGk 5UZvjTIlYiIw5fokRzu1zNgKQX+89yRASf8oHX8EFW/GqIZ03Hduvorr PbFyG3fw5Z5aMAeWTktwEQHc+OU0+m9srVT7fBndRXSWKNCg67NTbnKA kNKUajSohpQu3I9HiiBaFIHPm7sZYlnurxnFOQHUJiA6WvU6B332oAto AH9yBhV5ZK58GTg4t4KhAUD+w+oBdV4GXGVViGd0mCb2fN8OzJa9nb06 +A2DfAsW5zLBEBcP+yDO5ogKGNO0atwI232Wfi5h7HDncHRri7Shg63C e6xiFA== ietf.org. 1800 IN RRSIG DNSKEY 5 2 1800 20110831142553 20100831132624 45586 ietf.org. DhPTlnpVfvPUDUpz08zCXCDbNea8bu89Dok5mnyt1NXpP+OPZqZzXxDU A/blHG6Z6ZYAqGUHbYhgPEz9XQBj/fZy0Jn2F8QVHgxkpL8+MEsDvGCd t9o7kZoGd2eg3Hb0ImBMx59DLphHXwj3v0tOhEpZs25Pcul4QM5v7Pia fXk+R5XQ4YtBQnI6FZYlUP2EthSWSasKmvzK4Bmky7m9sFsZrzRWNKsF A+kvUPelbuz1m0WfsKBmh6klcok/BcVt4EluTeCoOloOra3t6JiPjrlv MKtn2nUYmGFM6JJGN/K8CA7wtr93BwwpAjVkWftfmIOgPCi7X8uFosAq 3T0+JA== ;; Query time: 76 msec ;; SERVER: 209.18.47.61#53(209.18.47.61) ;; WHEN: Mon Sep 20 21:09:46 2010 ;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 1181

This provides authentication and integrity, but it doesn't provide confidentiality — although it's questionable what value confidentiality would provide a DNS lookup because all of the data is public.

Still, it seems a shame that every datagram-based protocol must invent its own means of securing its traffic, doesn't it?

TLS Without TCP — Datagram TLS

In 2006, Nagendra Modadugu and Eric Rescorla drafted the Datagram TLS (DTLS) specification (http://crypto.stanford.edu/~nagendra/papers/dtls.pdf). Although you can't apply TLS directly to datagram traffic, the number of changes required to support it are surprisingly small. Whereas TLS's top-level encapsulating header includes just type, version and length, DTLS adds two fields:

- Epoch: This field increments whenever it receives a change cipher spec handshake message. This way, if the change cipher spec itself is lost, the server recognizes that the epoch has changed and knows something has gone wrong. Recognizing a dropped change cipher spec message is particularly important because that's the signal to start using encryption (or, in the case of a session renegotiation, to use new keying material).

- Sequence number: The purpose of this is obvious — to recognize dropped or out-of-order packets. TCP has one of these, too.

What about leftover cipher state? Prior to TLS 1.1, CBC-based ciphers used the last encrypted block as the IV for the next block — if one record is dropped, every subsequent record is undecryptable. TCP guards against this by providing automatic replay of dropped packets, but UDP has no such provision. Rather than require it, which would essentially force UDP to behave exactly like TCP in order to achieve any security, DTLS doesn't allow implicit IV's. They're a security hole anyway, so IV's are always output explicitly, TLS 1.1+ style. This also means that RC4, which carries state from one byte to the next, cannot be used with DTLS in any form; there's no safe way to explicitly output the current state of an RC4 cipher.

Interestingly, DTLS also requires that the client submit the ClientHello message twice. The first time, the server responds with a challenge "cookie" that the client must repeat in the second ClientHello. This proves that the client is actually receiving UDP packets at the given IP address and was designed to prevent denial of service (DOS) attacks.

From the implementer's perspective, the most difficult part of DTLS is the timeout and retransmit algorithm. Very similar to the one used by TCP, DTLS mandates a timeout and retransmit procedure with a sliding window. In fact, in a lot of ways, DTLS forces a UDP connection to behave like a TCP connection behaves. It hasn't yet been fully explored just how much overhead DTLS adds to a datagram connection and whether the extra overhead is worth DTLS or if the user might be better off just using TSL over TCP instead.

Supporting SSL When Proxies Are Involved

If you tried to use the HTTPS example client from Chapter 6 from behind a web proxy, you were probably disappointed in the results. The TLS model doesn't work at all with the proxy model. When proxies are involved, the client connects to the proxy, tells the proxy which document it would like to view, and the proxy retrieves that document and returns it on behalf of the client. This works fine in the HTTP model; the client barely even needs to modify its behavior based on the proxy. Rather than establishing a socket connection to the target site, the client just establishes a socket connection to the proxy, submits essentially the same request it would normally submit, and the proxy forwards that request on to the target.

This breaks down completely when you want to use HTTPS. Remember that when using HTTPS, before you transmit a byte of HTTP data, the first thing you must do is complete a TLS handshake. This is important because the TLS handshake establishes that you're talking to the server you think you're talking to (or, more pedantically, an entity that has convinced a certificate authority that it legitimately owns a specific domain name). This is necessary to guard against man-in-the-middle attacks. Unfortunately, a proxy is, by definition, a man-in-the-middle. You may be inclined to trust it — most likely you don't have a choice in the matter — but TLS doesn't.

Possible Solutions to the Proxy Problem

Other than just disallowing secure connections through proxies, the most obvious solution to this problem might be to establish an HTTPS connection to the proxy, forward the request, and allow it to establish an HTTPS connection to the target and continue as usual. This means that the proxy must be able to present a certificate signed by a certificate authority trusted by the browser, or the user needs to prepare to ignore untrusted certificate warnings. If the proxy presents a signed certificate, it needs to either purchase a top-level signed certificate, which is expensive, or it needs to distribute its own certificate authority to every browser that is configured to use it — which is administratively difficult.

Of course, you can always mandate that the browser never establish an HTTPS connection to the proxy; if it wants a secure document, it should establish a plain-old socket connection to the proxy and let the proxy deal with the secure negotiation. This presupposes, of course, that every node between the browser and the proxy is trusted because everything that passes to the proxy is passed in plaintext. This may or may not actually be the case.

A more serious problem with both of these approaches, however, is that the client itself can't see any certificate warnings. If the certificate is out of date, untrusted, or for a different domain than the one requested, only the proxy is aware of this. In addition, the proxy needs to know which CAs the client trusts, otherwise the client can't update its trust list. HTTP proxies are supposed to be pretty simple; — they have to handle huge volumes of requests, so you want to avoid adding any more complexity than necessary. Building the protocol extensions to enable the proxy to channel certificate warnings back to the client and respond to them is fairly complex.

Instead, the standard solution suggested by RFC 2817 is that HTTP proxies don't proxy secure documents at all — they proxy connections, instead. The proxy must accept the HTTP CONNECT command, which tells it not to establish an HTTP socket with a target host, but instead to establish an arbitrary socket connection. In effect, when the proxy receives a CONNECT command, rather than, for instance, a GET or a POST, it should complete the TCP three-way handshake with the target host on the target port, but from that point on it should tunnel all subsequent data unchanged.

This enables the client to complete the TLS handshake and respond appropriately to any certificate warnings, and so on, that may occur — the code itself doesn't change at all. The only trick is making sure to establish the tunneled connection before beginning the TLS handshake.

Adding Proxy Support Using Tunneling

You can add proxy support to the HTTPS client from Chapter 6; After you understand how tunneling works, it's not terribly complicated. Instead of affixing a proxy authorization to each HTTP command, you instead issue a single HTTP CONNECT command before doing anything TLS-specific; the authorization string is attached to that command and forgotten afterward. If the CONNECT command succeeds, you just use the socket as if it was a direct connection to the target host, which, at this point, it is.

Recognizing the proxy parameters and parsing them doesn't change from HTTP to HTTPS. The only difference in the main routine is that you issue an HTTP CONNECT command after establishing the HTTP connection to the proxy and before sending a TLS handshake as shown in Listing 10-1.

Listing 10-1: "https.c" main routine with proxy support

if ( proxy_host )

{

if ( !http_connect( client_connection, host, port, proxy_user,

proxy_password ) )

{

perror( "Unable to establish proxy tunnel" );

if ( close( client_connection ) == −1 )

{

perror( "Error closing client connection" );

return 2;

This makes use of the http_connect function shown in Listing 10-2.

Listing 10-2: "https.c" http_connect

int http_connect( int connection,

const char *host,

int port,

const char *proxy_user,

const char *proxy_password )

{

static char connect_command[ MAX_GET_COMMAND ];

int received = 0;

static char recv_buf[ BUFFER_SIZE + 1 ];

int http_status = 0;

sprintf( connect_command, "CONNECT %s:%d HTTP/1.1\r\n", host, port );

if ( send( connection, connect_command,

strlen( connect_command ), 0 ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

sprintf( connect_command, "Host: %s:%d\r\n", host, port );

if ( send( connection, connect_command,

strlen( connect_command ), 0 ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

if ( proxy_user )

{

int credentials_len = strlen( proxy_user ) +

strlen( proxy_password ) + 1;

char *proxy_credentials = malloc( credentials_len );

char *auth_string = malloc( ( ( credentials_len * 4 ) / 3 ) + 1 );

sprintf( proxy_credentials, "%s:%s", proxy_user, proxy_password );

base64_encode( proxy_credentials, credentials_len, auth_string );

sprintf( connect_command, "Proxy-Authorization: BASIC %s\r\n",

auth_string );

if ( send( connection, connect_command,

strlen( connect_command ), 0 ) == −1 )

{

free( proxy_credentials );

free( auth_string ); return −1; } free( proxy_credentials ); free( auth_string ); } sprintf( connect_command, "\r\n" ); if ( send( connection, connect_command, strlen( connect_command ), 0 ) == −1 ) { return −1; } // Have to read the response! while ( ( received = recv( connection, recv_buf, BUFFER_SIZE, 0 ) ) > 0 ) { if ( http_status == 0 ) { if ( !strncmp( recv_buf, "HTTP", 4 ) ) { http_status = atoi( recv_buf + 9 ); printf( "interpreted http status code %d\n", http_status ); } } if ( !strcmp( recv_buf + ( received - 4 ), "\r\n\r\n" ) ) { break; } } return ( http_status == 200 ); }

This ought to look pretty familiar; the first half is the http_get function from Chapter 1 with a few details changed. If you're so inclined, you can probably see a way to consolidate these both into a single function. Notice that you still connect on port 80 to the proxy; the CONNECT command sent includes the desired port of 443.

Because CONNECT is an HTTP command, the proxy starts by returning an HTTP response. At the very least, you have to read it in its entirety so that the first recv command you invoke inside tls_connect doesn't start reading an HTTP response when it's expecting a ServerHello message. Of course, it's probably worthwhile to have a look at the response code as well, as in Listing 10-2. If you mistyped the password, or failed to provide a password to an authenticating proxy, you get a 407 error code. If this is the case, you should abort the connection attempt and report an error to the user.

One thing that's particularly interesting about this approach to supporting HTTPS through proxies is that it means that, in order to properly support HTTPS, the proxy must be capable of establishing arbitrary connections with arbitrary hosts as long as the authentication is completed properly. This capability can be used to tunnel any protocol through an HTTP proxy, although the client software has to be modified to support it.

SSL with OpenSSL

It would be irresponsible of me to recommend using a tried-and-true SSL library, such as OpenSSL, but then not show you how to do so, especially if your desire is to do production-grade security work. Listing 10-3 reworks the HTTPS example from Chapter 6 using the OpenSSL library.

Listing 10-3: "https.c" with OpenSSL

#include <openssl/ssl.h>

...

int http_get( int connection,

const char *path,

const char *host,

SSL *ssl )

{

static char get_command[ MAX_GET_COMMAND ];

sprintf( get_command, "GET /%s HTTP/1.1\r\n", path );

if ( SSL_write( ssl, get_command, strlen( get_command ) ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

sprintf( get_command, "Host: %s\r\n", host );

if ( SSL_write( ssl, get_command, strlen( get_command ) ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

strcpy( get_command, "Connection: Close\r\n\r\n" );

if ( SSL_write( ssl, get_command, strlen( get_command ) ) == −1 )

{

return −1;

}

return 0;

}

void display_result( int connection, SSL *ssl )

{ int received = 0; static char recv_buf[ BUFFER_SIZE + 1 ]; while ( SSL_get_error( ssl, ( received = SSL_read( ssl, recv_buf, BUFFER_SIZE ) ) ) == SSL_ERROR_NONE ) { recv_buf[ received ] = '\0'; printf( "data: %s", recv_buf ); } printf( "\n" ); } int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] ) { ... int ind; SSL_CTX *ctx; SSL *ssl; BIO *sbio; BIO *bio_err=0; SSL_METHOD *meth; if ( argc < 2 ) { fprintf( stderr, "Usage: %s: [-p http://[username:password@]proxy-host:proxy-port]\ <URL>\n", argv[ 0 ] ); return 1; } // OpenSSL-specific setup stuff SSL_library_init(); SSL_load_error_strings(); bio_err=BIO_new_fp(stderr,BIO_NOCLOSE); meth=SSLv23_method(); ctx=SSL_CTX_new(meth); proxy_host = proxy_user = proxy_password = host = path = NULL; ... // set up the connection itself ssl=SSL_new(ctx); sbio=BIO_new_socket(client_connection,BIO_NOCLOSE); SSL_set_bio(ssl,sbio,sbio); if(SSL_connect(ssl)<=0) { fprintf( stderr, "Error: unable to negotiate SSL connection.\n" ); if ( close( client_connection ) == −1 ) {

perror( "Error closing client connection" ); return 2; } return 3; } http_get( client_connection, path, host, ssl ); display_result( client_connection, ssl ); SSL_CTX_free(ctx); if ( close( client_connection ) == −1 )

You should have no trouble understanding the OpenSSL library after reading through the rest of this book; in fact, the source code itself should begin to make a lot of sense to you as well.

Final Thoughts

Of course, the challenge is to ensure that TLS is implemented in a secure way — it's not enough to just use TLS. You must ensure that no sensitive information is leaked, that random numbers are properly seeded, and that private keys remain private, hidden behind secure passphrases. I can't count how many times I've seen a perfectly secure implementation rendered useless by a plaintext configuration file, containing the private key passphrase, checked into the source code control system.

The only advice I can offer here is to look at your application as an attacker might. An attacker always goes for the weakest part of your defense; so most likely the part that you've focused the most effort on securing is of the least interest to a smart attacker.

Finally, though, accept that security is ultimately a trade-off. They say that no home security system can keep out a determined intruder. The same is true of software security. You must balance security with usability. As long as that tradeoff is made deliberately, conscientiously, and collaboratively, with proper documentation, you've struck a decent balance; with any luck, malicious intruders will move past your system for lower-hanging fruit.