CHAPTER 5

Creating a Network of Trust Using X.509 Certificates

Chapters 3 and 4 discussed public and private keypairs and reviewed their importance to secure communications over insecure channels. Until now, where these keys come from and how they're exchanged has been mostly glossed over. Where the keys come from is the topic of this chapter. This chapter also includes some further discussion on authentication.

You're probably familiar with the term certificate, even if you're fuzzy on the details. You've undoubtedly visited web sites that have reported errors such as "this website's certificate is no longer valid" or "this website's host name does not match its certificate's host name" or "this certificate was not signed by a trusted CA." If you're like most Internet users, you generally ignore these warnings, although in some cases they can indicate something important.

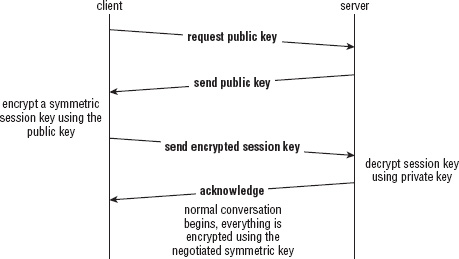

Fundamentally, the certificate is a holder for a public key. Although it contains a lot more information about the subject of the public key — in the case of web sites, that would be the DNS name of the site which has the corresponding private key—the primary purpose of the certificate is to present the user agent with a public key that should then be used to encrypt a symmetric key that is subsequently used to protect the remainder of the connection's traffic.

At this point, you may have at least a hazy idea of how most of the concepts of the past three chapters can be put together to establish a secure communications link: First, a symmetric algorithm and key is chosen, and then the key is exchanged using public-key techniques. Finally, everything is encrypted using the secret symmetric key and authenticated using an HMAC with another secret key. However, the digital signatures examined in Chapter 4 haven't come into play yet. How are these used and why are they important? Digital signatures are how certificates are authenticated and how you can determine whether or not to trust a certificate. This is examined in much greater detail later in this chapter.

Putting It Together: The Secure Channel Protocol

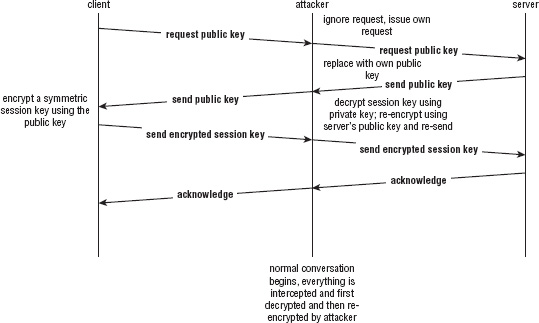

Armed with symmetric encryption and some method of secure key exchange, such as public key encryption of the symmetric encryption key, you have enough to implement a secure channel against passive eavesdroppers. Assuming that an attacker can see, but not modify, your data, you could adopt the simple secure channel protocol shown in Figure 5-1.

Figure 5-1: Naïve secure channel protocol

Even if an attacker can view all packets exchanged, all he sees is that the public key was requested and what the public key was — which, by definition, is not a secret. From that point forward, everything is encrypted and, assuming the encryption method is unbreakable, the remainder of the session is secure.

However, a more dangerous form of attack is called a man-in-the middle attack and is carried out by an adversary who can not only view traffic, but also can intercept and modify it. Consider the scenario shown in Figure 5-2.

The problem here is that the client implicitly trusts that the public key belongs to the server. Solving this trust issue surrounds most of the complexity associated with SSL/TLS. The remainder of this book is spent looking at how to get around this problem.

The solution adopted by SSL requires the use of a trusted intermediary. This trusted intermediary digitally signs the public key of the server—using the algorithms discussed in Chapter 4—and the client must verify this signature. Such a signed public key is called a certificate, and a trusted intermediary responsible for signing certificates is called a certificate authority (CA). The client must have access to the public key of the CA so that it can authenticate the signature before accepting the key as genuine. Web browsers have a list of trusted CAs with their public keys built in for just this purpose.

Figure 5-2: Man-in-the-middle attack

This buys a bit of security against a man-in-the-middle attack, but not much. After all, if the server can get a certificate signed by the trusted CA, you must assume that the attacker, if sufficiently motivated, could do so too. He could present himself to the CA as a legitimate business, for example. This makes his job a bit more difficult, but hardly insurmountable.

What you really need is some way to associate the public key with the server you're connecting to. Thus, a properly formatted certificate needs to have not only the public key of the server included, but also the domain name of the server that the public key belongs to, all signed by the trusted intermediary.

This foils the man-in-the-middle attack. The client requests a certificate from the server, and the man in the middle replaces it with his own. The client then validates the attacker's certificate as legitimate—it's signed by a trusted CA—but observes that the domain doesn't match that of www.server.com, as expected. Nor can the attacker forge a certificate with the domain name www.server.com—this is protected by the digital signature. If he obtains a digitally signed certificate from the CA, with the domain name www.attacker.com, and then changes his own domain in the certificate to www.server.com, the hash code in the signature won't match the hash code of the contents of the certificate, and the client rejects it on this basis.

So, at a bare minimum, in order to protect yourself against man-in-the-middle attacks, you need a trusted CA and a certificate format that includes the domain name, the public key and a digital signature issued by the CA. Now, imagine that a few years go by, and the administrator of the server figures that it's time to reissue the certificate. After all, technology changes, and certificate security holes are found from time to time. And who knows? Some hacker could have broken into the system and stolen the private key without the administrator's knowledge.

Unfortunately, the administrator can't reissue the certificate. Assuming that there's a problem with the certificate—the private key has been compromised or the certificate technology is outdated and includes a security flaw—and the server installs a new certificate, the man in the middle strikes again. When the client tries to connect, the attacker substitutes the old, and presumably weaker, certificate for the new one. The client has no way to authenticate this certificate; the domain is correct, and so is the issuer's digital signature.

To partially guard against this, certificates also include a validity period: a not before date and a not after date. It's the responsibility of the client to check that the certificate's not after date does not fall in the past. If the date is in the past, the client should not connect to the server.

As you can imagine, this is really only half a solution. Imagine that the private key has been compromised and the server administrator knows that the private key been compromised. He should immediately stop allowing use of the compromised certificate. The validity period guarantees that clients stop using the certificate at some point in the future, but you really want a way to accelerate that date. Again, that can't be forced, because a man in the middle can just replace any new certificate with an old one, right up until the end of the validity period.

To fight against this, CAs are responsible for keeping a list of revoked certificates that is called a certificate revocation list (CRL). The client periodically checks this list. But wait—checks it for what? How can you uniquely identify a certificate? As they've been specified so far, you can't; you need one more field in the certificate format, the serial ID. This is a number, unique within a CA, assigned to each certificate. When a certificate is known or believed to be compromised, its serial number is added to the CRL. If the man in the middle tries to replace a new certificate with an old one, the client recognizes that the serial number has been revoked and rejects the connection.

Finally, it's unlikely that everybody on the Internet will use a single CA. That means that the client, when presented with a certificate, needs some way to know whose public key to use to verify the signature. As such, each certificate also includes an issuer that uniquely identifies the CA. The client decides whether or not to trust the issuer dynamically.

Encoding with ASN.1

Certificates need to be precisely defined. Although this sort of structured data is now usually represented and defined in XML, certificates have been around for quite a while, longer than XML. They're specified instead using a syntax referred to as Abstract Syntax Notation (ASN), or ASN.1 (the .1 being the version of Abstract Syntax Notation). ASN serves the same purpose as a DTD or an XSD might serve in an XML context; it describes how elements are nested within one another, what order they must occur in, and what type each is. Official ASN.1 looks quite a bit like a C struct definition, although the differences are significant enough that you can't map directly from one to another.

The certificate format that SSL/TLS uses is defined and maintained by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in a series of documents they just refer to as the X series. The documents themselves can be found at http://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-X/en. Each one has a number, and the corresponding document/standard is referred to as X.nnn where nnn is a number. So, for instance, if you want to see the official standard for X.509, you look under http://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-X.509/en. I'll refer to several of these specifications by number throughout this chapter.

You may notice that the specifications presented here aren't always specific to SSL/TLS. They were developed independently and adopted later by the Internet consortium. As such, the specifications contain quite a few elements that aren't necessarily relevant to the subject matter of this book itself; I'll mention some of these elements here but refer the interested reader to other sources for details.

Understanding Signed Certificate Structure

ASN.1 is used to describe the structure of an X.509 certificate, which is the official standard for public-key certificates and the format on which TLS 1.0 relies. X.509 has been through three revisions; the current, at the time of this writing, revision of X.509 is 3. The top-level structure of an X.509v3 certificate is shown in Listing 5-1.

Listing 5-1: X.509 Certificate structure declaration

SEQUENCE {

version [0] EXPLICIT Version DEFAULT v1,

serialNumber CertificateSerialNumber,

signature AlgorithmIdentifier,

issuer Name,

validity Validity,

subject Name,

subjectPublicKeyInfo SubjectPublicKeyInfo,

issuerUniqueID [1] IMPLICIT UniqueIdentifier OPTIONAL,

-- If present, version shall be v2 or v3

subjectUniqueID [2] IMPLICIT UniqueIdentifier OPTIONAL, -- If present, version shall be v2 or v3 extensions [3] EXPLICIT Extensions OPTIONAL -- If present, version shall be v3 }

Excerpted fromhttp://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2459.txt

The syntax is given in ASN.1. ASN.1 syntax isn't covered completely here; however, you have to understand a fair bit of it to analyze X.509 because X.509 makes use of most of ASN.1. See http://luca.ntop.org/Teaching/Appunti/asn1.html for a complete overview of ASN.1 syntax.

The first line here in the top-level structure of the X.509v3 certificate is SEQUENCE. An ASN.1 SEQUENCE is analogous to a C struct, which may be confusing to a C programmer because sequence sounds more like an array. An ASN.1 sequence groups other elements. As you can see, this sequence contains 10 subelements. The most important of these, of course, is the seventh, subjectPublicKeyInfo, because the primary purpose of a certificate is to transmit a public key.

Each subelement is presented with a name followed by a type—just like a C struct, but inverted. Each of these is examined in detail in the following sections. I'll go over the meaning of each at a high-level, and then come back and show you how to parse a real certificate; if some of this seems a bit abstract, the code samples at the end of this chapter should clear up the intent behind all of these elements.

Version

version [0] EXPLICIT Version DEFAULT v1

The version is an integer between 0 and 2, with 0 representing version 1, 1 representing version 2, 2 representing version 3, and so on. The version number indicates how to parse the remaining structures. For example, the comments at the bottom that indicate issuerUniqueId, subjectUniqueId, and extensions cannot be present if the version is less than 2. However, the original X.509 specification didn't include a version number, so it's necessary for the parser to first check to see if a version number is present. If no version number is present, the parser should assume that the version number is 0 (that is, v1). That's the meaning of the EXPLICIT DEFAULT v1 in the declaration.

The type Version itself is defined in the specification as

Version ::= INTEGER { v1(0), v2(1), v3(2) }

This tells you that the version field is an integer and that it can take on three discrete values.

serialNumber

As discussed in the section "Putting It Together: The Secure Channel Protocol" earlier in this chapter, certificates are signed by CAs. The process of signing a certificate is often referred to as issuing a certificate, and the signer is referred to as the issuer, although this terminology is a bit misleading. Each signer is required to assign a unique serial number to each certificate issued. The serial number is not necessarily globally unique, but it can safely be assumed that VeriSign (a popular CA), for example, never reuses a serial number. Two different CAs may issue two certificates with identical serial numbers, but the same CA never will. The CertificateSerialNumber is defined as an INTEGER.

signature

signature AlgorithmIdentifier,

An X.509 certificate must have been signed by a CA. Whether that CA is trusted or not is a matter for the client to decide. In fact, for testing purposes, it's often useful to create self-signed certificates, in which case the certificate is digitally signed by the private key corresponding to the public key that it contains.

Whoever signed the certificate, the signature algorithm used must be identified by this field. The declaration for an algorithm identifier is

AlgorithmIdentifier ::= SEQUENCE {

algorithm OBJECT IDENTIFIER,

parameters ANY DEFINED BY algorithm OPTIONAL }

Here you see a new type you haven't come across before: the object identifier (OID). OIDs are used quite a bit in the X.509 standard and anything else that's based on ASN.1. OIDs are actually murderously complex and describe a hierarchy of just about anything you can think of. Fortunately, you don't really need to fully understand OIDs. You can treat them simply as byte arrays and keep track of the mappings of these byte arrays and their meanings.

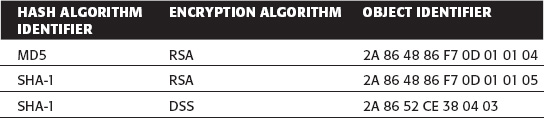

Recall from the Chapter 4 that digitally signing a sequence of bytes involves first securely hashing those bytes using a secure hash algorithm such as MD5 or SHA and then encrypting the bytes using a private key. Thus, a digital signature algorithm identifier must identify both the secure hashing algorithm applied as well as the encrypting algorithm. Given MD5 and SHA for secure hashing algorithms and RSA and DSS for private-key encryption algorithms, you end up with four separate algorithm identifiers. However, because MD5 is not specified for use with DSS, there are only three algorithm identifiers, which are shown in Table 5-1.

Table 5-1: Signing Algorithm OIDs

See X.690 and RFC 2313 for more details on how these values are determined. All you particularly care about is that the third field of the certificate (or the second, if the version number was not supplied) is equal to one of these three-byte sequences. You use this value as a switch to validate the signature of the certificate.

NOTE You may be wondering: "What about ECDSA?" Well, that's sort of complicated. The topic of elliptic-curve cryptography (ECC) in X.509 is revisited in Chapter 9. In general, ECC is not explicitly supported by any version of TLS < 1.2, and supporting it in any version can get a bit hairy.

If you read any of the ITU X series specification documents, you'll notice that the OIDs are not given in hexadecimal form as they are in Table 5-1. Instead, they're given in a dotted-decimal form such as 1.2.840.113549.1.1.4. However, in order to be used, they must be converted to the hexadecimal forms shown in this book. The X.690 specification details this conversion authoritatively. You don't actually need to know how to convert from these dotted-decimal numbers to the normalized hexadecimal forms in order to use them. I've converted all of the ones you need to know but if you're curious, read on.

An OID in X.509 is a leaf in a very, very large tree structure. For example, the OID for the MD5withRSA signature algorithm is 1.2.840.113549.1.1.4. Each number in this very long digit string identifies an element in a large hierarchy. 1 represents iso; 1.2 represents iso/memberBody; 1.2.840 represents iso/member-body/usa and so on. All in all, the OID in this example represents iso/memberBody/usa/rsadsi/pkcs/pkcs1/MD5. Each number only has meaning relative to what came before it. The RSA corporation controls the 1.2.840.113549 namespace and they use 1.1.4 to identify rsa with pkcs #1 padding md5.

So how do you get from 1.2.840.113549.1.1.4 to 2A 86 48 86 F7 0D 01 01 04? Well, the 01 01 04 part is pretty obvious: This is the byte representation of the digits 1.1.4. But as you can see, even the third numeral, 840, is too large to fit into a single byte. Rather than include separators, they adopted a variable-length encoding scheme (The X.500 family of specifications, which includes X.509, is big on variable-length encoding schemes). The 86 48 represents 840, and the 86 F7 0D represents 113549. The encoding scheme used here is this: If the high-order bit is 1 then the other seven bits in this byte should be concatenated with the next byte. If the high-order bit is 0 then this is the last byte in the identifier. So 840, in binary, is 1101001000. This is longer than seven bits, so break it up into chunks of seven or less:

110 1001000

Now, add the high-order bits (and pad the first one):

10000110 01001000

Or hexadecimal 86 48.

The decoder then sees the first byte, recognizes that the high-order bit is 1, continues on to the next byte, sees that the high-order bit is zero, and concatenates the seven lower-order bits of the two constituent bytes back into the value 1101001000, or decimal 840. Likewise, 113549 encodes to 11011101110001101 in binary. This requires 20 bits to encode, so you use three bytes ( ), with the high-order bits of the first two being set to 1, which tells the decoder that this should be concatenated with the next byte:

), with the high-order bits of the first two being set to 1, which tells the decoder that this should be concatenated with the next byte:

10000110 11110111 00001101

Or 86 F7 0D in hexadecimal.

Is your head spinning yet? Actually, it gets worse. Notice that the hex encoding of the "1.2" on the very beginning of the OID is a single byte: 2A. To save space, X.690 dictates that the first byte encodes two numeric elements according to the algebraic equation Z = 40X + Y. So, 1.2 is 40 * 1 + 2 = 42 (0x2A). On the unpacking side, it's safe to assume that if the byte is in the range 0–40, the decoded value should be 0.(byte); if it's in the range of 41–80, it should be 1.(byte – 40); if it is in the range of 81–120, it should be 2.(byte – 80); and so on. Obviously, this limits the range of values that can be encoded by the first byte.

Fortunately, I've done all of the conversion for you, so you don't have to understand any of this to code around it. All you need to know is that the unique byte sequence 2A 86 48 86 F7 0D 01 01 04 represents the MD5withRSA signature algorithm.

There is also an optional section for parameters. DSS includes a few parameters, so you re-examine this when DSA is covered. Notice that the ANY DEFINED BY algorithm indicates that if the object identifier is one of the two RSA algorithms, the parameters field is not present.

issuer

issuer Name

If you found the subject of OIDs slightly complicated, hold on to your hat as you examine X.509 distinguished names. You've likely seen a distinguished name written out at some point in long form, such as

CN=Joshua Davies,OU=Architecture,O=Travelocity,L=Southlake,ST=Texas,C=USA

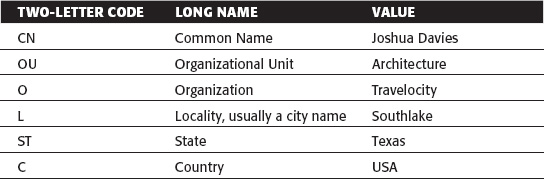

You may even be familiar with the meanings of the terse one- and two-letter codes shown in the example, but in case you aren't, they expand to the long names shown in Table 5-2.

Table 5-2: An Expanded X.509 Distinguished Name

As you can see, this identifies, fairly uniquely, an individual person. In the case of an X.509 certificate, a distinguished name is used to identify the issuer. Here's an example issuer name:

CN = VeriSign Class 3 Extended Validation SSL SGC CA, OU = Terms of use at https://www.verisign.com/rpa (c)06, OU = VeriSign Trust Network, O = VeriSign, Inc., C = US

This is the issuer string on the certificate that identifies the Travelocity.com web site at the time of this writing. As you can see, the CN (common name) doesn't actually identify a person; it identifies an entity. The OU field appears twice and is used to transmit data not actually related to the organizational unit. However, it identifies an issuer well enough for the receiver to decide if it wants to trust it or not. However, see the discussion later in this chapter about the issuerUniqueId field for more on this topic.

You can see this yourself. As way of example, follow these steps:

In FireFox:

- Navigate to a secure page.

- Double-click the lock icon, and click the View button. The Issued By section details the contents of the "issuer" field in the X.509 certificate that the server presented to negotiate the secure connection in the first place.

Using Microsoft's Internet Explorer 8:

- Navigate to a secure page.

- Click the lock icon on the URL bar, select View Certificates. The Certificate dialog appears as shown in Figure 5-3.

- Click the Details tab, and click Issuer.

One thing you may notice about the two distinguished name examples I've given is that not every field appears in each distinguished name because at least some of them are optional. In fact, technically speaking, all of them are optional. If you look at the declaration of the Name type, which issuer is, you see that it's defined generically:

Name ::= CHOICE { RDNSequence } RDNSequence ::= SEQUENCE OF RelativeDistinguishedName RelativeDistinguishedName ::= SET OF AttributeTypeAndValue AttributeTypeAndValue ::= SEQUENCE { type AttributeType, value AttributeValue } AttributeType ::= OBJECT IDENTIFIER AttributeValue ::= ANY DEFINED BY AttributeType

Figure 5-3: Example of an Issuer field

A name is an RDNSequence, which is a SEQUENCE OF another type, the RelativeDistinguishedName. Remember earlier when SEQUENCE was compared to a C struct, which may be confusing because SEQUENCE sounds like a repeating field? Well, SET OF, which RelativeDistinguishedName is defined as, is a repeating field.

What this all means is that a name is a variable-length array of AttributeTypeAndValue structures. The attribute type is an OID, and the attribute value can be any type, depending on its OID. Again, you don't need to care much about the encoding structure of OIDs; you just need to care about their values and what they map to. As you can probably guess, CN, O, OU, L, ST, and C each have their own OID values. They're not represented as string values anywhere in the certificate. These OIDs are shown in Table 5-3.

Table 5-3: DistinguishedName OIDs

Although the actual type of the attribute value of each depends on the OID, all of the OIDs you typically see (within the distinguished name, at least) have attribute values whose types are strings. Notice also that these OIDs are only three bytes long, whereas the OIDs of the algorithm identifiers shown earlier are each nine bytes long. See X.520 for more detail on the attribute type OIDs (as well as many, many more attribute types—distinguished names are permitted to be very detailed, although they're usually relatively simple).

For now, you just have to identify an issuer well enough to make a trust decision, or provide this same information to the user and let the user make this decision. If you've ever come across the error message "The certificate is signed by an unrecognized CA or one you have chosen not to trust" while browsing the web, your browser is telling you that you should take a look at the "issued by" field.

validity

validity Validity

Recall the purpose and concept of validity period—the validity period represents a time window outside of which the certificate should be considered suspect. You've likely come across the error message "The web site's certificate has expired" while browsing. This is actually a much less serious condition than an untrusted issuer. You know that the certificate was valid at some point in the past; it's just due to be resissued. If it's not terribly old, you can probably trust it.

TRACKING CERTIFICATE VALIDITY PERIODS

Keeping track of validity periods and expiration dates, and ensuring that certificates get reissued before their expiration date, can be an onerous responsibility for a website administrator. Expired certificates are a user annoyance when a web server presents one—the user is presented with an ominous error message and given the option to continue or abort. However, in automated communications, such as secured web services, where a program is making a secure connection to another program, certificate expiration can be fatal.

One day your web services are connecting to one another as they should be; the next day they're failing for no apparent reason with a "certificate expired" error message buried in a log file somewhere. No certificate-based library I'm aware of gives you any warning that a certificate is about to expire (as nice as that would be).

One way to get around this is to have all certificates that protect program-to-program services expire on the same day—for instance, you can have all the test environment certificates expire on Feb. 1, and all the production environment certificates expire on Mar. 1. This way, you'll get some warning and when your test environment certificates start expiring and you'll know it's time to start reissuing your production environment certificates.

How is validity represented in X.509, then?

Validity ::= SEQUENCE {

notBefore Time,

notAfter Time }

Time ::= CHOICE {

utcTime UTCTime,

generalTime GeneralizedTime }

There are two Time values, each of which can either be a UTCTime or a GeneralizedTime. Each is a year, followed by a month, a day, an hour, a minute, a second, and the letter Z. The only difference between the two is that generalized time uses a four-digit year and UTCTime a two-digit year. A UTCTime is 13 bytes long; a GeneralizedTime is 15. Lengths are discussed later in the chapter, when representations are covered.

So, with a two-digit year, the client has to do a bit of detective work to figure out if 35 expired a very, very long time ago, or if it will expire in 25 years. Because no X.509 certificates were issued in 1935, it's safe to assume that a year of 35 means 2035. In fact, the specification mandates that all certificates issued before 2050 must use UTCTime, so if the year is less than 50, it's in the 21st century. After the year 2050, CA's are supposed to begin using GeneralizedTime, with a four-digit year. However, having lived through the Y2K "crisis," I have faith that computer programmers will not actually fix this two-digit year problem until a few years before it actually does become a problem—sometime around the year 2080.

subject

subject Name

The subject, like the issuer, is a relative distinguished name. It includes an optional number of identifying fields, hopefully enough to identify the subject of the certificate. But, now that you mention it, who is the subject? If I have a certificate that identifies me, personally, the subject name (the CN field) should be my name, but if I'm connecting to a web site named www.whizbang.com, the subject field should identify that web site somehow.

As it turns out, this is actually poorly specified. The compromise here has been to insert the domain name into the CN field of the subject name and allow the client to compare the domain name it thinks it's connecting to against the domain name listed in the CN field of the certificate's subject. However, this is imperfect. Consider an e-commerce site that controls three different domains: shop.whizbang.com, purchase.whizbang.com and orders.whizbang.com. SSL certificates are expensive to obtain—at least, those issued by reputable CAs—and something of a hassle to maintain. The site administrator has to keep track of expiration dates and ensure that the certificates get reissued within a reasonable timeframe. As the administrator of whizbang.com, you'd really want one certificate that authenticates all of the site's servers. After all, www.whizbang.com almost certainly identifies multiple physical IP addresses.

As a result, it's acceptable for the certificate's subject's CN field to include a wildcard, such as *.whizbang.com. This actually creates other problems. If you can convince a CA to register you a certificate with a subject name including CN=*.com, you can masquerade as any site on the Internet, and the browser has no way of differentiating your certificate from the legitimate owner of the site. Although authorities are smart enough to check for this, security researcher Moxie Marlinspike, in his paper "Null Prefix Attacks Against SSL Certificates," detailed an interesting vulnerability not in the protocol itself but in most implementations of it. An attacker requests a certificate whose common name was *\0.badguy.com. Note the insertion of the null-terminator \0 in the domain name. Because he owns the top-level domain name badguy.com, the CA issues the certificate. However, a C-based client implementation almost certainly loads the common name into a string field and does a strcmp to determine equality—reading the common name as * or "any website". This is something that implementers of the TLS protocol need to be aware of; the length of the string needs to be checked, and null terminators before the actual end of the string should be removed. If you're lucky, the CA checks for this as well. You shouldn't rely on luck, though; as the implementer, make sure you protect your users against lazy CA's.

RFC 2247 extends the X.509 subject name to explicitly include domain-name components, split out according to the DNS hierarchy, so that www.whizbang.com becomes DC=www,DC=whizbang,DC=com. This new DC (domain-name component) attribute has OID 0.9.2342.19200300.100.1.25 and is not particularly common; most sites still instead use the CN field to identify their domain names. This is part of a chicken-and-egg problem; some older clients don't recognize the DC component, so to interoperate with them, sites identify themselves using the CN field. Because so few sites advertise DC components, there's little incentive for clients to recognize it. At the time of this writing, neither Firefox 3.6.3 nor Internet Explorer 8 properly recognize the DC field in the subject name, although RFC 3280 states that recognizing it is mandatory. If the DC field correctly identifies the domain name, but the CN does not (or is missing), a security exception is still reported. The DC field is more common in LDAP-based certificates; perhaps someday in the future, web browsers will make use of it.

A recent Internet-wide security analysis by Qualys Research found "22 million SSL servers with certificates that are completely invalid because they do not match the domain name on which they reside" (see http://www.esecurityplanet.com/features/article.php/3890171/SSL-Certificates-In-Use-Today-Arent-All-Valid.htm), although some of this is likely caused by virtual hosting rather than truly invalid SSL certificates.

subjectPublicKeyInfo

subjectPublicKeyInfo SubjectPublicKeyInfo

Here is the heart of the certificate—the public key that it presents. On the client side, when the certificate is received, you use the issuer, validity period, and the subject field to decide whether you trust the public key well enough to use it to perform a key exchange. If the subject matches the host you think you're connecting to, the certificate hasn't expired, and the issuer is one you trust, you have reasonable assurance that there's no man in the middle and you can go forward with the key exchange and, presumably, trade sensitive information over the now-secured channel.

The definition for SubjectPublicKeyInfo is

SubjectPublicKeyInfo ::= SEQUENCE {

algorithm AlgorithmIdentifier,

subjectPublicKey BIT STRING }

The AlgorithmIdentifier, it should come as no surprise, includes an OID. Two possible values of interest are shown in Table 5-4.

Table 5-4: Public-Key Algorithm OIDs

| ALGORITHM IDENTIFIER | OID |

| RSA | 2A 86 48 86 F7 0D 01 01 01 |

| Diffie-Hellman | 2A 86 48 CE 3E 02 01 |

NOTE Elliptic-curve Diffie-Hellman support in X.509 certificates is examined in Chapter 9.

The public key itself is defined here as a simple bit string. Recall from Chapter 4, though, that you need some pretty specific information in a pretty specific format to do key exchanges, For RSA, for example, you need the modulus n and the public exponent e. So, as it turns out, the BIT STRING here actually encodes another ASN.1 formatted value, whose contents vary depending on the value of the algorithm identifier. For RSA, this is

RSAPublicKey ::= SEQUENCE {

modulus INTEGER, -- n

publicExponent INTEGER -- e -- }

So, after decoding the OID, you then need to ASN.1 decode the bit string as yet another ASN.1 value to extract the actual public key.

If you recall, regular (e.g. non-elliptic-curve) Diffie-Hellman key exchange doesn't involve a public key the way RSA does. There were two parameters needed, though: the generator g and the field parameter p. The contents of the public key field, in this case, is simply:

DHPublicKey ::= INTEGER -- public key, y = g^x mod p

Of course, the public y value is useless to the client without g and p. You might expect to see them in the public key structure, as you see with n in the RSAPublicKey, but instead the Diffie-Hellman generator and group are passed as algorithm parameters. Notice in the declaration of algorithm in SubjectPublicKeyInfo that the type is actually AlgorithmIdentifier. This includes an OID identifying the algorithm, but allows optional parameters to be included:

AlgorithmIdentifier ::= SEQUENCE {

algorithm OBJECT IDENTIFIER,

parameters ANY DEFINED BY algorithm OPTIONAL }

The parameters field is empty for RSA, but for DH, it's defined as

DomainParameters ::= SEQUENCE {

p INTEGER, -- odd prime, p=jq +1

g INTEGER, -- generator, g

q INTEGER, -- factor of p-1

j INTEGER OPTIONAL, -- subgroup factor

validationParms ValidationParms OPTIONAL }

ValidationParms ::= SEQUENCE {

seed BIT STRING,

pgenCounter INTEGER }

HOW TO AVOID A SMALL SUBGROUP ATTACK USING THE DIFFIE-HELLMAN KEY

If you recall the discussion of Diffie-Hellman key exchange in Chapter 3, you may remember that p and g are the only two parameters that you need in order to perform a key exchange. Each side chooses a random secret number a or b, sends the other side y = ga%p, and the receiving side computes yb%p to complete the key agreement (refer back to Chapter 3 if this is still a bit fuzzy). So—you may wonder—what are those extra parameters, q, j, and validationParms for? Well, when p and g are fixed parameters—used over and over for multiple key exchanges—a poorly chosen p value can open the user to an attack called the small subgroup attack, described by Chae Hoon Lim and Pil Joon Lee in their paper, "A Key Recovery Attack on Discrete Log-based Schemes Using a Prime Order Subgroup." The attack itself is mathematically complex, and I won't go into the details here. As it turns out, SSL/TLS ordinarily uses Diffie-Hellman key exchange in such a way that guarding against the small subgroup attack is unnecessary; this will be examined in more detail in Chapter 8. If you're curious, and would like to see more detail on how these parameters may be used to guard against small subgroup attacks, you may refer to RFC 2631.

extensions

extensions [3] EXPLICIT Extensions OPTIONAL

-- If present, version shall be v3

Finally, there is the generic extensions field introduced in X.509v3—in fact, this was the only addition to X.509v3. Certificate extensions, if present—which they almost always are these days—are appended here. extensions is a nested SEQUENCE of object identifiers, optionally followed by data (depending on the object identifier).

This book doesn't go through all the available certificate extensions. RFC 5280, section 4.2 lists all of the standard ones, but be aware that two entities can agree on non-standard extensions as well. There are, however, a handful of particularly important ones.

The extensions type is defined as

Extensions ::= SEQUENCE SIZE (1..MAX) OF Extension

and the extension type itself is defined as

Extension ::= SEQUENCE {

extnID OBJECT IDENTIFIER,

critical BOOLEAN DEFAULT FALSE,

extnValue OCTET STRING }

Each extension has a unique object identifier; this object identifier determines how the extnValue is parsed, or if it's even present. Additionally, there's a critical field. If an extension is marked critical, and the reader doesn't recognize it, it must reject the entire certificate; otherwise, unrecognized extensions can be ignored. Most extensions are not marked critical.

The Subject Alternative Name extension (OID 55 1D 11) is a useful, but not widely used, extension. This extension offers a place to specifically identify a server's domain name; it also supports e-mail addresses, IP addresses, other directory names, and so on. Because the domain name is explicit, the common-name field no longer needs to be assumed to be the domain name. Unfortunately, this extension has failed to catch on, chiefly for the same reason the DC component in the subject name failed to catch on; to support older clients, servers must continue to set the common name to be the same as domain name. (In fact, it's unclear what, if anything, ought to be in the CN component of a certificate's subject when the certificate identifies a web site, if not the domain name.)

There are additional certificate extensions throughout the remainder of this chapter. Each one is encoded according to the Extension structure defined above, and is identified uniquely by an OID. Incidentally, all of the extension OIDs start with 55 1D.

Signed Certificates

Now, as you browse over the list of fields described in the certificate structure from Listing 5-1, you may have noticed that although a signing algorithm is included, a signature isn't. As you recall from Chapter 4, a signature is generated when a byte sequence is hashed and the hash is encrypted using a private key. So, one thing that must be agreed upon before a signature can be generated is exactly which bytes are hashed. In this case, it's the bytes of the certificate structure—technically, the certificate's DER encoding (described later). So, there's another outer structure defined, which includes the certificate, the signature algorithm (again), and the signature value itself, as shown in Listing 5-2.

Listing 5-2: X.509 signed certificate declaration

Certificate ::= SEQUENCE {

tbsCertificate TBSCertificate,

signatureAlgorithm AlgorithmIdentifier,

signatureValue BIT STRING }

The certificate structure defined here is properly referred to as the TBSCertificate. TBS stands for To Be Signed, although the ones examined here have already been signed. If you think about the overall lifecycle of a certificate, this nomenclature makes sense. First, the certificate requester (e.g. the website owner) generates a public/private keypair and wraps up that information in a To-be-signed certificate structure. This is sent off to the CA, which signs it (after verifying it) and returns the whole certificate back, complete with its digital signature.

The signature algorithm is—in fact, must be—the exact same as the OID given in the TBSCertificate itself. The signature, of course, is a bit string. The use of a bit string—the ASN.1 equivalent of a void pointer—runs into the same definitional problem with subjectPublicKeyInfo; the precise contents vary depending on the signature algorithm itself. Therefore, again, the BIT STRING itself is another ASN.1-defined structure, depending on the algorithm identifier.

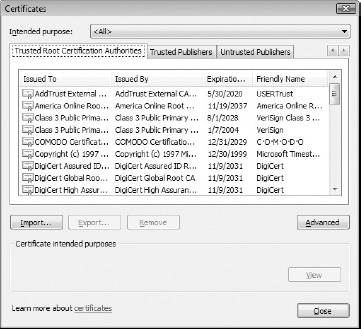

NOTE A certificate can legally be signed by the private key corresponding to the public key contained within it. This sort of certificate is called a self-signed certificate. After all, my certificate is signed by a CA, but who signs their certificates? As a result, all top-level certificates are self-signed this way. How the client decides which self-signed top-level certificates to trust is not defined by the SSL specification. In the context of a web browser, for example, there's always a list of trusted CAs that can be updated by the user.

You can see which CAs your browser trusts. If you're using Internet Explorer 8, for instance, go to Tools  Internet Options

Internet Options  Publishers, and click the Trusted Root Certification Authorities tab, as shown in Figure 5-4:

Publishers, and click the Trusted Root Certification Authorities tab, as shown in Figure 5-4:

Figure 5-4: Sample of trusted root authorities in IE 8

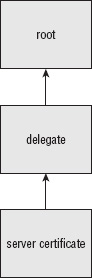

X.509 is designed to allow delegation of signing authority. A top-level CA can issue and sign a certificate to, for instance, a "west coast" authority and an "east coast" authority. These authorities can sign certificates on behalf of the top-level CA. The receiver first verifies that the lowest-level certificate is valid according to the delegated authority's certificate. Then it checks the signature of the delegated authority against that of the root-level authority as illustrated in Figure 5-5.

Figure 5-5: Certificate authority delegation

This way, the verifier—for example, the web client—only needs to keep track of a small number of root CAs. A handful of trusted root authorities can certify other authorities, and the client only has to be aware of a dozen or so root authorities. You can extend this scheme to any level of sub-delegates; the client just goes on checking signatures until it finds a signature issued by an authority it already trusts.

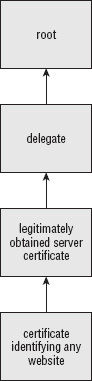

Unfortunately, this system was put in place and used for a while before somebody identified a fatal flaw. The problem is that every certificate includes a public key, and any public key can sign another certificate. Therefore, there's nothing stopping an unscrupulous site administrator from using a regular server certificate to sign another certificate, as shown in Figure 5-6, for example.

Figure 5-6: Illegitimate delegation

As a result, almost all clients are designed to require that each certificate be signed by a trusted authority and to reject delegated signatures.

The Key Usage certificate extension—OID 55 1D 0F—was introduced to allow this sort of delegated signature scheme in a safe way; this (critical) extension encodes a bit string, each of whose eight bits is either set or unset to identify that the public-key contained in this certificate may or may not be used for a particular purpose. Of course, there's nothing stopping an unscrupulous user from using the key for a nonspecified purpose anyway, but the receiver can check the key usage bit and determine whether to allow the sender to do so. The most important bit is bit 5, which, if set, identifies this certificate as a legitimate signing authority. Presumably, the issuing CA only allows this bit to be set if it trusts the requester to be responsible and sign other certificates on behalf of the CA itself.

Summary of X.509 Certificates

I've covered a lot of ground in this section, and it's easy to get lost in all of the details. To summarize: when your browser warns you about certificate errors, it's referring to an X.509 certificate that was presented by the target web site to identify itself. Such a certificate must be presented in order to guard against man-in-the-middle attacks. An X.509 certificate itself is a mapping of an entity name (e.g. a person or a website) to a public key. This mapping has a validity period and is vouched for by a trusted entity called a certificate authority. As long as all of these elements are present, you have a legitimate certificate. The X.509 specification takes it a step further and tells you what order they should be stored in and what form they should take.

Transmitting Certificates with ASN.1 Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER)

Quite a bit has been said so far about the abstract structure of a certificate without discussing how one is actually represented in byte form. The translation of primitive (ASN.1) types to byte representation is described according to a set of rules. Technically, these rules are independent of ASN.1 itself. I mentioned earlier that a certificate is the sort of thing that would probably be represented in XML these days—there is, in fact, a set of rules to encode ASN.1 in XML format! However, by far the most common encoding, and the one that SSL relies on, is called the Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER). The distinguished differentiates the rules from another set called the basic encoding rules. Fundamentally, the distinguished rules are more restrictive than the basic rules. For example, the basic rules allow the encoder to use more bytes than necessary to specify lengths (if the encoder wants all lengths to be encoded in a fixed set of bytes, for example). For the most part, the differences are superficial, and the basic encoding rules (BER) won't be specifically covered here.

The DER describes how to format integers, strings, dates, object identifiers, bit strings, sequences and sets—as well as several others, but these are the ones that are pertinent to the present discussion about X.509 certificates. See X.690 for a complete listing of DER encoding rules.

Encoded Values

Every encoded value is represented as a type, followed by the value's length, followed by the actual contents of the value itself; the representation of the value depends on the type. So, for example, the type integer is byte 02. DER allows for multi-byte types as well—and has complex rules on how to encode and recognize them—but X.509 doesn't need to make use of them and sticks with single-byte types. Therefore, the integer value 5 is encoded, according to DER, as

02 01 05

That's type 2 (integer), one byte in length, value 5. The integer value 65535 is encoded as

02 02 FF FF

That's type 2, two bytes, value 0xFFFF equals 65535. The length byte tells you when to stop reading the value and start looking for another tag.

So far, so good. It's pretty simple. OID's are just as simple to encode. They're stored just like integers, but they have a type of 6 instead of 2. Otherwise, they're encoded the same way: type, length, value. The OID common name (in the subject and issuer distinguished name fields) of 55 04 03 is represented as

06 03 55 04 03

The length byte tells you that there are three bytes of OID.

Strings and Dates

Strings and dates are both encoded similarly. The type code for a date is either 23 or 24; 23 is a generalized—four-digit year—time. 24 is a UTC—two-digit year—time. Although the type actually includes enough information to infer the length—you know that generalized times are 15 digits, and UTC times are 13—for consistency's sake the lengths are included as well. After that, the year, month, day, hour, minute, second and Z are included in ASCII format. So the date Feb. 23, 2010, 6:50:13 is encoded in UTC time as

and is encoded in generalized time as

Strings are also coded this way. However, there are quite a few different string types to account for different byte encodings (among other things). The official specification is actually not proscriptive about which type of string should be used, and you actually see different kinds. However, the most common are IA5Strings (type 22) and printable strings (type 19), which you can treat interchangeably. Given, for example, the country code "US" in a name field, the encoding would be

13 02 55 53

which is the ASCII representation of the string "US."

Bit Strings

So far, DER is pretty straightforward, and everything except bit strings, sequences and sets has been covered. Bit strings are just like strings, with one minor difference. Their type is 3 to distinguish them from printable strings, but the encoding is exactly the same: tag, length, contents. The only difference between bit strings and character strings is that bit strings don't necessarily have to end on an eight-bit boundary, so they have an extra byte to indicate how much padding was included. In practice, this is always 0 because all useful bit patterns are eight-bit aligned anyway.

However, as you recall from the discussion of public key algorithms and signature values, bit strings contain nested ASN.1 structures. All the examples of DER-encoded values examined so far have been able to get away with representing their length with a single byte, but a nested ASN.1 structure is bound to be larger than this. So how are lengths greater than 255 represented?

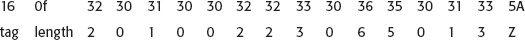

Actually, a single-length byte can only represent 127 byte values. The high-order bit is reserved. If it's 1, then the low order seven bits represent not the length of the value, but the length of the length—that is, how many of the bytes following encode the length of the subsequently following value. So, if a bit string is 512 bytes long, the DER-encoded representation looks like Table 5-5:

Table 5-5: ASN.1 Encoding of Long Values

Technically, a value doesn't have to be a bit string to have a length greater than 127; integers, strings, and OIDs could, at least in theory. In practice, though, this never happens.

Sequences and Sets: Grouping and Nesting ASN.1 Values

So, you're almost ready to start encoding an entire X.509 certificate. There are two missing pieces, though. Notice that there are several sequences nested inside other sequences, and sets nested inside sequences (and sequences nested inside sets...). Sets and sequences are what ASN.1 calls a constructed type—that is, a type containing other types. Technically, they're encoded the same way other values are. They start with a tag, are followed by a variable number of length bytes, and are then followed by their contents. However, for constructed types, the contents themselves are further ASN.1-encoded tags. Sequences are identified by tag 0x30, and sets are identified by tag 0x31. Any tag value whose sixth bit is 1 is a constructed tag and the parser must recognize that it contains additional ASN.1-encoded data.

ASN.1 Explicit Tags

Finally, turn back and look at the definition of the tbsCertificate. Notice that the first field is an optional version number, and the second field is a required serialNumber, and they're both numeric. When parsing a certificate, then, you know for certain that the first value you come across is a number, but you have to check the value of the first value to determine how to interpret the first value! Clearly this is not an optimal way to go about parsing certificates.

To get around this, ASN.1 also allows for explicit tags. Notice in the definition of the tbsCertificate that Version is listed as [0] EXPLICIT.

SEQUENCE {

version [0] EXPLICIT Version DEFAULT v1,

serialNumber CertificateSerialNumber,

So far, tags have been presented as randomly distributed identifiers. Actually, the first two bits of a tag identify its tag class. In X.509 you come across two types of tag classes: universal (00) and context-specific (10). (The other two are application and private and are not used in X.509 certificates.) Context-specific tags are explicit tags. So, to create an explicit tag 0, OR 0 with 1000 0000 (0x80). This is also a constructed tag—its contents are the actual version number—so the sixth bit is set to 1 (OR 0x20).

A Real-World Certificate Example

An example might help clear up any remaining confusion here. To see an actual certificate, you can download one from any SSL-enabled site, or create a new one. The latest version of IE makes it a bit difficult to directly download a certificate, but it's still fairly straightforward with Firefox:

- Navigate to a secure site.

- Click the lock icon.

- Select Security

View Certificate.

View Certificate. - Click the Details tab, shown in figure 5-7, and then click the Export button.

Using OpenSSL to Generate an RSA KeyPair and Certificate

To keep the first example simple, go ahead and just create a new certificate. OpenSSL has a req option that enables you to generate a self-signed certificate. Do so and then examine its contents.

jdavies@home:ssl$ openssl req -x509 -newkey rsa:512 -keyout key.der -keyform der \ -out cert.der -outform der Generating a 512 bit RSA private key .....++++++++++++ ........++++++++++++

writing new private key to 'key.der' Enter PEM pass phrase: Verifying - Enter PEM pass phrase: ---- You are about to be asked to enter information that will be incorporated into your certificate request. What you are about to enter is what is called a Distinguished Name or a DN. There are quite a few fields but you can leave some blank For some fields there will be a default value, If you enter '.', the field will be left blank. ---- Country Name (2 letter code) [AU]:US State or Province Name (full name) [Some-State]:TX Locality Name (eg, city) []:Southlake Organization Name (eg, company) [Internet Widgits Pty Ltd]:Travelocity Organizational Unit Name (eg, section) []:Architecture Common Name (eg, YOUR name) []:Joshua Davies Email Address []:joshua.davies@travelocity.com

Figure 5-7: Downloading/exporting a certificate in Firefox

Notice that it created two output files: a key file, containing the encrypted private key, and a cert file, containing the certificate. It doesn't make much sense to generate a new public key without a private key to go with it. The structure of this key file is revisited later.

Also, notice the parameters: -keyform and -outform. There are two options here, der and pem. der is, unsurprisingly, the ASN.1 DER-encoded representation of the certificate or key file. pem, which stands for Privacy Enhanced Mail, is a Base-64 encoded representation of the DER-encoded certificate with a header and a footer. A pem-encoded certificate file looks like this:

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE---- MIIDUjCCAvygAwIBAgIJAMdcnerewaJQMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBBQUAMIGkMQswCQYD VQQGEwJVUzEOMAwGA1UECBMFVGV4YXMxEjAQBgNVBAcTCVNvdXRobGFrZTEUMBIG ... AwEB/zANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQUFAANBAKf3QiQgbre9DSq4aeED9v0nonEHXPRsU79j l3q/IUMlhmtuZ4SIlNAPvRdZ6DUIvWqVVJbtl5Bm7MKo7KCMarc= -----END CERTIFICATE-----

And a pem-encoded key file looks like this:

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY----- Proc-Type: 4,ENCRYPTED DEK-Info: DES-EDE3-CBC,DF6F51939AF51B22 +cvob7sZl6Ew8/iBqNUF1Q40B14mYzw43cS08/xpzbqtkczYfiQeYN8N4dl8h3tp VzoeCoRKsBKtl89NtpzTJocv33vgcaTFHt1BXBnOPxrQALhyV1x4ADIoW5e7rvsW ... RmyqjA8BH9JeCPzvJlmir55OYB9aCQBTR3+mAlvVrnx5eng1f0YCw/tneXJor3jT IgYBcTpEvug5qeGVl27UA2cI/lcCuNQ0Cjdfztlhhmo= -----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

These structures are more amenable to being transmitted in e-mail than DER-encoded files. SSL always deals in DER-encoded files, though.

NOTE You'll encounter the term PEM every once in a while as you read through the official Internet documentation on certificates. Privacy-Enhanced Mail was the first attempt to apply X.509 certificates in an Internet context, so some of the terminology stuck.

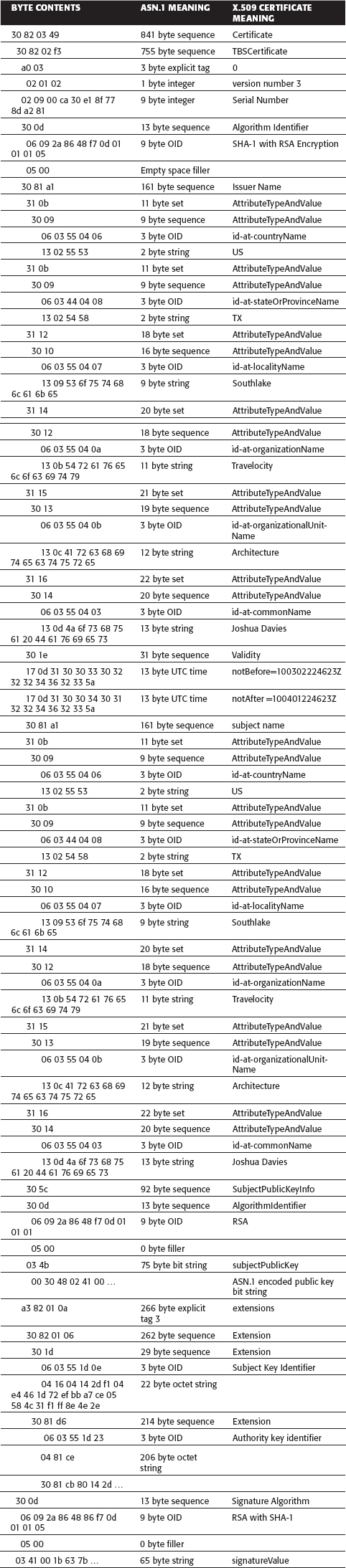

The cert.der file is 845 bytes long. If you did this yourself and used your own name, location, and e-mail information, it might be slightly longer or shorter, but should be in this same neighborhood. The contents of this file are

jdavies@home:ssl$ od -t x1 cert.der 0000000 30 82 03 49 30 82 02 f3 a0 03 02 01 02 02 09 00 0000020 ca 30 e1 8f 77 8d a2 81 30 0d 06 09 2a 86 48 86 0000040 f7 0d 01 01 05 05 00 30 81 a1 31 0b 30 09 06 03 0000060 55 04 06 13 02 55 53 31 0b 30 09 06 03 55 04 08 0000100 13 02 54 58 31 12 30 10 06 03 55 04 07 13 09 53 0000120 6f 75 74 68 6c 61 6b 65 31 14 30 12 06 03 55 04 0000140 0a 13 0b 54 72 61 76 65 6c 6f 63 69 74 79 31 15 0000160 30 13 06 03 55 04 0b 13 0c 41 72 63 68 69 74 65 0000200 63 74 75 72 65 31 16 30 14 06 03 55 04 03 13 0d

0000220 4a 6f 73 68 75 61 20 44 61 76 69 65 73 31 2c 30 0000240 2a 06 09 2a 86 48 86 f7 0d 01 09 01 16 1d 6a 6f 0000260 73 68 75 61 2e 64 61 76 69 65 73 40 74 72 61 76 0000300 65 6c 6f 63 69 74 79 2e 63 6f 6d 30 1e 17 0d 31 0000320 30 30 33 30 32 32 32 34 36 32 33 5a 17 0d 31 30 0000340 30 34 30 31 32 32 34 36 32 33 5a 30 81 a1 31 0b 0000360 30 09 06 03 55 04 06 13 02 55 53 31 0b 30 09 06 0000400 03 55 04 08 13 02 54 58 31 12 30 10 06 03 55 04 0000420 07 13 09 53 6f 75 74 68 6c 61 6b 65 31 14 30 12 0000440 06 03 55 04 0a 13 0b 54 72 61 76 65 6c 6f 63 69 0000460 74 79 31 15 30 13 06 03 55 04 0b 13 0c 41 72 63 0000500 68 69 74 65 63 74 75 72 65 31 16 30 14 06 03 55 0000520 04 03 13 0d 4a 6f 73 68 75 61 20 44 61 76 69 65 0000540 73 31 2c 30 2a 06 09 2a 86 48 86 f7 0d 01 09 01 0000560 16 1d 6a 6f 73 68 75 61 2e 64 61 76 69 65 73 40 0000600 74 72 61 76 65 6c 6f 63 69 74 79 2e 63 6f 6d 30 0000620 5c 30 0d 06 09 2a 86 48 86 f7 0d 01 01 01 05 00 0000640 03 4b 00 30 48 02 41 00 e0 13 38 0f 83 b6 ef 06 0000660 70 f5 5b aa 3a 2b cf 8e 95 ff 91 b1 90 03 52 51 0000700 69 73 de a7 fa 97 fb 56 0d b9 e9 0f e8 30 22 8c 0000720 5e f0 1f 07 f0 dc cc 61 b8 01 0e b1 b0 58 ef b5 0000740 b4 54 16 70 eb 59 b4 bf 02 03 01 00 01 a3 82 01 0000760 0a 30 82 01 06 30 1d 06 03 55 1d 0e 04 16 04 14 0001000 2d f1 04 e4 46 1d 72 ef bb a7 ce 05 58 4c 31 f1 0001020 ff 8e 4e 2e 30 81 d6 06 03 55 1d 23 04 81 ce 30 0001040 81 cb 80 14 2d f1 04 e4 46 1d 72 ef bb a7 ce 05 0001060 58 4c 31 f1 ff 8e 4e 2e a1 81 a7 a4 81 a4 30 81 0001100 a1 31 0b 30 09 06 03 55 04 06 13 02 55 53 31 0b 0001120 30 09 06 03 55 04 08 13 02 54 58 31 12 30 10 06 0001140 03 55 04 07 13 09 53 6f 75 74 68 6c 61 6b 65 31 0001160 14 30 12 06 03 55 04 0a 13 0b 54 72 61 76 65 6c 0001200 6f 63 69 74 79 31 15 30 13 06 03 55 04 0b 13 0c 0001220 41 72 63 68 69 74 65 63 74 75 72 65 31 16 30 14 0001240 06 03 55 04 03 13 0d 4a 6f 73 68 75 61 20 44 61 0001260 76 69 65 73 31 2c 30 2a 06 09 2a 86 48 86 f7 0d 0001300 01 09 01 16 1d 6a 6f 73 68 75 61 2e 64 61 76 69 0001320 65 73 40 74 72 61 76 65 6c 6f 63 69 74 79 2e 63 0001340 6f 6d 82 09 00 ca 30 e1 8f 77 8d a2 81 30 0c 06 0001360 03 55 1d 13 04 05 30 03 01 01 ff 30 0d 06 09 2a 0001400 86 48 86 f7 0d 01 01 05 05 00 03 41 00 1b 63 7b 0001420 f5 13 ef 2e 3d 56 22 3d a2 4c d5 0e 31 8d 0c 25 0001440 bb 24 30 fd a3 20 f5 a3 b5 7d 1b cb 1e a8 bd b0 0001460 ce 78 8b e7 5e 7a ac 66 2c 6d 06 06 e8 e3 06 24 0001500 ca d5 ce 0d 99 1a 7c 37 53 4d d3 be 83

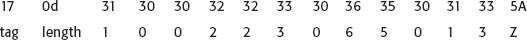

It's worth taking the time to break this file down into its constituent parts. As discussed above, the first byte is a tag. 0x30 is a sequence, as you would expect—this should be a signed certificate sequence. This tag is followed by its length. Because the high-order bit of the length byte (0x82) is 1, this indicates that the next two bytes are the length of the sequence. These bytes are 0x0349, or decimal 841. This looks right—four bytes of the 845-byte file are the sequence and length tag, the remaining 841 are its content. The next byte is another sequence (0x30). Remember that the first element of a signed certificate is a tbsCertificate, which is itself a sequence. Again, the length takes up two bytes of the input stream, and is 0x02F3, or decimal 755. That leaves 86 bytes, toward the end, to contain the signature. Recall from Chapter 4 that this is about the right length for a 512-bit RSA signature value.

Table 5-6 presents an annotated breakdown of this certificate.

Table 5-6: Disassembled Certificate

Note that the interpretation of the second column is automatic and requires no context. However, the interpretation of the third column—the actual certificate contents—requires that you keep close track of the sequences, sets, and so on and match them against the definition. One frustrating thing about ASN.1 DER-encoded strings is that they don't carry any identifying information with them. You can often recognize a DER-encoded file by the 30 byte that (usually) starts it, but if you don't have some external information indicating what type of file it is, you'll never be able to figure out what sort of file you're looking at.

Using OpenSSL to Generate a DSA KeyPair and Certificate

The example certificate in the previous section included an RSA public key. Although this is by far the most common certificate form, OpenSSL allows you to generate certificates that include DSA keys as well. (It does not, at the time of this writing, allow the creation of a certificate with Diffie-Hellman parameters as discussed earlier). The process is slightly more involved, though. First, you must create a set of DSA parameters (p, q, and g):

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ openssl dsaparam 512 -out dsaparam.cer Generating DSA parameters, 512 bit long prime This could take some time ..+................+.....+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++* .......+..+...........+........................................+.....+..+...... ... ........+..+.....+......................+............+....+.+....+............. ... .+.+........+.........................................+....+..+.+.....+..+..+.. ... .+...........+...+..........+.........................+.............+.......... ... +.......+...+............+....+....++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ +++ ++++*

You pass this in to your certificate request:

[jdavies@localhost ssl]$ openssl req -x509 -newkey dsa:dsaparam.cer -keyout \ dsakey.der -keyform der -out dsacert.der -outform der Generating a 512 bit DSA private key writing new private key to 'dsakey.der' Enter PEM pass phrase: Verifying - Enter PEM pass phrase: ----- You are about to be asked to enter information that will be incorporated into your certificate request. What you are about to enter is what is called a Distinguished Name or a DN. There are quite a few fields but you can leave some blank For some fields there will be a default value, If you enter '.', the field will be left blank. ----- Country Name (2 letter code) [GB]:US State or Province Name (full name) [Berkshire]:Texas Locality Name (eg, city) [Newbury]:Southlake Organization Name (eg, company) [My Company Ltd]:Travelocity Organizational Unit Name (eg, section) []:Architecture Common Name (eg, your name or your server's hostname) []:Joshua Davies Email Address []:joshua.davies@travelocity.com

Developing an ASN.1 Parser

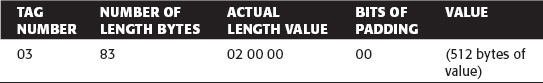

By now, you're probably itching to see some code. You develop code to parse an X.509 certificate in two parts; first, deconstruct the DER-encoded ASN.1 structure into its constituent parts and then interpret these parts as an X.509 certificate. ASN.1-encoded values can be represented naturally as nodes of the form shown in Listing 5-3.

Listing 5-3: "asn1.h" asn1struct definition

struct asn1struct

{

int constructed; // bit 6 of the identifier byte

int tag_class; // bits 7-8 of the identifier byte

int tag; // bits 1-5 of the identifier byte

int length;

const unsigned char *data;

struct asn1struct *children;

struct asn1struct *next;

};

Converting a Byte Stream into an ASN.1 Structure

The first five elements ought to be relatively straightforward if you understood the description of ASN.1 DER in the previous section. The last two are used to navigate the hierarchy. Each asn1struct is part of a linked list of other asn1struct structures, and each one optionally points to the head of another linked list that is its child. So, after parsing, the first part of the certificate is represented in memory as shown in Figure 5-8.

Figure 5-8: Partial illustration of a certificate structure

As you can see, locating a node is a matter of starting at the root, and traversing any number of children or nexts until you reach the one you're looking for. The tree structure is preserved by the use of the children pointers. Define a handful of constants to clarify the code as shown in Listing 5-4.

Listing 5-4: "asn1.h" constants

#define ASN1_CLASS_UNIVERSAL 0 #define ASN1_CLASS_APPLICATION 1 #define ASN1_CONTEXT_SPECIFIC 2 #define ASN1_PRIVATE 3 #define ASN1_BER 0 #define ASN1_BOOLEAN 1 #define ASN1_INTEGER 2 #define ASN1_BIT_STRING 3 #define ASN1_OCTET_STRING 4 #define ASN1_NULL 5 #define ASN1_OBJECT_IDENTIFIER 6 #define ASN1_OBJECT_DESCRIPTOR 7 #define ASN1_INSTANCE_OF_EXTERNAL 8 #define ASN1_REAL 9 #define ASN1_ENUMERATED 10 #define ASN1_EMBEDDED_PPV 11 #define ASN1_UTF8_STRING 12 #define ASN1_RELATIVE_OID 13 // 14 & 15 undefined #define ASN1_SEQUENCE 16 #define ASN1_SET 17 #define ASN1_NUMERIC_STRING 18 #define ASN1_PRINTABLE_STRING 19 #define ASN1_TELETEX_STRING 20 #define ASN1_T61_STRING 20 #define ASN1_VIDEOTEX_STRING 21 #define ASN1_IA5_STRING 22 #define ASN1_UTC_TIME 23 #define ASN1_GENERALIZED_TIME 24 #define ASN1_GRAPHIC_STRING 25 #define ASN1_VISIBLE_STRING 26 #define ASN1_ISO64_STRING 26 #define ASN1_GENERAL_STRING 27 #define ASN1_UNIVERSAL_STRING 28 #define ASN1_CHARACTER_STRING 29 #define ASN1_BMP_STRING 30

The recursive ASN.1 parser routine itself is surprisingly simple (see Listing 5-5).

Listing 5-5: "asn1.c" asn1parse

int asn1parse( const unsigned char *buffer,

int length,

struct asn1struct *top_level_token )

{

unsigned int tag;

unsigned char tag_length_byte;

unsigned long tag_length;

const unsigned char *ptr;

const unsigned char *ptr_begin; struct asn1struct *token; ptr = buffer; token = top_level_token; while ( length ) { ptr_begin = ptr; tag = *ptr; ptr++; length--; // High tag # form (bits 5-1 all == "1"), to encode tags > 31. Not used // in X.509 if ( ( tag & 0x1F ) == 0x1F ) { tag = 0; while ( *ptr & 0x80 ) { tag <<= 8; tag |= *ptr & 0x7F; } } tag_length_byte = *ptr; ptr++; length--; // TODO this doesn't handle indefinite-length encodings (according to // ITU-T X.690, this never occurs in DER, only in BER, which X.509 doesn't // use) if ( tag_length_byte & 0x80 ) { const unsigned char *len_ptr = ptr; tag_length = 0; while ( ( len_ptr - ptr ) < ( tag_length_byte & 0x7F ) ) { tag_length <<= 8; tag_length |= *(len_ptr++); length--; } ptr = len_ptr; } else { tag_length = tag_length_byte; } // TODO deal with "high tag numbers" token->constructed = tag & 0x20;

token->tag_class = ( tag & 0xC0 ) >> 6; token->tag = tag & 0x1F; token->length = tag_length; token->data = ptr; token->children = NULL; token->next = NULL; if ( tag & 0x20 ) { token->length = tag_length + ( ptr - ptr_begin ); token->data = ptr_begin; // Append a child to this tag and recurse into it token->children = ( struct asn1struct * ) malloc( sizeof( struct asn1struct ) ); asn1parse( ptr, tag_length, token->children ); } ptr += tag_length; length -= tag_length; // At this point, we're pointed at the tag for the next token in the buffer. if ( length ) { token->next = ( struct asn1struct * ) malloc( sizeof( struct asn1struct ) ); token = token->next; } } return 0; }

This routine is passed a complete certificate structure, so the whole thing must be resident in memory before this routine is called; this approach might need to be revisited in, say, a handheld device where memory is constrained. It reads through the whole buffer, recognizing ASN.1 structures, and allocating asn1struct instances to represent them.

- Check to see if this is a multi-byte tag:

if ( ( tag & 0x1F ) == 0x1F ) { tag = 0; while ( *ptr & 0x80 ) { tag <<= 8;X.509 doesn't define any of these, but you ought to recognize them for completeness—if for no other reason than to be able to safely ignore them if you happen to come across one.

- Parse out the length of the structure itself; this is always present. If the first byte is a multi-length byte, the processing is a bit complex in part because of the endian-ness issue.

if ( tag_length_byte & 0x80 ) { const unsigned char *len_ptr = ptr; tag_length = 0; while ( ( len_ptr - ptr ) < ( tag_length_byte & 0x7F ) ) { tag_length <<= 8; tag_length |= *(len_ptr++); length--; } ptr = len_ptr; } else { tag_length = tag_length_byte; } - Now that you know the type of tag and the length of its contents—whether they are data or other ASN.1 structures—you can start filling out the asn1struct instance:

token->constructed = tag & 0x20; token->tag_class = ( tag & 0xC0 ) >> 6; token->tag = tag & 0x1F; token->length = tag_length; token->data = ptr; token->children = NULL; token->next = NULL;

- Now the tricky part—if this is a constructed tag, its contents are more ASN.1 structures, which must be appended to the children list. If it is then allocate a new structure to store the children and recursively call this routine:

if ( tag & 0x20 ) { token->length = tag_length + ( ptr - ptr_begin ); - When it returns, or if it wasn't called because the tag was a non-constructed tag, you're either at the end of the data or you're pointing at the next element relative to the one that was just parsed.

if ( length ) { token->next = ( struct asn1struct * ) malloc( sizeof( struct asn1struct ) ); token = token->next; } - If there is another element to parse, allocate space for it, update the target token pointer, and loop back around to process this element. When you're finished the supplied top_level_token structure points to the root of a fully parsed ASN.1 tree.

- Finally, because a lot of memory is allocated by the ASN.1 parsing process, define a function to recursively go through and clean it all up as shown in Listing 5-6.

Listing 5-6: "asn1.c" asn1free

/**

* Recurse through the given node and free all of the memory that was allocated

* by asn1parse. Don't free the "data" pointers, since that points to memory

* that was not allocated by asn1parse.

*/

void asn1free( struct asn1struct *node )

{

if ( !node )

{

return;

}

asn1free( node->children );

free( node->children );

asn1free( node->next );

free( node->next );

}

As you can see, the recursive definition of the asn1struct structure makes cleanup and traversal very straightforward.

The asn1parse Code in Action

To see this code in action, put together a sample main routine as in Listing 5-7 that takes as input a certificate file (or any other ASN.1 DER-encoded file) and output the ASN.1 structure elements.

Listing 5-7: "asn1.c" test routine

#ifdef TEST_ASN1

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] )

{

int certificate_file;

struct stat certificate_file_stat;

unsigned char *buffer, *bufptr;

int buffer_size;

int bytes_read;

struct asn1struct certificate;

if ( argc < 2 )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Usage: %s <certificate file>\n", argv[ 0 ] );

exit( 0 );

}

if ( ( certificate_file = open( argv[ 1 ], O_RDONLY ) ) == −1 )

{

perror( "Unable to open certificate file" );

return 1;

}

// Slurp the whole thing into memory

if ( fstat( certificate_file, &certificate_file_stat ) )

{

perror( "Unable to stat certificate file" );

return 2;

}

buffer_size = certificate_file_stat.st_size;

buffer = ( char * ) malloc( buffer_size );

if ( !buffer ) { perror( "Not enough memory" ); return 3; } bufptr = buffer; while ( bytes_read = read( certificate_file, ( void * ) buffer, certificate_file_stat.st_size ) ) { bufptr += bytes_read; } asn1parse( buffer, buffer_size, &certificate ); asn1show( 0, &certificate ); asn1free( &certificate ); return 0; } #endif

This invokes the asn1show routine in Listing 5-8.

Listing 5-8: "asn1.c" asn1show

static char *tag_names[] = {

"BER", // 0

"BOOLEAN", // 1

"INTEGER", // 2

"BIT STRING", // 3

"OCTET STRING", // 4

"NULL", // 5

"OBJECT IDENTIFIER", // 6

"ObjectDescriptor", // 7

"INSTANCE OF, EXTERNAL", // 8

"REAL", // 9

"ENUMERATED", // 10

"EMBEDDED PPV", // 11

"UTF8String", // 12

"RELATIVE-OID", // 13

"undefined(14)", // 14

"undefined(15)", // 15

"SEQUENCE, SEQUENCE OF", // 16

"SET, SET OF", // 17

"NumericString", // 18

"PrintableString", // 19

"TeletexString, T61String", // 20

"VideotexString", // 21 "IA5String", // 22 "UTCTime", // 23 "GeneralizedTime", // 24 "GraphicString", // 25 "VisibleString, ISO64String", // 26 "GeneralString", // 27 "UniversalString", // 28 "CHARACTER STRING", // 29 "BMPString" // 30 }; void asn1show( int depth, struct asn1struct *certificate ) { struct asn1struct *token; int i; token = certificate; while ( token ) { for ( i = 0; i < depth; i++ ) { printf( " " ); } switch ( token->tag_class ) { case ASN1_CLASS_UNIVERSAL: printf( "%s", tag_names[ token->tag ] ); break; case ASN1_CLASS_APPLICATION: printf( "application" ); break; case ASN1_CONTEXT_SPECIFIC: printf( "context" ); break; case ASN1_PRIVATE: printf( "private" ); break; } printf( " (%d:%d) ", token->tag, token->length ); if ( token->tag_class == ASN1_CLASS_UNIVERSAL ) { switch ( token->tag ) { case ASN1_INTEGER: break;

case ASN1_BIT_STRING: case ASN1_OCTET_STRING: case ASN1_OBJECT_IDENTIFIER: { int i; for ( i = 0; i < token->length; i++ ) { printf( "%.02x ", token->data[ i ] ); } } break; case ASN1_NUMERIC_STRING: case ASN1_PRINTABLE_STRING: case ASN1_TELETEX_STRING: case ASN1_VIDEOTEX_STRING: case ASN1_IA5_STRING: case ASN1_UTC_TIME: case ASN1_GENERALIZED_TIME: case ASN1_GRAPHIC_STRING: case ASN1_VISIBLE_STRING: case ASN1_GENERAL_STRING: case ASN1_UNIVERSAL_STRING: case ASN1_CHARACTER_STRING: case ASN1_BMP_STRING: case ASN1_UTF8_STRING: { char *str_val = ( char * ) malloc( token->length + 1 ); strncpy( str_val, ( char * ) token->data, token->length ); str_val[ token->length ] = 0; printf( " %s", str_val ); free( str_val ); } break; default: break; } } printf( "\n" ); if ( token->children ) { asn1show( depth + 1, token->children ); } token = token->next; } }

If you run this on a DER-encoded certificate file, you get an output similar to Table 5-6 (this was, in fact, how that table was generated). However, when most software saves certificate files, it doesn't do it in DER form; it uses PEM form instead. To use this parsing routine to see the contents of a PEM-encoded file, you can call the base64decode routine from Chapter 1 to convert PEM to DER as in Listing 5-9.

Listing 5-9: "asn1.c" pem_decode

int pem_decode( unsigned char *pem_buffer, unsigned char *der_buffer )

{

unsigned char *pem_buffer_end, *pem_buffer_begin;

unsigned char *bufptr = der_buffer;

int buffer_size;

// Skip first line, which is always "-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----".

if ( strncmp( pem_buffer, "-----BEGIN", 10 ) )

{

fprintf( stderr,

"This does not appear to be a PEM-encoded certificate file\n" );

exit( 0 );

}

pem_buffer_begin = pem_buffer;

pem_buffer= pem_buffer_end = strchr( pem_buffer, '\n' ) + 1;

while ( strncmp( pem_buffer, "-----END", 8 ) )

{

// Find end of line

pem_buffer_end = strchr( pem_buffer, '\n' );

// Decode one line out of pem_buffer into buffer

bufptr += base64_decode( pem_buffer,

( pem_buffer_end - pem_buffer ) -

( ( *( pem_buffer_end - 1 ) == '\r' ) ? 1 : 0 ),

bufptr );

pem_buffer = pem_buffer_end + 1;

}

buffer_size = bufptr - der_buffer;

return buffer_size;

}

Change the test main routine to accept either PEM or DER form:

if ( argc < 3 )

{

fprintf( stderr, "Usage: %s [-der|-pem] <certificate file>\n", argv[ 0 ] );

exit( 0 );

}

if ( ( certificate_file = open( argv[ 2 ], O_RDONLY ) ) == −1 )

{

...

}

if ( !( strcmp( argv[ 1 ], "-pem" ) ) ) { // XXX this overallocates a bit, since it sets aside space for markers, etc. unsigned char *pem_buffer = buffer; buffer = (unsigned char * ) malloc( buffer_size ); buffer_size = pem_decode( pem_buffer, buffer ); free( pem_buffer ); } asn1parse( buffer, buffer_size, &certificate );

You now have a working ASN.1 parser that can be used to read and interpret X.509 certificates. You could stop here, and write code like this:

root->next->next->children->next->children->next->data

to look up the values of specific elements in the tree, but to make your code have any semblance of readability, you should really continue to parse this ASN.1 tree into a proper X.509 structure.

Turning a Parsed ASN.1 Structure into X.509 Certificate Components

The X.509 structure is decidedly more complex than the ASN.1 structure; define it to mirror the ASN.1 definition. To keep the implementation easy to digest, the code is presented for RSA certificates—by far the most common case—and then extended to support DSA and Diffie-Hellman. The structure definitions are shown in Listing 5-10.

Listing 5-10: "x509.h" structure definitions

typedef enum

{

rsa,

dh

}

algorithmIdentifier;

typedef enum

{

md5WithRSAEncryption,

shaWithRSAEncryption

}

signatureAlgorithmIdentifier;

/**

* A name (or "distinguishedName") is a list of attribute-value pairs.

* Instead of keeping track of all of them, just keep track of

* the most interesting ones.

*/

typedef struct