In the previous chapter, we examined the key methods and ways to approach the analysis of an ELF binary in Linux, especially when concerning malware, and ways to detect the presence of a parasite within executable code.

Just as an attacker may patch a binary on disk, they may also patch a running program in memory to achieve similar goals, while avoiding being detected by programs that look for file modification, such as a tripwire. This sort of hot patching of a process image can be used to hijack functions, inject shared libraries, execute parasite shellcode, and so on. These types of infections are often the components needed for memory-resident backdoors, viruses, key loggers, and hidden processes.

Note

An attacker can run sophisticated programs that will run cloaked within an existing process address space. This has been demonstrated with Saruman v0.1, which is available at http://www.bitlackeys.org/#saruman.

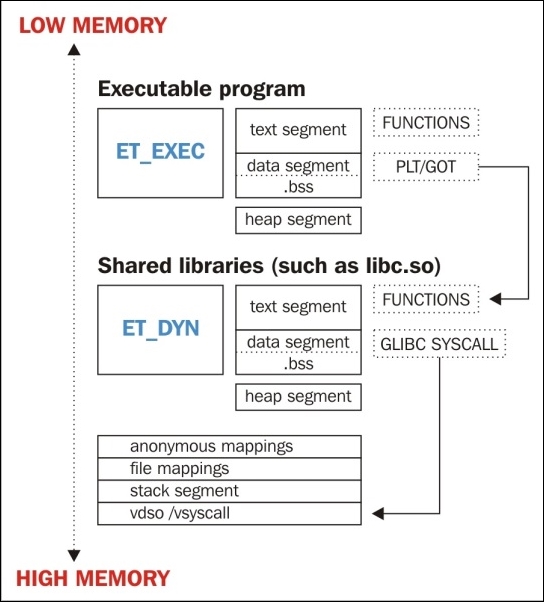

The examination of a process image when performing forensics or runtime analysis is rather similar to looking at a regular ELF binary. There are more segments and overall moving pieces in a process address space, and the ELF executable will undergo some changes, such as runtime relocations, segment alignment, and .bss expansion.

However, in reality, the investigation steps are very similar for an ELF executable and an actual running program. The running program was initially created by the ELF images that are loaded into the address space. Therefore, understanding the ELF format will help understand how a process looks in memory.

One important file on any Linux system is the /proc/$pid/maps file. This file shows the entire process address space of a running program, and it is something that I often parse in order to determine the location of certain files or memory mappings within a process.

On Linux kernels that have the Grsecurity patches, there is a kernel option called

GRKERNSEC_PROC_MEMMAP that, if enabled, will zero out the /proc/$pid/maps file so that you cannot see the address space values. This makes parsing a process from the outside a bit more difficult, and you must rely on other techniques such as parsing the ELF headers and going from there.

Here's an example of the process memory layout of the hello_world program:

$ cat /proc/`pidof hello_world`/maps 00400000-00401000 r-xp 00000000 00:1b 8126525 /home/ryan/hello_world 00600000-00601000 r--p 00000000 00:1b 8126525 /home/ryan/hello_world 00601000-00602000 rw-p 00001000 00:1b 8126525 /home/ryan/hello_world 0174e000-0176f000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap] 7fed9c5a7000-7fed9c762000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 11406096 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so 7fed9c762000-7fed9c961000 ---p 001bb000 08:01 11406096 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so 7fed9c961000-7fed9c965000 r--p 001ba000 08:01 11406096 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so 7fed9c965000-7fed9c967000 rw-p 001be000 08:01 11406096 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so 7fed9c967000-7fed9c96c000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 7fed9c96c000-7fed9c98f000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 11406093 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so 7fed9cb62000-7fed9cb65000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 7fed9cb8c000-7fed9cb8e000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 7fed9cb8e000-7fed9cb8f000 r--p 00022000 08:01 11406093 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so 7fed9cb8f000-7fed9cb90000 rw-p 00023000 08:01 11406093 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so 7fed9cb90000-7fed9cb91000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 7fff0975f000-7fff09780000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack] 7fff097b2000-7fff097b4000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso] ffffffffff600000-ffffffffff601000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vsyscall]

The preceding maps file output shows the process address space of a very simple Hello World program. Let's go over it in several chunks, explaining each part.

The first three lines are the memory mappings for the executable itself. This is quite obvious because it shows the executable path at the end of the file mapping:

00400000-00401000 r-xp 00000000 00:1b 8126525 /home/ryan/hello_world 00600000-00601000 r--p 00000000 00:1b 8126525 /home/ryan/hello_world 00601000-00602000 rw-p 00001000 00:1b 8126525 /home/ryan/hello_world

We can see that:

- The first line is the text segment, which is easy to tell because the permissions are read plus execute

- The second line is the first part of the data segment, which has been marked as read-only due to RELRO (read-only relocation) security protection

- The third mapping is the remaining part of the data segment that is still writable

The heap is typically grown right after the data segment. Before ASLR existed, it was extended from the end of the data segment address. Nowadays, the heap segment is randomly memory-mapped, but it can be found in the maps file right after the end of the data segment:

0174e000-0176f000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap]

There are also anonymous memory mappings that may be created when a call to malloc() requests a chunk of memory that exceeds MMAP_THRESHOLD in size. These types of anonymous memory segments will not be marked with the [heap] label.

The next four lines are the memory mappings for the shared library, libc-2.19.so. Notice that there is a memory mapping marked with no permissions between the text and data segments. This is simply for occupying space in that area so that no other arbitrary memory mappings may be created to use the space between the text and data segments:

7fed9c5a7000-7fed9c762000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 11406096 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so 7fed9c762000-7fed9c961000 ---p 001bb000 08:01 11406096 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so 7fed9c961000-7fed9c965000 r--p 001ba000 08:01 11406096 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so 7fed9c965000-7fed9c967000 rw-p 001be000 08:01 11406096 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so

In addition to regular shared libraries, there is the dynamic linker, which is also technically a shared library. We can see that it is mapped to the address space by looking at the file mappings right after the libc mappings:

7fed9c96c000-7fed9c98f000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 11406093 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so 7fed9cb62000-7fed9cb65000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 7fed9cb8c000-7fed9cb8e000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 7fed9cb8e000-7fed9cb8f000 r--p 00022000 08:01 11406093 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so 7fed9cb8f000-7fed9cb90000 rw-p 00023000 08:01 11406093 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so 7fed9cb90000-7fed9cb91000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

At the end of the maps file, you will see the stack segment, followed by VDSO (short for Virtual Dynamic Shared Object) and vsyscall:

7fff0975f000-7fff09780000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack] 7fff097b2000-7fff097b4000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso] ffffffffff600000-ffffffffff601000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vsyscall]

VDSO is used by glibc to invoke certain system calls that are frequently called and would otherwise create a performance issue. VDSO helps speed this up by executing certain syscalls in userland. The vsyscall page is deprecated on x86_64, but on 32-bit, it accomplishes the same thing as VDSO.

What the process looks like