Copyright © 2016 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

First published: February 2016

Production reference: 1250216

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78216-710-5

Cover image by Lorne Schell (<orange.toaster@gmail.com>)

Author

Ryan "elfmaster" O'Neill

Reviewers

Lubomir Rintel

Kumar Sumeet

Heron Yang

Content Development Editor

Sanjeet Rao

Technical Editor

Mohita Vyas

Copy Editor

Vikrant Phadke

Project Coordinator

Judie Jose

Proofreader

Safis Editing

Indexer

Tejal Daruwale Soni

Graphics

Jason Monteiro

Production Coordinator

Aparna Bhagat

Cover Work

Aparna Bhagat

Ryan "elfmaster" O'Neill is a computer security researcher and software engineer with a background in reverse engineering, software exploitation, security defense, and forensics technologies. He grew up in the computer hacker subculture, the world of EFnet, BBS systems, and remote buffer overflows on systems with an executable stack. He was introduced to system security, exploitation, and virus writing at a young age. His great passion for computer hacking has evolved into a love for software development and professional security research. Ryan has spoken at various computer security conferences, including DEFCON and RuxCon, and also conducts a 2-day ELF binary hacking workshop.

He has an extremely fulfilling career and has worked at great companies such as Pikewerks, Leviathan Security Group, and more recently Backtrace as a software engineer.

Ryan has not published any other books, but he is well known for some of his papers published in online journals such as Phrack and VXHeaven. Many of his other publications can be found on his website at http://www.bitlackeys.org.

First and foremost, I would like to present a very genuine thank you to my mother, Michelle, to whom I have dedicated this book. It all started with her buying me my first computer, followed by a plethora of books, ranging from Unix programming to kernel internals and network security. At one point in my life, I thought I was done with computers forever, but about 5 years later, when I wanted to reignite my passion, I realized that I had thrown my books away! I then found that my mother had secretly saved them for me, waiting for the day I would return to them. Thank you mom, you are wonderful, and I love you.

I would also be very remiss not to acknowledge the most important woman in my life today, who is my twin flame and mother of two of my children. There is no doubt that I would not be where I am in my life and career without you. They say that behind every great man is an even greater woman. This old adage is very true. Thank you Marilyn for bringing immense joy and adventure into my life. I love you.

My father, Brian O'Neill, is a huge inspiration in my life and has taught me so many things about being a man, a father, and a friend. I love you Dad and I will always cherish our philosophical and spiritual connection.

Michael and Jade, thank you both for being such unique and wonderful souls. I love you both.

Lastly, I thank all three of my children: Mick, Jayden, and Jolene. One day, perhaps, you will read this book and know that your old man knows a thing or two about computers, but also that I will always put you guys first in my life. You are all three amazing beings and have imbued my life with such deep meaning and love.

Silvio Cesare is a legendary name in the computer security industry due to his highly innovative and groundbreaking research into many areas, beginning with ELF viruses, and breakthroughs in kernel vulnerability analysis. Thank you Silvio for your mentoring and friendship. I have learned more from you than from any other person in our industry.

Baron Oldenburg was an instrumental part of this book. On several occasions, I nearly gave up due to the time and energy drained, but Baron offered to help with the initial editing and putting the text into the proper format. This took a huge burden off the development process and made this book possible. Thank you Baron! You are a true friend.

Lorne Schell is a true Renaissance man—software engineer, musician, and artist. He was the brilliant hand behind the artwork on the cover of this book. How amazingly well does a Vitruvian Elf fit the description of this book artistically? Thank you Lorne. I am very grateful for your talent and the time you spent on this.

Chad Thunberg, my boss at Leviathan Security Group, was instrumental in making sure that I got the resources and the encouragement necessary to complete this book. Thank you.

All the guys at #bitlackeys on EFnet have my gratitude for their friendship and support.

Lubomir Rintel is a systems programmer based in Brno, Czech Republic. He's a full-time software developer currently working on Linux networking tools. Other than this, he has a history of contributions to many projects, including the Linux kernel and Fedora distribution. After years of being active in the free software community, he can appreciate a good book that covers the subject in a context wider than a manual would. He believes that this is such a book and hopes you enjoy it as much as he did. Also, he likes anteaters.

As of November 2015, Kumar Sumeet has over 4 years of research experience in IT security, during which he has produced a frontier of hacking and spy tools. He holds an MSc in information security from Royal Holloway, University of London. His recent focus area is machine learning techniques for detecting cyber anomalies and to counter threats.

Sumeet currently works as a security consultant for Riversafe, which is a London-based network security and IT data management consultancy firm. Riversafe specializes in some cutting-edge security technologies is also a Splunk Professional Services partner of the year 2015 in the EMEA region. They have completed many large-scale projects and engagements in multiple sectors, including telecommunications, banking and financial markets, energy, and airport authorities.

Sumeet is also a technical reviewer of the book Penetration Testing Using Raspberry Pi, Packt Publishing.

For more information or details about his projects and researches, you can visit his website at https://krsumeet.com or scan this QR code:

Sumeet can also be contacted via e-mail at <contact@krsumeet.com>.

Heron Yang has always been working on creating something people really want. This firm belief of his was first established in high school. Then he continued his journey at National Chiao Tung University and Carnegie Mellon University, where he focused on Computer Science studies. As he cares about building connections between people and fulfilling user needs, he devoted himself to developing prototypes of start-up ideas, new applications or websites, study notes, books, and blogs in the past few years.

For support files and downloads related to your book, please visit www.PacktPub.com.

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at <service@packtpub.com> for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

https://www2.packtpub.com/books/subscription/packtlib

Do you need instant solutions to your IT questions? PacktLib is Packt's online digital book library. Here, you can search, access, and read Packt's entire library of books.

If you have an account with Packt at www.PacktPub.com, you can use this to access PacktLib today and view 9 entirely free books. Simply use your login credentials for immediate access.

Software engineering is the act of creating an invention that exists, lives, and breathes on a microprocessor. We call it a program. Reverse engineering is the act of discovering how exactly that program lives and breathes, and furthermore it is how we can understand, dissect, or modify the behavior of that program using a combination of disassemblers and reversing tools and relying on our hacker instincts to master the target program which we are reverse engineering. We must understand the intricacies of binary formats, memory layout, and the instruction set of the given processor. We therefore become masters of the very life given to a program on a microprocessor. A reverse engineer is skilled in the art of binary mastery. This book is going to give you the proper lessons, insight, and tasks required to become a Linux binary hacker. When someone can call themselves a reverse engineer, they elevate themselves beyond the level of just engineering. A true hacker can not only write code but also dissect code, disassembling the binaries and memory segments in pursuit of modifying the inner workings of a software program; now that is power…

On both a professional and a hobbyist level, I use my reverse engineering skills in the computer security field, whether it is vulnerability analysis, malware analysis, antivirus software, rootkit detection, or virus design. Much of this book will be focused towards computer security. We will analyze memory dumps, reconstruct process images, and explore some of the more esoteric regions of binary analysis, including Linux virus infection and binary forensics. We will dissect malware-infected executables and infect running processes. This book is aimed at explaining the necessary components for reverse engineering in Linux, so we will be going deep into learning ELF (executable and linking format), which is the binary format used in Linux for executables, shared libraries, core dumps, and object files. One of the most significant aspects of this book is the deep insight it gives into the structural complexities of the ELF binary format. The ELF sections, segments, and dynamic linking concepts are vital and exciting chunks of knowledge. We will explore the depths of hacking ELF binaries and see how these skills can be applied to a broad spectrum of work.

The goal of this book is to teach you to be one of the few people with a strong foundation in Linux binary hacking, which will be revealed as a vast topic that opens the door to innovative research and puts you on the cutting edge of low-level hacking in the Linux operating system. You will walk away with valuable knowledge of Linux binary (and memory) patching, virus engineering/analysis, kernel forensics, and the ELF binary format as a whole. You will also gain more insights into program execution and dynamic linking and achieve a higher understanding of binary protection and debugging internals.

I am a computer security researcher, software engineer, and hacker. This book is merely an organized observation and documentation of the research I have done and the foundational knowledge that has manifested as a result.

This knowledge covers a wide span of information that can't be found in any one place on the Internet. This book tries to bring many interrelated topics together into one piece so that it may serve as an introductory manual and reference to the subject of Linux binary and memory hacking. It is by no means a complete reference but does contain a lot of core information to get started with.

Chapter 1, The Linux Environment and Its Tools, gives a brief description of the Linux environment and its tools, which we will be using throughout the book.

Chapter 2, The ELF Binary Format, helps you learn about every major component of the ELF binary format that is used across Linux and most Unix-flavored operating systems.

Chapter 3, Linux Process Tracing, teaches you to use the ptrace system call to read and write to process memory and inject code.

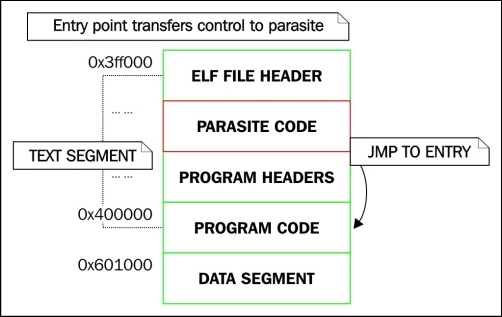

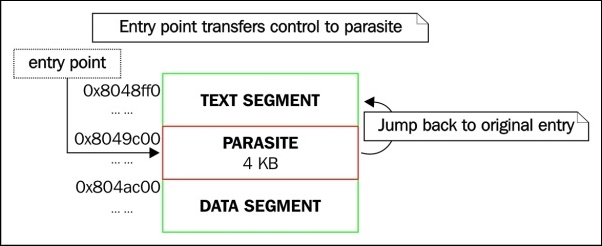

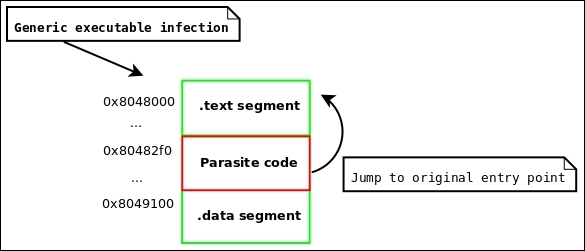

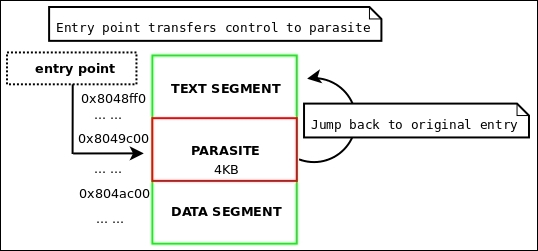

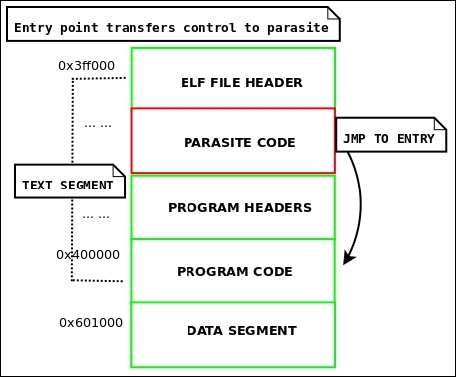

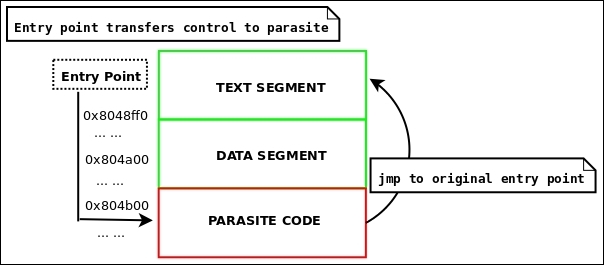

Chapter 4, ELF Virus Technology – Linux/Unix Viruses, is where you discover the past, present, and future of Linux viruses, how they are engineered, and all of the amazing research that surrounds them.

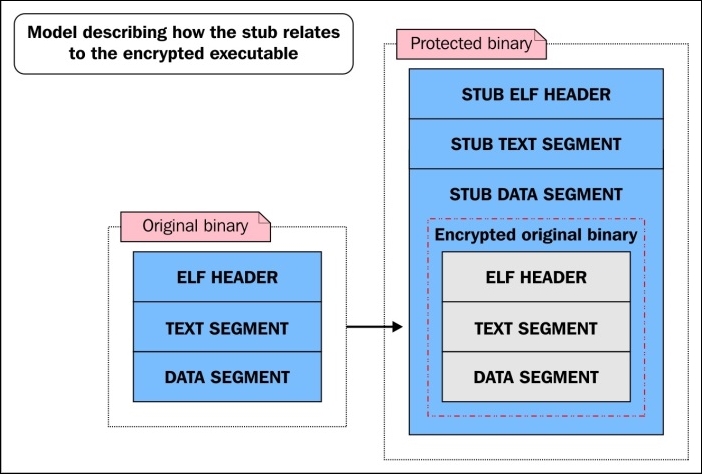

Chapter 5, Linux Binary Protection, explains the basic internals of ELF binary protection.

Chapter 6, ELF Binary Forensics in Linux, is where you learn to dissect ELF objects in search of viruses, backdoors, and suspicious code injection.

Chapter 7, Process Memory Forensics, shows you how to dissect a process address space in search of malware, backdoors, and suspicious code injection that live in the memory.

Chapter 8, ECFS – Extended Core File Snapshot Technology, is an introduction to ECFS, a new open source product for deep process memory forensics.

Chapter 9, Linux /proc/kcore Analysis, shows how to detect Linux kernel malware through memory analysis with /proc/kcore.

The prerequisites for this book are as follows: we will assume that you have a working knowledge of the Linux command line, comprehensive C programming skills, and a very basic grasp on the x86 assembly language (this is helpful but not necessary). There is a saying, "If you can read assembly language then everything is open source."

If you are a software engineer or reverse engineer and want to learn more about Linux binary analysis, this book will provide you with all that you need to implement solutions for binary analysis in areas of security, forensics, and antiviruses. This book is great for both security enthusiasts and system-level engineers. Some experience with the C programming language and the Linux command line is assumed.

In this book, you will find a number of text styles that distinguish between different kinds of information. Here are some examples of these styles and an explanation of their meaning.

Code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles are shown as follows: " There are seven section headers, starting at the offset 0x1118."

A block of code is set as follows:

uint64_t injection_code(void * vaddr)

{

volatile void *mem;

mem = evil_mmap(vaddr,

8192,

PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE|PROT_EXEC,

MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_ANONYMOUS,

-1, 0);

__asm__ __volatile__("int3");

}When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

0xb755a990] changed to [0x8048376]

[+] Patched GOT with PLT stubs

Successfully rebuilt ELF object from memory

Output executable location: dumpme.out

[Quenya v0.1@ELFWorkshop]

quitAny command-line input or output is written as follows:

hacker@ELFWorkshop:~/ workshop/labs/exercise_9$ ./dumpme.out

Feedback from our readers is always welcome. Let us know what you think about this book—what you liked or disliked. Reader feedback is important for us as it helps us develop titles that you will really get the most out of.

To send us general feedback, simply e-mail <feedback@packtpub.com>, and mention the book's title in the subject of your message.

If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, see our author guide at www.packtpub.com/authors.

Now that you are the proud owner of a Packt book, we have a number of things to help you to get the most from your purchase.

You can download the example code files from your account at http://www.packtpub.com for all the Packt Publishing books you have purchased. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you find a mistake in one of our books—maybe a mistake in the text or the code—we would be grateful if you could report this to us. By doing so, you can save other readers from frustration and help us improve subsequent versions of this book. If you find any errata, please report them by visiting http://www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details of your errata. Once your errata are verified, your submission will be accepted and the errata will be uploaded to our website or added to any list of existing errata under the Errata section of that title.

To view the previously submitted errata, go to https://www.packtpub.com/books/content/support and enter the name of the book in the search field. The required information will appear under the Errata section.

Piracy of copyrighted material on the Internet is an ongoing problem across all media. At Packt, we take the protection of our copyright and licenses very seriously. If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, please provide us with the location address or website name immediately so that we can pursue a remedy.

Please contact us at <copyright@packtpub.com> with a link to the suspected pirated material.

We appreciate your help in protecting our authors and our ability to bring you valuable content.

If you have a problem with any aspect of this book, you can contact us at <questions@packtpub.com>, and we will do our best to address the problem.

In this chapter, we will be focusing on the Linux environment as it pertains to our focus throughout this book. Since this book is focused about Linux binary analysis, it makes sense to utilize the native environment tools that come with Linux and to which everyone has access. Linux comes with the ubiquitous binutils already installed, but they can be found at http://www.gnu.org/software/binutils/. They contain a huge selection of tools that are handy for binary analysis and hacking. This is not another book on using IDA Pro. IDA is hands-down the best universal software for reverse engineering of binaries, and I would encourage its use as needed, but we will not be using it in this book. Instead, you will acquire the skills to hop onto virtually any Linux system and have an idea on how to begin hacking binaries with an environment that is already accessible. You can therefore learn to appreciate the beauty of Linux as a true hackers' environment for which there are many free tools available. Throughout the book, we will demonstrate the use of various tools and give a recap on how to use them as we progress through each chapter. Meanwhile, however, let this chapter serve as a primer or reference to these tools and tips within the Linux environment. If you are already very familiar with the Linux environment and its tools for disassembling, debugging, and parsing of ELF files, then you may simply skip this chapter.

Throughout this book, we will be using a variety of free tools that are accessible by anyone. This section will give a brief synopsis of some of these tools for you.

GNU Debugger (GDB) is not only good to debug buggy applications. It can also be used to learn about a program's control flow, change a program's control flow, and modify the code, registers, and data structures. These tasks are common for a hacker who is working to exploit a software vulnerability or is unraveling the inner workings of a sophisticated virus. GDB works on ELF binaries and Linux processes. It is an essential tool for Linux hackers and will be used in various examples throughout this book.

Object dump (objdump) is a simple and clean solution for a quick disassembly of code. It is great for disassembling simple and untampered binaries, but will show its limitations quickly when attempting to use it for any real challenging reverse engineering tasks, especially against hostile software. Its primary weakness is that it relies on the ELF section headers and doesn't perform control flow analysis, which are both limitations that greatly reduce its robustness. This results in not being able to correctly disassemble the code within a binary, or even open the binary at all if there are no section headers. For many conventional tasks, however, it should suffice, such as when disassembling common binaries that are not fortified, stripped, or obfuscated in any way. It can read all common ELF types. Here are some common examples of how to use objdump:

ELF file:

objdump -D <elf_object>

ELF file:

objdump -d <elf_object>

objdump -tT <elf_object>

We will be exploring objdump and other tools in great depth during our introduction to the ELF format in Chapter 2, The ELF Binary Format.

Object copy (Objcopy) is an incredibly powerful little tool that we cannot summarize with a simple synopsis. I recommend that you read the manual pages for a complete description. Objcopy can be used to analyze and modify ELF objects of any kind, although some of its features are specific to certain types of ELF objects. Objcopy is often times used to modify or copy an ELF section to or from an ELF binary.

To copy the .data section from an ELF object to a file, use this line:

objcopy –only-section=.data <infile> <outfile>

The objcopy tool will be demonstrated as needed throughout the rest of this book. Just remember that it exists and can be a very useful tool for the Linux binary hacker.

System call trace (strace) is a tool that is based on the ptrace(2) system call, and it utilizes the PTRACE_SYSCALL request in a loop to show information about the system call (also known as syscalls) activity in a running program as well as signals that are caught during execution. This program can be highly useful for debugging, or just to collect information about what syscalls are being called during runtime.

This is the strace command used to trace a basic program:

strace /bin/ls -o ls.out

The strace command used to attach to an existing process is as follows:

strace -p <pid> -o daemon.out

The initial output will show you the file descriptor number of each system call that takes a file descriptor as an argument, such as this:

SYS_read(3, buf, sizeof(buf));

If you want to see all of the data that was being read into file descriptor 3, you can run the following command:

strace -e read=3 /bin/ls

You may also use -e write=fd to see written data. The strace tool is a great little tool, and you will undoubtedly find many reasons to use it.

library trace (ltrace) is another neat little tool, and it is very similar to strace. It works similarly, but it actually parses the shared library-linking information of a program and prints the library functions being used.

You may see system calls in addition to library function calls with the -S flag. The ltrace command is designed to give more granular information, since it parses the dynamic segment of the executable and prints actual symbols/functions from shared and static libraries:

ltrace <program> -o program.out

Function trace (ftrace) is a tool designed by me. It is similar to ltrace, but it also shows calls to functions within the binary itself. There was no other tool I could find publicly available that could do this in Linux, so I decided to code one. This tool can be found at https://github.com/elfmaster/ftrace. A demonstration of this tool is given in the next chapter.

The readelf command is one of the most useful tools around for dissecting ELF binaries. It provides every bit of the data specific to ELF necessary for gathering information about an object before reverse engineering it. This tool will be used often throughout the book to gather information about symbols, segments, sections, relocation entries, dynamic linking of data, and more. The readelf command is the Swiss Army knife of ELF. We will be covering it in depth as needed, during Chapter 2, The ELF Binary Format, but here are a few of its most commonly used flags:

readelf -S <object>

readelf -l <object>

readelf -s <object>

ELF file header data:

readelf -e <object>

readelf -r <object>

readelf -d <object>

ERESI project (http://www.eresi-project.org) contains a suite of many tools that are a Linux binary hacker's dream. Unfortunately, many of them are not kept up to date and aren't fully compatible with 64-bit Linux. They do exist for a variety of architectures, however, and are undoubtedly the most innovative single collection of tools for the purpose of hacking ELF binaries that exist today. Because I personally am not really familiar with using the ERESI project's tools, and because they are no longer kept up to date, I will not be exploring their capabilities within this book. However, be aware that there are two Phrack articles that demonstrate the innovation and powerful features of the ERESI tools:

Linux has many files, devices, and /proc entries that are very helpful for the avid hacker and reverse engineer. Throughout this book, we will be demonstrating the usefulness of many of these files. Here is a description of some of the commonly used ones throughout the book.

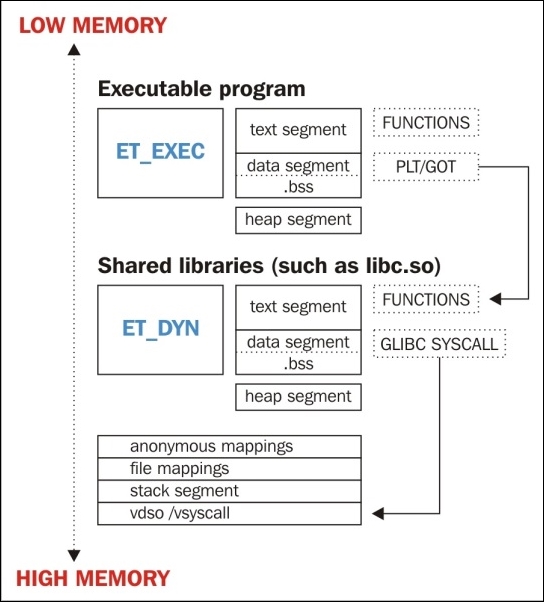

/proc/<pid>/maps file contains the layout of a process image by showing each memory mapping. This includes the executable, shared libraries, stack, heap, VDSO, and more. This file is critical for being able to quickly parse the layout of a process address space and is used more than once throughout this book.

The /proc/kcore is an entry in the proc filesystem that acts as a dynamic core file of the Linux kernel. That is, it is a raw dump of memory that is presented in the form of an ELF core file that can be used by GDB to debug and analyze the kernel. We will explore /proc/kcore in depth in Chapter 9, Linux /proc/kcore Analysis.

This file is available on almost all Linux distributions and is very useful for kernel hackers. It contains every symbol for the entire kernel.

The kallsyms is very similar to System.map, except that it is a /proc entry that means that it is maintained by the kernel and is dynamically updated. Therefore, if any new LKMs are installed, the symbols will be added to /proc/kallsyms on the fly. The /proc/kallsyms contains at least most of the symbols in the kernel and will contain all of them if specified in the CONFIG_KALLSYMS_ALL kernel config.

The iomem is a useful proc entry as it is very similar to /proc/<pid>/maps, but for all of the system memory. If, for instance, you want to know where the kernel's text segment is mapped in the physical memory, you can search for the Kernel string and you will see the code/text segment, the data segment, and the bss segment:

$ grep Kernel /proc/iomem 01000000-016d9b27 : Kernel code 016d9b28-01ceeebf : Kernel data 01df0000-01f26fff : Kernel bss

Extended core file snapshot (ECFS) is a special core dump technology that was specifically designed for advanced forensic analysis of a process image. The code for this software can be found at https://github.com/elfmaster/ecfs. Also, Chapter 8, ECFS – Extended Core File Snapshot Technology, is solely devoted to explaining what ECFS is and how to use it. For those of you who are into advanced memory forensics, you will want to pay close attention to this.

The dynamic loader/linker and linking concepts are inescapable components involved in the process of program linking and execution. Throughout this book, you will learn a lot about these topics. In Linux, there are quite a few ways to alter the dynamic linker's behavior that can serve the binary hacker in many ways. As we move through the book, you will begin to understand the process of linking, relocations, and dynamic loading (program interpreter). Here are a few linker-related attributes that are useful and will be used throughout the book.

The LD_PRELOAD environment variable can be set to specify a library path that should be dynamically linked before any other libraries. This has the effect of allowing functions and symbols from the preloaded library to override the ones from the other libraries that are linked afterwards. This essentially allows you to perform runtime patching by redirecting shared library functions. As we will see in later chapters, this technique can be used to bypass anti-debugging code and for userland rootkits.

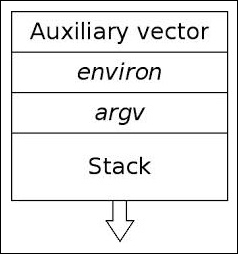

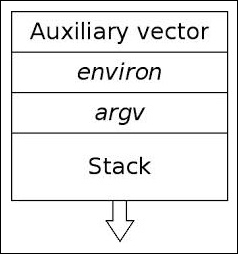

This environment variable tells the program loader to display the program's auxiliary vector during runtime. The auxiliary vector is information that is placed on the program's stack (by the kernel's ELF loading routine), with information that is passed to the dynamic linker with certain information about the program. We will examine this much more closely in Chapter 3, Linux Process Tracing, but the information might be useful for reversing and debugging. If, for instance, you want to get the memory address of the VDSO page in the process image (which can also be obtained from the maps file, as shown earlier) you have to look for AT_SYSINFO.

Here is an example of the auxiliary vector with LD_SHOW_AUXV:

$ LD_SHOW_AUXV=1 whoami AT_SYSINFO: 0xb7779414 AT_SYSINFO_EHDR: 0xb7779000 AT_HWCAP: fpu vme de pse tsc msr pae mce cx8 apic sep mtrr pge mca cmov pat pse36 clflush mmx fxsr sse sse2 AT_PAGESZ: 4096 AT_CLKTCK: 100 AT_PHDR: 0x8048034 AT_PHENT: 32 AT_PHNUM: 9 AT_BASE: 0xb777a000 AT_FLAGS: 0x0 AT_ENTRY: 0x8048eb8 AT_UID: 1000 AT_EUID: 1000 AT_GID: 1000 AT_EGID: 1000 AT_SECURE: 0 AT_RANDOM: 0xbfb4ca2b AT_EXECFN: /usr/bin/whoami AT_PLATFORM: i686 elfmaster

The auxiliary vector will be covered in more depth in Chapter 2, The ELF Binary Format.

Linker scripts are a point of interest to us because they are interpreted by the linker and help shape a program's layout with regard to sections, memory, and symbols. The default linker script can be viewed with ld -verbose.

The ld linker program has a complete language that it interprets when it is taking input files (such as relocatable object files, shared libraries, and header files), and it uses this language to determine how the output file, such as an executable program, will be organized. For instance, if the output is an ELF executable, the linker script will help determine what the layout will be and what sections will exist in which segments. Here is another instance: the .bss section is always at the end of the data segment; this is determined by the linker script. You might be wondering how this is interesting to us. Well! For one, it is important to have some insights into the linking process during compile time. The gcc relies on the linker and other programs to perform this task, and in some instances, it is important to be able to have control over the layout of the executable file. The ld command language is quite an in-depth language and is beyond the scope of this book, but it is worth checking out. And while reverse engineering executables, remember that common segment addresses may sometimes be modified, and so can other portions of the layout. This indicates that a custom linker script is involved. A linker script can be specified with gcc using the -T flag. We will look at a specific example of using a linker script in Chapter 5, Linux Binary Protection.

We just touched upon some fundamental aspects of the Linux environment and the tools that will be used most commonly in the demonstrations from each chapter. Binary analysis is largely about knowing the tools and resources that are available for you and how they all fit together. We only briefly covered the tools, but we will get an opportunity to emphasize the capabilities of each one as we explore the vast world of Linux binary hacking in the following chapters. In the next chapter, we will delve into the internals of the ELF binary format and cover many interesting topics, such as dynamic linking, relocations, symbols, sections, and more.

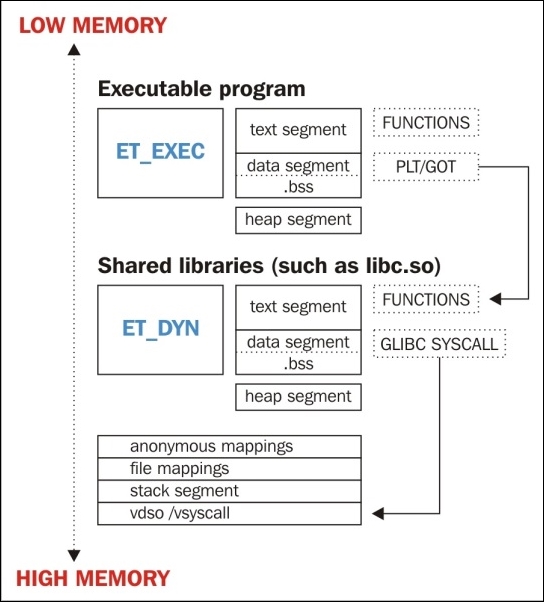

In order to reverse-engineer Linux binaries, you must understand the binary format itself. ELF has become the standard binary format for Unix and Unix-flavor OSes. In Linux, BSD variants, and other OSes, the ELF format is used for executables, shared libraries, object files, coredump files, and even the kernel boot image. This makes ELF very important to learn for those who want to better understand reverse engineering, binary hacking, and program execution. Binary formats such as ELF are not generally a quick study, and to learn ELF requires some degree of application of the different components that you learn as you go. Real, hands-on experience is necessary to achieve proficiency. The ELF format is complicated and dry, but can be learned with some enjoyment when applying your developing knowledge of it in reverse engineering and programming tasks. ELF is really quite an incredible composition of computer science at work, with program loading, dynamic linking, symbol table lookups, and many other tightly orchestrated components.

I believe that this chapter is perhaps the most important in this entire book because it will give the reader a much greater insight into topics pertaining to how a program is actually mapped out on disk and loaded into memory. The inner workings of program execution are complicated, and understanding it is valuable knowledge to the aspiring binary hacker, reverse engineer, or low-level programmer. In Linux, program execution implies the ELF binary format.

My approach to learning ELF is through investigation of the ELF specifications as any Linux reverse engineer should, and then applying each aspect of what we learn in a creative way. Throughout this book, you will visit many facets of ELF and see how knowledge of it is pertinent to viruses, process-memory forensics, binary protection, rootkits, and more.

In this chapter, you will cover the following ELF topics:

An ELF file may be marked as one of the following types:

ET_NONE: This is an unknown type. It indicates that the file type is unknown, or has not yet been defined.ET_REL: This is a relocatable file. ELF type relocatable means that the file is marked as a relocatable piece of code or sometimes called an object file. Relocatable object files are generally pieces of Position independent code (PIC) that have not yet been linked into an executable. You will often see .o files in a compiled code base. These are the files that hold code and data suitable for creating an executable file.ET_EXEC: This is an executable file. ELF type executable means that the file is marked as an executable file. These types of files are also called programs and are the entry point of how a process begins running.ET_DYN: This is a shared object. ELF type dynamic means that the file is marked as a dynamically linkable object file, also known as shared libraries. These shared libraries are loaded and linked into a program's process image at runtime.ET_CORE: This is an ELF type core that marks a core file. A core file is a dump of a full process image during the time of a program crash or when the process has delivered an SIGSEGV signal (segmentation violation). GDB can read these files and aid in debugging to determine what caused the program to crash.If we look at an ELF file with the command readelf -h, we can view the initial ELF file header. The ELF file header starts at the 0 offset of an ELF file and serves as a map to the rest of the file. Primarily, this header marks the ELF type, the architecture, and the entry point address where execution is to begin, and provides offsets to the other types of ELF headers (section headers and program headers), which will be explained in depth later. More of the file header will be understood once we explain the meaning of section headers and program headers. Looking at the ELF(5) man page in Linux shows us the ELF header structure:

#define EI_NIDENT 16

typedef struct {

unsigned char e_ident[EI_NIDENT];

uint16_t e_type;

uint16_t e_machine;

uint32_t e_version;

ElfN_Addr e_entry;

ElfN_Off e_phoff;

ElfN_Off e_shoff;

uint32_t e_flags;

uint16_t e_ehsize;

uint16_t e_phentsize;

uint16_t e_phnum;

uint16_t e_shentsize;

uint16_t e_shnum;

uint16_t e_shstrndx;

} ElfN_Ehdr;Later in this chapter, we will see how to utilize the fields in this structure to map out an ELF file with a simple C program. First, we will continue looking at the other types of ELF headers that exist.

ELF program headers are what describe segments within a binary and are necessary for program loading. Segments are understood by the kernel during load time and describe the memory layout of an executable on disk and how it should translate to memory. The program header table can be accessed by referencing the offset found in the initial ELF header member called e_phoff (program header table offset), as shown in the ElfN_Ehdr structure in display 1.7.

There are five common program header types that we will discuss here. Program headers describe the segments of an executable file (shared libraries included) and what type of segment it is (that is, what type of data or code it is reserved for). First, let's take a look at the Elf32_Phdr structure that makes up a program header entry in the program header table of a 32-bit ELF executable.

Here's the Elf32_Phdr struct:

typedef struct {

uint32_t p_type; (segment type)

Elf32_Off p_offset; (segment offset)

Elf32_Addr p_vaddr; (segment virtual address)

Elf32_Addr p_paddr; (segment physical address)

uint32_t p_filesz; (size of segment in the file)

uint32_t p_memsz; (size of segment in memory)

uint32_t p_flags; (segment flags, I.E execute|read|read)

uint32_t p_align; (segment alignment in memory)

} Elf32_Phdr;An executable will always have at least one PT_LOAD type segment. This type of program header is describing a loadable segment, which means that the segment is going to be loaded or mapped into memory.

For instance, an ELF executable with dynamic linking will generally contain the following two loadable segments (of type PT_LOAD):

The preceding two segments are going to be mapped into memory and aligned in memory by the value stored in p_align. I recommend reading the ELF man pages in Linux to understand all of the members in a Phdr structure as they describe the layout of both the segments in the file as well as in memory.

Program headers are primarily there to describe the layout of a program for when it is executing and in memory. We will be utilizing Phdrs later in this chapter to demonstrate what they are and how to use them in reverse engineering software.

The text segment (also known as the code segment) will generally have segment permissions set as PF_X | PF_R (READ+EXECUTE).

The data segment will generally have segment permissions set to PF_W | PF_R (READ+WRITE).

A file infected with a polymorphic virus might have changed these permissions in some way such as modifying the text segment to be writable by adding the PF_W flag into the program header's segment flags (p_flags).

The dynamic segment is specific to executables that are dynamically linked and contains information necessary for the dynamic linker. This segment contains tagged values and pointers, including but not limited to the following:

Following is a complete list of the tag names:

|

Tag name |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Address of symbol hash table |

|

|

Address of string table |

|

| |

|

|

Address of Rela relocs table |

|

|

Size in bytes of Rela table |

|

|

Size in bytes of a Rela table entry |

|

|

Size in bytes of string table |

|

|

Size in bytes of string table |

|

|

Size in bytes of string table |

|

|

Size in bytes of a symbol table entry |

|

|

Address of the initialization function |

|

|

Address of the termination function |

|

|

String table offset to name of shared object |

|

|

String table offset to library search path |

|

|

Alert linker to search this shared object before the executable for symbols |

|

|

Address of Rel relocs table |

|

|

Size in bytes of Rel table |

|

|

Size in bytes of a Rel table entry |

|

|

Type of reloc the PLT refers (Rela or Rel) |

|

|

Undefined use for debugging |

|

|

Absence of this indicates that no relocs should apply to a nonwritable segment |

|

|

Address of reloc entries solely for the PLT |

|

|

Instructs the dynamic linker to process all relocs before transferring control to the executable |

|

|

String table offset to library search path |

The dynamic segment contains a series of structures that hold relevant dynamic linking information. The d_tag member controls the interpretation of d_un.

The 32-bit ELF dynamic struct:

typedef struct {

Elf32_Sword d_tag;

union {

Elf32_Word d_val;

Elf32_Addr d_ptr;

} d_un;

} Elf32_Dyn;

extern Elf32_Dyn _DYNAMIC[];We will explore more about dynamic linking later in this chapter.

A segment of type PT_NOTE may contain auxiliary information that is pertinent to a specific vendor or system. Following is a definition of PT_NOTE from the formal ELF specification:

Sometimes a vendor or system builder needs to mark an object file with special information that other programs will check for conformance, compatibility, and so on. Sections of type SHT_NOTE and program header elements of type PT_NOTE can be used for this purpose. The note information in sections and program header elements holds any number of entries, each of which is an array of 4-byte words in the format of the target processor. Labels appear below to help explain note information organization, but they are not part of the specification.

A point of interest: because of the fact that this segment is only used for OS specification information, and is actually not necessary for an executable to run (since the system will just assume the executable is native either way), this segment becomes an interesting place for virus infection, although not necessarily the most practical way to go about it due to size constraints. Some information on NOTE segment infections can be found at http://vxheavens.com/lib/vhe06.html.

This small segment contains only the location and size to a null terminated string describing where the program interpreter is; for instance, /lib/linux-ld.so.2 is generally the location of the dynamic linker, which is also the program interpreter.

This segment contains the location and size of the program header table itself. The Phdr table contains all of the Phdr's describing the segments of the file (and in the memory image).

Consult the ELF(5) man pages or the ELF specification paper to see all possible Phdr types. We have covered the most commonly seen ones that are vital to program execution or that we will be seeing most commonly in our reverse engineering endeavors.

We can use the readelf -l <filename> command to view a file's Phdr table:

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x8049a30

There are 9 program headers, starting at offset 52

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

PHDR 0x000034 0x08048034 0x08048034 0x00120 0x00120 R E 0x4

INTERP 0x000154 0x08048154 0x08048154 0x00013 0x00013 R 0x1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib/ld-linux.so.2]

LOAD 0x000000 0x08048000 0x08048000 0x1622c 0x1622c R E 0x1000

LOAD 0x016ef8 0x0805fef8 0x0805fef8 0x003c8 0x00fe8 RW 0x1000

DYNAMIC 0x016f0c 0x0805ff0c 0x0805ff0c 0x000e0 0x000e0 RW 0x4

NOTE 0x000168 0x08048168 0x08048168 0x00044 0x00044 R 0x4

GNU_EH_FRAME 0x016104 0x0805e104 0x0805e104 0x0002c 0x0002c R 0x4

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000 0x00000 RW 0x4

GNU_RELRO 0x016ef8 0x0805fef8 0x0805fef8 0x00108 0x00108 R 0x1We can see the entry point of the executable as well as some of the different segment types we just finished discussing. Notice the offsets to the right of the permission flags and alignment flags of the two first PT_LOAD segments.

The text segment is READ+EXECUTE and the data segment is READ+WRITE, and both segments have an alignment of 0x1000 or 4,096 which is a page size on a 32-bit executable, and this is for alignment during program loading.

Now that we've looked at what program headers are, it is time to look at section headers. I really want to point out here the distinction between the two; I often hear people calling sections, segments, and vice versa. A section is not a segment. Segments are necessary for program execution, and within each segment, there is either code or data divided up into sections. A section header table exists to reference the location and size of these sections and is primarily for linking and debugging purposes. Section headers are not necessary for program execution, and a program will execute just fine without having a section header table. This is because the section header table doesn't describe the program memory layout. That is the responsibility of the program header table. The section headers are really just complimentary to the program headers. The readelf –l command will show which sections are mapped to which segments, which helps to visualize the relationship between sections and segments.

If the section headers are stripped (missing from the binary), that doesn't mean that the sections are not there; it just means that they can't be referenced by section headers and less information is available for debuggers and disassembler programs.

Each section contains either code or data of some type. The data could range from program data, such as global variables, or dynamic linking information that is necessary for the linker. Now, as mentioned previously, every ELF object has sections, but not all ELF objects have section headers, primarily when someone has deliberately removed the section header table, which is not the default.

Usually, this is because the executable has been tampered with (for example, the section headers have been stripped so that debugging is harder). All of GNU's binutils such as objcopy, objdump, and other tools such as gdb rely on the section headers to locate symbol information that is stored in the sections specific to containing symbol data. Without section headers, tools such as gdb and objdump are nearly useless.

Section headers are convenient to have for granular inspection over what parts or sections of an ELF object we are viewing. In fact, section headers make reverse engineering a lot easier since they provide us with the ability to use certain tools that require them. For instance, if the section header table is stripped, then we can't access a section such as .dynsym, which contains imported/exported symbols describing function names and offsets/addresses.

Even if a section header table has been stripped from an executable, a moderate reverse engineer can actually reconstruct a section header table (and even part of a symbol table) by getting information from certain program headers since these will always exist in a program or shared library. We discussed the dynamic segment earlier and the different DT_TAG that contain information about the symbol table and relocation entries. We can use this to reconstruct other parts of the executable as shown in Chapter 8, ECFS – Extended Core File Snapshot Technology.

The following is what a 32-bit ELF section header looks like:

typedef struct {

uint32_t sh_name; // offset into shdr string table for shdr name

uint32_t sh_type; // shdr type I.E SHT_PROGBITS

uint32_t sh_flags; // shdr flags I.E SHT_WRITE|SHT_ALLOC

Elf32_Addr sh_addr; // address of where section begins

Elf32_Off sh_offset; // offset of shdr from beginning of file

uint32_t sh_size; // size that section takes up on disk

uint32_t sh_link; // points to another section

uint32_t sh_info; // interpretation depends on section type

uint32_t sh_addralign; // alignment for address of section

uint32_t sh_entsize; // size of each certain entries that may be in section

} Elf32_Shdr;Let's take a look at some of the most important sections and section types, once again allowing room to study the ELF(5) man pages and the official ELF specification for more detailed information about the sections.

The .text section is a code section that contains program code instructions. In an executable program where there are also Phdr's, this section would be within the range of the text segment. Because it contains program code, it is of section type SHT_PROGBITS.

The rodata section contains read-only data such as strings from a line of C code, such as the following command are stored in this section:

printf("Hello World!\n");This section is read-only and therefore must exist in a read-only segment of an executable. So you will find .rodata within the range of the text segment (not the data segment). Because this section is read-only, it is of type SHT_PROGBITS.

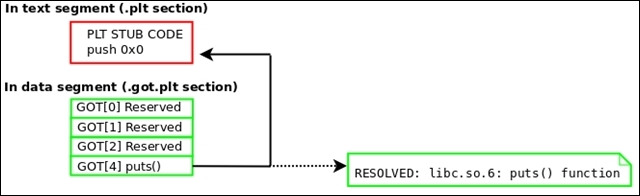

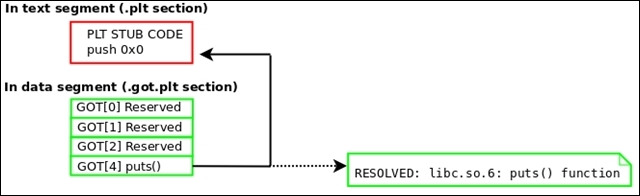

The procedure linkage table (PLT) will be discussed in depth later in this chapter, but it contains code necessary for the dynamic linker to call functions that are imported from shared libraries. It resides in the text segment and contains code, so it is marked as type SHT_PROGBITS.

The data section, not to be confused with the data segment, will exist within the data segment and contain data such as initialized global variables. It contains program variable data, so it is marked SHT_PROGBITS.

The bss section contains uninitialized global data as part of the data segment and therefore takes up no space on disk other than 4 bytes, which represents the section itself. The data is initialized to zero at program load time and the data can be assigned values during program execution. The bss section is marked SHT_NOBITS since it contains no actual data.

The Global offset table (GOT) section contains the global offset table. This works together with the PLT to provide access to imported shared library functions and is modified by the dynamic linker at runtime. This section in particular is often abused by attackers who gain a pointer-sized write primitive in heap or .bss exploits. We will discuss this in the ELF Dynamic Linking section of this chapter. This section has to do with program execution and therefore is marked SHT_PROGBITS.

The dynsym section contains dynamic symbol information imported from shared libraries. It is contained within the text segment and is marked as type SHT_DYNSYM.

The dynstr section contains the string table for dynamic symbols that has the name of each symbol in a series of null terminated strings.

Relocation sections contain information about how parts of an ELF object or process image need to be fixed up or modified at linking or runtime. We will discuss more about relocations in the ELF Relocations section of this chapter. Relocation sections are marked as type SHT_REL since they contain relocation data.

The hash section, sometimes called .gnu.hash, contains a hash table for symbol lookup. The following hash algorithm is used for symbol name lookups in Linux ELF:

uint32_t

dl_new_hash (const char *s)

{

uint32_t h = 5381;

for (unsigned char c = *s; c != '\0'; c = *++s)

h = h * 33 + c;

return h;

}The symtab section contains symbol information of type ElfN_Sym, which we will analyze more closely in the ELF symbols and relocations section of this chapter. The symtab section is marked as type SHT_SYMTAB as it contains symbol information.

The .strtab section contains the symbol string table that is referenced by the st_name entries within the ElfN_Sym structs of .symtab and is marked as type SHT_STRTAB since it contains a string table.

The shstrtab section contains the section header string table that is a set of null terminated strings containing the names of each section, such as .text, .data, and so on. This section is pointed to by the ELF file header entry called e_shstrndx that holds the offset of .shstrtab. This section is marked SHT_STRTAB since it contains a string table.

The .ctors (constructors) and .dtors (destructors) sections contain function pointers to initialization and finalization code that is to be executed before and after the actual main() body of program code.

The __constructor__ function attribute is sometimes used by hackers and virus writers to implement a function that performs an anti-debugging trick such as calling PTRACE_TRACEME so that the process traces itself and no debuggers can attach to it. This way the anti-debugging code gets executed before the program enters into main().

There are many other section names and types, but we have covered most of the primary ones found in a dynamically linked executable. One can now visualize how an executable is laid out with both phdrs and shdrs.

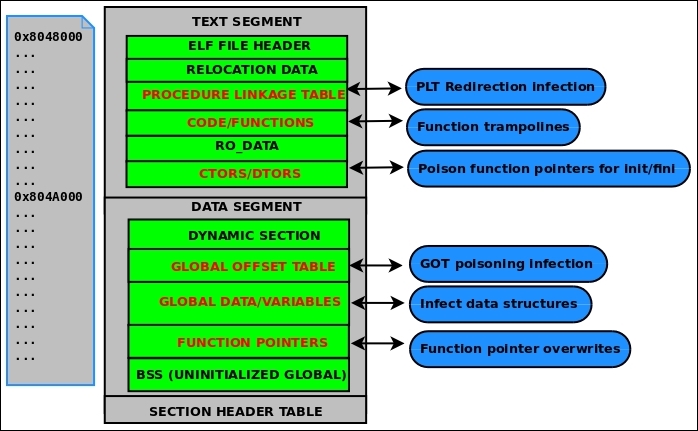

The text segments will be as follows:

[.text]: This is the program code[.rodata]: This is read-only data[.hash]: This is the symbol hash table[.dynsym ]: This is the shared object symbol data[.dynstr ]: This is the shared object symbol name[.plt]: This is the procedure linkage table[.rel.got]: This is the G.O.T relocation dataThe data segments will be as follows:

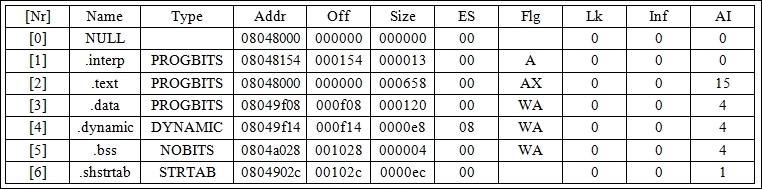

[.data]: These are the globally initialized variables[.dynamic]: These are the dynamic linking structures and objects[.got.plt]: This is the global offset table[.bss]: These are the globally uninitialized variablesLet's take a look at an ET_REL file (object file) section header with the readelf –S command:

ryan@alchemy:~$ gcc -c test.c ryan@alchemy:~$ readelf -S test.o

The following are 12 section headers, starting at offset 0 x 124:

[Nr] Name Type Addr Off

Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[ 0] NULL 00000000 000000

000000 00 0 0 0

[ 1] .text PROGBITS 00000000 000034

000034 00 AX 0 0 4

[ 2] .rel.text REL 00000000 0003d0

000010 08 10 1 4

[ 3] .data PROGBITS 00000000 000068

000000 00 WA 0 0 4

[ 4] .bss NOBITS 00000000 000068

000000 00 WA 0 0 4

[ 5] .comment PROGBITS 00000000 000068

00002b 01 MS 0 0 1

[ 6] .note.GNU-stack PROGBITS 00000000 000093

000000 00 0 0 1

[ 7] .eh_frame PROGBITS 00000000 000094

000038 00 A 0 0 4

[ 8] .rel.eh_frame REL 00000000 0003e0

000008 08 10 7 4

[ 9] .shstrtab STRTAB 00000000 0000cc

000057 00 0 0 1

[10] .symtab SYMTAB 00000000 000304

0000b0 10 11 8 4

[11] .strtab STRTAB 00000000 0003b4

00001a 00 0 0 1No program headers exist in relocatable objects (ELF files of type ET_REL) because .o files are meant to be linked into an executable, but not meant to be loaded directly into memory; therefore, readelf -l will yield no results on test.o. Linux loadable kernel modules are actually ET_REL objects and are an exception to the rule because they do get loaded directly into kernel memory and relocated on the fly.

We can see that many of the sections we talked about are present, but there are also some that are not. If we compile test.o into an executable, we will see that many new sections have been added, including .got.plt, .plt, .dynsym, and other sections that are related to dynamic linking and runtime relocations:

ryan@alchemy:~$ gcc evil.o -o evil ryan@alchemy:~$ readelf -S evil

The following are 30 section headers, starting at offset 0 x 1140:

[Nr] Name Type Addr Off

Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[ 0] NULL 00000000 000000

000000 00 0 0 0

[ 1] .interp PROGBITS 08048154 000154

000013 00 A 0 0 1

[ 2] .note.ABI-tag NOTE 08048168 000168

000020 00 A 0 0 4

[ 3] .note.gnu.build-i NOTE 08048188 000188

000024 00 A 0 0 4

[ 4] .gnu.hash GNU_HASH 080481ac 0001ac

000020 04 A 5 0 4

[ 5] .dynsym DYNSYM 080481cc 0001cc

000060 10 A 6 1 4

[ 6] .dynstr STRTAB 0804822c 00022c

000052 00 A 0 0 1

[ 7] .gnu.version VERSYM 0804827e 00027e

00000c 02 A 5 0 2

[ 8] .gnu.version_r VERNEED 0804828c 00028c

000020 00 A 6 1 4

[ 9] .rel.dyn REL 080482ac 0002ac

000008 08 A 5 0 4

[10] .rel.plt REL 080482b4 0002b4

000020 08 A 5 12 4

[11] .init PROGBITS 080482d4 0002d4

00002e 00 AX 0 0 4

[12] .plt PROGBITS 08048310 000310

000050 04 AX 0 0 16

[13] .text PROGBITS 08048360 000360

00019c 00 AX 0 0 16

[14] .fini PROGBITS 080484fc 0004fc

00001a 00 AX 0 0 4

[15] .rodata PROGBITS 08048518 000518

000008 00 A 0 0 4

[16] .eh_frame_hdr PROGBITS 08048520 000520

000034 00 A 0 0 4

[17] .eh_frame PROGBITS 08048554 000554

0000c4 00 A 0 0 4

[18] .ctors PROGBITS 08049f14 000f14

000008 00 WA 0 0 4

[19] .dtors PROGBITS 08049f1c 000f1c

000008 00 WA 0 0 4

[20] .jcr PROGBITS 08049f24 000f24

000004 00 WA 0 0 4

[21] .dynamic DYNAMIC 08049f28 000f28

0000c8 08 WA 6 0 4

[22] .got PROGBITS 08049ff0 000ff0

000004 04 WA 0 0 4

[23] .got.plt PROGBITS 08049ff4 000ff4

00001c 04 WA 0 0 4

[24] .data PROGBITS 0804a010 001010

000008 00 WA 0 0 4

[25] .bss NOBITS 0804a018 001018

000008 00 WA 0 0 4

[26] .comment PROGBITS 00000000 001018

00002a 01 MS 0 0 1

[27] .shstrtab STRTAB 00000000 001042

0000fc 00 0 0 1

[28] .symtab SYMTAB 00000000 0015f0

000420 10 29 45 4

[29] .strtab STRTAB 00000000 001a10

00020d 00 0 0As observed, a number of sections have been added, most notably the ones related to dynamic linking and constructors. I strongly suggest that the reader follows the exercise of deducing which sections have been changed or added and what purpose the added sections serve. Consult the ELF(5) man pages or the ELF specifications.

Symbols are a symbolic reference to some type of data or code such as a global variable or function. For instance, the printf() function is going to have a symbol entry that points to it in the dynamic symbol table .dynsym. In most shared libraries and dynamically linked executables, there exist two symbol tables. In the readelf -S output shown previously, you can see two sections: .dynsym and .symtab.

The .dynsym contains global symbols that reference symbols from an external source, such as libc functions like printf, whereas the symbols contained in .symtab will contain all of the symbols in .dynsym, as well as the local symbols for the executable, such as global variables, or local functions that you have defined in your code. So .symtab contains all of the symbols, whereas .dynsym contains just the dynamic/global symbols.

So the question is: Why have two symbol tables if .symtab already contains everything that's in .dynsym? If you check out the readelf -S output of an executable, you will see that some sections are marked A (ALLOC) or WA (WRITE/ALLOC) or AX (ALLOC/EXEC). If you look at .dynsym, you will see that it is marked ALLOC, whereas .symtab has no flags.

ALLOC means that the section will be allocated at runtime and loaded into memory, and .symtab is not loaded into memory because it is not necessary for runtime. The .dynsym contains symbols that can only be resolved at runtime, and therefore they are the only symbols needed at runtime by the dynamic linker. So, while the .dynsym symbol table is necessary for the execution of dynamically linked executables, the .symtab symbol table exists only for debugging and linking purposes and is often stripped (removed) from production binaries to save space.

Let's take a look at what an ELF symbol entry looks like for 64-bit ELF files:

typedef struct {

uint32_t st_name;

unsigned char st_info;

unsigned char st_other;

uint16_t st_shndx;

Elf64_Addr st_value;

Uint64_t st_size;

} Elf64_Sym;Symbol entries are contained within the .symtab and .dynsym sections, which is why the sh_entsize (section header entry size) for those sections are equivalent to sizeof(ElfN_Sym).

The st_name contains an offset into the symbol table's string table (located in either .dynstr or .strtab), where the name of the symbol is located, such as printf.

The st_size contains the size of the symbol, such as the size of a global function ptr, which would be 4 bytes on a 32-bit system.

Every symbol table entry is defined in relation to some section. This member holds the relevant section header table index.

The st_info specifies the symbol type and binding attributes. For a complete list of these types and attributes, consult the ELF(5) man page. The symbol types start with STT whereas the symbol bindings start with STB. As an example, a few common ones are as explained in the next sections.

We've got the following symbol types:

STT_NOTYPE: The symbols type is undefinedSTT_FUNC: The symbol is associated with a function or other executable codeSTT_OBJECT: The symbol is associated with a data objectWe've got the following symbol bindings:

STB_LOCAL: Local symbols are not visible outside the object file containing their definition, such as a function declared static.STB_GLOBAL: Global symbols are visible to all object files being combined. One file's definition of a global symbol will satisfy another file's undefined reference to the same symbol.STB_WEAK: Similar to global binding, but with less precedence, meaning that the binding is weak and may be overridden by another symbol (with the same name) that is not marked as STB_WEAK.There are macros for packing and unpacking the binding and type fields:

ELF32_ST_BIND(info) or ELF64_ST_BIND(info) extract a binding from an st_info valueELF32_ST_TYPE(info) or ELF64_ST_TYPE(info) extract a type from an st_info valueELF32_ST_INFO(bind, type) or ELF64_ST_INFO(bind, type) convert a binding and a type into an st_info valueLet's look at the symbol table for the following source code:

static inline void foochu()

{ /* Do nothing */ }

void func1()

{ /* Do nothing */ }

_start()

{

func1();

foochu();

}The following is the command to see the symbol table entries for functions foochu and func1:

ryan@alchemy:~$ readelf -s test | egrep 'foochu|func1'

7: 080480d8 5 FUNC LOCAL DEFAULT 2 foochu

8: 080480dd 5 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 2 func1We can see that the foochu function is a value of 0x80480da, and is a function (STT_FUNC) that has a local symbol binding (STB_LOCAL). If you recall, we talked a little bit about LOCAL bindings, which mean that the symbol cannot be seen outside the object file it is defined it, which is why foochu is local, since we declared it with the static keyword

in our source code.

Symbols make life easier for everyone; they are a part of ELF objects for the purpose of linking, relocation, readable disassembly, and debugging. This brings me to the topic of a useful tool that I coded in 2013, named ftrace. Similar to, and in the same spirit of ltrace and strace, ftrace will trace all of the function calls made within the binary and can also show other branch instructions such as jumps. I originally designed ftrace to help in reversing binaries for which I didn't have the source code while at work. The ftrace is considered to be a dynamic analysis tool. Let's take a look at some of its capabilities. We compile a binary with the following source code:

#include <stdio.h>

int func1(int a, int b, int c)

{

printf("%d %d %d\n", a, b ,c);

}

int main(void)

{

func1(1, 2, 3);

}Now, assuming that we don't have the preceding source code and we want to know the inner workings of the binary that it compiles into, we can run ftrace on it. First let's look at the synopsis:

ftrace [-p <pid>] [-Sstve] <prog>

The usage is as follows:

[-p]: This traces by PID[-t]: This is for the type detection of function args[-s]: This prints string values[-v]: This gives a verbose output[-e]: This gives miscellaneous ELF information (symbols, dependencies)[-S]: This shows function calls with stripped symbols[-C]: This completes the control flow analysisryan@alchemy:~$ ftrace -s test

[+] Function tracing begins here:

PLT_call@0x400420:__libc_start_main()

LOCAL_call@0x4003e0:_init()

(RETURN VALUE) LOCAL_call@0x4003e0: _init() = 0

LOCAL_call@0x40052c:func1(0x1,0x2,0x3) // notice values passed

PLT_call@0x400410:printf("%d %d %d\n") // notice we see string value

1 2 3

(RETURN VALUE) PLT_call@0x400410: printf("%d %d %d\n") = 6

(RETURN VALUE) LOCAL_call@0x40052c: func1(0x1,0x2,0x3) = 6

LOCAL_call@0x400470:deregister_tm_clones()

(RETURN VALUE) LOCAL_call@0x400470: deregister_tm_clones() = 7A clever individual might now be asking: What happens if a binary's symbol table has been stripped? That's right; you can strip a binary of its symbol table; however, a dynamically linked executable will always retain .dynsym but will discard .symtab if it is stripped, so only the imported library symbols will show up.

If a binary is compiled statically (gcc-static) or without libc linking (gcc-nostdlib), and it is then stripped with the strip command, a binary will have no symbol table at all since the dynamic symbol table is no longer imperative. The ftrace behaves differently with the –S flag that tells ftrace to show every function call even if there is no symbol attached to it. When using the –S flag, ftrace will display function names as SUB_<address_of_function>, similar to how IDA pro will show functions that have no symbol table reference.

Let's look at the following very simple source code:

int foo(void) {

}

_start()

{

foo();

__asm__("leave");

}The preceding source code simply calls the foo() function and exits. The reason we are using _start() instead of main() is because we compile it with the following:

gcc -nostdlib test2.c -o test2

The gcc flag -nostdlib directs the linker to omit standard libc linking conventions and to simply compile the code that we have and nothing more. The default entry point is a symbol called _start():

ryan@alchemy:~$ ftrace ./test2 [+] Function tracing begins here: LOCAL_call@0x400144:foo() (RETURN VALUE) LOCAL_call@0x400144: foo() = 0 Now let's strip the symbol table and run ftrace on it again: ryan@alchemy:~$ strip test2 ryan@alchemy:~$ ftrace -S test2 [+] Function tracing begins here: LOCAL_call@0x400144:sub_400144() (RETURN VALUE) LOCAL_call@0x400144: sub_400144() = 0

We now notice that foo() function has been replaced by sub_400144(), which shows that the function call is happening at address 0x400144. Now if we look at the binary test2 before we stripped the symbols, we can see that 0x400144 is indeed where foo() is located:

ryan@alchemy:~$ objdump -d test2 test2: file format elf64-x86-64 Disassembly of section .text: 0000000000400144<foo>: 400144: 55 push %rbp 400145: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp 400148: 5d pop %rbp 400149: c3 retq 000000000040014a <_start>: 40014a: 55 push %rbp 40014b: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp 40014e: e8 f1 ff ff ff callq 400144 <foo> 400153: c9 leaveq 400154: 5d pop %rbp 400155: c3 retq

In fact, to give you a really good idea of how helpful symbols can be to reverse engineers (when we have them), let's take a look at the test2 binary, this time without symbols to demonstrate how it becomes slightly less obvious to read. This is primarily because branch instructions no longer have a symbol name attached to them, so analyzing the control flow becomes more tedious and requires more annotation, which some disassemblers like IDA-pro allow us to do as we go:

$ objdump -d test2 test2: file format elf64-x86-64 Disassembly of section .text: 0000000000400144 <.text>: 400144: 55 push %rbp 400145: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp 400148: 5d pop %rbp 400149: c3 retq 40014a: 55 push %rbp 40014b: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp 40014e: e8 f1 ff ff ff callq 0x400144 400153: c9 leaveq 400154: 5d pop %rbp 400155: c3 retq

The only thing to give us an idea where a new function starts is by examining the

procedure prologue, which is at the beginning of every function, unless (gcc -fomit-frame-pointer) has been used, in which case it becomes less obvious to identify.

This book assumes that the reader already has some knowledge of assembly language, since teaching x86 asm is not the goal of this book, but notice the preceding emboldened procedure prologue, which helps denote the start of each function. The procedure prologue just sets up the stack frame for each new function that has been called by backing up the base pointer on the stack and setting its value to the stack pointers before the stack pointer is adjusted to make room for local variables. This way variables can be referenced as positive offsets from a fixed address stored in the base pointer register ebp/rbp.

Now that we've gotten a grasp on symbols, the next step is to understand relocations. We will see in the next section how symbols, relocations, and sections are all closely tied together and live at the same level of abstraction within the ELF format.

Relocation is the process of connecting symbolic references with symbolic definitions. Relocatable files must have information that describes how to modify their section contents, thus allowing executable and shared object files to hold the right information for a process's program image. Relocation entries are these data.

The process of relocation relies on symbols and sections, which is why we covered symbols and sections first. In relocations, there are relocation records, which essentially contain information about how to patch the code related to a given symbol. Relocations are literally a mechanism for binary patching and even hot-patching in memory when the dynamic linker is involved. The linker program: /bin/ld that is used to create executable files, and shared libraries must have some type of metadata that describes how to patch certain instructions. This metadata is stored as what we call relocation records. I will further explain relocations by using an example.

Imagine having two object files linked together to create an executable. We have obj1.o that contains the code to call a function named foo() that is located in obj2.o. Both obj1.o and obj2.o are analyzed by the linker program and contain relocation records so that they may be linked to create a fully working executable program. Symbolic references will be resolved into symbolic definitions, but what does that even mean? Object files are relocatable code, which means that it is code that is meant to be relocated to a location at a given address within an executable segment. Before the relocation process happens, the code has symbols and code that will not properly function or cannot be properly referenced without first knowing their location in memory. These must be patched after the position of the instruction or symbol within the executable segment is known by the linker.

Let's take a quick look at a 64-bit relocation entry:

typedef struct {

Elf64_Addr r_offset;

Uint64_t r_info;

} Elf64_Rel;And some relocation entries require an addend:

typedef struct {

Elf64_Addr r_offset;

uint64_t r_info;

int64_t r_addend;

} Elf64_Rela;The r_offset points to the location that requires the relocation action. A relocation action describes the details of how to patch the code or data contained at r_offset.

The r_info gives both the symbol table index with respect to which the relocation must be made and the type of relocation to apply.

The r_addend specifies a constant addend used to compute the value stored in the relocatable field.

The relocation records for 32-bit ELF files are the same as for 64-bit, but use 32-bit integers. The following example for are object file code will be compiled as 32-bit so that we can demonstrate

implicit addends, which are not as commonly used in 64-bit. An implicit addend occurs when the relocation records are stored in ElfN_Rel type structures that don't contain an r_addend field and therefore the addend is stored in the relocation target itself. The 64-bit executables tend to use the ElfN_Rela structs that contain an explicit addend. I think it is worth understanding both scenarios, but implicit addends are a little more confusing, so it makes sense to bring light to this area.

Let's take a look at the source code:

_start()

{

foo();

}We see that it calls the foo() function. However, the foo() function is not located directly within that source code file; so, upon compiling, there will be a relocation entry created that is necessary for later satisfying the symbolic reference:

$ objdump -d obj1.o obj1.o: file format elf32-i386 Disassembly of section .text: 00000000 <func>: 0: 55 push %ebp 1: 89 e5 mov %esp,%ebp 3: 83 ec 08 sub $0x8,%esp 6: e8 fc ff ff ff call 7 <func+0x7> b: c9 leave c: c3 ret

As we can see, the call to foo() is highlighted and it contains the value 0xfffffffc, which is the implicit addend. Also notice the call 7. The number 7 is the offset of the relocation target to be patched. So when obj1.o (which calls foo() located in obj2.o) is linked with obj2.o to make an executable, a relocation entry that points at offset 7 is processed by the linker, telling it which location (offset 7) needs to be modified. The linker then patches the 4 bytes at offset 7 so that it will contain the real offset to the foo() function, after foo() has been positioned somewhere within the executable.

$ readelf -r obj1.o Relocation section '.rel.text' at offset 0x394 contains 1 entries: Offset Info Type Sym.Value Sym. Name 00000007 00000902 R_386_PC32 00000000 foo

As we can see, a relocation field at offset 7 is specified by the relocation entry's r_offset field.

R_386_PC32 is the relocation type. To understand all of these types, read the ELF specs. Each relocation type requires a different computation on the relocation target being modified. R_386_PC32 modifies the target with S + A – P.S is the value of the symbol whose index resides in the relocation entry.A is the addend found in the relocation entry.P is the place (section offset or address) of the storage unit being relocated (computed using r_offset).Let's look at the final output of our executable after compiling obj1.o and obj2.o on a 32-bit system:

$ gcc -nostdlib obj1.o obj2.o -o relocated $ objdump -d relocated test: file format elf32-i386 Disassembly of section .text: 080480d8 <func>: 80480d8: 55 push %ebp 80480d9: 89 e5 mov %esp,%ebp 80480db: 83 ec 08 sub $0x8,%esp 80480de: e8 05 00 00 00 call 80480e8 <foo> 80480e3: c9 leave 80480e4: c3 ret 80480e5: 90 nop 80480e6: 90 nop 80480e7: 90 nop 080480e8 <foo>: 80480e8: 55 push %ebp 80480e9: 89 e5 mov %esp,%ebp 80480eb: 5d pop %ebp 80480ec: c3 ret

We can see that the call instruction (the relocation target) at 0x80480de has been modified with the 32-bit offset value of 5, which points foo(). The value 5 is the result of the R386_PC_32 relocation action:

S + A – P: 0x80480e8 + 0xfffffffc – 0x80480df = 5

The 0xfffffffc is the same as –4 if a signed integer, so the calculation can also be seen as:

0x80480e8 + (0x80480df + sizeof(uint32_t))

To calculate an offset into a virtual address, use the following computation:

address_of_call + offset + 5 (Where 5 is the length of the call instruction)

Which in this case is 0x80480de + 5 + 5 = 0x80480e8.

An address may also be computed into an offset with the following computation:

address – address_of_call – 4 (Where 4 is the length of the immediate operand to the call instruction, which is 32bits).

As mentioned previously, the ELF specs cover ELF relocations in depth, and we will be visiting some of the types used in dynamic linking in the next section, such as R386_JMP_SLOT relocation entries.

Relocatable code injection is a technique that hackers, virus writers, or anyone who wants to modify the code in a binary may utilize as a way to relink a binary after it's already been compiled and linked into an executable. That is, you can inject an object file into an executable, update the executable's symbol table to reflect newly inserted functionality, and perform the necessary relocations on the injected object code so that it becomes a part of the executable.

A complicated virus might use this technique rather than just appending position-independent code. This technique requires making room in the target executable to inject the code, followed by applying the relocations. We will cover binary infection and code injection more thoroughly in Chapter 4, ELF Virus Technology – Linux/Unix Viruses.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, The Linux Environment and Its Tools, there is an amazing tool called Eresi (http://www.eresi-project.org), which is capable of relocatable code injection (aka ET_REL injection). I also designed a custom reverse engineering tool for ELF, namely,

Quenya. It is very old but can be found at http://www.bitlackeys.org/projects/quenya_32bit.tgz. Quenya has many features and capabilities, and one of them is to inject object code into an executable. This can be very useful for patching a binary by hijacking a given function. Quenya is only a prototype and was never developed to the extent that the Eresi project was. I am only using it as an example because I am more familiar with it; however, I will say that for more reliable results, it may be desirable to either use Eresi or write your own tooling.

Let us pretend we are an attacker and we want to infect a 32-bit program that calls puts() to print Hello World. Our goal is to hijack puts() so that it calls evil_puts():

#include <sys/syscall.h>

int _write (int fd, void *buf, int count)

{

long ret;

__asm__ __volatile__ ("pushl %%ebx\n\t"

"movl %%esi,%%ebx\n\t"