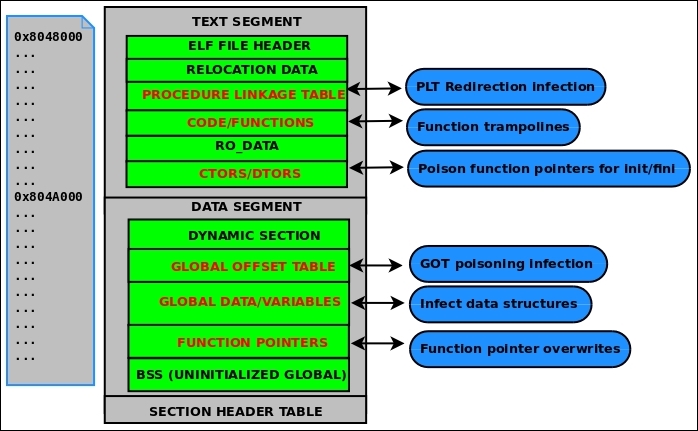

In the previous section, we examined the methods in which parasite code can be introduced into a binary and then executed by modifying the entry point of the infected program. As far as introducing new code into a binary goes, these methods work excellently; in fact, they are great for binary patching, whether it be for legitimate engineering reasons or for a virus. Modifying the entry point is also quite suitable in many cases, but it is far from stealthy, and in some cases, you may not want your parasite code to execute at entry time. Perhaps your parasite code is a single function that you infected a binary with and you only want this function to be called as a replacement for another function within the binary that it infected; this is called function hijacking. When intending to pursue more intricate infection strategies, we must be aware of all of the possible infection points in an ELF program. This is where things begin to get real interesting. Let's take a look at many of the common ELF binary infection points:

Figure 4.6: ELF infection points

As shown in the preceding figure, there are six other primary areas in the ELF program that can be manipulated to modify the behavior in some way.

Do not confuse this with PLT/GOT (sometimes called PLT hooks). The PLT (procedure linkage table) and GOT (global offset table) work closely in conjunction during dynamic linking and through shared library function calls. They are two separate sections, though. We learned about them in the Dynamic linking section of Chapter 2, The ELF Binary Format. As a quick refresher, the PLT contains an entry for every shared library function. Each entry contains code that performs an indirect jmp to a destination address that is stored in the GOT. These addresses eventually point to their associated shared library function once the dynamic linking process has been completed. Usually, it is practical for an attacker to overwrite the GOT entry containing the address that points to his or her code. This is practical because it is easiest; the GOT is writable, and one must only modify its table of addresses to change the control flow. When discussing direct PLT infection, we are not referring to modifying the GOT, though. We are talking about actually modifying the PLT code so that it contains a different instruction to alter the control flow.

The following is the code for a PLT entry for the libc fopen() function:

0000000000402350 <fopen@plt>: 402350: ff 25 9a 7d 21 00 jmpq *0x217d9a(%rip) # 61a0f0 402356: 68 1b 00 00 00 pushq $0x1b 40235b: e9 30 fe ff ff jmpq 402190 <_init+0x28>

Notice that the first instruction is an indirect jump. The instruction is six bytes long: this could easily be replaced with another five/six-byte instruction that changes the control flow to the parasite code. Consider the following instructions:

push $0x000000 ; push the address of parasite code onto stack ret ; return to parasite code

These instructions are encoded as \x68\x00\x00\x00\x00\xc3, which could be injected into the PLT entry to hijack all fopen() calls with a parasite function (whatever that might be). Since the .plt section is in the text segment, it is read-only, so this method won't work as a technique for exploiting vulnerabilities (such as .got overwriting), but it is absolutely possible to implement with a virus or a memory infection.

This type of infection certainly falls into the last category of direct PLT infection, but to be specific with our terminology, let me describe what a traditional function trampoline usually refers to, which is overwriting the first five to seven bytes of a function's code with some type of branch instruction that changes the control flow:

movl $<addr>, %eax --- encoded as \xb8\x00\x00\x00\x00\xff\xe0 jmp *%eax push $<addr> --- encoded as \x68\x00\x00\x00\xc3 ret

The parasite function is then called instead of the intended function. If the parasite function needs to call the original function, which is often the case, then it is the job of the parasite function to replace those five to seven bytes in the original function with the original instructions, call it, and then copy the trampoline code back into place. This method can be used both by applying it in the actual binary itself or in memory. This technique is commonly used when hijacking kernel functions, although it is not very safe in multithreaded environments.

This method was actually mentioned earlier in this chapter when discussing the challenges of directing the control flow of execution to the parasite code. For the sake of completeness, I will give a recap of it: Most executables are compiled by linking to libc, and so gcc includes glibc initialization code in compiled executables and shared libraries. The .ctors and .dtors sections (sometimes called .init_array and .fini_array) contain function pointers to initialization or finalization code. The .ctors/.init_array function pointers are triggered before main() is ever called. This means that one can transfer control to their virus or parasite code by overwriting one of the function pointers with the proper address. The .dtors/.fini_array function pointers are not triggered until after main(), which can be desirable in some cases. For instance, certain heap overflow vulnerabilities (for example, Once upon a free: http://phrack.org/issues/57/9.html) result in allowing the attacker to write four bytes to any location, and often will overwrite a .dtors function pointer with an address that points to shellcode. In the case of most virus or malware authors, the .ctors/.init_array function pointers are more commonly the target, since it is usually desirable to get the parasite code to run before the rest of the program.

Also called PLT/GOT infection, GOT poisoning is probably the best way to hijack shared library functions. It is relatively easy and allows attackers to make good use of the GOT, which is a table of pointers. Since we discussed the GOT in depth in the dynamic linking section in Chapter 2, The ELF Binary Format, I won't elaborate more on its purpose. This technique can be applied by infecting a binary's GOT directly or simply doing it in memory. There is a paper about doing this in memory that I wrote in 2009 called Modern Day ELF Runtime infection via GOT poisoning at http://vxheaven.org/lib/vrn00.html, which explains how to do this in runtime process infection and also provides a technique that can be used to bypass security restrictions imposed by PaX.

The data segment of an executable contains global variables, function pointers, and structures. This opens up an attack vector that is isolated to specific executables, as each program has a different layout in the data segment: different variables, structures, function pointers, and so on. Nonetheless, if an attacker is aware of the layout, one can manipulate them by overwriting function pointers and other data to change the behavior of the executable. One good example of this is with data/.bss buffer overflow exploits. As we learned in Chapter 2, The ELF Binary Format, .bss is allocated at runtime (at the end of the data segment) and contains uninitialized global variables. If someone were able to overflow a buffer that contained a path to an executable that is executed, then one could control which executable would be run.

This technique really falls into the last one (infecting data structures) and also into the one pertaining to .ctors/.dtors function pointer overwrites. For the sake of completeness, I have it listed it as its own technique, but essentially, these pointers are going to be in the data segment and in .bss (initialized/uninitialized static data). As we've already talked about, one can overwrite a function pointer to change the control flow so that it points to the parasite.