First, it is necessary to understand that a software protector is actually made up of two programs:

- Protection phase code: The program that applies the protection to the target binary

- Runtime engine or stub: The program that is merged with the target binary that is responsible for deobfuscation and anti-debugging at runtime

The protector program can vary greatly depending on the types of protection that are being applied to the target binary. Whatever type of protection is being applied to the target binary must be understood by the runtime code. The runtime code (or stub) must know how to decrypt or deobfuscate the binary that it is merged with. In most cases of software protection, there is a relatively simple runtime engine merged with the protected binary; its sole purpose is to decrypt the binary and pass control to the decrypted binary in memory.

This type of runtime engine is not so much an engine—really—and we call it a stub. The stub is generally compiled without any libc linkings (for example, gcc -nostdlib), or is statically compiled. This type of stub, although simpler than a true runtime engine, is actually still quite complicated because it must be able to exec() a program from memory—this is where userland exec comes into play. We can thank the grugq for his contributions here.

The SYS_execve system call, which is generally used by the glibc wrappers (for example, execve, execv, execle, and execl) will load and run an executable file. In the case of a software protector, the executable is encrypted and must be decrypted prior to being executed. Only an unseasoned hacker would program their stub to decrypt the executable and then write it to disk in a decrypted form before they execute it with SYS_exec, although the original UPX packer did work this way.

The skilled way of accomplishing this is by decrypting the executable in place (in memory), and then loading and executing it from the memory—not a file. This can be done from the userland code, and therefore we call this technique userland exec. Many software protectors implement a stub that does this. One of the challenges in implementing a stub userland exec is that it must load the segments into their designated address range, which would typically be the same addresses that are designated for the stub executable itself.

This is only a problem for ET_EXEC-type executables (since they are not position independent), and it is generally overcome by using a custom linker script that tells the stub executable segments to load at an address other than the default. An example of such a linker script is shown in the section on linker scripts in Chapter 1, The Linux Environment and Its Tools.

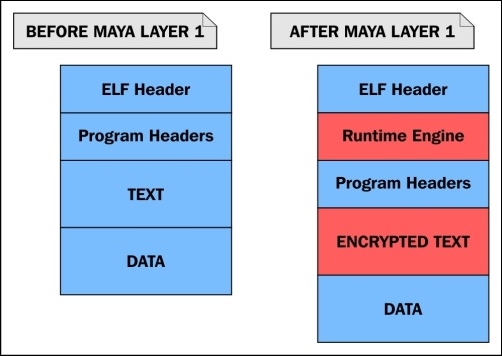

Illustration 5.1: A model of a binary protector stub

Illustration 5.1 shows visually how the encrypted executable is embedded within the data segment of the stub executable, wrapped within it, which is why stubs are also referred to as wrappers.

Note

We will show in Identifying protected binarires section in Chapter 6, ELF Binary Forensics in Linux how peeling a wrapper off can actually be a trivial task in many cases, and how it may also be an automated task with the use of software or scripts.

A typical stub performs the following tasks:

- Decrypting its payload (which is the original executable)

- Mapping the executable's loadable segments into the memory

- Mapping the dynamic linker into the memory

- Creating a stack (that is with mmap)

- Setting the stack up (argv, envp, and the auxiliary vector)

- Passing control to the entry point of the program

A stub of this nature is essentially just a userland exec implementation that loads and executes the program embedded within its own program body, instead of an executable that is a separate file.

Note

The original userland exec research and algorithm can be found in the grugq's paper titled The Design and Implementation of Userland Exec at https://grugq.github.io/docs/ul_exec.txt.

Let's take a look at an executable before and after it is protected by a simple protector that I wrote. Using readelf to view the program headers, we can see that the binary has all the segments that we would expect to see in a dynamically linked Linux executable:

$ readelf -l test

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x400520

There are 9 program headers, starting at offset 64

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr

FileSiz MemSiz Flags Align

PHDR 0x0000000000000040 0x0000000000400040 0x0000000000400040

0x00000000000001f8 0x00000000000001f8 R E 8

INTERP 0x0000000000000238 0x0000000000400238 0x0000000000400238

0x000000000000001c 0x000000000000001c R 1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2]

LOAD 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000400000 0x0000000000400000

0x00000000000008e4 0x00000000000008e4 R E 200000

LOAD 0x0000000000000e10 0x0000000000600e10 0x0000000000600e10

0x0000000000000248 0x0000000000000250 RW 200000

DYNAMIC 0x0000000000000e28 0x0000000000600e28 0x0000000000600e28

0x00000000000001d0 0x00000000000001d0 RW 8

NOTE 0x0000000000000254 0x0000000000400254 0x0000000000400254

0x0000000000000044 0x0000000000000044 R 4

GNU_EH_FRAME 0x0000000000000744 0x0000000000400744 0x0000000000400744

0x000000000000004c 0x000000000000004c R 4

GNU_STACK 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 RW 10

GNU_RELRO 0x0000000000000e10 0x0000000000600e10 0x0000000000600e10

0x00000000000001f0 0x00000000000001f0 R 1Now, let's run our protector program on the binary and view the program headers afterwards:

$ ./elfpack test

$ readelf -l test

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0xa01136

There are 5 program headers, starting at offset 64

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr

FileSiz MemSiz Flags Align

LOAD 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000a00000 0x0000000000a00000

0x0000000000002470 0x0000000000002470 R E 1000

LOAD 0x0000000000003000 0x0000000000c03000 0x0000000000c03000

0x000000000003a23f 0x000000000003b4df RW 1000There are many differences that you will note. The entry point is 0xa01136, and there are only two loadable segments, which are the text and data segments. Both of these are at completely different load addresses than before.

This is of course because the load addresses of the stub cannot conflict with the load address of the encrypted executable contained within it, which must be loaded and memory-mapped to. The original executable has a text segment address of 0x400000. The stub is responsible for decrypting the executable embedded within and then mapping it to the load addresses specified in the PT_LOAD program headers.

If the addresses conflict with the stub's load addresses, then it will not work. This means that the stub program has to be compiled using a custom linker script. The way this is commonly done is by modifying the existing linker script that is used by ld. For the protector used in this example, I modified a line in the linker script:

- This is the original line:

PROVIDE (__executable_start = SEGMENT_START("text-segment", 0x400000)); . = SEGMENT_START("text-segment", 0x400000) + SIZEOF_HEADERS; - The following is the modified line:

PROVIDE (__executable_start = SEGMENT_START("text-segment", 0xa00000)); . = SEGMENT_START("text-segment", 0xa00000) + SIZEOF_HEADERS;

Another thing that you can notice from the program headers in the protected executable is that there is no PT_INTERP segment or PT_DYNAMIC segment. This would appear to the untrained eye as a statically linked executable, since it does not appear to use dynamic linking. This is because you are not viewing the program headers of the original executable.

Note

Remember that the original executable is encrypted and embedded within the stub executable, so you are really viewing the program headers from the stub and not from the executable that it is protecting. In many cases, the stub itself is compiled and linked with very minimal options and does not require dynamic linking itself. One of the primary characteristics of a good userland exec implementation is the ability to load the dynamic linker into memory.

As I mentioned, the stub is a userland exec, and it will map the dynamic linker to the memory after it decrypts and maps the embedded executable to the memory. The dynamic linker will then handle symbol resolution and runtime relocations before it passes control to the now-decrypted program.