Over the years, there have been a few noteworthy binary protectors that were released both publicly and from the underground scene. I will discuss some of the protectors for Linux and give a synopsis of the various features.

DacryFile is the earliest binary protector that I am aware of for Linux (https://github.com/packz/binary-encryption/tree/master/binary-encryption/dacryfile). This protector is simple but nonetheless clever and works very similarly to ELF parasite infection from a virus. In many protectors, the stub wraps around the encrypted binary, but in the case of DacryFile, the stub is just a simple decryption routine that is injected into the binary that is to be protected.

DacryFile encrypts a binary from the beginning of the .text section to the end of the text segment using RC4 encryption. The decryption stub is a simple program written in asm and C, and it does not have the userland exec functionality; it simply decrypts the encrypted body of code. This stub is inserted at the end of the data segment, which is very reminiscent of how a virus inserts a parasite. The entry point of the executable is modified to point to the stub, and upon execution of the binary, the stub decrypts the text segment of the program. Then it passes the control to the original entry point.

Burneye is said by many to have been the first example of decent binary encryption in Linux. By today's standards, it would be considered weak, but it nevertheless brought some innovative features to the table. This includes three layers of encryption, the third of which is a password-protected layer.

The password is converted into a type of hash-sum and then used to decrypt the outermost layer. This means that unless the binary is given the correct password, it will never decrypt. Another layer, called a fingerprint layer, can be used instead of the password layer. This feature creates a key out of an algorithm that fingerprints the system that the binary was protected on, and prevents the binary from being decrypted on any other system but the one it was protected on.

There was also a self-destruct feature; it deletes the binary after it is run once. One of the primary things that separated Burneye from other protectors was that it was the first to use the userland exec technique to wrap binaries. Technically, this was first done by John Resier for the UPX packer, but UPX is considered more of a binary compressor than a protector. John allegedly passed on the knowledge of userland exec to Scut, as mentioned in the Phrack 58 article written by Scut and Grugq on ELF binary protection at http://phrack.org/issues/58/5.html. This article documents the inner workings of Burneye and is highly recommended for reading.

Note

A tool named objobf, which stands for

object obfuscator, was also designed by Scut. This tool obfuscates an ELF32 ET_REL (object file) so that the code is very difficult to disassemble but is functionally equivalent. With the use of techniques such as opaque branches and misaligned assembly, this can be quite effective in deterring static analysis.

Shiva was probably the best publicly available example of Linux binary protection. The source code was never released—only the protector was—but several presentations were delivered at various conferences, such as Blackhat USA, by the authors. These revealed many of its techniques.

Shiva works for 32-bit ELF executables and provides a complete runtime engine (not just a decryption stub) that assists decryption and anti-debugging features throughout the duration of the process that it is protecting. Shiva provides three layers of encryption, where the innermost layer never fully decrypts the entire executable. It decrypts 1,024-byte blocks at a time and then re-encrypts.

For a sufficiently large program, no more than 1/3rd of the program will be decrypted at any given time. Another powerful feature is the inherent anti-debugging—the Shiva protector uses a technique wherein the runtime engine spawns a thread using clone(), which then traces the parent, while the parent conversely traces the thread. This makes using dynamic analysis based on ptrace impossible, since a single process (or thread) may not have more than a single tracer. Also, since both processes are being traced by each other, no other debugger can attach.

Note

A renowned reverse engineer named Chris Eagle successfully unpacked a Shiva-protected binary using an x86 emulator plugin for IDA and gave a presentation on this feat at Blackhat. This reverse engineering of Shiva was said to have been accomplished within a 3-week period.

- Presentation by the authors:

https://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-usa-03/bh-us-03-mehta/bh-us-03-mehta.pdf

- Presentation by Chris Eagle (who broke Shiva):

http://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-federal-03/bh-federal-03-eagle/bh-fed-03-eagle.pdf

Maya's Veil was designed by me in 2014 and is for ELF64 binaries. To this day, the protector is in a prototype stage and has not been released publicly, but there are some forked versions that have transpired into variations of the Maya project. One of them is https://github.com/elfmaster/, which is a version of Maya that incorporates only anti-exploitation technologies, such as control flow integrity. As the originator and designer of the Maya protector, I am at liberty to elaborate on some of the details of its inner workings, primarily for reasons of sparking interest and creativity in readers who are interested in this type of thing. In addition to being the author of this book, I am also quite approachable as a person, so feel free to contact me if you have more questions about Maya's Veil.

Firstly, this protector was designed as a userland-only solution (which means no assistance from clever kernel modules) while still being able to protect a binary with sufficient anti-tamper qualities and—even more impressively—additional anti-exploitation features. Many of the capabilities that Maya possesses have so far been seen only with compiler plugins, whereas Maya operates directly on the already compiled executable binary.

Maya is extremely complicated, and documenting all of its inner workings would be a complete exegesis on the subject of binary protection, but I will summarize some of its most important qualities. Maya can be used to create a layer 1, layer 2, or layer 3 protected binary. At the first layer, it uses an intelligent runtime engine; this engine is compiled as an object file named runtime.o.

This file is injected using a reverse text-padding extension (Refer to Chapter 4, ELF Virus Technology – Linux/Unix Viruses), combined with relocatable code injection relinking techniques. Essentially, the object file for the runtime engine is linked to the executable that it is protecting. This object file is very important as it contains the code for anti-debugging, anti-exploitation, custom malloc with an encrypted heap, metadata about the binary that it is protecting, and so on. This object file was written in about 90% C and 10% x86 assembly.

Maya has multiple layers of protection and encryption. Each additional layer enhances the level of security by adding more work for an attacker to peel off. The outermost layers are the most useful for preventing static analysis, whereas the innermost layer (layer 1) only decrypts the functions within the present call stack and re-encrypts them when done. The following is a more detailed explanation of each layer.

A layer 1 protected binary consists of every single function of the binary individually encrypted. Every function decrypts and re-encrypts on the fly, as they are called and returned. This works because runtime.o contains an intelligent and autonomous self-debugging capability that allows it to closely monitor the execution of a process and determine when it is being attacked or analyzed.

The runtime engine itself has been obfuscated using code obfuscation techniques, such as those found on Scut's object obfuscator tool. The key storage and metadata for the decrypting and re-encrypting functions are stored in a custom malloc() implementation that uses an encrypted heap spawned by the runtime engine. This makes locating the keys difficult. Layer 1 protection is the first and most complex level of protection due to the fact that it instruments the binary with an intelligent and autonomous self-tracing capability for dynamic decryption, anti-debugging, and anti-exploitation abilities.

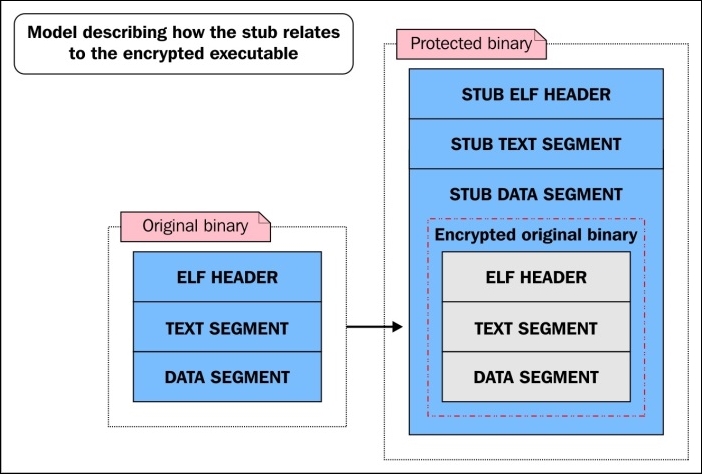

An over-simplified diagram showing how a layer 1 protected binary is laid out next to the original binary

A layer 2 protected binary is the same as a level 1 protected binary, except that not only the functions but also every other section in the binary is encrypted to prevent static analysis. These sections are decrypted at runtime, leaving certain data exposed if someone is able to dump the process, which would have to be done through a memory driver because prctl() is used to protect the process from normal userland dumps through /proc/$pid/mem (and also stops the process from dumping any core files).

Maya's Veil has many other features that make it difficult to reverse-engineer. One such feature is called nanomites. This is where certain instructions in the original binary are completely removed and replaced with junk instructions or breakpoints.

When Maya's runtime engine sees one of these junk instructions or breakpoints, it checks its nanomite records to see what the original instruction was that existed there. The records are stored in the encrypted heap segment of the runtime engine, so accessing this information is non-trivial for a reverse engineer. Once Maya knows what the original instruction did, it emulates the instruction using the ptrace system call.

The anti-exploitation features of Maya are what make it unique compared to other protectors. Whereas most protectors aim only to make reverse engineering difficult, Maya is able to strengthen a binary so that many of its inherent vulnerabilities (such as a buffer overflow) cannot be exploited. Specifically, Maya prevents ROP (short for Return-Oriented Programming) by instrumenting the binary with special control flow integrity technology that is embedded in the runtime engine.

Every function in a protected binary is instrumented with a breakpoint (int3) at the entry point and at every return instruction. The int3 breakpoint delivers a SIGTRAP that triggers the runtime engine; the runtime engine then does one of several things:

- Decrypting the function (only if it hits the entry

int3breakpoint) - Encrypting the function (only if it hits the return

int3breakpoint) - Checking whether the return address has been overwritten

- Checking whether the

int3breakpoint is a nanomite; if so, it will emulate

The third bullet is the anti-ROP feature. The runtime engine checks a hash map that contains valid return addresses for various points within the program. If the return address is invalid, then Maya will bail out and the exploitation attempt will fail.

The following is an example of a vulnerable piece of software code that was specially crafted to test and show off Maya's anti-ROP feature:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

/*

* This shellcode does execve("/bin/sh", …)

/

char shellcode[] = "\xeb\x1d\x5b\x31\xc0\x67\x89\x43\x07\x67\x89\x5b\x08\x67\x89\x43\"

"x0c\x31\xc0\xb0\x0b\x67\x8d\x4b\x08\x67\x8d\x53\x0c\xcd\x80\xe8"

"\xde\xff"\xff\xff\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x2f\x73\x68\x4e\x41\x41\x41\x41"

"\x42\x42";

/*

* This function is vulnerable to a buffer overflow. Our goal is to

* overwrite the return address with 0x41414141 which is the addresses

* that we mmap() and store our shellcode in.

*/

int vuln(char *s)

{

char buf[32];

int i;

for (i = 0; i < strlen(s); i++) {

buf[i] = *s;

s++;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

if (argc < 2)

{

printf("Please supply a string\n");

exit(0);

}

int i;

char *mem = mmap((void *)(0x41414141 & ~4095),

4096,

PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE|PROT_EXEC,

MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS|MAP_FIXED,

-1,

0);

memcpy((char *)(mem + 0x141), (void *)&shellcode, 46);

vuln(argv[1]);

exit(0);

}Let's take a look at how we can exploit vuln.c:

$ gcc -fno-stack-protector vuln.c -o vuln $ sudo chmod u+s vuln $ ./vuln AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA # whoami root #

Now let's protect vuln using the -c option of Maya, which means control flow integrity. Then we will try to exploit the protected binary:

$ ./maya -l2 -cse vuln [MODE] Layer 2: Anti-debugging/anti-code-injection, runtime function level protection, and outter layer of encryption on code/data [MODE] CFLOW ROP protection, and anti-exploitation [+] Extracting information for RO Relocations [+] Generating control flow data [+] Function level decryption layer knowledge information: [+] Applying function level code encryption:simple stream cipher S [+] Applying host executable/data sections: SALSA20 streamcipher (2nd layer protection) [+] Maya's Mind-- injection address: 0x3c9000 [+] Encrypting knowledge: 111892 bytes [+] Extracting information for RO Relocations [+] Successfully protected binary, output file is named vuln.maya $ ./vuln.maya AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA [MAYA CONTROL FLOW] Detected an illegal return to 0x41414141, possible exploitation attempt! Segmentation fault $

This demonstrates that Maya has detected an invalid return address, 0x41414141, before the return instruction actually succeeds. Maya's runtime engine interferes by crashing the program safely (without exploitation).

Another anti-exploitation feature that Maya enforces is relro (read-only relocations). Most modern Linux systems have this feature enabled, but if it is not enabled, Maya will enforce it on its own by creating a read-only page with mprotect() that encompasses the.jcr, .dynamic, .got, .ctors (.init_array), and .dtors (.fini_array) sections. Other anti-exploitation features (such as function pointer integrity) are being planned for the future and have not yet made it into the code base.