Chapter 12. Web Application Architecture

In this chapter, I describe how web applications are engineered and the common technologies they rely upon. Applications today provide a rich user experience through client-side processing and server APIs supporting mobile applications, desktop browsers, and third-party integrations.

System components are increasingly decoupled to foster scalability (e.g., load balancers, application servers, message queuing services, and key-value stores), which introduce risk when third-party services are used. In 2013, for example, MongoHQ suffered a compromise resulting in customer database instances being accessed.1

Web Application Types

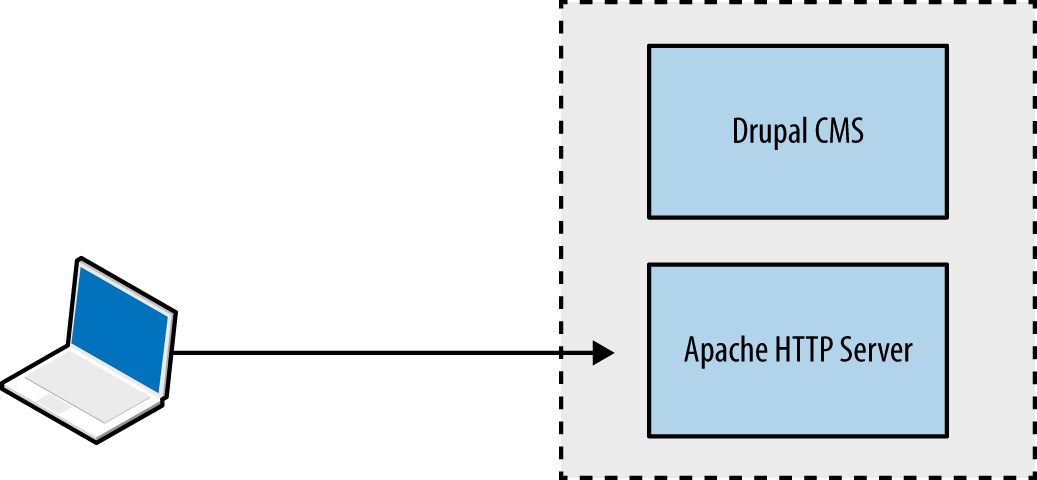

Application categories include retail, banking, gambling, social networking, and information sites (e.g., blogs and news outlets). Consider a standalone web server providing marketing content through a content management system (CMS), as demonstrated by Figure 12-1. Browsers interact with the site over plaintext HTTP, and the application is hosted on a single server.

Figure 12-1. A standalone web application

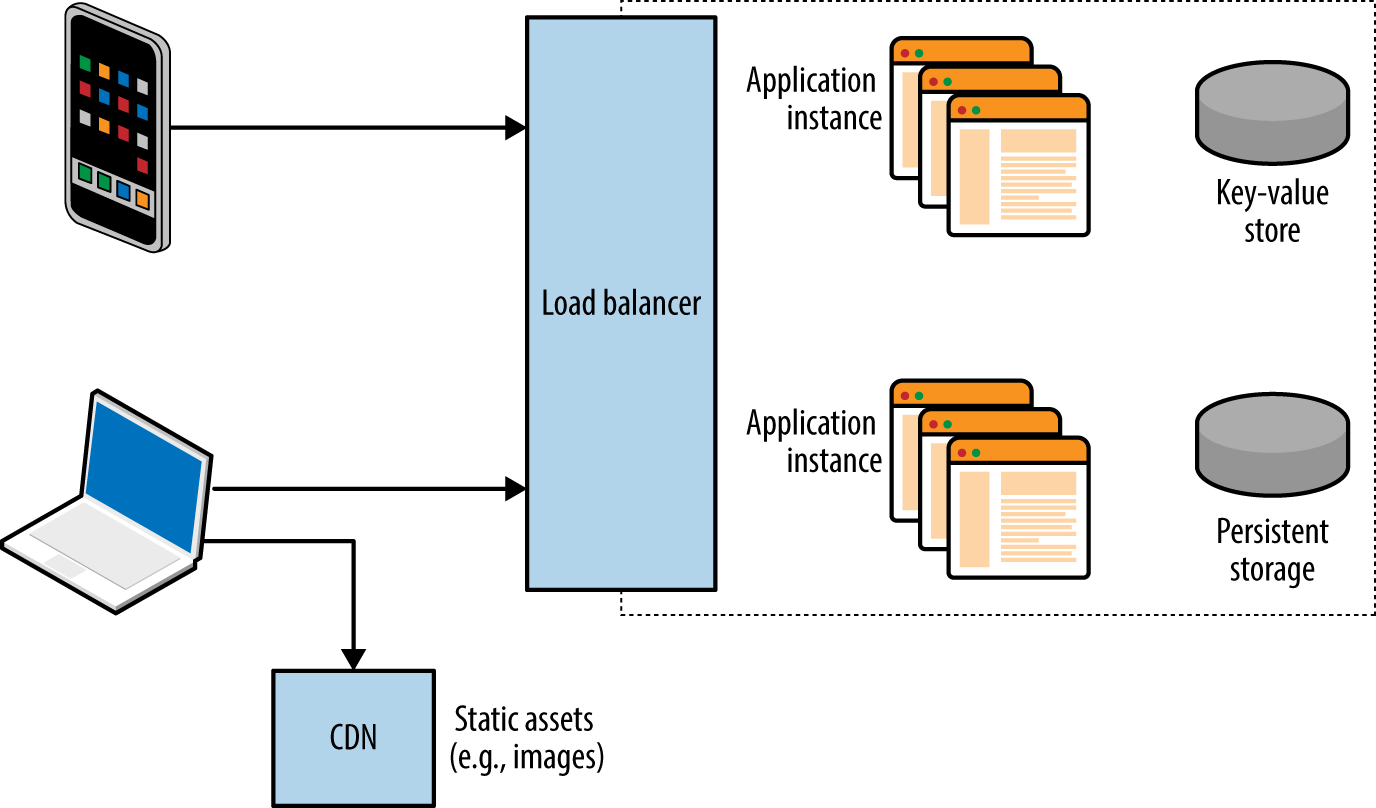

Large web applications (e.g., Facebook, eBay, and banking sites) are complex; utilizing content delivery networks (CDNs) and supporting native mobile applications, as shown in Figure 12-2. Components run across multiple tiers, using various protocols and data formats.

Figure 12-2. A complex web application

Web Application Tiers

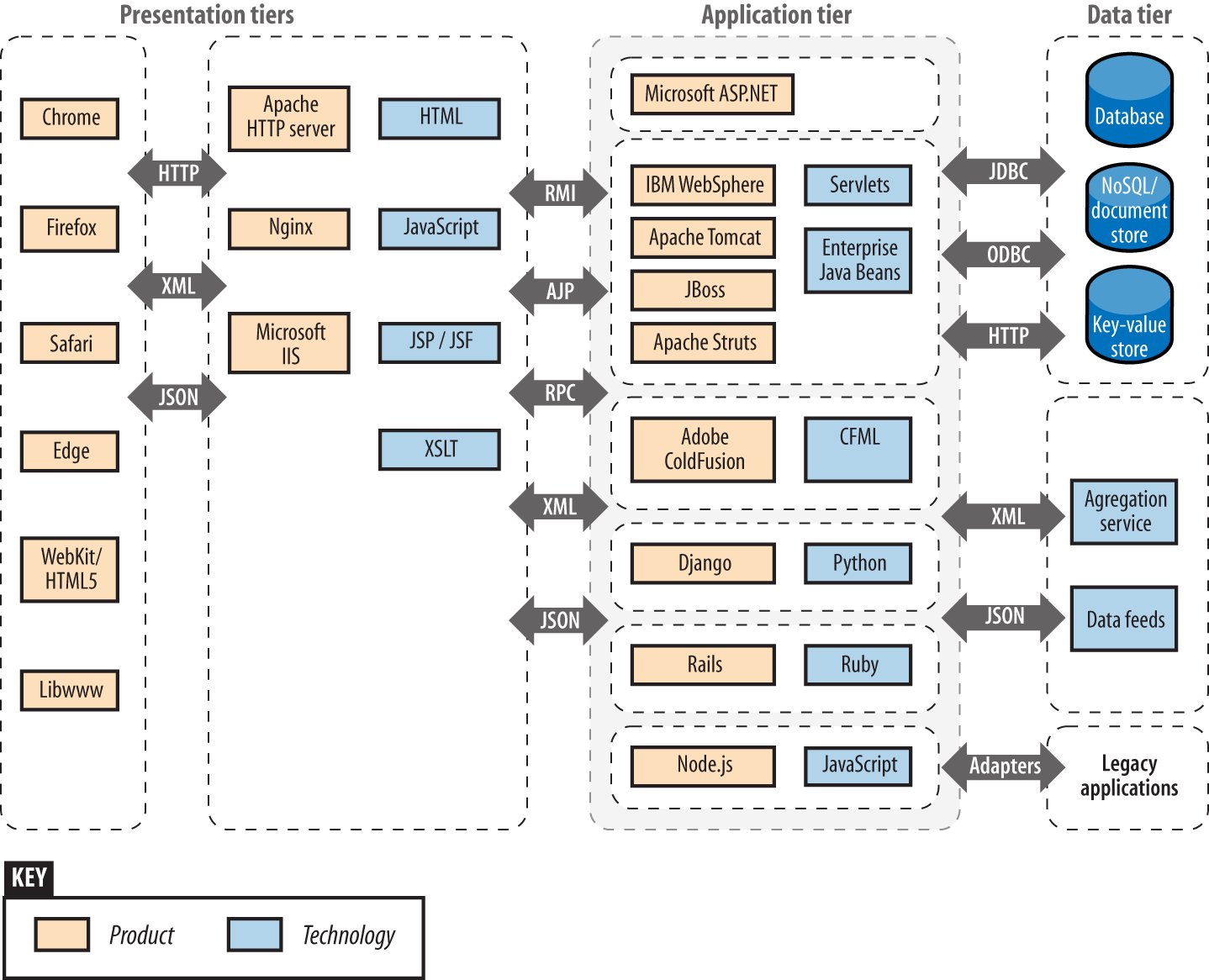

Most applications use components across presentation, application, and data tiers. Figure 12-3 shows tiers and associated browser, server, application framework, and data storage technologies, along with the protocols used to facilitate data exchange.

Figure 12-3. Web application technologies and protocols

Vulnerabilities exist within many of these technologies, and it is important to ensure that minor defects can’t be combined to exploit a system. From a design perspective, the control of data flow between tiers is critical.

The Presentation Tier

Mobile clients and web browsers support rich functionality using JavaScript and client-side technologies that interact with server APIs and endpoints. Processing increasingly occurs on the client system, and HTTP is used to transmit data via standardized formats (e.g., HTML, XML, and JSON).

Here are two protocols used within the presentation tier:

-

TLS, which is used to provide transport layer security via HTTPS

-

HTTP, including features that support streaming and state tracking

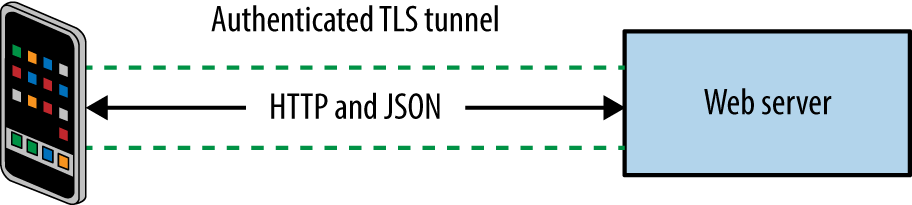

Figure 12-4 demonstrates a native Apple iOS application using TLS to securely interact with a web server and backend application logic. In this example, JSON data is transferred between peers over HTTP.

Figure 12-4. Protocols and data formats used by an iOS application

TLS

Described in Chapter 11, TLS provides the following benefits:

-

Authentication through asymmetric cryptography and use of certificates

-

Confidentiality through symmetric cryptography

-

Integrity through HMAC or use of an authenticated cipher

Security is dependent on client and server configuration (i.e., underlying mathematics is sound, but implementation might be flawed). This was the case when a Apple OS X and iOS defect was identified that permitted MITM attacks to be undertaken.2

HTTP

Servers send data to clients including web browsers, mobile applications, and third parties via HTTP. The protocol is increasingly presented through a secure connection (HTTPS) to mitigate network sniffing risks.

An example HTTP request from a web browser is formatted as follows:

GET / HTTP/1.1 Host: example.org Proxy-Connection: keep-alive Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8 Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1 User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_11_3) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/48.0.2564.97 Safari/537.36 Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, sdch Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.8

The client first provides an HTTP method, target resource, and protocol version. Subsequent lines include HTTP headers and client-supplied data. Methods use differing header and data formats—for example, a GET request is presented in a different format to a POST. Upon receiving a request, the server returns a status code, along with HTTP headers and data to be parsed by the client, for example:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Cache-Control: max-age=604800 Content-Type: text/html Date: Mon, 01 Feb 2016 02:40:08 GMT Etag: "359670651+gzip" Expires: Mon, 08 Feb 2016 02:40:08 GMT Last-Modified: Fri, 09 Aug 2013 23:54:35 GMT Server: ECS (rhv/818F) Vary: Accept-Encoding X-Cache: HIT x-ec-custom-error: 1 Content-Length: 1270

HTTP extensions and features form the building blocks of a web application. In the subsequent sections, I describe the following client and server HTTP features:

-

Client request methods

-

HTTP methods

-

WebDAV extensions

-

Proprietary Microsoft extensions

-

Common request method headers

-

-

Server status codes

-

Additional server features

-

Support for persistent connections and caching

-

HTTP authentication mechanisms

-

Setting cookies

-

Client request methods

Most web servers support HTTP 1.1.3 Table 12-1 lists the client request methods that might be presented upon connecting to a server. Responsiveness and mileage varies depending on the server configuration.

| Method | Notes |

|---|---|

GET |

Used to retrieve server-side content |

POST |

Used to send data to the server within the message body |

HEAD |

Used to check server-side content without retrieving it |

OPTIONS |

Enumerates the supported HTTP methods for a specific URL |

PUT |

Allows file upload if permissions permit the operation |

DELETE |

Performs server-side file deletion, permissions permitting |

TRACE |

Echoes the contents of a request for debugging purposes |

CONNECT |

Provides proxy capabilities to arbitrary hosts and ports |

WebDAV HTTP extensions

WebDAV extensions are used by applications that support publishing and retrieval of data (e.g., Microsoft SharePoint and Microsoft Outlook Anywhere), as described online4 and listed in Table 12-2. Other platforms can be configured to support WebDAV, including the Apache HTTP Server.

| Method | Notes |

|---|---|

SEARCH |

Used to search DAV resources |

PROPFIND |

Used to retrieve properties for a given server-side resource |

PROPPATCH |

Allows a client to modify the properties of a resource |

MKCOL |

Used to create directory structures (known as collections) |

COPY |

Used to copy a resource |

MOVE |

Used to move a resource |

LOCK |

Places a lock on a resource |

UNLOCK |

Removes a lock on a resource |

Note

In addition to common WebDAV methods listed in Table 12-2, others exist around version control (e.g., CHECKIN and CHECKOUT) as used by systems including Apache Subversion and detailed in RFC 3253.

Microsoft HTTP extensions

Microsoft products use proprietary HTTP methods to support functions including Windows Update, as listed in Table 12-3. Microsoft Exchange Server also supports RPC over HTTP, which lets Outlook clients access content via exposed web interfaces.

| Method | Notes |

|---|---|

BITS_POST |

Background Intelligent Transfer Service (BITS) uploada |

CCM_POST |

System Center Configuration Manager (SCCM) registration |

RPC_CONNECT |

RPC over HTTP connection proxy |

RPC_IN_DATA |

RPC over HTTP data transmission |

RPC_OUT_DATA |

RPC over HTTP data request |

a See “BITS Upload Protocol” on the Microsoft Developer Network. | |

Common request method headers

HTTP clients use request header fields to provide credentials and describe the material being transmitted. Table 12-4 lists common fields. IANA maintains an exhaustive list of headers5 used by web and mail protocols.

| Header | Notes |

|---|---|

| Authorization | Client authorization string, used to access protected content |

| Connection | Used to maintain or close an HTTP session |

| Content-Encoding | Indicates content encoding applied to HTTP message body |

| Content-Language | Indicates content language applied to the HTTP message body |

| Content-Length | Indicates the size of the HTTP message body |

| Content-MD5 | MD5 digest of the HTTP message body |

| Content-Range | Indicates the byte range of the HTTP message body |

| Content-Type | Indicates the content type of the HTTP message body |

| Cookie | Sends a cookie value (e.g., session token) with the request |

| Host | Details the virtual host that the HTTP request is destined for |

| Proxy-Authorization | Client authorization string, used to access protected content |

| Range | Desired byte range indicator |

| Referer | Lets the client define the last referring address (URI) |

| Trailer | Indicates HTTP headers are present in the trailer of a chunked HTTP message |

| Transfer-Encoding | Indicates transformation applied to the HTTP message body |

| Upgrade | Specifies HTTP protocols that the client supports so that the server may use a different protocol |

| User-Agent | Indicates the client software in use |

| Warning | Used to carry status or transformation information |

Server status codes

When presented with an HTTP request, a server should respond with a status code and message body containing data to be interpreted by the client. Table 12-5 lists common web server status codes.

| Code | Notes |

|---|---|

| 100 Continue | The server has received the request headers and the client should proceed to send the request body, usually in response to an HTTP PUT or POST request |

| 200 OK | The standard response for successful HTTP requests |

| 201 Created | The request has been fulfilled and a new resource created |

| 301 Moved Permanently | This and all future requests should direct to the given URI |

| 302 Found | A temporary redirect to a given URI |

| 304 Not Modified | Indicates the resource hasn’t been modified since the version specified by the client in the request headers (using If-Modified-Since or If-Match) |

| 400 Bad Request | The request cannot be fulfilled due to bad syntax |

| 401 Unauthorized | Authentication is required or has failed |

| 403 Forbidden | The request is valid, but the server is refusing to honor it |

| 404 Not Found | Common error when a page or resource does not exist |

| 405 Method Not Allowed | The HTTP method used is not permitted for this resource |

| 500 Internal Server Error | A generic error message |

| 501 Not Implemented | The server does not recognize the request method |

| 502 Bad Gateway | The server is acting as a proxy and received an invalid response from the upstream server |

| 503 Service Unavailable | The server is currently unavailable due to high load or maintenance |

| 504 Gateway Timeout | The server is acting as a proxy and did not receive a timely response from the upstream server |

Support for persistent connections and caching

Applications that stream content use persistent HTTP connections and particular data encoding. Most web servers and browsers support the following HTTP 1.1 features:

-

Keep-alive

-

Chunked encoding

-

Caching

Keep-alive functionality lets clients issue multiple requests within a single session. The Content-Length header defines how much data is sent with each request.

Chunked encoding supports streaming and other use cases in which material is dynamically presented (either to or from a client). This is achieved through the Transfer-Encoding: chunked header in conjunction with a keep-alive session.

Browsers and proxies cache content based on directives set by the Cache-Control header.6 Material is marked by using flags, including public, private, no-cache, and no-store. The max-age qualifier is used to define the amount of time that an old copy of the data should be kept.

HTTP authentication mechanisms

Tracking state is critical to many applications (e.g., knowing the difference between an unauthenticated user and one that is logged-in, or a customer who has paid for goods and one who hasn’t), but HTTP is a stateless protocol. As such, applications track state through the following:

-

Setting cookies

-

Placing tokens within HTML that are presented when actions are performed

-

Processing the HTTP referrer header (showing the last page the user visited)

In Chapter 7, I described Kerberos authentication, whereby a ticket is provided to a user upon successful authentication. This ticket has a given validity period and is subsequently presented with each request. Web applications behave in a similar fashion—authenticated users are provided with a session token (set as a cookie), which is presented with each HTTP request.

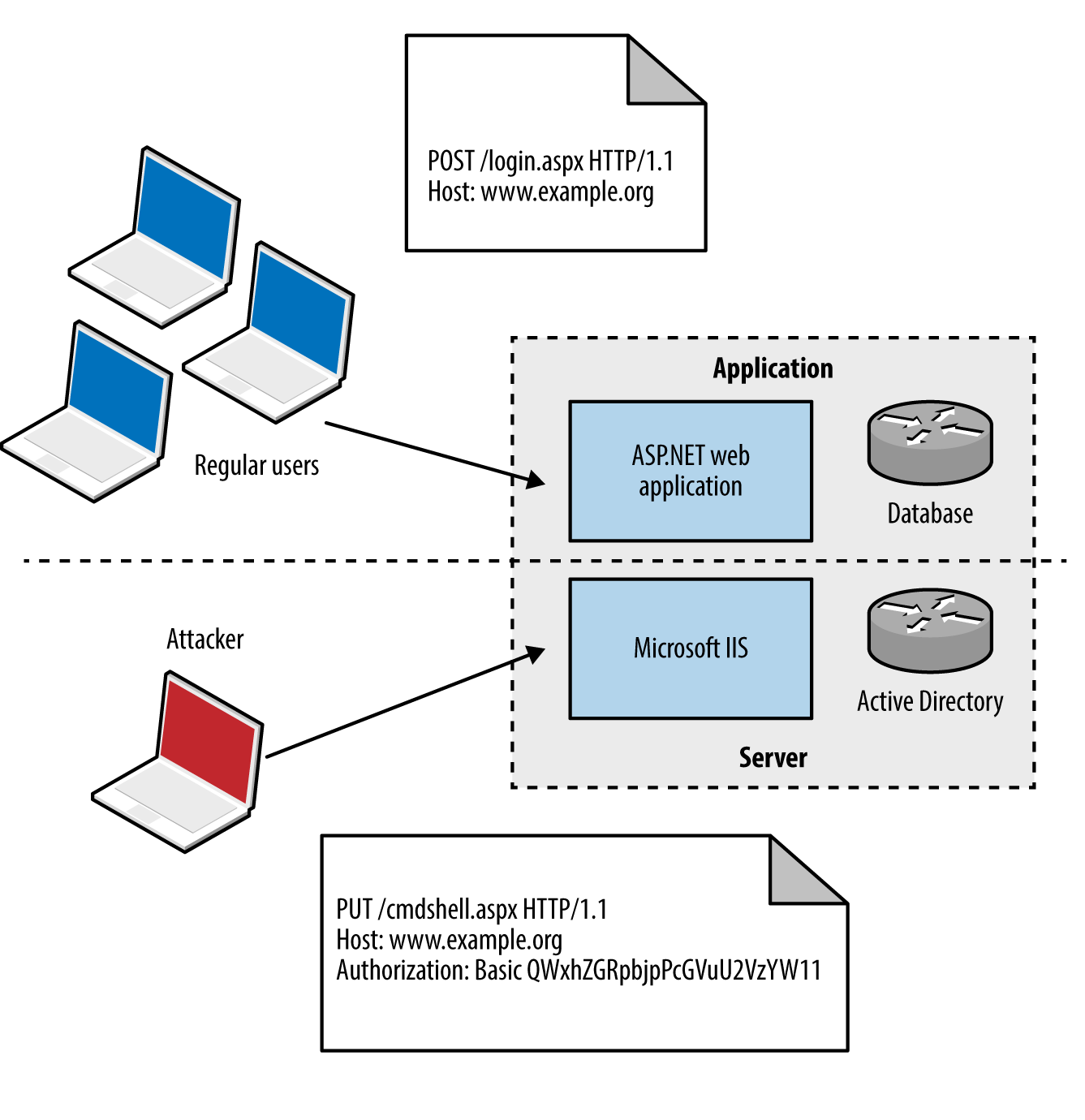

Web servers including Microsoft IIS often support HTTP authentication regardless of the application running atop them. An adversary can use the Authorization request header to uploaded malicious content via supported methods (e.g., WebDAV or HTTP PUT functionality). Figure 12-5 summarizes the scenario.

Figure 12-5. Server versus application authentication

Authentication mechanisms supported by most web servers are Basic and Digest.7 The Basic mechanism is weak: user credentials are base64-encoded and sent in plaintext, which are easily compromised via network sniffing. The Digest mechanism was proposed to overcome this, utilizing MD5 and a shared secret to avoid sending plaintext credentials; however, it is susceptible to a replay attack.

Microsoft web servers support additional authentication types:

The NTLM mechanism uses a base64-encoded challenge-response to authenticate users. Negotiate can proxy either NTLM or Kerberos credentials between the client and Security Support Provider (SSP).

Setting cookies

Used to track users and store materials on the client side, cookies can be by infrastructure hardware (such as load balancers), web application frameworks (e.g., Microsoft ASP.NET), and web applications. Cookies are sent to the client through the Set-Cookie server header, as shown in Example 12-1.

Cookies consist of name-value pairs and attributes. Each attribute defines how the browser should handle the cookie, as listed in Table 12-6. Cookies lacking security attributes can be obtained via XSS or sniffing plaintext HTTP traffic, for example.

| Name | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Domain | Defines the domain scope of the cookie |

| Path | Defines the URL path scope within the domain |

| Expires | Instructs the browser to delete the cookie at a given time |

| Max-Age | Instructs the browser to delete the cookie at a given time |

| Secure | This flag instructs the browser to only transmit the cookie over an HTTPS connection |

| HttpOnly | This flag instructs the browser to transmit the cookie over HTTP(S) and not other means (e.g., JavaScript) |

The client subsequently presents name-value pairs with each request using the Cookie header, as shown in Example 12-2.

CDNs

CDNs are used to reduce latency within web applications by serving static assets (e.g., images, downloadable files, and streamed content) from systems that are “closer” to the client.

Operators maintain points of presence (POPs) around the globe. When a user makes a request to a CDN hostname, DNS and BGP are used to route the request to a server IP, based on location, availability, cost, and other metrics.

Problems arise, however, when CDNs are used to serve sensitive or private content, such as photographs of Facebook and Instagram users. If an attacker knows a valid URL to an image, he can present it without authentication to the CDN and obtain the material. An unpredictable identifier like the one that follows is the only thing protecting content from prying eyes:

If the identifier used is predictable, attackers can obtain content inexpensively. A sufficiently random value should be used to protect sensitive data presented without authentication through a CDN.

Load Balancers

Load balancing systems are used to distribute inbound sessions across many application servers in physical, virtual, and cloud environments, as previously demonstrated by Figure 12-2.

Product vendors, including F5 Networks, produce bare-metal and virtual systems, and cloud providers including Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, provide load balancing within their Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) platforms. As demonstrated, TLS is usually terminated at the load balancer, and plaintext HTTP used internally within an environment.

Presentation-Tier Data Formats

The HTTP Content-Type header is used to describe the format of data being transferred. In particular, a type, subtype, and optional parameters (e.g., language or character set) are defined. Common media types include markup and object notation languages (HTML, XML, and JSON), image formats (JPEG, GIF, and PNG), and JavaScript. IANA maintains a list of registered media types, which include the following:10

application/javascript application/json application/xml image/gif image/jpeg image/png text/html

The Content-Encoding header is often used to describe compression of data. Clients use encoding and media type headers to process data (e.g., executing JavaScript, or decompressing and rendering a web page and its images). Type confusion flaws can be exploited to perform persistent XSS, as demonstrated by Jack Whitton against Facebook, by which malicious JavaScript was placed into a PNG image and retrieved as HTML.11

The Application Tier

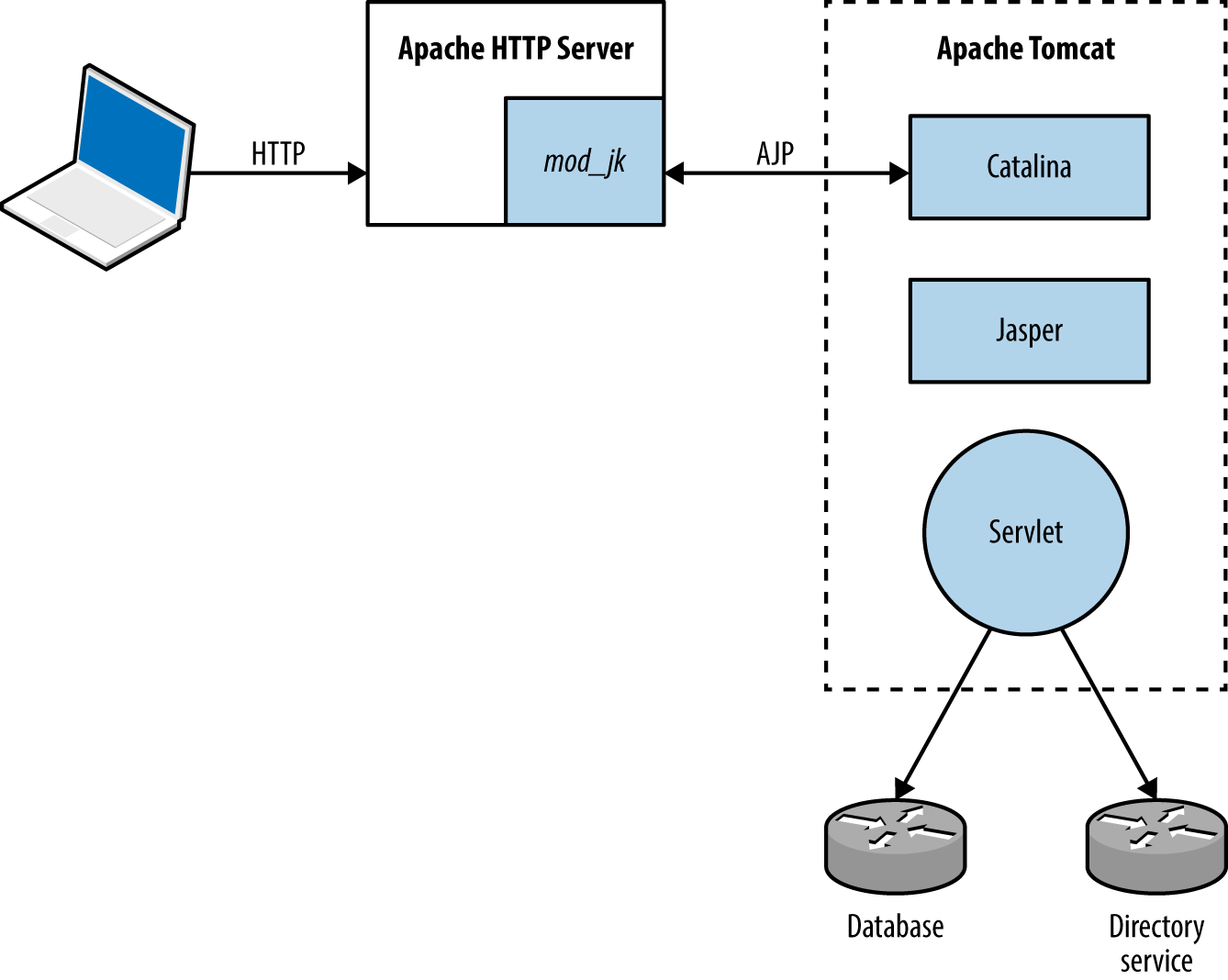

Application servers support the execution of code written in languages including Microsoft ASP.NET, Java, Python, and Ruby. Connectors and adaptors are used to broker communication between clients and applications (e.g., the mod_jk connector used within Apache HTTP Server, as demonstrated by Figure 12-6).

Protocols used by Java application server components include JMX, RMI, and AJP. Microsoft applications tend to use RPC, HTTP, and COM mechanisms for communication. External dependencies might also include LDAP to support external authentication providers (e.g., Microsoft Active Directory).

Figure 12-6. The Apache mod_jk connector in-use

Application-Tier Data Formats

Media types used within the application tier are similar to those used in the presentation tier, including JSON and XML. SAML and other formats support single sign-on and other features.

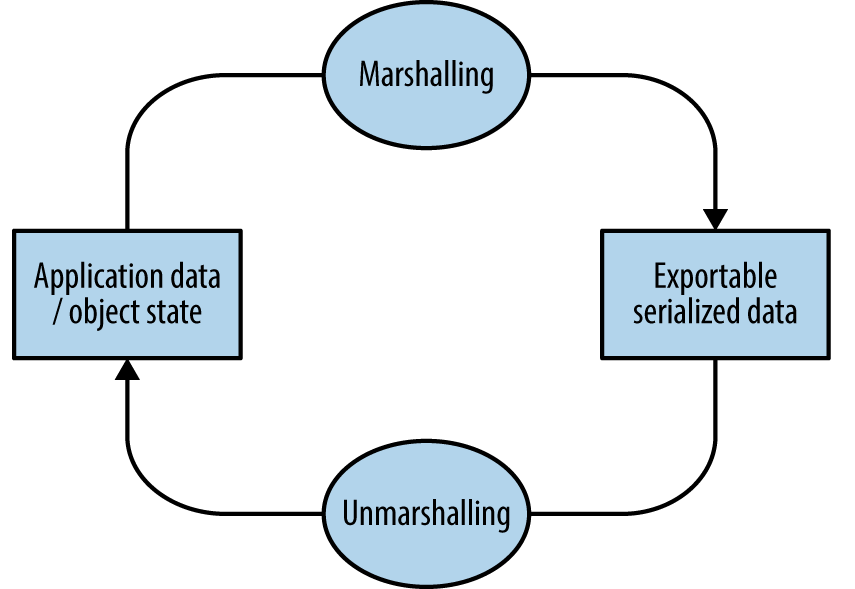

Application components often serialize material before transmission. Serialization (known as marshalling) is the process of translating data structures or object state into a format that can be stored and later reconstructed in the same or another environment (known as unmarshalling). Figure 12-7 demonstrates the process.

Web application frameworks including Rails12 and Django13 have known serialization weaknesses, by which malicious content sent to the application server can lead to exploitation upon unmarshalling and processing (resulting in code execution, information leak, and other issues). Gabriel Lawrence and Chris Frohoff’s AppSecCali presentation details practical exploitation of these flaws.14

Figure 12-7. Marshalling and unmarshalling an object

The Data Tier

Data stores used within web applications include databases, key-value stores, and distributed file systems. Connectors are used to interface with data tier components in the same way as they are between presentation and application tiers, including the following:

-

ODBC and JDBC drivers for MySQL, PostgreSQL, Microsoft SQL Server, etc.

-

Proprietary protocols used by MongoDB, Memcached, Redis, and so on.

-

REST APIs over HTTP (as used by Amazon S3, WebHDFS, and others)

Services might also run over UDP to reduce overhead and improve throughput (e.g., Memcached and NFS). Authentication mechanisms vary (e.g., Redis does not offer authentication by default and Apache Hadoop uses Kerberos), and data formats can range from human-readable documents to machine-readable XML, JSON, and binary material.

1 Dara Kerr, “MongoHQ Scrambles to Address Major Database Hack”, CNET, October 29, 2013.

2 Adam Langley, “Apple’s SSL/TLS Bug”, Imperial Violet Blog, February 22, 2014.

4 See RFCs 2518, 4918, and 5323.

5 See “Message Headers” at IANA.org.

8 Ronald Tschalär, “NTLM Authentication Scheme for HTTP”, Innovation Blog, June 17, 2003.

10 See “Media Types” at IANA.org.

11 Jack Whitton, “An XSS on Facebook via PNGs & Wonky Content Types”, Whitton.io Blog, January 27, 2016.

12 HD Moore, “Serialization Mischief in Ruby Land (CVE-2013-0156)”, Rapid7 Blog, January 9, 2013.

13 See CVE-2013-1665.

14 Christopher Frohoff, “Marshalling Pickles”, SlideShare.net, January 28, 2015.