Chapter 3. Vulnerabilities and Adversaries

Any time you try a decent crime, there are 50 ways to screw up.

If you think of 25 of them, you’re a genius. And you’re no genius.Mickey Rourke

Body Heat (1981)

Software engineers build increasingly elaborate systems without considering even half of the ways to screw up. Thanks to cloud computing and increasing layers of abstraction, unsafe products will persist, and the computer security business will remain a lucrative one for years to come.

The Fundamental Hacking Concept

Hacking is the art of manipulating a system to perform a useful action.

A basic example is that of the humble search engine, which cross-references user input with a database and returns the results. Processing occurs server-side, and by understanding the way in which these systems are engineered, an adversary can seek to manipulate the application and obtain sensitive content.

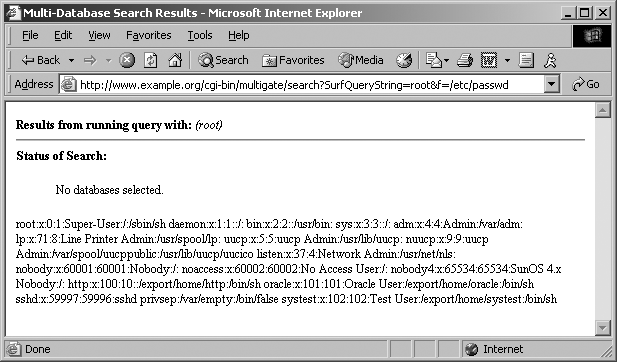

Decades ago, the websites of the US Pentagon, Air Force, and Navy had this very problem. A search engine called multigate accepted two arguments in particular: SurfQueryString and f. The contents of the server’s /etc/passwd file were revealed via a crafted URL, as shown in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1. Exploiting the multigate search engine

These sites were defended at the network layer by firewalls and security appliances. However, by the very nature of the massive amount of information stored, a search engine was implemented, which introduced vulnerability within the application layer.

Note

A useful way to consider the exploitation process is to think of a system being programmed by an adversary to perform a useful action. The individual programming tactics adopted are dependent on system components, features, and the attacker’s goals—such as data exposure, elevation of privilege, arbitrary code execution, or denial of service.

Why Software Is Vulnerable

For more than 30 years, adversaries have exploited vulnerabilities in software, and vendors have worked to enhance the security of their products. Flaws will likely always exist in these increasingly elaborate systems thanks to insufficient quality assurance in particular.

Software vendors find themselves in a situation where, as their products become more complex, it is costly to make them safe. Static code review and dynamic testing of software is a significant undertaking that affects the bottom line and impacts go-to-market time.

Considering Attack Surface

In each successful attack against a computer system, an adversary took advantage of the available attack surface to achieve her goals. This surface often encompasses server applications, client endpoints, users, communication channels, and infrastructure. Each exposed component is fair game.

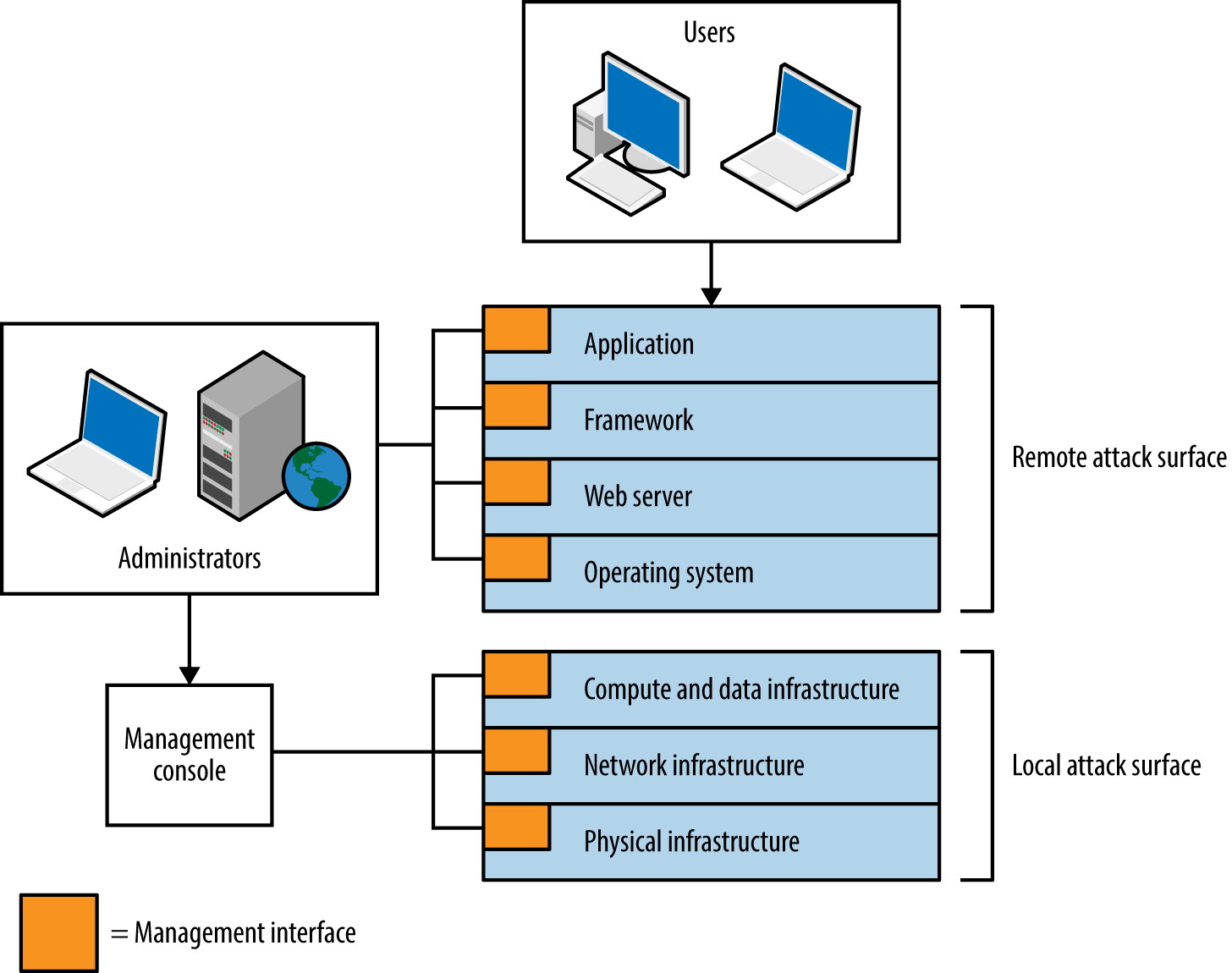

Figure 3-2 depicts a cloud-based web application.

Figure 3-2. Attack surface of a cloud application

The practical means by which the environment could be compromised include the following:

-

Compromise of the hosting provider or cloud management console1

-

Vulnerability within infrastructure (e.g., hypervisor side channel attack2)

-

Operating system vulnerability (e.g., network driver or kernel flaw)

-

Server software flaw (e.g., Nginx or OpenSSL bug)

-

Web application framework flaw (e.g., session management defect)

-

Web application bug (e.g., command injection or business logic flaw)

-

Attack of user HTTPS or SSH sessions

-

Compromise of legitimate credentials (e.g., SSH key or authentication token)

-

Desktop software attack (e.g., PuTTY SSH client or browser exploitation)

-

User attack through social engineering or clickjacking

Some attacks might be undertaken remotely, whereas others require proximity to manipulate vulnerable system components. For example, within multitenant cloud environments, gaining access to internal address space often exposes management interfaces that aren’t publicly accessible.

A Taxonomy of Software Security Errors

Figure 3-2 demonstrates individual software components forming a large attack surface. Locally within each piece of software, security errors might exist that can be exploited for gain. Gary McGraw, Katrina Tsipenyuk, and Brian Chess published a taxonomy3 used to categorize software defects, listing seven kingdoms:

- Input validation and representation

- Failure to validate input or encode data correctly, resulting in the processing of malicious content. Examples of phyla beneath this kingdom include buffer overflows, XSS, command injection, and XXE processing.

- API abuse

- Attackers use functions exposed by system libraries and accessible APIs to execute arbitrary code, read sensitive material, or bypass security controls.

- Security features

- The design and low-level implementation of security features within software should be sound. Failure to perform safe random number generation, enforce least privilege, or securely store sensitive data will often result in compromise.

- Time and state

- Within applications, time and state vulnerabilities are exploited through race conditions, the existence of insecure temporary files, or session fixation (e.g., not presenting a new session token upon login or a state change).

- Errors

- Upon finding an error condition, an adversary attacks error-handling code to influence logical program flow or reveal sensitive material.

- Code quality

- Poor code quality leads to unpredictable behavior within an application. Within low-level languages (e.g., C/C++) such behavior can be catastrophic and result in execution of arbitrary instructions.

- Encapsulation

- Ambiguity within the way an application provides access to both data and code execution paths can result in encapsulation flaws. Examples include data leak between users, and leftover debug code that an attacker can use.

An eighth kingdom is environment—used to classify vulnerabilities found outside of software source code (e.g., flaws within interpreter or compiler software, the web application framework, or underlying infrastructure).

Note

Use the taxonomy to define the source of a defect that leads to unexpected behavior by an application. Note: these kingdoms do not define attack classes (such as side channel attacks).

Threat Modeling

Attackers target and exploit weakness within system components and features. The taxonomy lets us describe and categorize low-level flaws within each software package but does not tackle larger issues within the environment (such as the integrity of data in-transit, or how cryptographic keys are handled). To understand the practical risks to a system, you might model threats by considering the following:

-

Individual system components

-

Goals of the attacker

-

Exposed system components (the available attack surface)

-

Economic cost and feasibility of each attack vector

System Components

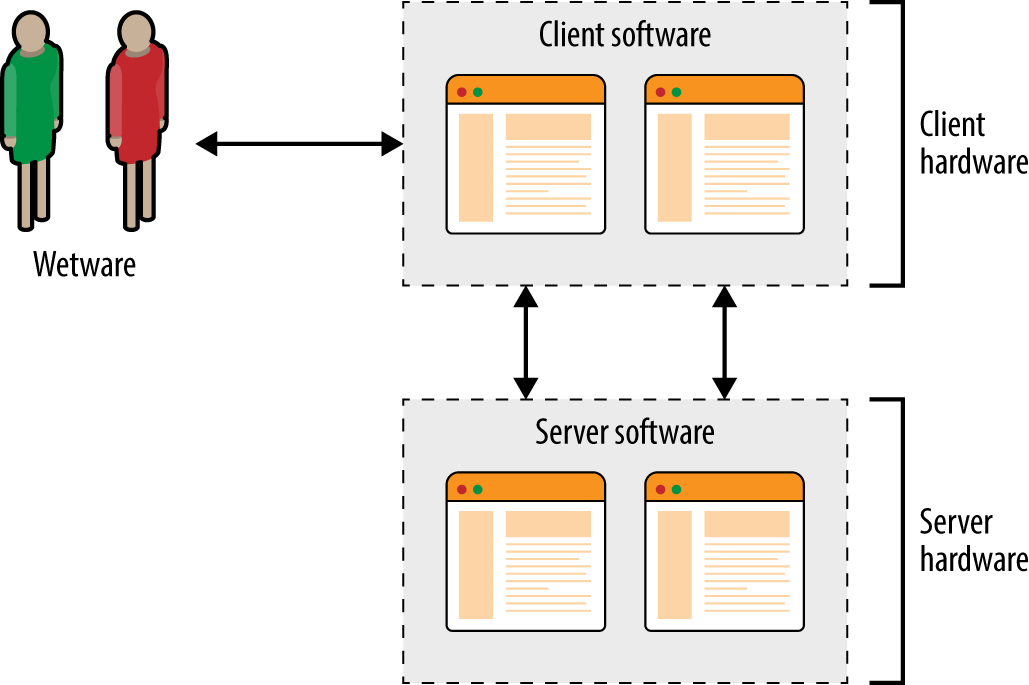

Exploitable vulnerabilities can exist within infrastructure (e.g., hypervisors, software switches, storage nodes, and load balancers), operating systems, server software, client applications, and end users themselves. Figure 3-3 shows the relationship between hardware, software, and wetware components within a typical environment.

Figure 3-3. Individual system components within a physical environment

Adversarial Goals

Attackers pursue goals that might include the following:

- Data exposure or modification

- Within a computer system, data can take many forms, from server-side databases to data in-transit and material processed by client software. Attackers often seek to expose sensitive data, or modify it for gain (e.g., obtaining authentication tokens that can be used to elevate privilege, or modifying flags within memory to disable security features).

- Elevation of privilege

- Software security features enforce boundaries and privilege levels. Attackers can elevate their privileges by either providing legitimate credentials (such as a stolen authentication token) or exploiting flaws within the controls themselves.

- Arbitrary code execution

- Execution of arbitrary instructions within an environment makes it possible for an attacker to directly access resources, and often modify the underlying system configuration.

- Denial of service

- Achieving a condition by which system components become unresponsive (or latency increases beyond a given threshold) can incur cost on the part of the victim, and benefit the attacker.

Software written in languages with memory safety problems (e.g., C/C++) is susceptible to manipulation through buffer overflows, over-reads, and abuse of pointers, which can result in many of these goals being achieved. Writing applications in memory-safe languages (including Java and Microsoft .NET) can render entire bug classes redundant.

System Access and Execution Context

Three broad levels of system access that an adversary can secure are as follows:

- Remote

- Most threats are external to a given system, with access granted via a wide area network such as the Internet. As such, remote attackers are unable to intercept network traffic between components (e.g., the client, server, and system services supporting authentication, content delivery, and other functions) or observe local system operation to uncover secrets via side channels.

- Close proximity

- Logical proximity or network access (e.g., sitting in the same coffee shop as a legitimate user, or securing access to shared cloud infrastructure) often provides access to data flowing between system components, or shared resources (such as server memory or persistent storage). Compromise can occur if material is not adequately protected through transport layer security, or if sensitive data is leaked.

- Direct physical access

- Direct unsupervised access to system components often results in complete compromise. In recent years, government agents have been known to interdict shipments of infrastructure hardware4 (e.g., routers, switches, and firewalls) to implant sophisticated bugs within target environments. Data centers have also been physically compromised.5

Warning

Server applications are becoming increasingly decoupled, with message queuing, content delivery, storage, authentication, and other functions running over IP networks. Data in-transit is targeted for gain, by both local attackers performing network sniffing, and broad surveillance programs.6 Transport security between system components is increasingly important.

A common goal is code execution, by which exposed logic is used to execute particular instructions on behalf of the attacker. Execution often occurs within a narrow context, however. Consider three scenarios:

- XSS

- An adversary feeds malicious JavaScript to a web application, which in turn is presented to an unwitting user and executed within his browser to perform a useful action (such as leaking cookie material or generating arbitrary HTTP requests).

- HTML injection

- Browsers are often exploited through MITM attacks, whereby malicious HTML is presented, leading to memory corruption and limited code execution within a sandboxed browser process.

- Malicious PHP file creation

- Many PHP interpreter flaws are exploited by using malicious content—arbitrary code execution is achieved through crafting a script server-side (via upload or file creation bug), and parsing it to exploit a known bug.

The context under which an adversary executes code varies. For example, web application flaws often result in execution via an interpreted language (e.g., JavaScript, Python, Ruby, or PHP) and rarely provide privileged access to the underlying operating system. Sandbox escape and local privilege escalation tactics must be adopted to achieve persistence.

Attacker Economics

The value of a compromised target to an adversary varies and can run into billions of dollars when dealing in intellectual property, trade secrets, or information that provides an unfair advantage within financial markets. If the value of the data within your systems is significantly greater than the cost to an adversary to obtain it, you are likely a target.

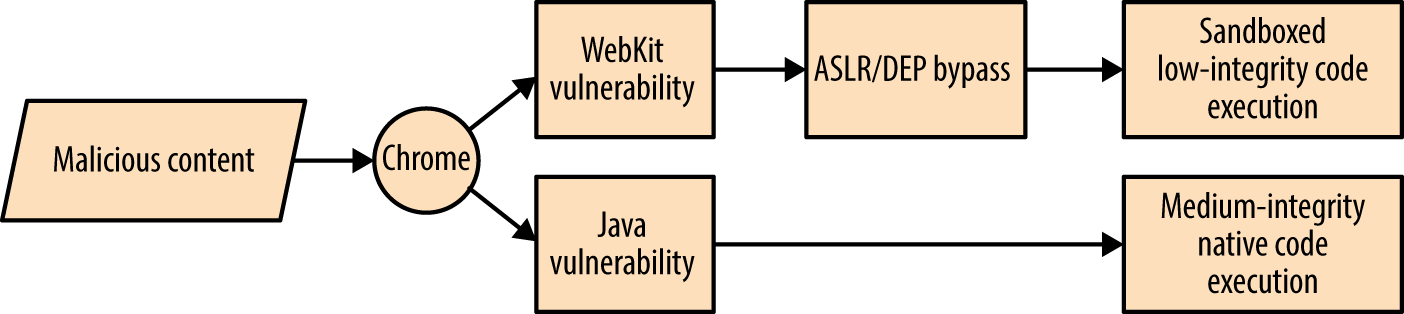

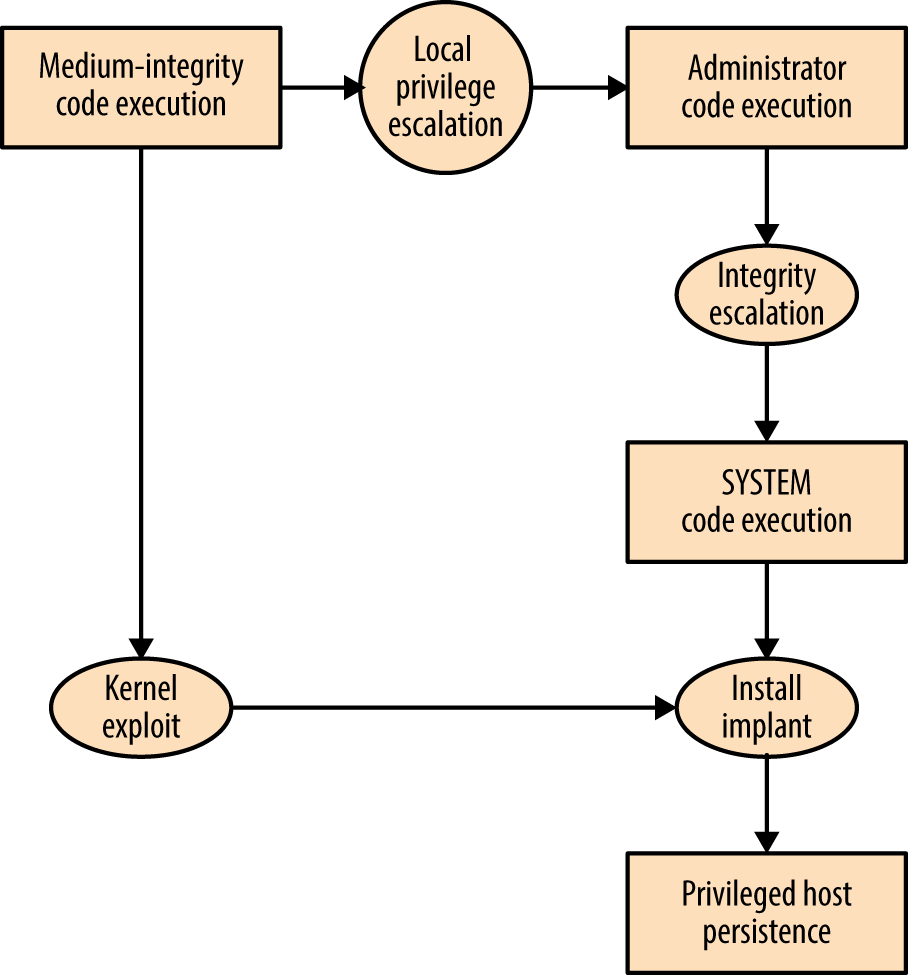

By combining adversarial goals with the exposed attack surface, we can plot attack graphs, as shown in Figures 3-4 and 3-5. In these examples, an adversary is presenting malicious content to Google Chrome with the goal of achieving native code execution and privileged host persistence.

Figure 3-4. Remote Chrome browser attack graph

Figure 3-5. Local privilege escalation attack graph

Here are two important takeaways from the graphs:

-

Exploiting Java is the easiest route to medium-integrity native code execution

-

Kernel exploits provide the quickest route to privileged host persistence

Adversaries follow the path of least resistance and reuse code and infrastructure to reduce cost. The attack surface presented by desktop software packages (e.g., web browsers, mail clients, and word processors) combined with the low cost of exploit research, development, and malicious content delivery, makes them attractive targets that will likely be exploited for years to come.

Note

Dino Dai Zovi’s presentation “Attacker Math 101” covers adversarial economics in detail, including other attack graphs, and discussing research tactics and costs.

Attacking C/C++ Applications

Operating systems, server software packages, and desktop client applications (including browsers) are often written in C/C++. Through understanding runtime memory layout, how applications fail to safely process data, and values that can be read and overwritten, you can seek to understand and mitigate low-level software flaws.

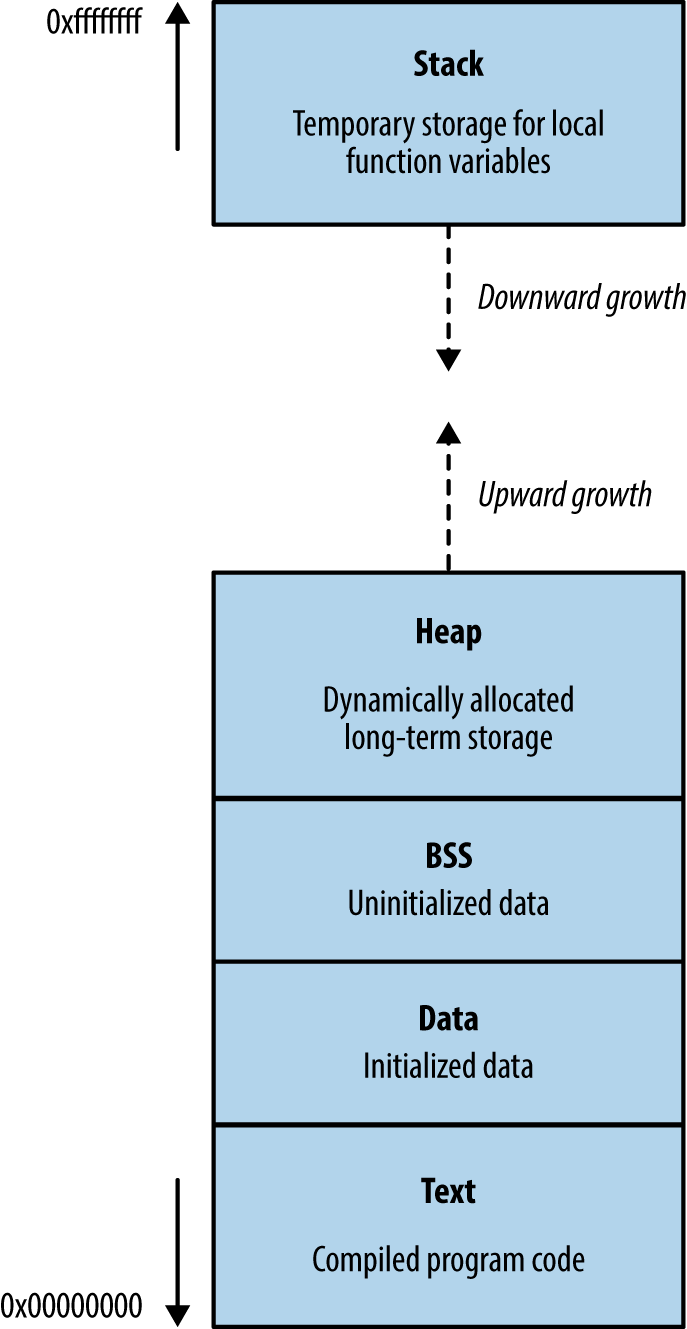

Runtime Memory Layout

Memory layout within different operating systems and hardware platforms varies. Figure 3-6 demonstrates a high-level layout commonly found within Windows, Linux, and similar operating systems on Intel and AMD x86 hardware. Input supplied from external sources (users and other applications) is processed and stored using the stack and heap. If software fails to handle input safely, an attacker can overwrite sensitive values and change program flow.

Figure 3-6. Runtime memory layout

The text segment

This segment contains the compiled executable code for the program and its dependencies (e.g., shared libraries). Write permission is typically disabled for two reasons:

-

Code doesn’t contain variables and so has no reason to overwrite itself

-

Read-only code segments may be shared between concurrent program copies

In days gone by, code would modify itself to increase runtime speed. Most processors are optimized for read-only code, so modification incurs a performance penalty. You can safely assume that if a program attempts to modify material within the text segment, it was unintentional.

The heap

The heap is often the largest segment of memory assigned by a program. Applications use the heap to store persistent data that exists after a function returns (and its local variables are no longer accessible). Allocator and de-allocator functions manage data on the heap. Within C, malloc is often used to allocate a chunk of memory, and free is called to de-allocate, although other functions might be used to optimize allocation.

Operating systems manage heap memory by using different algorithms. Table 3-1 shows the implementations used across a number of platforms.

| Implementation | Operating system(s) |

|---|---|

| GNU libc (Doug Lea) | Linux |

| AT&T System V | Solaris, IRIX |

| BSD (Poul-Henning Kamp) | FreeBSD, OpenBSD, Apple OS X |

| BSD (Chris Kingsley) | 4.4BSD, Ultrix, some AIX |

| Yorktown | AIX |

| RtlHeap | Windows |

Most applications use inbuilt operating system algorithms; however, some enterprise server packages, such as Oracle Database, use their own to improve performance. Understanding the heap algorithm in use is important, as the way by which management structures are used can differ (resulting in exposure under certain conditions).

The stack

The stack is a region of memory used to store local function variables (such as a character buffer used to store user input) and data used to maintain program flow. A stack frame is established when a program enters a new function. Although the exact layout of the frame and the processor registers used varies by implementation (known as calling convention), a common layout used by both Microsoft and GCC on Intel IA-32 hardware is as follows:

-

The function’s arguments

-

Stored program execution variables (the saved instruction and frame pointers)

-

Space for manipulation of local function variables

As the size of the stack is adjusted to create this space, the processor stack pointer (esp) register is modified to point to the end of the stack. The stack frame pointer (ebp) points to the start of the frame. When a function is entered, the locations of the parent function’s stack and frame pointers are saved on the stack, and restored upon exit.

Note

The stack is a last-in, first-out (LIFO) data structure: data pushed onto the stack by the processor exists at the bottom, and cannot be popped until all of the data above it has been popped.

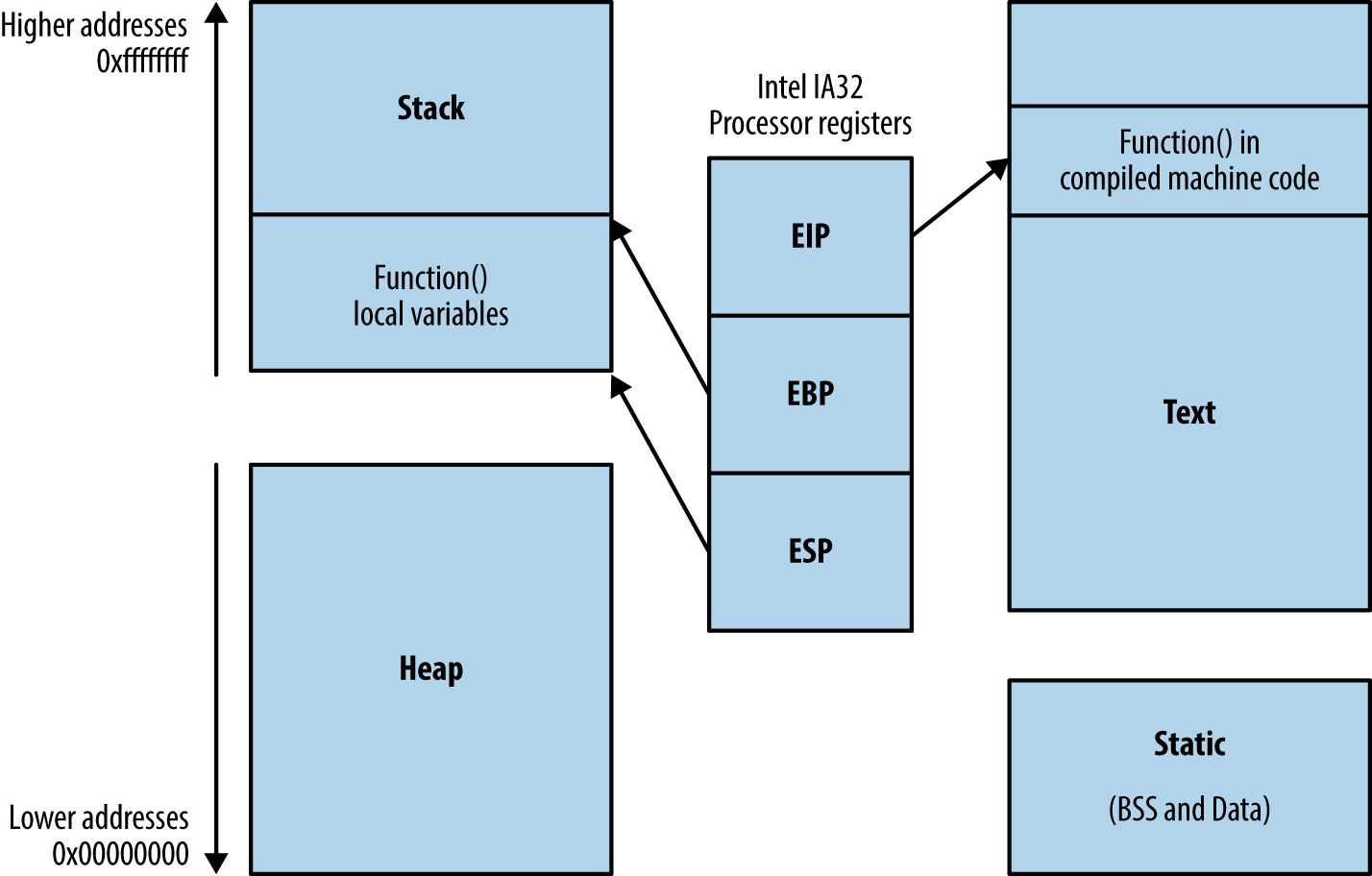

Processor Registers and Memory

Volatile memory contains code in the text segment, global and static variables in the data and BSS segments, data on the heap, and local function variables and arguments on the stack.

During program execution, the processor reads and interprets data by using registers that point to structures in memory. Register names, numbers, and sizes vary under different processor architectures. For simplicity’s sake, I use Intel IA-32 register names (eip, ebp, and esp in particular) here. Figure 3-7 shows a high-level representation of a program executing in memory, including these processor registers and the various memory segments.

Three important registers from a security perspective are the instruction pointer (eip) and the aforementioned ebp and esp. These are used to read data from memory during code execution, as follows:

-

eip points to the next instruction to be executed by the CPU

-

ebp should always point to the start of the current function’s stack frame

-

esp should always point to the bottom of the stack

Figure 3-7. Intel processor registers and runtime memory layout

In Figure 3-7, instructions are read and executed from the text segment, and local variables used by the function are stored on the stack. The heap, data, and BSS segments are used for long-term storage of data, because, when a function returns, the stack is unwound and local variables often overwritten by the parent function’s stack frame.

During operation, most low-level processor operations (e.g., push, pop, ret, and xchg) automatically modify CPU registers so that the stack layout is valid, and the processor fetches and executes the next instruction.

Writing to Memory

Overflowing an allocated buffer often results in a program crash because critical values used by the processor (e.g., the saved frame and instruction pointers on the stack, or control structures on the heap) are clobbered. Adversaries can take advantage of this behavior to change logical program flow.

Overwriting memory structures for gain

Depending on exactly which area of memory (e.g., stack, heap, or data segments) input ends up in—and overflows out of—an adversary can influence logical program flow. What follows is a list of structures that an attacker can target for gain:

- Saved instruction pointers

- When a new function is entered, a saved eip value is stored on the stack, which points to an address containing code to be used by the processor when the function returns (i.e., the parent function). Attackers might be able to overwrite the saved eip to point to a useful location, leading to code execution upon function exit.

- Saved frame pointers

- The location of the parent ebp is also stored on the stack when a new function is entered. Through exploiting an off-by-one error or similar condition, it is possible to shift the apparent location of the parent stack frame, populate it with malicious content (depending on the parent function and its expected variables), and benefit upon function return.

- Function pointers

- The heap, stack, and BSS memory segments often contain function pointers. For example, Microsoft Windows structured exception handler (SEH) pointer entries on the stack provide exception handling. Upon overwriting an SEH pointer, inducing a program crash will result in arbitrary code execution.7

- Heap control structures

- Depending on the implementation, heap control structures might exist which can be targeted. Upon manipulating control structures, the heap management process can be fooled into reading or writing to certain memory locations.

- Heap pointers

- C++ objects store function pointers in heap vtable structures. Pointing a vtable to a different memory location results in new contents being used during function pointer lookup, yielding control of execution flow. Other linked data structures and pointers can exist on the heap that can be used to perform a controlled read or write operation, depending on the application.

- Global variables

- Programs often store sensitive material within global variables in the data segment, such as user ID and authentication flag values. By passing malicious environment variables to a vulnerable program (e.g., /bin/login under Oracle Solaris8), you can bypass authentication and gain system access.

- Global offset table (GOT) entries

- Unix ELF binaries support dynamic linking of libraries containing shared functions (such as printf, strcpy, fork, and others9). The GOT exists in the data segment, and is used to specify the addresses of library functions. As this segment is usually writable, an adversary can seek to overwrite addresses of shared functions within the GOT and commandeer logical program flow.

- Procedure linkage table (PLT) entries

- ELF binaries use a procedure linkage table, which contains addresses of shared functions within the text segment. Although PLT entries cannot be overwritten, they can be used as an entry point to low-level system calls such as write(2), which can be used to read process memory and bypass security controls.

- Constructors (.ctors) and destructors (.dtors)

- ELF binary constructors are defined within the data segment; they are functions executed before a program enters main(). Destructors are defined in a similar manner and executed when the process exits. Practically, destructors are targeted to execute code when the parent function exits.

- Application data

- Data used by the application to track state (e.g., authentication flags) or locate material in memory can be overwritten and cause an application to act unexpectedly.

Reading from Memory

Systems increasingly rely on secrets stored in memory to operate in a secure manner (e.g., encryption keys, access tokens, authentication flags, and GUID values). Upon obtaining sensitive values through an information leak or side channel attack, an adversary can undermine the integrity of a system.

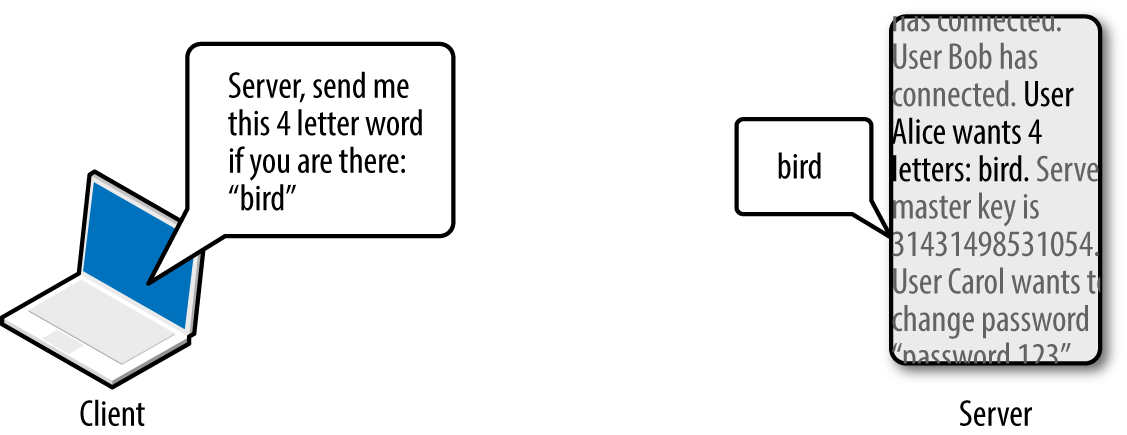

OpenSSL TLS heartbeat extension information leak

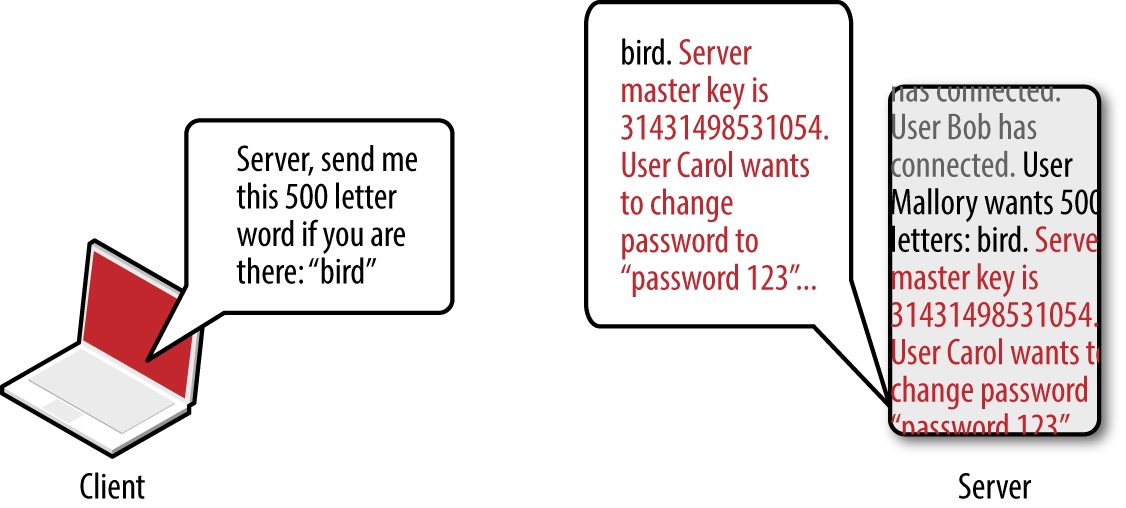

OpenSSL versions 1.0.1 through 1.0.1f are susceptible to a flaw known as heartbleed,10 as introduced into the OpenSSL codebase in March 2012 and discovered in early 2014 by Neel Mehta of Google.11 Figure 3-8 demonstrates a normal TLS heartbeat request, and Figure 3-9 demonstrates the heap over-read, revealing server memory upon sending a malformed TLS heartbeat request.12

Figure 3-8. A server fulfilling a TLS heartbeat request

Figure 3-9. A malicious TLS heartbeat request revealing heap content

The defect leaks up to 64K of heap content per request. By sending multiple requests, attackers can extract RSA private keys from a server application (such as Apache HTTP Server or Nginx) using a vulnerable OpenSSL library. Attackers can use Metasploit13 to dump the contents of the heap and extract private keys.

Reading memory structures for gain

Secrets stored in volatile memory that might be exposed include the following:

- Private keys

- Applications provide transport security through TLS, SSH, and IPsec. By compromising the private key of a server, you can impersonate it without detection (via MITM) and compromise session content if perfect forward secrecy is not used.

- Other cryptographic materials

- Important values used by cryptographic primitives include keys, seeds, and initialization vectors. If adversaries are able to compromise these, they can attack the cryptosystem with unintended consequences.

- Sensitive values used by security features

- Compiler and OS security mechanisms including ASLR rely on secrets in memory. These can be bypassed if values such as pointer addresses are obtained.

- Credentials

- Applications often use micro-services, third-party APIs, and external data sources. If credentials for these are known, an attacker can use them to obtain sensitive data.

- Session tokens

- Web and mobile applications use session tokens to track authenticated users. By obtaining these, you can impersonate legitimate users, including administrators.

Warning

As systems become increasingly distributed, protection of secrets (e.g., API keys and database connection strings) becomes a high priority. Severe compromises resulting in PII data exposure in recent years have stemmed from credentials leaked in this manner.

Compiler and OS Security Features

To provide resilience from attacks resulting in sensitive data being overwritten, or read from vulnerable applications, vendors implement security features within their operating systems and compilers. A paper titled “SoK: Eternal War in Memory” details mitigation strategies and attack tactics applying to languages with memory safety issues (e.g., C/C++). What follows is a list of common security features, their purpose, and details of the platforms that use them:

- Data execution prevention (DEP)

- Within most operating systems (including Microsoft Windows, Apple OS X, and Linux), DEP is used to mark writable areas of memory, including the stack and the heap, as non-executable. DEP is used with processor hardware to prevent execution of instructions from writable areas of memory. There are exceptions to DEP support and coverage, however: many 32-bit binaries are incompatible with DEP, and some libraries (e.g., Microsoft Thunk Emulation14) legitimately execute instructions from the heap.

- Address space layout randomization (ASLR)

- Platforms including Linux, Oracle Solaris, Microsoft Windows, and Apple OS X also support ASLR, which is used to randomize the locations of loaded libraries and binary code. Randomization of memory makes it difficult for an attacker to commandeer logical program flow; however, implementation flaws exist, and some libraries are compiled without ASLR support (e.g., Microsoft’s mscorie.dll under Windows 7).

- Code signing

- Apple’s iOS and other platforms use code signing,15 by which each executable page of memory is signed, and instructions executed only if the signature is correct.

- SEHOP

- To prevent SEH pointers from being overwritten and abused within Windows applications, Microsoft implemented SEHOP,16 which checks the validity of a thread’s exception handler list before allowing any to be called.

- Pointer encoding

- Function pointers can be encoded (using XOR or other means) within Microsoft Visual Studio and GCC. If encoded pointers are overwritten without applying the correct XOR operation first, they cause a program crash.

- Stack canaries

- Compilers including Microsoft Visual Studio, GCC, and LLVM Clang place canaries on the stack before important values (e.g., saved eip and function pointers on the stack). The value of the canary is checked before the function returns; if it has been modified, the program crashes.

- Heap protection

- Microsoft Windows and Linux systems include sanity checking within heap management code. These improvements protect against double free and heap overflows resulting in control structures being overwritten.

- Relocation read-only (RELRO)

- The GOT, destructors, and constructors entries within the data segment can be protected through instructing the GCC linker to resolve all dynamically linked functions at runtime, and marking the entries read-only.

- Format string protection

- Most compilers provide protection against format string attacks, in which format tokens (such as

%sand%x) and other content is passed to functions including printf, scanf, and syslog, resulting in an attacker writing to or reading from arbitrary memory locations.

Circumventing Common Safety Features

You can modify an application’s execution path through overwriting certain values in memory. Depending on the security mechanisms in use (including DEP, ASLR, stack canaries, and heap protection), you might need to adopt particular tactics to achieve arbitrary code execution, as described in the following sections.

Bypassing DEP

DEP prevents the execution of arbitrary instructions from writable areas of memory. As such, you must identify and borrow useful instructions from the executable text segment to achieve your goals. The challenge is one of identifying sequences of useful instructions that can be used to form return-oriented programming (ROP) chains; the following subsections take a closer look at these.

CPU opcode sequences

Processor opcodes vary by architecture (e.g., Intel and AMD x86-64, ARMv7, SPARC V8, and so on). Table 3-2 lists useful Intel IA-32 opcodes, corresponding instruction mnemonics, and notes. General registers (eax, ebx, ecx, and edx) are used to store 32-bit (4-byte word) values that are manipulated and used during different operations.

| Opcode | Assembly | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| \x58 | pop eax |

Remove the last word and write to eax |

| \x59 | pop ecx |

Remove the last word and write to ecx |

| \x5c | pop esp |

Remove the last word and write to esp |

| \x83\xec\x10 | sub esp, 10h |

Subtract 10 (hex) from the value stored in esp |

| \x89\x01 | mov (ecx), eax |

Write eax to the memory location that ecx points to |

| \x8b\x01 | mov eax, (ecx) |

Write the memory location that ecx points to to eax |

| \x8b\xc1 | mov eax, ecx |

Copy the value of ecx to eax |

| \x8b\xec | mov ebp, esp |

Copy the value of esp to ebp |

| \x94 | xchg eax, esp |

Exchange eax and esp values (stack pivot) |

| \xc3 | ret |

Return and set eip to the current word on the stack |

| \xff\xe0 | jmp eax |

Jump (set eip) to the value of eax |

Many of these operations update the esp (stack pointer) register so that it points to the bottom of the stack. For example, push decrements the pointer by 4 when a word is written to the stack, and pop increments it by 4 when one is removed.

The ret instruction is important within ROP—it is used to transfer control to the next instruction sequence, as defined by a return address located on the stack. As such, each sequence must end with a \xc3 value or similar instruction that transfers execution.

Program binaries and loaded libraries often contain millions of valid CPU instructions. By searching the data for particular sequences (e.g., useful instructions followed by \xc3), you can build simple programs out of borrowed code. Two tools that scan libraries and binaries for instruction sequences are ROPgadget17 and ROPEME18.

Writing data to an arbitrary location in memory

Upon scanning the text segment for instructions, you might find the following two sequences (the first value is the location in memory at which each sequence is found, followed by the hex opcodes, and respective instruction mnemonics):

0x08056c56: "\x59\x58\xc3 <==> pop ecx ; pop eax ; ret" 0x080488b2: "\x89\x01\xc3 <==> mov (ecx), eax ; ret"

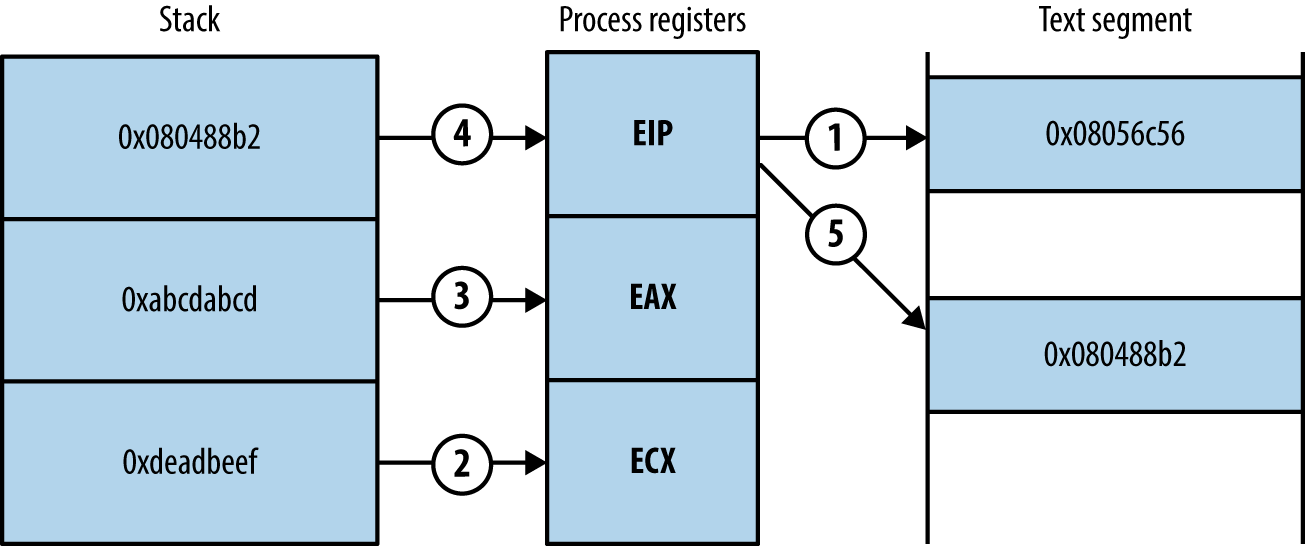

Both sequences are only three bytes long. Before you chain them together for execution, you first populate the stack, as shown in Figure 3-10.

Figure 3-10. Prepared stack frame and CPU register values

Upon executing the first sequence from 0x08056c56, the following occurs:

-

The two words at the bottom of the stack are removed and stored within the ecx and eax registers. Each pop instruction also increments esp by 4 each time so that it points to the bottom of the stack.

-

The return instruction (ret) at the end of the first sequence reads the next word on the stack, which points to the second chain at

0x080488b2. -

The second sequence writes the eax value to the memory address to which ecx points.

ROP gadgets

Useful sequences are chained to form gadgets. Common uses include:

-

Reading and writing arbitrary values to and from memory

-

Performing operations against values stored in registers (e.g., add, sub, and, xor)

-

Calling functions in shared libraries

When attacking platforms with DEP, ROP gadgets are often used as an initial payload to prepare a region of memory that is writable and executable. This is achieved through building fake stack frames for memory management functions (i.e., memset and mmap64 within Linux, and VirtualAlloc and VirtualProtect within Microsoft Windows) and then calling them. Through using borrowed instructions to establish an executable region, you inject and finally run arbitrary instructions (known as shellcode).

Dino Dai Zovi’s presentation19 details the preparation of ROP gadgets during exploitation of the Microsoft Internet Explorer 8 Aurora vulnerability,20 using a stack pivot to establish an attacker-controlled stack frame.

Bypassing ASLR

ASLR jumbles the locations of pages in memory. The result is that, upon exploiting a flaw (such as an overflow condition), you do not know the location of either useful instructions or data. Example 3-1 shows Ubuntu Linux randomizing the base address for each loaded library upon program execution.

Although these libraries are loaded at random locations, useful functions and instruction sequences exist at known offsets (because the page location is randomized, as opposed to the contents). The problem is then one of identifying the base address at which each library is loaded into memory.

ASLR is not enabled under the following scenarios:

-

The program binary is not compiled as a position-independent executable (PIE)

-

Shared libraries used by the program are not compiled with ASLR support

In these cases, you simply refer to absolute locations within binaries that opt out of ASLR. Certain DLLs within Microsoft Windows are compiled without ASLR—if a vulnerable program loads them, you can borrow instructions and build ROP gadgets.

Some platforms load data at fixed addresses, including function pointers. For example, during Pwn2Own 2013, VUPEN used the KiFastSystemCall and LdrHotPathRoutine function pointers to bypass ASLR on Windows 7.21 These two pointers exist at fixed addresses on unpatched systems, which you can use to execute arbitrary instructions.

If the program binary and loaded libraries use dynamic base addresses, you can pursue other means to calculate and obtain them, including the following:

-

Undertaking brute-force attacks to locate valid data and instructions

-

Revealing memory contents via information leak (e.g., a heap over-read)

Brute-force is achievable under certain conditions; dependent on the level of system access, along with the operation of the target application and underlying operating system. A 32-bit process is often easier to attack than a 64-bit one because the number of iterations to grind through is lower.

Bypassing stack canaries

Depending on their implementation, an attacker can overcome stack canary mechanisms through the following methods:

-

Using an information leak bug to reveal the canary

-

Inferring the canary through iterative overflow attempts (if the canary is static)

-

Calculating the canary through a weakness in the implementation

-

Overwriting a function pointer and diverting logical program flow before the canary is checked (possible when exploiting Microsoft SEH pointers)

-

Overwriting the value the canary is checked against

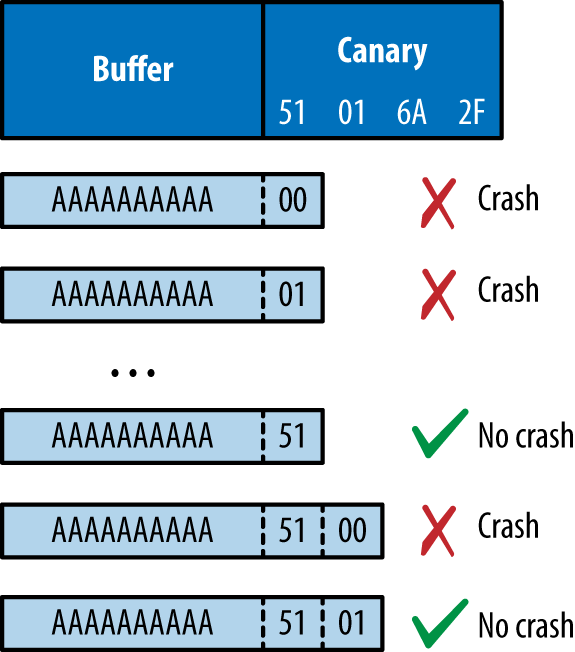

Inferring the canary as per the second bullet is an interesting topic—Andrea Bittau and others at Stanford University published a paper in 2014 titled “Hacking Blind”,22 in which they successfully remotely exploit Nginx via CVE-2013-2028. The target system ran a 64-bit version of Linux with stack canaries, DEP, and ASLR.

Bittau et al.’s attack works by identifying the point at which their material overwrites the canary (causing a crash), and then iteratively overwriting it byte-by-byte, until the service no longer crashes, meaning the canary is valid. The stack layout across subsequent overflow attempts is shown in Figure 3-11.

Figure 3-11. Inferring a stack canary through overwriting it

Writing past the canary modifies the saved frame and instruction pointers. By inferring these through writing byte-by-byte in the same fashion, you can begin to map memory layout (identifying the location of the text segment and the parent stack frame) and bypass ASLR.

Logic Flaws and Other Bugs

I’ve demonstrated how attackers abuse operating systems, server software, and desktop applications through memory manipulation. Many web and mobile applications are developed using memory-safe languages (including Java and Microsoft .NET), and so attackers must exploit logic flaws and other vulnerabilities to achieve certain goals. Common defects result in the following flaws being exploited:

-

Inference of usernames within account logon or password reset logic

-

Session management issues around generation and use of tokens (e.g., session fixation, whereby a session token is not regenerated after a user authenticates)

-

Encapsulation bugs, wherein requests are honored and materials processed without question (e.g., direct object reference, XXE flaws, or malicious JavaScript used within XSS attacks)

-

Information leak flaws, by which crafted requests reveal materials from the file system or backend data storage (such as a database or key-value store)

Throughout the book you will find that vulnerabilities range from subtle low-level memory management defects, through to easily exploitable logic flaws. It is critical to understand the breadth of potential issues, so that you can implement effective security controls through defense in depth.

Cryptographic Weaknesses

As system components become increasingly decoupled and perimeters collapse, dependence on cryptography to enforce security boundaries (by generating random numbers, HMAC values, and providing confidentiality) increases.

Here are some common cryptographic functions found within computer systems:

-

Protocols providing transport layer security (such as TLS and IPsec)

-

Encryption of data at-rest

-

Signing of data to provide integrity checking (e.g., HMAC calculation)

Exploitable flaws can exist in any of these, through improper implementation or defects within the underlying protocol. A failure within one component can also allow an attacker to exploit another (e.g., insufficient integrity checking allowing content to be sent to an oracle, in turn revealing an encryption key).

If a PRNG generates predictable values, an adversary can take advantage of this behavior. In August 2013, the Android PRNG was found to be insecure,23 leading to mobile Bitcoin wallets becoming accessible to attackers.24

Exploitation of many weaknesses in cryptographic components often requires particular access, such as network access to intercept traffic, or local operating system access to obtain values used by a PRNG.

Key compromise can result in a catastrophic failure. In 2014, an attacker obtained the server seed values used by the Primedice gaming site, resulting in a loss of around $1 million in Bitcoin.25

Popular classes of attack against cryptosystems include the following:

- Collisions

- Message digests used for integrity checking can be circumvented if a collision is found, where two different messages generate the same digest (signature). MD5 collisions can be easily generated.26 A collision can be used to generate malicious material (e.g., a certificate or ticket) which is in turn trusted.

- Modification of ciphertext

- If ciphertext generated by a stream cipher (e.g., RC4) or certain block ciphers (ECB, CBC, and CTR) lacks integrity checking, an adversary can modify it to generate useful plaintext upon processing by a recipient. Bit flipping and block rearranging can produce predictable changes to plaintext upon decryption.

- Replay of ciphertext

- Many protocols (including older 802.11 WiFi standards) do not track state. Encrypted 802.11 network frames can be replayed to an access point or client with unintended results, for example. In an authentication context, implementations lacking state tracking or use of a cryptographic nonce are also susceptible to replay attack—by which an attacker captures a token and later presents it to authenticate.

- Side channel attacks

- Sensitive material is sometimes leaked through oracles. In most cases, a side channel attack involves interacting with either timing or error oracles. A timing oracle leaks information based on the timing of events, and an error oracle allows an attacker to infer a secret (usually byte-by-byte, in an iterative fashion) based on server error messages.

Other attacks exist depending on system implementation. When designing a cryptosystem, it is critical to consider both secure key generation and handling, along with the application of correct cryptographic primitives (e.g., using an HMAC instead of a simple hash function). The order of operations can also introduce vulnerability. For example, sign-then-encrypt can lead to problems because ciphertext is not authenticated.

Vulnerabilities and Adversaries Recap

Flaws may exist in different layers of a computer system:

-

Hardware, infrastructure responsible for physical data handling

-

Software, application components providing computation and data processing

-

Wetware, users interacting with software and drawing conclusions from data

This book describes vulnerabilities found throughout the software realm and touches on hardware and wetware attacks (through discussion of physical system compromise and social engineering).

You can understand how adversaries influence or observe systems for gain through threat modeling. Upon mapping exposed paths, you can prepare security controls to mitigate known risks and improve safety.

1 John Leyden, “Linode Hackers Escape with $70k in Daring Bitcoin Heist”, The Register, March 2, 2012.

2 Yinqian Zhang et al., “Cross-VM Side Channels and Their Use to Extract Private Keys”, proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Raleigh, North Carolina, October 16–18, 2012.

3 Katrina Tsipenyuk, Brian Chess, and Gary McGraw, “Seven Pernicious Kingdoms: A Taxonomy of Software Security Errors”, IEEE Security & Privacy (November/December 2005).

4 Sean Gallagher, “Photos of an NSA ‘Upgrade’ Factory Show Cisco Router Getting Implant”, Ars Technica, May 14, 2014.

5 Jesse Robbins, “Failure Happens: Taser-Wielding Thieves Steal Servers, Attack Staff, and Cause Outages at Chicago Colocation Facility”, O’Reilly Radar, November 3, 2007.

6 Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols, “Google, the NSA, and the Need for Locking Down Datacenter Traffic”, ZDNet, October 30, 2013.

7 David Litchfield, “Defeating the Stack-Based Buffer Overflow Prevention Mechanism of Microsoft Windows 2003 Server”, NGSSoftware Ltd., September 8, 2003.

8 See CVE-2001-0797 and CVE-2007-0882.

9 As found in the GNU C library.

10 See CVE-2014-0160.

11 See this vulnerability listed at https://www.google.com/about/appsecurity/research/.

13 Metasploit openssl_heartbleed module.

14 Alexander Sotirov and Mark Dowd, “Bypassing Browser Memory Protections”, presented at BlackHat USA, Las Vegas, NV, August 2–7, 2008.

15 For more information, see “Code Signing” on Apple’s Developer Support page.

16 See “Preventing the Exploitation of Structured Exception Handler (SEH) Overwrites with SEHOP”, Microsoft TechNet Blog, Februrary 2, 2009.

17 Jonathan Salwan, “ROPgadget – Gadgets Finder and Auto-Roper”, Shell-storm.org, March 12, 2011.

18 longld, “ROPEME – ROP Exploit Made Easy”, VNSecurity.net, August 13, 2010.

19 Dino A. Dai Zovi, “Practical Return-Oriented Programming”, presented at RSA Conference 2010, San Francisco, CA, March 1–5, 2010.

20 See CVE-2010-0249.

21 See CVE-2013-2556.

22 Andrea Bittau et al., “Hacking Blind”, proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Berkeley, CA, May 18–21, 2014.

23 See CVE-2013-7373.

24 Bitcoin, “Android Security Vulnerability”, Bitcoin.org, August 11, 2013.

25 Stunna, “Breaking the House”, Medium.com, June 28, 2015.

26 Nat McHugh, “How I Created Two Images with the Same MD5 Hash”, Nat McHugh Blog, October 31, 2014.