Chapter 11. Assessing TLS Services

This chapter describes the steps you should undertake to identify weaknesses in TLS services. Before we get to that, I would like to take a moment to discuss how TLS came to be, and why this book avoids mentioning SSL for the most part.

Netscape Navigator dominated the browser market in the 1990s with around 70 percent market share. Between 1994 and 1996, Netscape Communications developed its own transport encryption mechanism known as Secure Sockets Layer (SSL). Due to its market dominance, SSL was widely adopted. The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) formed a committee to turn the Netscape SSL 3.0 protocol into a standard—the official name being Transport Layer Security (TLS), as ratified by RFC 2246 in 1999.

Entire books are dedicated to the topic. An excellent reference that provides additional layers of detail around TLS and its features is Ivan Ristić’s Bulletproof SSL and TLS (Feisty Duck, 2014).1

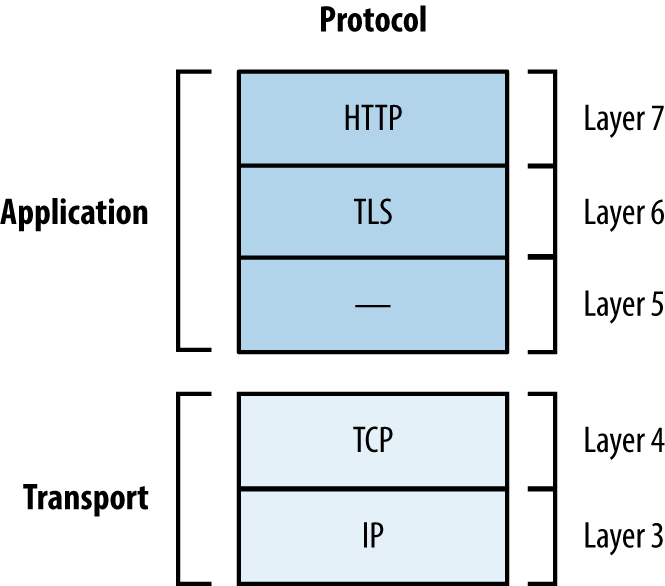

Figure 11-1 shows TLS running at OSI Layer 6, providing transport security to the application protocol above (HTTP, in this case). This chapter describes the mechanics of TLS version 1.2,2 along with assessment tactics that should be adopted for TLS and legacy SSL endpoints. SSL 3.0 is particularly flawed and support is being rapidly phased-out online.

Figure 11-1. TLS belongs to Layer 6

Note

TLS relies on TCP as the underlying transport protocol. DTLS3 is a lesser-known protocol that can run atop of Layer 4 datagram protocols including UDP, DCCP,4 and SCTP. Web browsers including Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox support DTLS.

TLS Mechanics

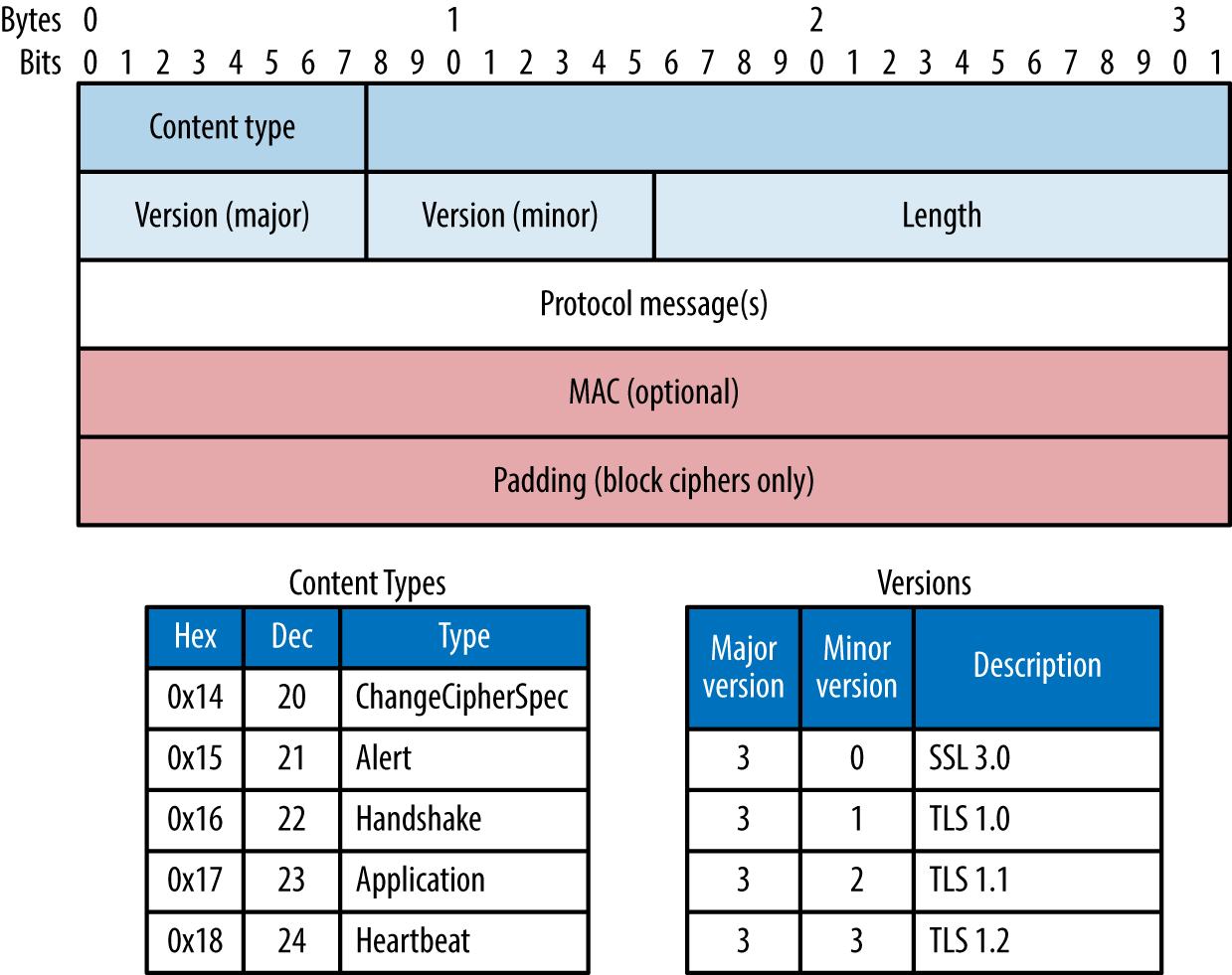

Material is sent between peers via records. Figure 11-2 shows the format of a TLS record, including the protocol version (e.g., SSL 3.0 or TLS 1.2), content type (e.g., handshake or application data), and message content.

Figure 11-2. TLS record format, content types, and protocol versions

Session Negotiation

TLS sessions are established via Handshake records to do the following:

-

Agree upon the protocol and cipher suite

-

Agree upon compression method and extensions

-

Transmit random numbers (known as nonces)

-

Transmit X.509 digital certificates and encryption keys

-

Verify ownership of each other’s certificates

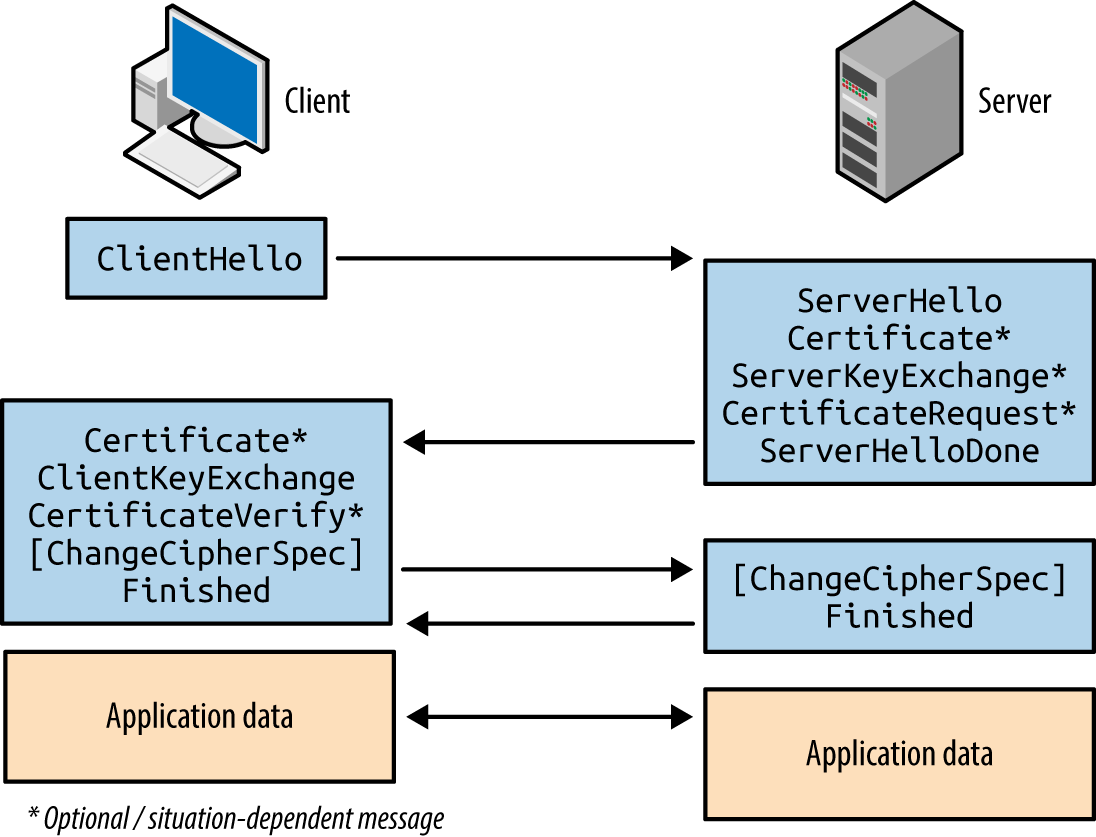

Authentication occurs and a master secret is generated. Peers send Change Cipher Spec records to instruct each other that material from now on will be sent encrypted and signed, along with a Finished message containing an HMAC of the previous messages. Upon verifying the contents of each Finished message, the session is established and data is sent via Application records. The process is summarized in Figure 11-3 and detailed in the following sections.

Figure 11-3. TLS handshake message flow

Client Hello

The first message sent by the client includes the following fields:

-

The TLS version the client wants to use (i.e., the highest supported)

-

A random 256-bit number

-

The session ID value the client is using for the connection (if any)

-

A list of preferred cipher suites (ordered favorite first)

-

An optional list of preferred TLS compression methods5

-

TLS extension data communicating the client’s abilities to the server6

Two fields of particular importance are the TLS version and list of cipher suites. Compression is slated for removal in TLS 1.3, and extensions include support for elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) and secure renegotiation.

Server Hello

Upon receiving a Client Hello message, the server responds with the following:

-

The TLS version the server wants to use

-

A random 256-bit number

-

The session ID value the server wants to use (if any)

-

The selected cipher suite for the session

-

The selected compression method

-

TLS extension data

At this point, the peers have agreed on key exchange and authentication algorithms, additional features to use, and shared their random values. If an authenticated key exchange mechanism is selected, certificates and additional materials are then shared.

Server Certificate and Key Exchange

The server uses a Certificate message to transmit its certificate. In some cases (e.g., using Diffie-Hellman with ephemeral keys) the certificate does not contain key material and a Server Key Exchange message is used to send the parameters.

If the server wants to authenticate a client, a Certificate Request message is also sent. Mutual authentication introduces a useful layer of security (preventing unauthorized access to the service running atop of TLS), although most systems do not operate in this manner.

The server then sends a Server Hello Done message to indicate that it has finished sending messages and is waiting for a response from the client.

Client Certificate and Key Exchange

If requested, the client sends its certificate through a Client Certificate message. A Client Key Exchange message is next used to send keys to the server using one of three formats:

- RSA

- The client sends a premaster secret, encrypted by using the public key of the server. The parties independently calculate a master secret and key block (using the 256-bit random values and the 384-bit premaster secret). If the server can decrypt this message and generate a valid key block, the client has proven its authenticity.

- Diffie-Hellman (DH)

- The client sends its DH public value and calculates the premaster secret.

- Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH)

- The client sends its ECDH public value (optionally signed using DSA or RSA).

If the client previously sent a Client Certificate message (performing mutual authentication), a Certificate Verify message authenticates the client by generating an HMAC of the messages up to this point using its private key.

Finished

The client sends a Change Cipher Spec record to notify the server that all data to follow will be encrypted. The client also sends a Finished message containing an HMAC of the conversation. The server performs the same operation—sending a Change Cipher Spec record to instruct the client that material from now on will be encrypted, and a Finished message containing an HMAC of the exchange. The client and server assure the integrity of the conversation and authenticate each other upon validating the HMAC values.

Cipher Suites

TLS 1.2 cipher suite entries define the following parameters:

-

Key exchange and authentication method

-

Bulk symmetric encryption algorithm, key length, and mode

-

Message authentication code (MAC) algorithm and PRF

RFC 5246 lists 36 basic cipher suites for TLS 1.2. RFC 4492 introduced a further 25 ECC suites that are preferred by many web browsers, including Google Chrome.7 To demonstrate the format and layout of cipher suites, two examples are as follows:

TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_MD5- RSA is used for both key exchange and authentication. Once authenticated, the peers use 128-bit RC4 to encrypt data, and 128-bit HMAC-MD5 to ensure integrity.

TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA- ECDHE using the elliptic curve digital signature algorithm (ECDSA) for authentication. Once authenticated, the peers use 256-bit AES in cipher block chaining mode (AES_256_CBC) to encrypt data, and 160-bit HMAC-SHA1 to ensure integrity.

To list the supported ciphers within OpenSSL from the command line, use the ciphers argument shown in Example 11-1 (output stripped for brevity). The Kx value defines the key exchange algorithm; Au denotes the authentication mechanism; Enc defines the bulk symmetric encryption algorithm and key length; and Mac defines the HMAC function for integrity checking.

Example 11-1. Listing supported cipher suites in OpenSSL

root@kali:~# openssl ciphers -v ECDHE-RSA-AES256-GCM-SHA384 TLSv1.2 Kx=ECDH Au=RSA Enc=AESGCM(256) Mac=AEAD ECDHE-ECDSA-AES256-GCM-SHA384 TLSv1.2 Kx=ECDH Au=ECDSA Enc=AESGCM(256) Mac=AEAD ECDHE-RSA-AES256-SHA384 TLSv1.2 Kx=ECDH Au=RSA Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA384 ECDHE-ECDSA-AES256-SHA384 TLSv1.2 Kx=ECDH Au=ECDSA Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA384 ECDHE-RSA-AES256-SHA SSLv3 Kx=ECDH Au=RSA Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA1 ECDHE-ECDSA-AES256-SHA SSLv3 Kx=ECDH Au=ECDSA Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA1 SRP-DSS-AES-256-CBC-SHA SSLv3 Kx=SRP Au=DSS Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA1 SRP-RSA-AES-256-CBC-SHA SSLv3 Kx=SRP Au=RSA Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA1 SRP-AES-256-CBC-SHA SSLv3 Kx=SRP Au=SRP Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA1 DHE-DSS-AES256-GCM-SHA384 TLSv1.2 Kx=DH Au=DSS Enc=AESGCM(256) Mac=AEAD DHE-RSA-AES256-GCM-SHA384 TLSv1.2 Kx=DH Au=RSA Enc=AESGCM(256) Mac=AEAD DHE-RSA-AES256-SHA256 TLSv1.2 Kx=DH Au=RSA Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA256 DHE-DSS-AES256-SHA256 TLSv1.2 Kx=DH Au=DSS Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA256 DHE-RSA-AES256-SHA SSLv3 Kx=DH Au=RSA Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA1 DHE-DSS-AES256-SHA SSLv3 Kx=DH Au=DSS Enc=AES(256) Mac=SHA1

Note

You might notice the AEAD values8 used for integrity checking in Example 11-1. GCM ciphers (e.g., AES256-GCM) provide both encryption and integrity protection, so the value is set to AEAD (versus SHA-1, SHA-256, or SHA-384). The algorithm also becomes the pseudorandom function (PRF) used to generate the master secret.

Key Exchange and Authentication

TLS supports many key exchange and authentication mechanisms, by which values sent between peers are used to generate a premaster secret, master secret, and a key block. Popular mechanisms are:

-

RSA key exchange and authentication

-

DH static key exchange, authenticated using RSA or DSA

-

ECC versions of DH or DHE, authenticated using RSA, DSA, or ECDSA

Less common algorithms supported by OpenSSL and others include SRP9 and PSK.10

RSA key exchange and authentication

During negotiation, both the client and server send random 256-bit values to each other. The first 32 bits should be based on the local system time, and the remaining 224 bits should be generated by using a PRNG.

The client generates an additional random 368-bit number, and appends it to the 16-bit value of the TLS version for the session (sent previously within the Client Hello message). This 384-bit value is the premaster secret.

The premaster secret is encrypted by using the RSA public key of the server, and sent using a Client Key Exchange message. Use of the server’s public key means that this method of key exchange does not provide forward secrecy.11 However, because the plaintext value stipulates the previously specified TLS protocol version, rollback and in-band downgrade attacks are prevented.

Generating the master secret and key block

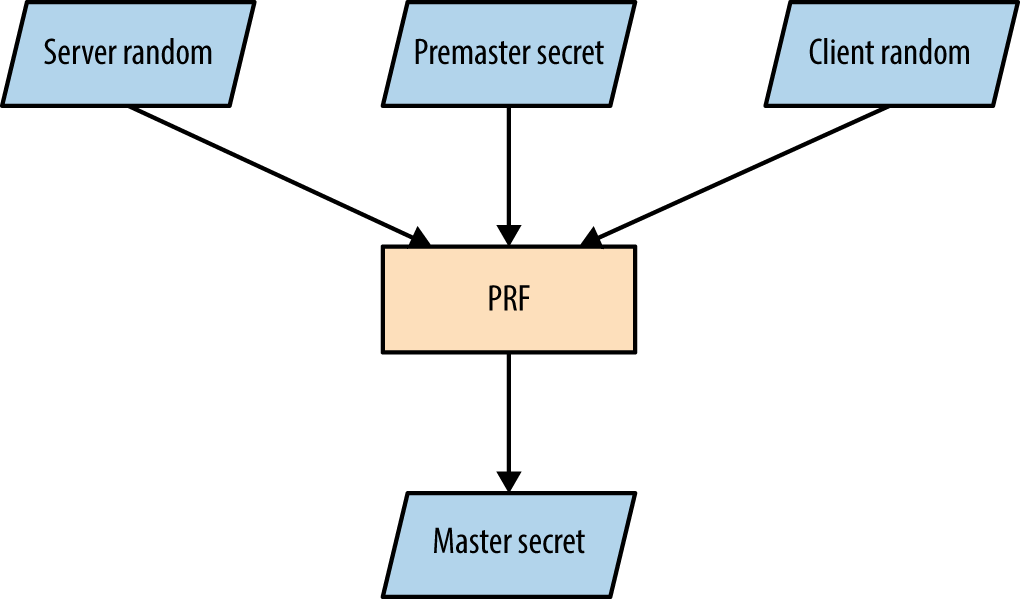

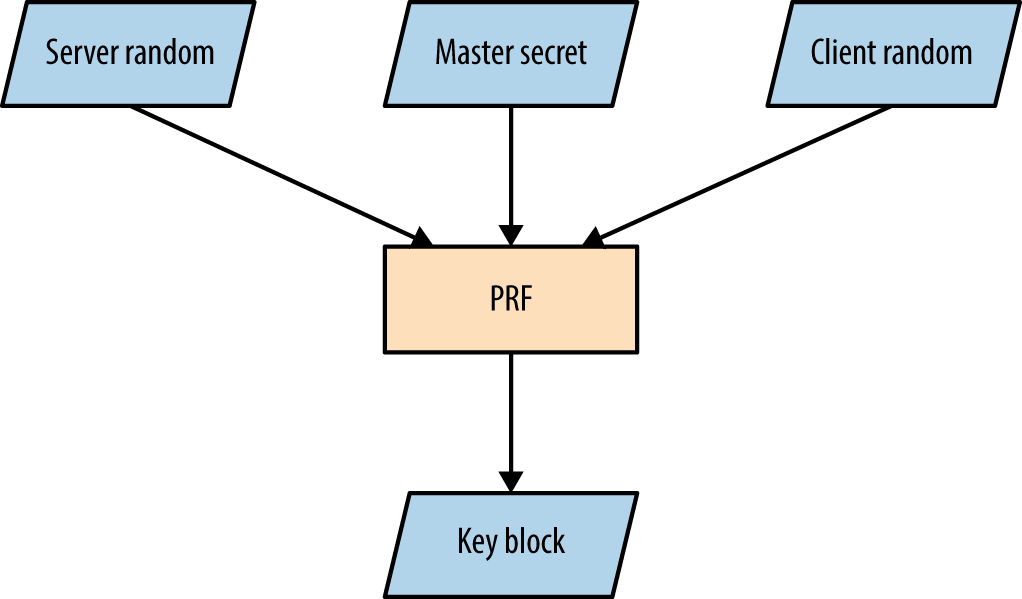

The client and server use the same PRF to generate a master secret and key block, as shown in Figures 11-4 and 11-5. The PRF within TLS 1.2 is negotiable via the cipher suite and defaults to SHA-256. Older versions of TLS and SSL use MD5 and SHA-1.

Figure 11-4. Master secret generation

Figure 11-5. Key block generation

The master secret is always 384 bits in length. However, depending on the PRF and cipher suite, the key block can vary in size. For example, AES_256_CBC_SHA256 requires a 1,024-bit block, which is split into three key pairs:

-

Two 256-bit MAC keys

-

Two 256-bit encryption keys

-

Two 256-bit initialization vector (IV) values

The client and server use the keys to encrypt, decrypt, sign, and verify data.

DH key exchange

DH key exchange lets two parties establish a secret (the premaster secret in this case) over a public channel. Key exchange using RSA differs, as a premaster secret is generated by the client and sent to the server (encrypted by using the server’s public key).

DH is an anonymous key agreement protocol, and so RSA and DSA are used to provide authentication. TLS 1.2 defines five basic modes of operation, as listed in Table 11-1. ECC modes are discussed later in this chapter.

| Cipher suite | Key type | Transmitted via |

|---|---|---|

DH_RSA |

Static | Server certificate (RSA signed) |

DH_DSS |

Server certificate (DSA signed) | |

DHE_RSA |

Ephemeral | Server Key Exchange message (RSA signed) |

DHE_DSS |

Server Key Exchange message (DSA signed) | |

DH_anon |

Server Key Exchange message (unsigned) |

Note

The Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA) is part of the Digital Signature Standard (DSS) published by NIST in FIPS 186-4. Most documents refer to DSA; however, some use DSS to denote the mechanism.

DH public keys (known as parameters) are sent from server to client using Certificate and Server Key Exchange messages. Static parameters are found in the server certificate and derived from the server’s private key. Ephemeral parameters are generated for each TLS session and provide forward secrecy.

Peers perform the following to generate a premaster secret:

-

The server sends DH domain parameters (dh_g and dh_p) to the client, which are signed if an authenticated mode is used. The dh_p value should be a large prime number and the dh_g value should be a small primitive root (also known as the generator).

-

The client generates a private random number (rand_c) and performs the following operation, raising the dh_g value to the power of rand_c and applying it to modulo12 dh_p to calculate dh_Yc:

dh_grand_c mod dh_p = dh_Yc -

The server generates its own private random number (rand_s) and performs the same operation to calculate dh_Ys:

dh_grand_s mod dh_p = dh_Ys -

The dh_Yc and dh_Ys public values are openly communicated.

-

The client calculates the premaster secret using dh_Ys and rand_c:

dh_Ysrand_c mod dh_p = secret -

The server performs the same operation using dh_Yc and rand_s:

dh_Ycrand_s mod dh_p = secret

Note

When using DH in a static mode, dh_g, dh_p, dh_Ys, and rand_s are fixed and do not provide forward secrecy.

The premaster secret is consistent between the two parties, as the sum values of steps 2 and 3 are raised again by using each party’s private random number, resulting in the same total. So long as dh_p is sufficiently long (over 1,024 bits), performing brute-force to compromise the secret is prohibitively expensive.

Upon calculating the premaster secret, each party generates a master secret and key block (as demonstrated by Figures 11-4 and 11-5).

To recap, a basic demonstration of the mathematics is as follows:

-

The server selects a dh_g value (3) and a dh_p value (17), and sends to the client.

-

The client selects a rand_c value of 15 and generates dh_Yc:

315 mod 17 = 6 -

The server selects a rand_s value of 13 and generates dh_Ys:

313 mod 17 = 12 -

The public dh_Yc and dh_Ys values (6 and 12) are distributed.

-

The client performs:

1215 mod 17 = 10 -

The server performs:

1013 mod 17 = 10

DH parameter selection and negotiation

The server unilaterally defines domain parameters for a session, and so weak values can be presented to a client. For example, dh_p is supposed to be a large prime number, but many clients accept small primes (and even values that are not prime), resulting in weak session security. A cross-protocol attack can also be launched to serve signed ECDH parameters to a client, which are misinterpreted as plain DH parameters.13

Support for custom DH parameter groups is slated for removal in TLS 1.3.

ECC

ECC versions of both DH and DSA are defined by RFC 4492 and summarized by Table 11-2. ECC is attractive because it uses small private key sizes and is fast.

| Cipher suite | Key type | Transmitted via |

|---|---|---|

ECDH_ECDSA |

Static | Server certificate (ECDSA signed) |

ECDH_RSA |

Server certificate (RSA signed) | |

ECDHE_ECDSA |

Ephemeral | Server Key Exchange message (ECDSA signed) |

ECDHE_RSA |

Server Key Exchange message (RSA signed) | |

ECDH_anon |

Server Key Exchange message (unsigned) |

The server defines a named curve during handshake, referring to a published curve and set of parameters. Armed with parameters, each party uses a private key to produce a public value, which is communicated and used to independently generate a premaster secret. Some curves are unsafe and should be avoided, as described by Daniel J. Bernstein and Tanja Lange’s SafeCurves project.14

TLS Authentication

Systems including TLS use X.509 certificates to authenticate clients, servers, and users. Operating systems and web browsers contain the public keys of trusted certificate authorities (CAs), which are used to sign individual certificates.

X.509 format

Table 11-3 lists X.509 fields. These attributes communicate certificate validity, the identity of an entity (i.e., host or user name), and associated public key. The signature algorithm and signature value extensions are used to sign the certificate by a given authority (known as the issuer).

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Version | Defines the X.509 version |

| Serial number | A unique identifier for each certificate from a given issuer |

| Signature | The algorithm used to sign the certificate |

| Issuer | Identifies the entity that has signed the certificate |

| Validity | Defines the validity period for the certificate |

| Subject | Identifies the entity associated with the public key |

| Subject public key | Used to describe the subject’s public key and corresponding algorithm (i.e., RSA, DSA, or DH) |

| Unique identifiers | The issuer and subject identifiers |

| Extensions | Extensions allowing for particular policies to be set and data communicated (e.g., the signature algorithm and CA public key values used) |

During testing, use the OpenSSL command-line utility in s_client15 and x509 modes to retrieve and process X.509 certificates, as demonstrated by Examples 11-2 and 11-3. The output reveals both certificate fields and extensions.

Example 11-2. Obtaining and processing an X.509 certificate

root@kali:~# openssl s_client -connect www.google.com:443 CONNECTED(00000003) depth=2 /C=US/O=GeoTrust Inc./CN=GeoTrust Global CA verify error:num=20:unable to get local issuer certificate verify return:0 --- Certificate chain 0 s:/C=US/ST=California/L=Mountain View/O=Google Inc/CN=www.google.com i:/C=US/O=Google Inc/CN=Google Internet Authority G2 1 s:/C=US/O=Google Inc/CN=Google Internet Authority G2 i:/C=US/O=GeoTrust Inc./CN=GeoTrust Global CA 2 s:/C=US/O=GeoTrust Inc./CN=GeoTrust Global CA i:/C=US/O=Equifax/OU=Equifax Secure Certificate Authority --- Server certificate -----BEGIN CERTIFICATE----- MIIEdjCCA16gAwIBAgIIK9dUvsPWSlUwDQYJKoZIhvcNAQEFBQAwSTELMAkGA1UE BhMCVVMxEzARBgNVBAoTCkdvb2dsZSBJbmMxJTAjBgNVBAMTHEdvb2dsZSBJbnRl cm5ldCBBdXRob3JpdHkgRzIwHhcNMTQxMDA4MTIwNzU3WhcNMTUwMTA2MDAwMDAw WjBoMQswCQYDVQQGEwJVUzETMBEGA1UECAwKQ2FsaWZvcm5pYTEWMBQGA1UEBwwN TW91bnRhaW4gVmlldzETMBEGA1UECgwKR29vZ2xlIEluYzEXMBUGA1UEAwwOd3d3 Lmdvb2dsZS5jb20wggEiMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBAQUAA4IBDwAwggEKAoIBAQCcKeLr plAC+Lofy8t/wDwtB6eu72CVp0cJ4V3lknN6huH9ct6FFk70oRIh/VBNBBz900jY y+7111Jm1b8iqOTQ9aT5C7SEhNcQFJvqzH3eMPkb6ZSWGm1yGF7MCQTGQXF20Sk/ O16FSjAynU/b3oJmOctcycWYkY0ytS/k3LBuId45PJaoMqjB0WypqvNeJHC3q5Jj CB4RP7Nfx5jjHSrCMhw8lUMW4EaDxjaR9KDhPLgjsk+LDIySRSRDaCQGhEOWLJZV LzLo4N6/UlctCHEllpBUSvEOyFga52qroGjgrf3WOQ925MFwzd6AK+Ich0gDRg8s QfdLH5OuP1cfLfU1AgMBAAGjggFBMIIBPTAdBgNVHSUEFjAUBggrBgEFBQcDAQYI KwYBBQUHAwIwGQYDVR0RBBIwEIIOd3d3Lmdvb2dsZS5jb20waAYIKwYBBQUHAQEE XDBaMCsGCCsGAQUFBzAChh9odHRwOi8vcGtpLmdvb2dsZS5jb20vR0lBRzIuY3J0 MCsGCCsGAQUFBzABhh9odHRwOi8vY2xpZW50czEuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS9vY3NwMB0G A1UdDgQWBBQ7a+CcxsZByOpc+xpYFcIbnUMZhTAMBgNVHRMBAf8EAjAAMB8GA1Ud IwQYMBaAFErdBhYbvPZotXb1gba7Yhq6WoEvMBcGA1UdIAQQMA4wDAYKKwYBBAHW eQIFATAwBgNVHR8EKTAnMCWgI6Ahhh9odHRwOi8vcGtpLmdvb2dsZS5jb20vR0lB RzIuY3JsMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBBQUAA4IBAQCaOXCBdoqUy5bxyq+Wrh1zsyyCFim1 PH5VU2+yvDSWrgDY8ibRGJmfff3r4Lud5kaldKs9k8YlKD3ITG7P0YT/Rk8hLgfE uLcq5cc0xqmE42xJ+Eo2uzq9rYorc5emMCxf5L0TJOXZqHQpOEcuptZQ4OjdYMfS xk5UzueUhA3ogZKRcRkdB3WeWRp+nYRhx4Sto2rt2A0MKmY9165GHUqMK9YaaXHD XqBu7Sefr1uSoAP9gyIJKeihMivsGqJ1TD6Zcc6LMe+dN2P8cZEQHtD1y296ul4M ivqk3jatUVL8/hCwgch9A8O4PGZq9WqBfEWmIyHh1dPtbg1lOXdYCWtj -----END CERTIFICATE-----

Example 11-3. Extracting the X.509 fields from the certificate

root@kali:~# openssl x509 -text -noout

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----

MIIEdjCCA16gAwIBAgIIK9dUvsPWSlUwDQYJKoZIhvcNAQEFBQAwSTELMAkGA1UE

BhMCVVMxEzARBgNVBAoTCkdvb2dsZSBJbmMxJTAjBgNVBAMTHEdvb2dsZSBJbnRl

cm5ldCBBdXRob3JpdHkgRzIwHhcNMTQxMDA4MTIwNzU3WhcNMTUwMTA2MDAwMDAw

WjBoMQswCQYDVQQGEwJVUzETMBEGA1UECAwKQ2FsaWZvcm5pYTEWMBQGA1UEBwwN

TW91bnRhaW4gVmlldzETMBEGA1UECgwKR29vZ2xlIEluYzEXMBUGA1UEAwwOd3d3

Lmdvb2dsZS5jb20wggEiMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBAQUAA4IBDwAwggEKAoIBAQCcKeLr

plAC+Lofy8t/wDwtB6eu72CVp0cJ4V3lknN6huH9ct6FFk70oRIh/VBNBBz900jY

y+7111Jm1b8iqOTQ9aT5C7SEhNcQFJvqzH3eMPkb6ZSWGm1yGF7MCQTGQXF20Sk/

O16FSjAynU/b3oJmOctcycWYkY0ytS/k3LBuId45PJaoMqjB0WypqvNeJHC3q5Jj

CB4RP7Nfx5jjHSrCMhw8lUMW4EaDxjaR9KDhPLgjsk+LDIySRSRDaCQGhEOWLJZV

LzLo4N6/UlctCHEllpBUSvEOyFga52qroGjgrf3WOQ925MFwzd6AK+Ich0gDRg8s

QfdLH5OuP1cfLfU1AgMBAAGjggFBMIIBPTAdBgNVHSUEFjAUBggrBgEFBQcDAQYI

KwYBBQUHAwIwGQYDVR0RBBIwEIIOd3d3Lmdvb2dsZS5jb20waAYIKwYBBQUHAQEE

XDBaMCsGCCsGAQUFBzAChh9odHRwOi8vcGtpLmdvb2dsZS5jb20vR0lBRzIuY3J0

MCsGCCsGAQUFBzABhh9odHRwOi8vY2xpZW50czEuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS9vY3NwMB0G

A1UdDgQWBBQ7a+CcxsZByOpc+xpYFcIbnUMZhTAMBgNVHRMBAf8EAjAAMB8GA1Ud

IwQYMBaAFErdBhYbvPZotXb1gba7Yhq6WoEvMBcGA1UdIAQQMA4wDAYKKwYBBAHW

eQIFATAwBgNVHR8EKTAnMCWgI6Ahhh9odHRwOi8vcGtpLmdvb2dsZS5jb20vR0lB

RzIuY3JsMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBBQUAA4IBAQCaOXCBdoqUy5bxyq+Wrh1zsyyCFim1

PH5VU2+yvDSWrgDY8ibRGJmfff3r4Lud5kaldKs9k8YlKD3ITG7P0YT/Rk8hLgfE

uLcq5cc0xqmE42xJ+Eo2uzq9rYorc5emMCxf5L0TJOXZqHQpOEcuptZQ4OjdYMfS

xk5UzueUhA3ogZKRcRkdB3WeWRp+nYRhx4Sto2rt2A0MKmY9165GHUqMK9YaaXHD

XqBu7Sefr1uSoAP9gyIJKeihMivsGqJ1TD6Zcc6LMe+dN2P8cZEQHtD1y296ul4M

ivqk3jatUVL8/hCwgch9A8O4PGZq9WqBfEWmIyHh1dPtbg1lOXdYCWtj

-----END CERTIFICATE-----

Certificate:

Data:

Version: 3 (0x2)

Serial Number:

2b:d7:54:be:c3:d6:4a:55

Signature Algorithm: sha1WithRSAEncryption

Issuer: C=US, O=Google Inc, CN=Google Internet Authority G2

Validity

Not Before: Oct 8 12:07:57 2014 GMT

Not After : Jan 6 00:00:00 2015 GMT

Subject: C=US, ST=California, L=Mountain View, O=Google Inc, CN=www.google.com

Subject Public Key Info:

Public Key Algorithm: rsaEncryption

RSA Public Key: (2048 bit)

Modulus (2048 bit):

00:9c:29:e2:eb:a6:50:02:f8:ba:1f:cb:cb:7f:c0:

3c:2d:07:a7:ae:ef:60:95:a7:47:09:e1:5d:e5:92:

73:7a:86:e1:fd:72:de:85:16:4e:f4:a1:12:21:fd:

50:4d:04:1c:fd:d3:48:d8:cb:ee:f5:d7:52:66:d5:

bf:22:a8:e4:d0:f5:a4:f9:0b:b4:84:84:d7:10:14:

9b:ea:cc:7d:de:30:f9:1b:e9:94:96:1a:6d:72:18:

5e:cc:09:04:c6:41:71:76:d1:29:3f:3b:5e:85:4a:

30:32:9d:4f:db:de:82:66:39:cb:5c:c9:c5:98:91:

8d:32:b5:2f:e4:dc:b0:6e:21:de:39:3c:96:a8:32:

a8:c1:d1:6c:a9:aa:f3:5e:24:70:b7:ab:92:63:08:

1e:11:3f:b3:5f:c7:98:e3:1d:2a:c2:32:1c:3c:95:

43:16:e0:46:83:c6:36:91:f4:a0:e1:3c:b8:23:b2:

4f:8b:0c:8c:92:45:24:43:68:24:06:84:43:96:2c:

96:55:2f:32:e8:e0:de:bf:52:57:2d:08:71:25:96:

90:54:4a:f1:0e:c8:58:1a:e7:6a:ab:a0:68:e0:ad:

fd:d6:39:0f:76:e4:c1:70:cd:de:80:2b:e2:1c:87:

48:03:46:0f:2c:41:f7:4b:1f:93:ae:3f:57:1f:2d:

f5:35

Exponent: 65537 (0x10001)

X509v3 extensions:

X509v3 Extended Key Usage:

TLS Web Server Authentication, TLS Web Client Authentication

X509v3 Subject Alternative Name:

DNS:www.google.com

Authority Information Access:

CA Issuers - URI:http://pki.google.com/GIAG2.crt

OCSP - URI:http://clients1.google.com/ocsp

X509v3 Subject Key Identifier:

3B:6B:E0:9C:C6:C6:41:C8:EA:5C:FB:1A:58:15:C2:1B:9D:43:19:85

X509v3 Basic Constraints: critical

CA:FALSE

X509v3 Authority Key Identifier:

keyid:4A:DD:06:16:1B:BC:F6:68:B5:76:F5:81:B6:BB:62:1A:BA:5A:81:2F

X509v3 Certificate Policies:

Policy: 1.3.6.1.4.1.11129.2.5.1

X509v3 CRL Distribution Points:

URI:http://pki.google.com/GIAG2.crl

Signature Algorithm: sha1WithRSAEncryption

9a:39:70:81:76:8a:94:cb:96:f1:ca:af:96:ae:1d:73:b3:2c:

82:16:29:b5:3c:7e:55:53:6f:b2:bc:34:96:ae:00:d8:f2:26:

d1:18:99:9f:7d:fd:eb:e0:bb:9d:e6:46:a5:74:ab:3d:93:c6:

25:28:3d:c8:4c:6e:cf:d1:84:ff:46:4f:21:2e:07:c4:b8:b7:

2a:e5:c7:34:c6:a9:84:e3:6c:49:f8:4a:36:bb:3a:bd:ad:8a:

2b:73:97:a6:30:2c:5f:e4:bd:13:24:e5:d9:a8:74:29:38:47:

2e:a6:d6:50:e0:e8:dd:60:c7:d2:c6:4e:54:ce:e7:94:84:0d:

e8:81:92:91:71:19:1d:07:75:9e:59:1a:7e:9d:84:61:c7:84:

ad:a3:6a:ed:d8:0d:0c:2a:66:3d:d7:ae:46:1d:4a:8c:2b:d6:

1a:69:71:c3:5e:a0:6e:ed:27:9f:af:5b:92:a0:03:fd:83:22:

09:29:e8:a1:32:2b:ec:1a:a2:75:4c:3e:99:71:ce:8b:31:ef:

9d:37:63:fc:71:91:10:1e:d0:f5:cb:6f:7a:ba:5e:0c:8a:fa:

a4:de:36:ad:51:52:fc:fe:10:b0:81:c8:7d:03:c3:b8:3c:66:

6a:f5:6a:81:7c:45:a6:23:21:e1:d5:d3:ed:6e:0d:65:39:77:

58:09:6b:63

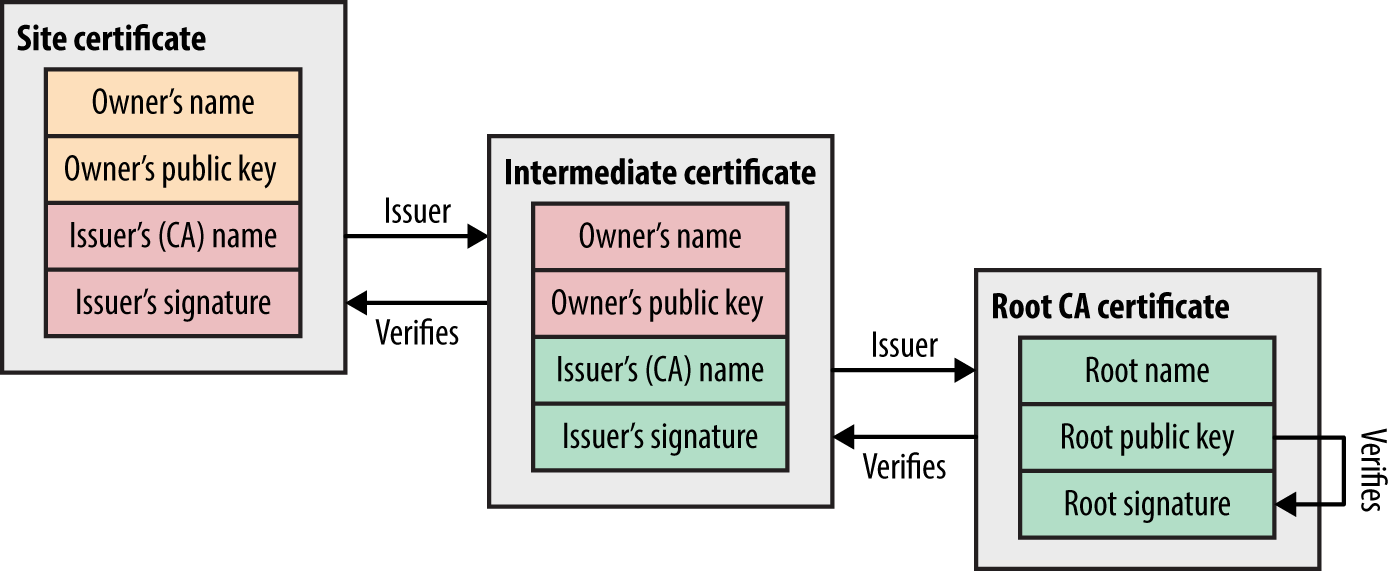

CAs and chaining

TLS peers commonly authenticate each other through verification of issuer and signature values within X.509 certificates. CAs sign certificates by using their private keys, and corresponding public keys are distributed within both operating systems and browsers as trusted root certificates.

Within X.509, the CA flag is used to specify whether a certificate can be used to sign others (CA:true) or not (CA:false). Certificate chains are formed by using this flag—root CAs sign the certificates of subordinate CAs (known as intermediate CAs), which in turn can sign others.

Many root and intermediate CAs exist. Between them, the EFF identified more than 650 organizations that can sign X.509 certificates, which are trusted by Microsoft and Mozilla.16

The chain of the Google certificate from Example 11-2 is as follows:

0 s:/C=US/ST=California/L=Mountain View/O=Google Inc/CN=www.google.com i:/C=US/O=Google Inc/CN=Google Internet Authority G2 1 s:/C=US/O=Google Inc/CN=Google Internet Authority G2 i:/C=US/O=GeoTrust Inc./CN=GeoTrust Global CA 2 s:/C=US/O=GeoTrust Inc./CN=GeoTrust Global CA i:/C=US/O=Equifax/OU=Equifax Secure Certificate Authority

Equifax is a root authority, which in turn signed the GeoTrust subordinate certificate that was used to sign Google’s subordinate certificate, and finally the X.509 certificate of www.google.com. Equifax’s certificate is found in Microsoft Windows as a trusted root. Figure 11-6 demonstrates such a chain.

Figure 11-6. An X.509 certificate chain

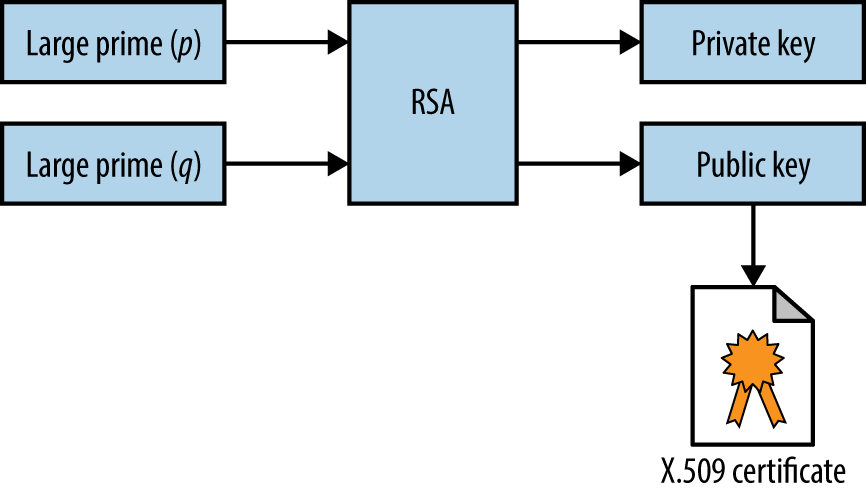

Key generation and handling

Figure 11-7 demonstrates RSA key pair generation. Two large prime numbers are chosen at random, which are fed into the RSA algorithm to calculate the private and public keys. The public value is placed in the X.509 certificate, which is then signed by a CA.

Figure 11-7. X.509 RSA key generation

The private key and materials used to generate it (i.e., the random primes) must be generated and handled in a secure fashion. For example, a 2008 PRNG defect in Debian Linux resulted in private keys generated using OpenSSL being predictable.17,18 Private keys should not be left in user home directories, version control (e.g., GitHub), or exposed via world-readable permissions.

Signature algorithm flaws

Mechanisms used to sign X.509 certificates are listed in Table 11-4. Microsoft, Google,19 and other organizations are phasing-out SHA-1, and MD5 is completely broken (as exploited by the Flame malware20).

| Hash function | Signed using | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| MD5 | RSA | Broken and easily exploiteda |

| SHA-1 | RSA, DSA, or ECDSA | Weak but no known collisions |

| SHA-256 | Practically secure at the time of writing | |

| SHA-384 | ||

| SHA-512 | ||

a Nat McHugh, “How I Created Two Images with the Same MD5 Hash”, Nat McHugh Blog, October 31, 2014. | ||

Session Resumption

Resuming a TLS session by undertaking a full handshake is computationally expensive. As such, servers support resumption modes that remove a full round-trip:

- TLS resumption

- If peers have previously negotiated a master secret, an abbreviated handshake can be used to resume the TLS session. The Client Hello contains a session ID that, if recognized by the server with a corresponding master secret, can be used. A revised key block is generated (as per Figure 11-5), as the random values are new.

- TLS session ticket extension

- Maintaining state server-side presents challenges in large environments, and so a mechanism by which session identifiers are stored by the client (encrypted using the server’s private key) was ratified as a TLS extension.23 The resumption mechanism works in the same way as before, but the client maintains state. In practice, deploying the extension across load-balanced TLS endpoints requires some careful thinking: all servers must be initialized with a shared private key, and an additional mechanism might be required to periodically rotate it.

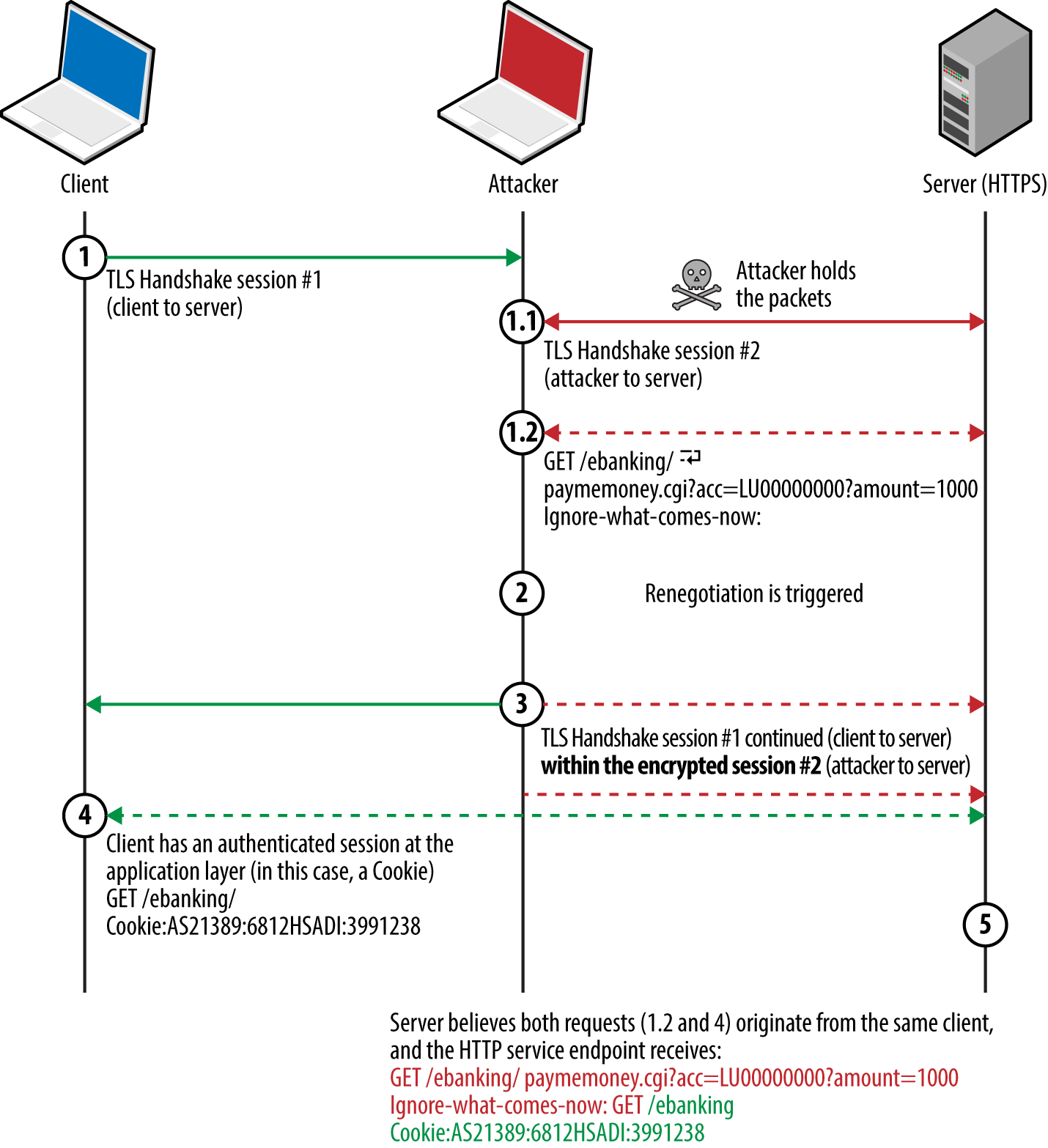

Session Renegotiation

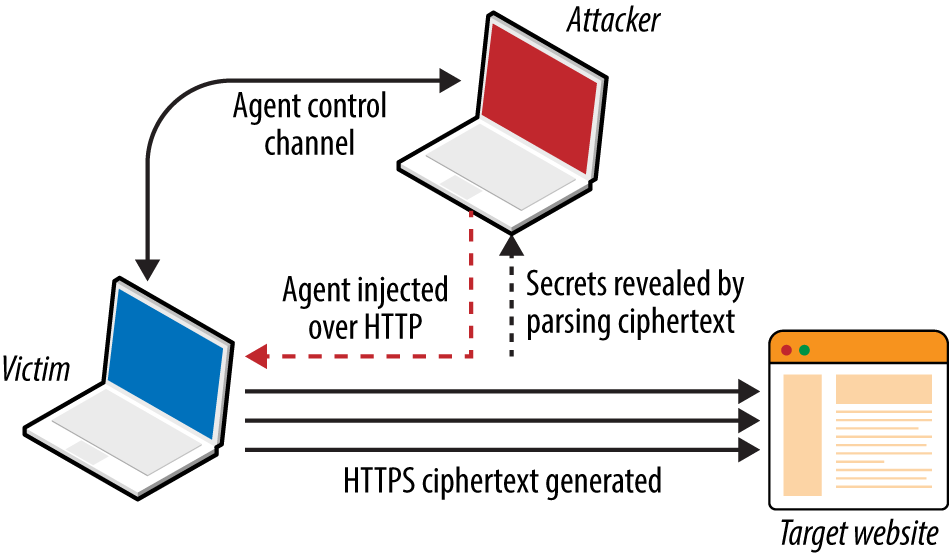

A TLS session can be renegotiated over an existing secure channel to rekey or perform further authentication. A flaw was discovered in the mechanism,24 by which an adversary with network access could intercept and hold handshake records from a legitimate client, establish a TLS session itself with a server, send application data, initiate renegotiation, and release the legitimate handshake records. As renegotiation is performed over an existing channel, the server believes the session is one and the same. Data from both the client and attacker is then accepted, as shown in Figure 11-8.

Figure 11-8. HTTPS injection via insecure renegotiation

Thierry Zoller published a paper describing this issue and practical attack vectors.25 In summary, he identified flaws that lead to arbitrary HTTP request injection, downgrade from HTTPS to HTTP, and presentation of malicious content to the client via the TRACE method.

A TLS extension was introduced to resolve the issue by cryptographically tying renegotiation to an existing session.26 Popular TLS libraries have since implemented the extension and support secure renegotiation.

Compression

TLS 1.2 and prior support compression via DEFLATE.27 When compression is applied to blocks containing HTTP headers (which have a known structure and format), session tokens can be revealed by observing the compressed ciphertext. The CRIME attack targets compression within TLS itself, whereas BREACH and TIME attacks exploit HTTP compression (regardless of the transport layer) to reveal secrets in HTTP responses.

STARTTLS

The STARTTLS command is used to establish a TLS session over a plaintext protocol (e.g., SMTP, IMAP, POP3, or FTP), as demonstrated by Example 11-4 over SMTP.28 A TLS session is negotiated upon acknowledging the STARTTLS instruction, involving exchange of records as before.

Example 11-4. Initiating a TLS session over SMTP

root@kali:~# telnet mail.imc.org 25 Trying 207.182.41.81... Connected to mail.imc.org. Escape character is '^]'. 220 proper.com ESMTP Sendmail 8.14.9/8.14.7; Wed, 29 Oct 2014 09:03:59 EHLO world 250-proper.com Hello wifi-nat.bl.uk (may be forged), pleased to meet you 250-ENHANCEDSTATUSCODES 250-PIPELINING 250-EXPN 250-VERB 250-8BITMIME 250-SIZE 250-DSN 250-ETRN 250-AUTH DIGEST-MD5 CRAM-MD5 LOGIN 250-STARTTLS 250-DELIVERBY 250 HELP STARTTLS 220 2.0.0 Ready to start TLS

Note

Differences often exist in the features supported over plaintext and encrypted service channels. For example, authentication mechanisms can differ (or be nonexistent through a plaintext session), which can be attacked via brute-force password grinding.

Understanding TLS Vulnerabilities

Attackers can exploit some TLS flaws remotely (e.g., memory corruption within the implementation), but practical exploitation of many requires network access to compromise ciphertext and inject application data.

Since 2011, Juliano Rizzo, Thai Duong, and others have identified a number of flaws within SSL and TLS, with monikers including BEAST, CRIME, BREACH, and POODLE. Exploitation of these vulnerabilities often requires the following:

-

The victim browser to execute a malicious agent (e.g., JavaScript)

-

Network access to monitor the ciphertext generated by the victim

-

A communication channel to the agent to modify the plaintext

Figure 11-9 demonstrates the arrangement, showing the attacker, victim, and target site. The JavaScript agent is injected within a plaintext HTTP session (to any site) and used to generate ciphertext that is measured to obtain secrets in known locations (e.g., session tokens within HTTP headers sent to the server).

Figure 11-9. Exploiting TLS flaws with network access

At the time of writing, there are two exceptions that should be noted:

-

Practical exploitation of timing side channels within TLS server implementations (e.g., Lucky 13, as discussed later) often requires network proximity or low-latency access to the TLS server so that accurate metrics can be gathered.

-

If ciphertext capture is not required (e.g., TIME), attacks can be launched remotely

Exploitable Flaws

Defects affecting SSL and TLS fall into two categories:

-

Protocol weaknesses (e.g., SSL 3.0, TLS 1.0, or HTTP compression)

-

Vulnerabilities within particular implementations (e.g., OpenSSL 1.0.1g)

Here, I detail significant vulnerabilities in older protocols, including SSL 3.0 and TLS 1.0, along with severe implementation defects (e.g., the OpenSSL heartbleed flaw).

SSL and TLS protocol weaknesses

Many flaws within SSL, TLS, and associated mechanisms have been publicized. Below is a list of individual vulnerabilities, including CVE identifiers, plus a brief description of the impact, attack vector, and notes regarding practicality.

- DROWN (CVE-2016-0800)29

- An SSL 2.0 padding oracle attack resulting in RSA private key exposure.

- Logjam (CVE-2015-4000)30

- Systems supporting DHE and group sizes less than 1,024 bits are vulnerable to MITM, by which a weak group is forced, and encryption attacked to reveal plaintext content.

- POODLE (CVE-2014-3566)31

- SSL 3.0 using CBC mode ciphers is vulnerable to a padding oracle attack. Exploitation requires network access, along with JavaScript run by the victim browser to generate traffic (performing a chosen-plaintext and chosen-boundary attack). A padding oracle within the CBC decryption mechanism is used to reveal a secret (e.g., session token) byte-by-byte upon modifying plaintext via the JavaScript agent.

- BEAST (CVE-2011-3389)32

- TLS 1.0 generates predictable IV values when using CBC mode ciphers. It is possible to deduce secrets through undertaking a blockwise chosen-boundary attack upon injecting an agent (e.g., Java applet) into a victim’s browser and monitoring the ciphertext.

- CRIME (CVE-2012-4929)

- Servers running TLS 1.2 and prior that support compression are vulnerable to attack via CRIME. Practical exploitation requires network access, along with JavaScript run by the victim browser to generate ciphertext (performing a chosen-plaintext and chosen-location attack). A side channel introduced by the server compression mechanism is monitored, revealing a secret (e.g., session token) byte-by-byte upon modifying the plaintext.

- BREACH (CVE-2013-3587)33

- Web applications that use HTTP compression and reflect static secrets (e.g., session tokens) to clients via HTML can be targeted through BREACH. As with CRIME, the attack relies upon a JavaScript agent to generate traffic and undertake a chosen-plaintext attack through monitoring response lengths to infer each byte of a secret.

- TIME34

- TIME targets HTTP compression but does not require network access to exploit. After malicious JavaScript is injected into a browser, an adversary can deduce secrets (e.g., session token values) byte-by-byte through monitoring responses to chosen-plaintext values used in particular locations. A timing side channel is used upon aligning HTTP responses to an MTU boundary.

- RC4 byte biases (CVE-2013-2566)35

- The RC4 algorithm has many byte biases, which an adversary can use to recover plaintext bytes at known locations (such as a session token within a cookie) upon encrypting the same plaintext many times and monitoring the ciphertext. The attack requires generation of extremely large data volumes. Thus it is somewhat impractical but highlights a significant flaw within RC4.

- Insecure renegotiation (CVE-2009-3555)

- As demonstrated by Figure 11-8, TLS endpoints might support insecure renegotiation, making it possible for an attacker with network access to prefix legitimate session traffic from a client to server with his own (e.g., a malicious HTTP request). Depending on the configuration of the application, this can result in HTTPS to HTTP downgrade or malicious commands being processed.

- Insecure fallback

- Outdated clients support insecure fallback, which an attacker with network access can exploit to downgrade a session to TLS 1.0 or SSL 3.0. The IETF resolved the issue by introducing a new cipher suite (

TLS_FALLBACK_SCSV),36 which prevents downgrade of TLS implementations that support the cipher.

TLS implementation flaws

Table 11-5 lists significant exploitable flaws in TLS and DTLS libraries. Many certificate validation and denial of service flaws exist but are not listed here for brevity’s sake. Attack vectors also vary—some bugs are exploitable remotely, whereas others require network access.

| CVE reference(s) | Affects (up to) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CVE-2016-2108 | OpenSSL 1.0.2b and 1.0.1n | ASN.1 encoder memory corruption resulting in potential code execution |

| CVE-2016-2107 | OpenSSL 1.0.2 to 1.0.2g OpenSSL 1.0.1e to 1.0.1s |

Padding oracle relating to AES CBC mode ciphers leading to private key exposure |

| CVE-2016-0703 | OpenSSL 1.0.2, 1.0.1l, 1.0.0q, and 0.9.8ze | Severe RSA private key recovery flaw when supporting SSL 2.0a |

| CVE-2016-0702 | OpenSSL 1.0.2f, NSS 3.21, and LibreSSL 2.3.1 and prior | RSA private key recovery via cache timing side channel attack against Intel Sandy Bridge processorsb |

| CVE-2016-0701 | OpenSSL 1.0.2 to 1.0.2e | DH key recovery flawc |

| CVE-2015-7575 | Multiple implementations including OpenSSL 1.0.1e and GnuTLS 3.3.14 | Vulnerable implementations support MD5 and SHA-1 signatures over TLS 1.2, resulting in MITM through peer impersonationd |

| CVE-2015-3197 | OpenSSL 1.0.2 to 1.0.2e OpenSSL 1.0.1 to 1.0.1q |

Clients can force the negotiation of SSL 2.0 connections, leading to further attacks (e.g., DROWN key recovery and MITM) |

CVE-2015-0204 CVE-2015-1067 CVE-2015-1637 |

OpenSSL, Microsoft SChannel, Apple Secure Transport, and others | Export-grade cipher downgrade attack known as FREAK,e resulting in MITM |

| CVE-2014-3512 | OpenSSL 1.0.1h and prior | SRP cipher suite overflow with unknown impact and consequences |

| CVE-2014-3511 | OpenSSL 1.0.1h and prior cause the server to negotiate with TLS 1.0 instead of a higher protocol when a Client Hello message is badly fragmented | |

| CVE-2014-3466 | GnuTLS 3.3.3 and prior | Buffer overflow via Server Hello with a long session ID value |

| CVE-2014-0160 | OpenSSL 1.0.1 to 1.0.1f | Information leak flaw known as heartbleed—upon receiving a crafted TLS heartbeat request, a vulnerable peer leaks up sensitive heap content |

| CVE-2013-0169 | OpenSSL 1.0.1d and prior | CBC mode side channel resulting in recovery of plaintext bytes at known locations (known as Lucky 13) |

| CVE-2011-4108 | OpenSSL 1.0.0e and prior | DTLS flaw allowing attackers to recover plaintext upon taking advantage of a padding oracle when CBC mode ciphers are used |

a Nimrod Aviram et al., “DROWN: Breaking TLS using SSLv2”, proceedings of the 25th USENIX Security Symposium, Vancouver, Canada, August 16–18, 2016. b Yuval Yarom, Daniel Genkin, and Nadia Heninger, “CacheBleed: A Timing Attack on OpenSSL Constant Time RSA”, presented at the Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems – CHES 2016 Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, August 17–19, 2016. c Antonio Sanso, “OpenSSL Key Recovery Attack on DH Small Subgroups (CVE-2016-0701)”, Into the Symmetry Blog, January 28, 2016. d Karthikeyan Bhargavan and Gaetan Leurent, “Security Losses from Obsolete and Truncated Transcript Hashes (CVE-2015-7575)”, miTLS.org. e Censys Team, “The FREAK Attack”, Censys.io, March 3, 2015. | ||

Mitigating TLS Exposures

Table 11-6 lists mitigation steps for the TLS vulnerabilities discussed. Many issues (including CRIME, BREACH, and POODLE) have also been mitigated within Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox.

| Attack(s) | Mitigation |

|---|---|

| Logjam | Enforce DH group sizes of 1,024 bits and above |

| POODLE | Disable support for SSL 3.0 |

| BEAST | Enforce TLS 1.1 and higher |

| CRIME | Disable TLS compression |

| BREACH and TIME | Disable HTTP compression |

| Lucky 13 | Disable CBC ciphers if your server implementation is flawed |

| RC4 byte biases | Disable support for RC4 cipher suites |

| FREAK | Disable support for weak export-grade ciphers |

Insecure renegotiation Insecure fallback DH parameter tampering Implementation flaws |

Upgrade both server and client software to current |

Lucky 13 and RC4 byte bias mitigation within web applications

Published attacks against TLS tend to focus on credential exposure (e.g., HTTP session tokens and passwords sent from the client to server). Attacks practically rely on a JavaScript agent being run within the client browser to generate requests over TLS.

In the case of Lucky 13 and RC4 byte bias attacks, HTTP headers (including the session token) are sent to the server many times. Attacks including POODLE and BEAST use a chosen-boundary37 and calculate plaintext values byte-by-byte, which requires far less traffic.

The Lucky 13 attack uses around 524,000 (219) connections to recover a base64 encoded session token, and the RC4 byte bias attack requires in excess of 16.7 million (224) to recover plaintext bytes at particular locations.

An effective mitigation strategy that you can adopt within web applications is to invalidate session tokens that are presented a large number of times by a client within a given period (e.g., 7,200 requests/hour). Upon exceeding the threshold, the server invalidates the token and the user must reauthenticate.

In high-assurance environments, a second threshold should be considered to lock the user account (e.g., 86,400 requests within a 24-hour period). The Lucky 13 attack requires days and careful orchestration to undertake, and an RC4 byte bias attack takes months. By locking accounts before then, you can practically negate the risk.

Note

Client certificates provide an additional layer of protection from reuse of compromised credentials (e.g., passwords and session tokens), and are recommended to provide defense in depth.

Assessing TLS Endpoints

You can identify potential vulnerabilities within a TLS service by doing the following:

-

Identifying the TLS library and version

-

Enumerating supported protocols and cipher suites

-

Enumerating supported features and extensions

-

Reviewing the server certificate

And, upon fingerprinting the service and reviewing its configuration:

-

Manually qualifying known vulnerabilities

-

Evaluating the stability of the TLS service

Here I describe these steps and detail individual testing tactics.

Identifying the TLS Library and Version

You can use OS fingerprinting and banner grabbing to identify the TLS library used by a server (along with the version in some cases). Richard Moore’s TLS Prober utility38 provides useful insight, as demonstrated by Example 11-5. In this case, the closest match for www.google.com is OpenSSL 1.0.1k. Table 11-7 lists common TLS libraries and operating platforms.

Example 11-5. Installing and executing TLS Prober

root@kali:~# git clone https://github.com/WestpointLtd/tls_prober.git root@kali:~# cd tls_prober/ && git submodule update --init root@kali:~/tls_prober# ./prober.py www.google.com OpenSSL 1.0.1k Debian 8 Apache 21 FortiOS v5.2.2,build642 (GA) 21 openssl-1.0.1h default source build 20 openssl-1.0.1g default source build 19 OpenSSL 1.0.1f Debian 7 nginx 19 openssl-1.0.1b default source build 18 openssl-1.0.0m default source build 18 openssl-1.0.1a default source build 18

| Library | Used by |

|---|---|

| OpenSSL | Apache (via mod_ssl) and many platforms including Linux |

| NSS | Apache (via mod_nss) and Oracle Solaris enterprise products |

| GnuTLS | Apache (via mod_gnutls), Linux, Windows, and others |

| Microsoft SChannel | Microsoft operating systems and products |

| Apple Secure Transport | Apple OS X and iOS |

| TLS Lite | Python applications |

| Oracle JSSE | Java applications and frameworks including Spring MVC |

| Bouncy Castle | Java and C# applications |

Apache banners often reveal the OS and TLS library, as demonstrated here:

Server: Apache/2.2.8 (Win32) mod_ssl/2.2.8 OpenSSL/0.9.8g Server: Apache/2.2.22 (Debian) mod_gnutls/0.5.10 PHP/5.4.4-14+deb7u4 Server: Apache/2.4.10 (Fedora) mod_nss/2.4.6 NSS/3.15.2 Basic ECC PHP/5.5.18

Be careful not to confuse module and library versions. In this case, the version of the GnuTLS library is unknown, and the version of the mod_nss module (2.4.6) does not correspond with the underlying library (NSS 3.15.2).

Enumerating Supported Protocols and Cipher Suites

You can use the Nmap ssl-enum-ciphers script to list the supported protocols and cipher suites for a given TLS endpoint, as shown in Example 11-6. In this case, weak 40-bit ciphers are supported by the server across SSL 3.0, TLS 1.0, 1.1, and 1.2. Many of the other configurations reported as strong by Nmap in the example are in fact weak, as detailed later.

Example 11-6. Using Nmap ssl-enum-ciphers

root@kali:~# nmap --script ssl-enum-ciphers -p443 www.163.com Starting Nmap 6.46 (http://nmap.org) at 2014-10-27 20:15 UTC Nmap scan report for www.163.com (8.37.230.14) PORT STATE SERVICE 443/tcp open https | ssl-enum-ciphers: | SSLv3: | ciphers: | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_DES40_CBC_SHA - weak | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC2_CBC_40_MD5 - weak | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC4_40_MD5 - weak | TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_CAMELLIA_128_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_CAMELLIA_256_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_IDEA_CBC_SHA - weak | TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_MD5 - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_SEED_CBC_SHA - strong | TLSv1.0: | ciphers: | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_DES40_CBC_SHA - weak | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC2_CBC_40_MD5 - weak | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC4_40_MD5 - weak | TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_CAMELLIA_128_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_CAMELLIA_256_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_IDEA_CBC_SHA - weak | TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_MD5 - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_SEED_CBC_SHA - strong | TLSv1.1: | ciphers: | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_DES40_CBC_SHA - weak | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC2_CBC_40_MD5 - weak | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC4_40_MD5 - weak | TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_CAMELLIA_128_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_CAMELLIA_256_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_IDEA_CBC_SHA - weak | TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_MD5 - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_SEED_CBC_SHA - strong | TLSv1.2: | ciphers: | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_DES40_CBC_SHA - weak | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC2_CBC_40_MD5 - weak | TLS_RSA_EXPORT_WITH_RC4_40_MD5 - weak | TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256 - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA256 - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384 - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_CAMELLIA_128_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_CAMELLIA_256_CBC_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_IDEA_CBC_SHA - weak | TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_MD5 - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_SHA - strong | TLS_RSA_WITH_SEED_CBC_SHA - strong

Note

Nmap 6.46 does not support protocol and cipher enumeration via STARTTLS; however, this is due to be resolved from version 7. In the meantime, the SSLyze39 within Kali Linux performs limited testing of TLS implementations operating in this manner.

Weak cipher suites

Appendix C details weak cipher suites. The following list summarizes them:

- Anonymous DH suites

- Static DH running in an anonymous mode (i.e.,

DH_anonorECDH_anon) lacks authentication and impersonation attacks are possible via MITM. - Suites using null ciphers

- Most null cipher suites (e.g.,

TLS_RSA_WITH_NULL_SHA) perform key exchange and authentication but send material in plaintext. - Export-grade suites

- Cipher suites deemed as export-grade use bulk symmetric encryption algorithms with 40- and 56-bit keys. Data is encrypted, but the short key length permits decryption via brute-force.

- Suites with weak encryption algorithms

- DES, 3DES, IDEA, RC2, and RC4 ciphers used to provide bulk symmetric encryption have known weaknesses. Although byte bias attacks against RC4 are practically cumbersome to undertake (requiring generation of large volumes of data), Microsoft and others are removing RC4 support from their products.40

Upon compiling a list of weak cipher suite and protocol combinations, investigating the configuration of a given TLS endpoint is relatively straightforward. In Example 11-4 we find that www.163.com supports weak cipher suites across SSL 3.0, TLS 1.0, 1.1, and 1.2.

The server supports no GCM ciphers, and so an adversary with network access can compromise HTTPS sessions by undertaking the following attacks:

-

Brute-force of keys used by export-grade DES, RC2, and RC4 suites

-

POODLE against CBC mode ciphers within SSL 3.0

-

BEAST against CBC mode ciphers via TLS 1.0 (implementation dependent)41

-

Byte biases in RC4 ciphers across all SSL and TLS protocol versions

A Lucky 13 attack can also be considered if the server implementation is vulnerable and the attacker has low-latency access to the TLS server endpoint (to gather high fidelity timing data).

Preferred cipher suite order

A patch to the Nmap ssl-enum-ciphers script published by Bojan Zdrnja42 returns a list of ciphers for each supported protocol along with their preference (ordered favorite first). Example 11-7 demonstrates the script downloaded via wget within Kali Linux and executed against www.google.com (output stripped for brevity).

Example 11-7. Listing the preferred order of TLS ciphers by using Nmap

root@kali:~# wget http://bit.ly/2ervajI 2014-11-01 13:11:36 (868 KB/s) - `ssl-enum-ciphers.nse' saved [16441/16441] root@kali:~# nmap --script ssl-enum-ciphers.nse -p443 www.google.com Starting Nmap 6.46 (http://nmap.org) at 2014-11-01 13:11 UTC Nmap scan report for www.google.com (74.125.230.244) PORT STATE SERVICE 443/tcp open https | ssl-enum-ciphers: | SSLv3: | preferred ciphers order: | TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_SHA | TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA | TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_SHA | TLS_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_MD5 | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA | TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA | TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA | TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA | TLS_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA

The order of preference is critical because flawed RC4 and CBC mode ciphers should not be chosen over secure alternatives. Authenticated GCM ciphers (e.g., AES-GCM) available within TLS are resilient if implemented correctly, and should be preferred.

Note

Within the examples in this chapter, I use hostnames (www.google.com, www.163.com, and others). During testing, however, you should use specific IP addresses and run tests multiple times to account for load balancing across multiple backend components.

Enumerating Supported Features and Extensions

Support of TLS features and extensions is enumerated through review of server responses to requests sent by using Nmap, the OpenSSL command-line utility, and SSLyze, as detailed across the following sections.

Session resumption

TLS endpoints support resumption via session IDs or RFC 5077 tickets. Handshake flooding can result in denial of service; thus, many TLS servers limit the number of session IDs cached for a particular source. Example 11-8 demonstrates SSLyze used to test resumption support of www.163.com and www.ibm.com.

Example 11-8. Testing TLS session resumption support using SSLyze

root@kali:~# sslyze --resum www.163.com:443

SCAN RESULTS FOR WWW.163.COM:443 - 8.37.230.18:443

--------------------------------------------------

* Session Resumption :

With Session IDs: Partially supported (2 successful, 3 failed,

0 errors, 5 total attempts). Try --resum_rate.

With TLS Session Tickets: Not Supported - TLS ticket assigned but

not accepted.

root@kali:~# sslyze --resum www.ibm.com:443

SCAN RESULTS FOR WWW.IBM.COM:443 - 23.6.131.48:443

--------------------------------------------------

* Session Resumption :

With Session IDs: Supported (5 successful, 0 failed, 0 errors, 5 total attempts).

With TLS Session Tickets: Supported

Session renegotiation

You can also use SSLyze to test for secure and client-initiated renegotiation support. Example 11-9 demonstrates the tool used to test for renegotiation of the HTTPS service at www.ibm.com and the SMTP endpoint of aspmx.l.google.com via STARTTLS.

Example 11-9. TLS renegotiation testing via SSLyze

root@kali:~# sslyze --reneg www.ibm.com:443

SCAN RESULTS FOR WWW.IBM.COM:443 - 23.6.131.48:443

--------------------------------------------------

* Session Renegotiation :

Client-initiated Renegotiations: Honored

Secure Renegotiation: Supported

root@kali:~# sslyze --reneg --starttls=smtp aspmx.l.google.com:25

SCAN RESULTS FOR ASPMX.L.GOOGLE.COM:25 - 74.125.71.26:25

--------------------------------------------------------

* Session Renegotiation :

Client-initiated Renegotiations: Rejected

Secure Renegotiation: Supported

Listing supported TLS extensions

Along with session tickets, secure renegotiation, and the TLS heartbeat protocol, the server might support other notable TLS extensions. Example 11-10 demonstrates using the OpenSSL command-line utility to list TLS extensions used by www.google.com and www.openssl.org (output stripped for brevity).

Example 11-10. Enumerating supported TLS extensions

root@kali:~# openssl s_client -tlsextdebug -connect www.google.com:443 CONNECTED(00000003) TLS server extension "renegotiation info" (id=65281), len=1 TLS server extension "EC point formats" (id=11), len=4 TLS server extension "session ticket" (id=35), len=0 root@kali:~# openssl s_client -tlsextdebug -connect www.openssl.org:443 CONNECTED(00000003) TLS server extension "renegotiation info" (id=65281), len=1 TLS server extension "session ticket" (id=35), len=0 TLS server extension "heartbeat" (id=15), len=1

Compression support

Example 11-11 demonstrates testing for TLS compression support with SSLyze.

Example 11-11. Enumerating TLS compression support

root@kali:~# sslyze --compression www.google.com:443

SCAN RESULTS FOR WWW.GOOGLE.COM:443 - 74.125.230.84:443

-------------------------------------------------------

* Compression :

Compression Support: Disabled

Fallback support

Upon updating the OpenSSL package within Kali Linux (e.g., apt-get install openssl), use the -fallback_scsv flag within the OpenSSL command-line utility to identify services that permit session downgrade and TLS fallback. Example 11-12 shows an insecure configuration, as OpenSSL closes the connection upon providing an inappropriate fallback alert.

Example 11-12. TLS fallback support testing

root@kali:~# openssl s_client -connect www.example.com:443 -no_tls1_2 -fallback_scsv CONNECTED(00000003) 140735242785632:error:1407743E:SSL routines:SSL23_GET_SERVER_HELLO:tlsv1 alert inappropriate fallback:s23_clnt.c:770: --- no peer certificate available --- No client certificate CA names sent --- SSL handshake has read 7 bytes and written 218 bytes --- New, (NONE), Cipher is (NONE) Secure Renegotiation IS NOT supported Compression: NONE Expansion: NONE

Certificate Review

Example 11-3 demonstrated the way by which an X.509 certificate block is parsed using openssl x509 -text -noout from the command line. During scanning, Nmap can reveal certificate information via the ssl-cert script, as shown in Example 11-13.

Example 11-13. Basic TLS querying with Nmap

root@kali:~# nmap -p443 --script ssl-cert www.google.com Starting Nmap 6.46 (http://nmap.org) at 2014-11-24 23:56 UTC Nmap scan report for www.google.com (74.125.230.240) PORT STATE SERVICE 443/tcp open https | ssl-cert: Subject: commonName=www.google.com/organizationName=Google Inc | /stateOrProvinceName=California/countryName=US | Issuer: commonName=Google Internet Authority G2/organizationName=Google Inc | /countryName=US | Public Key type: rsa | Public Key bits: 2048 | Not valid before: 2014-11-05T12:22:42+00:00 | Not valid after: 2015-02-03T00:00:00+00:00 | MD5: 934a 1716 b92f f666 00ec e157 8f46 9d70 |_SHA-1: a989 3c56 048b 0f2c 846c 4106 9273 5a92 e98e 17ad

Upon reviewing the certificate block, ensure the following:

-

The X.509 subject common name (CN) is correct for the service43

-

The issuer is reputable and certificate chain valid

-

RSA or DSA public key values are longer than 2,048 bits

-

DH public parameters are longer than 2,048 bits

-

The certificate is valid and has not expired

-

The certificate is signed using SHA-256

X.509 certificates with known private keys

Craig Heffner’s Little Black Box44 contains more than 2,000 certificates with known private keys (primarily devices manufactured by Cisco, Linksys, D-Link, Polycom, and others). Nmap has integrated checking functionality using the ssl-known-key script, which cross-references hashes of certificates with the database, as demonstrated by Example 11-14.

Example 11-14. Using Nmap to identify endpoints with known keys

root@kali:~# nmap -p443 --script ssl-known-key 192.168.0.15 Starting Nmap 6.46 (http://nmap.org) at 2014-12-01 17:18 UTC Nmap scan report for 192.168.0.15 PORT STATE SERVICE 443/tcp open https |_ssl-known-key: Found in Little Black Box 0.1 (SHA-1: 0028 e7d4 9cfa 4aa5 984f e497 eb73 4856 0787 e496)

Certificates generated insecurely

If the values used during key generation lack entropy (e.g., there is a flaw within the PRNG implementation), multiple certificates might share primes, which can be attacked.45 Research revealed that the RSA private keys of 2.5 percent of the TLS endpoints online could be compromised.

Stress Testing TLS Endpoints

The thc-ssl-dos utility46 within Kali Linux performs stress testing of TLS endpoints via concurrent handshakes and client-initiated renegotiation requests (if supported by a server). A second utility is sslsqueeze,47 which is more potent and does not rely on renegotiation to flood the TLS endpoint.

Performing cryptographic operations during a TLS handshake consumes a large number of CPU cycles on the server when compared to the client. Depending on the configuration, the work factor can be as high as 25 (as discussed by Vincent Bernat48). If exhausted, servers become unable to process TLS traffic and other processes can be affected.

Usage of the thc-ssl-dos tool is as follows:

______________ ___ _________

\__ ___/ | \ \_ ___ \

| | / ~ \/ \ \/

| | \ Y /\ \____

|____| \___|_ / \______ /

\/ \/

http://www.thc.org

Twitter @hackerschoice

./thc-ssl-dos [options] <ip> <port>

-h help

-l <n> Limit parallel connections [default: 400]

For optimal results, consider performing the test from a high-bandwidth system (e.g., one in colocation) with ample processing power. Laptop CPU and upstream broadband bandwidth will limit the efficacy of the attack.

Sukalp Bholpe’s thesis discusses TLS availability issues and countermeasures.49 He describes attacks using both thc-ssl-dos and sslsqueeze, including analysis of system load.

Mitigation strategies that limit the impact of flooding include the following:

-

Disabling support for client-initiated session renegotiation

-

Use of the TLS session ticket extension to minimize server-side state tracking

-

Terminating TLS using dedicated acceleration hardware to reduce server load

-

Configuring endpoints to limit the number of TLS handshakes per source

Manually Accessing TLS-Wrapped Services

You can use Stunnel to interact with services wrapped using TLS. Example 11-15 shows a simple stunnel.conf file that establishes a TLS connection to secure.example.com on TCP port 443, and listens for plaintext traffic on port 80 of the local host. Upon creating this configuration file in the same directory as the executable, simply run Stunnel and connect to TCP port 80 of 127.0.0.1.

Example 11-15. A basic stunnel.conf entry

client=yes verify=0 [psuedo-https] accept = 80 connect = secure.example.com:443 TIMEOUTclose = 0

Stunnel supports features including STARTTLS and client certificates, as described by its manual page.50 You also can use the OpenSSL command-line utility in s_client mode to establish a secure channel via STARTTLS over POP3, as follows:

root@kali:~# openssl s_client -starttls pop3 -connect mail.example.org:110 +OK POP3 mail.example.org v2003.83 server ready QUIT +OK Sayonara

TLS Service Assessment Recap

What follows is a recap of the testing steps described in this chapter:

- Identify the TLS library and version

- Through OS and network service fingerprinting, along with review of available Apache HTTP Server banners, attempt to identify the TLS library and version (or at least discount libraries that are not in use). Also consider the release date of other packages running on the server (e.g., SMTP or FTP software) to narrow-down particular TLS library candidates.

- Enumerate supported protocols and cipher suites

- Use the Nmap ssl-enum-ciphers script to list supported protocols and ciphers. Subsequent versions of the script (within Nmap 7 and beyond) should also support

STARTTLS, and sort cipher suites by server preference. - List supported extensions and features

- Identify TLS extensions (e.g., support for secure renegotiation, session tickets, and ECC) by using the OpenSSL command-line utility, Nmap, and SSLyze within Kali Linux.

- Review the server’s X.509 certificate

- Ensure that RSA and DSA public key sizes, along with the signing algorithm used, are not weak. Also review extensions, certificate validity, and whether a reputable issuer has signed the certificate.

- Manually qualify vulnerabilities

- Cross-reference the TLS library (and version if available) with supported protocols, cipher suites, features, and extensions. Build a list of qualified protocol and implementation flaws to understand the applicable risks.

- Stress-test TLS endpoints

- Use the thc-ssl-dos utility to perform stress testing if the service supports client-initiated renegotiation. If not, use sslsqueeze to assess robustness.

TLS Hardening

You should consider the following steps when hardening TLS endpoints:

-

Upgrade software to current to mitigate known implementation flaws

-

Disable support for SSL 3.0 to mitigate POODLE

-

Disable weak encryption algorithms (i.e., RC2, RC4, IDEA, 3DES, and DES)

-

If available, prioritize the following cipher suites:

-

Those using ECDHE for key exchange (enabling forward secrecy)

-

Authenticated GCM ciphers for bulk encryption (e.g., AES-GCM)

-

-

Disable support for TLS compression to mitigate CRIME

-

Disable support for client-initiated renegotiation

-

Enforce minimum key lengths:

-

2,048-bit for RSA and other asymmetric modes (e.g., DSA)

-

2,048-bit for DH parameters

-

256-bit for ECC modes (i.e., ECDHE and ECDSA)

-

256-bit for hash functions (e.g., SHA-256, and others)

-

-

Review http://bit.ly/2aQuKB6 to mitigate DH weaknesses

-

Avoid using large key sizes if availability is important (e.g., 4,096-bit keys used within RSA for key exchange have a significant server processing overhead)

-

Ensure that private keys are generated, handled, and stored in a secure fashion (e.g., not world-readable or left in a home directory, version control, or unencrypted backup)

-

Use a reputable CA to sign your certificates using SHA-256

Web Application Hardening

Consider the following when hardening web applications with HTTPS components:

-

Serving the entire application and assets over HTTPS

-

Using HSTS to enforce transport security for the application51

-

Disabling HTTP compression for sessions where the Referer field doesn’t contain the name of the current site

-

Rate-limiting requests containing security tokens (i.e., session tokens and CSRF tokens) that are presented a large number of times by a client, then invalidating the session, or locking the user account for a period of time

-

Limiting reflection of user-supplied tokens or secrets in HTTP responses

1 You can also check out Ivan Ristić’s blog.

6 See “Transport Layer Security (TLS) Extensions” at IANA.org.

7 See “Transport Layer Security (TLS) Parameters” at IANA.org.

8 See “Authenticated encryption” on Wikipedia.

10 See “TLS-PSK” on Wikipedia.

11 Vincent Bernat, “SSL Computational DoS Mitigation”, MTU Ninja Blog, November 1, 2011.

12 See “Modular arithmetic” on Wikipedia.

13 Nikos Mavrogiannopoulos et al., “A Cross-Protocol Attack on the TLS Protocol”, proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Raleigh, NC, August 16–18, 2012.

14 Daniel J. Bernstein and Tanja Lange, “SafeCurves: Choosing Safe Curves for Elliptic-Curve Cryptography”, December 1, 2014.

15 See the OpenSLL s_client documentation.

16 See “The EFF SSL Observatory”, Electronic Frontier Foundation.

17 Bruce Schneier, “Random Number Bug in Debian Linux”, Schneier on Security, May 19, 2008.

18 See CVE-2008-0166.

19 Chris Palmer and Ryan Sleevi, “Gradually Sunsetting SHA-1”, Google Security Blog, September 5, 2014.

20 Alex Sotirov, “Analyzing the MD5 Collision in Flame”, Trail of Bits Blog, June 11, 2012.

21 Bruce Schneier, “When Will We See Collisions for SHA-1?”, Schneier on Security, October 5, 2012.

22 Marc Stevens, “Project HashClash”, Marc-Stevens.nl.

24 See CVE-2009-3555.

25 Thierry Zoller, “TLS/SSLv3 Renegotiation Vulnerability Explained”, SlideShare.net, February 6, 2013.

29 See https://drownattack.com.

30 David Adrian et al., “Weak Diffie-Hellman and the Logjam Attack”, WeakDH.org.

31 Bodo Möller, Thai Duong, and Krzysztof Kotowicz “The Poodle Bites: Exploiting the SSL 3.0 Fallback”, Google Security Advisory, September 2014.

32 Thai Duong and Juliano Rizzo, “Here Come the ⊕ Ninjas”, unpublished, May 13, 2011.

33 Angelo Prado, Neal Harris, and Yoel Gluck, “SSL, Gone in 30 Seconds”, BreachAttack.com.

34 Tal Be’ery and Amichai Shulman, “A Perfect CRIME? Only TIME Will Tell” presented at Black Hat Europe 2013, Amsterdam, Netherlands, March 12–15, 2013.

35 Kenny Paterson et al., “On the Security of RC4 in TLS and WPA”, Information Security Group, March 13, 2013.

36 B. Moeller and A. Langley, “TLS Fallback Signaling Cipher Suite Value (SCSV) for Preventing Protocol Downgrade Attacks”, IETF.org, February 11, 2015.

37 Erland Oftedal, “The Chosen-Boundary Attack”, Insomnia and the Hole in the Universe Blog.

38 See TLS Prober on GitHub.

39 See SSLyze on GitHub.

40 swiat, “Security Advisory 2868725: Recommendation to Disable RC4”, Microsoft TechNet Blog, November 12, 2013.

41 Ivan Ristić, “Is BEAST Still a Threat?”, Qualys Blog, September 10, 2013.

42 See ssl-enum-ciphers.nse on GitHub.

43 The RFC 5280 subjectAltName extension may also list hostnames.

44 See Little Black Box on the Google Code Archive.

45 Nadia Heninger et al., “Mining Your Ps and Qs: Detection of Widespread Weak Keys in Network Devices”, proceedings of the 21st USENIX Security Symposium, Bellevue, WA, August 10–12, 2012.

46 See thc-ssl-dos on THC.org.

47 See sslsqueeze on Stunnel.

48 Vincent Bernat, “SSL/TLS & Perfect Forward Secrecy”, MTU Ninja Blog, November 28, 2011.

49 Sukalp Bhople, “Server-Based DoS Vulnerabilities in SSL/TLS Protocols”, master’s thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, Netherlands, August 2012.