Chapter 2. Assessment Workflow and Tools

This chapter outlines my penetration testing approach and describes an effective testing setup. Many assessment tools run on Linux platforms, and Windows-specific utilities are required when attacking Microsoft systems. A flexible, virtualized platform is key. At Matta, we ran a program called Sentinel, through which we evaluated third-party testing vendors for clients in the financial services sector. Each vendor was ranked based on the vulnerabilities identified within the systems we had prepared. In a single test involving 10 vendors, we found that:

-

Two failed to scan all 65,536 TCP ports

-

Five failed to report the MySQL service root password of “password”

Some were evaluated multiple times. There seemed to be a lack of adherence to a strict testing methodology, and test results (the final report) varied depending on the consultants involved.

During testing, it is important to remember that there is an entire methodology that you should be following. Engineers and consultants often venture down proverbial rabbit holes, and neglect key areas of the environment.

By the same token, it is also important to quickly identify significant vulnerabilities within a network. As such, this methodology bears two hallmarks:

-

Comprehensiveness, so that you can consistently identify significant flaws

-

Flexibility, so that you can prioritize your efforts and maximize return

Network Security Assessment Methodology

The best practice assessment methodology used by determined attackers and security consultants involves four distinct steps:

-

Reconnaissance to identify networks, hosts, and users of interest

-

Vulnerability scanning to identify potentially exploitable conditions

-

Investigation of vulnerabilities and further probing by hand

-

Exploitation of vulnerabilities and circumvention of security mechanisms

This methodology is relevant to the testing of Internet networks in a blind fashion with limited target information (such as a domain name). If a consultant is enlisted to assess a specific block of IP space, she can skip network enumeration and commence bulk network scanning and investigation of vulnerabilities.

Local network testing involves assessment of nonroutable protocols and OSI Layer 2 features (e.g., 802.1X and 802.1Q). You can use VLAN hopping and network sniffing to compromise data and systems, as detailed in Chapter 5.

Reconnaissance

You can adopt different tactics to identify hosts, networks, and users of interest. Attackers map the target environment by using open sources (e.g., web search engines, WHOIS databases, and DNS servers) without direct network interaction through port scanning.

Reconnaissance often uncovers hosts that aren’t properly fortified. Determined attackers invest time in identifying peripheral networks and hosts, whereas organizations often concentrate their efforts on securing obvious public systems (such as public web and mail servers). Neglected hosts lying off the beaten track are ripe for the picking.

Useful pieces of information gathered through reconnaissance include details of Internet-based network blocks and internal IP addresses. Through DNS and WHOIS querying, you can map the networks of a target organization, and understand relationships between physical locations.

This information is fed into the vulnerability scanning and penetration testing phases to identify exploitable flaws. Further reconnaissance involves extracting user details (e.g., email addresses, telephone numbers, and usernames) that can be used during brute-force password grinding and social engineering phases.

Vulnerability Scanning

Upon identifying IP blocks of interest, attackers carry out bulk scanning to identify accessible network services that can later be exploited to achieve particular goals—be it code execution, information leak, or denial of service. Network scanning tools (e.g., Nmap, Nessus, Rapid7 Nexpose, and QualysGuard) perform service fingerprinting, probing, and testing for known issues.

Useful information gathered through vulnerability scanning includes details of exposed network services and peripheral information (such as the ICMP messages to which hosts respond, and insight into firewall ACLs). Known weaknesses and exposures are also reported by scanning tools, which you can then investigate further.

Investigation of Vulnerabilities

Vulnerabilities in software are sometimes disclosed through public Internet mailing lists and forums, but are increasingly sold to private organizations, such as the Zero Day Initiative (ZDI), which in turn responsibly disclose issues to vendors and notify paying subscribers. According to Immunity Inc., on average, a zero-day bug has a lifespan of 348 days before a vendor patch is made available.

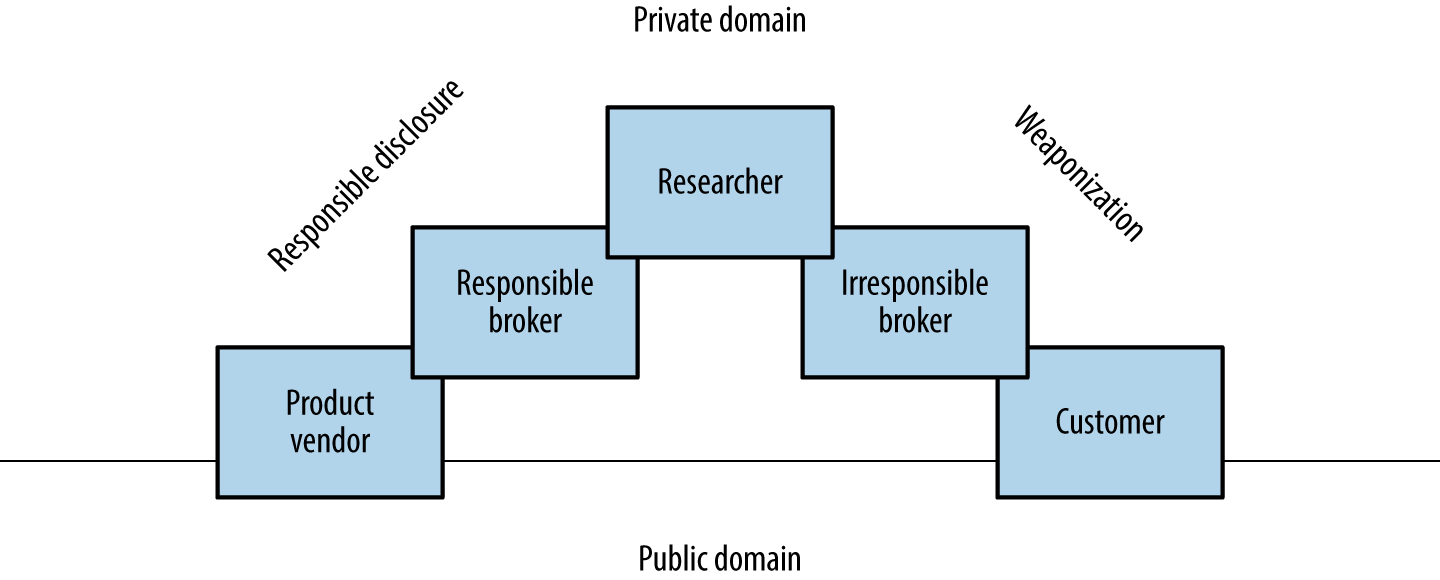

Many brokers do not notify product vendors of vulnerabilities, and some provide commercially supported zero-day exploits to their customers. Between responsible disclosure, zero-day abuse, and the public discussion of known flaws, vulnerability details are fragmented, as depicted by Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1. Common proliferation paths for vulnerability details

To effectively report vulnerabilities within an environment, a security professional would need to know the bugs within both private and public domains. Many do not have access to private feeds, and base their assessment on public knowledge, augmented by their own research.

Public vulnerability sources

The following open sources are useful when investigating potential vulnerabilities:

ZDI and Google’s Project Zero operate publicly accessible bug trackers that detail upcoming disclosures and unpatched vulnerabilities.1 Open projects including OpenSSL and the Linux kernel also have public bug trackers that reveal useful details of unpatched flaws. During testing, it is worth reviewing both bug trackers and release notes to understand known weaknesses within software packages.

Private vulnerability sources

Many government agencies and defense industrial base entities consume private vulnerability information via brokers and sources including ZERODIUM, Exodus Intelligence, Netragard, and ReVuln. These organizations are known to provide details of unpatched bugs to subscribers.

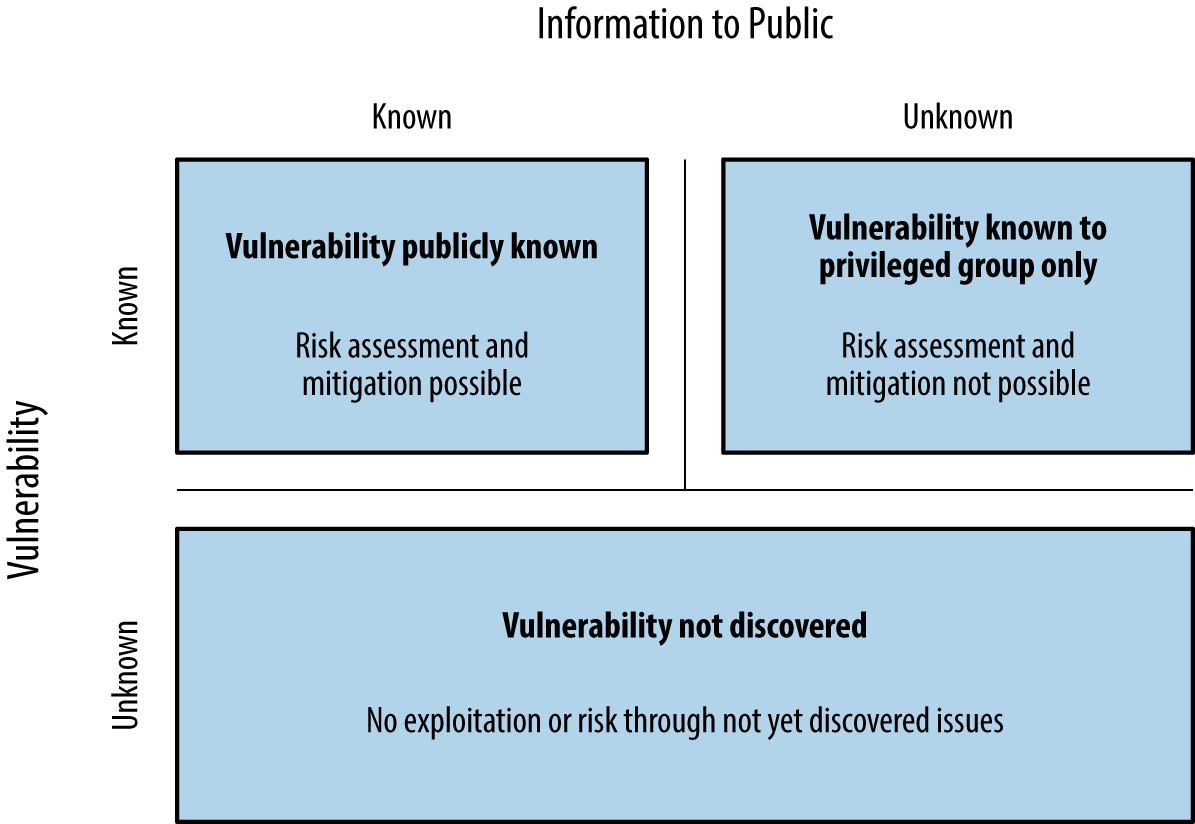

Stefan Frei of NSS Labs published a paper on this topic.2 Within his paper, Frei discussed vulnerabilities known to a privileged group, as demonstrated in Figure 2-2.

Based on disclosures regarding the US government’s budget for zero-day exploit purchases, Frei estimated that at least 85 known unknowns exist on any given day. Depending on the policy of each party involved, these bugs might never be disclosed to the vendor.

Vlad Tsyrklevich’s “Hacking Team: A Zero-Day Market Case Study” provides insight into the private market for vulnerability information, including prices of exploits and details of unpatched flaws in packages including Abode Flash, Microsoft Office, Internet Explorer, and Oracle Database.

Figure 2-2. Vulnerability discovery and disclosure matrix

Exploitation of Vulnerabilities

Attackers can exploit flaws in exposed logic for gain. Depending on their goals, they might take advantage of vulnerabilities to secure privileged network access, persistence, or obtain sensitive information.

During a penetration test, qualification of vulnerabilities usually involves exploitation. Robust commercially supported frameworks provide flexible targeting of vulnerable components within a given environment (supporting different operating systems and configurations), which allows you to define specific exploit payloads. Modules developed by third parties extend these frameworks, providing support for Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition (SCADA) and other technologies. Popular exploitation frameworks are as follows:

Within NIST SP 800-115, exploitation tasks fall under the category of Target Vulnerability Validation Techniques. As a tester (with correct authorization) you might undertake password cracking and social engineering, and qualify vulnerabilities through use of exploitation frameworks and tools.

An Iterative Assessment Approach

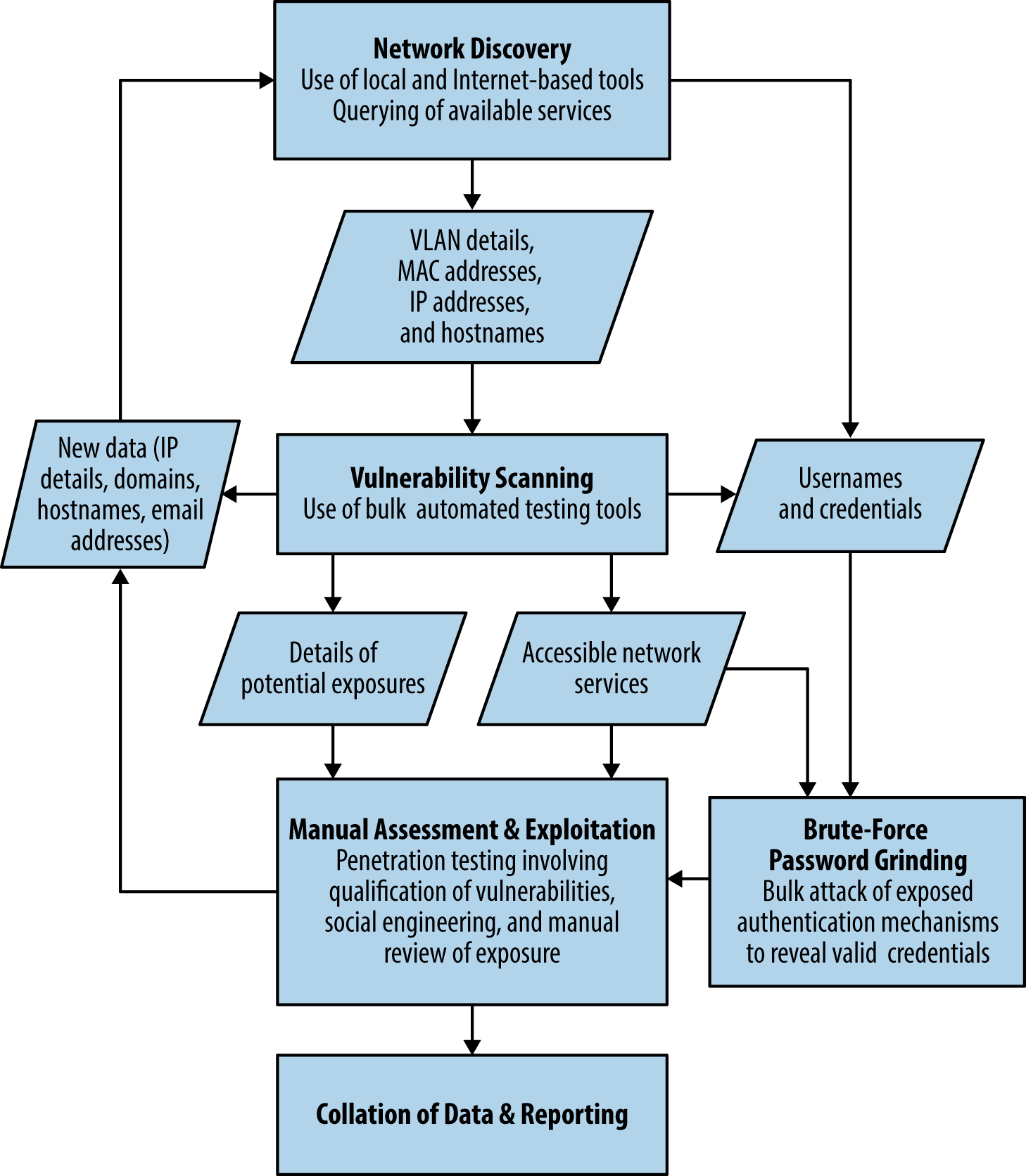

The assessment process is iterative, and new details (e.g., IP address blocks, hostnames, and credentials) are often fed back to earlier workflow elements. Figure 2-3 describes the process and data passed between individual testing elements.

Figure 2-3. An iterative approach to discovery and testing

Your Testing Platform

To support both Linux and Windows-based testing tools, it is best to use virtualization software (e.g., VMware Fusion for Apple OS X or VMware Workstation for Windows). Useful native applications within Linux include showmount, dig, and snmpwalk. You also can build specific utilities to attack uncommon network protocols and applications.

Kali Linux is a penetration testing distribution that you can run easily within a virtualized environment. Kali contains many of the utilities found within this book, including Metasploit, Nmap, Burp Suite, and Nikto. The Kali Linux documentation details installation, and two recently published books describe individual tools, as follows:

-

Kali Linux: Assuring Security by Penetration Testing, by Tedi Heriyanto, Lee Allen, and Shakeel Ali (Packt Publishing, 2014)

-

Mastering Kali Linux for Advanced Penetration Testing, by Robert W. Beggs (Packt Publishing, 2014)

If you use Apple OS X for instance, running Microsoft Windows and Kali Linux within VMware Fusion will be sufficient for most engagements. Offensive Security maintains custom Kali Linux VMware and ARM images, which support VMware Tools (which make it possible for you to copy and paste between the virtualized guest and your host system), and ARM platforms such as the Chromebook.

Deploying a Vulnerable Server

To test utilities in a controlled environment, use a vulnerable server image to ensure that each tool is working correctly. Rapid7 prepared a virtual machine image known as Metasploitable 2,3 which can be compromised through many vectors, including:

-

Backdoors within packages including FTP and IRC

-

Vulnerable Unix RPC services

-

SMB privilege escalation

-

Weak user passwords

-

Web application server issues (via Apache HTTP Server and Tomcat)

-

Web application vulnerabilities (e.g., phpMyAdmin and TWiki)

Tutorials and walkthroughs are available online that describe the utilities, Metasploit modules, and commands that can be used to evaluate and exploit flaws within the virtual machine. Here are two useful resources:

-

Computer Security Student (navigate to Security Tools→Metasploitable Project→Exploits)

You can find many other exploitable virtual machine images online at VulnHub. For the purposes of web application testing, take a look at the OWASP vulnerable web applications directory and PentesterLab in particular.

1 See Zero Day Initiative’s upcoming advisories and Chromium bugs, respectively.

2 Stefan Frei, “The Known Unknowns & Outbidding Cybercriminals”, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, September 2014.

3 For more information, see the Metasploitable 2 Exploitability Guide.