Third Edition

Know Your Network

Copyright © 2017 Chris McNab. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

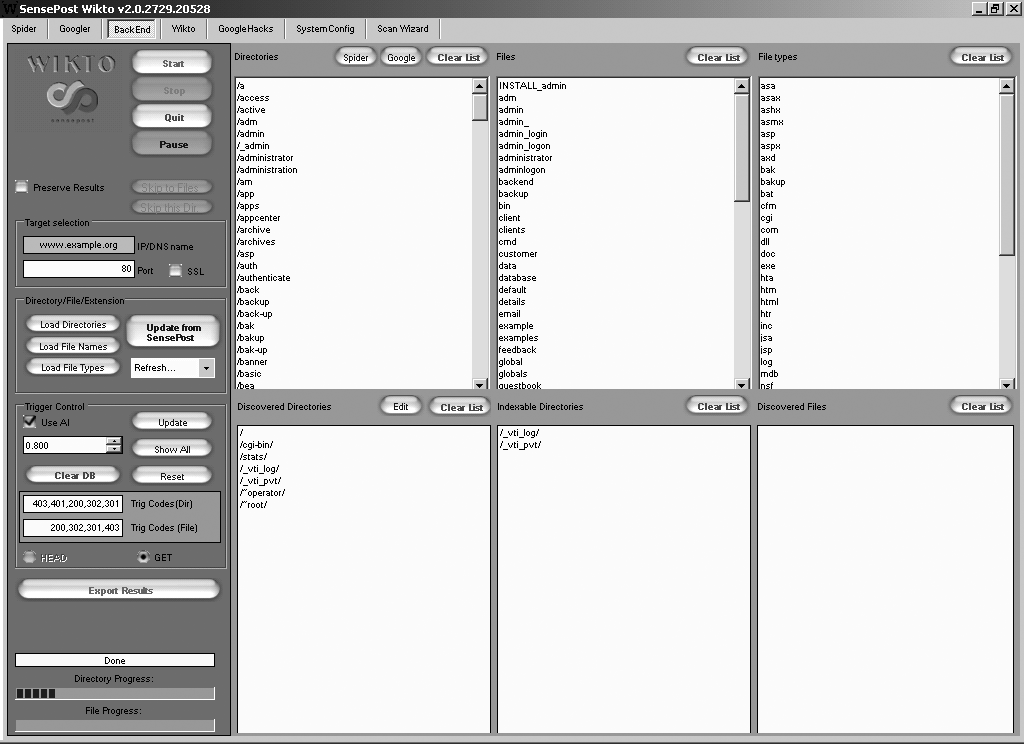

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari.). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781491910955 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Network Security Assessment, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

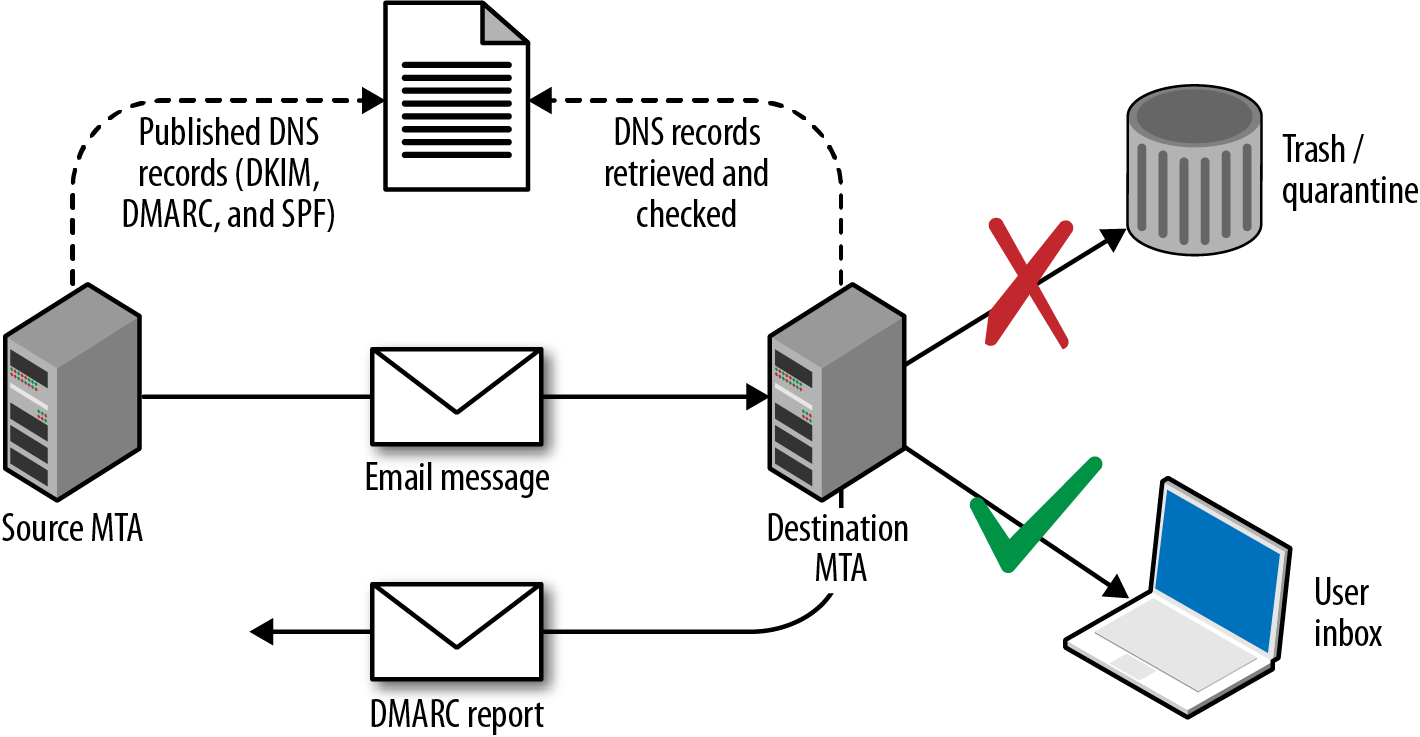

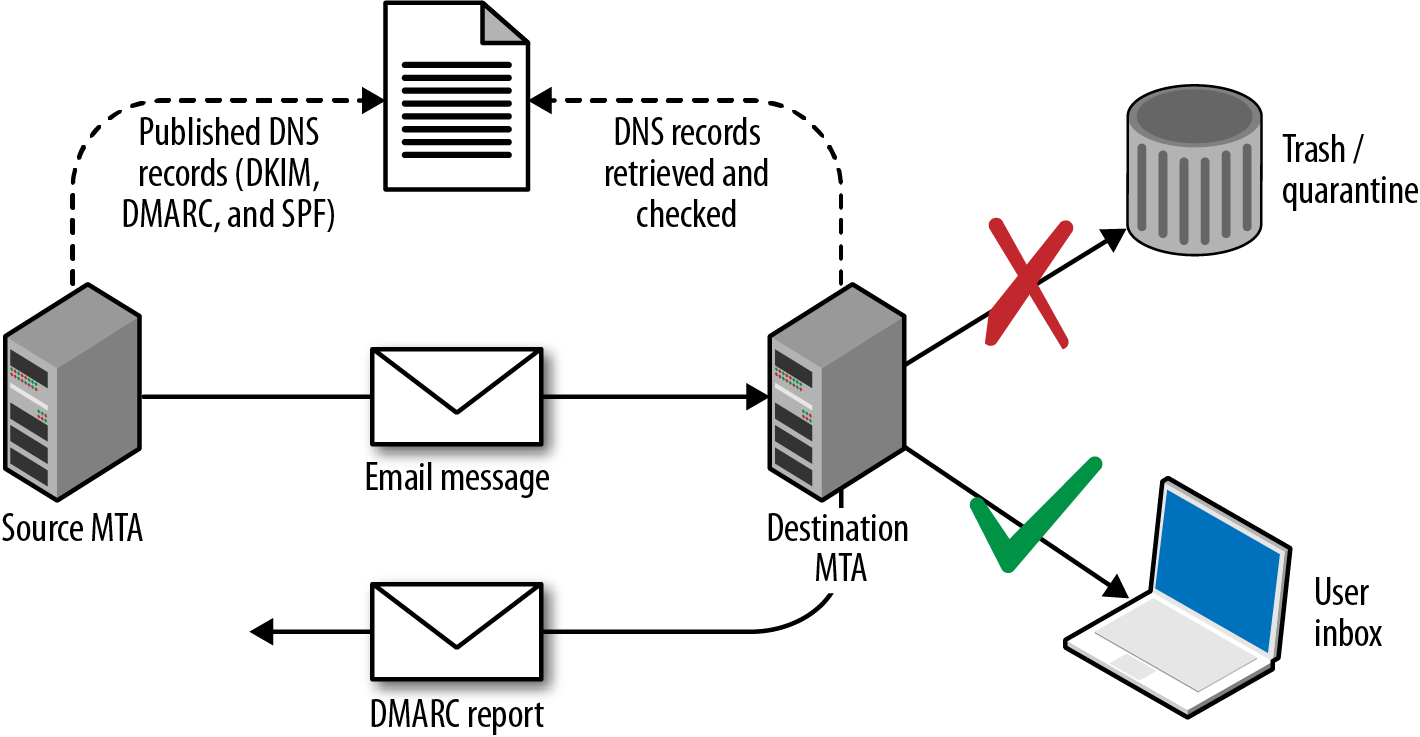

978-1-491-91095-5

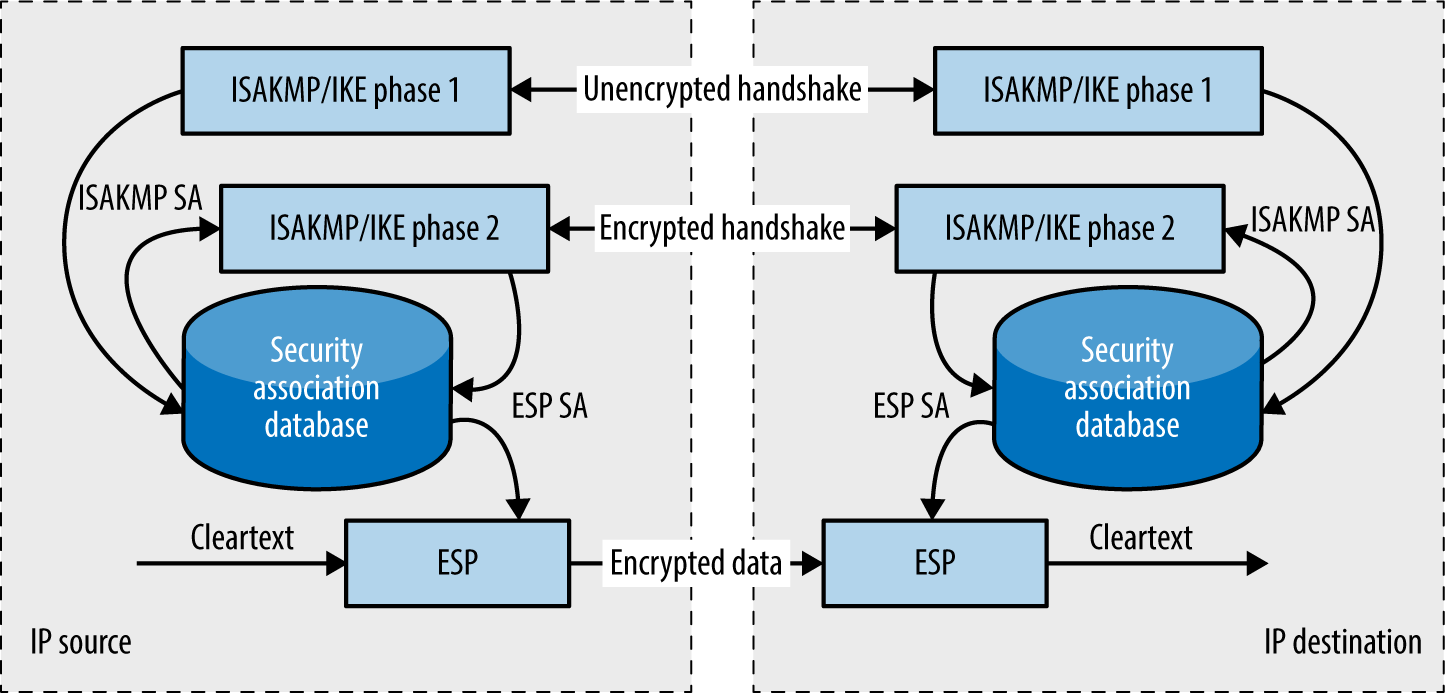

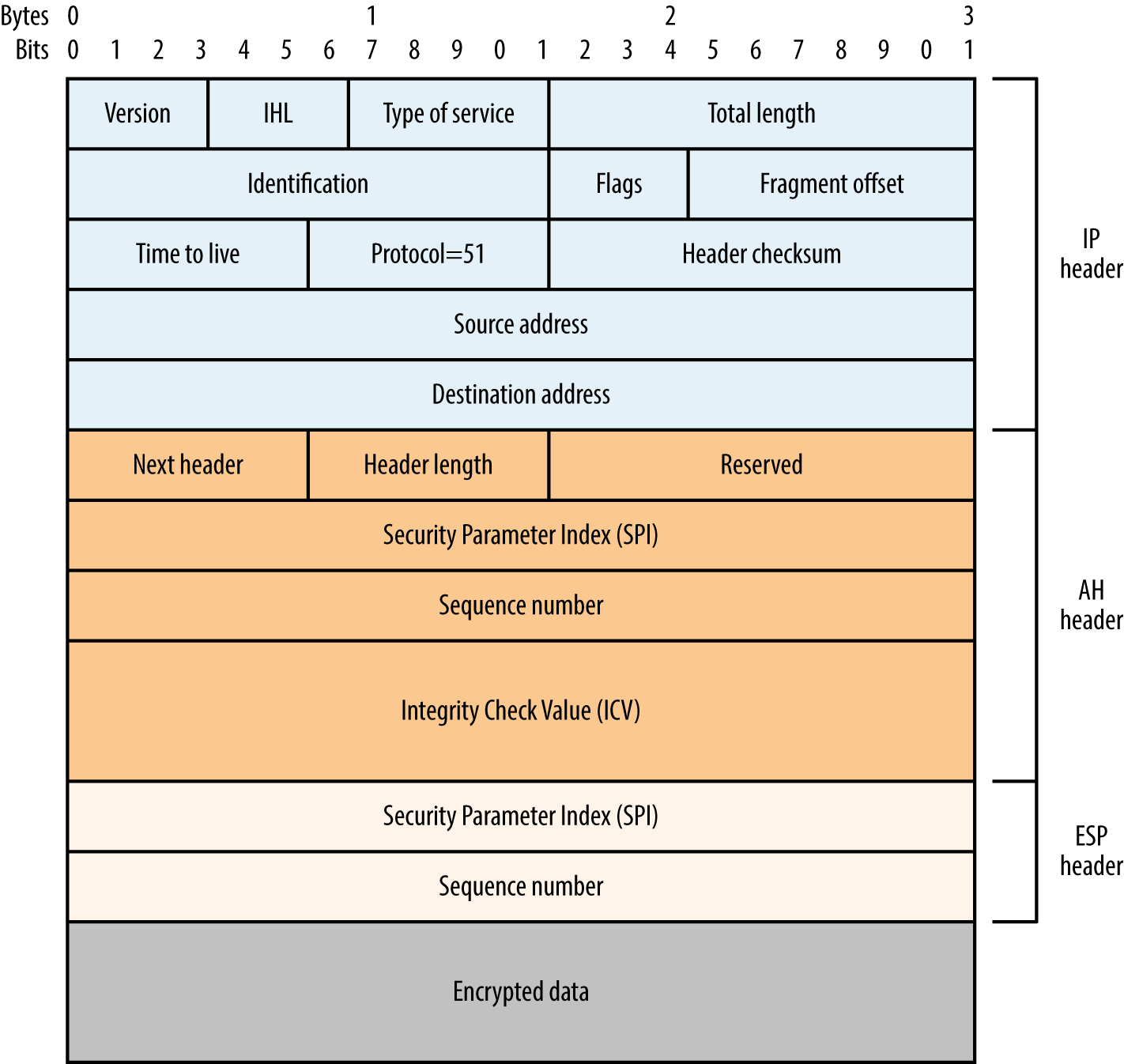

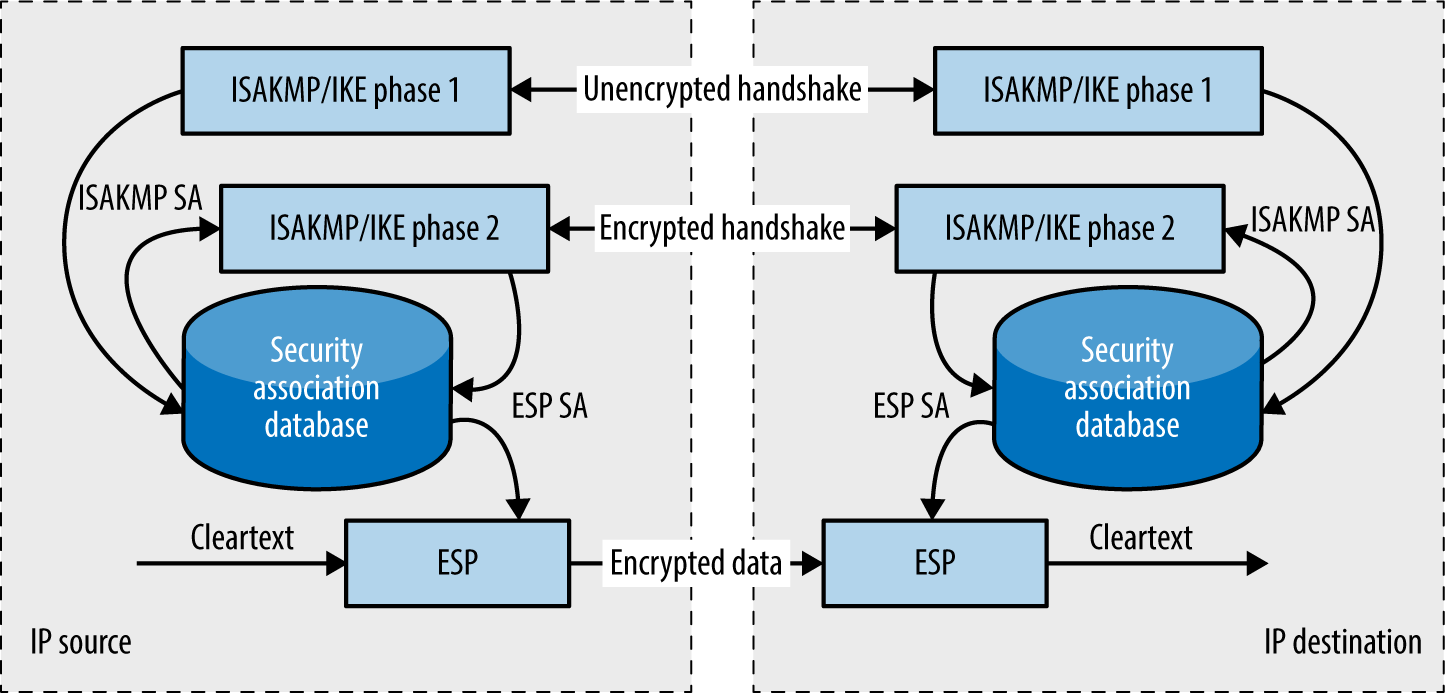

[LSI]

In memory of Barnaby Jack.

Adversaries routinely target networks for gain. As I prepare this third edition of Network Security Assessment, the demand for incident response expertise is also increasing. Although software vendors have worked to improve the security of their products over the past decade, system complexity and attack surfaces have grown, and if anything, the overall integrity of the Internet has degraded.

Attacker tactics have become increasingly refined, combining intricate exploitation of software defects, social engineering, and physical attack tactics to target high-value assets. To make matters worse, many technologies deployed to protect networks have been proven ineffective. Google Project Zero1 team member Tavis Ormandy has publicized severe remotely exploitable flaws within many security products.2

As stakes increase, so does the value of research output. Security researchers are financially incentivized to disclose zero-day vulnerabilities to third parties and brokers, who in turn share the findings with their customers, and in some cases, responsibly notify product vendors. There exists a growing gap by which the number of severe defects known only to privileged groups (e.g., governments and organized criminals) increases each day.

A knee-jerk reaction is to prosecute hackers and curb the proliferation of their tools. The adversaries we face, however, along with the tactics they adopt, are nothing but a symptom of a serious problem: the products we use are unfit for purpose. Product safety is an afterthought for many technology companies, and the challenges we face today a manifestation of this.

To aggravate things further, governments have militarized the Internet and eroded the integrity of cryptosystems used to protect data.3 As security professionals, we must advocate defense in depth to mitigate risks that will likely always exist, and work hard to ensure that our networks are a safe place to do commerce, store data, and communicate with one another. Life for us all would be very different without the Internet and the freedoms it provides.

This book tackles a single area of computer security in detail—undertaking network-based penetration testing in a structured manner. The methodology I present describes how determined attackers scour Internet-based networks in search of vulnerable components and how you can perform similar exercises to assess your environment.

Assessment is the first step any organization should take to manage its risk. By testing your networks in the same way that a determined adversary does, you proactively identify weaknesses within them. In this book, I pair offensive content with bulleted checklists of countermeasures to help you devise a clear technical strategy and fortify your environment accordingly.

This book assumes that you have familiarity with networking protocols and Unix-based operating system administration. If you are an experienced network engineer or security consultant, you should be comfortable with the contents of each chapter. To get the most out of this book, you should be familiar with:

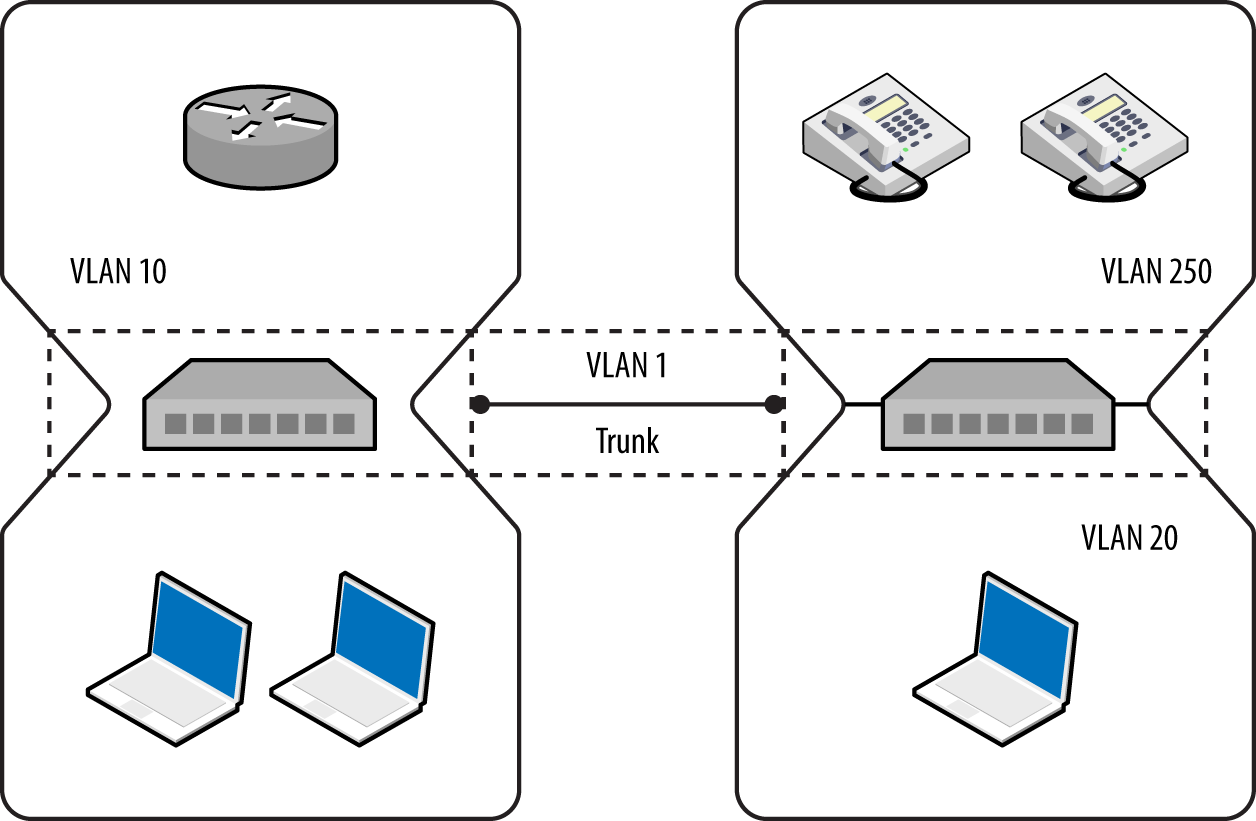

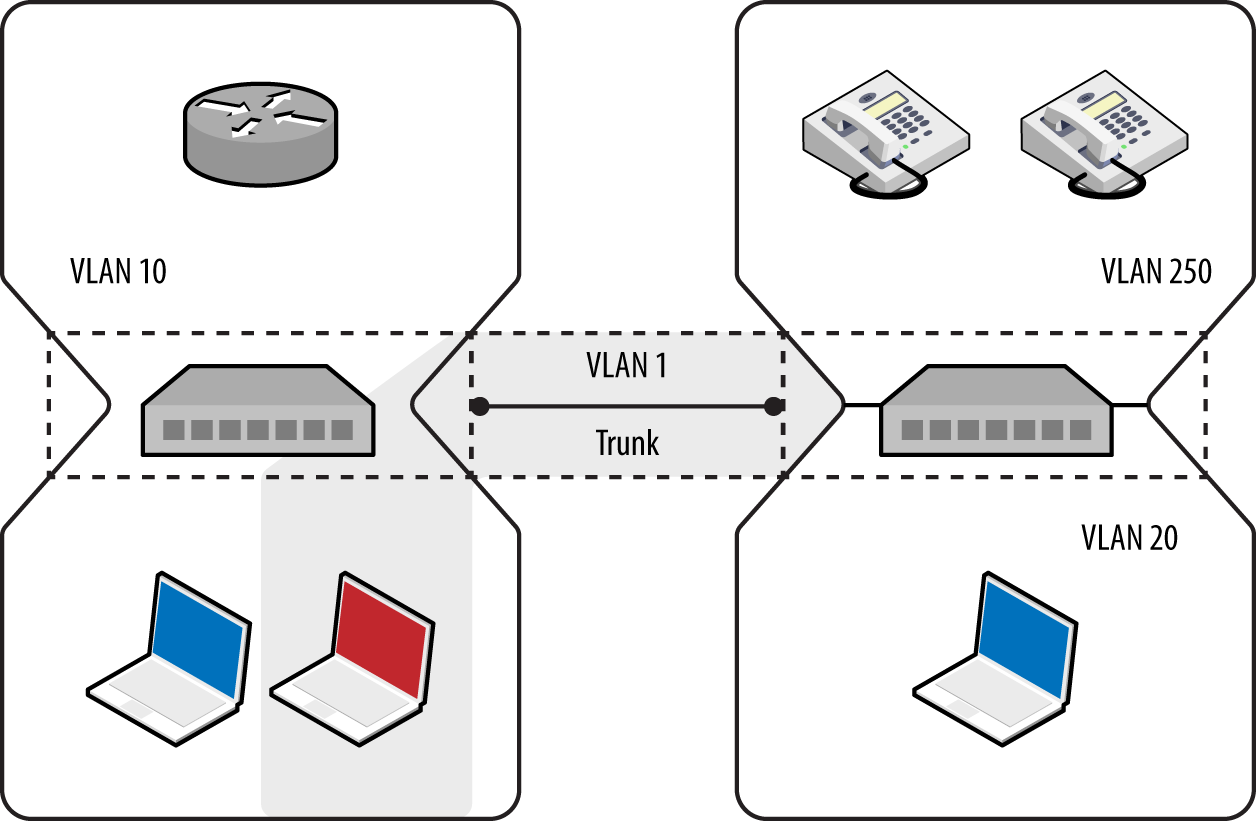

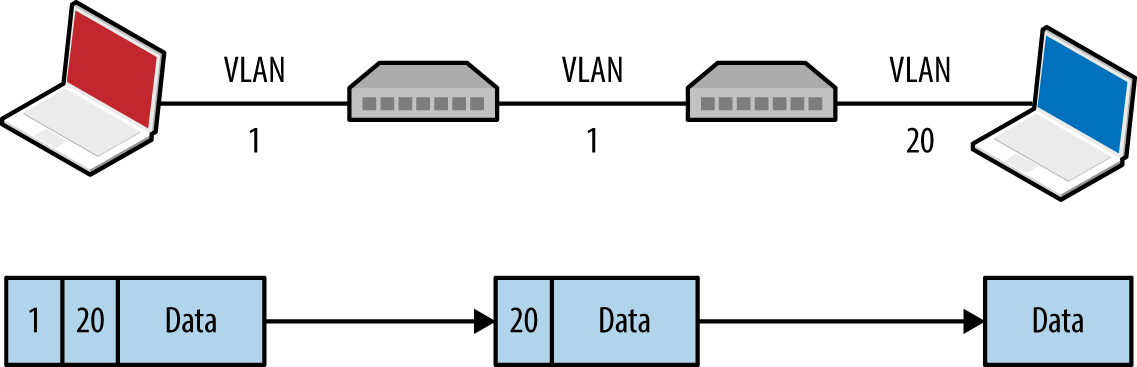

OSI Layer 2 network operation (primarily ARP and 802.1Q VLAN tagging)

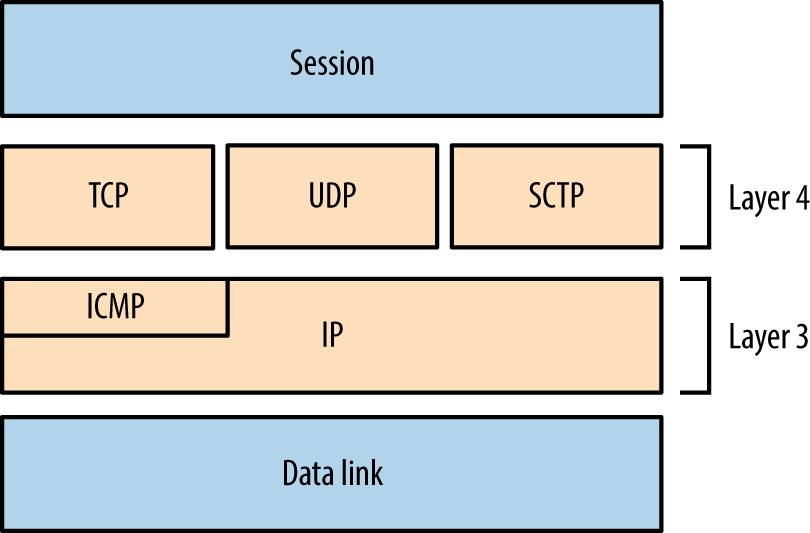

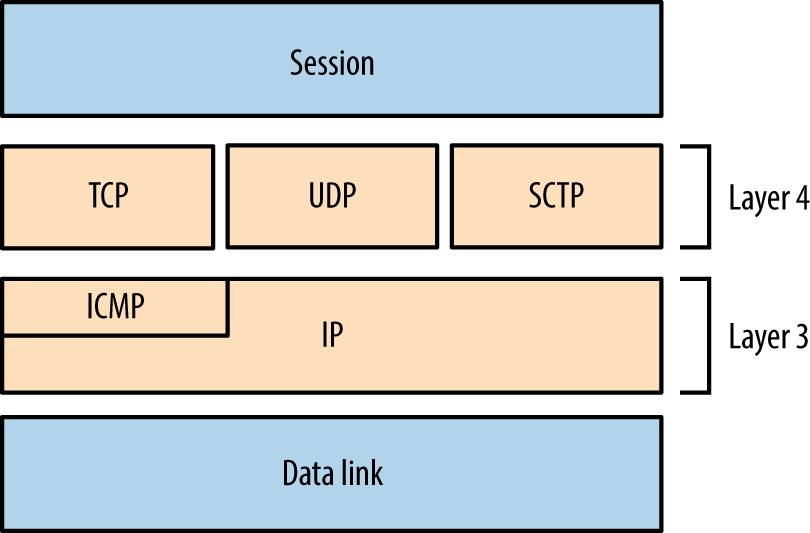

The IPv4 protocol suite, including TCP, UDP, and ICMP

The operation of popular network protocols (e.g., FTP, SMTP, and HTTP)

Basic runtime memory layout and Intel x86 processor registers

Cryptographic primitives (e.g., Diffie-Hellman and RSA key exchange)

Common web application flaws (XSS, CSRF, command injection, etc.)

Configuring and building Unix-based tools in your environment

This book consists of 15 chapters and 3 appendixes. At the end of each chapter is a checklist summarizing the threats and techniques described, along with recommended countermeasures. The appendixes provide reference material, including listings of TCP and UDP ports you might encounter during testing. Here is a brief description of each chapter and appendix:

Chapter 1, Introduction to Network Security Assessment, discusses the rationale behind network security assessment and introduces information assurance as a process, not a product.

Chapter 2, Assessment Workflow and Tools, covers the tools that make up a professional security consultant’s attack platform, along with assessment tactics that should be adopted.

Chapter 3, Vulnerabilities and Adversaries, categorizes vulnerabilities in software via taxonomy, along with low-level descriptions of vulnerability classes and adversary types.

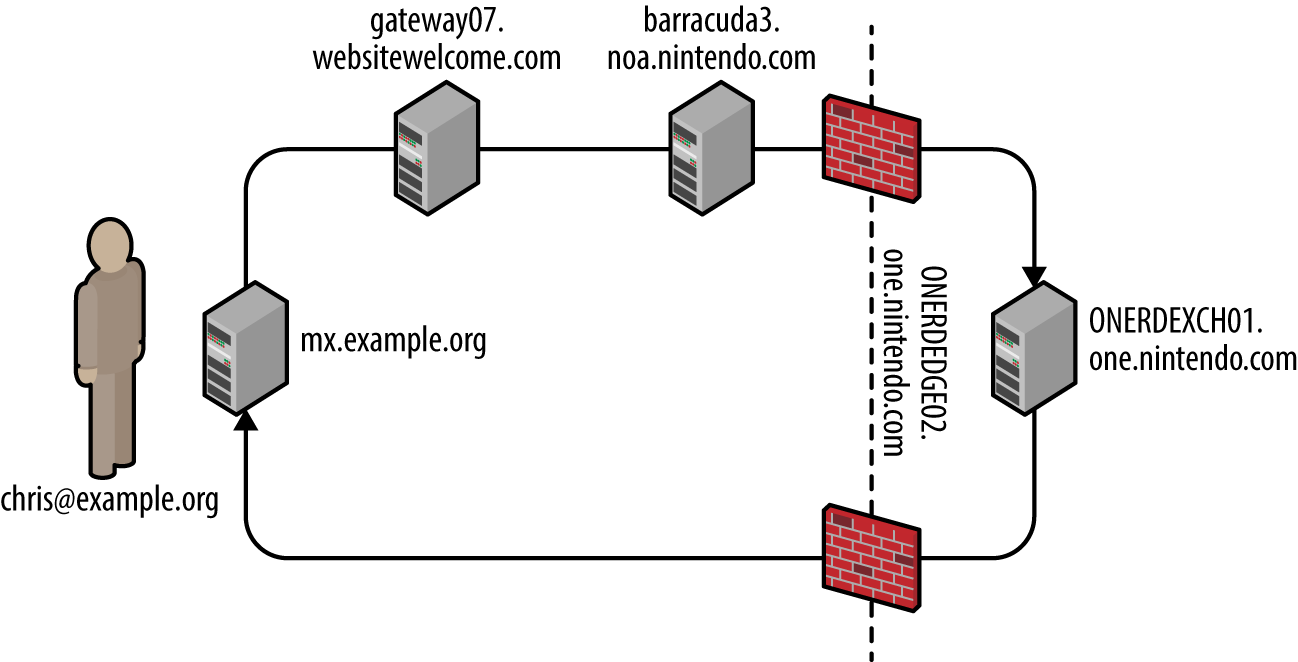

Chapter 4, Internet Network Discovery, describes the Internet-based tactics that a potential attacker adopts to map your network—from open web searches to DNS sweeping and querying of mail servers.

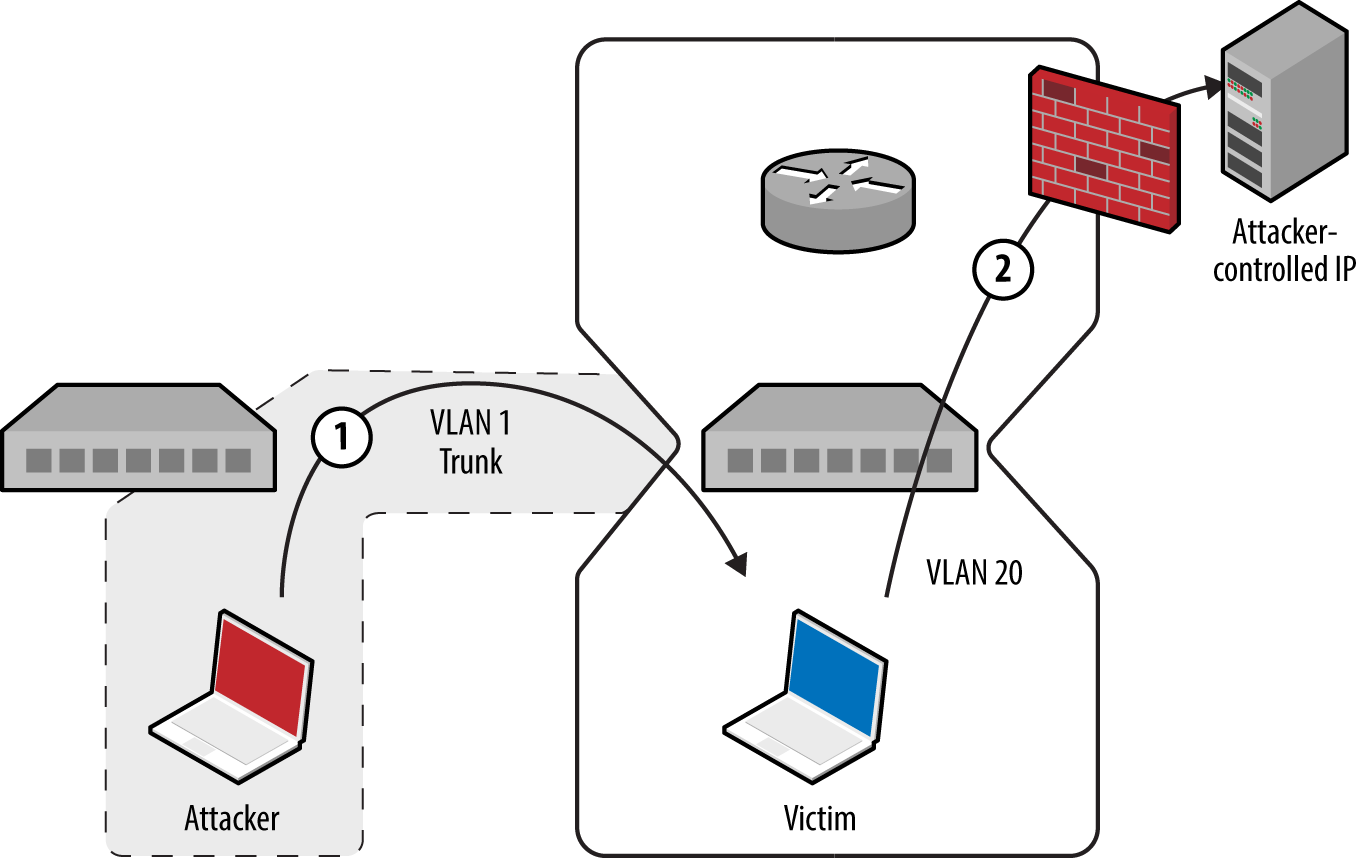

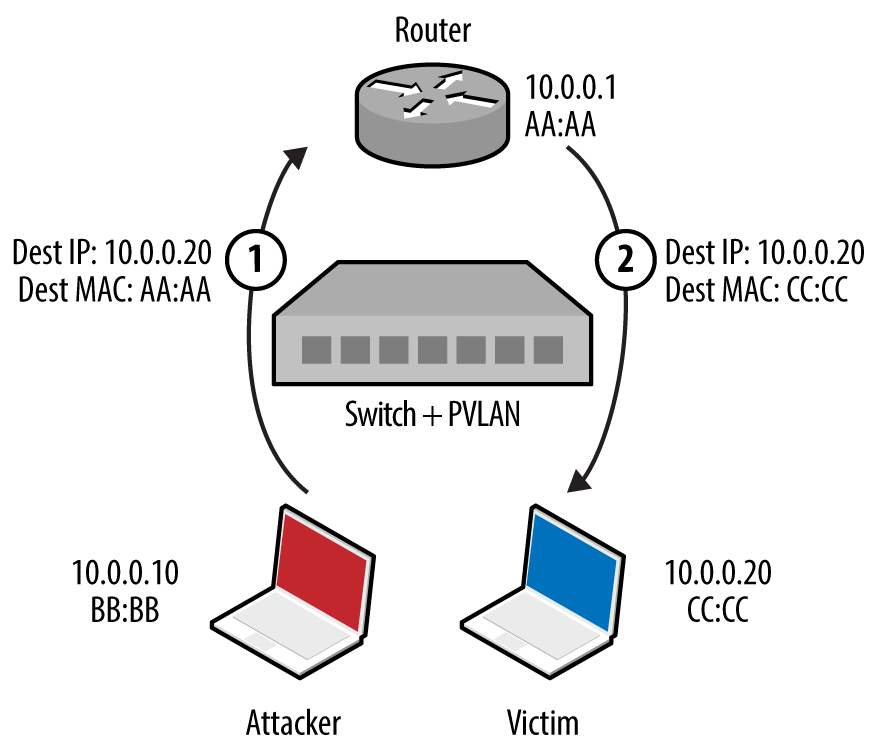

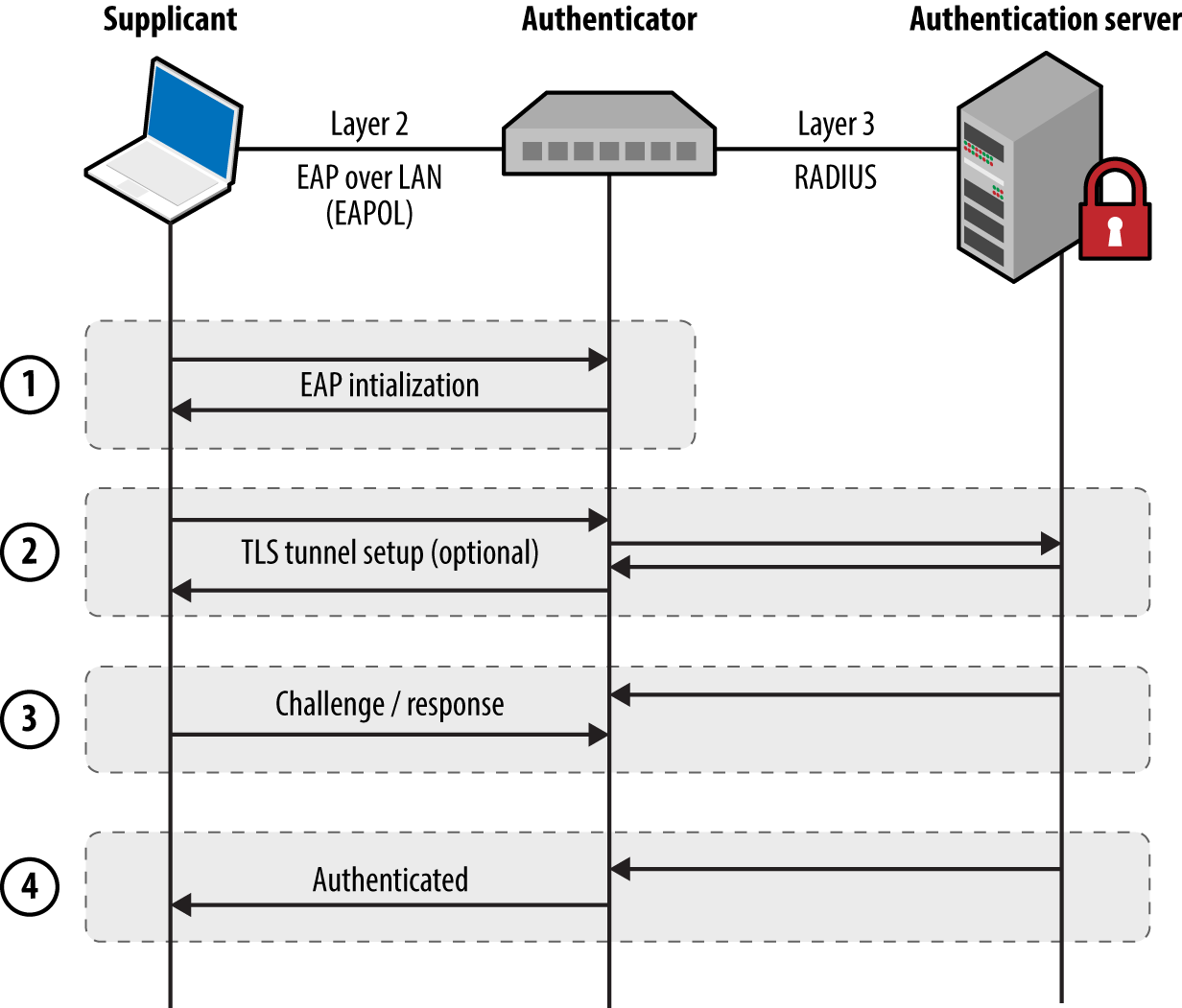

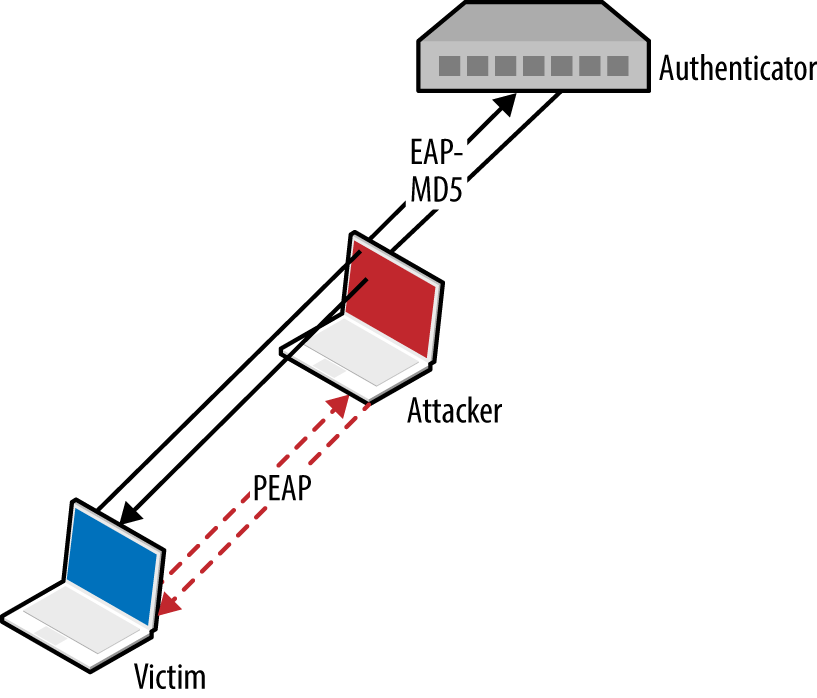

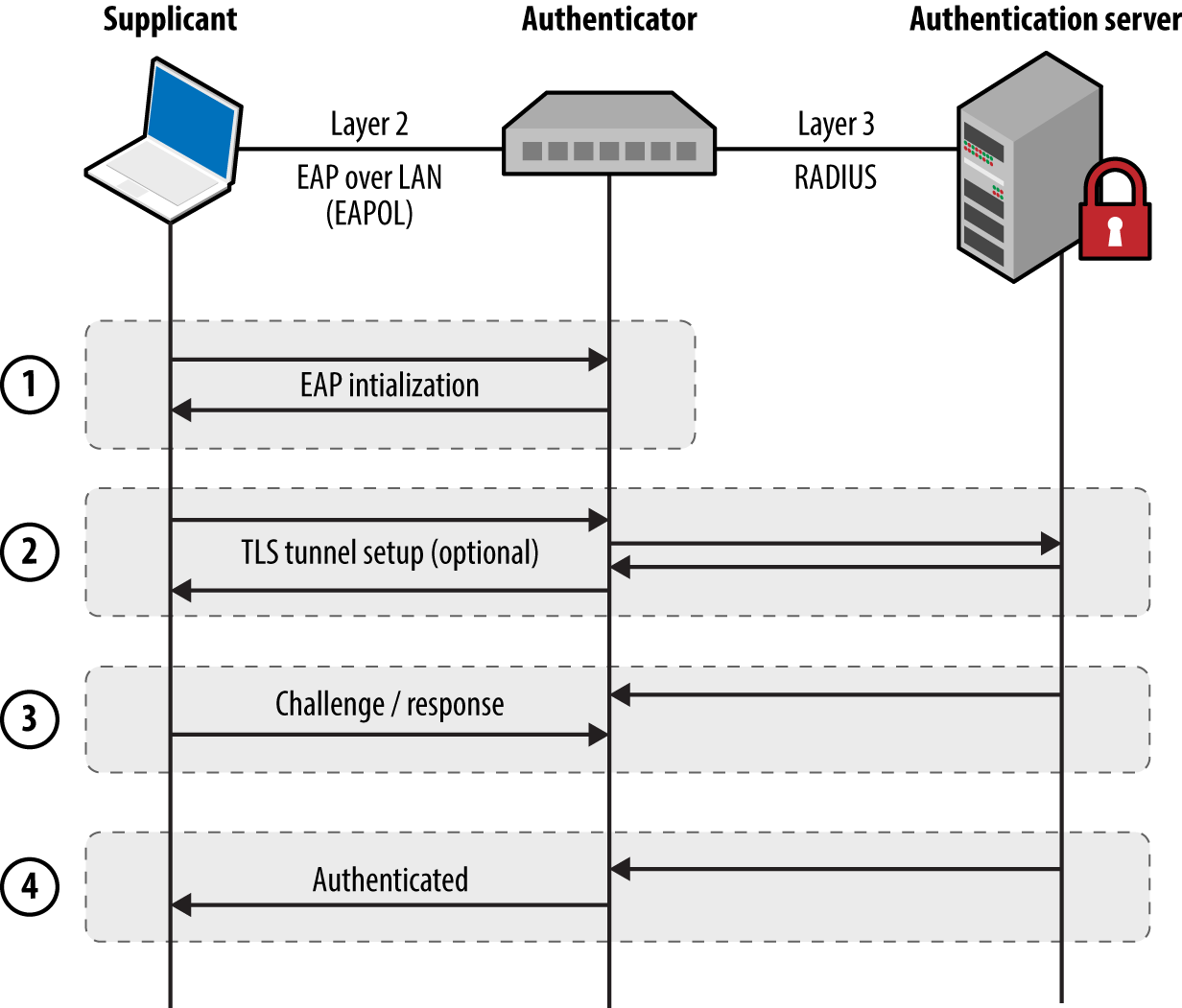

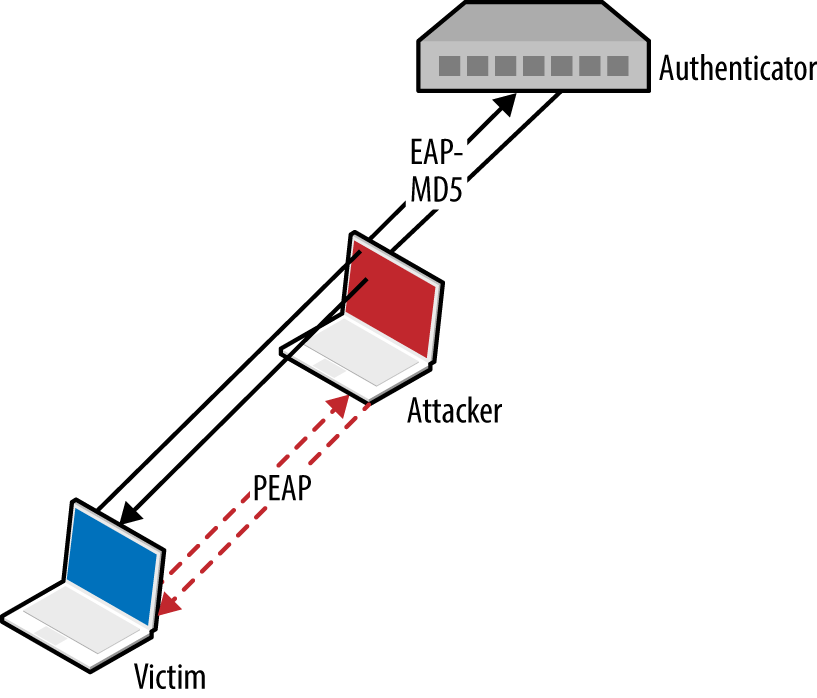

Chapter 5, Local Network Discovery, defines the steps taken to perform local area network discovery and sniffing, along with circumvention of 802.1Q and 802.1X security features.

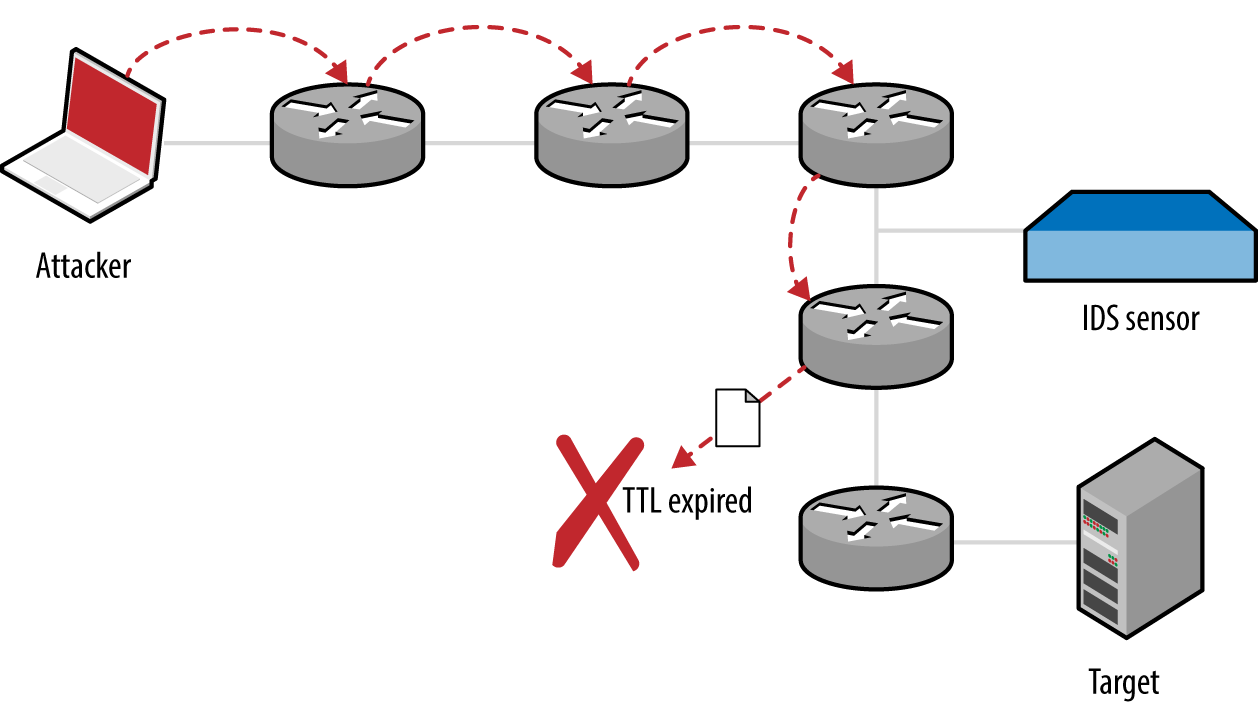

Chapter 6, IP Network Scanning, discusses popular network scanning techniques and their relevant applications. It also lists tools that support such scanning types. IDS evasion and low-level packet analysis techniques are also covered.

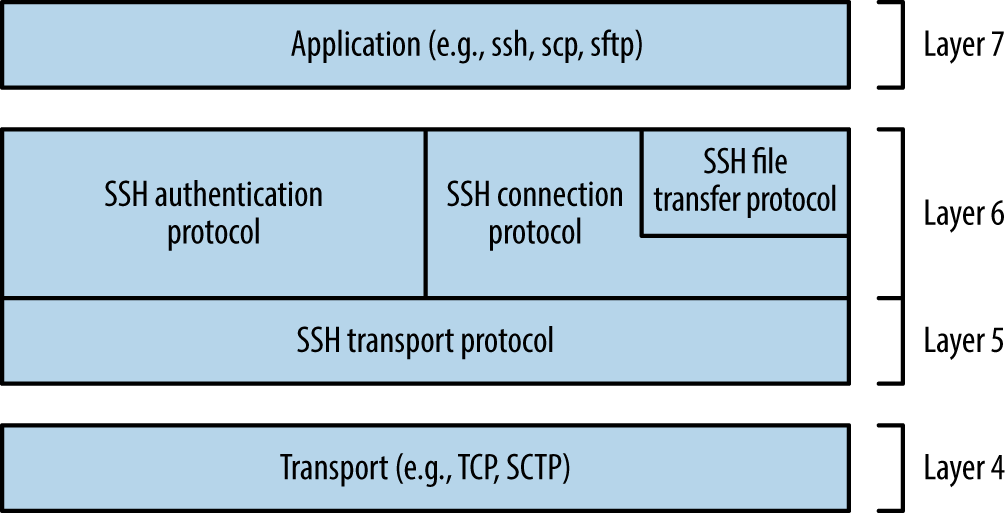

Chapter 7, Assessing Common Network Services, details the approaches used to test services found running across many operating platforms. Protocols covered within this chapter include SSH, FTP, Kerberos, SNMP, and VNC.

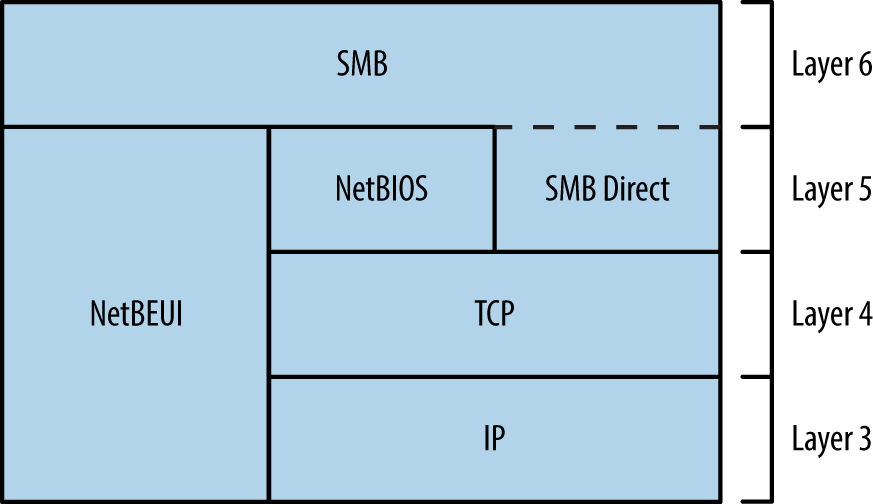

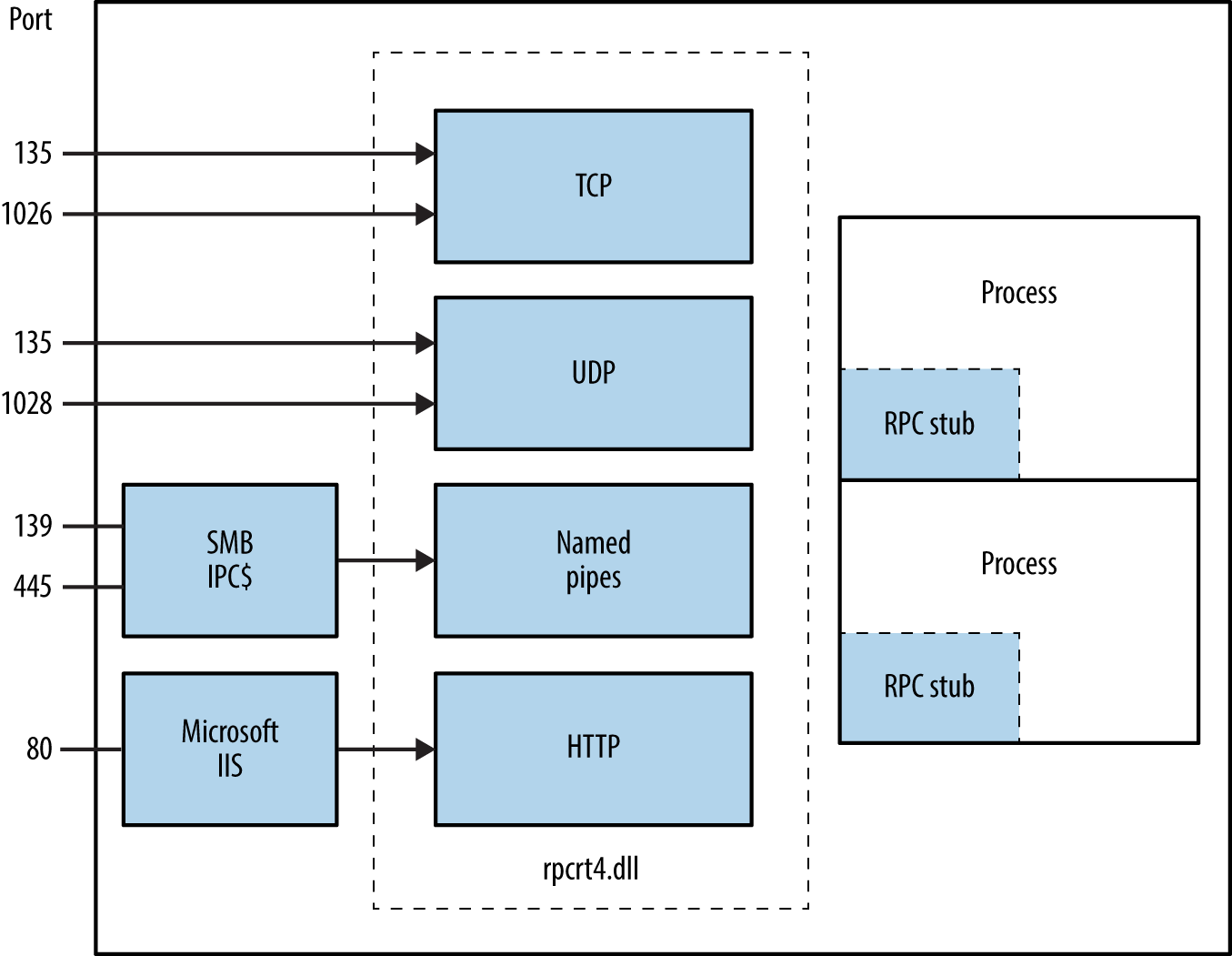

Chapter 8, Assessing Microsoft Services, covers testing of Microsoft services found in enterprise environments (NetBIOS, SMB Direct, RPC, and RDP).

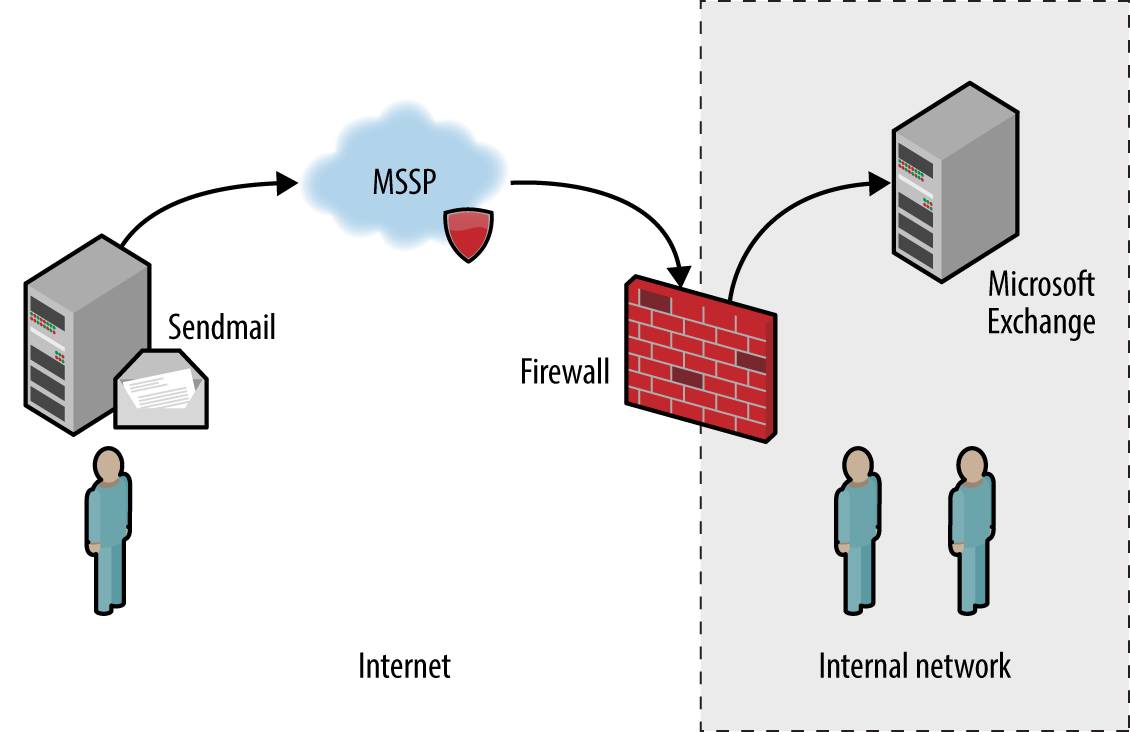

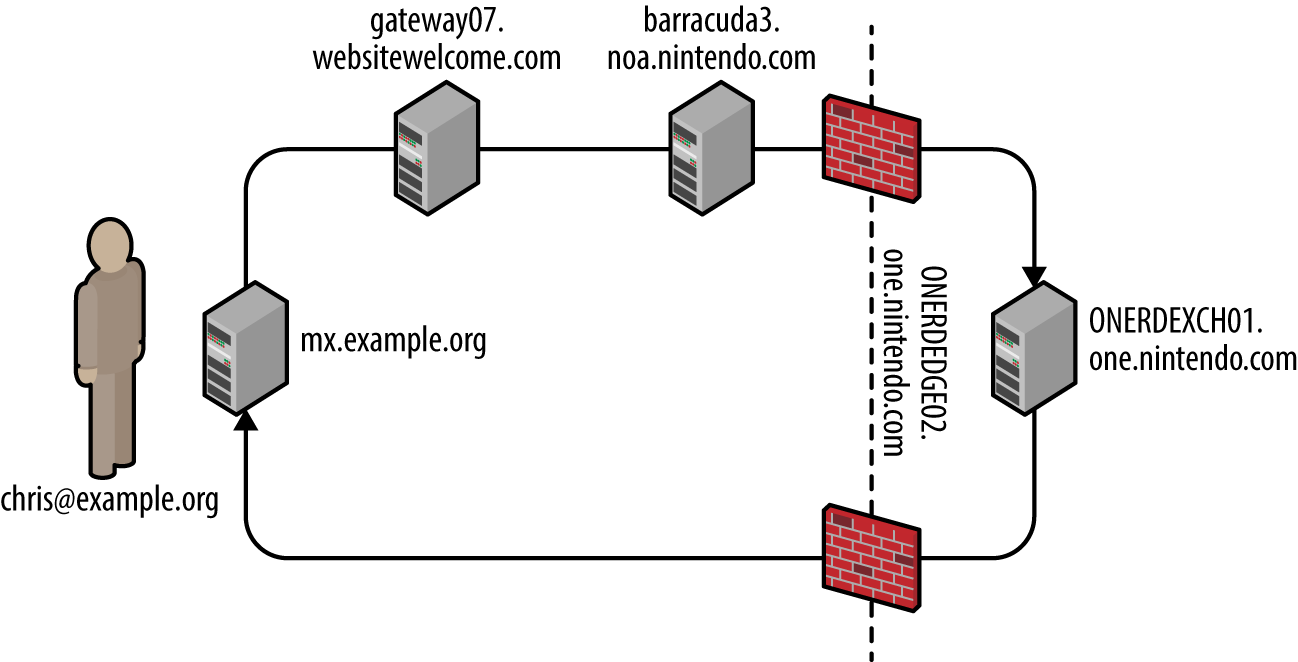

Chapter 9, Assessing Mail Services, details assessment of SMTP, POP3, and IMAP services that transport email. Often, these services can fall afoul to information-leak and brute-force attacks, and in some cases, remote code execution.

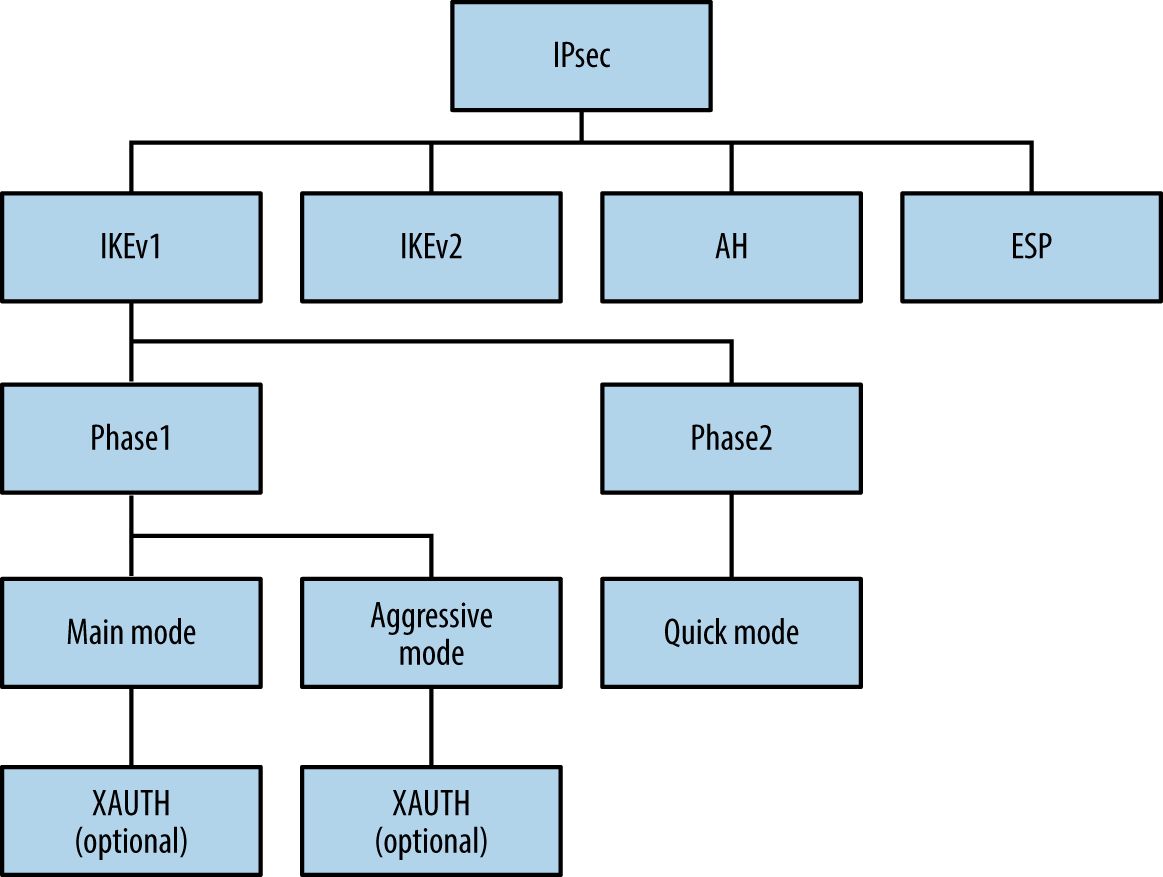

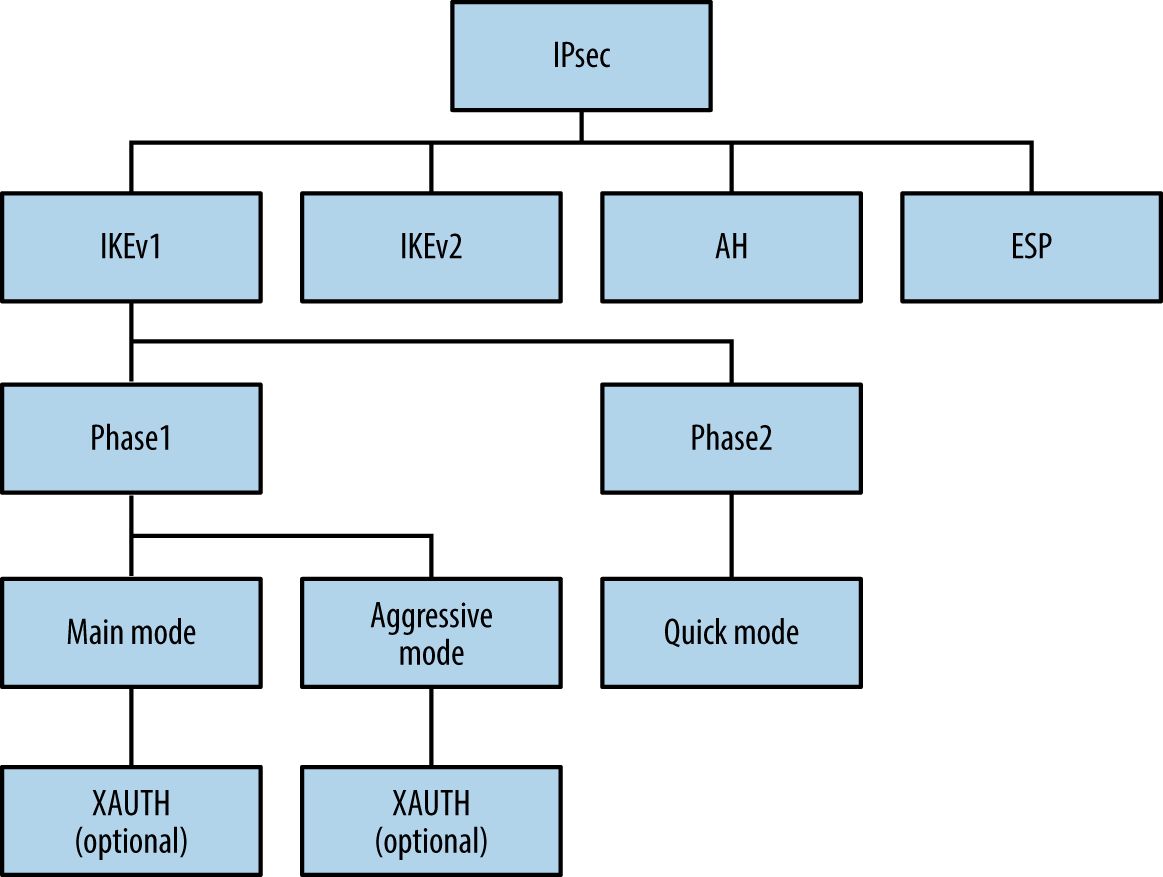

Chapter 10, Assessing VPN Services, covers network-based testing of IPsec and PPTP services that provide secure network access and confidentiality of data in-transit.

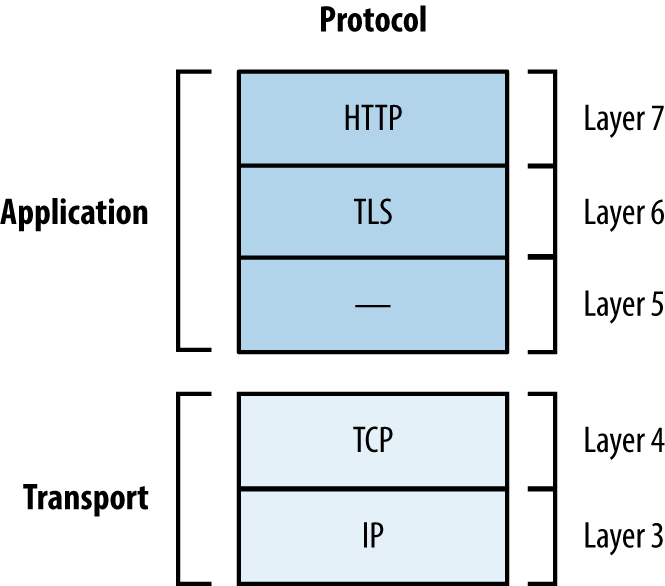

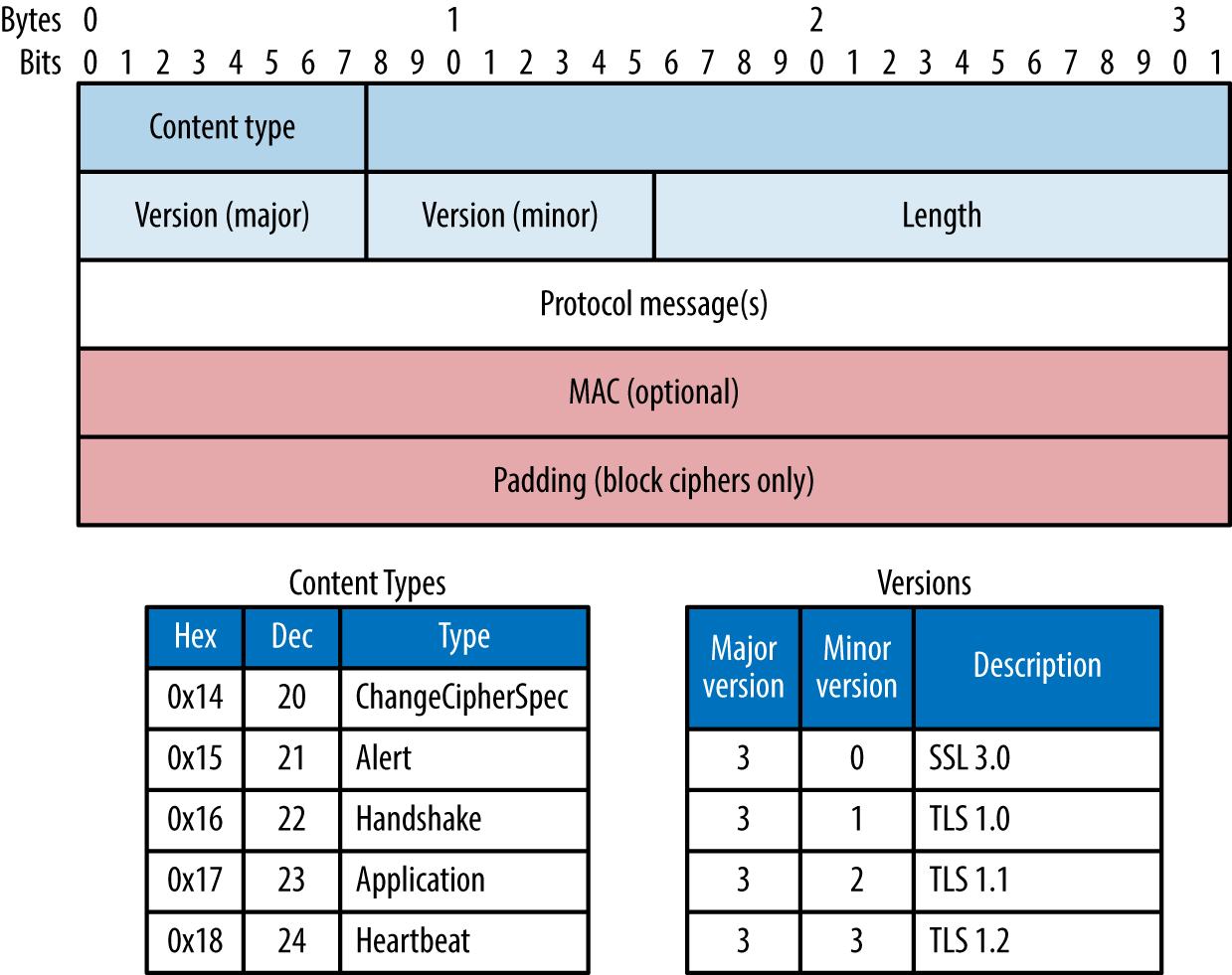

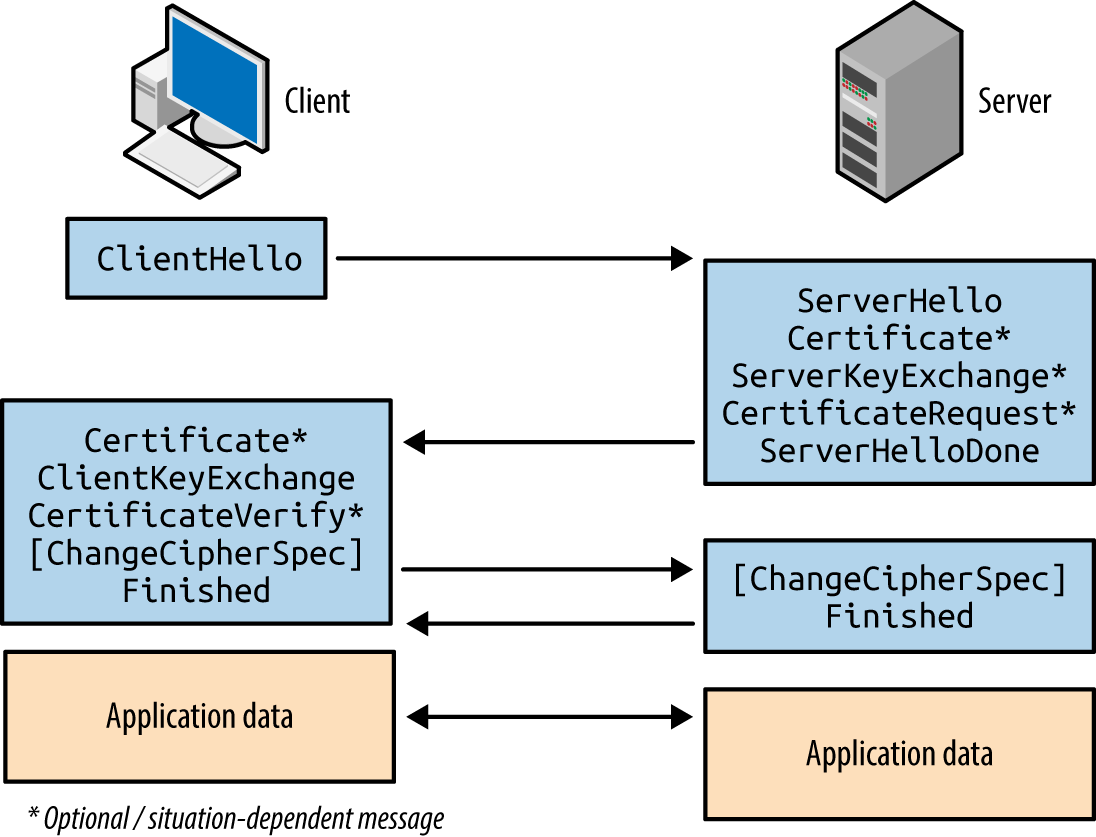

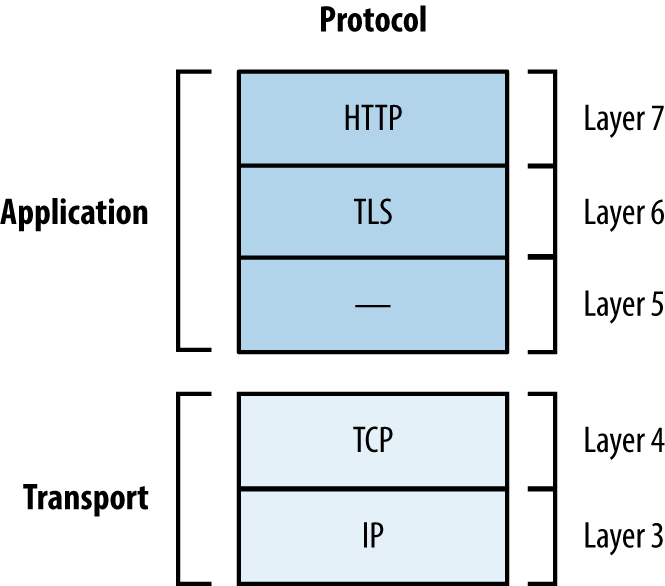

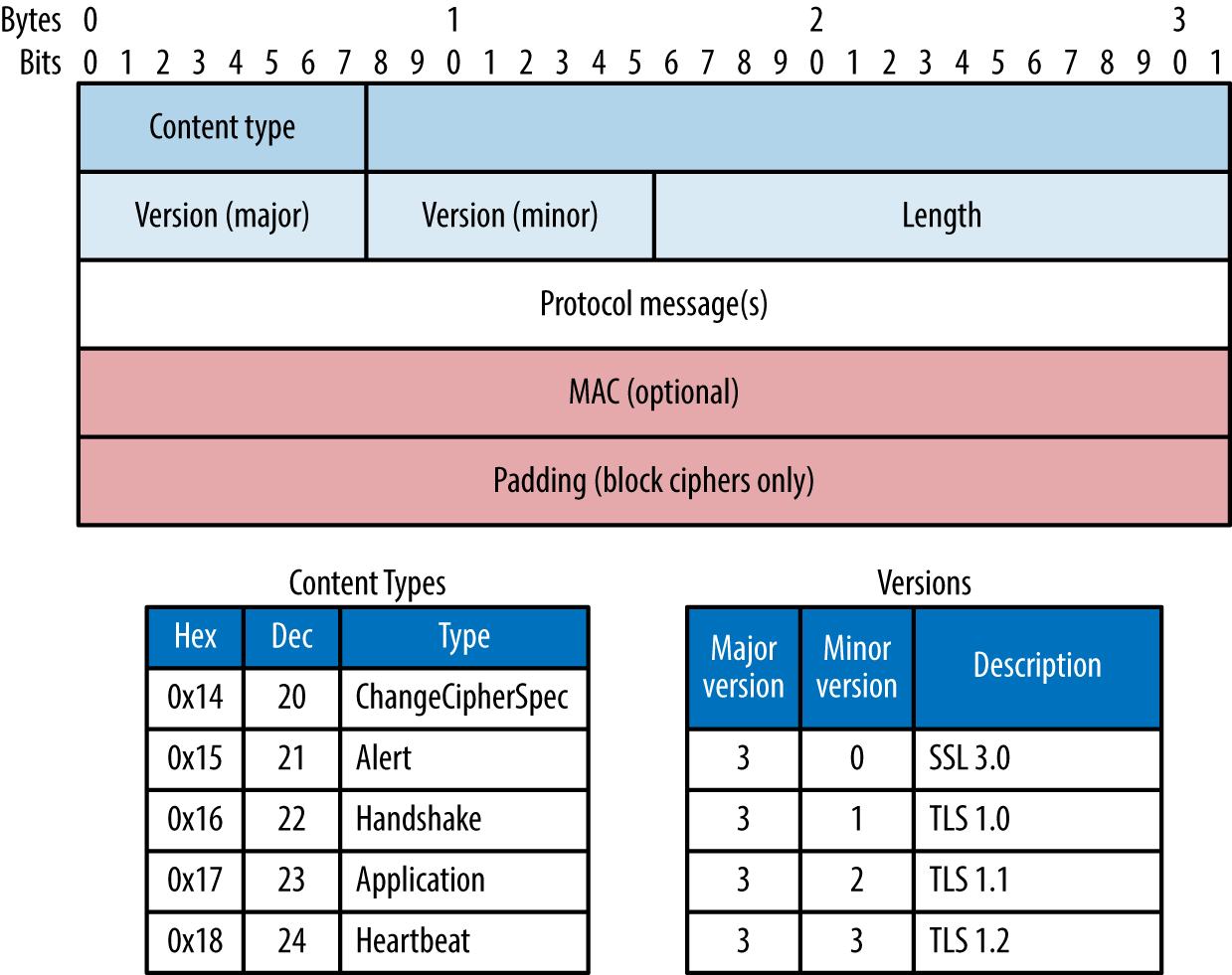

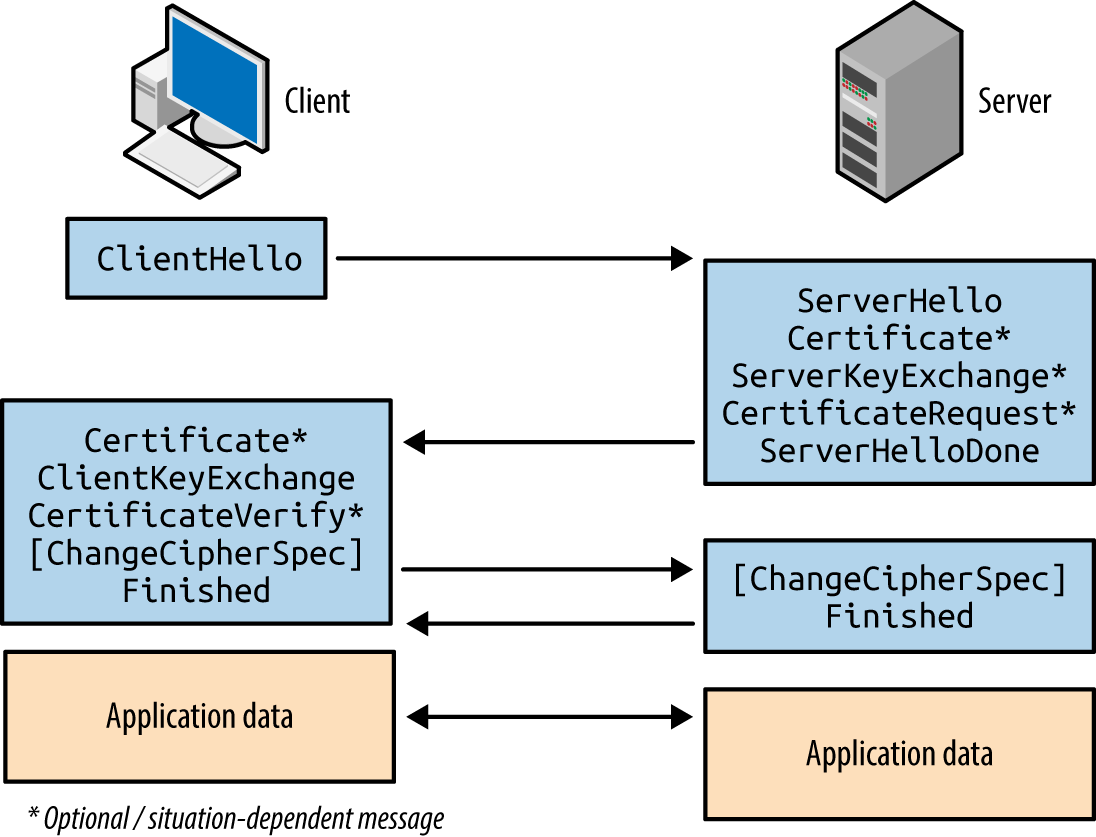

Chapter 11, Assessing TLS Services, details assessment of TLS protocols and features that provide secure access to web, mail, and other network services.

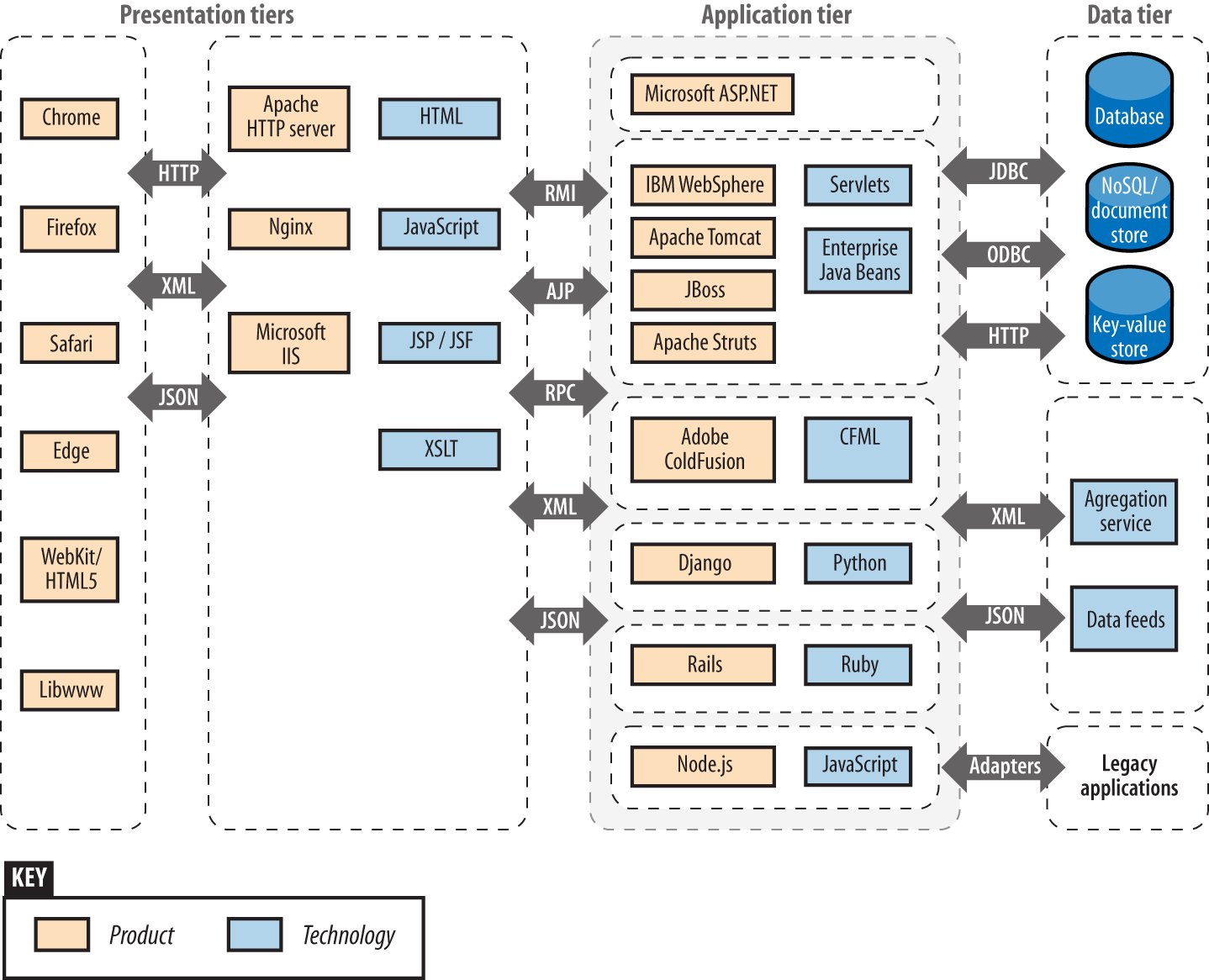

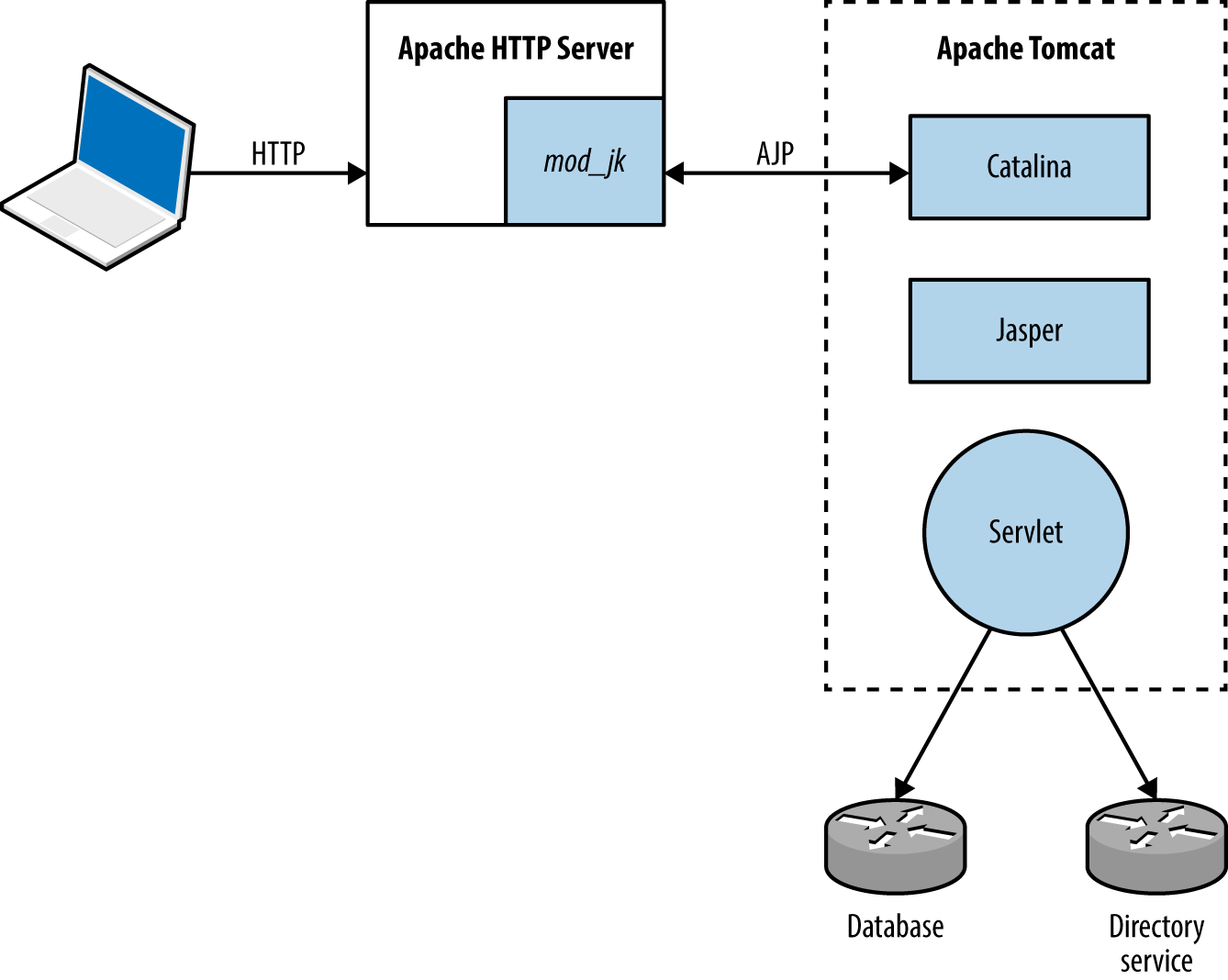

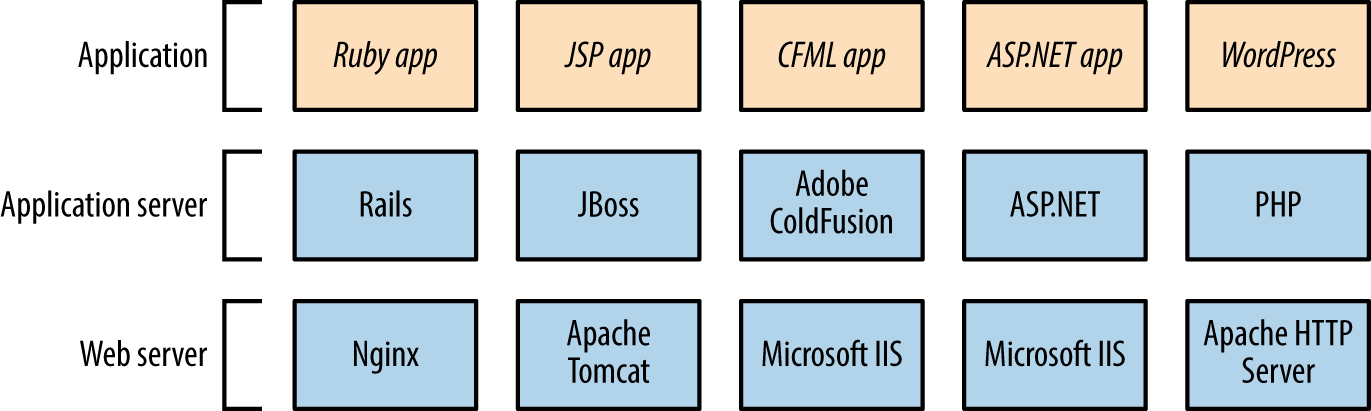

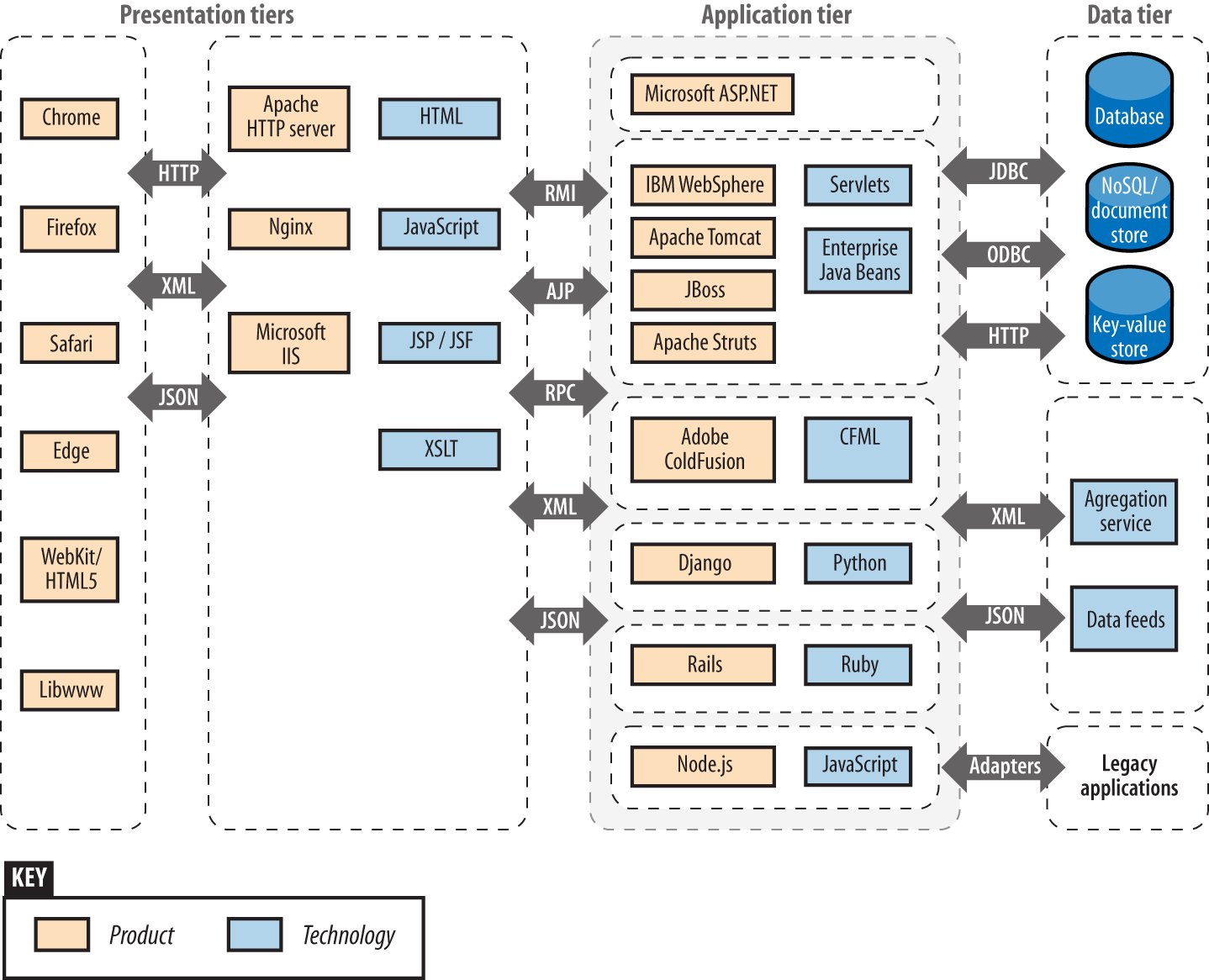

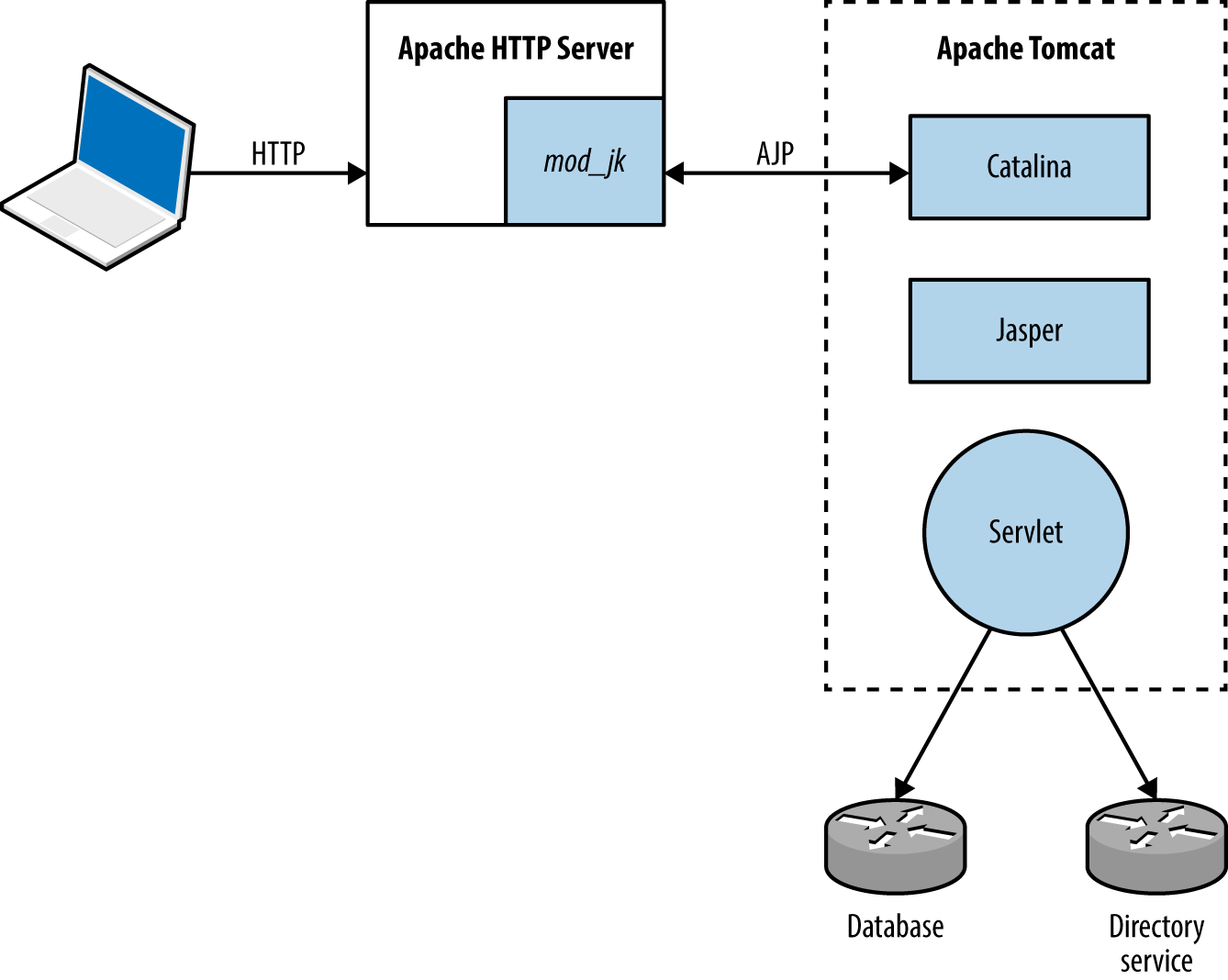

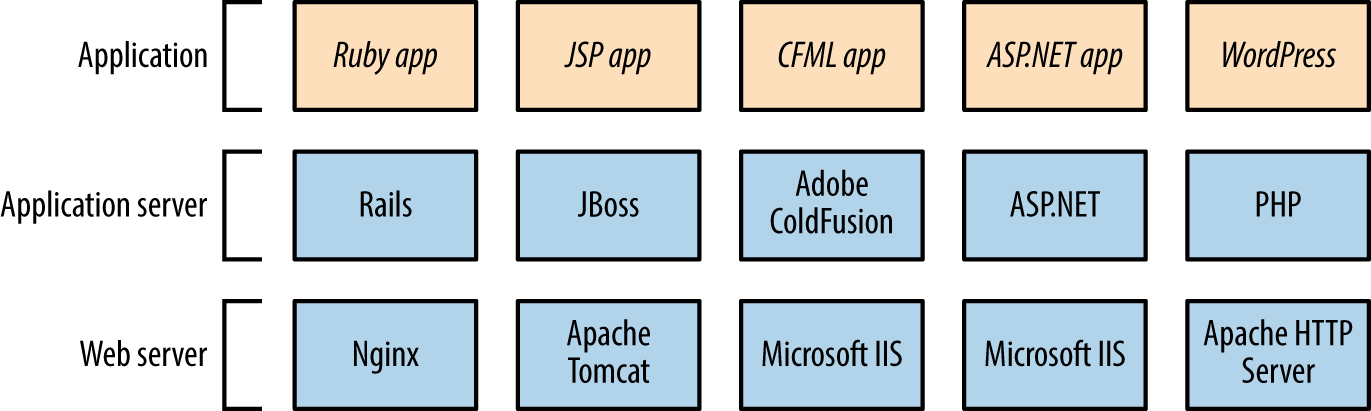

Chapter 12, Web Application Architecture, defines web application server components and describes the way by which they interact with one another, including protocols and data formats.

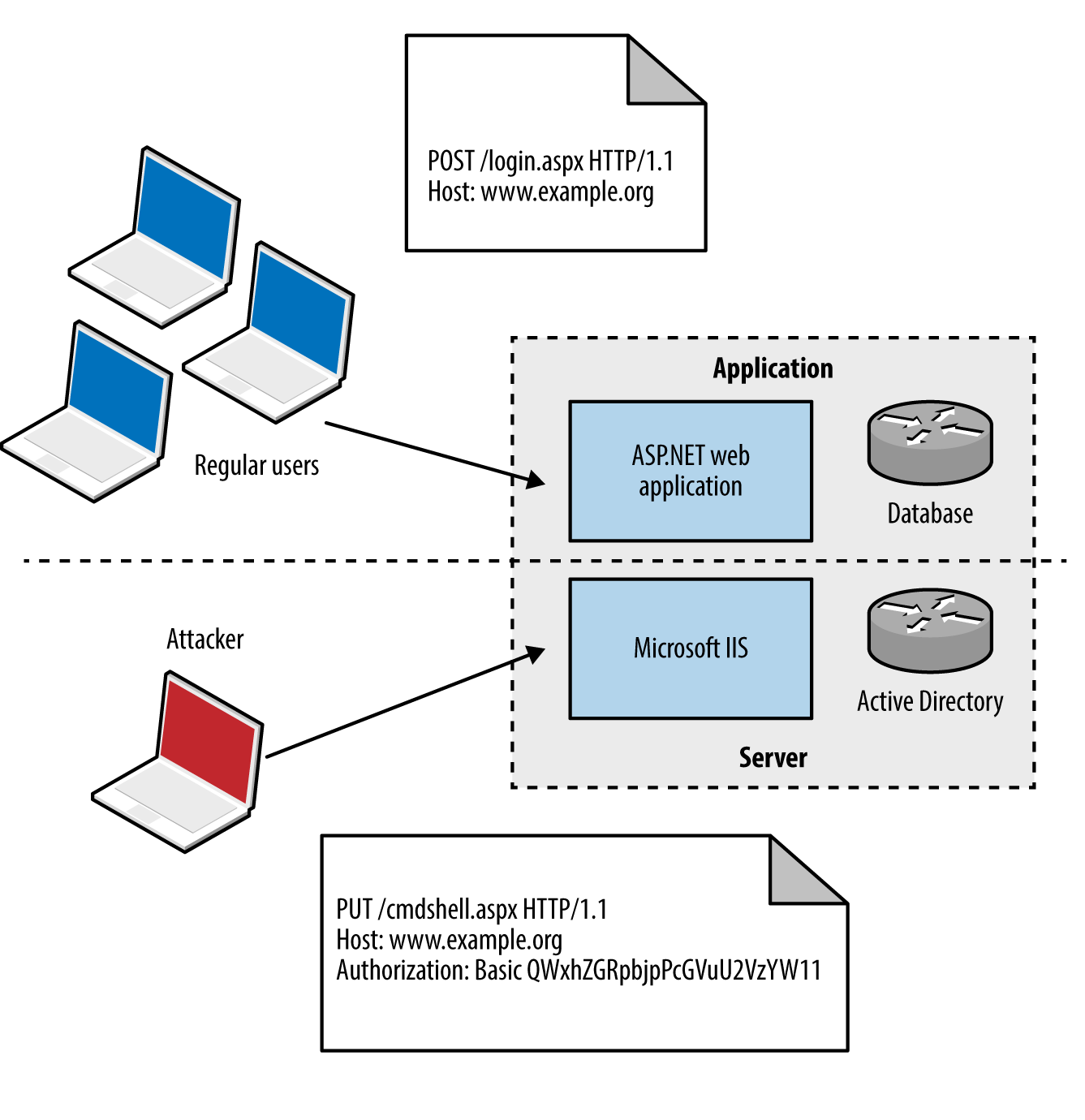

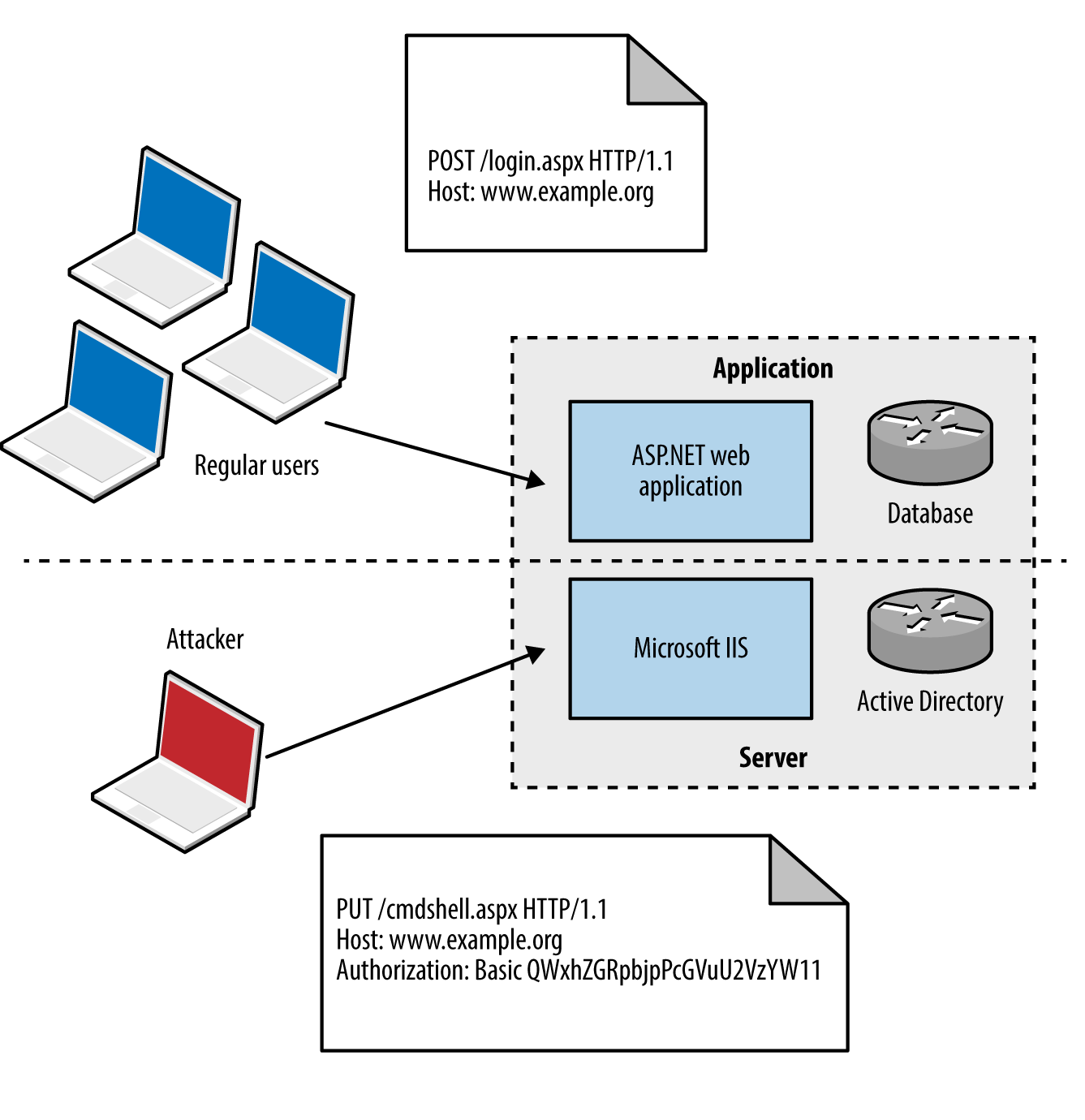

Chapter 13, Assessing Web Servers, covers the assessment of web server software, including Microsoft IIS, Apache HTTP Server, and Nginx.

Chapter 14, Assessing Web Application Frameworks, details the tactics used to uncover flaws within frameworks, including Apache Struts, Rails, Django, Microsoft ASP.NET, and PHP.

Chapter 15, Assessing Data Stores, covers remote assessment of database servers (e.g., Oracle Database, Microsoft SQL Server, and MySQL), storage protocols, and distributed key-value stores found within larger systems.

Appendix A, Common Ports and Message Types, contains TCP, UDP, and ICMP listings, and details respective assessment chapters.

Appendix B, Sources of Vulnerability Information, lists public sources of vulnerability and exploit information so that you can devise matrixes to quickly identify areas of potential risk when assessing exposed services.

Appendix C, Unsafe TLS Cipher Suites, details vulnerable cipher suites supported by TLS that should be disabled and avoided where possible.

Throughout the book, references are made to particular IETF Request for Comments (RFC) drafts,4 documents, and MITRE Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) entries.5 Published RFCs define the inner workings and mechanics of protocols including SMTP, FTP, TLS, HTTP, and IKE. The MITRE CVE list is a dictionary of publicly known information security vulnerabilities, and individual entries (formatted by year, along with a unique identifier) allow us to track particular flaws.

This book describes vulnerabilities that are exploited by both unauthenticated and authenticated users against network services in particular. Examples of tactics that are largely out of scope include local privilege escalation, denial of service conditions, and breaches performed with local network access (including man-in-the-middle attacks).

Vulnerabilities with CVE references dated 2008 and prior are not covered in this title. Previous editions of this book were published in 2004 and 2007; they detail older vulnerabilities in server packages including Microsoft IIS, Apache, and OpenSSL.

A number of less common server packages are not covered for the sake of brevity. During testing, you should manually search the NIST National Vulnerability Database (NVD)6 to investigate known issues in the services you have identified.

This book has been written in line with recognized penetration testing standards, including NIST SP 800-115, NSA IAM, CESG CHECK, CREST, Tiger Scheme, The Cyber Scheme, PCI DSS, and PTES. You can use the material within this book to prepare for infrastructure and web application testing exams across these accreditation bodies.

In 2008, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released special publication 800-115,7 which is a technical guide for security testing. PCI DSS materials refer to the document as an example of industry-accepted best practice. SP 800-115 describes the assessment process at a high level, along with low-level tests that should be undertaken against systems.

The US National Security Agency (NSA) published the INFOSEC Assessment Methodology (IAM) framework to help consultants and security professionals outside of the NSA provide assessment services to clients. The IAM framework defines three levels of assessment relative to testing of computer networks:

This book describes technical vulnerability scanning and penetration testing techniques used within levels 2 and 3 of the IAM framework.

The UK Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) has an information assurance arm known as the Communications and Electronics Security Group (CESG). In the same way that the NSA IAM framework enables security consultants outside of government to provide assessment services, CESG operates a program known as CHECK8 to evaluate and accredit testing teams within the UK.

Unlike the NSA IAM, which covers many aspects of information security (including review of security policy, antivirus, backups, and disaster recovery), CHECK squarely tackles network security assessment. A second program is the CESG Listed Adviser Scheme (CLAS), which covers information security in a broader sense by addressing ISO/IEC 27001, security policy creation, and auditing.

Consultants navigate a CESG-approved assault course (primarily those maintained by CREST and the Tiger Scheme) to demonstrate ability and achieve accreditation. The CESG CHECK notes list the following examples of technical competence:

Use of DNS information retrieval tools for both single and multiple records, including an understanding of DNS record structure relating to target hosts

Use of ICMP, TCP, and UDP network mapping and probing tools

Demonstration of TCP service banner grabbing

Information retrieval using SNMP, including an understanding of MIB structure relating to target system configuration and network routes

Understanding of common weaknesses in routers and switches relating to Telnet, HTTP, SNMP, and TFTP access and configuration

The following are Unix-specific competencies:

User enumeration (via finger, rusers, rwho, and SMTP techniques)

Enumeration of RPC services and demonstration of security implications

Identification of Network File System (NFS) weaknesses

Testing for weaknesses within r-services (rsh, rexec, and rlogin)

Detection of insecure X Windows servers

Identification of weaknesses within web, FTP, and Samba services

Here are Windows-specific competencies:

Assessment of NetBIOS, SMB, and RPC services to enumerate users, groups, shares, domains, password policies, and associated weaknesses

Username and password grinding via SMB and RPC services

Demonstrating the presence of known flaws within Microsoft IIS and SQL Server

This book documents assessment tactics across these disciplines, along with supporting information to help you gain a sound understanding of the vulnerabilities. Although the CHECK program assesses the methodologies of consultants who wish to perform UK government security testing work, security teams and organizations elsewhere should be aware of the framework.

Within the UK, a number of bodies provide both training and examination through CESG-approved assault courses. Qualifications provided by these organizations are recognized by CESG as being CHECK equivalent, as follows:

The Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council (PCI SSC) maintains the PCI Data Security Standard (PCI DSS), which requires payment processors, merchants, and those using payment card data to abide to specific control objectives, including:

Build and maintain a secure network

Protect cardholder data

Maintain a vulnerability management program

Implement strong access control measures

Regularly monitor and test networks

Maintain an information security policy

PCI DSS version 3.1 is the current standard. Within the document, there are two requirements for vulnerability scanning and penetration testing by payment processors and merchants:

This book is written in line with NIST SP 800-115 and other published standards, so you can use the methodology to perform internal and external testing and fulfill PCI DSS requirement 11.3 in particular.

PCI SSC recognizes the Penetration Testing Execution Standard (PTES)9 as a reference framework for testing, which consists of seven sections. The PTES site includes detailed material across the sections, as follows:

Preengagement interactions

Intelligence gathering

Threat modeling

Vulnerability analysis

Exploitation

Post-exploitation

Reporting

URLs for tools in this book are listed so that you can browse the latest files and papers on each respective site. If you are worried about Trojan horses or other malicious content within these executables, they have been virus checked and are available via the book’s website. You will likely encounter a safety warning when trying to access this page, they are hacking tools after all!

Supplemental material (code examples, exercises, etc.) is available for download at http://examples.oreilly.com/9780596006112/tools/.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Network Security Assessment by Chris McNab (O’Reilly). Copyright 2017 Chris McNab, 978-1-491-91095-5.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Constant widthConstant width bold italicConstant width boldThis icon signifies a tip, suggestion, or general note.

This icon indicates a warning or caution.

Safari (formerly Safari Books Online) is a membership-based training and reference platform for enterprise, government, educators, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, Learning Paths, interactive tutorials, and curated playlists from over 250 publishers, including O’Reilly Media, Harvard Business Review, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Adobe, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, and Course Technology, among others.

For more information, please visit http://oreilly.com/safari.

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

There’s a web page for this book that lists errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://bit.ly/network-security-assessment-3e.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about books, conferences, Resource Centers, and the O’Reilly Network, see the O’Reilly website.

Throughout my career, many have provided invaluable assistance, and most know who they are. My late friend Barnaby Jack helped me secure a job in 2009 that changed my life for the better. I miss him dearly, and the Jägermeister doesn’t taste the same.

Thanks to a Myers–Briggs INTP personality type, I can be quiet and a challenge to deal with at times. I don’t mean to be, and thus deeply appreciate those who have put up with me over the years, particularly the girlfriends and my family.

I extend my gratitude to the O’Reilly Media team for their continued support, patience, and unshakable faith. This is an important book to maintain, and with their help it will eventually make the world a safer place.

Computer systems have become so nebulous that I had to call on many subject-matter experts to cover flaws across different technologies. It would simply not have been possible to put this material together without the help of the following talented individuals: Car Bauer, Michael Collins, Daniel Cuthbert, Benjamin Delpy, David Fitzgerald, Rob Fuller, Chris Gates, Dane Goodwin, Robert Hurlbut, David Litchfield, HD Moore, Ivan Ristić, Tom Ritter, Andrew Ruef, and Frank Thornton.

1 For an overview of Project Zero, see Andy Greenberg’s “‘Meet Project Zero,’ Google’s Secret Team of Bug-Hunting Hackers”, Wired, July 15, 2014.

2 Ormandy described flaws affecting FireEye and Sophos products in “FireEye Exploitation: Project Zero’s Vulnerability of the Beast” and “Sophail: Applied Attacks Against Sophos Antivirus”, respectively. In addition, he tweeted about a Kaspersky exploit, and identified issues within Symantec and Trend Micro.

3 See Daniel J. Bernstein’s “Making Sure Crypto Stays Insecure” and watch Matthew Green’s TEDx talk “Why the NSA Is Breaking Our Encryption—And Why We Should Care”.

4 See the IETF RFC website.

5 See the MITRE CVE website.

6 To perform a keyword search, see http://bit.ly/2bfCqgR.

7 Karen Scarfone et al., “Technical Guide to Information Security Testing and Assessment”, National Institute of Standards and Technology, September 2008.

8 See “CHECK Fundamental Principles”, National Cyber Security Centre, October 23, 2015.

9 For details on this standard, see http://www.pentest-standard.org.

This chapter introduces the underlying economic principles behind computer network exploitation and defense, describing the current state of affairs and recent changes to the landscape. To realize a defendable environment, you must adopt a proactive approach to security—one that starts with assessment to understand your exposure. Many different flavors of assessment exist, from static analysis of a given application and its code to dynamic testing of running systems. I categorize the testing options here, and list the domains that this book covers in detail.

I started work on the first edition of this book almost 20 years ago, before computer network exploitation was industrialized by governments and organized criminals to the scale we know today. The zero-day exploit sales business was yet to exist, and hackers were the apex predator online, trading warez over IRC.

The current state of affairs is deeply concerning. Modern life relies heavily on computer networks and applications, which are complex and accelerating in many directions (think cloud applications, medical devices, and self-driving cars). Increasing consumer uptake of flawed products introduces vulnerability.

The Internet is the primary enabler of the global economic system, and relied on for just about everything. An International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) study predicted that total loss of Internet service in a country would lead to a failure of the food supply chain within three days.1

Victims of attack often realize acute negative economic impact. In 2009, the Stuxnet worm sabotaged an Iranian uranium enrichment facility in Natanz, reducing operational capacity by 30 percent for a period of months.2 In 2012, the world’s most valuable company, Saudi Aramco, suffered a malware outbreak that paralyzed the company for a 10-day period.3 Crippling attacks have continued into 2015 and 2016, as Sony Pictures Entertainment and the Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center suffered outages.4

A glaring gap exists between resourceful adversaries and those tasked with protecting computer networks. Thanks to increasing workforce mobility, adoption of wireless technologies, and cloud services, the systems of even the most security-conscious organizations, including Facebook,5 can be commandeered. To make matters worse, critical flaws have been uncovered in the very technologies and libraries we use to provide assurance through cryptography, including:

RSA BSAFE, using the flawed Dual_EC_DRBG algorithm by default6

The OpenSSL 1.0.1 heartbeat extension information leak7

Defendable networks exist, but are often small, high-assurance enclaves built by organizations within the defense industrial base. Such enclaves are tightly configured and monitored, running trusted operating systems and evaluated software. Many also use hardware to enforce one-way communication between particular system components. These hardened environments are not unassailable, but can be effectively defended through active monitoring.

The networks most at risk are those with a large number of elements. Multiple entry points increase the potential for compromise, and risk management becomes difficult. These factors create the defender’s dilemma—by which a defender must ensure the integrity of an entire system, but an attacker only needs to exploit a single flaw.

Adversaries who actively compromise computer systems include state-sponsored organizations, organized criminals, and amateur enthusiasts. Benefiting from deeper resources than the other groups combined, state-sponsored attackers have become the apex predator online.

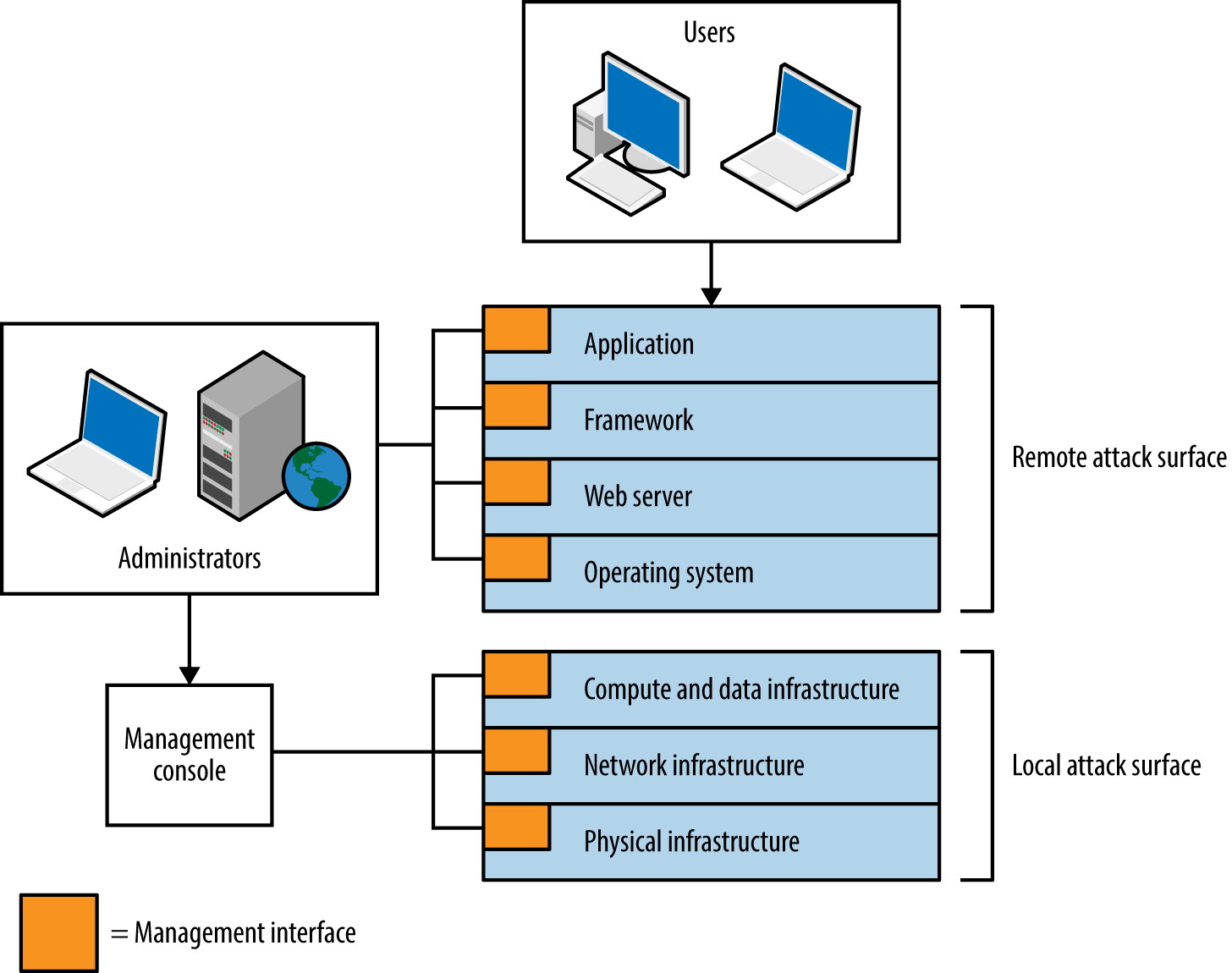

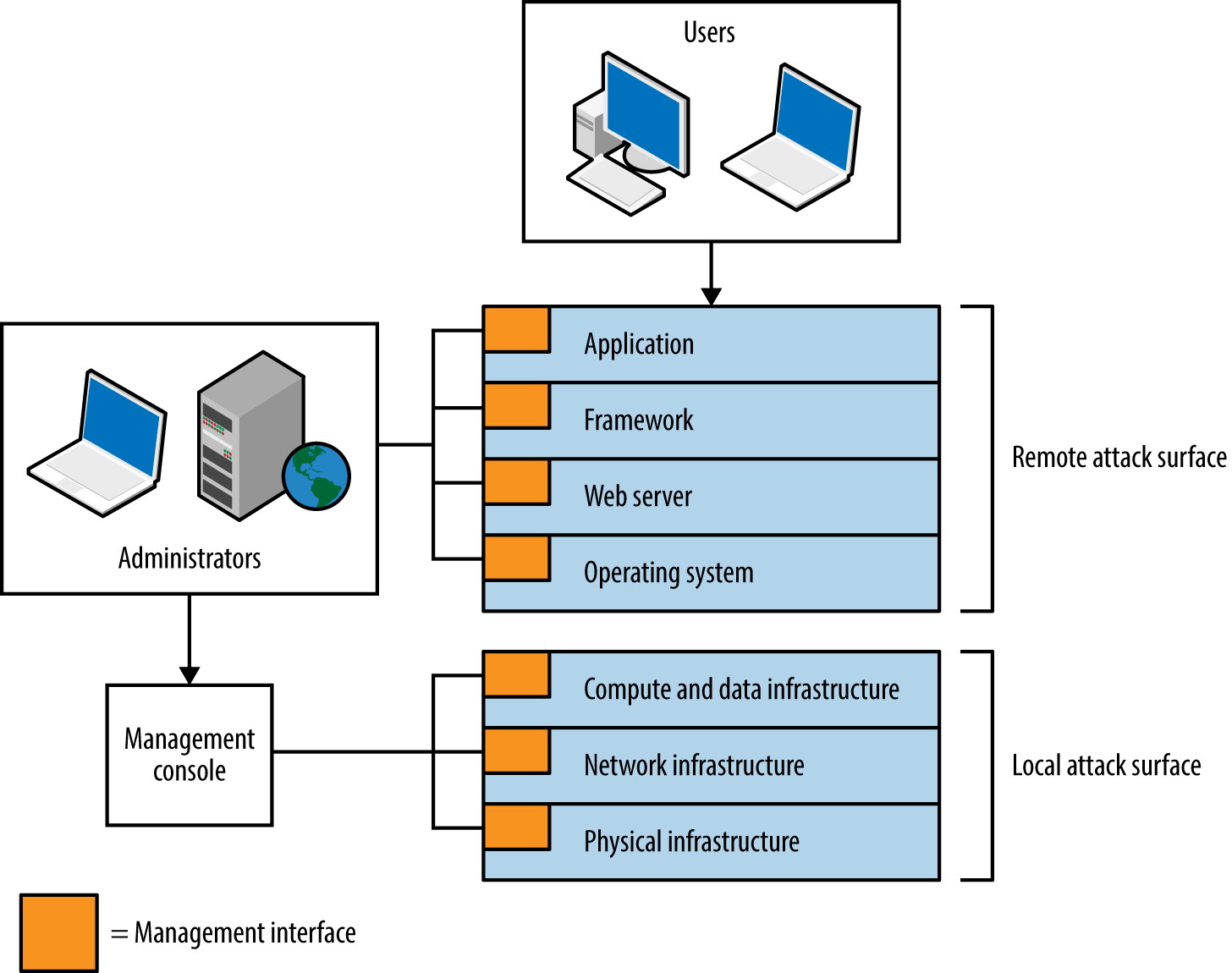

Upon understanding attack surface, you can begin to quantify risk. The exposed attack surfaces of most enterprises include client systems (e.g., laptops and mobile devices), Internet-based servers, web applications, and network infrastructure (e.g., VPN devices, routers, and firewalls).

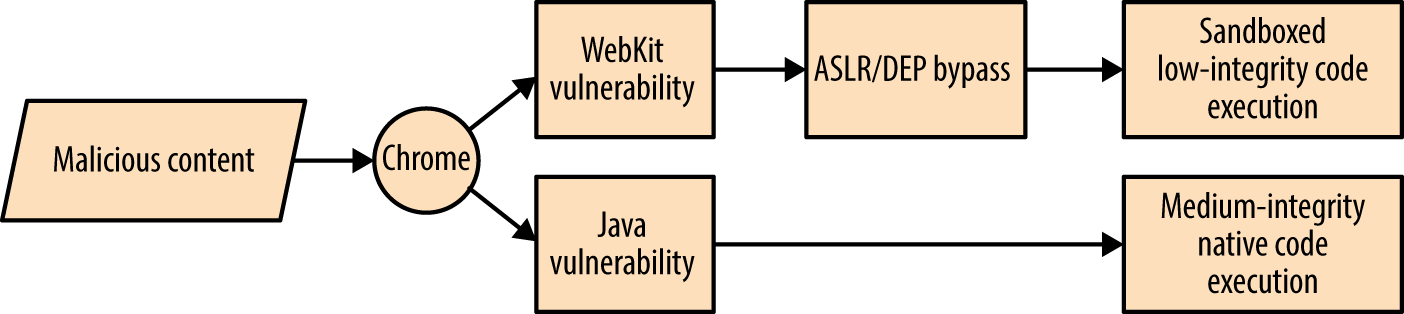

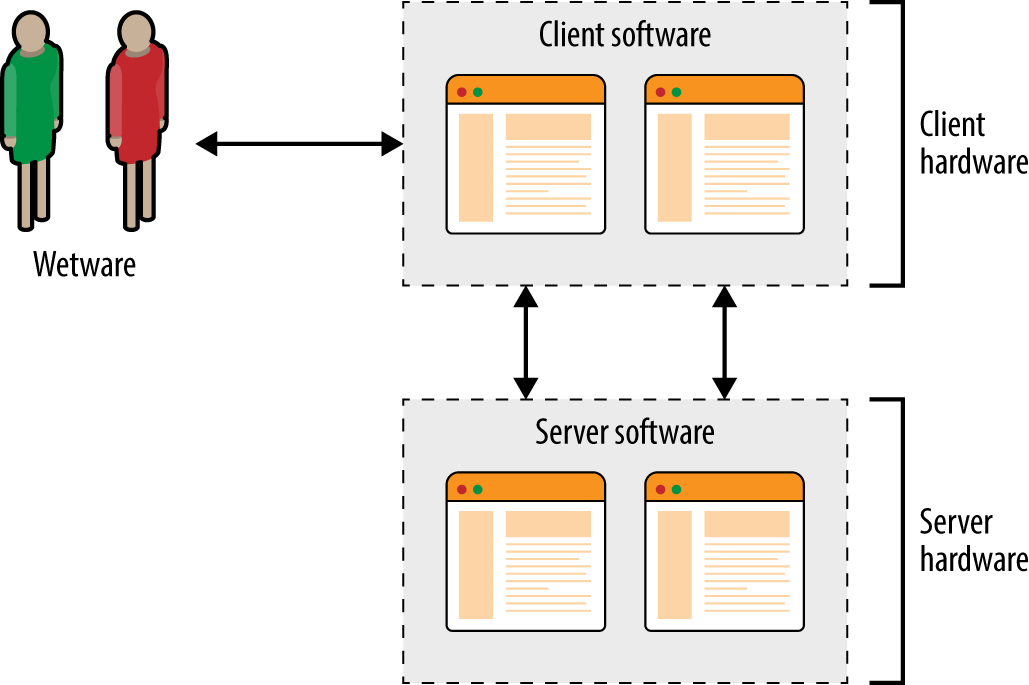

Desktop applications and client software packages (e.g., Microsoft Office; web browsers, including Google Chrome; and utilities such as PuTTY) can be attacked directly by an adversary with network access, or indirectly by an attacker sending malicious content to be parsed (such as a crafted Microsoft Excel file).

To demonstrate the insecurity of client software packages, you only need to look at the results of Pwn2Own competitions. In 2014, the French security firm VUPEN8 won $400,000 after successfully exploiting Microsoft Internet Explorer 11, Adobe Reader XI, Google Chrome, Adobe Flash, and Mozilla Firefox on a 64-bit version of Windows 8.1. The company used a total of 11 distinct zero-day exploits to achieve its goals.9

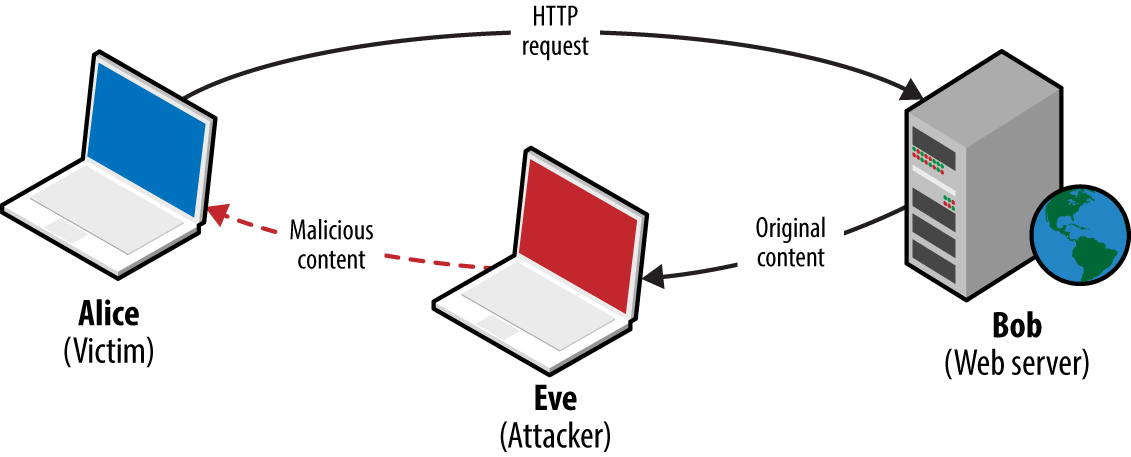

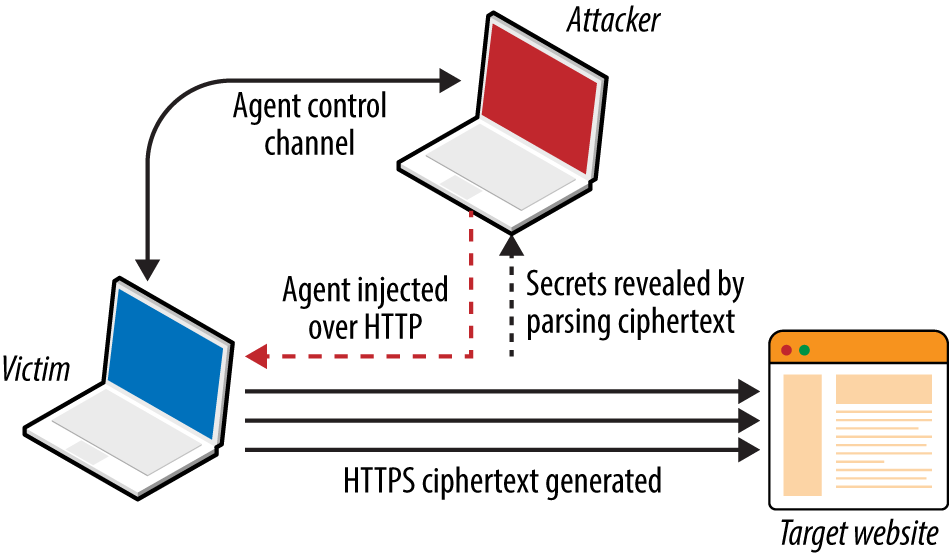

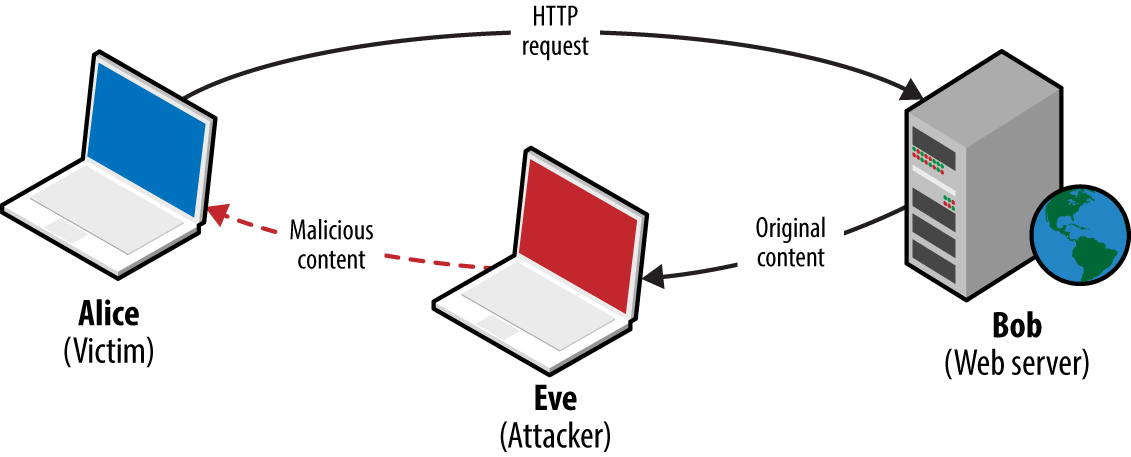

Attackers with network access commonly exploit browser flaws to target high-value assets (e.g., systems administrators of organizations such as OPEC10) by injecting malicious content into a plaintext HTTP session via man-in-the-middle (MITM), as demonstrated by Figure 1-1.

Server software has not fared any better, thanks to increasing layers of abstraction and adoption of emerging technologies. The Rails application server and Nginx reverse proxy both suffered from severe code execution flaws in 2013, as follows:

Rails 2.3 and 3.x Action Pack YAML deserialization flaw11

Nginx 1.3.9 to 1.4.0 chunked encoding stack overflow12

The Nginx chunked encoding flaw is similar to that found by Neel Mehta in 2002 within the Apache HTTP Server13—demonstrating how known issues appear within new packages as developers fail to look backward.

Vulnerability within web applications stems from additional feature support and increasing exposure of APIs between components. One particularly severe class of problem is XML external entity (XXE) parsing, by which malicious content is presented to a web application and sensitive content returned. In 2014, researchers uncovered multiple XXE parsing flaws within the Google production environment. In one case, XML content was uploaded to the Google Public Data Explorer utility,14 defining an external entity:

<!ENTITY % payload SYSTEM "file:///etc/"> <!ENTITY % param1 '<!ENTITY % internal SYSTEM "%payload;" >' > %param1; %internal;Example 1-1 shows the malicious XML parsed server-side, revealing the contents of /etc/.

XML parsing error. Line 2, Column: 87: no protocol: bash.bashrc bashrc bashrc.google borgattrs.d borgattrs-msv.d borgletconf.d capabilities chroots chroots.d container.d cron cron.15minly cron.5minly cron.d cron.daily cron.hourly cron.monthly cron.weekly crontab csh.cshrc csh.login csh.logout debian_version default dpkg fsck.d fstab google googleCA googlekeys groff group host.conf hosts hotplug init.d inittab inputrc ioctl.save iproute2 issue issue.net kernel lilo.conf lilo.conf.old localbabysitter.d localbabysitter-msv.d localtime localtime.README login.defs logmanagerd logrotate.conf logrotate.d lsb-base lsb-release magic magic.mime mail mail.rc manpath.config mced mime.types mke2fs.conf modprobe.conf modprobe.d motd msv-configuration msv-managed mtab noraidcheck nsswitch.conf passwd passwd.borg perfconfig prodimage-release-notes profile protocols rc.local rc.machine rc0.d rc1.d rc2.d rc3.d rc4.d rc5.d rc6.d rcS.d resolv.conf rpc securetty services shadow shells skel ssdtab ssh sudoers sysconfig sysctl.conf sysctl.d syslog.d syslog-ng_configs_src syslog-ng.conf sysstat tidylogs.d vim wgetrc

One way to understand attack surface within a computer system is to consider the exposed logic that exists. Such logic could be part of an Internet-accessible network service (e.g., support for compression or chunked encoding within a web server), or a parsing mechanism used by a client (such as PDF rendering). Locally within operating systems, privileged kernel components and device drivers expose logic to running applications.

Attack surface is logic (usually privileged) that can be manipulated by an adversary for gain—whether revealing secrets, facilitating code execution, or inducing denial of service. Exposed logic is targeted by network-based attackers in two ways:

Directly via a vulnerable function within an exposed network service.

Indirectly, such as a parser running within a client system that is provided with malicious material through MITM attack, email, messaging, or other means.

A useful example is the GNU bash command execution flaw known as shellshock.15 Many applications within Unix-based systems (including Linux and Apple OS X) use the bash command shell as a broker to perform low-level system operations. In 1989, a flaw was introduced which meant that arbitrary commands could be executed by passing malicious environment variables to bash. The issue was uncovered 25 years later by Stéphane Chazelas.16

To exploit the flaw, an attacker must identify a path through which user-controlled content is passed to the vulnerable command shell. Two examples of remotely exploitable paths and preconditions are as follows:

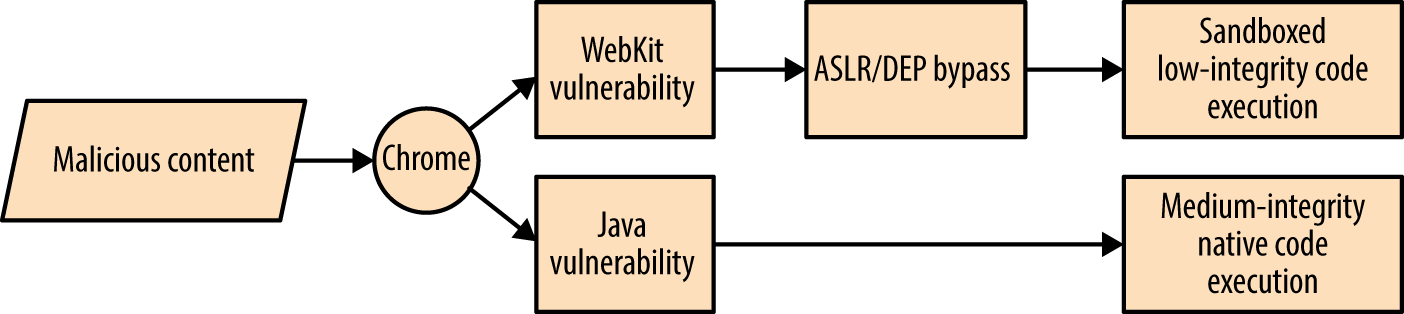

The security research industry is built upon the exploitation of exposed logic to perform a valuable action. Most browser exploits rely on the chaining of multiple defects to bypass security protections and execute arbitrary code.

In 2012, renowned hacker Pinkie Pie developed a Google Chrome exploit that used six distinct flaws to achieve code execution.19 He found exploitable conditions within components including Chrome prerendering, GPU command buffers, the IPC layer, and extensions manager.

Low-level software assessment is an art form, by which a relatively small number of skilled researchers uncover subtle defects in software and chain them together for gain. During each iterative testing step, the available attack surface is evaluated to identify risks to the larger system.

To map and test the exposed logic paths of a system, organizations adopt a variety of approaches. In the marketplace today, there are many vendors providing static and dynamic testing services, along with analysis tools used to identify potential risks and vulnerabilities.

Auditing application source code, server configuration, infrastructure configuration, and architecture might be time consuming, but it is one of the most effective ways of identifying vulnerabilities in a system. A drawback of static analysis within a large environment is the cost (primarily due to the sheer volume of material produced by these tools, and the cost of tuning out false positives), and so it is important to scope testing narrowly and prioritize efforts correctly.

Technical audit and review approaches include:

Design review

Configuration review

Static code analysis

Less technical considerations might include data classification and labeling, review of the physical environment, personnel security, as well as education, training, and awareness.

Review of system architecture involves first understanding the placement and configuration of security controls within the environment (whether network-based controls such as ACLs or low-level system controls such as sandboxes), evaluating the efficacy of those controls, and where applicable, proposing changes to the architecture.

Common Criteria20 is an international standard for computer security certification, applicable to operating systems, applications, and products with security claims. Seven assurance levels exist, from EAL1 (functionally tested) through EAL4 (methodically designed, tested, and reviewed) to EAL7 (formally verified design and tested). Many commercial operating systems are typically evaluated at EAL4, and operating systems that provide multilevel security are evaluated at a minimum of EAL4. Other programs exist, including the UK’s CESG CPA scheme.

Formally verifying the design of a system can be a costly exercise. Often, a cursory architecture review by an experienced security professional will highlight potential pitfalls and issues that should be mitigated, such as poor network segmentation, or insufficient protection of data in-transit.

Low-level audit of system components can include review of infrastructure (i.e., firewalls, routers, switches, storage, and virtualization infrastructure), server and appliance operating system configuration (e.g., Windows Server, Linux, or F5 Networks hardware), and application configuration (such as Apache or OpenSSL server configuration).

Organizations such as NIST, NSA, and DISA provide checklists and configuration guidelines for operating systems, including Apple OS X, Microsoft Windows, and Linux. These resources are available online:

NSA’s “IA Guidance”

By performing gap analysis against these standards, it is possible to identify shortcomings in operating system configuration, and work to ensure a uniform hardened configuration across an environment. Bulk vulnerability scanners (including Rapid7 Nexpose) include DISA STIG scan policies, and so identification of gaps is straightforward through authenticated testing.

NIST and Wikipedia maintain lists of code analysis tools, as follows:

Wikipedia’s “List of Tools for Static Code Analysis”

Such tools identify common flaws in software written in languages such as C/C++, Java, and Microsoft .NET. The HP Fortify team published a taxonomy of software security errors21 that can be identified through static code analysis, including input validation and representation, API abuse, flawed security features, time and state vulnerabilities, and error handling flaws. Chapter 3 discusses these categories in detail.

Static code analysis tools require tuning to reduce noise within their results and focus findings around accessible code paths (e.g., flaws that can be practically exploited). Such low-level static analysis is suited to critical system components, as the cost of reviewing the output can be considerable.

Exposed logic is assessed through dynamic testing of running systems, including:

Network infrastructure testing

Web application testing

Web service testing (e.g., APIs supporting mobile applications)

Internet-based social engineering

As testing is undertaken from the perspective of an assailant (e.g., an unauthenticated network-based attacker, an authenticated application user, or a mobile client), findings are aligned with legitimate threats to the system.

Scanning tools (e.g., Nmap, Nessus, Rapid7 Nexpose, and QualysGuard), map and assess the network attack surface of an environment for known vulnerabilities. Manual assessment cycles are then applied to investigate the attack surface further, and evaluate accessible network services.

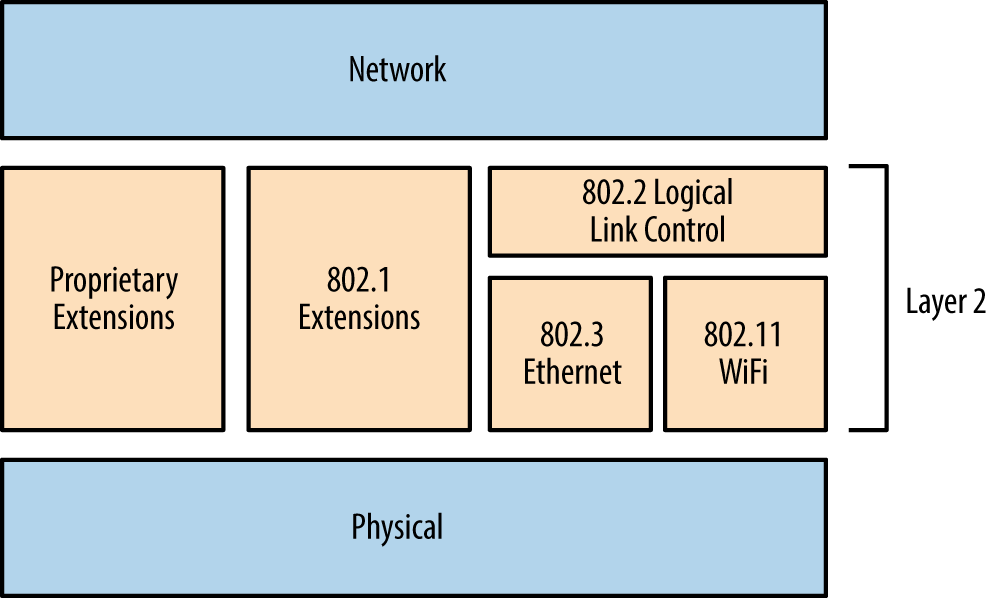

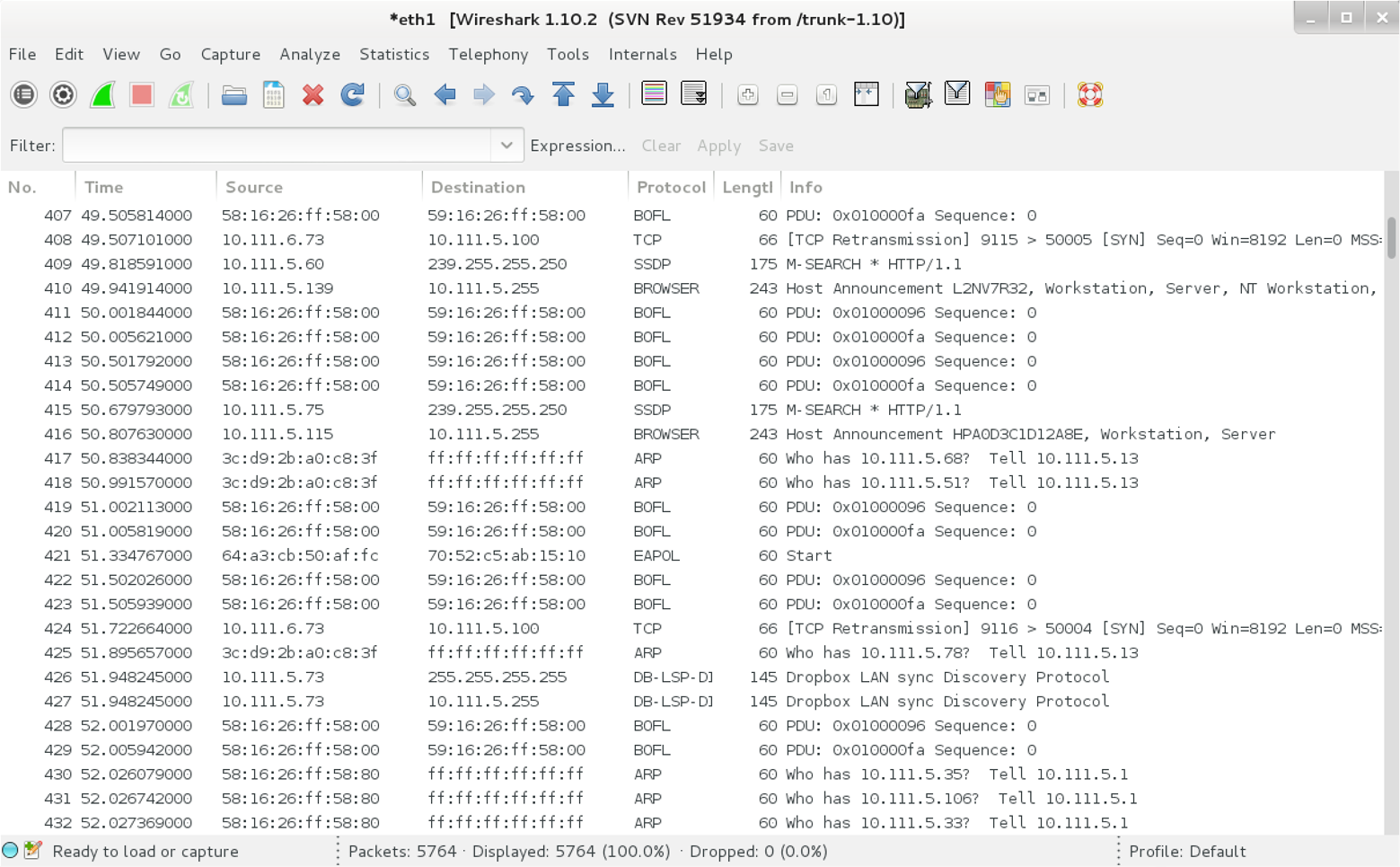

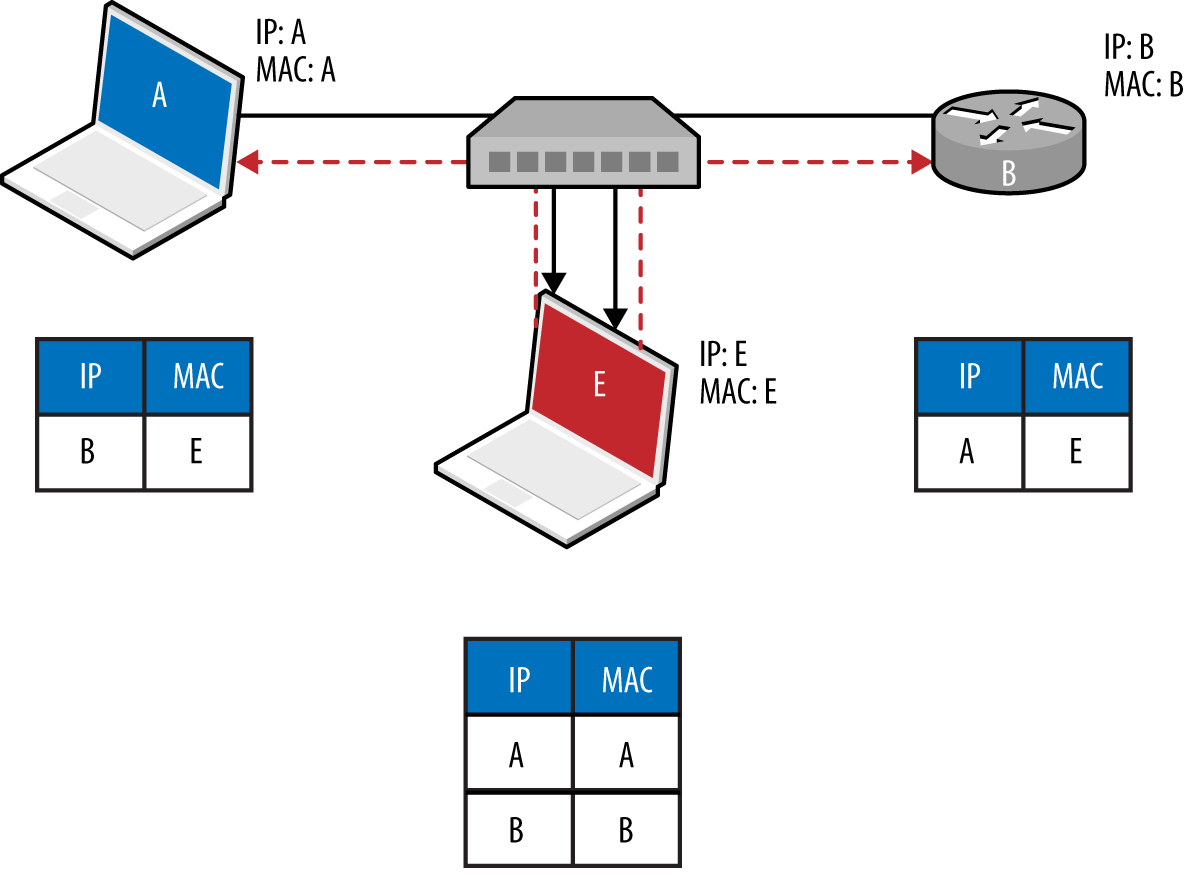

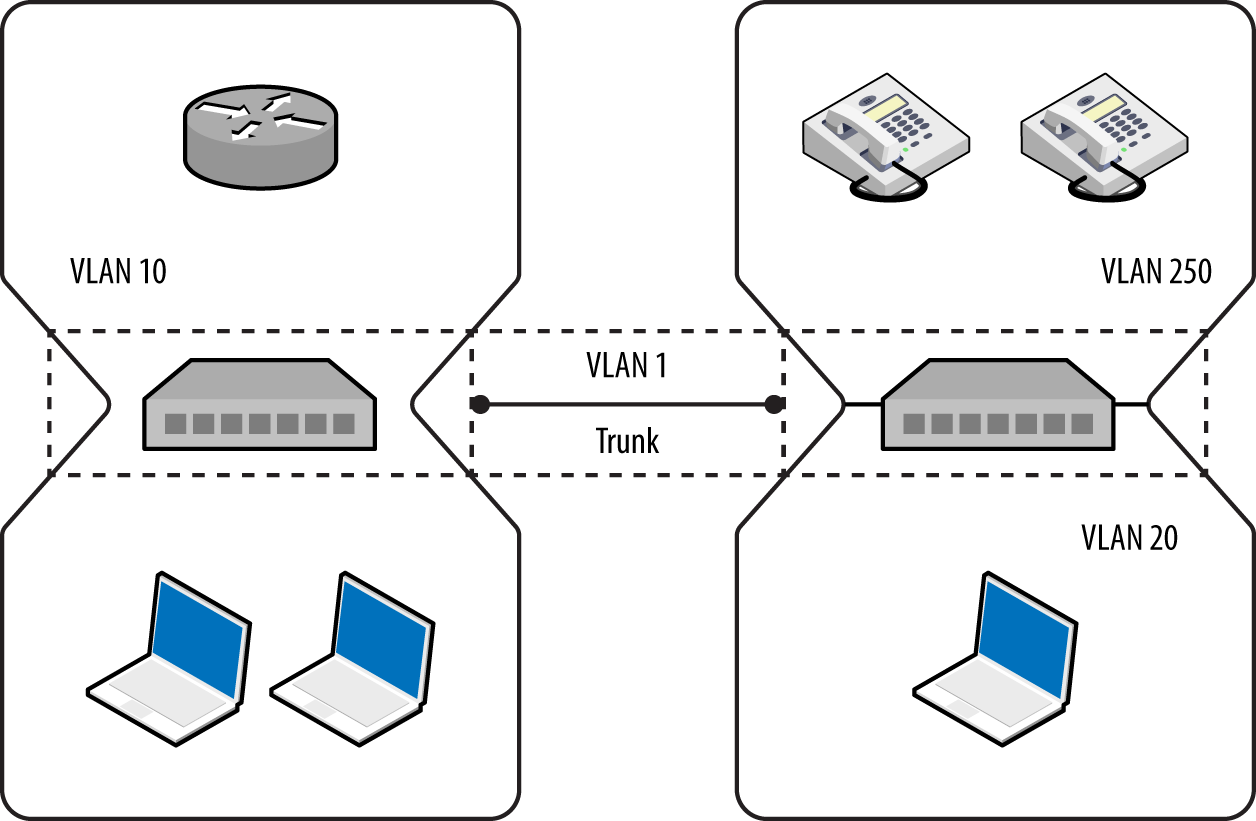

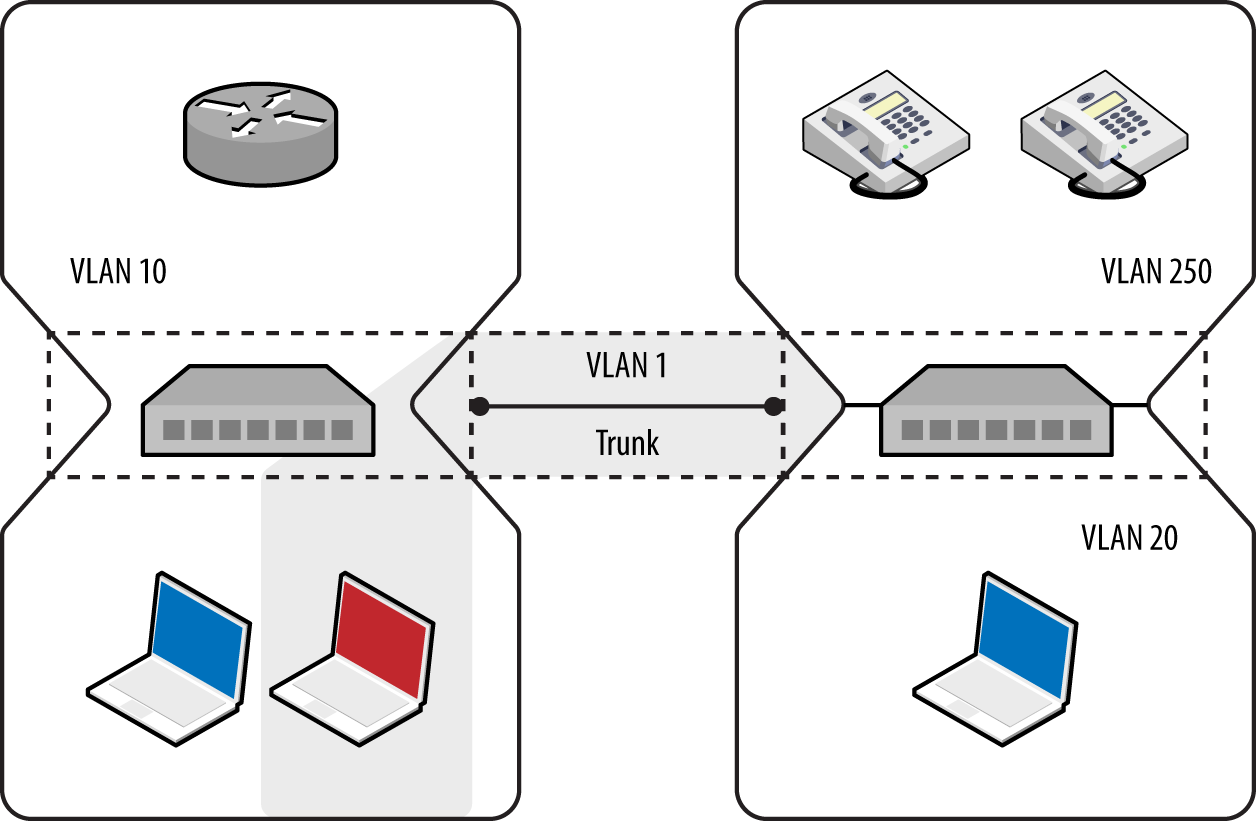

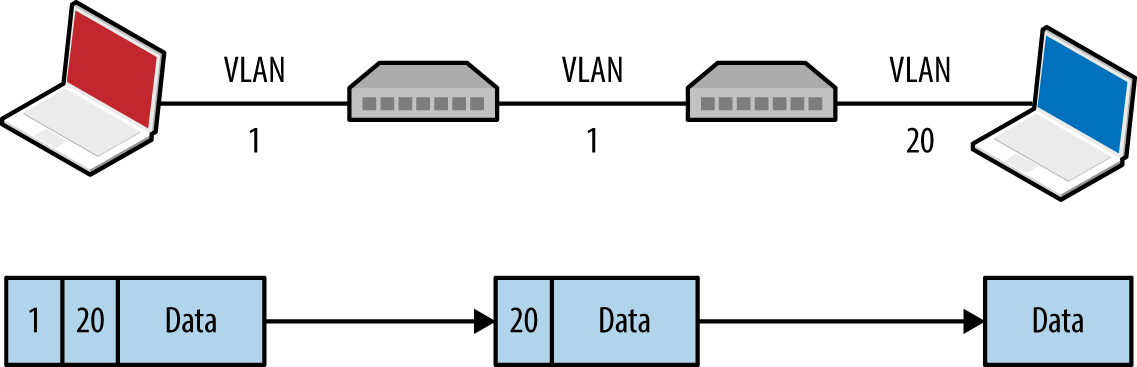

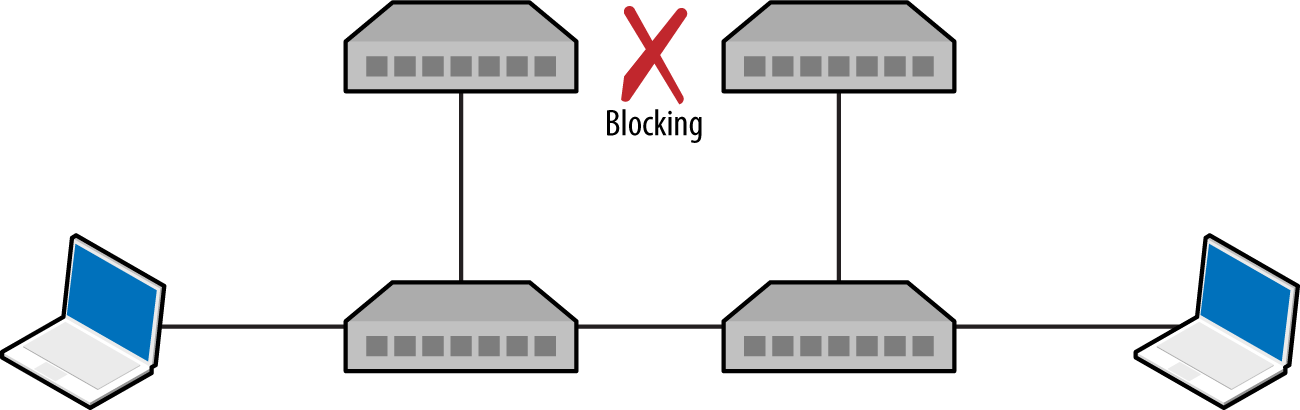

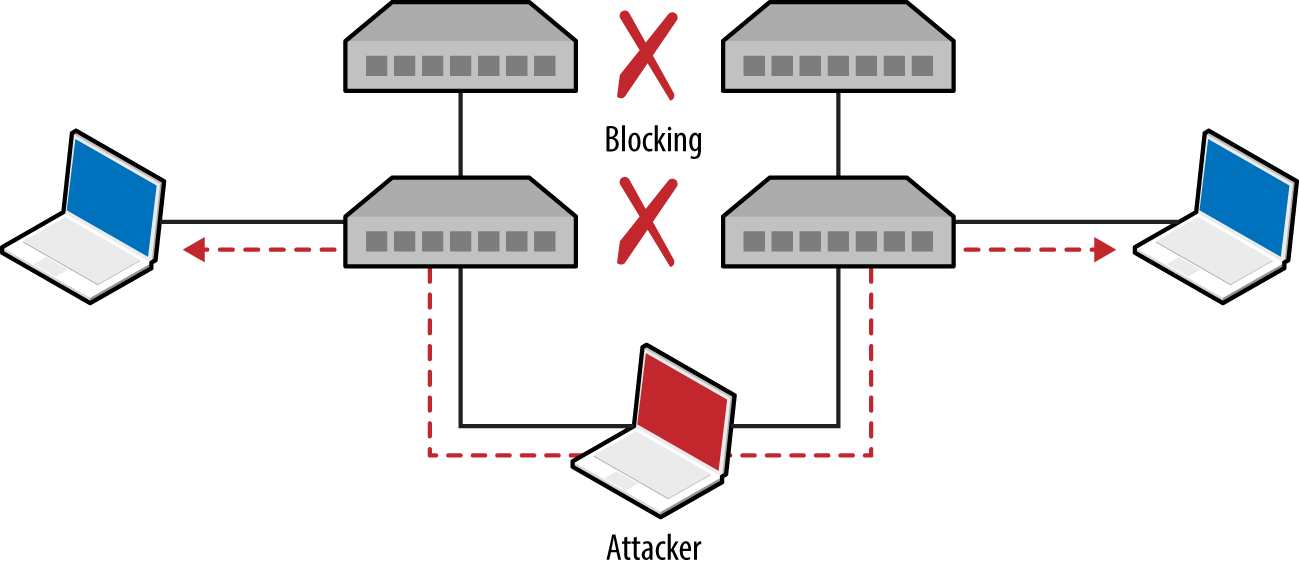

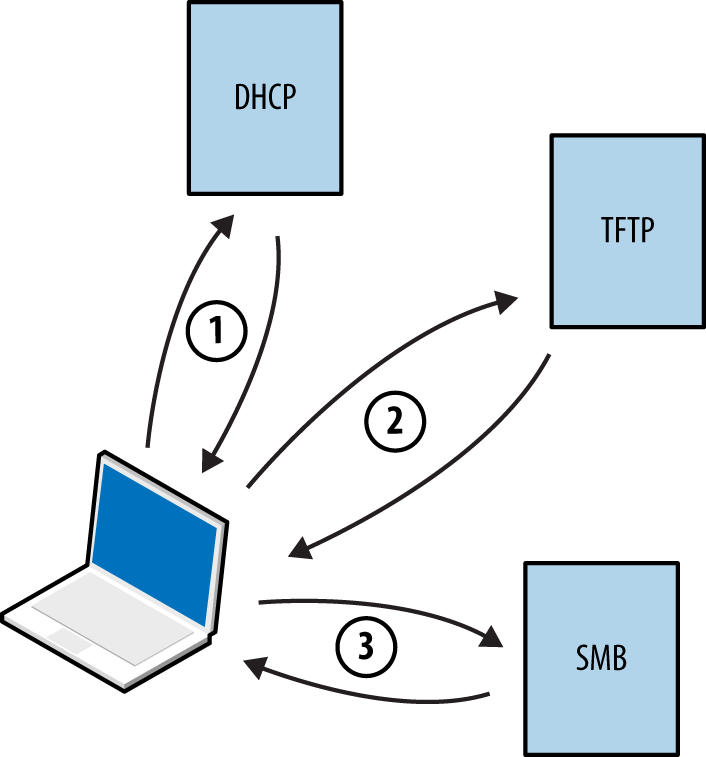

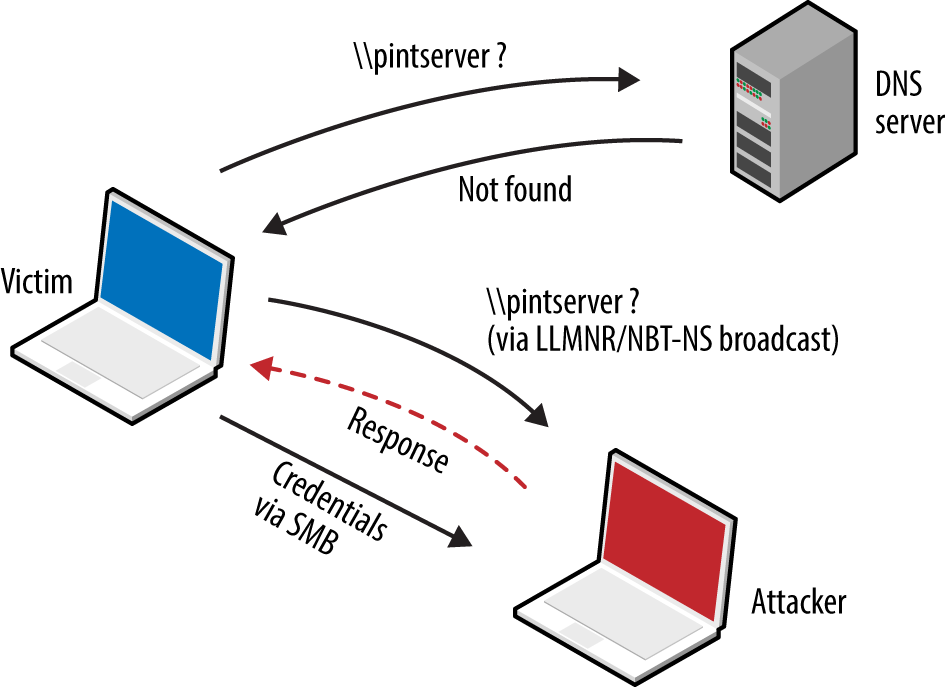

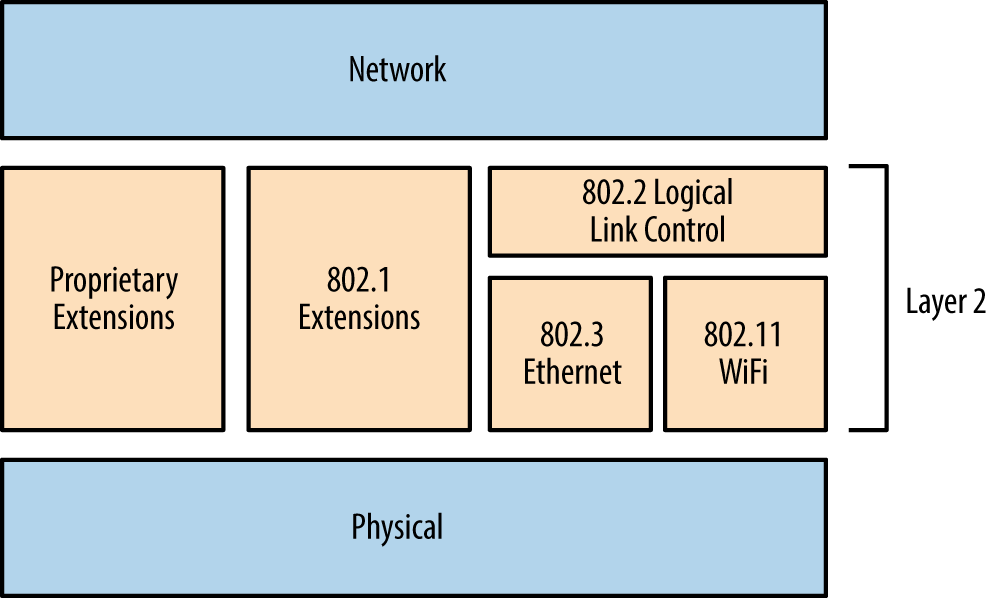

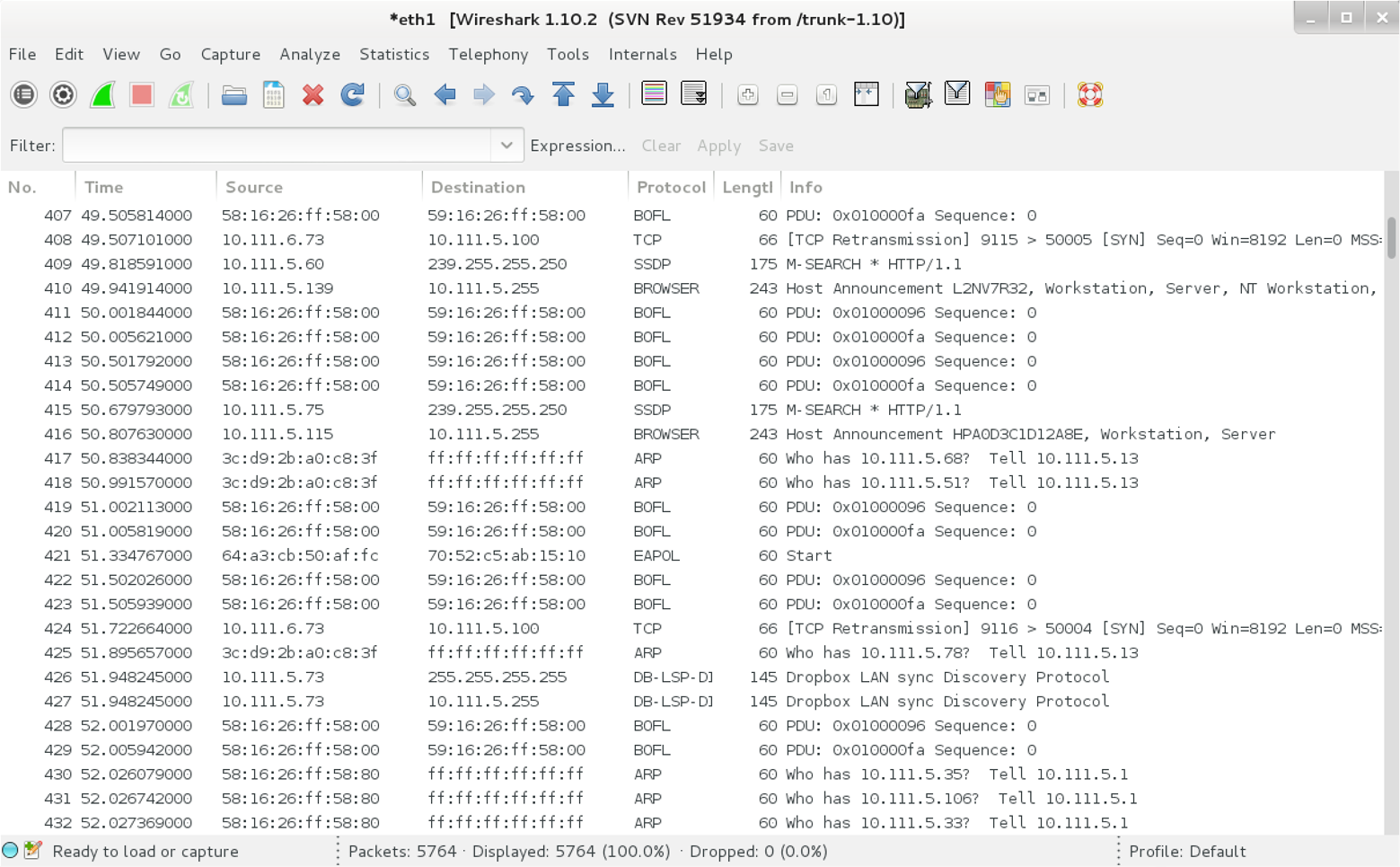

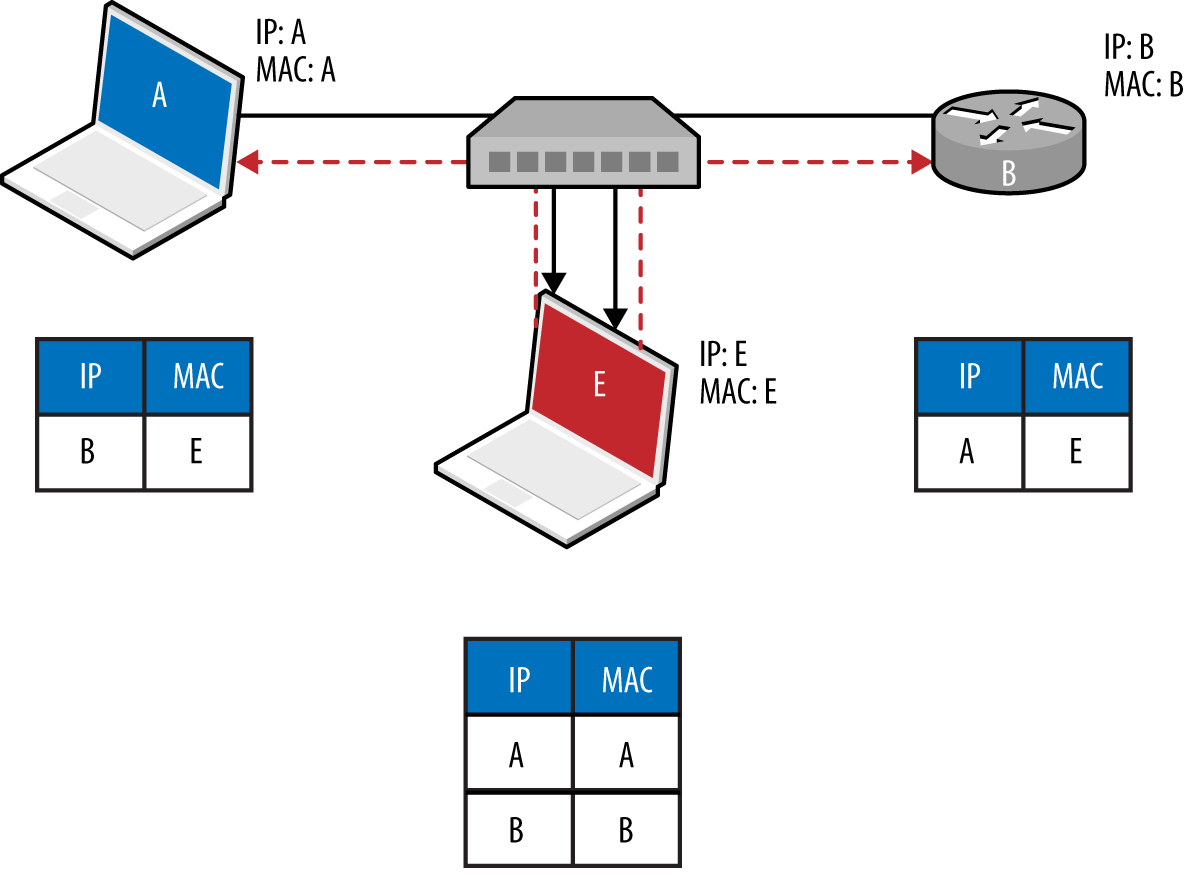

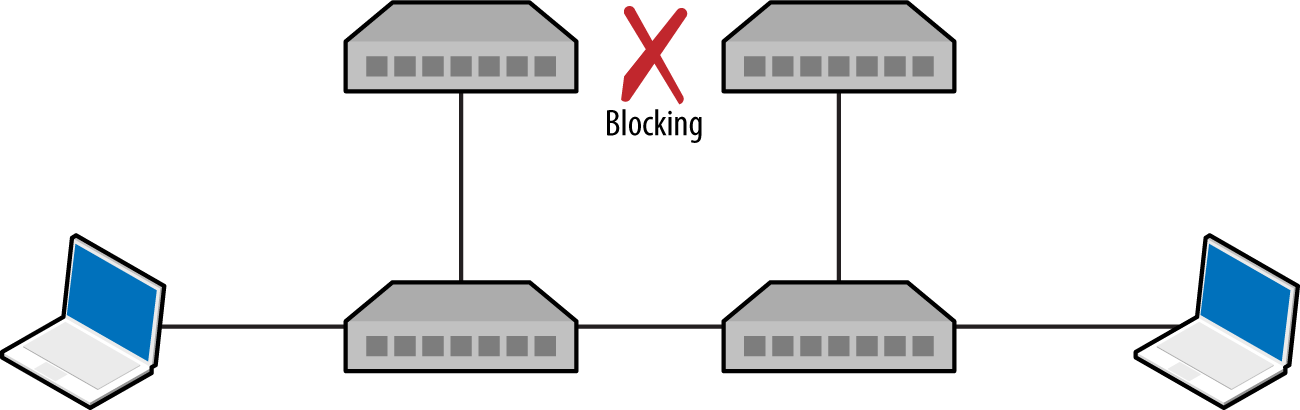

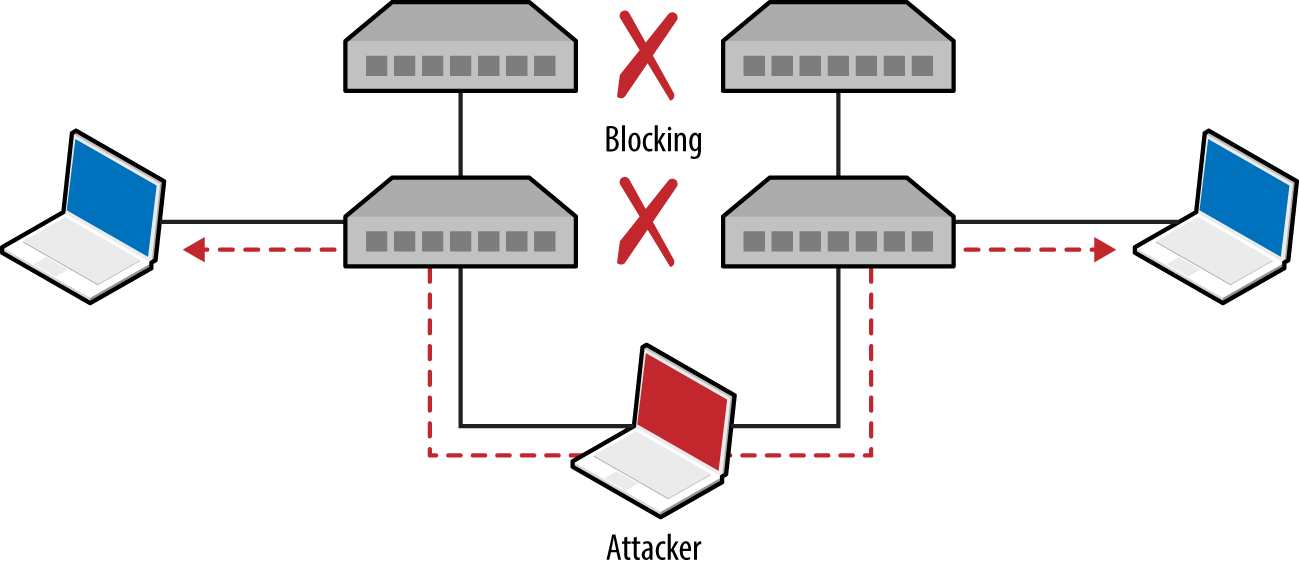

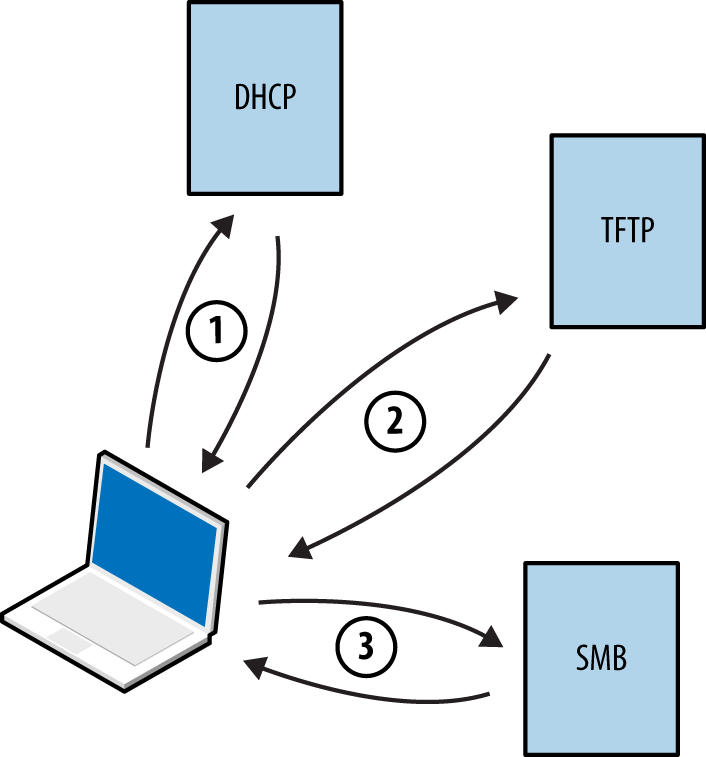

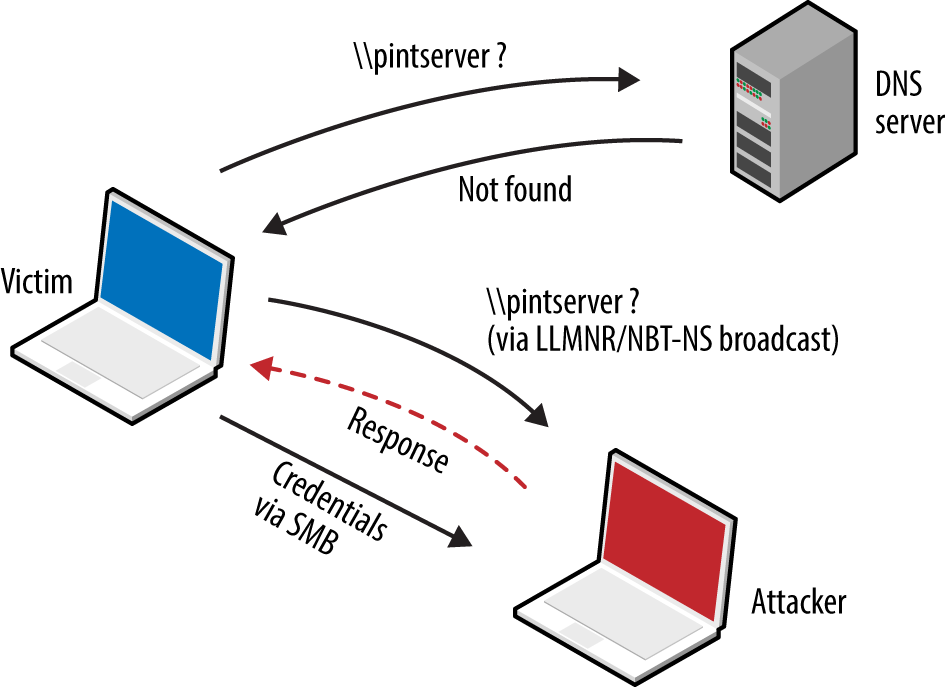

Internal network testing can also be undertaken to identify and exploit vulnerabilities across OSI Layers 2 and 3 (such as ARP cache poisoning and 802.1Q VLAN hopping). Chapter 5 discusses network discovery and assessment techniques that should be adopted locally to identify weaknesses.

Web application logic is commonly assessed in an unauthenticated or authenticated fashion. Most organizations opt for authenticated testing of applications, emulating assailants with valid credentials or session tokens who seeks to elevate their privileges.

The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) Top 10 is a list of common web application flaws. Tools that can reliably test for such flaws include Burp Suite, IBM Security AppScan, HP WebInspect, and Acunetix. These tools provide testing capabilities that let organizations broadly scan their exposed web application logic for common issues, including cross-site scripting (XSS), cross-site request forgery (CSRF), command injection session management flaws, and information leak bugs. Deep web application testing is out of scope for this book; however, Chapters 12 through 14 detail assessment of web servers and application frameworks.

During 2012 and 2013, I performed incident response and forensics work for companies that had fallen victim to attack by Alexsey Belan. In each case, he compromised internal web applications to escalate privileges and move laterally. This highlights the importance of testing and hardening web applications within your environment that are not Internet-accessible.

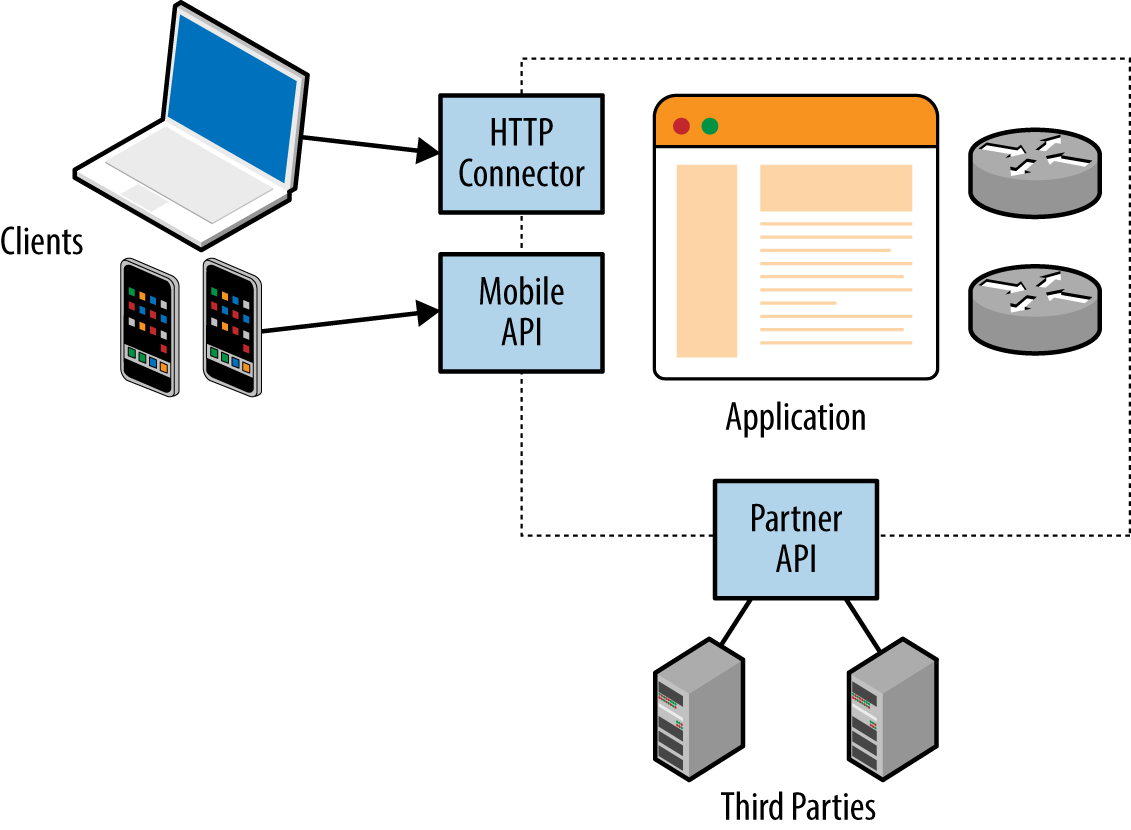

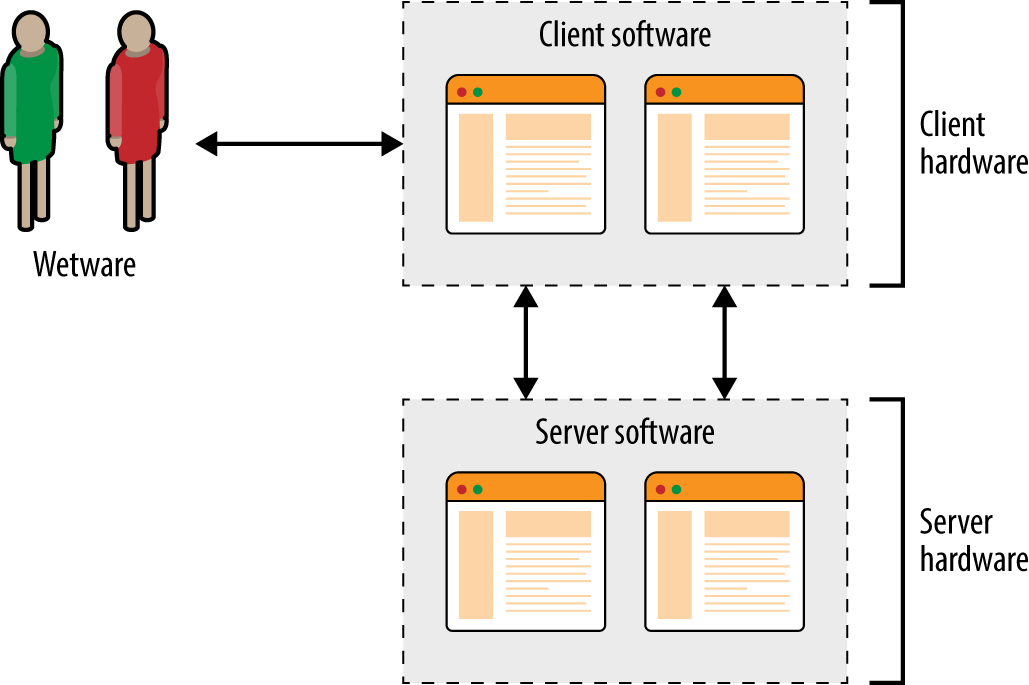

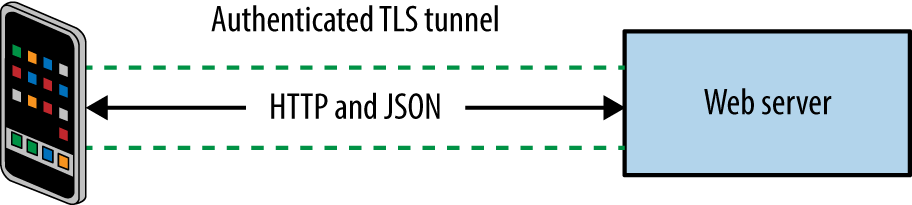

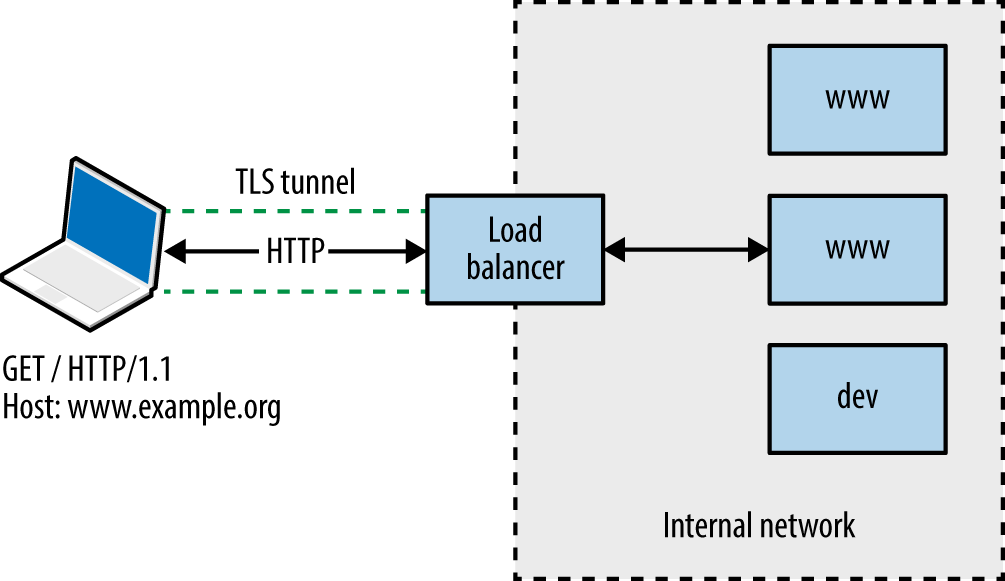

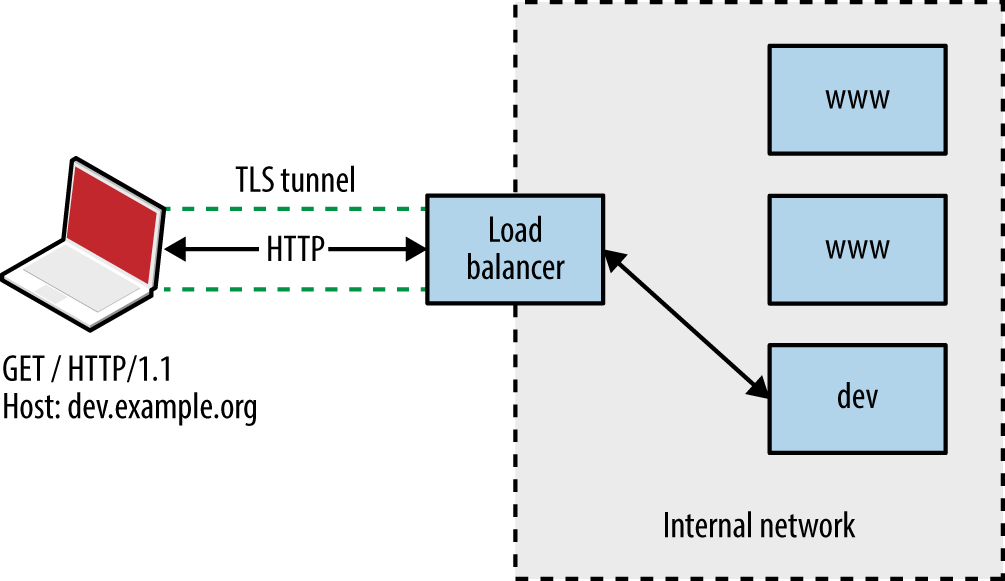

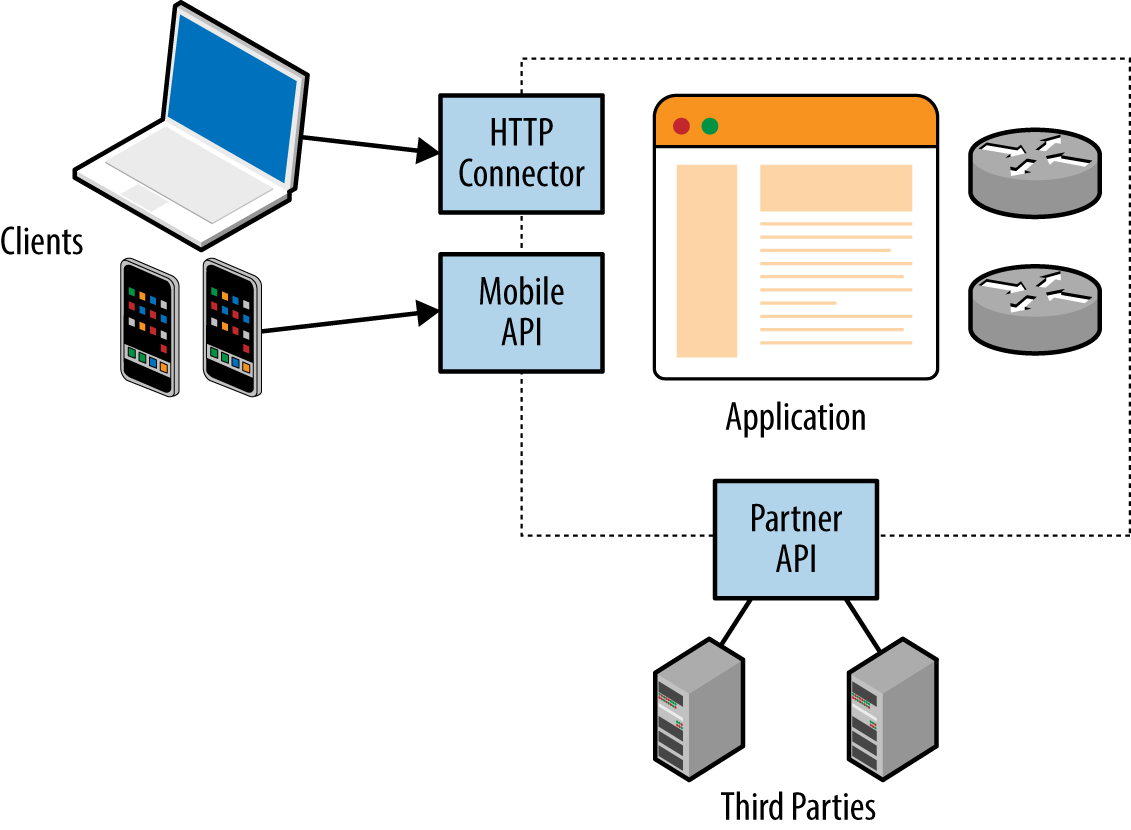

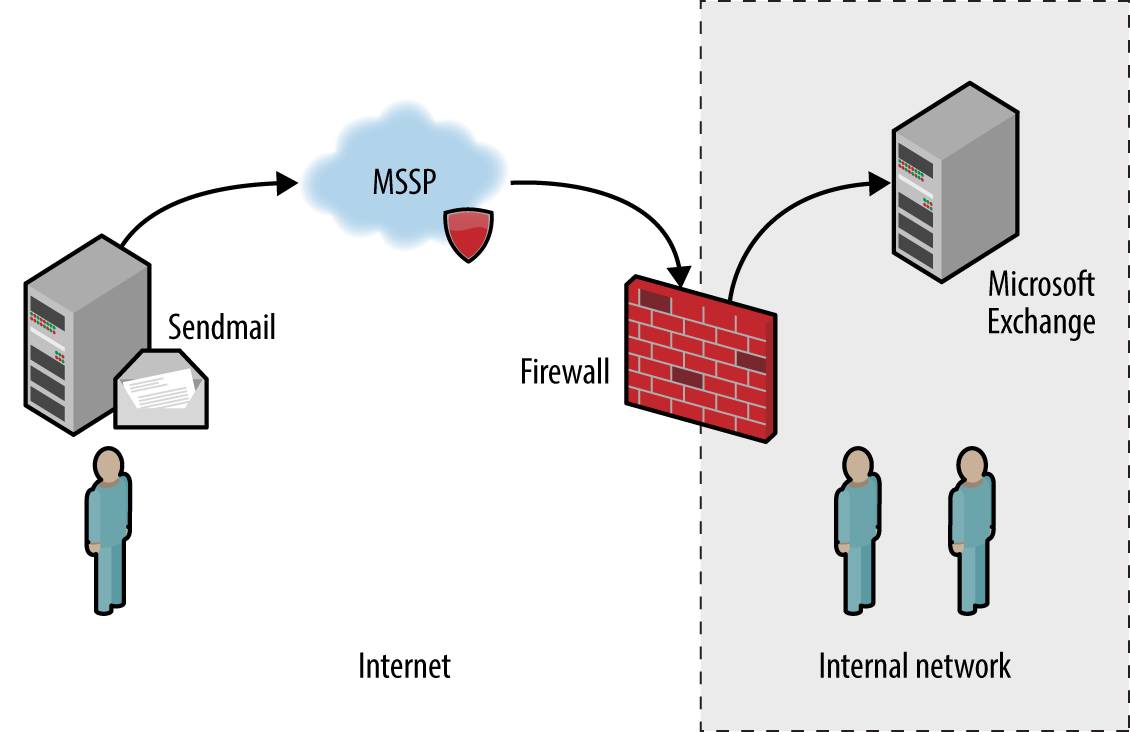

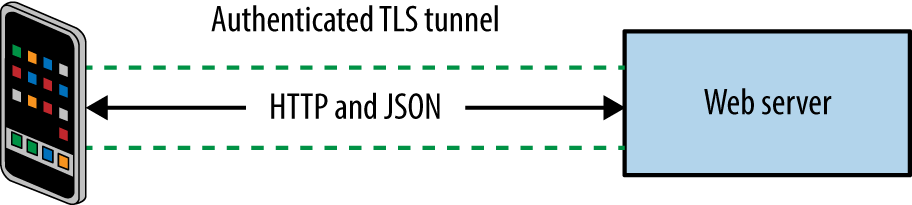

Mobile and web applications use server-side APIs and perform an increasing amount of processing on the client system. APIs are often exposed to end users (such as a user with a mobile online banking client), third parties (such as business partners or affiliates), and internal application components, as shown in Figure 1-2.

REST APIs are used in many applications that take advantage of mature HTTP functionality (including caching and keep-alive features). Web service testing involves using an attack proxy to analyze and manipulate messages and content flowing between the client and server endpoint. You also can undertake Active fuzzing of REST API services to identify security flaws.

During my career, some of the largest compromises I’ve accomplished during testing have come about through Internet-based social engineering. Two effective attack scenarios are as follows:

Configuring an Internet-based web server masquerading as a legitimate resource, and then emailing users with material including a link to the malicious page.

Sending malicious material (e.g., a crafted document to exploit Microsoft Excel or Adobe Acrobat Reader) directly to the user via email, messaging, or other means, from a seemingly trusted source, such as a friend or colleague.

I recently undertook an Internet-based spear phishing exercise against a financial services organization, involving a fake SSL VPN endpoint and instructions to log into the “new corporate VPN gateway” emailed to 200 users. Within two hours, 13 users had entered their Active Directory username, domain password, and two-factor authentication token value. Chapter 9 details phishing tactics and tools.

This book covers dynamic testing of network devices, operating systems, and exposed services in detail, but avoids static analysis and auditing topics. Web application testing is out of scope, along with Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP), and assessment of 802.11 wireless protocols. These three topics already fill entire books, including the following:

The Web Application Hacker’s Handbook, by Dafydd Stuttard and Marcus Pinto (Wiley, 2011)

Hacking Exposed Unified Communications & VoIP, by Mark Collier and David Endler (McGraw-Hill, 2013)

Hacking Exposed Wireless, by Johnny Cache, Joshua Wright, and Vincent Liu (McGraw-Hill, 2010)

1 Leena Ilmola-Sheppard and John Casti, “Case Study: Seven Shocks and Finland”, Innovation and Supply Chain Management 7, no. 3 (2013): 112–124.

2 Kim Zetter, “An Unprecedented Look at Stuxnet, the World’s First Digital Weapon”, Wired, November 3, 2014.

3 John Leyden, “Hack on Saudi Aramco Hit 30,000 Workstations, Oil Firm Admits”, The Register, August 29, 2012.

4 Peter Elkins, “Inside the Hack of the Century”, Fortune.com, June 25, 2015; Robert Mclean, “Hospital Pays Bitcoin Ransom After Malware Attack”, CNN Money, February 17, 2016.

5 Orange Tsai, “How I Hacked Facebook, and Found Someone’s Backdoor Script”, DEVCORE Blog, April 21, 2016.

6 Joseph Menn, “Secret Contract Tied NSA and Security Industry Pioneer”, Reuters, December 20, 2013.

7 See CVE-2014-0160.

8 In 2015, VUPEN ceased operations and its founders launched ZERODIUM.

9 Michael Mimoso, “VUPEN Discloses Details of Patched Firefox Pwn2Own Zero-Day”, Threatpost Blog, May 21, 2014.

10 SPIEGEL Staff, “Oil Espionage: How the NSA and GCHQ Spied on OPEC”, SPIEGEL ONLINE, November 11, 2013.

11 See CVE-2013-0156.

12 See CVE-2013-2028.

13 See CVE-2002-0392.

14 See http://examples.oreilly.com/networksa/tools/google-xxe.pdf.

15 See CVE-2014-6271.

16 Nicole Perlroth, “Security Experts Expect ‘Shellshock’ Software Bug in Bash to Be Significant”, New York Times, September 25, 2014.

17 Metasploit apache_mod_cgi_bash_env_exec module.

18 Metasploit dhclient_bash_env module.

19 Jorge Lucangeli Obes and Justin Schuh, “A Tale of Two Pwnies (Part I)”, Chromium Blog, May 22, 2012.

20 See ISO/IEC 15408.

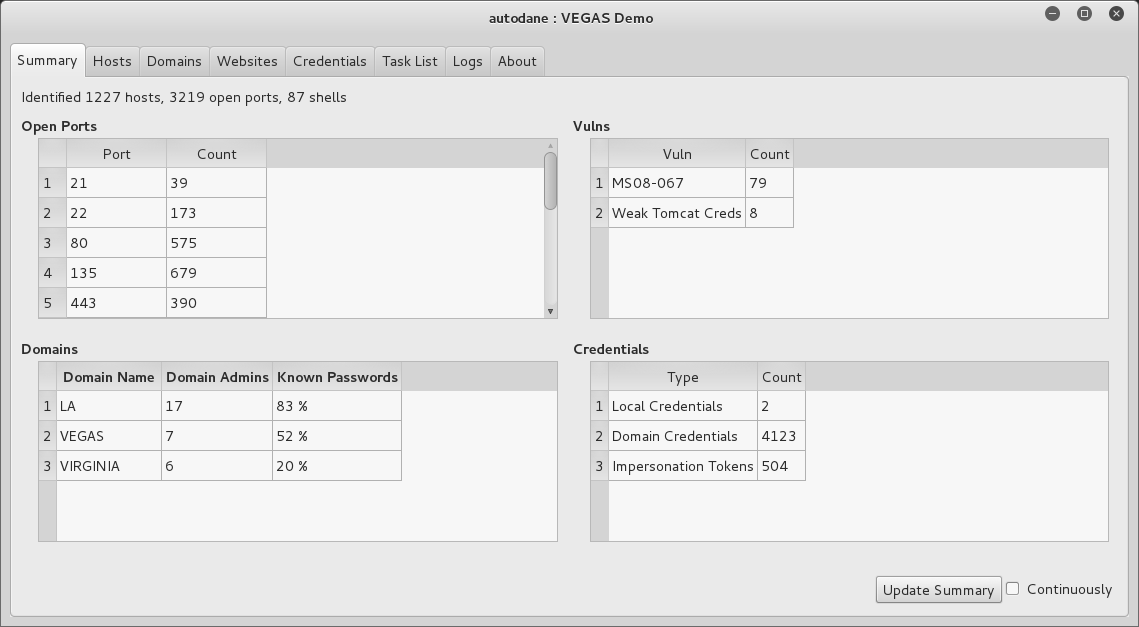

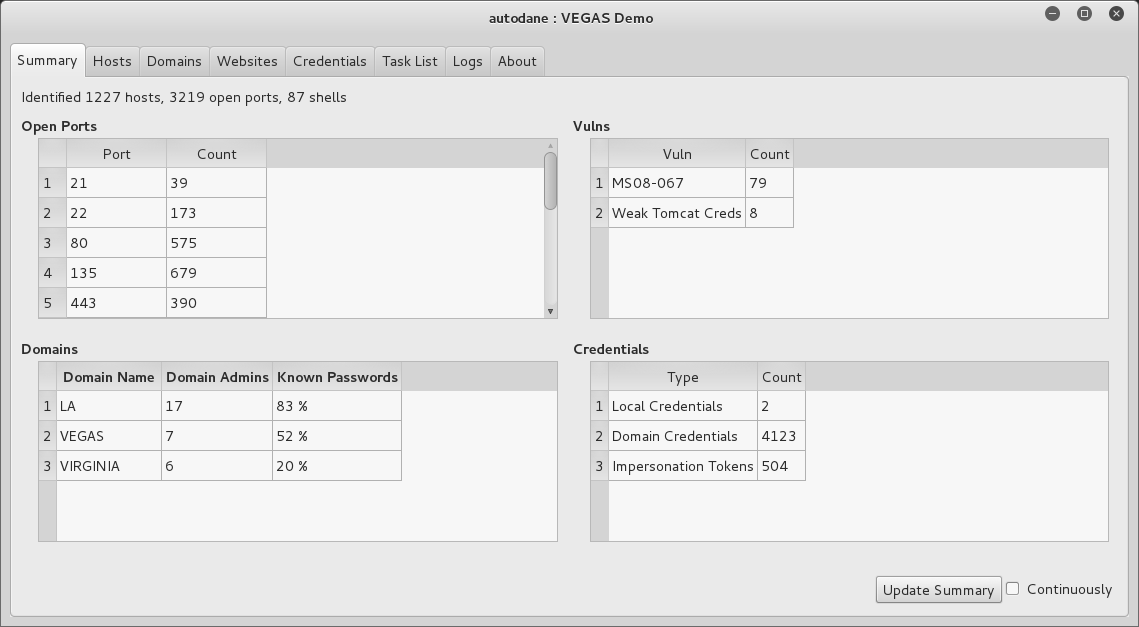

This chapter outlines my penetration testing approach and describes an effective testing setup. Many assessment tools run on Linux platforms, and Windows-specific utilities are required when attacking Microsoft systems. A flexible, virtualized platform is key. At Matta, we ran a program called Sentinel, through which we evaluated third-party testing vendors for clients in the financial services sector. Each vendor was ranked based on the vulnerabilities identified within the systems we had prepared. In a single test involving 10 vendors, we found that:

Two failed to scan all 65,536 TCP ports

Five failed to report the MySQL service root password of “password”

Some were evaluated multiple times. There seemed to be a lack of adherence to a strict testing methodology, and test results (the final report) varied depending on the consultants involved.

During testing, it is important to remember that there is an entire methodology that you should be following. Engineers and consultants often venture down proverbial rabbit holes, and neglect key areas of the environment.

By the same token, it is also important to quickly identify significant vulnerabilities within a network. As such, this methodology bears two hallmarks:

Comprehensiveness, so that you can consistently identify significant flaws

Flexibility, so that you can prioritize your efforts and maximize return

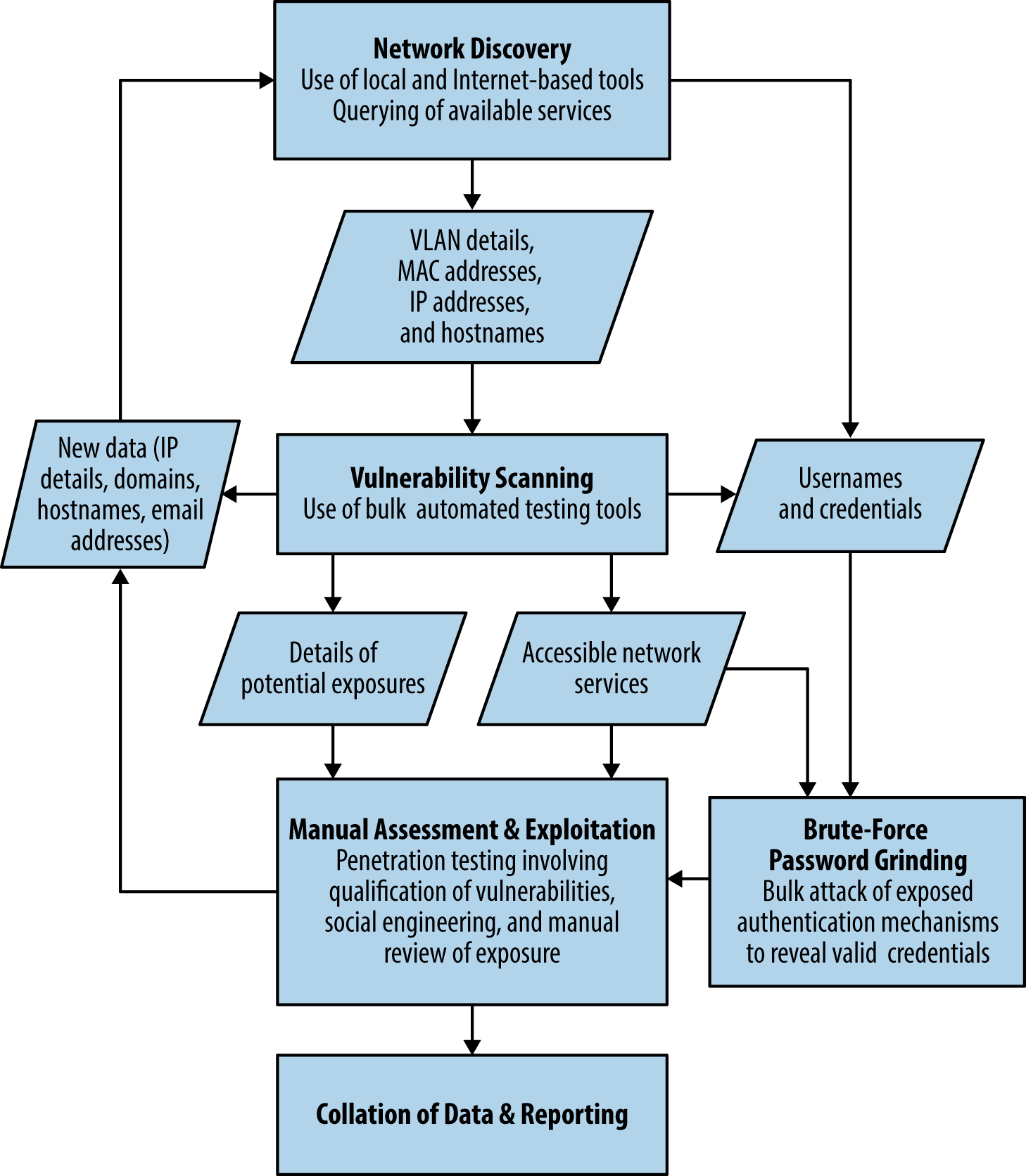

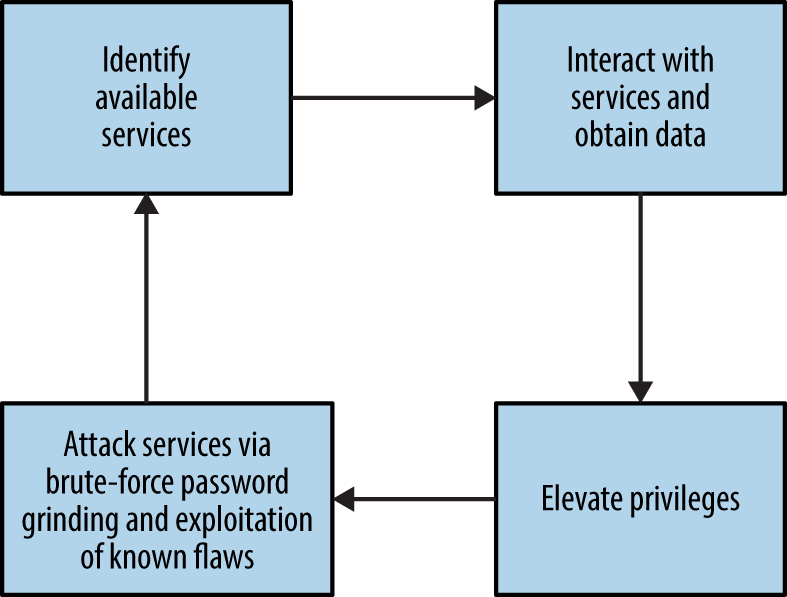

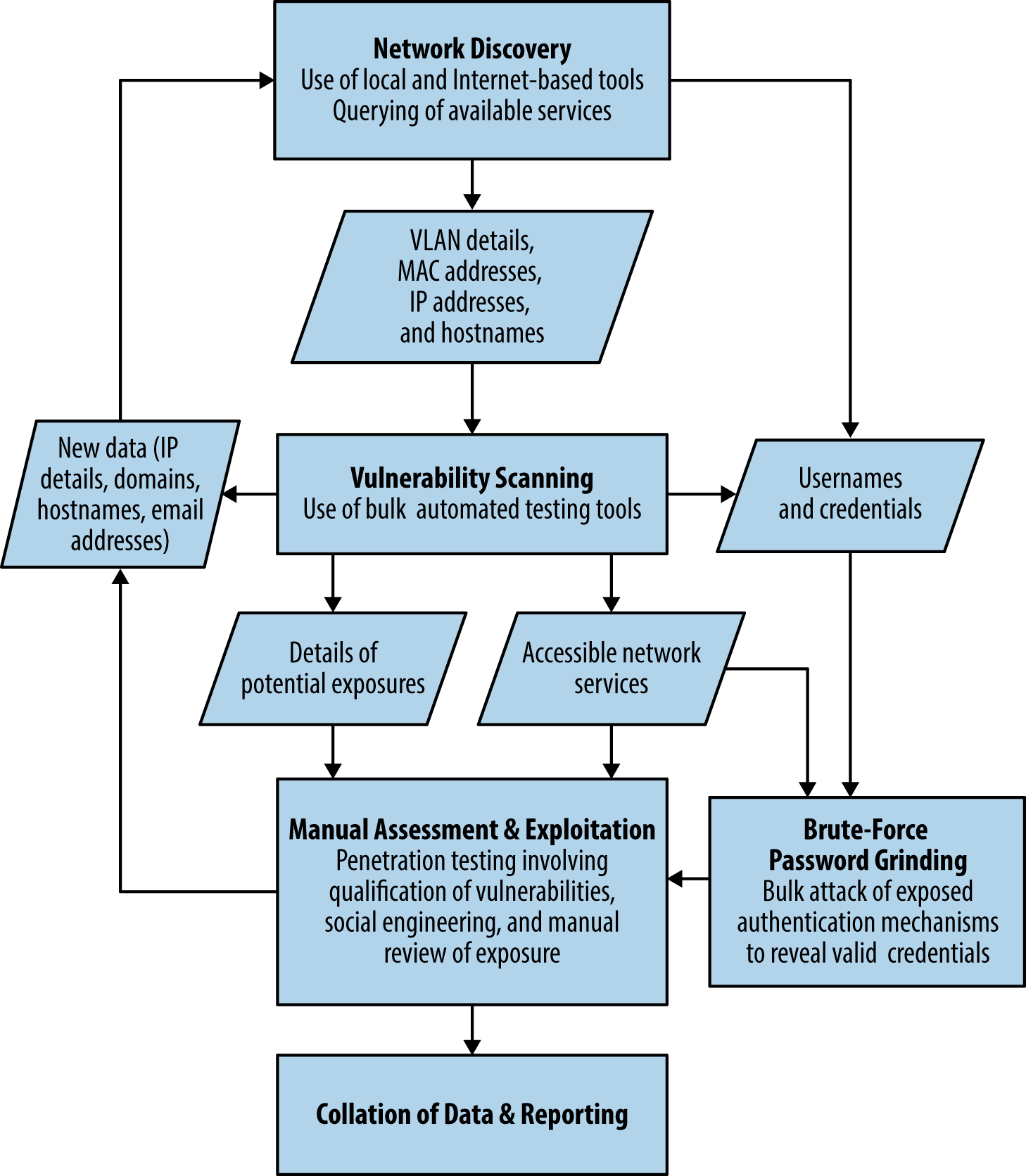

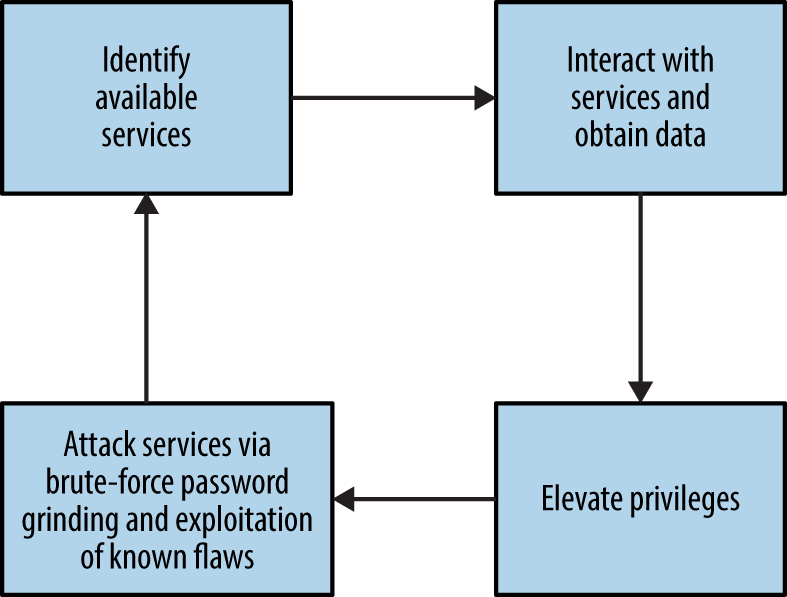

The best practice assessment methodology used by determined attackers and security consultants involves four distinct steps:

Reconnaissance to identify networks, hosts, and users of interest

Vulnerability scanning to identify potentially exploitable conditions

Investigation of vulnerabilities and further probing by hand

Exploitation of vulnerabilities and circumvention of security mechanisms

This methodology is relevant to the testing of Internet networks in a blind fashion with limited target information (such as a domain name). If a consultant is enlisted to assess a specific block of IP space, she can skip network enumeration and commence bulk network scanning and investigation of vulnerabilities.

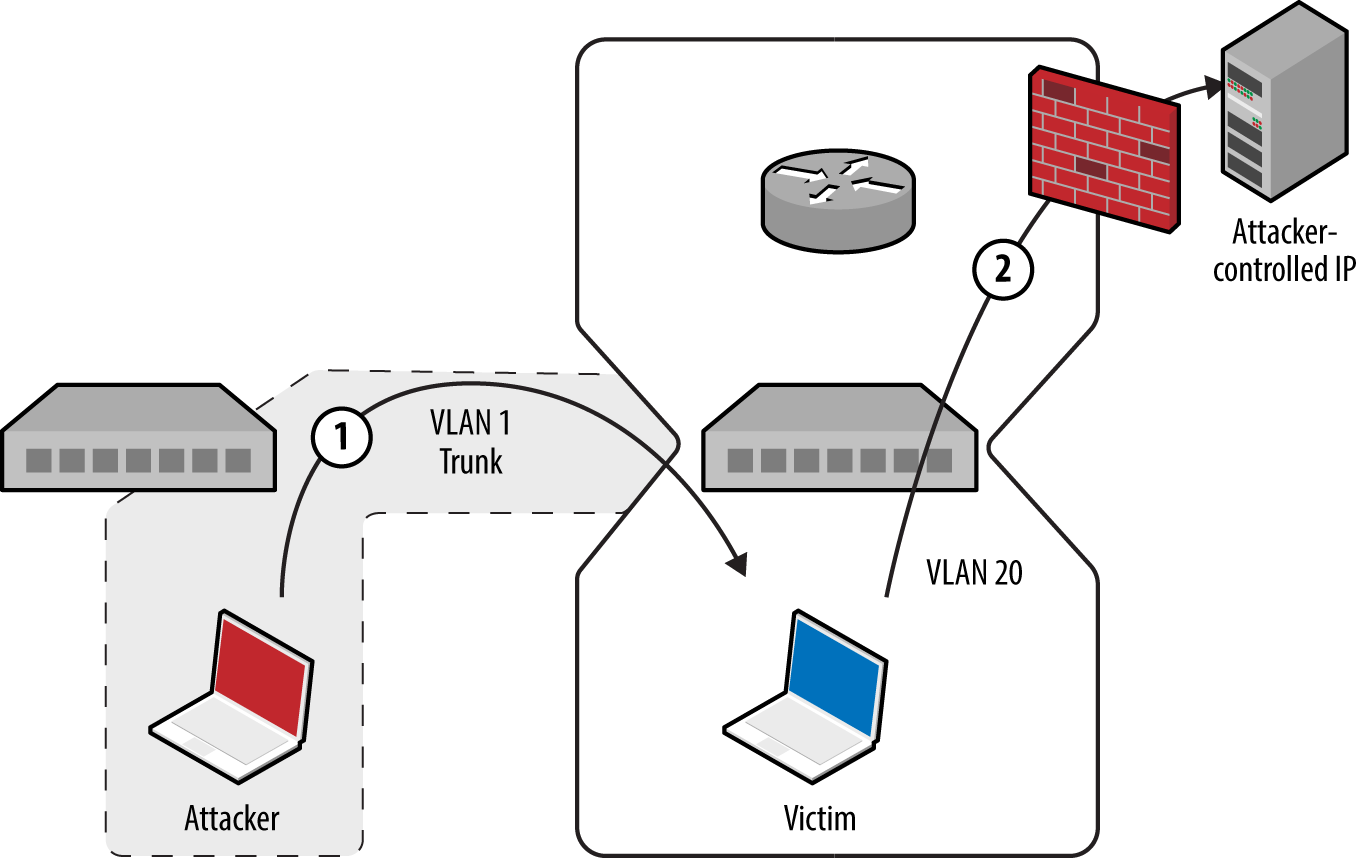

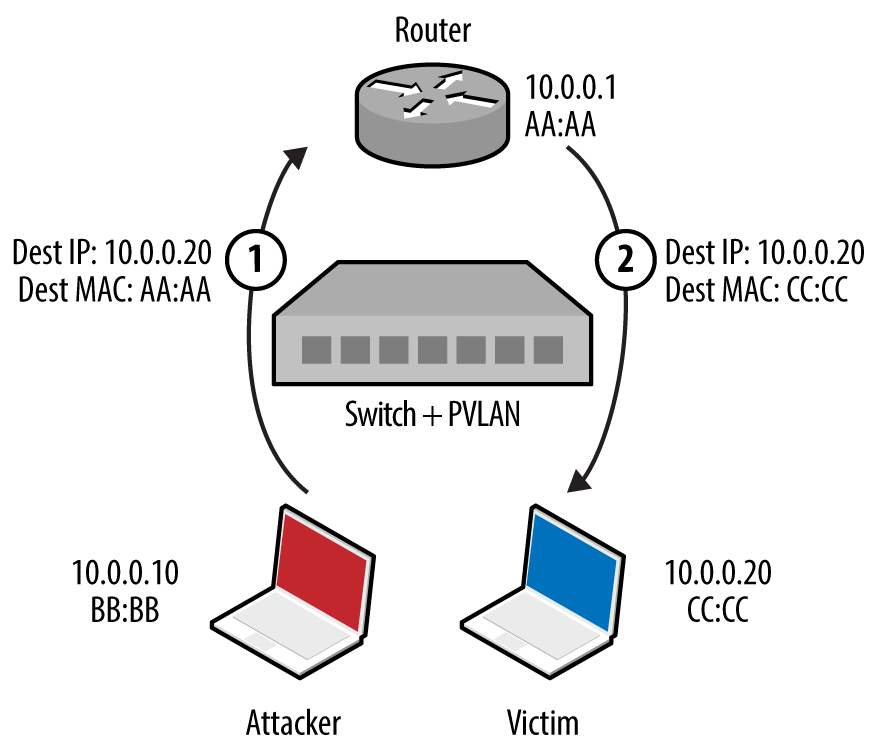

Local network testing involves assessment of nonroutable protocols and OSI Layer 2 features (e.g., 802.1X and 802.1Q). You can use VLAN hopping and network sniffing to compromise data and systems, as detailed in Chapter 5.

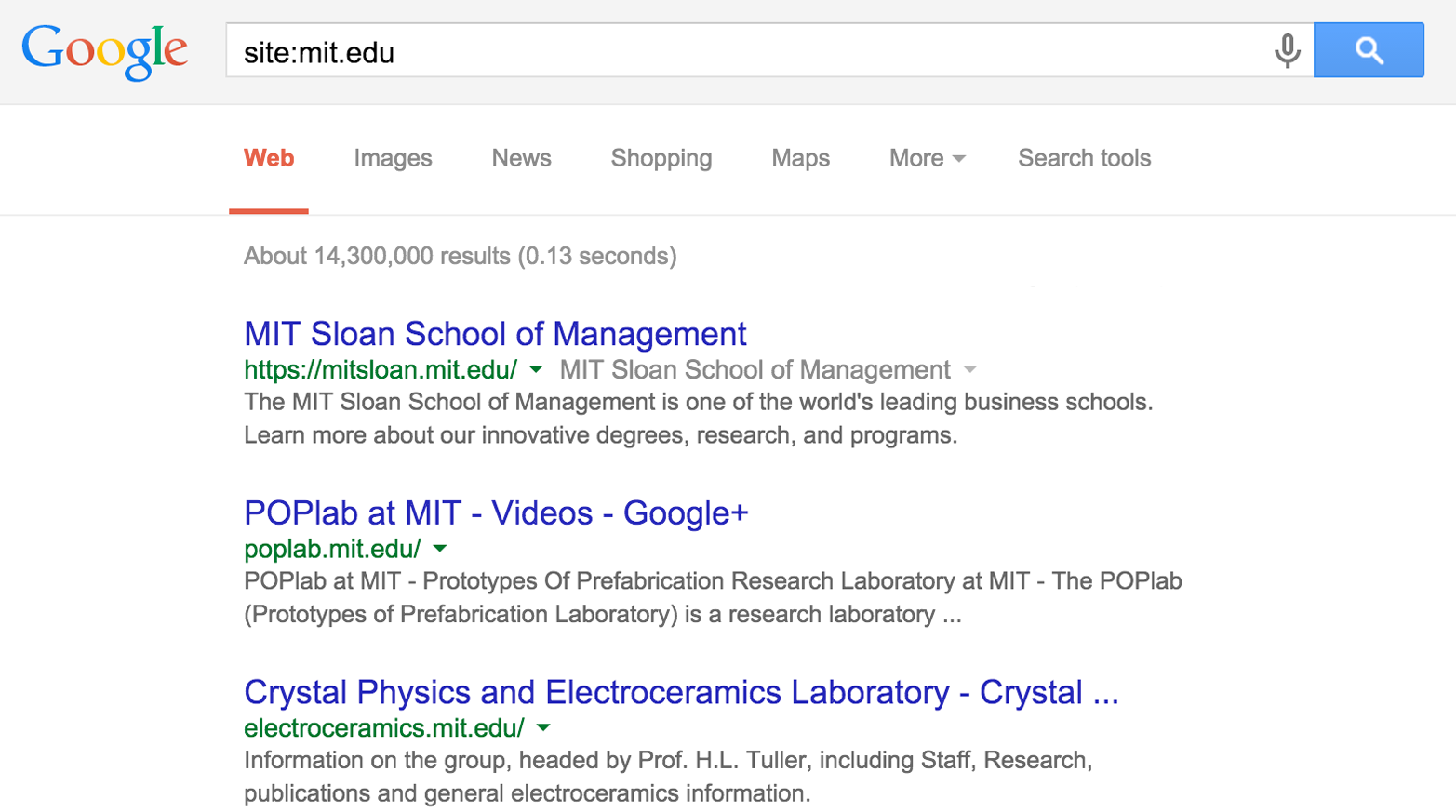

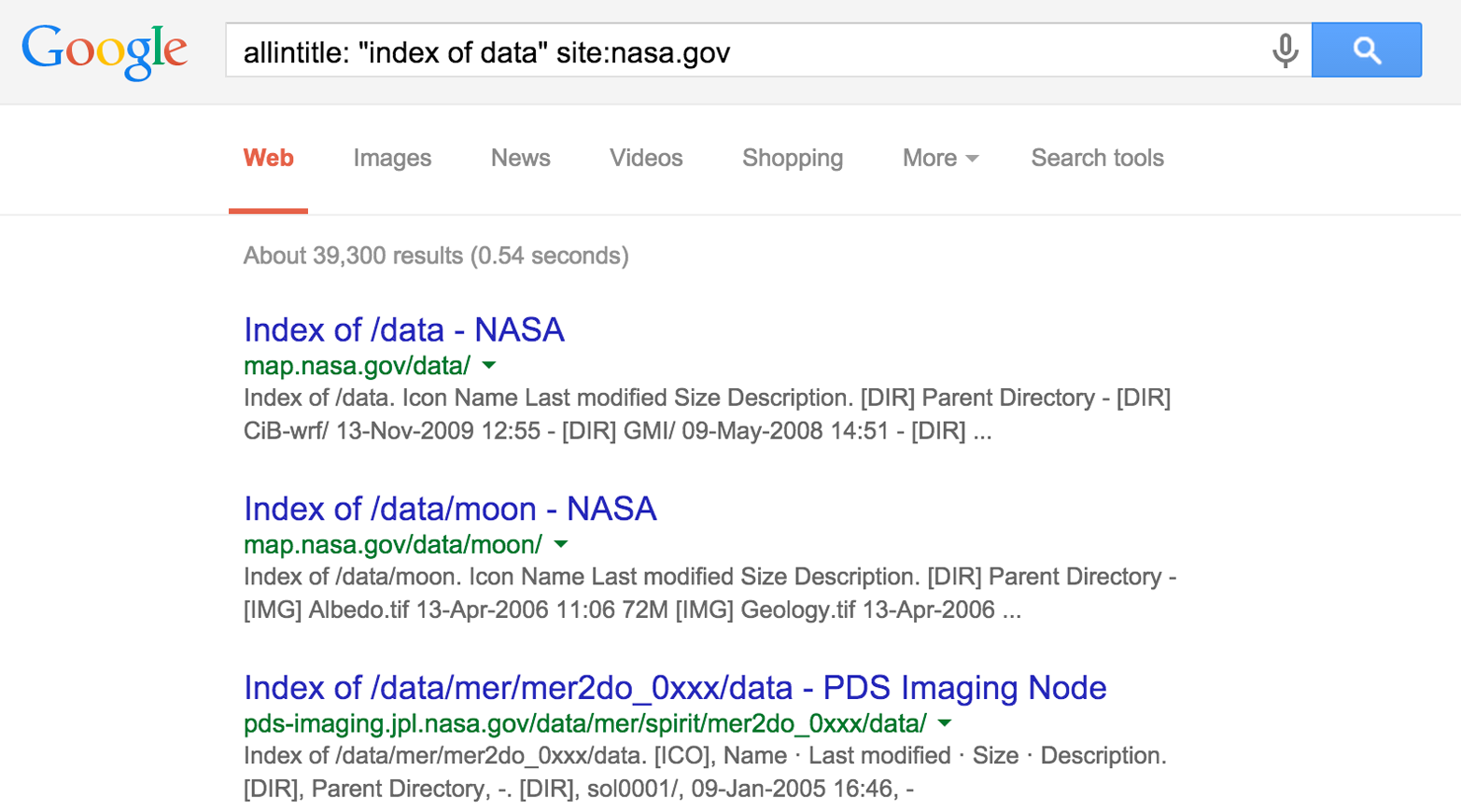

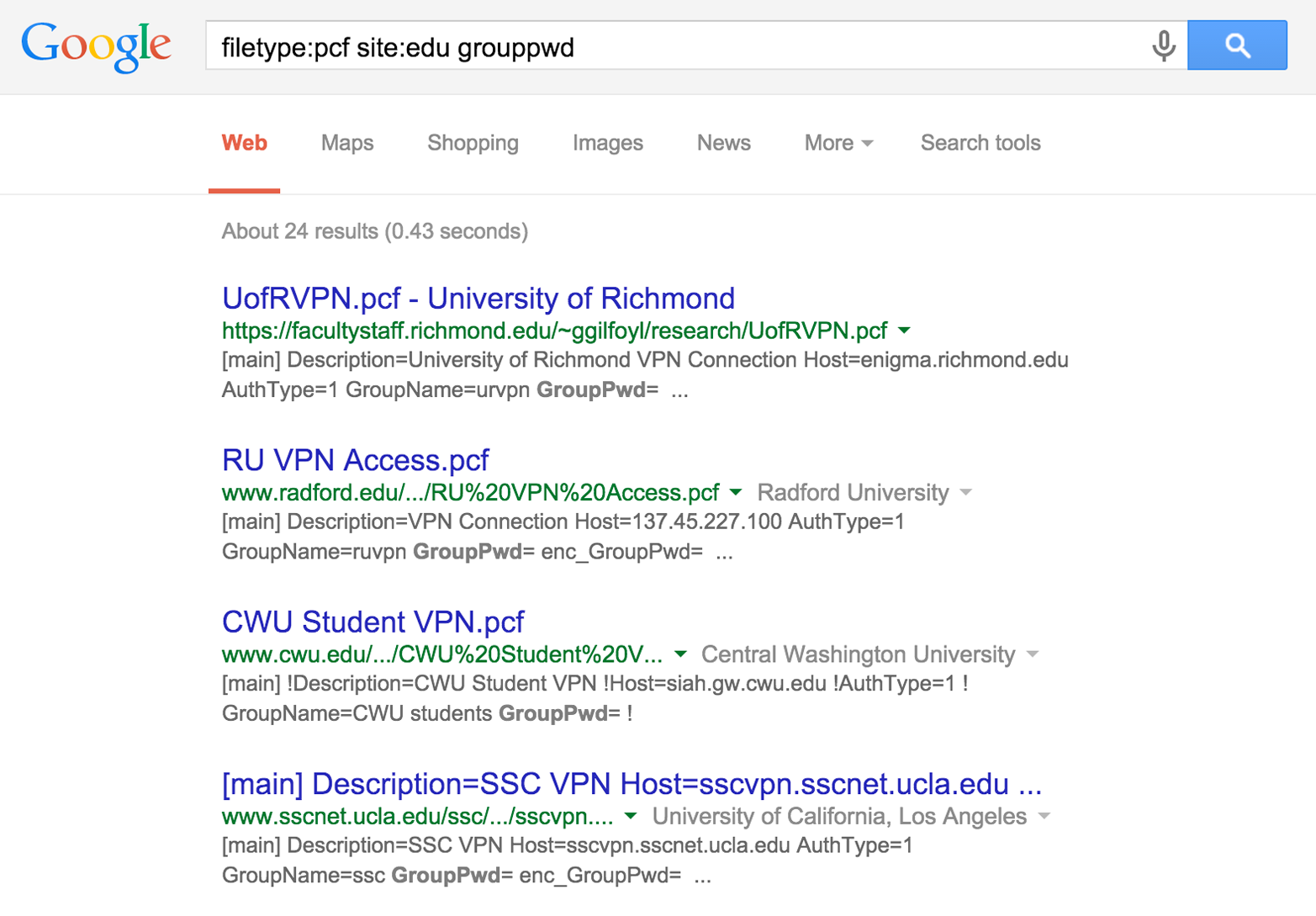

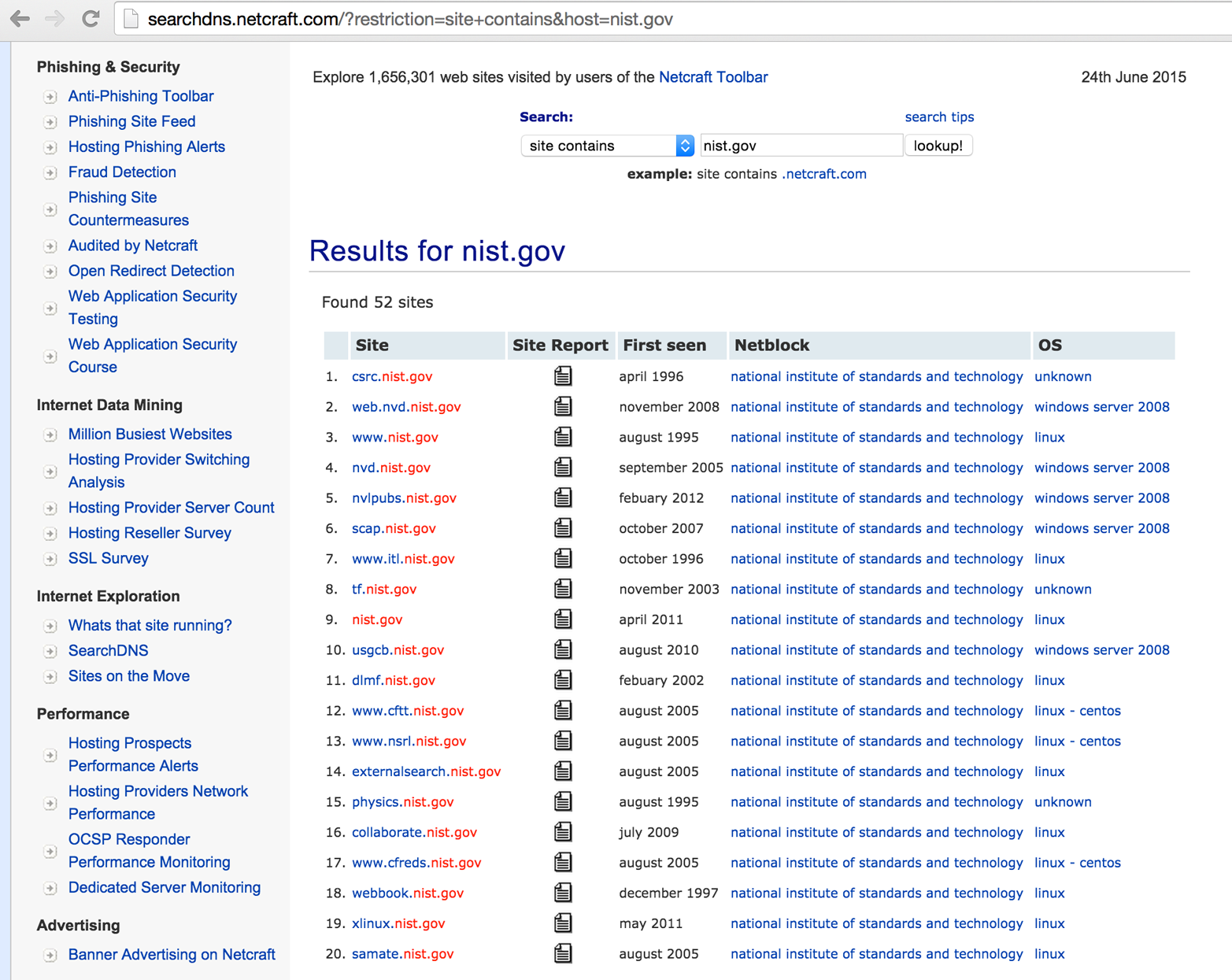

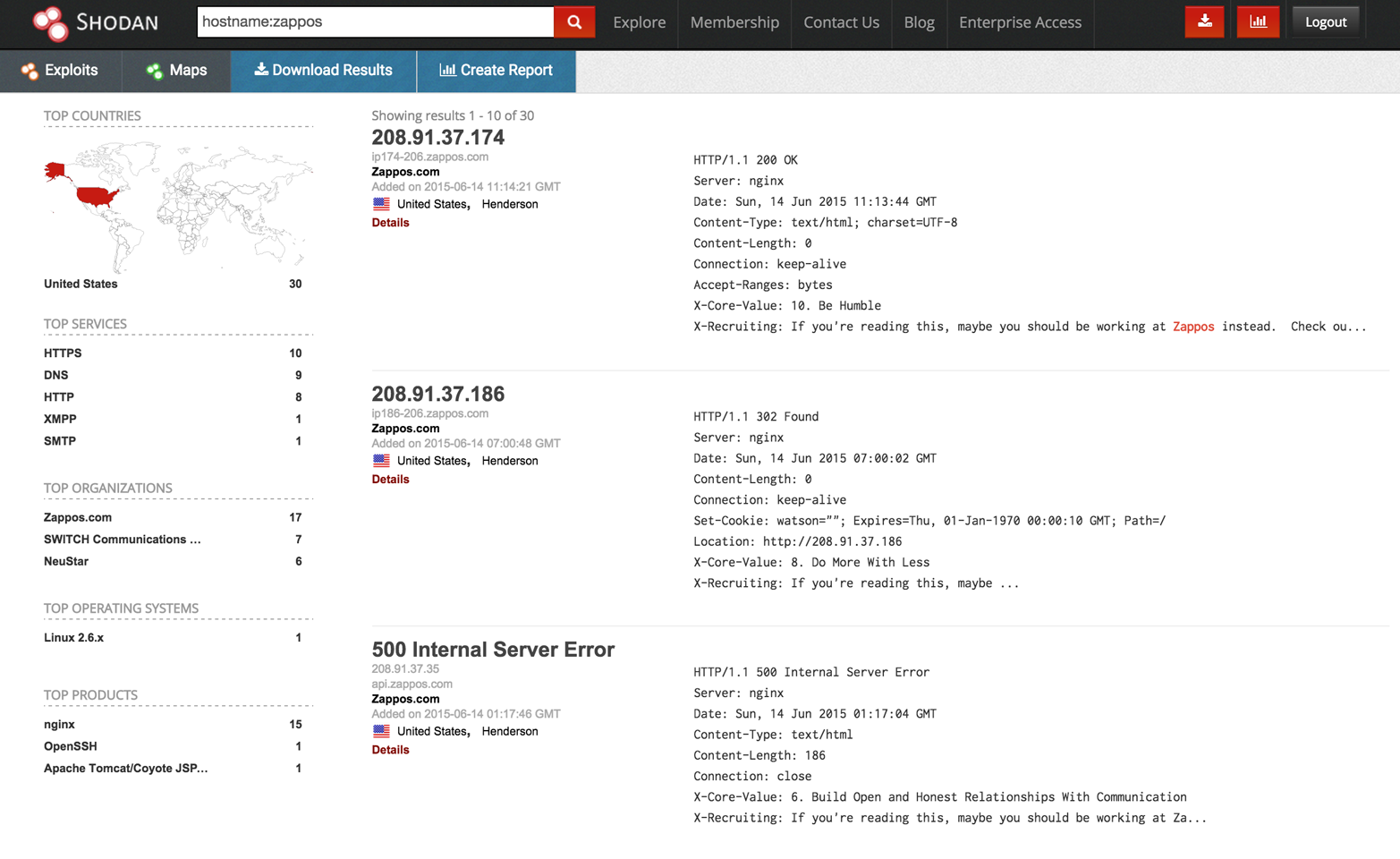

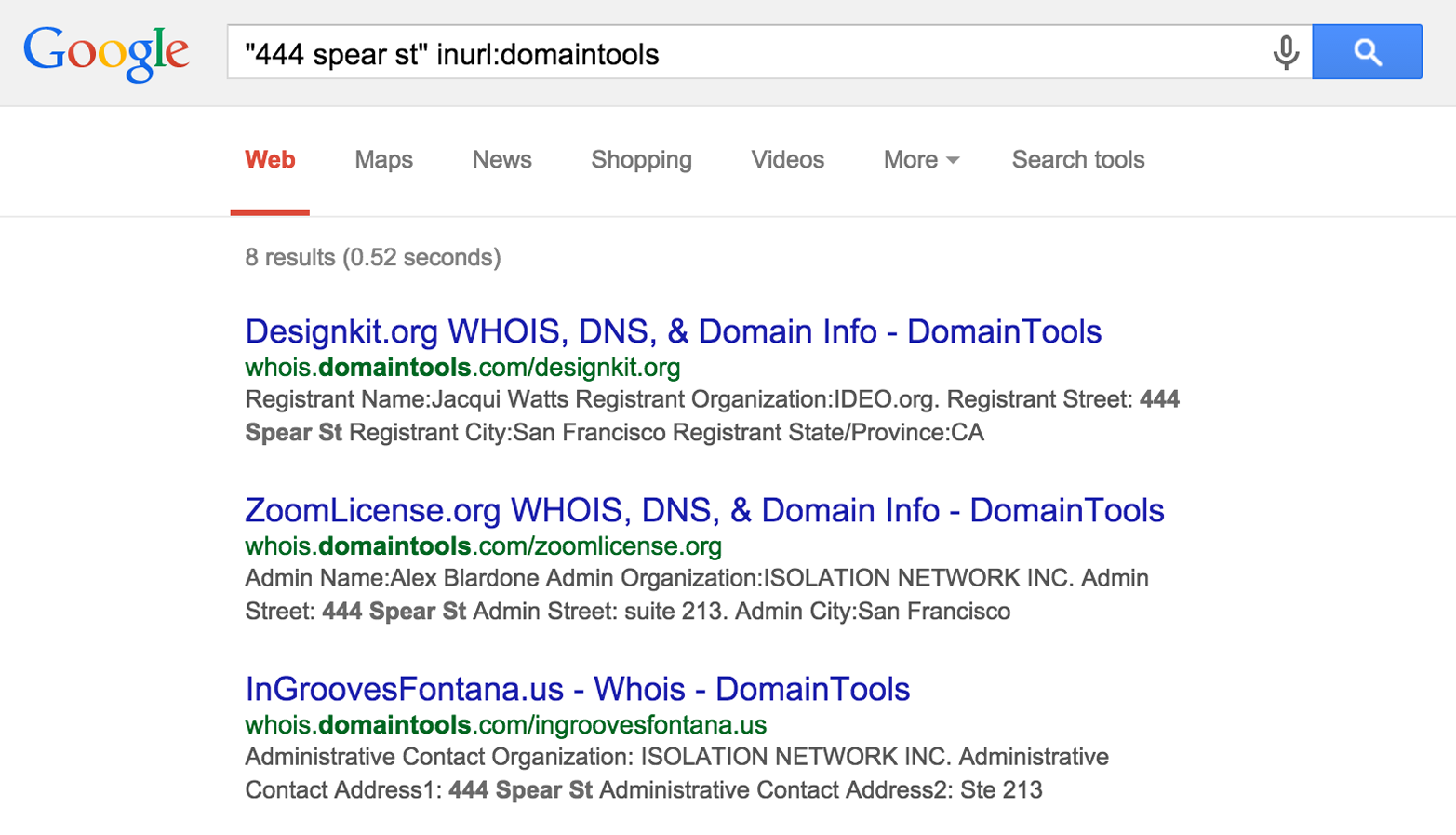

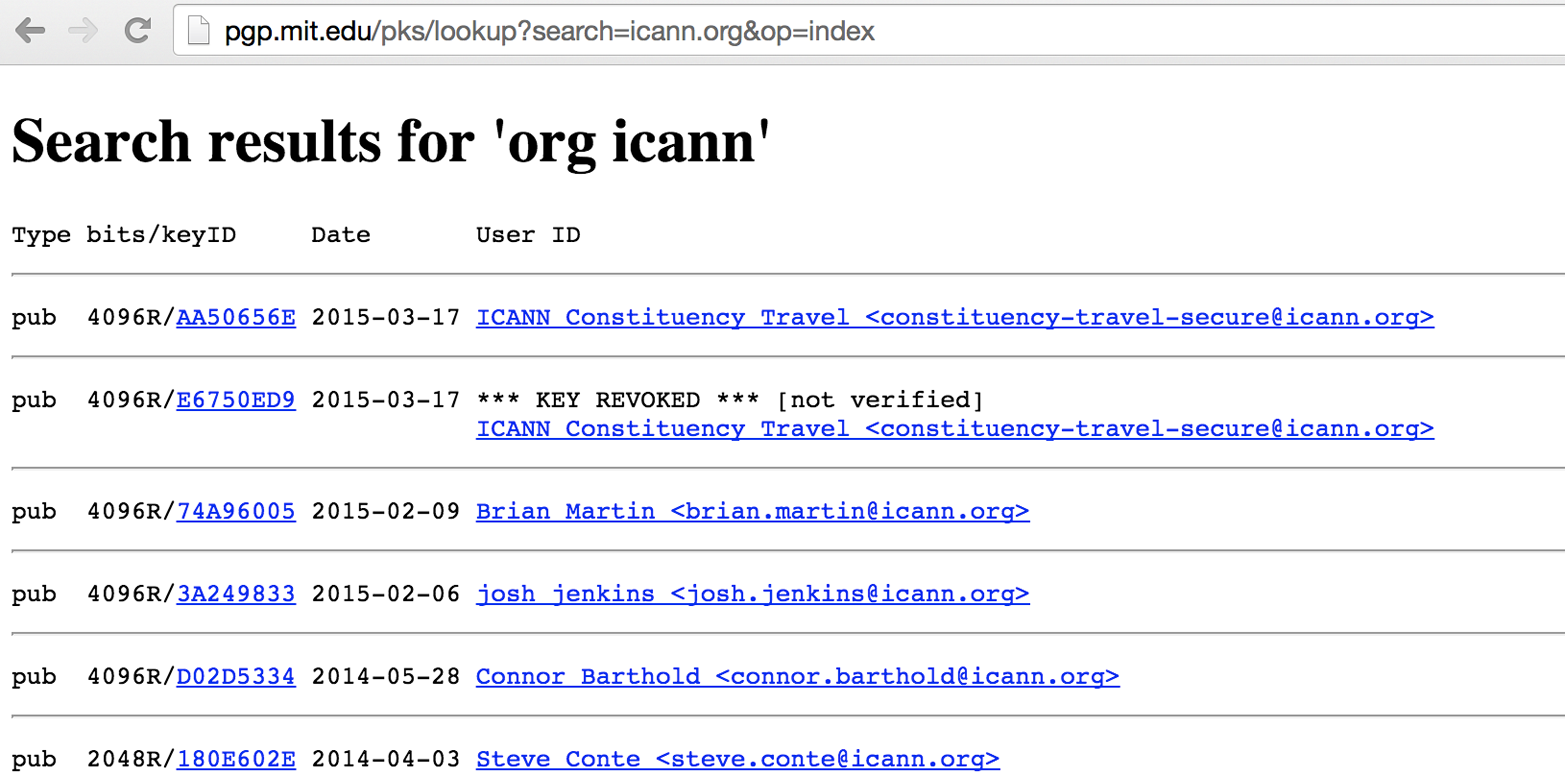

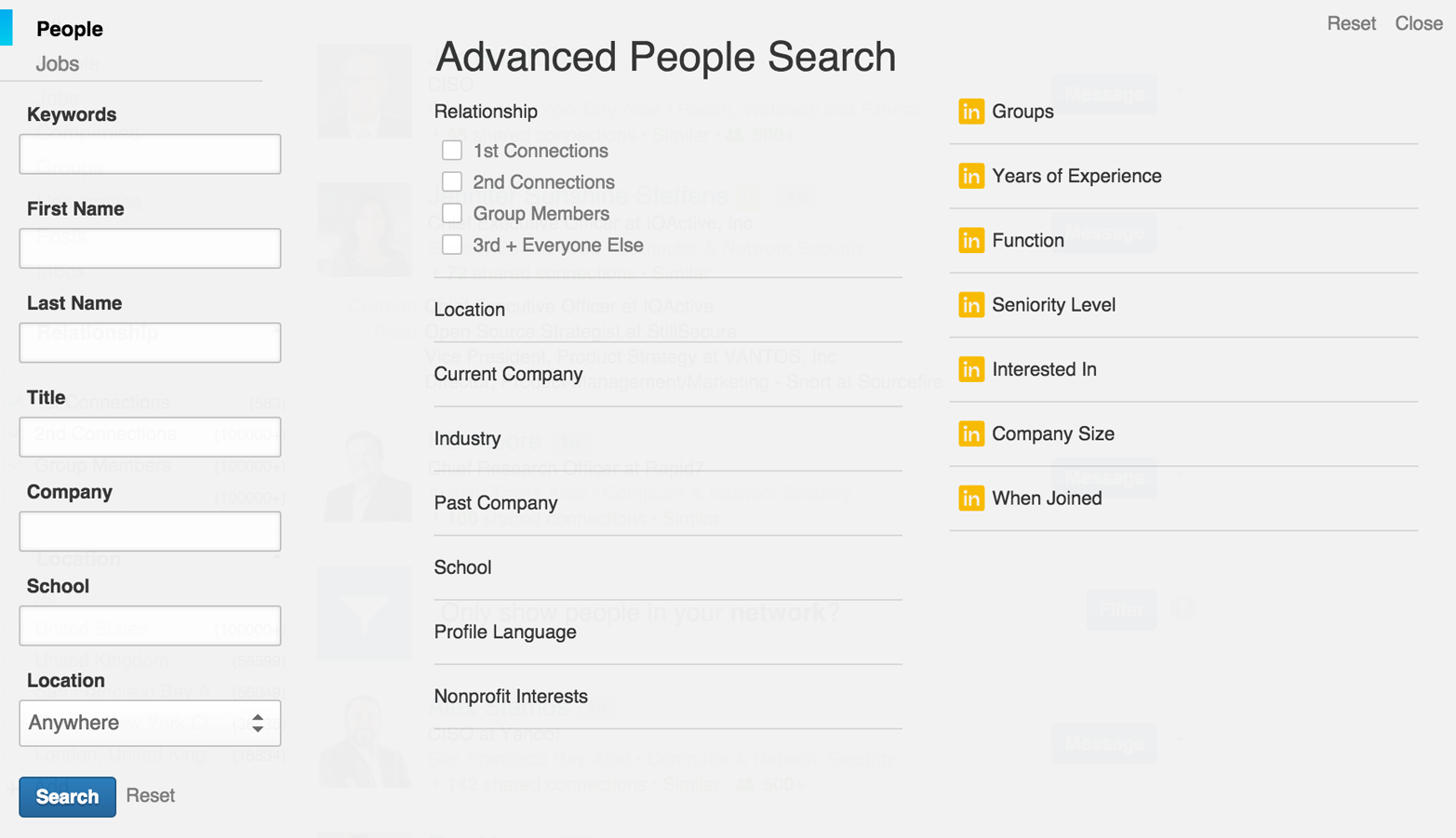

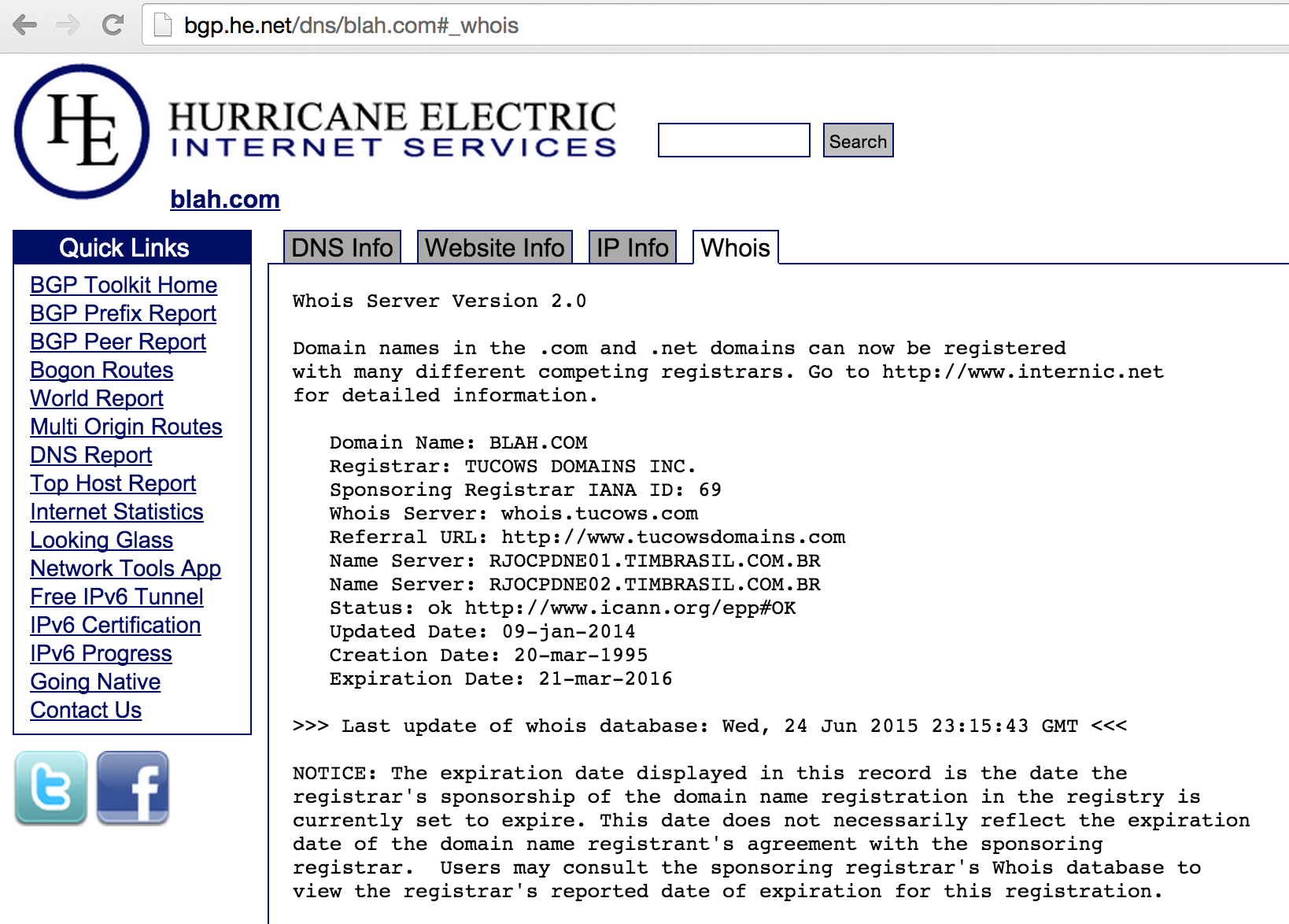

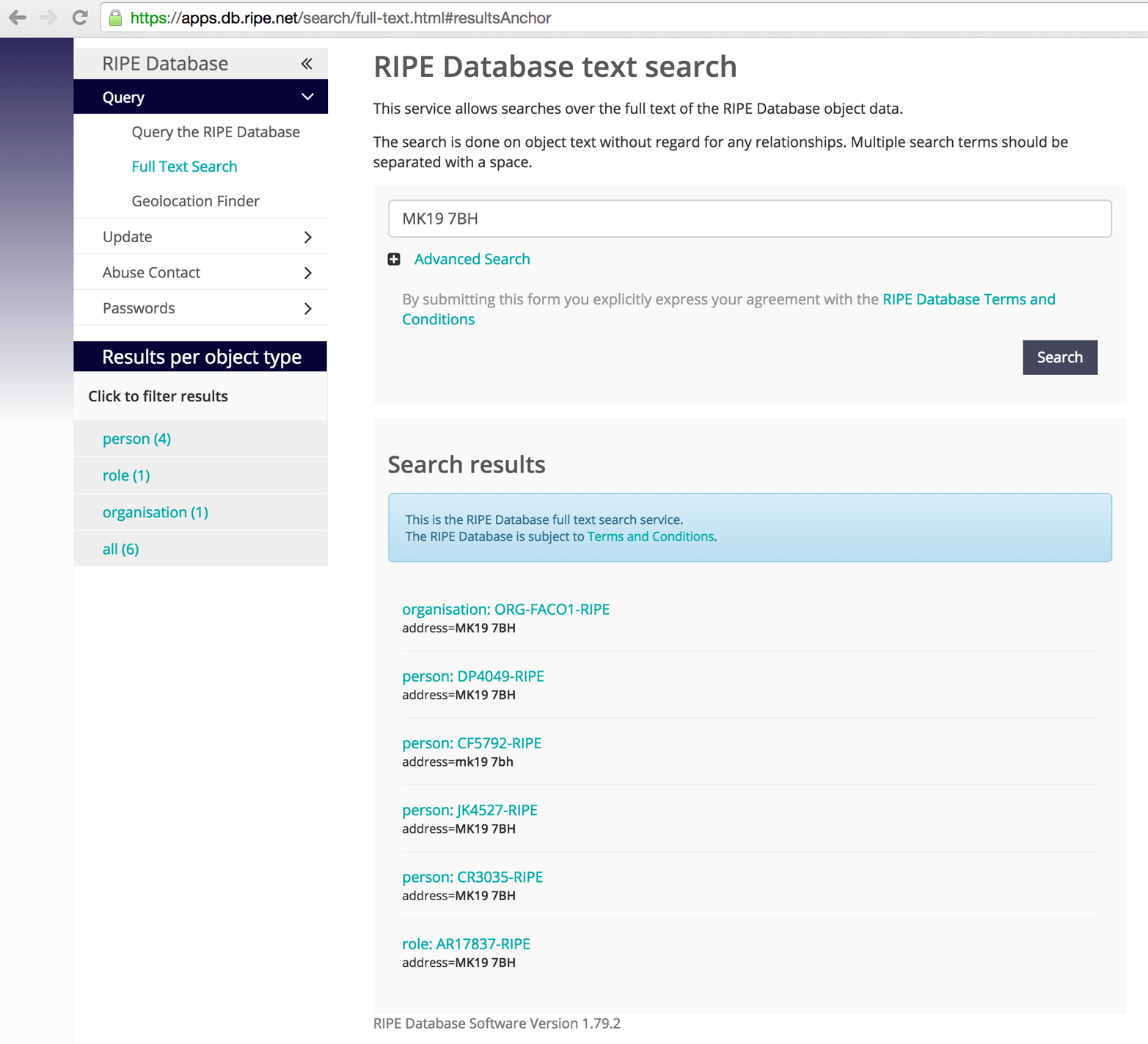

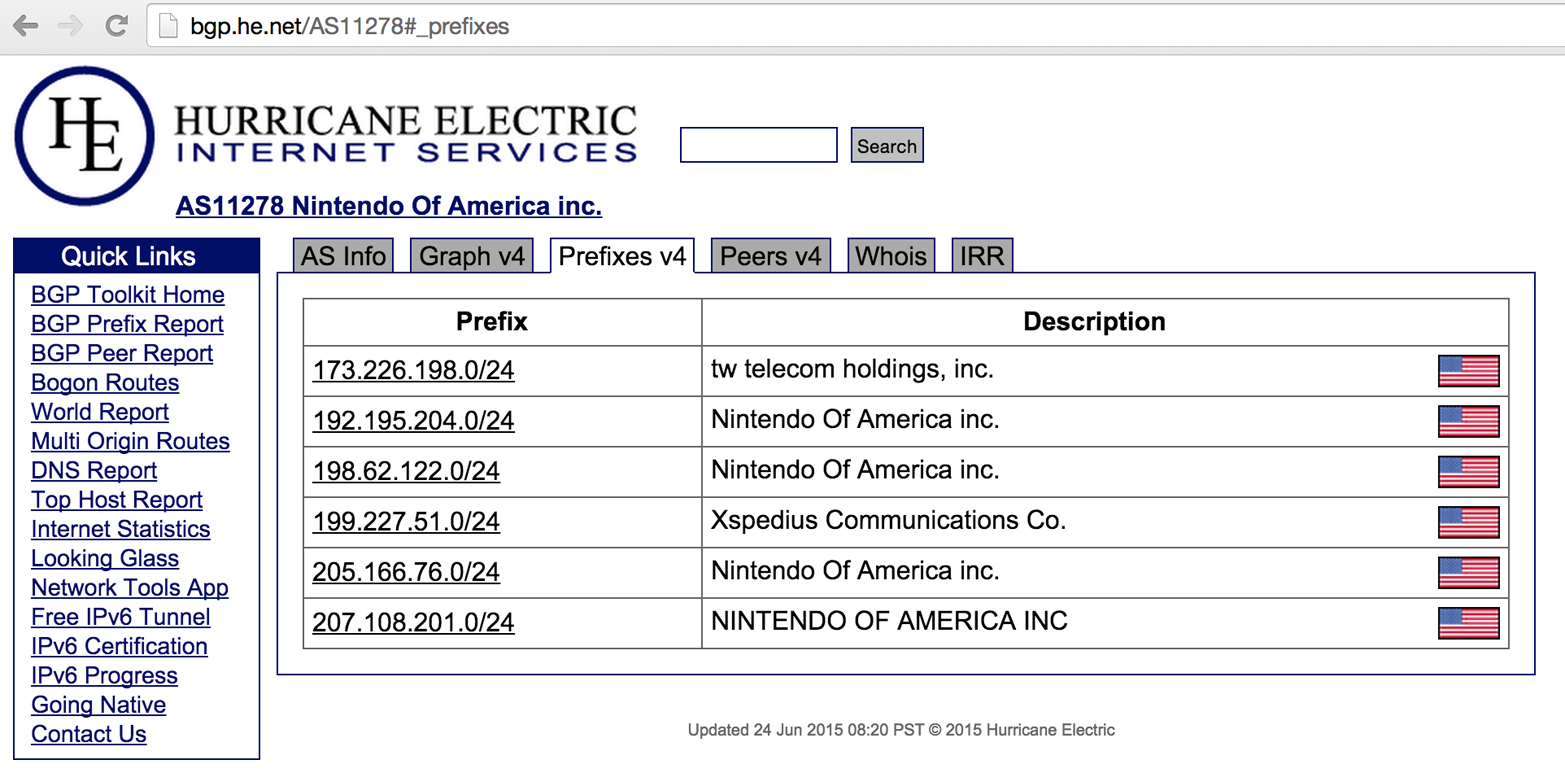

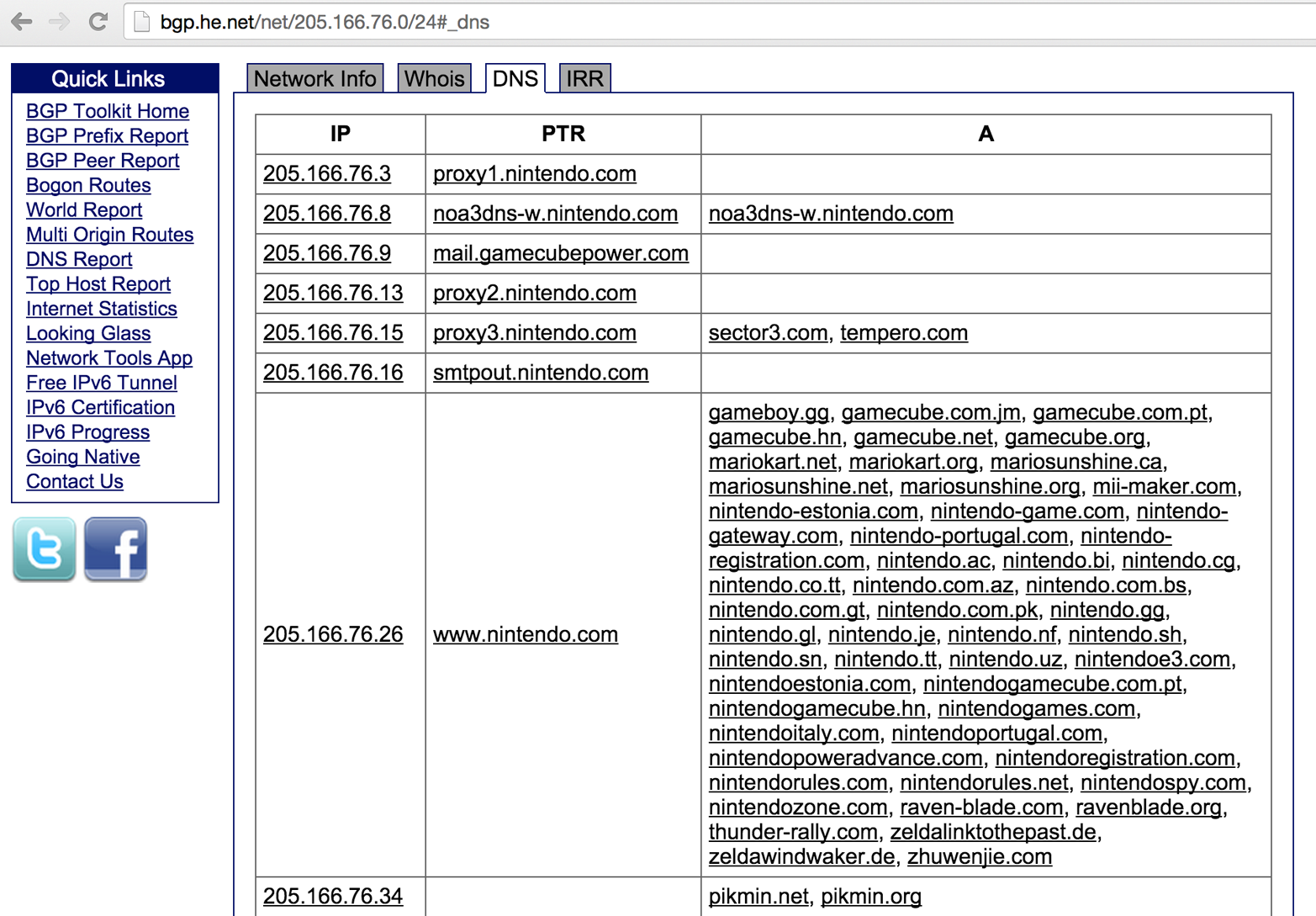

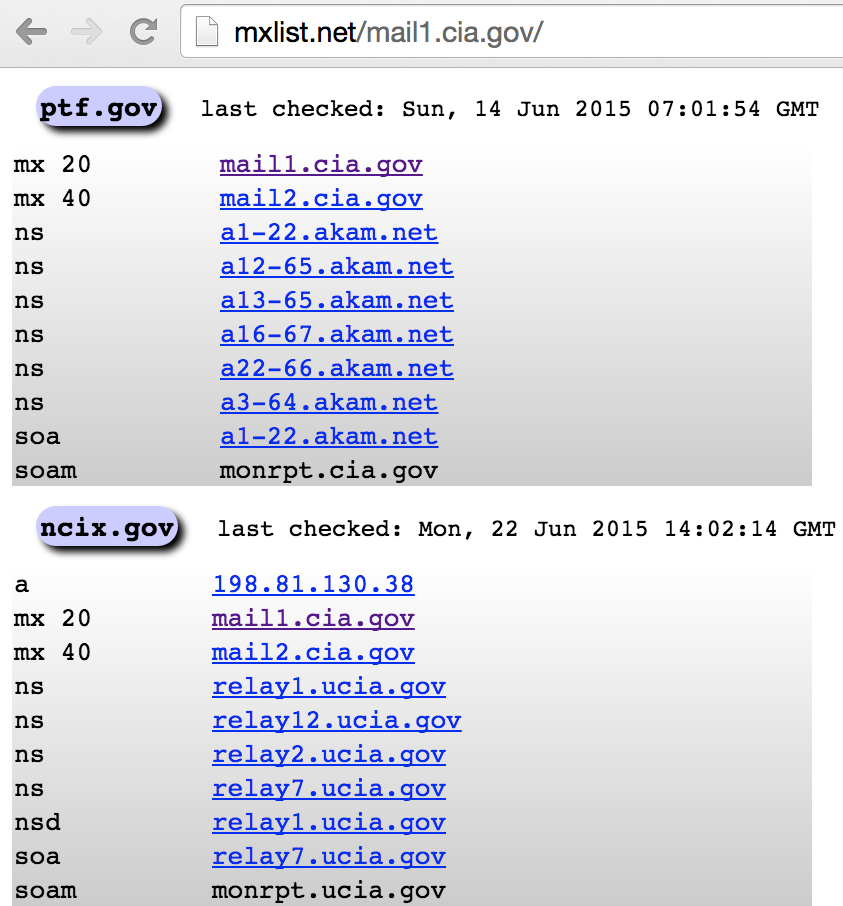

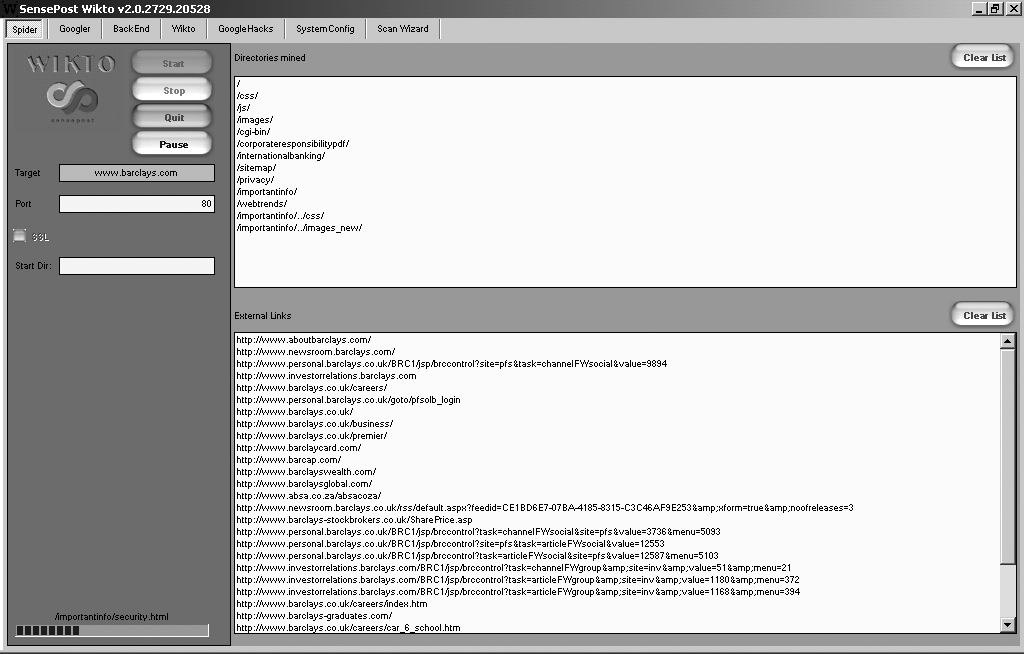

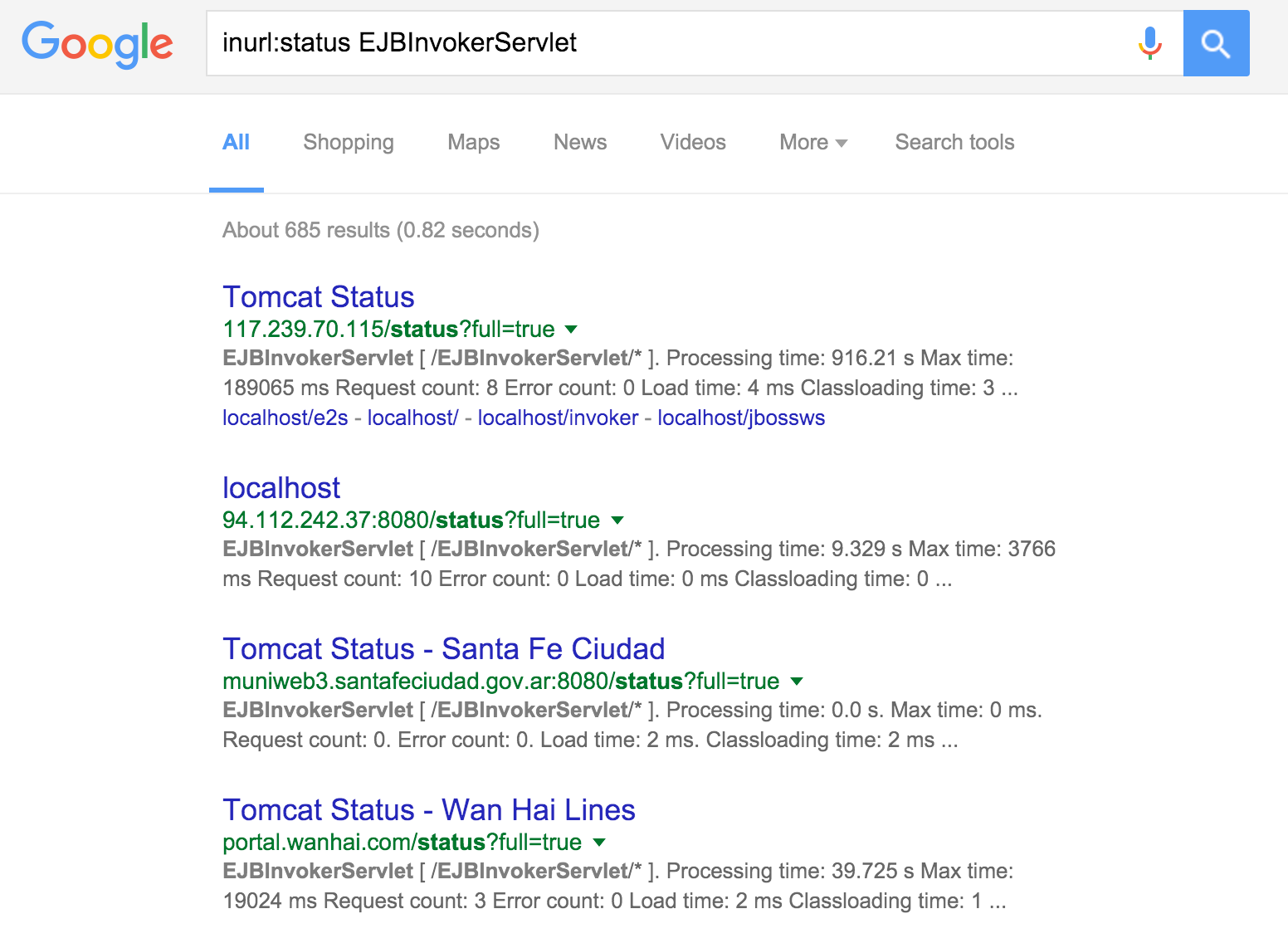

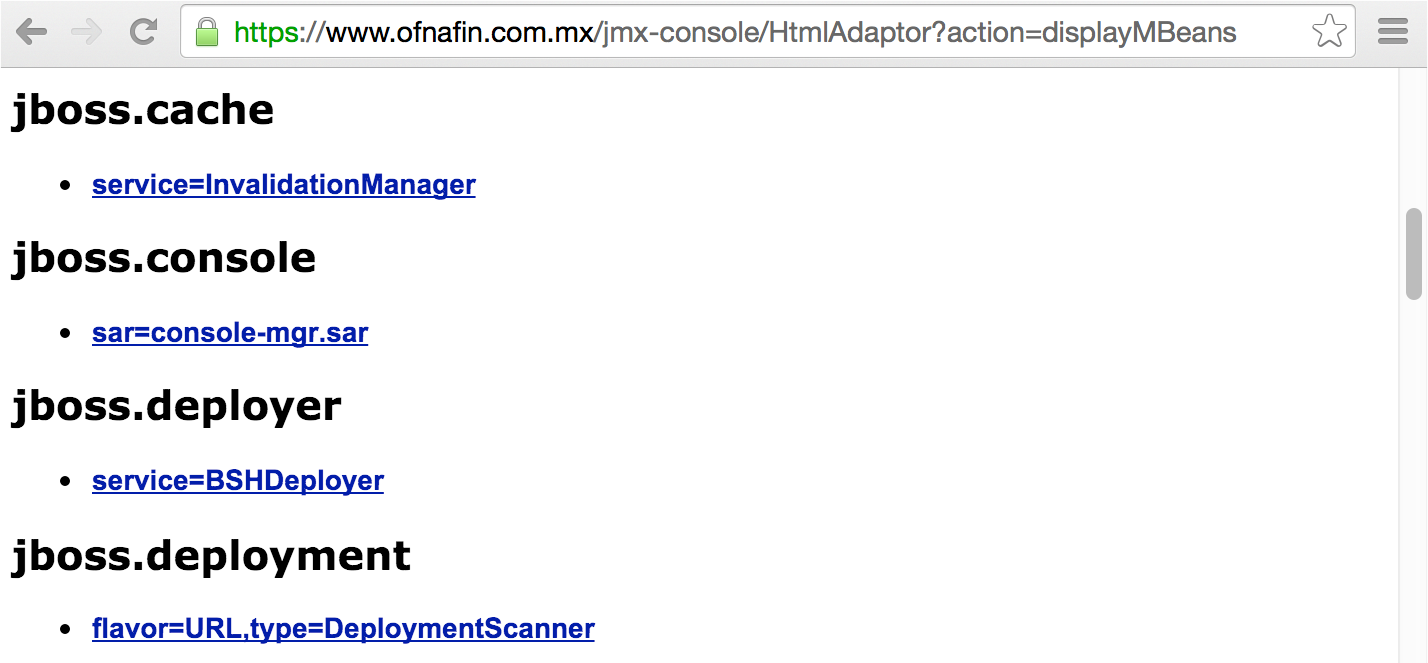

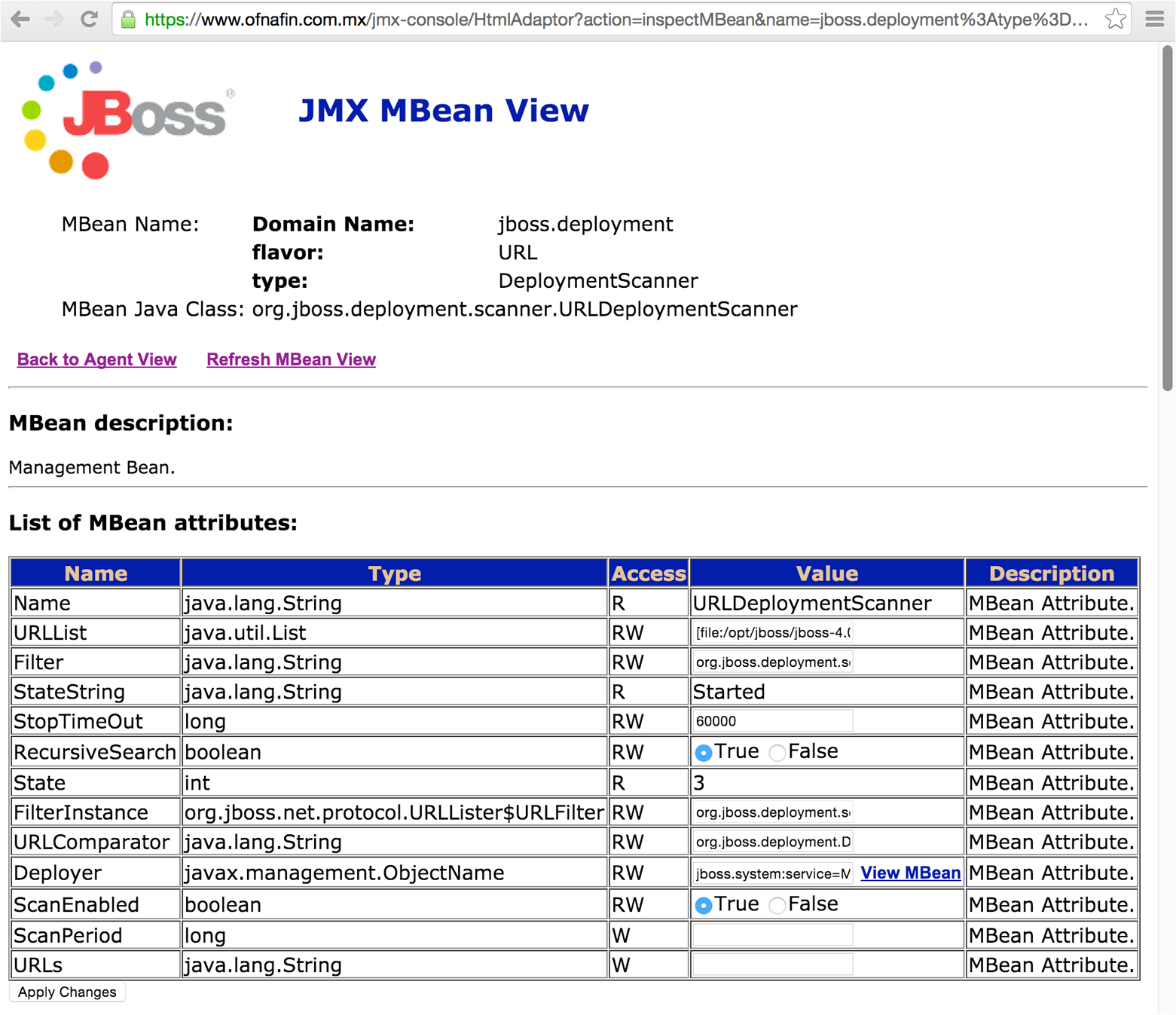

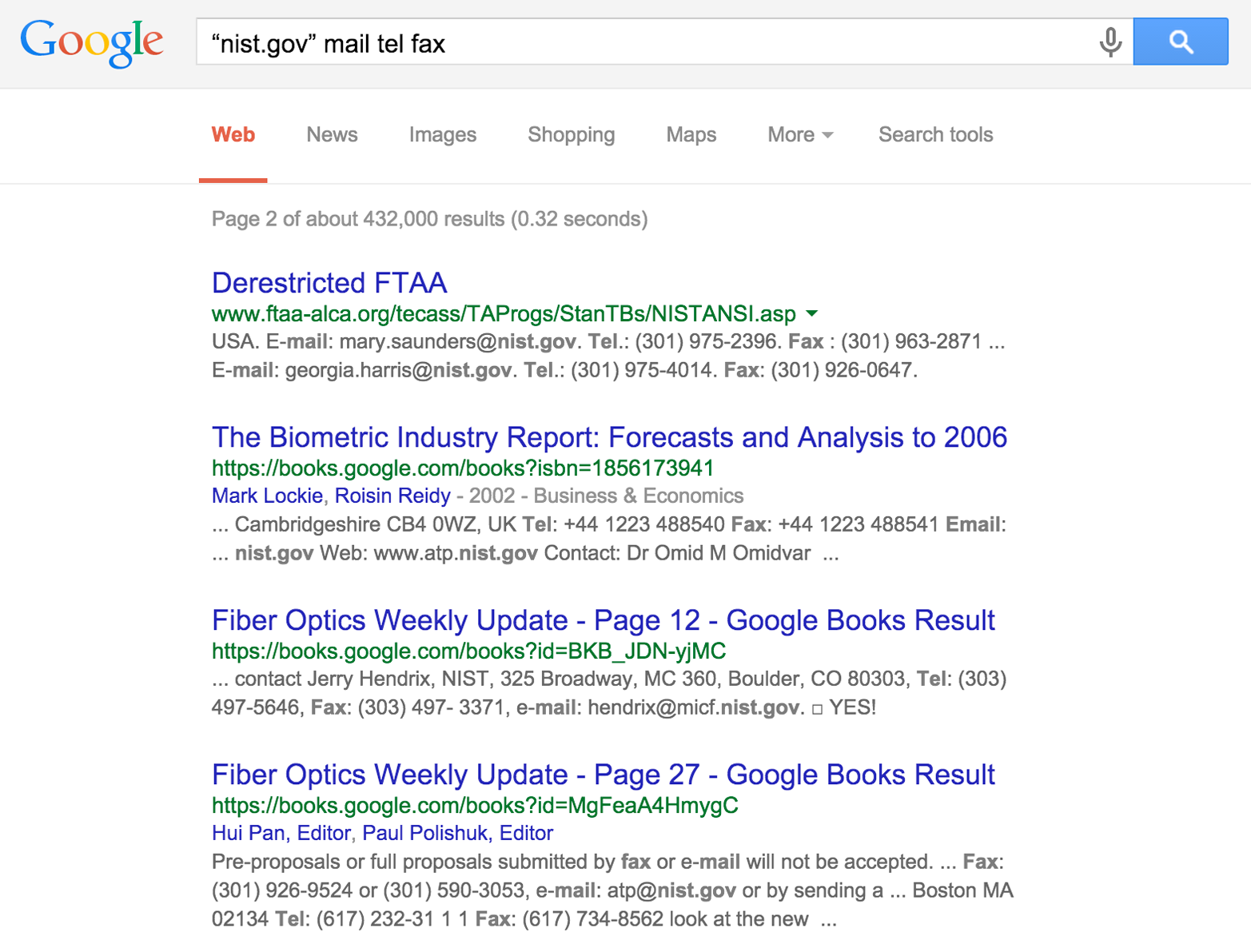

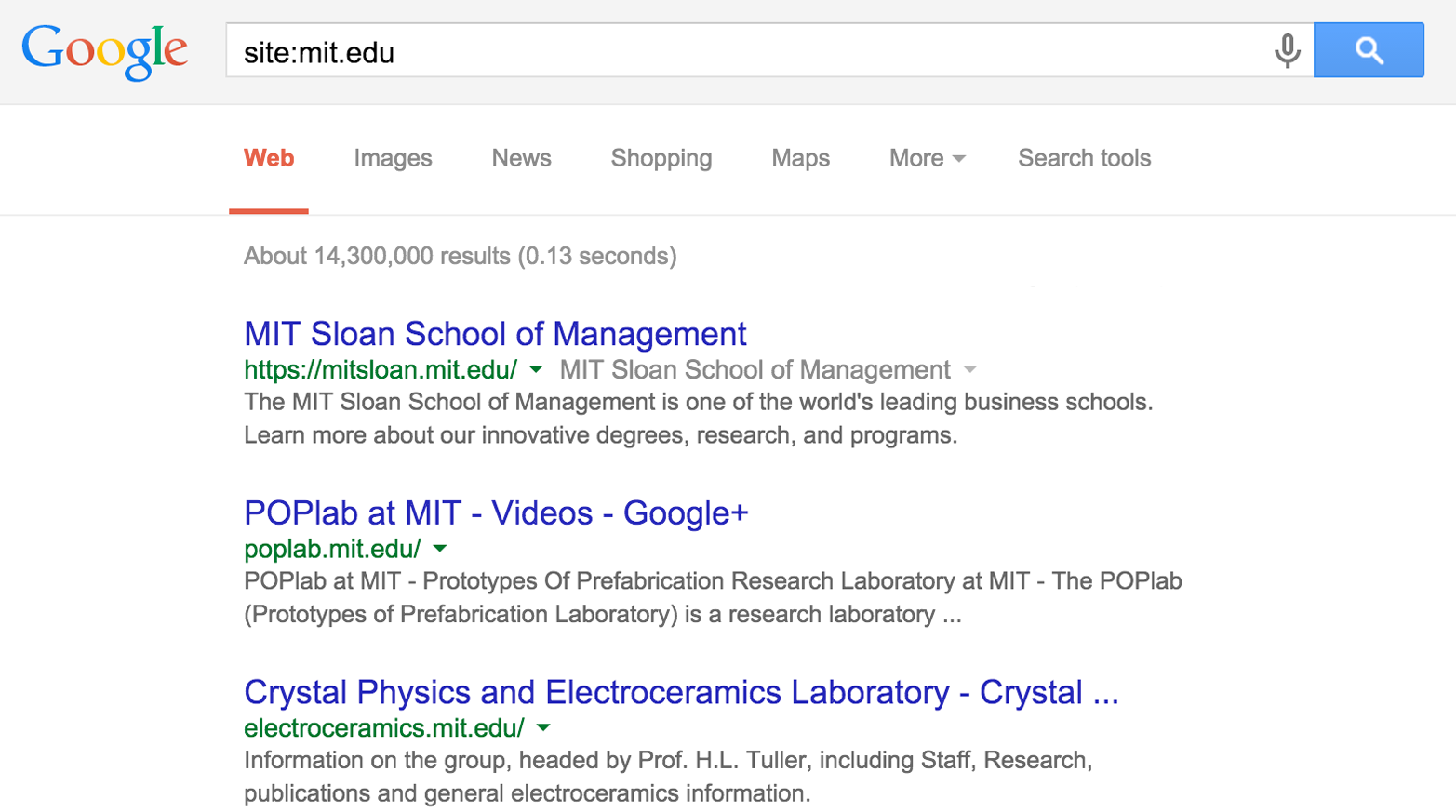

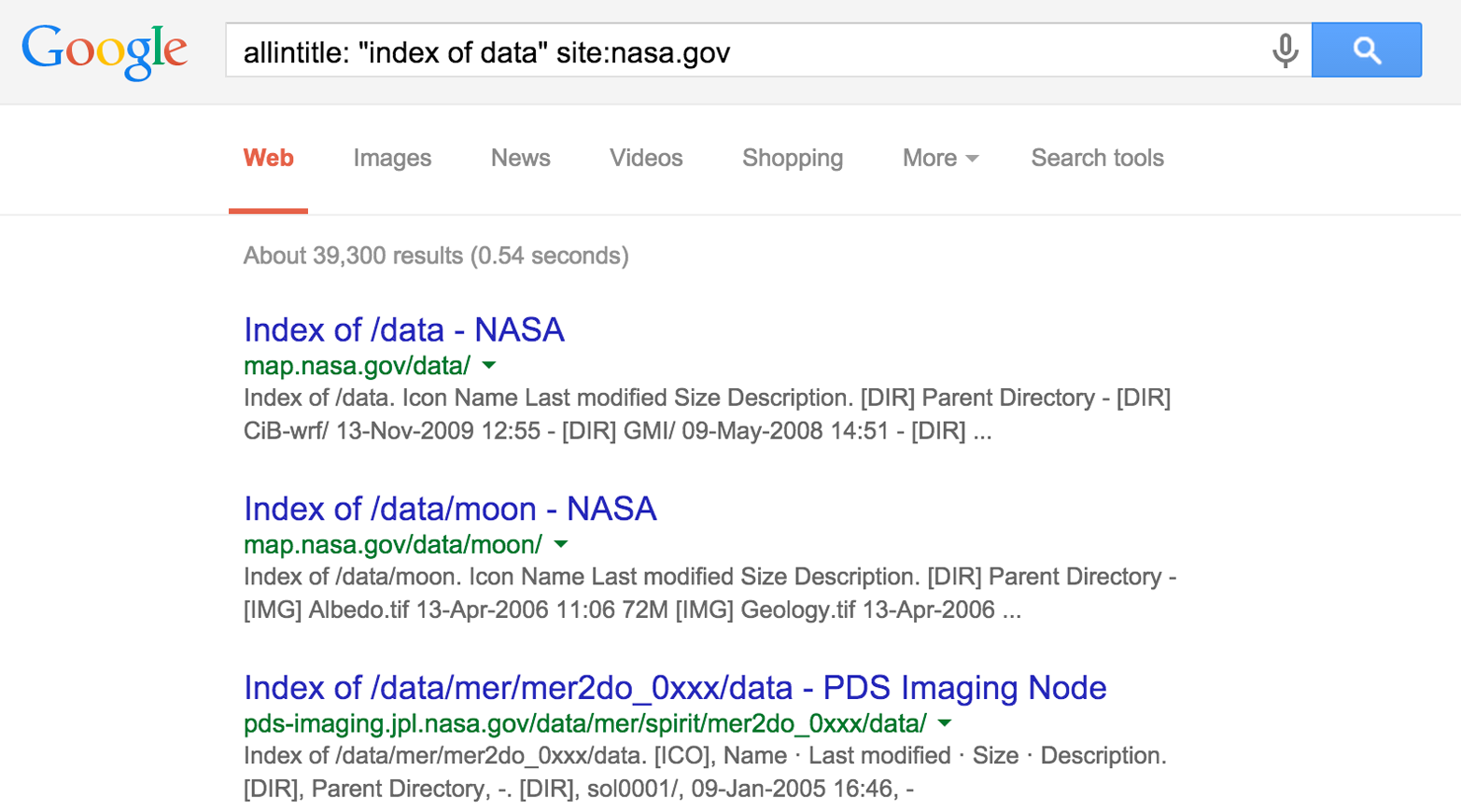

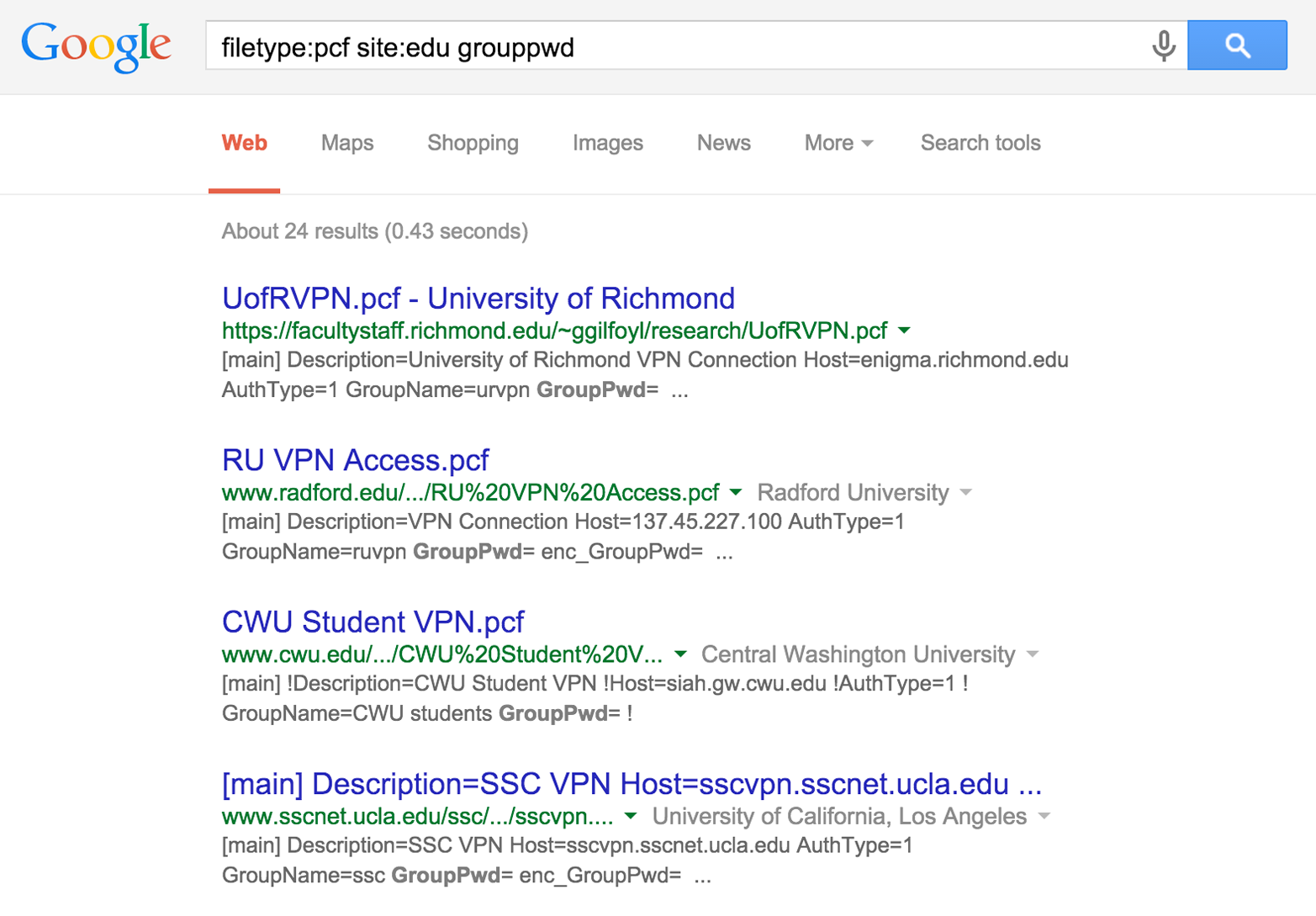

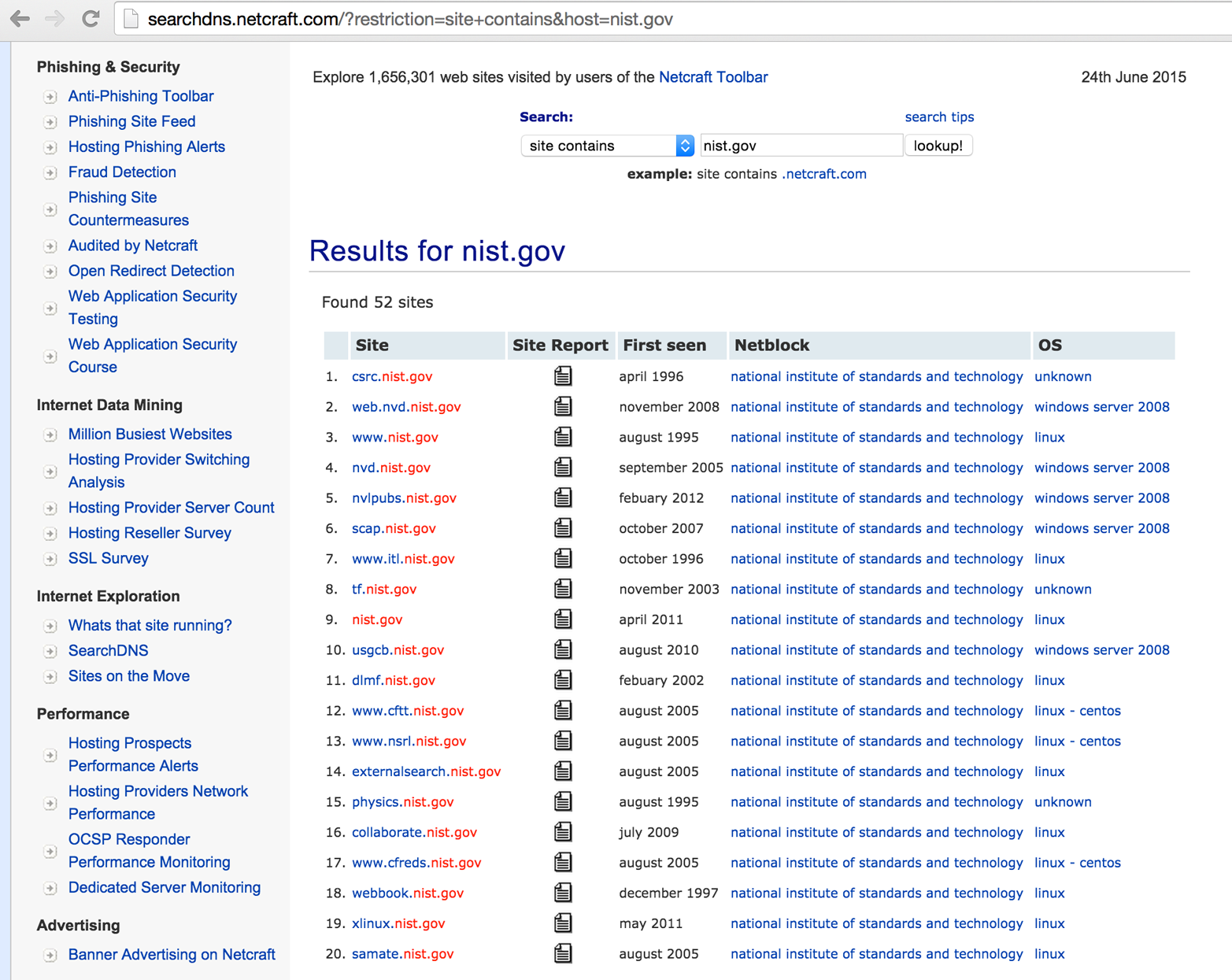

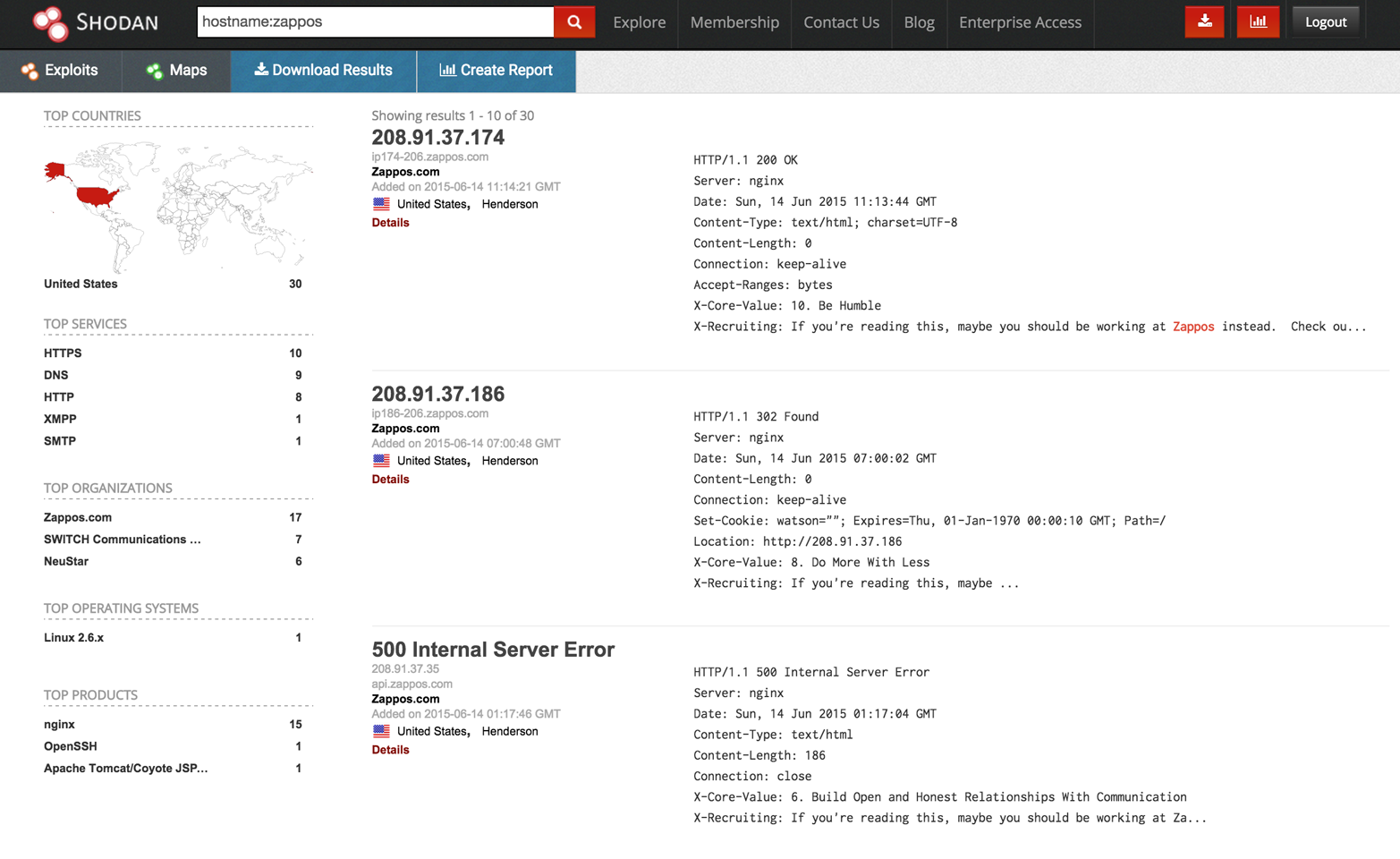

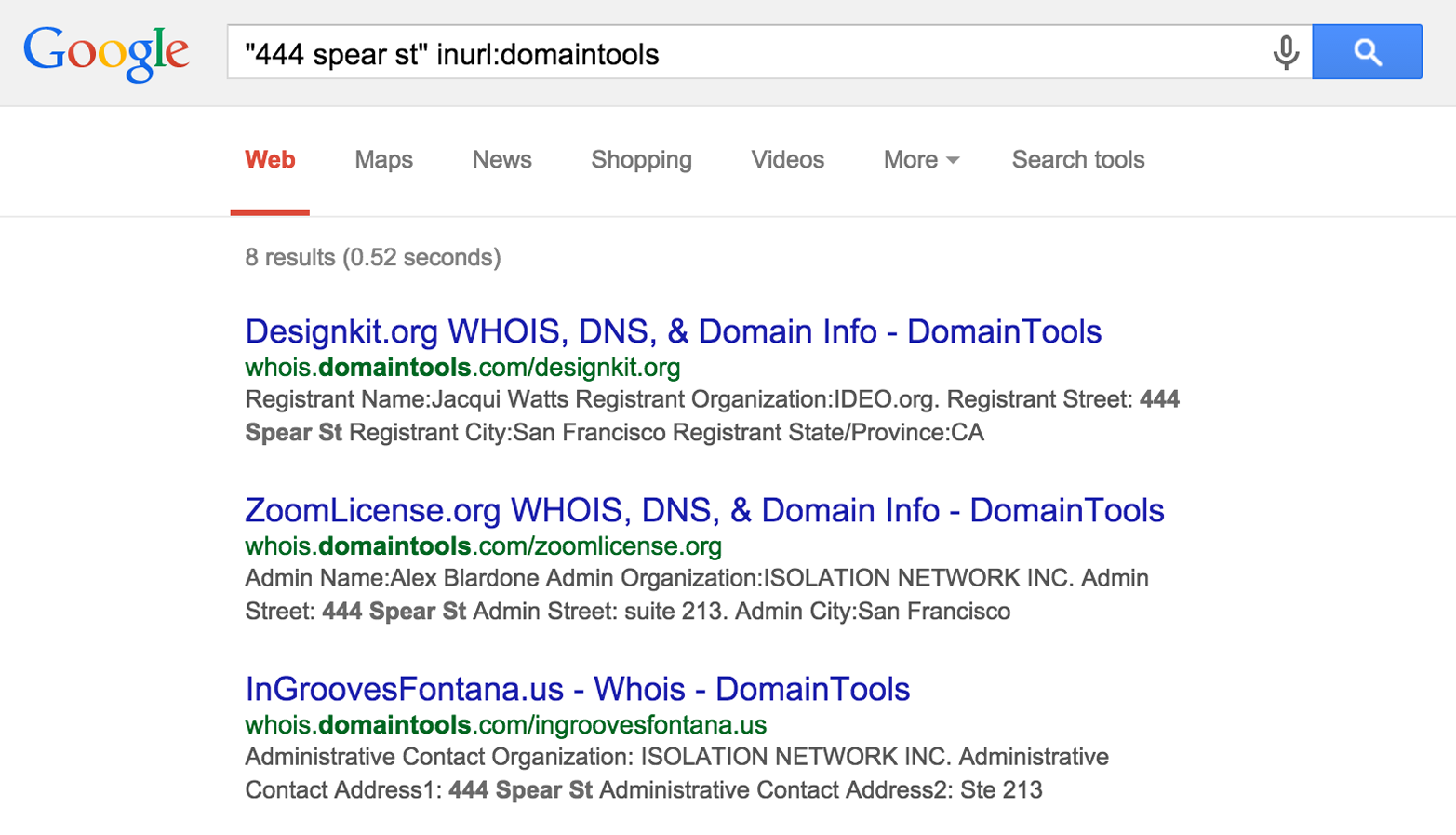

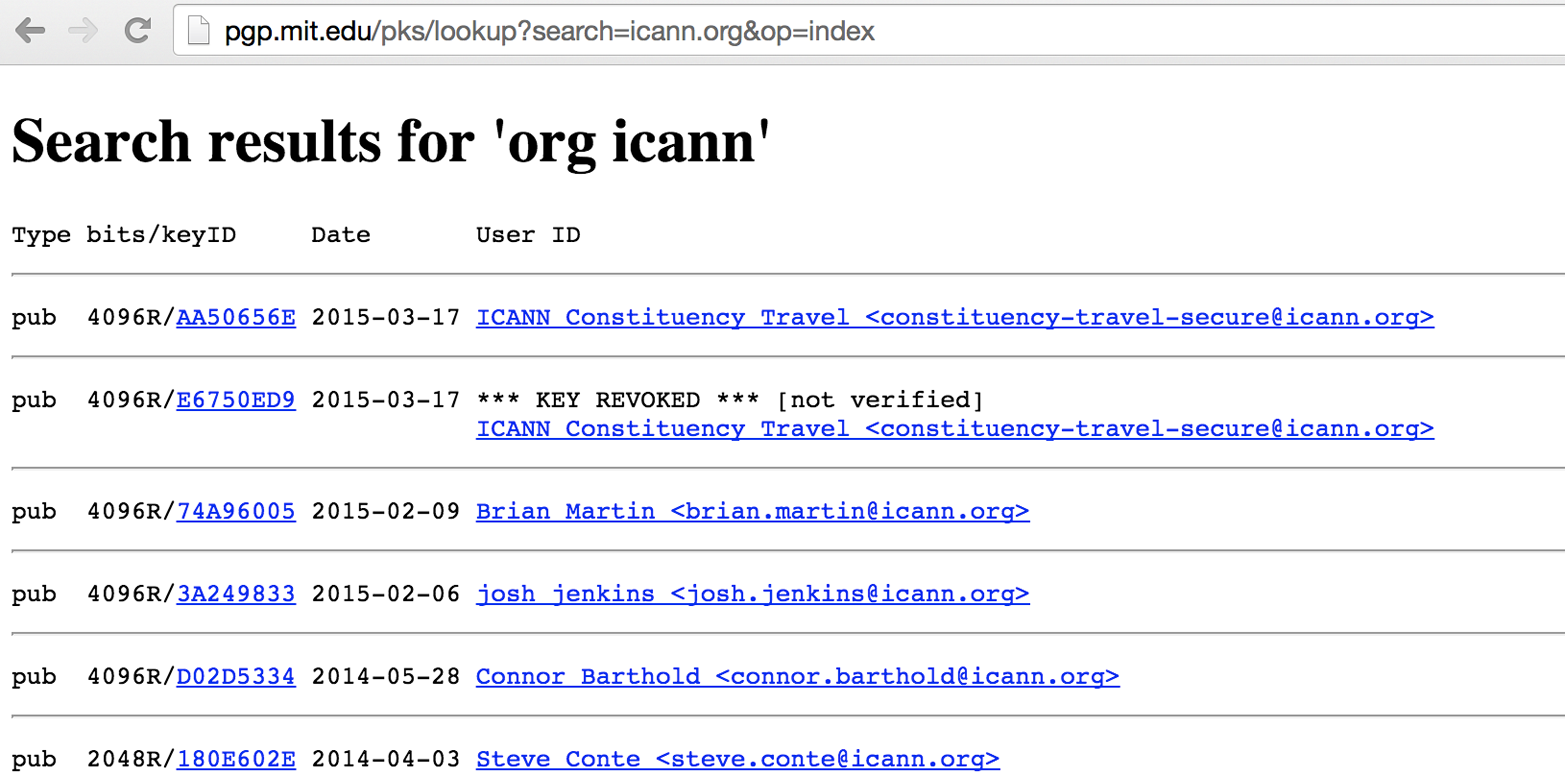

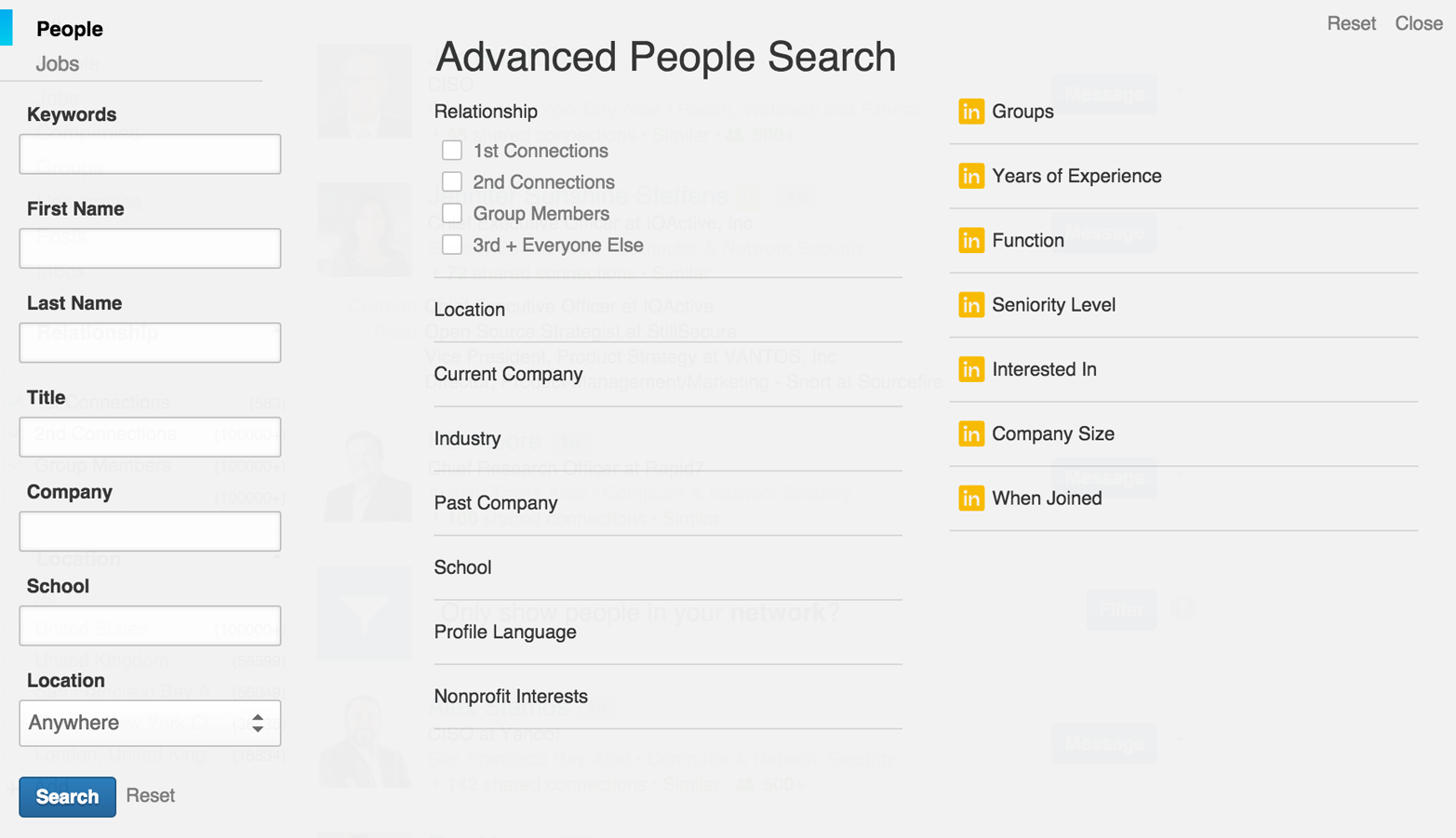

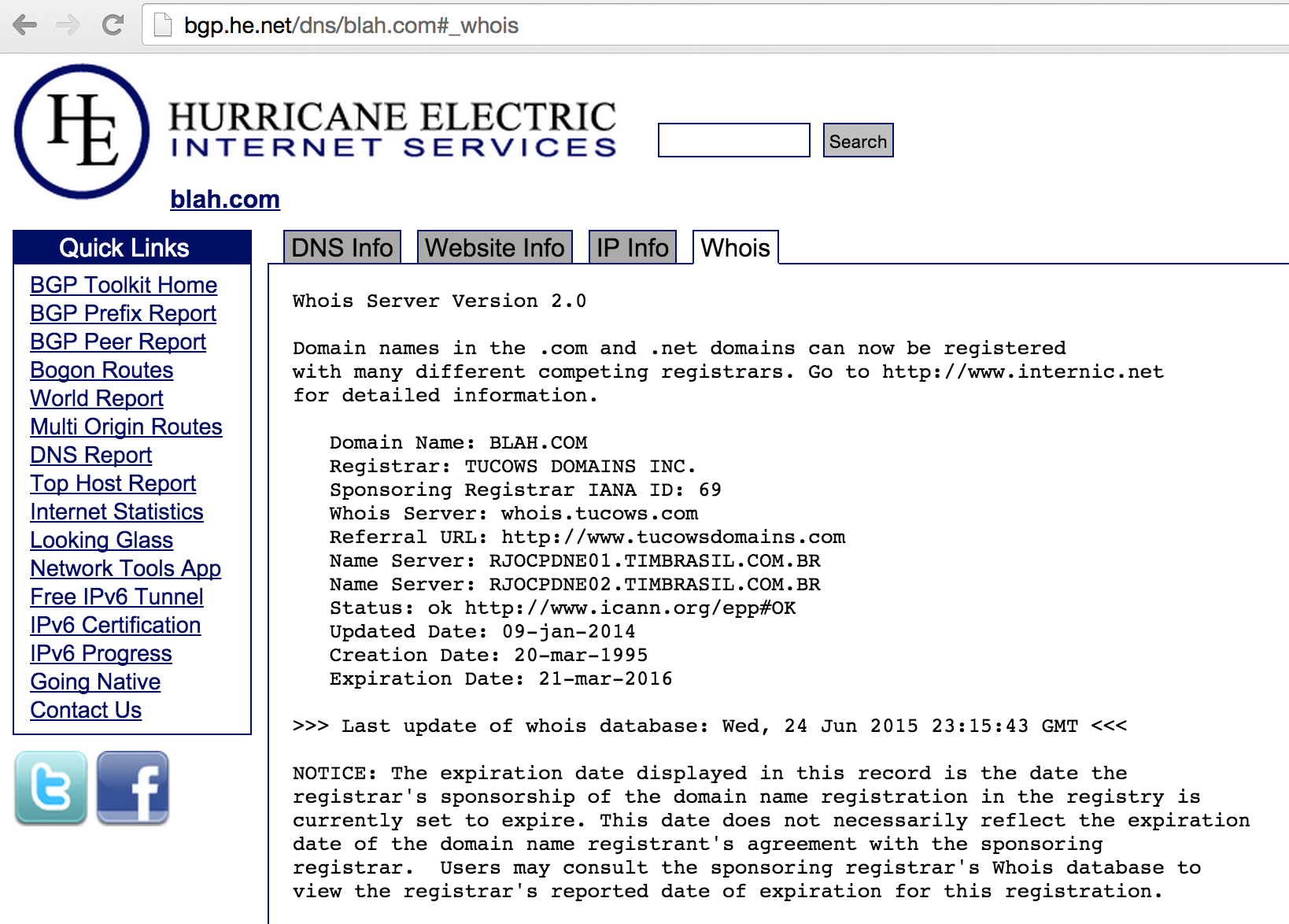

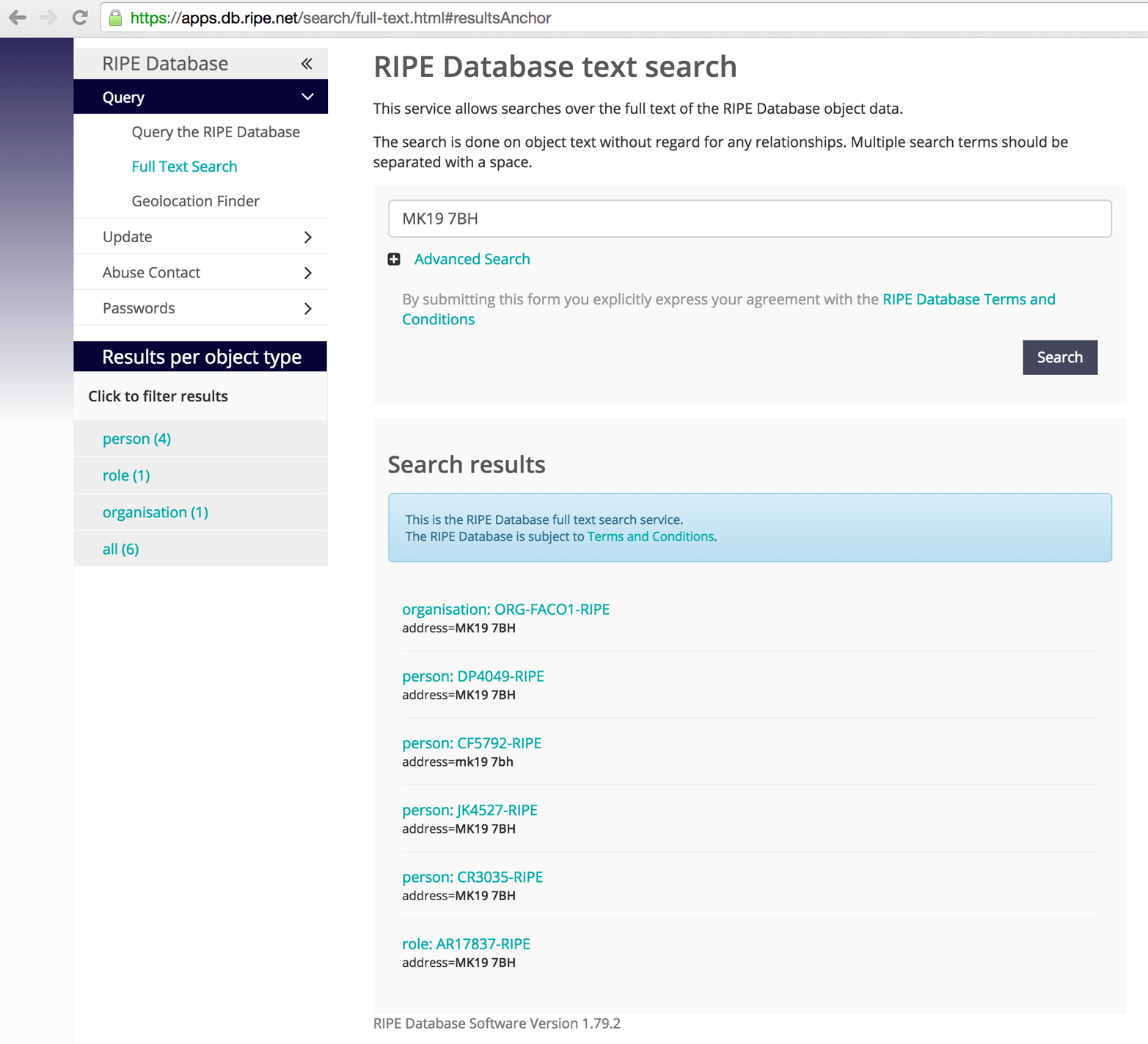

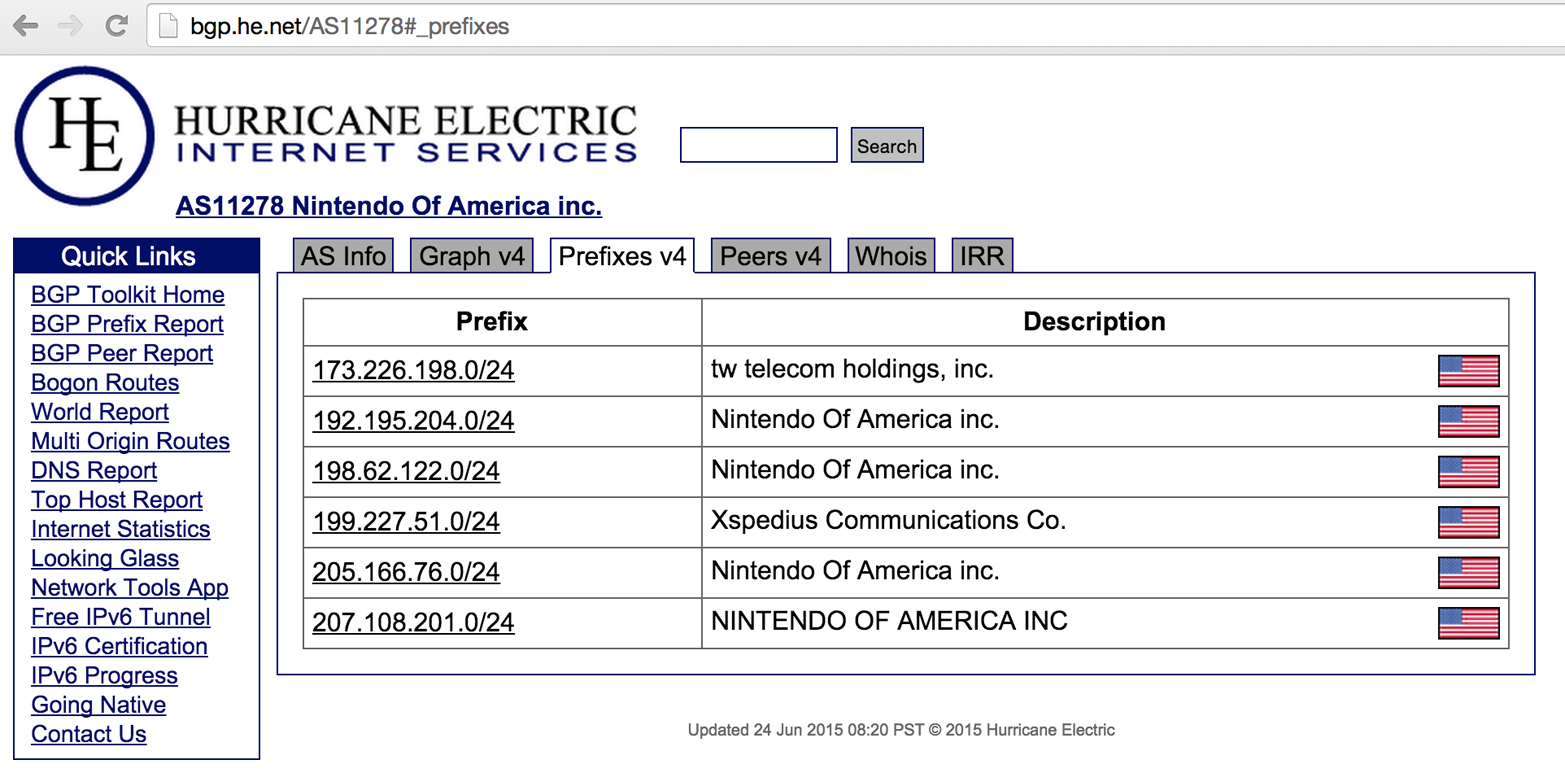

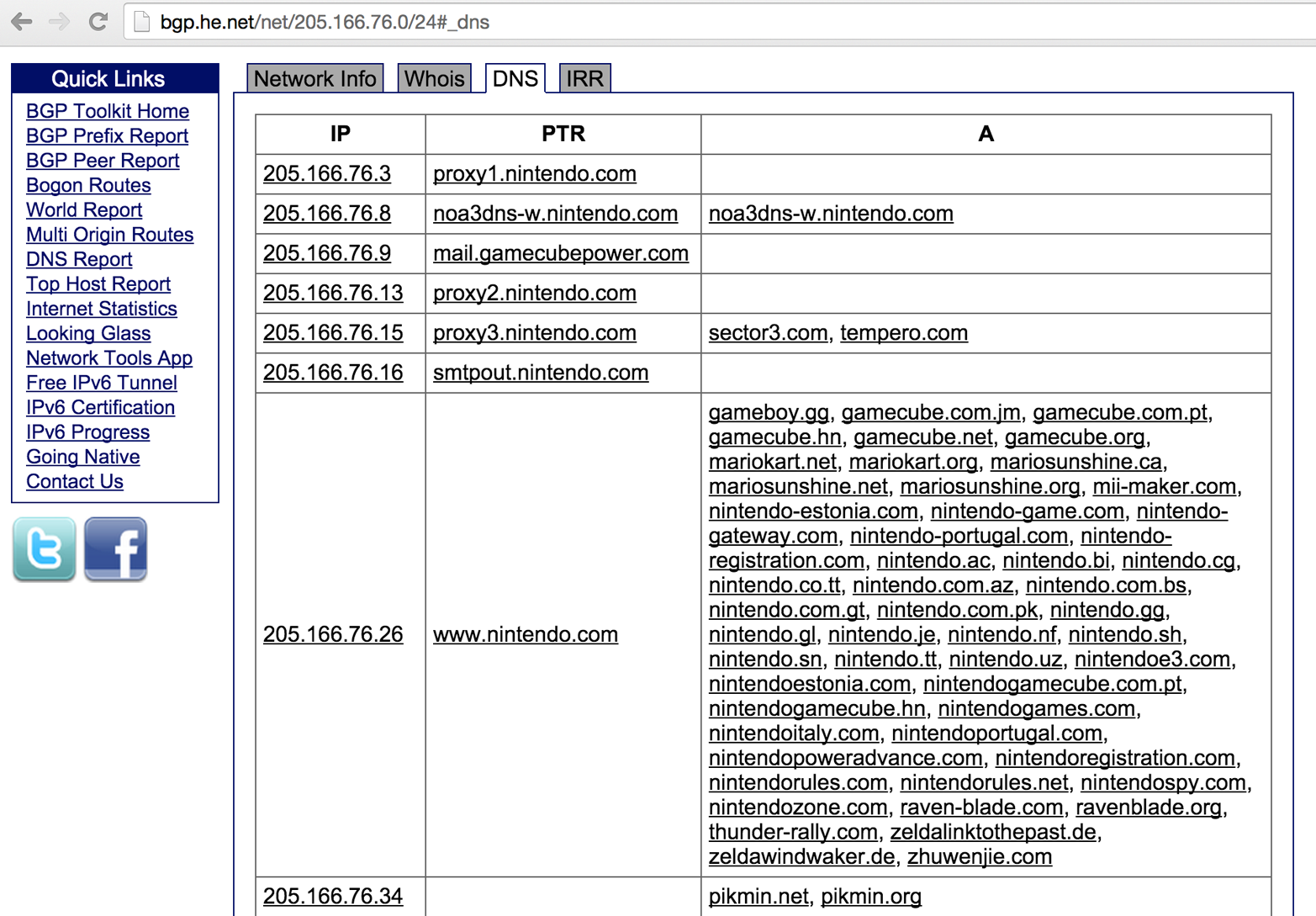

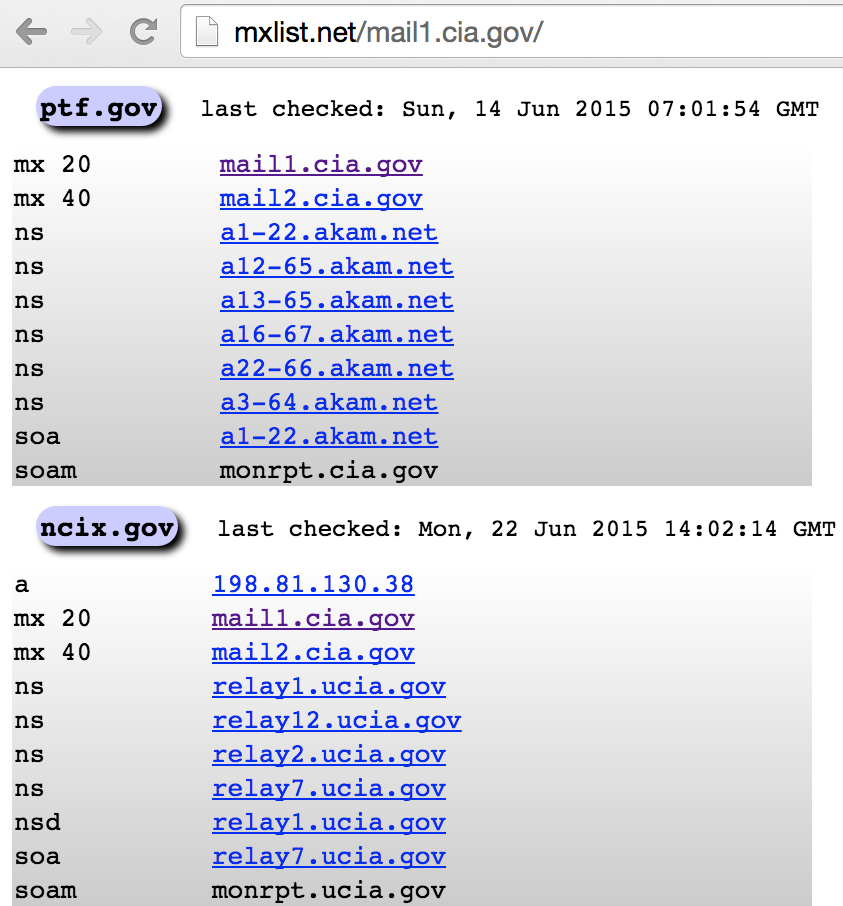

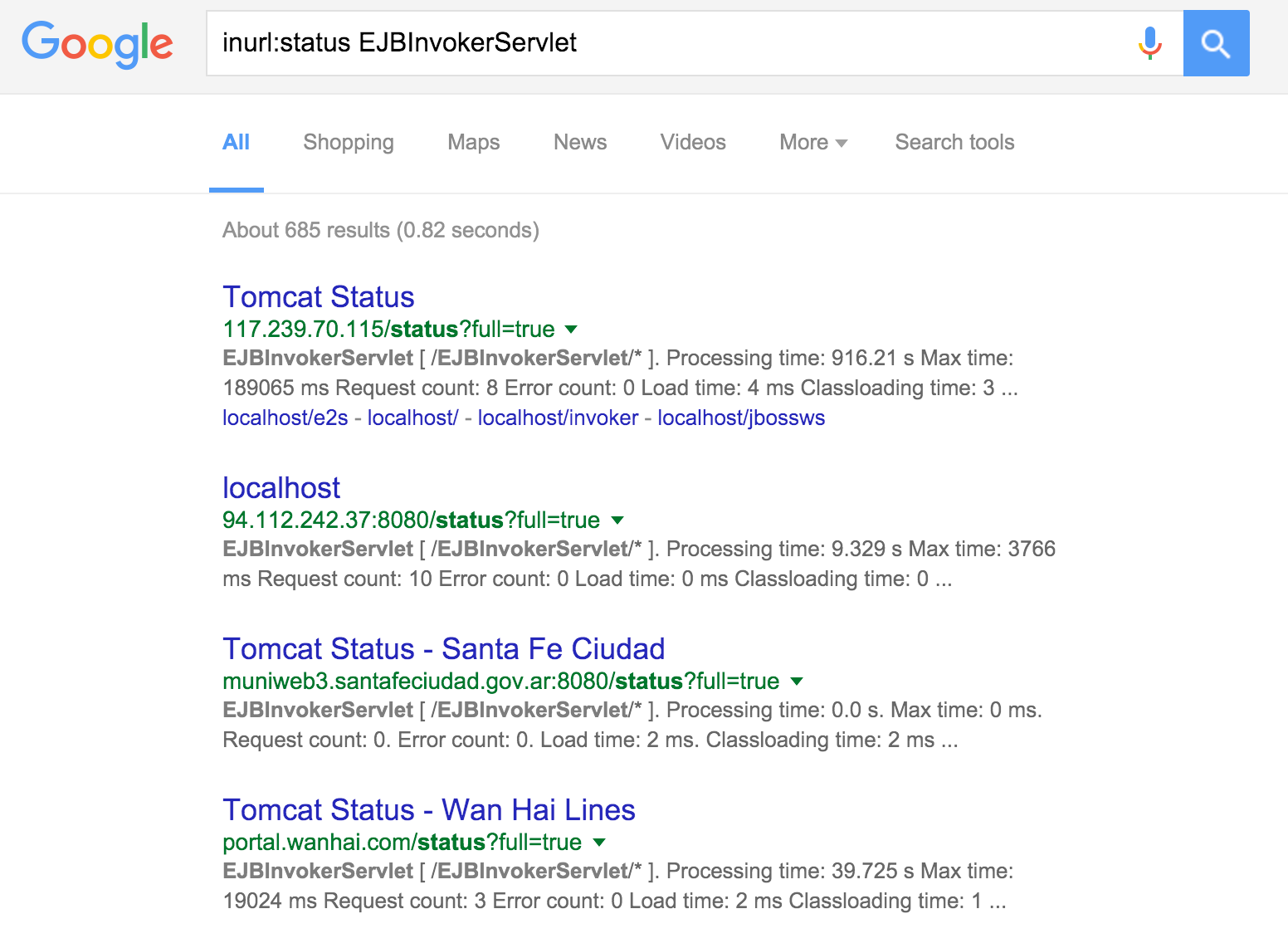

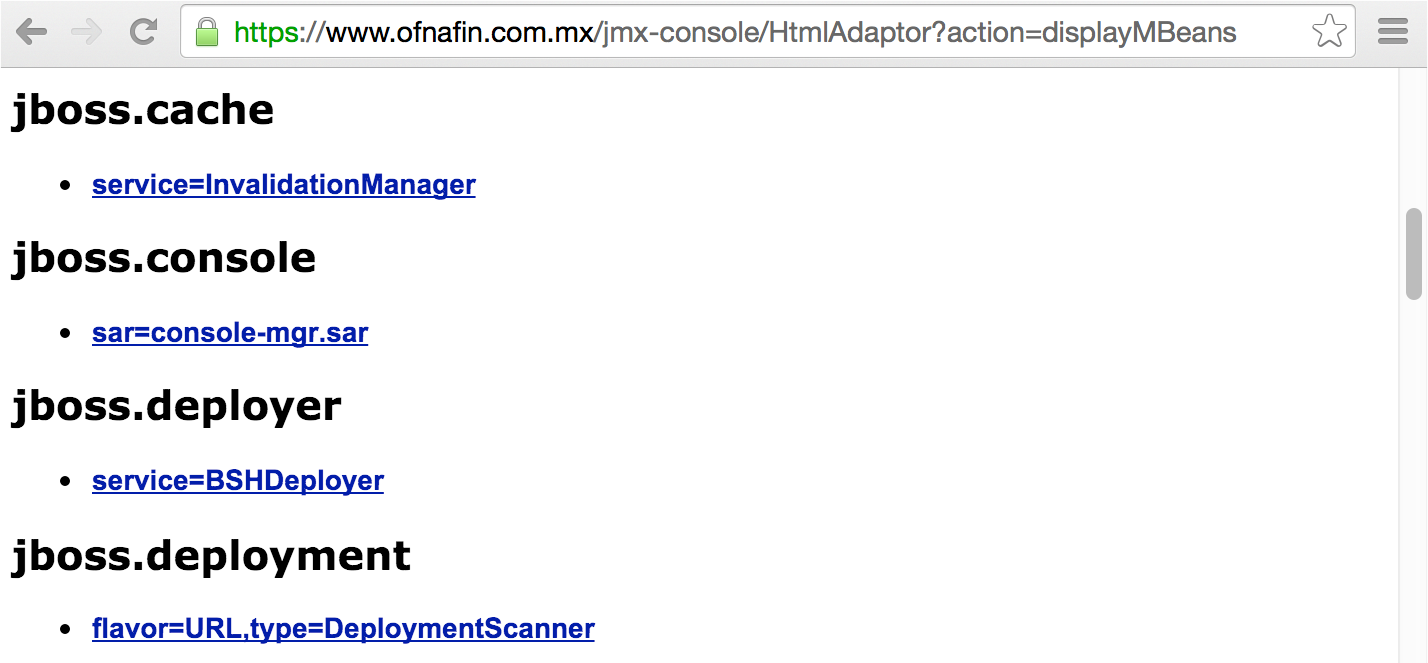

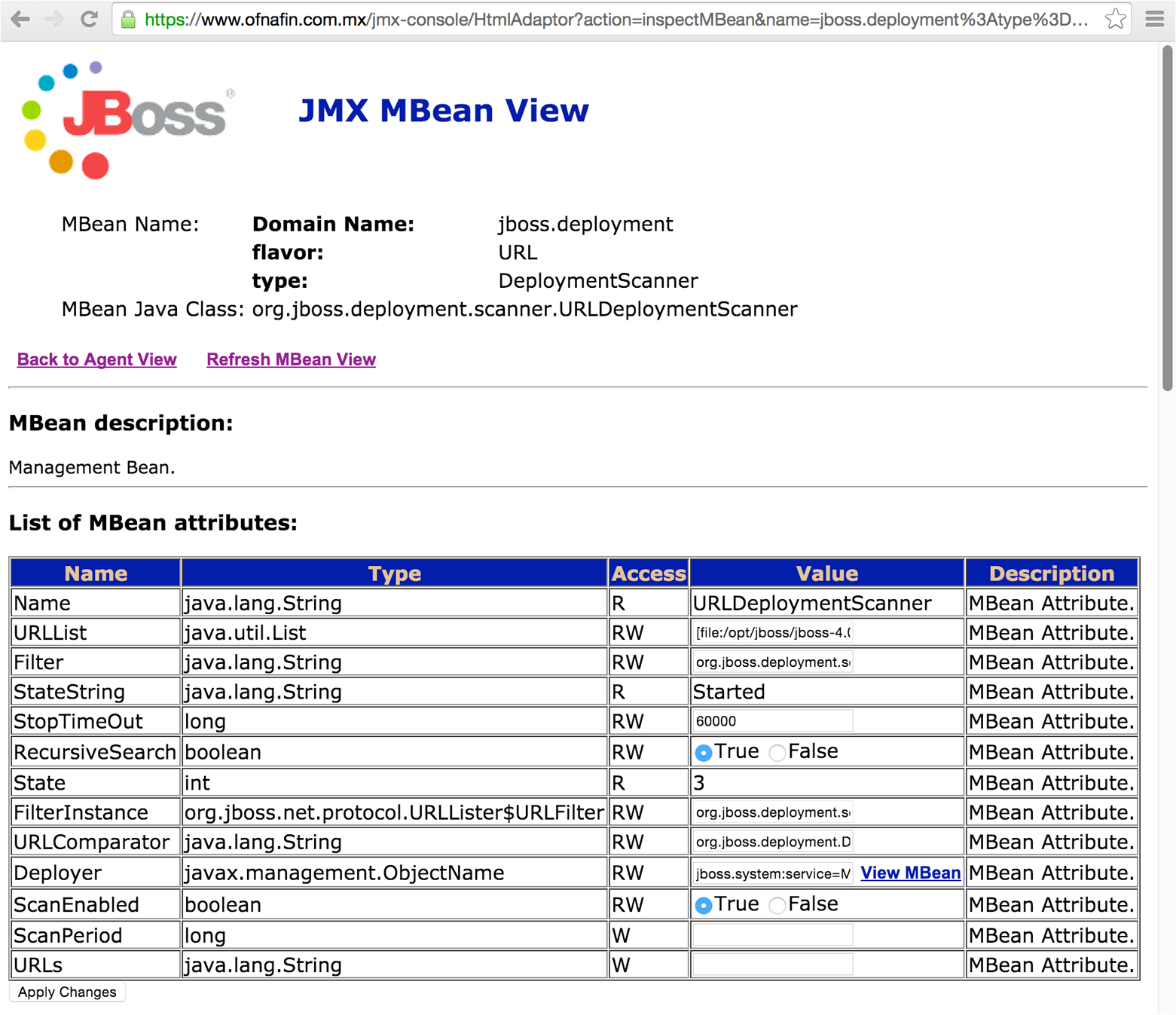

You can adopt different tactics to identify hosts, networks, and users of interest. Attackers map the target environment by using open sources (e.g., web search engines, WHOIS databases, and DNS servers) without direct network interaction through port scanning.

Reconnaissance often uncovers hosts that aren’t properly fortified. Determined attackers invest time in identifying peripheral networks and hosts, whereas organizations often concentrate their efforts on securing obvious public systems (such as public web and mail servers). Neglected hosts lying off the beaten track are ripe for the picking.

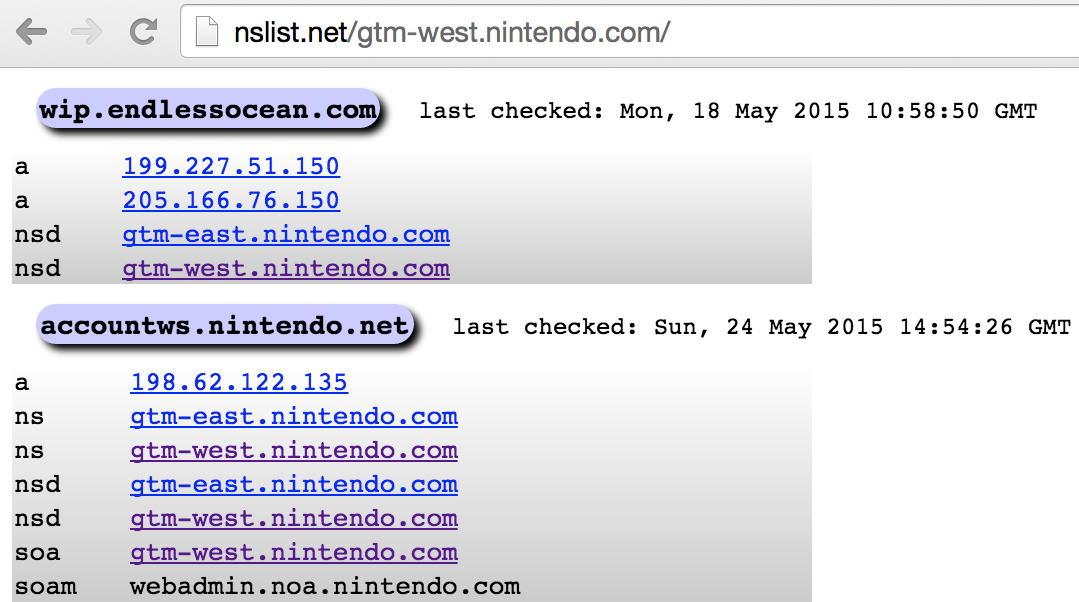

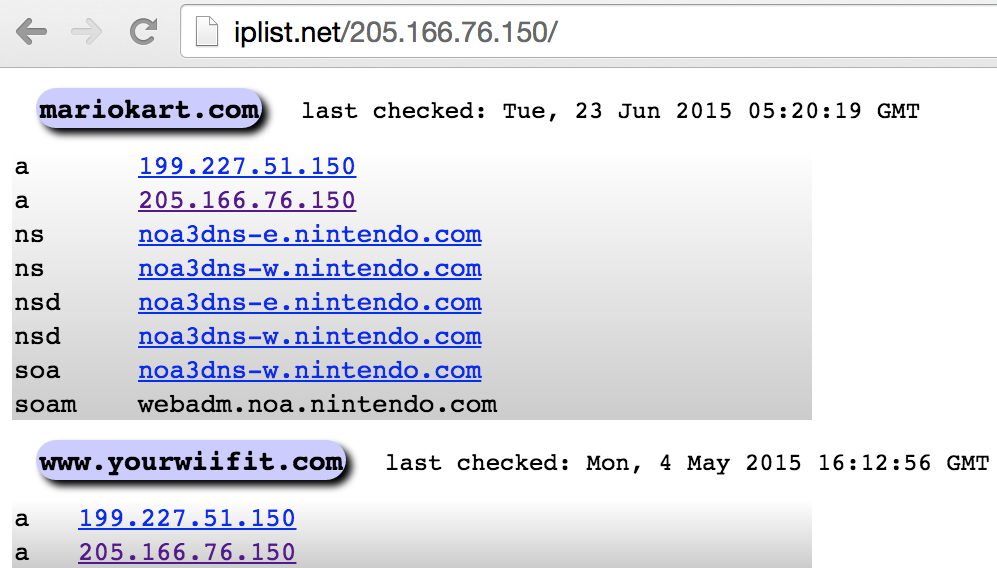

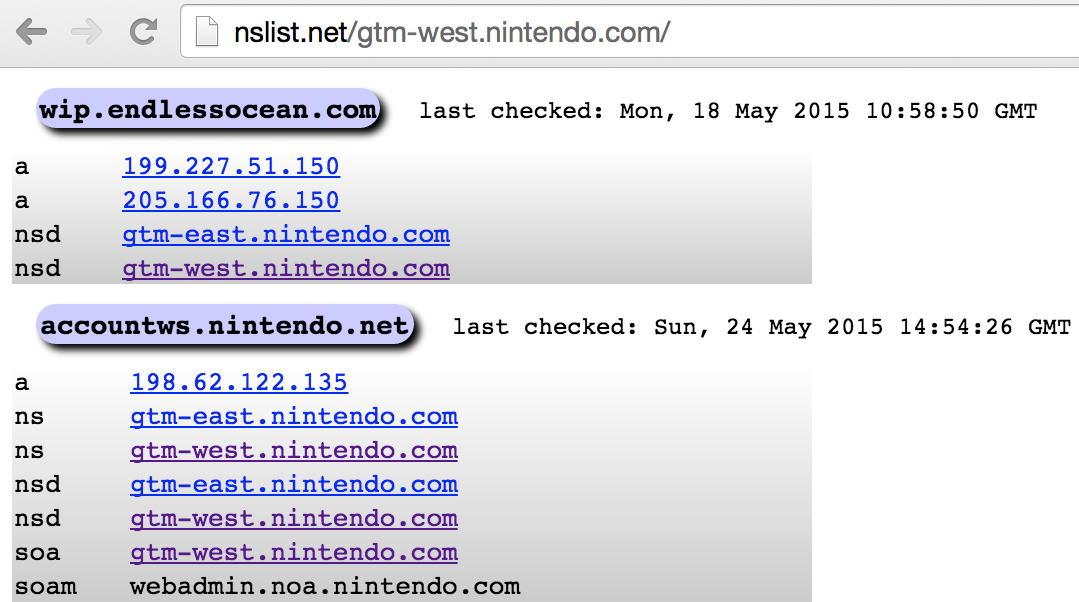

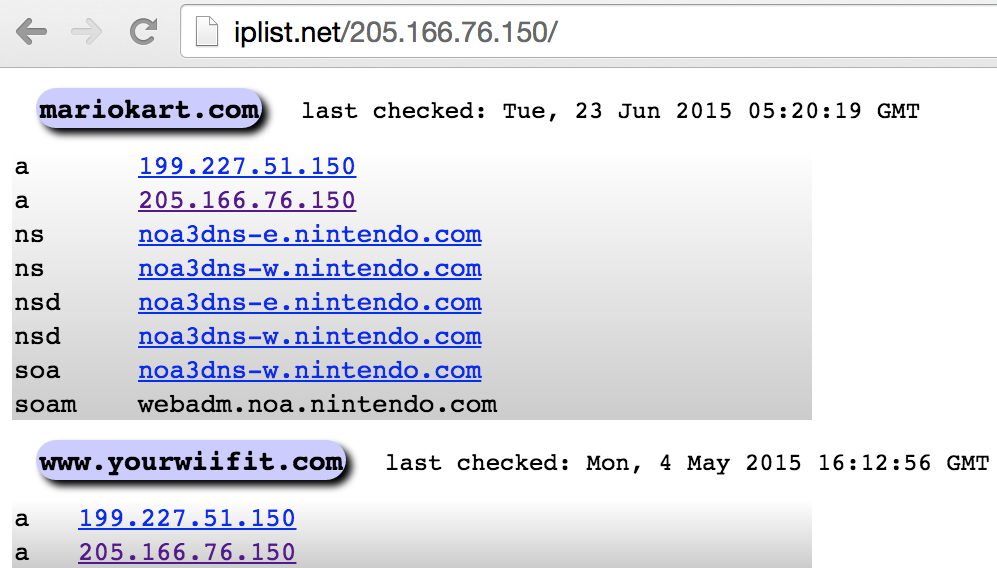

Useful pieces of information gathered through reconnaissance include details of Internet-based network blocks and internal IP addresses. Through DNS and WHOIS querying, you can map the networks of a target organization, and understand relationships between physical locations.

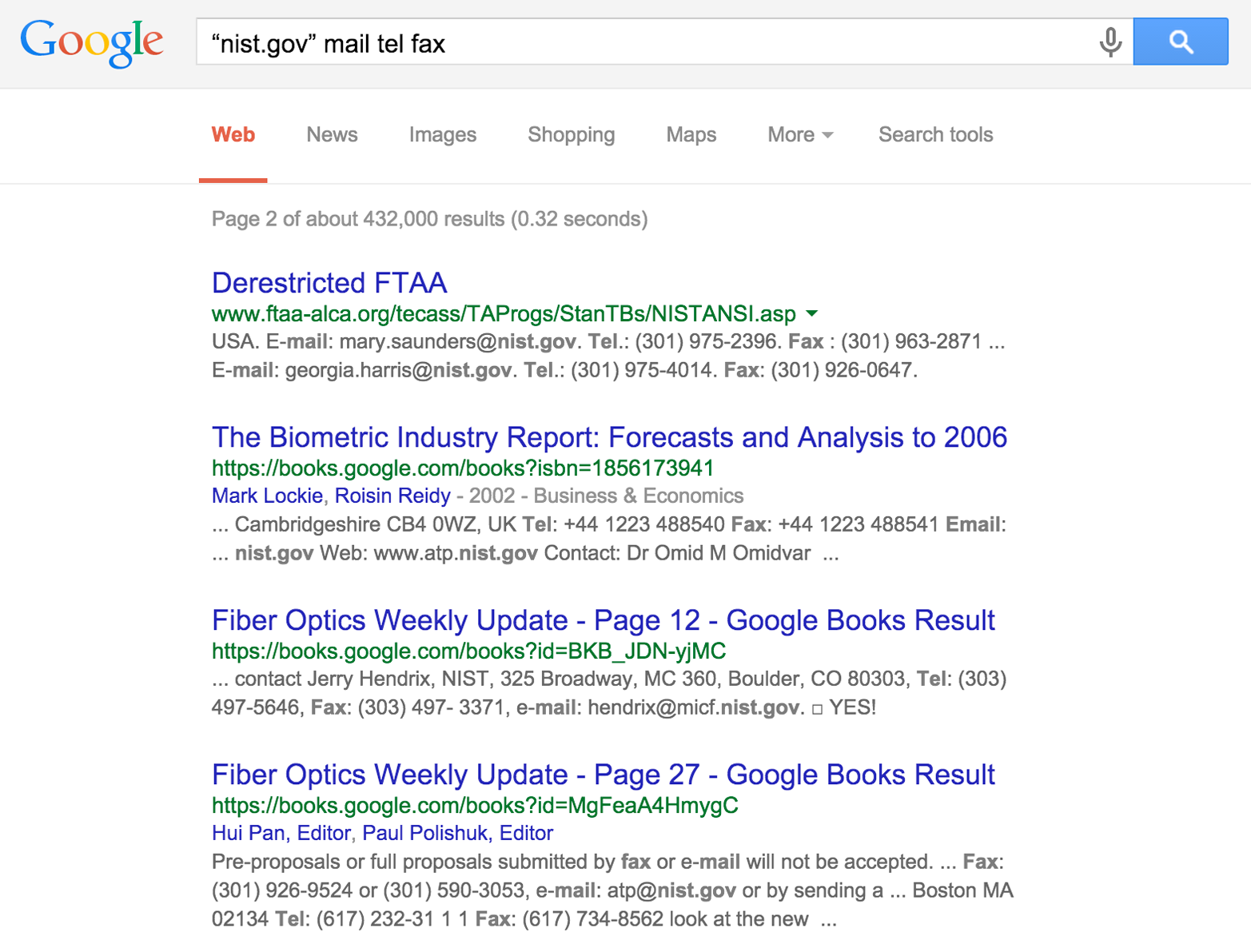

This information is fed into the vulnerability scanning and penetration testing phases to identify exploitable flaws. Further reconnaissance involves extracting user details (e.g., email addresses, telephone numbers, and usernames) that can be used during brute-force password grinding and social engineering phases.

Upon identifying IP blocks of interest, attackers carry out bulk scanning to identify accessible network services that can later be exploited to achieve particular goals—be it code execution, information leak, or denial of service. Network scanning tools (e.g., Nmap, Nessus, Rapid7 Nexpose, and QualysGuard) perform service fingerprinting, probing, and testing for known issues.

Useful information gathered through vulnerability scanning includes details of exposed network services and peripheral information (such as the ICMP messages to which hosts respond, and insight into firewall ACLs). Known weaknesses and exposures are also reported by scanning tools, which you can then investigate further.

Vulnerabilities in software are sometimes disclosed through public Internet mailing lists and forums, but are increasingly sold to private organizations, such as the Zero Day Initiative (ZDI), which in turn responsibly disclose issues to vendors and notify paying subscribers. According to Immunity Inc., on average, a zero-day bug has a lifespan of 348 days before a vendor patch is made available.

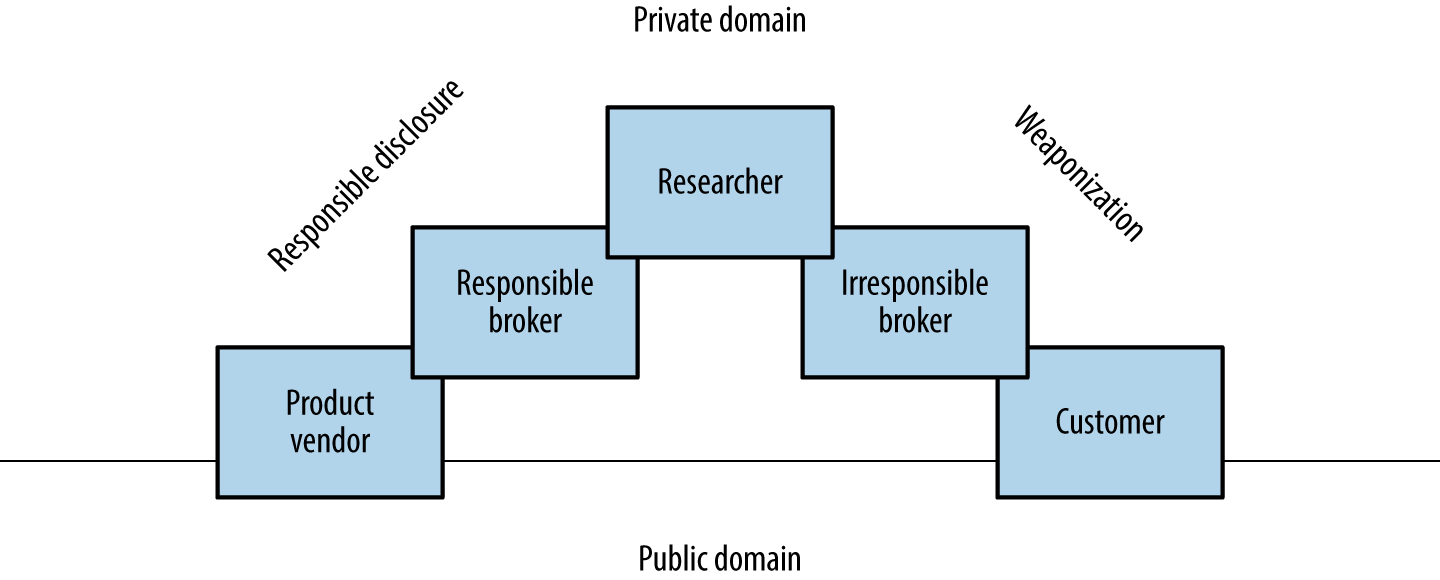

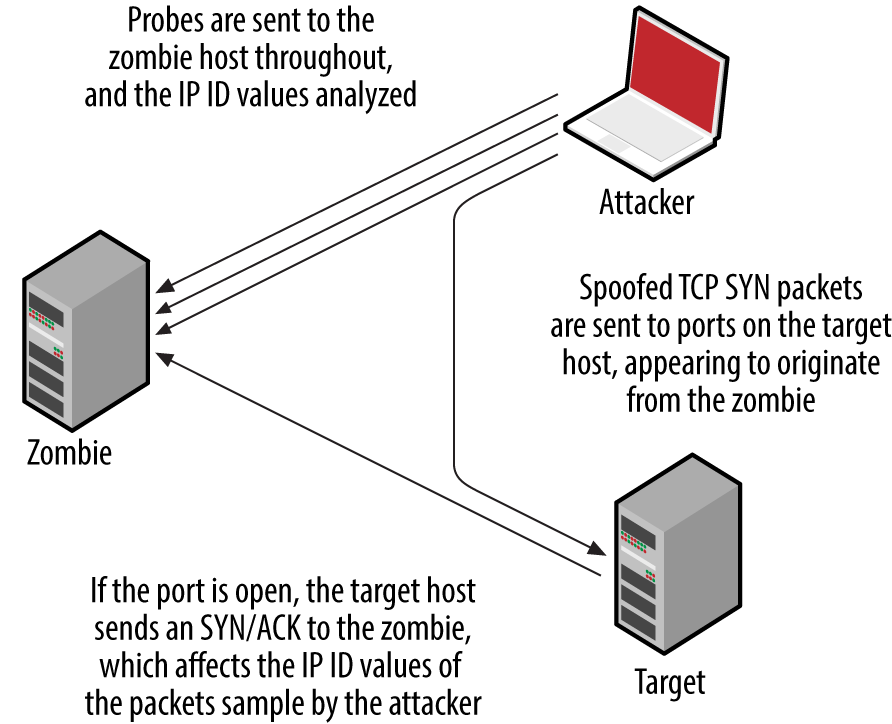

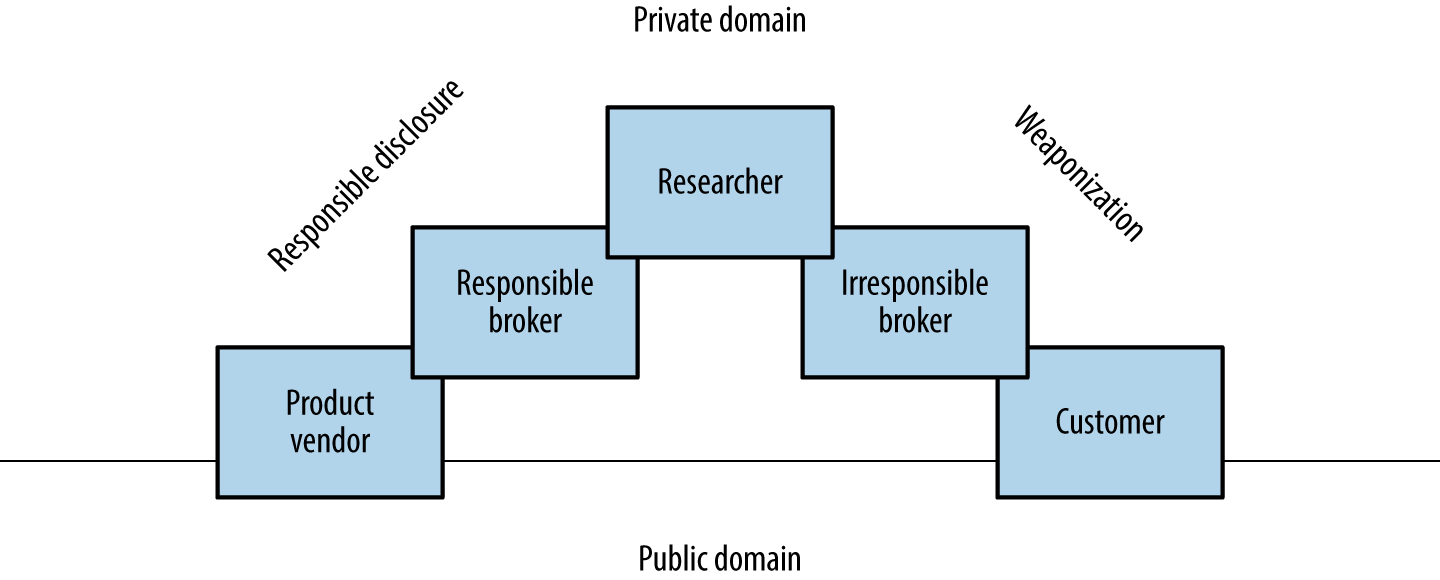

Many brokers do not notify product vendors of vulnerabilities, and some provide commercially supported zero-day exploits to their customers. Between responsible disclosure, zero-day abuse, and the public discussion of known flaws, vulnerability details are fragmented, as depicted by Figure 2-1.

To effectively report vulnerabilities within an environment, a security professional would need to know the bugs within both private and public domains. Many do not have access to private feeds, and base their assessment on public knowledge, augmented by their own research.

The following open sources are useful when investigating potential vulnerabilities:

ZDI and Google’s Project Zero operate publicly accessible bug trackers that detail upcoming disclosures and unpatched vulnerabilities.1 Open projects including OpenSSL and the Linux kernel also have public bug trackers that reveal useful details of unpatched flaws. During testing, it is worth reviewing both bug trackers and release notes to understand known weaknesses within software packages.

Many government agencies and defense industrial base entities consume private vulnerability information via brokers and sources including ZERODIUM, Exodus Intelligence, Netragard, and ReVuln. These organizations are known to provide details of unpatched bugs to subscribers.

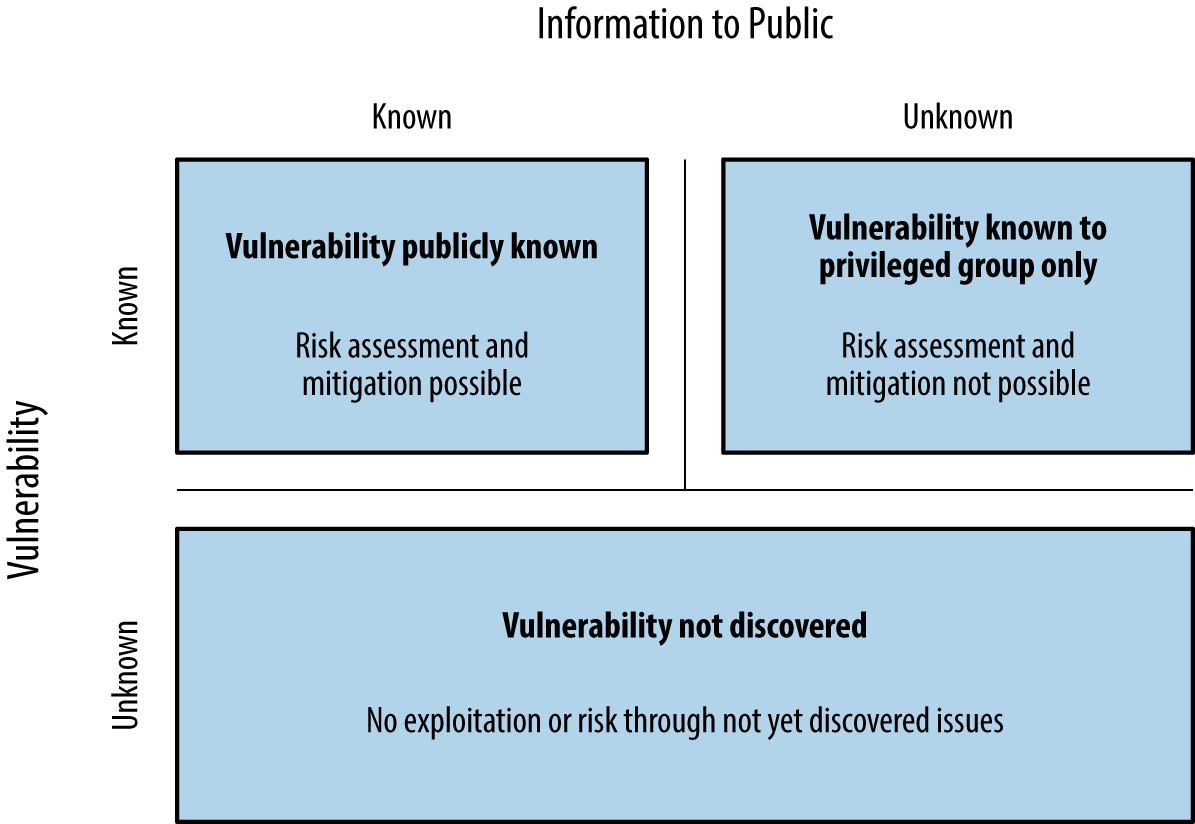

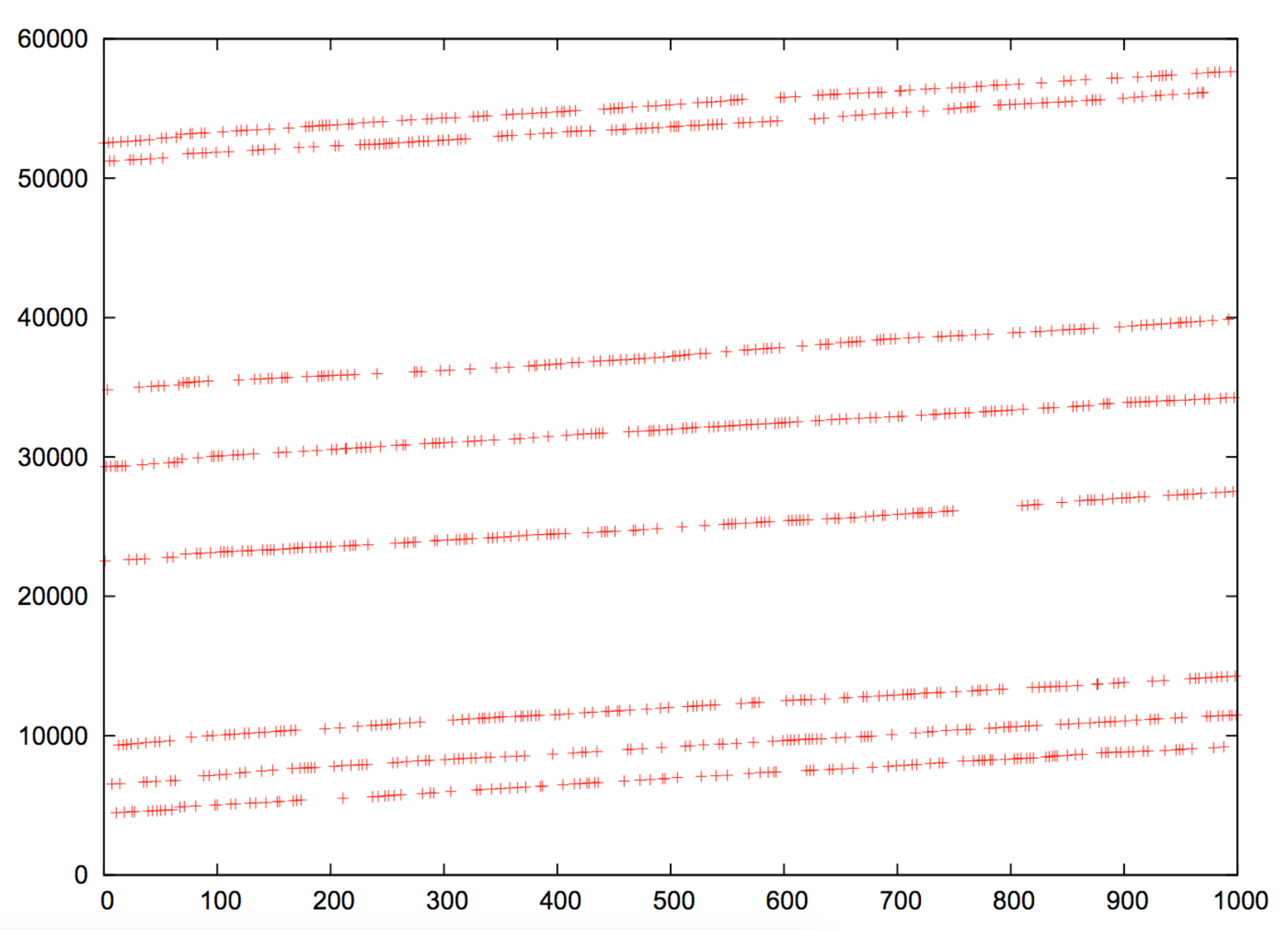

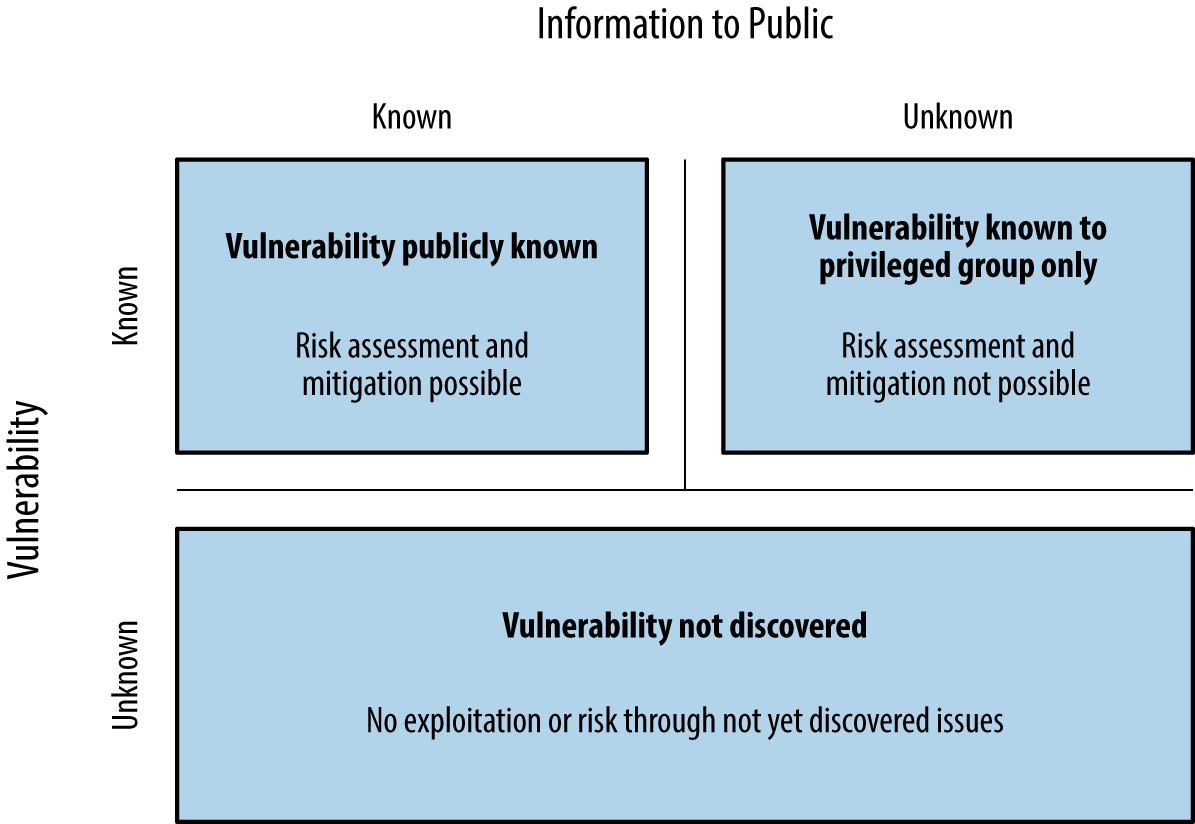

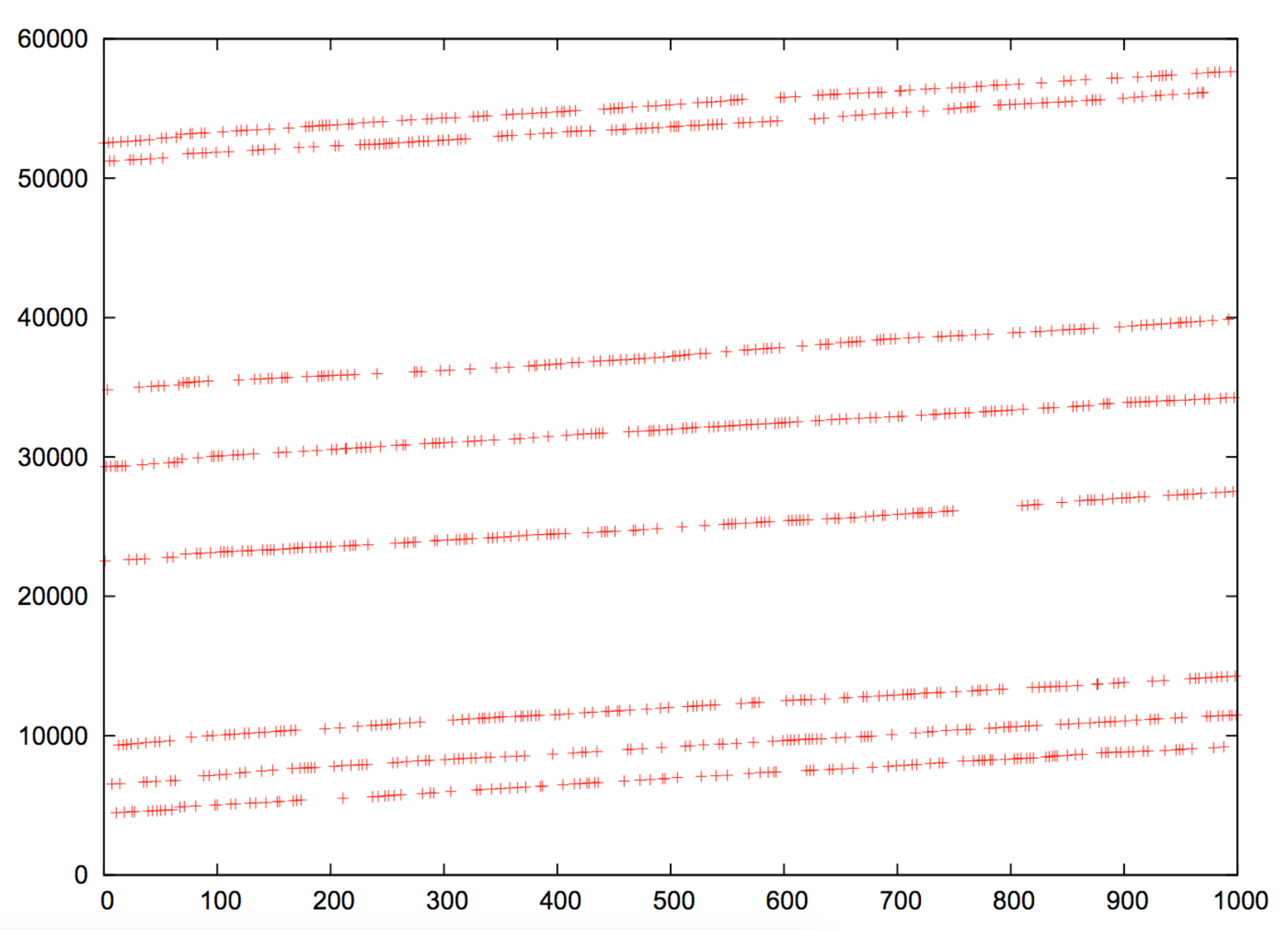

Stefan Frei of NSS Labs published a paper on this topic.2 Within his paper, Frei discussed vulnerabilities known to a privileged group, as demonstrated in Figure 2-2.

Based on disclosures regarding the US government’s budget for zero-day exploit purchases, Frei estimated that at least 85 known unknowns exist on any given day. Depending on the policy of each party involved, these bugs might never be disclosed to the vendor.

Vlad Tsyrklevich’s “Hacking Team: A Zero-Day Market Case Study” provides insight into the private market for vulnerability information, including prices of exploits and details of unpatched flaws in packages including Abode Flash, Microsoft Office, Internet Explorer, and Oracle Database.

Attackers can exploit flaws in exposed logic for gain. Depending on their goals, they might take advantage of vulnerabilities to secure privileged network access, persistence, or obtain sensitive information.

During a penetration test, qualification of vulnerabilities usually involves exploitation. Robust commercially supported frameworks provide flexible targeting of vulnerable components within a given environment (supporting different operating systems and configurations), which allows you to define specific exploit payloads. Modules developed by third parties extend these frameworks, providing support for Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition (SCADA) and other technologies. Popular exploitation frameworks are as follows:

Within NIST SP 800-115, exploitation tasks fall under the category of Target Vulnerability Validation Techniques. As a tester (with correct authorization) you might undertake password cracking and social engineering, and qualify vulnerabilities through use of exploitation frameworks and tools.

The assessment process is iterative, and new details (e.g., IP address blocks, hostnames, and credentials) are often fed back to earlier workflow elements. Figure 2-3 describes the process and data passed between individual testing elements.

To support both Linux and Windows-based testing tools, it is best to use virtualization software (e.g., VMware Fusion for Apple OS X or VMware Workstation for Windows). Useful native applications within Linux include showmount, dig, and snmpwalk. You also can build specific utilities to attack uncommon network protocols and applications.

Kali Linux is a penetration testing distribution that you can run easily within a virtualized environment. Kali contains many of the utilities found within this book, including Metasploit, Nmap, Burp Suite, and Nikto. The Kali Linux documentation details installation, and two recently published books describe individual tools, as follows:

Kali Linux: Assuring Security by Penetration Testing, by Tedi Heriyanto, Lee Allen, and Shakeel Ali (Packt Publishing, 2014)

Mastering Kali Linux for Advanced Penetration Testing, by Robert W. Beggs (Packt Publishing, 2014)

If you use Apple OS X for instance, running Microsoft Windows and Kali Linux within VMware Fusion will be sufficient for most engagements. Offensive Security maintains custom Kali Linux VMware and ARM images, which support VMware Tools (which make it possible for you to copy and paste between the virtualized guest and your host system), and ARM platforms such as the Chromebook.

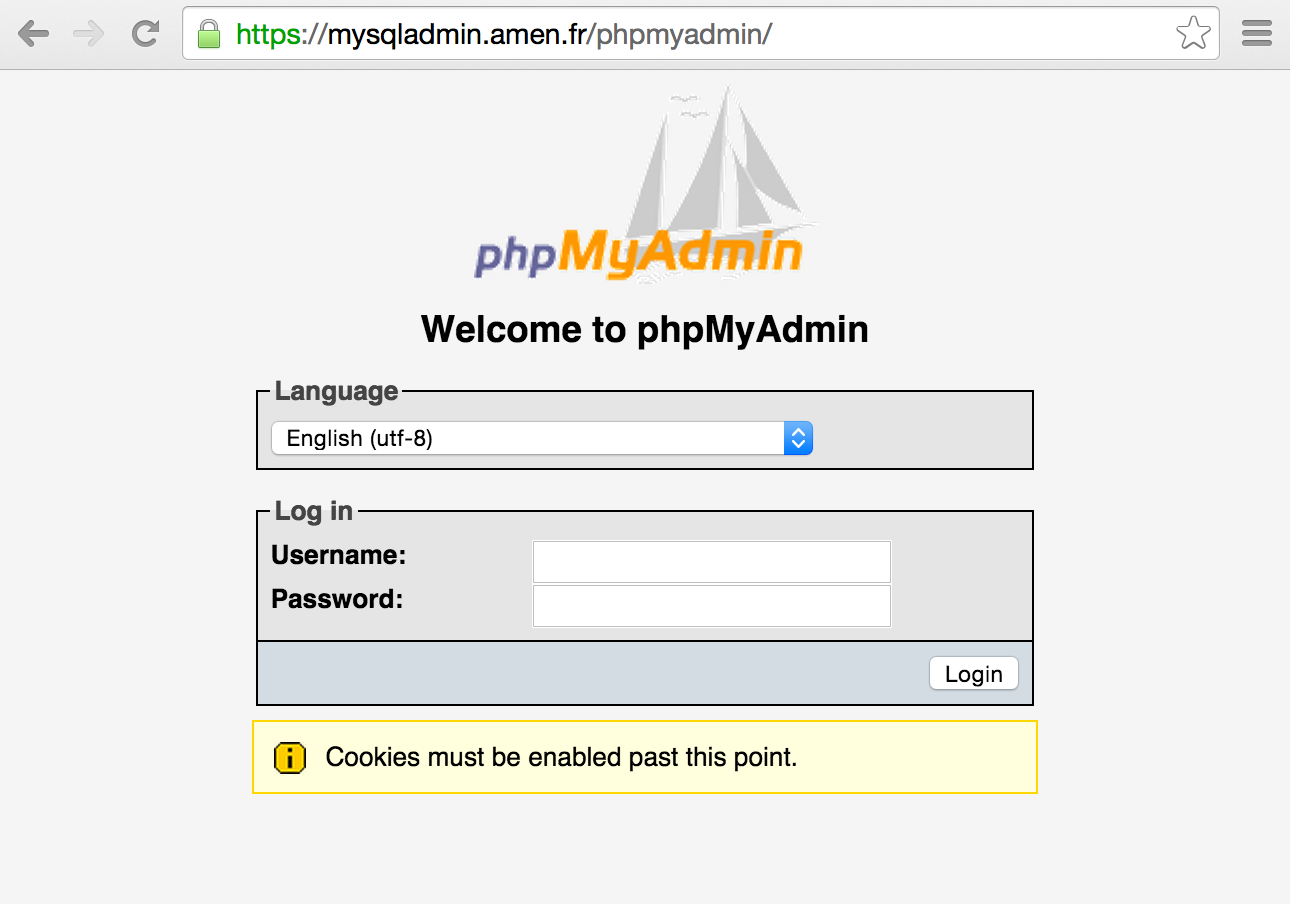

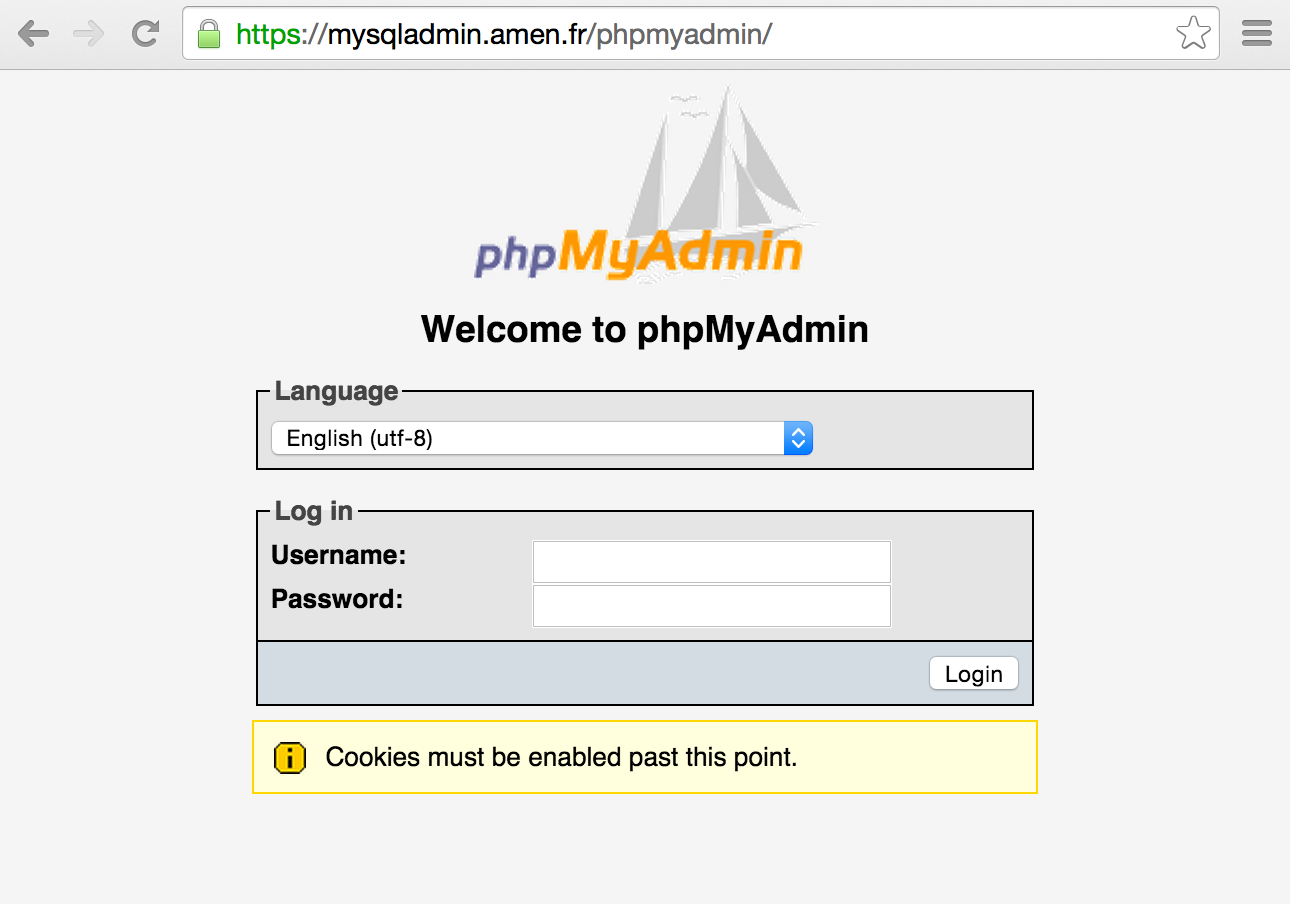

To test utilities in a controlled environment, use a vulnerable server image to ensure that each tool is working correctly. Rapid7 prepared a virtual machine image known as Metasploitable 2,3 which can be compromised through many vectors, including:

Backdoors within packages including FTP and IRC

Vulnerable Unix RPC services

SMB privilege escalation

Weak user passwords

Web application server issues (via Apache HTTP Server and Tomcat)

Web application vulnerabilities (e.g., phpMyAdmin and TWiki)

Tutorials and walkthroughs are available online that describe the utilities, Metasploit modules, and commands that can be used to evaluate and exploit flaws within the virtual machine. Here are two useful resources:

Computer Security Student (navigate to Security Tools→Metasploitable Project→Exploits)

You can find many other exploitable virtual machine images online at VulnHub. For the purposes of web application testing, take a look at the OWASP vulnerable web applications directory and PentesterLab in particular.

1 See Zero Day Initiative’s upcoming advisories and Chromium bugs, respectively.

2 Stefan Frei, “The Known Unknowns & Outbidding Cybercriminals”, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, September 2014.

3 For more information, see the Metasploitable 2 Exploitability Guide.

Any time you try a decent crime, there are 50 ways to screw up.

If you think of 25 of them, you’re a genius. And you’re no genius.Mickey Rourke

Body Heat (1981)

Software engineers build increasingly elaborate systems without considering even half of the ways to screw up. Thanks to cloud computing and increasing layers of abstraction, unsafe products will persist, and the computer security business will remain a lucrative one for years to come.

Hacking is the art of manipulating a system to perform a useful action.

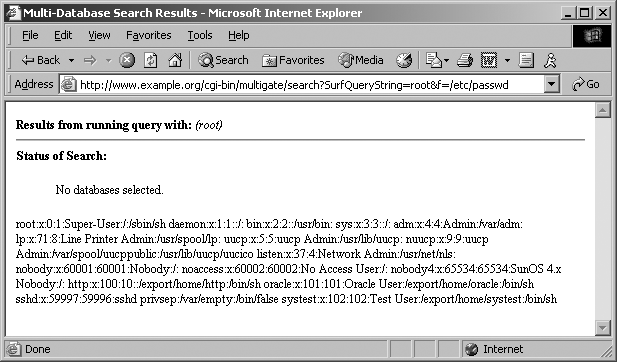

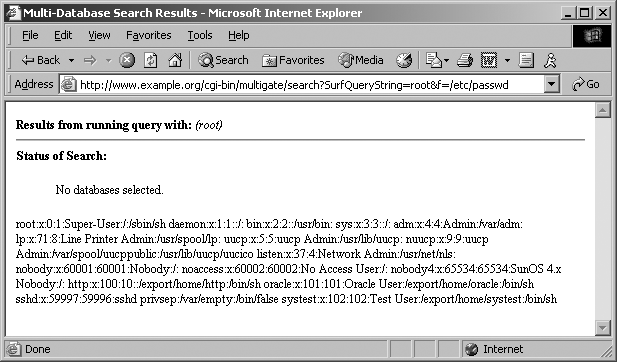

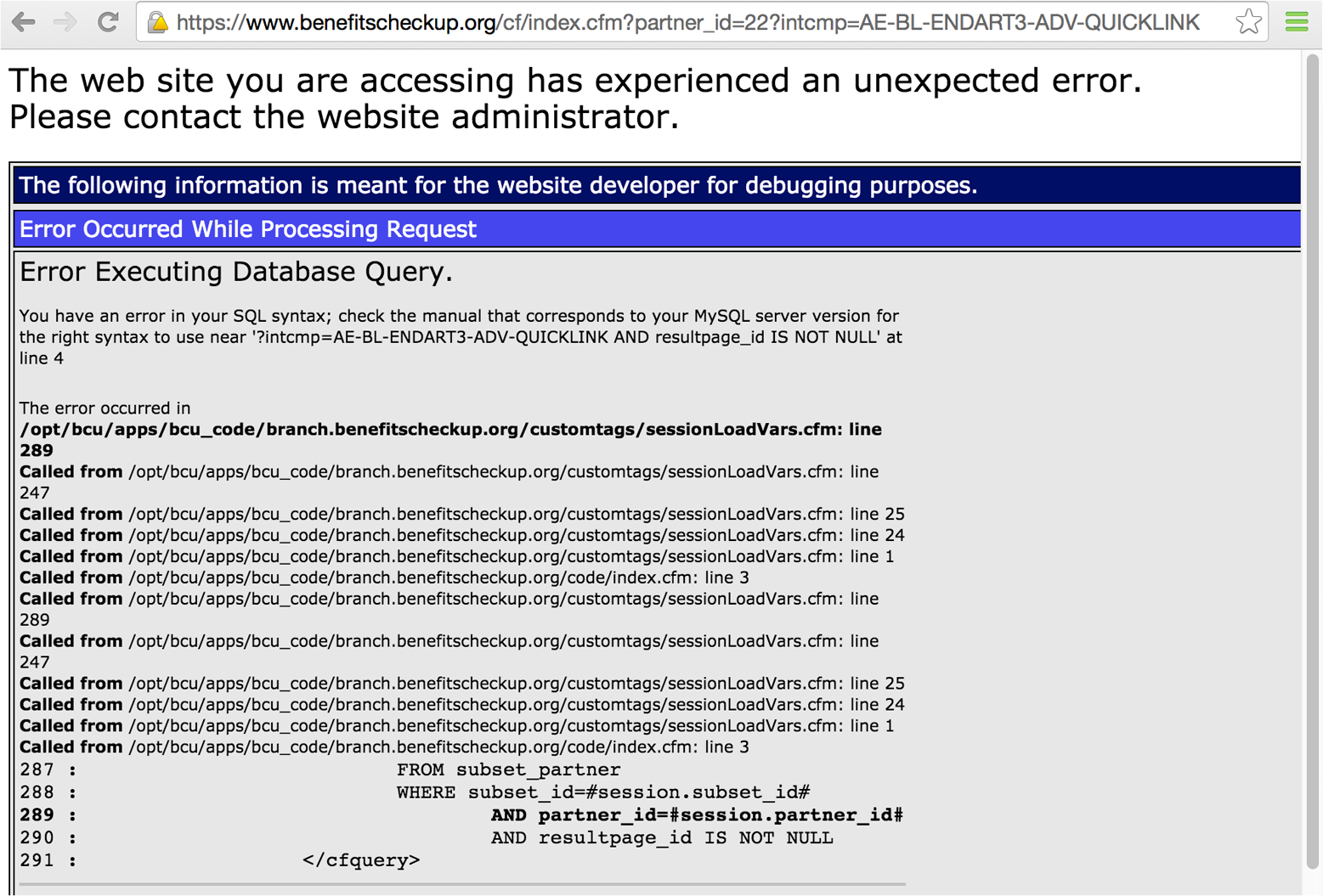

A basic example is that of the humble search engine, which cross-references user input with a database and returns the results. Processing occurs server-side, and by understanding the way in which these systems are engineered, an adversary can seek to manipulate the application and obtain sensitive content.

Decades ago, the websites of the US Pentagon, Air Force, and Navy had this very problem. A search engine called multigate accepted two arguments in particular: SurfQueryString and f. The contents of the server’s /etc/passwd file were revealed via a crafted URL, as shown in Figure 3-1.

These sites were defended at the network layer by firewalls and security appliances. However, by the very nature of the massive amount of information stored, a search engine was implemented, which introduced vulnerability within the application layer.

A useful way to consider the exploitation process is to think of a system being programmed by an adversary to perform a useful action. The individual programming tactics adopted are dependent on system components, features, and the attacker’s goals—such as data exposure, elevation of privilege, arbitrary code execution, or denial of service.

For more than 30 years, adversaries have exploited vulnerabilities in software, and vendors have worked to enhance the security of their products. Flaws will likely always exist in these increasingly elaborate systems thanks to insufficient quality assurance in particular.

Software vendors find themselves in a situation where, as their products become more complex, it is costly to make them safe. Static code review and dynamic testing of software is a significant undertaking that affects the bottom line and impacts go-to-market time.

In each successful attack against a computer system, an adversary took advantage of the available attack surface to achieve her goals. This surface often encompasses server applications, client endpoints, users, communication channels, and infrastructure. Each exposed component is fair game.

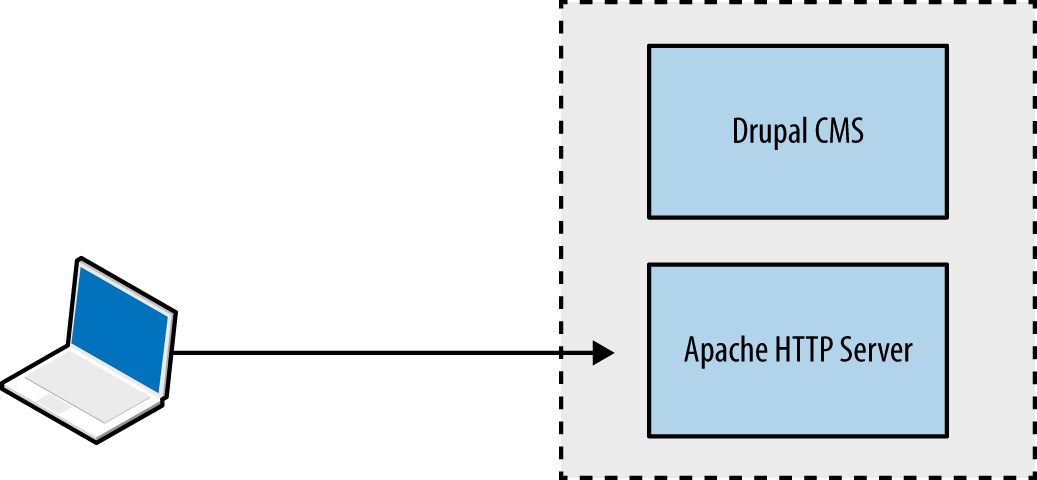

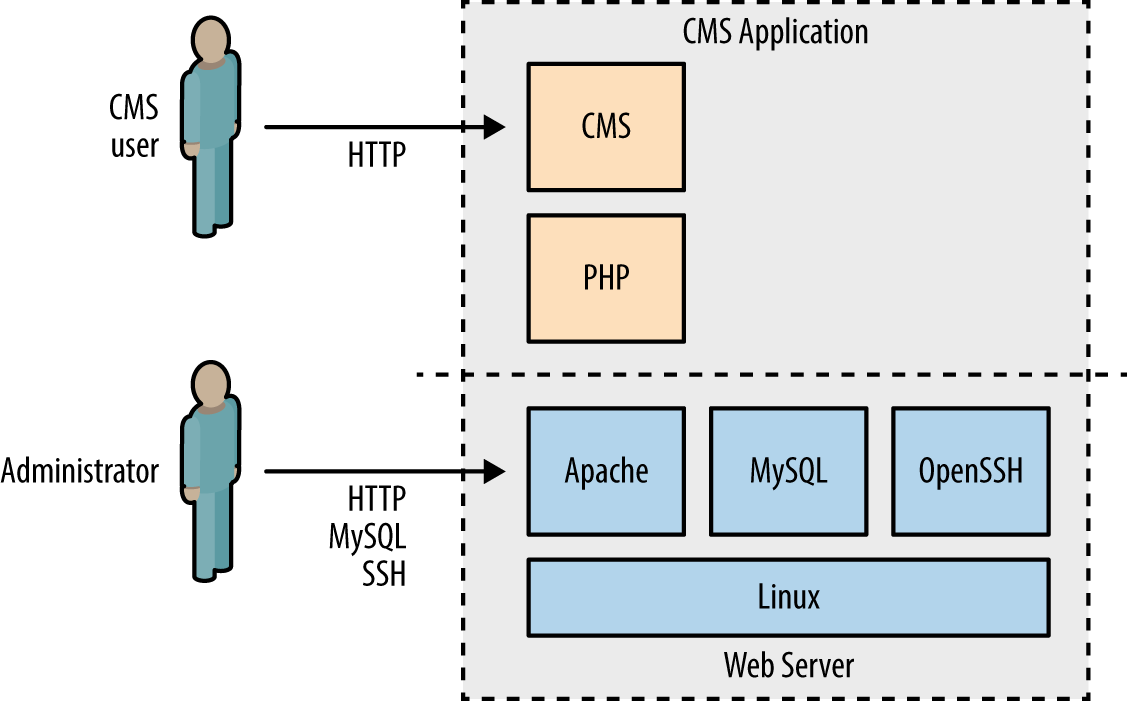

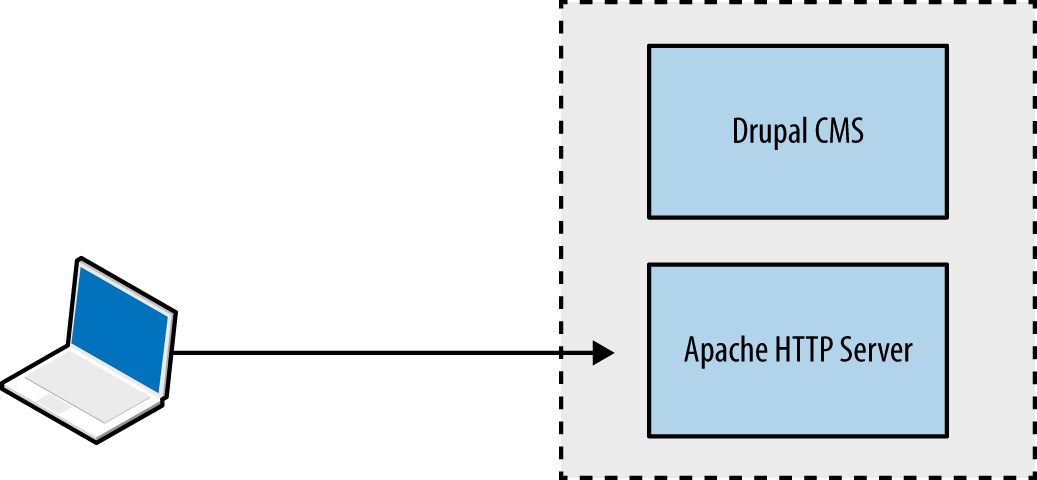

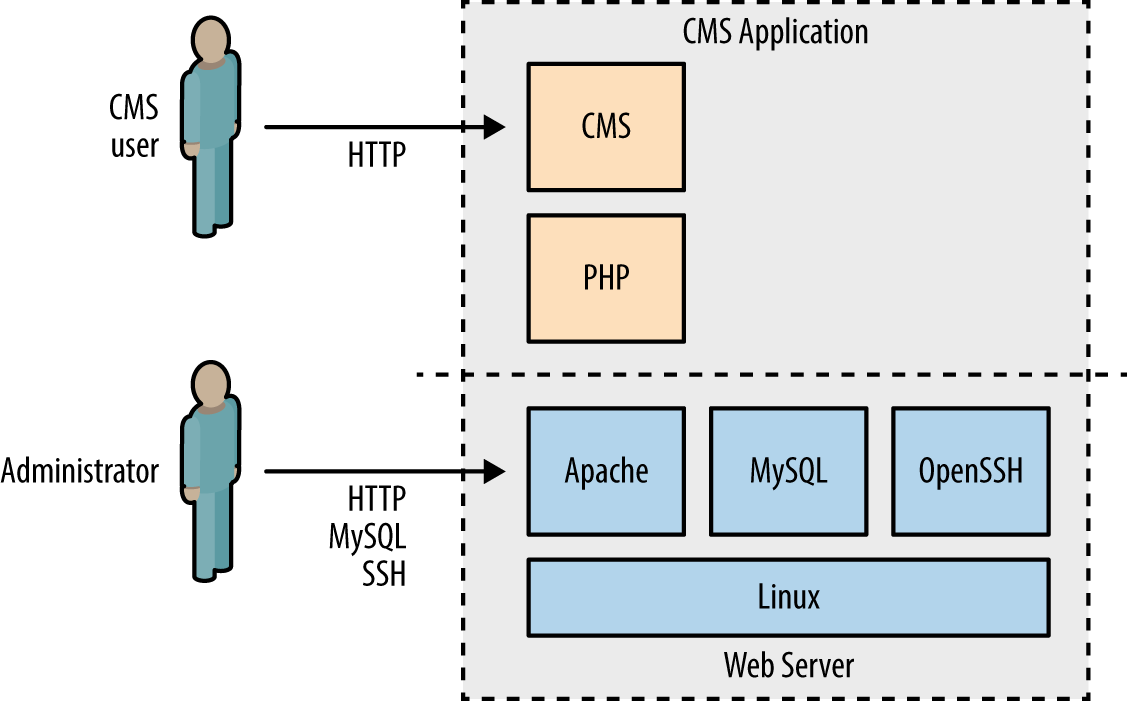

Figure 3-2 depicts a cloud-based web application.

The practical means by which the environment could be compromised include the following:

Compromise of the hosting provider or cloud management console1

Vulnerability within infrastructure (e.g., hypervisor side channel attack2)

Operating system vulnerability (e.g., network driver or kernel flaw)

Server software flaw (e.g., Nginx or OpenSSL bug)

Web application framework flaw (e.g., session management defect)

Web application bug (e.g., command injection or business logic flaw)

Attack of user HTTPS or SSH sessions

Compromise of legitimate credentials (e.g., SSH key or authentication token)

Desktop software attack (e.g., PuTTY SSH client or browser exploitation)

User attack through social engineering or clickjacking

Some attacks might be undertaken remotely, whereas others require proximity to manipulate vulnerable system components. For example, within multitenant cloud environments, gaining access to internal address space often exposes management interfaces that aren’t publicly accessible.

Figure 3-2 demonstrates individual software components forming a large attack surface. Locally within each piece of software, security errors might exist that can be exploited for gain. Gary McGraw, Katrina Tsipenyuk, and Brian Chess published a taxonomy3 used to categorize software defects, listing seven kingdoms:

An eighth kingdom is environment—used to classify vulnerabilities found outside of software source code (e.g., flaws within interpreter or compiler software, the web application framework, or underlying infrastructure).

Use the taxonomy to define the source of a defect that leads to unexpected behavior by an application. Note: these kingdoms do not define attack classes (such as side channel attacks).

Attackers target and exploit weakness within system components and features. The taxonomy lets us describe and categorize low-level flaws within each software package but does not tackle larger issues within the environment (such as the integrity of data in-transit, or how cryptographic keys are handled). To understand the practical risks to a system, you might model threats by considering the following:

Individual system components

Goals of the attacker

Exposed system components (the available attack surface)

Economic cost and feasibility of each attack vector

Exploitable vulnerabilities can exist within infrastructure (e.g., hypervisors, software switches, storage nodes, and load balancers), operating systems, server software, client applications, and end users themselves. Figure 3-3 shows the relationship between hardware, software, and wetware components within a typical environment.

Attackers pursue goals that might include the following:

Software written in languages with memory safety problems (e.g., C/C++) is susceptible to manipulation through buffer overflows, over-reads, and abuse of pointers, which can result in many of these goals being achieved. Writing applications in memory-safe languages (including Java and Microsoft .NET) can render entire bug classes redundant.

Three broad levels of system access that an adversary can secure are as follows:

Server applications are becoming increasingly decoupled, with message queuing, content delivery, storage, authentication, and other functions running over IP networks. Data in-transit is targeted for gain, by both local attackers performing network sniffing, and broad surveillance programs.6 Transport security between system components is increasingly important.

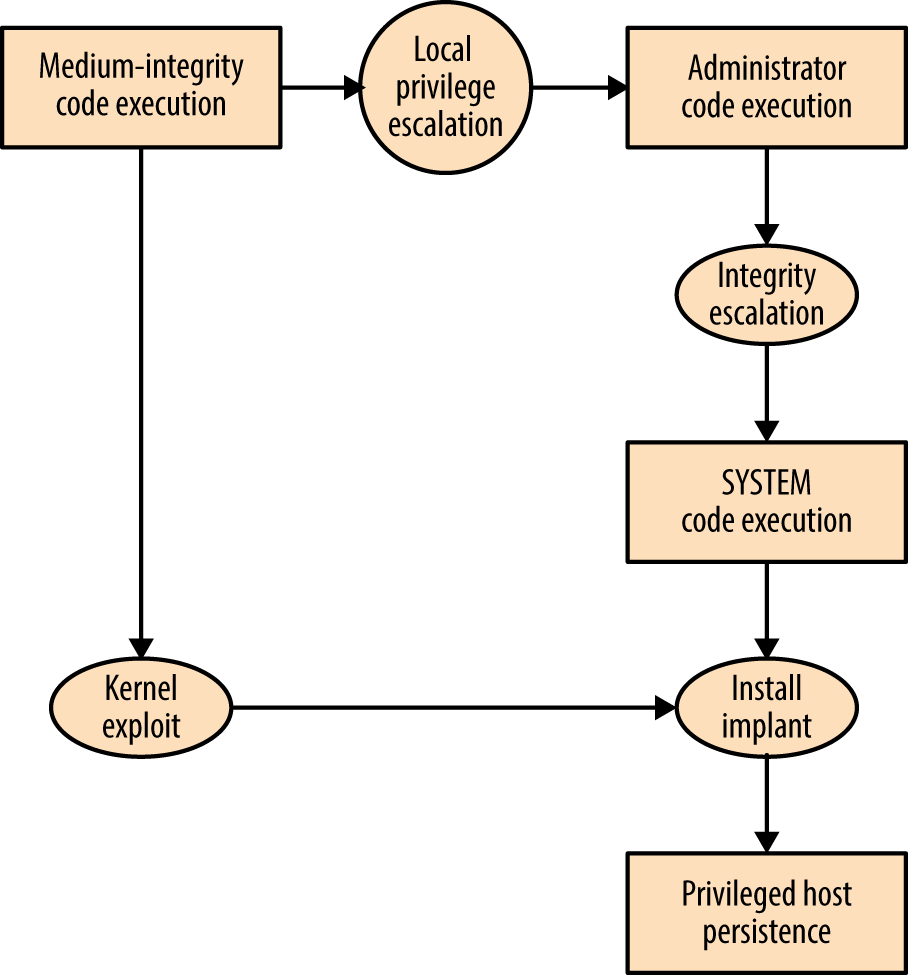

A common goal is code execution, by which exposed logic is used to execute particular instructions on behalf of the attacker. Execution often occurs within a narrow context, however. Consider three scenarios:

The context under which an adversary executes code varies. For example, web application flaws often result in execution via an interpreted language (e.g., JavaScript, Python, Ruby, or PHP) and rarely provide privileged access to the underlying operating system. Sandbox escape and local privilege escalation tactics must be adopted to achieve persistence.

The value of a compromised target to an adversary varies and can run into billions of dollars when dealing in intellectual property, trade secrets, or information that provides an unfair advantage within financial markets. If the value of the data within your systems is significantly greater than the cost to an adversary to obtain it, you are likely a target.

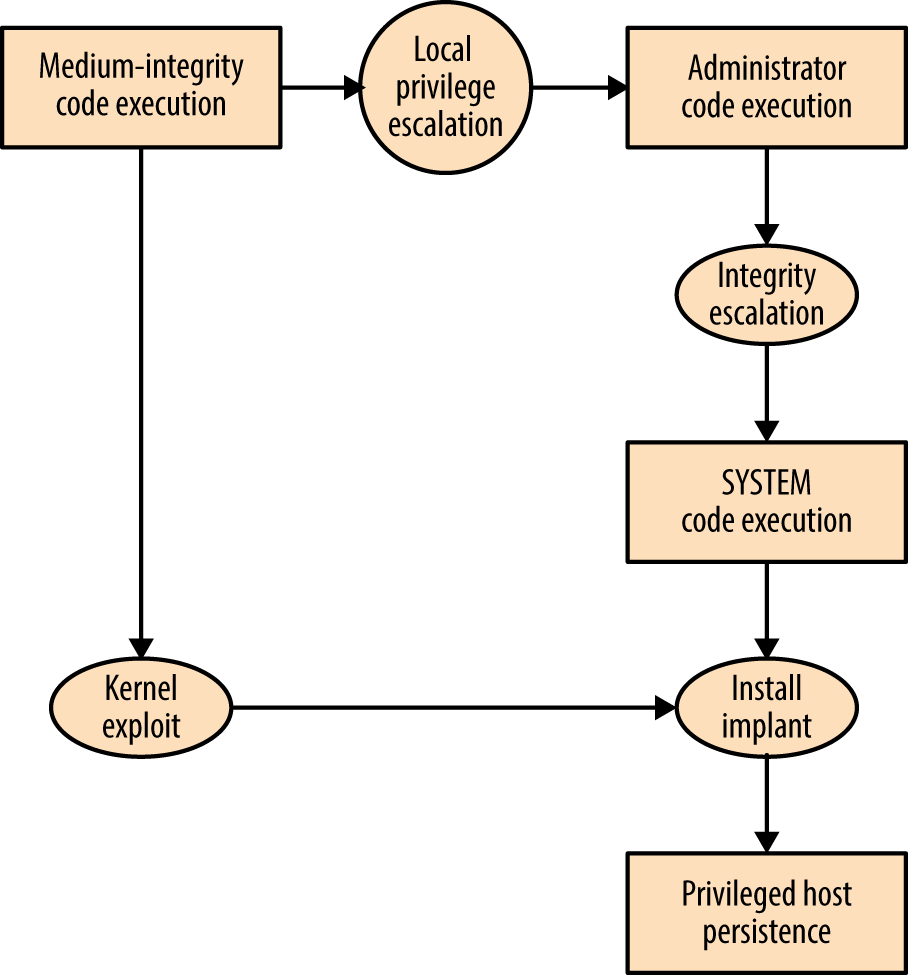

By combining adversarial goals with the exposed attack surface, we can plot attack graphs, as shown in Figures 3-4 and 3-5. In these examples, an adversary is presenting malicious content to Google Chrome with the goal of achieving native code execution and privileged host persistence.

Here are two important takeaways from the graphs:

Exploiting Java is the easiest route to medium-integrity native code execution

Kernel exploits provide the quickest route to privileged host persistence

Adversaries follow the path of least resistance and reuse code and infrastructure to reduce cost. The attack surface presented by desktop software packages (e.g., web browsers, mail clients, and word processors) combined with the low cost of exploit research, development, and malicious content delivery, makes them attractive targets that will likely be exploited for years to come.

Dino Dai Zovi’s presentation “Attacker Math 101” covers adversarial economics in detail, including other attack graphs, and discussing research tactics and costs.

Operating systems, server software packages, and desktop client applications (including browsers) are often written in C/C++. Through understanding runtime memory layout, how applications fail to safely process data, and values that can be read and overwritten, you can seek to understand and mitigate low-level software flaws.

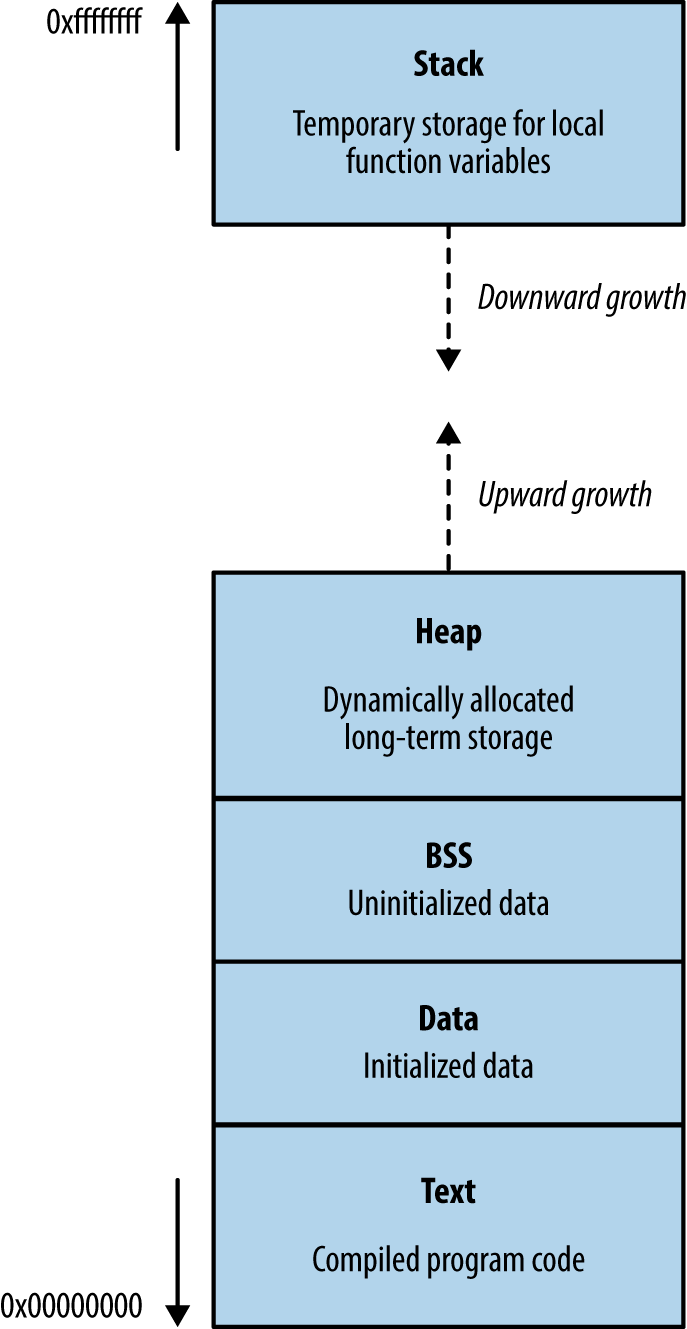

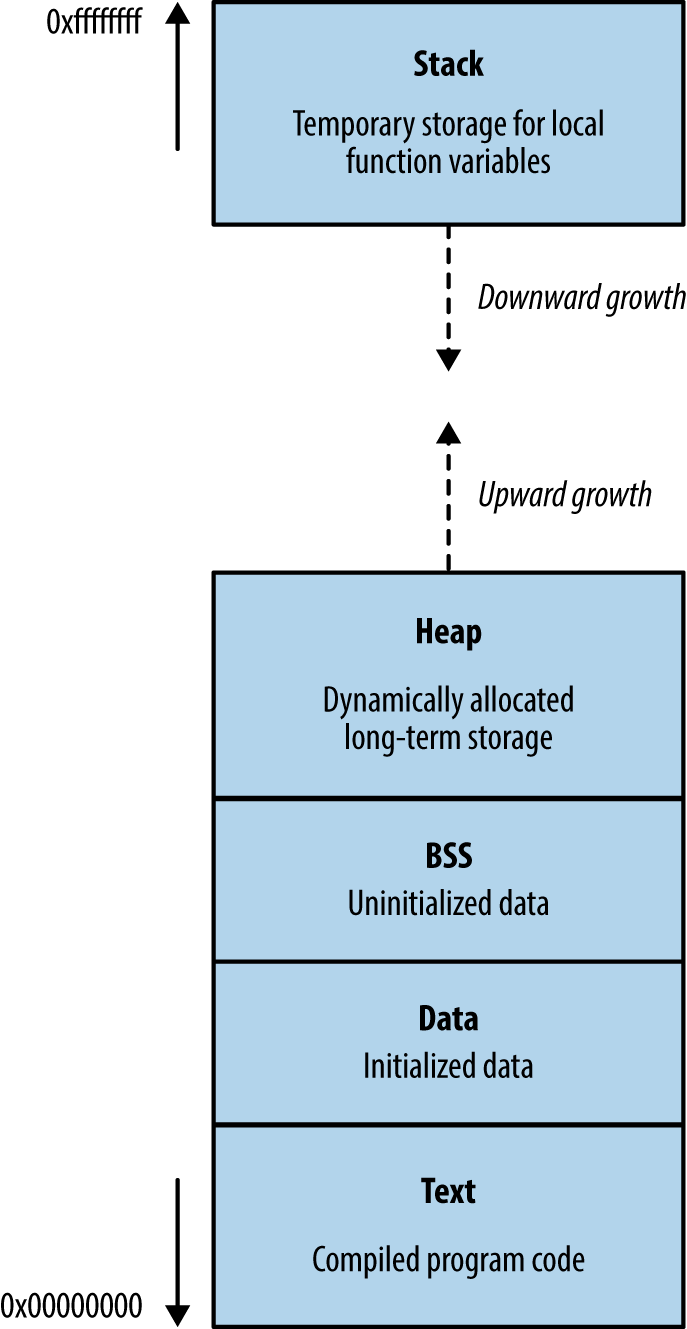

Memory layout within different operating systems and hardware platforms varies. Figure 3-6 demonstrates a high-level layout commonly found within Windows, Linux, and similar operating systems on Intel and AMD x86 hardware. Input supplied from external sources (users and other applications) is processed and stored using the stack and heap. If software fails to handle input safely, an attacker can overwrite sensitive values and change program flow.

This segment contains the compiled executable code for the program and its dependencies (e.g., shared libraries). Write permission is typically disabled for two reasons:

Code doesn’t contain variables and so has no reason to overwrite itself

Read-only code segments may be shared between concurrent program copies

In days gone by, code would modify itself to increase runtime speed. Most processors are optimized for read-only code, so modification incurs a performance penalty. You can safely assume that if a program attempts to modify material within the text segment, it was unintentional.

The heap is often the largest segment of memory assigned by a program. Applications use the heap to store persistent data that exists after a function returns (and its local variables are no longer accessible). Allocator and de-allocator functions manage data on the heap. Within C, malloc is often used to allocate a chunk of memory, and free is called to de-allocate, although other functions might be used to optimize allocation.

Operating systems manage heap memory by using different algorithms. Table 3-1 shows the implementations used across a number of platforms.

| Implementation | Operating system(s) |

|---|---|

| GNU libc (Doug Lea) | Linux |

| AT&T System V | Solaris, IRIX |

| BSD (Poul-Henning Kamp) | FreeBSD, OpenBSD, Apple OS X |

| BSD (Chris Kingsley) | 4.4BSD, Ultrix, some AIX |

| Yorktown | AIX |

| RtlHeap | Windows |

Most applications use inbuilt operating system algorithms; however, some enterprise server packages, such as Oracle Database, use their own to improve performance. Understanding the heap algorithm in use is important, as the way by which management structures are used can differ (resulting in exposure under certain conditions).

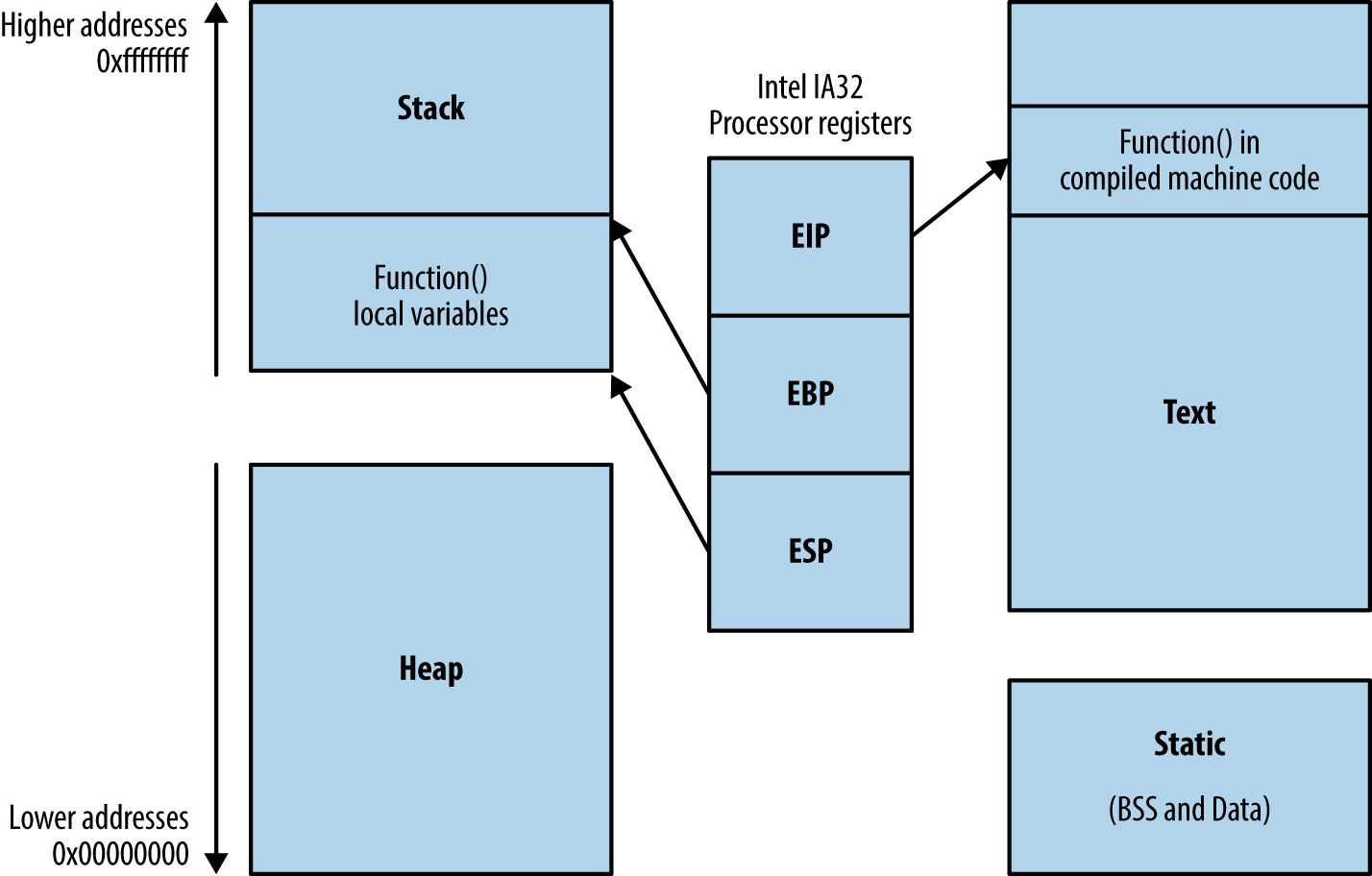

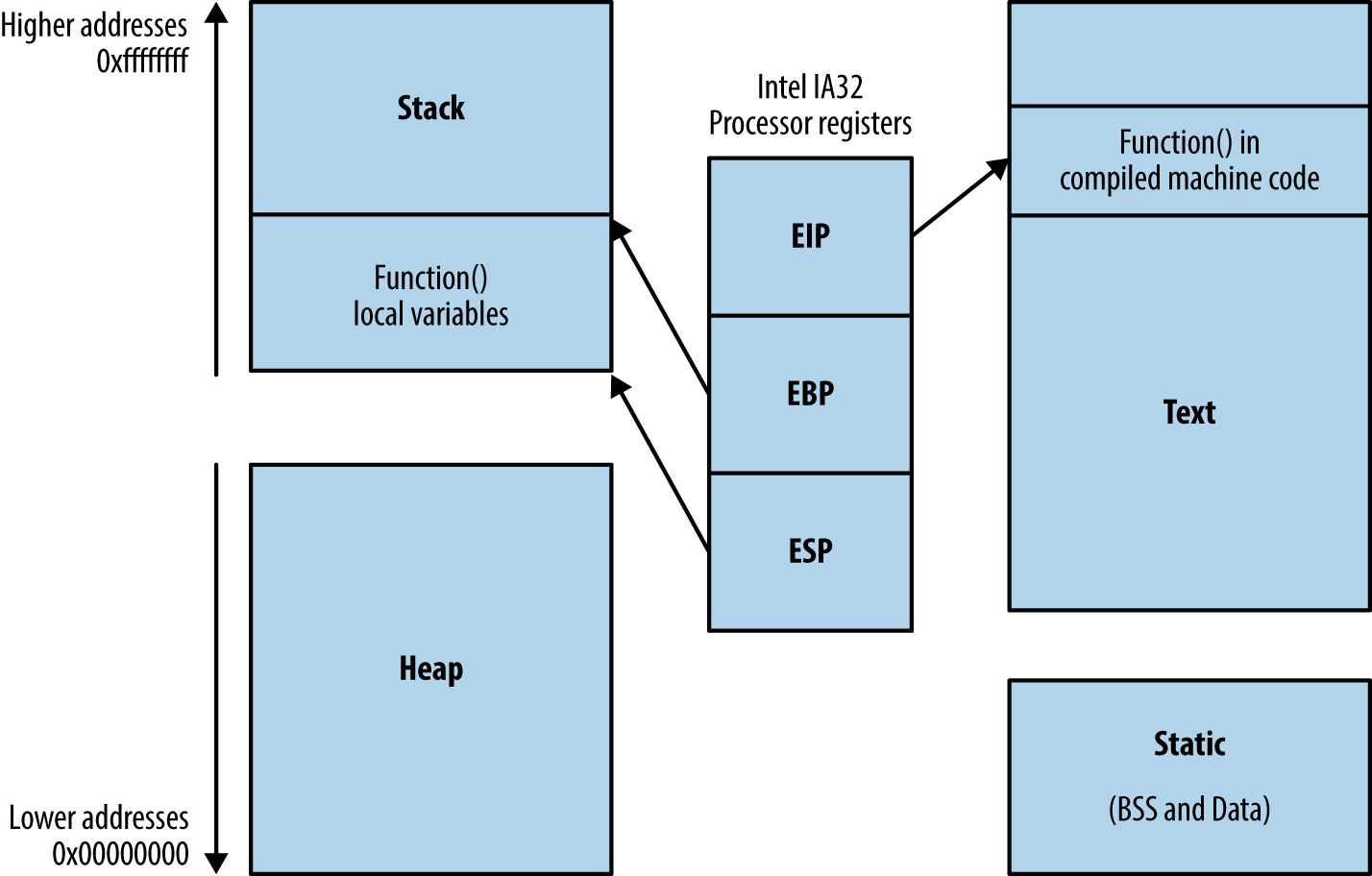

The stack is a region of memory used to store local function variables (such as a character buffer used to store user input) and data used to maintain program flow. A stack frame is established when a program enters a new function. Although the exact layout of the frame and the processor registers used varies by implementation (known as calling convention), a common layout used by both Microsoft and GCC on Intel IA-32 hardware is as follows:

The function’s arguments

Stored program execution variables (the saved instruction and frame pointers)

Space for manipulation of local function variables

As the size of the stack is adjusted to create this space, the processor stack pointer (esp) register is modified to point to the end of the stack. The stack frame pointer (ebp) points to the start of the frame. When a function is entered, the locations of the parent function’s stack and frame pointers are saved on the stack, and restored upon exit.

The stack is a last-in, first-out (LIFO) data structure: data pushed onto the stack by the processor exists at the bottom, and cannot be popped until all of the data above it has been popped.

Volatile memory contains code in the text segment, global and static variables in the data and BSS segments, data on the heap, and local function variables and arguments on the stack.

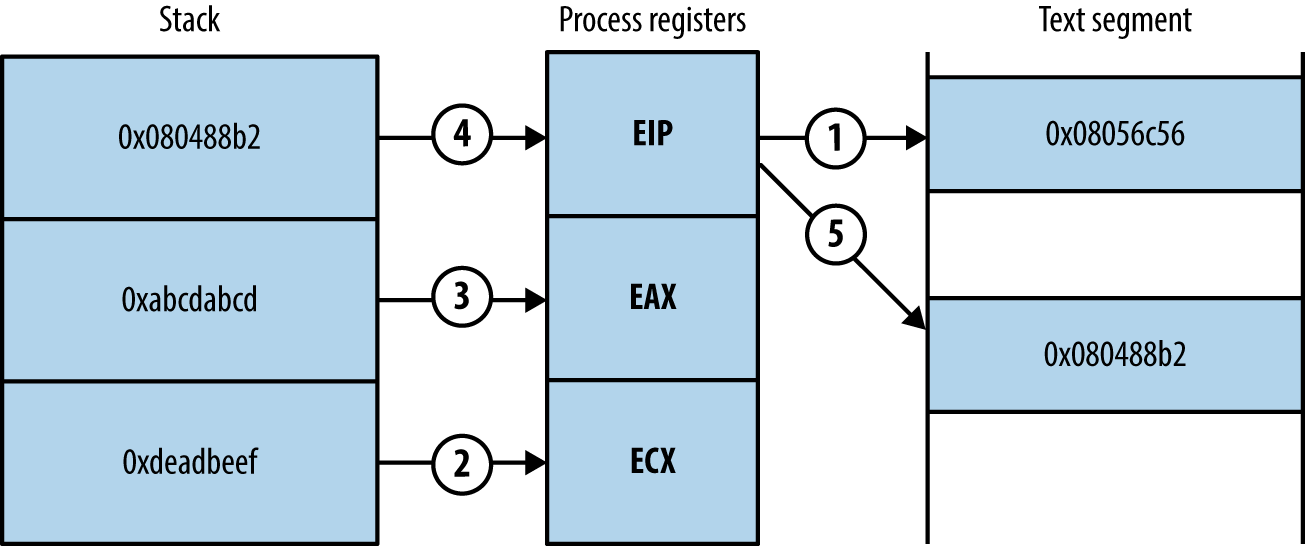

During program execution, the processor reads and interprets data by using registers that point to structures in memory. Register names, numbers, and sizes vary under different processor architectures. For simplicity’s sake, I use Intel IA-32 register names (eip, ebp, and esp in particular) here. Figure 3-7 shows a high-level representation of a program executing in memory, including these processor registers and the various memory segments.

Three important registers from a security perspective are the instruction pointer (eip) and the aforementioned ebp and esp. These are used to read data from memory during code execution, as follows:

eip points to the next instruction to be executed by the CPU

ebp should always point to the start of the current function’s stack frame

esp should always point to the bottom of the stack

In Figure 3-7, instructions are read and executed from the text segment, and local variables used by the function are stored on the stack. The heap, data, and BSS segments are used for long-term storage of data, because, when a function returns, the stack is unwound and local variables often overwritten by the parent function’s stack frame.

During operation, most low-level processor operations (e.g., push, pop, ret, and xchg) automatically modify CPU registers so that the stack layout is valid, and the processor fetches and executes the next instruction.

Overflowing an allocated buffer often results in a program crash because critical values used by the processor (e.g., the saved frame and instruction pointers on the stack, or control structures on the heap) are clobbered. Adversaries can take advantage of this behavior to change logical program flow.

Depending on exactly which area of memory (e.g., stack, heap, or data segments) input ends up in—and overflows out of—an adversary can influence logical program flow. What follows is a list of structures that an attacker can target for gain:

Systems increasingly rely on secrets stored in memory to operate in a secure manner (e.g., encryption keys, access tokens, authentication flags, and GUID values). Upon obtaining sensitive values through an information leak or side channel attack, an adversary can undermine the integrity of a system.

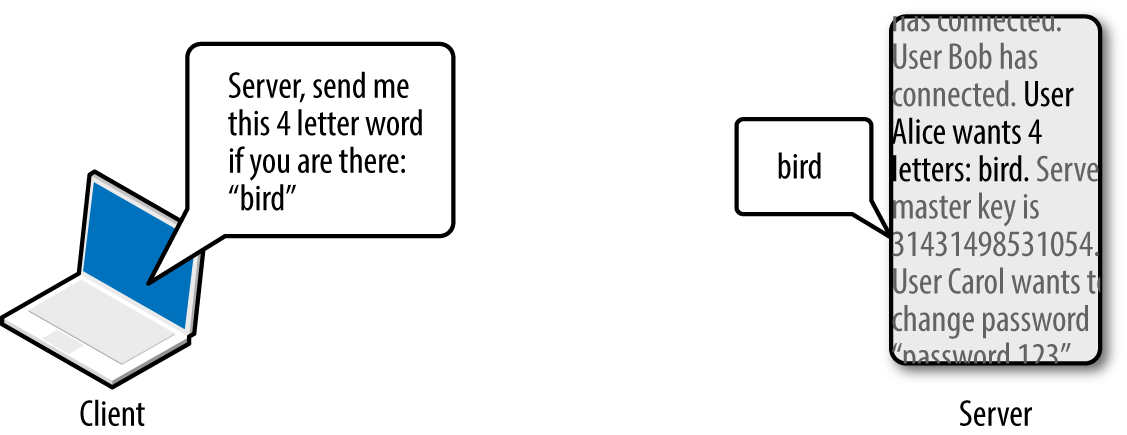

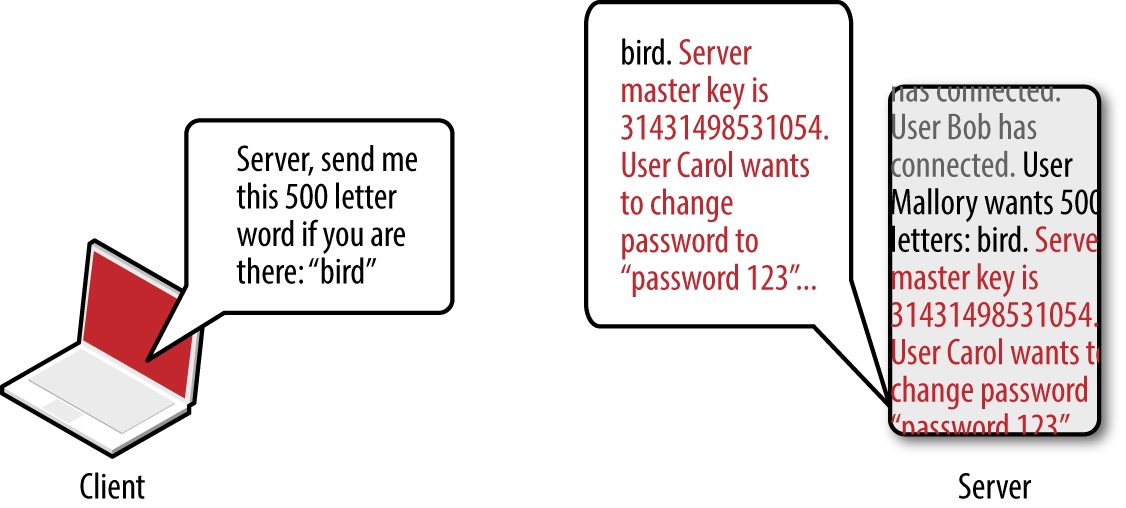

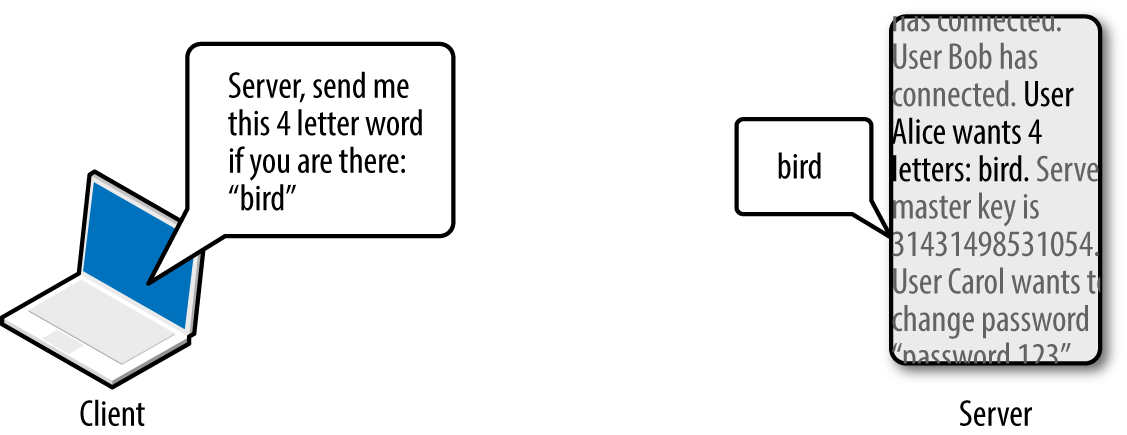

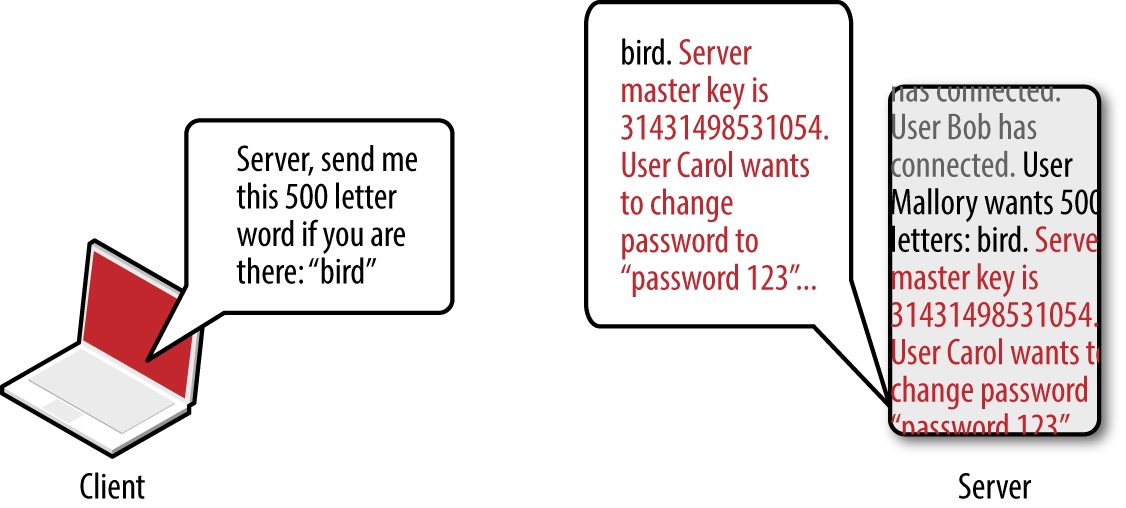

OpenSSL versions 1.0.1 through 1.0.1f are susceptible to a flaw known as heartbleed,10 as introduced into the OpenSSL codebase in March 2012 and discovered in early 2014 by Neel Mehta of Google.11 Figure 3-8 demonstrates a normal TLS heartbeat request, and Figure 3-9 demonstrates the heap over-read, revealing server memory upon sending a malformed TLS heartbeat request.12

The defect leaks up to 64K of heap content per request. By sending multiple requests, attackers can extract RSA private keys from a server application (such as Apache HTTP Server or Nginx) using a vulnerable OpenSSL library. Attackers can use Metasploit13 to dump the contents of the heap and extract private keys.

Secrets stored in volatile memory that might be exposed include the following:

As systems become increasingly distributed, protection of secrets (e.g., API keys and database connection strings) becomes a high priority. Severe compromises resulting in PII data exposure in recent years have stemmed from credentials leaked in this manner.

To provide resilience from attacks resulting in sensitive data being overwritten, or read from vulnerable applications, vendors implement security features within their operating systems and compilers. A paper titled “SoK: Eternal War in Memory” details mitigation strategies and attack tactics applying to languages with memory safety issues (e.g., C/C++). What follows is a list of common security features, their purpose, and details of the platforms that use them:

%s and %x) and other content is passed to functions including printf, scanf, and syslog, resulting in an attacker writing to or reading from arbitrary memory locations.You can modify an application’s execution path through overwriting certain values in memory. Depending on the security mechanisms in use (including DEP, ASLR, stack canaries, and heap protection), you might need to adopt particular tactics to achieve arbitrary code execution, as described in the following sections.

DEP prevents the execution of arbitrary instructions from writable areas of memory. As such, you must identify and borrow useful instructions from the executable text segment to achieve your goals. The challenge is one of identifying sequences of useful instructions that can be used to form return-oriented programming (ROP) chains; the following subsections take a closer look at these.

Processor opcodes vary by architecture (e.g., Intel and AMD x86-64, ARMv7, SPARC V8, and so on). Table 3-2 lists useful Intel IA-32 opcodes, corresponding instruction mnemonics, and notes. General registers (eax, ebx, ecx, and edx) are used to store 32-bit (4-byte word) values that are manipulated and used during different operations.

| Opcode | Assembly | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| \x58 | pop eax |

Remove the last word and write to eax |

| \x59 | pop ecx |

Remove the last word and write to ecx |

| \x5c | pop esp |

Remove the last word and write to esp |

| \x83\xec\x10 | sub esp, 10h |

Subtract 10 (hex) from the value stored in esp |

| \x89\x01 | mov (ecx), eax |

Write eax to the memory location that ecx points to |

| \x8b\x01 | mov eax, (ecx) |

Write the memory location that ecx points to to eax |

| \x8b\xc1 | mov eax, ecx |

Copy the value of ecx to eax |

| \x8b\xec | mov ebp, esp |

Copy the value of esp to ebp |

| \x94 | xchg eax, esp |

Exchange eax and esp values (stack pivot) |

| \xc3 | ret |

Return and set eip to the current word on the stack |

| \xff\xe0 | jmp eax |

Jump (set eip) to the value of eax |

Many of these operations update the esp (stack pointer) register so that it points to the bottom of the stack. For example, push decrements the pointer by 4 when a word is written to the stack, and pop increments it by 4 when one is removed.

The ret instruction is important within ROP—it is used to transfer control to the next instruction sequence, as defined by a return address located on the stack. As such, each sequence must end with a \xc3 value or similar instruction that transfers execution.

Program binaries and loaded libraries often contain millions of valid CPU instructions. By searching the data for particular sequences (e.g., useful instructions followed by \xc3), you can build simple programs out of borrowed code. Two tools that scan libraries and binaries for instruction sequences are ROPgadget17 and ROPEME18.

Upon scanning the text segment for instructions, you might find the following two sequences (the first value is the location in memory at which each sequence is found, followed by the hex opcodes, and respective instruction mnemonics):

0x08056c56: "\x59\x58\xc3 <==> pop ecx ; pop eax ; ret" 0x080488b2: "\x89\x01\xc3 <==> mov (ecx), eax ; ret"

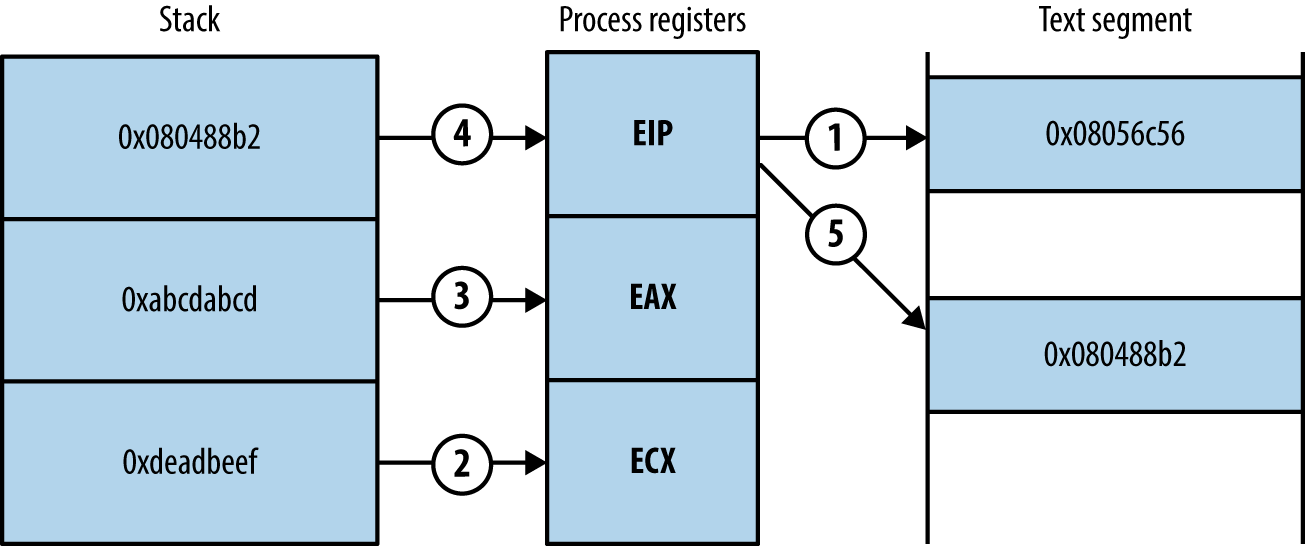

Both sequences are only three bytes long. Before you chain them together for execution, you first populate the stack, as shown in Figure 3-10.

Upon executing the first sequence from 0x08056c56, the following occurs:

The two words at the bottom of the stack are removed and stored within the ecx and eax registers. Each pop instruction also increments esp by 4 each time so that it points to the bottom of the stack.

The return instruction (ret) at the end of the first sequence reads the next word on the stack, which points to the second chain at 0x080488b2.

The second sequence writes the eax value to the memory address to which ecx points.

Useful sequences are chained to form gadgets. Common uses include:

Reading and writing arbitrary values to and from memory

Performing operations against values stored in registers (e.g., add, sub, and, xor)

Calling functions in shared libraries

When attacking platforms with DEP, ROP gadgets are often used as an initial payload to prepare a region of memory that is writable and executable. This is achieved through building fake stack frames for memory management functions (i.e., memset and mmap64 within Linux, and VirtualAlloc and VirtualProtect within Microsoft Windows) and then calling them. Through using borrowed instructions to establish an executable region, you inject and finally run arbitrary instructions (known as shellcode).

Dino Dai Zovi’s presentation19 details the preparation of ROP gadgets during exploitation of the Microsoft Internet Explorer 8 Aurora vulnerability,20 using a stack pivot to establish an attacker-controlled stack frame.

ASLR jumbles the locations of pages in memory. The result is that, upon exploiting a flaw (such as an overflow condition), you do not know the location of either useful instructions or data. Example 3-1 shows Ubuntu Linux randomizing the base address for each loaded library upon program execution.

Although these libraries are loaded at random locations, useful functions and instruction sequences exist at known offsets (because the page location is randomized, as opposed to the contents). The problem is then one of identifying the base address at which each library is loaded into memory.

ASLR is not enabled under the following scenarios:

The program binary is not compiled as a position-independent executable (PIE)

Shared libraries used by the program are not compiled with ASLR support

In these cases, you simply refer to absolute locations within binaries that opt out of ASLR. Certain DLLs within Microsoft Windows are compiled without ASLR—if a vulnerable program loads them, you can borrow instructions and build ROP gadgets.

Some platforms load data at fixed addresses, including function pointers. For example, during Pwn2Own 2013, VUPEN used the KiFastSystemCall and LdrHotPathRoutine function pointers to bypass ASLR on Windows 7.21 These two pointers exist at fixed addresses on unpatched systems, which you can use to execute arbitrary instructions.

If the program binary and loaded libraries use dynamic base addresses, you can pursue other means to calculate and obtain them, including the following:

Undertaking brute-force attacks to locate valid data and instructions

Revealing memory contents via information leak (e.g., a heap over-read)

Brute-force is achievable under certain conditions; dependent on the level of system access, along with the operation of the target application and underlying operating system. A 32-bit process is often easier to attack than a 64-bit one because the number of iterations to grind through is lower.

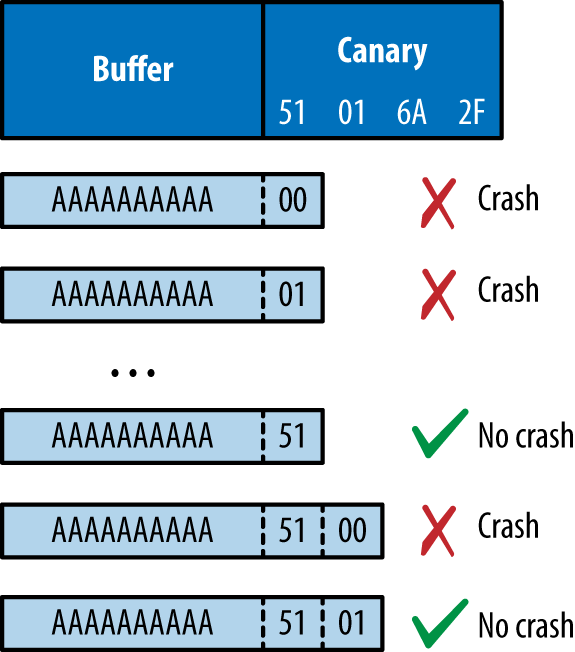

Depending on their implementation, an attacker can overcome stack canary mechanisms through the following methods:

Using an information leak bug to reveal the canary

Inferring the canary through iterative overflow attempts (if the canary is static)

Calculating the canary through a weakness in the implementation

Overwriting a function pointer and diverting logical program flow before the canary is checked (possible when exploiting Microsoft SEH pointers)

Overwriting the value the canary is checked against

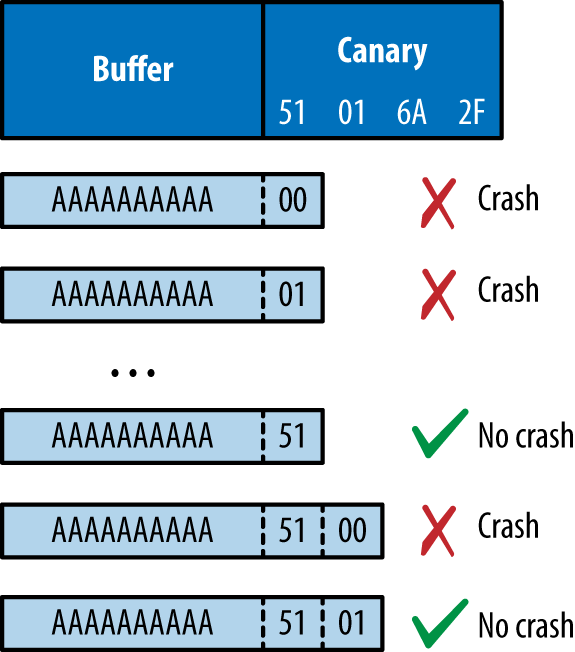

Inferring the canary as per the second bullet is an interesting topic—Andrea Bittau and others at Stanford University published a paper in 2014 titled “Hacking Blind”,22 in which they successfully remotely exploit Nginx via CVE-2013-2028. The target system ran a 64-bit version of Linux with stack canaries, DEP, and ASLR.

Bittau et al.’s attack works by identifying the point at which their material overwrites the canary (causing a crash), and then iteratively overwriting it byte-by-byte, until the service no longer crashes, meaning the canary is valid. The stack layout across subsequent overflow attempts is shown in Figure 3-11.

Writing past the canary modifies the saved frame and instruction pointers. By inferring these through writing byte-by-byte in the same fashion, you can begin to map memory layout (identifying the location of the text segment and the parent stack frame) and bypass ASLR.

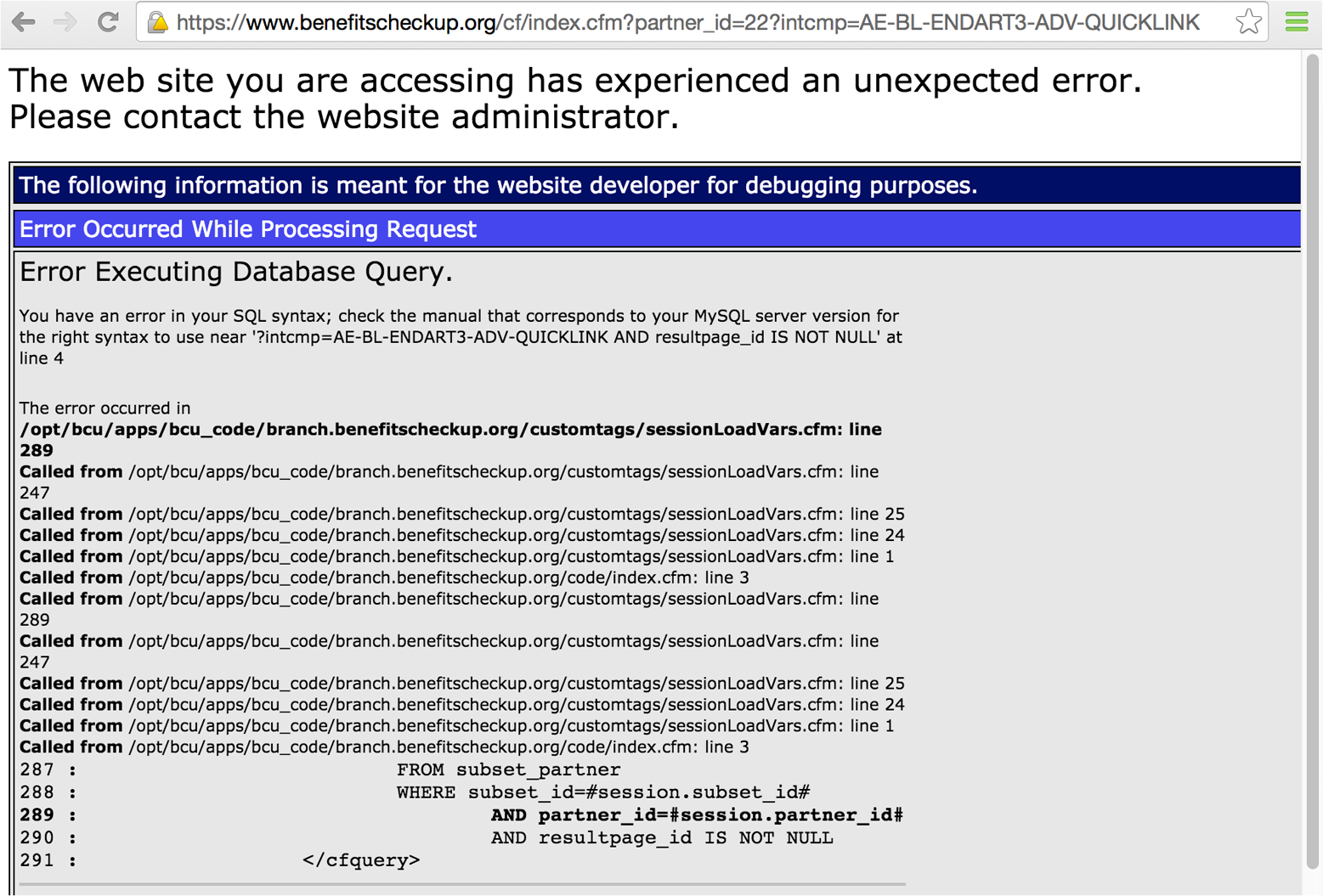

I’ve demonstrated how attackers abuse operating systems, server software, and desktop applications through memory manipulation. Many web and mobile applications are developed using memory-safe languages (including Java and Microsoft .NET), and so attackers must exploit logic flaws and other vulnerabilities to achieve certain goals. Common defects result in the following flaws being exploited:

Inference of usernames within account logon or password reset logic

Session management issues around generation and use of tokens (e.g., session fixation, whereby a session token is not regenerated after a user authenticates)

Encapsulation bugs, wherein requests are honored and materials processed without question (e.g., direct object reference, XXE flaws, or malicious JavaScript used within XSS attacks)

Information leak flaws, by which crafted requests reveal materials from the file system or backend data storage (such as a database or key-value store)

Throughout the book you will find that vulnerabilities range from subtle low-level memory management defects, through to easily exploitable logic flaws. It is critical to understand the breadth of potential issues, so that you can implement effective security controls through defense in depth.

As system components become increasingly decoupled and perimeters collapse, dependence on cryptography to enforce security boundaries (by generating random numbers, HMAC values, and providing confidentiality) increases.

Here are some common cryptographic functions found within computer systems:

Protocols providing transport layer security (such as TLS and IPsec)

Encryption of data at-rest

Signing of data to provide integrity checking (e.g., HMAC calculation)

Exploitable flaws can exist in any of these, through improper implementation or defects within the underlying protocol. A failure within one component can also allow an attacker to exploit another (e.g., insufficient integrity checking allowing content to be sent to an oracle, in turn revealing an encryption key).

If a PRNG generates predictable values, an adversary can take advantage of this behavior. In August 2013, the Android PRNG was found to be insecure,23 leading to mobile Bitcoin wallets becoming accessible to attackers.24

Exploitation of many weaknesses in cryptographic components often requires particular access, such as network access to intercept traffic, or local operating system access to obtain values used by a PRNG.

Key compromise can result in a catastrophic failure. In 2014, an attacker obtained the server seed values used by the Primedice gaming site, resulting in a loss of around $1 million in Bitcoin.25

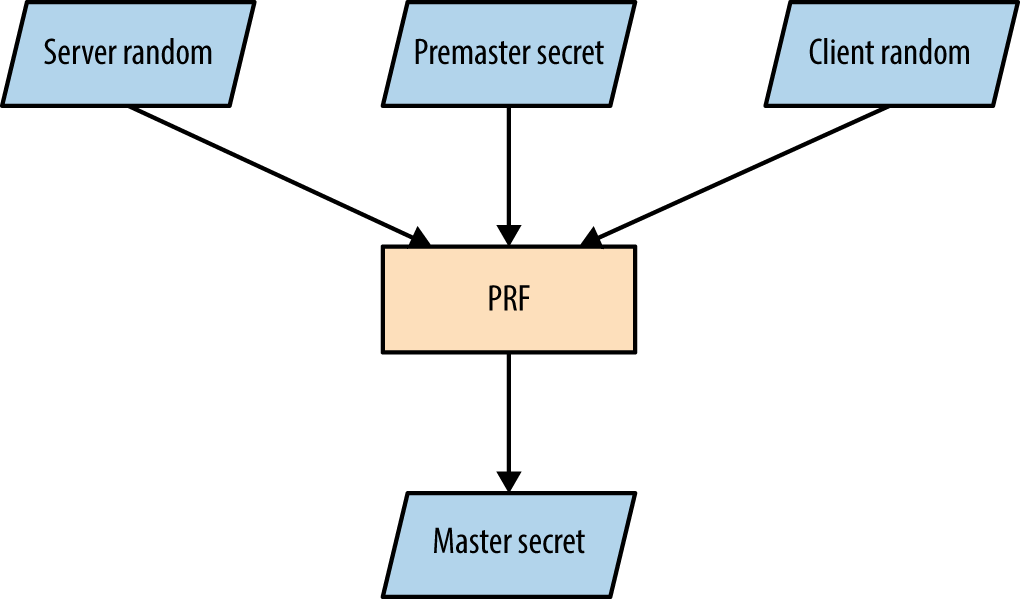

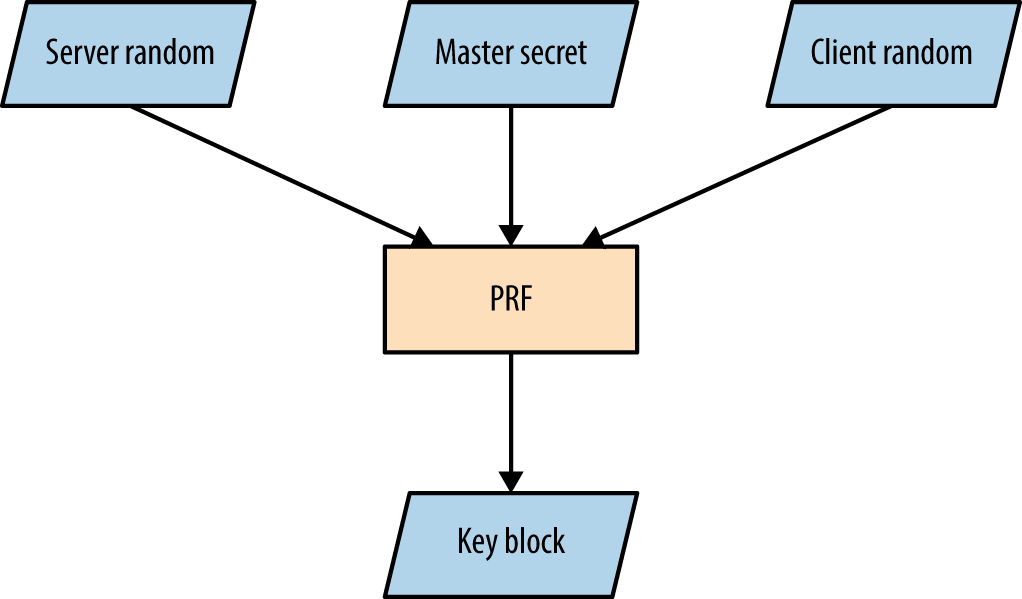

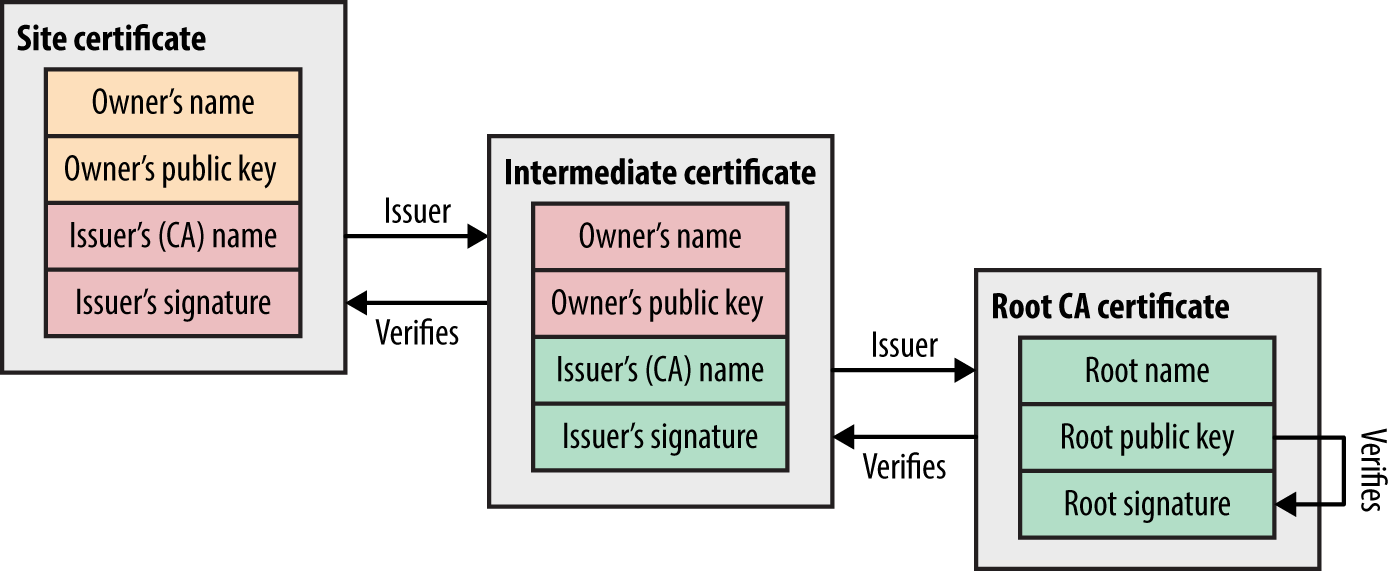

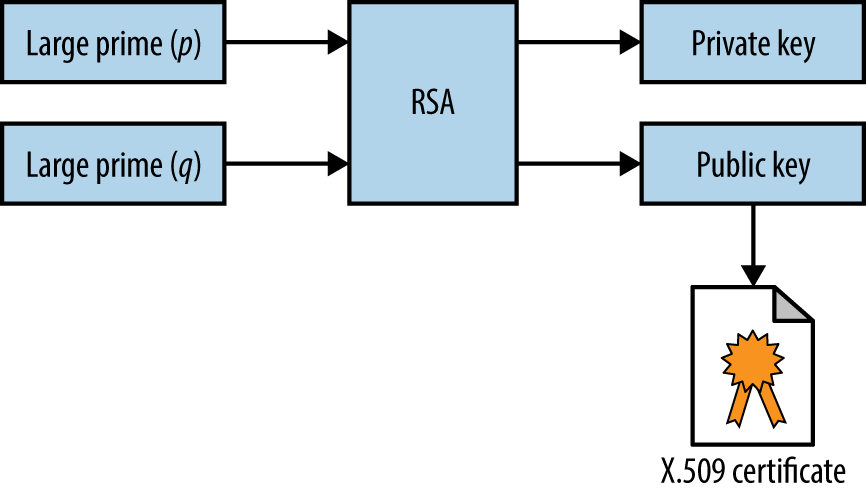

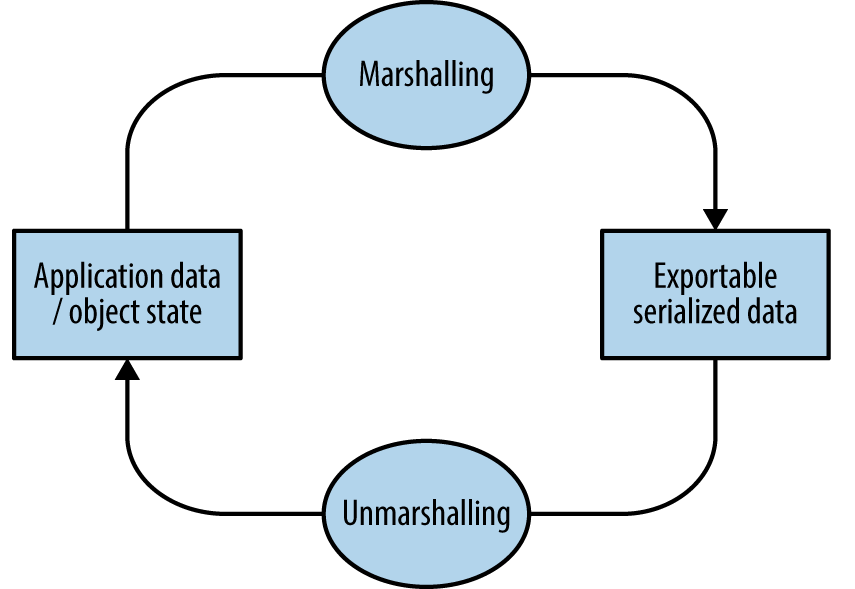

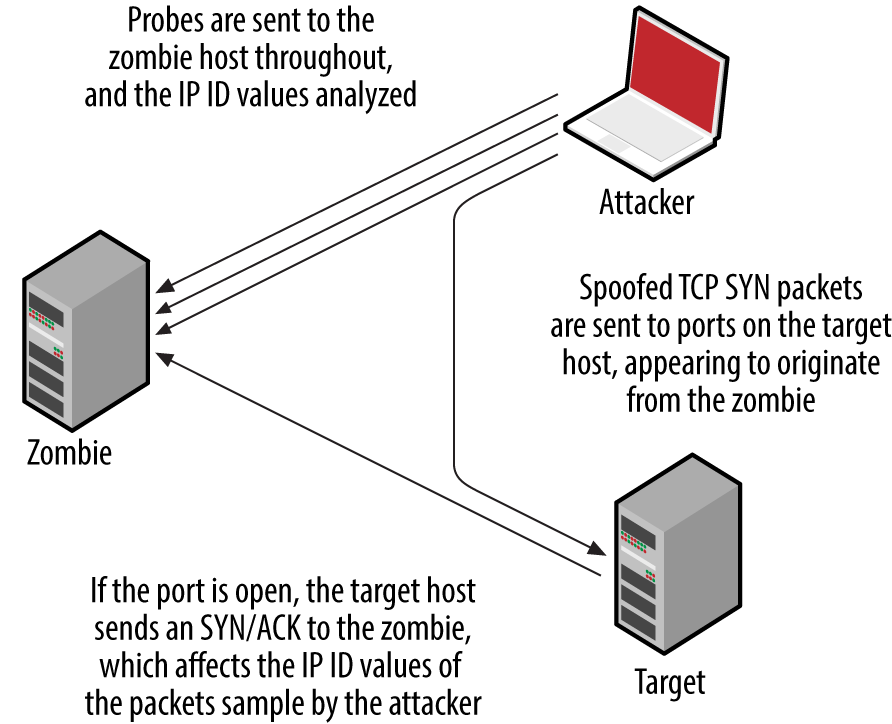

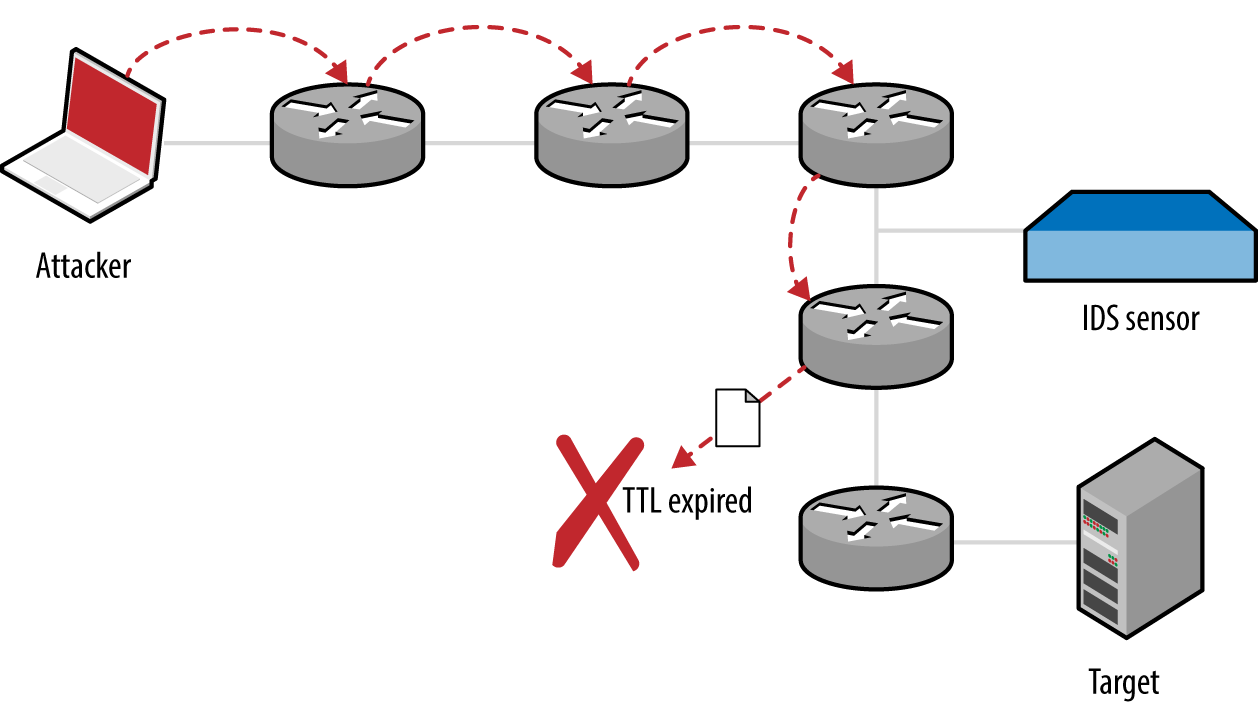

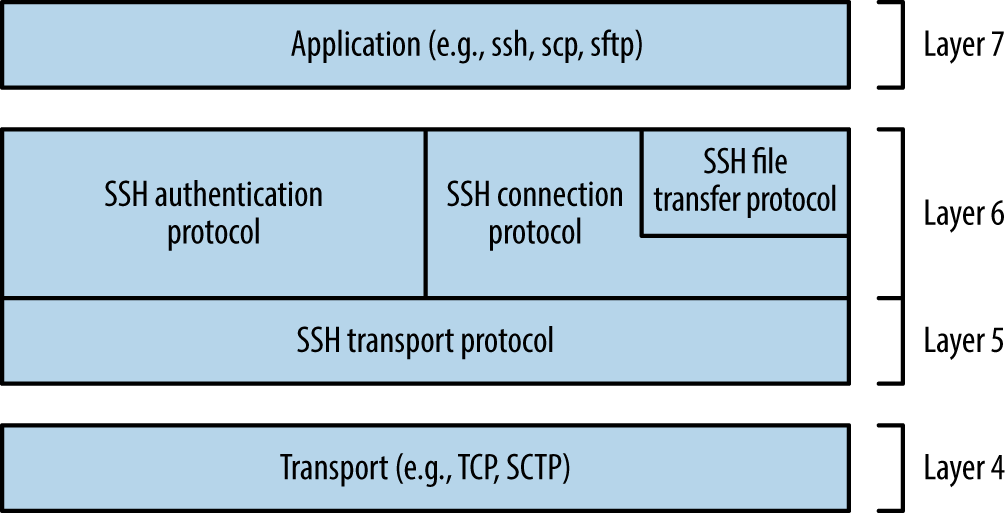

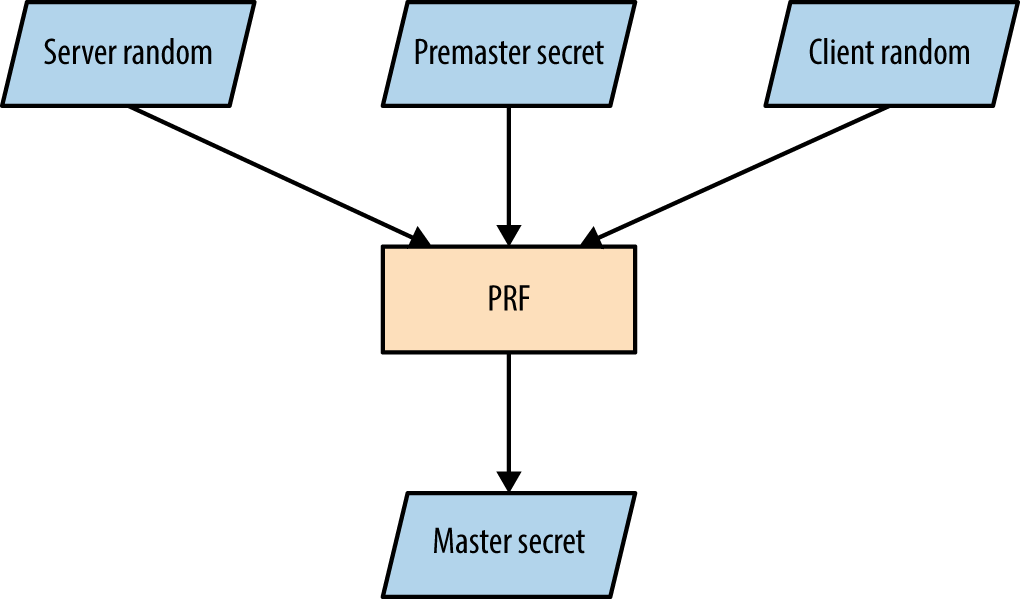

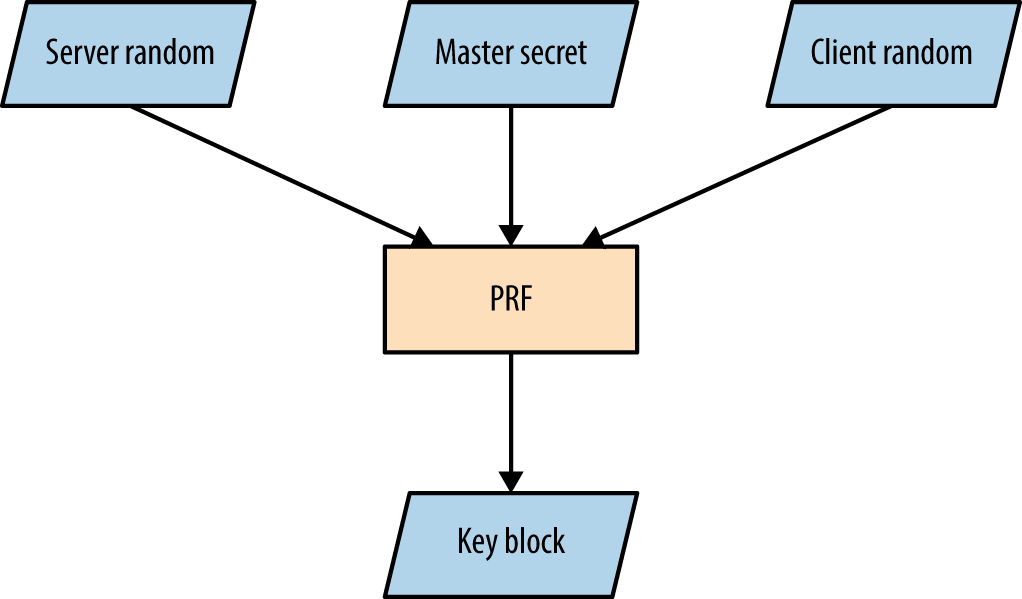

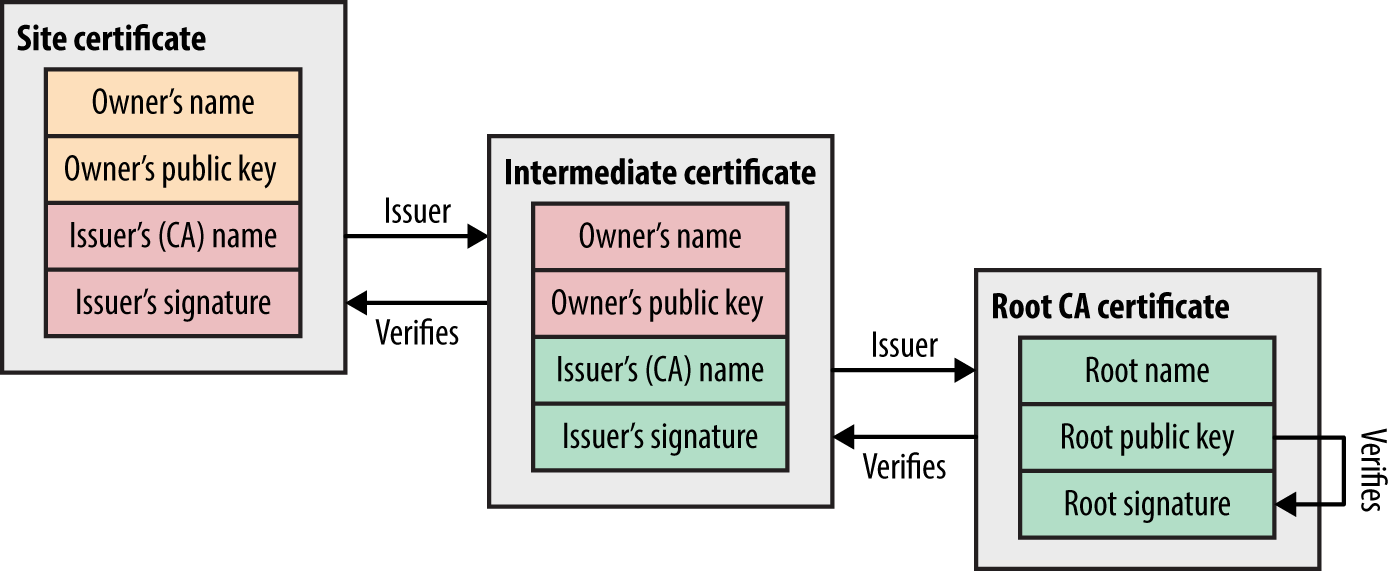

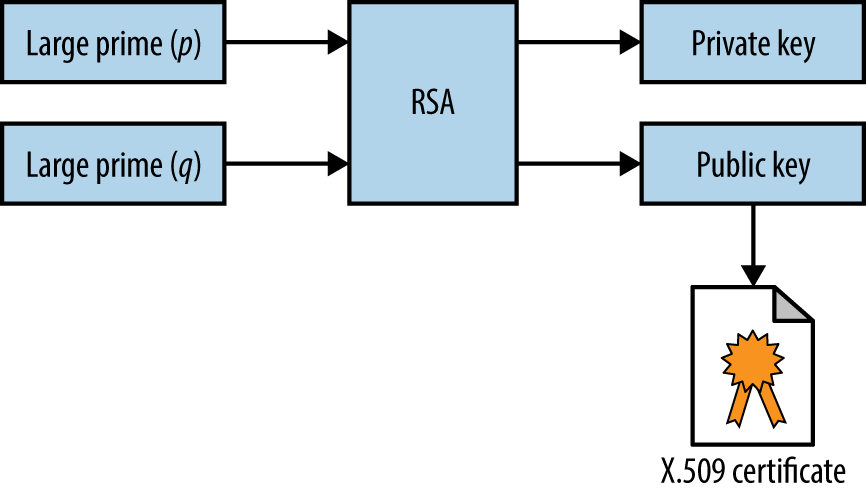

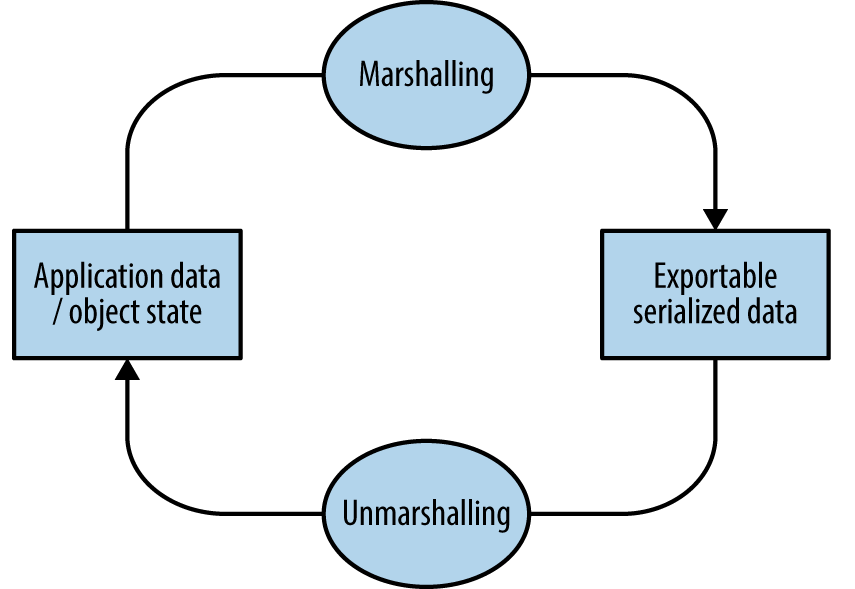

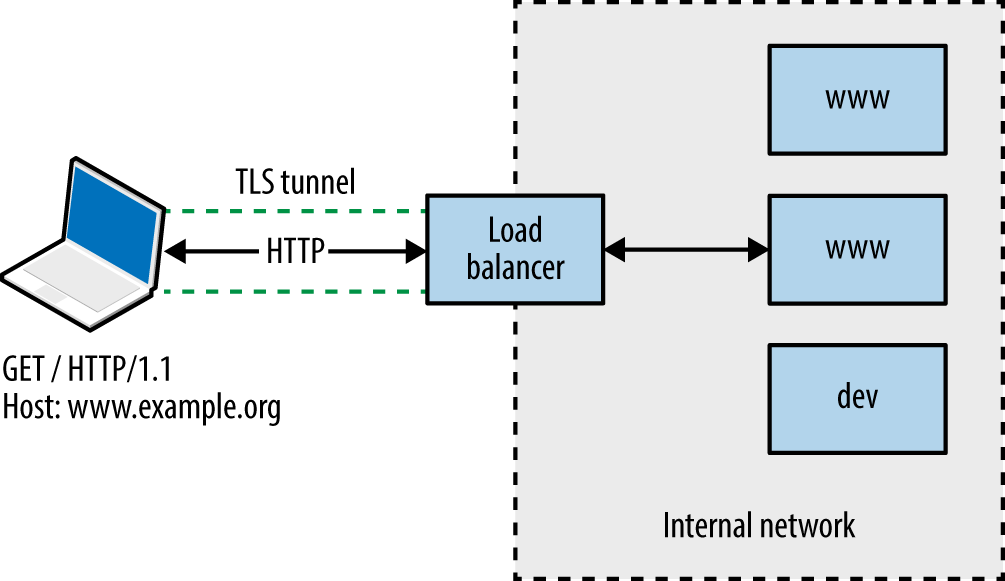

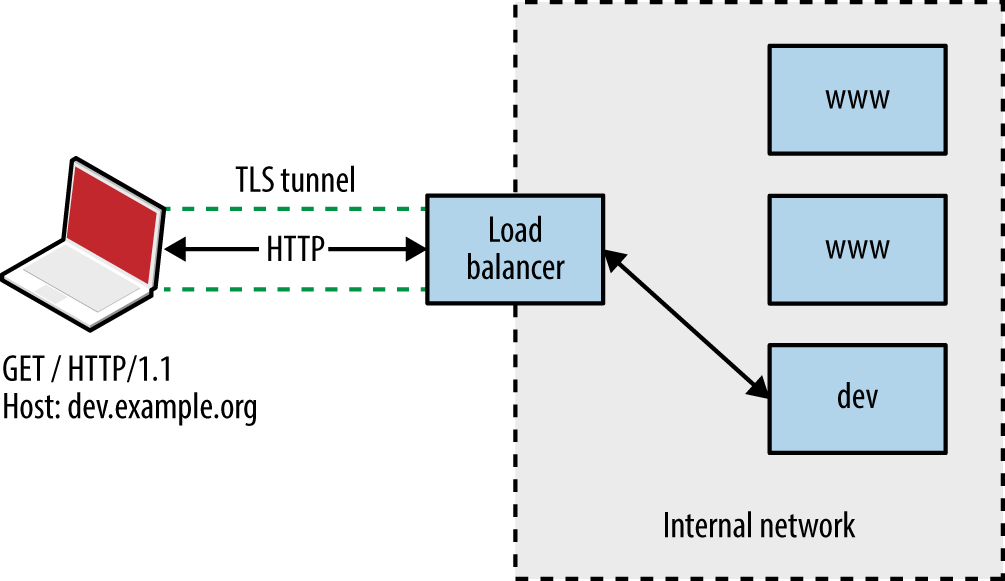

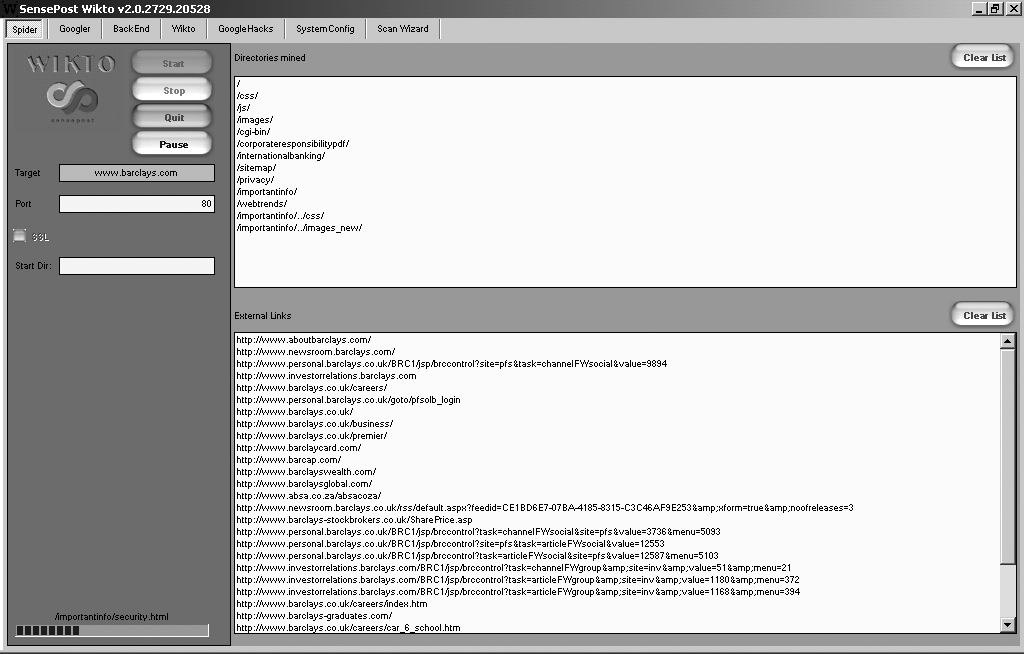

Popular classes of attack against cryptosystems include the following: