Chapter 9. Assessing Mail Services

Mail services relay messages across both the Internet and private networks. Adversaries often use the channels formed by mail protocols to target internal systems. This chapter details the tactics you can adopt to identify flaws in available mail services—including service identification, enumeration of enabled options, and testing for known weaknesses.

Mail Protocols

Table 9-1 lists mail services supporting mail delivery (via SMTP) and collection (via POP3 and IMAP). TLS is often used to provide transport security.

| Port | Protocol | TLS | Name | Description | Hydra | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCP | UDP | |||||

| 25 |

● |

– | – | smtp | Simple Mail Transfer Protocol |

● |

| 465 |

● |

– |

● |

smtps | ||

| 587 |

● |

– | – | submission | ||

| 110 |

● |

– | – | pop3 | Post Office Protocol |

● |

| 995 |

● |

– |

● |

pop3s | ||

| 143 |

● |

– | – | imap2 | Internet Message Access Protocol |

● |

| 993 |

● |

– |

● |

imaps | ||

SMTP

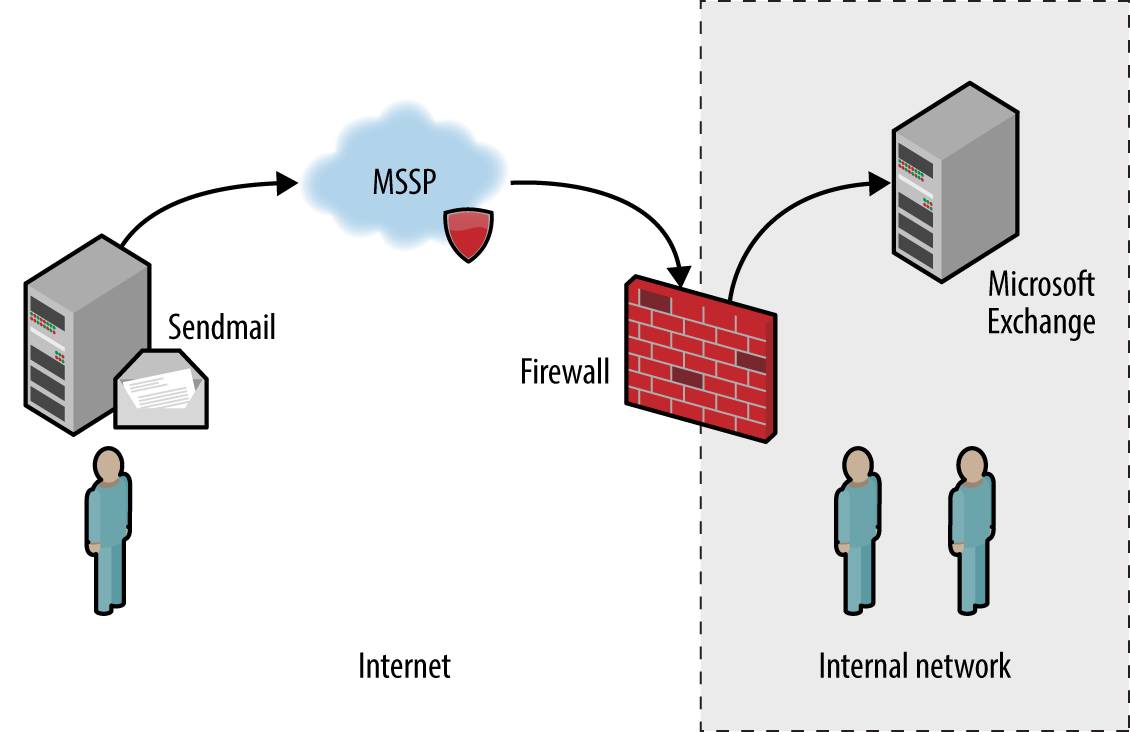

SMTP servers (known as message transfer agents or MTAs) transport email using software packages such as Sendmail and Microsoft Exchange. Figure 9-1 demonstrates a typical configuration, in which content filtering mechanisms are used to scrub email.

Figure 9-1. SMTP servers processing Internet-based mail

In this case, inbound mail is first sent to a managed security service provider (MSSP) to quarantine malware, spam, and other threats. The MSSP relays processed mail to the organization’s external SMTP interface (usually a firewall or appliance performing further filtering), which in turn is delivered to an internal mail server.

Configuration of devices and mail servers throughout the chain is important. Insufficient network filtering allow an attacker to establish a session with an organization’s external SMTP interface and bypass the MSSP, for example. Many servers also send nondelivery notification (NDN) messages if they are unable to relay email to the intended recipient, revealing software and network configuration details.

Note

Attacks launched via SMTP might have different goals and targets. For example, an adversary could take advantage of a flaw within an exposed service directly (e.g., exploit a known bug within Microsoft Exchange) or use SMTP as a delivery mechanism to serve malicious content to a vulnerable component within a larger system (e.g., an antivirus engine running an internal mail server).

Service Fingerprinting

Upon preparing a list of mail servers and valid domains, you can fingerprint each SMTP endpoint and identify enabled subsystems and features. Mail server software details are obtained through banner grabbing, behavioral analysis, and passive review of NDNs.

The SMTP banner presented upon connection often describes the implementation. If the banner is obfuscated or doesn’t provide sufficient detail, the HELP command might provide meaningful feedback. Example 9-1 demonstrates manual fingerprinting of an SMTP service, followed by scanning with Nmap.

Example 9-1. Fingerprinting an SMTP endpoint

root@kali:~# dig +short mx fb.com 10 mxa-00082601.gslb.pphosted.com. 10 mxb-00082601.gslb.pphosted.com. root@kali:~# telnet mxa-00082601.gslb.pphosted.com 25 Trying 67.231.145.42... Connected to mxa-00082601.gslb.pphosted.com. Escape character is '^]'. 220 mx0a-00082601.pphosted.com ESMTP mfa-m0004346 HELP 500 5.5.1 Command unrecognized: "HELP" QUIT 221 2.0.0 mx0a-00082601.pphosted.com Closing connection Connection closed by foreign host. root@kali:~# nmap -sV -p25 mxa-00082601.gslb.pphosted.com Starting Nmap 6.46 (http://nmap.org) at 2014-09-09 22:15 UTC Nmap scan report for mxa-00082601.gslb.pphosted.com (67.231.153.30) Host is up (0.092s latency). PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION 25/tcp open smtp Symantec Enterprise Security manager smtpd Service Info: Host: mx0b-00082601.pphosted.com

Mapping SMTP Architecture

Mail servers often send verbose NDN messages back to the source if they are unable to route mail to a recipient. This gives adversaries an opportunity to infer valid mailboxes (which are later used during phishing campaigns). A secondary benefit is that NDN messages contain useful environmental details, including:

-

Hostnames and IP addresses

-

Mail server software version and configuration

-

The underlying OS and server configuration

-

Physical location of mail servers (based on time zone and format)

-

TLS configuration and support between servers

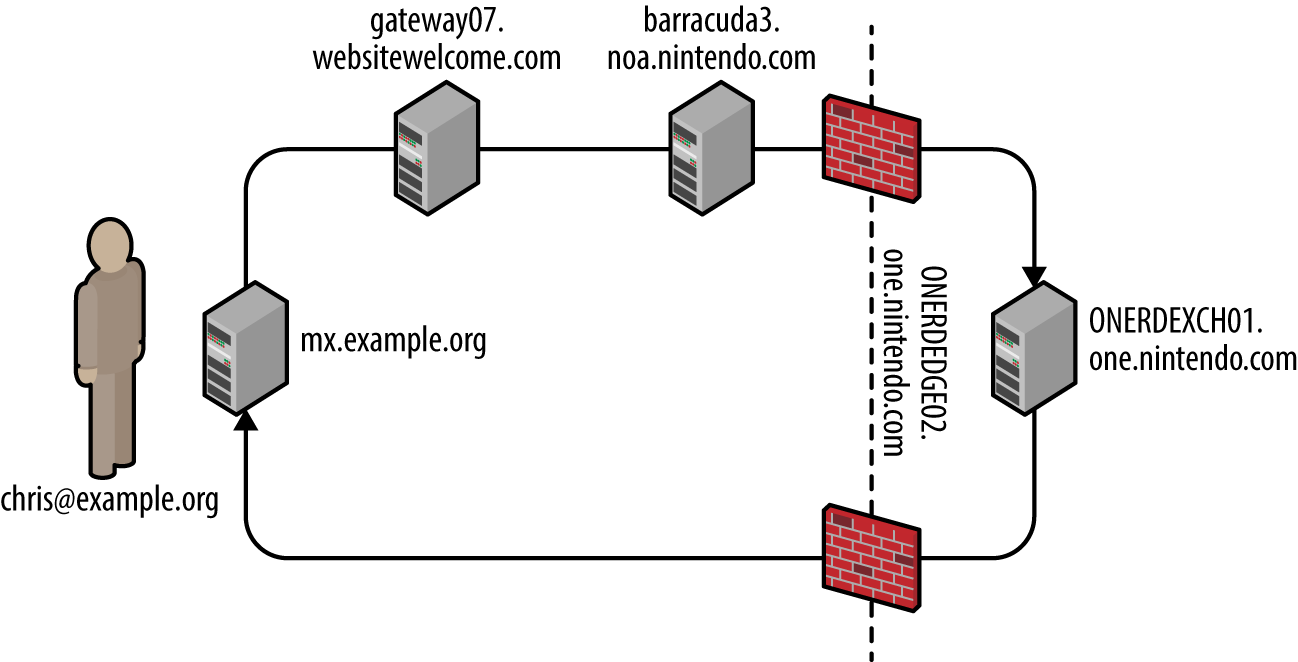

RFC 5321 mandates that SMTP headers must not be altered by mail server software. Upon viewing the source of a message, we find that each mail server adds a Received header, as summarized by Example 9-2. In this case, I extract the headers from an NDN message for blah@nintendo.com.

Example 9-2. SMTP Received headers reveal useful details

Received: from smtpout.nintendo.com ([205.166.76.16]:17869 helo=ONERDEDGE02.one.nintendo.com) by mx.example.org with esmtps (TLSv1:AES128-SHA:128) (Exim 4.82) id 1XXqMW-00042s-QQ for chris@example.org; Sat, 27 Sep 2014 06:40:29 -0500 Received: from ONERDEXCH01.one.nintendo.com (10.13.30.31) by ONERDEDGE02.one.nintendo.com (10.13.20.35) with Microsoft SMTP Server (TLS) id 14.3.174.1; Sat, 27 Sep 2014 04:40:14 -0700 Received: from ONERDEDGE02.one.nintendo.com (10.13.20.35) by ONERDEXCH01.one.nintendo.com (10.13.30.31) with Microsoft SMTP Server (TLS) id 14.3.174.1; Sat, 27 Sep 2014 04:40:24 -0700 Received: from barracuda3.noa.nintendo.com (205.166.76.35) by ONERDEDGE02.one.nintendo.com (10.13.20.35) with Microsoft SMTP Server (TLS) id 14.3.174.1; Sat, 27 Sep 2014 04:40:13 -0700 Received: from gateway07.websitewelcome.com (gateway07.websitewelcome.com [70.85.67.23]) by barracuda3.noa.nintendo.com with ESMTP id pQ1karfQRUUAEBFL (version=TLSv1 cipher=AES256-SHA bits=256 verify=NO) for <blah@nintendo.com>; Sat, 27 Sep 2014 04:50:32 -0700 (PDT) Received: by gateway07.websitewelcome.com (Postfix, from userid 5007) id DFB39B9D3B153; Sat, 27 Sep 2014 06:40:21 -0500 (CDT) Received: from mx.example.org (mx.example.org [192.186.4.46]) by gateway07.websitewelcome.com (Postfix) with ESMTP id DACE4B9D3B135 for <blah@nintendo.com>; Sat, 27 Sep 2014 06:40:21 -0500 (CDT)

You can use this material to map the network, as demonstrated by Figure 9-2. This diagram details the route that the message took from our source mail server (mx.example.org), through the Nintendo infrastructure, and back.

Figure 9-2. Mapping the target environment

In this case, the mail client selected an SMTP interface to use (upon obtaining the MX record of the target domain). During testing, you should take each enumerated domain, along with each exposed SMTP service and use Swaks1 to send email to a nonexistent user, as shown in Example 9-3. NDN results often vary based on the email route taken.

Example 9-3. Using Swaks to route email via specific SMTP interfaces

root@kali:~# dig +short mx nintendo.com 10 smtpgw1.nintendo.com. 20 smtpgw2.nintendo.com. root@kali:~# swaks -n -hr -f chris@example.org -t blah@nintendo.com -s smtpgw1.nintendo.com:25 === Trying smtpgw1.nintendo.com:25... === Connected to smtpgw1.nintendo.com. -> EHLO localhost -> MAIL FROM:<chris@example.org> -> RCPT TO:<blah@nintendo.com> -> DATA -> 9 lines sent -> QUIT === Connection closed with remote host. root@kali:~# swaks -n -hr -f chris@example.org -t blah@nintendo.com -s smtpgw2.nintendo.com:25 === Trying smtpgw2.nintendo.com:25... === Connected to smtpgw2.nintendo.com. -> EHLO localhost -> MAIL FROM:<chris@example.org> -> RCPT TO:<blah@nintendo.com> -> DATA -> 9 lines sent -> QUIT === Connection closed with remote host.

Note

When using Swaks, be sure to use an email account at which you can receive the NDN messages, along with a domain that lets you email from arbitrary sources (i.e., does not use SPF).

Identifying antivirus and content checking mechanisms

NDN messages might also contain headers generated by content filtering mechanisms (either distinct hardware appliances or software running on a mail server). Example 9-4 demonstrates the headers added by a Barracuda Networks content filter at barracuda.noa.nintendo.com.

Example 9-4. SMTP headers inserted by a content filter

X-Barracuda-Connect: gateway07.websitewelcome.com[70.85.67.23] X-Barracuda-Start-Time: 1411818632 X-Barracuda-Encrypted: AES256-SHA X-Barracuda-URL: http://barracuda.noa.nintendo.com:80/cgi-mod/mark.cgi X-Virus-Scanned: by bsmtpd at noa.nintendo.com X-Barracuda-Spam-Score: 0.00 X-Barracuda-Spam-Status: No, SCORE=0.00 using per-user scores of TAG_LEVE= L=2.0 QUARANTINE_LEVEL=1000.0 KILL_LEVEL=7.0 tests= X-Barracuda-Spam-Report: Code version 3.2, rules version 3.2.3.9943

Through sending messages with different contents, you can use responses to reverse engineer content filtering policy and antivirus configuration. For example, you can force identification and alerting of malicious content by sending an EICAR test file2 within an email.

Table 9-2 lists antivirus engines revealed upon parsing the EICAR test file, based on NDN headers received. Jon Oberheide and Farnam Jahanian published research that expands on this tactic.3

| Filter technology | Exposed information |

|---|---|

| Proofpoint and F-Secure |

X-Proofpoint-Virus-Version: vendor=fsecure engine=2.50.10432:5.11.87,1.0.14,0.0.0000 definitions=2013-12-12_01:2013-12-11,2013-12-12,1970-01-01, signatures=0 |

| Proofpoint and McAfee |

X-Proofpoint-Virus-Version: vendor=nai engine=5400 definitions=5800 signatures=585085 |

| Cisco IronPort and Sophos |

X-IronPort-AV: E=Sophos;i="4.27,718,1204520400"; v="EICAR-AV-Test'3'rd"; d="txt'?com'?scan'208";a="929062" |

| Cisco IronPort and McAfee |

X-IronPort-AV: E=McAfee;i="5400,1158,7286"; a="160098426" |

| Trend Micro |

X-TM-AS-Product-Ver: CSC-0-5.5.1026-15998 X-TM-AS-Result: No-10.22-4.50-31-1 |

| McAfee |

The WebShield(R) e500 Appliance discovered a virus in this file. The file was not cleaned and has been removed. |

| Barracuda Networks |

X-Barracuda-Virus-Scanned: by Barracuda Spam & Virus Firewall at example.org |

Known antivirus engine defects

Upon identifying the deployed antivirus engine you can exploit defects by sending malicious content via SMTP. Remotely exploitable flaws have been found in ClamAV, ESET, Kaspersky, Sophos, and Symantec engines in particular, as listed in Table 9-3. Unfortunately, an increasing number of these issues do not have CVE references.

| CVE reference(s) | Vendor | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CVE-2016-2208 | Symantec | ASPack remote heap memory corruption flawa |

| — | Kaspersky | Multiple severe parsing flaws, as discovered by Tavis Ormandyb,c,d |

| ESET | ||

| Sophos | ||

|

CVE-2010-4479 CVE-2010-4261 CVE-2010-4260 |

ClamAV | Multiple parsing overflows within ClamAV 0.96.4 |

a Tavis Ormandy, “Symantec/Norton Antivirus ASPack Remote Heap/Pool memory corruption Vulnerability CVE-2016-2208”, Chromium.org, May 6, 2016. b Tavis Ormandy, “Kaspersky: Mo Unpackers, Mo Problems”, Google’s Project Zero Blog, September 22, 2015. c Tavis Ormandy, “Analysis and Exploitation of an ESET Vulnerability”, Google’s Project Zero Blog, June 23, 2015. d See “Tavis Ormandy Finds Vulnerabilities in Sophos Anti-Virus Products”, Sophos Knowledge Base, June 30, 2015. | ||

Enumerating Supported Commands and Extensions

Exploitable SMTP vulnerabilities often relate to particular server subsystems. Example 9-5 demonstrates manual enumeration via HELP and EHLO commands, along with automated testing using the Nmap smtp-commands script.

Example 9-5. Enumerating supported SMTP commands

root@kali:~# telnet microsoft-com.mail.protection.outlook.com 25

Trying 207.46.163.138...

Connected to microsoft-com.mail.protection.outlook.com.

Escape character is '^]'.

220 BN1AFFO11FD016.mail.protection.outlook.com Microsoft

ESMTP MAIL Service ready at Thu, 11 Sep 2014 15:36:23 +0000

HELP

214-This server supports the following commands:

214 HELO EHLO STARTTLS RCPT DATA RSET MAIL QUIT HELP AUTH BDAT

EHLO world

250-BN1AFFO11FD016.mail.protection.outlook.com Hello [37.205.58.146]

250-SIZE 157286400

250-PIPELINING

250-DSN

250-ENHANCEDSTATUSCODES

250-8BITMIME

250-BINARYMIME

250 CHUNKING

QUIT

221 2.0.0 Service closing transmission channel

Connection closed by foreign host.

root@kali:~# nmap -p25 --script smtp-commands 207.46.163.138

Starting Nmap 6.46 (http://nmap.org) at 2014-09-29 18:37 BST

Nmap scan report for mail-bn14138.inbound.protection.outlook.com (207.46.163.138)

PORT STATE SERVICE

25/tcp open smtp

| smtp-commands: BN1AFFO11FD016.mail.protection.outlook.com Hello [78.145.30.139],

| SIZE 157286400, PIPELINING, DSN, ENHANCEDSTATUSCODES, 8BITMIME, BINARYMIME,

| CHUNKING,

|_ This server supports the following commands: HELO EHLO STARTTLS RCPT DATA RSET MAIL QUIT HELP

AUTH BDAT

Table 9-4 describes the commands supported by this SMTP server (this is not an exhaustive list), and Table 9-5 outlines the enabled extensions and features. The DSN extension,4 for example, is not a command, but a mechanism to provide delivery status notification.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

HELO |

Initiates an SMTP conversation |

EHLO |

Initiates an ESMTP conversation |

STARTTLS |

Initiates an encrypted TLS session over the existing porta |

RCPT |

Defines the destination email address |

DATA |

Signifies that data (i.e., the message body) will follow |

RSET |

Aborts the current mail transaction |

| Defines the source email address | |

QUIT |

Ends the SMTP session and closes the connection |

HELP |

Presents help material back to the client |

AUTH |

SMTP authentication support |

BDAT |

Signifies that binary data will follow |

| Extension | Description |

|---|---|

SIZE 157286400 |

Limits the maximum message size to 15.7 MB |

PIPELINING |

Supports batching of SMTP commands without waiting for individual responses for each |

DSN |

Delivery status notification support |

ENHANCEDSTATUSCODES |

Provides detailed SMTP status codesa |

8BITMIME |

8-bit data transmission support |

BINARYMIME |

Binary data transmission support |

CHUNKING |

Support for sending binary chunks via BDAT |

a See “Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) Enhanced Status Codes Registry” on IANA.org. | |

As noted earlier, lists are not exhaustive. Daniel J. Bernstein prepared an SMTP primer5 that contains useful information, which you can combine with the Wikipedia entry6 to delve into particular extensions.

Remotely Exploitable Flaws

SMTP server software may be found running on appliances (e.g., Barracuda Spam Firewall and Cisco IronPort), lightweight MTAs (e.g., qmail and Exim), and feature-rich mail server platforms (e.g., Microsoft Exchange and Sendmail).

According to NVD at the time of writing, there are no known exploitable flaws in the Barracuda Spam Firewall, Cisco IronPort, or Proofpoint platforms with SMTP vectors. Many web application defects exist within these products, however (e.g., XSS, command injection, and data exposure), which are exploitable via exposed HTTP and HTTPS interfaces.

Remotely exploitable vulnerabilities in popular mail server software packages (Exim, Postfix, Sendmail, Microsoft Exchange, and IBM Domino) are detailed in Tables 9-6 through 9-10.

| CVE reference(s) | Affects (up to) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CVE-2014-2957 | Exim 4.82 | DMARC header parsing overflow |

| CVE-2012-5671 | Exim 4.80 | DKIM record parsing vulnerabilities |

|

CVE-2011-1764 CVE-2011-1407 |

Exim 4.75 | |

| CVE-2010-4344 | Exim 4.69 | Remote overflow resulting in code execution |

| CVE reference | Affects (up to) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CVE-2011-1720 |

Postfix 2.8.0 to 2.8.2 Postfix 2.7.0 to 2.7.3 Postfix 2.6.0 to 2.6.9 Postfix 2.5.13 and prior |

Cyrus SASL authentication overflow |

| CVE reference | Affects (up to) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CVE-2009-4565 | Sendmail 8.4.13 | TLS authentication bypass permitting MITM and circumvention of access restrictions |

| CVE-2009-1490 | Sendmail 8.13.1 | Heap overflow triggered via long “X-” header values |

| CVE reference | Affected products | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CVE-2014-0294 | Forefront Protection 2010 for Exchange | Buffer overflow resulting in remote code execution upon parsing malicious content |

| CVE-2010-0025 | Windows Server 2008 R2, Exchange Server 2000 SP3, and others | SMTP engine overflow within multiple products resulting in arbitrary code execution |

| CVE-2009-0098 | Exchange Server 2007 SP1 | TNEF overflow vulnerability |

| CVE reference(s) | Affects (up to) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CVE-2011-0916 | Domino 8.5.2 | Stack overflow in SMTP service via long filename parameter within MIME headers |

|

CVE-2011-0915 CVE-2010-3407 |

Multiple flaws when processing email messages containing iCalendar requests |

User Account Enumeration

Sendmail and other servers permit mailbox and local user account enumeration. Within Kali Linux, you can use the smtp-user-enum utility to identify accounts through the EXPN, VRFY, and RCPT TO commands. In the following sections, I manually demonstrate each technique.

EXPN

The EXPN command expands details for a given mail address, as shown in Example 9-6. Through analyzing the server responses, we find the test user account doesn’t exist, mail for root is forwarded to chris@example.org, and an sshd account exists for privilege separation purposes.

Example 9-6. Using EXPN to enumerate local users

root@kali:~# telnet 10.0.10.11 25 Trying 10.0.10.11... Connected to 10.0.10.11. Escape character is '^]'. 220 mail2 ESMTP Sendmail 8.13.8/8.12.8; Thu, 13 Nov 2014 03:20:37 HELO world 250 mail2 Hello onyx [192.168.10.1] (may be forged), pleased to meet you EXPN test 550 5.1.1 test... User unknown EXPN root 250 2.1.5 <chris@example.org> EXPN sshd 250 2.1.5 sshd privsep <sshd@mail2>

VRFY

The VRFY command verifies that a given SMTP mail address is valid, as shown in Example 9-7. We can abuse this feature to enumerate local accounts (chris in this case).

Example 9-7. Using VRFY to enumerate local users

root@kali:~# telnet 10.0.10.11 25 Trying 10.0.10.11... Connected to 10.0.10.11. Escape character is '^]'. 220 mail2 ESMTP Sendmail 8.13.8/8.12.8; Thu, 13 Nov 2014 04:01:18 HELO world 250 mail2 Hello onyx [192.168.10.1] (may be forged), pleased to meet you VRFY test 550 5.1.1 test... User unknown VRFY chris 250 2.1.5 Chris McNab <chris@mail2>

RCPT TO

Many administrators ensure that EXPN and VRFY commands don’t return user information; however, RCPT TO enumeration exploits a flaw that is not easily mitigated within Sendmail in particular. Example 9-8 demonstrates the command used to identify valid local users accounts.

Example 9-8. Using RCPT TO to enumerate local users

root@kali:~# telnet 10.0.10.11 25 Trying 10.0.10.11... Connected to 10.0.10.11. Escape character is '^]'. 220 mail2 ESMTP Sendmail 8.13.8/8.12.8; Thu, 13 Nov 2014 04:03:52 HELO world 250 mail2 Hello onyx [192.168.10.1] (may be forged), pleased to meet you MAIL FROM:test@test.org 250 2.1.0 test@test.org... Sender ok RCPT TO:test 550 5.1.1 test... User unknown RCPT TO:admin 550 5.1.1 admin... User unknown RCPT TO:chris 250 2.1.5 chris... Recipient ok

Brute-Force Password Grinding

Example 9-9 demonstrates the EHLO command used to identify supported authentication mechanisms (in this case, LOGIN, PLAIN, and CRAM-MD5, which an attacker can use to perform brute-force password grinding against valid accounts).

Example 9-9. Enumerating authentication methods by using EHLO

root@kali:~# telnet mail.example.org 25 Trying 192.168.0.25... Connected to 192.168.0.25. Escape character is '^]'. 220 mail.example.org ESMTP EHLO world 250-mail.example.org 250-AUTH LOGIN CRAM-MD5 PLAIN 250-AUTH=LOGIN CRAM-MD5 PLAIN 250-STARTTLS 250-PIPELINING 250 8BITMIME

Table 7-19 lists common SMTP authentication mechanisms used within SMTP and other services, which are also supported by Hydra and Nmap.7 Example 9-10 demonstrates Hydra run against an exposed SMTP service supporting CRAM-MD5.

Example 9-10. SMTP brute-force password grinding using Hydra

root@kali:~# wget http://bit.ly/2b5K8Hi root@kali:~# unzip wordlists.zip root@kali:~# hydra -L users.txt -P crackdict.txt smtp://mail.example.org/CRAM-MD5 Hydra v8.1 (c) 2014 by van Hauser/THC - Please do not use in military or secret service organizations, or for illegal purposes. Hydra (http://www.thc.org/thc-hydra) starting at 2015-10-14 19:36:40 [INFO] several providers have implemented cracking protection, check with a small wordlist first - and stay legal! [DATA] max 16 tasks per 1 server, overall 64 tasks, 655041 login tries (l:3/p:218347), ~639 tries per task [DATA] attacking service smtp on port 25 [25][smtp] host: mail.example.org login: chris password: control!

Content Checking Circumvention

Organizations run content checking software to scrub mail in adherence with a given policy. Server and client software packages parse material sent via email in different ways, and flaws exist within filtering software and associated components (i.e., antivirus engines).

Many years ago, I bypassed Clearswift MAILsweeper by modifying MIME headers within a message. Example 9-11 shows a legitimate email generated by Microsoft Outlook, from john@example.org to mickey@example.org with the attachment report.txt.

Example 9-11. A Microsoft Outlook-generated message with an attachment

From: John Smith <john@example.org>

To: Mickey Mouse <mickey@example.org>

Subject: That report

Date: Thurs, 22 Feb 2001 13:38:19 -0000

MIME-Version: 1.0

X-Mailer: Internet Mail Service (5.5.23)

Content-Type: multipart/mixed ;

boundary="----_=_NextPart_000_02D35B68.BA121FA3"

Status: RO

This message is in MIME format. Since your mail reader doesn't understand this format, some or

all of this message may not be legible.

- ------_=_NextPart_000_02D35B68.BA121FA3

Content-Type: text/plain; charset="iso-8859-1"

Mickey,

Here's that report you were after.

- ------_=_NextPart_000_02D35B68.BA121FA3

Content-Type: text/plain;

name="report.txt"

Content-Disposition: attachment;

filename="report.txt"

< data for the text document here >

- ------_=_NextPart_000_02D35B68.BA121FA3

An exploitable condition existed because of the way in which the content checking system and client software parsed an attachment’s MIME headers—MAILsweeper used name and Microsoft Outlook filename. The headers could be modified to present a benign text file to MAILsweeper and malicious VBScript to the user via Outlook:

- ------_=_NextPart_000_02D35B68.BA121FA3

Content-Type: text/plain;

name="report.txt"

Content-Disposition: attachment;

filename="report.vbs"

This tactic is similar to one adopted when circumventing a network IPS by fragmenting and sending packets out of order—we modify data so that it clears the security control and then is reassembled at the destination. During testing it is important to consider variations of this tactic and identify exploitable conditions.

Review of Mail Security Features

SMTP messages are easily spoofed, and so organizations use SPF, DKIM, and DMARC features to prevent parties from sending unauthorized email. These mechanisms, along with the steps you can take to review their configuration, are outlined in the following sections.

SPF

Sender Policy Framework (SPF)8 provides a mechanism by which MTAs can check if the host sending email for a given domain is authorized. Organizations define the list of authorized mail servers for a domain within a specially formatted TXT DNS record.

We can evaluate the SPF configuration of Google via dig, as shown in Example 9-12. Large organizations often use include and redirect directives, and you must iteratively step through each record to understand the configuration. In this example, the IPv6 and IPv4 ranges returned are authorized sources.

Example 9-12. Using dig to review SPF configuration

root@kali:~# dig google.com txt | grep spf google.com. 1599 IN TXT "v=spf1 include:_spf.google.com ip4:216.73.93.70/31 ip4:216.73.93.72/31 ~all" root@kali:~# dig _spf.google.com txt | grep spf _spf.google.com. 246 IN TXT "v=spf1 include:_netblocks.google.com include: _netblocks2.google.com include:_netblocks3.google.com ~all" root@kali:~# dig _netblocks.google.com txt | grep spf _netblocks.google.com. 2616 IN TXT "v=spf1 ip4:216.239.32.0/19 ip4:64.233.160.0/19 ip4:66.249.80.0/20 ip4:72.14.192.0/18 ip4:209.85.128.0/17 ip4:66.102.0.0/20 ip4:74.125.0.0/16 ip4:64.18.0.0/20 ip4:207.126.144.0/20 ip4:173.194.0.0/16 ~all" root@kali:~# dig _netblocks2.google.com txt | grep spf _netblocks2.google.com. 3565 IN TXT "v=spf1 ip6:2001:4860:4000::/36 ip6:2404:6800:4000::/36 ip6:2607:f8b0:4000::/36 ip6:2800:3f0:4000::/36 ip6:2a00:1450:4000::/36 ip6:2c0f:fb50:4000::/36 ~all" root@kali:~# dig _netblocks3.google.com txt | grep spf _netblocks3.google.com. 3196 IN TXT "v=spf1 ~all"

DKIM

DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM)9 is a mechanism by which outbound email is signed and validated by foreign MTAs upon retrieving a domain’s public key via DNS. The DKIM public key is held within a TXT record for a domain; however, you must know both the selector and domain name to retrieve it.

Upon reviewing the headers of email via gmail.com, the DKIM signature is retrieved:

DKIM-Signature: v=1; a=rsa-sha256; c=relaxed/relaxed;d=gmail.com;s=20120113; h=mime-version:x- received:date:message-id:subject:from:to:content-type; bh=fd9JXP6Ngw+hgcG1EbBo7GpsrIIZzdJb9Q/14o 9e5C8=; b=sYlJC2oYWzBUOPIo0jtR4iFsIVqUlwo2QRcG1186hg5ai0oO1nisiOJUD+QXjt

The d and s values are combined and fed into dig, as shown in Example 9-13.

Example 9-13. Using dig to retrieve the DKIM public key

root@kali:~# dig 20120113._domainkey.gmail.com TXT | grep p= 20120113._domainkey.gmail.com. 280 IN TXT "k=rsa\; p=MIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8AMIIBCg KCAQEA1Kd87/UeJjenpabgbFwh+eBCsSTrqmwIYYvywlbhbqoo2DymndFkbjOVIPIldNs/m40KF+yzMn1skyoxcTUGCQs8g3 FgD2Ap3ZB5DekAo5wMmk4wimDO+U8QzI3SD0" "7y2+07wlNWwIt8svnxgdxGkVbbhzY8i+RQ9DpSVpPbF7ykQxtKXkv/ahW 3KjViiAH+ghvvIhkx4xYSIc9oSwVmAl5OctMEeWUwg8Istjqz8BZeTWbf41fbNhte7Y+YqZOwq1Sd0DbvYAD9NOZK9vlfuac 0598HY+vtSBczUiKERHv1yRbcaQtZFh5wtiRrN04BLUTD21MycBX5jYchHjPY/wIDAQAB"

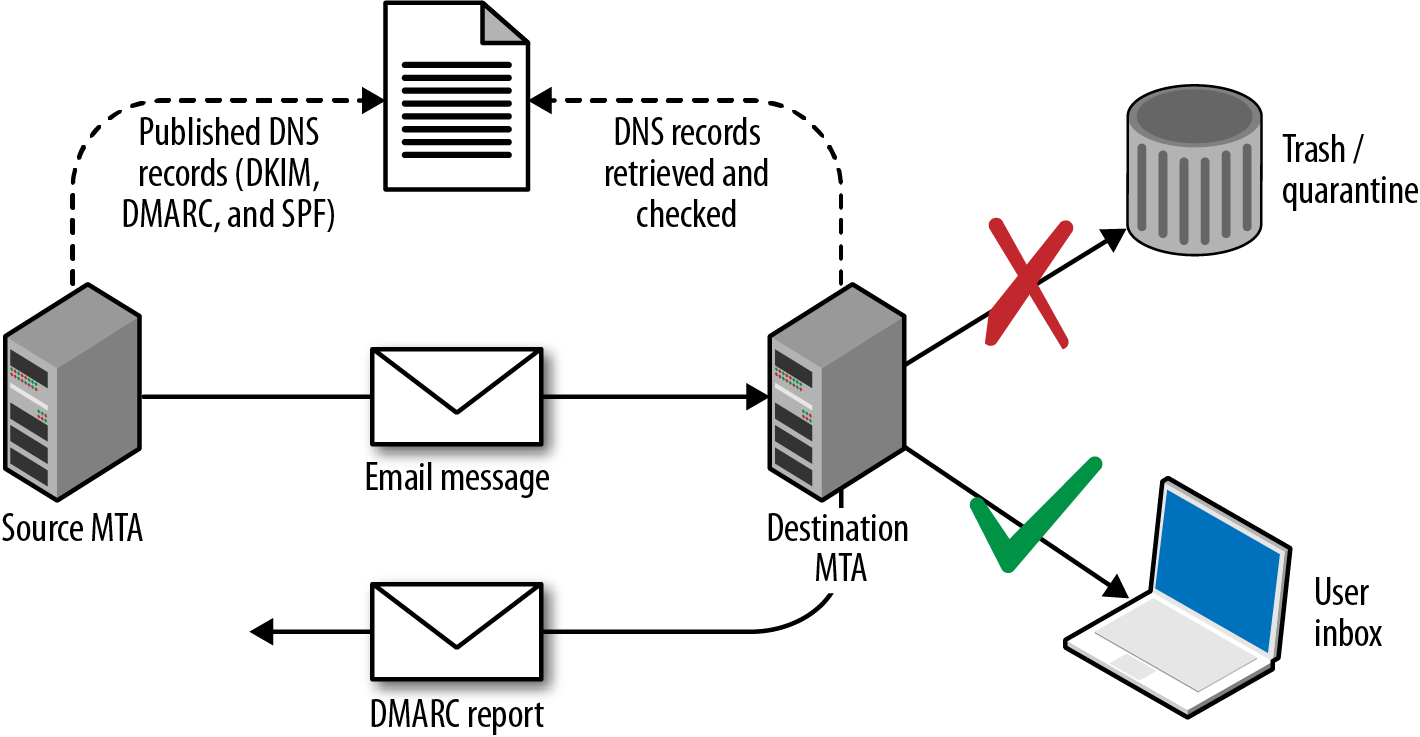

DMARC

Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting & Conformance (DMARC)10 is a method of mail authentication that expands upon SPF and DKIM. Policies instruct mail servers how to process email for a given domain and report upon actions performed. The way in which DMARC is used along with SPF and DKIM is shown in Figure 9-3.

Figure 9-3. DMARC, SPF, and DKIM

DMARC policies are distributed via DNS. Table 9-11 lists fields and example values, and Example 9-14 demonstrates the policies used by Google, Yahoo, and PayPal.

| Name | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

v |

Protocol version | v=DMARCv1 |

p |

Requested handling policy for email originating from the domain (i.e., none, quarantine, or reject) | p=quarantine |

sp |

Requested policy for subdomains | sp=reject |

pct |

Apply the policy to a certain percentage of messages (used to control DMARC uptake and avoid unintended report flooding) | pct=20 |

ruf |

Reporting URI for forensic reports | ruf=mailto:authfail@example.org |

rua |

Reporting URI for aggregate reports | rua=mailto:aggrep@example.org |

rf |

Defines the forensic reporting format | rf=afrf |

ri |

Defines the aggregate report interval | ri=86400 |

adkim |

DKIM alignment mode r (relaxed) is the default, and s enforces strict | adkim=s |

aspf |

SPF alignment mode using the same values as the DKIM alignment mode | aspf=r |

Example 9-14. Retrieving DMARC policies via dig

root@kali:~# dig _dmarc.yahoo.com txt | grep DMARC _dmarc.yahoo.com. 1785 IN TXT "v=DMARC1\; p=reject\; sp=none\; pct=100\; rua=mailto:dmarc-yahoo-rua@yahoo-inc.com, mailto:dmarc_y_rua@yahoo.com\;" root@kali:~# dig _dmarc.google.com txt | grep DMARC _dmarc.google.com. 600 IN TXT "v=DMARC1\; p=quarantine\; rua=mailto:mailauth-reports@google.com" root@kali:~# dig _dmarc.paypal.com txt | grep DMARC _dmarc.paypal.com. 300 IN TXT "v=DMARC1\; p=reject\; rua=mailto:d@rua.agari.com\; ruf=mailto:dk@bounce.paypal.com,mailto:d@ruf.agari.com"

PayPal and Yahoo instruct mail servers to reject messages that contain invalid DKIM signatures or do not originate from their networks. Notifications are then sent to the respective email addresses within each organization. Google is configured in a similar way, although it instructs mail servers to quarantine messages and not outright reject them.

Phishing via SMTP

By sending crafted email, it is possible to dupe users into clicking hyperlinks, providing credentials, and executing code (e.g., JavaScript and Microsoft Office macros). Depending on the organization’s mail security features and configuration, you can also spoof internal email via external SMTP interfaces.

In the following sections, I describe a high-level approach to phishing. The Social Engineer Toolkit (SET)11 within Kali Linux is a powerful platform from which you can mount phishing campaigns.

Reconnaissance

Effective campaigns fool safety-conscious users by using knowledge of the target environment. Important details to focus on are as follows:

-

Address format and naming convention (e.g., Smith, Stan <stan.smith@intel.com>)

-

Client software used within the organization (e.g., Microsoft Outlook)

-

Message details or quirks, including signature formats adopted by certain users

-

Identifying a candidate web interface to clone

You can cover the first three bullets in the preceding list by obtaining material originating from the organization (e.g., email containing headers and HTML content). Mailing list archives and Google are good candidates, along with user coercion by requesting information from marketing or sales departments.

If an organization uses multifactor authentication for remote access purposes, you can subvert this by cloning the SSL VPN web endpoint to capture credentials and immediately replaying them to legitimate services.

Landing page preparation

You can use SET to clone a login page and harvest credentials. To get the best results, I would recommend going an extra step by registering a domain for use during the campaign, obtaining a valid TLS certificate, and using stunnel to broker the HTTPS traffic between the victim and SET.

For example, if the cloned web endpoint is vpn.victim.com, consider acquiring victim-corp.com, setting up the DNS so that sslvpn.victim-corp.com points to your SET instance, and purchasing the associated certificate so that the user sees a legitimate-looking encrypted connection.

SET is a powerful utility with rich functionality. You can use it to both harvest credentials (via traditional phishing attack) and exploit vulnerable browser plug-ins and components to gain code execution.12

Sending email

The Spearphishing module within SET uses the Sendmail MTA in Kali Linux to send email. For the best result, however, consider manually crafting an email message from the previously obtained materials (using the same font and message format as a legitimate email), piping this material via Swaks to your local Sendmail service, and onto the target SMTP server.

It is important to evaluate the security posture of the target before proceeding. Review SPF, DKIM, and DMARC policies (if any), and assess the behavior of exposed SMTP interfaces to see whether they will accept material from an internal domain. If the environment is hardened, you will need to set up a domain from which to send email (victim-corp.com, for example).

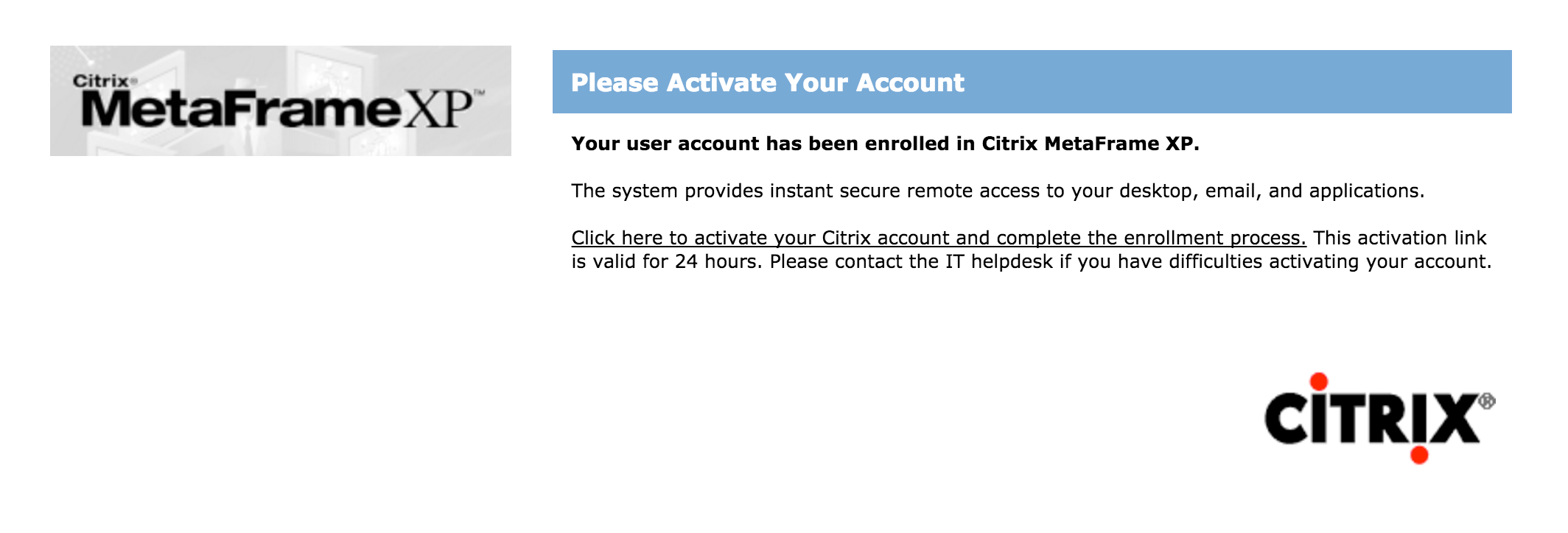

Figure 9-4 demonstrates an effective HTML email spoofed from the IT department of a company. The look and feel of the email is critical, and the language is important because you want to dictate a sense of urgency for users to click the malicious link.

Figure 9-4. HTML phishing email content

Factors that can affect the success of a phishing campaign include:

-

SMTP interfaces not accepting email from the public Internet that is sent from a domain that is internal to the organization

-

Use of content filtering to add material to the subject line of email originating from outside of the organization (e.g., an external or untrusted designator)

-

Presence of web proxy appliances evaluating the reputation of destination URLs

-

Use of particular browsers or desktop software clients

Eric Smith’s 2013 DerbyCon presentation13 chronicles a number of successful professional social engineering campaigns, detailing tactics used to do the following:

-

Ensure that URLs used within a campaign are marked as reputable online

-

Ensure that the mail server used to launch a campaign also seems reputable

-

Measure the efficacy of a campaign by tracking session identifiers

-

Take advantage of privileged access (via OWA or VPN) to gain intelligence

-

Preoccupy and distract incident response teams

Through reconnaissance, proper staging (provisioning of domains, certificates, and reputable web and mail server addresses), and focused execution, you will likely succeed through phishing. By preparing a number of redundant attack platforms and distracting the security team of the target, you should also be able to achieve persistence.

POP3

Mail server packages offer POP3 services (e.g., Courier, Dovecot, and Microsoft Exchange). If packages aren’t maintained, attackers can exploit defects to compromise the system. At the time of writing, however, the only remotely exploitable POP3 vulnerability found within NVD is an IBM Domino flaw.14

Service Fingerprinting

POP3 presents a banner upon connection that often describes the hostname and implementation. If the banner lacks detail, use Nmap to fingerprint the service and enumerated features, as demonstrated by Example 9-15.

Example 9-15. Fingerprinting a POP3 services by using Nmap

root@kali:~# nmap -sV -p110,995 --script pop3-capabilities 85.214.111.132 Starting Nmap 6.49BETA4 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2015-10-14 19:09 EDT Nmap scan report for h2080641.stratoserver.net (85.214.111.132) PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION 110/tcp open pop3 Courier pop3d | pop3-capabilities: LOGIN-DELAY(10) SASL(LOGIN CRAM-MD5 PLAIN) IMPLEMENTATION(Courier Mail |_ Server) APOP UIDL USER TOP STLS PIPELINING 995/tcp open ssl/pop3 Courier pop3d | pop3-capabilities: LOGIN-DELAY(10) SASL(LOGIN CRAM-MD5 PLAIN) IMPLEMENTATION(Courier Mail |_ Server) APOP UIDL USER TOP PIPELINING Service Info: Host: localhost.localdomain

Brute-Force Password Grinding

Mail servers are a target for brute-force password grinding for several reasons:

-

Implementations often don’t pay attention to account lockout policies

-

POP3 and IMAP servers honor multiple login attempts before disconnecting

-

Many mail servers don’t log unsuccessful login attempts

Clients can authenticate with POP3 services by using plaintext or MD5 digest authentication. The digest mechanism (using the APOP directive) is susceptible to network sniffing and attack via Cain & Abel and other tools because the implementation has a known plaintext flaw.15

To mitigate these risks, many POP3 servers support additional mechanisms via SASL, including DIGEST-MD5 and NTLM. Hydra supports a number of SASL mechanisms.16 Example 9-16 shows Hydra used to perform brute-force password grinding against an exposed POP3S service with basic MD5 authentication (via APOP).

Example 9-16. Hydra used to perform POP3S password grinding

root@kali:~# hydra -L users.txt -P crackdict.txt pop3s://mail.example.org Hydra v8.1 (c) 2014 by van Hauser/THC - Please do not use in military or secret service organizations, or for illegal purposes. Hydra (http://www.thc.org/thc-hydra) starting at 2015-10-14 19:17:45 [INFO] several providers have implemented cracking protection, check with a small wordlist first - and stay legal! [DATA] max 16 tasks per 1 server, overall 64 tasks, 655041 login tries (l:3/p:218347), ~639 tries per task [DATA] attacking service pop3 on port 995 with SSL [995][pop3] host: mail.example.org login: chris password: control!

IMAP

The IMAP protocol is similar to POP3. As such, exposed services are susceptible to brute-force password grinding and process manipulation attacks (upon identifying exploitable software flaws).

Service Fingerprinting

IMAP presents a banner to the client upon connection that often describes the hostname and implementation. If the banner lacks detail, use Nmap to fingerprint the service and list capabilities, as demonstrated by Example 9-17.

Example 9-17. Fingerprinting IMAP services by using Nmap

root@kali:~# nmap -sV -p143,993 --script imap-capabilities 85.214.111.174 Starting Nmap 6.49BETA4 (https://nmap.org) at 2015-10-14 19:28 EDT Nmap scan report for h2080641.stratoserver.net (85.214.111.174) PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION 143/tcp open imap Plesk Courier imapd | imap-capabilities: ACL2=UNION QUOTA completed ACL NAMESPACE IMAP4rev1 IDLE | THREAD=ORDEREDSUBJECT OK CAPABILITY SORT AUTH=CRAM-MD5 AUTH=PLAIN UIDPLUS |_ STARTTLSA0001 CHILDREN THREAD=REFERENCES 993/tcp open ssl/imap Plesk Courier imapd | imap-capabilities: ACL2=UNIONA0001 QUOTA completed ACL NAMESPACE IMAP4rev1 IDLE | THREAD=ORDEREDSUBJECT OK CAPABILITY SORT AUTH=CRAM-MD5 AUTH=PLAIN UIDPLUS |_ CHILDREN THREAD=REFERENCES

Brute-Force Password Grinding

Clients authenticate with IMAP via the plaintext LOGIN method or AUTHENTICATE, which uses SASL mechanisms. Hydra supports many of these, as demonstrated by Example 9-18.

Example 9-18. Listing Hydra’s available IMAP brute-force options

root@kali:~# hydra imap -U Hydra v8.1 (c) 2014 by van Hauser/THC - Please do not use in military or secret service organizations, or for illegal purposes. Hydra (http://www.thc.org/thc-hydra) starting at 2015-10-14 19:54:40 Help for module imap: ============================================================================ Module imap is optionally taking one authentication type of: CLEAR or APOP (default), LOGIN, PLAIN, CRAM-MD5, CRAM-SHA1, CRAM-SHA256, DIGEST-MD5, NTLM Additionally TLS encryption via STARTTLS can be enforced with the TLS option. Example: imap://target/TLS:PLAIN

Known IMAP Server Flaws

Table 9-12 lists remotely exploitable IMAP server vulnerabilities. The Novell flaws require valid credentials to exploit logic that is exposed after authentication.

| CVE reference | Vendor | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CVE-2011-0919 | IBM | Multiple stack overflows in IBM Domino POP3 and IMAP services resulting in remote code execution |

CVE-2010-4717 CVE-2010-4711 CVE-2010-2777 |

Novell | Multiple overflows in Novell GroupWise Internet Agent (GWIA) resulting in arbitrary code execution upon providing malicious commands |

Mail Services Testing Recap

What follows is a concise list of the tactics discussed in this chapter:

- Service identification

- Nmap is effective at fingerprinting mail services and enumerating supported features (e.g., authentication mechanisms). Combine automated discovery with manual validation to correctly identify each exposed service and its features.

- NDN review

- Use Swaks to relay messages via each exposed SMTP gateway, destined for nonexistent users within each known domain. Upon identifying servers that respond with NDN messages, use the behavior to reveal internal IP address and hostname details, software versions, and content filtering policies.

- User enumeration

- You can quiz accessible SMTP services (Sendmail in particular) to obtain local user account details via the smtp-user-enum utility within Kali Linux. Hydra and Nmap also include modules to perform enumeration.

- Brute-force password grinding

- Upon preparing a list of valid user accounts, the authentication mechanisms within exposed mail services can be attacked using Hydra, Nmap, and Swaks. Brute-force via mail services is effective because audit logs are often not scrutinized, and account lockout policies might not be honored.

- Phishing

- Depending on the level of access you might obtain (unauthenticated or authenticated) and the configuration of the target environment, you can seek to launch a convincing phishing campaign and dupe users. The SET within Kali Linux automates the phishing process.

- Exploiting known flaws in mail software

- Mail systems are nebulous and have large attack surfaces (think SMTP, IMAP, and POP3 server software, antivirus and content checking engines, and mail client applications running on user devices). Upon identifying a particular antivirus engine, commercial content checking appliance, mail server, or client, you can seek to exploit known vulnerabilities.

Mail Services Countermeasures

You should consider the following countermeasures when hardening mail systems:

-

Don’t expose feature-rich SMTP servers to the public Internet or untrusted networks. Sendmail and Microsoft Exchange have large codebases and introduce unnecessary exposure. Use a dedicated content filter (either in the form of a physical appliance or cloud service) to parse email, or deploy a lightweight MTA such as qmail or Exim.

-

Use SPF, DKIM, and DMARC to prevent transmission and receipt of unauthorized content by your servers. Also, configure exposed SMTP interfaces to not accept email from untrusted networks (e.g., the public Internet) that are apparently from a domain internal to your organization.

-

Configure external content filtering mechanism to add material to the subject field of email originating outside of the environment (e.g., a string notifying the user that the message is from an untrusted source).

-

Use of antivirus and content filtering software increases your attack surface, and exploitable flaws exist in such packages. Ensure that filtering and antivirus software is patched up to date.

-

Disable support for weak authentication mechanisms within your mail services (e.g.,

LOGIN,PLAIN, andCRAM-MD5). If authentication is not used by SMTP, disable the functionality completely. -

Enforce TLS where possible (between both SMTP servers, and services supporting collection of email over POP3 and IMAP). Consider client certificates to provide an additional layer of authentication, and prevent unauthorized parties from interacting with services.

-

Minimize the impact of brute-force password grinding attacks by enforcing a strong password policy on your mail servers (covering all vectors).

-

Increase visibility by logging failed authentication attempts made against mail services. Account lockout policies may also be defined within some platforms (e.g., Microsoft Windows), which will mitigate brute-force password grinding risks.

1 John Jetmore, “Swaks - Swiss Army Knife for SMTP”, Jetmore.org.

2 See https://www.eicar.org/download/eicar.com.txt.

3 Jon Oberheide and Farnam Jahanian, “Remote Fingerprinting and Exploitation of Mail Server Antivirus Engines”, University of Michigan Technical Report CSE-TR-552-09, Ann Arbor, MI, June 2009.

5 D. J. Bernstein, “SMTP: Simple Mail Transfer Protocol”, cr.yp.to.

6 See “Extended SMTP” on Wikipedia.

7 Nmap smtp-brute script.

11 See “The Social-Engineer Toolkit (SET)” on TrustedSec.com.

12 There are countless videos and tutorials online demonstrating its features, including Javi Oliu, “Social Engineering Toolkit”, YouTube video, posted May 24, 2014, and Jeremy Martin, “Exploitation with Social Engineering Toolkit SET”, YouTube video, posted April 21, 2013.

13 Eric Smith, “DerbyCon Cheat Codez: Level Up Your SE Game”, YouTube video, posted by Adrian Crenshaw on September 30, 2013.

14 See CVE-2011-0919.

15 Fanbao Liu et al., “Fast Password Recovery Attack: Application to APOP”, Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 25, no. 2 (2014): 251–261.

16 See “Comparison of Features and Services Coverage” on THC.org.