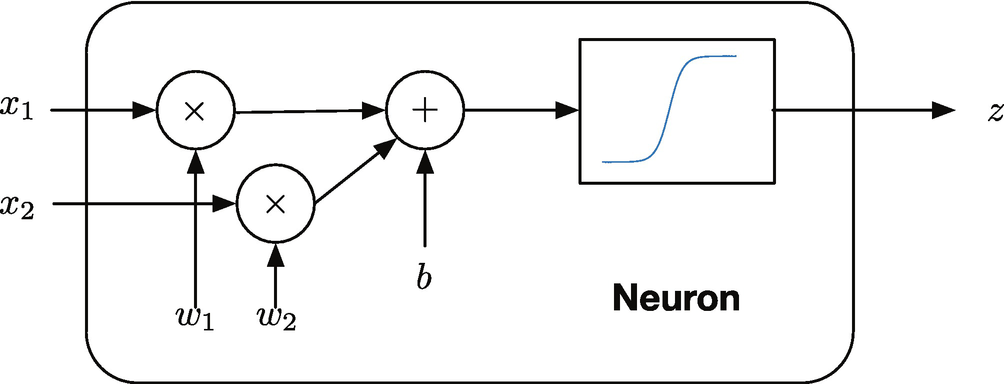

Neural networks, or neural nets, are a popular way of implementing machine “intelligence.” The idea is that they behave like the neuron in a brain. In our taxonomy, neural nets fall into the category of true machine learning, as shown on the right.

In this chapter, we will explore how neural nets work, starting with the most fundamental idea with a single neuron and working our way up to a multi-layer neural net. Our example for this will be a pendulum. We will show how a neural net can be used to solve the prediction problem. This is one of the two uses of a neural net, prediction and categorization. We’ll start with a simple categorization example. We’ll do more sophisticated categorization neural nets in chapters 9 and 10.

8.1 Daylight Detector

8.1.1 Problem

We want to use a simple neural net to detect daylight.

8.1.2 Solution

Historically, the first neuron was the perceptron. This is a neural net with an activation function that is a threshold. Its output is either 0 or 1. This is not really useful for problems such as the pendulum angle estimation covered in the remaining recipes of this chapter. However, it is well suited to categorization problems. We will use a single perceptron in this example.

8.1.3 How It Works

Suppose our input is a light level measured by a photo cell. If you weight the input so that 1 is the value defining the brightness level at twilight, you get a sunny day detector.

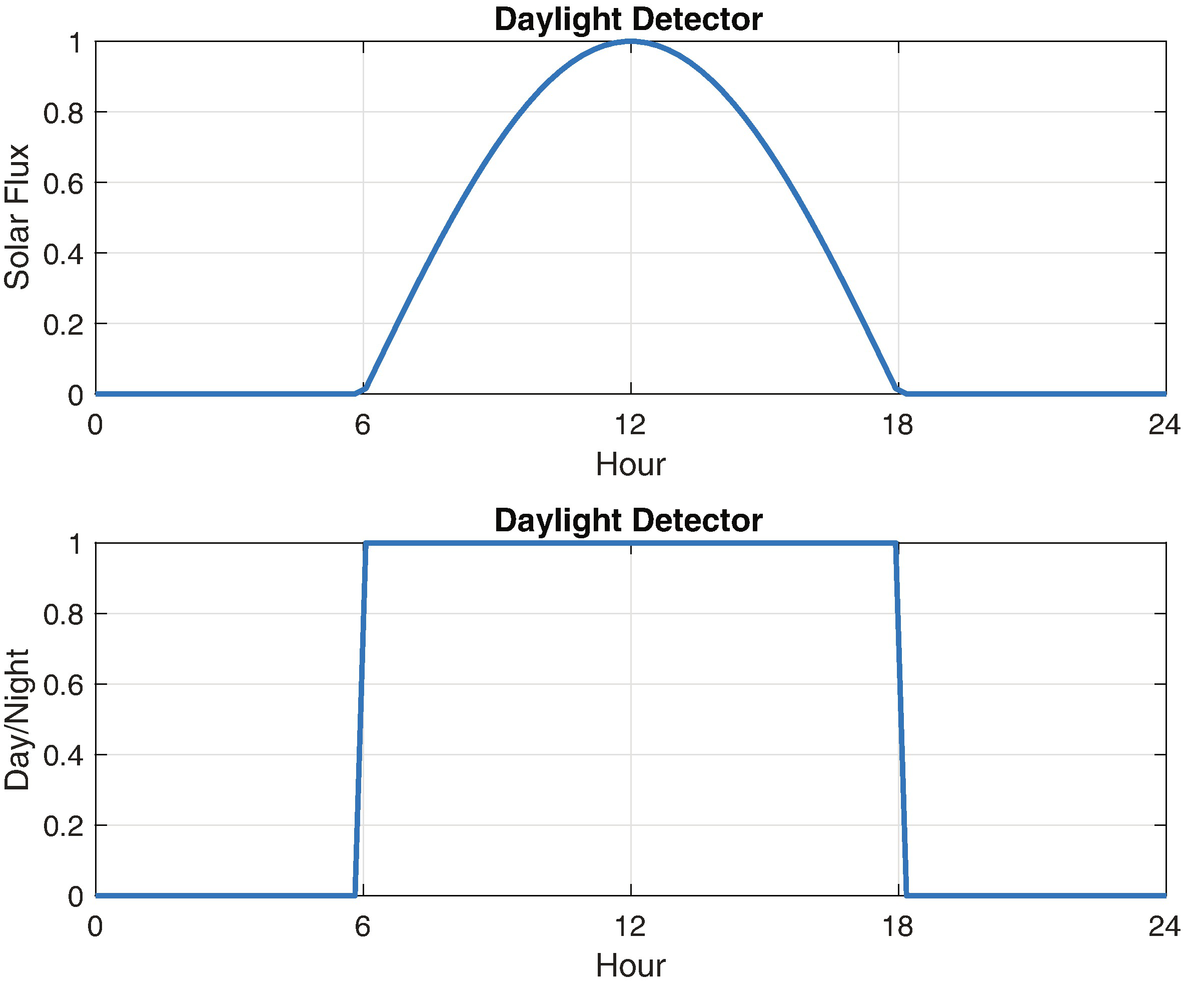

This is shown in the following script, SunnyDay. The script is named after the famous neural net that was supposed to detect tanks, but instead detected sunny days; this was due to all the training photos of tanks being taken, unknowingly, on a sunny day, whereas all the photos without tanks were taken on a cloudy day. The solar flux is modeled using a cosine and scaled so that it is 1 at noon. Any value greater than 0 is daylight.

The daylight detector.

8.2 Modeling a Pendulum

8.2.1 Problem

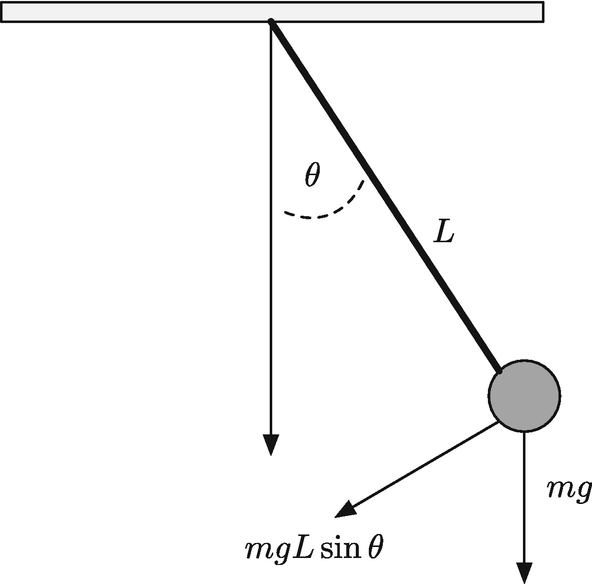

A pendulum. The motion is driven by the acceleration of gravity.

8.2.2 Solution

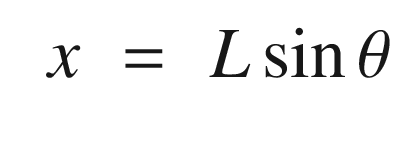

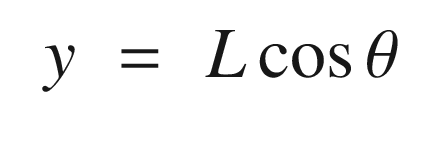

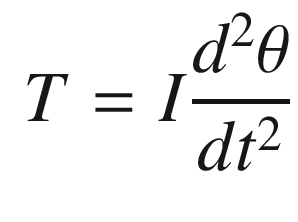

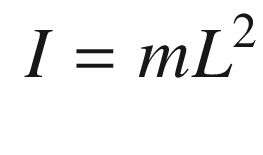

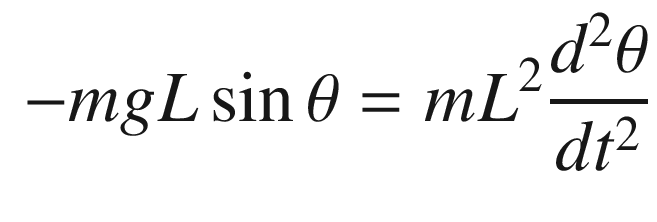

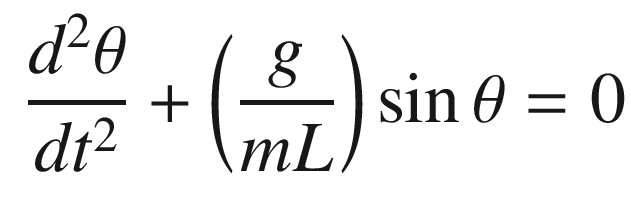

The solution is to write a pendulum dynamics function in MATLAB. The dynamics will be written in torque form, that is, we will model it as rigid body rotation. Rigid body rotation is what happens when you spin a wheel. It will use the RungeKutta integration routine in the General folder of the included toolbox to integrate the equations of motion.

8.2.3 How It Works

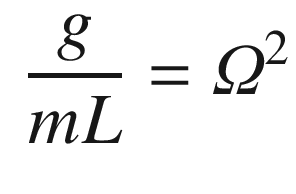

, times the moment arm, in this case L. The torque is therefore:

, times the moment arm, in this case L. The torque is therefore:

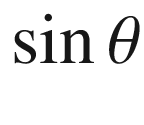

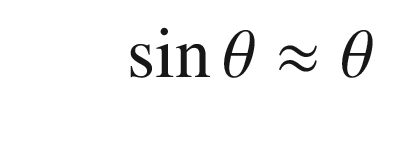

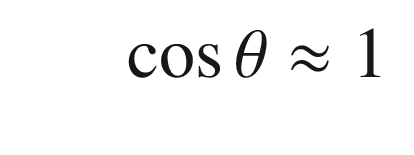

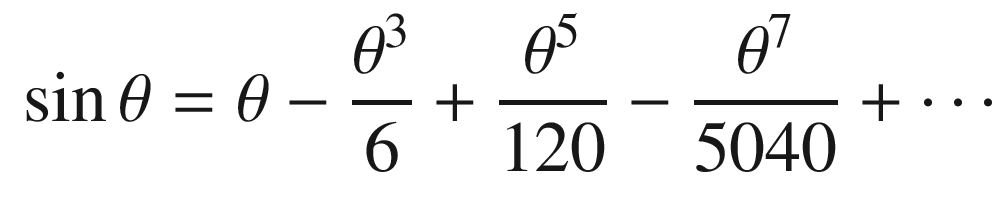

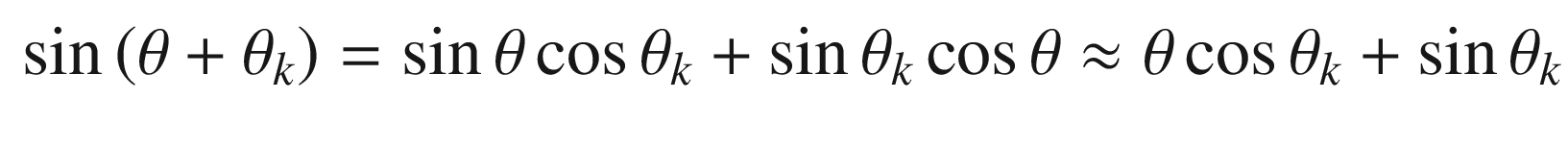

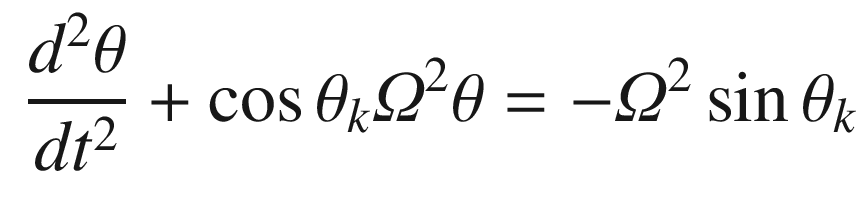

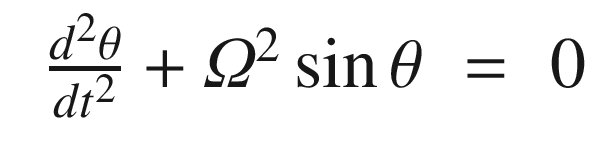

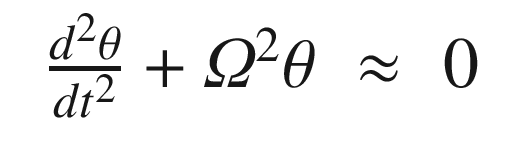

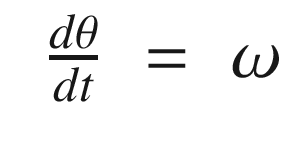

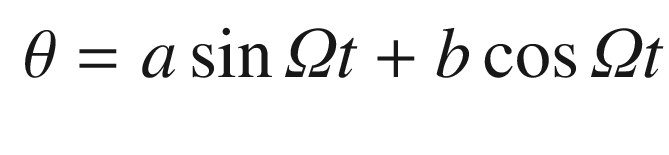

. We can linearize it about small angles, θ, about vertical. For small angles:

. We can linearize it about small angles, θ, about vertical. For small angles:

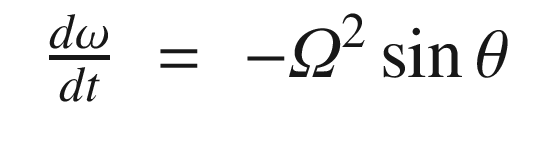

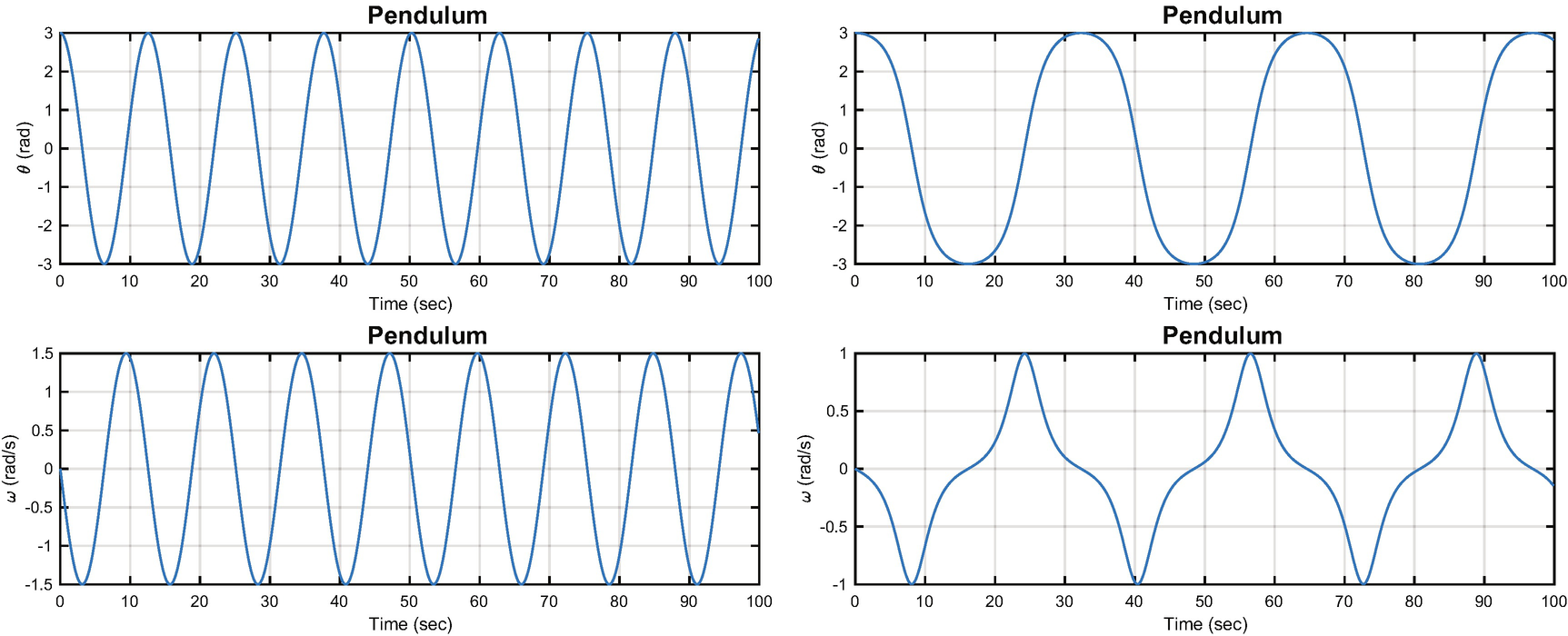

The script PendulumSim, shown below, simulates the pendulum by integrating the dynamical model. Setting the data structure field linear to true gives the linear model. Note that the state is initialized with a large initial angle of 3 radians to highlight the differences between the models.

A pendulum modeled by the linear and nonlinear equations. The period for the nonlinear model is not the same as for the linear model. The left-hand plot is linear and the right nonlinear.

8.3 Single Neuron Angle Estimator

8.3.1 Problem

We want to use a simple neural net to estimate the angle between the rigid pendulum and vertical.

8.3.2 Solution

We will derive the equations for a linear estimator and then replicate it with a neural net consisting of a single neuron.

8.3.3 How It Works

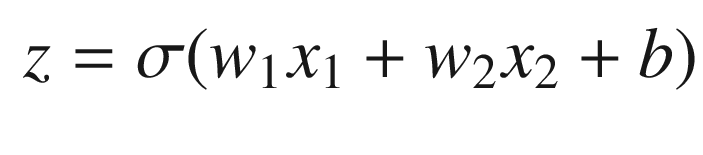

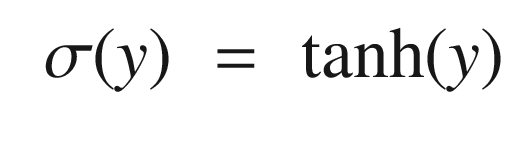

A two input neuron.

A real neuron can have 10,000 inputs!

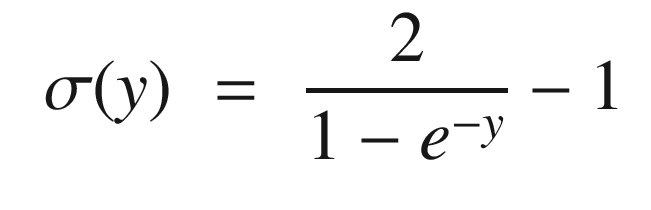

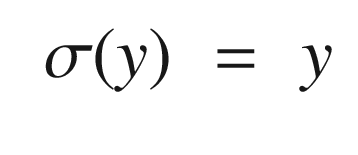

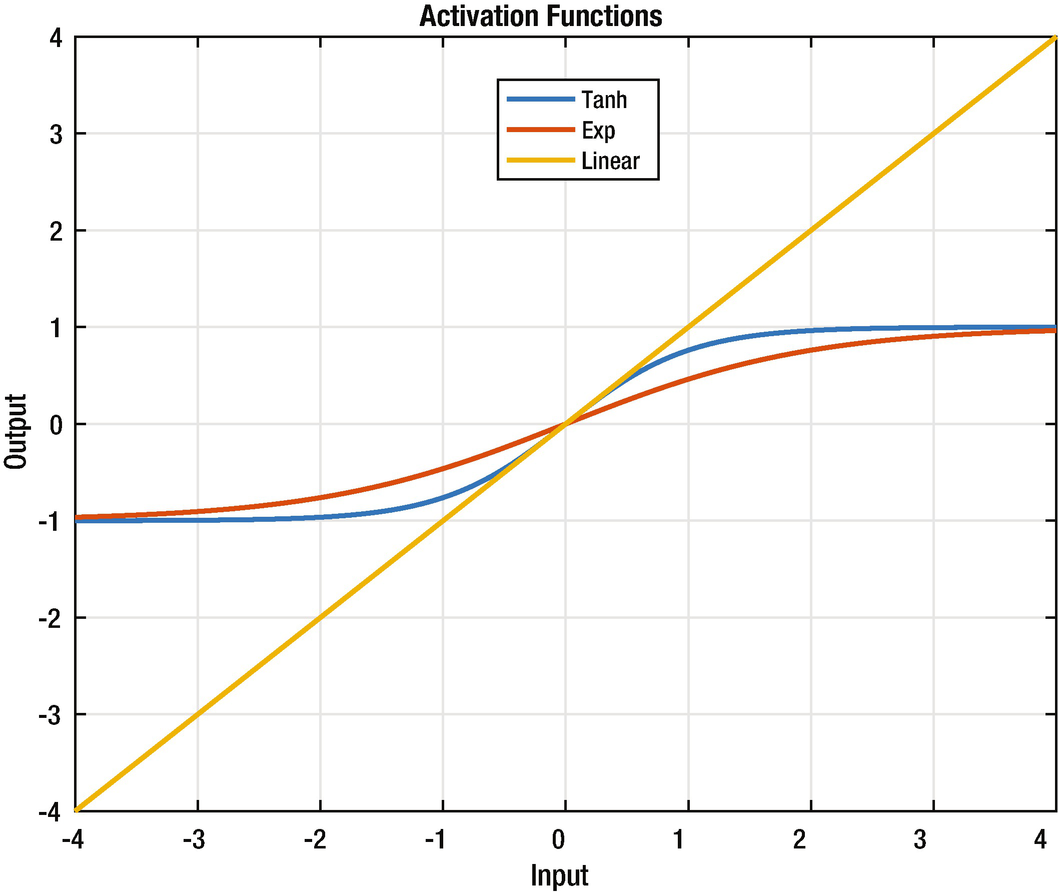

The exponential one is normalized and offset from zero so that it ranges from -1 to 1. The following code in the script OneNeuron computes and plots these three activation functions for an input q.

The three activation functions.

Activation functions that saturate model a biological neuron that has a maximum firing rate. These particular functions also have good numerical properties that are helpful in learning.

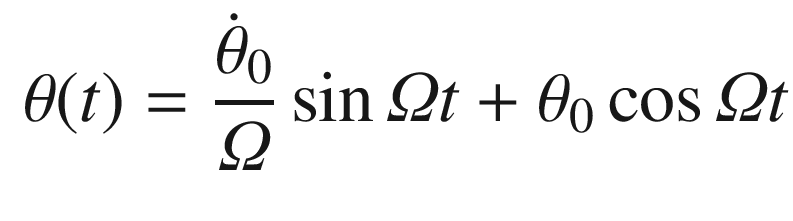

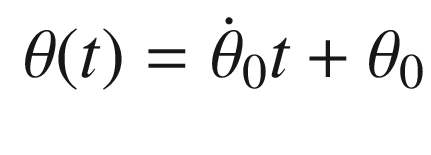

, we get the angle as a function of time:

, we get the angle as a function of time:

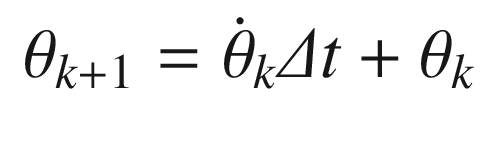

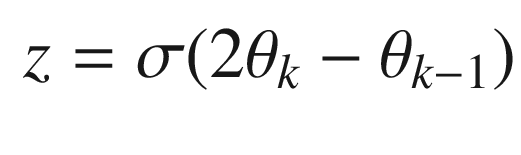

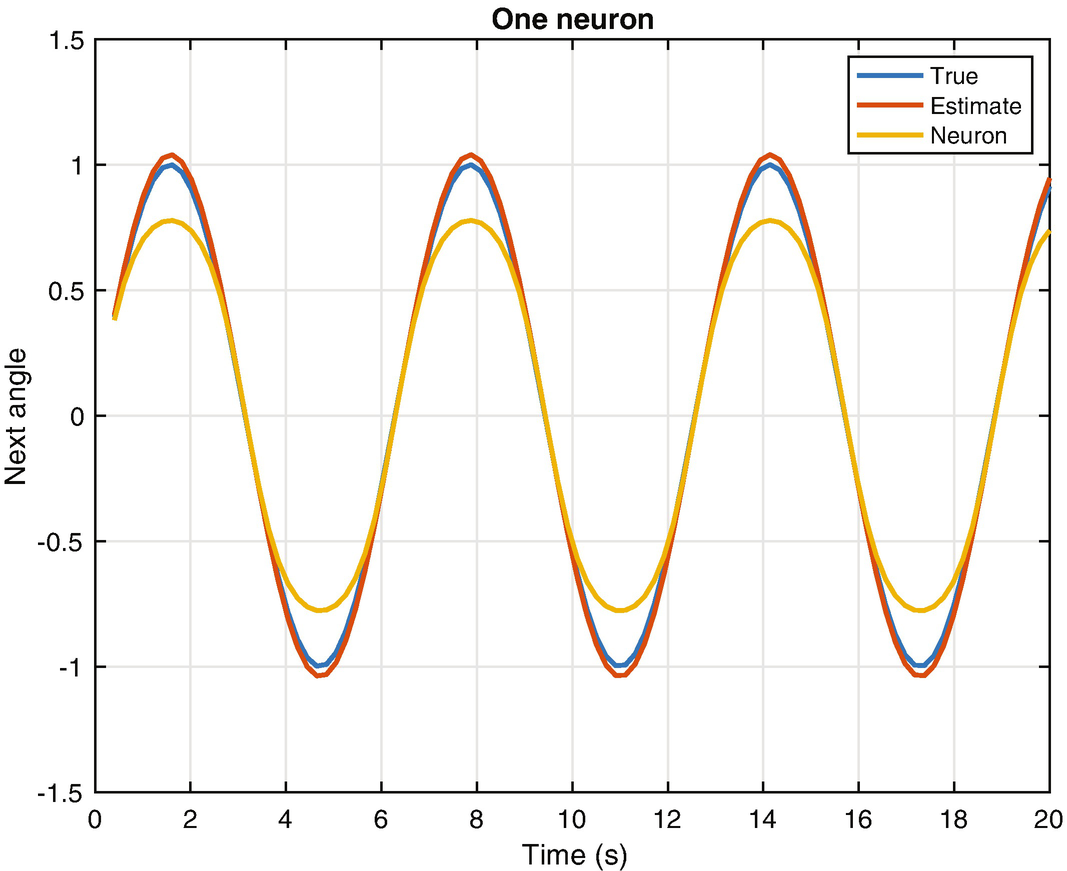

Continuing through OneNeuron, the following code implements the estimators. We input a pure sine wave that is only valid for small pendulum angles. We then compute the neuron with the linear activation function and then the tanh activation function. Note that the variable thetaN is equivalent to using the linear activation function.

The true pendulum dynamics compared with the linear and tanh neuron output.

The one neuron function with the linear activation function is the same as the estimator by itself. Usually output nodes, and this neural net has only an output node, have linear activation functions. This makes sense, otherwise the output would be limited to the saturation value of the activation functions, as we have seen with tanh. With any other activation function, the output does not produce the desired result. This particular example is one in which a neural net doesn’t really give us any advantage and was chosen because it reduces to a simple linear estimator. For more general problems, with more inputs and nonlinear dependencies among the inputs, activation functions that have saturation may be valuable.

For this, we will need a multi-neuron net to be discussed in the last section of the chapter. Note that even the neuron with the linear activation function does not quite match the truth value. If we were to actually use the linear activation function with the nonlinear pendulum, it would not work very well. A nonlinear estimator would be complicated, but a neural net with multiple layers (deep learning) could be trained to cover a wider range of conditions.

8.4 Designing a Neural Net for the Pendulum

8.4.1 Problem

We want to estimate angles for a nonlinear pendulum.

8.4.2 Solution

We will use NeuralNetMLFF to build a neural net from training sets. (MLFF stands for multi-layer, feed-forward). We will run the net using NeuralNetMLFF. The code for NeuralNetMLFF is included with the neural net developer GUI in the next chapter.

8.4.3 How It Works

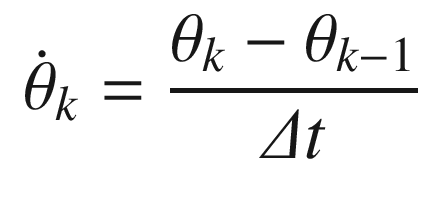

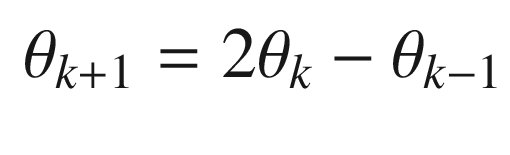

The script for this recipe is NNPendulumDemo. The first part generates the test data running the same simulation as PendulumSim.m in Recipe 8.2. We calculate the period of the pendulum in order to set the simulation time step at a small fraction of the period. Note that we will use tanh as the activation function for the net.

The next block defines the network and trains it using NeuralNetTraining. NeuralNetTraining and NeuralNetMLFF are described in the next chapter. Briefly, we define a first layer with three neurons and a second output layer with a single neuron; the network has two inputs, which are the previous two angles.

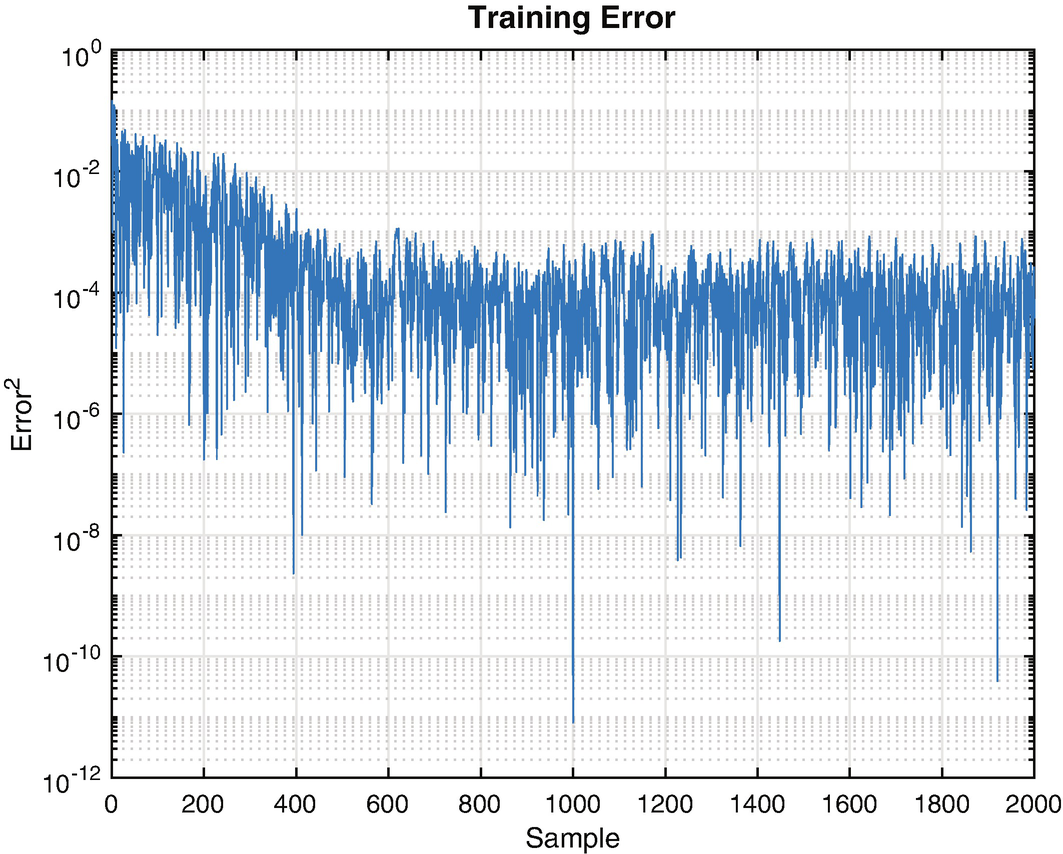

Training error.

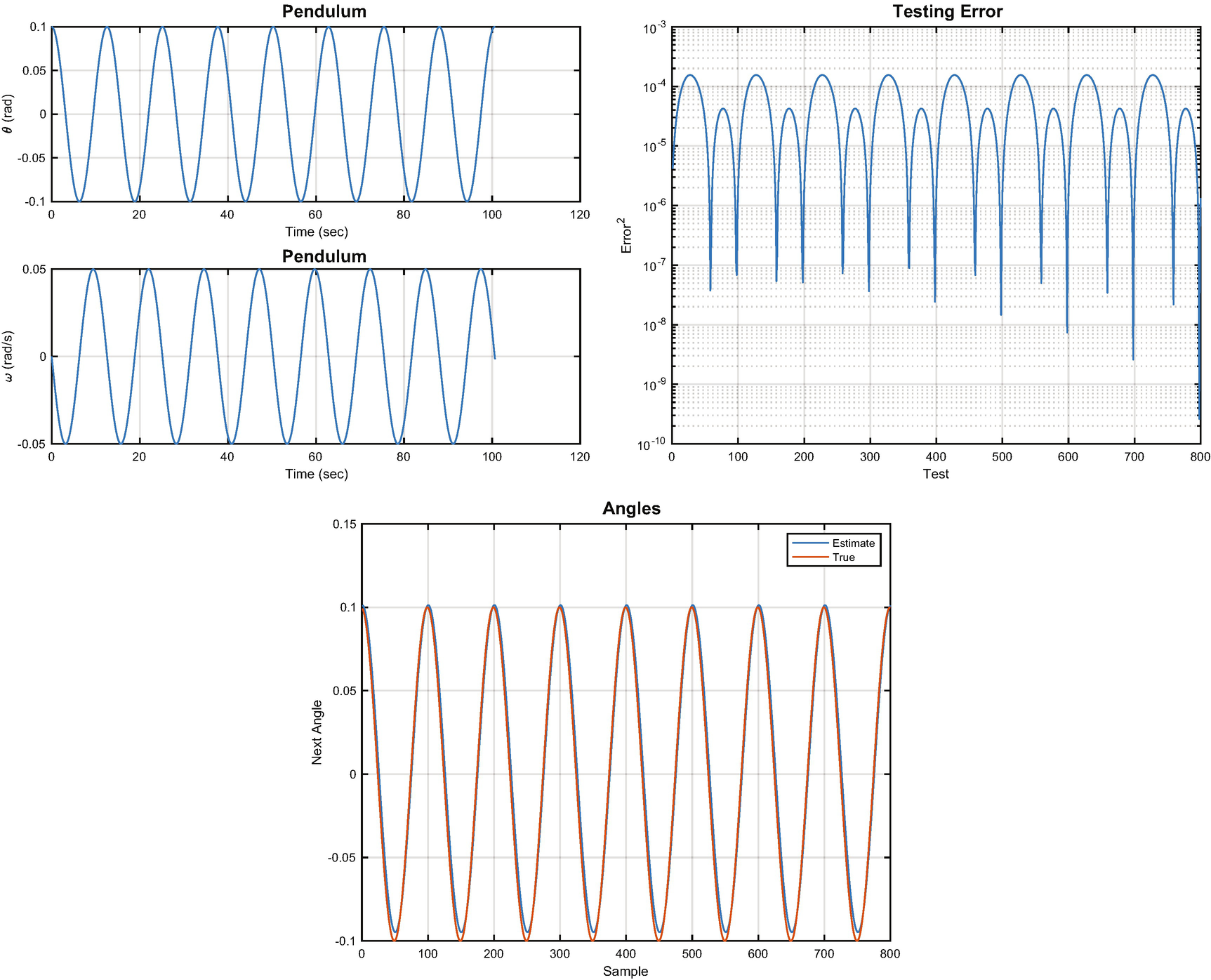

We test the neural net in the last block of code. We rerun the simulation and then run the neural net using NeuralNetMLFF. Note that you may choose to initialize the simulation with a different starting point than in the training data by changing the value of thetaD.

Neural net results: the simulated state, the testing error, and the truth angles compared with the neural net’s estimate.

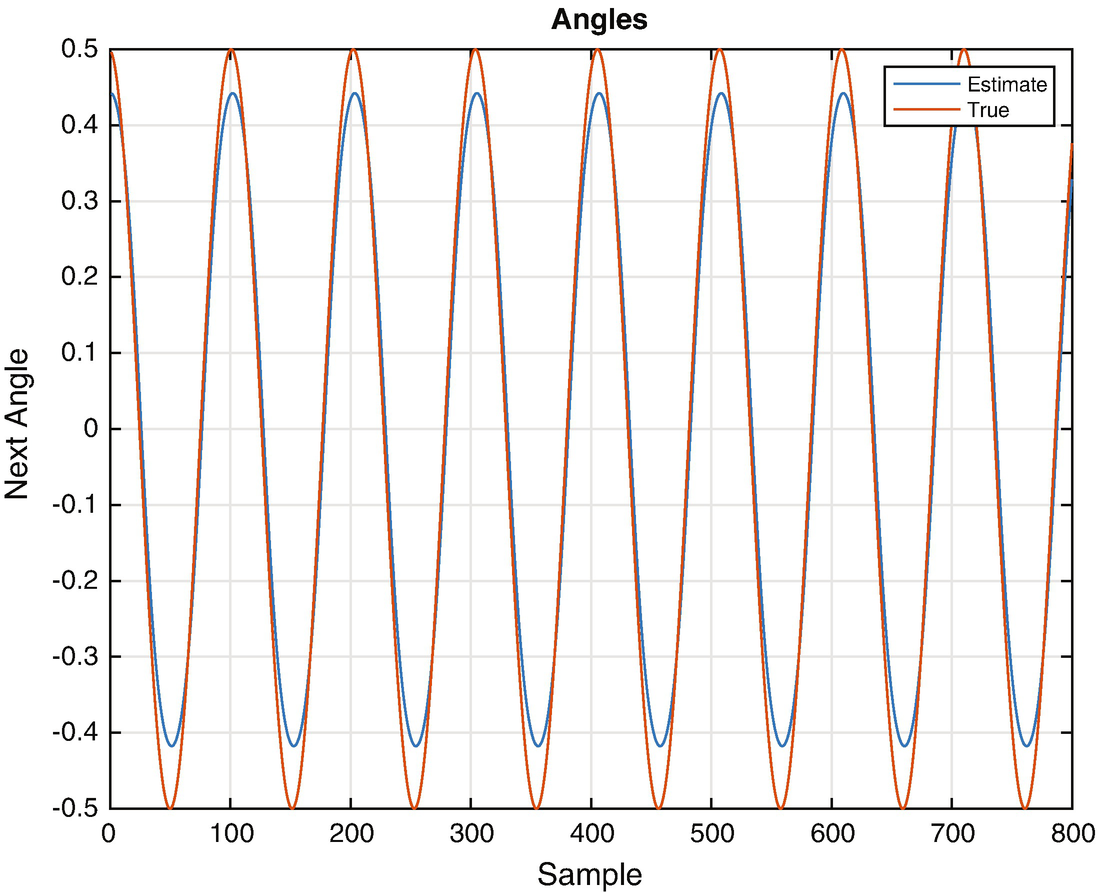

Neural estimated angles for a different magnitude oscillation.

If we want the neural net to predict angles for other magnitudes, it needs to be trained with a diverse set of data that models all conditions. When we trained the network we let it see the same oscillation magnitude several times. This is not really productive. It might also be necessary to add more nodes to the net or more layers to make a more general purpose estimator.

8.5 Summary

Chapter Code Listing

File | Description |

|---|---|

NNPendulumDemo | Train a neural net to track a pendulum. |

OneNeuron | Explore a single neuron. |

PendulumSim | Simulate a pendulum. |

RHSPendulum | Right-hand side of a nonlinear pendulum. |

SunnyDay | Recognize daylight. |

Chapter 9 Functions | |

NeuralNetMLFF | Compute the output of a multi-layer, feed-forward neural net. |

NeuralNetTraining | Training with back propagation. |