Understanding or controlling a physical system often requires a model of the system, that is, knowledge of the characteristics and structure of the system. A model can be a pre-defined structure or can be determined solely through data. In the case of Kalman Filtering, we create a model and use the model as a framework for learning about the system. This is part of the Control branch of our Autonomous Learning taxonomy from Chapter 1.

What is important about Kalman Filters is that they rigorously account for uncertainty in a system that you want to know more about. There is uncertainty in the model of the system, if you have a model, and uncertainty (i.e., noise) in measurements of a system.

A system can be defined by its dynamical states and its parameters, which are nominally constant. For example, if you are studying an object sliding on a table, the states would be the position and velocity. The parameters would be the mass of the object and the friction coefficient. There may also be an external force on the object that we may want to estimate. The parameters and states comprise the model. You need to know both to properly understand the system. Sometimes it is hard to decide if something should be a state or a parameter. Mass is usually a parameter, but in a aircraft, car or rocket where the mass changes as fuel is consumed, it is often modeled as a state.

The Kalman Filters, invented by R. E. Kalman and others, are a mathematical framework for estimating or learning the states of a system. An estimator gives you statistically best estimates of the dynamical states of the system, such as the position and velocity of a moving point mass. Kalman Filters can also be written to identify the parameters of a system. Thus, the Kalman Filter provides a framework for both state and parameter identification.

Another application of Kalman Filters is system identification. System identification is the process of identifying the structure and parameters of any system. For example, with a simple mass on a spring it would be the identification or determination of the mass and spring constant values along with determining the differential equation for modeling the system. It is a form of machine learning that has its origins in control theory. There are many methods of system identification. In this chapter, we will only study the Kalman Filter. The term “learning” is not usually associated with estimation, but it is really the same thing.

4.1 A State Estimator Using a Linear Kalman Filter

4.1.1 Problem

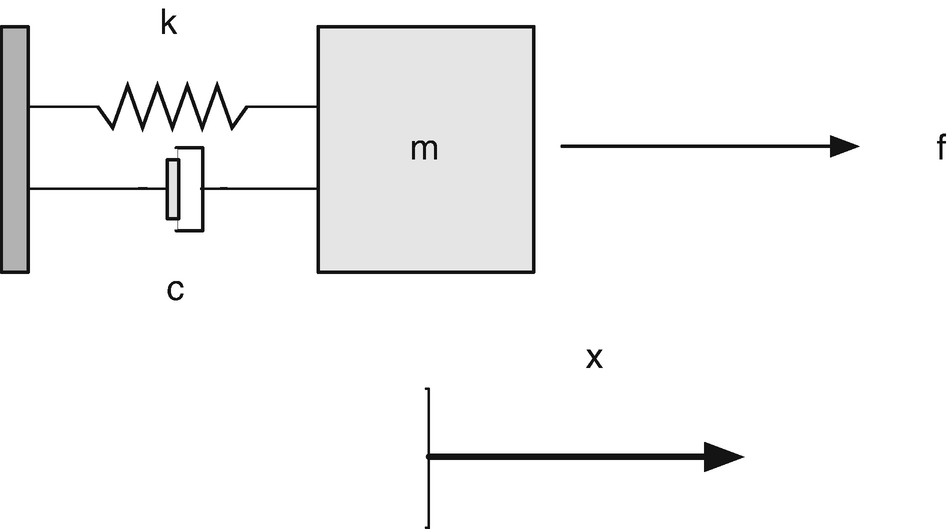

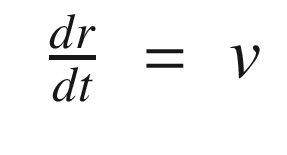

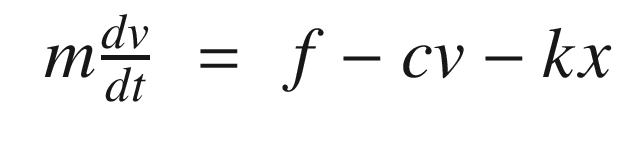

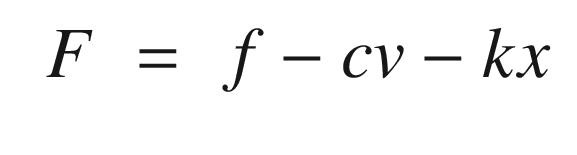

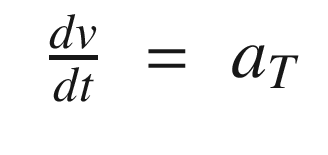

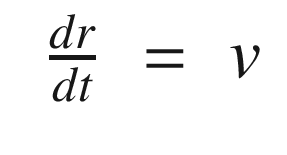

You want to estimate the velocity and position of a mass attached through a spring and damper to a structure. The system is shown in Figure 4.1. m is the mass, k is the spring constant, c is the damping constant, and f is an external force. x is the position. The mass moves in only one direction.

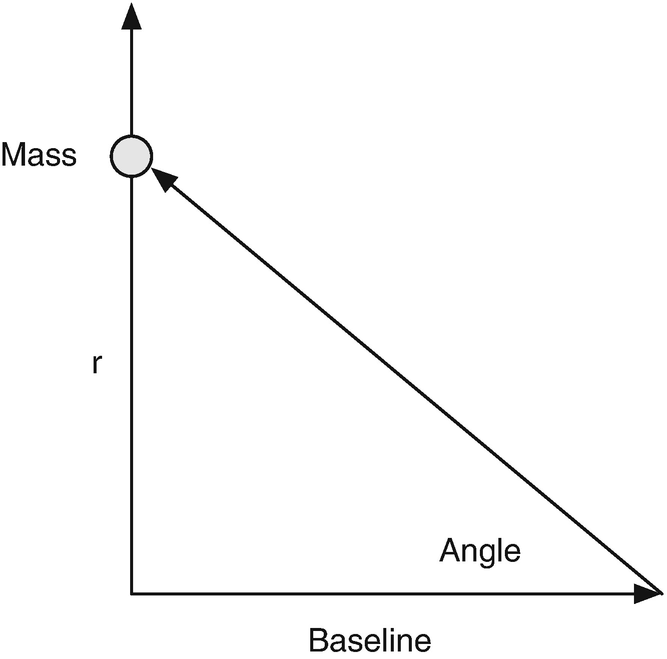

Suppose we had a camera that was located near the mass. The camera would be pointed at the mass during its ascent. This would result in a measurement of the angle between the ground and the boresight of the camera. The angle measurement geometry is shown in Figure 4.2. The angle is measured from an offset baseline.

Spring-mass-damper system. The mass is on the right. The spring is on the top to the left of the mass. The damper is below.

The angle measurement geometry.

4.1.2 Solution

First, we will need to define a mathematical model for the mass system and code it up. Then we will derive the Kalman Filter from first principles, using Bayes theorem. Finally, we present code implementing the Kalman Filter estimator for the spring-mass problem.

4.1.3 How It Works

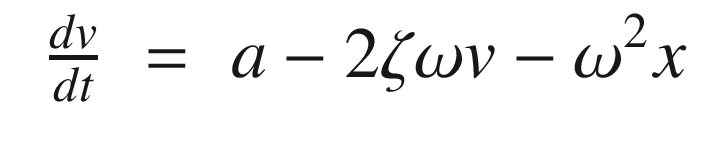

Spring-Mass System Model

, ζ is the damping ratio, and ω is the undamped natural frequency. The undamped natural frequency is the frequency at which the mass would oscillate if there were no damping. The damping ratio indicates how fast the system damps and what level of oscillations we observe. With a damping ratio of zero, the system never damps and the mass oscillates forever. With a damping ratio of one you don’t see any oscillation. This form makes it easier to understand what damping and oscillation to expect. You immediately know the frequency and the rate at which the oscillation should subside. m, c, and k, although they embody the same information, don’t make this as obvious.

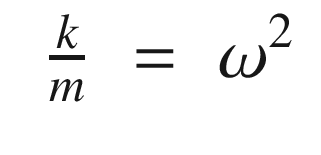

, ζ is the damping ratio, and ω is the undamped natural frequency. The undamped natural frequency is the frequency at which the mass would oscillate if there were no damping. The damping ratio indicates how fast the system damps and what level of oscillations we observe. With a damping ratio of zero, the system never damps and the mass oscillates forever. With a damping ratio of one you don’t see any oscillation. This form makes it easier to understand what damping and oscillation to expect. You immediately know the frequency and the rate at which the oscillation should subside. m, c, and k, although they embody the same information, don’t make this as obvious.The following shows a simulation of the oscillator with damping (OscillatorDamping RatioSim). It shows different damping ratios. The loop that runs the simulation with different damping ratios is shown.

Spring-mass-damper system simulation with different damping ratios zeta.

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} x = \left[ \begin{array}{r} r\\ v \end{array} \right] \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ11.png)

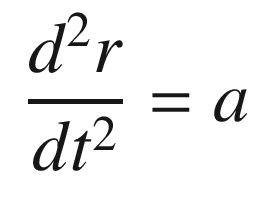

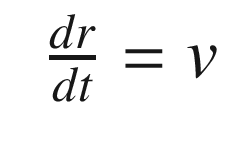

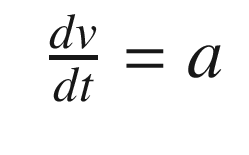

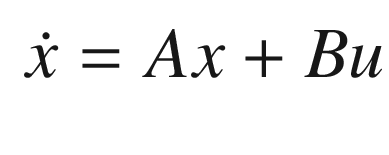

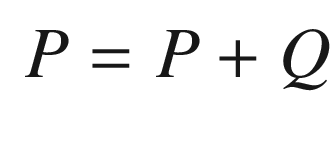

All of our filter derivations work with dynamical equations in state space form. Also, most numerical integration schemes are designed for sets of first-order differential equations.

The right-hand side for the state equations (first-order differential equations), RHSOscillator, is shown in the following listing. Notice that if no inputs are requested, it returns the default data structure. The code, if ( nargin <1), tells the function to return the data structure if no inputs are given. This is a convenient way of making your functions self-documenting and keeping your data structures consistent. The actual working code is just one line.

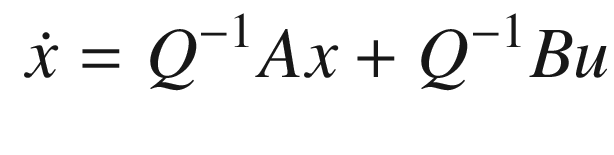

The following listing gives the simulation script OscillatorSim. It causes the right-hand side, RHSOscillator, to be numerically integrated using the RungeKutta function. We start by getting the default data structure from the right-hand side. We fill it in with our desired parameters. Measurements y are created for each step, including random noise. There are two measurements: position and angle.

The following code shows just the simulation loop of OscillatorSim. The angle measurement is just trigonometry. The first measurement line computes the angle, which is a nonlinear measurement. The second measures the vertical distance, which is linear.

Spring-mass-damper system simulation. The input is a step acceleration. The oscillation slowly damps out, that is, it goes to zero over time. The position r develops an offset due to the constant acceleration.

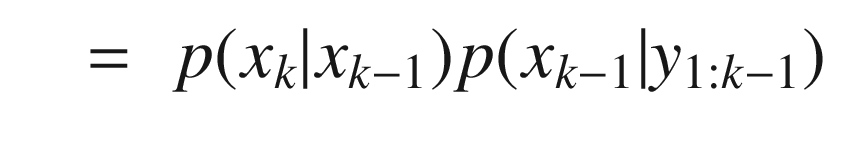

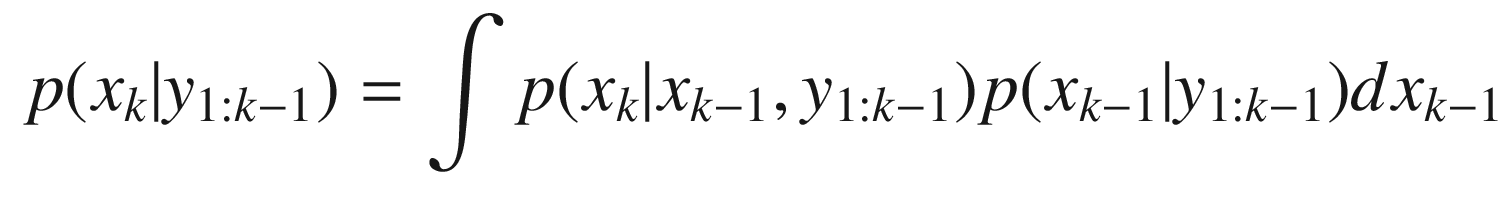

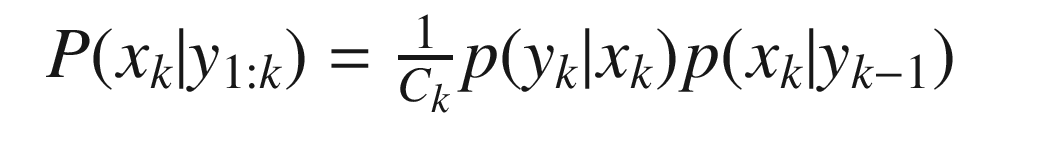

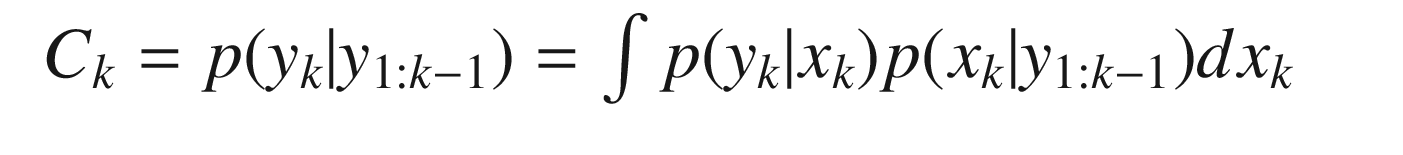

Kalman Filter Derivation

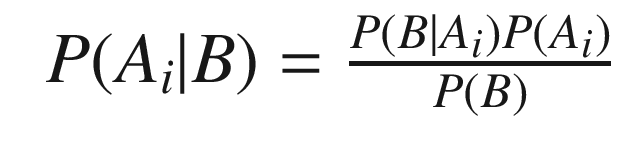

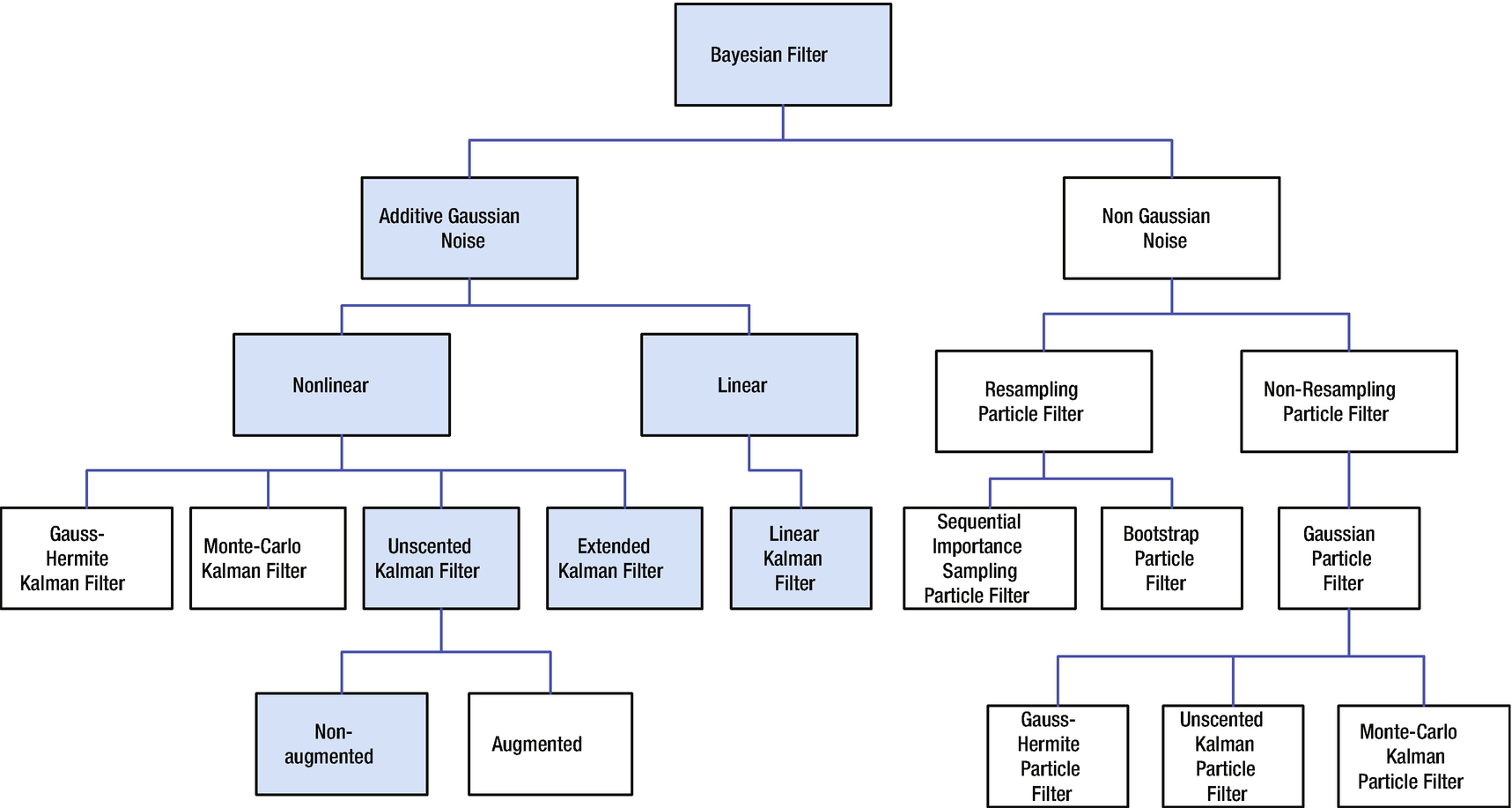

Figure 4.5 shows the Kalman Filter family and how it relates to the Bayesian Filter. In this book we are covering only the ones in the colored boxes. The complete derivation of the Kalman Filter is given below; this provides a coherent framework for all Kalman filtering implementations. The different filters fall out of the Bayesian models based on assumptions about the model and sensor noise and the linearity or nonlinearity of the measurement and dynamics models. Let’s look at the branch that is colored blue. Additive Gaussian noise filters can be linear or nonlinear depending on the type of dynamical and measurement models. In many cases you can take a nonlinear system and linearize it about the normal operating conditions. You can then use a linear Kalman Filter. For example, a spacecraft dynamical model is nonlinear and an Earth sensor that measures the Earth’s chord width for roll and pitch information is nonlinear. However, if we are only concerned with Earth pointing, and small deviations from nominal pointing, we can linearize both the dynamical equations and the measurement equations and use a linear Kalman Filter.

If nonlinearities are important, we have to use a nonlinear filter. The Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) uses partial derivatives of the measurement and dynamical equations. These are computed each time step or with each measurement input. In effect, we are linearizing the system each step and using the linear equations. We don’t have to do a linear state propagation, that is, propagating the dynamical equations, and could propagate them using numerical integration. If we can get analytical derivatives of the measurement and dynamical equations, this is a reasonable approach. If there are singularities in any of the equations, this may not work.

The Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) uses the nonlinear equations directly. There are two forms, augmented and non-augmented. In the former, we created an augmented state vector that includes both the states and the state and measurement noise variables. This may result in better results at the expense of more computation.

The Kalman Filter family tree. All are derived from a Bayesian filter. This chapter covers those in colored boxes.

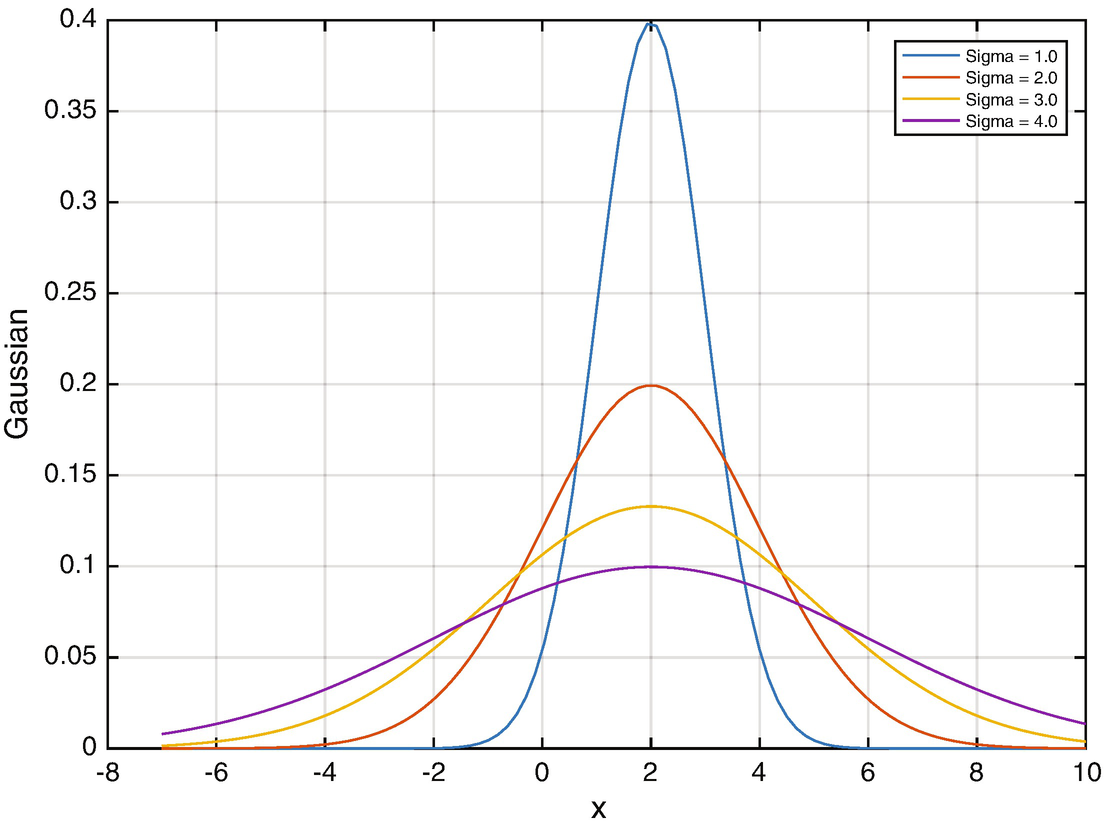

Our derivation will use the notation N(μ, σ 2) to represent a normal variable. A normal variable is another word for a Gaussian variable. Gaussian means it is distributed as the normal distribution with mean μ (average) and variance σ 2. The following code from Gaussian computes a Gaussian or Normal distribution around a mean of 2 for a range of standard deviations. Figure 4.6 shows a plot. The height of the plot indicates how likely a given measurement of the variable is to have that value.

Normal or Gaussian random variable about a mean of 2.

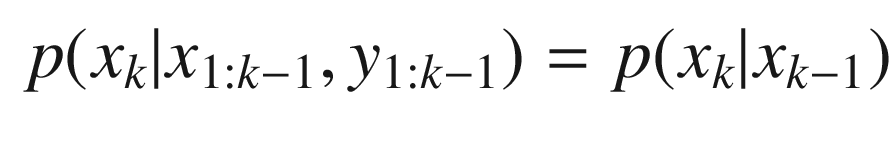

The prior distribution p(x 0), where x 0 is the state prior to the first measurement,

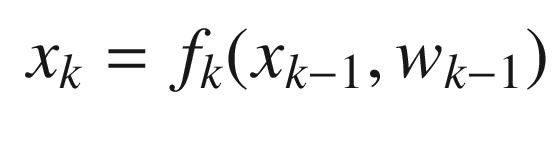

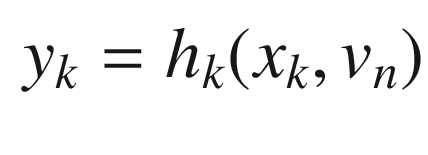

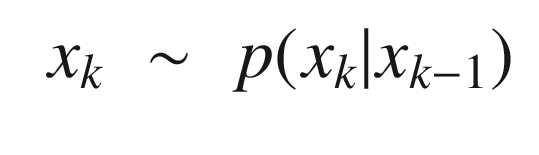

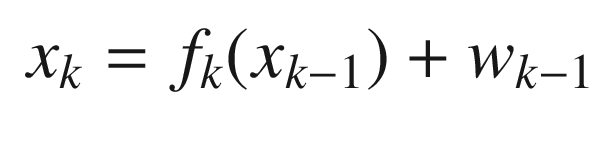

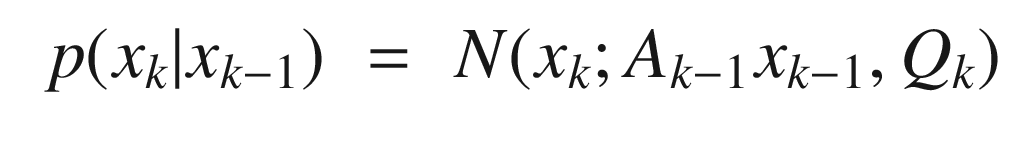

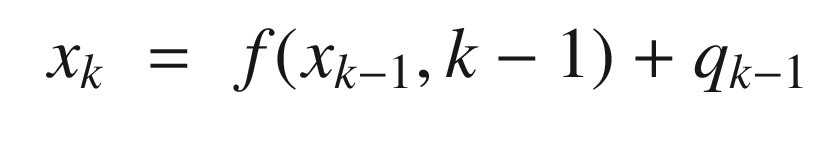

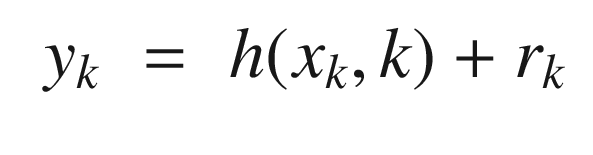

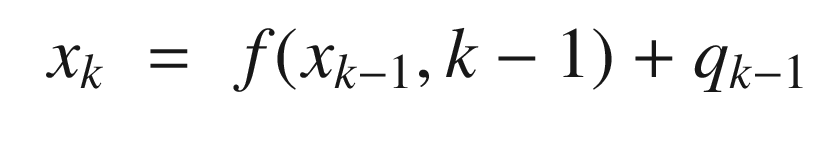

- The state space model

(4.24)

(4.24) (4.25)

(4.25) The measurement sequence y 1:k = y 1, …, yk.

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} E[x_k] = \int x_k p(x_k|y_{1:k-1}) dx_k &\displaystyle &\displaystyle \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ37.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} E[x_kx_k^T] = \int x_kx_k^T p(x_k|y_{1:k-1}) dx_k&\displaystyle &\displaystyle \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ38.png)

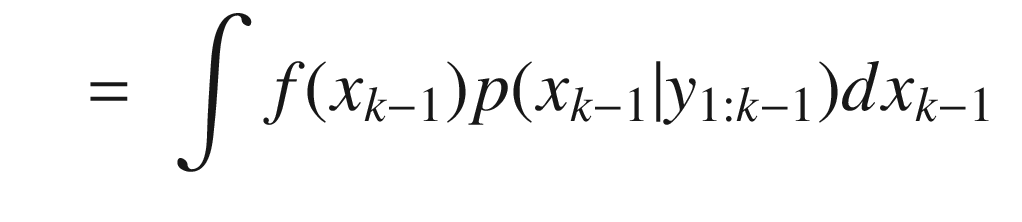

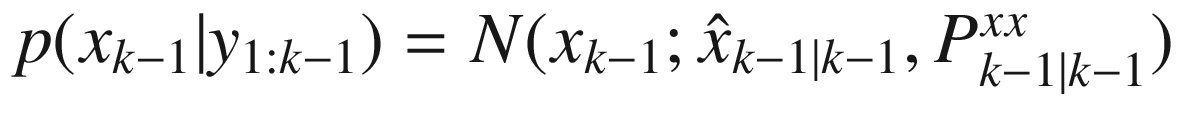

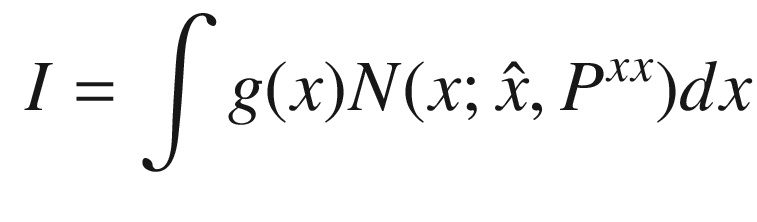

![$$E[x_kx_k^T] $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_IEq3.png) is the covariance. Expanding the first moment and using the identity

is the covariance. Expanding the first moment and using the identity ![$$E[x] = \int x {N}(x;f(s),\varSigma )dx = f(s)$$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_IEq4.png) where s is any argument.

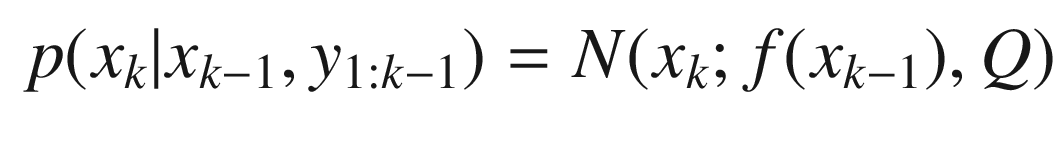

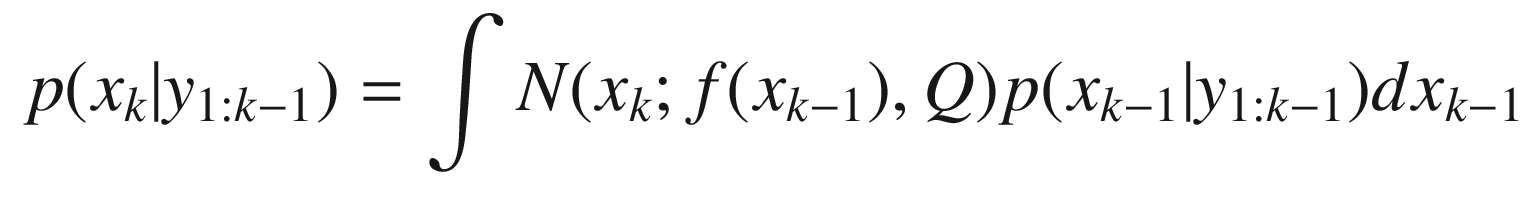

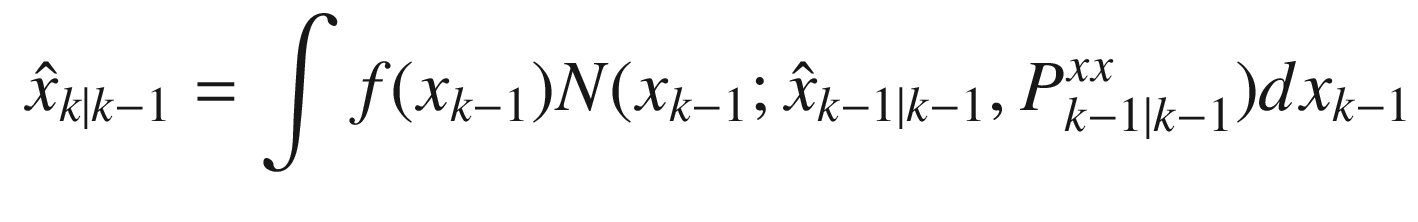

where s is any argument. ![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} E[x_k] &\displaystyle =&\displaystyle \int x_k\left[ \int \mathrm{d} (x_k; f (x_{k-1}) , Q) p(x_{k-1}|y_{1:k-1})dx_{k-1} \right]dx_k \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ39.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} &\displaystyle =&\displaystyle \int x_k\left[ \int {N}(x_k; f (x_{k-1}) , Q) dx_k\right]p(x_{k-1}|y_{1:k-1})dx_{k-1} \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ40.png)

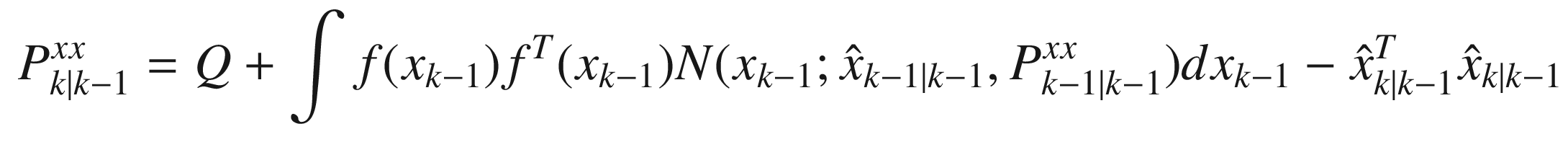

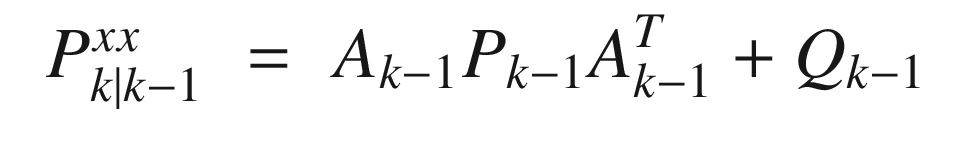

where Pxx is the covariance of x and noting that xk = fk(xk−1) + wk−1 we get:

where Pxx is the covariance of x and noting that xk = fk(xk−1) + wk−1 we get:

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} E[x_kx_k^T] &\displaystyle =&\displaystyle \int x_kx_k^T p(x_k|y_{1:k-1}) dx_k \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ43.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} &\displaystyle =&\displaystyle \int \left[ \int {N}(x_k; f (x_{k-1}) , Q) x_kx_k^Tdx_k\right]p(x_{k-1}|y_{1:k-1})dx_{k-1} \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ44.png)

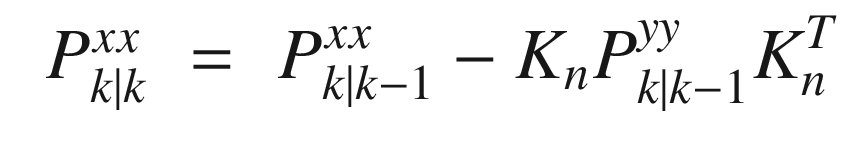

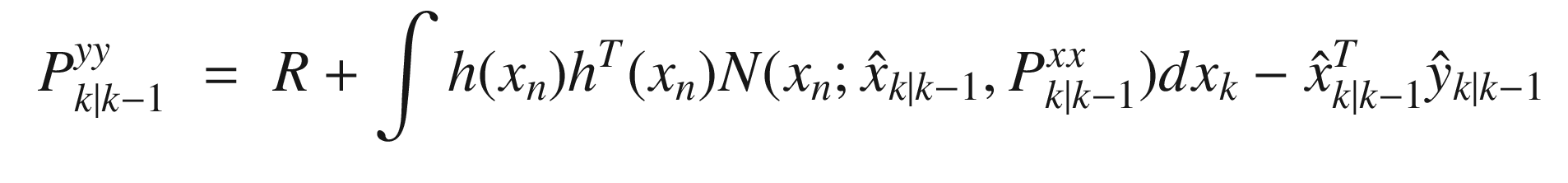

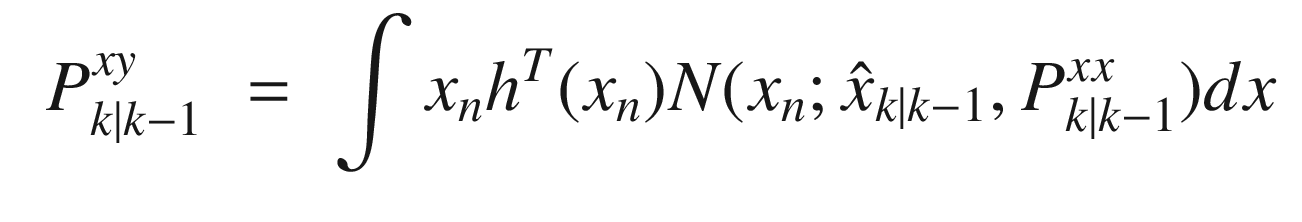

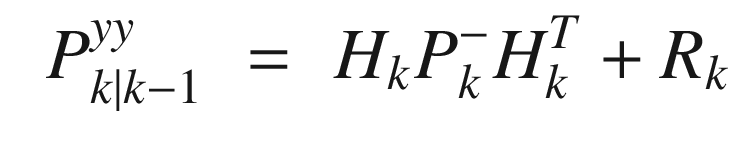

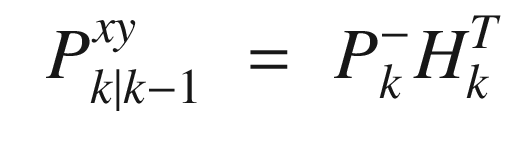

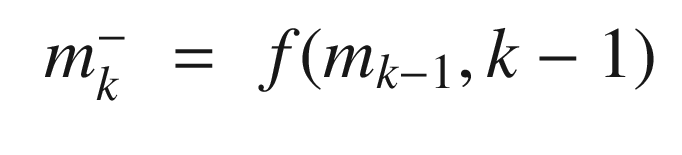

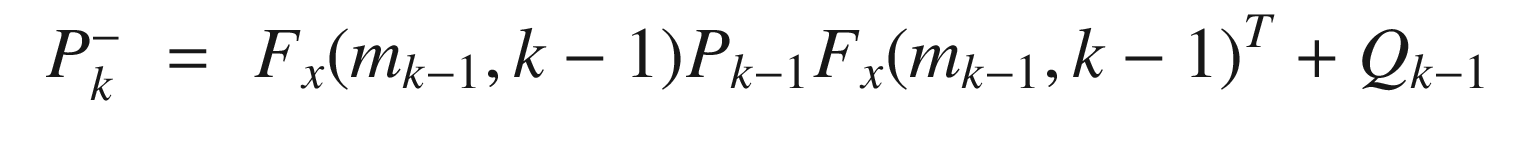

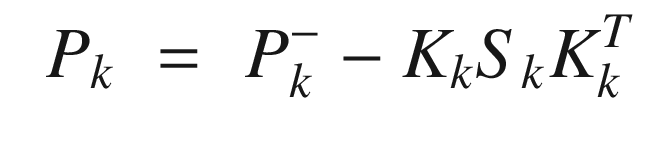

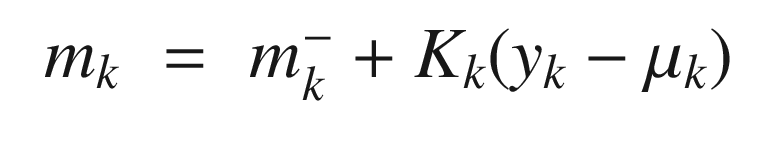

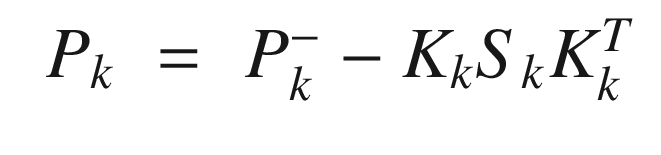

. The Kalman Filter can be written without further approximations as

. The Kalman Filter can be written without further approximations as ![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} \hat{x}_{k|k} &\displaystyle =&\displaystyle \hat{x}_{k|k-1} + K_n\left[y_k - \hat{y}_{k|k-1}\right] \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ46.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} K_n &\displaystyle =&\displaystyle P^{xy}_{k|k-1}\left[ P^{yy}_{k|k-1}\right]^{-1} \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ48.png)

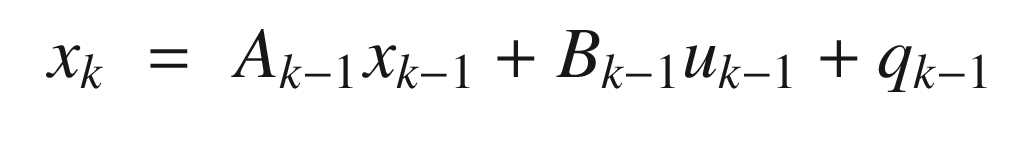

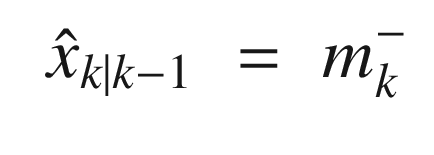

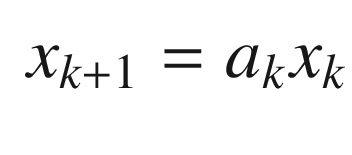

is the state of system at time k

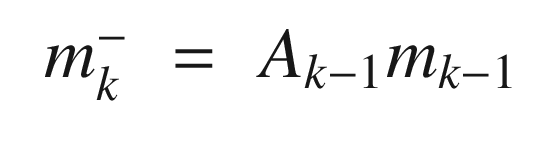

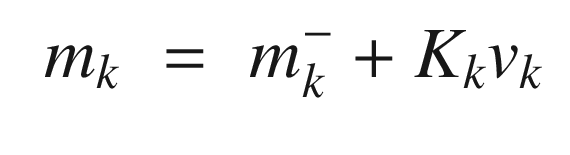

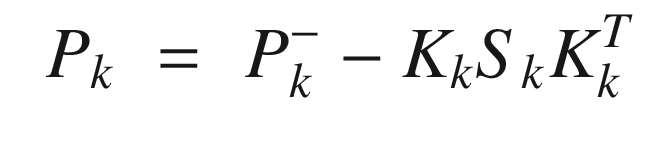

is the state of system at time kmk is the mean state at time k

Ak−1 is the state transition matrix at time k − 1

Bk − 1 is the input matrix at time k − 1

uk − 1 is the input at time k − 1

qk−1, N(0, Qk), is the Gaussian process noise at time k − 1

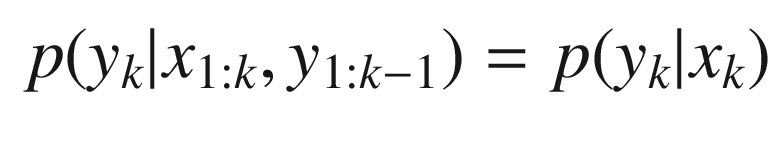

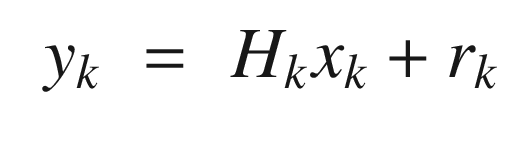

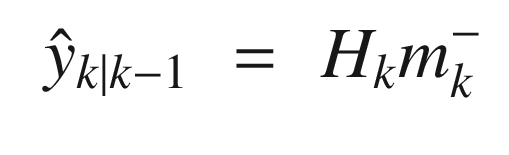

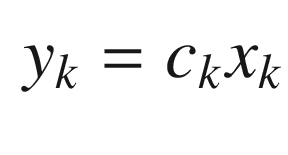

is the measurement at time k

is the measurement at time kHk is the measurement matrix at time k. This is found from the Jacobian (derivatives) of h(x).

rk = N(0, Rk), is the Gaussian measurement noise at time k

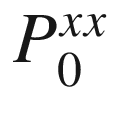

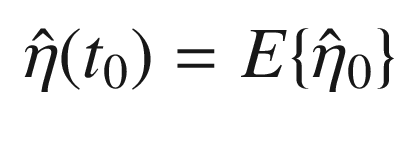

The prior distribution of the state is x 0 = N(m 0, P 0) where parameters m 0 and P 0 contain all prior knowledge about the system. m 0 is the mean at time zero and P 0 is the covariance. Since our state is Gaussian, this completely describes the state.

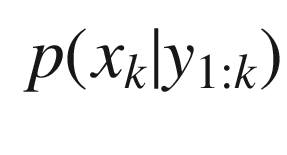

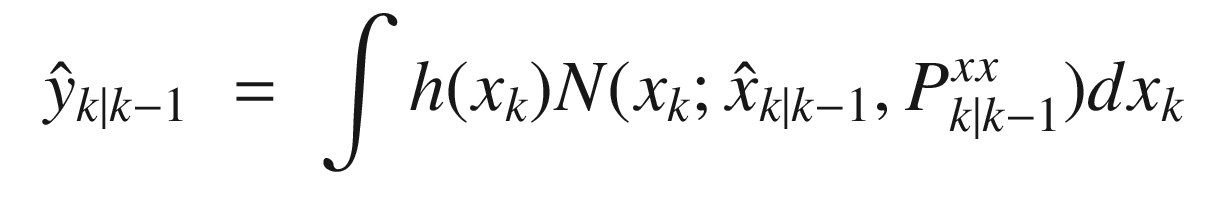

is the mean of x at k given

is the mean of x at k given  at k − 1

at k − 1 is the mean of y at k given

is the mean of y at k given  at k − 1

at k − 1

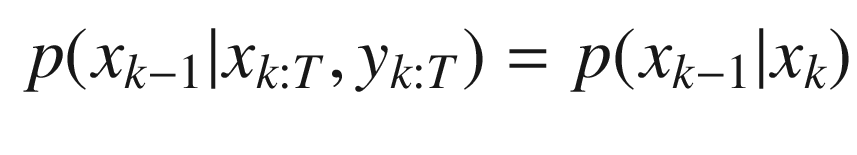

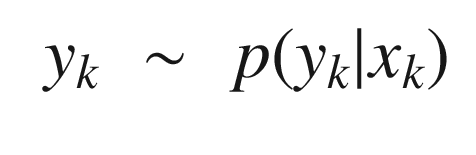

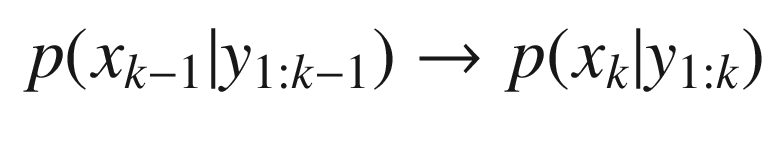

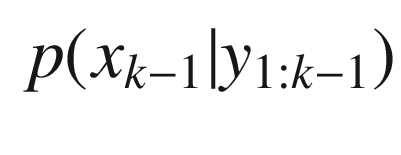

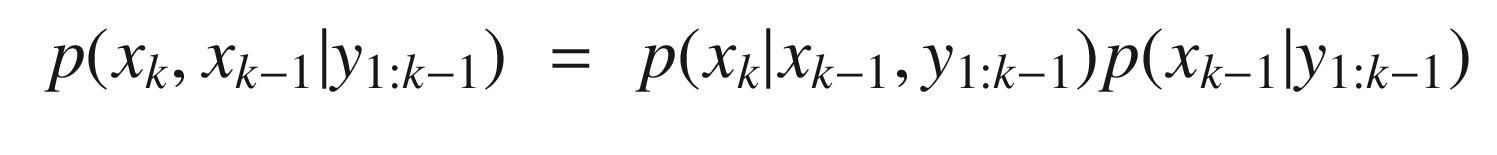

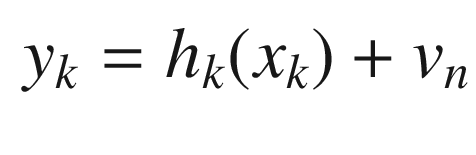

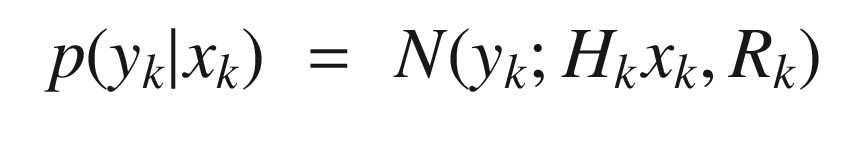

means real numbers in a vector of order n, that is, the state has n quantities. In probabilistic terms the model is:

means real numbers in a vector of order n, that is, the state has n quantities. In probabilistic terms the model is:

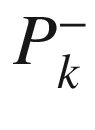

means the covariance prior to the measurement update.

means the covariance prior to the measurement update.

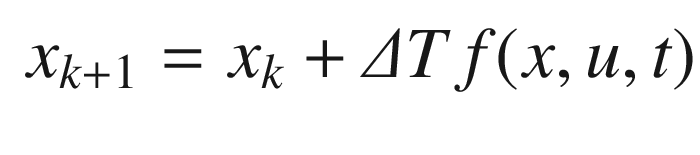

Kalman Filter Implementation

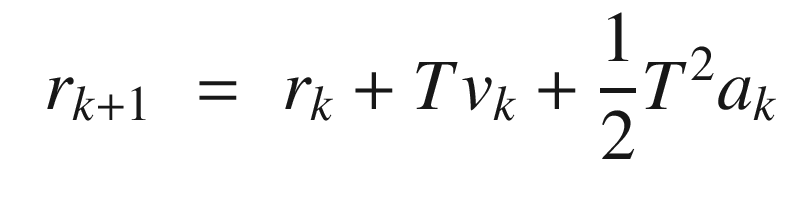

Now we will implement a Kalman Filter estimator for the mass-spring oscillator. First, we need a method of converting the continuous time problem to discrete time. We only need to know the states at discrete times or at fixed intervals, T. We use the continuous to discrete transform, which uses the MATLAB expm function, which performs the matrix exponential. This transform is coded in CToDZOH, the body of which is shown in the following listing. T is the sampling period.

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} x &=& \left[ \begin{array}{l} r \\ v \end{array} \right] \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ73.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} u &=& \left[ \begin{array}{l} 0 \\ a \end{array} \right] \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ74.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} A &=& \left[ \begin{array}{ll} 0 & 1\\ 0 & 0 \end{array} \right] \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ75.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} B &=& \left[ \begin{array}{l} 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ76.png)

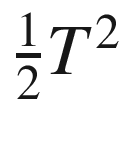

to get the contribution to the position. This is just the standard solution to a particle under constant acceleration.

to get the contribution to the position. This is just the standard solution to a particle under constant acceleration.

The script for testing the Kalman Filter is KFSim.m. KFInitialize is used to initialize the filter (a Kalman Filter, ’kf’, in this case). This function has been written to handle multiple types of Kalman Filters and we will use it again in the recipes for EKF and UKF (’ekf’ and ’ukf’ respectively). We show it below. This function uses dynamic field names to assign the input values to each field.

The simulation starts by assigning values to all of the variables used in the simulation. We get the data structure from the function RHSOscillator and then modify its values. We write the continuous time model in matrix form and then convert it to discrete time. Note that the measurement equation matrix that multiples the state, h, is [1 0], indicating that we are measuring the position of the mass. MATLAB’s randn random number function is used to add Gaussian noise to the simulation. The rest of the script is the simulation loop with plotting afterward.

The first part of the script creates continuous time state space matrices and converts them to discrete time using CToDZOH. You then use KFInitialize to initialize the Kalman Filter.

The simulation loop cycles through measurements of the state and the Kalman Filter update and prediction state with the code KFPredict and KFUpdate. The integrator is between the two to get the phasing of the update and prediction correct. You have to be careful to put the predict and update steps in the right places in the script so that the estimator is synchronized with simulation time.

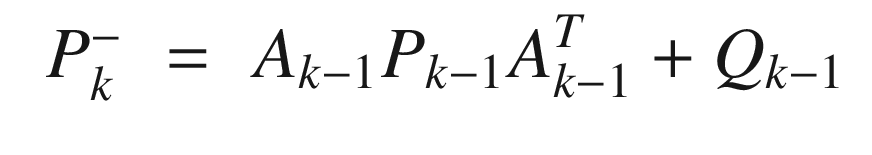

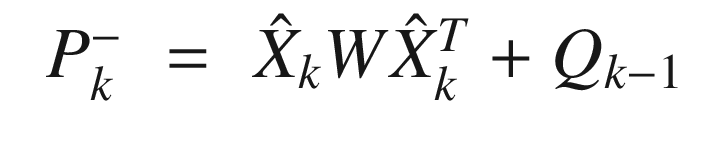

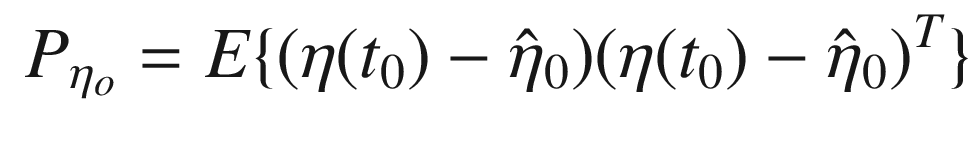

The prediction Kalman Filter step, KFPredict, is shown in the following listing with an abbreviated header. The prediction propagates the state one time step and propagates the covariance matrix with it. It is saying that when we propagate the state, there is uncertainty, so we must add that to the covariance matrix.

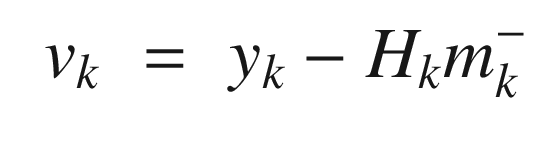

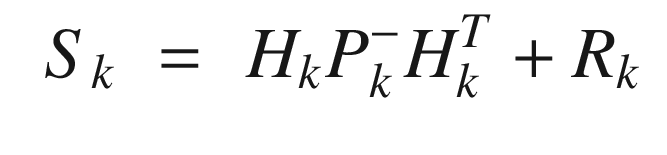

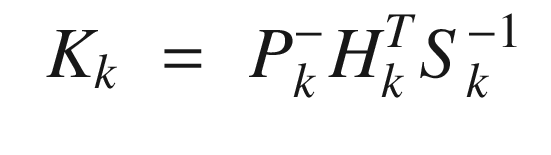

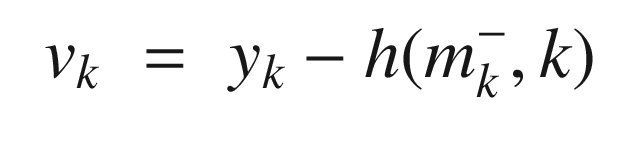

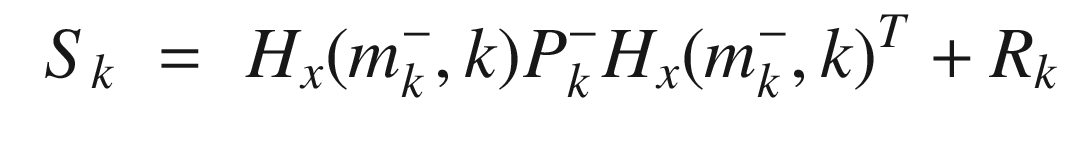

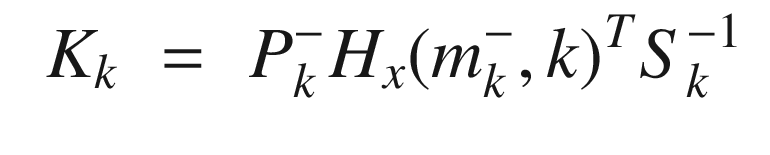

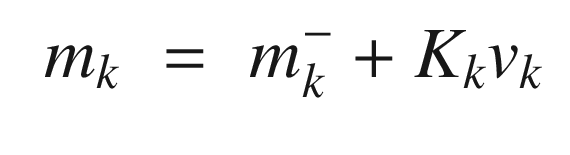

The update Kalman Filter step, KFUpdate, is shown in the following listing. This adds the measurements to the estimate and accounts for the uncertainty (noise) in the measurements.

You will note that the “memory” of the filter is stored in the data structure d. No persistent data storage is used. This makes it easier to use these functions in multiple places in your code. Note also that you don’t have to call KFUpdate every time step. You need only call it when you have new data. However, the filter does assume uniform time steps.

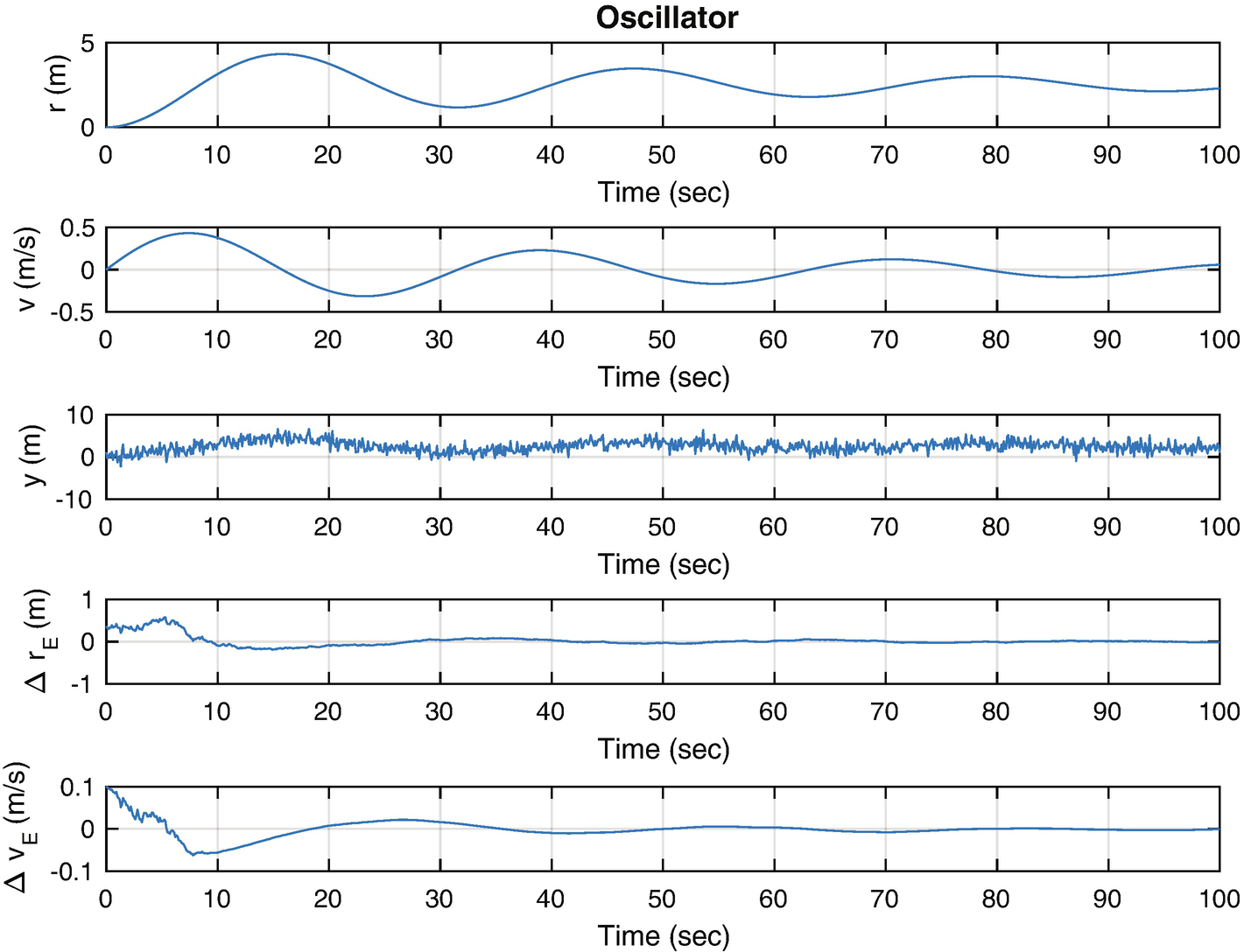

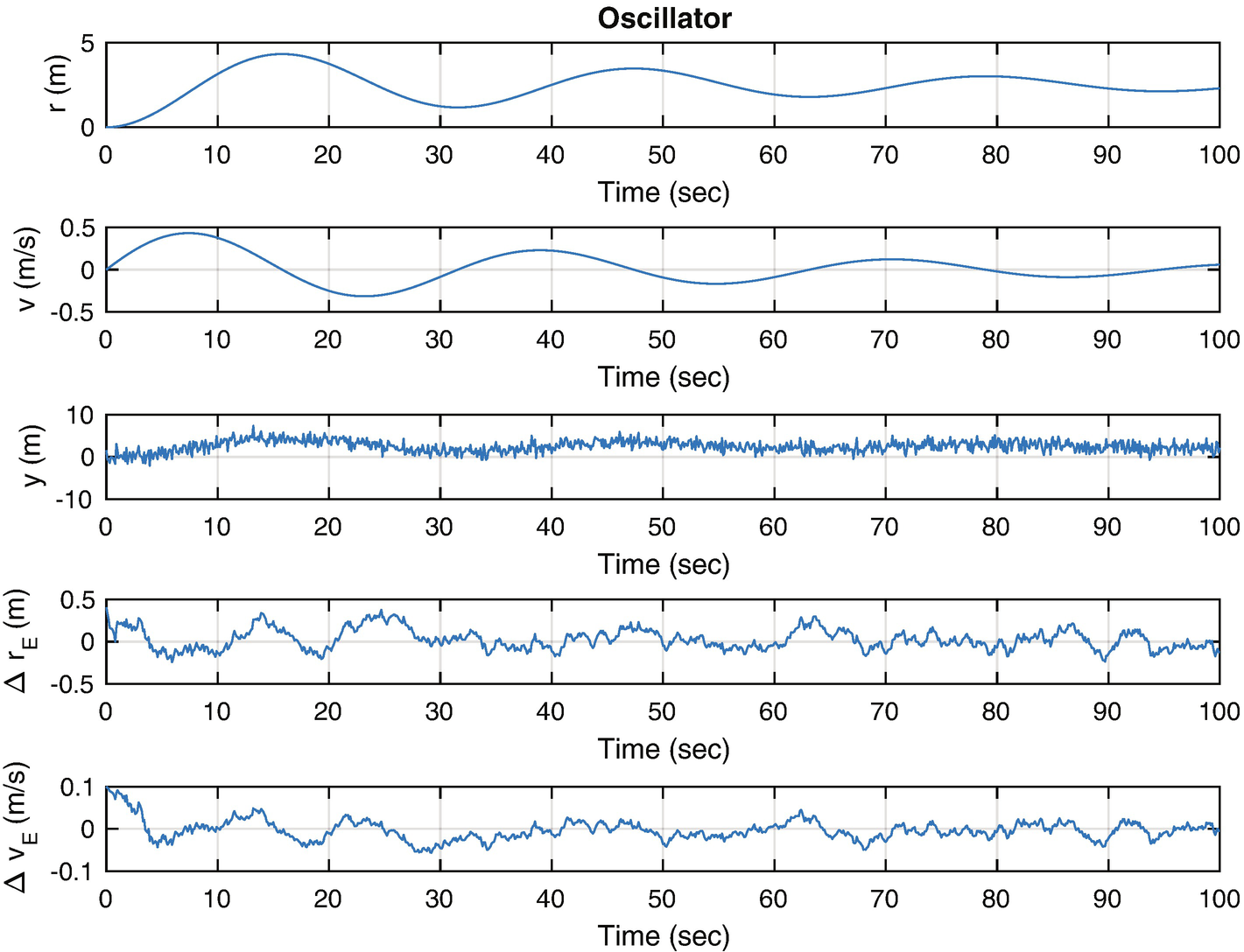

The script gives two examples for the model noise covariance matrix. Figure 4.7 shows results when high numbers, [1e-4 1e-4], for the model covariance are used. Figure 4.8 shows results when lower numbers, [1e-6 1e-6], are used. We don’t change the measurement covariance because only the ratio between noise covariance and model covariance is important.

The Kalman Filter results with the higher model noise matrix, [1e-4 1e-4].

The Kalman Filter results with the lower model noise matrix, [1e-6 1e-6]. Less noise is seen but the errors are large.

4.2 Using the Extended Kalman Filter for State Estimation

4.2.1 Problem

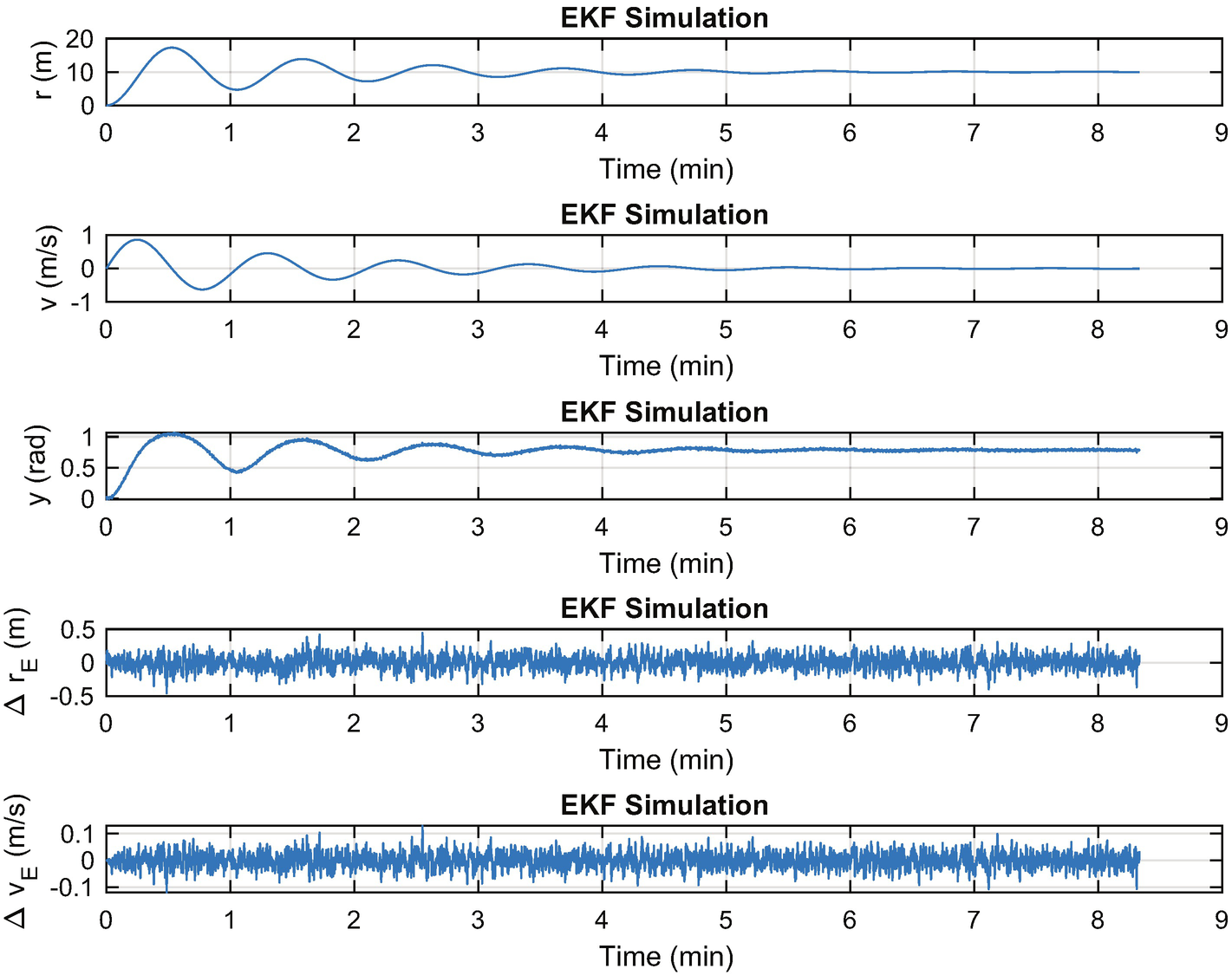

We want to track the damped oscillator using an EKF with the nonlinear angle measurement. The EKF was developed to handle models with nonlinear dynamical models and/or nonlinear measurement models. The conventional, or linear, filter requires linear dynamical equations and linear measurements models, that is, the measurement is a linear function of the state. If the model is not linear, linear filters will not track the states very well.

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} f = \left[ \begin{array}{l} f_x(x,y)\\ f_y(x,y) \end{array} \right] \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ89.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} F_k = \left[ \begin{array}{rr} \frac{\partial f_x(x_k,y_k)}{\partial x}&\frac{\partial f_x(x_k,y_k)}{\partial y}\\ \frac{\partial f_y(x_k,y_k)}{\partial x}&\frac{\partial f_y(x_k,y_k)}{\partial y} \end{array} \right] \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ90.png)

The Jacobians can be found analytically or numerically. If done numerically, the Jacobian needs to be computed about the current value of mk. In the Iterated EKF, the update step is done in a loop using updated values of mk after the first iteration. Hx(m, k) needs to be updated at each step.

4.2.2 Solution

We will use the same KFInitialize function as created in the previous recipe, but now using the ’ekf’ input. We will need functions for the derivative of the model dynamics, the measurement, and the measurement derivatives. These are implemented in RHSOscillator Partial, AngleMeasurement, and AngleMeasurementPartial.

We will also need custom versions of the filter to predict and update steps.

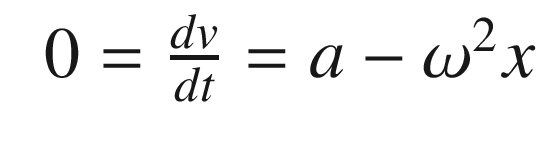

4.2.3 How It Works

You would only use the EKF if ak changed with time. In this problem, it does not. The function to compute a is RHSOscillatorPartial. It uses CToDZOH. We could have computed a once, but using CToDZOH makes the function more general.

Our measurement is nonlinear (being an arctangent) and needs to be linearized about each value of position. AngleMeasurement computes the measurement, which is nonlinear but smooth.

The partial measurement if found by taking the derivative of the arc-tangent of the angle from the baseline. The comment reminds you of this fact.

It is convenient that the measurement function is smooth. If there were discontinuities, the measurement partials would be difficult to compute. The EKF implementation can handle either functions for the derivatives or matrices. In the case of the functions, we use feval to call them. This can be seen in the EKFPredict and EKFUpdate functions.

The EKFSim script implements the EKF with all of the above functions as shown in the following listing. The functions are passed to the EKF in the data structure produced by KFInitialize. Note the use of function handles using @, i.e., @RHSOscillator. Notice that KFInitialize requires hX and fX for computing partial derivatives of the dynamical equations and measurement equations.

The Extended Kalman filter tracks the oscillator using the angle measurement.

4.3 Using the Unscented Kalman Filter for State Estimation

4.3.1 Problem

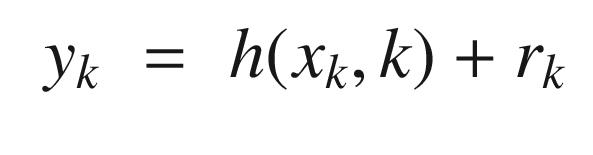

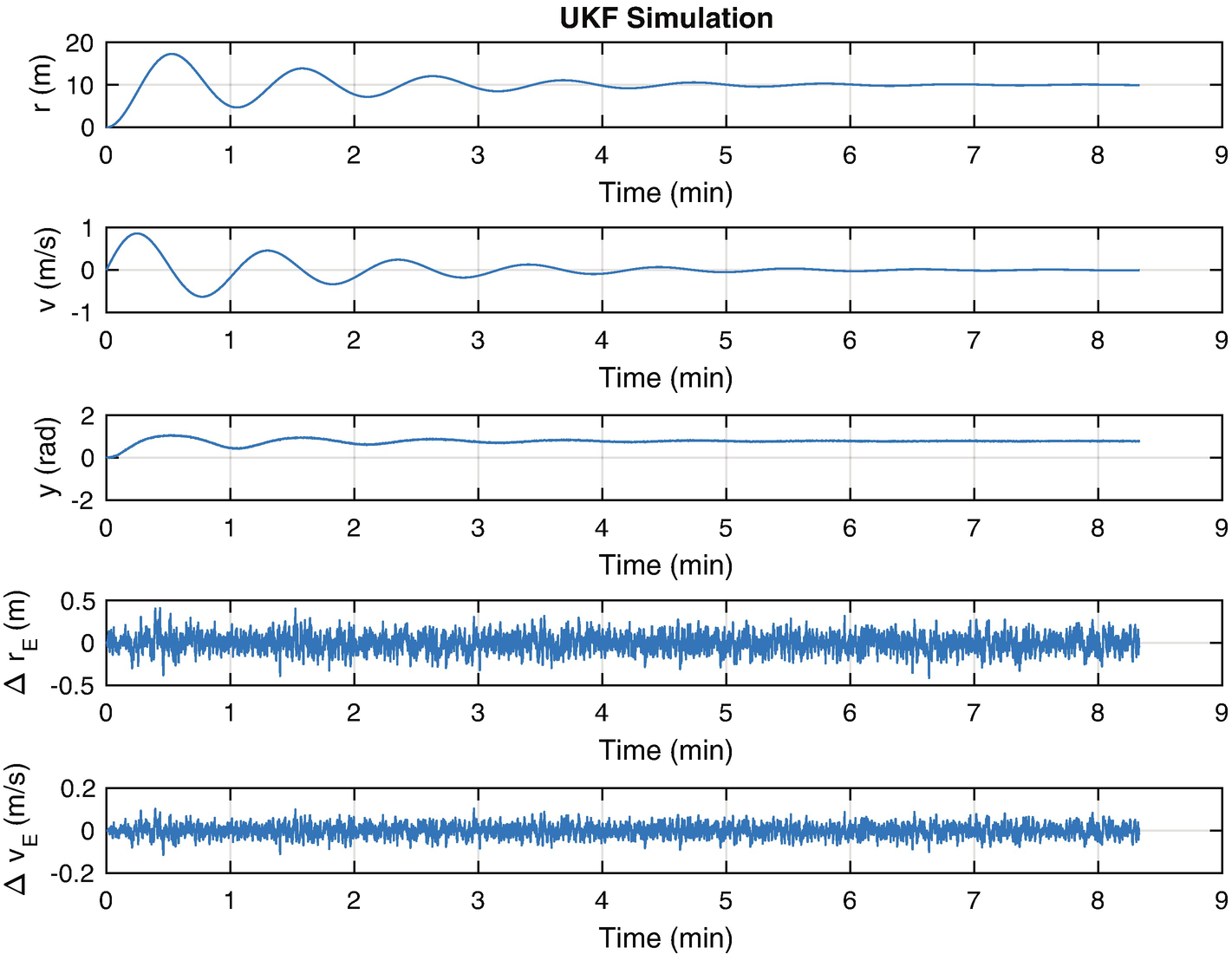

You want to learn the states of the spring, damper, mass system given a nonlinear angle measurement. This time we’ll use an UKF. With the UKF, we work with the nonlinear dynamical and measurement equations directly. We don’t have to linearize them as we did for the EKF with RHSOscillatorPartial and AngleMeasurementPartial. The UKF is also known as a sigma σ point filter because it simultaneously maintains models one sigma (standard deviation) from the mean.

4.3.2 Solution

We will create an UKF as a state estimator. This will absorb measurements and determine the state. It will autonomously learn about the state of the system based on a pre-existing model.

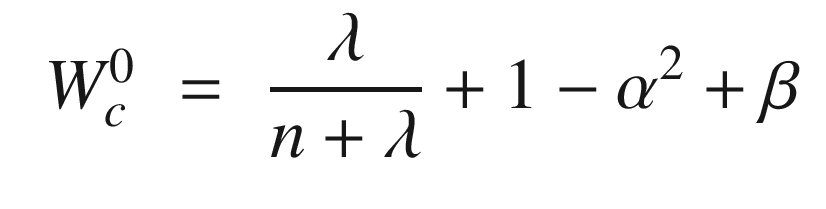

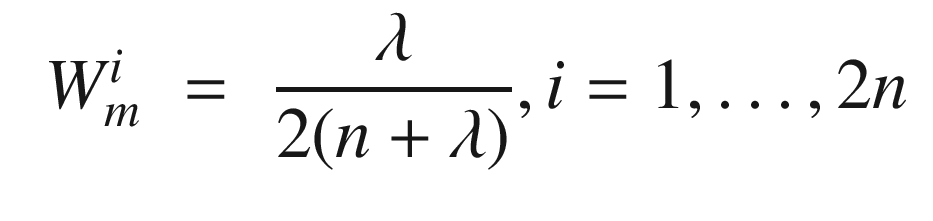

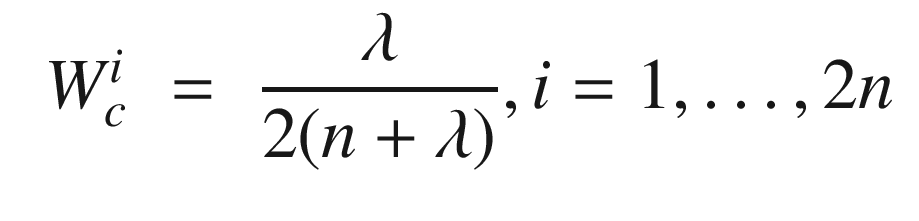

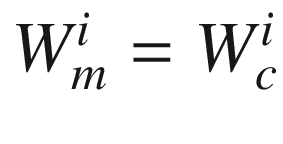

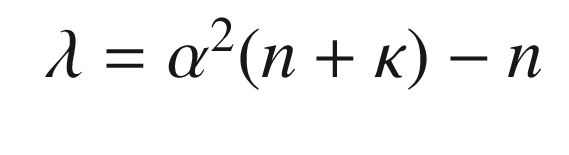

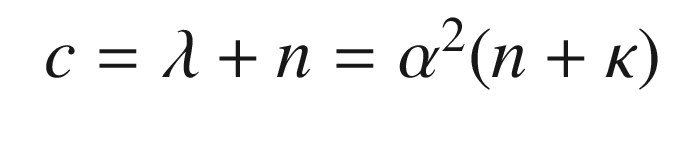

.

.

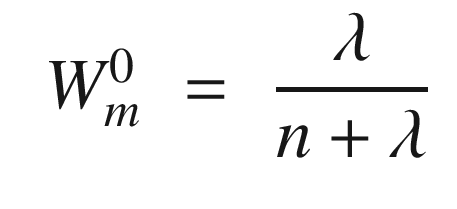

α – 0 for state estimation, 3 minus the number of states for parameter estimation.

β – Determines the spread of sigma points. Smaller means more closely spaced sigma points.

κ – Constant for prior knowledge. Set to 2 for Gaussian processes.

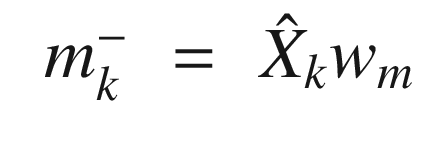

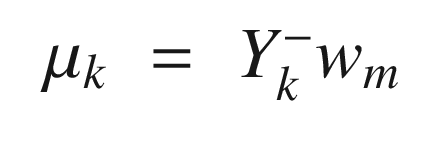

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} w_m &=& \left[W_m^0 \cdots W_m^{2n}\right]^T \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ102.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} W &=& \left(I - \left[w_m \cdots w_m\right]\right) \left[ \begin{array}{ccc} W_c^0 & \cdots & 0\\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ 0 & \cdots & W_c^{2n} \end{array} \right] \left(I - \left[w_m \cdots w_m\right]\right)^T \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ103.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} X_{k-1} &=& \left[ \begin{array}{ccc} m_{k-1}&\cdots& m_{k-1} \end{array} \right] + \sqrt{c}\left[ \begin{array}{ccc} 0 & \sqrt{P_{k-1}} & -\sqrt{P_{k-1}} \end{array} \right] \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ104.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} X_k^- &=& \left[ \begin{array}{ccc} m_k^- &\cdots& m_k^- \end{array} \right] + \sqrt{c}\left[ \begin{array}{ccc} 0 & \sqrt{P_k^-} & -\sqrt{P_k^-} \end{array} \right] \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ108.png)

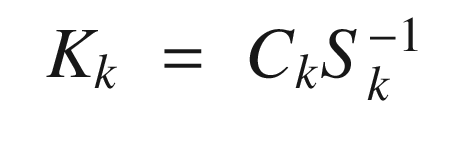

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} S_k &=& Y_k^-W[Y_k^-]^T + R_k \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ111.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} C_k &=& X_k^-W[Y_k^-]^T \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ112.png)

are just for clarity.

are just for clarity.4.3.3 How It Works

The weights are computed in UKFWeight.

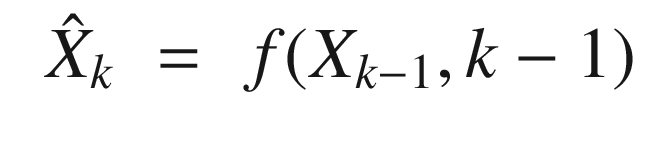

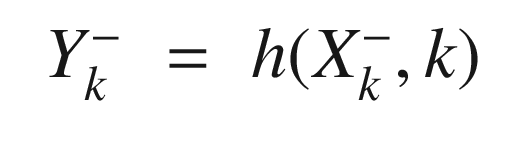

The prediction UKF step is shown in the following excerpt from UKFPredict.

UKFPredict uses RungeKutta for prediction, which is done by numerical integration. In effect, we are running a simulation of the model and just correcting the results with the next function, UKFUpdate. This gets to the core of the Kalman Filter. It is just a simulation of your model with a measurement correction step. In the case of the conventional linear Kalman Filter, we use a linear discrete time model.

The update UKF step is shown in the following listing. The update propagates the state one time step.

The sigma points are generated using chol. chol is Cholesky factorization and generates an approximate square root of a matrix. A true matrix square root is more computationally expensive and the results don’t really justify the penalty. The idea is to distribute the sigma points around the mean and chol works well. Here is an example that compares the two approaches:

The square root actually produces a square root! The diagonal of b*b is close to z, which is all that is important.

The script for testing the UKF, UKFSim, is shown below. As noted earlier, we don’t need to convert the continuous time model into discrete time as we did for the Kalman Filter and EKF. Instead, we pass the filter the right-hand side of the differential equations. You must also pass it a measurement model, which can be nonlinear. You add UKFUpdate and UKFPredict function calls to the simulation loop. We start by initializing all parameters. KFInitialize takes parameter pairs, after ’ukf’ to initialize the filter. The remainder is the simulation loop and plotting. Initialization requires computation of the weighting matrices after calling KFInitialize.

We show the simulation loop here:

The Unscented Kalman filter results for state estimation.

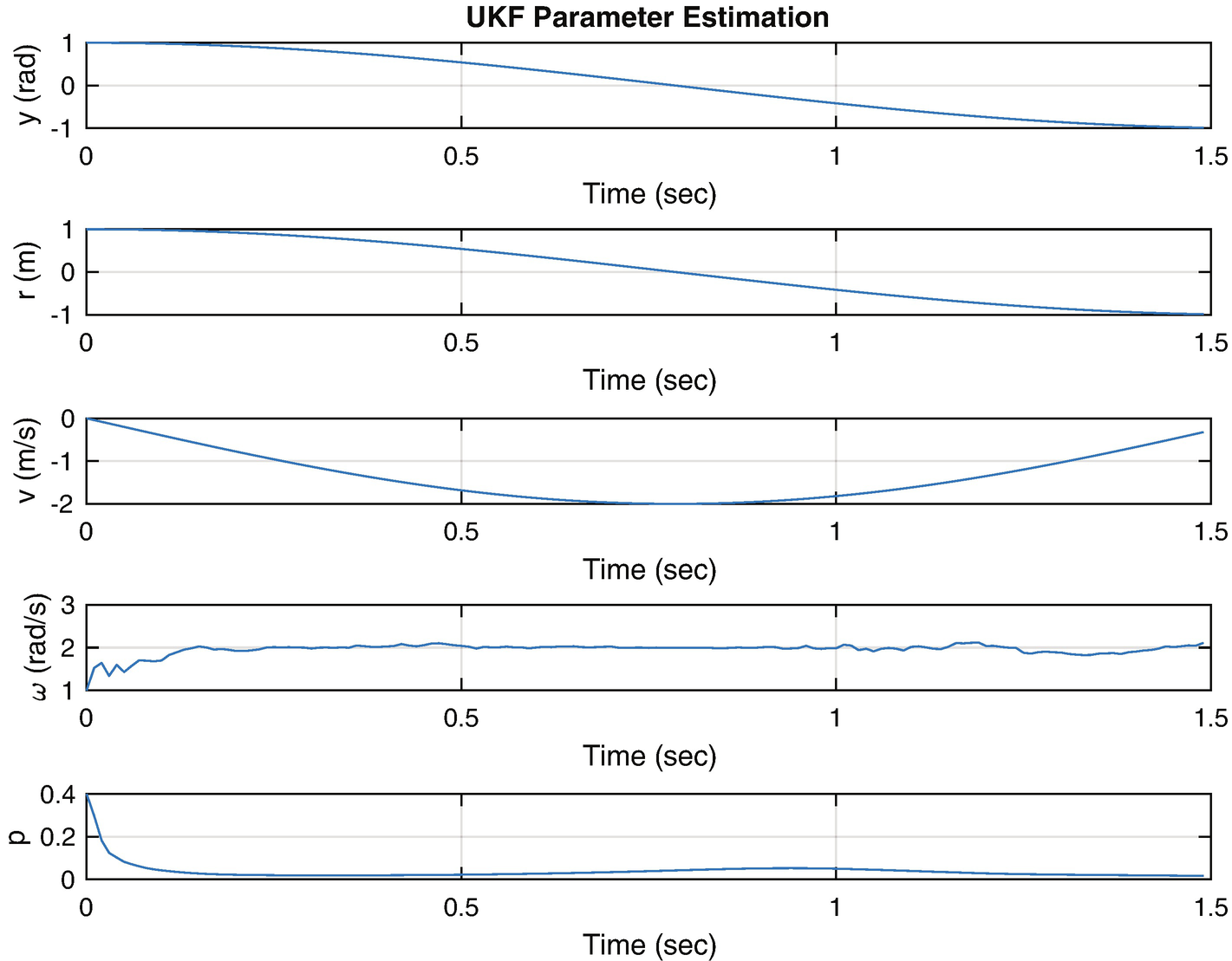

4.4 Using the UKF for Parameter Estimation

4.4.1 Problem

You want to learn the parameters of the spring-damper-mass system given a nonlinear angle measurement. The UKF can be configured to do this.

4.4.2 Solution

The solution is to create a UKF configured as a parameter estimator. This will absorb measurements and determine the undamped natural frequency. It will autonomously learn about the system based on a pre-existing model. We develop the version that requires an estimate of the state that could be generated with a UKF running in parallel, as in the previous recipe.

4.4.3 How It Works

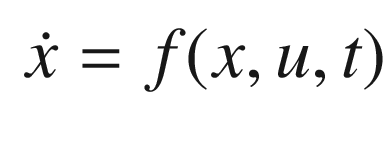

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \eta_{\sigma}= \left[ \begin{array}{ccc} \hat{\eta} & \hat{\eta} + \gamma\sqrt{P}& \hat{\eta} - \gamma\sqrt{P} \end{array} \right] \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_4_Chapter/420697_2_En_4_Chapter_TeX_Equ119.png)

The script UKFPSim for testing the UKF parameter estimation is shown below. We are not doing the UKF state estimation to simplify the script. Normally, you would run the UKF in parallel. We start by initializing all parameters. KFInitialize takes parameter pairs to initialize the filters. The remainder is the simulation loop and plotting. Notice that there is only an update call, since parameters, unlike states, do not propagate.

The UKF parameter update function is shown in the following code. It uses the state estimate generated by the UKF. As noted, we are using the exact value of the state generated by the simulation. This function needs a specialized right-hand side that uses the parameter estimate, d.eta. We modified RHSOscillator for this purpose and wrote RHSOscillatorUKF.

It also has its own weight initialization function UKFPWeight.m. The weight matrix is used by the matrix form of the Unscented Transform. The constant alpha determines the spread of the sigma points around the parameter vector and is usually set to between 10e-4 and 1. beta incorporates prior knowledge of the distribution of the parameter vector and is 2 for a Gaussian distribution. kappa is set to 0 for state estimation and 3 the number of states for parameter estimation.

RHSOscillatorUKF is the oscillator model used by the UKF. It has a different input format than RHSOscillator. There is only one line of code.

LinearMeasurement is a simple measurement function for demonstration purposes. The UKF can use arbitrarily complex measurement functions.

The Unscented Kalman parameter estimation results. p is the covariance. It shows that our parameter estimate has converged.

4.5 Summary

Chapter Code Listing

File | Description |

|---|---|

AngleMeasurement | Angle measurement of the mass. |

AngleMeasurementPartial | Angle measurement derivative. |

LinearMeasurement | Position measurement of the mass. |

OscillatorSim | Simulation of the damped oscillator. |

OscillatorDampingRatioSim | Simulation of the damped oscillator with different damping ratios. |

RHSOscillator | Dynamical model for the damped oscillator. |

RHSOscillatorPartial | Derivative model for the damped oscillator. |

RungeKutta | Fourth-order Runge–Kutta integrator. |

PlotSet | Create two-dimensional plots from a data set. |

TimeLabel | Produce time labels and scaled time vectors. |

Gaussian | Plot a Gaussian distribution. |

KFInitialize | Initialize Kalman Filters. |

KFSim | Demonstration of a conventional Kalman Filter. |

KFPredict | Prediction step for a conventional Kalman Filter. |

KFUpdate | Update step for a conventional Kalman Filter. |

EKFPredict | Prediction step for an Extended Kalman Filter. |

EKFUpdate | Update step for an Extended Kalman Filter. |

UKFPredict | Prediction step for an Unscented Kalman Filter. |

UKFUpdate | Update step for an Unscented Kalman Filter. |

UKFPUpdate | Update step for an Unscented Kalman Filter parameter update. |

UKFSim | Demonstration of an Unscented Kalman Filter. |

UKFPSim | Demonstration of parameter estimation for the Unscented Kalman Filter. |

UKFWeights | Generates weights for the Unscented Kalman Filter. |

UKFPWeights | Generates weights for the Unscented Kalman Filter parameter estimator. |

RHSOscillatorUKF | Dynamical model for the damped oscillator for use in Unscented Kalman Filter parameter estimation. |