One of the issues with machine learning is understanding the algorithms and why an algorithm made a particular decision. In addition, you want to be able to easily understand the decision. MATLAB has extensive graphics facilities that can be harnessed for that purpose. Plotting is used extensively in machine learning problems. MATLAB plots can be two- or three-dimensional. MATLAB also has many plot types such as line plots, bar charts, and pie charts. Different types of plots are better at conveying particular types of data. MATLAB also has extensive surface and contour plotting capabilities that can be used to display complex data in an easy-to-grasp fashion. Another facility is 3D modeling. You can draw animated objects, such as robots or automobiles. These are particularly valuable when your machine learning involves simulations.

An important part of MATLAB graphics is Graphical User Interface (GUI) building. MATLAB has extensive facilities for making GUIs. These can be a valuable way of making your design tools or machine learning systems easy for users to operate.

This chapter will provide an introduction to a wide variety of graphics tools in MATLAB. They should allow you to harness MATLAB graphics for your own applications.

3.1 2D Line Plots

3.1.1 Problem

You want a single function to generate two-dimensional line graphs, avoiding a long list of code for the generation of each graphic.

3.1.2 Solution

PlotSet’s built-in demo.

3.1.3 How It Works

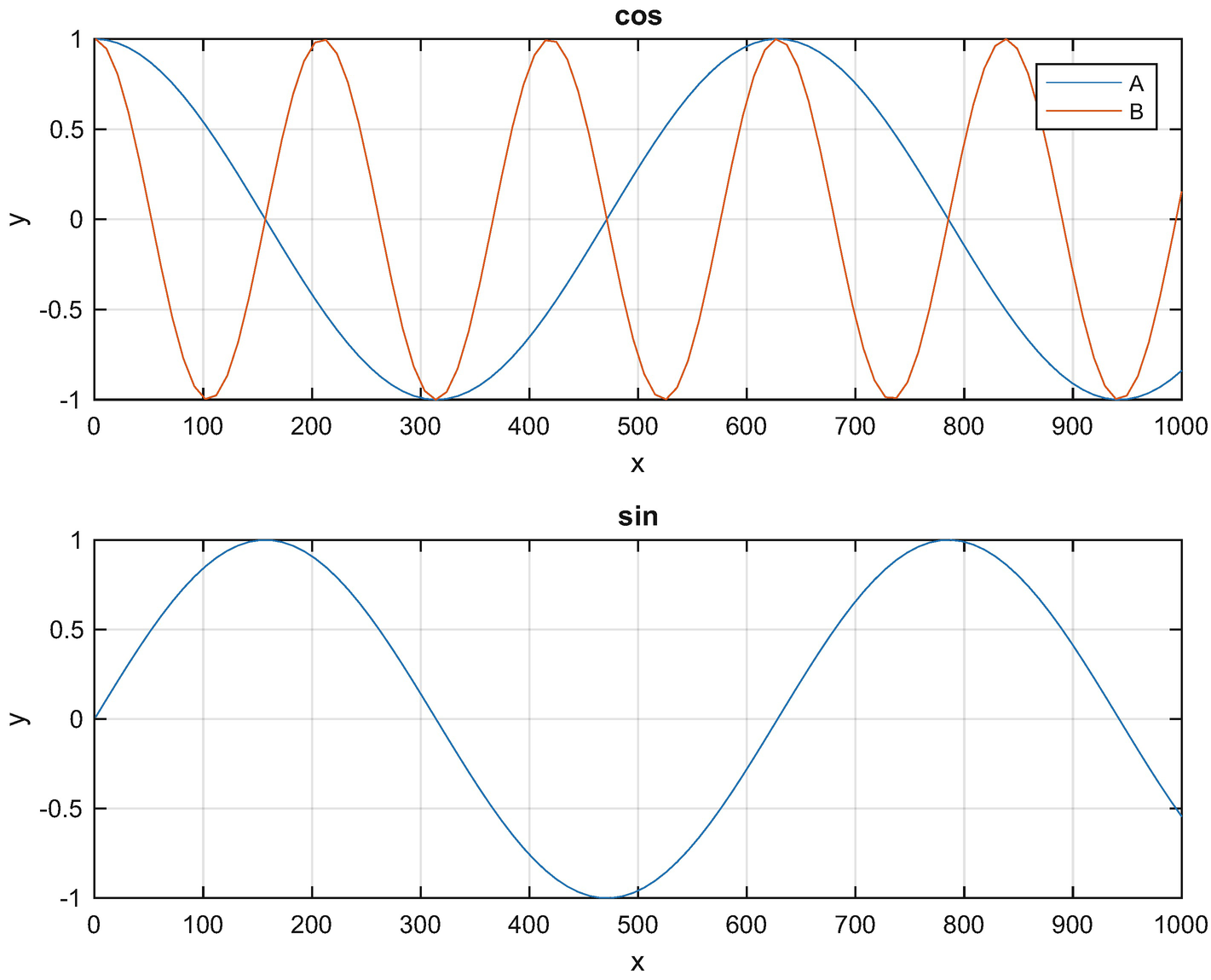

PlotSet generates 2D plots, including multiple plots on a page.

function h = PlotSet( x, y, varargin )

This code processes varargin as parameter pairs to set options. A parameter pair is two inputs. The first is the name of the value and the second is the value. For example, the parameter pair for labeling the x-axis is:

’x label’,’Time ( s) ’

varargin makes it easy to expand the plotting options. The core function code is shown below. We supply default values for the x and y axis labels and the figure name. The parameter pairs are handled in a switch statement. The following code is the branch when there is only one x-axis label for all of the plots. It arranges plots by the data in plotSet that is a cell array.

The plotting is done in a subfunction called plotXY. There you see all the familiar MATLAB plotting function calls.

- 1.

Multiple lines per graph

- 2.

Legends

- 3.

Plot titles

- 4.

Default axes labels

3.2 General 2D Graphics

3.2.1 Problem

You want to represent a 2D data set in different ways. Line plots are very useful, but sometimes it is easier to visualize data in different forms. MATLAB has many functions for 2D graphical displays.

3.2.2 Solution

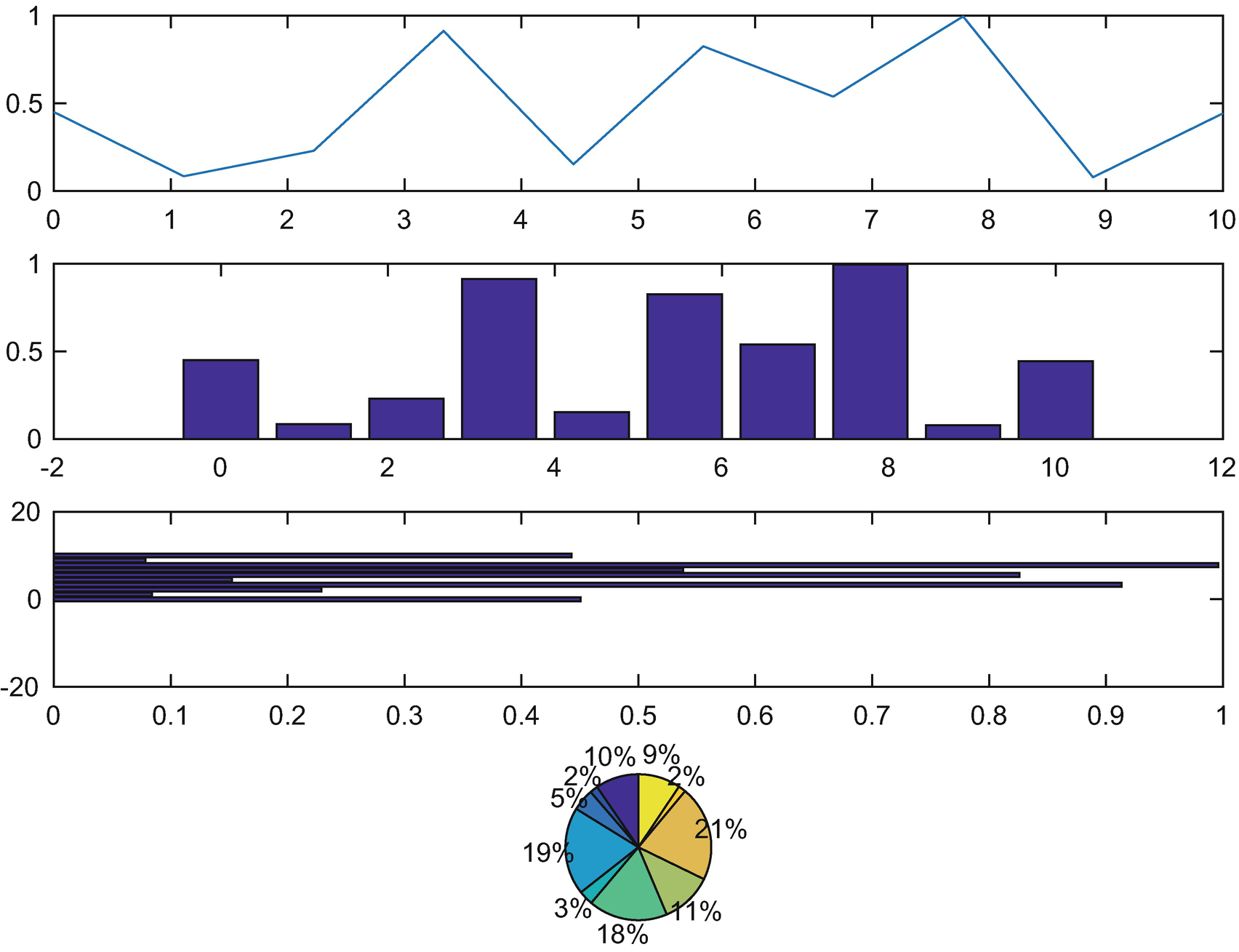

Write a script to show MATLAB’s different 2D plot types. In our example we use subplots within one figure to help reduce figure proliferation.

3.2.3 How It Works

Use the NewFigure function to create a new figure window with a suitable name. Then run the following script.

Four plot types are shown that are helpful in displaying 2D data. One is the 2D line plot, the same as that used in PlotSet. The middle two are bar charts. The final is a pie chart. Each gives you different insight into the data. Figure 3.2 shows the plot types.

Add labels

Add grids

Four different types of MATLAB 2D plots.

Change font types and sizes

Change the thickness of lines

Add legends

Change axes limits

The last item requires looking at the axes’ properties. Here are the properties for the last plot – the list is very long! gca is the handle to the current axes. get( gca) returns a huge list, which we will not print here. Every single one of these can be changed by using the set function:

This uses parameter pairs just like PlotSet. In this list, children are pointers to the children of the axes. You can access those using get and change their properties using set. Any item that is added to an axis, such as axis labels, titles, lines, or other graphics objects, are all children of that axis.

3.3 Custom Two-Dimensional Diagrams

3.3.1 Problem

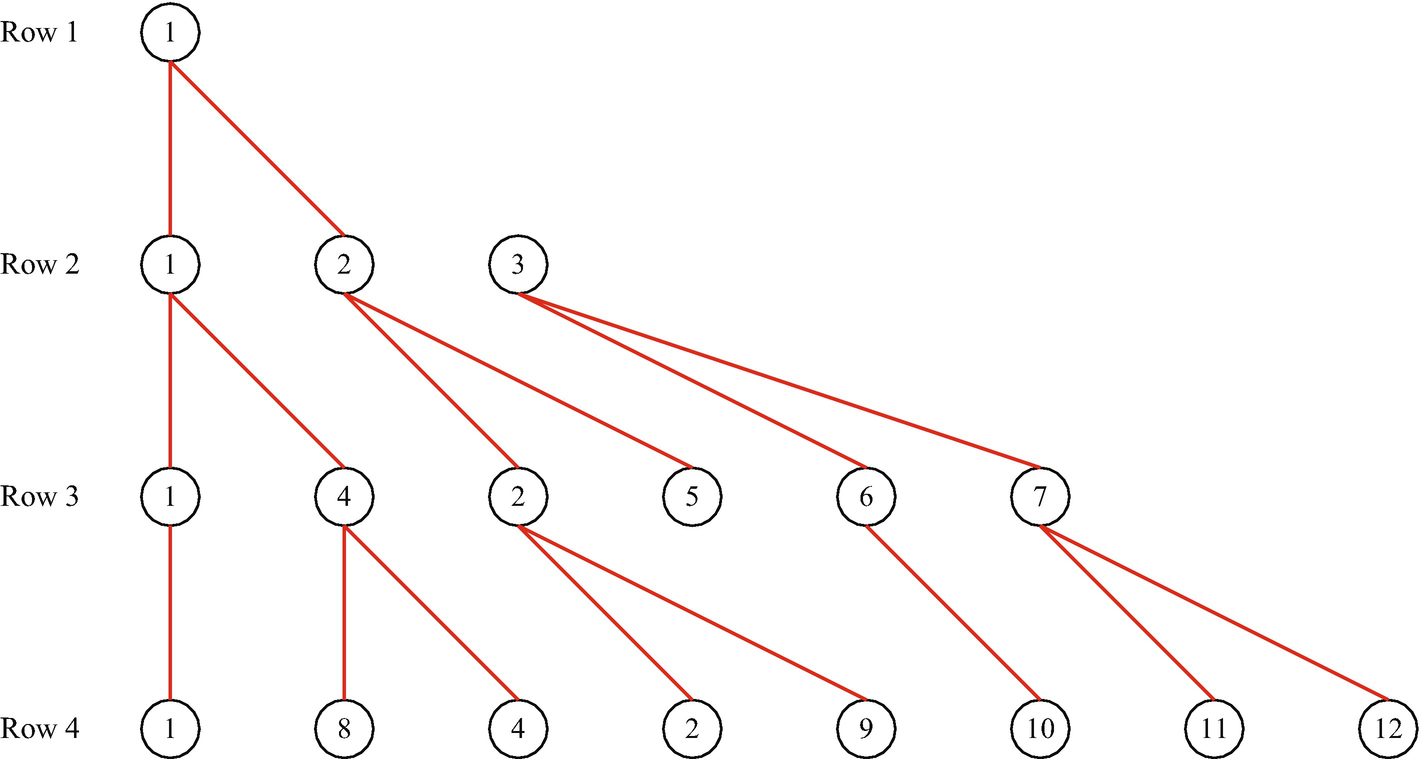

Many machine learning algorithms benefit from two-dimensional diagrams such as tree diagrams, to help the user understand the results and the operation of the software. Such diagrams, automatically generated by the software, are useful in many types of learning systems. This section gives an example of how to write MATLAB code for a tree diagram.

3.3.2 Solution

Our solution is to use the MATLAB patch function to automatically generate the blocks, and use line to generate connecting lines in the function TreeDiagram. Figure 3.3 shows the resulting hierarchical tree diagram. The circles are in rows and each row is labeled.

3.3.3 How It Works

Tree diagrams are very useful for machine learning. This function generates a hierarchical tree diagram with the nodes as circles with text within each node. The graphics functions used in this function are:

- 1.

line

- 2.

patch

- 3.

text

A custom tree diagram.

The function uses a figure handle as a persistent variable so that the same figure can be updated with subsequent calls, if desired.

The core drawing code is in DrawNode, which draws the boxes and ConnectNode, which connects the nodes with lines. Our nodes are circles with 20 segments. The linspace code makes sure that both 0 and 2π are not in the list of angles.

The builtin in demo in TreeDiagram.

3.4 Three-Dimensional Box

There are two broad classes of three-dimensional graphics. One is to draw an object, like the earth. The other is to draw large data sets. This recipe plus the following one will show you how to do both.

3.4.1 Problem

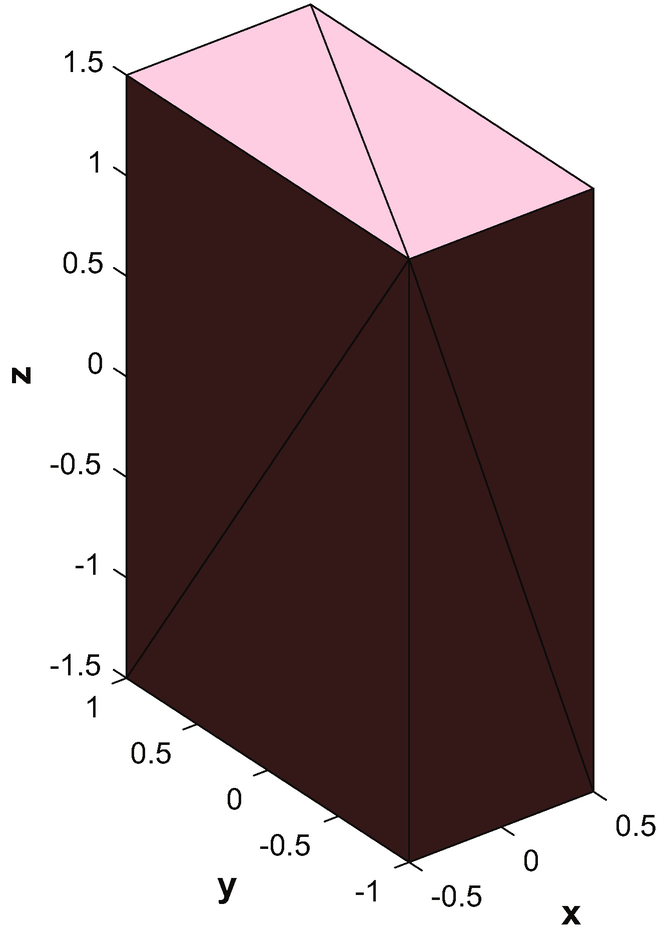

We want to draw a three-dimensional box.

3.4.2 Solution

The function Box3 users the patch function to draw the object. An example is shown in Figure 3.4.

3.4.3 How It Works

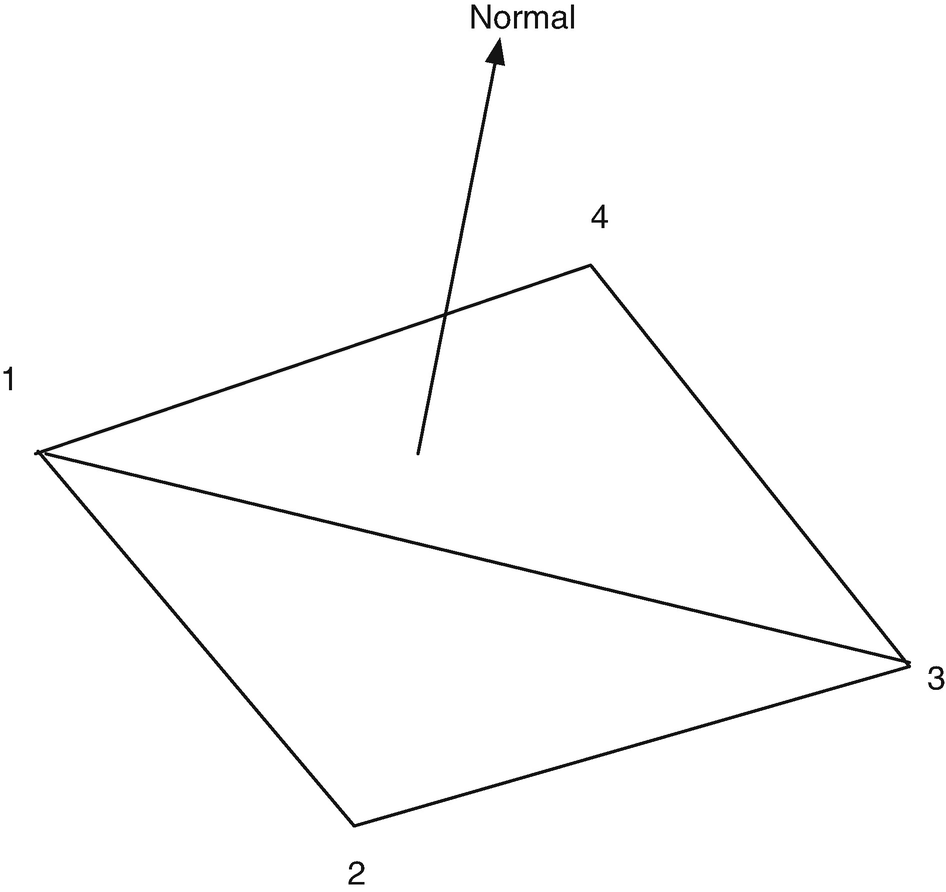

Three-dimensional objects are created from vertices and faces. A vertex is a point in space. You create a list of vertices that are the corners of your 3D object. You then create faces that are lists of vertices. A face with two vertices is a line, one with three vertices is a triangle. A polygon can have as many vertices as you would like. However, at the lowest level, graphics processors deal with triangles so you are better off making all patches triangles.

A box drawn with patch.

A patch. The normal is toward the camera or the “outside” of the object.

MATLAB lighting is not very picky about vertex ordering, but if you export a model, then you will need to follow this convention. Otherwise, you can end up with inside-out objects!

The following code creates a box composed of triangle patches. The face and vertex arrays are created by hand. Vertices are one vertex per row so vertex arrays are n by 3. Face arrays are n by m where m is the largest number of vertices per face. In Box we work with triangles only. All graphics processors ultimately draw triangles so, if you can, it is best to create objects only with triangles.

The box is drawn using patch in the function DrawVertices. There is just one call to patch. patch accepts parameter pairs to specify face and edge coloring and many other characteristics of the patch. Only one color can be specified for a patch. If you wanted a box with different colors on each side, you would need multiple patches. We turn on rotate3d so that we can reorient the object with the mouse. view3 is a standard MATLAB view with the eye looking down a corner of the grid box.

We use only the most basic lighting. You can add all sorts of lights in your drawing using light. Light can be ambient or from a variety of light sources.

3.5 Draw a 3D Object with a Texture

3.5.1 Problem

We want to draw a planet with a texture.

3.5.2 Solution

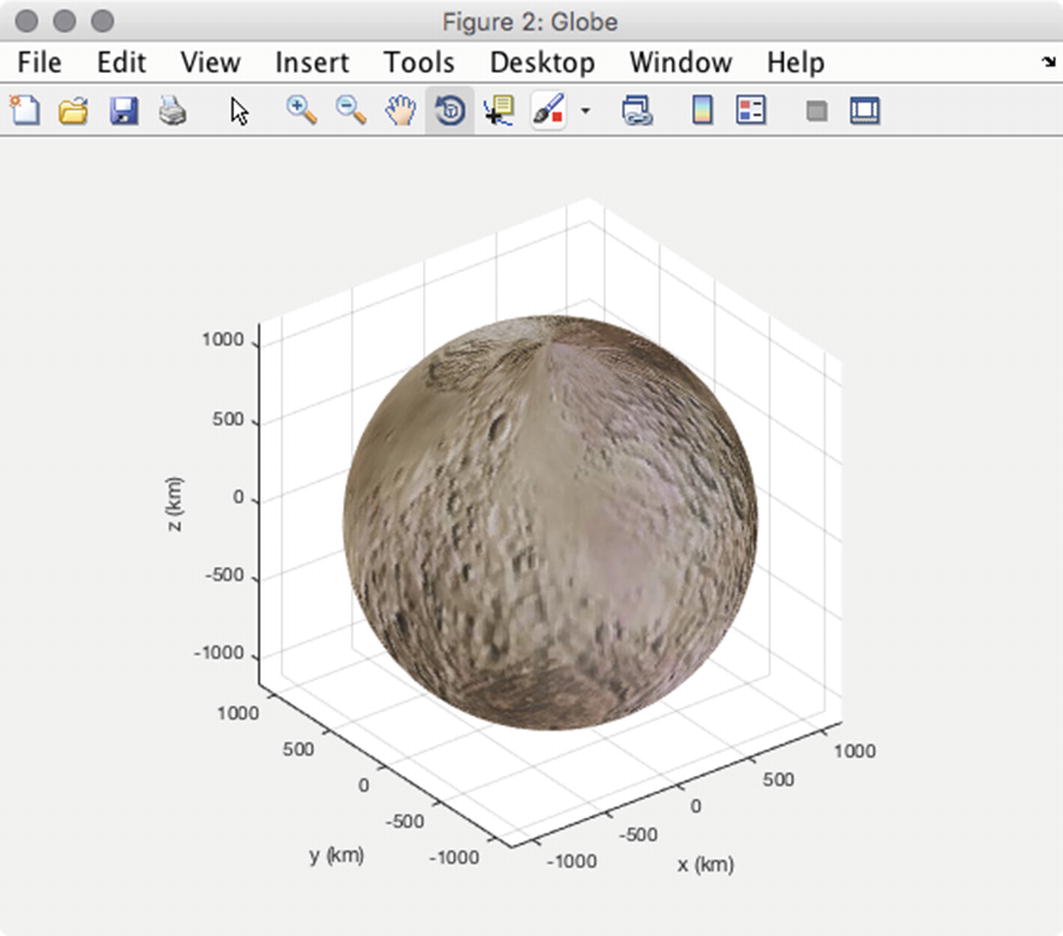

Use a surface and overlay a texture onto the surface. Figure 3.6 shows an example with a recent image of Pluto using the function Globe.

A three-dimensional globe of Pluto.

3.5.3 How It Works

We generate the picture by first creating x, y, z points on the sphere and then overlaying a texture that is read in from an image file. The texture map can be read from a file using imread. If this is color, it will be a three-dimensional matrix. The third element will be an index to the color, red, blue or green. However, if it is a grayscale image, you must create the three-dimensional “color” matrix by replicating the image.

The starting p is a two-dimensional matrix.

You first generate the surface using the coordinates generated from the sphere function. This is done with surface. You then apply the texture:

flipup makes the map look “normal.” Phong is a type of lighting. It takes the colors at the vertices and interpolates the colors at the pixels on the polygon based on the interpolated normals. Diffuse and specular refer to different types of reflections of light. They aren’t too important when you apply a texture to the surface.

3.6 General 3D Graphics

3.6.1 Problem

We want to use 3D graphics to study a 2D data set. A 2D data set is a matrix or an n by m array.

3.6.2 Solution

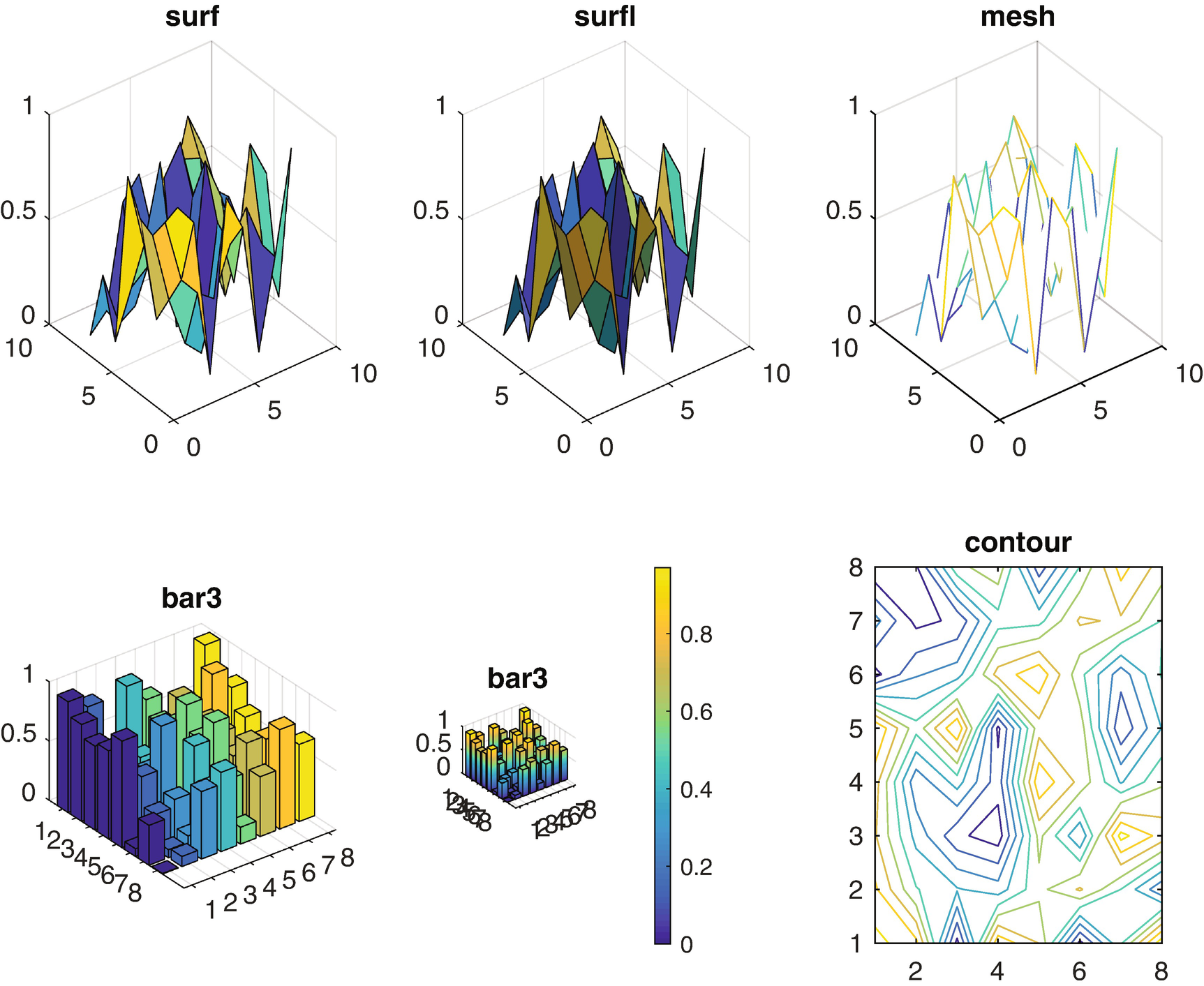

Use MATLAB surface, mesh, bar and contour functions. TwoDDataDisplay gives an example of a random data set with different visualizations is shown in Figure 3.7.

3.6.3 How It Works

We generate a random 2D data set that is 8x8 using rand. We display it in several ways in a figure with subplots. In this case, we create two rows and three columns of subplots. Figure 3.7 shows six types of 2D plots. surf, mesh and surfl (3D shaded surface with lighting) are very similar. The surface plots are more interesting when lighting is applied. The two bar3 plots show different ways of coloring the bars. In the second bar plot, the color varies with length. This requires a bit of code changing the CData and FaceColor.

3.7 Building a GUI

3.7.1 Problem

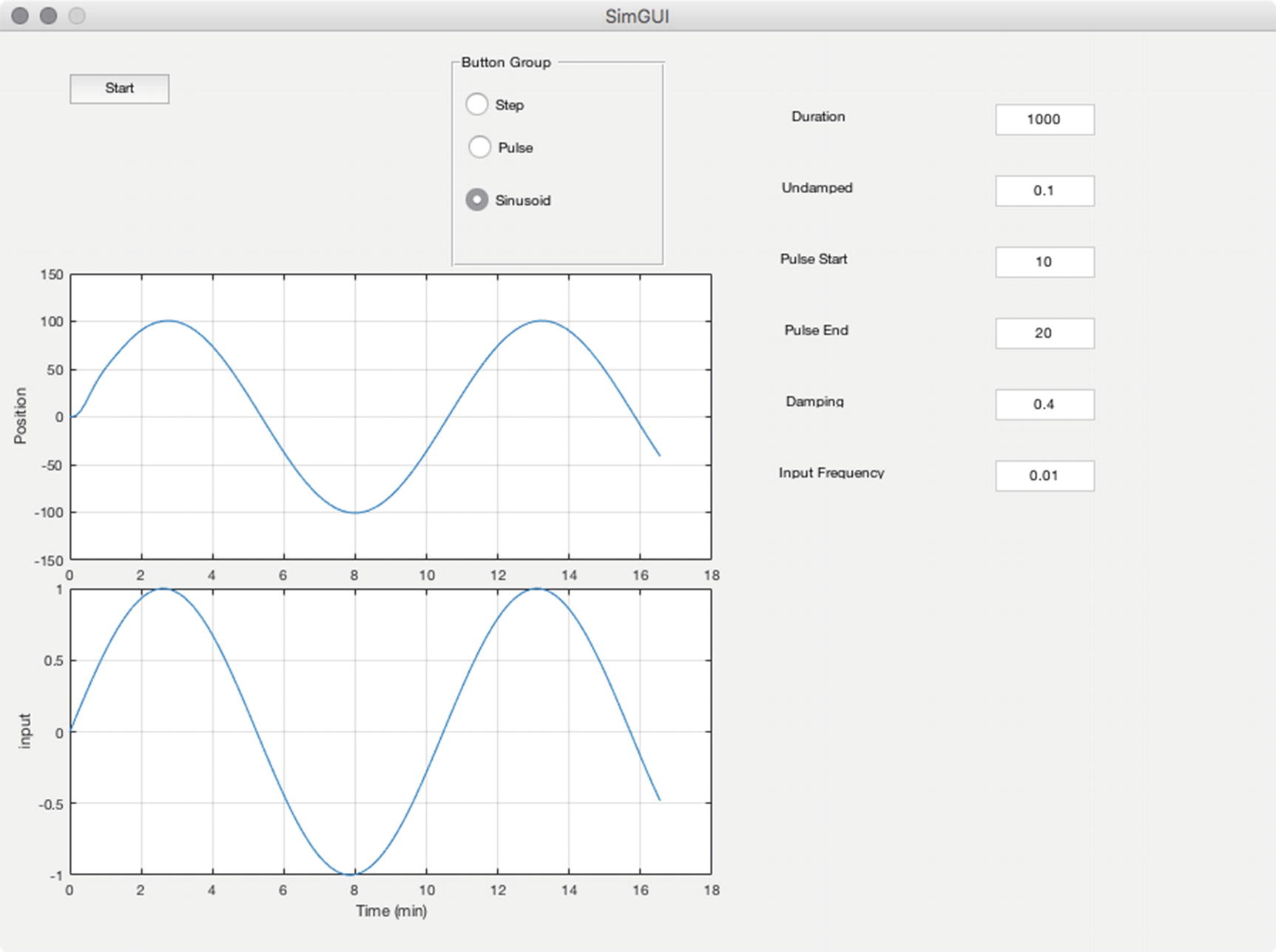

We want a GUI to provide a graphical interface for a second-order system simulation.

3.7.2 Solution

- 1.

Set the damping constant

- 2.

Set the end time for the simulation

- 3.

Set the type of input (pulse, step or sinusoid)

- 4.

Display the inputs and outputs plot

3.7.3 How It Works

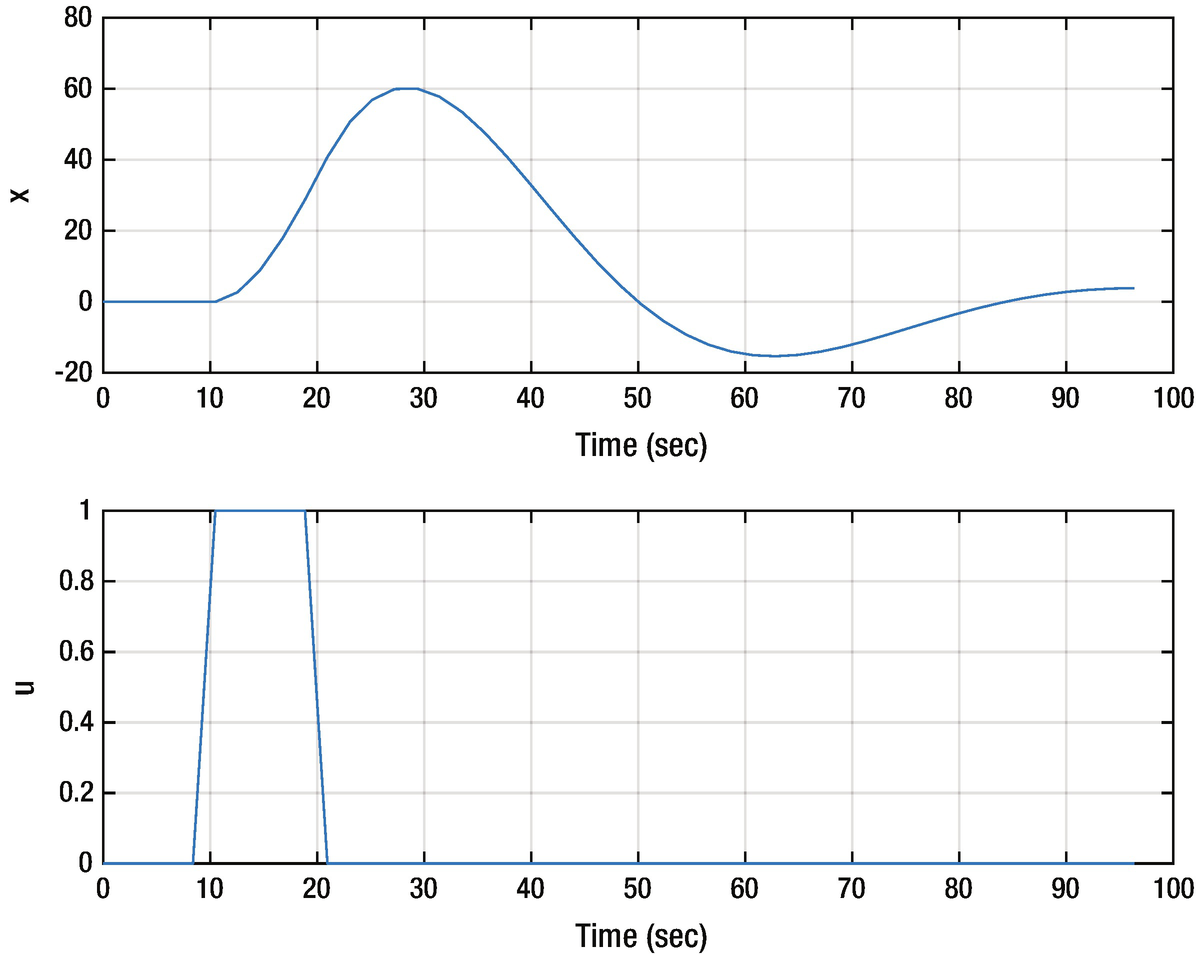

We want to build a GUI to interface with SecondOrderSystemSim shown below. The first part of SecondOrderSystemSim is the simulation code in a loop.

Two-dimensional data shown with six different plot types.

Second-order system simulation.

TimeLabel makes time units that are reasonable for the length of the simulation. It automatically rescales the time vector. The function has the simulation loop built in.

The MATLAB GUI building system, GUIDE, is invoked by typing guide at the command line. We are using MATLAB R2018a. There may be subtle differences in your version.

- Edit boxes for:

Simulation duration

Damping ratio

Undamped natural frequency

Sinusoid input frequency

Pulse start and stop time

Figure 3.9

Figure 3.9Blank GUI.

Radio button for the type of input

Run button for starting a simulation

Plot axes

We type “guide” in the command window and it asks us to either pick an existing GUI or create a new one. We choose a blank GUI. Figure 3.9 shows the template GUI in GUIDE before we make any changes to it. You add elements by dragging and dropping from the table at the left.

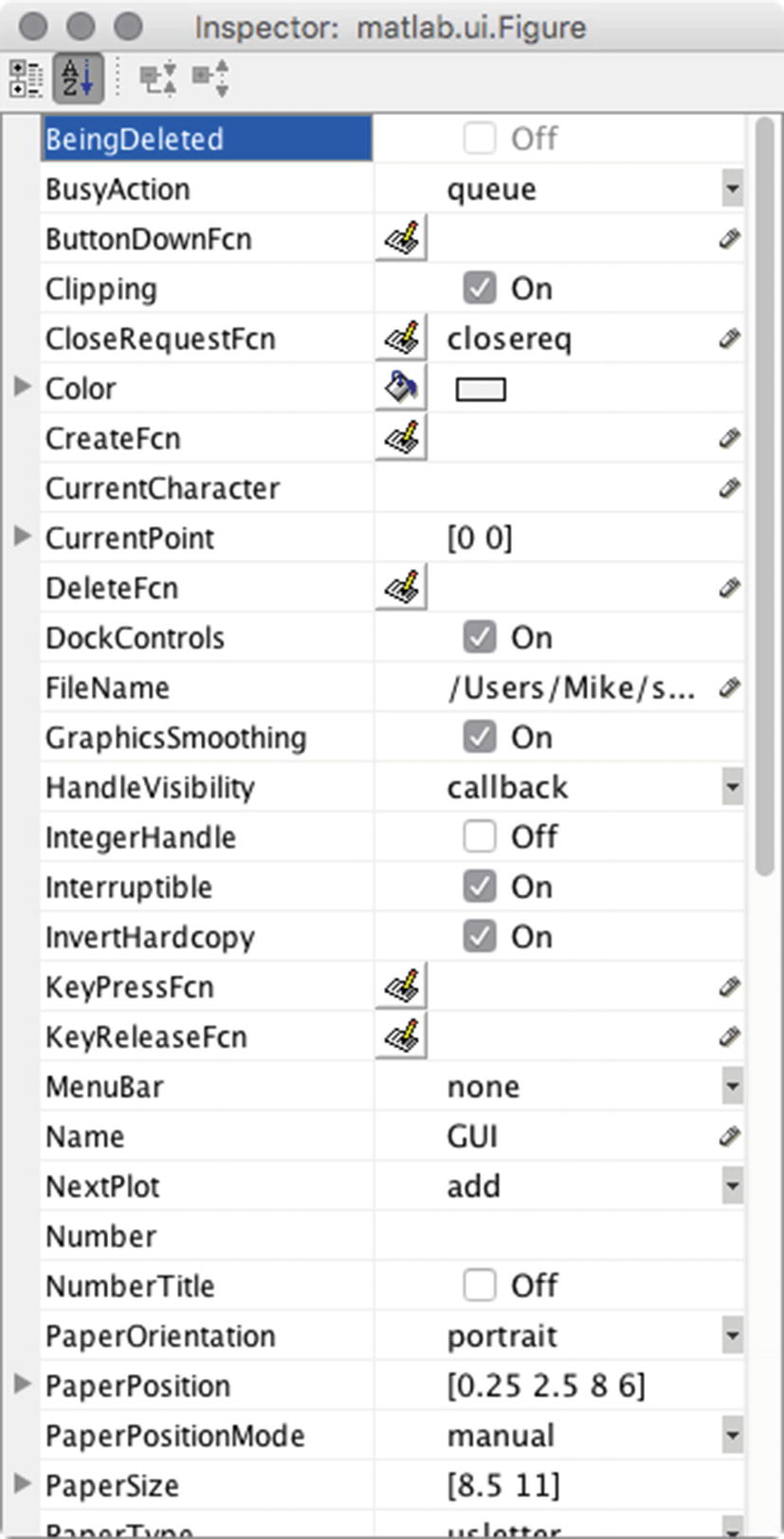

Figure 3.10 shows the GUI inspector. You edit GUI elements here. You can see that the elements have a lot of properties. We aren’t going to try and make this GUI really slick, but with some effort you can make it a work of art. The ones we will change are the tag and text properties. The tag gives the software a name to use internally. The text is just what is shown on the device.

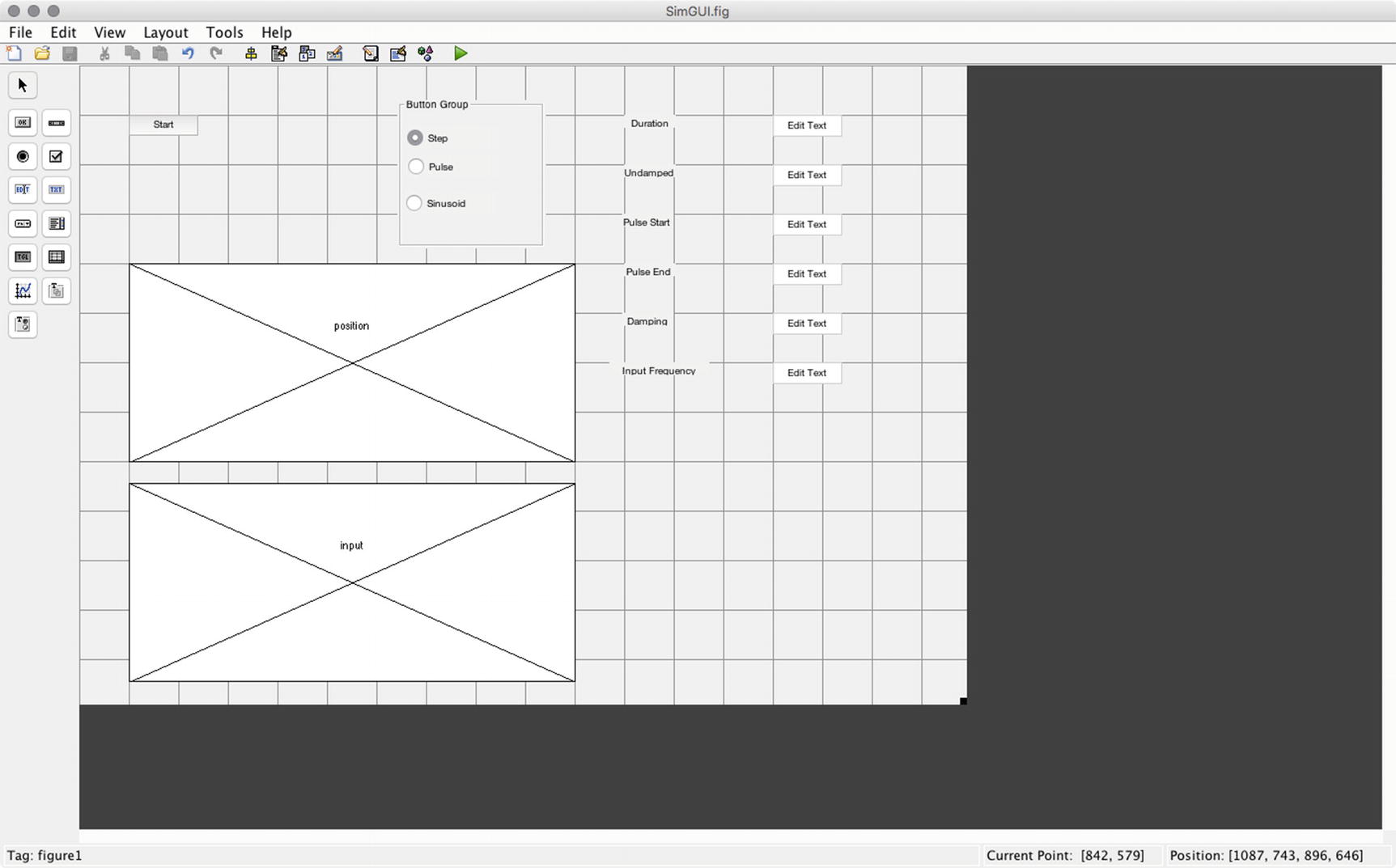

We then add all the desired elements by dragging and dropping. We choose to name our GUI “GUI”. The resulting initial GUI is shown in Figure 3.11. In the inspector for each element you will see a field for “tag.” Change the names from things like edit1 to names you can easily identify. When you save them and run the GUI from the .fig file the code in GUI.m will automatically change.

The GUI inspector.

At this point, we can start work on the GUI code itself. The template GUI stores its data, calculated from the data the user types into the edit boxes, in a field called simdata. The autogenerated code is in SimGUI.

When the GUI loads, we initialize the text fields with the data from the default data structure. Make sure that the initialization corresponds to what is seen in the GUI. You need to be careful about radio buttons and button states.

Snapshot of the GUI in the editing window after adding all the elements.

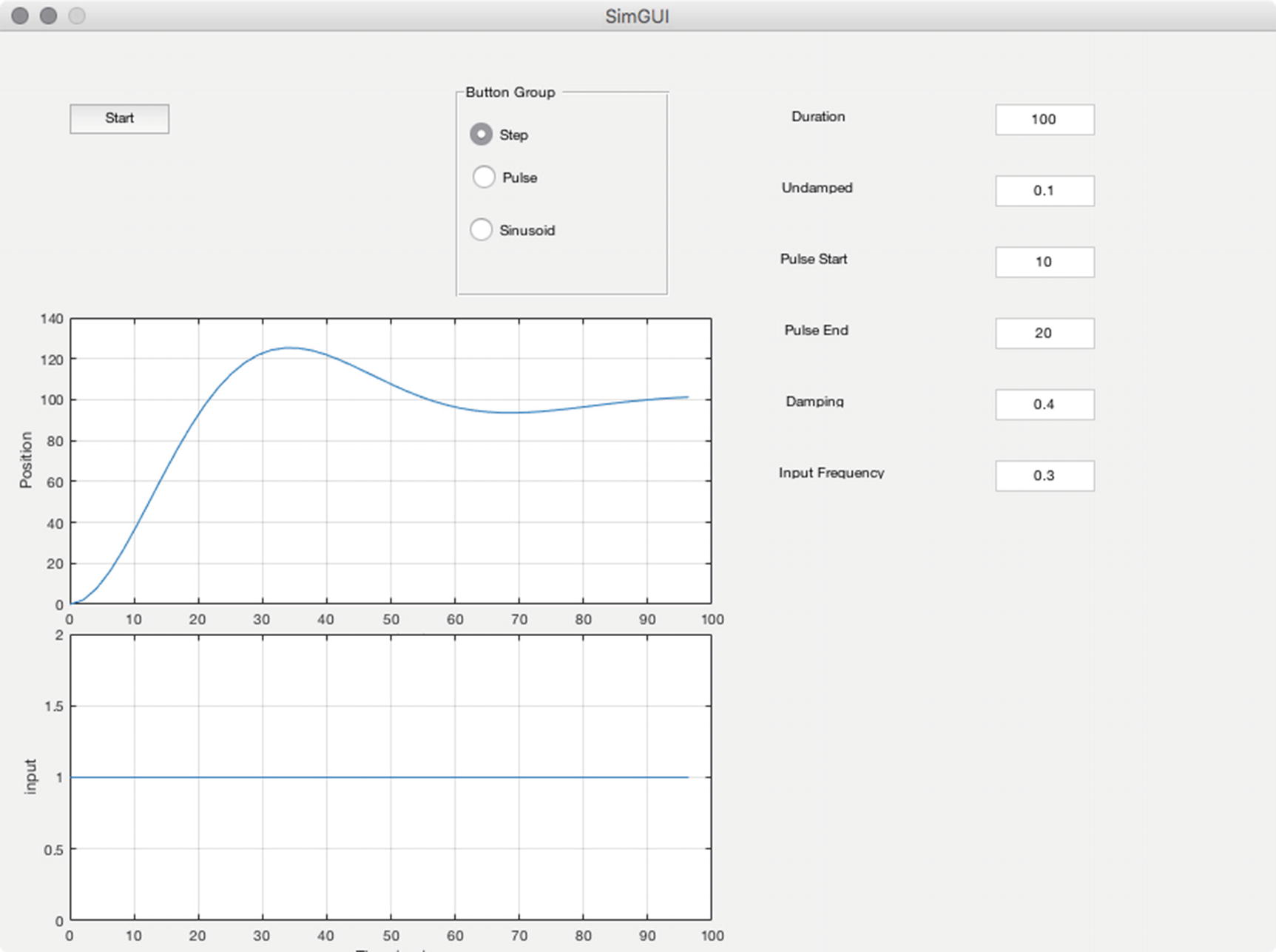

When the start button is pushed we run the simulation and plot the results. This essentially is the same as the demo code in the second-order simulation.

Snapshot of the GUI in simulation.

The callbacks for the edit boxes require a little code to set the data in the stored data. All data are stored in the GUI handles. guidata must be called to store new data in the handles.

One simulation is shown in Figure 3.12. Another simulation in the GUI is shown in Figure 3.13.

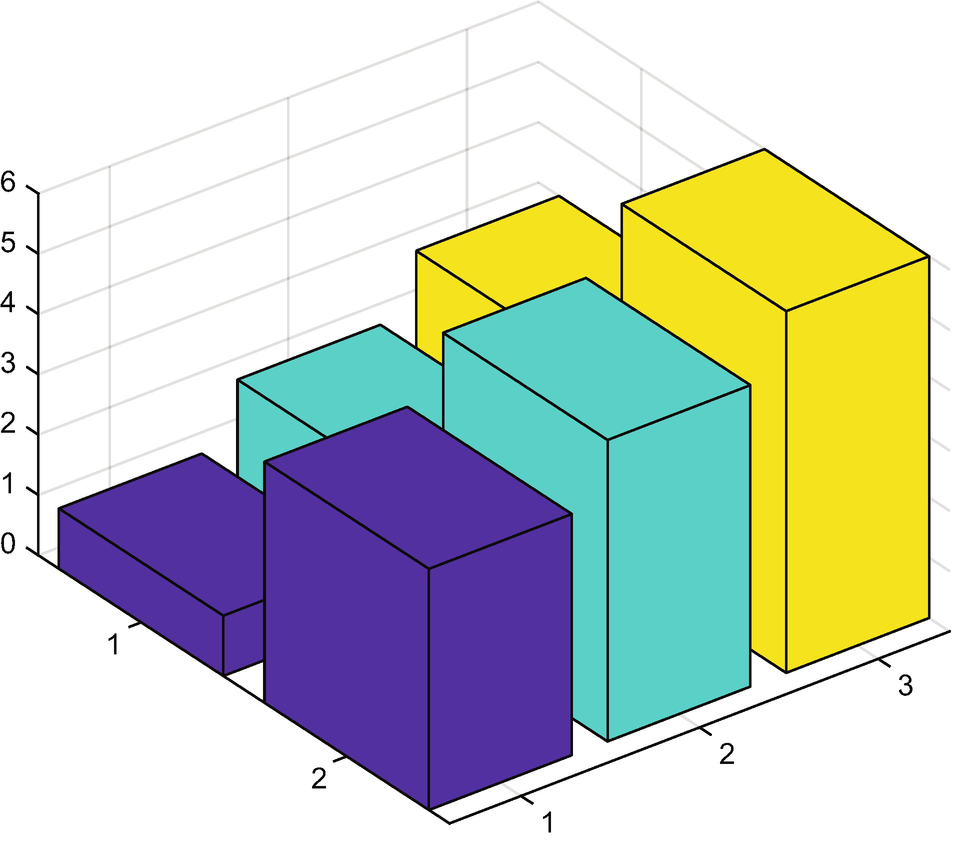

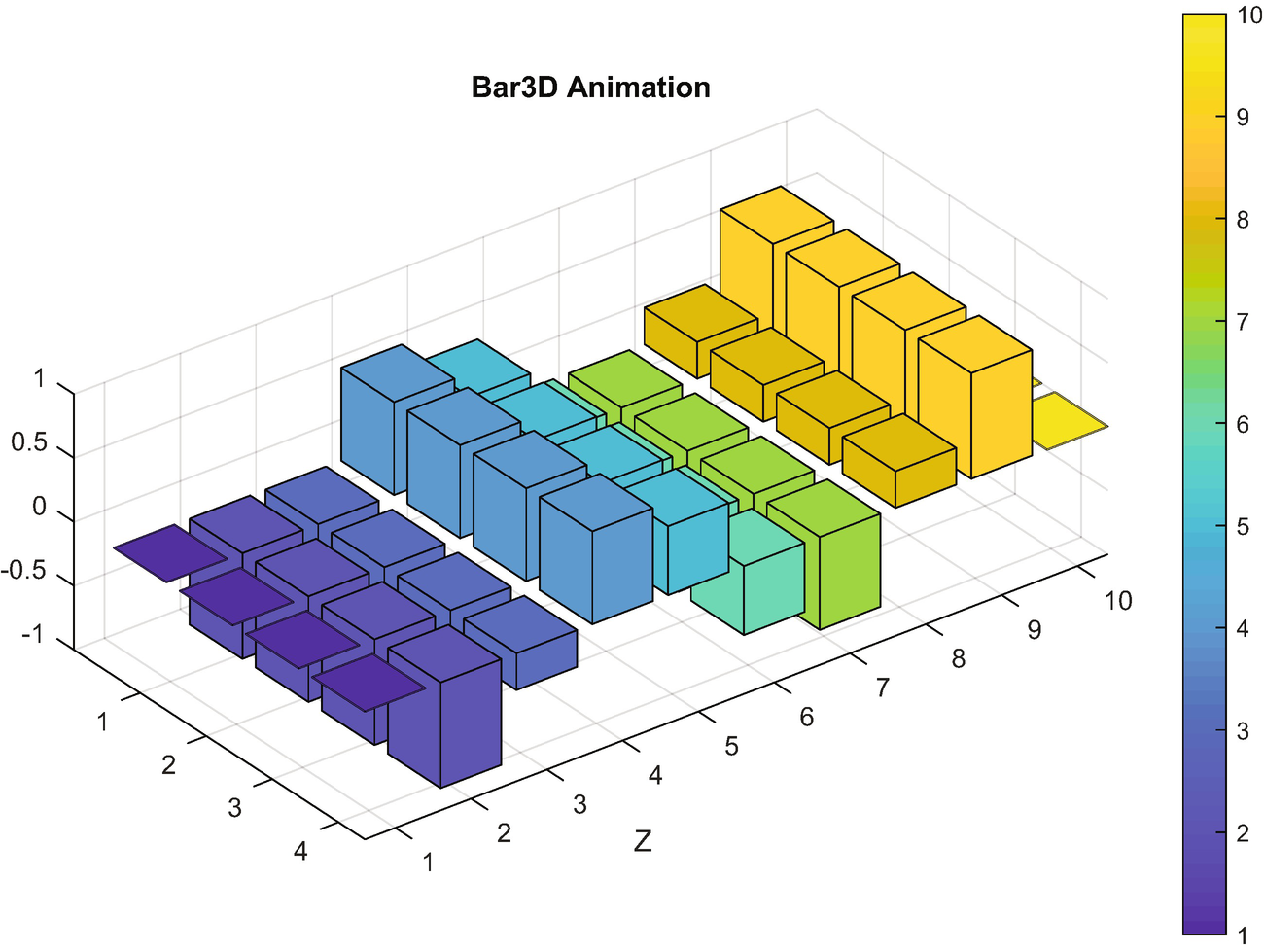

3.8 Animating a Bar Chart

Snapshot of the GUI in simulation.

3.8.1 Problem

We want to animate a 3D bar chart.

3.8.2 Solution

We will write code to animate the MATLAB bar3 function.

3.8.3 How It Works

Our function Bar3D will set up the figure using bar3 and then replace the values for the length of the bars. This is trickier than it sounds.

The following is an example of bar3. We use the handle to get the z data.

We see each column in the array. We will need to replace all four values for each number in m. Look at h. It is length 3. Each column in m has a surface data structure.

Figure 3.14 shows the bar graph.

Two by three bar chart.

Two by three bar chart and the end of the animation.

The figure at the end of the animation is shown in Figure 3.15.

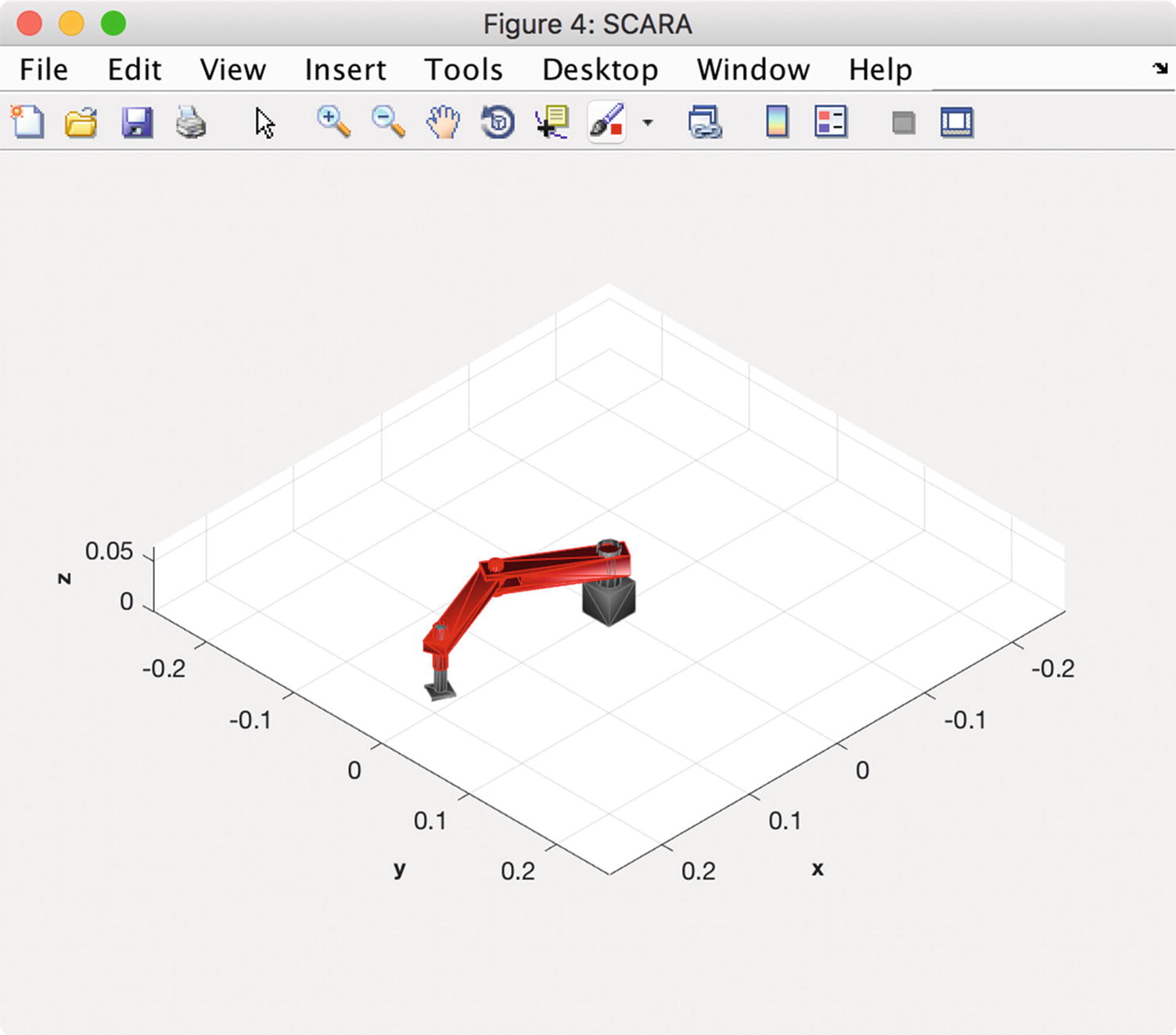

3.9 Drawing a Robot

This section shows the elements of writing graphics code to draw a robot. If you are doing machine learning involving humans or robots, this is a useful code to have. We’ll show how to animate a robot arm.

3.9.1 Problem

We want to animate a robot arm.

3.9.2 Solution

We write code to create vertices and faces for use in the MATLAB patch function.

3.9.3 How It Works

DrawSCARA draws and animates a robot. The first part of the code really just organizes the operation of the function using a switch statement.

Initialize creates the vertex and faces using functions Box, Frustrum and UChannel. These are tedious to write and are geometry-specific. You can apply them to a wide variety of problems, however. You should note that it stores the patches so that we just have to pass in new vertices when animating the arm. The “new” vertices are just the vertices of the arm rotated and translated to match the position of the arm. The arm itself does not deform. We do the computations in the right order so that transformations are passed up/down the chain to get everything moving correctly.

Update updates the arm positions by computing new vertices and passing them to the patches. drawnow draws the arm. We can also save the frames to animate it using MATLAB’s movie functions.

Robot arm generated by DrawSCARA.

3.10 Summary

Chapter Code Listing

File | Description |

|---|---|

Bar3D | 3D bar plots |

Box | Draw a box. |

DrawSCARA | Draw a robot arm. |

DrawVertices | Draw a set of vertices and faces. |

Frustrum | Draw a frustrum (a cone with the top chopped off) |

Globe | Draw a texture-mapped globe. |

PlotSet | 2D line plots. |

SecondOrderSystemSim | Simulates a second-order system. |

SimGUI | Code for the simulation GUI. |

SimGUI.fig | The figure. |

SurfaceOfRevolution | Draw a surface of revolution |

TreeDiagram | Draw a tree diagram. |

TwoDDataDisplay | A script to display two-dimensional data in three-dimensional graphics. |

UChannel | Draw a U shaped channel |