Longitudinal control is the control of an aircraft that needs to work at the altitude and speed changes. In this chapter, we will implement a neural net to produce the critical parameters for a nonlinear aircraft control system. This is an example of online learning and applies techniques from multiple previous chapters.

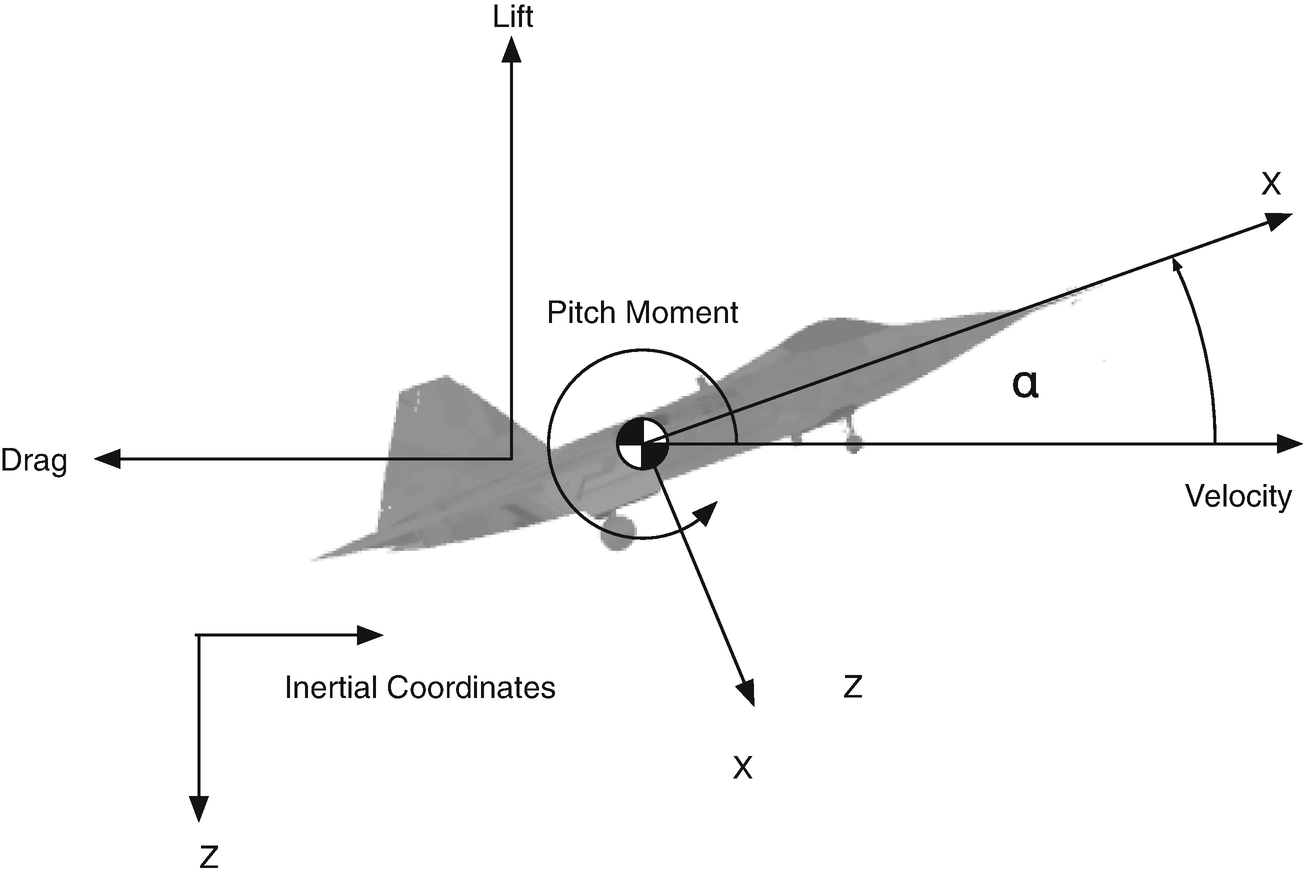

Diagram of an aircraft in flight showing all the important quantities for longitudinal dynamics simulation.

11.1 Longitudinal Motion

- 1.

Model the aircraft dynamics

- 2.

Find an equilibrium solution about which we will control the aircraft

- 3.

Learn how to write a sigma-pi neural net

- 4.

Implement the PID control

- 5.

Implement the neural net

- 6.

Simulate the system

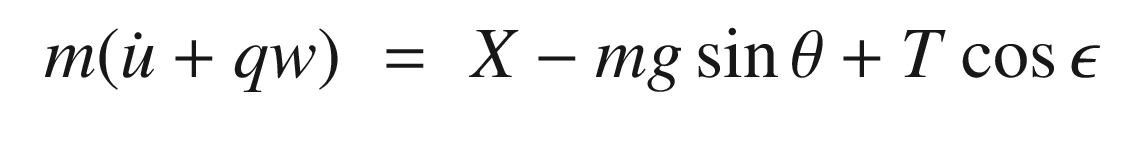

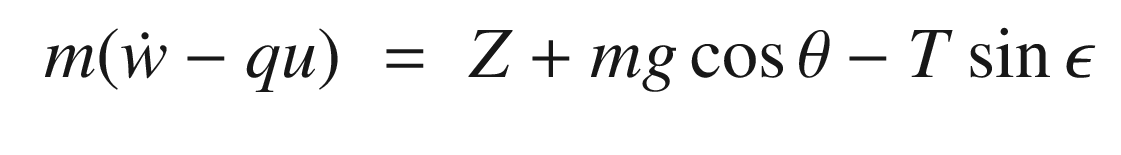

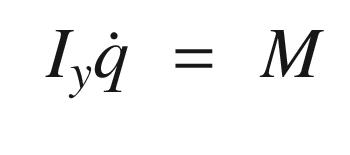

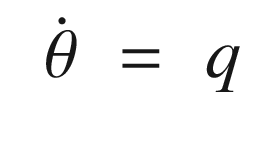

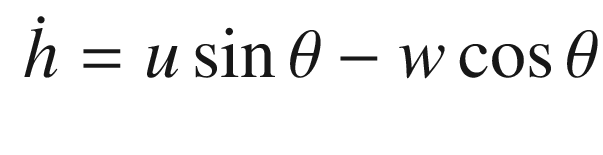

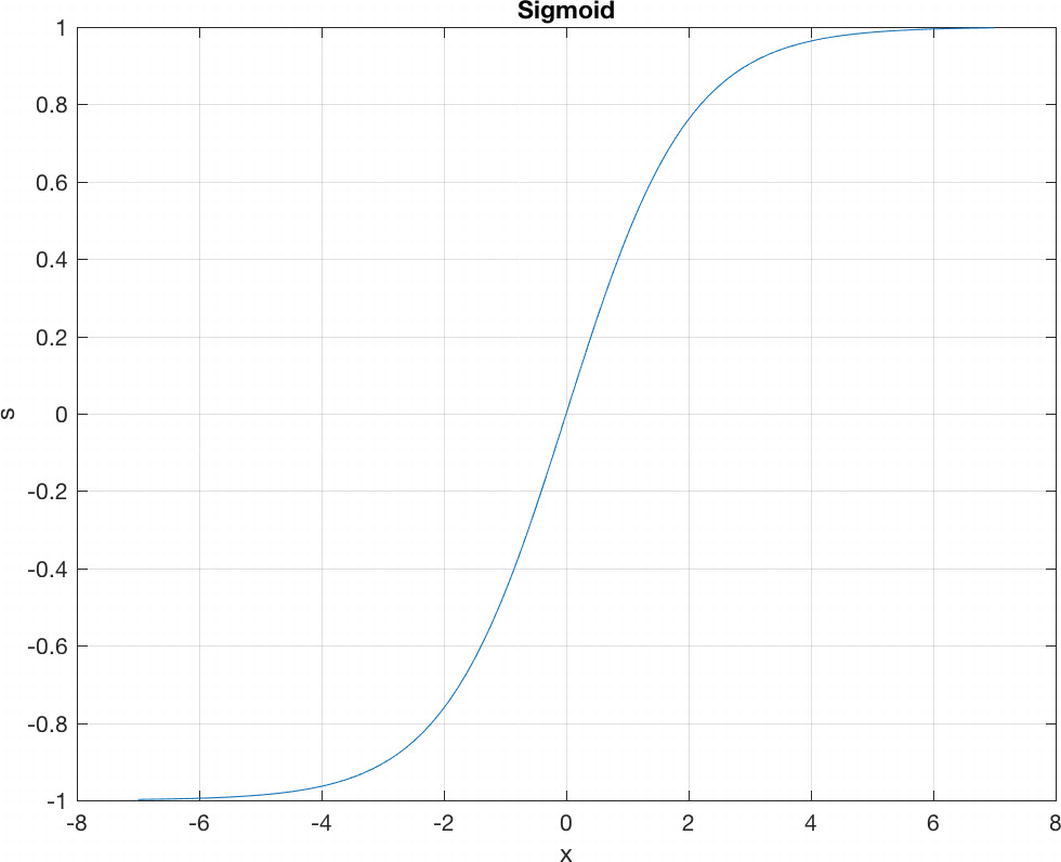

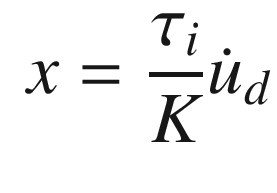

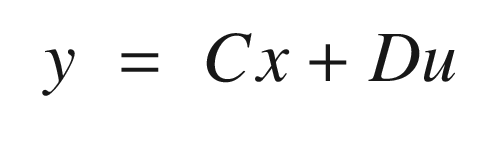

In this recipe, we will model the longitudinal dynamics of an aircraft for use in learning control. We will derive a simple longitudinal dynamics model with a “small” number of parameters. Our control will use nonlinear dynamics inversion with a proportional integral differential (PID) controller to control the pitch dynamics [16, 17]. Learning will be done using a sigma-pi neural network.

- 1.

Commanded aircraft rates from the reference model

- 2.

PID errors

- 3.

Adaptive control rates fed back from the neural network

11.1.1 Problem

We want to model the longitudinal dynamics of an aircraft.

11.1.2 Solution

The solution is to write the right-hand side function for the aircraft longitudinal dynamics differential equations.

11.1.3 How It Works

We summarized the symbols for the dynamical model in Table 11.1

Aircraft Dynamics Symbols

Symbol | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|

g | Acceleration of gravity at sea-level | 9.806 m/s2 |

h | Altitude | m |

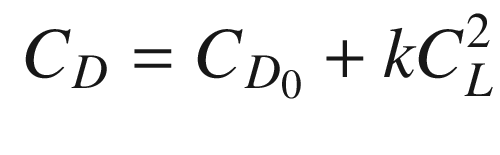

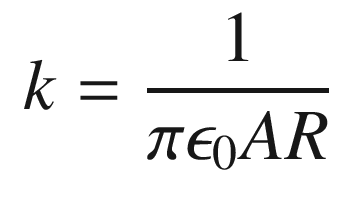

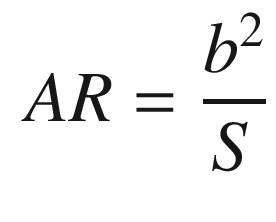

k | Coefficient of lift induced drag | |

m | Mass | kg |

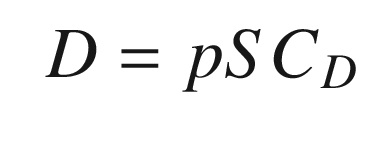

p | Dynamic pressure | N/m2 |

q | Pitch angular rate | rad/s |

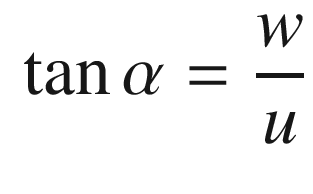

u | x-velocity | m/s |

w | z-velocity | m/s |

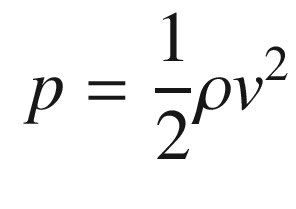

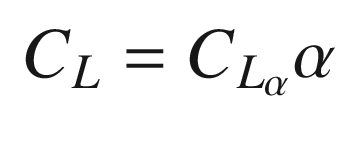

C L | Lift coefficient | |

C D | Drag coefficient | |

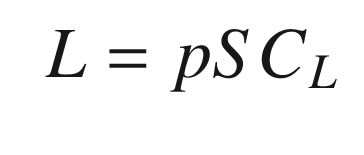

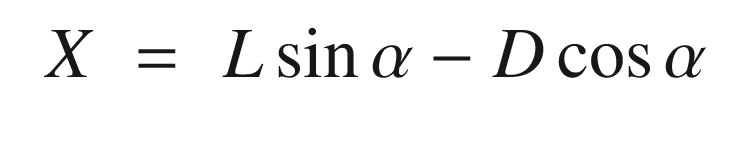

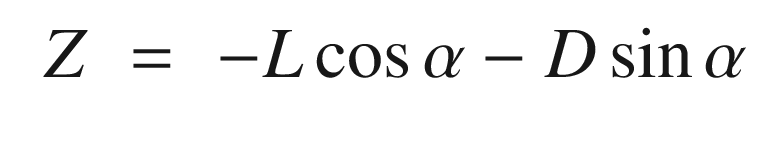

D | Drag | N |

I y | Pitch moment of inertia | kg-m2 |

L | Lift | N |

M | Pitch moment (torque) | Nm |

M e | Pitch moment due to elevator | Nm |

r e | Elevator moment arm | m |

S | Wetted area of wings (the area that contributes to lift and drag) | m2 |

S e | Wetted area of elevator | m2 |

T | Thrust | N |

X | X force in the aircraft frame | N |

Z | Z force in the aircraft frame | N |

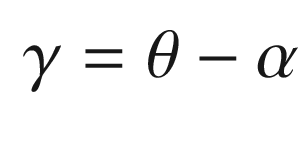

α | Angle of attack | rad |

γ | Flight path angle | rad |

ρ | Air density | kg/m3 |

θ | Pitch angle | rad |

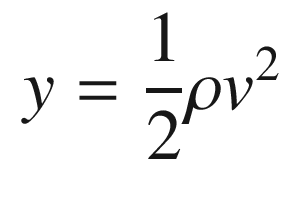

The aerodynamic coefficients are nondimensional coefficients that when multiplied by the wetted area of the aircraft, and the dynamic pressure, produce the aerodynamic forces.

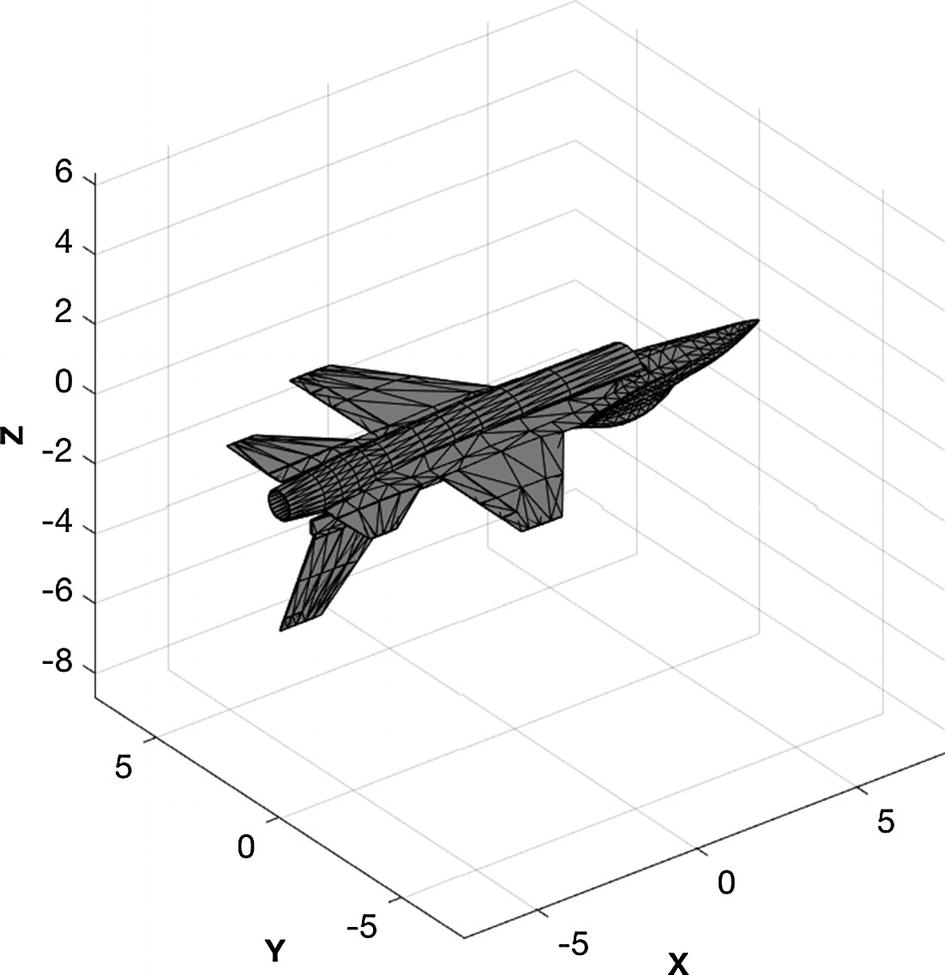

F-16 model.

F-16 Data

Symbol | Field | Value | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cLAlpha | 6.28 | Lift coefficient | |

| cD0 | 0.0175 | Zero lift drag coefficient | |

k | k | 0.1288 | Lift coupling coefficient | |

𝜖 | epsilon | 0 | Thrust angle from the x-axis | rad |

T | thrust | 76.3e3 | Engine thrust | N |

S | s | 27.87 | Wing area | m2 |

m | mass | 12,000 | Aircraft mass | kg |

I y | inertia | 1.7295e5 | z-axis inertia | kg-m2 |

c − cp | c | 1 | Offset of center-of-mass from the center-of-pressure | m |

S e | sE | 3.5 | Elevator area | m2 |

r e | ( rE) | 4.0 | Elevator moment arm | m |

There are many limitations to this model. First of all, the thrust is applied immediately with 100% accuracy. The thrust is also not a function of airspeed or altitude. Real engines take some time to achieve the commanded thrust and the thrust levels change with airspeed and altitude. In the model, the elevator also responds instantaneously. Elevators are driven by motors, usually hydraulic, but sometimes pure electric, and they take time to reach a commanded angle. In our model, the aerodynamics are very simple. In reality, lift and drag are complex functions of airspeed and angle of attack and are usually modeled with large tables of coefficients. We also model the pitching moment by a moment arm. Usually, the torque is modeled by a table. No aerodynamic damping is modeled although this appears in most complete aerodynamic models for aircraft. You can easily add these features by creating functions:

11.2 Numerically Finding Equilibrium

11.2.1 Problem

We want to determine the equilibrium state for the aircraft. This is the orientation at which all forces and torques balance.

11.2.2 Solution

The solution is to compute the Jacobian for the dynamics. The Jacobian is a matrix of all first-order partial derivatives of a vector valued function, in this case the dynamics of the aircraft.

11.2.3 How It Works

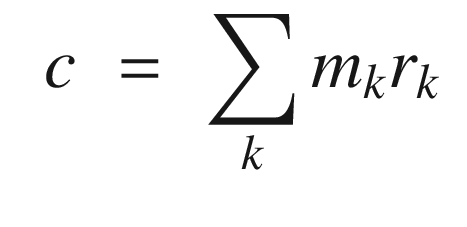

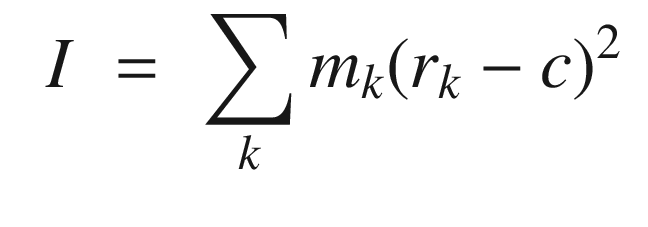

CostFun is the cost functional given below.

The vector of values is the first input. Our first guess is that thrust equals drag. The vertical velocity and thrust are solved for by fminsearch. fminsearch searches over thrust and vertical velocity to find an equilibrium state.

The results of the demo are:

The initial and final costs show how successful fminsearch was in achieving the objective of minimizing the w and u accelerations.

11.3 Numerical Simulation of the Aircraft

11.3.1 Problem

We want to simulate the aircraft.

11.3.2 Solution

The solution is to create a script that calls the right-hand side of the dynamical equations, RHSAircraft in a loop, and plot the results.

11.3.3 How It Works

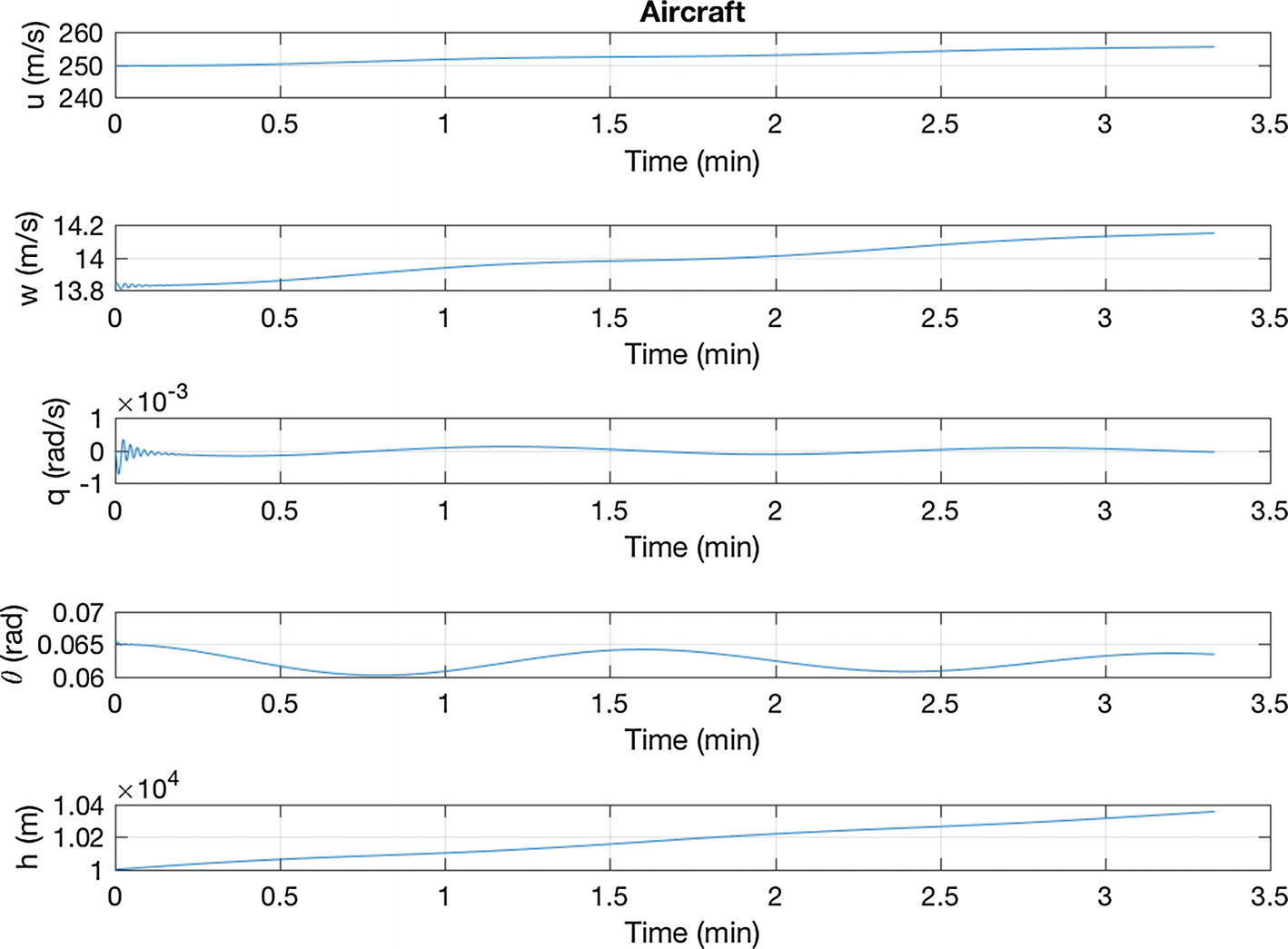

The simulation script is shown below. It computes the equilibrium state, then simulates the dynamics in a loop by calling RungeKutta. It applies a disturbance to the aircraft. It then uses PlotSet to plot the results.

The applied external acceleration puts the aircraft into a slight climb with some noticeable oscillations.

Open loop response to a pulse for the F-16 in a shallow climb.

11.4 Activation Function

11.4.1 Problem

We are going to implement a neural net so that our aircraft control system can learn. We need an activation function to scale and limit measurements.

11.4.2 Solution

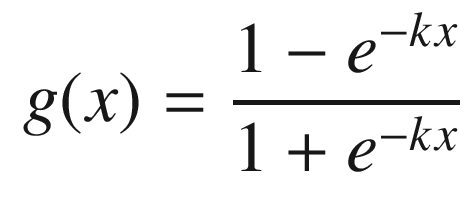

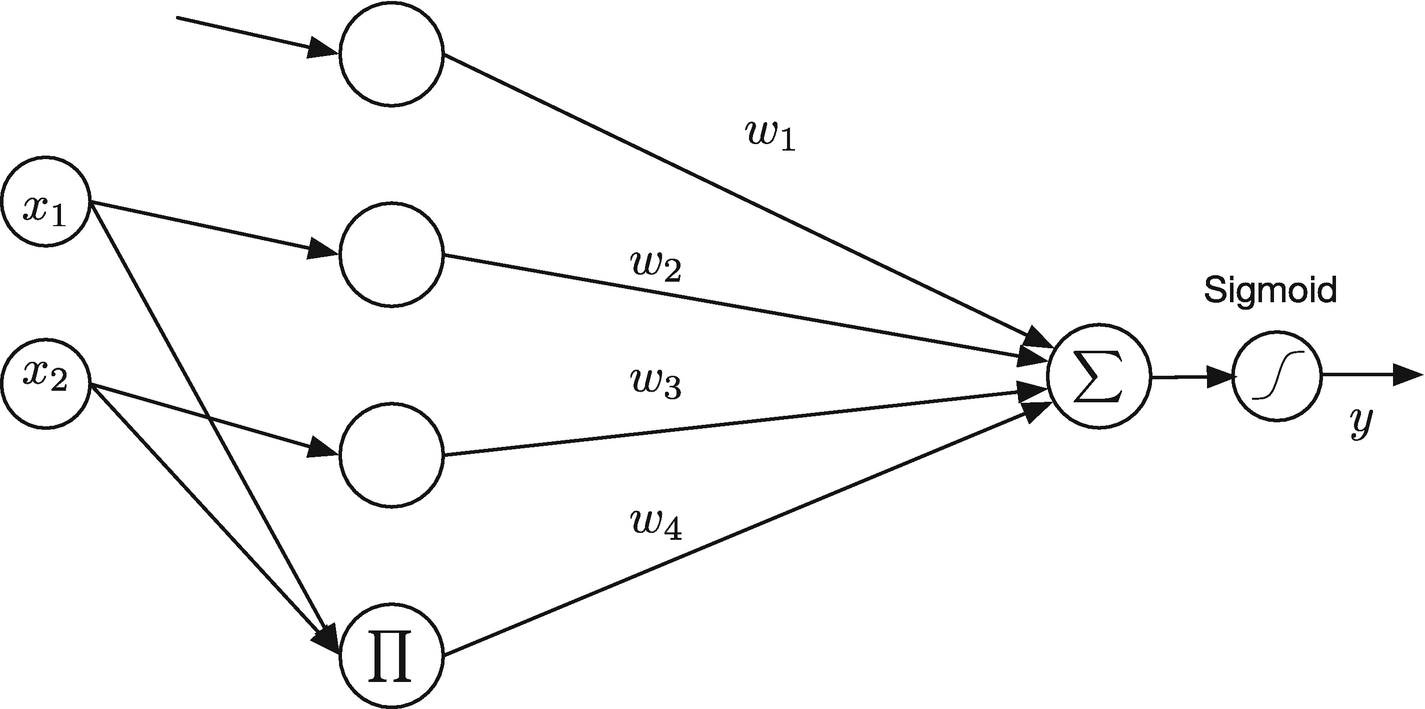

Use a sigmoid function as our activation function.

11.4.3 How It Works

The sigmoid function with k = 1 is plotted in the following script.

Sigmoid function. At large values of x, the sigmoid function returns ± 1.

11.5 Neural Net for Learning Control

11.5.1 Problem

We want to use a neural net to add learning to the aircraft control system.

11.5.2 Solution

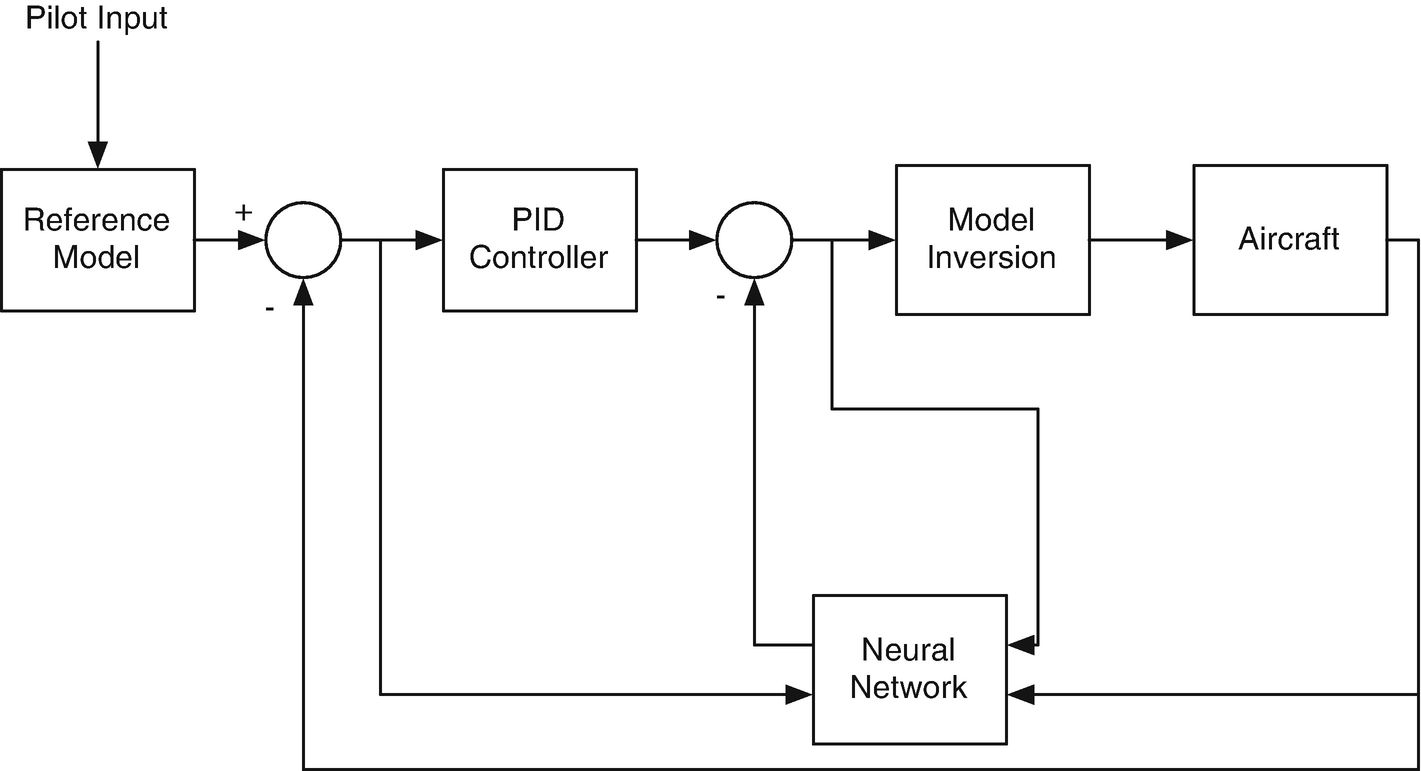

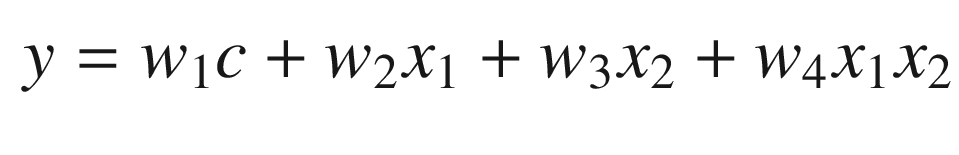

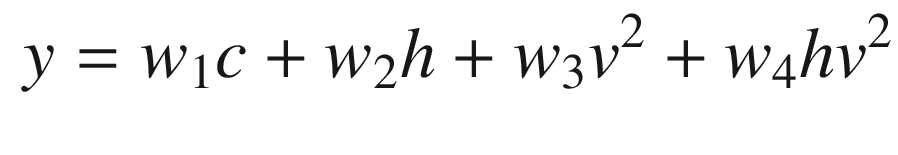

Use a sigma-pi neural net function. A sigma-pi neural net sums the inputs and products of the inputs to produce a model.

11.5.3 How It Works

Aircraft control system. It combines a PID controller with dynamic inversion to handle nonlinearities. A neural net provides learning.

Sigma-pi neural net. Π stands for product and Σ stands for sum.

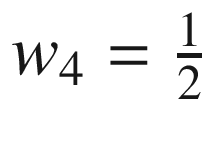

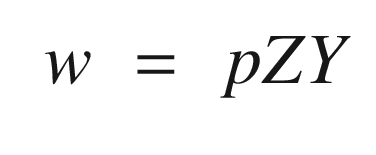

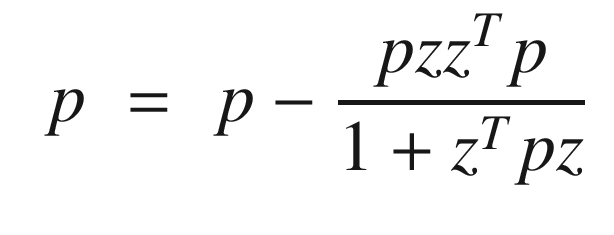

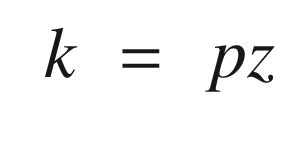

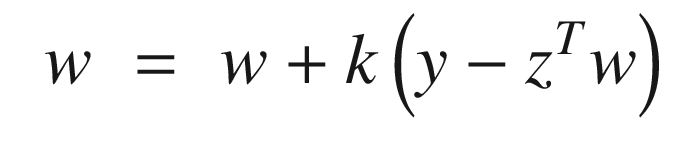

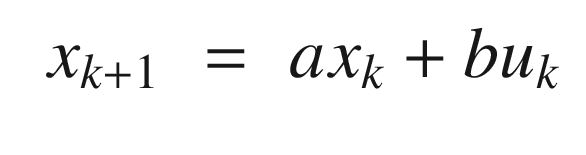

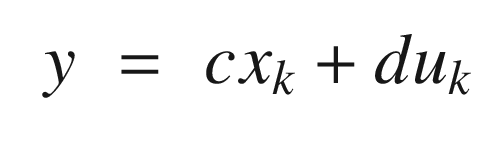

and all other weights to zero. Suppose we didn’t know the constant

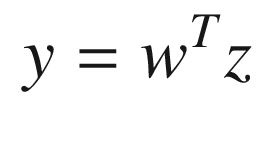

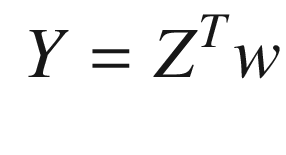

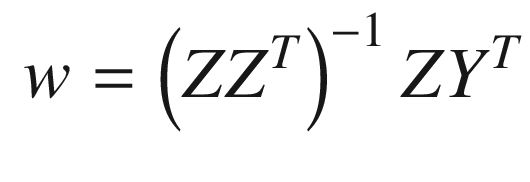

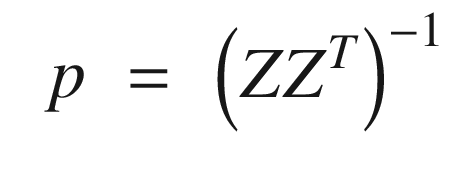

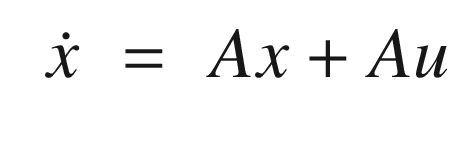

and all other weights to zero. Suppose we didn’t know the constant  . We would like our neural net to determine the weight through measurements. Learning for a neural net means determining the weights so that our net replicates the function it is modeling. Define the vector z, which is the result of the product operations. In our two-input case this would be:

. We would like our neural net to determine the weight through measurements. Learning for a neural net means determining the weights so that our net replicates the function it is modeling. Define the vector z, which is the result of the product operations. In our two-input case this would be: ![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} z = \left[ \begin{array}{l} c\\ x_1\\ x_2\\ x_1x_2 \end{array} \right] \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_11_Chapter/420697_2_En_11_Chapter_TeX_Equ26.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \left[ \begin{array}{lll} y_1&y_2&\cdots \end{array} \right] = w^T\left[ \begin{array}{lll} z_1&z_2&\cdots \end{array} \right] \end{aligned} $$](../images/420697_2_En_11_Chapter/420697_2_En_11_Chapter_TeX_Equ28.png)

As you can see, they all agree! This is a good way to initially train your neural net. Collect as many measurements as you have values of z and compute the weights. Your net is then ready to go.

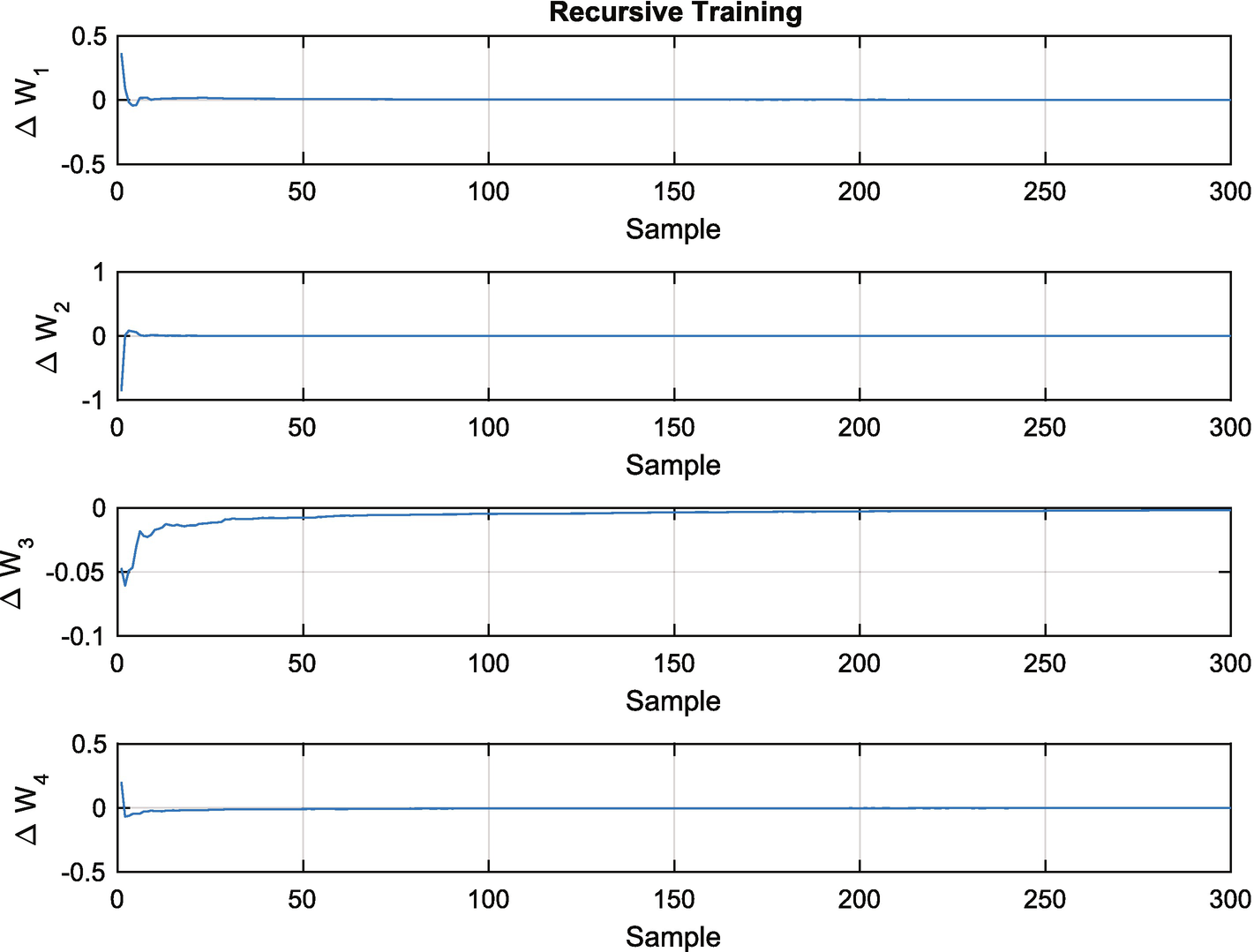

Recursive training or learning. After an initial transient the weights converge quickly.

You will notice that the recursive learning algorithm is identical in form to the Kalman Filter given in Section 4.1.3. Our learning algorithm was derived from batch least squares, which is an alternative derivation for the Kalman Filter.

11.6 Enumeration of All Sets of Inputs

11.6.1 Problem

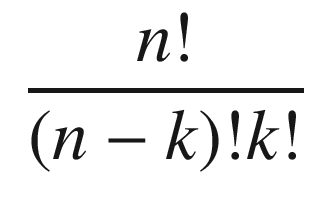

One issue with a sigma-pi neural network is the number of possible nodes. For design purposes, we need a function to enumerate all possible sets of combinations of inputs. This is to determine the limitation of the complexity of a sigma-pi neural network.

11.6.2 Solution

Write a combination function that computes the number of sets.

11.6.3 How It Works

The code to enumerate all sets is in the function Combinations.

This handles two special cases on input and then calls itself recursively for all other cases. Here are some examples:

You can see that if we have four inputs and want all possible combinations, we end up with 14 in total! This indicates a practical limit to a sigma-pi neural network, as the number of weights will grow fast as the number of inputs increases.

11.7 Write a Sigma-Pi Neural Net Function

11.7.1 Problem

We need a sigma-pi net function for general problems.

11.7.2 Solution

Use a sigma-pi function.

11.7.3 How It Works

- 1.

“initialize” – initialize the function

- 2.

“set constant” – set the constant term

- 3.

“batch learning” – perform batch learning

- 4.

“recursive learning” – perform recursive learning

- 5.

“output” – generate outputs without training

The functionality is distributed among sub-functions called from the switch statement.

We first get a default data structure. Then we initialize the filter with an empty x. We then get the initial weights by using batch learning. The number of columns of x should be at least twice the number of inputs. This gives a starting p matrix and initial estimate of weights. We then perform recursive learning. It is important that the field kSigmoid is small enough so that valid inputs are in the linear region of the sigmoid function. Note that this can be an array so that you can use different scalings on different inputs.

The batch results are as follows for five examples of dynamic pressures at low altitude. As you can see the truth model and neural net outputs are quite close:

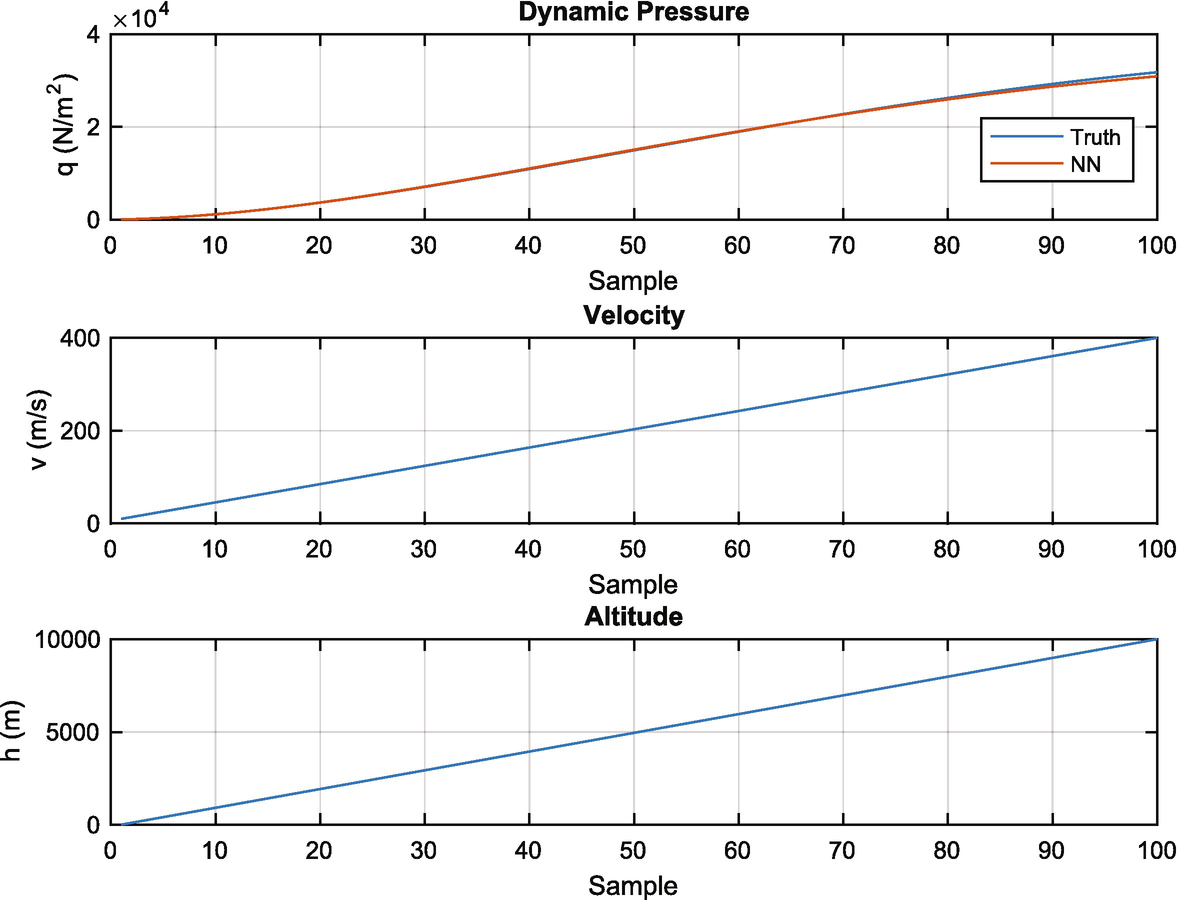

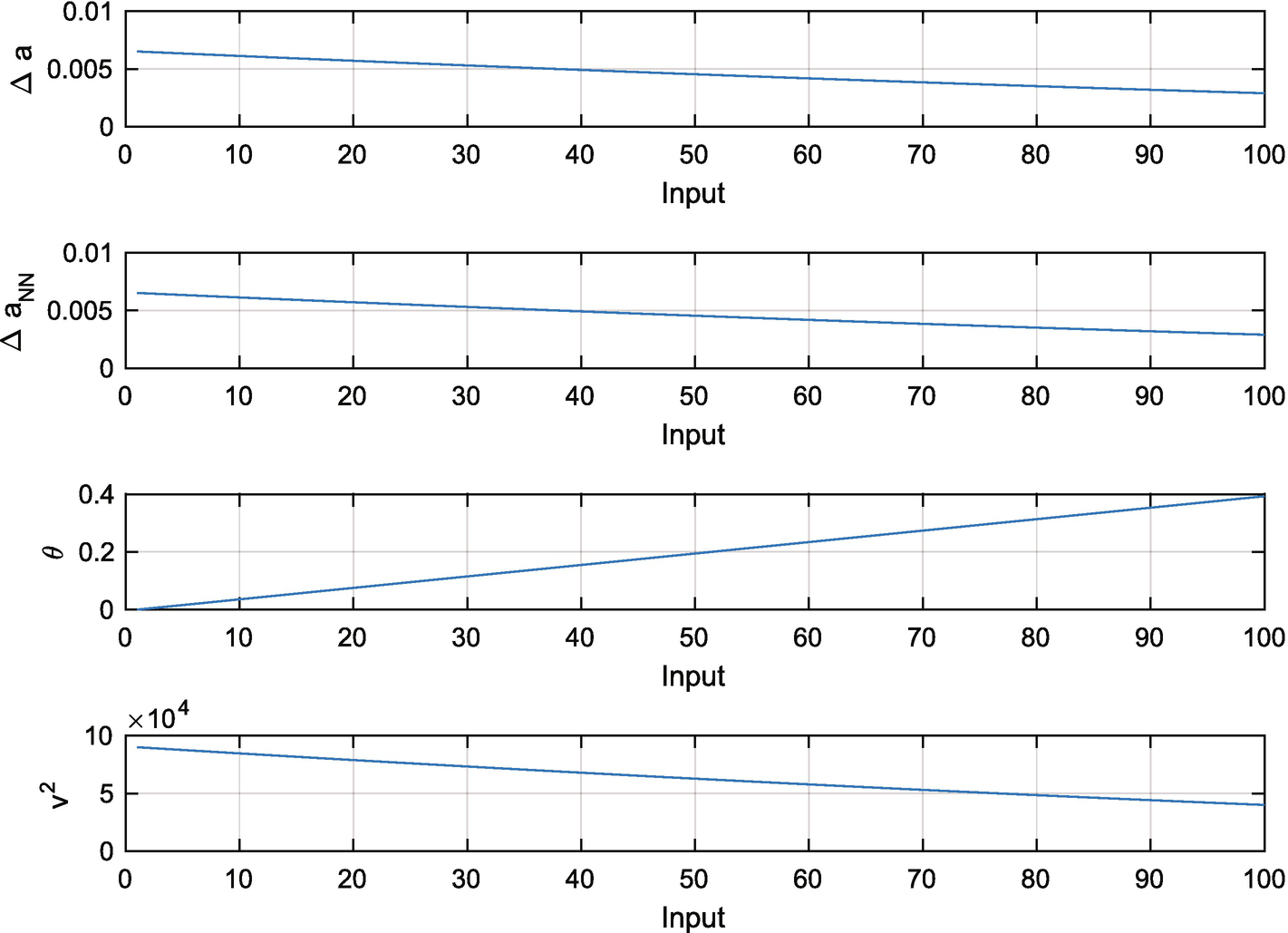

The recursive learning results are shown in Figure 11.8. The results are pretty good over a wide range of altitudes. You could then just use the “update” action during aircraft operation.

11.8 Implement PID Control

11.8.1 Problem

We want a PID controller to control the aircraft.

11.8.2 Solution

Recursive training for the dynamic pressure example.

11.8.3 How It Works

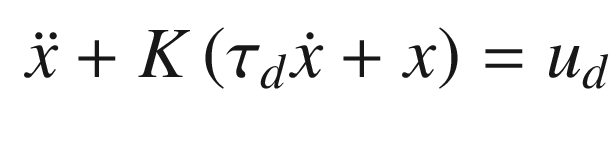

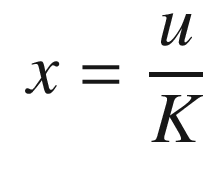

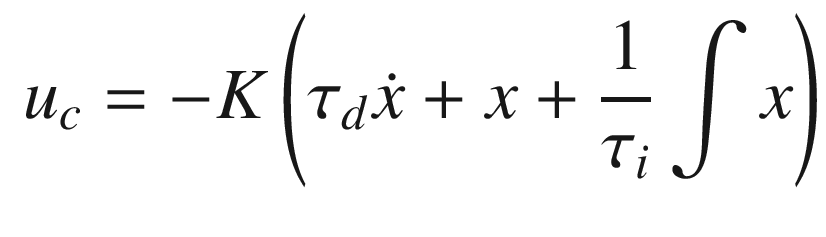

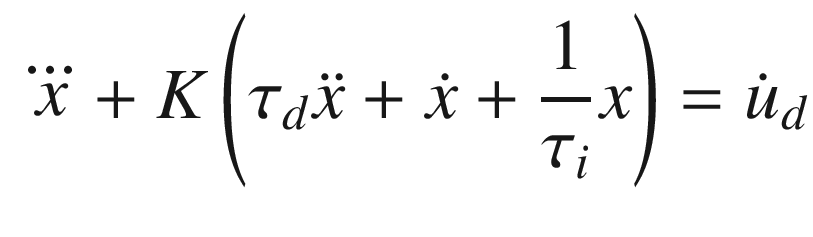

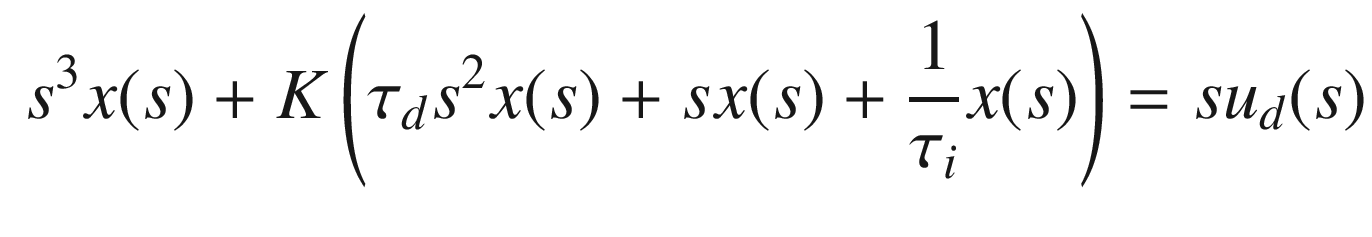

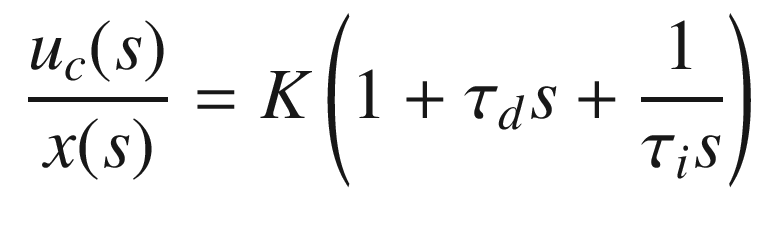

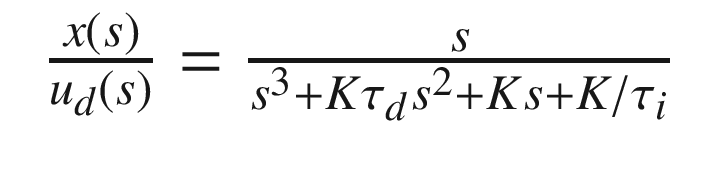

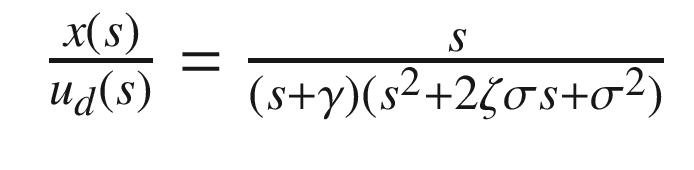

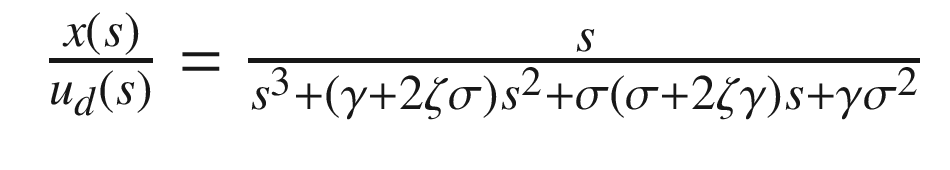

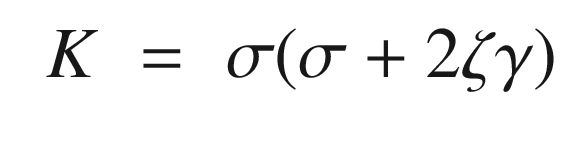

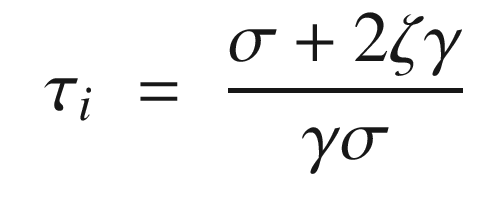

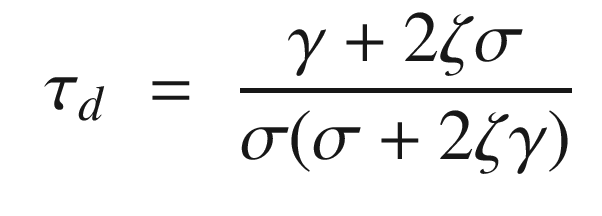

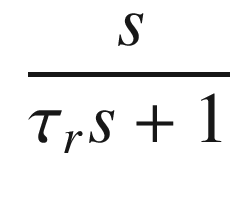

. The closed loop transfer function is:

. The closed loop transfer function is:

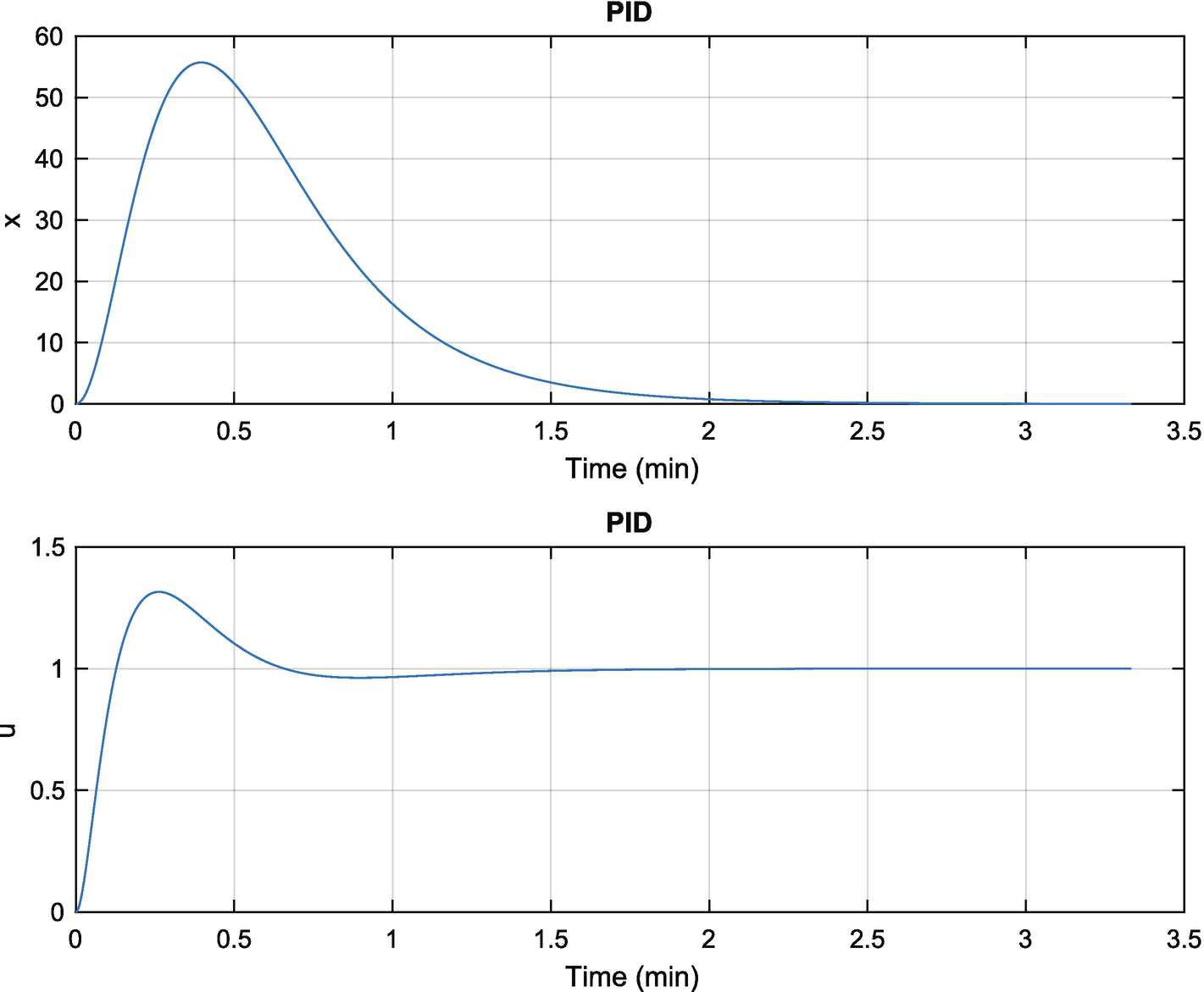

Proportional integral derivative control given a unit input.

It takes about 2 minutes to drive x to zero, which is close to the 100 seconds specified for the integrator.

11.9 PID Control of Pitch

11.9.1 Problem

We want to control the pitch angle of an aircraft with a PID controller.

11.9.2 Solution

Write a script to implement the controller with the PID controller and pitch dynamic inversion compensation.

11.9.3 How It Works

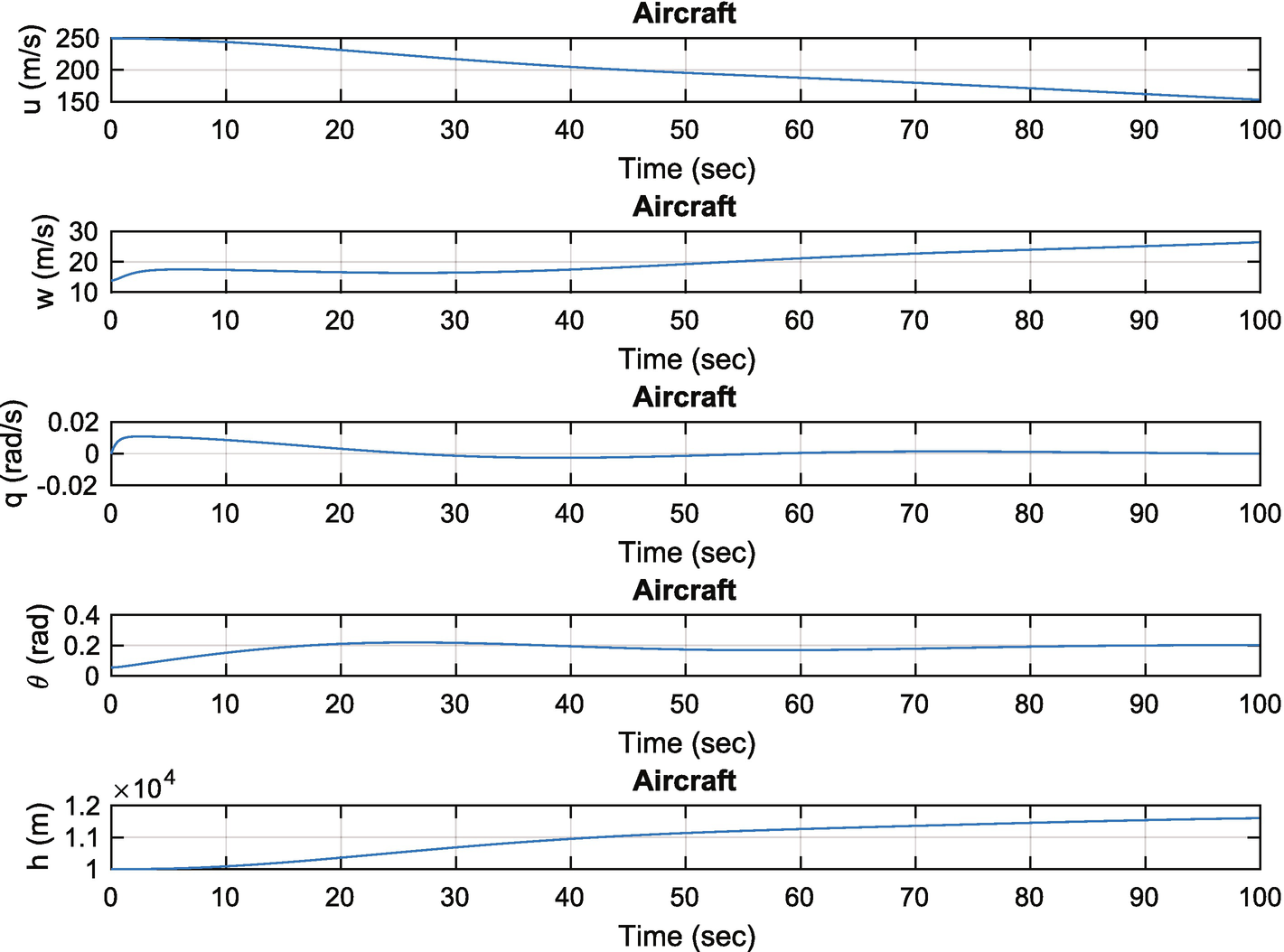

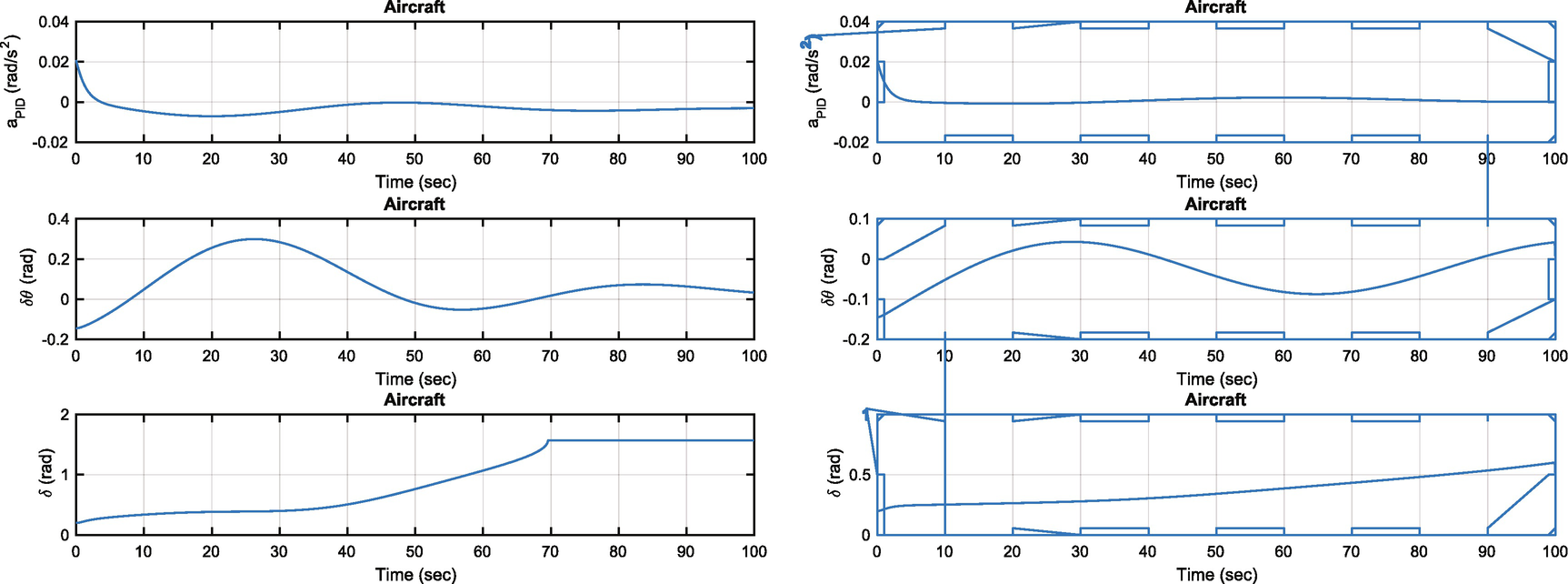

The PID controller changes the elevator angle to produce a pitch acceleration to rotate the aircraft. The elevator is the moveable horizontal surface that is usually on the tail wing of an aircraft. In addition, additional elevator movement is needed to compensate for changes in the accelerations due to lift and drag as the aircraft changes its pitch orientation. This is done using the pitch dynamic inversion function. This returns the pitch acceleration, which must be compensated for when applying the pitch control.

Aircraft pitch angle change. The aircraft oscillates because of the pitch dynamics.

The maneuver increases the drag and we don’t adjust the throttle to compensate. This will cause the airspeed to drop. In implementing the controller we neglected to consider coupling between states, but this can be added easily.

11.10 Neural Net for Pitch Dynamics

11.10.1 Problem

We want a nonlinear inversion controller with a PID controller and the sigma-pi neural net.

11.10.2 Solution

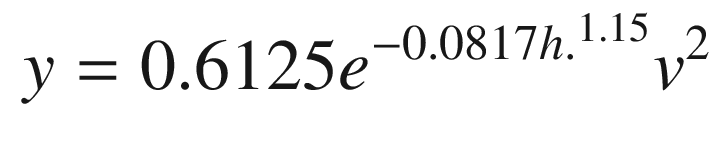

Train the neural net with a script that takes the angle and velocity squared input and computes the pitch acceleration error.

11.10.3 How It Works

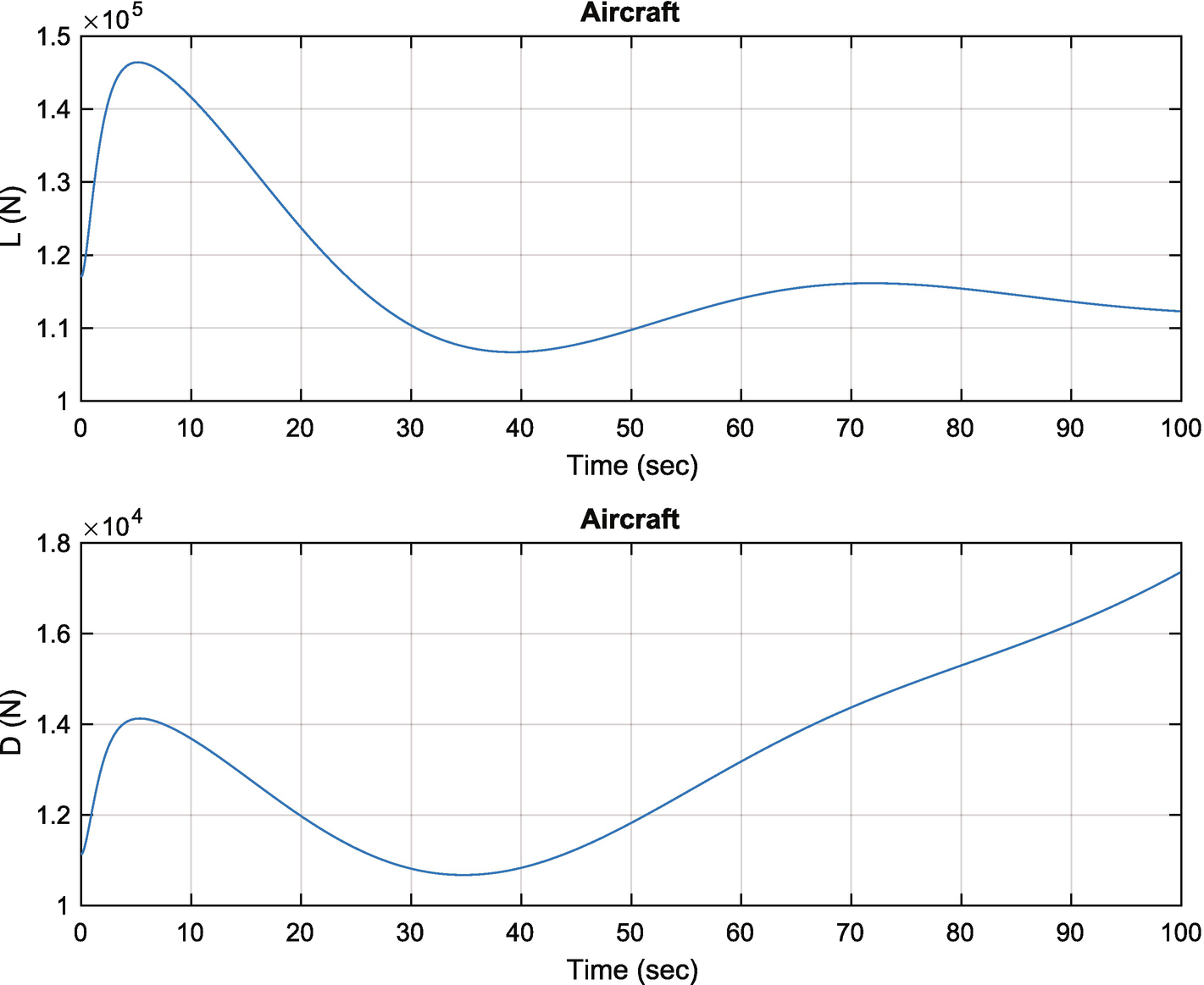

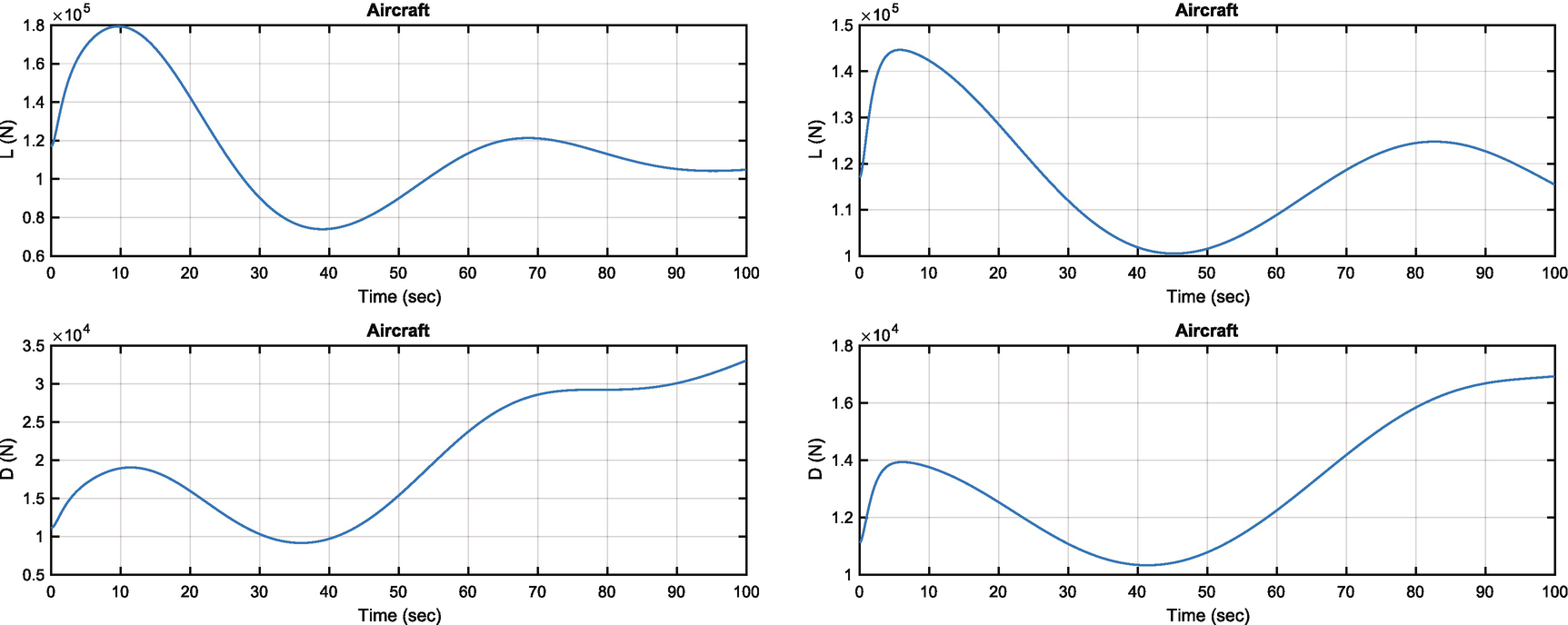

Aircraft pitch angle change. Notice the changes in lift and drag with angle.

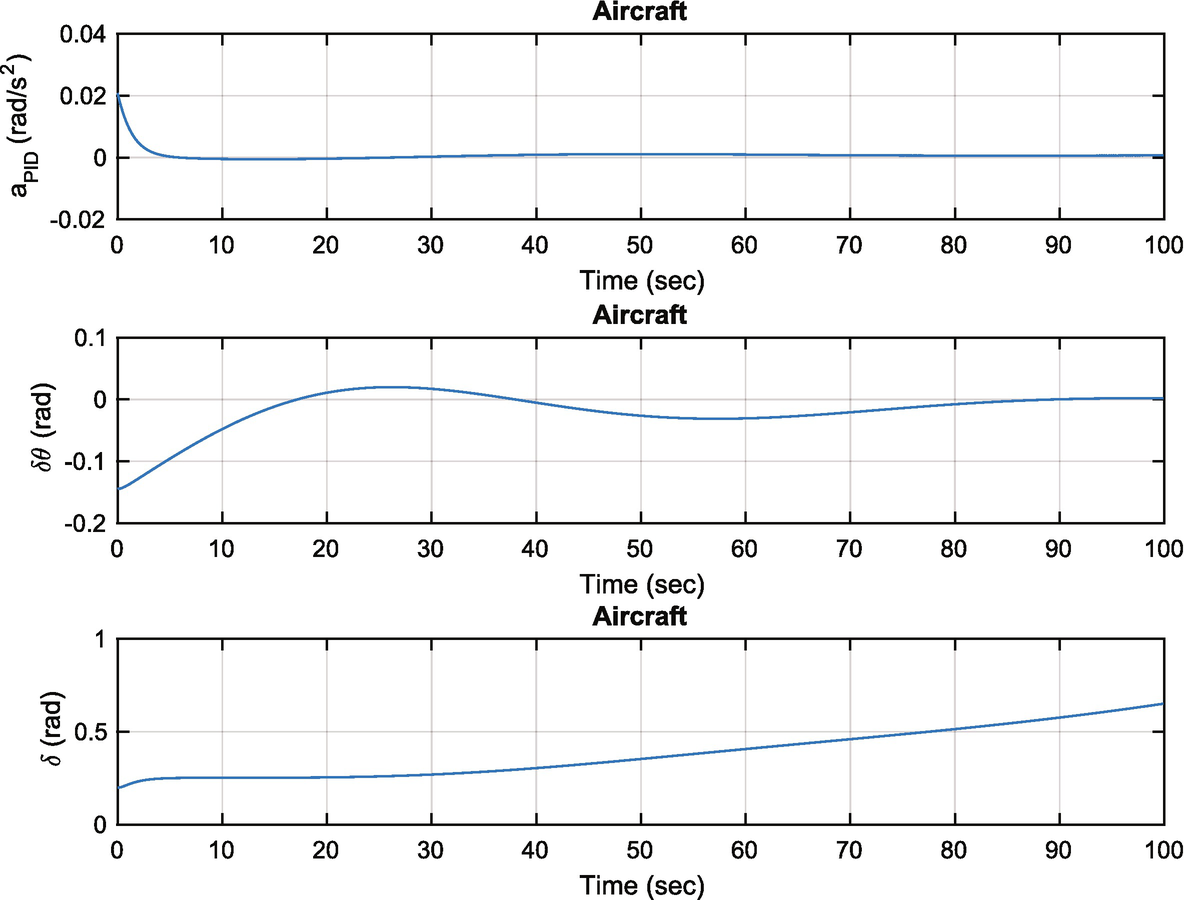

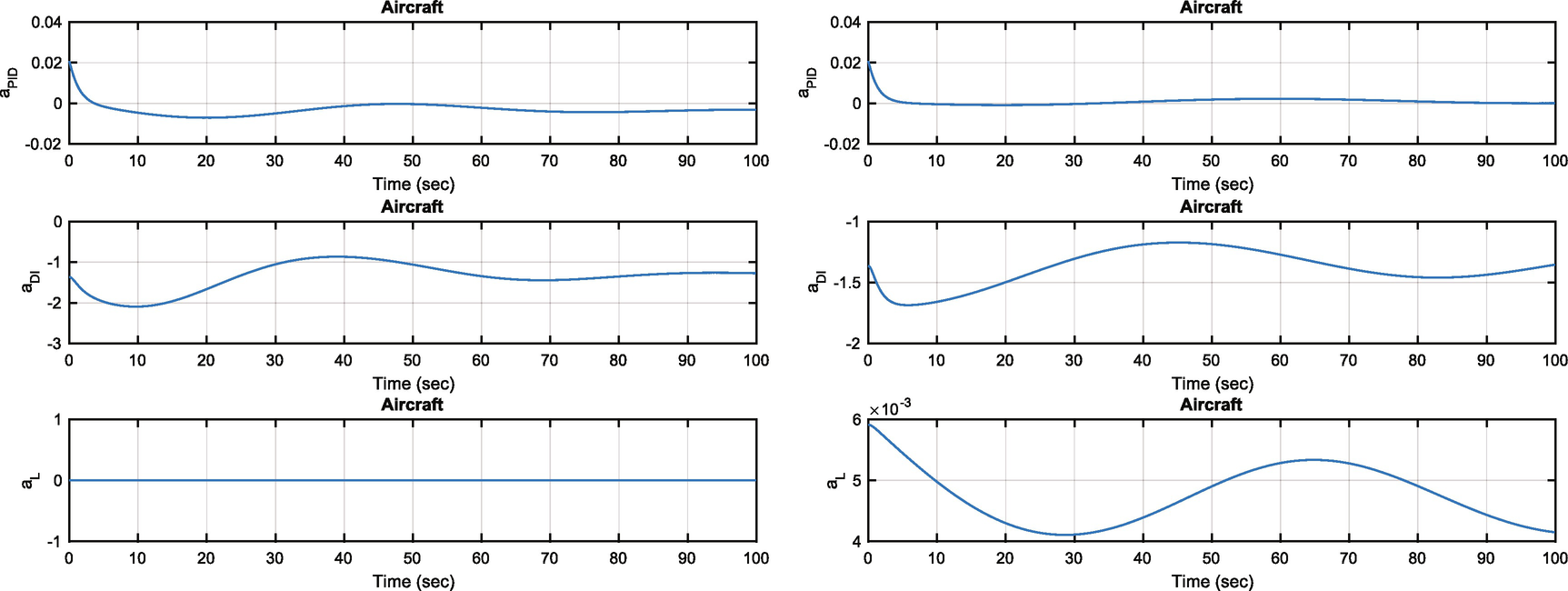

Aircraft pitch angle change. The PID acceleration is much lower than the pitch inversion acceleration.

The script first finds the equilibrium state using EquilibriumState. It then sets up the sigma-pi neural net using SigmaPiNeuralNet. PitchDynamicInversion is called twice, once to get the model aircraft acceleration aM (the way we want the aircraft to behave) and once to get the true acceleration aT. The delta acceleration, dA is used to train the neural net. The neural net produces aNN. The resulting weights are saved in a .mat file for use in AircraftSim. The simulation uses dRHS, but our pitch acceleration model uses dRHSL. The latter is saved in another .mat file.

As can be seen, the neural net reproduces the model very well. The script also outputs DNN. mat, which contains the trained neural net data.

11.11 Nonlinear Simulation

11.11.1 Problem

Neural net fitted to the delta acceleration.

11.11.2 Solution

Enable the control functions to the simulation script described in AircraftSimOpenLoop.

11.11.3 How It Works

Aircraft pitch angle change. Lift and drag variations are shown.

Aircraft pitch angle change. Without learning control, the elevator saturates.

Aircraft pitch angle change. The PID acceleration is much lower than the pitch dynamic inversion acceleration.

Learning control helps the performance of the controller. However, the weights are fixed throughout the simulation. Learning occurs prior to the controller becoming active. The control system is still sensitive to parameter changes since the learning part of the control was computed for a pre-determined trajectory. Our weights were determined only as a function of pitch angle and velocity squared. Additional inputs would improve the performance. There are many opportunities for you to try to expand and improve the learning system.

11.12 Summary

Chapter Code Listing

File | Description |

|---|---|

AircraftSim | Simulation of the longitudinal dynamics of an aircraft. |

AtmDensity | Atmospheric density using a modified exponential model. |

EquilibriumState | Finds the equilibrium state for an aircraft. |

PID | Implements a PID controller. |

PitchDynamicInversion | Pitch angular acceleration. |

PitchNeuralNetTraining | Train the pitch acceleration neural net. |

QCR | Generates a full state feedback controller. |

RecursiveLearning | Demonstrates recursive neural net training or learning. |

RHSAircraft | Right-hand side for aircraft longitudinal dynamics. |

SigmaPiNeuralNet | Implements a sigma-pi neural net. |

Sigmoid | Plots a sigmoid function. |