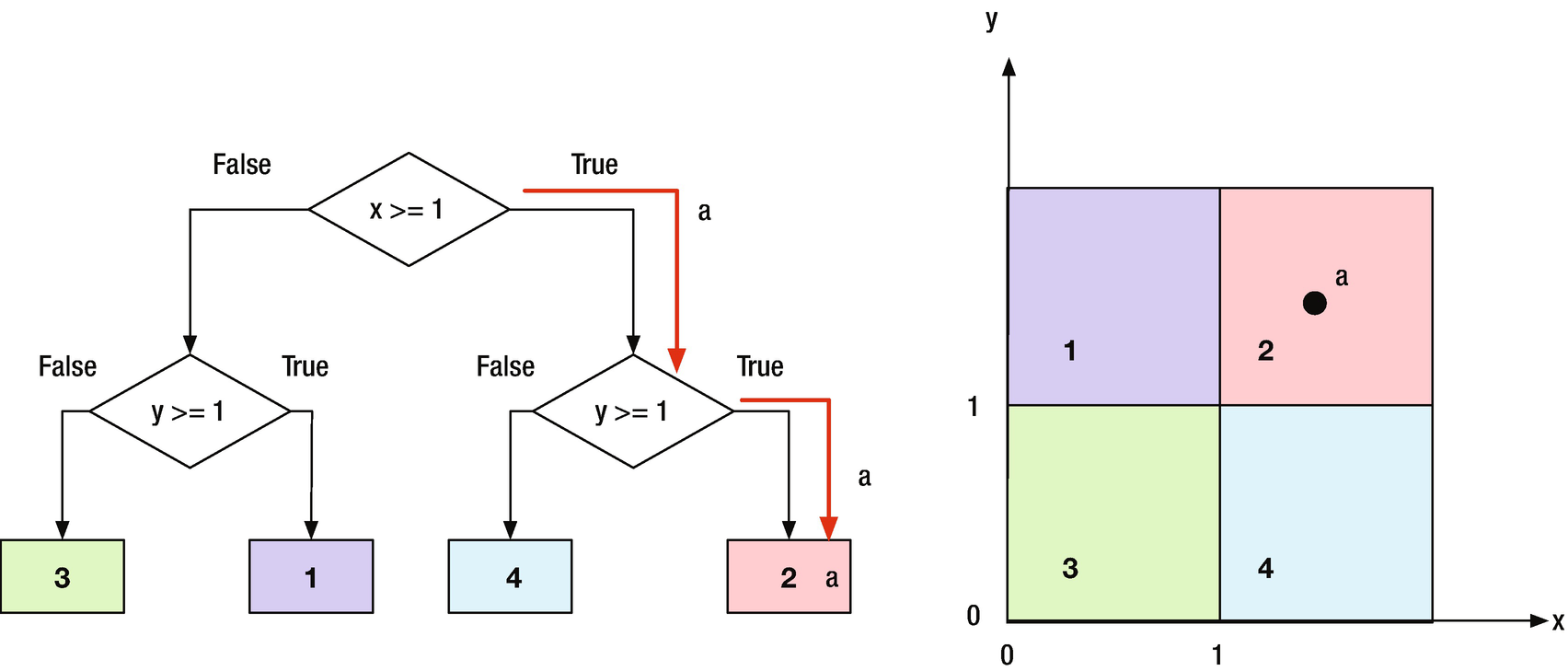

In this chapter, we will develop the theory for binary decision trees. Decision trees can be used to classify data, and fall into the Learning category in our Autonomous Learning taxonomy. Binary trees are easiest to implement because each node branches to two other nodes, or none. We will create functions for the Decision Trees and to generate sets of data to classify. Figure 7.1 shows a simple binary tree. Point “a” is in the upper left quadrant. The first binary test finds that its x value is greater than 1. The next test finds that its y value is greater than 1 and puts it in set 2. Although the boundaries show square regions, the binary tree really tests for regions that go to infinity in both x and y.

A simple binary tree with one point to classify.

For classification, we are assuming that we can make a series of binary decisions to classify something. If we can, we can implement the reasoning in a binary tree.

7.1 Generate Test Data

7.1.1 Problem

We want to generate a set of training and testing data for classification.

7.1.2 Solution

Write a function using rand to generate data over a selected range in two dimensions, x and y.

7.1.3 How It Works

The function ClassifierSet generates random data and assigns them to classes. The function call is:

The first argument to ClassifierSets is the square root of the number of points. The second, xRange, gives the x range for the data and the third, yRange, gives the y range. The n 2 points will be placed randomly in this region. The next argument is a cell array with the names of the sets, name. These are used for plot labels. The remaining inputs are a list of vertices, v, and the faces, f. The faces select the vertices to use in each polygon. The faces connect the vertices into specific polygons. f is a cell array, since each face array can be of any length. A triangle has a length of 3, a hexagon a length of 6. Triangles, rectangles, and hexagons can be easily meshed so that there are no gaps.

Classes are defined by adding polygons that divide the data into regions. Any polygon can be used. You should pick polygons so that there are no gaps. Rectangles are easy, but you could also use uniformly sized hexagons. The following code is the built-in demo. The demo is the last subfunction in the function. This specifies the vertices and faces.

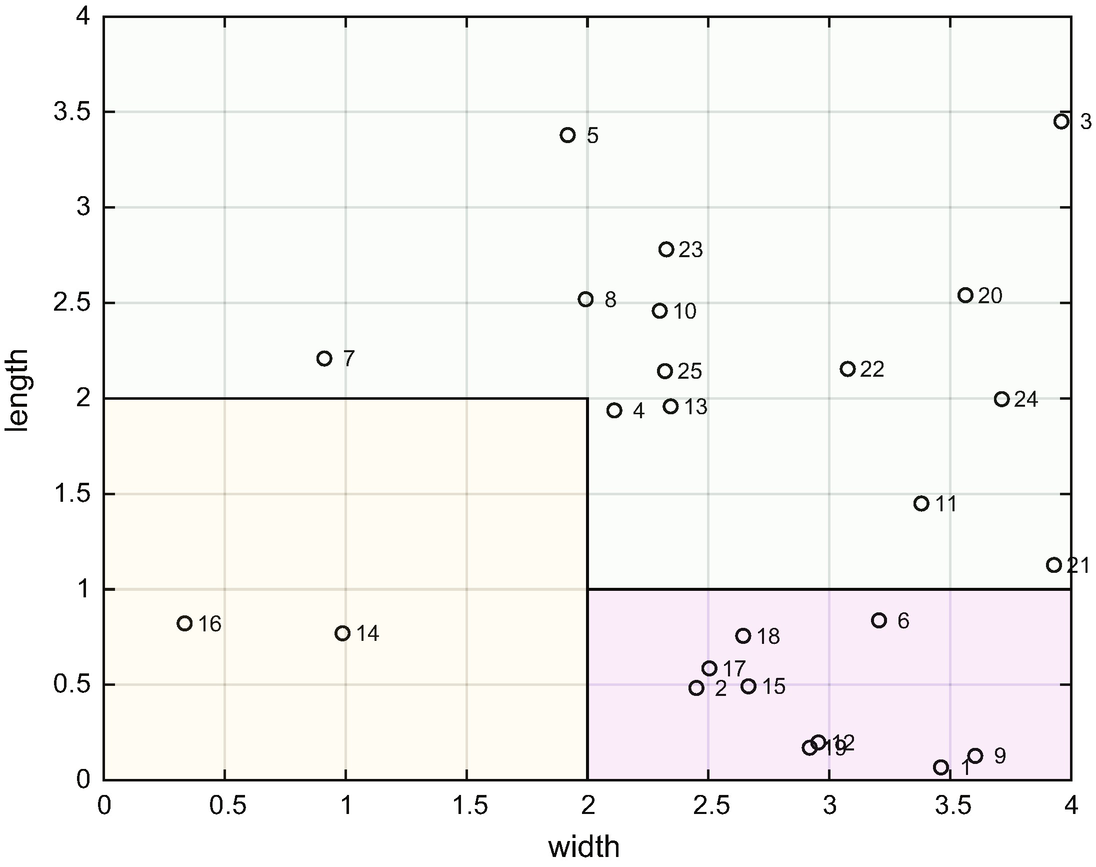

In this demo, there are three polygons. All points are defined in a square ranging from 0 to 4 in both the x and y directions.

The other subfunctions are PointInPolygon and Membership. Membership determines if a point is in a polygon. Membership calls PointInPolygon to assign points to sets. ClassifierSets randomly puts points in the regions. It figures out which region each point is in using this code in the function, PointInPolygon.

This code can determine if a point is inside a polygon defined by a set of vertices. It is used frequently in computer graphics and in games when you need to know if one object’s vertex is in another polygon. You could correctly argue that this function could replace our decision tree logic for this type of problem. However, a decision tree can compute membership for more complex sets of data. Our classifier set is simple and makes it easy to validate the results.

Run ClassifierSets to see the demo. Given the input ranges, it determines the membership of randomly selected points. p is a data structure that holds the vertices and the membership. It plots the points after creating a new figure using NewFigure. It then uses patch to create the rectangular regions.

The function shows the data numbers if there are fewer than 50 points. The MATLAB-function patch is used to generate the polygons. The code shows a range of graphics coding including the use of graphics parameters. Notice the way we create m colors.

TIP

You can create an unlimited number of colors for plots using linspace and cos.

Classifier set with three regions from the demo. Two are rectangles and one is L-shaped.

ClassifierTestSet can generate test sets or demonstrate a trained decision tree. The drawing shows that the classification regions are regions with sides parallel to the x- or y-axes. The regions should not overlap.

7.2 Drawing Decision Trees

7.2.1 Problem

We want to draw a binary decision tree to show decision tree thinking.

7.2.2 Solution

The solution is to use MATLAB graphics functions, patch, text, and line to draw a tree.

7.2.3 How It Works

The function DrawBinaryTree draws any binary tree. The function call is

The function starts by checking the number of inputs and either runs the demo or returns the default data structure. When you write a function you should always have defaults for anything where one is possible.

TIP

Whenever possible, have default inputs for function arguments.

It immediately creates a new figure with that name. It then steps through the boxes assigning them to rows based on it being a binary tree. The first row has one box, the next two boxes, the following four boxes, etc. As this is a geometric series, it will soon get unmanageable! This points to a problem with decision trees. If they have a depth of more than four, even drawing them is impossible. As it draws the boxes, it computes the bottom and top points, which will be the anchors for the lines between the boxes. After drawing all the boxes, it draws all the lines.

All of the drawing functionality is in the subfunction DrawBox.

This draws a box using the patch function and the text using the text function. ’facecolor’ is white. Red green blue (RGB) numbers go from 0 to 1. Setting ’facecolor’ to [1 1 1] makes the face white and leaves the edges black. As with all MATLAB graphics, there are dozens of properties that you can edit to produce beautiful graphics. Notice the extra arguments in text. The most interesting is ’HorizontalAlignment’ in the last line. It allows you to center the text in the box. MATLAB does all the figuring of font sizes for you.

The following listing shows the code in DrawBinaryTree, for drawing the tree, starting after checking for demos. The function returns the default data structure if one output and no inputs are specified. The first part of the code creates a new figure and draws the boxes at each node. It also creates arrays for the box locations for use in drawing the lines that connect the boxes. It starts off with the default argument for name. The first set of loops draws the boxes for the trees. rowID is a cell array. Each row in the cell is an array. A cell array allows each cell to be different. This makes it easy to have different length arrays in the cell. If you used a standard matrix, you would need to resize rows as new rows were added.

The remaining code draws the lines between the boxes.

The following built-in demo draws a binary tree. The demo creates three rows. It starts with the default data structure. You only have to add strings for the decision points. The boxes are in a flat list.

Notice that it calls the subfunction DefaultDataStructure to initialize the demo.

TIP

Always have the function return its default data structure. The default should have values that work.

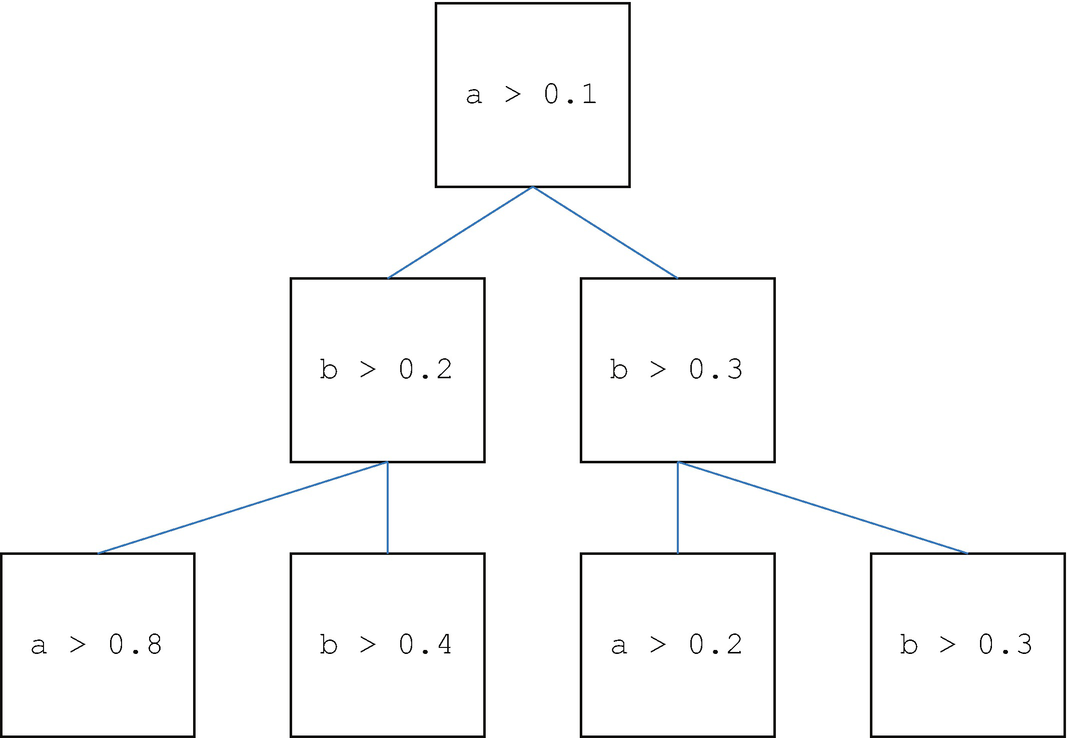

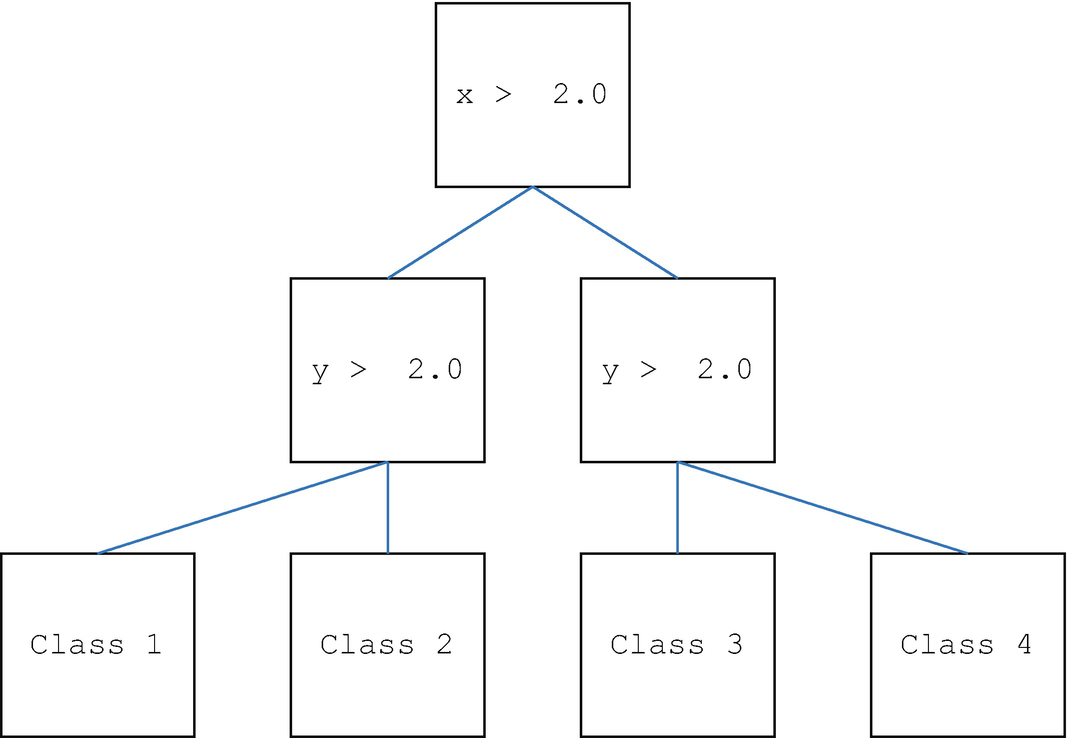

Binary tree from the demo in DrawBinaryTree.

The inputs for box could have been done in a loop. You could create them using sprintf. For example, for the first box you could write:

and put similar code in a loop.

7.3 Implementation

Decision trees are the main focus of this chapter. We’ll start with looking at how we determine if our decision tree is working correctly. We’ll then hand-build a decision tree and finally write learning code to generate the decisions for each block of the tree.

7.3.1 Problem

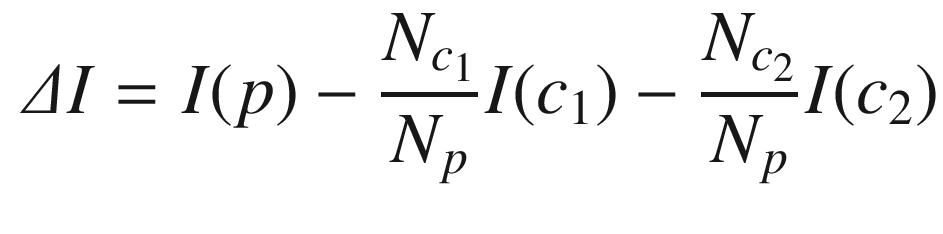

We need to measure the homogeneity of a set of data at different nodes on the decision tree. A data set is homogeneous if the points are similar to each other. For example, if you were trying to study grade points in a school with an economically diverse population, you would want to know if your sample was all children from wealthy families. Our goal in the decision tree is to end up with homogeneous sets.

7.3.2 Solution

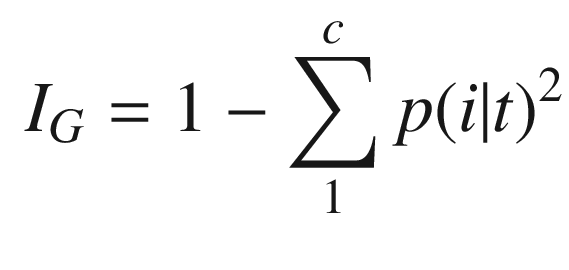

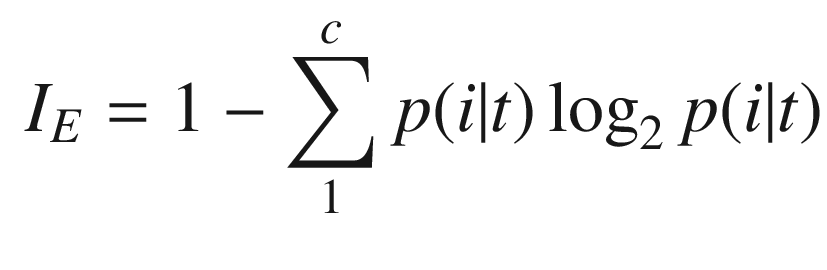

The solution is to implement the Gini impurity measure for a set of data. The function will return a single number as the homogeneity measure.

7.3.3 How It Works

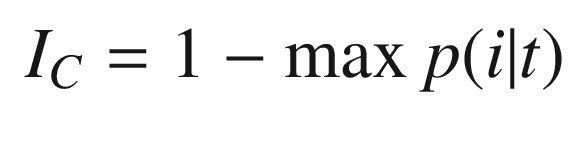

Gini impurity

Entropy

Classification error

Initialize initializes the data structure and computes the impurity measures for the data. There is one class for each different value of the data. For example, [1 2 3 3] would have three classes.

The demo is shown below. We try four different sets of data and get the measures. 0 is homogeneous. 1 means there is no data.

i is the homogeneity measure. d.dist is the fraction of the data points that have the value of that class. The class is the distinct values. The outputs of the demo are shown below.

The second to last set has a zero, which is the desired value. If there are no inputs it returns 1, since by definition for a class to exist it must have members.

7.4 Creating a Decision tree

7.4.1 Problem

We want to implement a decision tree for classifying data with two parameters.

7.4.2 Solution

The solution is to write a binary decision tree function in MATLAB called DecisionTree.

7.4.3 How It Works

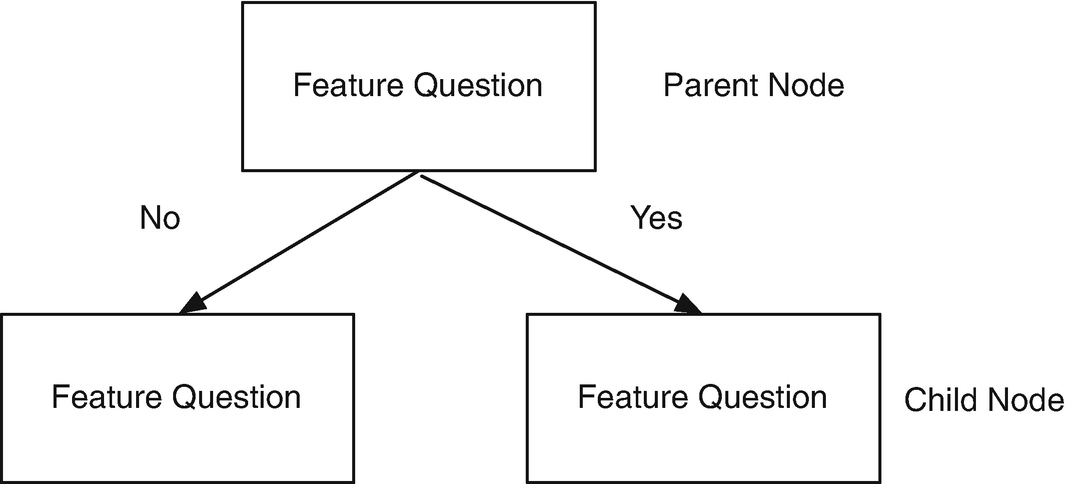

A decision tree [20] breaks down data by asking a series of questions about the data. Our decision trees will be binary in that there will be a yes or no answer to each question. For each feature in the data, we ask one question per decision node. This always splits the data into two child nodes. We will be looking at two parameters that determine class membership. The parameters will be numerical measurements.

- Which parameter (x or y) to check.

Figure 7.4

Figure 7.4Parent/child nodes.

What value of the parameter to use in the decision.

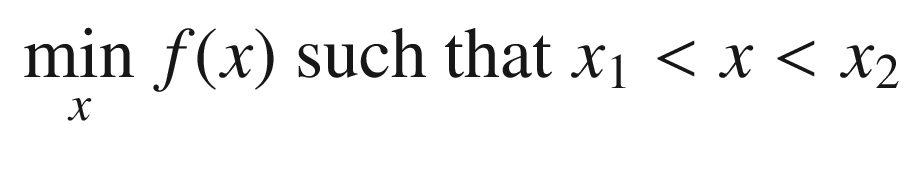

There are two actions, “train” and “test.” “train” creates the decision tree and “test” runs the generated decision tree. You can also input your own decision tree. FindOptimalAction finds the parameter that minimizes the inhomogeneity on both sides of the division. The function called by fminbnd is RHSGT. We only implement the greater than action. The function call is:

action is a string that is either “train” or “test.” d is the data structure that defines the tree. t are the inputs for either training or testing. The outputs are the updated data structure and r with the results.

The function is first called with training data and the action is “train.” The main function is short.

We added the error case otherwise for completeness. Note that we use lower to eliminate case sensitivity. Training creates the decision tree. A decision tree is a set of boxes connected by lines. A parent box has two child boxes if it is a decision box. A class box has no children. The subfunction Training trains the tree. It adds boxes at each node.

We use fminbnd to find the optimal switch point. We need to compute the homogeneity on both sides of the switch and sum the values. The sum is minimized by fminbnd in the subfunction FindOptimalAction. This code is designed for rectangular region classes. Other boundaries won’t necessarily work correctly. The code is fairly involved. It needs to keep track of the box numbering to make the parent child connections. When the homogeneity measure is low enough, it marks the boxes as containing the classes.

Box Data Structure Fields

Field | Decision Box | Class Box |

|---|---|---|

action | String | Not used |

value | Value to be used in the decision | Not used |

param | x or y | Not used |

child | Array with two children | Empty |

id | Empty | ID of data in the class |

class | Class ID | Not used |

7.5 Creating a Handmade Tree

7.5.1 Problem

We want to test a handmade decision tree.

7.5.2 Solution

The solution is to write a script to test a handmade decision tree.

7.5.3 How It Works

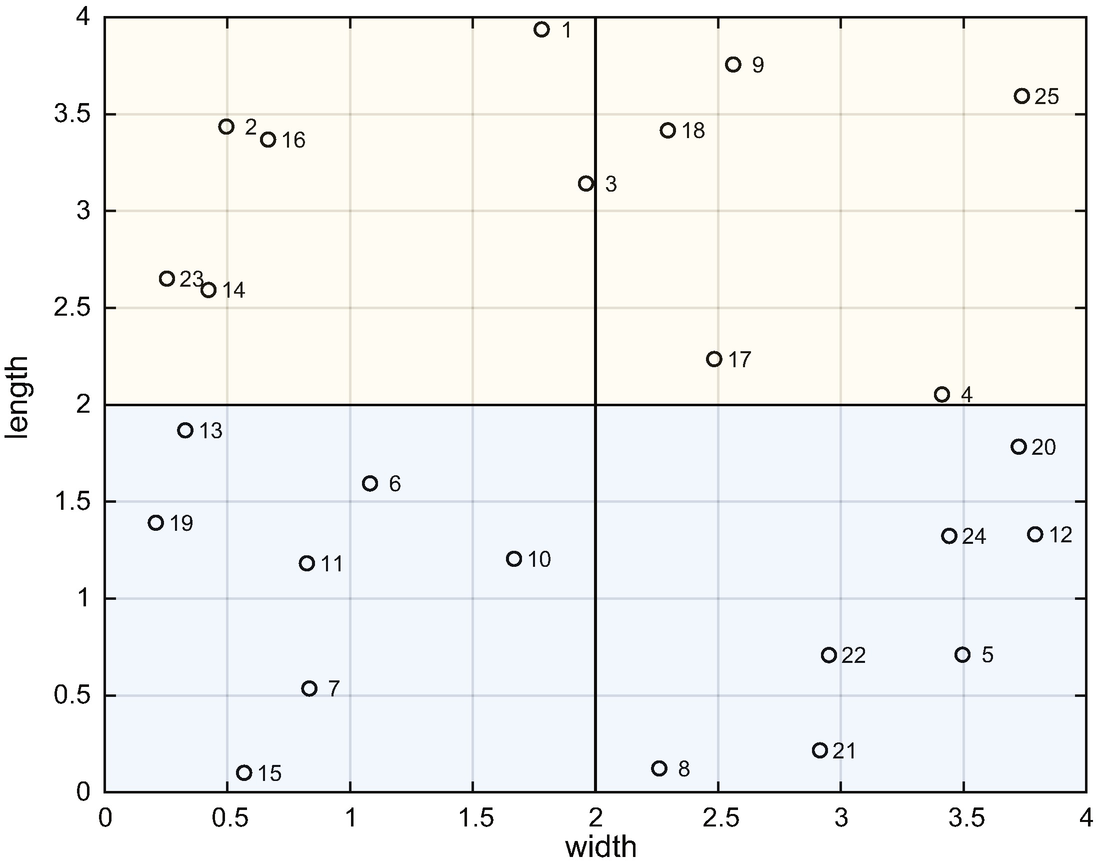

We write the test script SimpleClassifierDemo shown below. It uses the ’test’ action for DecisionTree. It generates 52 points. We create rectangular regions so that the face arrays have four elements for each polygon. DrawBinaryTree draws the tree.

SimpleClassifierDemo uses the hand-built example in DecisionTree.

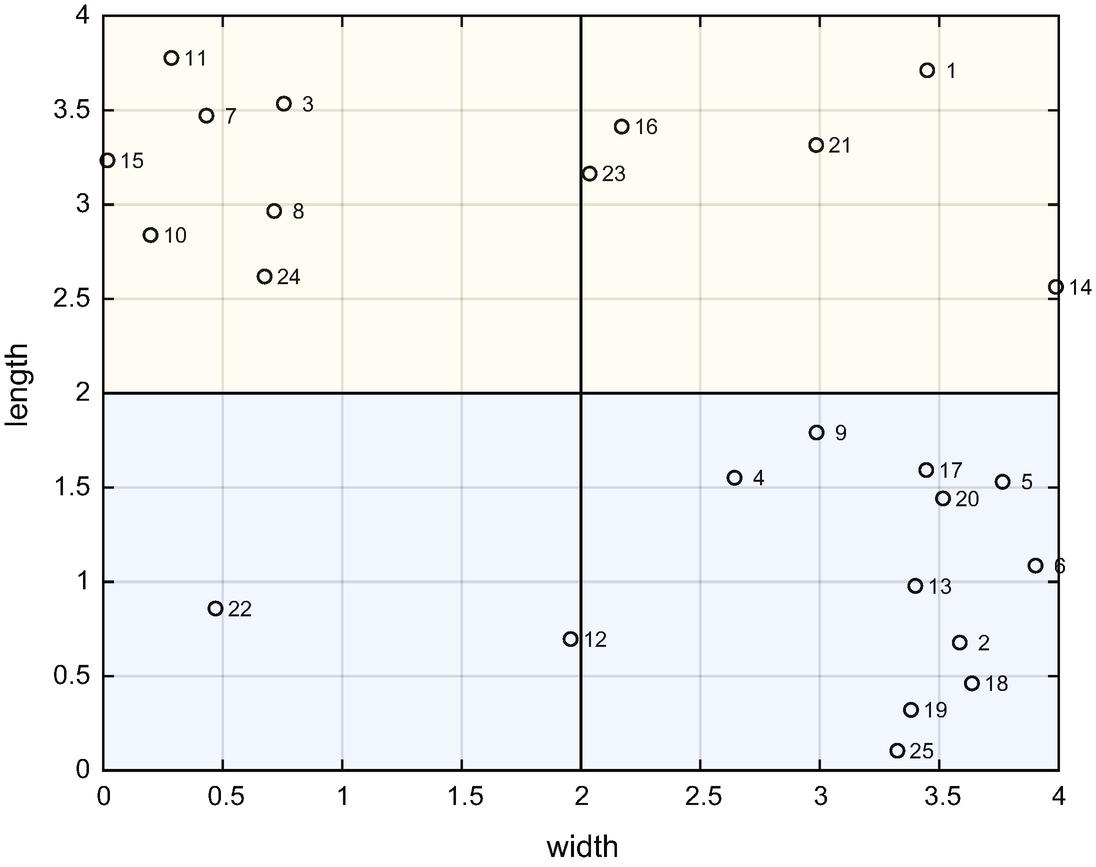

Data and classes in the test set.

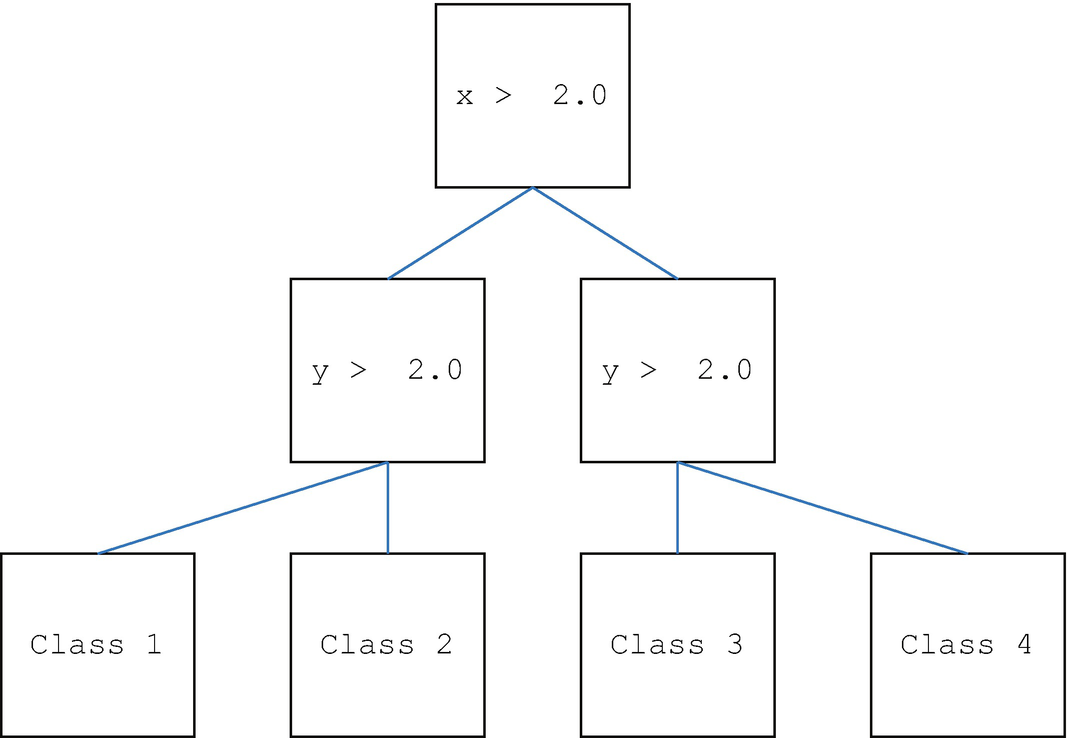

A manually created decision tree. The drawing is generated by DecisionTree. The last row of boxes is the data sorted into the four classes. The last nodes are the classes. Each box is a decision tree node.

The decision tree sorts the samples into the four sets. In this case, we know the boundaries and can use them to write the inequalities. In software, we will have to determine what values provide the shortest branches. The following is the output of SimpleClassifierDemo. The decision tree properly classifies all of the data.

7.6 Training and Testing

7.6.1 Problem

We want to train our decision tree and test the results.

7.6.2 Solution

We replicated the previous recipe, only this time we have DecisionTree create the decision tree instead of creating it by hand.

7.6.3 How It Works

TestDecisionTree trains and tests the decision tree. It is very similar to the code for the hand-built decision tree demo, SimpleClassifierDemo. Once again, we use rectangles for the regions.

It uses ClassifierSets to generate the training data. The output includes the coordinates and the sets in which they fall. We then create the default data structure and call DecisionTree in training mode.

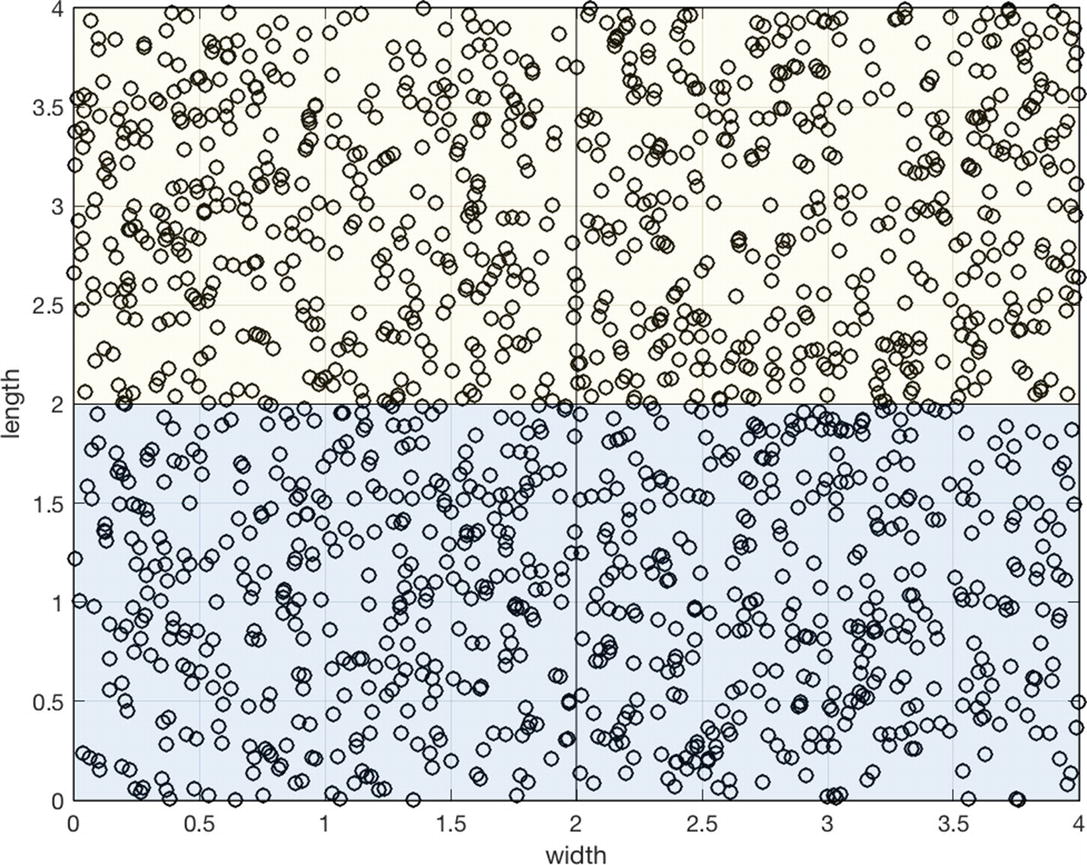

The training data. A large amount of data is needed to fill the classes.

The testing data.

The tree derived from the training data. It is essentially the same as the hand-derived tree. The values in the generated tree are not exactly 2.0.

The results are similar to the simple test.

The generated tree separates the data effectively.

7.7 Summary

Chapter Code Listing

File | Description |

|---|---|

ClassifierSets | Generate data for classification or training. |

DecisionTree | Implements a decision tree to classify data. |

DrawBinaryTree | Generates data for classification or training. |

HomogeneityMeasure | Computes Gini impurity. |

SimpleClassifierDemo | Demonstrates decision tree testing. |

SimpleClassifierExample | Generates data for a simple problem. |

TestDecisionTree | Tests a decision tree. |