Number of hidden layers

Number of hidden units

Activation function

Learning rate

Working details of neural networks

The impact of various hyper-parameters on neural networks

Feed-forward and back propagation

The impact of learning rate on weight updates

Ways to avoid Over-fitting in neural networks

How to implement neural network in Excel, Python, and R

Neural networks came about from the fact that not everything can be approximated by a linear/logistic regression—there may be potentially complex shapes within data that can only be approximated by complex functions. The more complex the function (with some way to take care of overfitting), the better is the accuracy of predictions. We’ll start by looking at how neural networks work toward fitting data into a model.

Structure of a Neural Network

Transforming the output

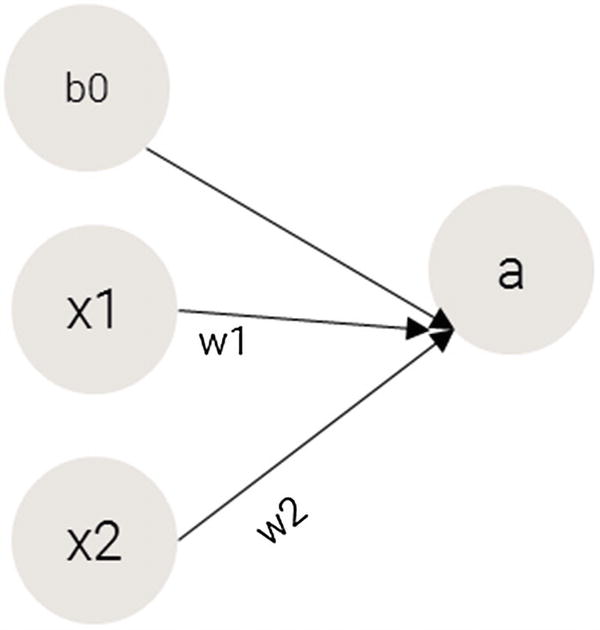

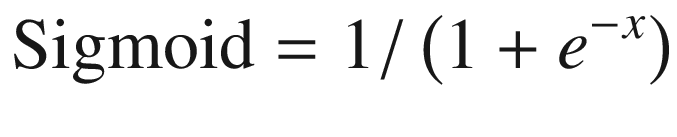

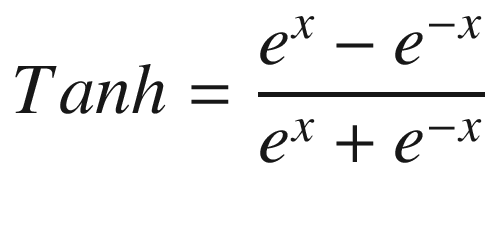

The function in the preceding equation is the activation function we are applying on top of the summation so that we attain non-linearity (we need non-linearity so that our model can now learn complex patterns). The different activation functions are discussed in more detail in a later section.

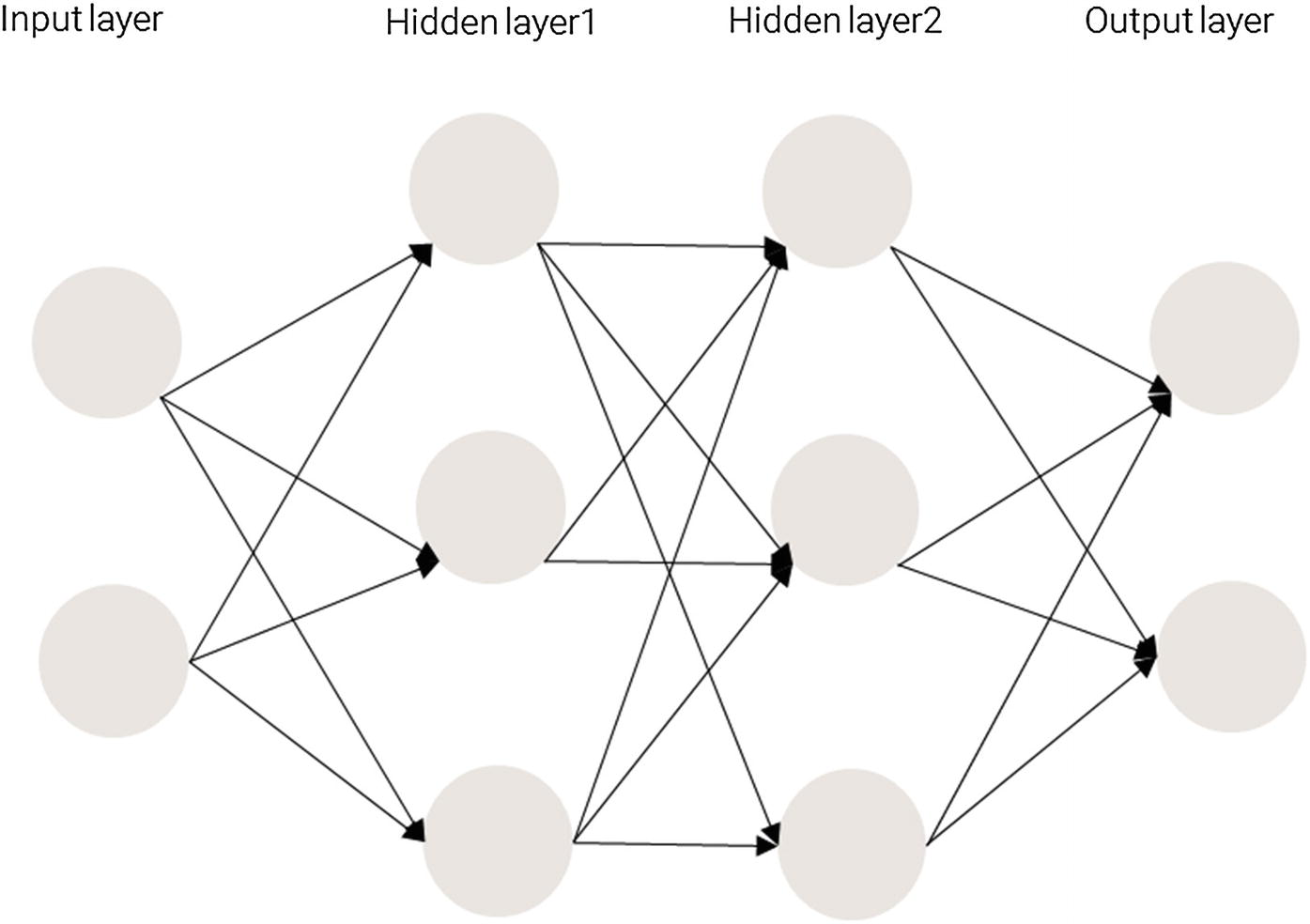

Moreover, having more than one hidden layer helps in achieving high non-linearity. We want to achieve high non-linearity because without it, a neural network would be a giant linear function.

Hidden layers are necessary when the neural network has to make sense of something very complicated, contextual, or non-obvious, like image recognition. The term deep learning comes from having many hidden layers. These layers are known as hidden because they are not visible as a network output.

Working Details of Training a Neural Network

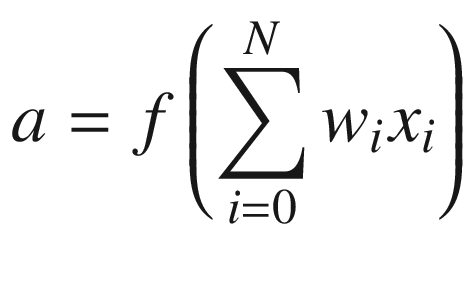

Training a neural network basically means calibrating all the weights by repeating two key steps: forward propagation and back propagation.

In forward propagation , we apply a set of weights to the input data and calculate an output. For the first forward propagation, the set of weights’ values are initialized randomly.

In back propagation , we measure the margin of error of the output and adjust the weights accordingly to decrease the error.

Neural networks repeat both forward and back propagation until the weights are calibrated to accurately predict an output.

Forward Propagation

Input | Output |

|---|---|

(0,0) | 0 |

(0,1) | 1 |

(1,0) | 1 |

(1,1) | 0 |

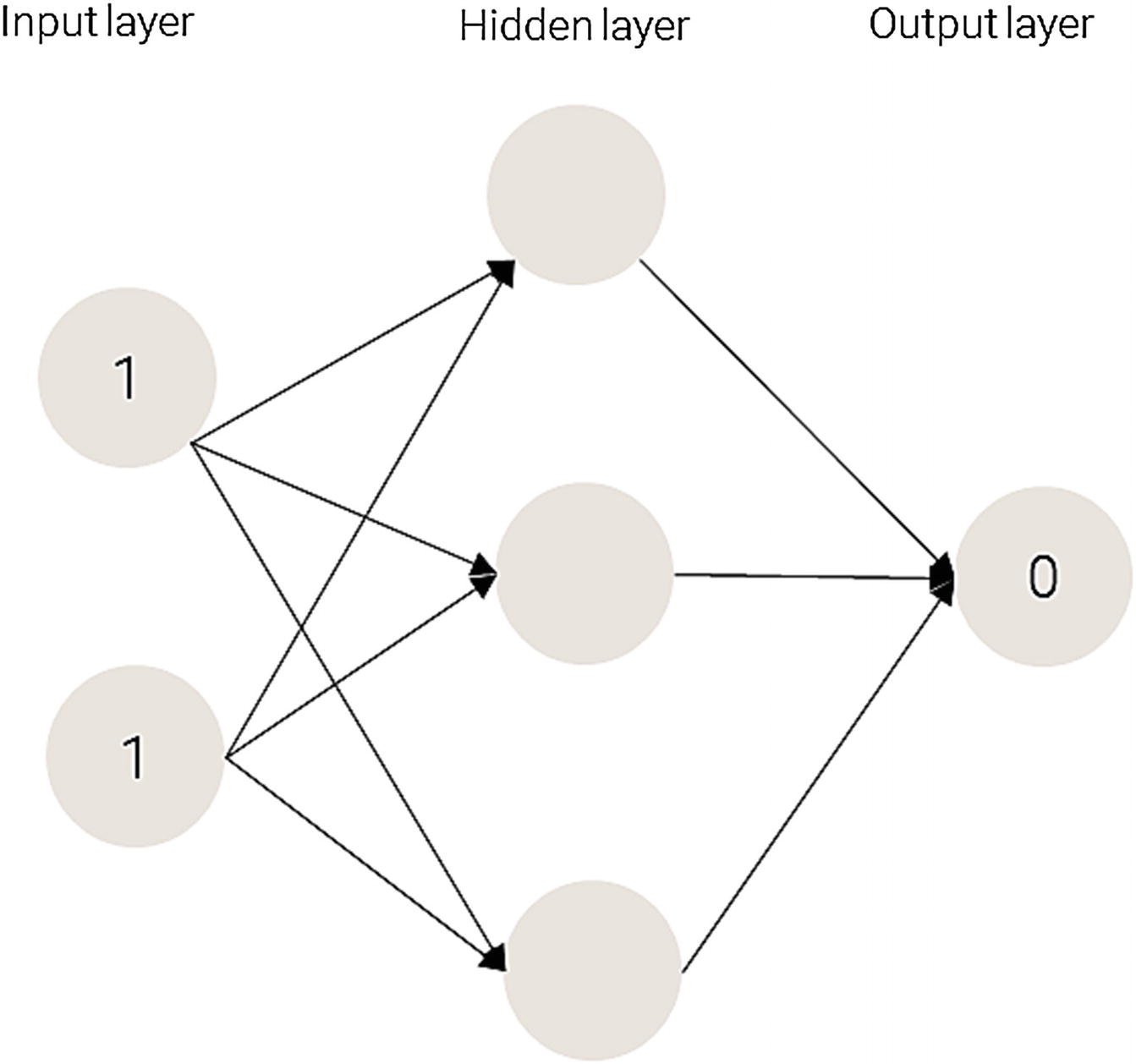

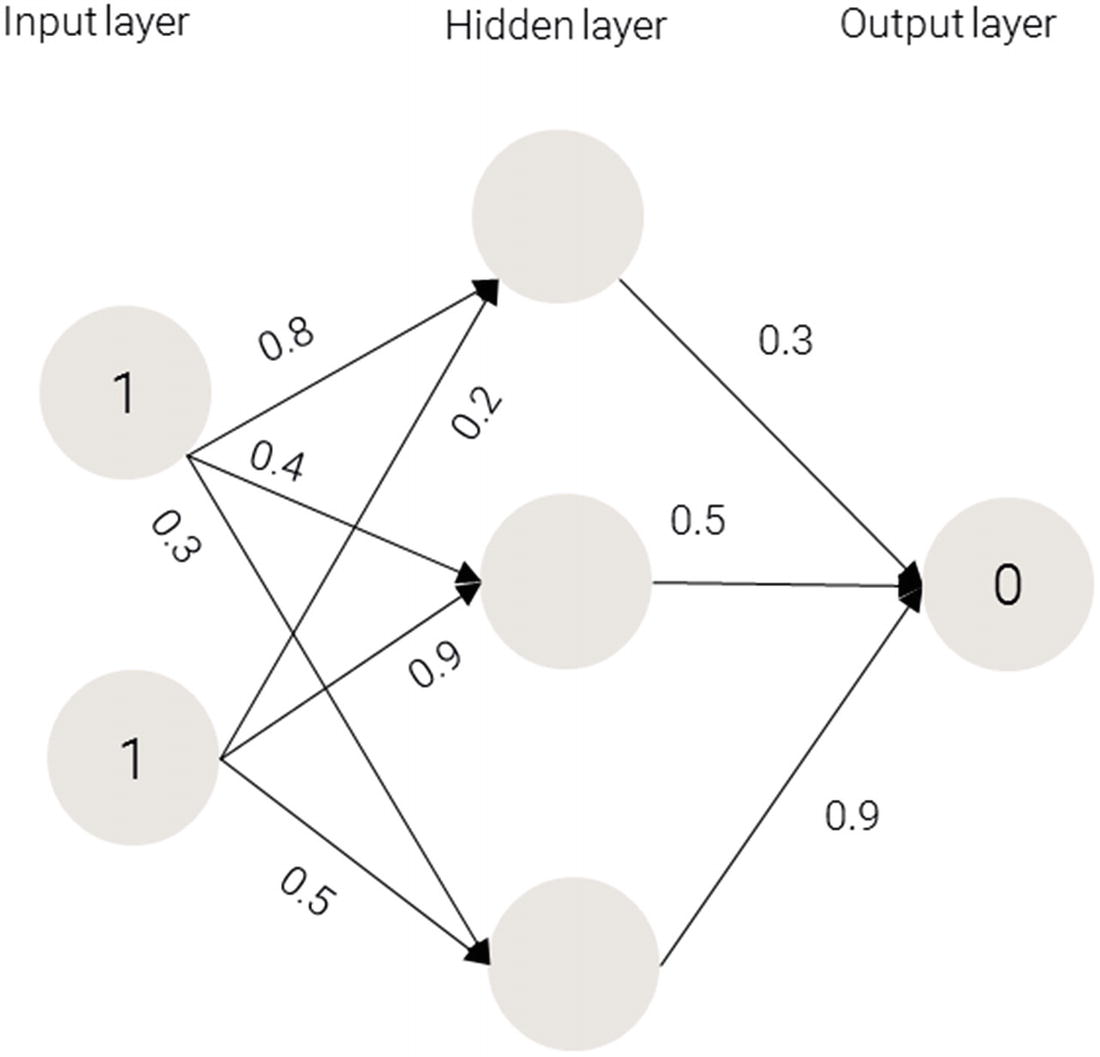

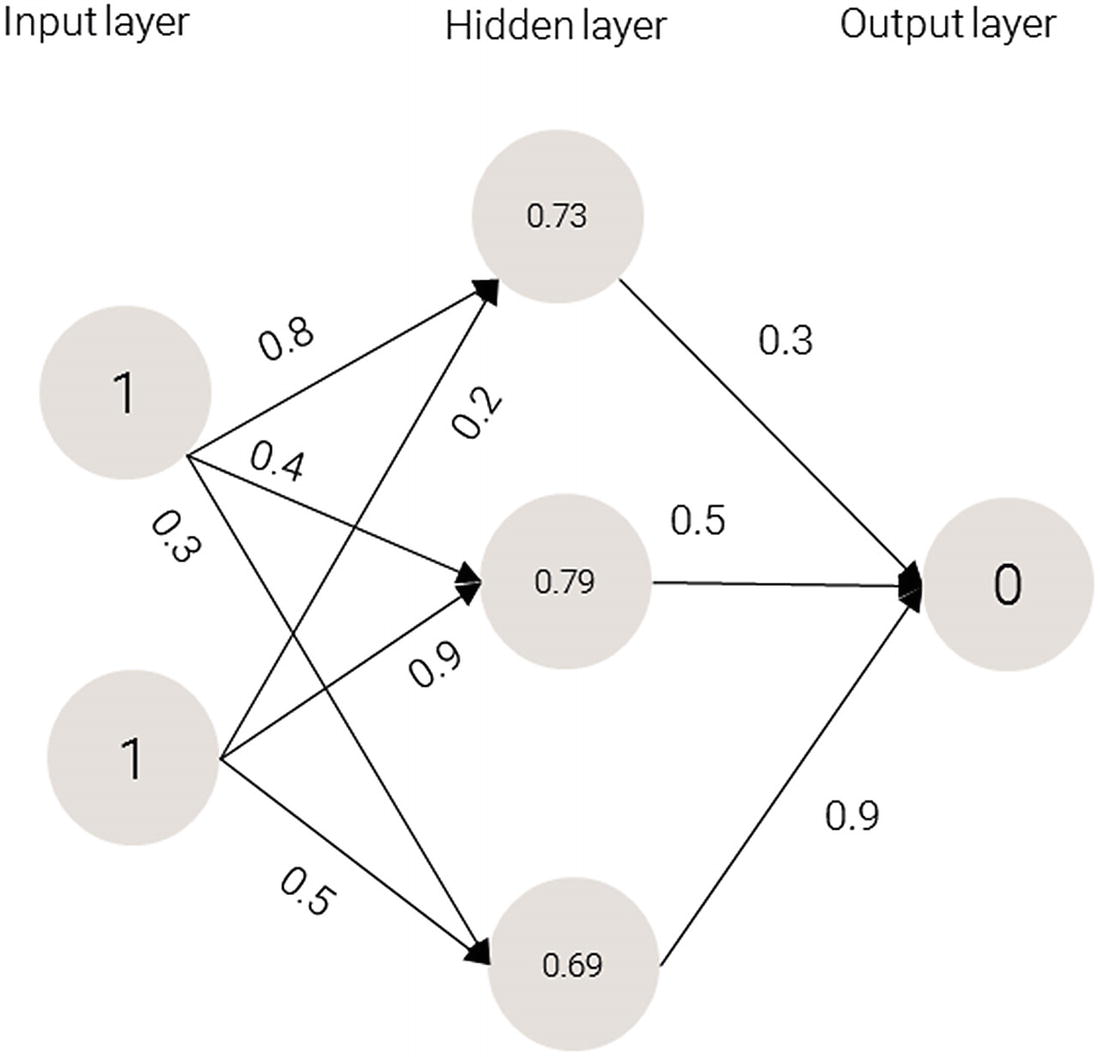

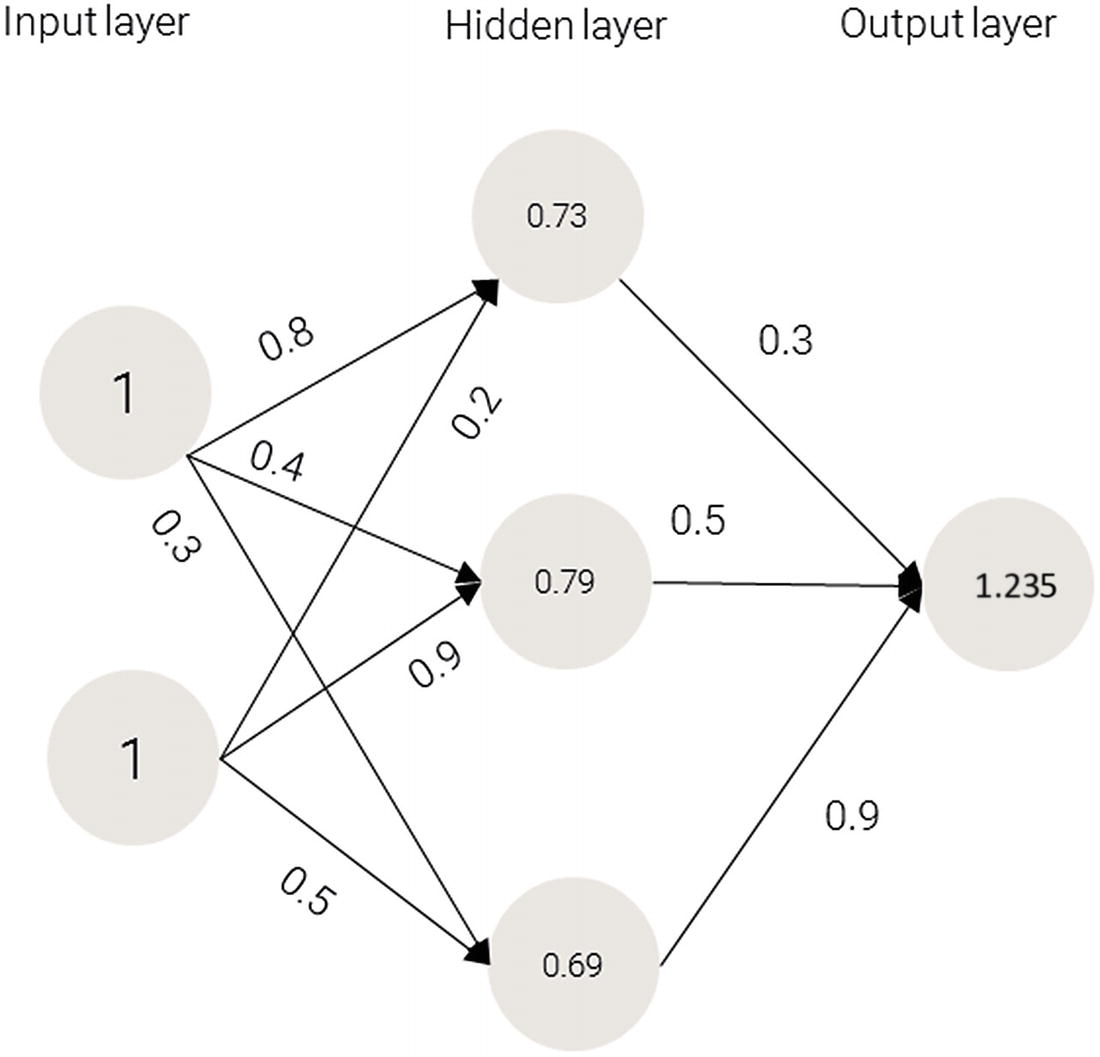

Applying a neural network

Weights on the synapses

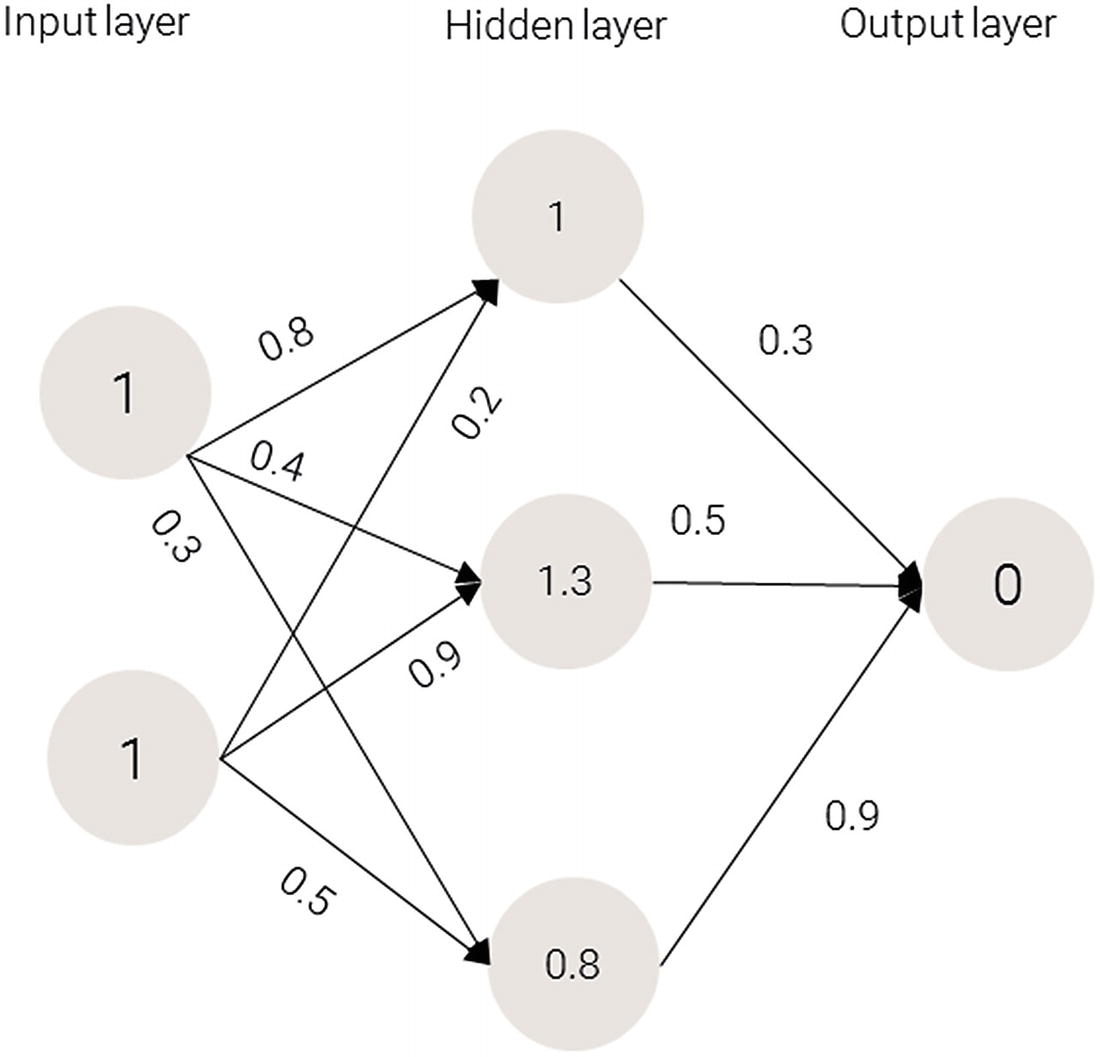

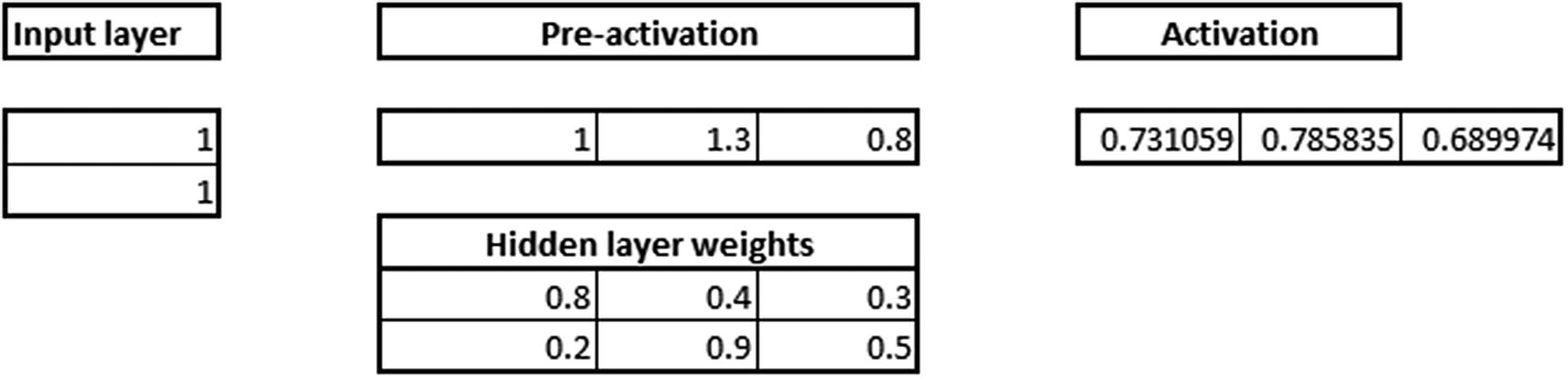

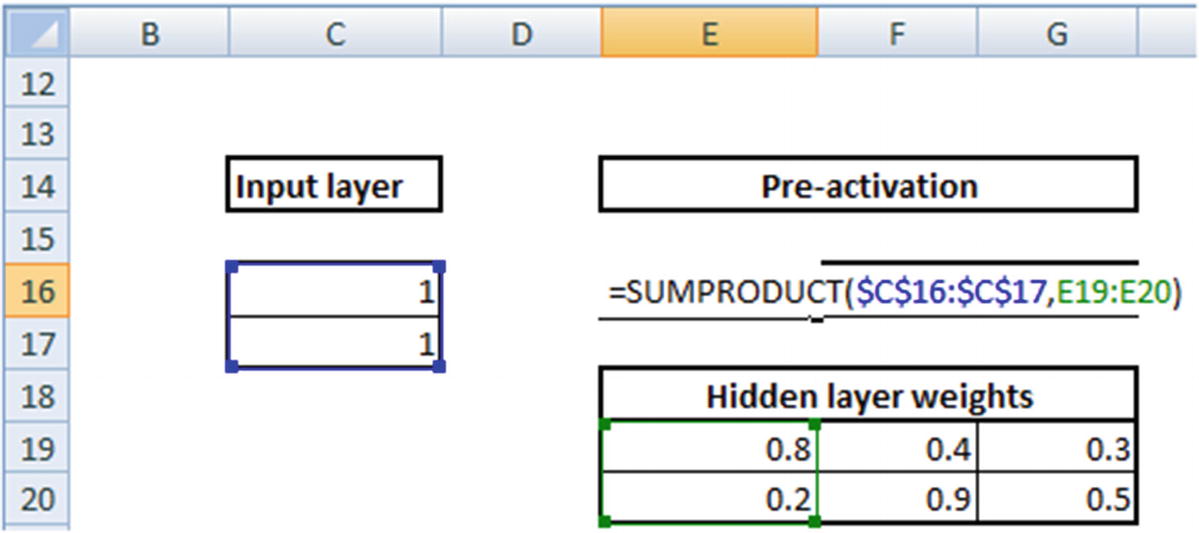

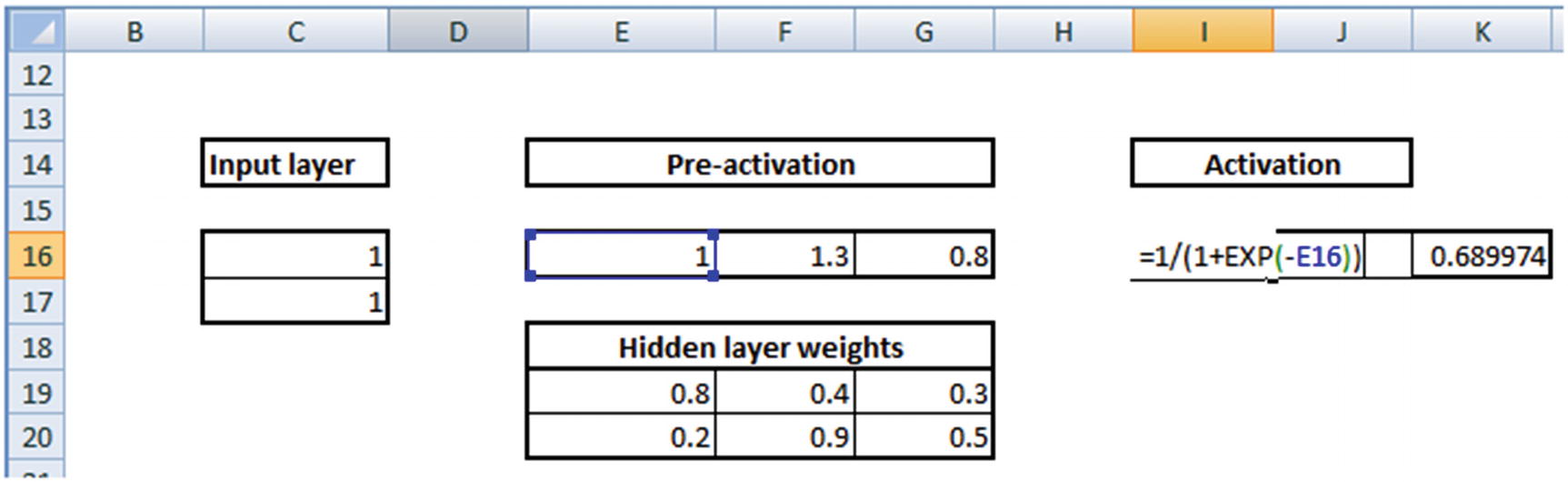

1 × 0.8 + 1 × 0.2 = 1

1 × 0.4 + 1 × 0.9 = 1.3

1 × 0.3 + 1 × 0.5 = 0.8

Values for the hidden layer

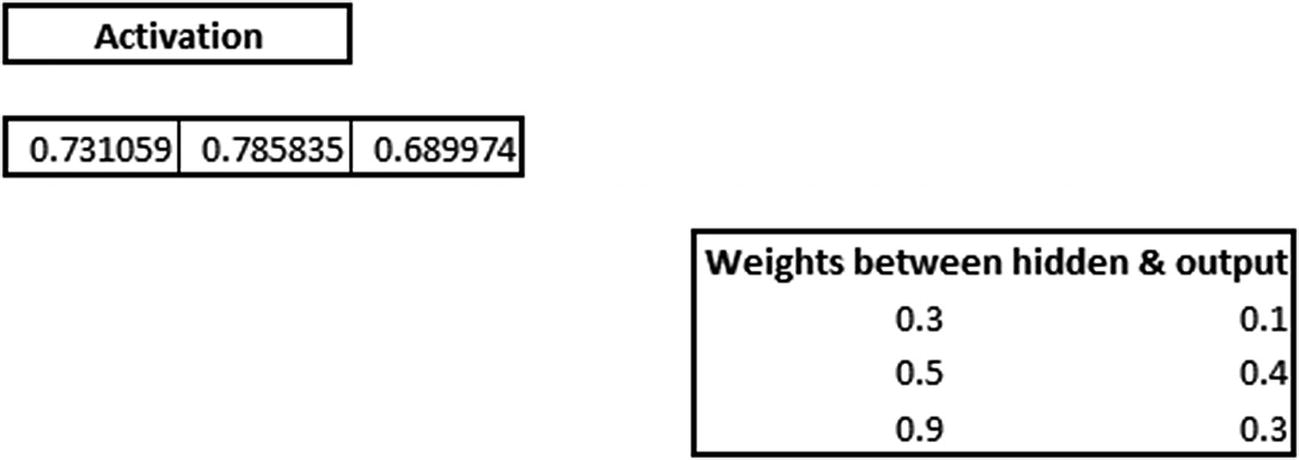

Applying the Activation Function

Activation functions are applied at the hidden layer of a neural network. The purpose of an activation function is to transform the input signal into an output signal. They are necessary for neural networks to model complex non-linear patterns that simpler models might miss.

Sigmoid(1.0) = 0.731

Sigmoid(1.3) = 0.785

Sigmoid(0.8) = 0.689

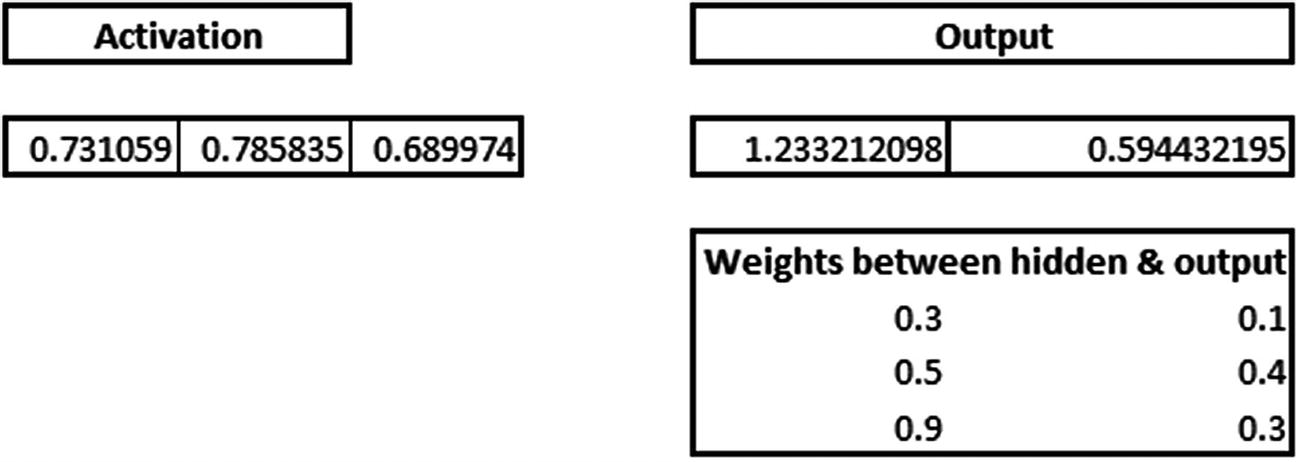

Applying sigmoid to the hidden layer sums

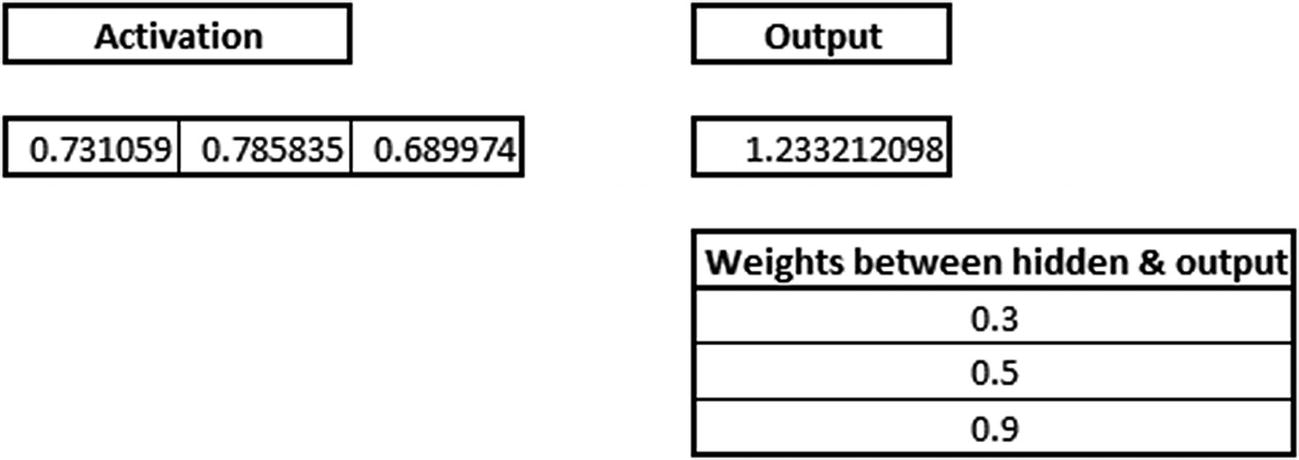

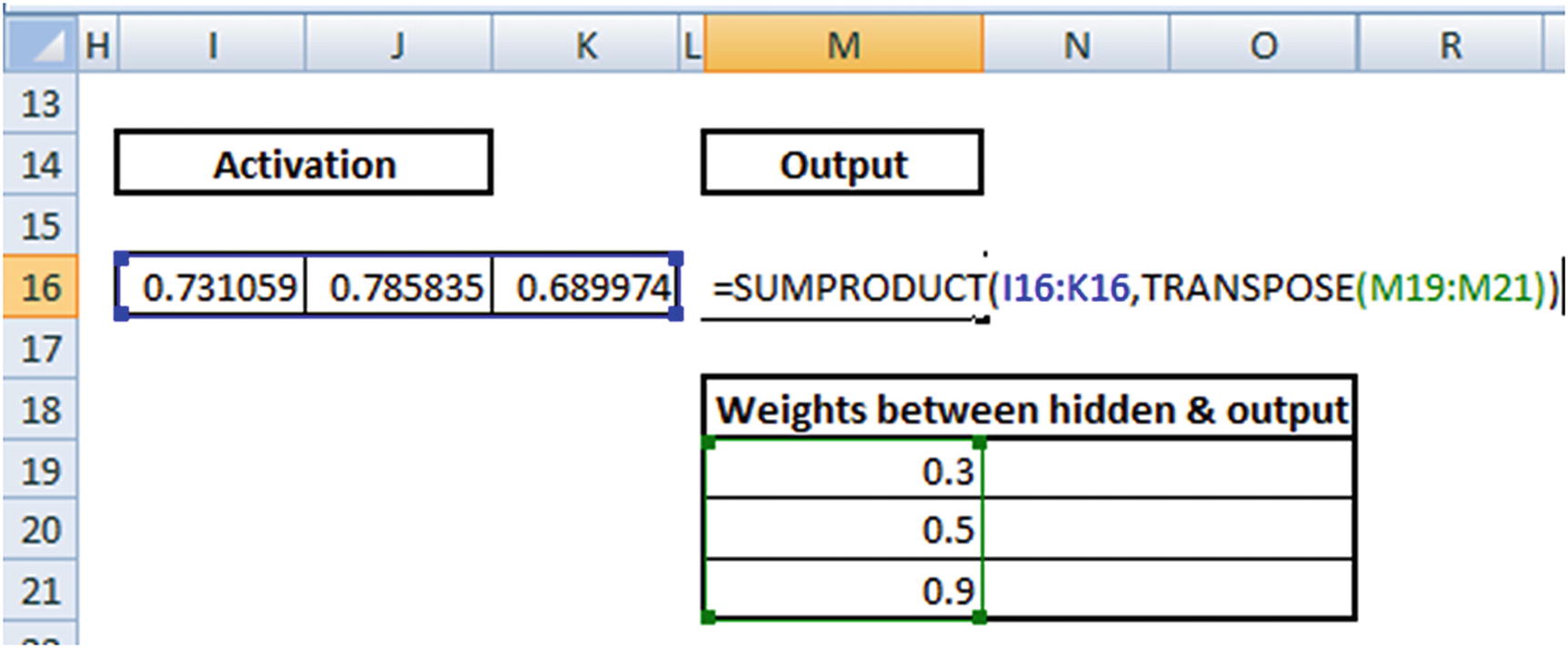

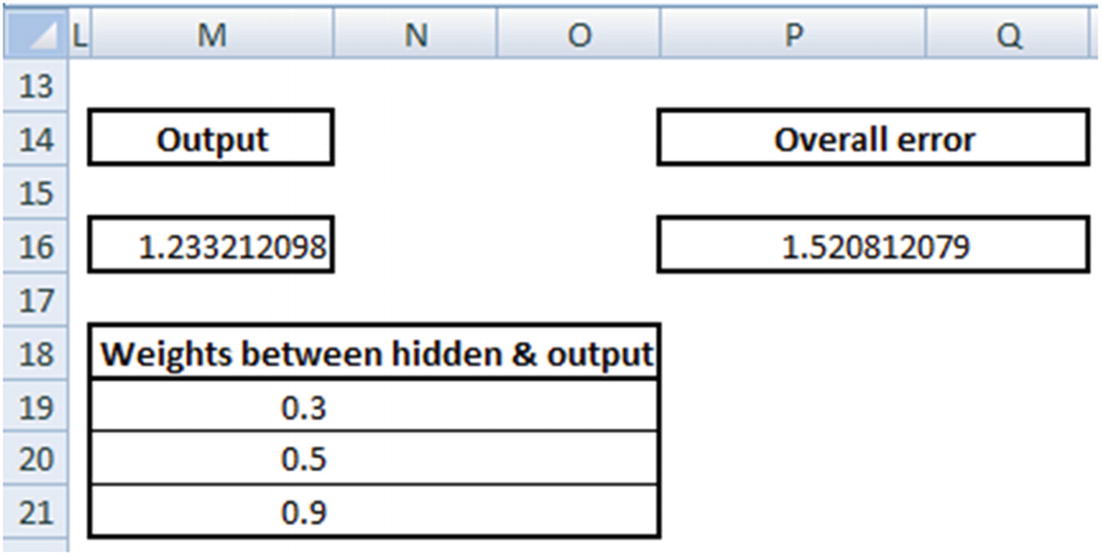

0.73 × 0.3 + 0.79 × 0.5 + 0.69 × 0.9 = 1.235

Applying the activation function

Because we used a random set of initial weights, the value of the output neuron is off the mark—in this case, by 1.235 (since the target is 0).

- 1.

The input layer has two inputs (1,1), thus input layer is of dimension of 1 × 2 (because every input has two different values).

- 2.

The 1 × 2 hidden layer is multiplied with a randomly initialized matrix of dimension 2 × 3.

- 3.

The output of input to hidden layer is a 1 × 3 matrix:

Again, while this is a classification exercise, where we use cross entropy error as loss function, we will still use squared error loss function only to make the back propagation calculations easier to understand. We will understand about how classification works in neural network in a later section.

The various steps involved in obtaining squared error from an input layer, collectively form a forward propagation.

Back Propagation

In forward propagation, we took a step from input to hidden to output. In backward propagation , we take the reverse approach: essentially, change each weight starting from the last layer by a small amount until the minimum possible error is reached. When a weight is changed, the overall error either decreases or increases. Depending on whether error increased or decreased, the direction in which a weight is updated is decided. Moreover, in some scenarios, for a small change in weight, error increases/decreases by quite a bit, and in some cases error changes only by a small amount.

- 1.

Decide the direction in which weight needs to be updated

- 2.

Decide the magnitude by which the weights need to be updated

Before proceeding with implementing back propagation in Excel, let’s look at one additional aspect of neural networks: the learning rate . Learning rate helps us in building trust in our decision of weight updates. For example, while deciding on the magnitude of weight update, we would potentially not change everything in one go but rather take a more careful approach in updating the weights more slowly. This results in obtaining stability in our model. A later section discusses how learning rate helps in stability.

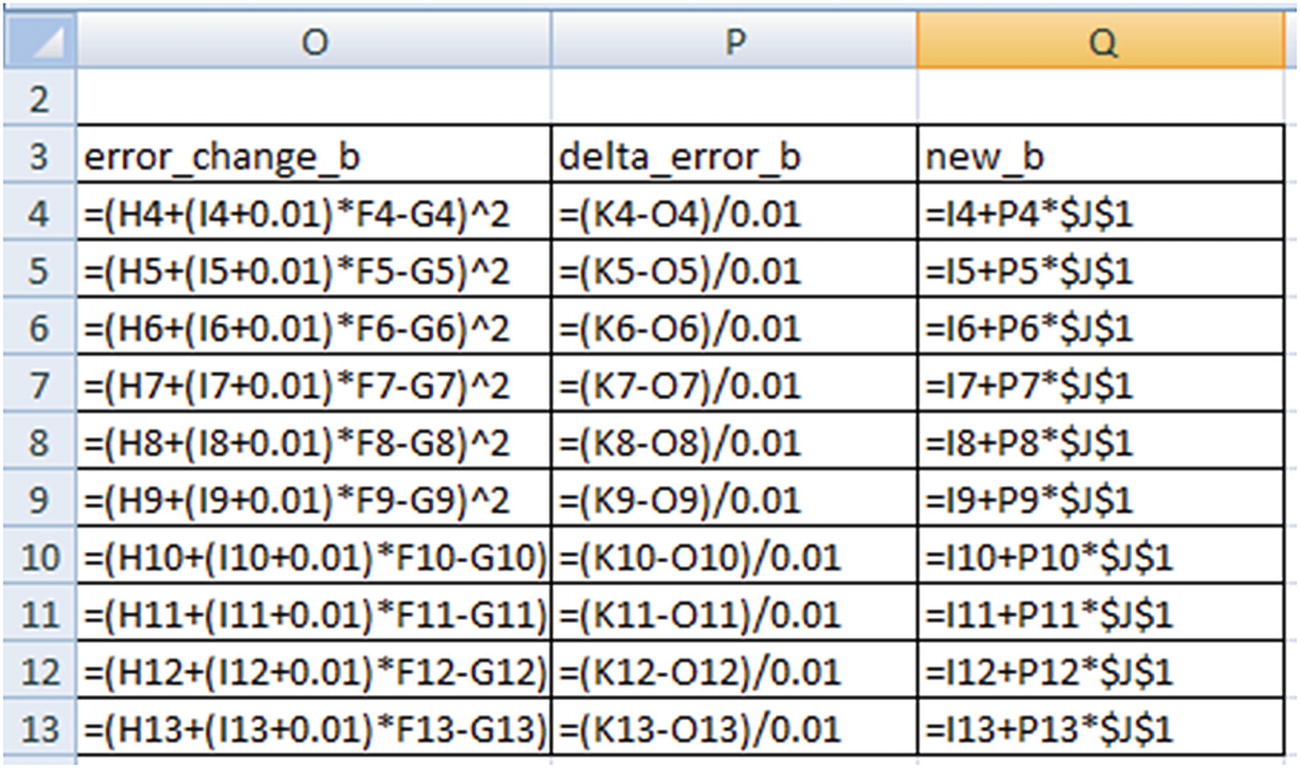

Working Out Back Propagation

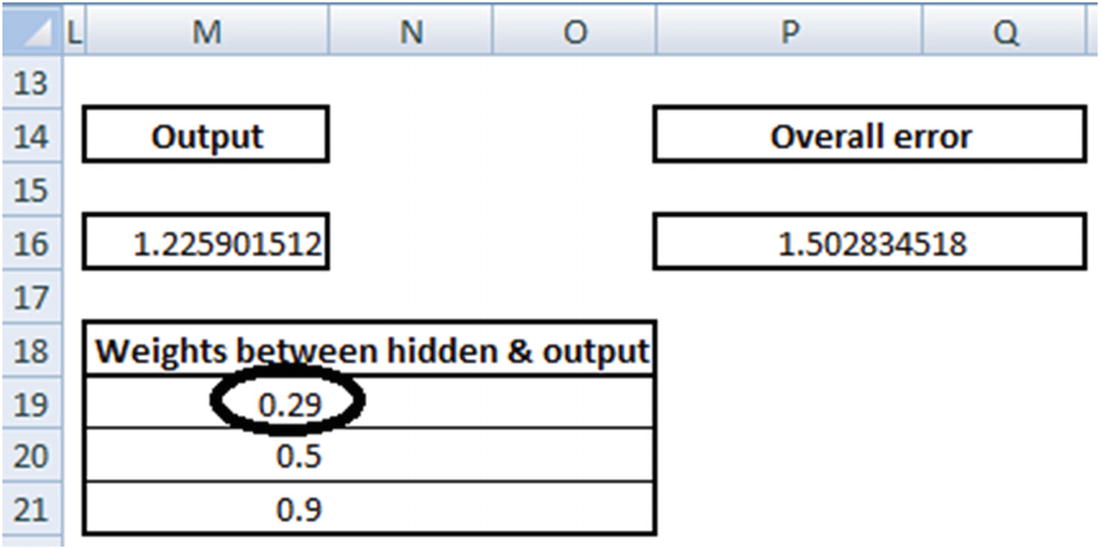

To see how back propagation works, let’s look at updating the randomly initialized weight values in the previous section.

Note that with a small decrease in weight, the overall error decreases from 1.52 to 1.50. Thus, from the two points mentioned earlier, we conclude that 0.3 needs to be reduced to a lower number. The question we need to answer after deciding the direction in which the weight needs to be updated is: “What is the magnitude of weight update?”

0.3 – 0.05 × (Reduction in error because of change in weight)

The 0.05 there is the learning parameter, which is to be given as input by user - more on learning rate in the next section. Thus the weight value gets updated to 0.3 – 0.05 × ((1.52 - 1.50) / 0.01) = 0.21.

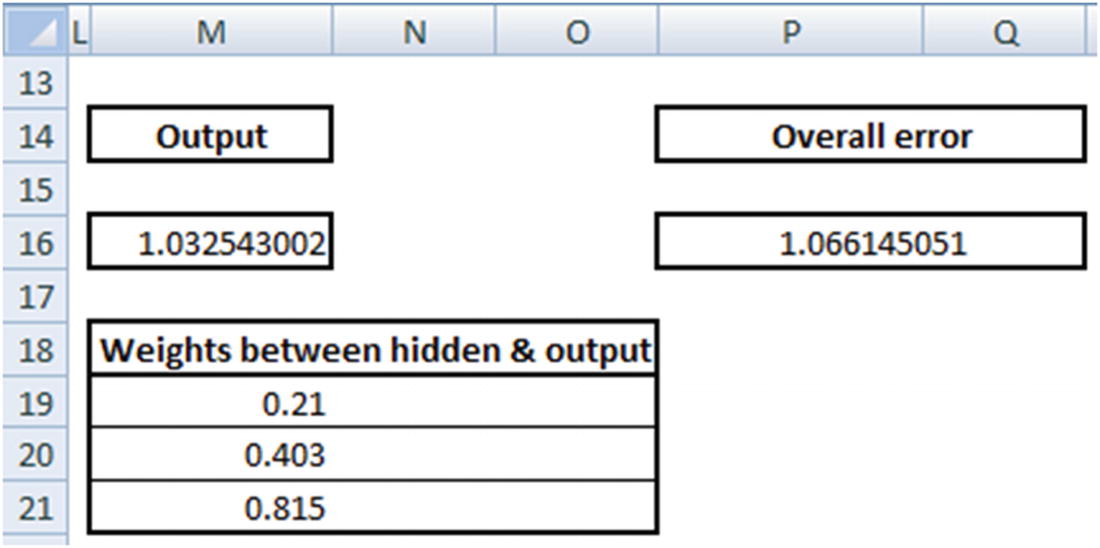

Note that the overall error decreased by quite a bit by just changing the weights connecting the hidden layer to the output layer.

Original weight | Updated weight | Decrease in error |

|---|---|---|

0.8 | 0.7957 | 0.0009 |

0.4 | 0.3930 | 0.0014 |

0.3 | 0.2820 | 0.0036 |

0.2 | 0.1957 | 0.0009 |

0.9 | 0.8930 | 0.0014 |

0.5 | 0.4820 | 0.0036 |

Given that error is decreasing every time when the weights are decreased by a small value, we will reduce all the weights to the value calculated above.

Now that the weights are updated, note that the overall error decreased from 1.52 to 1.05. We keep repeating the forward and backward propagation until the overall error is minimized as much as possible.

Stochastic Gradient Descent

Gradient descent is the way in which error is minimized in the scenario just discussed. Gradient stands for difference (the difference between actual and predicted) and descent means to reduce. Stochastic stands for the subset of training data considered to calculate error and thereby weight update (more on the subset of data in a later section).

Diving Deep into Gradient Descent

To further our understanding of gradient descent neural networks, let’s start with a known function and see how the weights could be derived: for now, we will have the known function as y = 6 + 5x.

x | y |

|---|---|

1 | 11 |

2 | 16 |

3 | 21 |

4 | 26 |

5 | 31 |

6 | 36 |

7 | 41 |

8 | 46 |

9 | 51 |

10 | 56 |

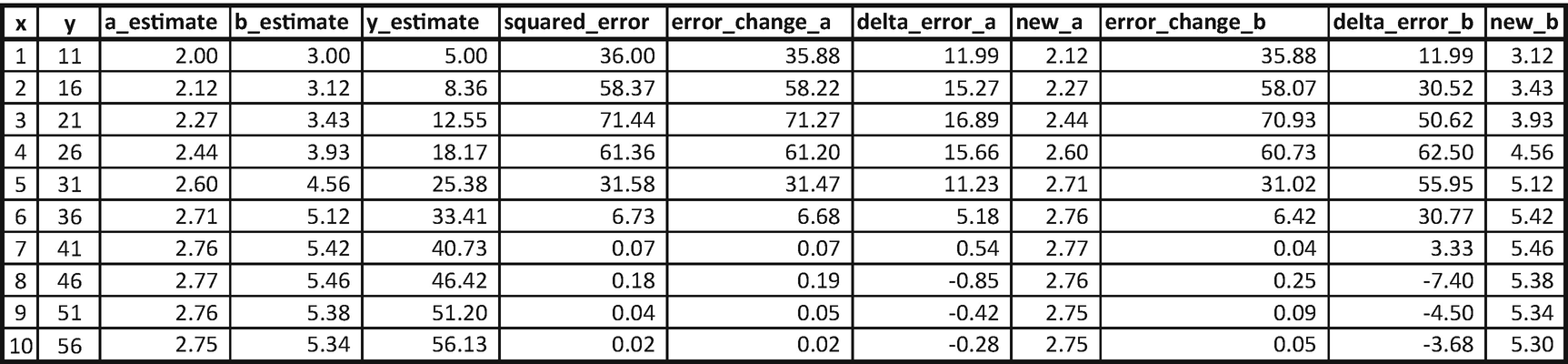

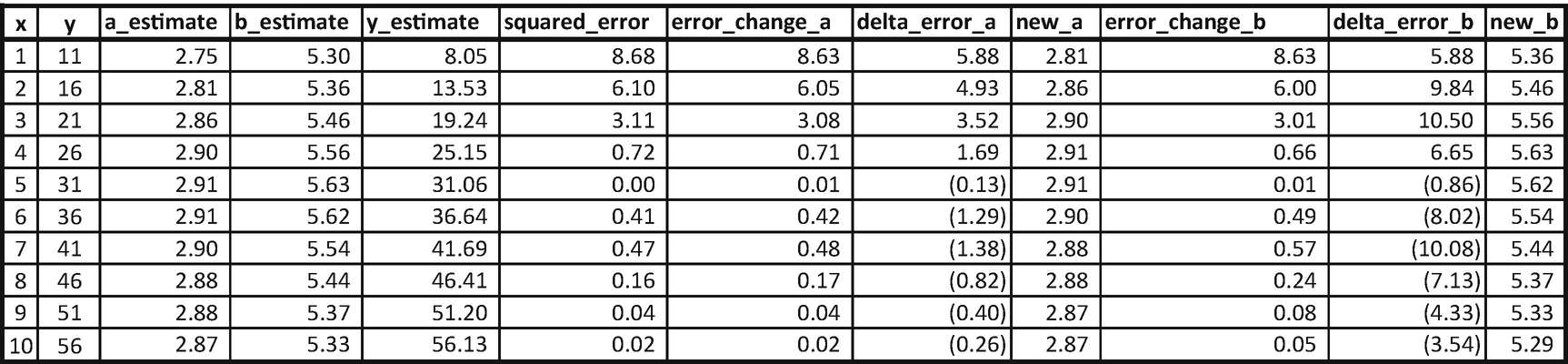

Note that we started with the random initialization of a_estimate and b_estimate estimate with 2 and 3 (row 1, columns 3 and 4).

Calculate the estimate of y using the randomly initialized values of a and b: 5.

Calculate the squared error corresponding to the values of a and b (36 in row 1).

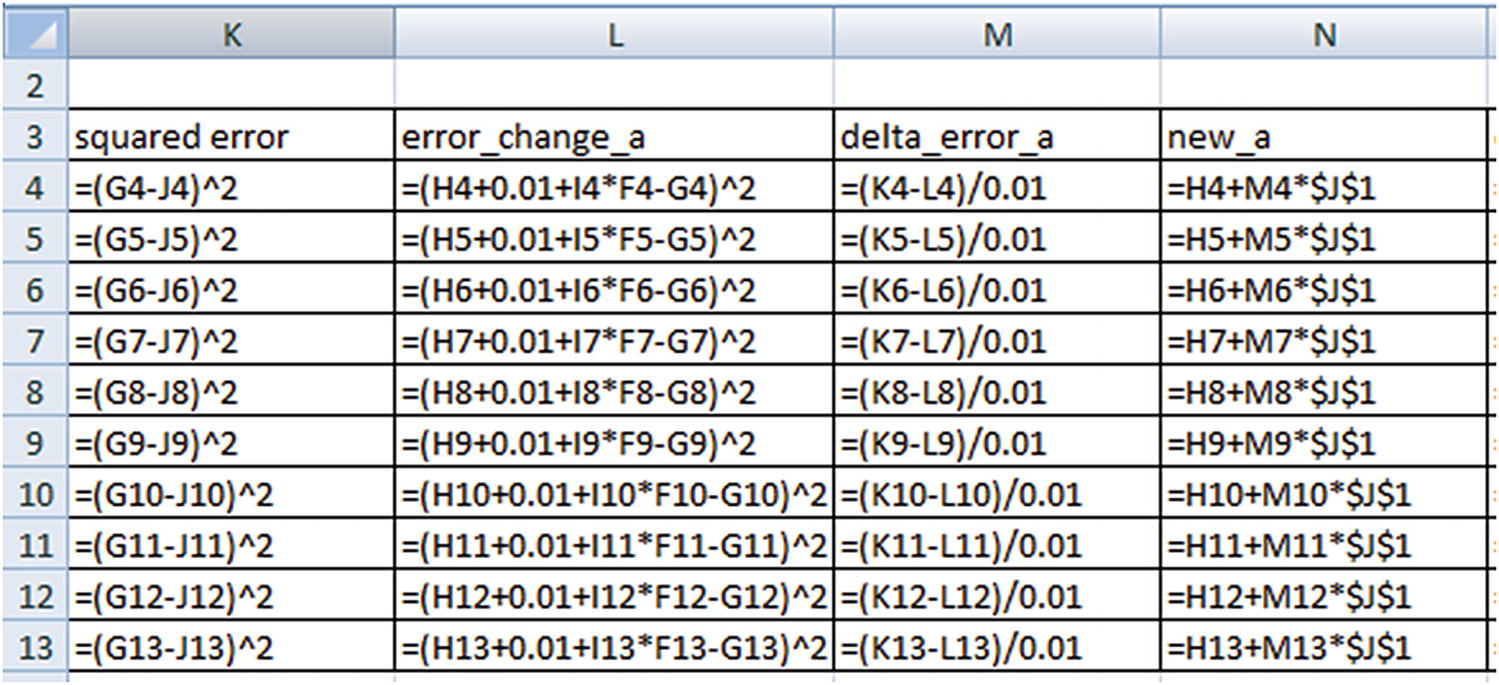

Change the value of a slightly (increase it by 0.01) and calculate the squared error corresponding to the changed a value. This is stored as the error_change_a column.

Calculate the change in error in delta_error_a (which is change in error / 0.01). Note that the delta would be very similar if we perform differentiation over loss function with respect to a.

Update the value of a based on: new_a = a_estimate + (delta_error_a) × learning_rate.

Once the values of a and b are updated (new_a and new_b are calculated in the first row), perform the same analysis on row 2 (Note that we start off row 2 with the updated values of a and b obtained from the previous row.) We keep on updating the values of a and b until all the data points are covered. At the end, the updated value of a and b are 2.75 and 5.3.

The values of a and b started at 2.75 and 5.3 and ended up at 2.87 and 5.29, which is a little more accurate than the previous iteration. With more iterations, the values of a and b would converge to the optimal value.

RMSprop

Adagrad

Adadelta

Adam

Adamax

Nadam

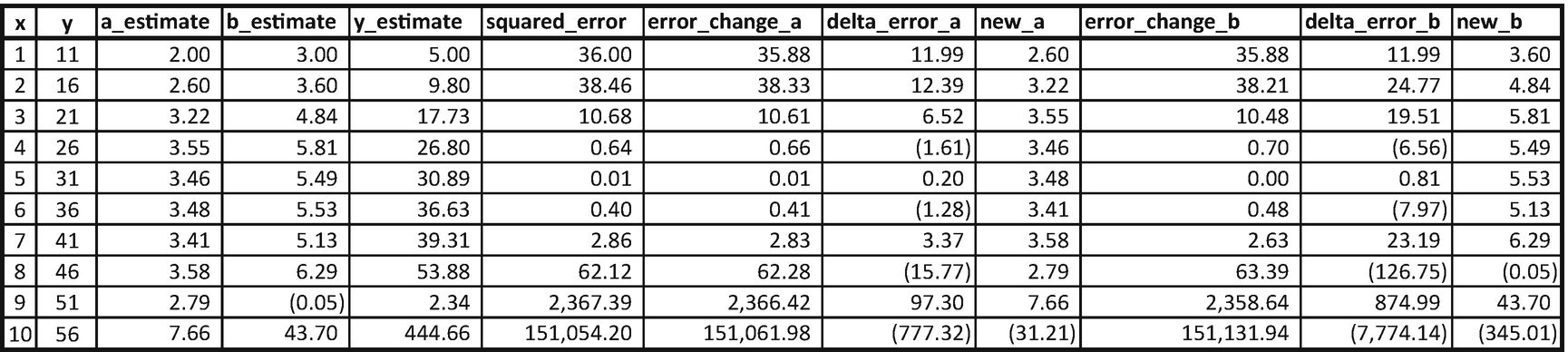

Why Have a Learning Rate?

Note that the moment the learning rate changed from 0.01 to 0.05, in this particular case, the values of a and b started to have abnormal variations over the latter data points. Thus, a lower learning rate is always preferred. However, note that a lower learning rate would result in a longer time (more iterations) to get the optimal results.

Batch Training

x | y | a_estimate | b_estimate | y_estimate | squared error | error_change_a | delta_error_a | new_a | error_change_b | delta_error_b | new_b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 36 | 35.8801 | 11.99 | 35.8801 | 11.99 | ||

2 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 64 | 63.8401 | 15.99 | 63.6804 | 31.96 | ||

Overall | 100 | 99.7202 | 27.98 | 2.2798 | 99.5605 | 43.95 | 3.4395 |

x | y | a_estimate | b_estimate | y_estimate | squared error | error_change_a | delta_error_a | new_a | error_change_b | delta_error_b | new_b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

3 | 21 | 2.28 | 3.44 | 12.60 | 70.59 | 70.42 | 16.79 | 70.09 | 50.32 | ||

4 | 26 | 2.28 | 3.44 | 16.04 | 99.25 | 99.05 | 19.91 | 98.45 | 79.54 | ||

Overall | 169.83 | 169.47 | 36.71 | 2.65 | 168.54 | 129.86 | 4.74 |

The updated values of a and b are now 2.65 and 4.74, and the iterations continue. Note that, in practice, batch size is at least 32.

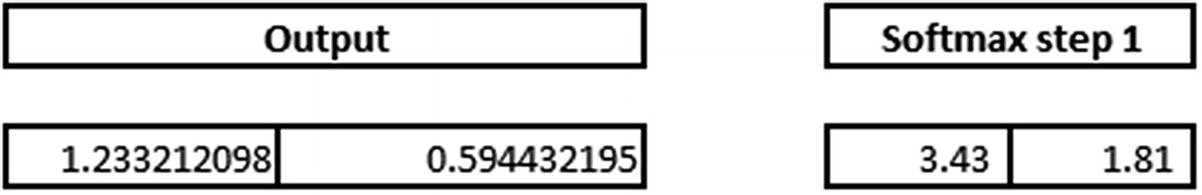

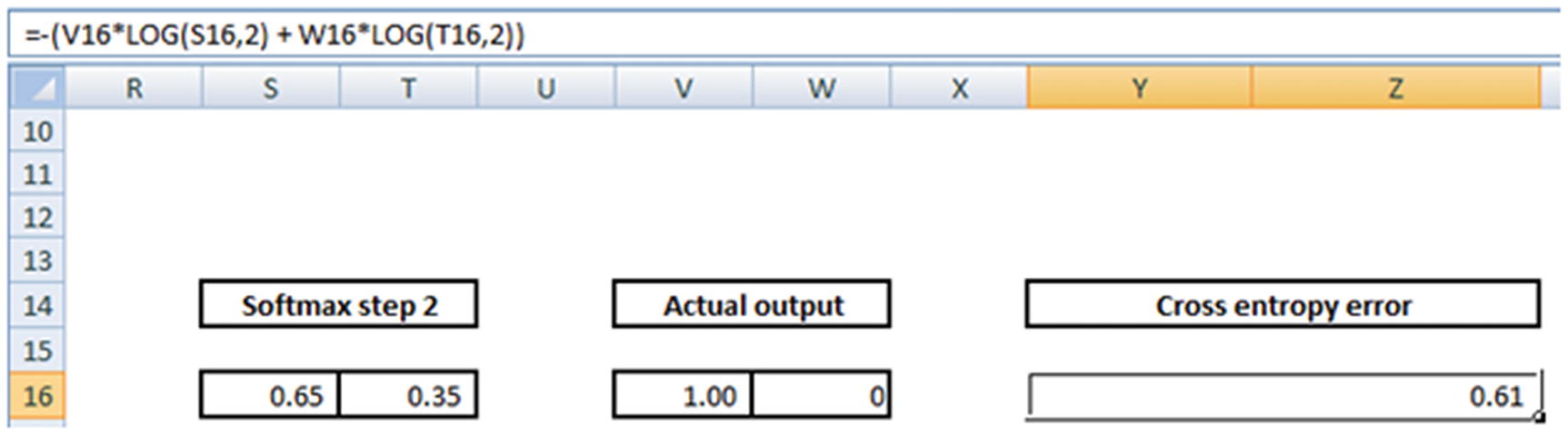

The Concept of Softmax

So far, in the Excel implementations, we have performed regression and not classification. They key difference to note when we perform classification is that the output is bound between 0 and 1. In the case of a binary classification, the output layer would have two nodes instead of one. One node corresponds to an output of 0, and the other corresponds to an output of 1.

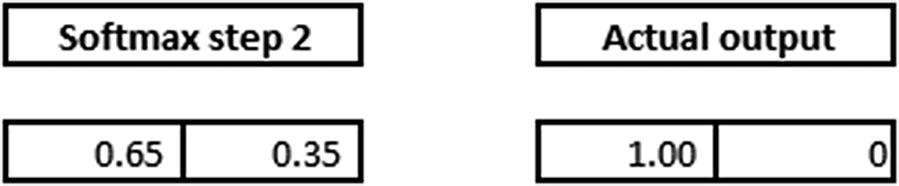

Now we’ll look at how our calculation changes for the discussion in the previous section (where the input is 1,1 and the expected output is 0) when the output layer has two nodes. Given that the output is 0, we will one-hot-encode the output as follows: [1,0], where the first index corresponds to an output of 0 and the second index value corresponds to an output of 1.

The one issue with the preceding output is that it has values that are >1 (in other cases, the values could be <0 as well).

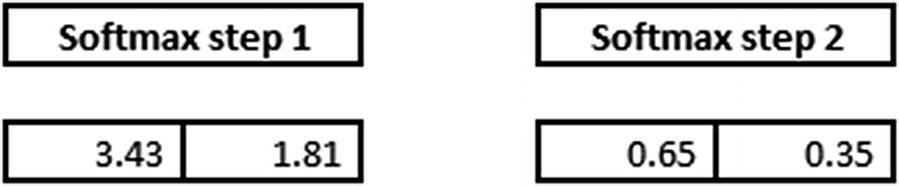

Softmax activation comes in handy in such scenario, where the output is beyond the expected value between 0 and 1. Softmax of the above output is calculated as follows:

Note that the value of 0.65 is obtained by 3.43 / (3.43 + 1.81).

- 1.The final softmax step is compared with actual output:

- 2.The cross entropy error is calculated based on the actual values and the predicted values (which are obtained from softmax step 2):

Note the formula for cross entropy error in the formula pane.

Now that we have the final error measure, we deploy gradient descent again to minimize the overall cross entropy error.

Different Loss Optimization Functions

Mean squared error

Mean absolute percentage error

Mean squared logarithmic error

Squared hinge

Hinge

Categorical hinge

Logcosh

Categorical cross entropy

Sparse categorical cross entropy

Binary cross entropy

Kullback Leibler divergence

Poisson

Cosine proximity

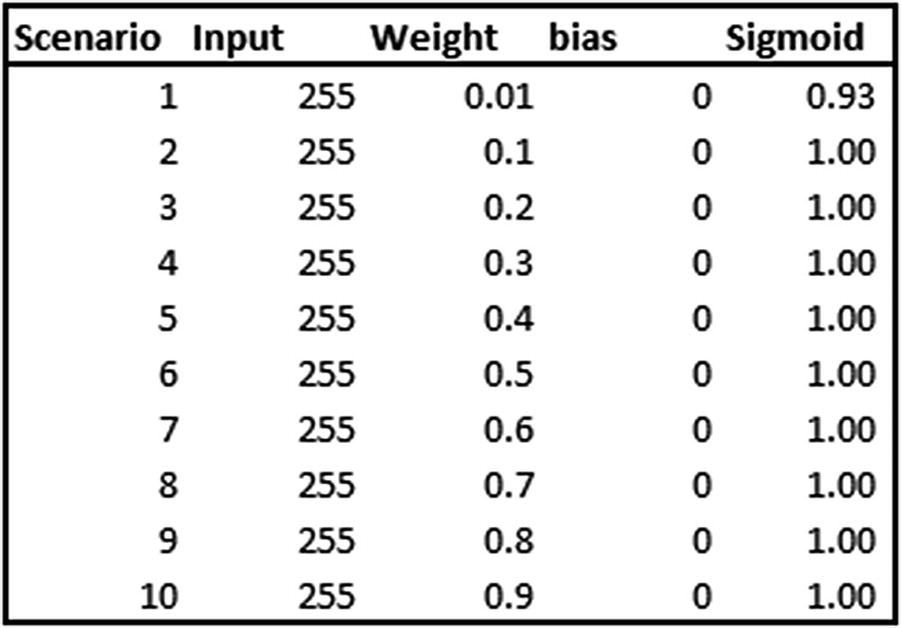

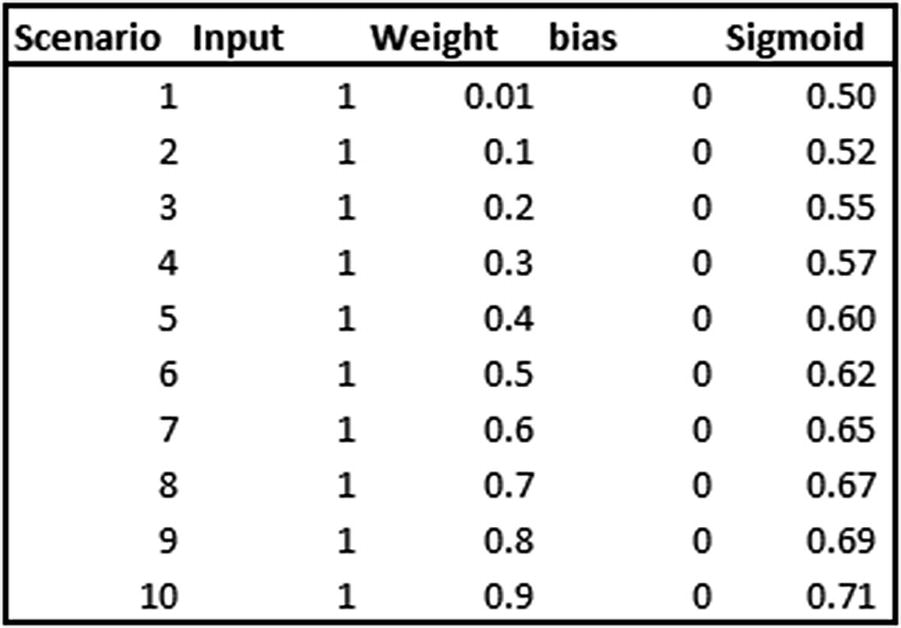

Scaling a Dataset

Typically, neural networks perform well when we scale the input datasets. In this section, we’ll look at the reason for scaling. To see the impact of scaling on outputs, we’ll contrast two scenarios .

Scenario Without Scaling the Input

In the preceding table, various scenarios are calculated where the input is always the same, 255, but the weight that multiplies the input is different in each scenario. Note that the sigmoid output does not change, even though the weight varies by a lot. That’s because the weight is multiplied by a large number, the output of which is also a large number.

Scenario with Input Scaling

Now that weights are multiplied by a smaller number, sigmoid output differs by quite a bit for differing weight values.

The problem with a high magnitude of independent variables is significant as the weights need to be adjusted slowly to arrive at the optimal weight value. Given that the weights get adjusted slowly (per the learning rate in gradient descent), it may take considerable time to arrive at the optimal weights when the input is a high magnitude number. Thus, to arrive at an optimal weight value, it is always better to scale the dataset first so that we have our inputs as a small number.

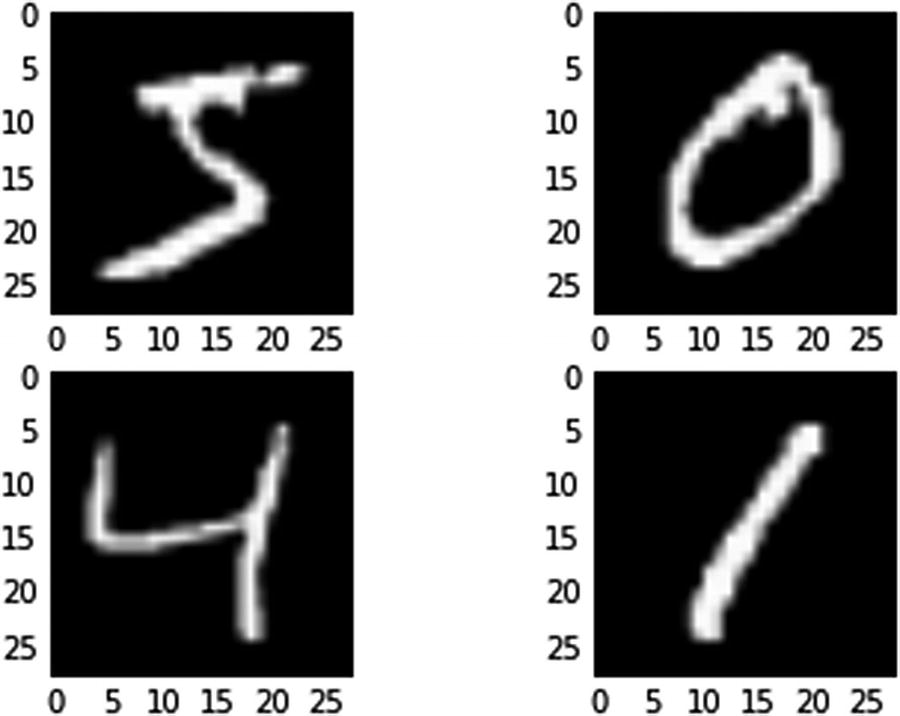

Implementing Neural Network in Python

- 1.

Download the dataset and extract the train and test dataset (code available as “NN.ipynb” in github)

from keras.datasets import mnistimport matplotlib.pyplot as plt%matplotlib inline# load (downloaded if needed) the MNIST dataset(X_train, y_train), (X_test, y_test) = mnist.load_data()# plot 4 images as gray scaleplt.subplot(221)plt.imshow(X_train[0], cmap=plt.get_cmap('gray'))plt.subplot(222)plt.imshow(X_train[1], cmap=plt.get_cmap('gray'))plt.subplot(223)plt.imshow(X_train[2], cmap=plt.get_cmap('gray'))plt.subplot(224)plt.imshow(X_train[3], cmap=plt.get_cmap('gray'))# show the plotplt.show() Figure 7-8

Figure 7-8The output

- 2.

Import the relevant packages:

import numpy as npfrom keras.datasets import mnistfrom keras.models import Sequentialfrom keras.layers import Densefrom keras.layers import Dropoutfrom keras.utils import np_utils - 3.

Pre-process the dataset:

num_pixels = X_train.shape[1] * X_train.shape[2]# reshape the inputs so that they can be passed to the vanilla NNX_train = X_train.reshape(X_train.shape[0],num_pixels ).astype('float32')X_test = X_test.reshape(X_test.shape[0],num_pixels).astype('float32')# scale inputsX_train = X_train / 255X_test = X_test / 255# one hot encode the outputy_train = np_utils.to_categorical(y_train)y_test = np_utils.to_categorical(y_test)num_classes = y_test.shape[1] - 4.

Build a model:

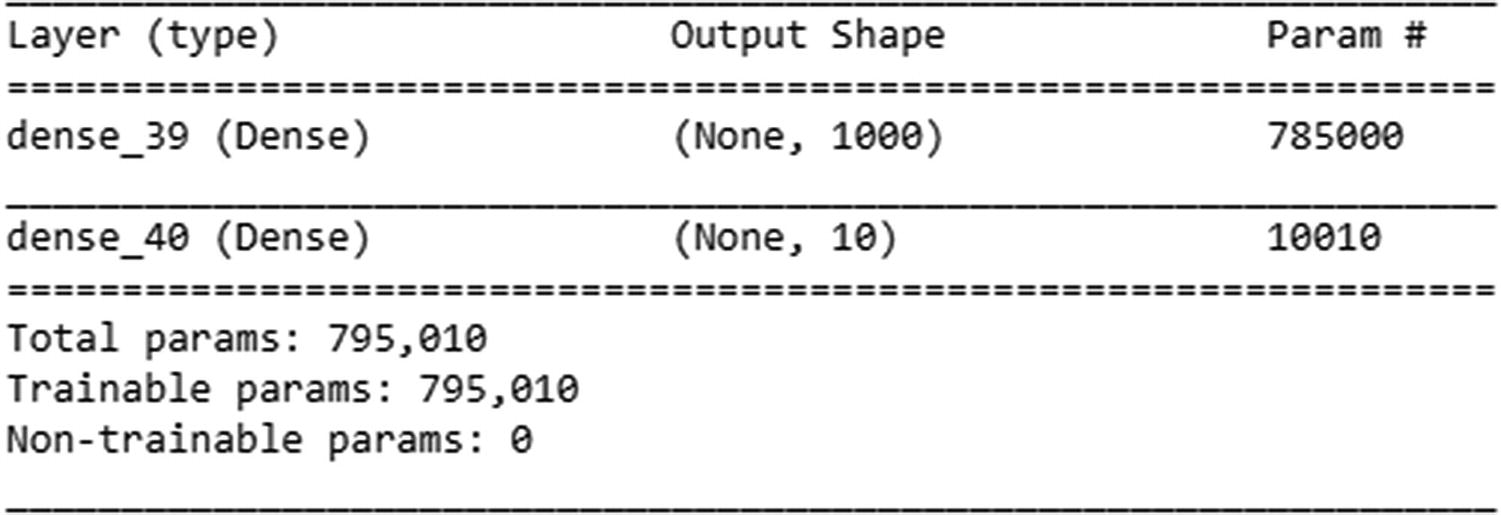

# building the modelmodel = Sequential()# add 1000 units in the hidden layer# apply relu activation in hidden layermodel.add(Dense(1000, input_dim=num_pixels,activation='relu'))# initialize the output layermodel.add(Dense(num_classes, activation="softmax"))# compile the modelmodel.compile(loss='categorical_crossentropy', optimizer="adam", metrics=['accuracy'])# extract the summary of modelmodel.summary()

- 5.

Run the model:

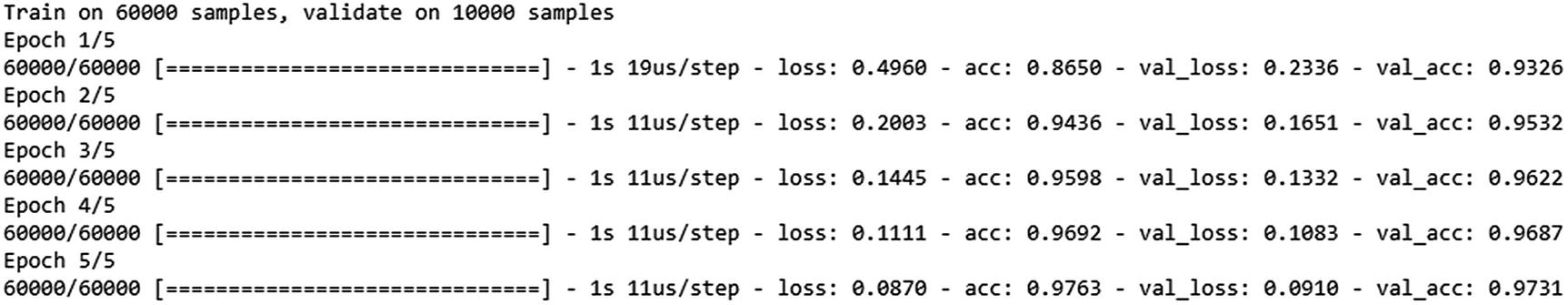

model.fit(X_train, y_train, validation_data=(X_test, y_test), epochs=5, batch_size=1024, verbose=1)

Note that as the number of epochs increases, accuracy on the test dataset increases as well. Also, in keras we only need to specify the input dimensions in the first layer, and it automatically figures the dimensions for the rest of the layers.

Avoiding Over-fitting using Regularization

Even though we have scaled the dataset, neural networks are likely to overfit on training dataset, as, the loss function (squared error or cross entropy error) ensures that loss is minimized over increasing number of epochs.

However, while training loss keeps on decreasing, it is not necessary that loss on test dataset is also decreasing. With more number of weights (parameters) in a neural network, the chances of over-fitting on training dataset and thus not generalizing on an unseen test dataset is high.

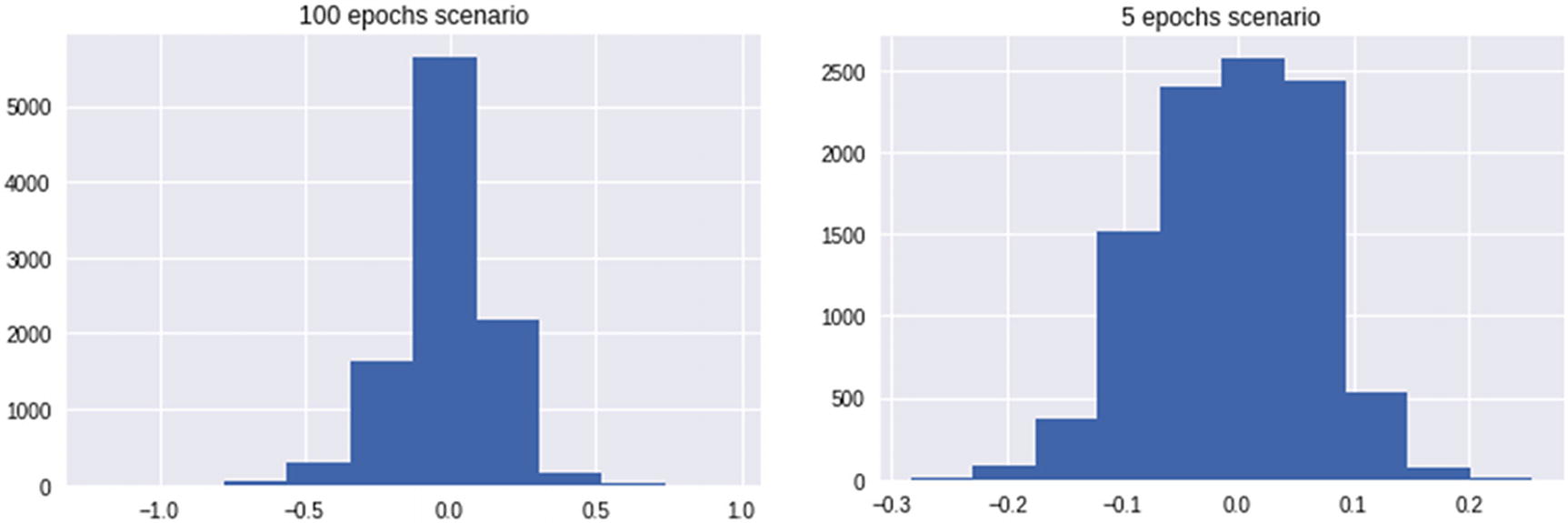

Let us contrast two scenario using the same neural network architecture on MNIST dataset, where in scenario A we consider 5 epochs and thus less chances of over-fitting, while in scenario B, we consider 100 epochs and thus more chances of over-fitting (code available as “Need for regularization in neural network.ipynb” in github).

We should notice that the difference between training and test dataset accuracy is less in the initial few epochs, but as the number of epochs increase, accuracy on training dataset increases, while the test dataset accuracy might not increase after some epochs.

Scenario | Training dataset | Test dataset |

5 epochs | 97.57% | 97.27% |

100 epochs | 100% | 98.28% |

100 epochs scenario had higher weight range, as it was trying to adjust for the edge cases in training dataset over the later epochs, while 5 epochs scenario did not have the opportunity to adjust for the edge cases. While training dataset’s edge cases got covered by the weight updates, it is not necessary that test dataset edge cases behave similarly and thus might not have got covered by weight updates. Also, note that an edge case in training dataset can be covered by giving a very high weightage to certain pixels and thus moving quickly towards saturating to either 1 or 0 of the sigmoid curve.

Thus, having high weight values are not desirable for generalization purposes. Regularization comes in handy in such scenario.

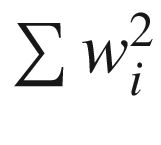

Regularization penalizes for having high magnitude of weights. The major types of regularization used are - L1 & L2 regularization

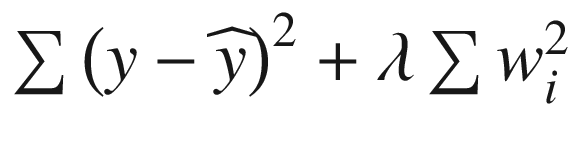

L2 regularization adds the additional cost term to error (loss function) as

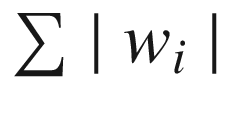

L1 regularization adds the additional cost term to error (loss function) as

This way, we make sure that weights cannot be adjusted to have a high value so that they work for extreme edge cases in only train dataset.

Assigning Weightage to Regularization term

We notice that our modified loss function, in case of L2 regularization is as follows:

Overall Loss =

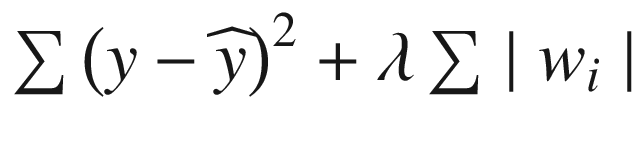

where  is the weightage associated with the regularization term and is a hyper-parameter that needs to be tuned. Similarly, overall loss in case of L1 regularization is as follows:

is the weightage associated with the regularization term and is a hyper-parameter that needs to be tuned. Similarly, overall loss in case of L1 regularization is as follows:

Overall Loss =

L1/ L2 regularization is implemented in Python as follows:

Notice that, the above involves, invoking an additional hyper-parameter - “kernel_regularizer” and then specifying whether it is an L1 / L2 regularization. Further we also specify the  value that gives the weightage to regularization.

value that gives the weightage to regularization.

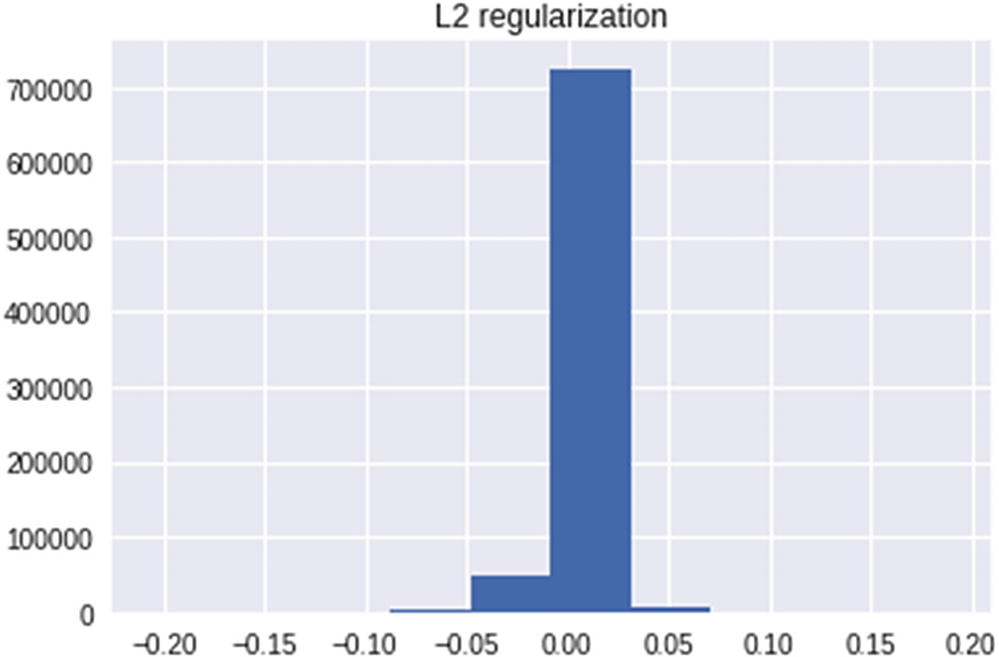

We notice that a majority of weights are now much closer to 0 when compared to the previous two scenarios and thus avoiding the overfitting issue that was caused due to high weight values assigned for edge cases. We would see a similar trend in case of L1 regularization.

Thus, L1 and L2 regularizations help us in avoiding the issue of overfitting on top of training dataset but not generalizing on test dataset.

Implementing Neural Network in R

Similar to the way we implemented a neural network in Python, we will use the keras framework to implement neural network in R . As with Python, multiple packages help us achieve the result.

- 1.

Install the kerasR package:

install.packages("kerasR") - 2.

Load the installed package :

library(kerasR) - 3.

Use the MNIST dataset for analysis:

mnist <- load_mnist() - 4.

Examine the structure of the mnist object:

str(mnist)Note that by default the MNIST dataset has the train and test datasets split.

- 5.

Extract the train and test datasets:

mnist <- load_mnist()X_train <- mnist$X_trainY_train <- mnist$Y_trainX_test <- mnist$X_testY_test <- mnist$Y_test - 6.

Reshape the dataset.

Given that we are performing a normal neural network operation, our input dataset should be of the dimensions (60000,784), whereas X_train is of the dimension (60000,28,28):

X_train <- array(X_train, dim = c(dim(X_train)[1], 784))X_test <- array(X_test, dim = c(dim(X_test)[1], 784)) - 7.

Scale the datasets:

X_train <- X_train/255X_test <- X_test/255 - 8.

Convert the dependent variables (Y_train and Y_test) into categorical variables:

Y_train <- to_categorical(mnist$Y_train, 10)Y_test <- to_categorical(mnist$Y_test, 10) - 9.

Build a model :

model <- Sequential()model$add(Dense(units = 1000, input_shape = dim(X_train)[2],activation = "relu"))model$add(Dense(10,activation = "softmax"))model$summary() - 10.

Compile the model:

keras_compile(model, loss = 'categorical_crossentropy', optimizer = Adam(),metrics='categorical_accuracy') - 11.

Fit the model:

keras_fit(model, X_train, Y_train,batch_size = 1024, epochs = 5,verbose = 1, validation_data = list(X_test,Y_test))

The process we just went through should give us a test dataset accuracy of ~98%.

Summary

Neural network can approximate complex functions (because of the activation in hidden layers)

A forward and a backward propagation constitute the building blocks of the functioning of a neural network

Forward propagation helps us in estimating the error, whereas backward propagation helps in reducing the error

It is always a better idea to scale the input dataset whenever gradient descent is involved in arriving at the optimal weight values

L1/ L2 regularization helps in avoiding over-fitting by penalizing for high weight magnitudes