In Chapter 9, we looked at how convolutional neural networks (CNNs) improve upon the traditional neural network architecture for image classification. Although CNNs perform very well for image classification in which image translation and rotation are taken care of, they do not necessarily help in identifying temporal patterns. Essentially, one can think of CNNs as identifying static patterns.

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are designed to solve the problem of identifying temporal patterns.

Working details of RNN

Using embeddings in RNN

Generating text using RNN

Doing sentiment classification using RNN

Moving from RNN to LSTM

RNN examples

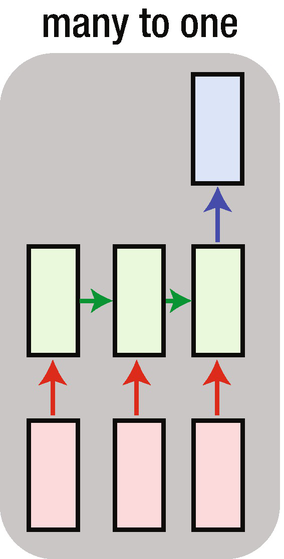

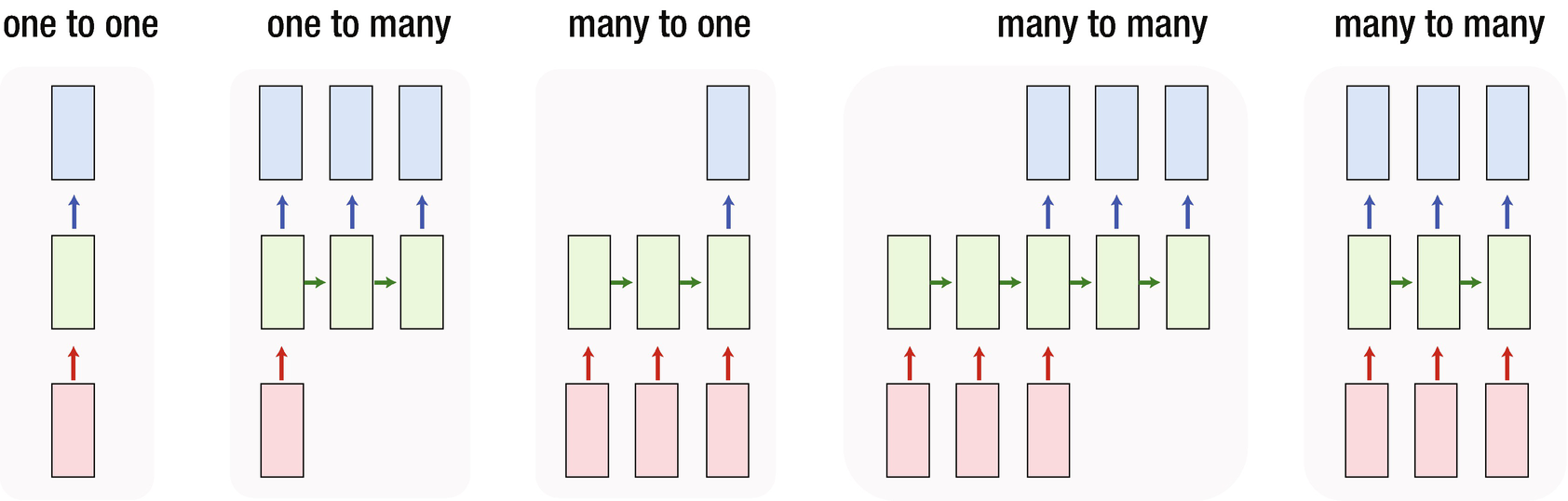

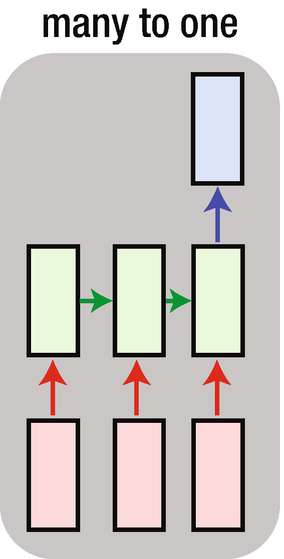

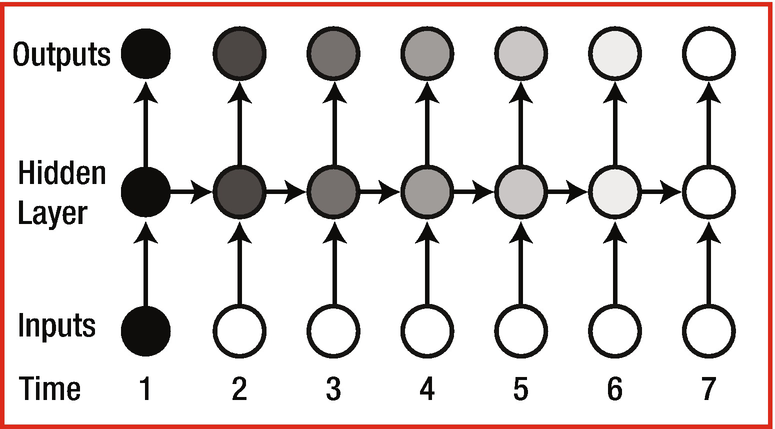

The boxes in the bottom are inputs

The boxes in the middle are hidden layers

The boxes at the top are outputs

An example of the one-to-one architecture shown is a typical neural network that we have looked at in chapter 7, with a hidden layer between the input and the output layer. An example of one-to-many RNN architecture would be to input an image and output the caption of the image. An example of many-to-one RNN architecture might be a movie review given as input and the movie sentiment (positive, negative or neutral review) as output. Finally, an example of many-to-many RNN architecture would be machine translation from one language to another language.

Understanding the Architecture

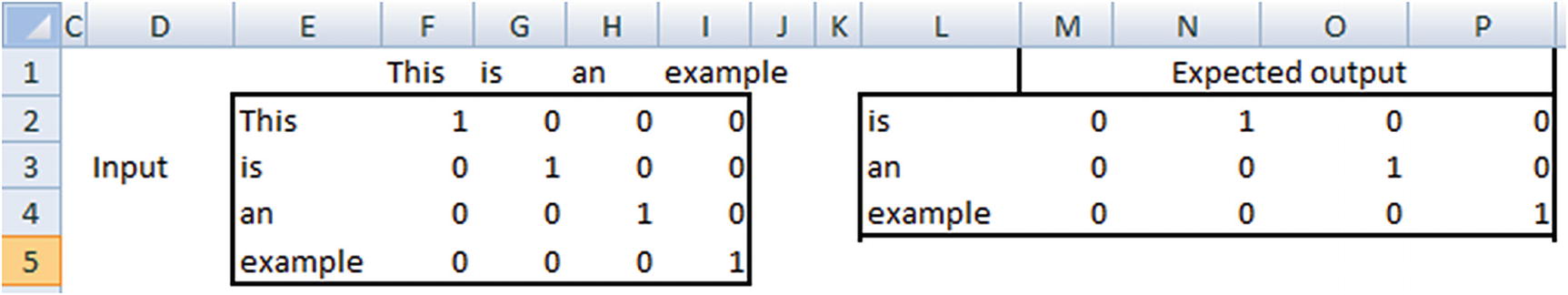

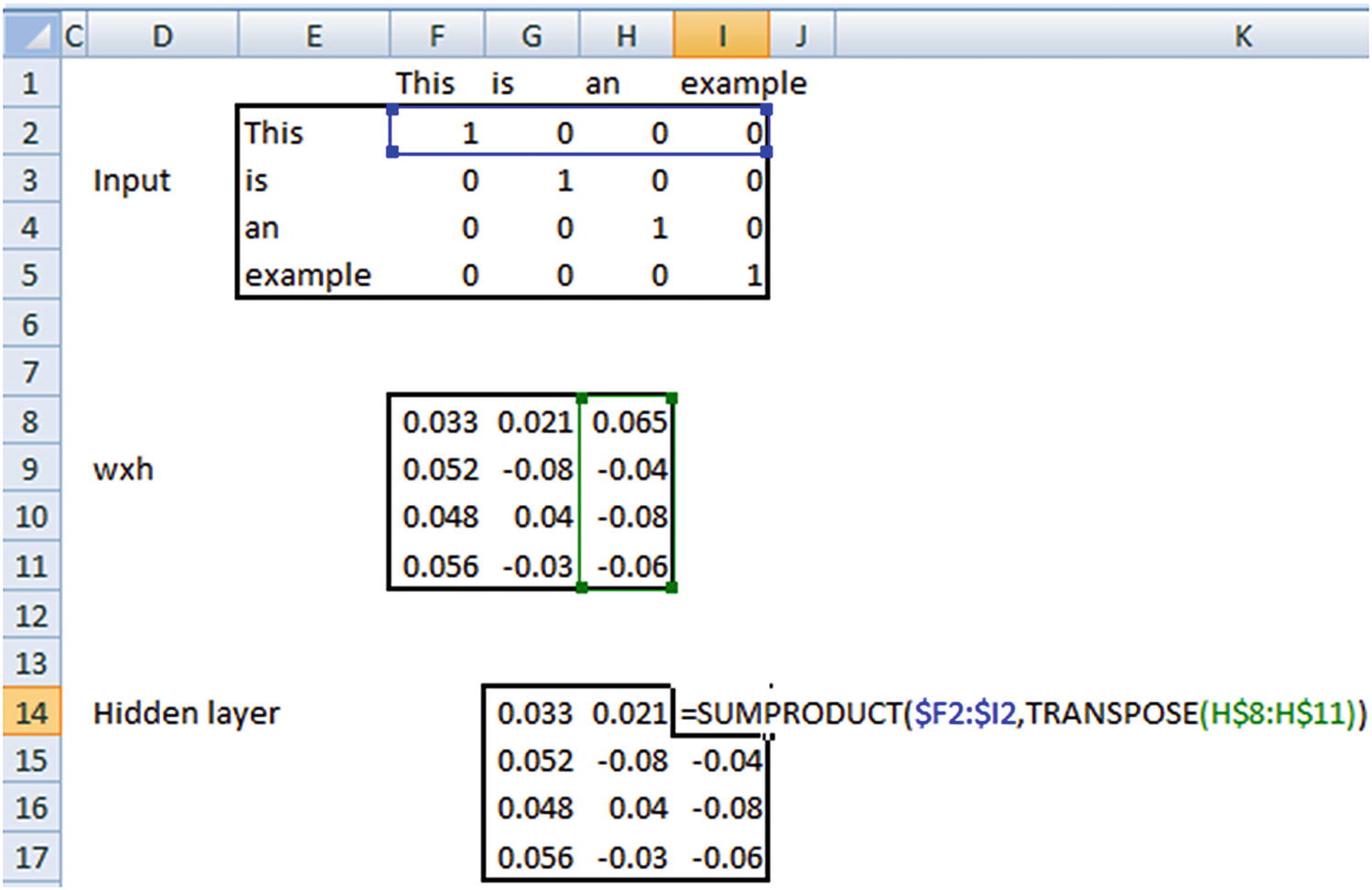

Let’s go through an example and look more closely at RNN architecture. Our task is as follows: “Given a string of words, predict the next word.” We’ll try to predict the word that comes after “This is an _____”. Let’s say the actual sentence is “This is an example.”

- 1.

Encode each word, leaving space for an extra word, if needed:

This: {1,0,0,0}is: {0,1,0,0}an: {0,0,1,0} - 2.

Encode the sentence:

"This is an": {1,1,1,0} - 3.

Create a training dataset:

Input --> {1,1,1,0}Output --> {0,0,0,1} - 4.

Build a model with input and output.

One of the major drawbacks here is that the input representation does not change if the input sentence is either “this is an” or “an is this” or “this an is”. We know that each of these is very different and cannot be represented by the same structure mathematically.

A change in the architecture

In the architecture shown in Figure 10-2, each of the individual words in the sentence goes into a separate box among the three input boxes. Moreover, the structure of the sentence is preserved since “this” gets into the first box, “is” gets into the second box, and “an” gets into the third box.

The output “example” is expected in the output box at the top.

Interpreting an RNN

Memory in the hidden layer

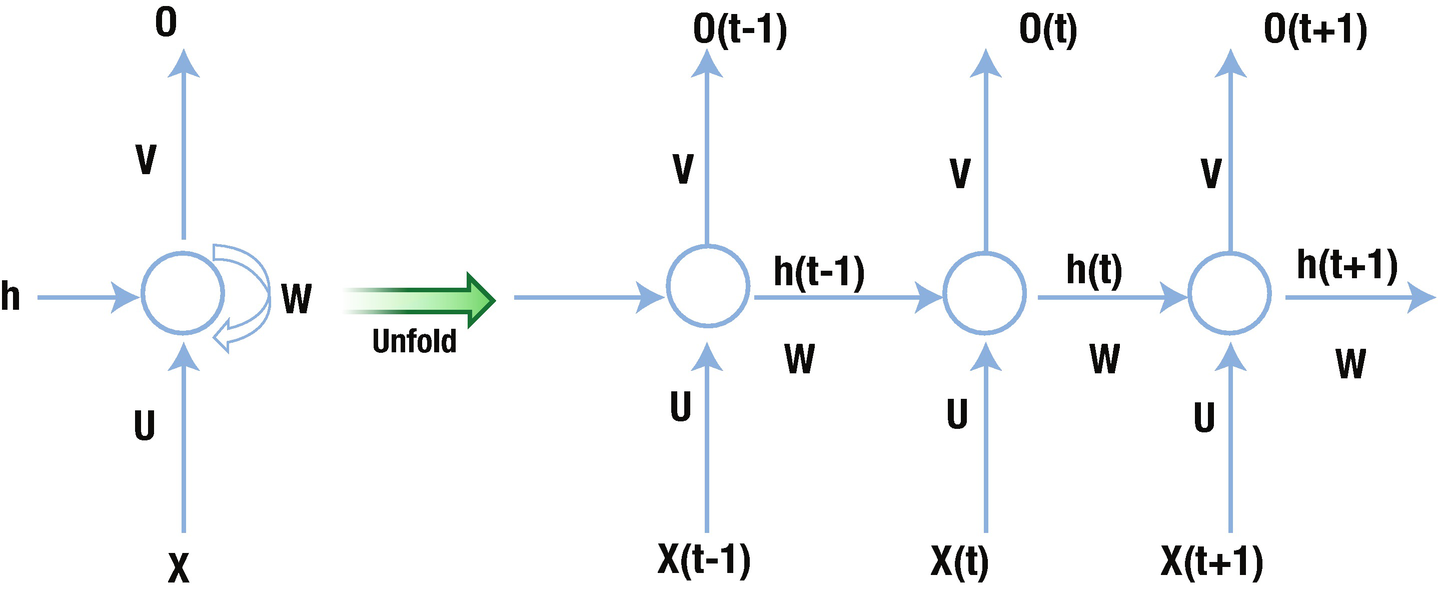

The network on the right in Figure 10-3 is an unrolled version of the network on the left. The network on the left is a traditional one, with one change: the hidden layer is connected to itself along with being connected to the input (the hidden layer is the circle in the figure).

Note that when a hidden layer is connected to itself along with input layer, it is connected to a “previous version” of the hidden layer and the current input layer. We can consider this phenomenon of the hidden layer being connect back to itself as the mechanism by which memory is created in RNN.

The weight U represents the weights that connect the input layer to the hidden layer, the weight W represents the hidden-layer-to-hidden-layer connection, and the weight V represents the hidden-layer-to-output-layer connection.

Why Store Memory?

There is a need to store memory because, in the preceding example and in text generation in general, the next word does not necessarily rely on the preceding word but the context of the few words preceding the word to predict.

Given that we are looking at the preceding words, there should be a way to keep them in memory so that we can predict the next word more accurately. Moreover, we should also have the memory in order—more often than not, more recent words are more useful in predicting the next word than the words that are far away from the word being predicted.

Working Details of RNN

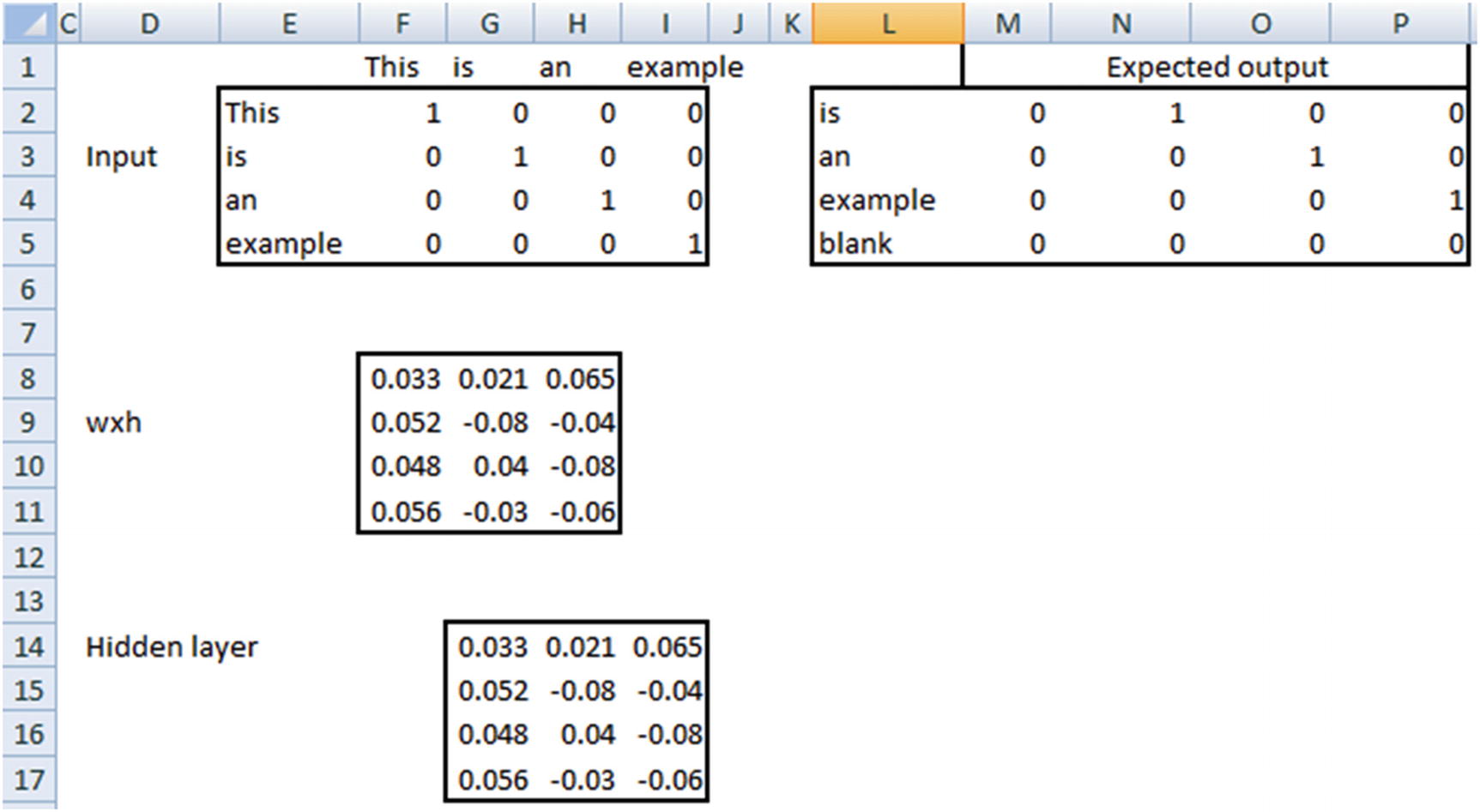

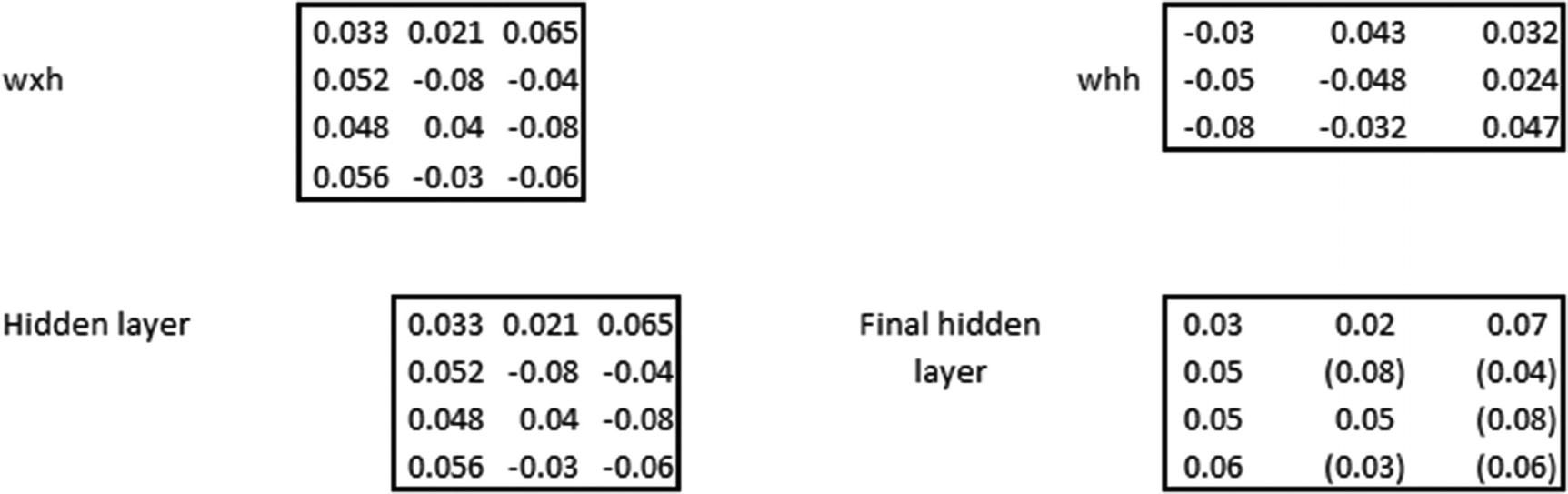

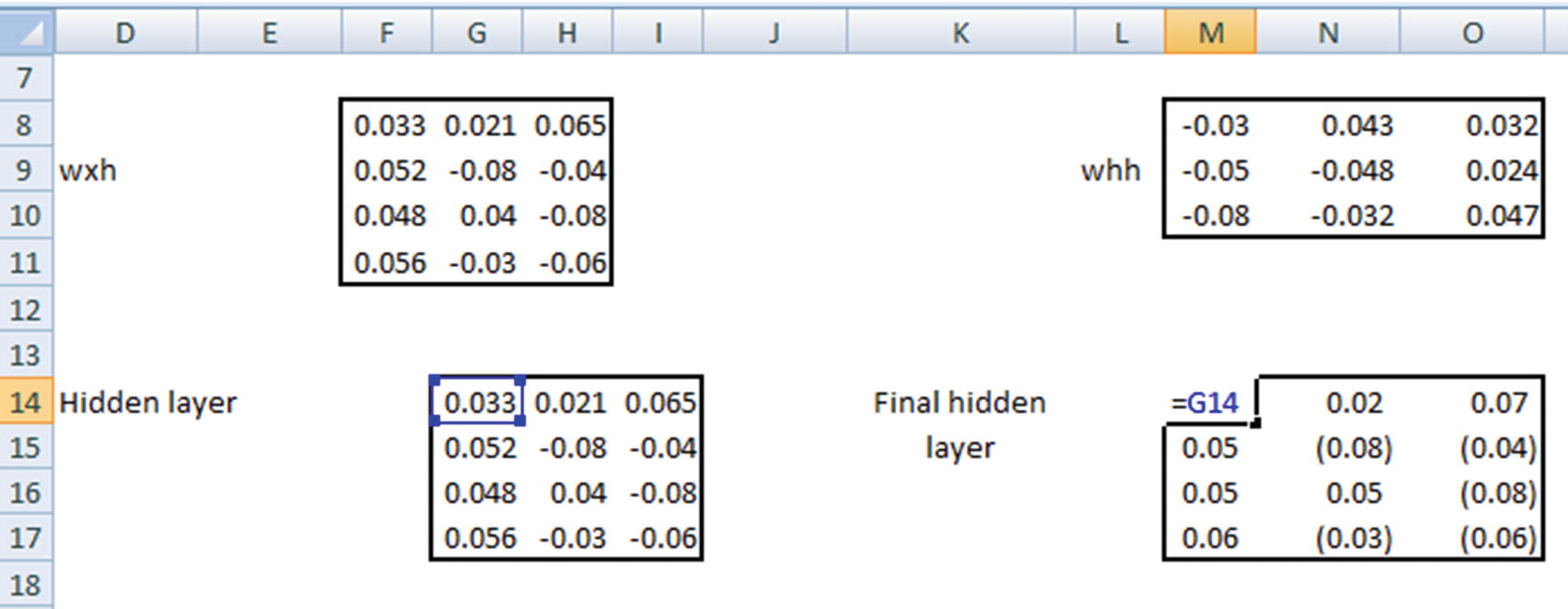

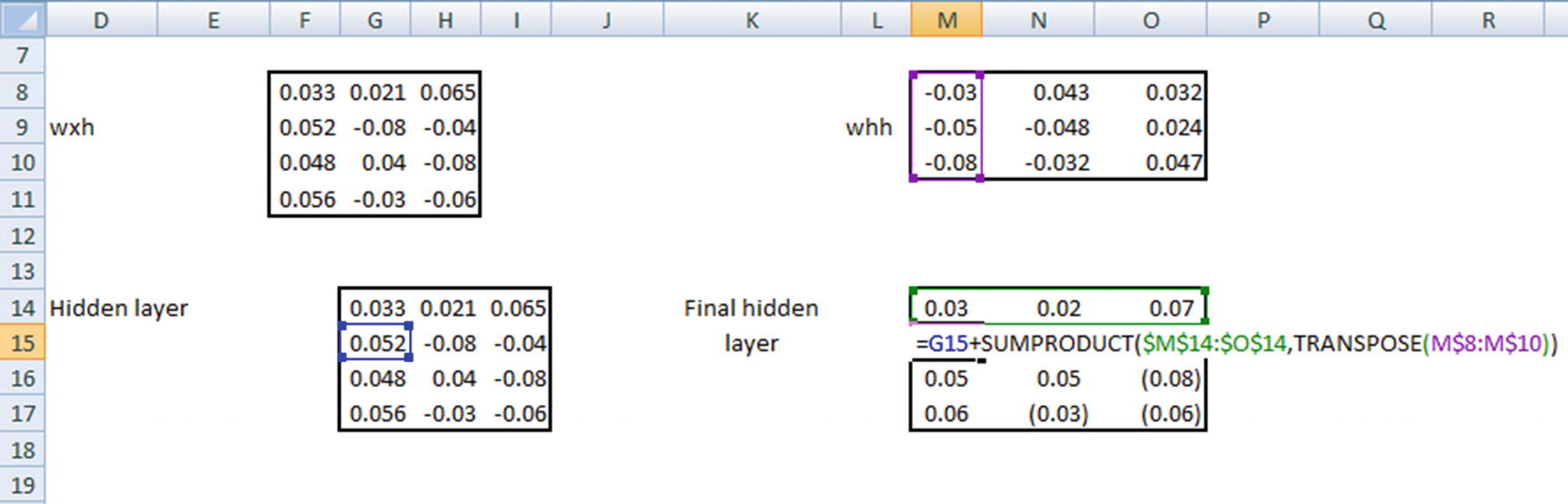

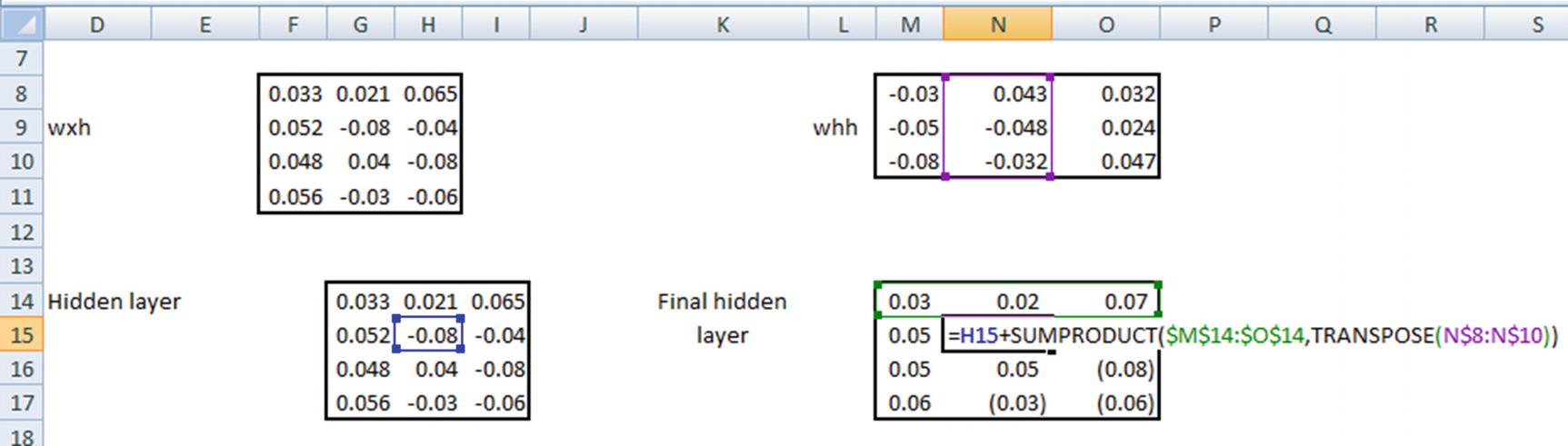

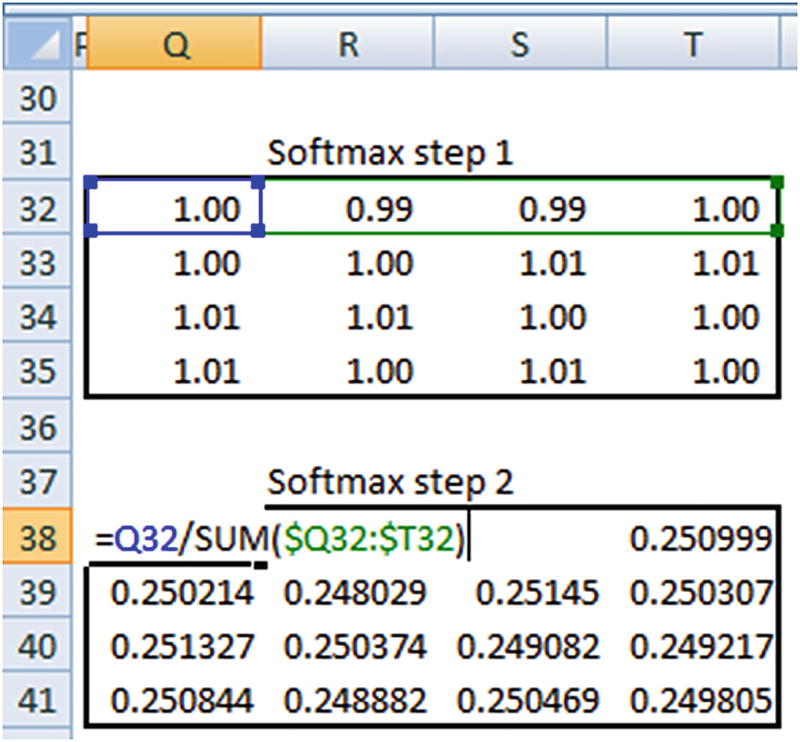

Note that a typical NN has an input layer followed by an activation in the hidden layer and then a softmax activation at the output layer. RNN is similar, but with memory. Let’s look at another example: “This is an example”. Given an input “This”, we are expected to predict “is” and similarly for an input “is”, we are expected to come up with a prediction of “an” and a prediction of “example” for “an” as input. The dataset is available as “RNN dimension intuition.xlsx” in github.

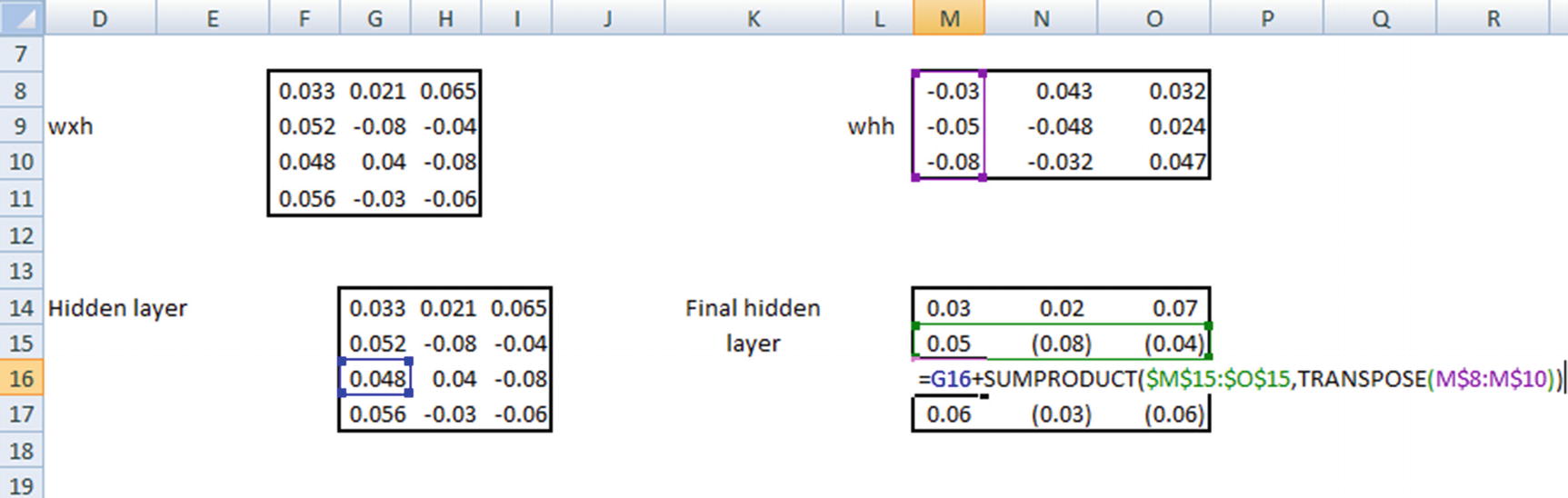

wxh is randomly initialized and 4 × 3 in dimension. Each input is 1 × 4 in dimension. Thus, the hidden layer, which is a matrix multiplication between the input and wxh, is 1 × 3 in dimension for each input row. The expected output is the one-hot encoded version of the word that comes next to the input word in our sentence. Note that, the last prediction “blank” is inaccurate because we have all 0s as expected output. Ideally, we would have a new column in the one-hot encoded version that takes care of all the unseen words. However, for the sake of understanding the working details of RNN we will keep it simple with 4 columns in expected output.

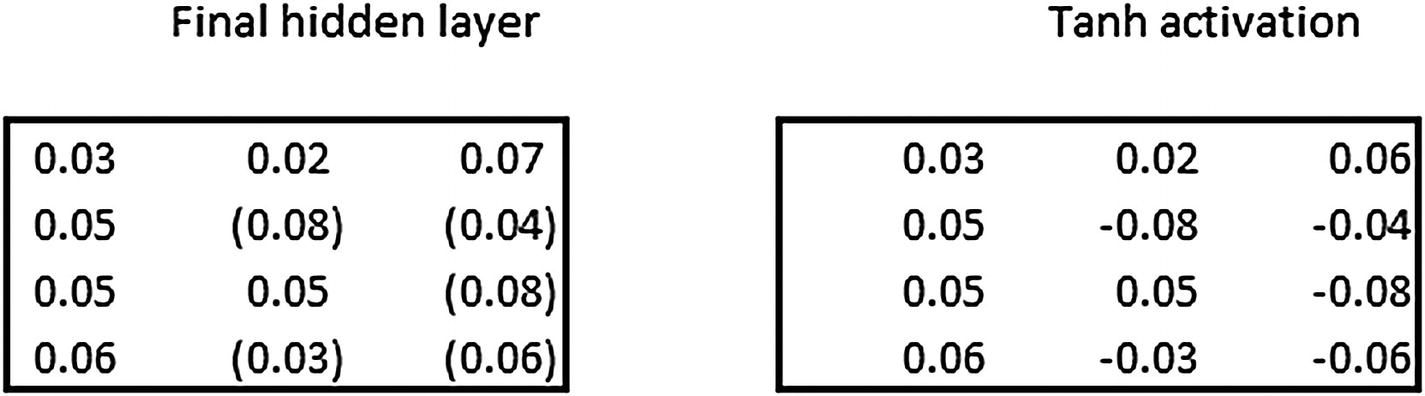

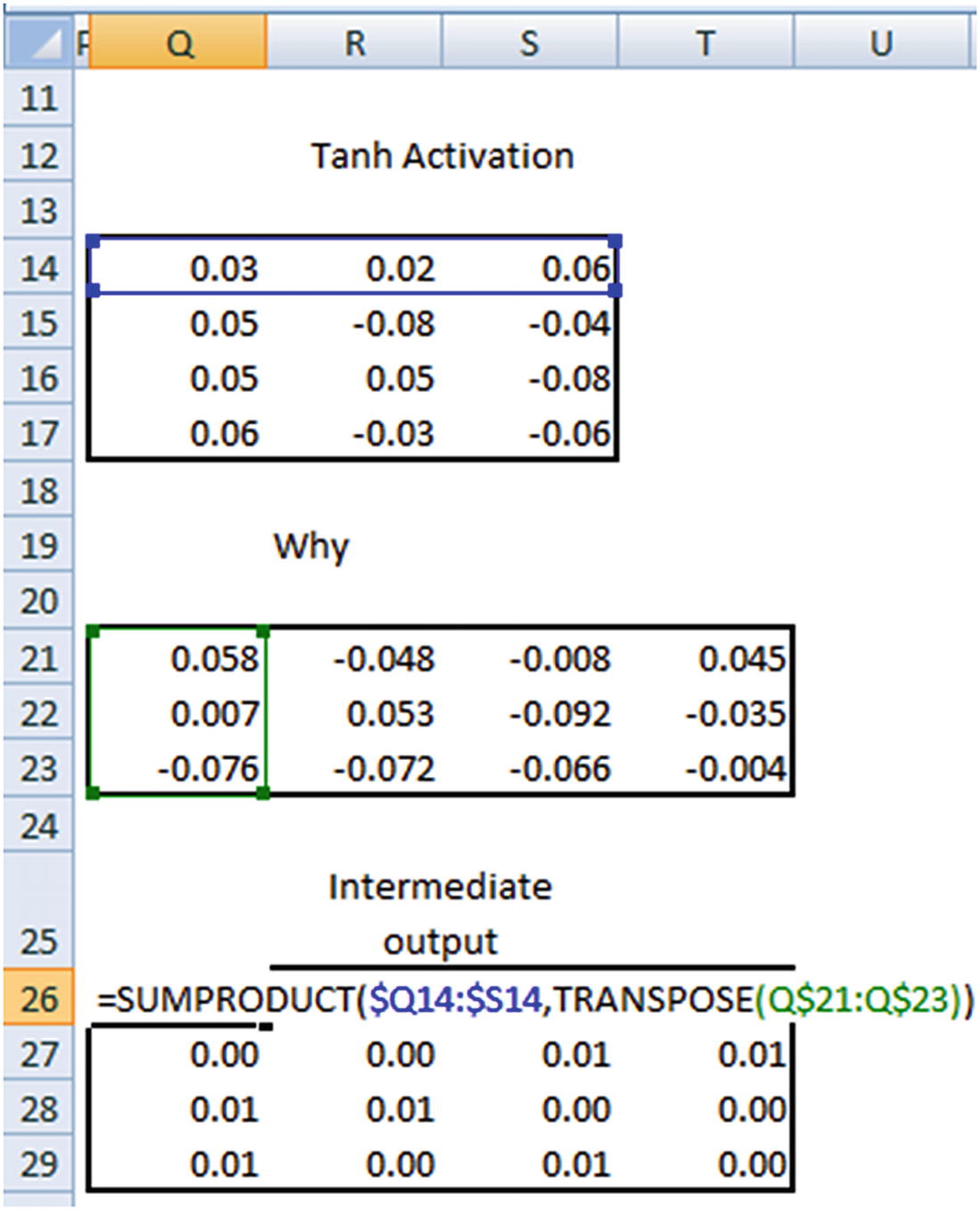

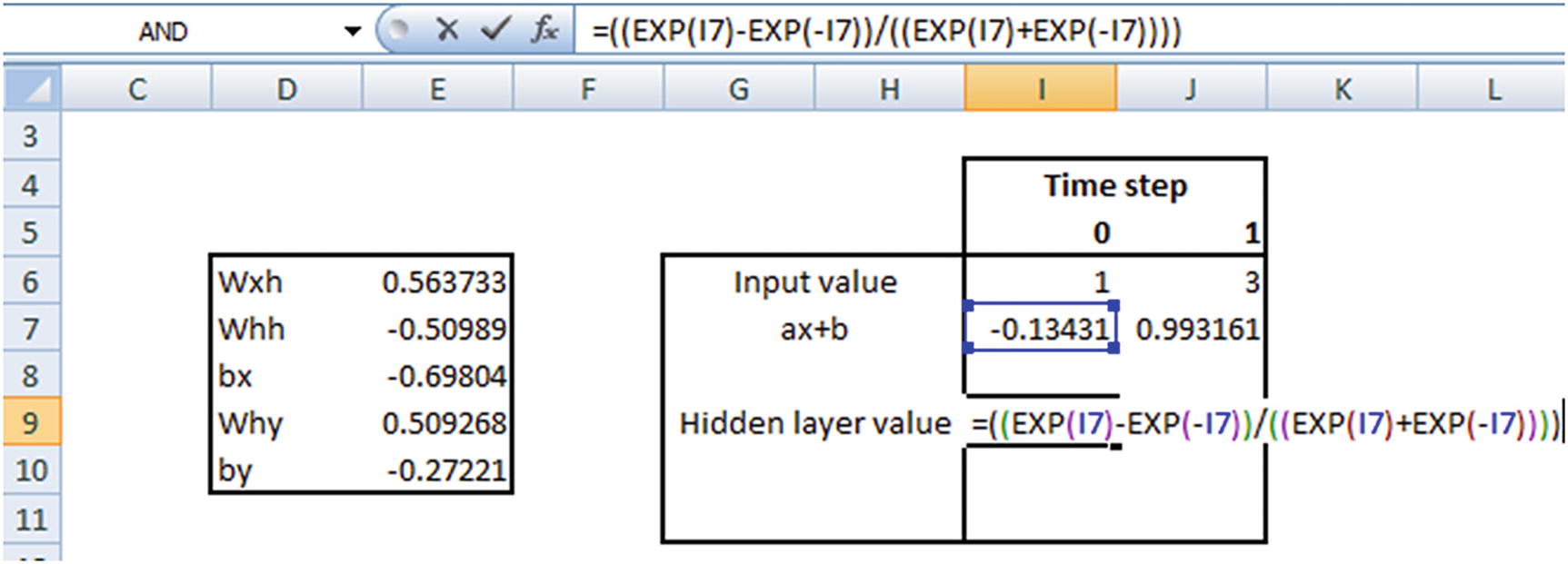

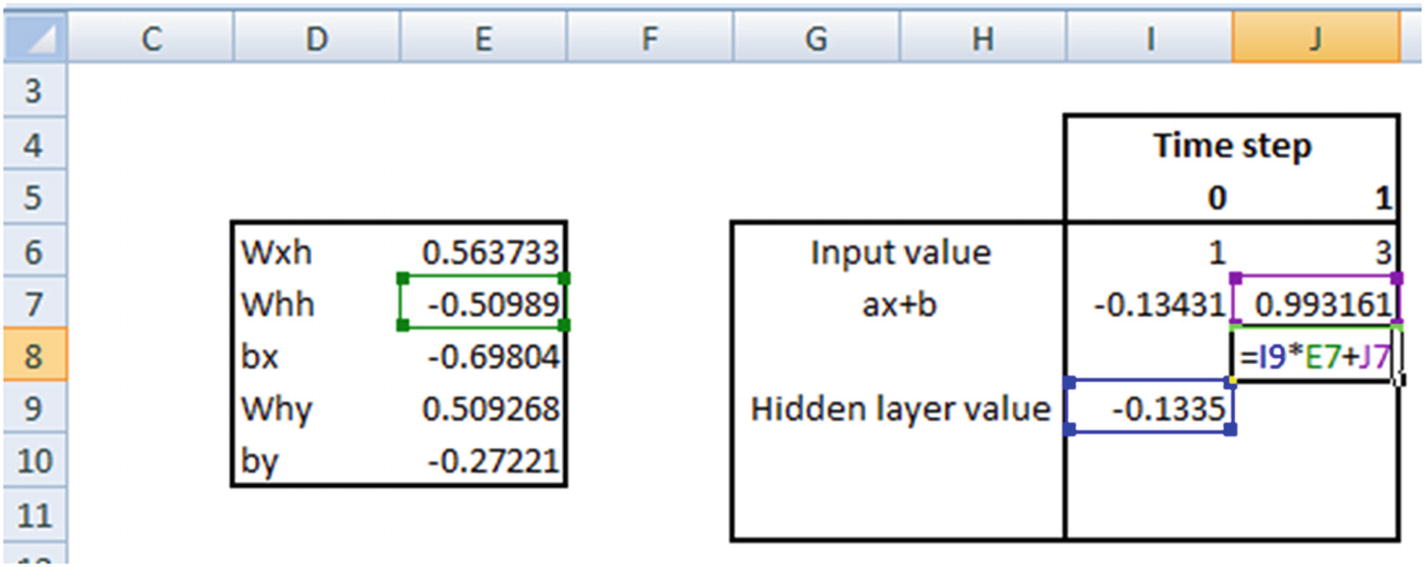

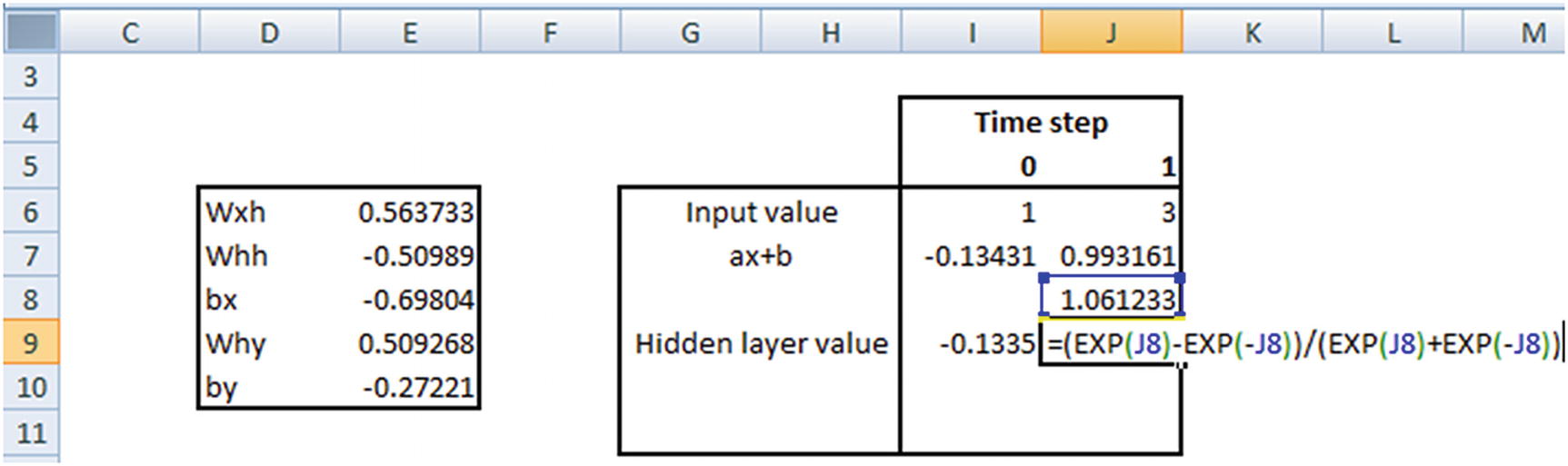

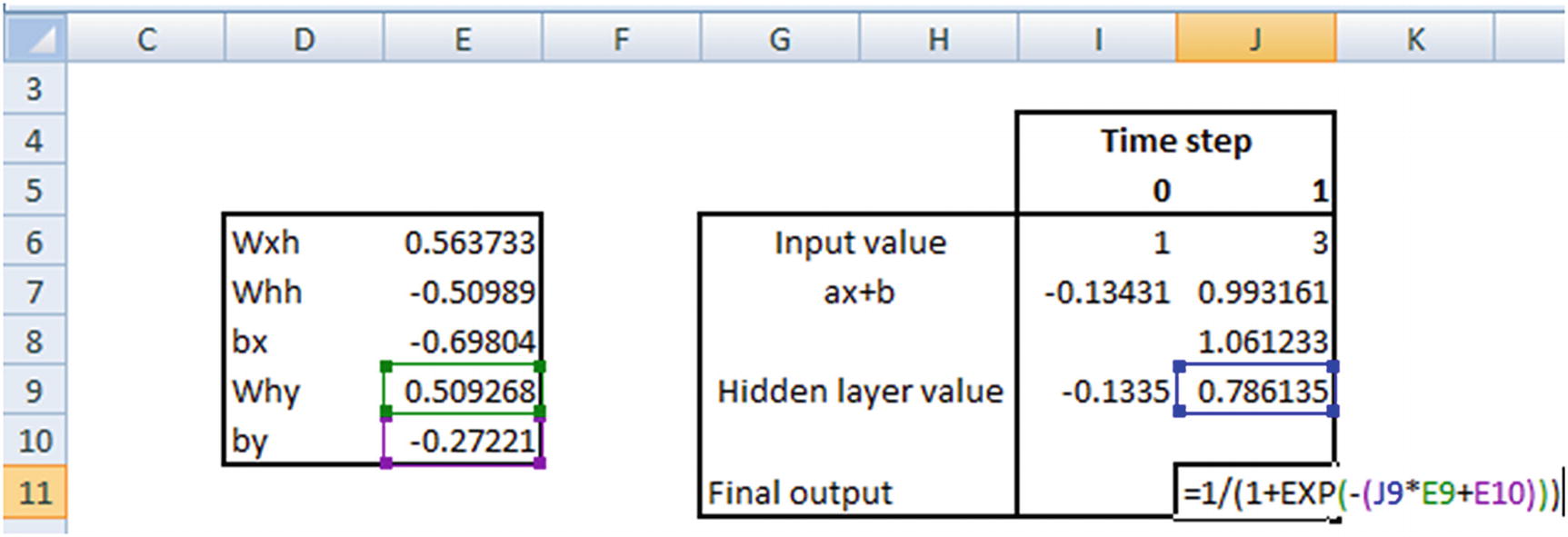

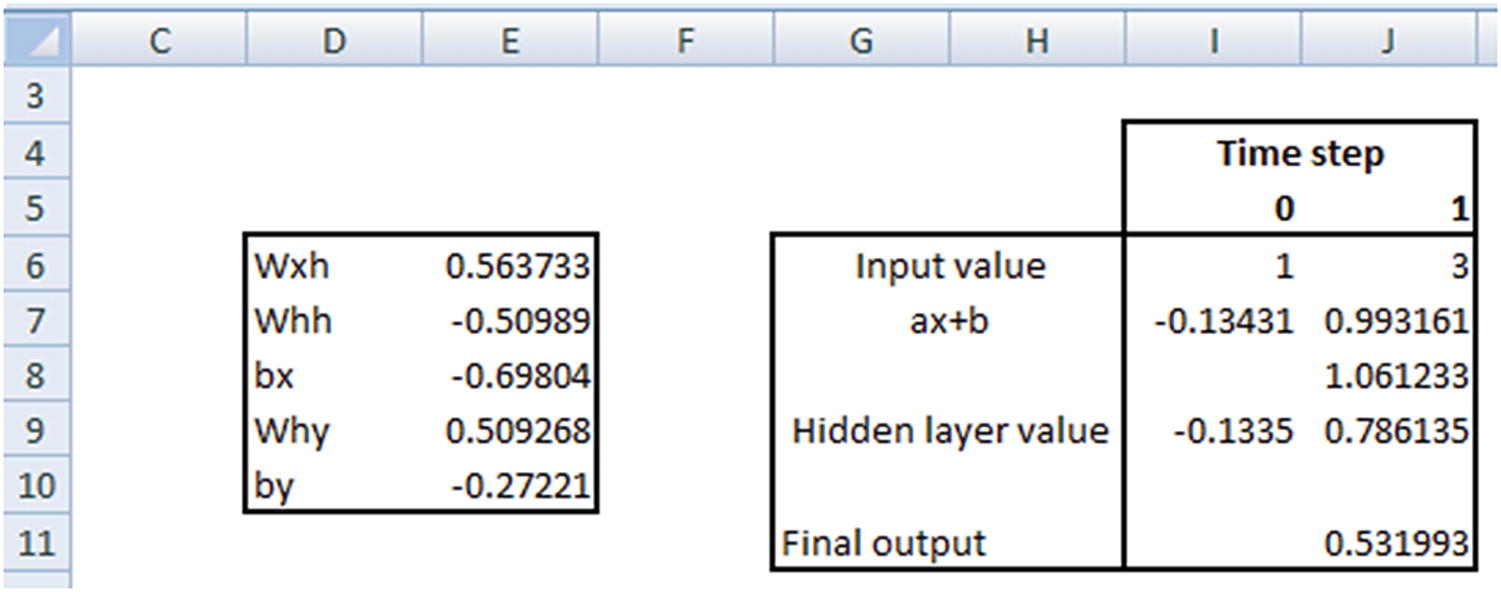

Note that, wxh and whh are random initializations, whereas the hidden layer and the final hidden layer are calculated. We will look at how the calculations are done in the following pages.

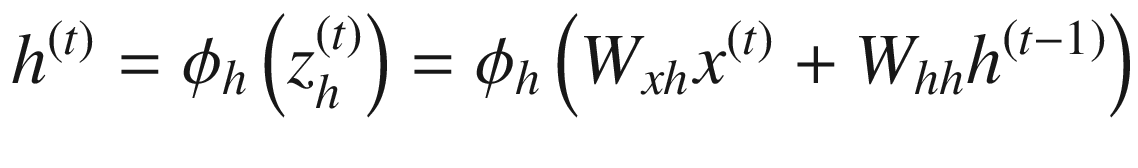

where  is an activation that is performed (tanh activation in general).

is an activation that is performed (tanh activation in general).

Matrix multiplication of the input layer and wxh.

Matrix multiplication of hidden layer and whh.

Final calculation of the hidden layer value at a given time step would be the summation of the preceding two matrix multiplications and passing the result through a tanh activation function.

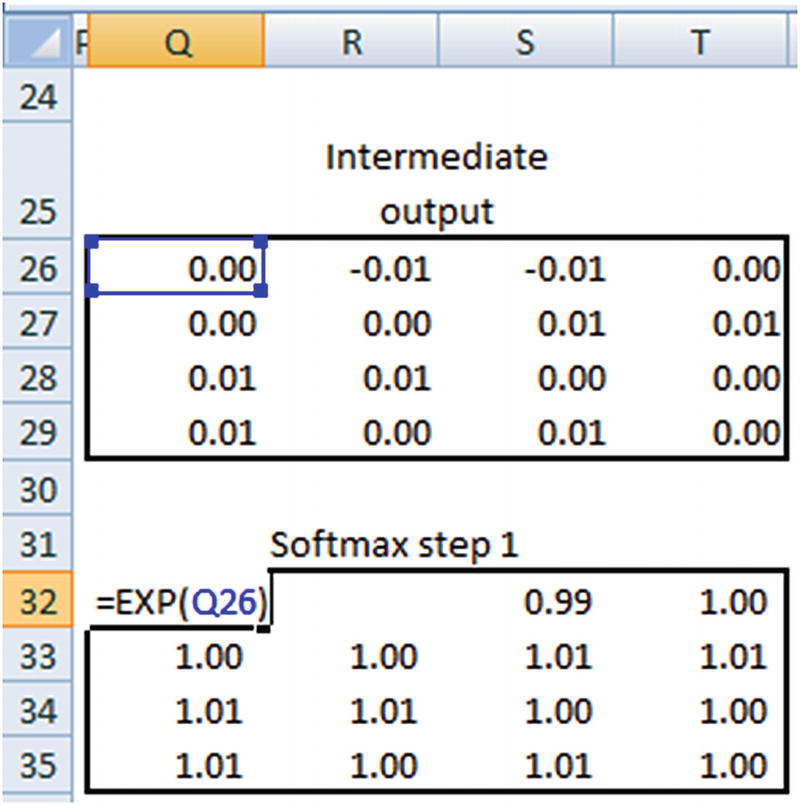

The following sections go through the calculation of the hidden layer value at different time steps.

Time Step 1

Time Step 2

Time Step 3

Similarly, the hidden layer values are calculated at the fourth time step.

Once the probabilities are obtained, the loss is calculated by taking the cross entropy loss between the prediction and actual output.

Finally, we will be minimizing the loss through the combination of forward and backward propagation epochs in a similar manner as that of NN.

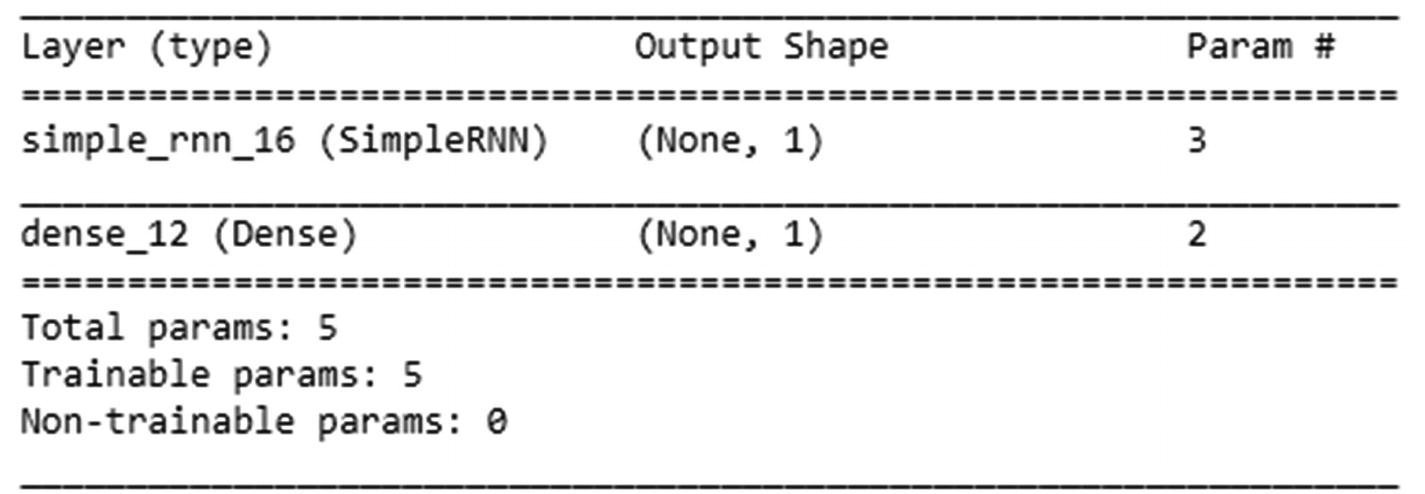

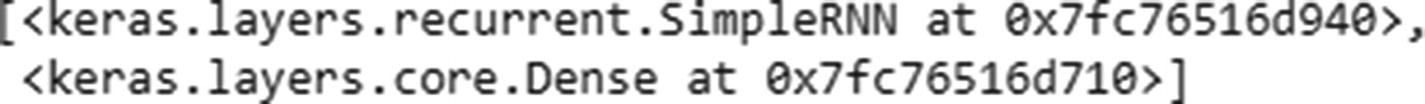

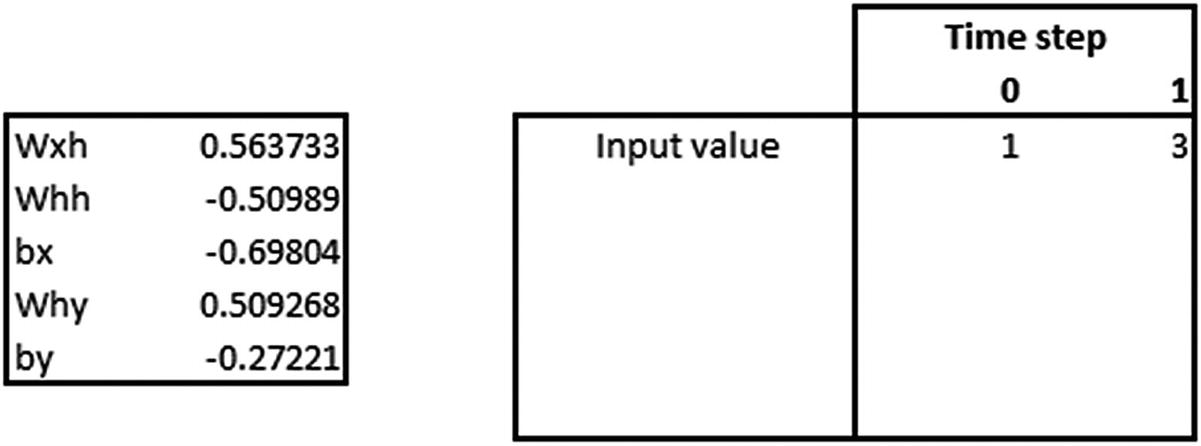

Implementing RNN: SimpleRNN

To see how RNN is implemented in keras, let’s go through a simplistic example (only to understand the keras implementation of RNN and then to solidify our understanding by implementing in Excel): classifying two sentences (which have an exhaustive list of three words). Through this toy example, we should be in a better position to understand the outputs quickly (code available as “simpleRNN.ipynb” in github):

Initialize the documents and encode the words corresponding to those documents :

Pad the documents to a maximum length of two words—this is to maintain consistency so that all the inputs are of the same size :

Compiling a Model

The input shape to the SimpleRNN function should be of the form (number of time steps, number of features per time step). Also, in general RNN uses tanh as the activation function. The following code specifies the input shape as (2,1) because each input is based on two time steps and each time step has only one column representing it. unroll=True indicates that we are considering previous time steps :

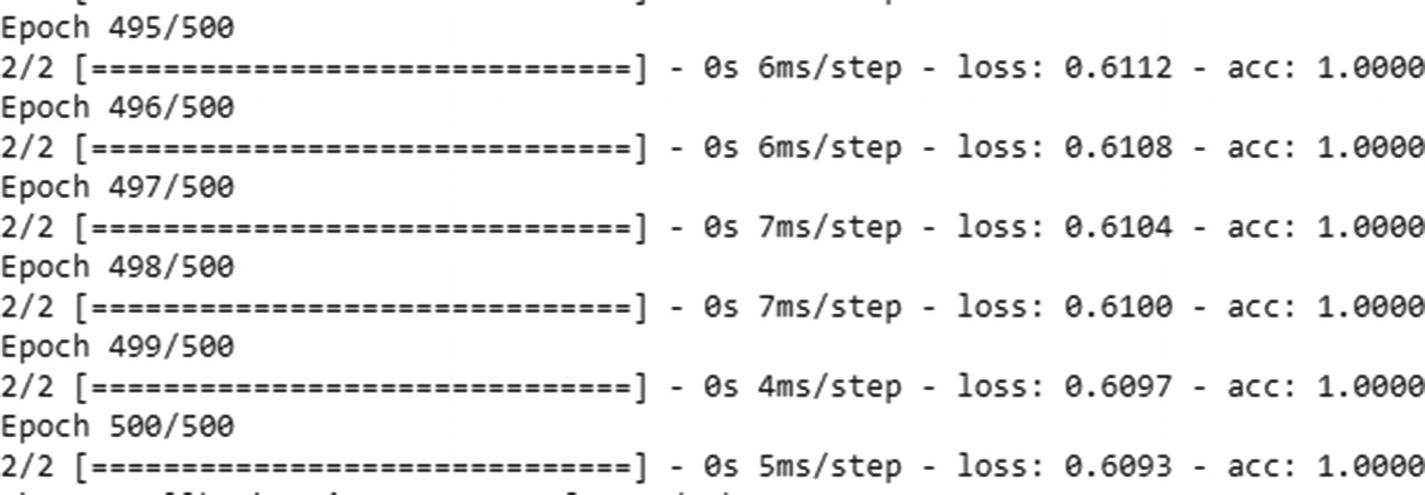

Once the model is compiled, let’s go ahead and fit the model , as follows:

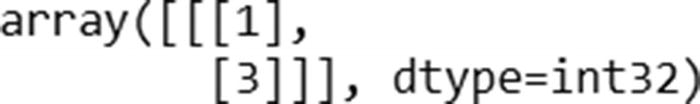

Note that we have reshaped padded_docs. That’s because we need to convert our training dataset into a format as follows while fitting: {data size, number of time steps, features per time step}. Also, labels should be in an array format, since the final dense layer in the compiled model expects an array.

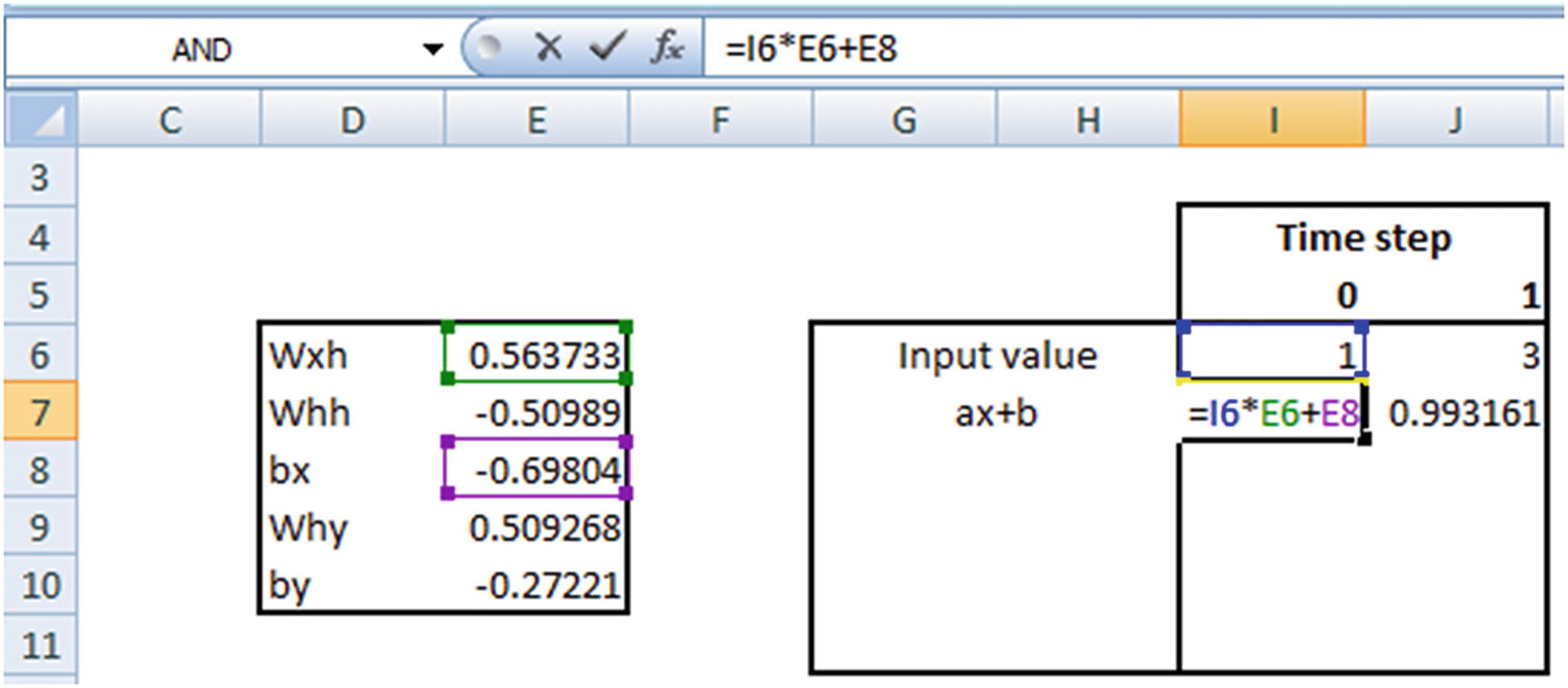

Verifying the Output of RNN

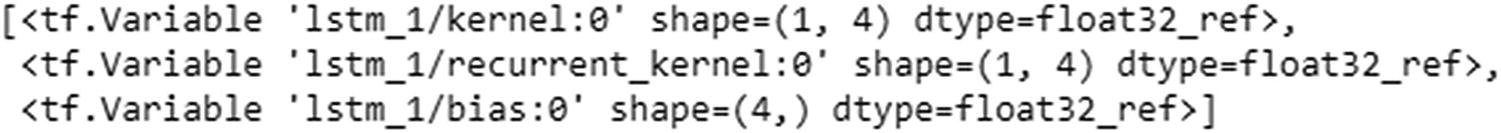

Now that we have fit our toy model, let’s verify the Excel calculations we created earlier. Note that we have taken the input to be the raw encodings {1,2,3}—in practice we would never take the raw encodings as they are, but would one-hot-encode or create embeddings for the input. We are taking the raw inputs as they are in this section only to compare the outputs from keras and the hand calculations we are going to do in Excel.

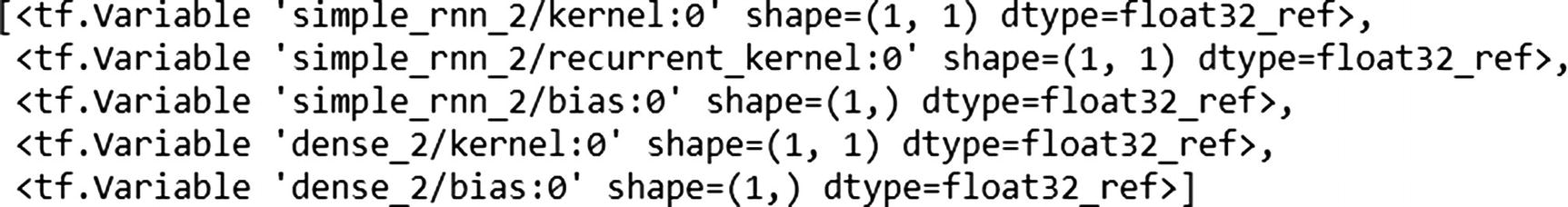

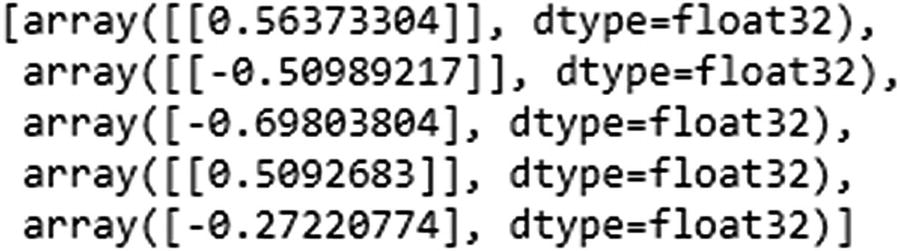

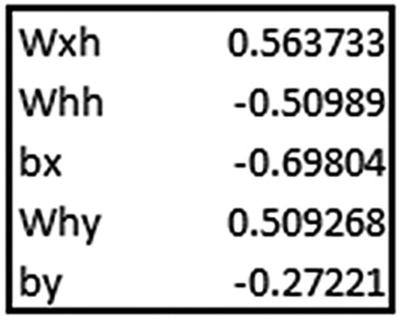

Note that the weights are ordered—that is, the first weight value corresponds to kernel:0. In other words, it is the same as wxh, which is the weight associated with the inputs.

recurrent_kernel:0 is the same as whh, which is the weight associated with the connection between the previous hidden layer earlier and the current time step’s hidden layer. bias:0 is the bias associated with the inputs. dense_2/kernel:0 is why—that is, the weight connecting the hidden layer to the output. dense_2/bias:0 is the bias associated with connection between the hidden layer and the output.

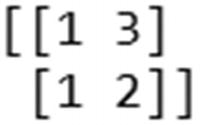

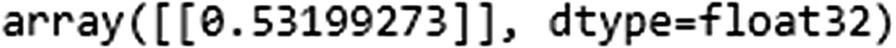

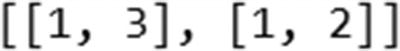

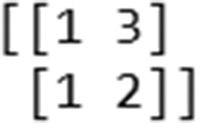

Let’s verify the prediction for the input [1,3]:

The hidden layer value in time step 1 is going to be the following:

tanh(Hidden layer value in time step 1 × Weight associated with hidden layer to hidden layer connection (whh) + Previous hidden layer value)

Implementing RNN: Text Generation

Now that we’ve seen how a typical RNN works, let’s look into how to generate text using APIs provided by keras for RNN (available as “RNN text generation.ipynb” in github).

- 1.

Import the packages:

from keras.models import Sequentialfrom keras.layers import Dense,Activationfrom keras.layers.recurrent import SimpleRNNimport numpy as np - 2.

Read the dataset:

fin=open('/home/akishore/alice.txt',encoding='utf-8-sig')lines=[]for line in fin:line = line.strip().lower()line = line.decode("ascii","ignore")if(len(line)==0):continuelines.append(line)fin.close()text = " ".join(lines) - 3.

Normalize the file to have only small case and remove punctuation, if any:

text[:100] # Remove punctuations in datasetimport retext = text.lower()text = re.sub('[^0-9a-zA-Z]+',' ',text)

# Remove punctuations in datasetimport retext = text.lower()text = re.sub('[^0-9a-zA-Z]+',' ',text) - 4.

One-hot-encode the words:

from collections import Countercounts = Counter()counts.update(text.split())words = sorted(counts, key=counts.get, reverse=True)chars = wordstotal_chars = len(set(chars))nb_chars = len(text.split())char2index = {word: i for i, word in enumerate(chars)}index2char = {i: word for i, word in enumerate(chars)} - 5.

Create the input and target datasets :

SEQLEN = 10STEP = 1input_chars = []label_chars = []text2=text.split()for i in range(0,nb_chars-SEQLEN,STEP):x=text2[i:(i+SEQLEN)]y=text2[i+SEQLEN]input_chars.append(x)label_chars.append(y)print(input_chars[0])print(label_chars[0])

- 6.

Encode the input and output datasets:

X = np.zeros((len(input_chars), SEQLEN, total_chars), dtype=np.bool)y = np.zeros((len(input_chars), total_chars), dtype=np.bool)# Create encoded vectors for the input and output valuesfor i, input_char in enumerate(input_chars):for j, ch in enumerate(input_char):X[i, j, char2index[ch]] = 1y[i,char2index[label_chars[i]]]=1print(X.shape)print(y.shape)

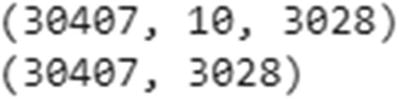

Note that, the shape of X indicates that we have a total 30,407 rows that have 10 words each, where each of the 10 words is expressed in a 3,028-dimensional space (since there are a total of 3,028 unique words).

- 7.

Build the model:

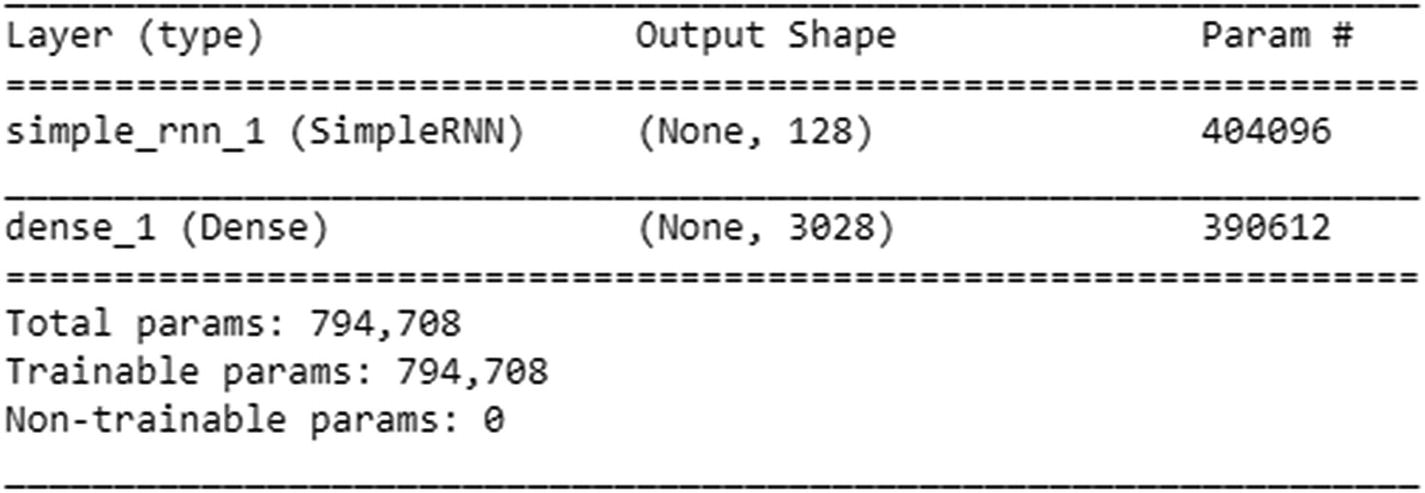

HIDDEN_SIZE = 128BATCH_SIZE = 128NUM_ITERATIONS = 100NUM_EPOCHS_PER_ITERATION = 1NUM_PREDS_PER_EPOCH = 100model = Sequential()model.add(SimpleRNN(HIDDEN_SIZE,return_sequences=False,input_shape=(SEQLEN,total_chars),unroll=True))model.add(Dense(nb_chars, activation="sigmoid"))model.compile(optimizer='rmsprop', loss="categorical_crossentropy")model.summary()

- 8.

Run the model, where we randomly generate a seed text and try to predict the next word given the set of seed words:

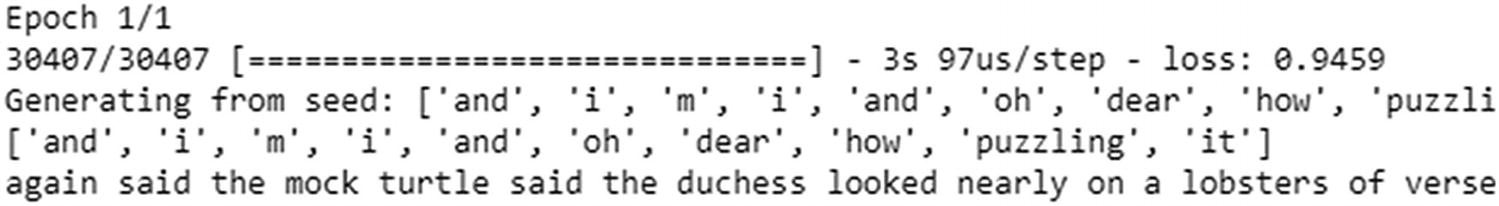

for iteration in range(150):print("=" * 50)print("Iteration #: %d" % (iteration))# Fitting the valuesmodel.fit(X, y, batch_size=BATCH_SIZE, epochs=NUM_EPOCHS_PER_ITERATION)# Time to see how our predictions fare# We are creating a test set from a random location in our dataset# In the code below, we are selecting a random input as our seed value of wordstest_idx = np.random.randint(len(input_chars))test_chars = input_chars[test_idx]print("Generating from seed: %s" % (test_chars))print(test_chars)# From the seed words, we are tasked to predict the next words# In the code below, we are predicting the next 100 words (NUM_PREDS_PER_EPOCH) after the seed wordsfor i in range(NUM_PREDS_PER_EPOCH):# Pre processing the input data, just like the way we did before training the modelXtest = np.zeros((1, SEQLEN, total_chars))for i, ch in enumerate(test_chars):Xtest[0, i, char2index[ch]] = 1# Predict the next wordpred = model.predict(Xtest, verbose=0)[0]# Given that, the predictions are probability values, we take the argmax to fetch the location of highest probability# Extract the word belonging to argmaxypred = index2char[np.argmax(pred)]print(ypred,end=' ')# move forward with test_chars + ypred so that we use the original 9 words + prediction for the next predictiontest_chars = test_chars[1:] + [ypred]

The output in the initial iterations is just the single word the—always!

The preceding output has very little loss. And if you look at the output carefully after you execute code, after some iterations it is reproducing the exact text that is present in the dataset—a potential overfitting issue. Also, notice the shape of our input: ~30K inputs, where there are 3,028 columns. Given the low ratio of rows to columns, there is a chance of overfitting. This is likely to work better as the number of input samples increases a lot more.

The issue of having a high number of columns can be overcome by using embedding, which is very similar to the way in which we calculated word vectors. Essentially, embeddings represent a word in a much lower dimensional space.

Embedding Layer in RNN

- 1.

As always, import the relevant packages :

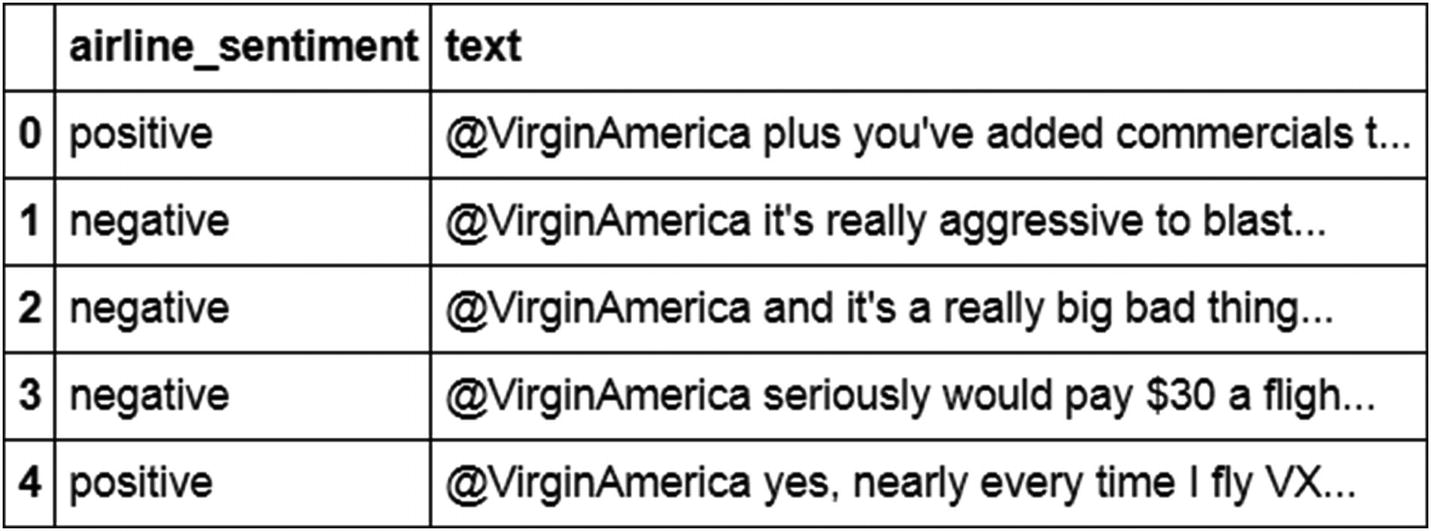

#import relevant packagesfrom keras.layers import Dense, Activationfrom keras.layers.recurrent import SimpleRNNfrom keras.models import Sequentialfrom keras.utils import to_categoricalfrom keras.layers.embeddings import Embeddingfrom sklearn.cross_validation import train_test_splitimport numpy as npimport nltkfrom nltk.corpus import stopwordsimport reimport pandas as pd#Let us go ahead and read the dataset:t=pd.read_csv('/home/akishore/airline_sentiment.csv')t.head() import numpy as npt['sentiment']=np.where(t['airline_sentiment']=="positive",1,0)

import numpy as npt['sentiment']=np.where(t['airline_sentiment']=="positive",1,0) - 2.

Given that the text is noisy, we will pre-process it by removing punctuation and also converting all words into lowercase :

def preprocess(text):text=text.lower()text=re.sub('[^0-9a-zA-Z]+',' ',text)words = text.split()#words2=[w for w in words if (w not in stop)]#words3=[ps.stem(w) for w in words]words4=' '.join(words)return(words4)t['text'] = t['text'].apply(preprocess) - 3.

Similar to how we developed in the previous section, we convert each word into an index value as follows:

from collections import Countercounts = Counter()for i,review in enumerate(t['text']):counts.update(review.split())words = sorted(counts, key=counts.get, reverse=True)words[:10] chars = wordsnb_chars = len(words)word_to_int = {word: i for i, word in enumerate(words, 1)}int_to_word = {i: word for i, word in enumerate(words, 1)}word_to_int['the']#3int_to_word[3]#the

chars = wordsnb_chars = len(words)word_to_int = {word: i for i, word in enumerate(words, 1)}int_to_word = {i: word for i, word in enumerate(words, 1)}word_to_int['the']#3int_to_word[3]#the - 4.

Map each word in a review to its corresponding index :

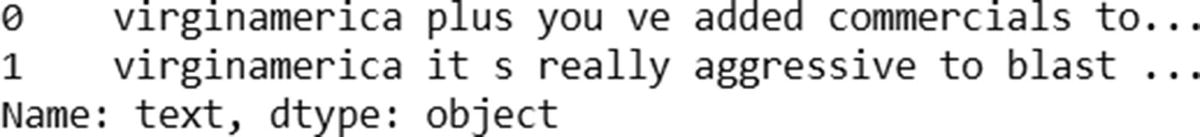

mapped_reviews = []for review in t['text']:mapped_reviews.append([word_to_int[word] for word in review.split()])t.loc[0:1]['text'] mapped_reviews[0:2]

mapped_reviews[0:2]

Note that, the index of virginamerica is the same in both reviews (104).

- 5.

Initialize a sequence of zeroes of length 200. Note that we have chosen 200 as the sequence length because no review has more than 200 words in it. Moreover, the second part of the following code makes sure that for all reviews that are less than 200 words in size, all the starting indices are zero padded and only the last indices are filled with index corresponding to the words present in the review:

sequence_length = 200sequences = np.zeros((len(mapped_reviews), sequence_length),dtype=int)for i, row in enumerate(mapped_reviews):review_arr = np.array(row)sequences[i, -len(row):] = review_arr[-sequence_length:] - 6.

We further split the dataset into train and test datasets , as follows:

y=t['sentiment'].valuesX_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(sequences, y, test_size=0.30,random_state=10)y_train2 = to_categorical(y_train)y_test2 = to_categorical(y_test) - 7.

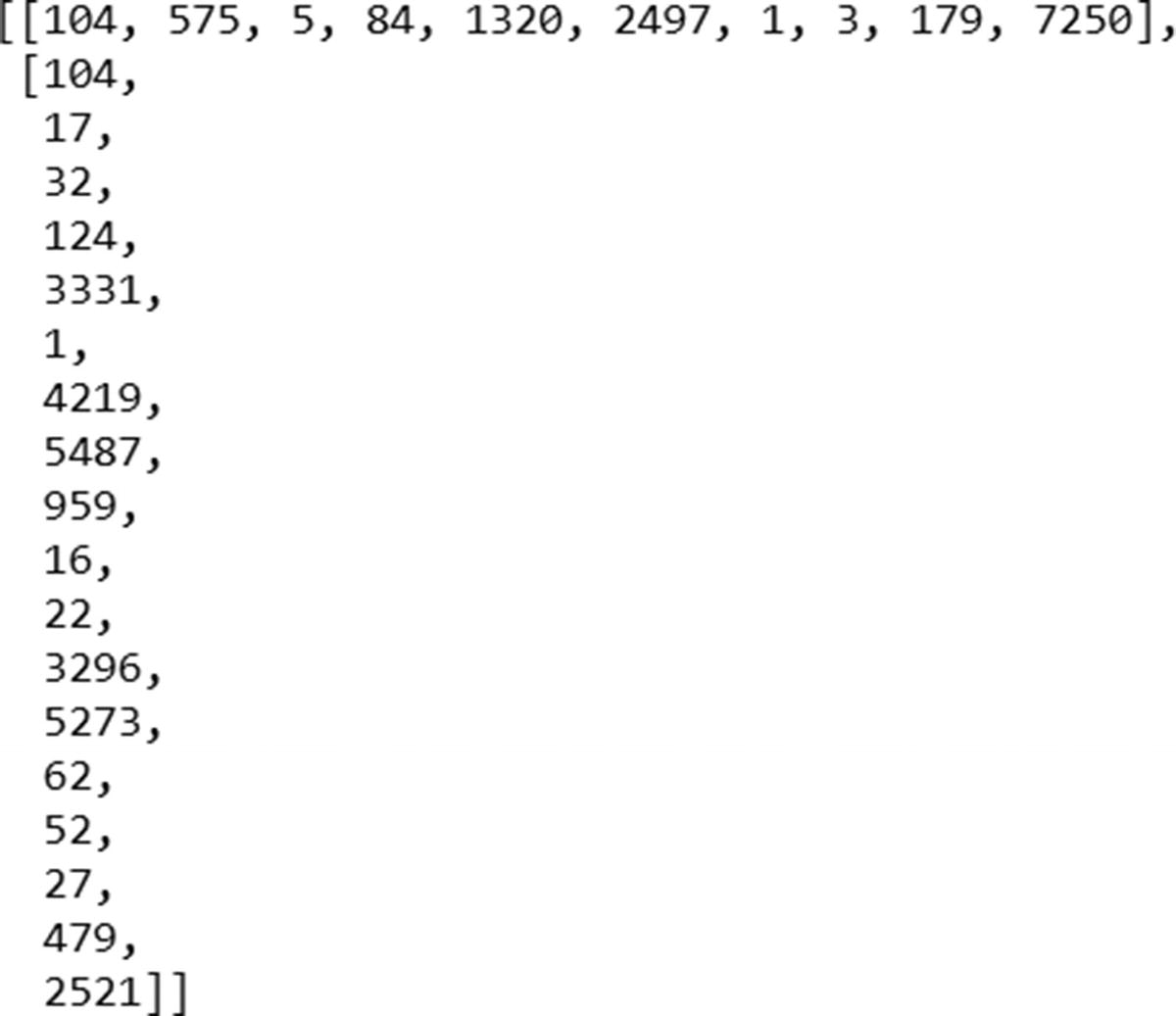

Once the datasets are in place, we go ahead and create our model, as follows. Note that embedding as a function takes in as input the total number of unique words, the reduced dimension in which we express a given word, and the number of words in an input:

top_words=12679embedding_vecor_length=32max_review_length=200model = Sequential()model.add(Embedding(top_words, embedding_vecor_length, input_length=max_review_length))model.add(SimpleRNN(1, return_sequences=False,unroll=True))model.add(Dense(2, activation="softmax"))model.compile(loss='categorical_crossentropy', optimizer="adam", metrics=['accuracy'])print(model.summary())model.fit(X_train, y_train2, validation_data=(X_test, y_test2), epochs=50, batch_size=1024)

Now let’s look at the summary output of the preceding model. There are a total of 12,679 unique words in the dataset. The embedding layer ensures that we represent each of the words in a 32-dimensional space, hence the 405,728 parameters in the embedding layer.

Now that we have 32 embedded dimensional inputs, each input is now connected to one hidden layer unit—thus 32 weights. Along, with the 32 weights, we would have a bias. The final weight corresponding to this layer would be the weight that connects the previous hidden to unit value to the current hidden unit. Thus a total of 34 weights.

Note that, given that there is an output coming from the embedding layer, we don’t need to specify the input shape in the SimpleRNN layer. Once the model has run, the output classification accuracy turns out to be close to 87%.

Issues with Traditional RNN

An RNN with multiple time steps

h1 = Wx1

h2 = Wx2 + Uh1 = Wx2 + UWx1

h3 = Wx3 + Uh2 = Wx3 + UWx2 + U2Wx1

h4 = Wx4 + Uh3 = Wx4 + UWX3 + U2WX2 + U3WX1

h5 = Wx5 + Uh4 = Wx5 + UWX4 + U2WX3 + U3WX2 + U4WX1

Note that as the time stamp increases, the value of the hidden layer is highly dependent on X1 if U > 1, and a little dependent on X1 if U < 1.

The Problem of Vanishing Gradient

The gradient of U4 with respect to U is 4 × U3. In such a case, note that if U < 1, the gradient is very small, so arriving at the ideal weights takes a very long time if the output at a much a later time step depends on the input at a given time step. This results in an issue when there is a dependency on a word that occurred much earlier in the time steps in some sentences. For example, “I am from India. I speak fluent ____.” In this case, if we did not take the first sentence into account, the output of the second sentence, “I speak fluent ____” could be the name of any language. Because we mentioned the country in the first sentence, we should be able to narrow things down to languages specific to India.

The Problem of Exploding Gradients

In the preceding scenario, if U > 1, then gradients increase by a much larger amount. This would result in having a very high weightage for inputs that occurred much earlier in the time steps and low weightage for inputs that occurred near the word that we are trying to predict.

Hence, depending on the value of U (weights of the hidden layer), the weights either get updated very quickly or take a very long time.

Given that vanishing/exploding gradient is an issue, we should deal with RNNs in a slightly different way.

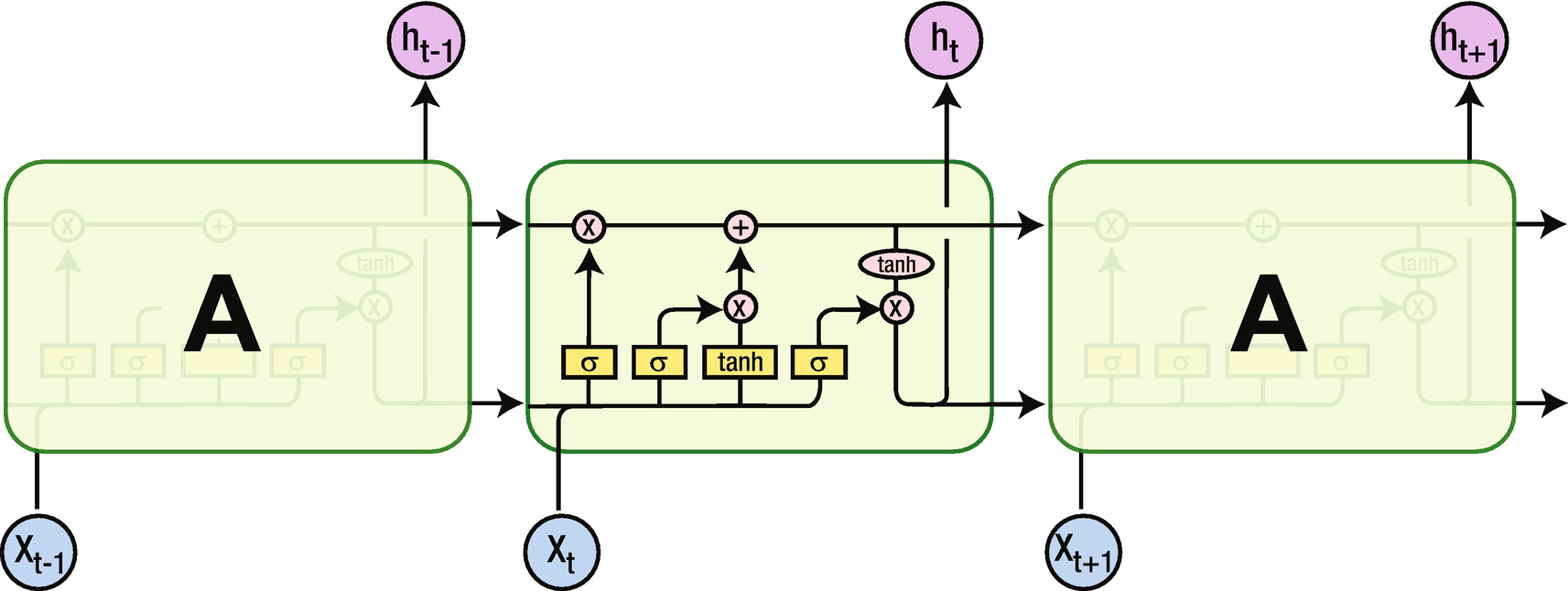

LSTM

Long short-term memory (LSTM) is an architecture that helps overcome the vanishing or exploding gradient problem we saw earlier. In this section, we will look at the architecture of LSTM and see how it helps in overcoming the issue with traditional RNN.

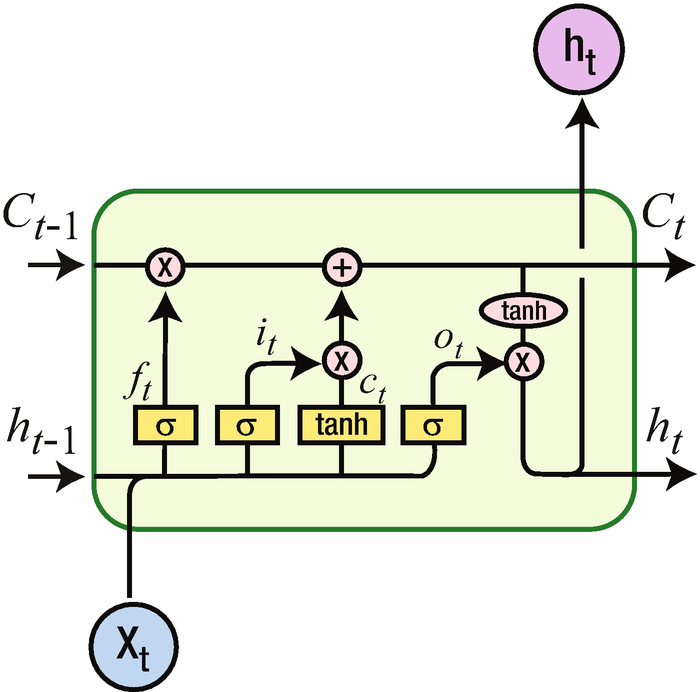

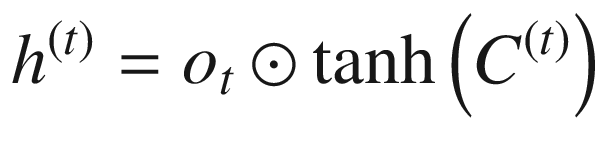

LSTM

Note that although the input X and the output of the hidden layer (h) remain the same, the activations that happen within the hidden layer are different. Unlike the traditional RNN, which has tanh activation, there are different activations that happen within LSTM. We’ll go through each of them.

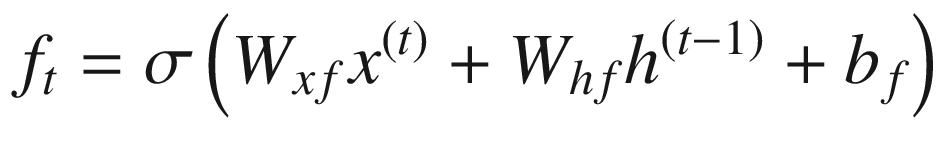

Various components of LSTM

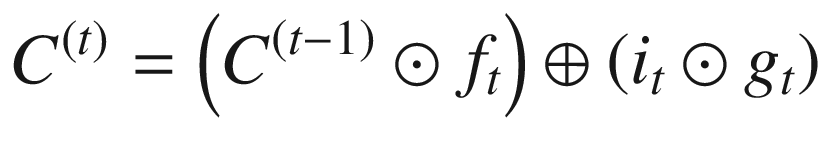

C represents the cell state. You can think of cell state as a way in which long-term dependencies are captured.

Note that the sigmoid gives us a mechanism to specify what needs to be forgotten. This way, some historical words that are captured in h(t–1) are selectively forgotten.

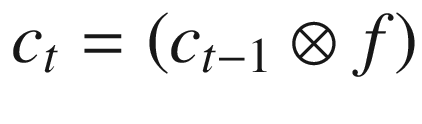

Note that  represents element-to-element multiplication.

represents element-to-element multiplication.

Consider that once we fill in the blank in “I live in India. I speak ____” with the name of an Indian language, we don’t need the context of “I live in India” anymore. This is where the forget gate helps in selectively forgetting the information that is not needed anymore.

Once we figure out what needs to be forgotten in the cell state, we can go ahead and update the cell state based on the current input.

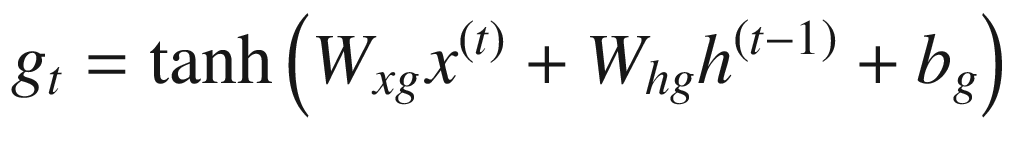

In the next step, the input that needs to update the cell state is achieved through the sigmoid application on top of input, and the magnitude of update (either positive or negative) is obtained through the tanh activation.

Given that the cell state can memorize the values that are needed at a later point in time, LSTM provides better results than traditional RNN in predicting the next word, typically in sentiment classification. This is especially useful in a scenario where there is a long-term dependency that needs to be taken care of.

Implementing Basic LSTM in keras

- 1.

Import the relevant packages :

from keras.preprocessing.text import one_hotfrom keras.preprocessing.sequence import pad_sequencesfrom keras.models import Sequentialfrom keras.layers import Densefrom keras.layers import Flattenfrom keras.layers.recurrent import SimpleRNNfrom keras.layers.embeddings import Embeddingfrom keras.layers import LSTMimport numpy as np - 2.

Define documents and labels :

# define documentsdocs = ['very good','very bad']# define class labelslabels = [1,0] - 3.

One-hot-encode the documents:

from collections import Countercounts = Counter()for i,review in enumerate(docs):counts.update(review.split())words = sorted(counts, key=counts.get, reverse=True)vocab_size=len(words)word_to_int = {word: i for i, word in enumerate(words, 1)}encoded_docs = []for doc in docs:encoded_docs.append([word_to_int[word] for word in doc.split()])encoded_docs

- 4.

Pad documents to a maximum length of two words :

max_length = 2padded_docs = pad_sequences(encoded_docs, maxlen=max_length, padding="pre")print(padded_docs)

- 5.

Build the model :

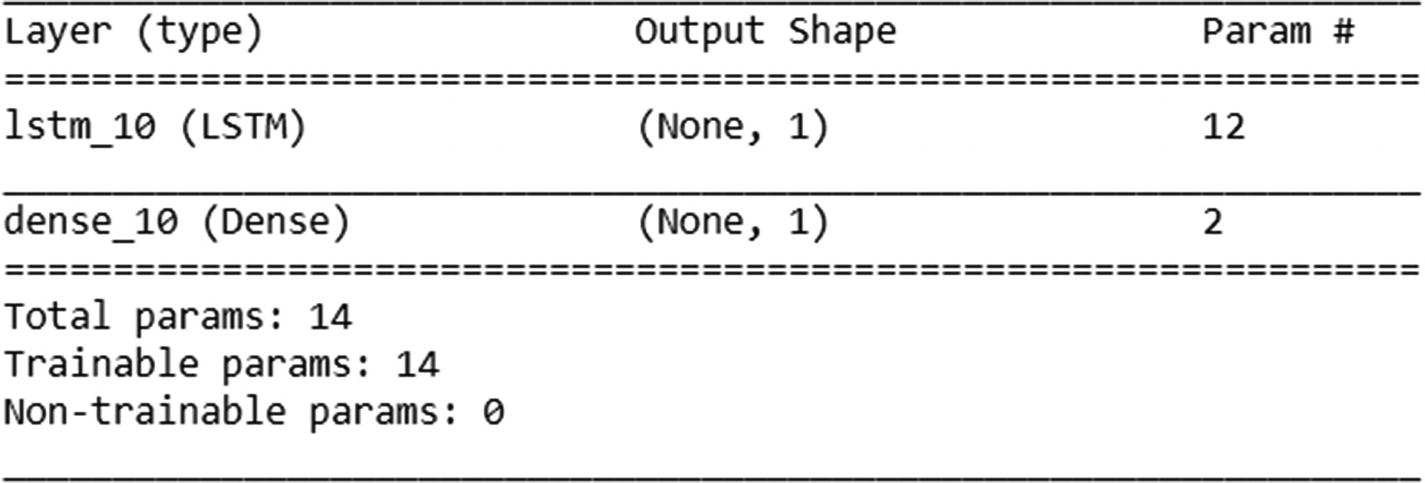

model = Sequential()model.add(LSTM(1,activation='tanh', return_sequences=False,recurrent_initializer='Zeros',recurrent_activation='sigmoid',input_shape=(2,1),unroll=True))model.add(Dense(1, activation="sigmoid"))model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss="binary_crossentropy", metrics=['acc'])print(model.summary())

Note that in the preceding code , we have initialized the recurrent initializer and recurrent activation to certain values only to make this toy example easier to understand when implemented in Excel. The purpose is to help you understand what is happening in the back end only.

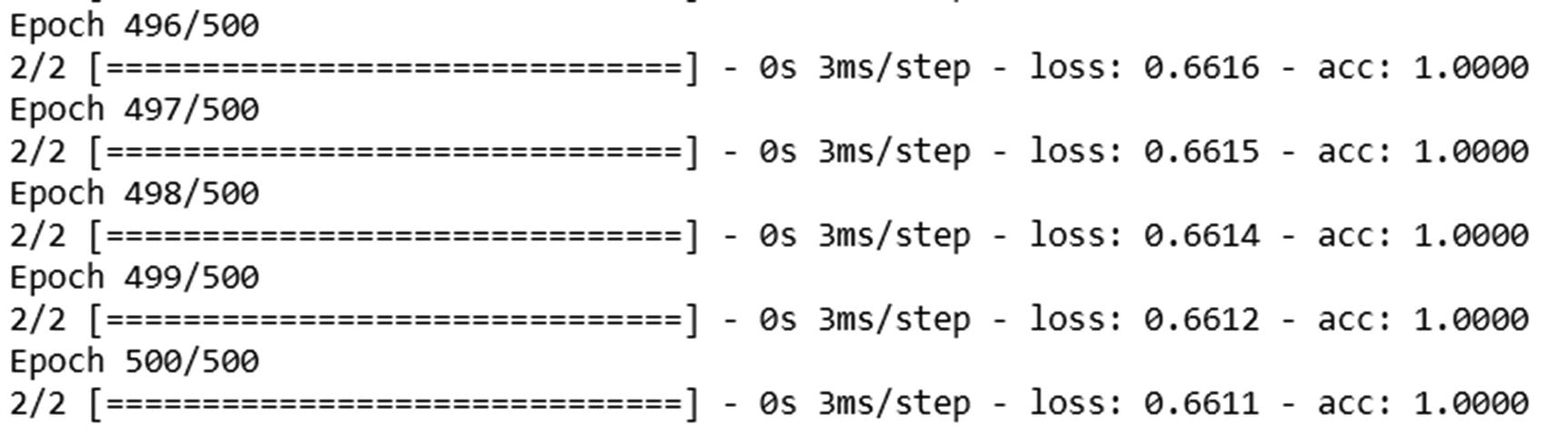

Once the model is initialized as discussed, let’s go ahead and fit the model:

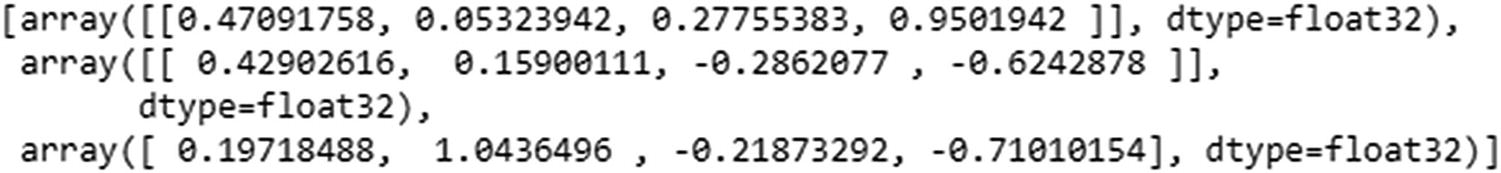

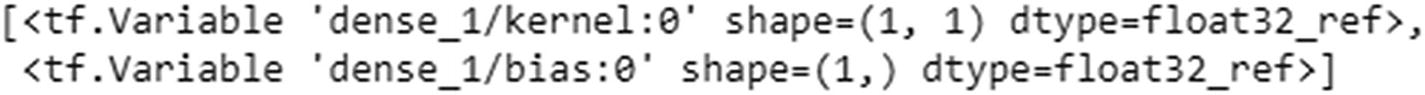

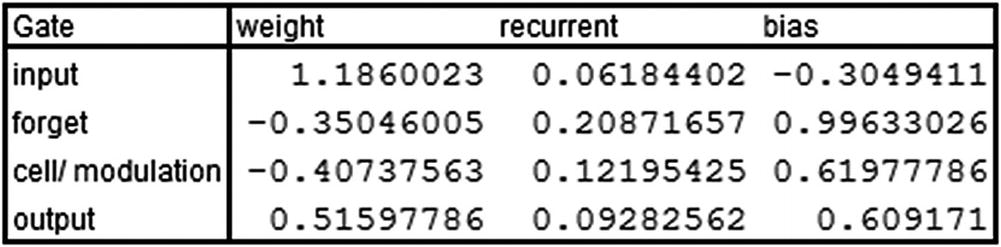

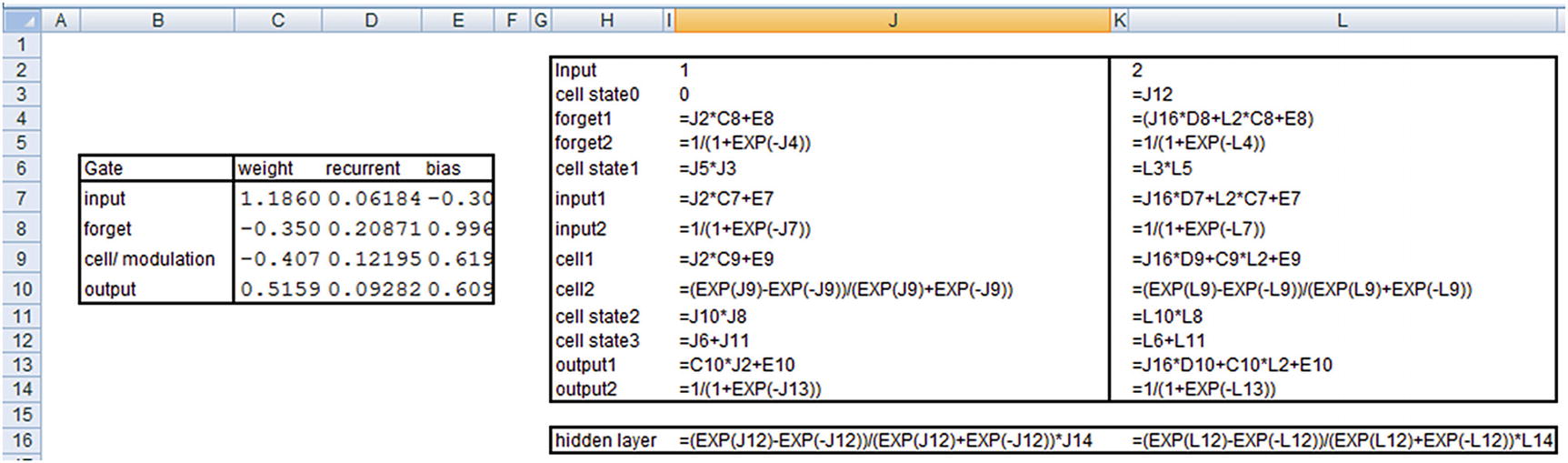

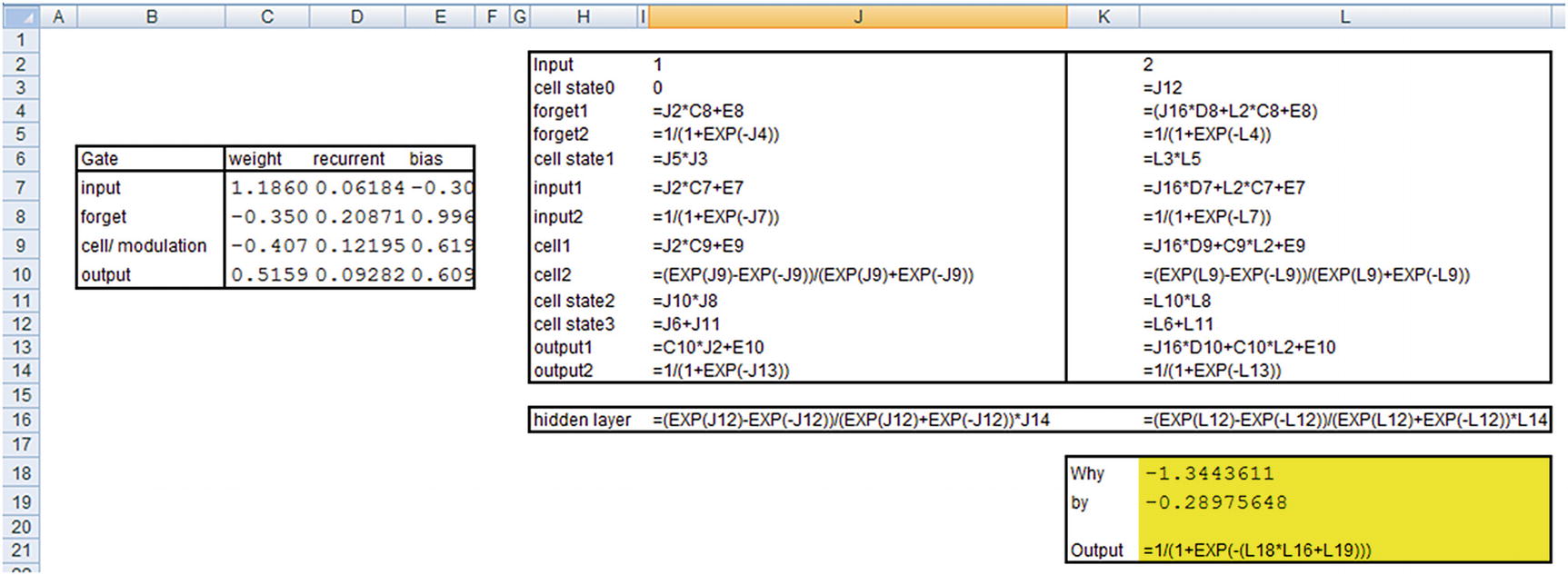

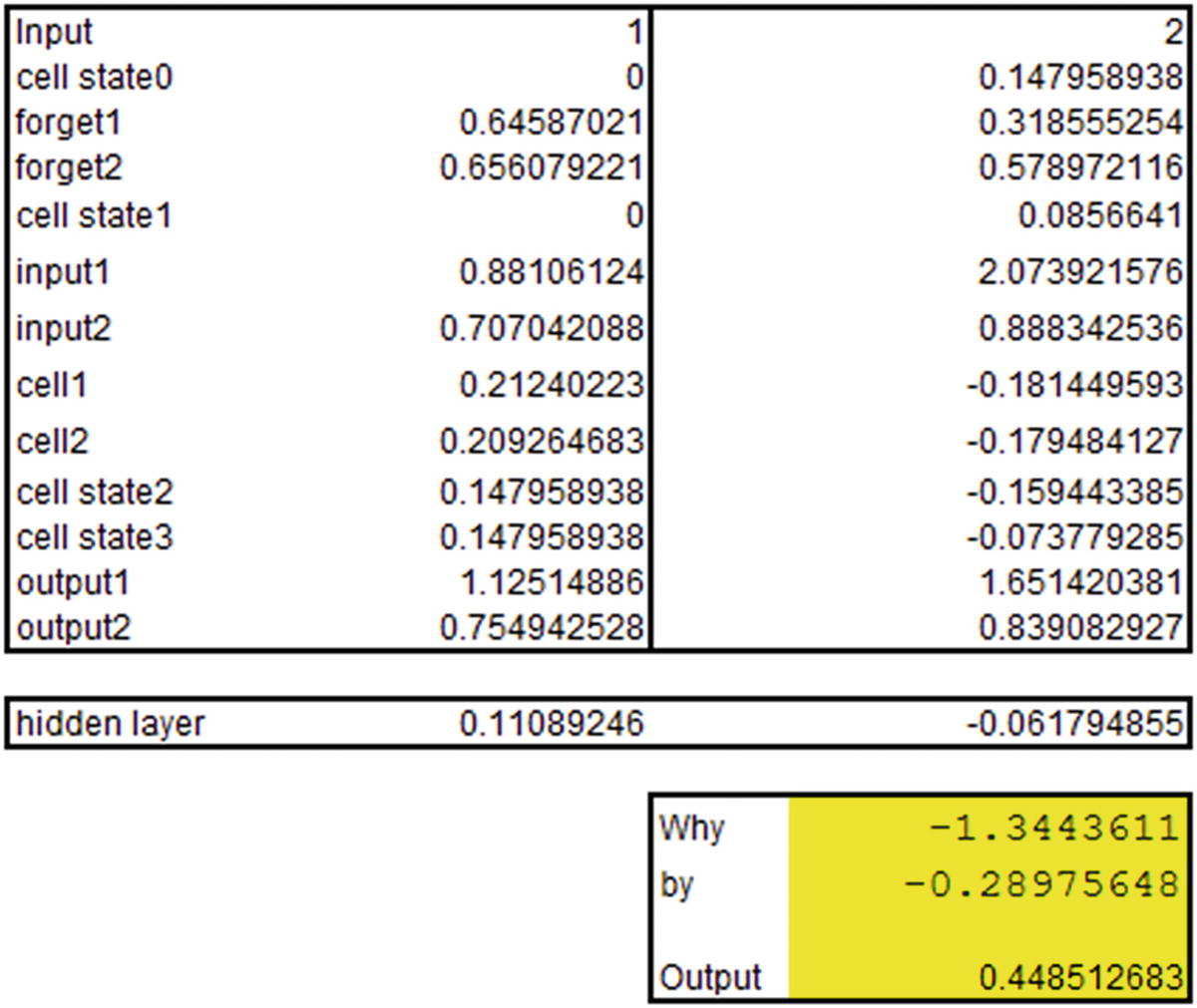

From the preceding code , we can see that weights of input (kernel) are obtained first, followed by weights corresponding to the hidden layer (recurrent_kernel) and finally the bias in the LSTM layer.

Similarly, in the dense layer (the layer connecting the hidden layer to output), the weight to be multiplied with the hidden layer comes first, followed by the bias.

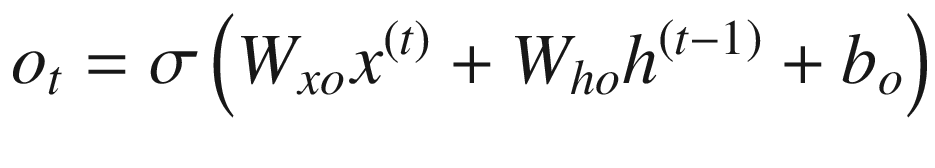

- 1.

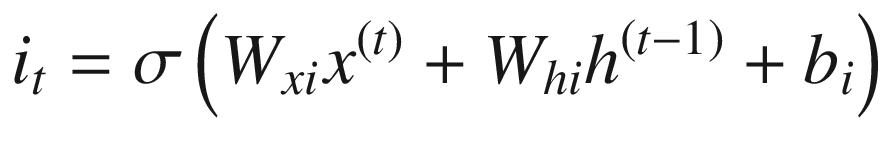

Input gate

- 2.

Forget gate

- 3.

Modulation gate (cell gate)

- 4.

Output gate

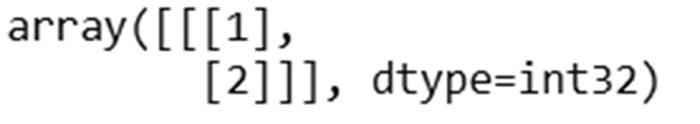

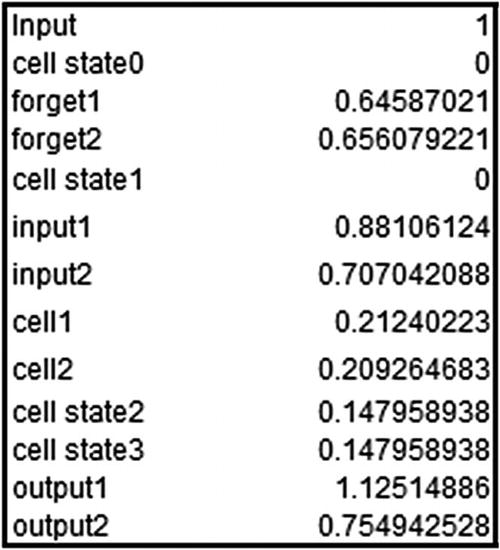

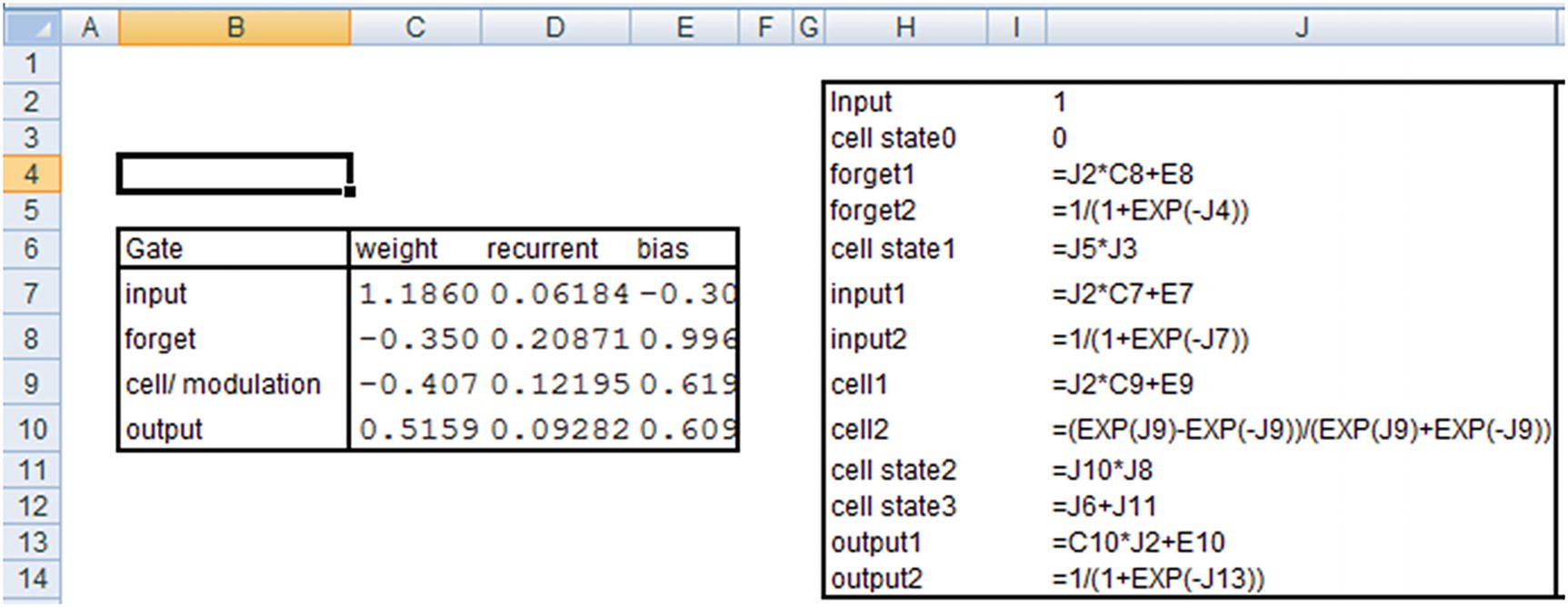

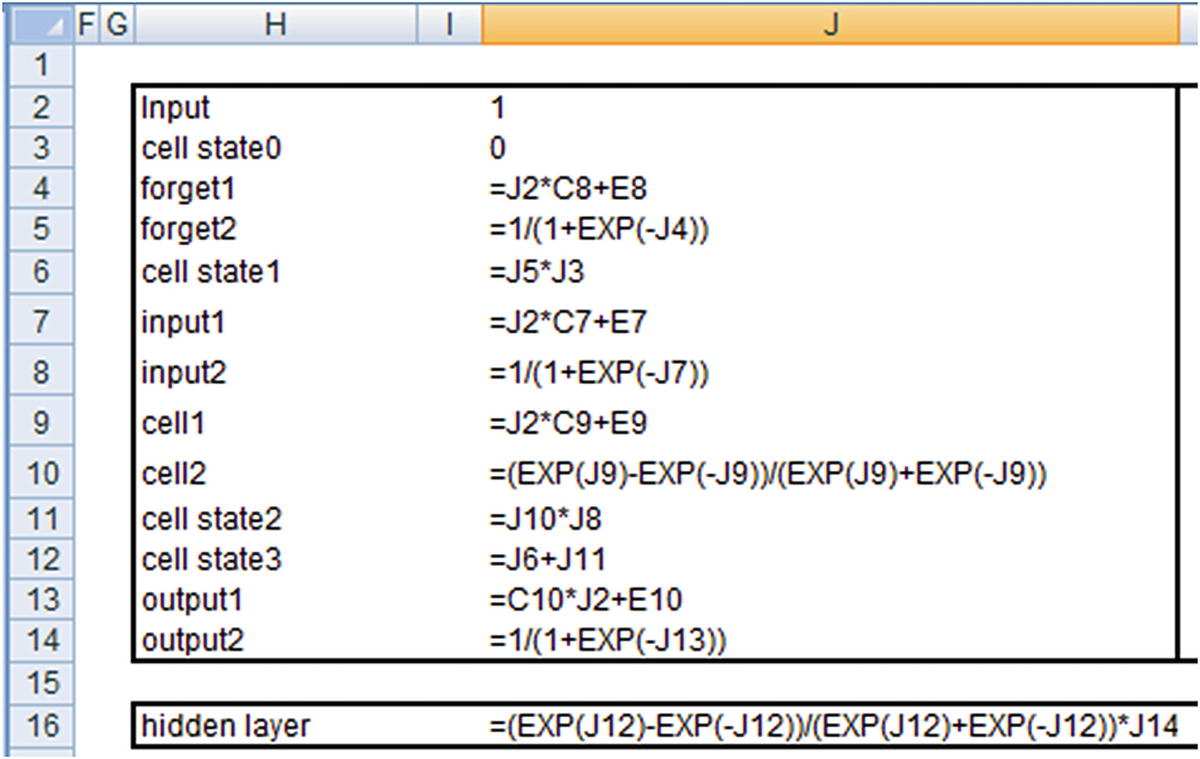

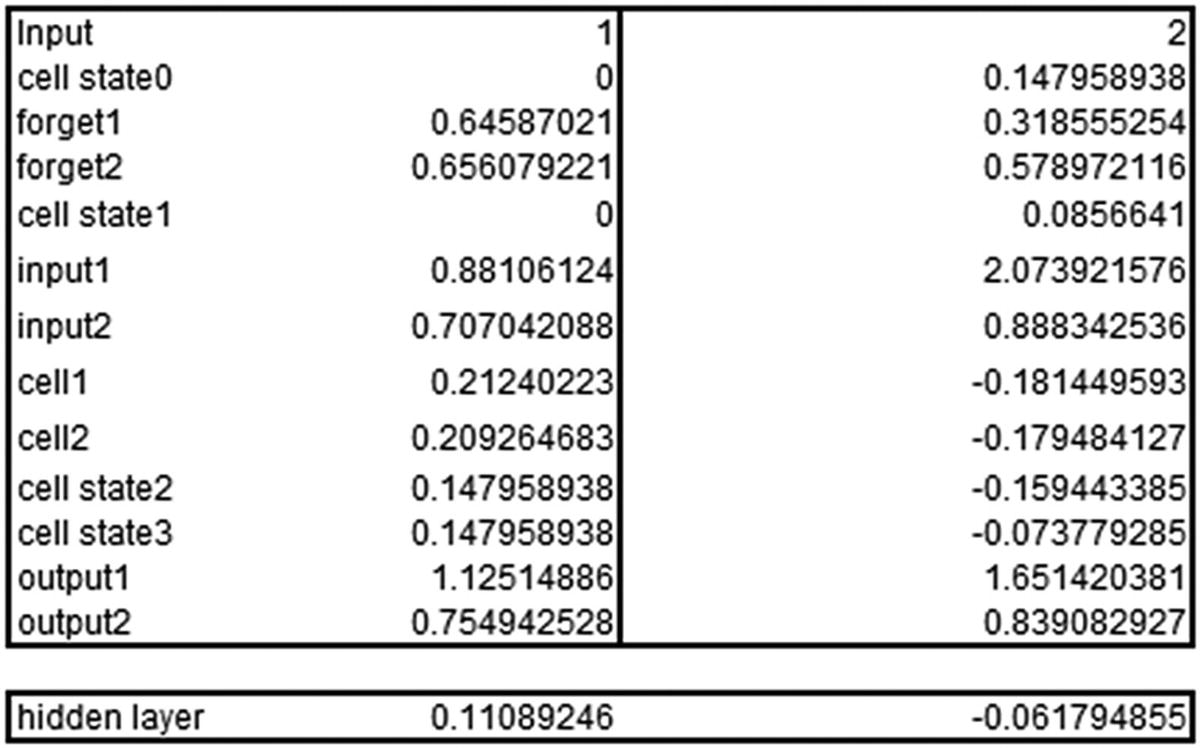

Now that we have our outputs, let’s go ahead and calculate the predictions for input. Note that just like in the previous section, we are using raw encoded inputs (1,2,3) without further processing them—only to see how the calculation works.

In practice, we would be further processing the inputs, potentially encoding them into vectors to obtain the predictions, but in this example we are interested in solidifying our knowledge of how LSTM works by replicating the predictions from LSTM in Excel :

Note that the values here are taken from keras’s model.layers[0].get_weights() output.

The hidden layer value just shown is the hidden layer output at the time step where the input is 1.

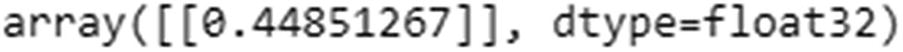

Note that the output that we’ve derived is the same as what we see in the keras output .

Implementing LSTM for Sentiment Classification

In the last section, we implemented sentiment classification using RNN in keras. In this section, we will look at implementing the same using LSTM. The only change in the code we saw above will be the model compiling part, where we will be using LSTM in place of SimpleRNN—everything else will remain the same (code is available in “RNN sentiment.ipynb” file in github):

Once you implement the model, you should see that the prediction accuracy of LSTM is slightly better than that of RNN. In practice, for the dataset we looked earlier, LSTM gives an accuracy of 91%, whereas RNN gave an accuracy of 87%. This can be further fine-tuned by adjusting various hyper-parameters that are provided by the functions.

Implementing RNN in R

To look at how to implement RNN/LSTM in R, we will use the IMDB sentiment classification dataset that comes pre-built along with the kerasR package (code available as “kerasR_code_RNN.r” in github):

Note that we are fetching only the top 500 words by specifying num_words as a parameter. We are also fetching only those IMDB reviews that have a length of at most 100 words.

Let’s explore the structure of the dataset:

We should notice that in the pre-built IMDB dataset that came along with the kerasR package, each word is replaced by the index it represents by default. So we do not have to perform the step of word-to-index mapping:

The preceding results in close to 79% accuracy on the test dataset prediction .

Summary

RNNs are extremely helpful in dealing with data that has time dependency.

RNNs face issues with vanishing or exploding gradient when dealing with long-term dependency in data.

LSTM and other recent architectures come in handy in such a scenario.

LSTM works by storing the information in cell state, forgetting the information that does not help anymore, selecting the information as well as the amount of information that need to be added to cell state based on current input, and finally, the information that needs to be outputted to the next state.