Segmenting a program into manageable chunks of code is fundamental to programming in every language. A function is a basic building block in C++ programs. So far, every example has had one function, main(), and has typically used functions from the Standard Library. This chapter is all about defining your own functions with names that you choose.

What a function is and why you should segment your programs into functions

How to declare and define functions

How data is passed to a function and how a function can return a value

What the difference is between “pass-by-value” and “pass-by-reference” and how to choose between both mechanisms

What the best way is to pass strings to a function

How to specify default values for function parameters

What the preferred way is to return a function’s output in modern C++

How to handle optional input parameters and optional return values

How using const as a qualifier for a parameter type affects the operation of a function

The effect of defining a variable as static within a function

What an inline function is

How to create multiple functions that have the same name but different parameters—a mechanism you’ll come to know as function overloading

What recursion is and how to apply it to implement elegant algorithms

Segmenting Your Programs

All the programs you have written so far have consisted of just one function, main() . A real-world C++ application consists of many functions, each of which provides a distinct well-defined capability. Execution starts in main(), which must be defined in the global namespace. main() calls other functions, each of which may call other functions, and so on. The functions other than main() can be defined in a namespace that you create.

When one function calls another that calls another that calls another, you have a situation where several functions are in action concurrently. Each that has called another that has not yet returned will be waiting for the function that was called to end. Obviously something must keep track of from where in memory each function call was made and where execution should continue when a function returns. This information is recorded and maintained automatically in the stack. We introduced the stack when we explained free store memory, and the stack is often referred to as the call stack in this context. The call stack records all the outstanding function calls and details of the data that was passed to each function. The debugging facilities that come with most C++ development systems usually provide ways for you to view the call stack while your program executes.

Functions in Classes

A class defines a new type, and each class definition will usually contain functions that represent the operations that can be carried out with objects of the class type. You have already used functions that belong to a class extensively. In the previous chapter, you used functions that belong to the string class, such as the length() function, which returns the number of characters in the string object, and the find() function for searching a string. The standard input and output streams cin and cout are objects, and using the stream insertion and extraction operators calls functions for those objects. Functions that belong to classes are fundamental in object-oriented programming, which you’ll learn about from Chapter 11 onward.

Characteristics of a Function

A function should perform a single, well-defined action and should be relatively short. Most functions do not involve many lines of code, certainly not hundreds of lines. This applies to all functions, including those that are defined within a class. Several of the working examples you saw earlier could easily be divided into functions. If you look again at Ex7_05.cpp, for instance, you can see that what the program does falls naturally into three distinct actions. First the text is read from the input stream, then the words are extracted from the text, and finally the words that were extracted are output. Thus, the program could be defined as three functions that perform these actions, plus the main() function that calls them.

Defining Functions

The return type, which is the type of value, if any, that the function returns when it finishes execution. A function can return data of any type, including fundamental types, class types, pointer types, or reference types. It can also return nothing, in which case you specify the return type as void.

The name of the function. Functions are named according to the same rules as variables.

The number and types of data items that can be passed to the function when it is called. This is called the parameter list, and it appears as a comma-separated list between parentheses following the function name.

A general representation of a function looks like this:

An example of a function definition

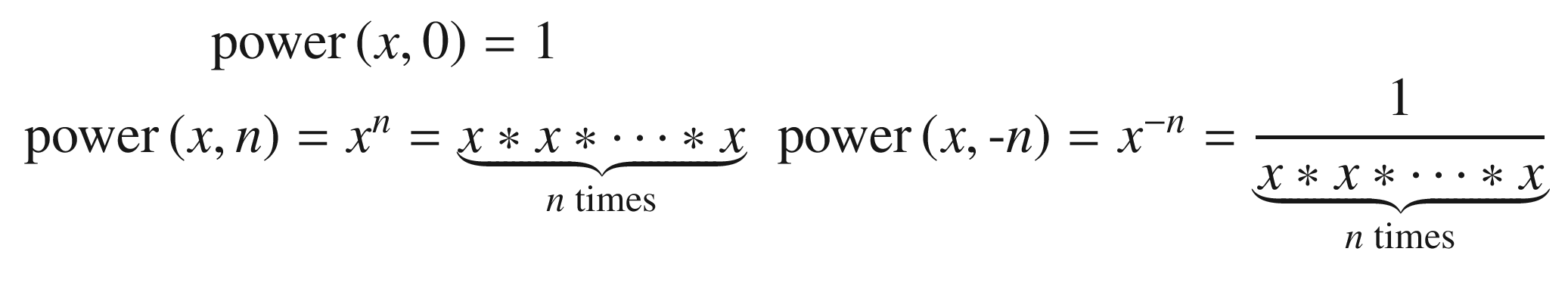

If nothing is to be passed to a function when it is called, then nothing appears between the parentheses. If there is more than one item in the parameter list, they are separated by commas. The power() function in Figure 8-1 has two parameters, x and n. The parameter names are used in the body of the function to access the corresponding values that were passed to the function. Our power function could be called from elsewhere in the program as follows:

When this call to power() is evaluated, the code in the function body gets executed with the parameters x and n initialized to 3.0 and 2, respectively, with 3.0 being the value of the number variable. The term argument is used for the values that are passed to a function when called. So in our example, number and 2 are arguments, and x and n are the corresponding parameters. The sequence of arguments in a function call must correspond to the sequence of the parameters in the parameter list of the function definition. More specifically, their types should match. If they do not match exactly, the compiler will apply implicit conversions whenever possible. Here’s an example:

Even though the type of the first argument passed here is float, this code snippet will still compile; the compiler implicitly converts the argument to the type of its corresponding parameter. If no implicit conversion is possible, compilation will, of course, fail.

The conversion from float to double is lossless since a double generally has twice as many bits available to represent the number—and hence the name double. So, this conversion is always safe. The compiler will happily perform the opposite conversion for you as well, though. That is, it will implicitly convert a double argument when assigned to a float parameter. This is a so-called narrowing conversion; because a double can represent numbers with much greater precision than a float, information may be lost during this conversion. Most compilers will issue a warning when it performs such narrowing conversions.

The combination of the function name and the parameter list is called the signature of a function. The compiler uses the signature to decide which function is to be called in any particular instance. Thus, functions that have the same name must have parameter lists that differ in some way to allow them to be distinguished. As we will discuss in detail later, such functions are called overloaded functions.

Tip

While it made for compact code that fitted nicely in Figure 8-1, from a coding style point of view the parameter names x and n used by our definition of power() do not particularly excel in clarity. One could perhaps argue that x and n are still acceptable in this specific case because power() is a well-known mathematical function and x and n are commonplace in mathematical formulae. That notwithstanding, in general we highly recommend you use more descriptive parameter names. Instead of x and n, for instance, you should probably use base and exponent, respectively. In fact, you should always choose descriptive names for just about everything: function names, variable names, class names, and so on. Doing so consistently will go a long way toward keeping your code easy to read and understand.

Our power() function returned a value of type double. Not every function, though, has to return a value—it might just write something to a file or a database or modify some global state. The void keyword is used to specify that a function does not return a value as follows:

Note

A function with a return type specified as void doesn’t return a value, so it can’t be used in most expressions. Attempting to use such a function in this way will cause a compiler error message.

The Function Body

Calling a function executes the statements in the function body with the parameters having the values you pass as arguments. Returning to our definition of power() in Figure 8-1, the first line of the function body defines the double variable, result, initialized with 1.0. result is an automatic variable so only exists within the body of the function. This means that result ceases to exist after the function finishes executing.

The calculation is performed in one of two for loops, depending on the value of n. If n is greater than or equal to zero, the first for loop executes. If n is zero, the body of the loop doesn’t execute at all because the loop condition is immediately false. In this case, result is left at 1.0. Otherwise, the loop variable i assumes successive values from 1 to n, and result is multiplied by x on each iteration. If n is negative, the second for loop executes, which divides result by x on each loop iteration.

The variables that you define within the body of a function and all the parameters are local to the function. You can use the same names in other functions for quite different purposes. The scope of each variable you define within a function is from the point at which it is defined until the end of the block that contains it. The only exceptions to this rule are variables that you define as static, and we’ll discuss these later in the chapter.

Let’s give the power() function a whirl in a complete program.

This program produces the following output:

All the action occurs in the for loop in main(). The power() function is called seven times. The first argument is 8.0 on each occasion, but the second argument has successive values of i, from –3 to +3. Thus, seven values are outputs that correspond to 8-3, 8-2, 8-1, 80, 81, 82, and 83.

Tip

While it is instructive to write your own power() function, there is of course already one provided by the Standard Library. The cmath header offers a variety of std::pow(base, exponent) functions similar to our version, except that they are designed to work optimally with all numeric parameter types—that is, not just with double and int but also, for instance, with float and long, with long double and unsigned short, or even with noninteger exponents. You should always prefer the predefined mathematical functions of the cmath header; they will almost certainly be far more efficient and accurate than anything you could write yourself.

Return Values

A function with a return type other than void must return a value of the type specified in the function header. The only exception to this rule is the main() function, where, as you know, reaching the closing brace is equivalent to returning 0. Normally, though, the return value is calculated within the body of the function and is returned by a return statement, which ends the function, and execution continues from the calling point. There can be several return statements in the body of a function with each potentially returning a different value. The fact that a function can return only a single value might appear to be a limitation, but this isn’t the case. The single value that is returned can be anything you like: an array, a container such as std::vector<>, or even a container with elements that are containers.

How the return Statement Works

The return statement in the previous program returns the value of result to the point where the function was called. The result variable is local to the function and ceases to exist when the function finishes executing, so how is it returned? The answer is that a copy of the double being returned is made automatically, and this copy is made available to the calling function. The general form of the return statement is as follows:

expression must evaluate to a value of the type that is specified for the return value in the function header or must be convertible to that type. The expression can be anything, as long as it produces a value of an appropriate type. It can include function calls and can even include a call of the function in which it appears, as you’ll see later in this chapter.

If the return type is specified as void, no expression can appear in a return statement. It must be written simply as follows:

If the last statement in a function body executes so that the closing brace is reached, this is equivalent to executing a return statement with no expression. In a function with a return type other than void, this is an error, and the function will not compile—except for main(), of course.

Function Declarations

Ex8_01.cpp works perfectly well as written, but let’s try rearranging the code so that the definition of main() precedes the definition of the power() function in the source file. The code in the program file will look like this:

As you’ll see later, a program can consist of several source files. The definition of a function that is called in one source file may be contained in a separate source file.

Suppose you have a function A() that calls a function B(), which in turn calls A(). If you put the definition of A() first, it won’t compile because it calls B(); the same problem arises if you define B() first because it calls A().

Naturally, there is a solution to these difficulties. You can declare a function before you use or define it by means of a function prototype.

Note

Functions that are defined in terms of each other, such as the A() and B() functions we described just now, are called mutually recursive functions. We’ll talk more about recursion near the end of this chapter.

Function Prototypes

A function prototype is a statement that describes a function sufficiently for the compiler to be able to compile calls to it. It defines the function name, its return type, and its parameter list. A function prototype is sometimes referred to as a function declaration. A function can be compiled only if the call is preceded by a function declaration in the source file. The definition of a function also doubles as a declaration, which is why you didn’t need a function prototype for power() in Ex8_01.cpp.

You could write the function prototype for the power() function as follows:

If you place function prototypes at the beginning of a source file, the compiler is able to compile the code regardless of where the function definitions are. Ex8_02.cpp will compile if you insert the prototype for the power() function before the definition of main().

The function prototype shown earlier is identical to the function header with a semicolon appended. A function prototype is always terminated by a semicolon, but in general, it doesn’t have to be identical to the function header. You can use different names for the parameters from those used in the function definition (but not different types, of course). Here’s an example:

This works just as well. The compiler only needs to know the type each parameter is, so you can omit the parameter names from the prototype, like this:

There is no particular merit in writing function prototypes like this. It is much less informative than the version with parameter names. If both function parameters were of the same type, then a prototype like this would not give any clue as to which parameter was which. We recommend that you always include descriptive parameter names in function prototypes.

It could be a good idea to always write prototypes for each function that is defined in a source file—with the exception of main(), of course, which never requires a prototype. Specifying prototypes near the start of the file removes the possibility of compiler errors arising from functions not being sequenced appropriately. It also allows other programmers to get an overview of the functionality of your code.

Most of the examples in the book use functions from the Standard Library, so where are the prototypes for them? The standard headers contain them. A primary use of header files is to collect the function prototypes for a related group of functions.

Passing Arguments to a Function

It is important to understand precisely how arguments are passed to a function. This affects how you write functions and ultimately how they operate. There are also a number of pitfalls to be avoided. In general, the function arguments should correspond in type and sequence to the list of parameters in the function definition. You have no latitude so far as the sequence is concerned, but you do have some flexibility in the argument types. If you specify a function argument of a type that doesn’t correspond to the parameter type, then the compiler inserts an implicit conversion of the argument to the type of the parameter where possible. The rules for automatic conversions of this kind are the same as those for automatic conversions in an assignment statement. If an automatic conversion is not possible, you’ll get an error message from the compiler. If such implicit conversions result in potential loss of precision, compilers generally issue a warning. Examples of such narrowing conversions are conversions from long to int, double to float, or int to float (see also Chapter 2).

There are two mechanisms by which arguments are passed to functions, pass-by-value and pass-by-reference. We’ll explain the pass-by-value mechanism first.

Pass-by-Value

The pass-by-value mechanism for arguments to a function

Each time you call the power() function, the compiler arranges for copies of the arguments to be stored in a temporary location in the call stack. During execution, all references to the function parameters in the code are mapped to these temporary copies of the arguments. When execution of the function ends, the copies of the arguments are discarded.

We can demonstrate the effects of this with a simple example. The following calls a function that attempts to modify one of its arguments, and of course, it fails miserably:

This example produces the following output:

The output shows that adding 10 to it in the changeIt() function has no effect on the variable it in main(). The it variable in changeIt() is local to the function, and it refers to a copy of whatever argument value is passed when the function is called. Of course, when the value of it that is local to changeIt() is returned, a copy of its current value is made, and it’s this copy that’s returned to the calling program.

Pass-by-value is the default mechanism by which arguments are passed to a function. It provides a lot of security to the calling function by preventing the function from modifying variables that are owned by the calling function. However, sometimes you do want to modify values in the calling function. Is there a way to do it when you need to? Sure there is; one way is to use a pointer.

Passing a Pointer to a Function

When a function parameter is a pointer type, the pass-by-value mechanism operates just as before. However, a pointer contains the address of another variable; a copy of the pointer contains the same address and therefore points to the same variable.

If you modify the definition of the first changeIt() function to accept an argument of type double*, you can pass the address of it as the argument. Of course, you must also change the code in the body of changeIt() to dereference the pointer parameter. The code is now like this:

This version of the program produces the following output:

Passing a pointer to a function

This version of changeIt() serves only to illustrate how a pointer parameter can allow a variable in the calling function to be modified—it is not a model of how a function should be written. Because you are modifying the value of it directly, returning its value is somewhat superfluous.

Passing an Array to a Function

An array name is essentially an address, so you can pass the address of an array to a function just by using its name. The address of the array is copied and passed to the function. This provides several advantages:

First, passing the address of an array is an efficient way of passing an array to a function. Passing all the array elements by value would be time-consuming because every element would be copied. In fact, you can’t pass all the elements in an array by value as a single argument because each parameter represents a single item of data.

Second, and more significantly, because the function does not deal with the original array variable but with a copy, the code in the body of the function can treat a parameter that represents an array as a pointer in the fullest sense, including modifying the address that it contains. This means you can use the power of pointer notation in the body of a function for parameters that are arrays. Before we get to that, let’s try the most straightforward case first—handling an array parameter using array notation.

This example includes a function to compute the average of the elements in an array:

This produces the following brief output:

The average() function works with an array containing any number of double elements. As you can see from the prototype, it accepts two arguments: the array address and a count of the number of elements. The type of the first parameter is specified as an array of any number of values of type double. You can pass any one-dimensional array of elements of type double as an argument to this function, so the second parameter that specifies the number of elements is essential. The function will rely on the correct value for the count parameter being supplied by the caller. There’s no way to verify that it is correct, so the function will quite happily access memory locations outside the array if the value of count is greater than the array length. With this definition, it is up to the caller to ensure that this doesn’t happen.

And in case you were wondering, no, you cannot circumvent the need for the count parameter by using either the sizeof operator or std::size() inside the average() function. Remember, an array parameter such as array simply stores the address of the array, not the array itself. So, the expression sizeof(array) would return the size of the memory location that contains the address of the array and not the size of the entire array. A call of std::size() with an array parameter name will simply not compile because std::size() has no way of determining the array’s size either. Without the definition of the array, the compiler has no way to determine its size. It cannot do so from only the array’s address.

Within the body of average(), the computation is expressed in the way you would expect. There’s no difference between this and the way you would write the same computation directly in main(). The average() function is called in main() in the output statement. The first argument is the array name, values, and the second argument is an expression that evaluates to the number of array elements.

The elements of the array that is passed to average() are accessed using normal array notation. We’ve said that you can also treat an array passed to a function as a pointer and use pointer notation to access the elements. Here’s how average() would look in that case:

For all intents and purposes, both notations are completely equivalent. In fact, as you saw in Chapter 5, you can freely mix both notations. You can, for instance, use array notation with a pointer parameter:

There really is no difference at all in the way any of these function definitions are evaluated. In fact, the following two function prototypes are considered identical by the compiler:

We will revisit this later in the section on function overloading.

Caution

There exists a common and potentially dangerous misconception about passing fixed-size arrays to functions. Consider the following variant of the average() function:

Clearly, the author of this function wrote it to average exactly ten values; no more, no less. We invite you to replace average() in Ex8_05.cpp with the previous average10() function and update the function call in main() accordingly. The resulting program should compile and run just fine. So, what’s the problem? The problem is that the signature of this function—which unfortunately is perfectly legal C++ syntax—creates the false expectation that the compiler would enforce that only arrays of size exactly 10 can be passed as arguments to this function. To verify, let’s see what happens if we change the body of the main() function of our example program to pass only three values (you can find the resulting program in Ex8_05A.cpp):

Even though we now called average10() with an array that is considerably shorter than the required ten values, the resulting program should still compile. If you run it, the average10() function will blindly read well beyond the bounds of the values array. Obviously, no good can come of this. Either the program will crash or it will produce garbage output. The root of the problem is that, unfortunately, the C++ language dictates that a compiler is supposed to treat a function signature of the form

yet again as synonymous with either one of the following:

Because of this, you should never use a dimension specification when passing an array by value; it only creates false expectations. An array that is passed by value is always passed as a pointer, and its dimensions are not checked by the compiler. We will see later that you can safely pass given-size arrays to a function using pass-by-reference instead of pass-by-value.

const Pointer Parameters

The average() function only needs to access values of the array elements; it doesn’t need to change them. It would be a good idea to make sure that the code in the function does not inadvertently modify elements of the array. Specifying the parameter type as const will do that:

Now the compiler will verify that the elements of the array are not modified in the body of the function. So if you now, for instance, accidentally type (*array)++ instead of *array++, compilation will fail. Of course, you must modify the function prototype to reflect the new type for the first parameter; remember that pointer-to-const types are quite different from pointer-to-non-const types.

Specifying a pointer parameter as const has two consequences: the compiler checks the code in the body of the function to ensure that you don’t try to change the value pointed to, and it allows the function to be called with an argument that points to a constant.

Note

In our latest definition of average(), we didn’t declare the function’s count parameter const as well. If a parameter of a fundamental type such as int or size_t is passed by value, it does not need to be declared const, at least not for the same reason. The pass-by-value mechanism makes a copy of the argument when the function is called, so you are already protected from modifying the original value from within the function.

Nonetheless, it does remain good practice to mark variables as const if they will or should not change during a function’s execution. This general guideline applies to any variable—including those declared in the parameter list. For that reason, and for that reason only, you might still consider declaring count as const. This would, for instance, prevent you from accidentally writing ++count somewhere in the function’s body, which could have disastrous results indeed. But know that you would then be marking a local copy as a constant and that it is by no means required to add const to prevent changes to the original value.

Passing a Multidimensional Array to a Function

Passing a multidimensional array to a function is quite straightforward. Suppose you have a two-dimensional array defined as follows:

The prototype of a hypothetical yield() function would look like this:

In theory, you could specify the first array dimension in the type specification for the first parameter as well, but it is best not to. The compiler would again simply ignore this, analogous to what happened for the average10() function we discussed earlier. The size of the second array dimension does have the desired effect, though—C++ is fickle that way. Any two-dimensional array with 4 as a second dimension can be passed to this function, but arrays with 3 or 5 as a second dimension cannot.

Let’s try passing a two-dimensional array to a function in a concrete example:

This produces the following output:

The first parameter to the yield() function is defined as a const array of an arbitrary number of rows of four elements of type double. When you call the function, the first argument is the beans array , and the second argument is the total length of the array in bytes divided by the length of the first row. This evaluates to the number of rows in the array.

Pointer notation doesn’t apply particularly well with a multidimensional array. In pointer notation, the statement in the nested for loop would be as follows:

Surely, you’ll agree that the computation is clearer in array notation!

Note

The definition of yield in Ex8_06 contains a “magic number” 4 in the inner for loop. In Chapter 5 we warned you that such numbers are mostly a bad idea. After all, if at some point the row length in the function signature is changed, it would be easy to also forget to update the number 4 in the for loop. A first solution would to replace the hard-coded number 4 with std::size(array[i]); another is to replace the inner loop with a range-based for loop:

Note that you cannot replace the outer loop with a range-based loop as well, and you cannot use std::size() there. Remember, there is no way for the compiler to know the first dimension of the double[][4] array; only the second dimension or higher of an array can be fixed when passing it by value.

Pass-by-Reference

As you may recall, a reference is an alias for another variable. You can specify a function parameter as a reference as well, in which case the function uses the pass-by-reference mechanism with the argument. When the function is called, an argument corresponding to a reference parameter is not copied. Instead, the reference parameter is initialized with the argument. Thus, it becomes an alias for the argument in the calling function. Wherever the parameter name is used in the body of the function, it is as if it accesses the argument value in the calling function directly.

You specify a reference type by adding & after the type name. To specify a parameter type as “reference to string,” for example, you write the type as string& . Calling a function that has a reference parameter is no different from calling a function where the argument is passed by value. Using references, however, improves performance with objects such as type string. The pass-by-value mechanism copies the object, which would be time-consuming with a long string and memory-consuming as well for that matter. With a reference parameter, there is no copying.

References vs. Pointers

In many regards, references are similar to pointers. To see the similarity, let’s use a variation of Ex8_04 with two functions: one that accepts a pointer as an argument and one that accepts a reference instead:

The result is that the original it value in main() is updated twice, once per function call:

The most obvious difference is that to pass a pointer, you need to take the address of a value first using the address-of operator. Inside the function you then, of course, have to dereference that pointer again to access the value. For a function that accepts its arguments by reference, you have to do neither. But note that this difference is purely syntactical; in the end, both have the same effect. In fact, compilers will mostly compile references in the same way as pointers.

So, which mechanism should you use, as they appear to be functionally equivalent? That’s a fair question. Let’s therefore consider some of the facets that play a role in this decision.

The single most distinctive feature of a pointer is that it can be nullptr , whereas a reference must always refer to something. So if you want to allow the possibility of a null argument, you cannot use a reference. Of course, precisely because a pointer parameter can be null, you’re almost forced to always test for nullptr before using it. References have the advantage that you do not need to worry about nullptrs.

As Ex8_07 shows, the syntax for calling a function with a reference parameter is indeed no different from calling a function where the argument is passed by value. On the one hand, because you do not need the address-of and dereferencing operators, reference parameters allow for a more elegant syntax. On the other hand, however, precisely the fact that there is no syntactical difference means that references can sometimes cause surprises. And code that surprises is bad code because surprises lead to bugs. Consider, for instance, the following function call:

Without a prototype or the definition of do_it(), you have no way of knowing whether the argument to this function is passed either by reference or by value. So, you also have no way of knowing whether the previous statement will modify the it value—provided it itself is not const, of course. This property of pass-by-reference can sometimes make code harder to follow, which may lead to surprises if values passed as arguments are changed when you did not expect them to be. Therefore:

Tip

Always declare variables as const whenever their values are not supposed to change anymore after initialization. This will make your code more predictable and hence easier to read and less prone to subtle bugs. Moreover, and perhaps even more importantly, in your function signatures, always declare pointer or reference parameters with const as well if the function does not modify the corresponding arguments. First, this makes it easier for programmers to use your functions because they can easily understand what will or will not be modified by a function just by looking at its signature. Second, reference-to-const parameters allow your functions to be called with const values. As we will show in the next section, const values—which as you now know should be used as much as possible—cannot be assigned to a reference-to-non-const parameter.

If you want to allow nullptr arguments, you cannot use references. Conversely, pass-by-reference can be seen as a contract that a value is not allowed to be null. Note already that instead of representing optional values as a nullable pointer, you may also want to consider the use of std::optional<>. We’ll discuss this option later in this chapter.

Using reference parameters allows for a more elegant syntax but may mask that a function is changing a value. Never change an argument value if it is not clear from the context—from the function name, for instance—that this will happen.

Because of the potential risks, some coding guidelines advise to never use reference-to-non-const parameters and advocate to instead always use pointer-to-non-const parameters. Personally, we would not go that far. There is nothing inherently wrong with a reference-to-non-const, as long as it is predictable for the caller which arguments may become modified. Choosing descriptive function and parameter names is always a good start to make a function’s behavior more predictable.

Passing arguments by reference-to-const is generally preferred over passing a pointer-to-const value. Because this is such a common case, we’ll present you with a bigger example in the next subsection.

Input vs. Output Parameters

In the previous section, you saw that a reference parameter enables the function to modify the argument within the calling function. However, calling a function that has a reference parameter is syntactically indistinguishable from calling a function where the argument is passed by value. This makes it particularly important to use a reference-to-const parameter in a function that does not change the argument. Because the function won’t change a reference-to-const parameter, the compiler will allow both const and non-const arguments. But only non-const arguments can be supplied for a reference-to-non-const parameter.

Let’s investigate the effect of using reference parameters in a new version of Ex7_06.cpp that extracts words from text:

The output is the same as Ex7_06.cpp. Here’s a sample:

There are now two functions in addition to main(): find_words() and list_words(). Note how the code in both functions is the same as the code that was in main() in Ex7_05.cpp. Dividing the program into three functions makes it easier to understand and does not increase the number of lines of code significantly.

The find_words() function finds all the words in the string identified by the second argument and stores them in the vector specified by the first argument. The third parameter is a string object containing the word separator characters.

The first parameter of find_words() is a reference, which avoids copying the vector<string> object. More important, though, it is a reference to a non-const vector<>, which allows us to add values to the vector from inside the function. Such a parameter is therefore sometimes called an output parameter because it is used to collect a function’s output. Parameters whose values are purely used as input are then called input parameters.

Tip

In principle, a parameter can act as both an input and an output parameter. Such a parameter is called an input-output parameter. A function with such a parameter, in one way or another, first reads from this parameter, uses this input to produce some output, and then stores the result into the same parameter. It is generally better to avoid input-output parameters, though, even if that means adding an extra parameter to your function. Code tends to be much easier to follow if each parameter serves a single purpose—a parameter should be either input or output, not both.

The find_words() function does not modify the values passed to the second and third parameters. Both are, in other words, input parameters and should therefore never be passed by reference-to-non-const. Reference-to-non-const parameters should be reserved for those cases where you need to modify the original value—in other words, for output parameters. For input parameters, only two main contenders remain: pass-by-reference-to-const or pass-by-value. And because string objects would otherwise be copied, the only logical conclusion is to declare both input parameters as const string&.

In fact, if you’d declare the third parameter to find_words() as a reference to a non-const string, the code wouldn’t even compile. Give it a try if you will. The reason is that the third argument in the function call in main(), separators, is a const string object. You cannot pass a const object as the argument for a reference-to-non-const parameter. That is, you can pass a non-const argument to a reference-to-const parameter but never the other way around. In short, a T value can be passed to both T& and const T& references, whereas a const T value can be passed only to a const T& reference. And this is only logical. If you have a value that you’re allowed to modify, there’s no harm in passing it to a function that will not modify it—not modifying something that you’re allowed to modify is fine. The converse is not true: if you have a const value, you’d better not be allowed to pass it to a function that might modify it!

The parameter for list_words(), finally, is reference-to-const because it too is an input parameter. The function only accesses the argument; it doesn’t change it.

Tip

Input parameters should usually be references-to-const. Only smaller values, most notably those of fundamental types, are to be passed by value. Use reference-to-non-const only for output parameters, and even then you should often consider returning a value instead. We’ll study how to return values from functions soon.

Passing Arrays by Reference

At first sight, it may seem that for arrays there would be little benefit from passing them by reference. After all, if you pass an array by value, the array elements themselves already do not get copied. Instead, a copy is made of the pointer to the first element of the array. Passing an array also already allows you to modify the values of the original array—unless you add const, of course. So surely this already covers both advantages typically attributed to passing by reference: no copying and the possibility to modify the original value?

While this is most certainly true, you did already discover the main limitation with passing an array by value earlier, namely, that there is no way to specify the array’s first dimension in a function signature, at least not in such a way that the compiler enforces that only arrays of exactly that size are passed to the function. A lesser-known fact, though, is that you can accomplish this by passing arrays by reference.

To illustrate, we invite you to again replace the average() function in Ex8_05.cpp with an average10() function, but this time with the following variant:

As you can see, the syntax for passing an array by reference is somewhat more complex. The const could in principle be omitted from the parameter type, but it is preferred here because you do not modify the values of the array in the function’s body. The extra parentheses surrounding &array are required, though. Without them, the compiler would no longer interpret the parameter type as a reference to an array of doubles but as an array of references to double. Because arrays of references are not allowed in C++, this would then result in a compiler error:

With our new and improved version of average10() in place, the compiler does live up to expectations. Attempting to pass any array of a different length should now result, as desired, in a compiler error:

Note, moreover, that if you pass a fixed-size array by reference, it can be used as input to operations such as sizeof(), std::size(), and range-based for loops. This was not possible with arrays that are passed by value. You can use this to eliminate the two occurrences of 10 from the body of average10():

Tip

You have already seen a more modern alternative to working with arrays of fixed length in Chapter 5: std::array<>. Using values of this type, you can just as safely pass fixed-size arrays by reference and without having to remember the tricky syntax for passing plain fixed-size arrays by reference:

We made three variants of this program available to you: Ex8_09A, which uses pass-by-reference; Ex8_09B, which eliminates the magic numbers; and Ex8_09C, to show the use of std::array<>.

References and Implicit Conversions

A program often uses many different types, and as you know, the compiler is usually quite happy to assist you by implicitly converting between them. Whether or not you should always be happy about such conversions is another matter, though. That aside, most of the time it is convenient that code such as the following snippet will compile just fine, even though it assigns an int value to a differently typed double variable:

For function arguments that employ pass-by-value, it is only natural that such conversions occur as well. For instance, given the same two variables i and d, a function with signature f(double) can hence be called not only with f(d) or f(1.23) but also with differently typed arguments such as f(i), f(123), or f(1.23f).

Implicit conversions thus remain quite straightforward for pass-by-value. Let’s take a look now how they fare with reference arguments:

We first define two trivial functions: one that doubles doubles and one that streams them to std::cout. The first part of main() then shows that these, of course, work for a double variable—obviously, you should thus see the number 246 appear in the output. The interesting parts of this example are its final two statements, of which the first is commented out because it would not compile.

Let’s consider the print_it(i) statement first and explain why it is in fact already a minor miracle that this even works at all. The function print_it() operates on a reference to a const double, a reference that as you know is supposed to act as an alias for a double that is defined elsewhere. On a typical system, print_it() will ultimately read the 8 bytes found in the memory location behind this reference and print out the 64 bits it finds there in some human-readable format to std::cout. But the value that we passed to the function as an argument is no double; it is an int! This int is generally only 4 bytes big, and its 32 bits are laid out completely differently than those of a double. So, how can this function be reading from an alias for a double if there is no such double defined anywhere in the program? The answer is that the compiler, before it calls print_it(), implicitly creates a temporary double value somewhere in memory, assigns it the converted int value, and then passes a reference to this temporary memory location to print_it().

Such implicit conversions are only supported for reference-to-const parameters, not for reference-to-non-const parameters. Suppose for argument’s sake that the double_it(i) statement on the second-to-last line will compile without error. Surely, the compiler will then similarly convert the int value 456 to a double value 456.0, store this temporary double somewhere in memory, and apply the function body of double_it() to it. Then you’d have a temporary double somewhere, now with value 912.0, and an int value i that is still equal to 456. Now, while in theory the compiler could convert the resulting temporary value back to an int, the designers of the C++ programming language decided that that would be a bridge too far. The reason is that generally such inverse conversions would inevitably mean loss of information. In our case, this would involve a conversion from double to int, which would result in the loss of at least the fractional part of the number. The creation of temporaries is therefore never allowed for reference-to-non-const parameters. This is also why the statement double_it(i) is invalid in standard C++ and should fail to compile.

String Views: The New Reference-to-const-string

As we explained earlier, the main motivation for passing input arguments by reference-to-const instead of by value is to avoid unnecessary copies. Copying bigger strings too often, for instance, can become quite expensive, in terms of both time and memory. This is why for functions that do not modify the std::strings they operate on, your natural instinct by now should be to declare the corresponding input parameters as const string&. We did this, for example, in Ex8_08 for find_words().

Unfortunately, const string& parameters are not perfect. While they do avoid copies of std::string objects, they have some shortcomings. To illustrate why, suppose that we alter the main() function of Ex8_08 a bit as follows:

The difference is that we no longer first store the separators in a separate separators constant of type const std::string. Instead, the corresponding string literal is passed directly as the third argument to the call of find_words(). You can easily verify that this still compiles and works correctly.

The first question then is, why does this compile and work? After all, the third parameter of find_words() expects a reference to a std::string object, but the argument that we’ve passed is a string literal. And a string literal is, as you may recall, of type const char[]—array of characters—and therefore definitely not a std::string object. Naturally, you already know the answer from the previous section: the compiler must be applying some form of implicit conversion. That is, the function’s reference will not actually refer to the literal but instead to some temporary std::string object the compiler has implicitly created somewhere in memory. We will explain in later chapters exactly how such conversions work for nonfundamental types, but for now believe us when we say that in this case the temporary string object will be initialized with a full copy of all characters in the string literal.

Being the careful reader that you are, you have now realized why passing strings by reference-to-const is still somewhat flawed. Our motivation for using references was to avoid copies, but, alas, string literals still become copied when passed to reference-to-const-std::string parameters. They become copied into temporary std::string objects that emanate from implicit conversions.

This brings us to the second and real question of this section: how to create functions that never copy input string arguments, not even string literals or other character arrays? And we do not want to use const char* for this because you’d have to pass the string’s length along separately as well, and then you’d miss out on the many nice helper functions offered by std::string.

The answer is provided by std::string_view , a type defined in the string_view header, added to the Standard Library with C++17. Values of this type will act analogously to values of type const std::string—mind the const!—only with one major difference: the strings they encapsulate can never be modified through their public interface. That is, string_views are in a way inherently const. To paraphrase The Boss , you can look (view) but not touch a string_view’s characters. Interestingly, this limitation implies that these objects, unlike std::strings, do not need their own copy of the character array they operate on. Instead, it suffices they simply point to any character sequence stored inside either an actual std::string object, a string literal, or any other character array for that matter. Because it does not involve copying an entire character array, initializing and copying a string_view is very cheap.

So, std::strings copy characters when created, implicitly or explicitly, and string_views don’t. All this might get you wondering how object creation works exactly and how your Standard Library implementation makes this behave differently for string_views and strings. And not to worry: we explain it in depth in upcoming chapters. For now, though, remember the following best-practice guideline:

Tip

Always use the type std::string_view instead of const std::string& for input string parameters. While there is nothing wrong with using const std::string_view&, you might as well pass std::string_view by value because copying these objects is cheap.

Using String View Function Parameters

For our new version of Ex8_08 (see earlier), the find_words() function is thus probably better declared as follows:

In many cases, nothing more would have to change about the program. The std::string_view type can mostly be used as a drop-in replacement for either const std::string& or const std::string. But not in our example, which is fortunate because it allows us to explain when it might go wrong and why. To make the find_words() function definition compile with its new and improved signature, you have to slightly alter it, like so (also available in Ex8_08A.cpp):

The modification we had to make is in the second-to-last statement, which originally did not include the explicit std::string{ … } initialization:

The compiler, however, will refuse any and all implicit conversions of std::string_view objects to values of type std::string (give it a try!). The rationale behind this deliberate restriction is that you normally use string_ view to avoid more expensive string copy operations, and converting a string_view back to a std::string always involves copying the underlying character array. To protect you from accidentally doing so, the compiler is not allowed to ever implicitly make this conversion. You always have to explicitly add the conversion in this direction yourself.

Note

There exist two other cases where a string_view is not exactly equivalent to const string. First, string_view does not provide a c_str() function to convert it to a const char* array. Luckily, it does share with std::string its data() function, though, which for most intents and purposes is equivalent. Second, string_views cannot be concatenated using the addition operator (+). To use a string_view value view in a concatenation expression, you have to convert it to a std::string first, for instance using string{view}.

String literals are generally not that big, so you may wonder whether it is really such a big deal if they are copied. Perhaps not. But a std::string_view can be created from any C-style character array, which can be as big as you want. So, while for find_words() you likely did not gain much from making seperators a string_view, for the other argument, str, it could indeed make a big difference, as illustrated by this snippet:

In this case, the char array is assumed to be terminated by a null character element, a convention common in C and C++ programming. If this is not the case, you’ll have to use something more of this form:

The bottom line in either case is that if you use std::string_view, the huge text array is not copied when passing it to find_words(), whereas it would be if you’d use const std::string&.

Default Argument Values

There are many situations in which it would be useful to have default argument values for one or more function parameters. This would allow you to specify an argument value only when you want something different from the default . A simple example is a function that outputs a standard error message. Most of the time, a default message will suffice, but occasionally an alternative is needed. You can do this by specifying a default parameter value in the function prototype. You could define a function to output a message like this:

You specify the default argument value like this:

If both are separate, you need to specify default values in the function prototype and not in the function definition. The reason is that when resolving the function calls, the compiler needs to know whether a given number of arguments is acceptable.

To output the default message, you call such functions without the corresponding argument:

To output a particular message, you specify the argument:

In the previous example, the parameter happens to be passed by value. You specify default values for nonreference and reference parameters in the same manner:

From what you learned in previous sections, it also should come as no surprise that default values for which the implicit conversion requires the creation of a temporary object—as is in the previous example—are illegal for reference-to-non-const parameters. Hence, the following should not compile:

Specifying default parameter values can make functions simpler to use. Naturally, you aren’t limited to just one parameter with a default value.

Multiple Default Parameter Values

All function parameters that have default values must be placed together at the end of the parameter list. When an argument is omitted in a function call, all subsequent arguments in the list must also be omitted. Thus, parameters with default values should be sequenced from the least likely to be omitted to the most likely at the end. These rules are necessary for the compiler to be able to process function calls.

Let’s contrive an example of a function with several default parameter values. Suppose that you wrote a function to display one or more data values, several to a line, as follows:

The data parameter is an array of values to be displayed, and count indicates how many there are. The third parameter of type string_view specifies a title that is to head the output. The fourth parameter determines the field width for each item, and the last parameter is the number of data items per line. This function has a lot of parameters. It’s clearly a job for default parameter values! Here’s an example:

The definition of show_data() in Ex8_11.cpp can be taken from earlier in this section. Here’s the output:

The prototype for show_data() specifies default values for all parameters except the first. You have five ways to call this function: you can specify all five arguments, or you can omit the last one, the last two, the last three, or the last four. You can supply just the first to output a single data item, as long as you are happy with the default values for the remaining parameters.

Remember that you can omit arguments only at the end of the list; you are not allowed to omit the second and the fifth. Here’s an example:

Arguments to main()

You can define main() so that it accepts arguments that are entered on the command line when the program executes. The parameters you can specify for main() are standardized; either you can define main() with no parameters or you can define main() in the following form:

The first parameter, argc, is a count of the number of string arguments that were found on the command line. It is type int for historical reasons, not size_t as you might expect from a parameter that cannot be negative. The second parameter, argv, is an array of pointers to the command-line arguments, including the program name. The array type implies that all command-line arguments are received as C-style strings. The program name used to invoke the program is normally recorded in the first element of argv, argv[0].1 The last element in argv (argv[argc]) is always nullptr, so the number of elements in argv will be argc+1. We’ll give you a couple of examples to make this clear. Suppose that to run the program, you enter just the program name on the command line:

In this case, argc will be 1, and argv[] contains two elements. The first is the address of the string "Myprog", and the second will be nullptr.

Suppose you enter this:

Now argc will be 4, and argv will have five elements. The first four elements will be pointers to the strings "Myprog", "2", "3.5", and "Rip Van Winkle". The fifth element, argv[4], will be nullptr.

What you do with the command-line arguments is entirely up to you. The following program shows how you access the command-line arguments:

This lists the command-line arguments, including the program name. Command-line arguments can be anything at all—file names to a file copy program, for example, or the name of a person to search for in a contact file. They can be anything that is useful to have entered when program execution is initiated.

Returning Values from a Function

As you know, you can return a value of any type from a function. This is quite straightforward when you’re returning a value of one of the basic types, but there are some pitfalls when you are returning a pointer or a reference.

Returning a Pointer

When you return a pointer from a function, it must contain either nullptr or an address that is still valid in the calling function. In other words, the variable pointed to must still be in scope after the return to the calling function. This implies the following absolute rule:

Caution

Never return the address of an automatic, stack-allocated local variable from a function.

Suppose you define a function that returns the address of the larger of two argument values. This could be used on the left of an assignment so that you could change the variable that contains the larger value, perhaps in a statement such as this:

You can easily be led astray when implementing this. Here’s an implementation that doesn’t work:

It’s relatively easy to see what’s wrong with this: a and b are local to the function. The argument values are copied to the local variables a and b. When you return &a or &b, the variables at these addresses no longer exist back in the calling function. You usually get a warning from your compiler when you compile this code.

You can specify the parameters as pointers:

If you do, do not forget to also dereference the pointers. The previous condition (a > b) would still compile, but then you’d not be comparing the values themselves. You’d instead be comparing the addresses of the memory locations holding these values. You could call the function with this statement:

A function to return the address of the larger of two values is not particularly useful, but let’s consider something more practical. Suppose we need a program to normalize a set of values of type double so that they all lie between 0.0 and 1.0 inclusive. To normalize the values, we can first subtract the minimum sample value from them to make them all non-negative. Two functions will help with that, one to find the minimum and another to adjust the values by any given amount. Here’s a definition for the first function:

You shouldn’t have any trouble seeing what’s going on here. The index of the minimum value is stored in index_min, which is initialized arbitrarily to refer to the first array element. The loop compares the value of the element at index_min with each of the others, and when one is less, its index is recorded in index_min. The function returns the address of the minimum value in the array. It probably would be more sensible to return the index, but we’re demonstrating pointer return values among other things. The first parameter is const because the function doesn’t change the array. With this parameter const you must specify the return type as const. The compiler will not allow you to return a non-const pointer to an element of a const array.

A function to adjust the values of array elements by a given amount looks like this:

This function adds the value of the third argument to each array element. The return type could be void so it returns nothing, but returning the address of data allows the function to be used as an argument to another function that accepts an array. Of course, the function can still be called without storing or otherwise using the return value.

You could combine using this with the previous function to adjust the values in an array, samples, so that all the elements are non-negative:

The third argument to shift_range() calls smallest(), which returns a pointer to the minimum element. The expression negates the value, so shift_range() will subtract the minimum from each element to achieve what we want. The elements in data are now from zero to some positive upper limit. To map these into the range from 0 to 1, we need to divide each element by the maximum element. We first need a function to find the maximum:

This works in essentially the same way as smallest(). We could use a function that scales the array elements by dividing by a given value:

Dividing by zero would be a disaster, so when the third argument is zero, the function just returns the original array. We can use this function in combination with largest() to scale the elements that are now from 0 to some maximum to the range 0 to 1:

Of course, what the user would probably prefer is a function that will normalize an array of values, thus avoiding the need to get into the gory details:

Remarkably this function requires only one statement. Let’s see if it all works in practice:

If you compile and run this example complete with the definitions of largest(), smallest(), shift_range(), scale_range(), and normalize_range() shown earlier, you should get the following output:

The output demonstrates that the results are what was required. The last two statements in main() could be condensed into one by passing the address returned by normalize_range() as the first argument to show_data():

This is more concise but clearly not necessarily clearer.

Returning a Reference

Returning a pointer from a function is useful, but it can be problematic. Pointers can be null, and dereferencing nullptr generally results in the failure of your program. The solution, as you will surely have guessed from the title of this section, is to return a reference. A reference is an alias for another variable, so we can state the following golden rule for references:

Caution

Never return a reference to an automatic local variable in a function.

By returning a reference, you allow a function call to the function to be used on the left of an assignment. In fact, returning a reference from a function is the only way you can enable a function to be used (without dereferencing) on the left of an assignment operation.

Suppose you code a larger() function like this:

The return type is “reference to string,” and the parameters are references to non-const values. Because you want to return a reference-to-non-const referring to one or other of the arguments, you must not specify the parameters as const.

You could use the function to change the larger of the two arguments, like this:

Because the parameters are not const, you can’t use string literals as arguments; the compiler won’t allow it. A reference parameter permits the value to be changed, and changing a constant is not something the compiler will knowingly go along with. If you make the parameters const, you can’t use a reference-to-non-const as the return type.

You’re not going to examine an extended example of using reference return types at this moment, but you can be sure that you’ll meet them again before long. As you’ll discover, reference return types become essential when you are creating your own data types using classes.

Returning vs. Output Parameters

You now know two ways a function can pass the outcome it produces back to its caller: it can either return a value or put values into output parameters. In Ex8_08, you encountered the following example of the latter:

Another way of declaring this function, however, is as follows:

When your function outputs an object, you of course do not want this object to be copied, especially if this object is as expensive to copy as, for instance, a vector of strings. Prior to C++11, the recommended approach then was mostly to use output parameters. This was the only way you could make absolutely sure that all strings in the vector<> did not get copied when returning the vector<> from the function. This advice has changed drastically with C++11, however:

Tip

In modern C++, you should generally prefer returning values over output parameters. This makes function signatures and calls much easier to read. Arguments are for input, and all output is returned. The mechanism that makes this possible is called move semantics and is discussed in detail in Chapter 17. In a nutshell, move semantics ensures that returning objects that manage dynamically allocated memory—such as vectors and strings—no longer involves copying that memory and is therefore very cheap. Notable exceptions are arrays or objects that contain an array, such as std::array<>. For these it is still better to use output parameters.

Return Type Deduction

Just like you can let the compiler deduce the type of a variable from its initialization, you can have the compiler deduce the return type of a function from its definition. You can write the following, for instance:

From this definition, the compiler will deduce that the return type of getAnswer() is int. Naturally, for a type name as short as int, there is little point in using auto. In fact, it even results in one extra letter to type. But later you’ll encounter type names that are much more verbose (iterators are a classical example). For these, type deduction can save you time. Or you may want your function to return the same type as some other function, and for whatever reason you do not feel the need to look up what type that is or to type it out. In general, the same considerations apply here as for using auto for declaring variables. If it is clear enough from the context what the type will be or if the exact type name matters less for the clarity of your code, return type deduction can be practical.

Note

Another context where return type deduction can be practical is to specify the return type of a function template. You’ll learn about this in the next chapter.

The compiler can even deduce the return type of a function with multiple return statements, provided their expressions evaluate to a value of exactly the same type. That is, no implicit conversions will be performed because the compiler has no way to decide which of the different types to deduce. For instance, consider the following function to obtain a string’s first letter in the form of another string:

Replace auto in the function with std::string_view. This will allow the compiler to perform the necessary type conversions for you.

Replace the first return statement with return std::string_view{" "}. The compiler will then deduce std::string_view as the return type.

Replace the second return statement with return text.substr(0, 1).data(). Because the data() function—as your Standard Library documentation will confirm—returns a const char* pointer, the return type of getFirstLetter() then deduces to const char* as well.

Return Type Deduction and References

You need to take extra care with return type deduction if you want the return type to be a reference. Suppose you write the larger() function shown earlier using an auto-deduced return type instead:

Explicitly specify the std::string& return type as before.

Specify auto& instead of auto. Then the return type will always be a reference.

While discussing all details and intricacies of C++ type deduction is well outside our scope, the good news is that one simple rule covers most cases:

Caution

auto never deduces to a reference type, always to a value type. This implies that even when you assign a reference to auto, the value still gets copied. This copy will moreover not be const, unless you explicitly use const auto. To have the compiler deduce a reference type, you can use auto& or const auto&.

Naturally, this rule is not specific to return type deduction. The same holds if you use auto for local variables as well:

In the previous code snippet, auto_test has type std::string and therefore contains a copy of test. Unlike ref_to_test, this new copy isn’t const anymore either.

Working with Optional Values

When writing your own functions, you will often encounter input arguments that are optional or functions that can return a value only if nothing went wrong. Consider the following function prototype:

From this declaration, you can imagine that this function searches a given string for a given character, back to front, starting from a given starting index. Once found, it will then return the index of the last occurrence of that character. But what happens if the character doesn’t occur in the string? And what do you do if you want the algorithm to consider the entire string? Of course, passing string.length()-1 as a start index will work, but that’s somewhat tedious. Would it perhaps work as well if you pass, say, -1 to the third argument? Without interface documentation or a peek at the implementation code, there is no way of knowing how this function will behave exactly.

The traditional solution is to pick some specific value or values to use when the caller wants the function to use its default settings or to return when no actual value could be computed. A typical choice for indices is -1. A possible specification for find_last_in_string() would thus be that it returns -1 if char_to_find does not occur in the given string and that the entire string is searched if -1 or any negative value is passed as a start_index. In fact, std::string and std::string_view define their own find() functions, and they use the special size_t constants std::string::npos and std::string_view::npos for these purposes.

The problem is that, in general, it can be hard to remember how every function encodes “not provided” or “not computed.” Conventions tend to differ between different libraries or even within the same library. Some may return 0 upon failure, and others may return a negative value. Some may accept nullptr for a const char* parameter, and others won’t. And so on.

To aid the users of a function, optional parameters are typically given a valid default value. Here’s an example:

However, this technique, of course, does not extend to return values. Another problem with the traditional approaches is that, in general, there may not even be an obvious way of encoding an optional value. One reason for this may be the type of the optional value. Think about it, how would you encode an optional bool, for instance? Another reason would be the specific situation. Suppose, for instance, that you need to define a function that reads a configuration override from a given configuration file. Then you’d probably prefer to give that function the following form:

But what should happen if the configuration file does not contain a value with the given name? Because this is intended to be a generic function, you cannot a priori assume that an int value such as 0, -1, or any other value isn’t a valid configuration override as well. Traditional workarounds include the following:

While these work, the C++17 Standard Library now offers std::optional<>, a utility we believe can help make your function declarations much cleaner and easier to read.

std::optional

As of C++17, the Standard Library provides std::optional<>, which constitutes an interesting alternative to all the implicit encodings of optional values we discussed earlier. Using this auxiliary type, any optional int can be explicitly declared with optional<int> as follows:

The fact that these parameters or return values are optional is now stated explicitly, making these prototypes self-documenting. Your code therefore becomes much easier to use and read than code that uses traditional approaches. Let’s take a look at the basic use of std::optional<> in some real code:

The output produced by this program is as follows:

To showcase std::optional<>, we define find_last(), a variation of the find_last_in_string() function we used as an example earlier. Notice that because find_last() uses unsigned size_t indexes instead of int indexes, using -1 as a default value would already be less obvious here. A second, more interesting difference, though, is the default value for the function’s third argument. This value, std::nullopt, is the special constant defined by the Standard Library to initialize optional<T> values that do not (yet) have a T value assigned. We will see shortly why using this as a default parameter value can be interesting.

After the function’s prototype, you see the program’s main() function. In main(), we call find_last() three times to search for the letters 'a', 'b', and 'i' in some sample string. And there is really nothing surprising about the calls themselves. If you want a nondefault start index, you simply pass a number to find_last(), like we did for our third call. The compiler then implicitly converts this number to a std::optional<> object, exactly like you’d expect. If you’re OK with the default starting index, though, you could always pass std::nullopt explicitly. We opted to have the default parameter value take care of that for us, though.

How you can check whether an optional<> value returned by find_last() was assigned an actual value

How you subsequently extract this value from the optional<> to use it

For the former, main() shows three alternatives, in this order: either you have the compiler convert the optional<> to a Boolean for you or you call the has_value() function or you compare the optional<> to nullopt. For the latter, main() presents two options: you can either use the * operator or call the value() function. Assigning the optional<size_t> return value directly to a size_t, however, would not be possible. The compiler cannot convert values of type optional<size_t> to values of type size_t.

From the body of find_last(), aside from some interesting challenges with empty strings and unsigned index types, we’d mostly like you to pay attention to two more aspects related to optional<>. First, notice that returning a value is straightforward. Either you return std::nullopt or you return an actual value. Both will then be converted to a suitable optional<> by the compiler. Second, we’ve used value_or() there. If the optional<> start_index contains a value, this function will return the same as value(); if it does not contain a value, value_or() simply evaluates to the value you pass it as an argument. The value_or() function is therefore a welcome alternative to equivalent if-else statements or conditional operator expressions that would first call has_value() and then value().

Note

Ex8_14 covers most there is to know about std::optional<>. As always, if you need to know more, please consult your favorite Standard Library reference. One thing to note already, though, is that next to the * operator, std::optional<> also supports the -> operator. That is, in the following example the last two statements are equivalent:

Note that while this syntax makes optional <> objects look and feel like pointers, they most certainly aren’t pointers. Each optional<> object contains a copy of any value assigned to it, and this copy is not kept in the free store. That is, while copying a pointer doesn’t copy the value it points to, copying an optional<> always involves copying the entire value that is stored inside it.

Static Variables

In the functions you have seen so far, nothing is retained within the body of the function from one execution to the next. Suppose you want to count how many times a function has been called. How can you do that? One way is to define a variable at file scope and increment it from within the function. A potential problem with this is that any function in the file can modify the variable, so you can’t be sure that it’s being incremented only when it should be.