with modern CMake

Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the authors, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Commissioning Editor: Smeet Thakkar

Acquisition Editor: Noyonika Das

Content Development Editor: Francis Carneiro

Technical Editor: Sachin Sunilkumar

Copy Editor: Safis Editing

Project Coordinator: Devanshi Doshi

Proofreader: Safis Editing

Indexer: Pratik Shirodkar

Graphics: Jason Monteiro

Production Coordinator: Aparna Bhagat

First published: September 2018

Production reference: 1240918

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham

B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78847-071-1

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website mapt.io.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at service@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

Radovan Bast works at the High Performance Computing Group at UiT - The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø and leads the CodeRefinery project. He has a PhD in theoretical chemistry and contributes to a number of quantum chemistry programs as a code developer. He enjoys learning new programming languages and techniques, and teaching programming to students and researchers. He got in touch with CMake in 2008 and has ported a number of research codes and migrated a number of communities to CMake since then.

Roberto Di Remigio is a postdoctoral fellow in theoretical chemistry at UiT - The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø, Norway and Virginia Tech, USA. He is currently working on stochastic methods and solvation models. He is a developer of the PCMSolver library and the Psi4 open source quantum chemistry program. He contributes or has contributed to the development of popular quantum chemistry codes and libraries: DIRAC, MRCPP, DALTON, LSDALTON, XCFun, and ReSpect. He usually programs in C++ and Fortran.

Holding an engineering degree from ENSEEIHT and a PhD in computer science from UVSQ in France, Eric Noulard has been writing and compiling source code in a variety of languages for 20 years. A user of CMake since 2006, he has also been an active contributor to the project for several years. During his career, Eric has worked for private companies and government agencies. He is now employed by Antidot, a software vendor developing and marketing high-end information retrieval technology and solutions.

Shlomi Fish is an Israeli software developer and writer. He has been contributing to various open source and open culture projects since at least 2000. Among other endeavors, he has initiated some solvers for games, which led to him maintaining the PySol FC suite of solitaire games, adopting fortune-mod, solving over 290 Project Euler problems, and writing several stories, essays, aphorisms, and other documents.

If you're interested in becoming an author for Packt, please visit authors.packtpub.com and apply today. We have worked with thousands of developers and tech professionals, just like you, to help them share their insight with the global tech community. You can make a general application, apply for a specific hot topic that we are recruiting an author for, or submit your own idea.

Computer software is present in almost every aspect of our daily lives: it triggers our alarm clocks, fuels our communication, banking, weather forecasts, bus schedules, calendars, meetings, travel, photo albums, television, music streaming, social media, dinner and movie reservations, from dawn till dusk.

The software that surrounds us contains many layers: apps are built on top of frameworks, frameworks on top of libraries, libraries use smaller libraries and executables, all the way down to smaller and smaller software components. Libraries and executables in turn need to be built from source code. Often we only see the outermost layer, but all these layers need to be carefully organized and built. This book is about how to build libraries and executables from sources using CMake.

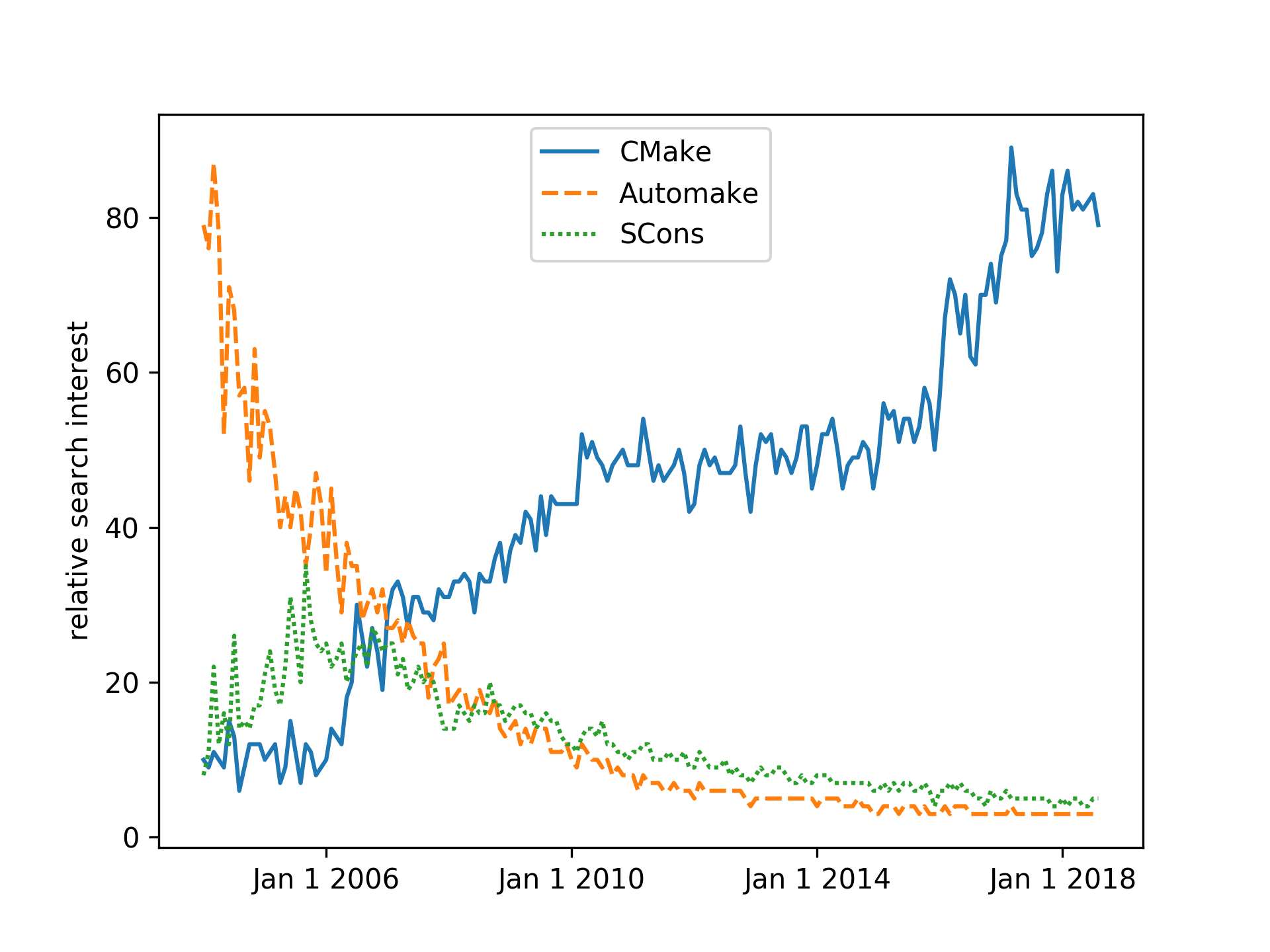

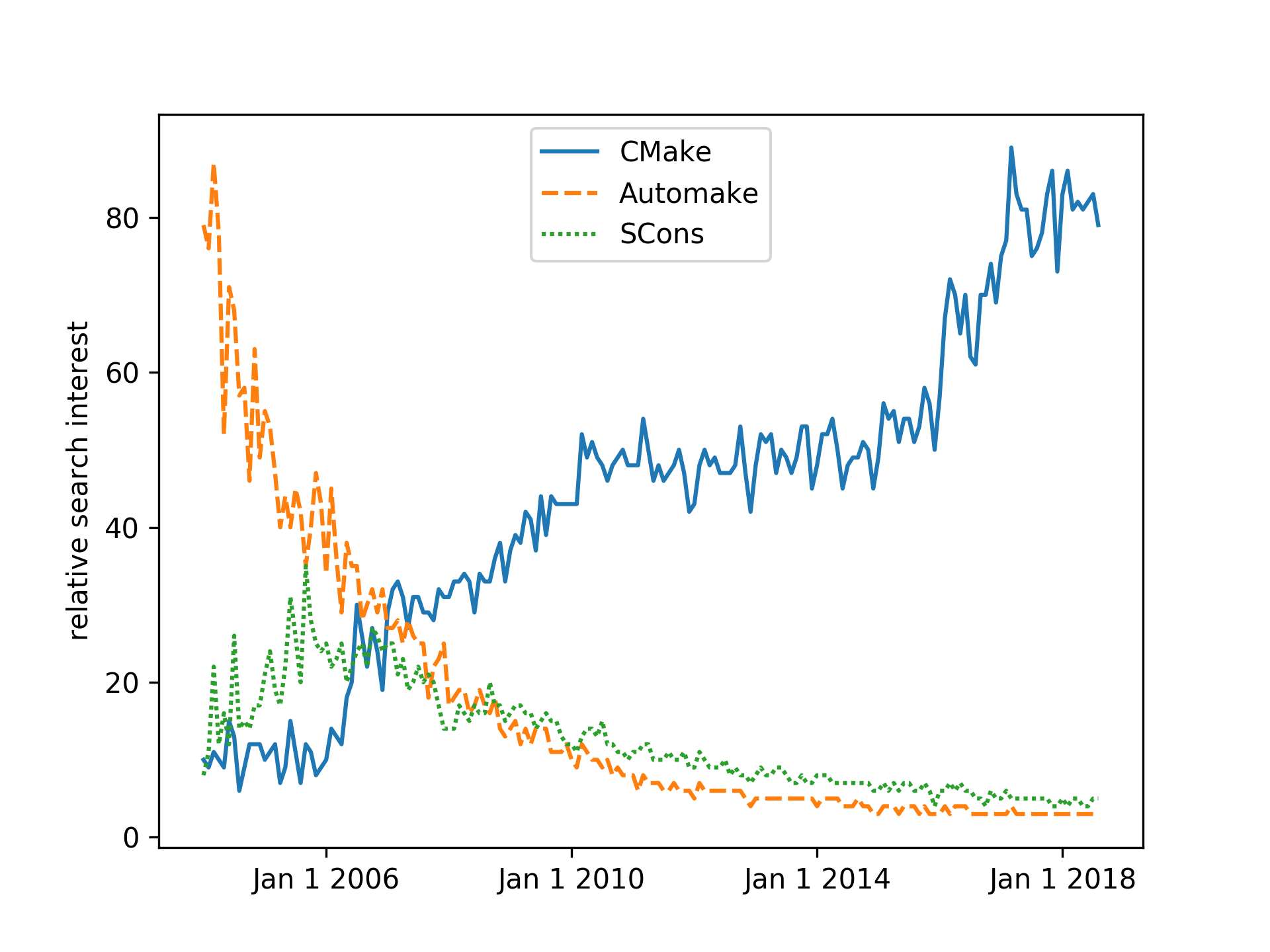

CMake and its siblings, CTest, CPack, and CDash, have emerged as the leading toolset for building software from sources, surpassing in usage and popularity many other similar tools, such as the venerated GNU Autotools and the more recent, Python-based, SCons build system.

The history of the CMake project started in 1999, when Kitware, the company behind its development, was commissioned to design a new set of tools to simplify the day-to-day software work of researchers. The goal was clear: provide a set of tools that would make it easier to configure, build, test, and deploy the same project across different platforms. A fascinating account of the ensuing design choices in the CMake project can be found at https://www.aosabook.org/en/cmake.html.

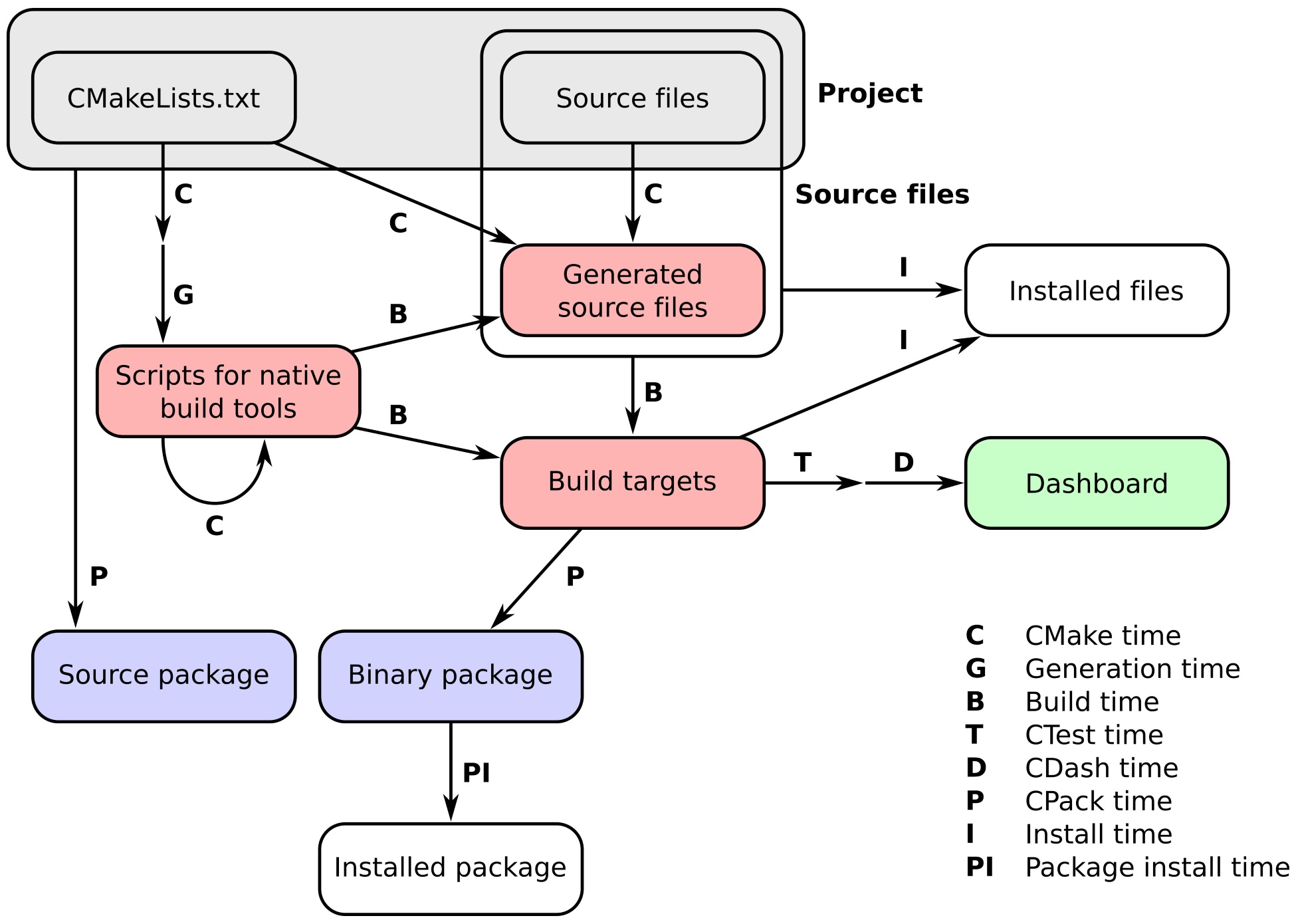

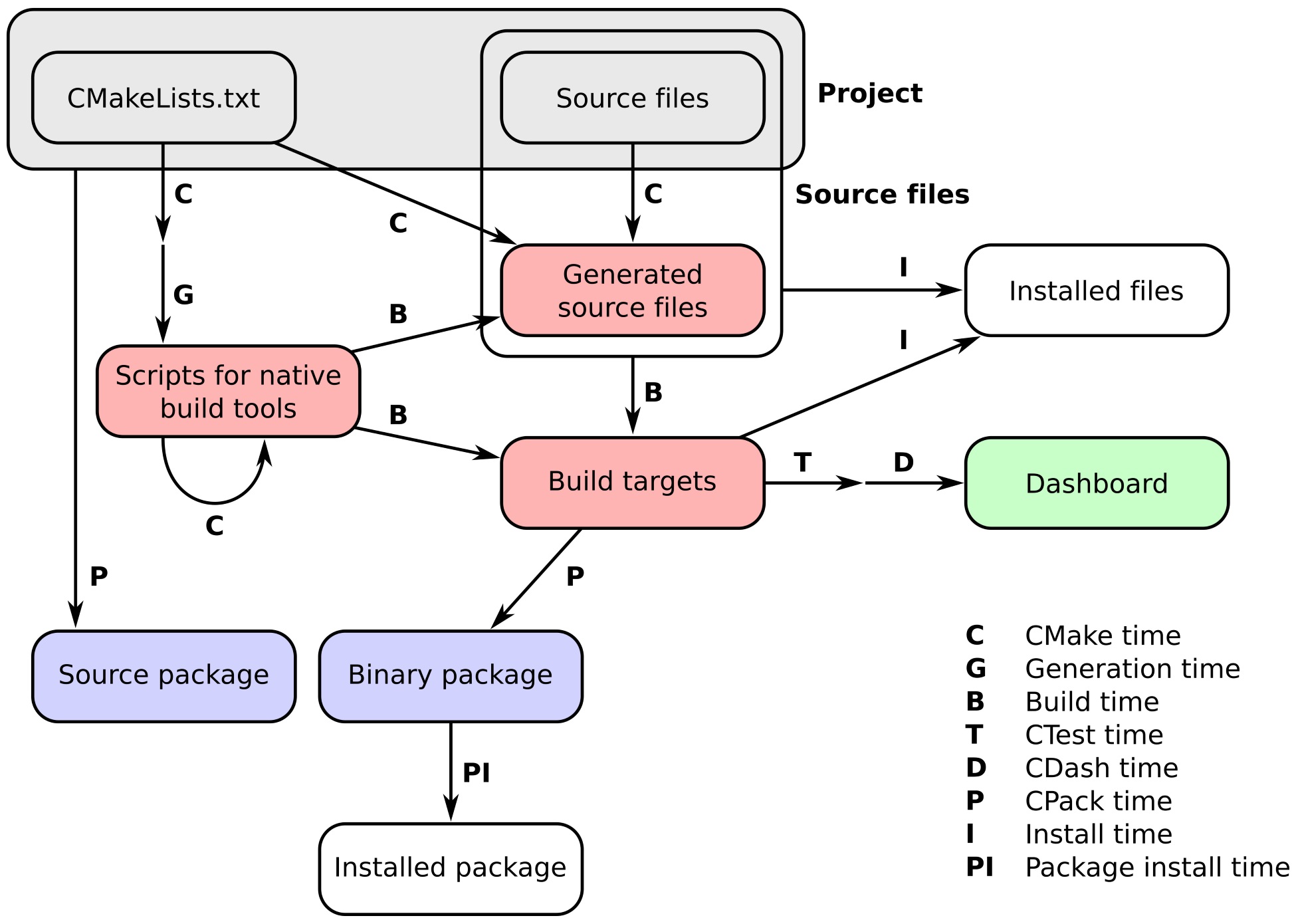

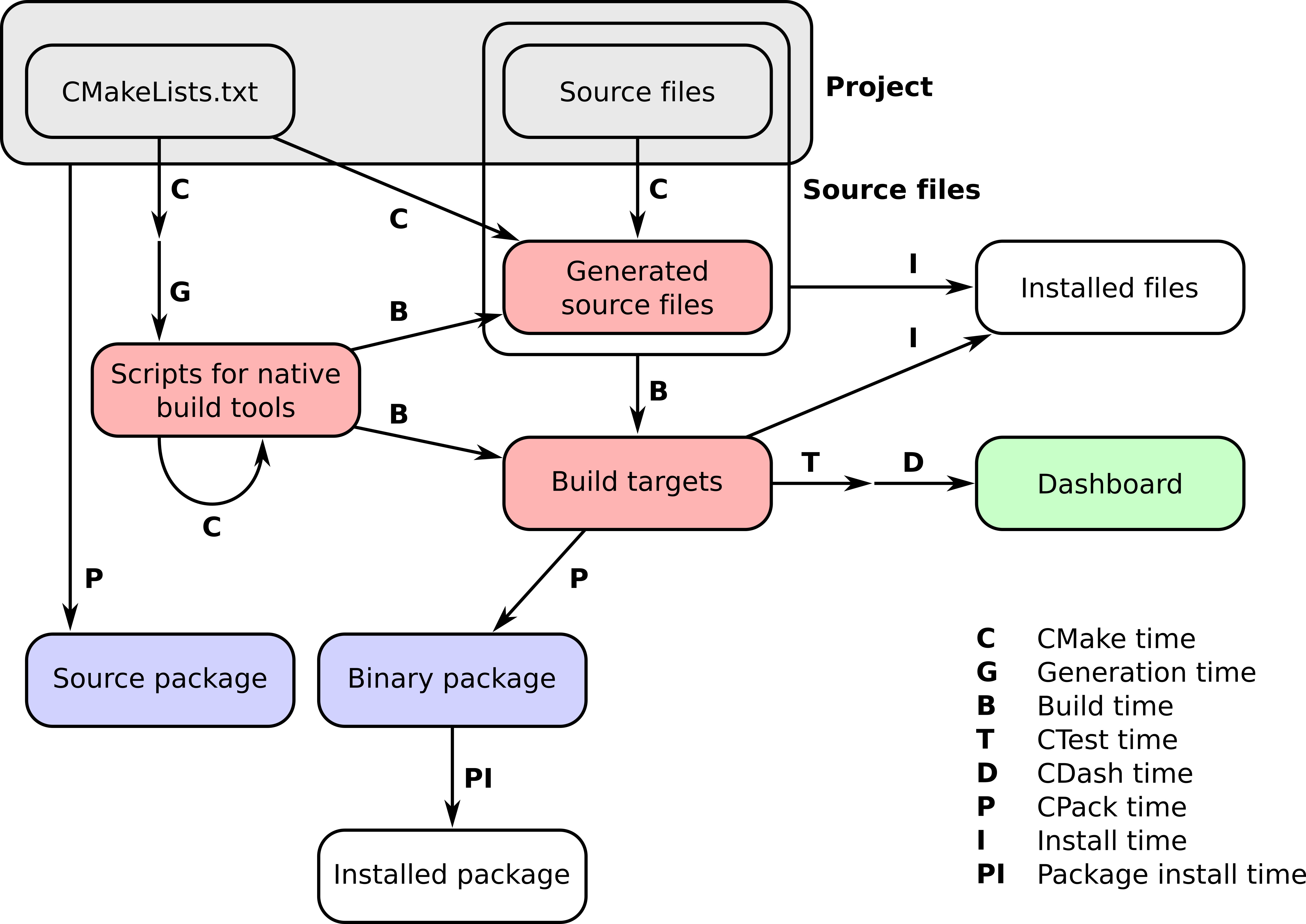

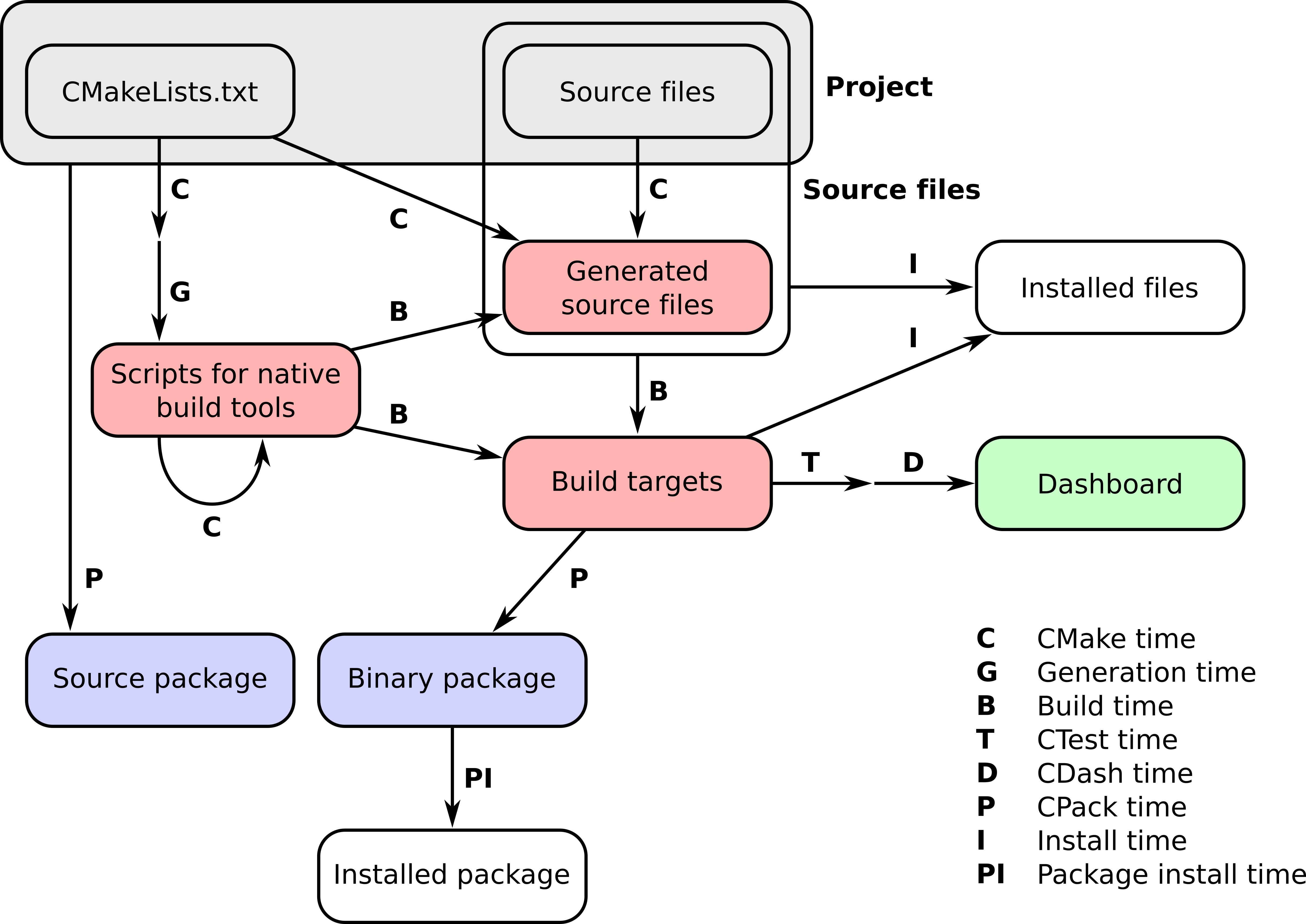

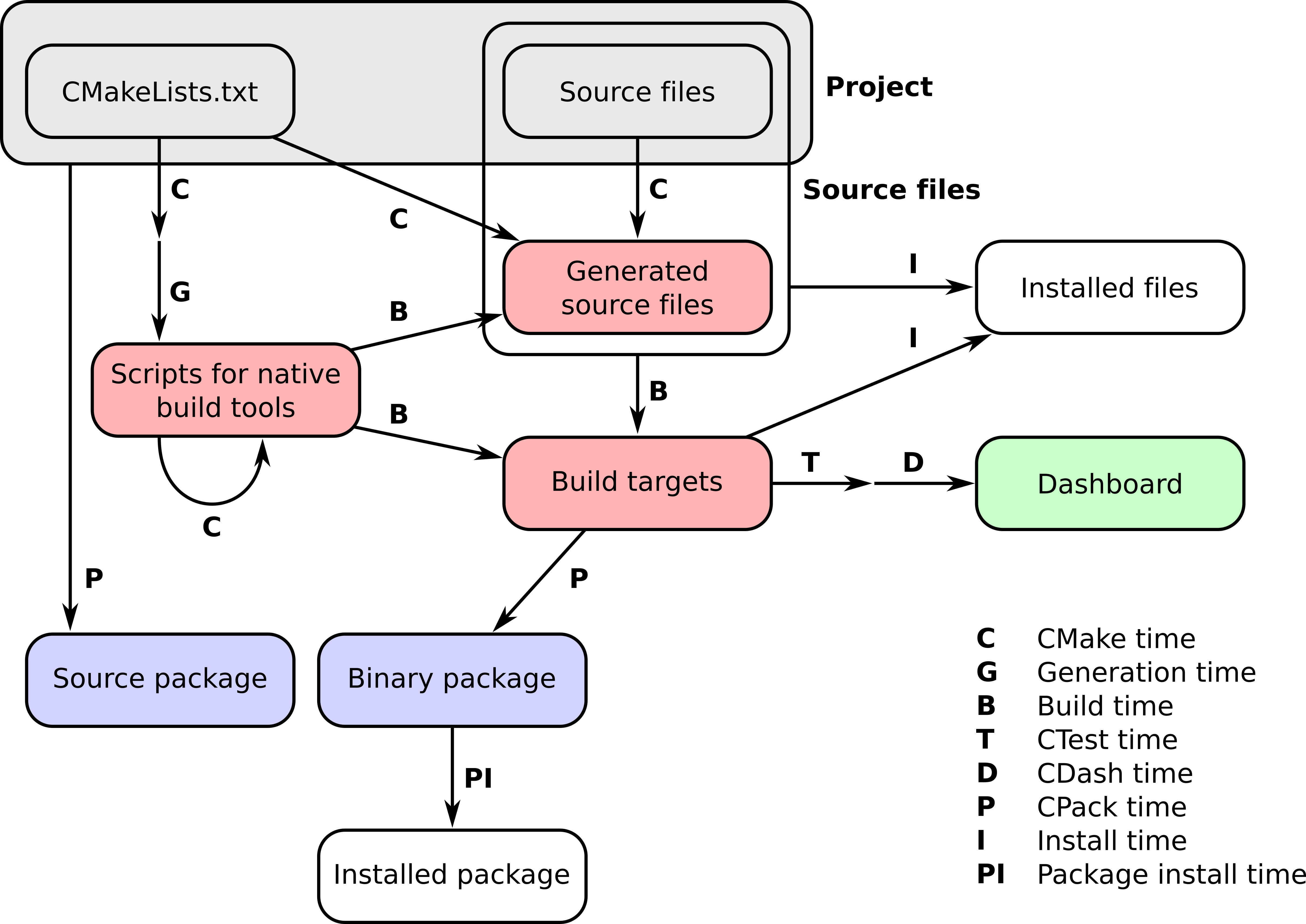

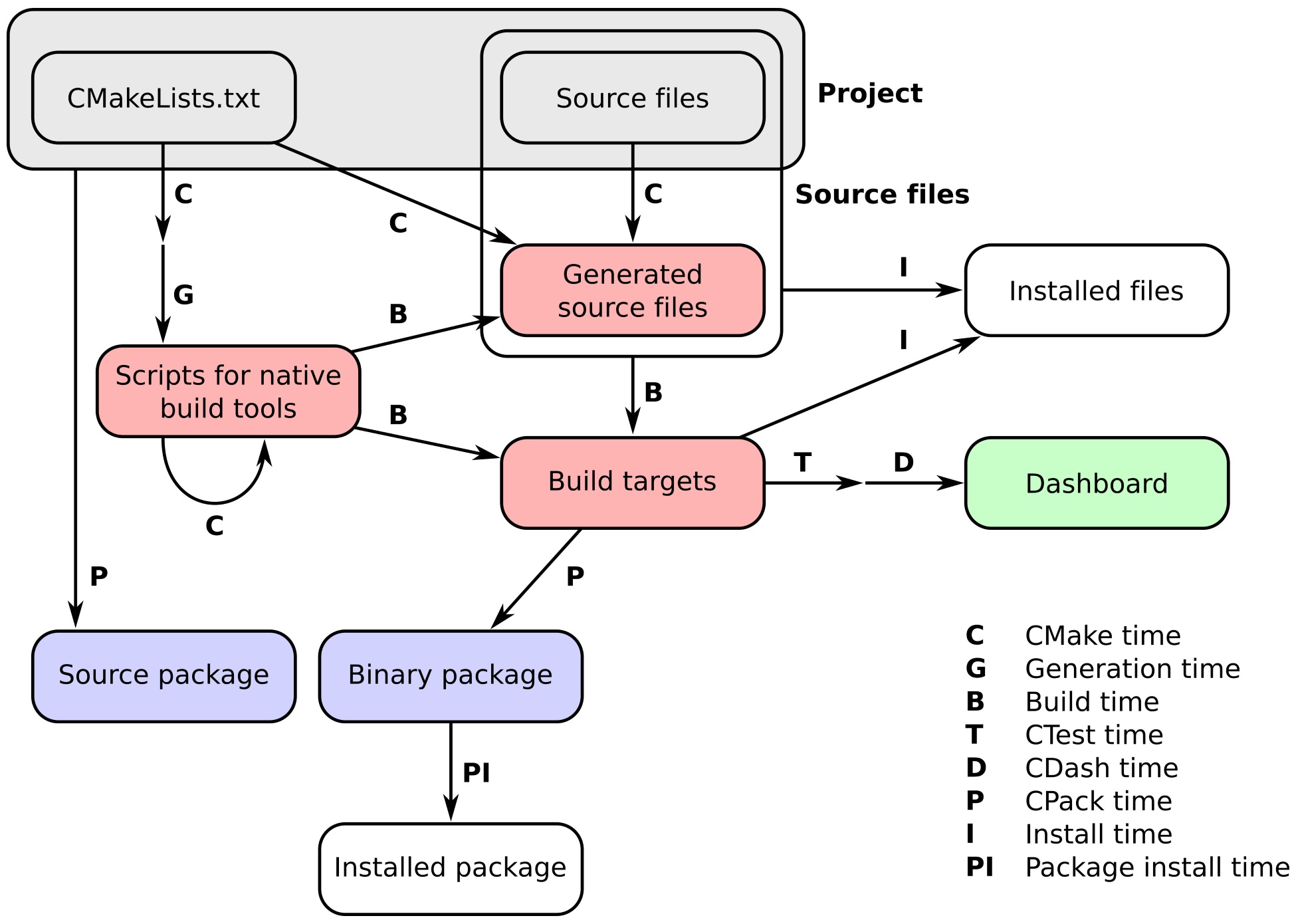

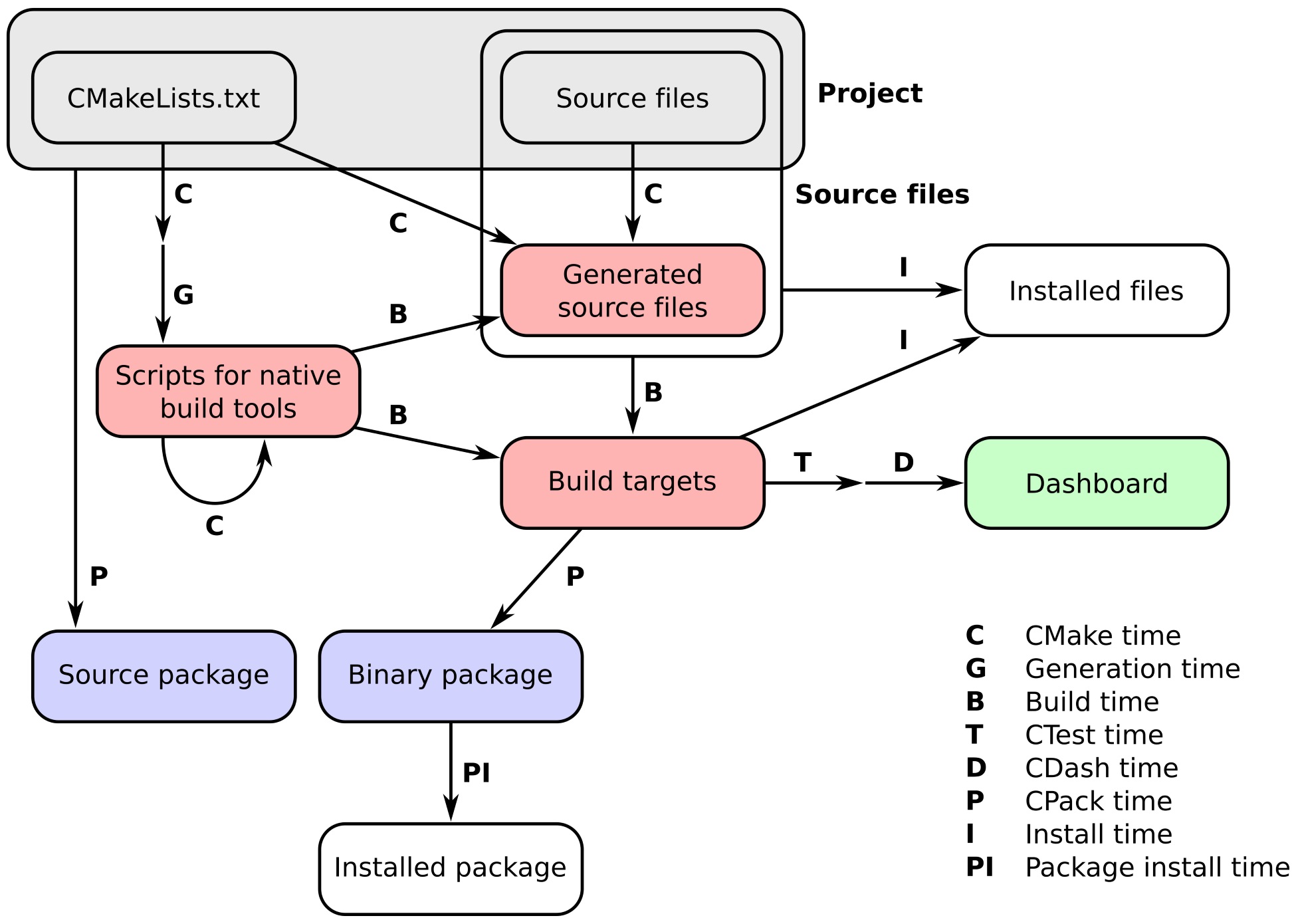

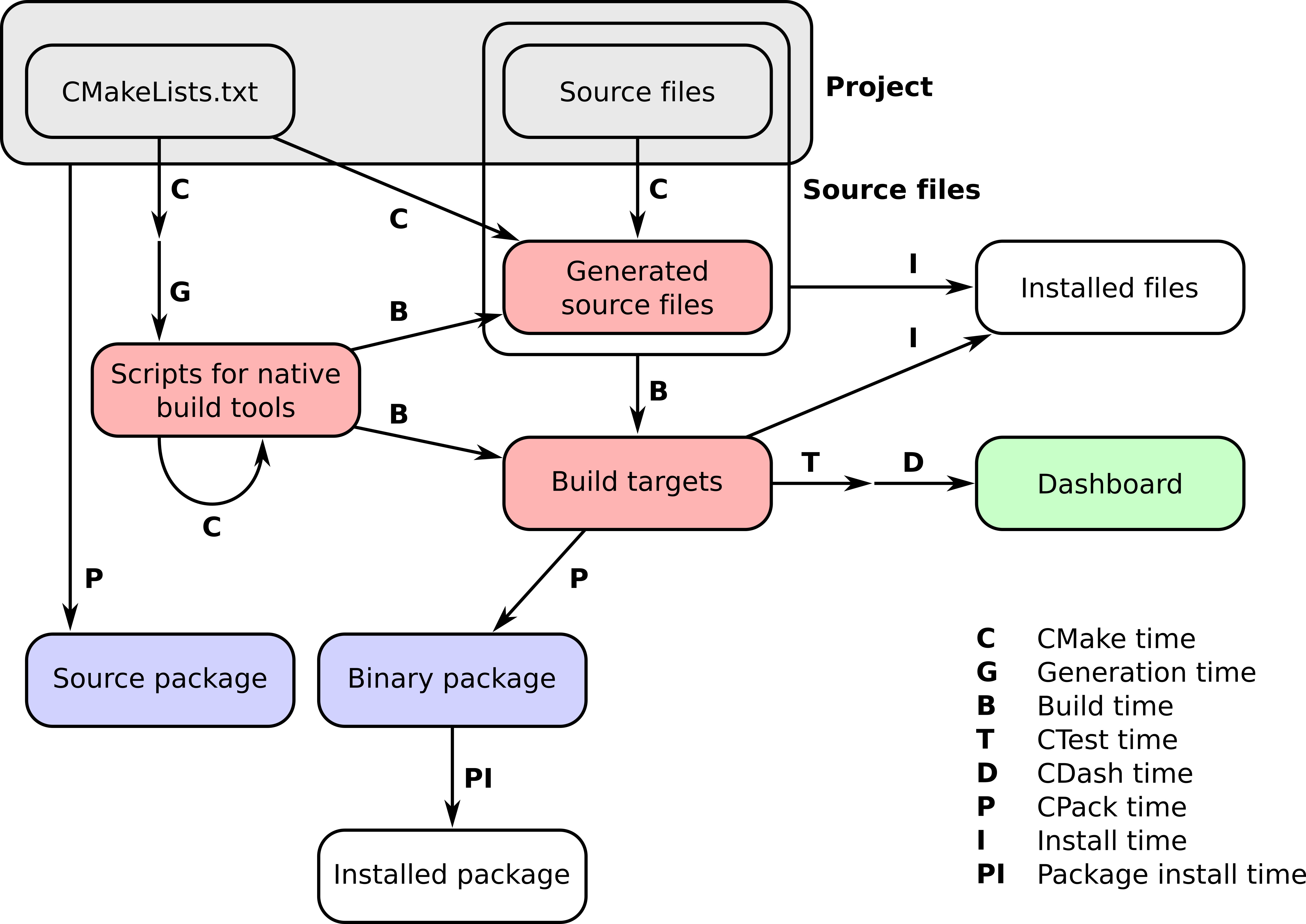

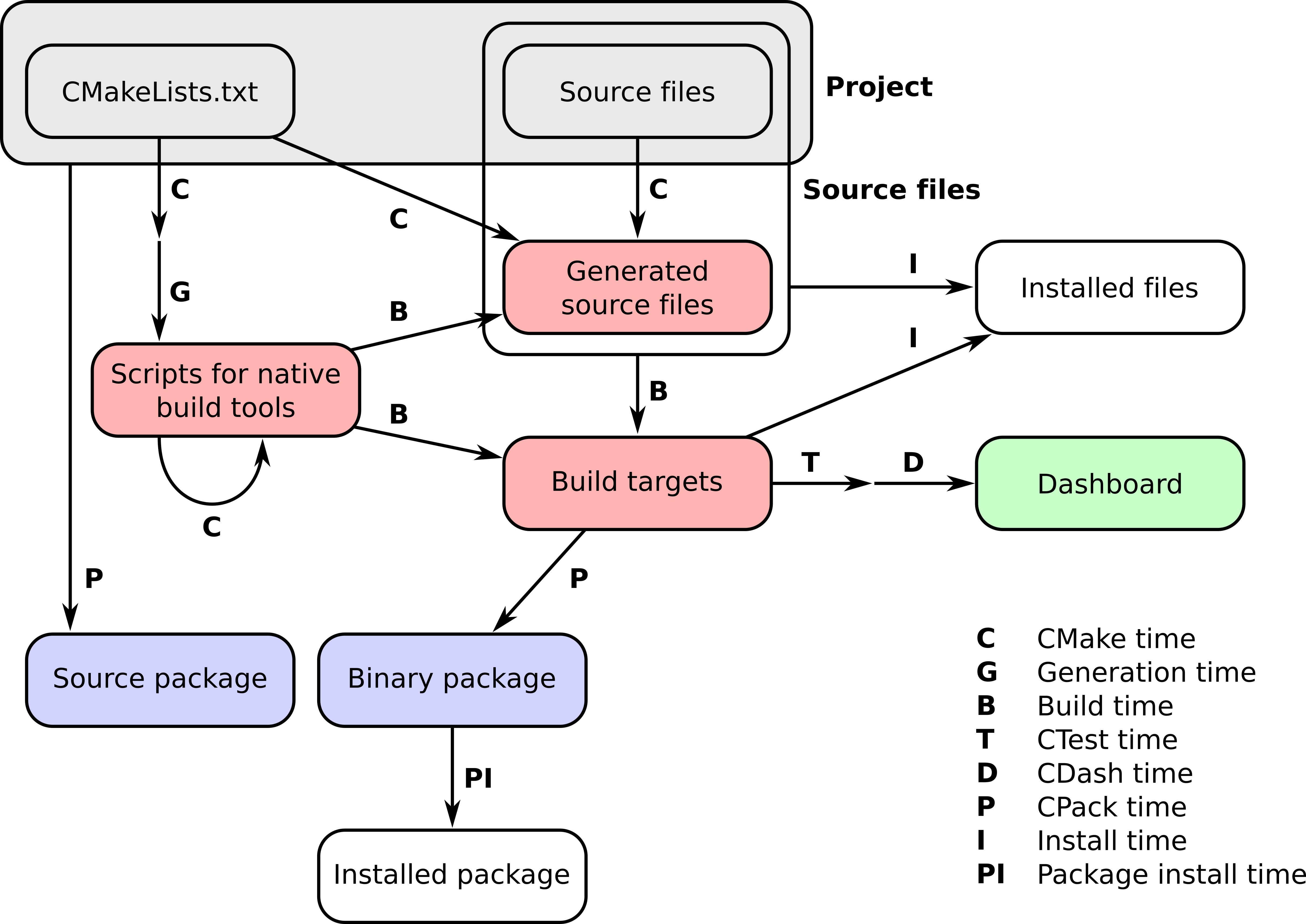

CMake is a build-system generator, offering a powerful domain-specific language (DSL) to describe what the build system should achieve. In our opinion, this is one of the main strengths of CMake, because it allows the generation of platform-native build systems with the same set of CMake scripts. The CMake software toolset gives developers full control over the whole life cycle of a given project:

An old adage goes that the deeper you dig, the more stones you will find. For the preparation of this book we have carefully been digging deeper through many software layers, with CMake being our quarry. The number of stones and artifacts that we have hit when building various software components and libraries on various platforms, each with their own quirks, has felt disheartening at times. But we believe we have cleared the ground of many stones and we are happy to share our findings and recipes with you, our readers. There will always be stones left but each stone will bring new insight and we encourage you to share this insight with the community.

Writing software that can run natively, reliably, and efficiently on many different platforms is of paramount importance for all sectors of industry and society. Software build systems take center stage in this task. They are a crucial part in the management of the software development life cycle: from incubation and prototype development to testing and all the way till packaging, deployment, and distribution. CMake is designed to help you manage these operations: if you are a software developer who wishes to manage the build system using CMake or who would like to be able to understand and modify CMake code written by others, this book is for you.

We have written this book as a progressive sequence of tasks and recipes. At each point, we introduce enough information about CMake to show how to achieve our goals, without overwhelming you with details. By the end of the book, you will be able to tackle increasingly complex operations and leverage the contents of the recipes in your own real-world projects with confidence.

We will cover these topics:

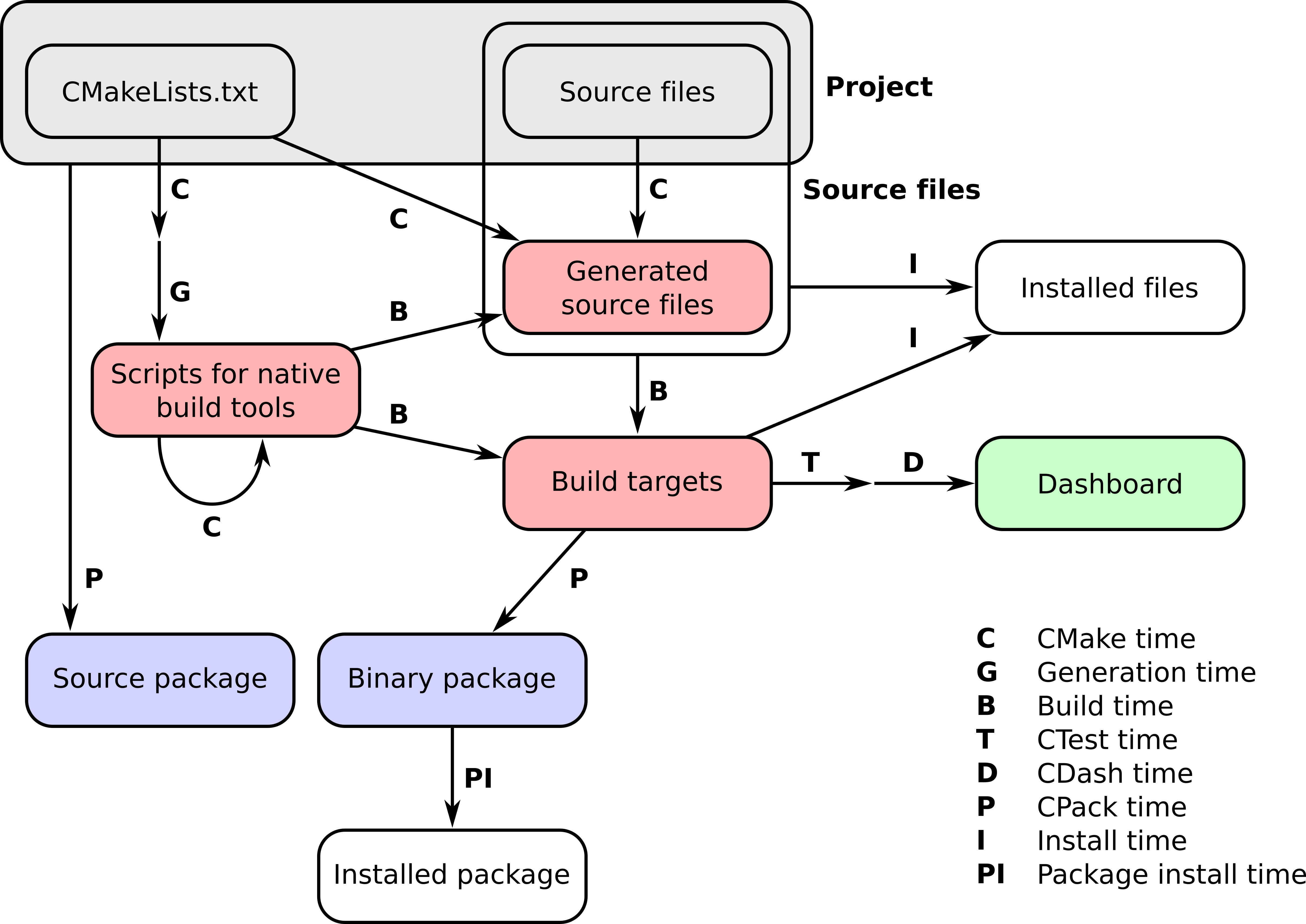

The workflow of a project managed by CMake happens in a number of stages, which we refer to as times. These can be summarized neatly in the following figure:

This book is organized as follows:

Chapter 1, From a Simple Executable to Libraries, shows how to get started configuring and building simple executables and libraries with CMake.

Chapter 2, Detecting the Environment, explains how to interact with the operating system and processor architecture using simple CMake commands.

Chapter 3, Detecting External Libraries and Programs, shows how CMake can simplify the detection of dependencies for your project.

Chapter 4, Creating and Running Tests, explains how to harness the power of CMake and CTest to define and run tests.

Chapter 5, Configure-time and Build-time Operations, shows how to perform custom operations at different stages of the build process with cross-platform CMake commands.

Chapter 6, Generating Source Code, discusses CMake commands to automatically generate source code.

Chapter 7, Structuring Projects, shows powerful CMake syntax for organizing your projects to make them more maintainable.

Chapter 8, The Superbuild Pattern, explains the powerful CMake superbuild pattern for managing critical project dependencies with control over side effects.

Chapter 9, Mixed-language Projects, shows how to build projects mixing different programming languages with the help of CMake.

Chapter 10, Writing an Installer, takes care of the installation of projects with the cross-platform power of CMake.

Chapter 11, Packaging Projects, shows how to use CPack to produce source and platform-native source archives and how to build Python and Conda packages for distribution.

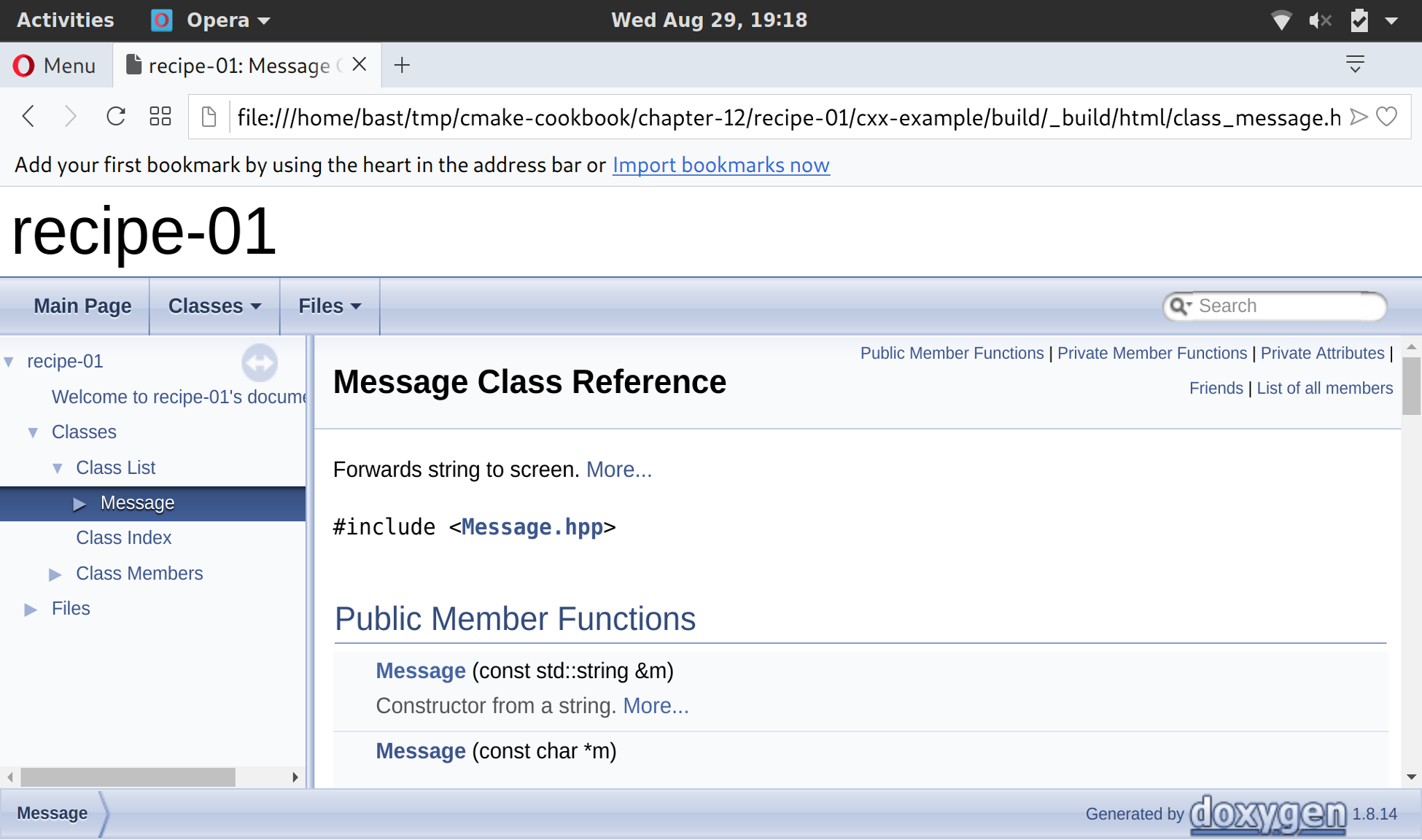

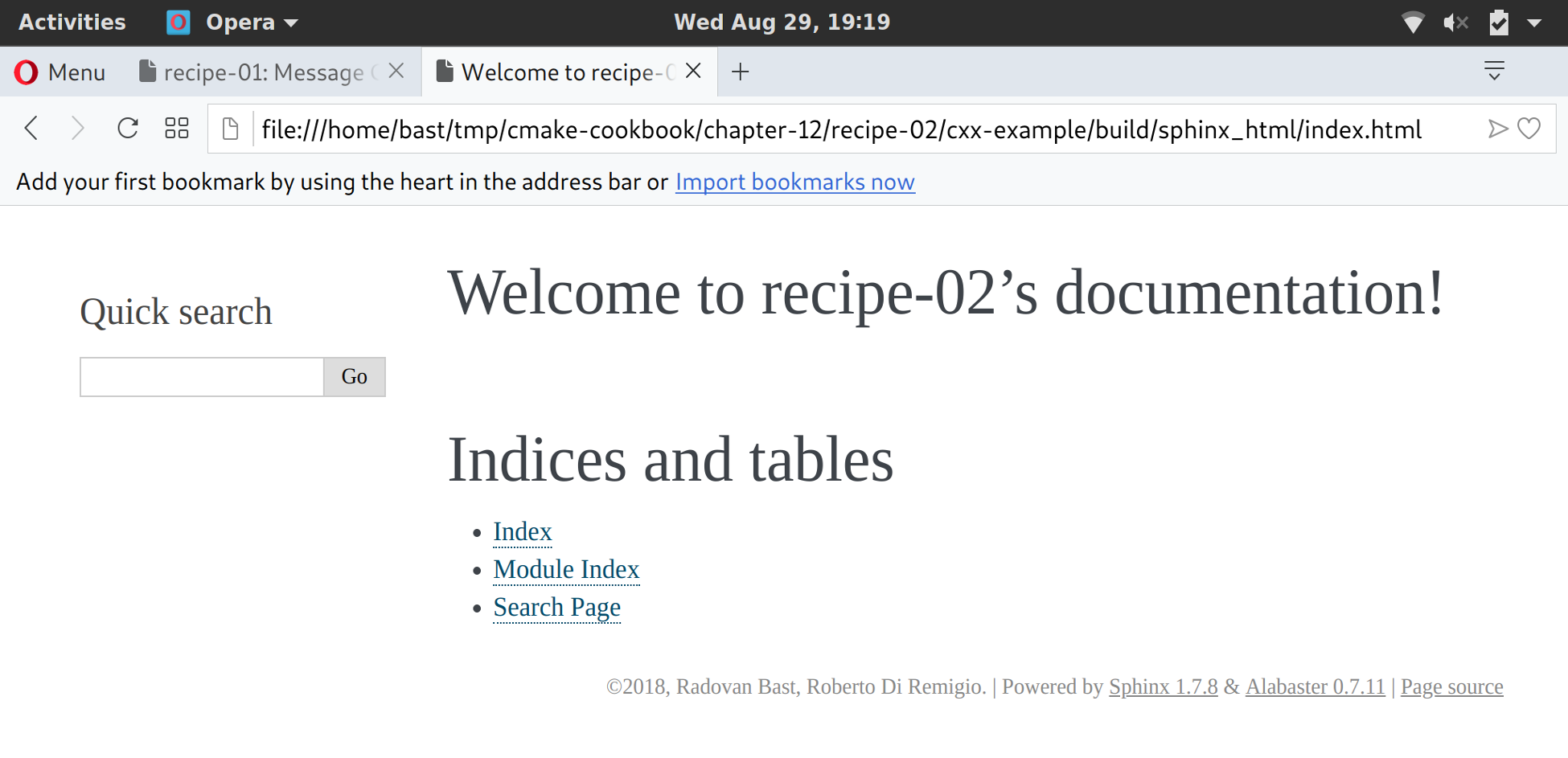

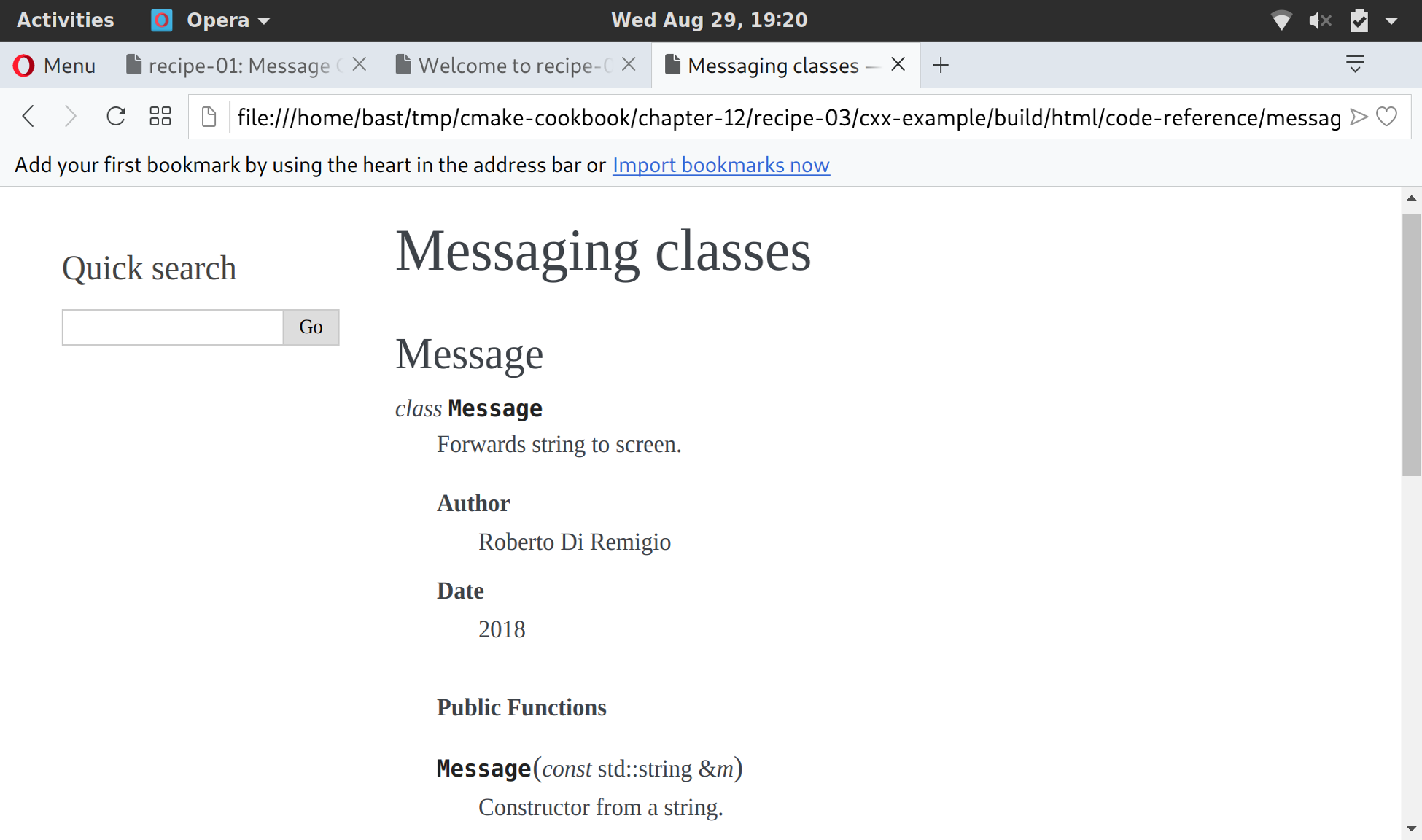

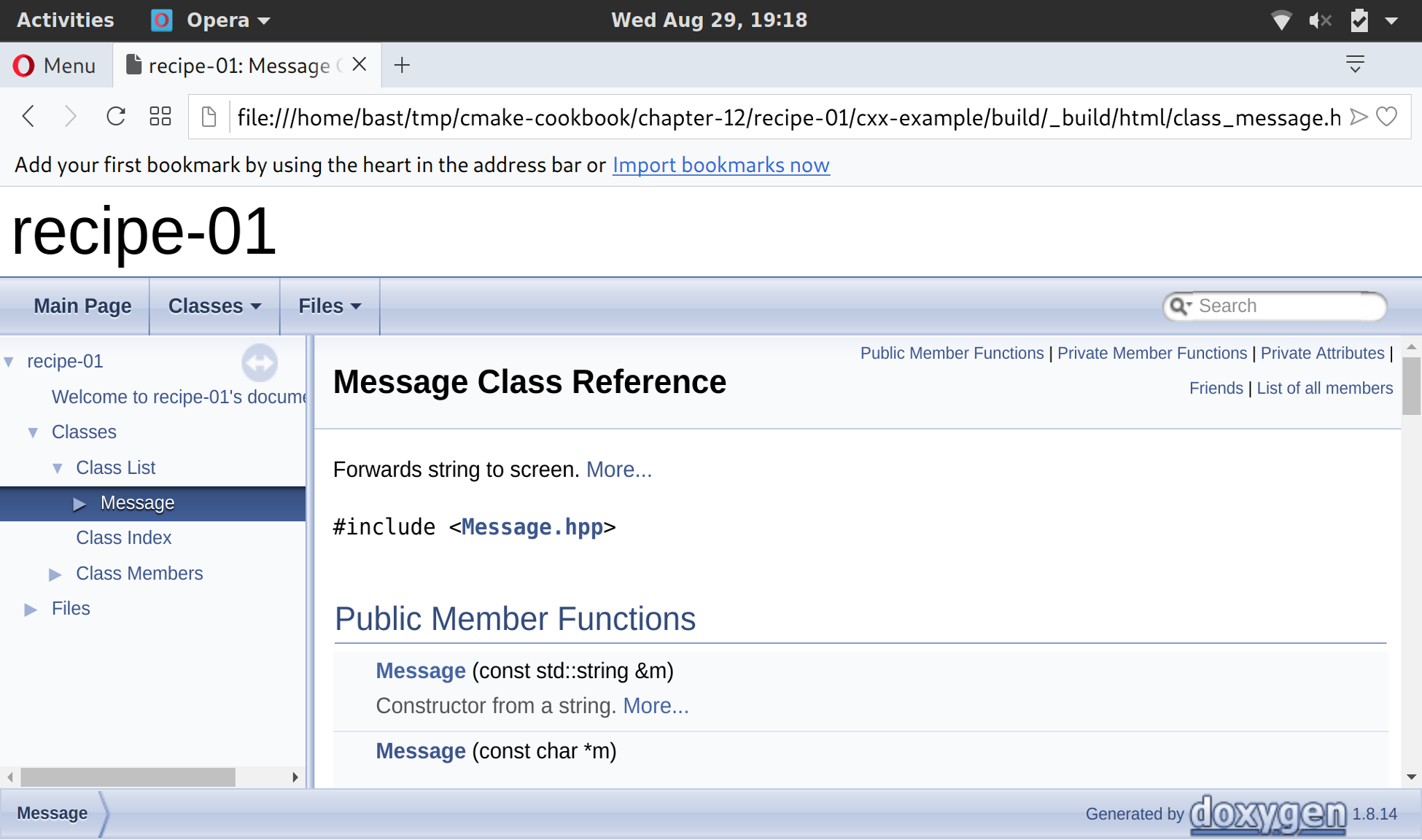

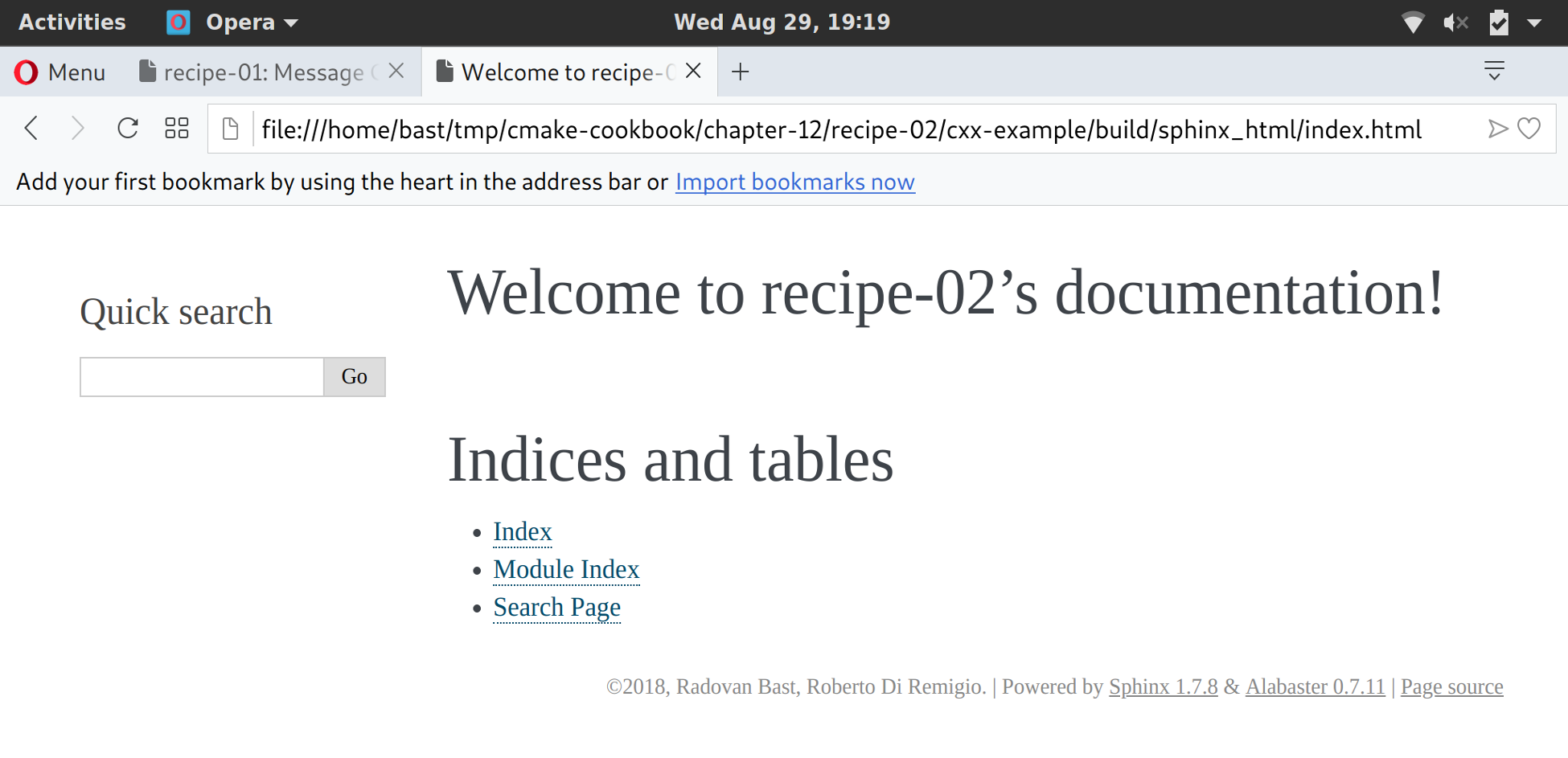

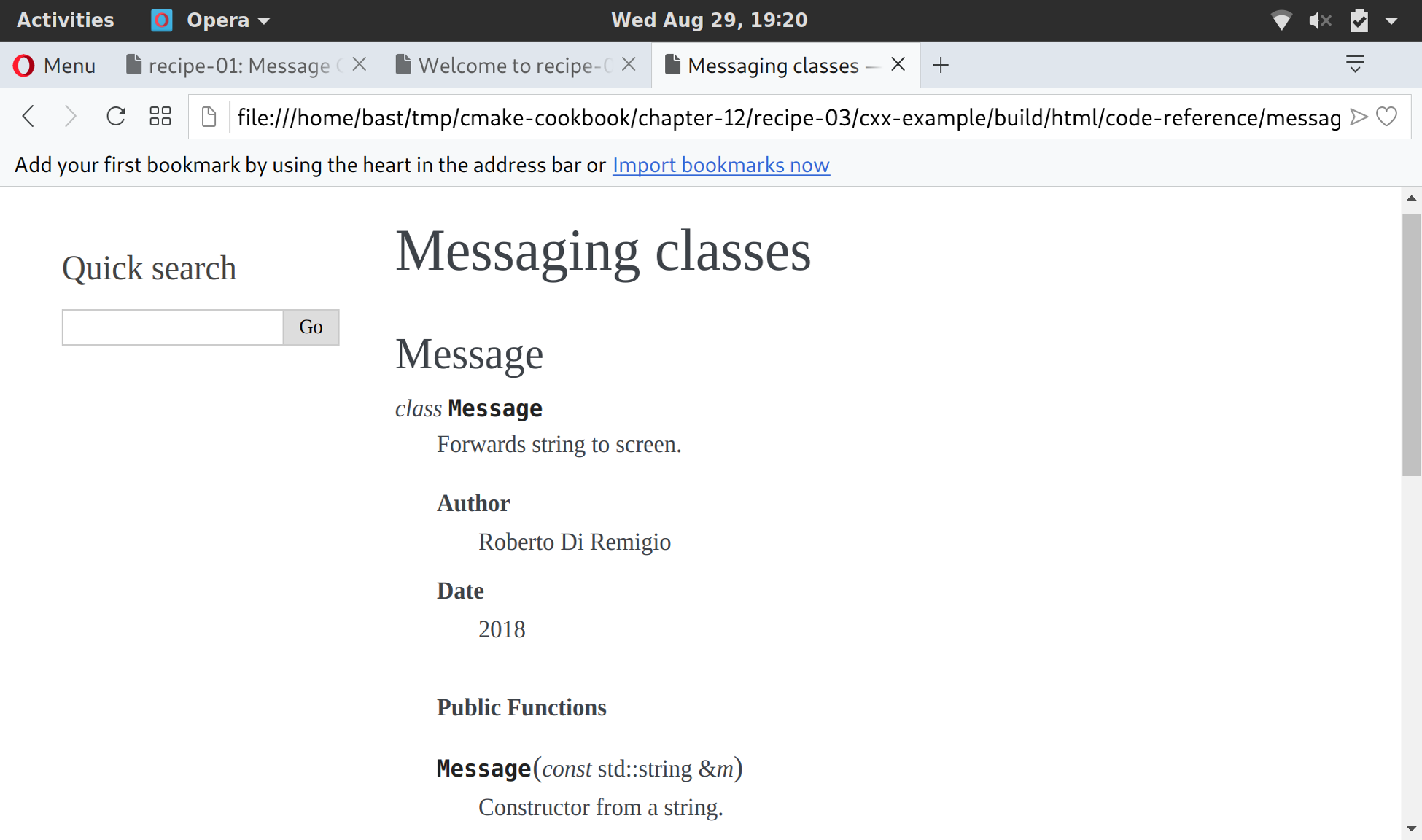

Chapter 12, Building Documentation, shows how to use CMake to also build the documentation for your code.

Chapter 13, Alternative Generators and Cross-compilation, shows how to use CMake to cross-compile projects between platforms.

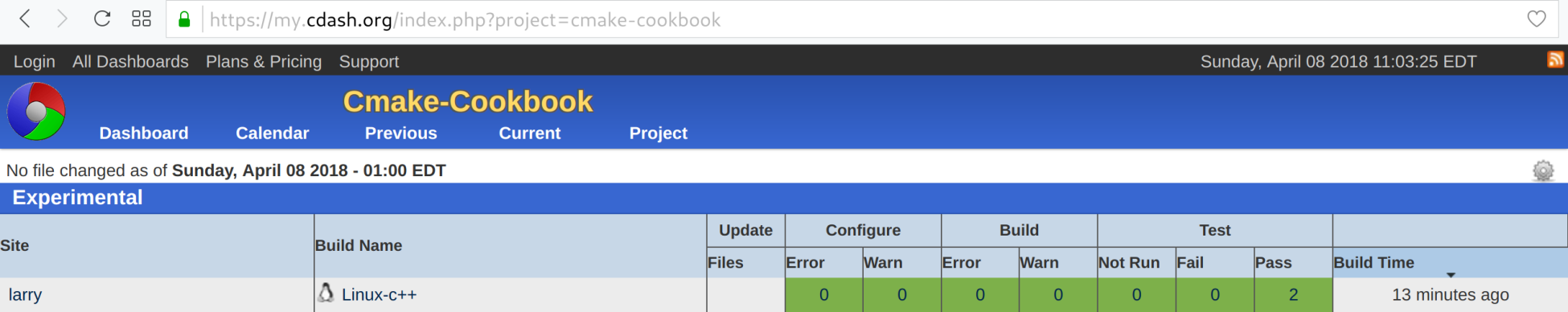

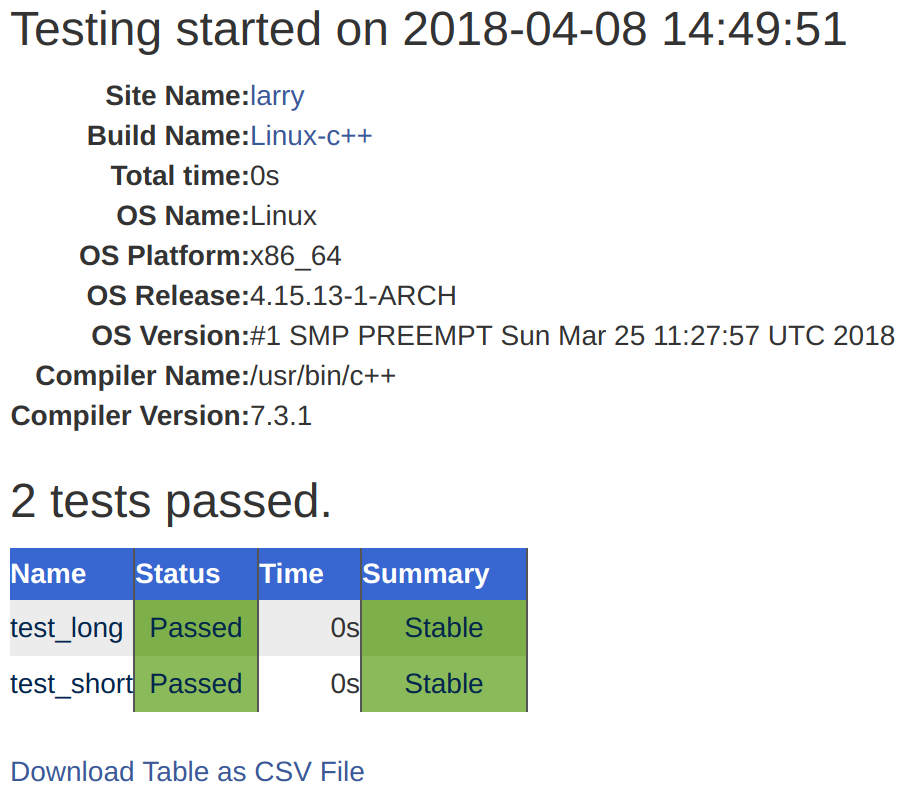

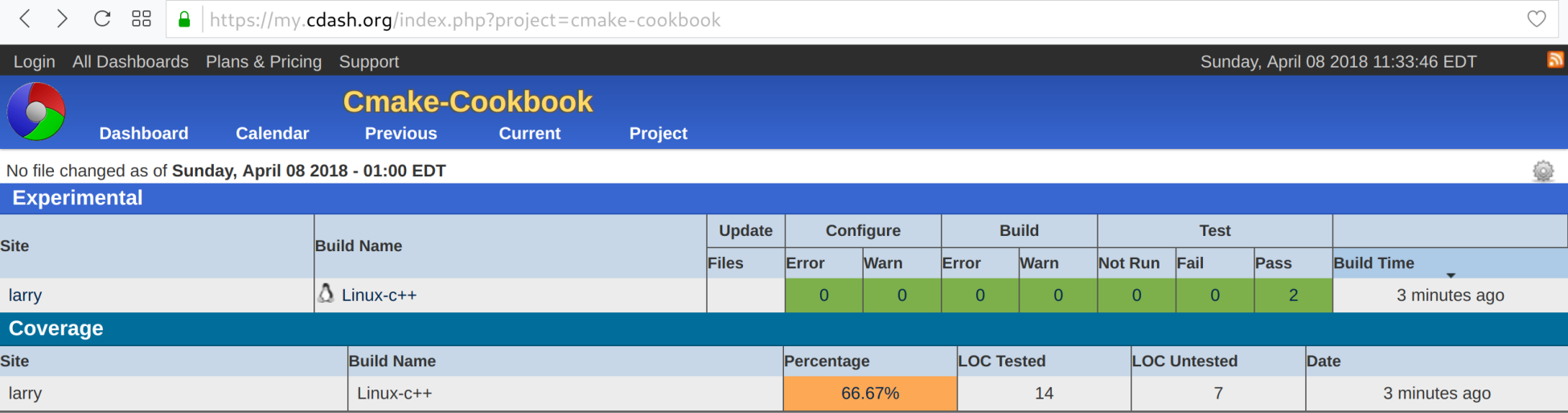

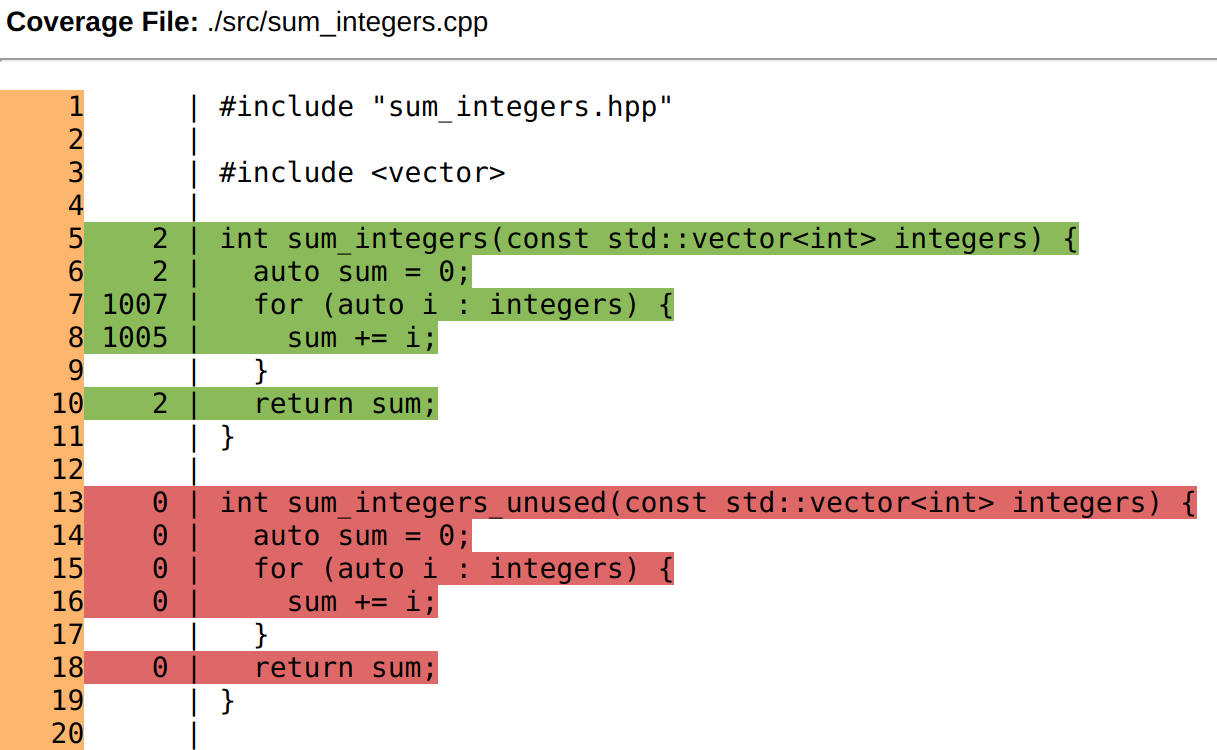

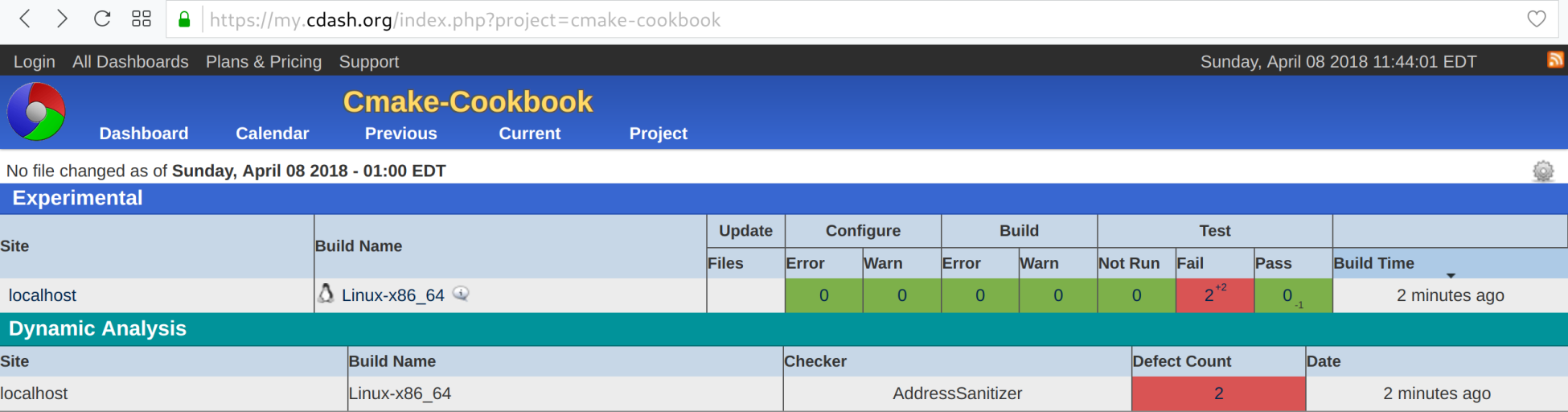

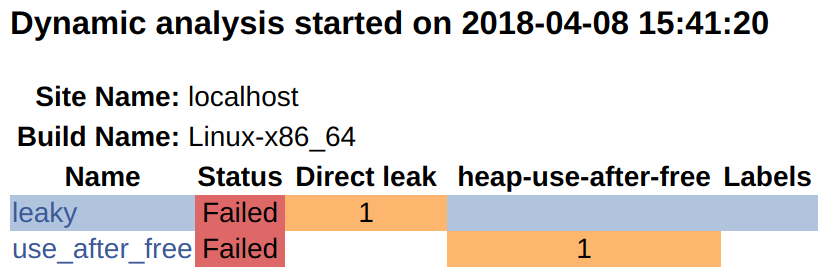

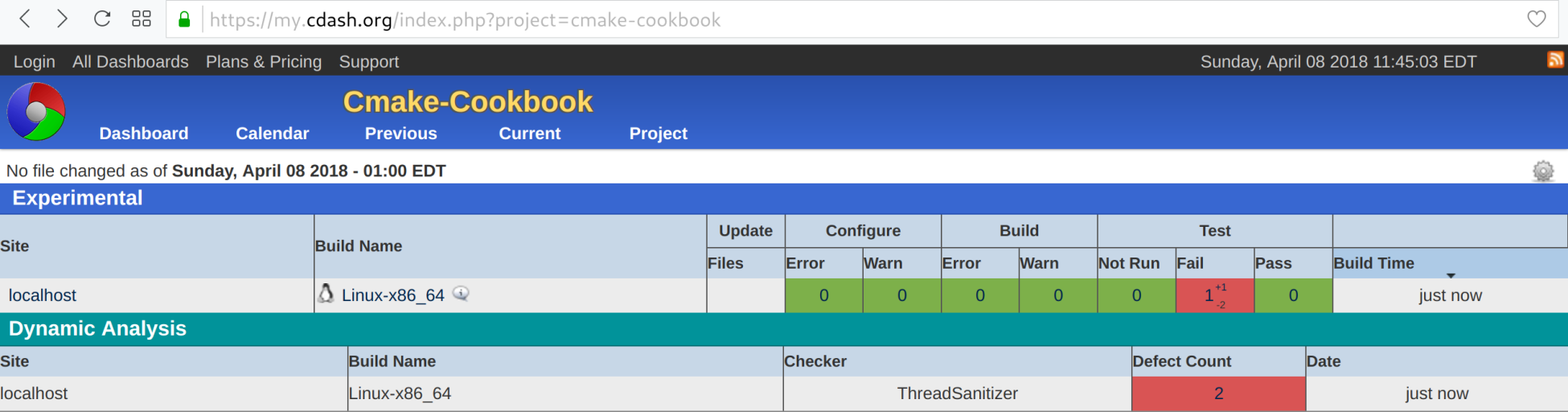

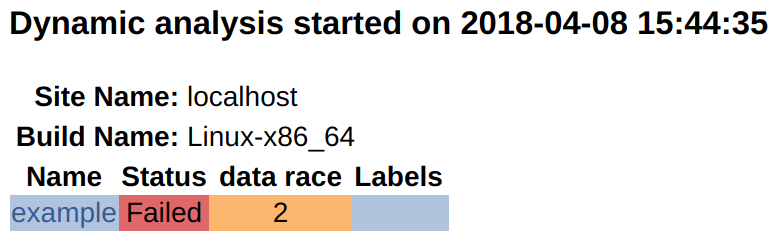

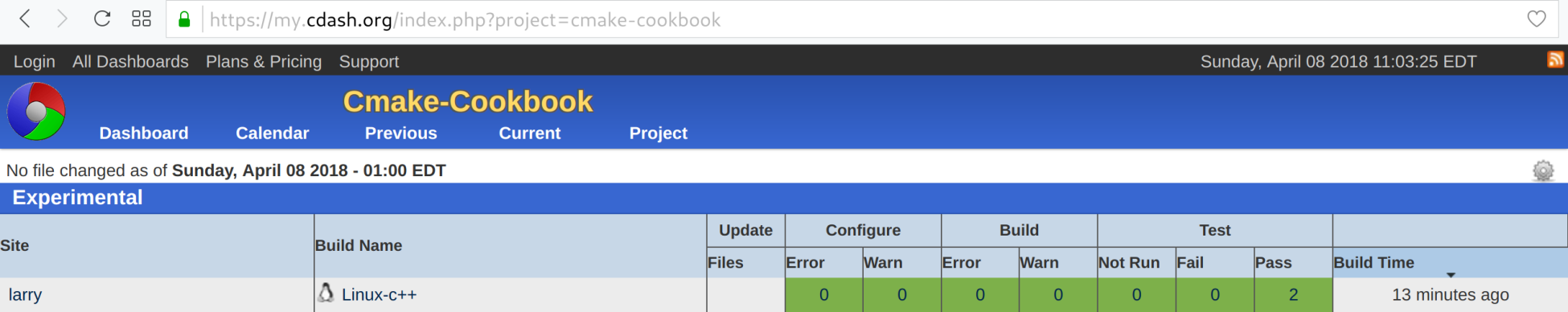

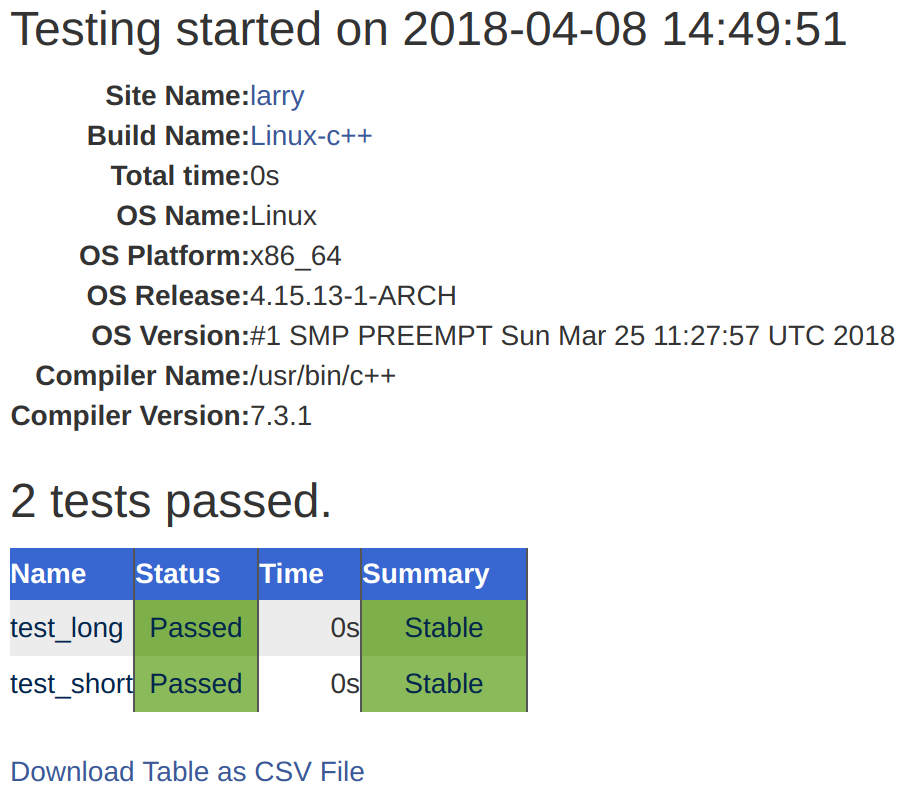

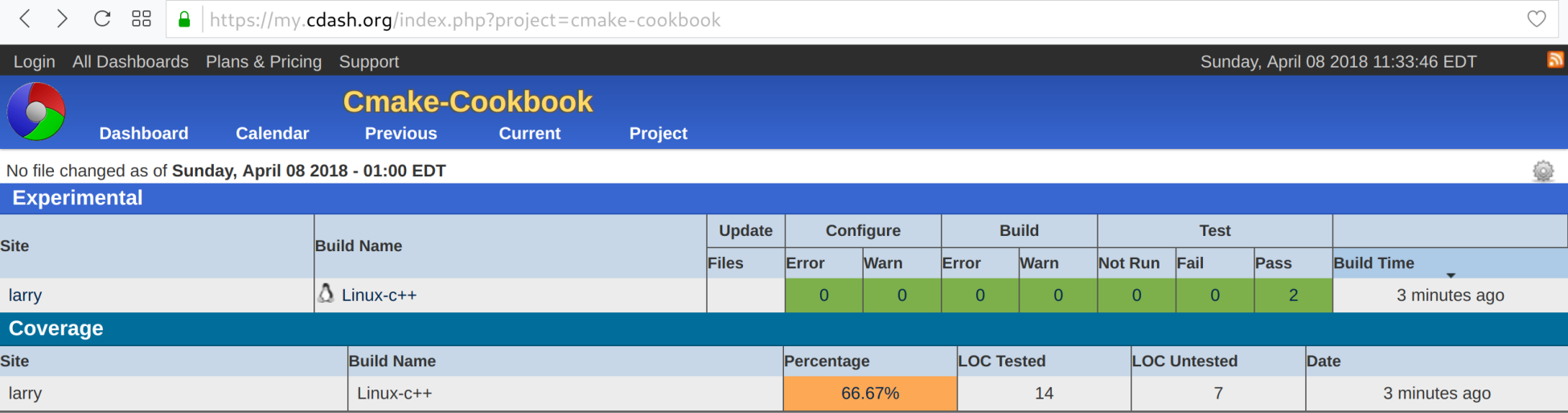

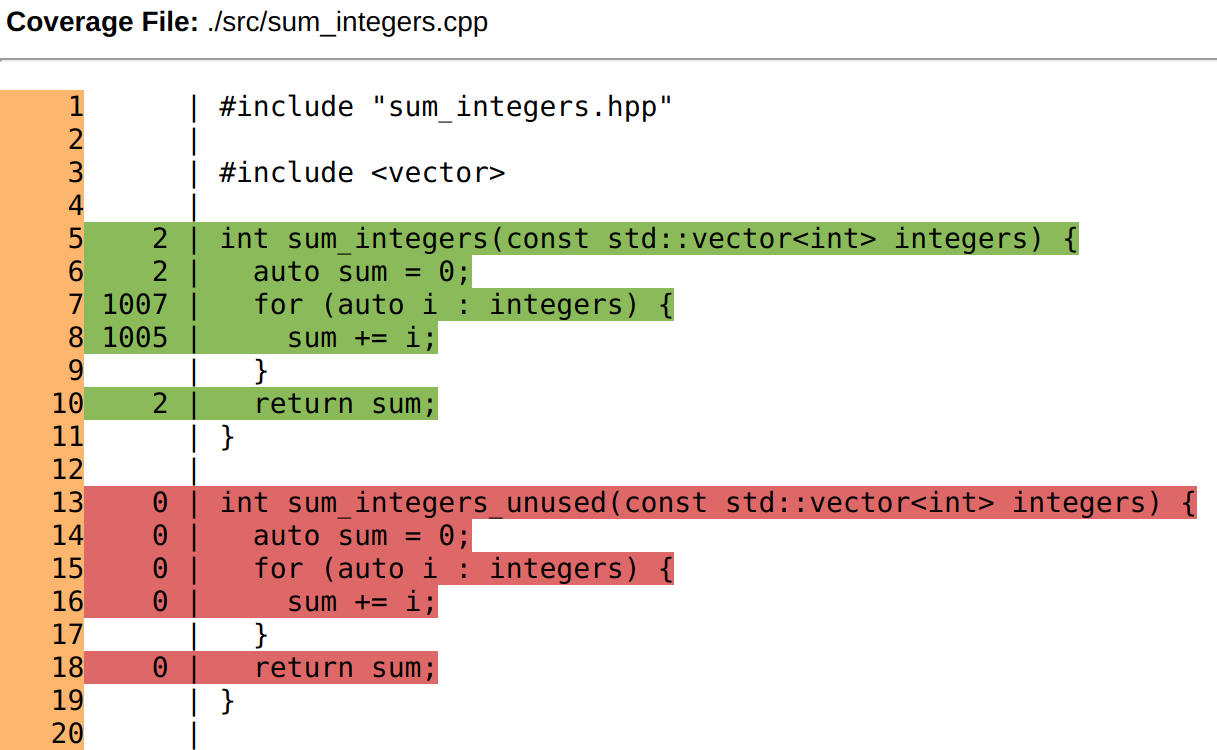

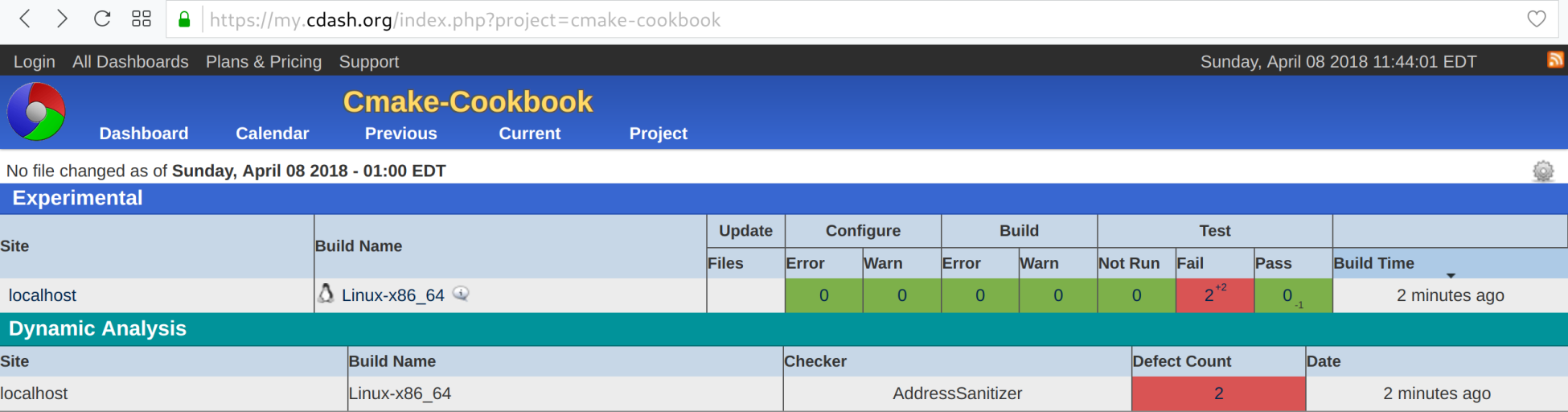

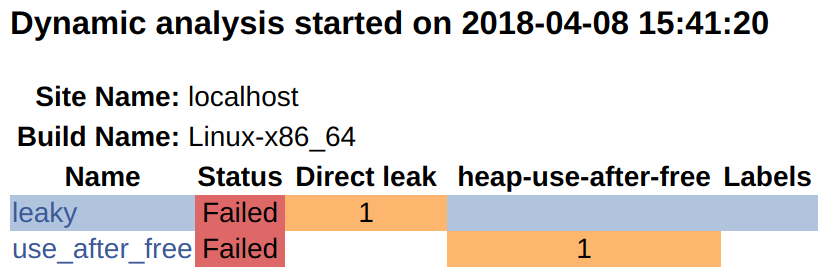

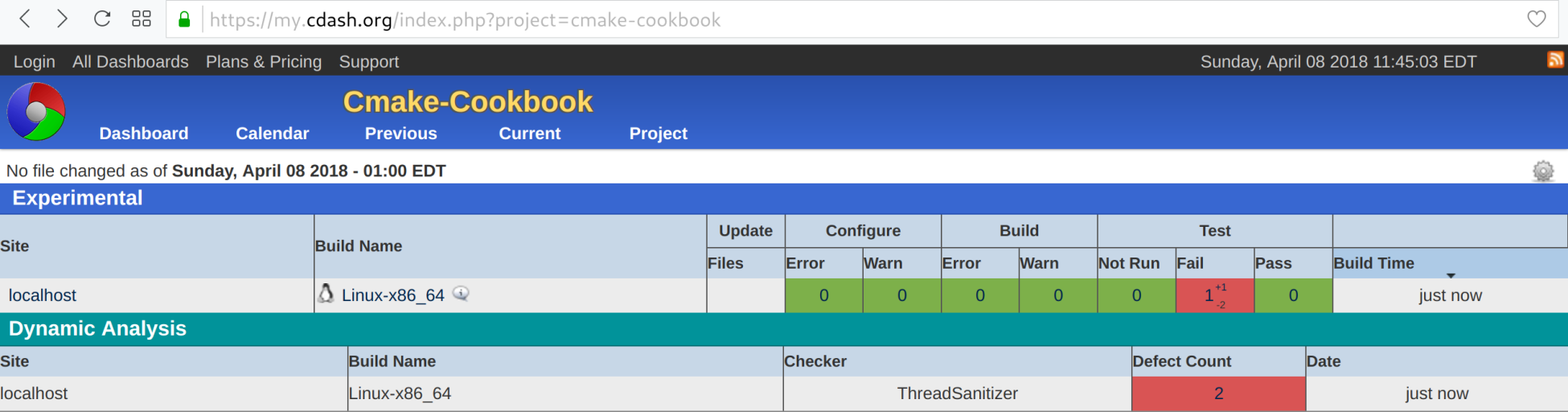

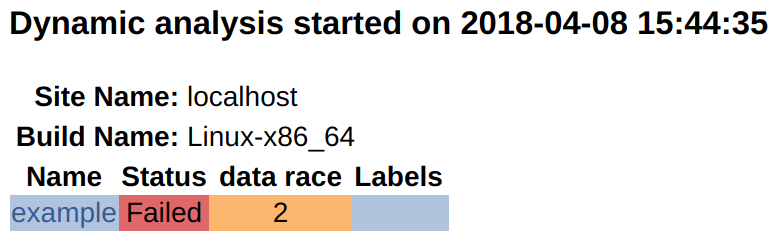

Chapter 14, Testing Dashboards, shows how to report the results of tests to an online dashboard.

Chapter 15, Porting a Project to CMake, shows best practices, tips, and tricks that will help you port a project to a CMake-based build system.

This is a book written by programmers, for programmers. We have assumed basic knowledge and familiarity with the following:

You can download the example code examples for this book from https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook. For more details please see the Setting up Your System section.

We also provide a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. You can download it here: http://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/CMakeCookbook_ColorImages.pdf.

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code commands in text, folder names, filenames, module names, and target names.

A block of code is set as follows:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.5 FATAL_ERROR)

project(recipe-01 LANGUAGES CXX)

add_executable(hello-world hello-world.cpp)

Any command-line input is written in bold and contains a $ prompt in front of the command to type:

$ mkdir -p build

$ cd build

$ cmake ..

To distinguish command-line input and output, we keep output non-bold:

$ ./hello-world

Hello World!

The documentation for CMake available online is comprehensive and we will refer to it throughout the book: https://cmake.org/documentation/

In preparing this book we have been inspired also by other resources:

We can also recommend to browse the curated list of CMake resources, scripts, modules, and examples collected by Viktor Kirilov: https://github.com/onqtam/awesome-cmake.

It is also worth noting that our book is not the only one out there covering CMake:

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

Source code improvements and issues: Please direct pull requests towards https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook and report specific issues with recipes via https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook/issues.

General feedback: Email feedback@packtpub.com and mention the book title in the subject of your message. If you have questions about any aspect of this book, please email us at questions@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this book, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packtpub.com.

Before diving into CMake and the recipes in this book, you will need to set your system up to successfully run all of the examples. In this section, we will discuss the following topics:

We have strived to make our discussions of the topics in this book as accessible to novices as possible. However, this book does not start from absolute scratch. We assume that you have basic knowledge of the native tools for building software that are available on your platform of choice. It is also helpful (but not required) to have basic experience with version control using Git, to interact with the repository holding the recipe sources.

The source code for the recipes in this book is available on GitHub, at https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook. The code is licensed under the standard open source MIT license: this is a permissive software license, and you can reuse and remix the code in whatever way you see fit, as long as the original copyright and license notice are included in any copies of the software/source. The full text of the license is available at https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT.

In order to test the recipes by yourself, you will need a working installation of Git, obtained as follows:

Alternatively, you can access the examples with the GitHub desktop client at https://desktop.github.com.

Yet another alternative is to download and extract the ZIP file from https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook.

Once you have Git installed, you can clone the repository to your local machine, as follows:

$ git clone https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook.git

This will create a folder named cmake-cookbook. The book and the repository are organized in chapters and recipes. The numbering of chapters and the order of recipes in the repository reflect the order in the text. Each recipe is further organized into example folders. Some of the recipes have more than one example, usually when similar CMake concepts are illustrated in different programming languages.

The recipes are tested on GNU/Linux, macOS, and Windows, using state-of-the-art continuous integration services. We will discuss the testing set up shortly.

We have tagged the precise versions that correspond to the examples printed in this book with the tag v1.0. For maximum overlap with the book text, you can fetch this particular version as follows:

$ git clone --single-branch -b v1.0 https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook.git

We expect to receive bug fixes and the GitHub repository to evolve. To get the latest updates, you may prefer to follow the master branch of the repository, instead.

You will likely find that the easiest approach to testing the book's recipes in a software environment (which contains all of the dependencies preinstalled) is to use a Docker image that we have set up, based on Ubuntu 18.04. You can install Docker on your favorite operating system, following the official documentation at https://docs.docker.com.

Once Docker is installed, you can run our image and test the recipes with the full software environment in place, as follows:

$ docker run -it devcafe/cmake-cookbook_ubuntu-18.04

$ git clone https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook.git

$ cd cmake-cookbook

$ pipenv install --three

$ pipenv run python testing/collect_tests.py 'chapter-*/recipe-*'

An alternative to running the book recipes in a container is to install the dependencies directly on the host operating system. For this, we have assembled a minimal toolstack that can be used as a basic starting point for all of our recipes. You will have to install the following:

We will also detail how to install the additional dependencies required by some of the recipes.

CMake 3.5 is the minimum required version of CMake for this book. Only a few, specific recipes and examples that demonstrate useful features that were introduced after version 3.5 will require a more recent version of CMake. The introduction to every recipe features an info box, pointing out where the code is available, which examples are given, and the minimum version of CMake required. The info boxes will look like the following box:

Some, if not most, of the recipes will still be valid with older versions of CMake. However, we have made no attempts to test this assumption, since we consider CMake 3.5 to be the default on most systems and distributions. We also consider upgrading to later versions of CMake to be a straightforward step.

CMake can be installed in a number of different ways. Downloading and extracting the binary distribution maintained by Kitware will work across all platforms. The download page is at https://cmake.org/download/.

Most GNU/Linux distributions have CMake available in their package managers. However, on some distributions, the packaged version can be rather old, so downloading the binary maintained by Kitware is still the preferred option. The following commands will download and install CMake 3.5.2 under $HOME/Deps/cmake (adjust this path to your preference), from the version packaged by CMake:

$ cmake_version="3.5.2"

$ target_path=$HOME/Deps/cmake/${cmake_version}

$ cmake_url="https://cmake.org/files/v${cmake_version%.*}/cmake-${cmake_version}-Linux-x86_64.tar.gz"

$ mkdir -p "${target_path}"

$ curl -Ls "${cmake_url}" | tar -xz -C "${target_path}" --strip-components=1

$ export PATH=$HOME/Deps/cmake/${cmake_version}/bin${PATH:+:$PATH}

$ cmake --version

Homebrew for macOS reliably ships the latest version of CMake:

$ brew upgrade cmake

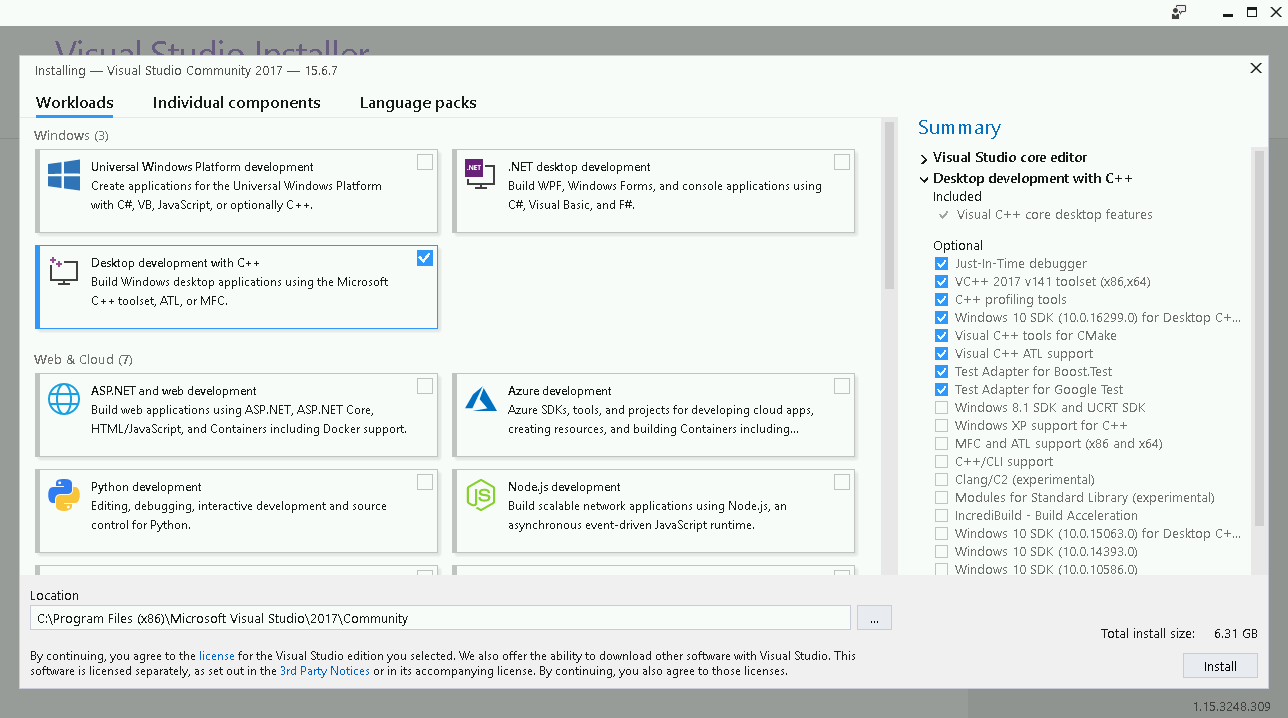

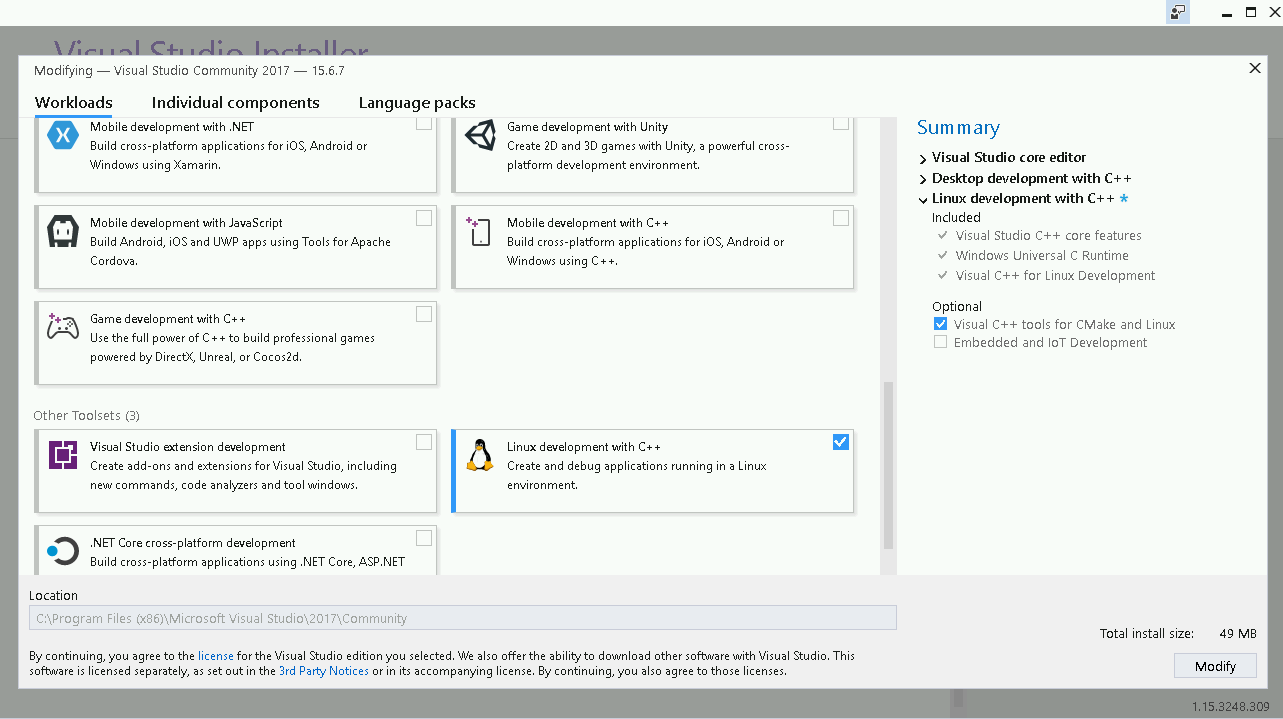

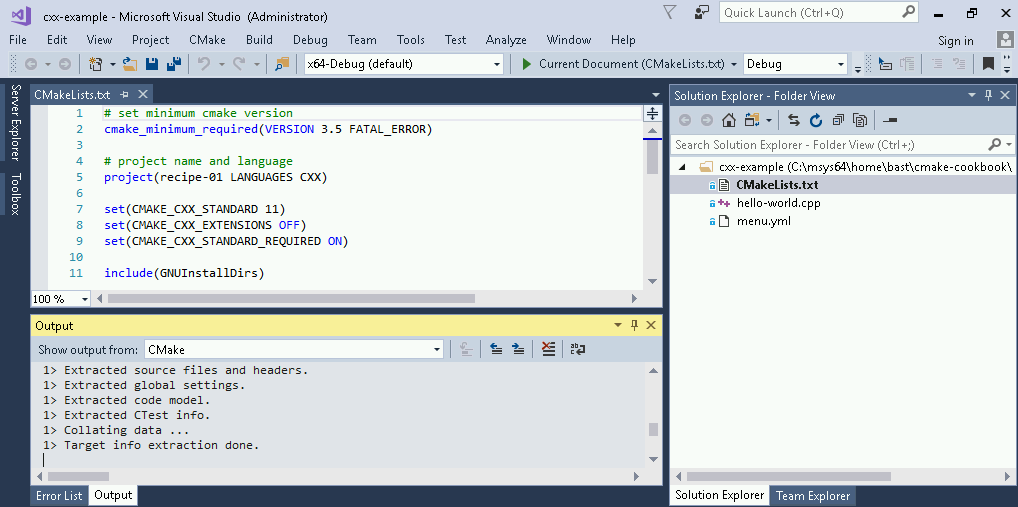

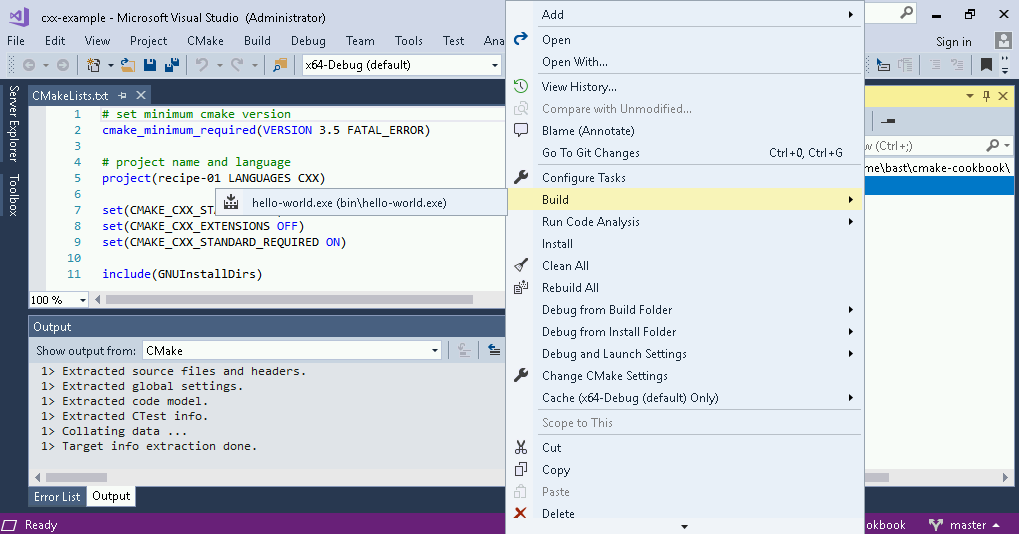

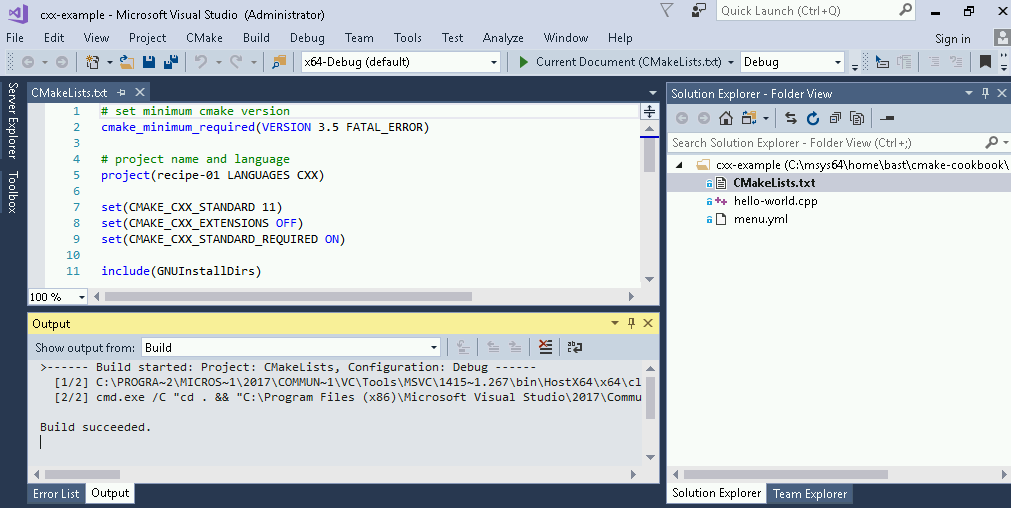

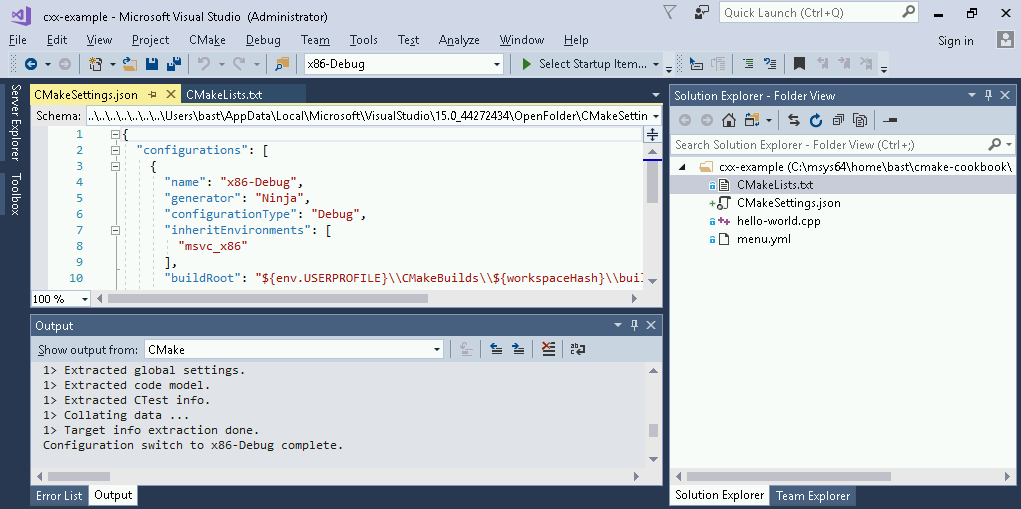

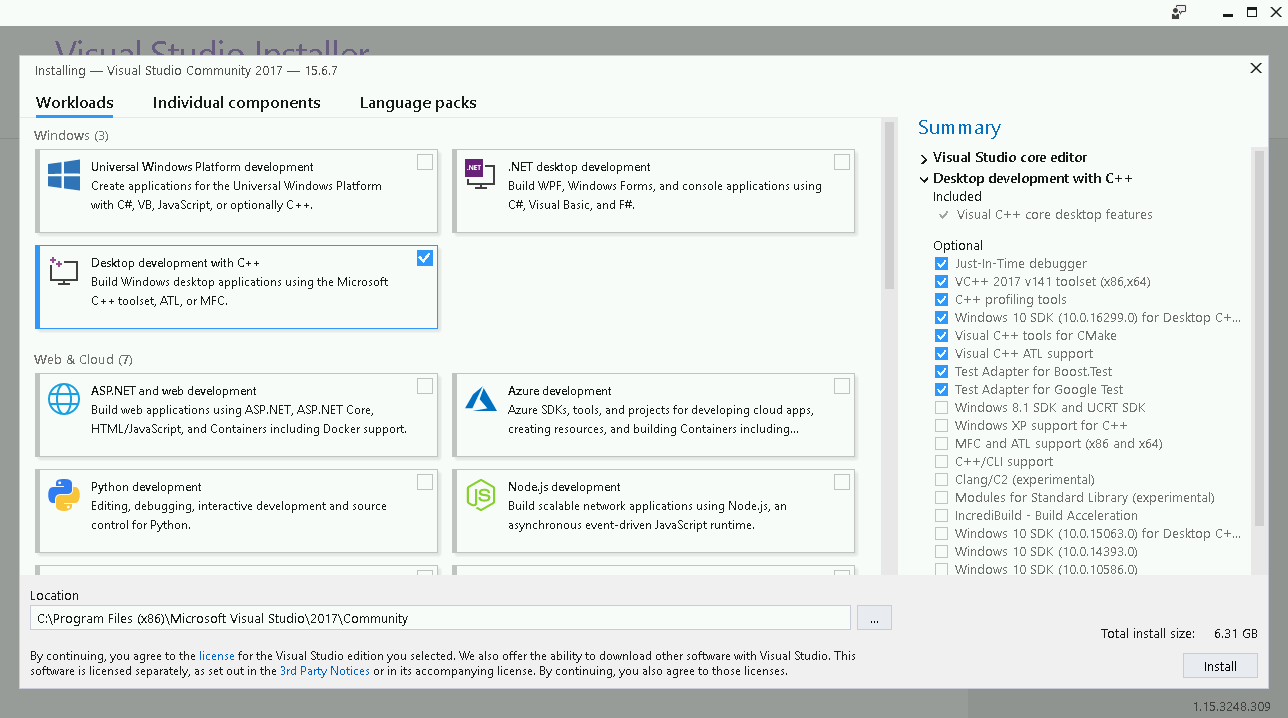

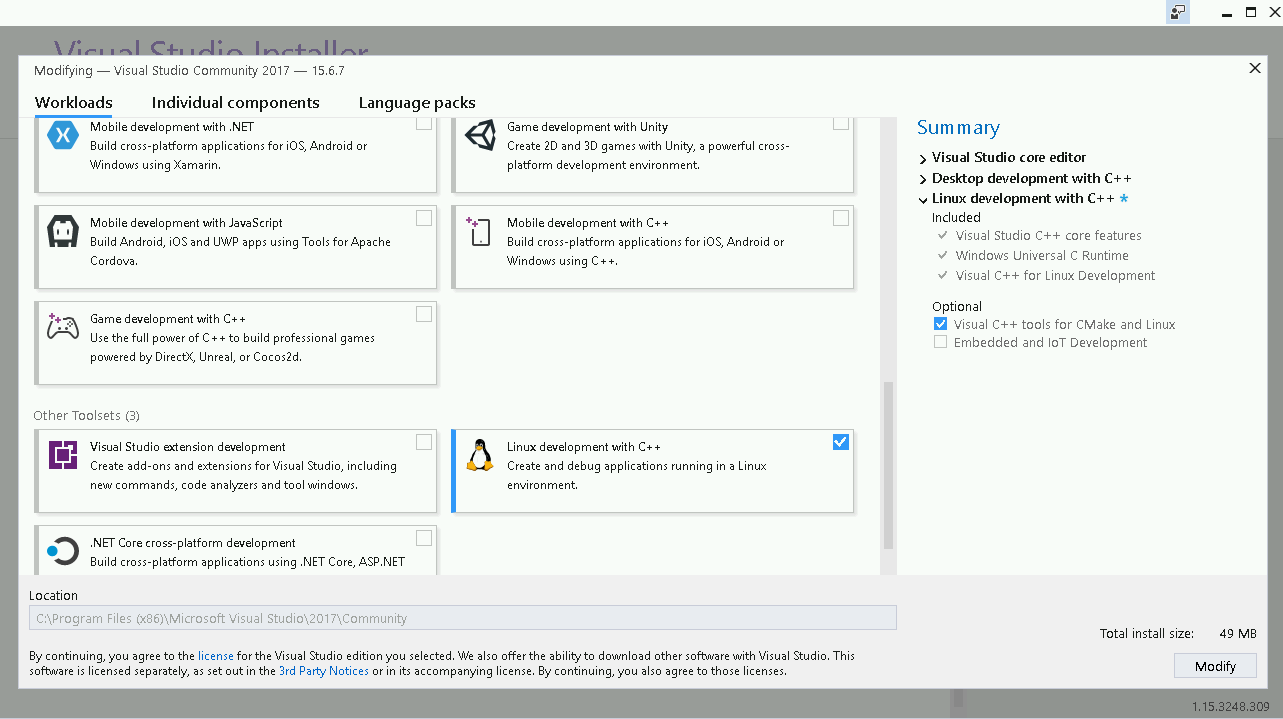

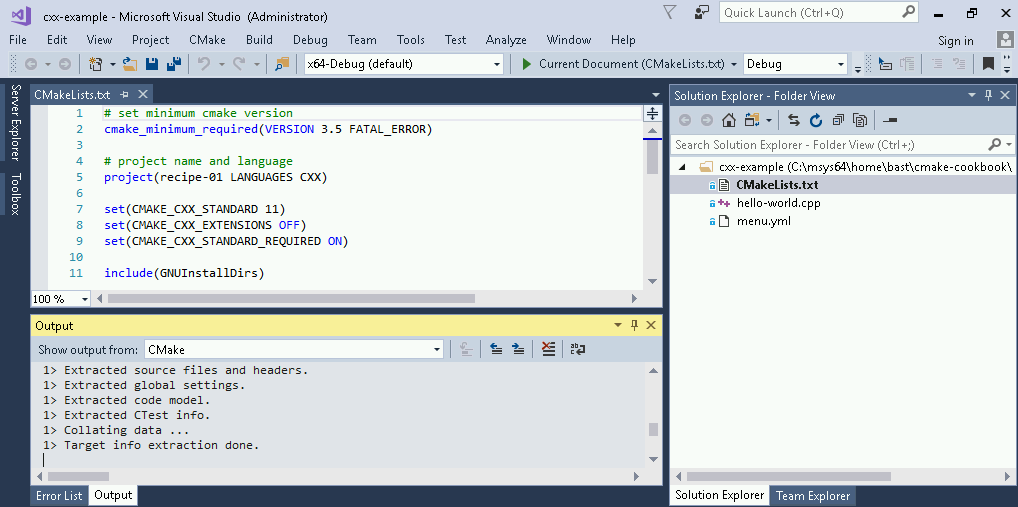

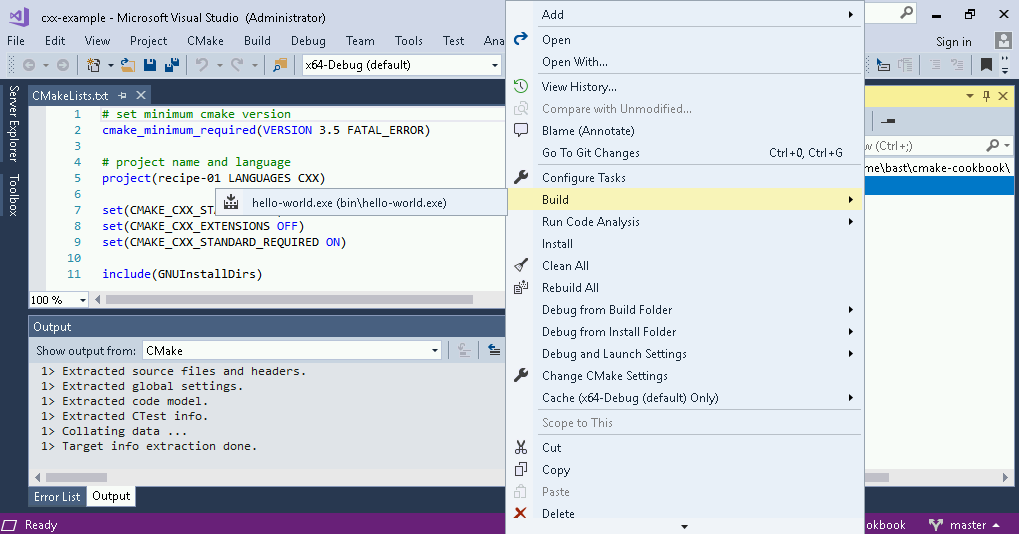

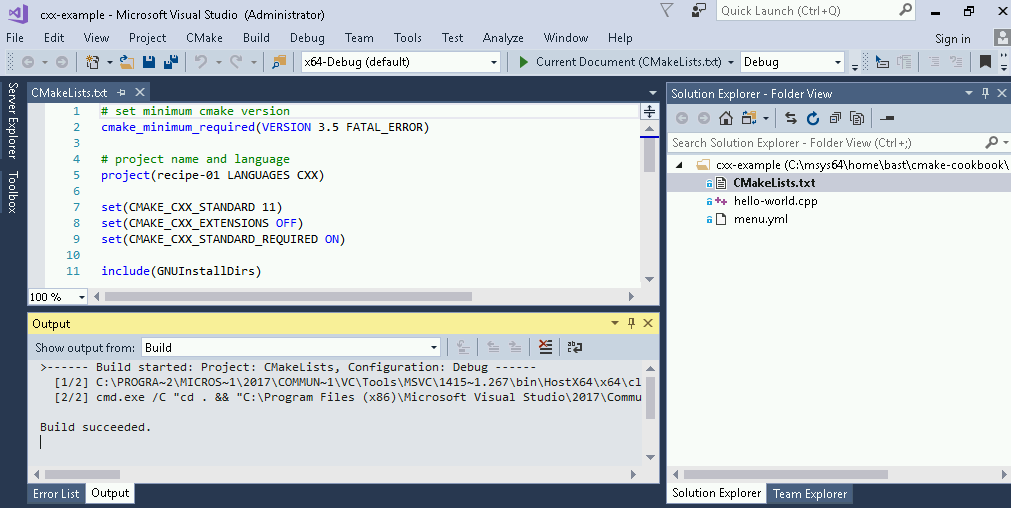

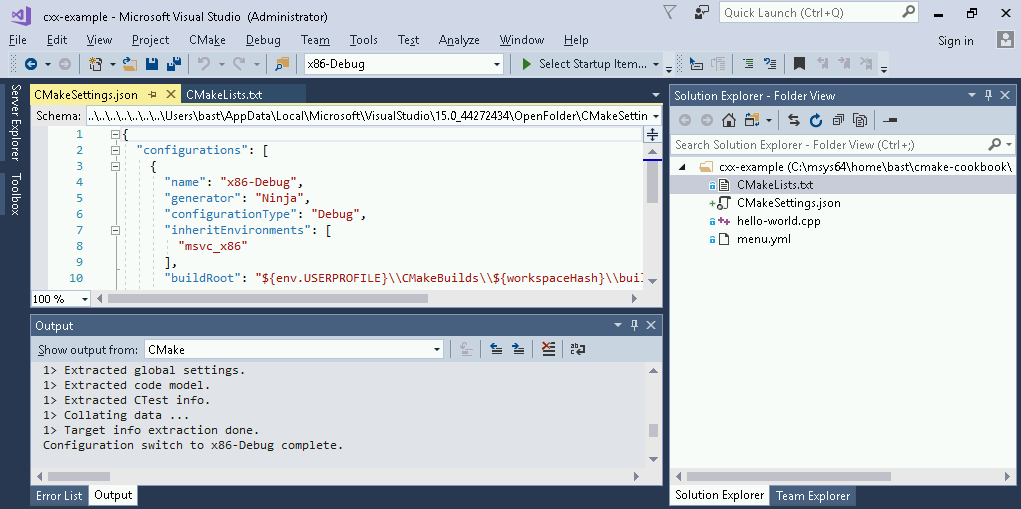

On Windows, you can use Visual Studio 2017, which provides CMake support. The installation of Visual Studio 2017 is documented in Chapter 13, Alternative Generators and Cross-compilation, Recipe 1, Building a CMake project using Visual Studio 2017.

Alternatively, you can download the MSYS2 installer from https://www.msys2.org , follow the instructions given therein to update the list of packages, and then install CMake using the package manager, pacman. The following code assumes that we are building the 64-bit version:

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-x86_64-cmake

For the 32-bit version, use the following (though we will only refer to 64-bit versions in future, for the sake of brevity):

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-i686-cmake

Another nice feature of MSYS2 is that it provides a terminal on Windows that feels and behaves like a terminal on a Unix-like operating system, providing a useful development environment.

We will need compilers for C++, C, and Fortran. These should be fairly recent, as we require support for recent language standards in most of the recipes. CMake offers very good support for many compilers, from both commercial and non-commercial vendors. To keep the recipes consistently cross-platform and as operating system independent as possible, we have worked with open source compilers:

$ sudo apt-get install g++ gcc gfortran

$ sudo apt-get install clang clang++ gfortran

$ brew install gcc

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-x86_64-toolchain

These build-automation tools will provide the infrastructure for building and linking the projects presented in the recipes. What you will end up installing and using strongly depends on your operating system and your taste:

For maximum portability, we have made the recipes as agnostic about these system-dependent details as possible. A clear advantage of this approach is that configuring, building, and linking are native to each platform and each set of compilers.

The Ninja program is a different build-automation tool that works on GNU/Linux, macOS, and Windows. Ninja is a new build tool, with a focus on speed, especially for incremental rebuilds. Prepackaged binaries for GNU/Linux, macOS, and Windows can be found on the project's GitHub repository at https://github.com/ninja-build/ninja/releases.

Using CMake and Ninja with Fortran projects requires some care. CMake 3.7.2 or later is required, along with the version of Ninja maintained by Kitware, available at https://github.com/Kitware/ninja/releases.

On GNU/Linux, you can install Ninja with the following series of commands:

$ mkdir -p ninja

$ ninja_url="https://github.com/Kitware/ninja/releases/download/v1.8.2.g3bbbe.kitware.dyndep-1.jobserver-1/ninja-1.8.2.g3bbbe.kitware.dyndep-1.jobserver-1_x86_64-linux-gnu.tar.gz"

$ curl -Ls ${ninja_url} | tar -xz -C ninja --strip-components=1

$ export PATH=$HOME/Deps/ninja${PATH:+:$PATH}

On Windows, using the MSYS2 environment (assuming the 64-bit version), executing the command:

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-x86_64-ninja

This book is about CMake, but some of the recipes, along with the whole infrastructure powering testing, need Python. Thus, first and foremost, you will need a working installation of Python: the interpreter, header files, and libraries. The end of life for Python 2.7 was announced for 2020, and we will thus use Python 3.5.

On Ubuntu 14.04 LTS (this is the environment used by Travis CI which we will discuss later on), Python 3.5 can be installed as follows:

$ sudo apt-get install python3.5-dev

On Windows, using the MSYS2 environment, the Python environment can be installed as follows (assuming the 64-bit version):

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-x86_64-python3

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-x86_64-python3-pip

$ python3 -m pip install pipenv

Specific Python modules are also required, in order to run the testing machinery that we have put in place. These can be installed system-wide by using your favorite package manager, or in an isolated environment. The latter approach is highly recommended, as it offers the following advantages:

We have prepared a Pipfile for this purpose. In combination with its Pipfile.lock, you can use Pipenv (http://pipenv.readthedocs.io) to generate an isolated environment, with all packages installed. To create this environment for the recipe example repository, run the following commands in the top-level directory of the repository:

$ pip install --user pip pipenv --upgrade

$ pipenv install --python python3.5

The pipenv shell command will drop you into a command-line environment with the specific version of Python and all of the packages available. Executing exit will bring you back to a clean environment. You can also use pipenv run to directly execute a command within the isolated environment.

Alternatively, the requirements.txt file in the repository can be used, in combination with Virtualenv (http://docs.python-guide.org/en/latest/dev/virtualenvs/) and pip, to achieve the same effect:

$ virtualenv --python=python3.5 venv

$ source venv/bin/activate

$ pip install -r requirements.txt

The virtual environment can be exited by using the deactivate command.

Yet another alternative is to use Conda environments. To do so, we suggest installing Miniconda. The following instructions will install the latest Miniconda to the directory $HOME/Deps/conda, for GNU/Linux (download from https://repo.continuum.io/miniconda/Miniconda3-latest-Linux-x86_64.sh) or macOS (download from https://repo.continuum.io/miniconda/Miniconda3-latest-MacOSX-x86_64.sh):

$ curl -Ls https://repo.continuum.io/miniconda/Miniconda3-latest-Linux-x86_64.sh > miniconda.sh

$ bash miniconda.sh -b -p "$HOME"/Deps/conda &> /dev/null

$ touch "$HOME"/Deps/conda/conda-meta/pinned

$ export PATH=$HOME/Deps/conda/bin${PATH:+:$PATH}

$ conda config --set show_channel_urls True

$ conda config --set changeps1 no

$ conda update --all

$ conda clean -tipy

On Windows, you can download the latest Miniconda from https://repo.continuum.io/miniconda/Miniconda3-latest-Windows-x86_64.exe. The package can be installed using PowerShell, as follows:

$basedir = $pwd.Path + "\"

$filepath = $basedir + "Miniconda3-latest-Windows-x86_64.exe"

$Anaconda_loc = "C:\Deps\conda"

$args = "/InstallationType=JustMe /AddToPath=0 /RegisterPython=0 /S /D=$Anaconda_loc"

Start-Process -FilePath $filepath -ArgumentList $args -Wait -Passthru

$conda_path = $Anaconda_loc + "\Scripts\conda.exe"

$args = "config --set show_channel_urls True"

Start-Process -FilePath "$conda_path" -ArgumentList $args -Wait -Passthru

$args = "config --set changeps1 no"

Start-Process -FilePath "$conda_path" -ArgumentList $args -Wait -Passthru

$args = "update --all"

Start-Process -FilePath "$conda_path" -ArgumentList $args -Wait -Passthru

$args = "clean -tipy"

Start-Process -FilePath "$conda_path" -ArgumentList $args -Wait -Passthru

Once Conda is installed, the Python modules can be installed as follows:

$ conda create -n cmake-cookbook python=3.5

$ conda activate cmake-cookbook

$ conda install --file requirements.txt

Executing conda deactivate will drop you outside of the isolated environment.

Some recipes will require additional software, which will be covered in the following sections.

Most Linux distributions provide packages for BLAS and LAPACK. For example, on Ubuntu 14.04 LTS, you can run the following:

$ sudo apt-get install libatlas-dev liblapack-dev liblapacke-dev

On macOS, the Accelerate libraries, shipped with XCode, are enough for our purposes.

On Windows, using the MSYS2 environment, these libraries can be installed as follows (assuming the 64-bit version):

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-x86_64-openblas

Alternatively, you can download the reference implementation of BLAS and LAPACK from GitHub (https://github.com/Reference-LAPACK/lapack) and compile the libraries from sources. Commercial vendors might offer packages for their own implementations of the BLAS and LAPACK APIs, available as installers for your platform.

There are many commercial and non-commercial implementations of MPI. For our introductory purposes, it is enough to install any of the freely available non-commercial implementations. On Ubuntu 14.04 LTS, we recommend OpenMPI. It can be installed with the following command:

$ sudo apt-get install openmpi-bin libopenmpi-dev

For macOS, Homebrew distributes MPICH:

$ brew install mpich

It is also possible to compile OpenMPI from the sources publicly available at https://www.open-mpi.org/software/.

For Windows, the Microsoft MPI implementation can be installed via https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb524831(v=vs.85).aspx.

Some recipes will need the Eigen linear algebra template library, version 3.3 or later. If your package manager does not provide Eigen, you can install it from the online source archive (http://eigen.tuxfamily.org). For example, on GNU/Linux and macOS, you can install Eigen to the directory $HOME/Deps/eigen, as follows:

$ eigen_version="3.3.4"

$ mkdir -p eigen

$ curl -Ls http://bitbucket.org/eigen/eigen/get/${eigen_version}.tar.gz | tar -xz -C eigen --strip-components=1

$ cd eigen

$ cmake -H. -Bbuild_eigen -DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX="$HOME/Deps/eigen" &> /dev/null

$ cmake --build build_eigen -- install &> /dev/null

Boost packages are available for every operating system; most Linux distributions have packages available through their package managers. On Ubuntu 14.04 LTS, for instance, the Boost Filesystem, Boost Python, and Boost Test libraries can be installed with the following command:

$ sudo apt-get install libboost-filesystem-dev libboost-python-dev libboost-test-dev

For macOS, both MacPorts and Homebrew provide packages for recent versions of Boost. Our testing setup on macOS installs Boost as follows:

$ brew cask uninstall --force oclint

$ brew uninstall --force --ignore-dependencies boost

$ brew install boost

$ brew install boost-python3

Prebuilt binary distributions for Windows are also available for download from the Boost website at http://www.boost.org. Alternatively, you can download the sources from https://www.boost.org and compile the libraries yourself.

On Debian/Ubuntu-like systems, cross-compilers can be installed with the following command:

$ sudo apt-get install gcc-mingw-w64 g++-mingw-w64 gfortran-mingw-w64

On macOS, using Brew, the cross-compilers can be installed as follows:

$ brew install mingw-w64

Other package managers offer corresponding packages.

An alternative to using packaged cross-compilers is to build them from sources, using the M cross environment (https://mxe.cc).

On Ubuntu 14.04 LTS, these packages can be installed as follows:

$ sudo apt-get install pkg-config libzmq3-dev doxygen graphviz-dev uuid-dev

On macOS, we recommend installing with Brew:

$ brew install ossp-uuid pkg-config zeromq doxygen

The pkg-config program and UUID library are only available on Unix-like systems.

On Windows, using the MSYS2 environment, these dependencies can be installed as follows (assuming the 64-bit version):

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-x86_64-zeromq

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-x86_64-pkg-config

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-x86_64-doxygen

$ pacman -S mingw64/mingw-w64-x86_64-graphviz

The recipes exploring packaging with Conda will need Miniconda and the Conda build and deployment tools installed on the system. The instructions for the installation of Miniconda were given previously. To install Conda build and deployment tools on GNU/Linux and macOS, run the following commands:

$ conda install --yes --quiet conda-build anaconda-client jinja2 setuptools

$ conda clean -tipsy

$ conda info -a

These tools can be installed on Windows as follows:

$conda_path = "C:\Deps\conda\Scripts\conda.exe"

$args = "install --yes --quiet conda-build anaconda-client jinja2 setuptools"

Start-Process -FilePath "$conda_path" -ArgumentList $args -Wait -Passthru

$args = "clean -tipsy"

Start-Process -FilePath "$conda_path" -ArgumentList $args -Wait -Passthru

$args = "info -a"

Start-Process -FilePath "$conda_path" -ArgumentList $args -Wait -Passthru

The recipes are tested on state-of-the-art continuous integration (CI) services: Travis (https://travis-ci.org) for GNU/Linux and macOS, Appveyor (https://www.appveyor.com) for Windows, and CircleCI (https://circleci.com) for additional GNU/Linux testing with commercial compilers. The configuration files for the CI services can be found in the repository (https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook/): .travis.yml for Travis, .appveyor.yml for Appveyor, and .circleci/config.yml for CircleCI. Additional installation scripts for Travis and Appveyor can be found in the folder testing/dependencies.

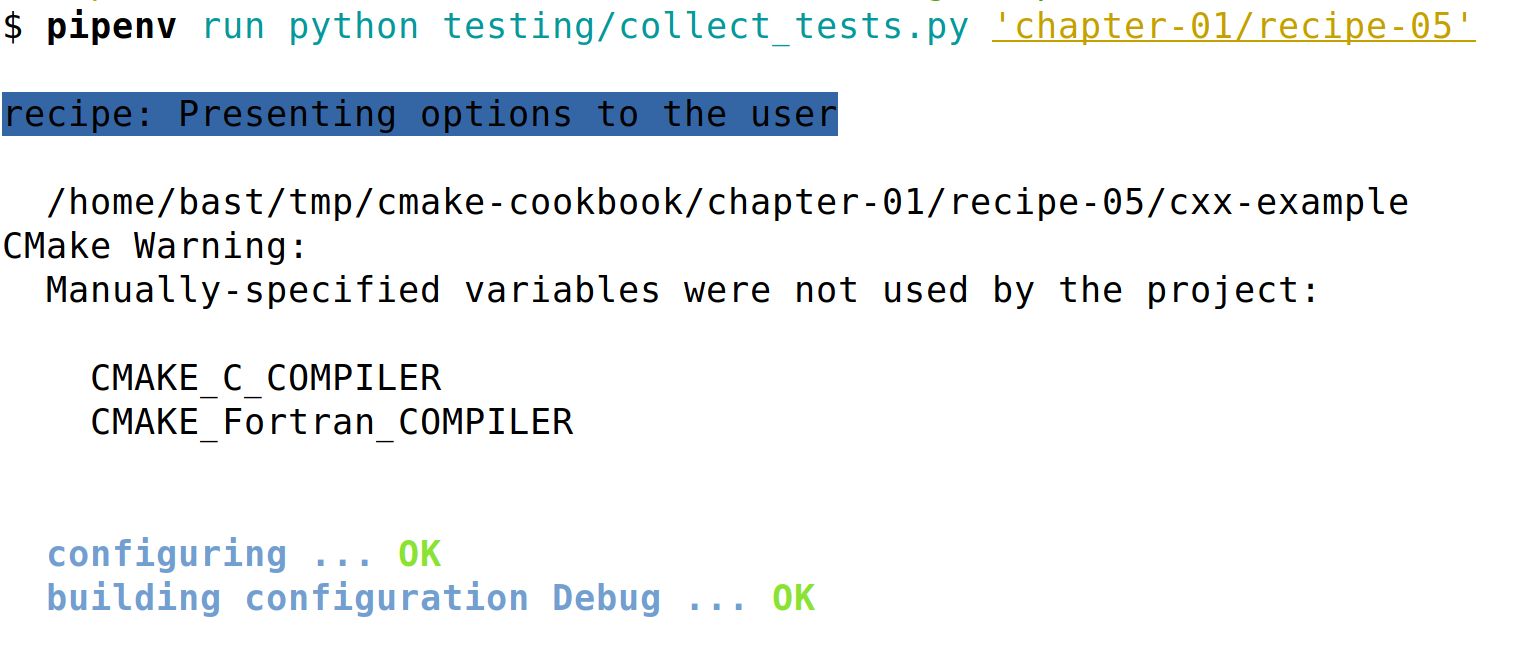

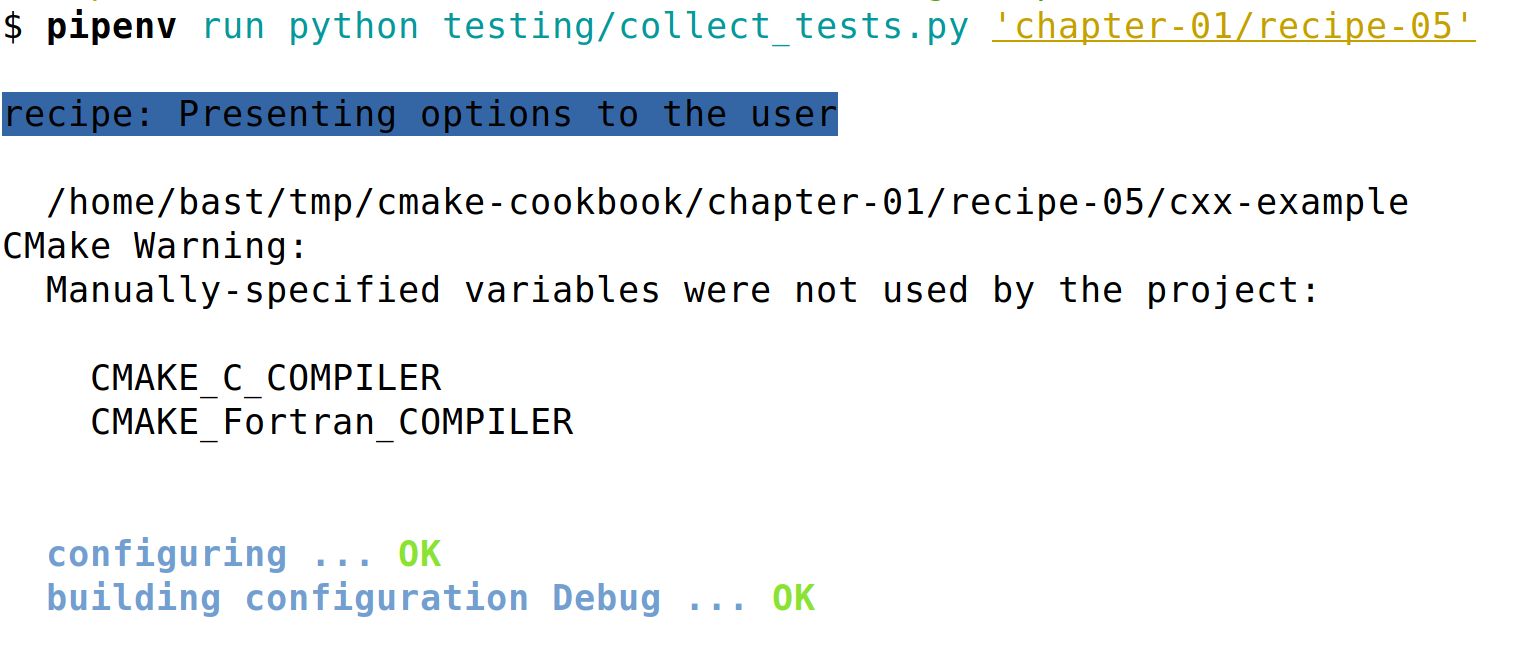

The testing machinery is a set of Python scripts that are also contained in the testing folder. The script collect_tests.py will run tests and report their statuses. Recipes can be tested in isolation, or in batches; collect_tests.py accepts a regular expression as command-line input, for example:

$ pipenv run python testing/collect_tests.py 'chapter-0[1,7]/recipe-0[1,2,5]'

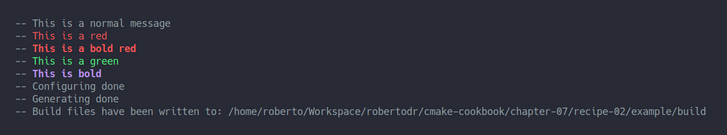

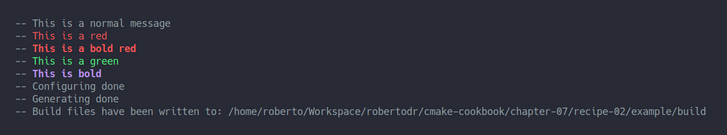

This command will run tests for Recipes 1, 2, and 5, in Chapters 1 and 7. A sample of the output looks as follows:

To get more verbose output, set VERBOSE_OUTPUT=ON:

$ env VERBOSE_OUTPUT=ON pipenv run python testing/collect_tests.py 'chapter-*/recipe-*'

Please report issues at https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook/issues.

To contribute changes,we recommend forking the repository https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook and submitting changes using pull requests, following https://help.github.com/articles/creating-a-pull-request-from-a-fork/.

For non-trivial changes, we recommend to first describe and discuss the proposed change by opening an issue on https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook/issues before sending a pull request.

In this chapter, we will cover the following recipes:

The recipes in this chapter will walk you through fairly basic tasks needed to build your code: compiling an executable, compiling a library, performing build actions based on user input, and so forth. CMake is a build system generator particularly suited to being platform- and compiler-independent. We have striven to show this aspect in this chapter. Unless stated otherwise, all recipes are independent of the operating system; they can be run without modifications on GNU/Linux, macOS, and Windows.

The recipes in this book are mainly designed for C++ projects and demonstrated using C++ examples, but CMake can be used for projects in other languages, including C and Fortran. For any given recipe and whenever it makes sense, we have tried to include examples in C++, C, and Fortran. In this way, you will be able to choose the recipe in your favorite flavor. Some recipes are tailor-made to highlight challenges to overcome when a specific language is chosen.

In this recipe, we will demonstrate how to run CMake to configure and build a simple project. The project consists of a single source file for a single executable. We will discuss the project in C++, but examples for C and Fortran are available in the GitHub repository.

We wish to compile the following source code into a single executable:

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

std::string say_hello() { return std::string("Hello, CMake world!"); }

int main() {

std::cout << say_hello() << std::endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

Alongside the source file, we need to provide CMake with a description of the operations to perform to configure the project for the build tools. The description is done in the CMake language, whose comprehensive documentation can be found online at https://cmake.org/cmake/help/latest/. We will place the CMake instructions into a file called CMakeLists.txt.

In detail, these are the steps to follow:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.5 FATAL_ERROR)

project(recipe-01 LANGUAGES CXX)

add_executable(hello-world hello-world.cpp)

$ mkdir -p build

$ cd build

$ cmake ..

-- The CXX compiler identification is GNU 8.1.0

-- Check for working CXX compiler: /usr/bin/c++

-- Check for working CXX compiler: /usr/bin/c++ -- works

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info - done

-- Detecting CXX compile features

-- Detecting CXX compile features - done

-- Configuring done

-- Generating done

-- Build files have been written to: /home/user/cmake-cookbook/chapter-01/recipe-01/cxx-example/build

$ cmake --build .

Scanning dependencies of target hello-world

[ 50%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/hello-world.dir/hello-world.cpp.o

[100%] Linking CXX executable hello-world

[100%] Built target hello-world

In this recipe, we have used a simple CMakeLists.txt to build a "Hello world" executable:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.5 FATAL_ERROR)

project(recipe-01 LANGUAGES CXX)

add_executable(hello-world hello-world.cpp)

To configure the project and generate its build system, we have to run CMake through its command-line interface (CLI). The CMake CLI offers a number of switches, cmake --help will output to screen the full help menu listing all of the available switches. We will learn more about them throughout the book. As you will notice from the output of cmake --help, most of them will let you access the CMake manual. The typical series of commands issued for generating the build system is the following:

$ mkdir -p build

$ cd build

$ cmake ..

Here, we created a directory, build, where the build system will be generated, we entered the build directory, and invoked CMake by pointing it to the location of CMakeLists.txt (in this case located in the parent directory). It is possible to use the following invocation to achieve the same effect:

$ cmake -H. -Bbuild

This invocation is cross-platform and introduces the -H and -B CLI switches. With -H. we are instructing CMake to search for the root CMakeLists.txt file in the current directory. -Bbuild tells CMake to generate all of its files in a directory called build.

Running the cmake command outputs a series of status messages to inform you of the configuration:

$ cmake ..

-- The CXX compiler identification is GNU 8.1.0

-- Check for working CXX compiler: /usr/bin/c++

-- Check for working CXX compiler: /usr/bin/c++ -- works

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info - done

-- Detecting CXX compile features

-- Detecting CXX compile features - done

-- Configuring done

-- Generating done

-- Build files have been written to: /home/user/cmake-cookbook/chapter-01/recipe-01/cxx-example/build

CMake is a build system generator. You describe what type of operations the build system, such as Unix Makefiles, Ninja, Visual Studio, and so on, will have to run to get your code compiled. In turn, CMake generates the corresponding instructions for the chosen build system. By default, on GNU/Linux and macOS systems, CMake employs the Unix Makefiles generator. On Windows, Visual Studio is the default generator. We will take a closer look at generators in the next recipe and also revisit generators in Chapter 13, Alternative Generators and Cross-compilation.

On GNU/Linux, CMake will by default generate Unix Makefiles to build the project:

To build the example project, we ran this command:

$ cmake --build .

This command is a generic, cross-platform wrapper to the native build command for the chosen generator, make in this case. We should not forget to test our example executable:

$ ./hello-world

Hello, CMake world!

Finally, we should point out that CMake does not enforce a specific name or a specific location for the build directory. We could have placed it completely outside the project path. This would have worked equally well:

$ mkdir -p /tmp/someplace

$ cd /tmp/someplace

$ cmake /path/to/source

$ cmake --build .

The official documentation at https://cmake.org/runningcmake/ gives a concise overview on running CMake. The build system generated by CMake, the Makefile in the example given above, will contain targets and rules to build object files, executables, and libraries for the given project. The hello-world executable was our only target in the current example, but running the command:

$ cmake --build . --target help

The following are some of the valid targets for this Makefile:

... all (the default if no target is provided)

... clean

... depend

... rebuild_cache

... hello-world

... edit_cache

... hello-world.o

... hello-world.i

... hello-world.s

reveals that CMake generates more targets than those strictly needed for building the executable itself. These targets can be chosen with the cmake --build . --target <target-name> syntax and achieve the following:

For more complex projects, with a test stage and installation rules, CMake will generate additional convenience targets:

CMake is a build system generator and a single CMakeLists.txt can be used to configure projects for different toolstacks on different platforms. You describe in CMakeLists.txt the operations the build system will have to run to get your code configured and compiled. Based on these instructions, CMake will generate the corresponding instructions for the chosen build system (Unix Makefiles, Ninja, Visual Studio, and so on). We will revisit generators in Chapter 13, Alternative Generators and Cross-compilation.

CMake supports an extensive list of native build tools for different platforms. Both command-line tools, such as Unix Makefiles and Ninja, and integrated development environment (IDE) tools are supported. You can find an up-to-date list of the generators available on your platform and for your installed version of CMake by running the following:

$ cmake --help

The output of this command will list all options to the CMake command-line interface. At the bottom, you will find the list of available generators. For example, this is the output on a GNU/Linux machine with CMake 3.11.2 installed:

Generators

The following generators are available on this platform:

Unix Makefiles = Generates standard UNIX makefiles.

Ninja = Generates build.ninja files.

Watcom WMake = Generates Watcom WMake makefiles.

CodeBlocks - Ninja = Generates CodeBlocks project files.

CodeBlocks - Unix Makefiles = Generates CodeBlocks project files.

CodeLite - Ninja = Generates CodeLite project files.

CodeLite - Unix Makefiles = Generates CodeLite project files.

Sublime Text 2 - Ninja = Generates Sublime Text 2 project files.

Sublime Text 2 - Unix Makefiles = Generates Sublime Text 2 project files.

Kate - Ninja = Generates Kate project files.

Kate - Unix Makefiles = Generates Kate project files.

Eclipse CDT4 - Ninja = Generates Eclipse CDT 4.0 project files.

Eclipse CDT4 - Unix Makefiles= Generates Eclipse CDT 4.0 project files.

With this recipe, we will show how easy it is to switch generators for the same project.

We will reuse hello-world.cpp and CMakeLists.txt from the previous recipe. The only difference is in the invocation of CMake, since we will now have to pass the generator explicitly with the -G CLI switch.

$ mkdir -p build

$ cd build

$ cmake -G Ninja ..

-- The CXX compiler identification is GNU 8.1.0

-- Check for working CXX compiler: /usr/bin/c++

-- Check for working CXX compiler: /usr/bin/c++ -- works

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info - done

-- Detecting CXX compile features

-- Detecting CXX compile features - done

-- Configuring done

-- Generating done

-- Build files have been written to: /home/user/cmake-cookbook/chapter-01/recipe-02/cxx-example/build

$ cmake --build .

[2/2] Linking CXX executable hello-world

We have seen that the output of the configuration step was unchanged compared to the previous recipe. The output of the compilation step and the contents of the build directory will however be different, as every generator has its own specific set of files:

Note how cmake --build . wrapped the ninja command in a unified, cross-platform interface.

We will discuss alternative generators and cross-compilation in Chapter 13, Alternative Generators and Cross-compilation.

The CMake documentation is a good starting point to learn more about generators: https://cmake.org/cmake/help/latest/manual/cmake-generators.7.html.

A project almost always consists of more than a single executable built from a single source file. Projects are split across multiple source files, often spread across different subdirectories in the source tree. This practice not only helps in keeping source code organized within a project, but greatly favors modularity, code reuse, and separation of concerns, since common tasks can be grouped into libraries. This separation also simplifies and speeds up recompilation of a project during development. In this recipe, we will show how to group sources into libraries and how to link targets against these libraries.

Let us go back to our very first example. However, instead of having one single source file for the executable, we will now introduce a class to wrap the message to be printed out to screen. This is our updated hello-world.cpp:

#include "Message.hpp"

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

Message say_hello("Hello, CMake World!");

std::cout << say_hello << std::endl;

Message say_goodbye("Goodbye, CMake World");

std::cout << say_goodbye << std::endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

The Message class wraps a string, provides an overload for the << operator, and consists of two source files: the Message.hpp header file and the corresponding Message.cpp source file. The Message.hpp interface file contains the following:

#pragma once

#include <iosfwd>

#include <string>

class Message {

public:

Message(const std::string &m) : message_(m) {}

friend std::ostream &operator<<(std::ostream &os, Message &obj) {

return obj.printObject(os);

}

private:

std::string message_;

std::ostream &printObject(std::ostream &os);

};

The corresponding implementation is contained in Message.cpp:

#include "Message.hpp"

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

std::ostream &Message::printObject(std::ostream &os) {

os << "This is my very nice message: " << std::endl;

os << message_;

return os;

}

These two new files will also have to be compiled and we have to modify CMakeLists.txt accordingly. However, in this example we want to compile them first into a library, and not directly into the executable:

add_library(message

STATIC

Message.hpp

Message.cpp

)

add_executable(hello-world hello-world.cpp)

target_link_libraries(hello-world message)

$ mkdir -p build

$ cd build

$ cmake ..

$ cmake --build .

Scanning dependencies of target message

[ 25%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/message.dir/Message.cpp.o

[ 50%] Linking CXX static library libmessage.a

[ 50%] Built target message

Scanning dependencies of target hello-world

[ 75%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/hello-world.dir/hello-world.cpp.o

[100%] Linking CXX executable hello-world

[100%] Built target hello-world

$ ./hello-world

This is my very nice message:

Hello, CMake World!

This is my very nice message:

Goodbye, CMake World

The previous example introduced two new commands:

After successful compilation, the build directory will contain the libmessage.a static library (on GNU/Linux) and the hello-world executable.

CMake accepts other values as valid for the second argument to add_library and we will encounter all of them in the rest of the book:

CMake is also able to generate special types of libraries. These produce no output in the build system but are extremely helpful in organizing dependencies and build requirements between targets:

In this example, we have collected the sources directly using add_library. In later chapters, we demonstrate the use of the target_sources CMake command to collect sources, in particular in Chapter 7, Structuring Projects. See also this wonderful blog post by Craig Scott: https://crascit.com/2016/01/31/enhanced-source-file-handling-with-target_sources/ which further motivates the use of the target_sources command.

Let us now show the use of the object library functionality made available in CMake. We will use the same source files, but modify CMakeLists.txt:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.5 FATAL_ERROR)

project(recipe-03 LANGUAGES CXX)

add_library(message-objs

OBJECT

Message.hpp

Message.cpp

)

# this is only needed for older compilers

# but doesn't hurt either to have it

set_target_properties(message-objs

PROPERTIES

POSITION_INDEPENDENT_CODE 1

)

add_library(message-shared

SHARED

$<TARGET_OBJECTS:message-objs>

)

add_library(message-static

STATIC

$<TARGET_OBJECTS:message-objs>

)

add_executable(hello-world hello-world.cpp)

target_link_libraries(hello-world message-static)

First, notice that the add_library command changed to add_library(message-objs OBJECT Message.hpp Message.cpp). Additionally, we have to make sure that the compilation to object files generates position-independent code. This is done by setting the corresponding property of the message-objs target, with the set_target_properties command.

This object library can now be used to obtain both the static library, called message-static, and the shared library, called message-shared. It is important to note the generator expression syntax used to refer to the object library: $<TARGET_OBJECTS:message-objs>. Generator expressions are constructs that CMake evaluates at generation time, right after configuration time, to produce configuration-specific build output. See also: https://cmake.org/cmake/help/latest/manual/cmake-generator-expressions.7.html. We will delve into generator expressions later in Chapter 5, Configure-time and Build-time Operations. Finally, the hello-world executable is linked with the static version of the message library.

Is it possible to have CMake generate the two libraries with the same name? In other words, can both of them be called message instead of message-static and message-shared? We will need to modify the properties of these two targets:

add_library(message-shared

SHARED

$<TARGET_OBJECTS:message-objs>

)

set_target_properties(message-shared

PROPERTIES

OUTPUT_NAME "message"

)

add_library(message-static

STATIC

$<TARGET_OBJECTS:message-objs>

)

set_target_properties(message-static

PROPERTIES

OUTPUT_NAME "message"

)

Can we link against the DSO? It depends on the operating system and compiler:

Why? Generating good DSOs requires the programmer to limit symbol visibility. This is achieved with the help of the compiler, but conventions are different on different operating systems and compilers. CMake has a powerful mechanism for taking care of this and we will explain how it works in Chapter 10, Writing an Installer.

So far, we have looked at fairly simple projects, where the execution flow for CMake was linear: from a set of source files to a single executable, possibly via static or shared libraries. To ensure complete control over the execution flow of all the steps involved in building a project, configuration, compilation, and linkage, CMake offers its own language. In this recipe, we will explore the use of the conditional construct if-elseif-else-endif.

Let us start with the same source code as for the previous recipe. We want to be able to toggle between two behaviors:

Let us construct CMakeLists.txt to achieve this:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.5 FATAL_ERROR)

project(recipe-04 LANGUAGES CXX)

set(USE_LIBRARY OFF)

message(STATUS "Compile sources into a library? ${USE_LIBRARY}")

set(BUILD_SHARED_LIBS OFF)

list(APPEND _sources Message.hpp Message.cpp)

if(USE_LIBRARY)

# add_library will create a static library

# since BUILD_SHARED_LIBS is OFF

add_library(message ${_sources})

add_executable(hello-world hello-world.cpp)

target_link_libraries(hello-world message)

else()

add_executable(hello-world hello-world.cpp ${_sources})

endif()

We have introduced two variables: USE_LIBRARY and BUILD_SHARED_LIBS. Both of them have been set to OFF. As detailed in the CMake language documentation, true or false values can be expressed in a number of ways:

The USE_LIBRARY variable will toggle between the first and the second behavior. BUILD_SHARED_LIBS is a global flag offered by CMake. Remember that the add_library command can be invoked without passing the STATIC/SHARED/OBJECT argument. This is because, internally, the BUILD_SHARED_LIBS global variable is looked up; if false or undefined, a static library will be generated.

This example shows that it is possible to introduce conditionals to control the execution flow in CMake. However, the current setup does not allow the toggles to be set from outside, that is, without modifying CMakeLists.txt by hand. In principle, we want to be able to expose all toggles to the user, so that configuration can be tweaked without modifying the code for the build system. We will show how to do that in a moment.

In the previous recipe, we introduced conditionals in a rather rigid fashion: by introducing variables with a given truth value hardcoded. This can be useful sometimes, but it prevents users of your code from easily toggling these variables. Another disadvantage of the rigid approach is that the CMake code does not communicate to the reader that this is a value that is expected to be modified from outside. The recommended way to toggle behavior in the build system generation for your project is to present logical switches as options in your CMakeLists.txt using the option() command. This recipe will show you how to use this command.

Let us have a look at our static/shared library example from the previous recipe. Instead of hardcoding USE_LIBRARY to ON or OFF, we will now prefer to expose it as an option with a default value that can be changed from the outside:

option(USE_LIBRARY "Compile sources into a library" OFF)

$ mkdir -p build

$ cd build

$ cmake -D USE_LIBRARY=ON ..

-- ...

-- Compile sources into a library? ON

-- ...

$ cmake --build .

Scanning dependencies of target message

[ 25%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/message.dir/Message.cpp.o

[ 50%] Linking CXX static library libmessage.a

[ 50%] Built target message

Scanning dependencies of target hello-world

[ 75%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/hello-world.dir/hello-world.cpp.o

[100%] Linking CXX executable hello-world

[100%] Built target hello-world

The -D switch is used to set any type of variable for CMake: logicals, paths, and so forth.

The option command accepts three arguments:

option(<option_variable> "help string" [initial value])

Sometimes there is the need to introduce options that are dependent on the value of other options. In our example, we might wish to offer the option to either produce a static or a shared library. However, this option would have no meaning if the USE_LIBRARY logical was not set to ON. CMake offers the cmake_dependent_option() command to define options that depend on other options:

include(CMakeDependentOption)

# second option depends on the value of the first

cmake_dependent_option(

MAKE_STATIC_LIBRARY "Compile sources into a static library" OFF

"USE_LIBRARY" ON

)

# third option depends on the value of the first

cmake_dependent_option(

MAKE_SHARED_LIBRARY "Compile sources into a shared library" ON

"USE_LIBRARY" ON

)

If USE_LIBRARY is ON, MAKE_STATIC_LIBRARY defaults to OFF, while MAKE_SHARED_LIBRARY defaults to ON. So we can run this:

$ cmake -D USE_LIBRARY=OFF -D MAKE_SHARED_LIBRARY=ON ..

This will still not build a library, since USE_LIBRARY is still set to OFF.

As mentioned earlier, CMake has mechanisms in place to extend its syntax and capabilities through the inclusion of modules, either shipped with CMake itself or custom ones. In this case, we have included a module called CMakeDependentOption. Without the include statement, the cmake_dependent_option() command would not be available for use. See also https://cmake.org/cmake/help/latest/module/CMakeDependentOption.html.

One aspect that we have not given much thought to so far is the selection of compilers. CMake is sophisticated enough to select the most appropriate compiler given the platform and the generator. CMake is also able to set compiler flags to a sane set of defaults. However, often we wish to control the choice of the compiler, and in this recipe we will show how this can be done. In later recipes, we will also consider the choice of build type and show how to control compiler flags.

How can we select a specific compiler? For example, what if we want to use the Intel or Portland Group compilers? CMake stores compilers for each language in the CMAKE_<LANG>_COMPILER variable, where <LANG> is any of the supported languages, for our purposes CXX, C, or Fortran. The user can set this variable in one of two ways:

$ cmake -D CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER=clang++ ..

$ env CXX=clang++ cmake ..

Any of the recipes discussed so far can be configured for use with any other compiler by passing the appropriate option.

We have here assumed that the additional compilers are available in the standard paths where CMake does its lookups. If that is not the case, the user will need to pass the full path to the compiler executable or wrapper.

At configure time, CMake performs a series of platform tests to determine which compilers are available and if they are suitable for the project at hand. A suitable compiler is not only determined by the platform we are working on, but also by the generator we want to use. The first test CMake performs is based on the name of the compiler for the project language. For example, if cc is a working C compiler, then that is what will be used as the default compiler for a C project. On GNU/Linux, using Unix Makefiles or Ninja, the compilers in the GCC family will be most likely chosen by default for C++, C, and Fortran. On Microsoft Windows, the C++ and C compilers in Visual Studio will be selected, provided Visual Studio is the generator. MinGW compilers are the default if MinGW or MSYS Makefiles were chosen as generators.

Where can we find which default compilers and compiler flags will be picked up by CMake for our platform? CMake offers the --system-information flag, which will dump all information about your system to the screen or a file. To see this, try the following:

$ cmake --system-information information.txt

Searching through the file (in this case, information.txt), you will find the default values for the CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER, CMAKE_C_COMPILER, and CMAKE_Fortran_COMPILER options, together with their default flags. We will have a look at the flags in the next recipe.

CMake provides additional variables to interact with compilers:

We can try to configure the following example CMakeLists.txt with different compilers. In this example, we will use CMake variables to probe what compiler we are using and what version:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.5 FATAL_ERROR)

project(recipe-06 LANGUAGES C CXX)

message(STATUS "Is the C++ compiler loaded? ${CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER_LOADED}")

if(CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER_LOADED)

message(STATUS "The C++ compiler ID is: ${CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER_ID}")

message(STATUS "Is the C++ from GNU? ${CMAKE_COMPILER_IS_GNUCXX}")

message(STATUS "The C++ compiler version is: ${CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER_VERSION}")

endif()

message(STATUS "Is the C compiler loaded? ${CMAKE_C_COMPILER_LOADED}")

if(CMAKE_C_COMPILER_LOADED)

message(STATUS "The C compiler ID is: ${CMAKE_C_COMPILER_ID}")

message(STATUS "Is the C from GNU? ${CMAKE_COMPILER_IS_GNUCC}")

message(STATUS "The C compiler version is: ${CMAKE_C_COMPILER_VERSION}")

endif()

Observe that this example does not contain any targets, so there is nothing to build and we will only focus on the configuration step:

$ mkdir -p build

$ cd build

$ cmake ..

...

-- Is the C++ compiler loaded? 1

-- The C++ compiler ID is: GNU

-- Is the C++ from GNU? 1

-- The C++ compiler version is: 8.1.0

-- Is the C compiler loaded? 1

-- The C compiler ID is: GNU

-- Is the C from GNU? 1

-- The C compiler version is: 8.1.0

...

The output will of course depend on the available and chosen compilers and compiler versions.

CMake has the notion of build types or configurations, such as Debug, Release, and so forth. Within one configuration, one can collect related options or properties, such as compiler and linker flags, for a Debug or Release build. The variable governing the configuration to be used when generating the build system is CMAKE_BUILD_TYPE. This variable is empty by default, and the values recognized by CMake are:

In this recipe, we will show how the build type can be set for an example project:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.5 FATAL_ERROR)

project(recipe-07 LANGUAGES C CXX)

if(NOT CMAKE_BUILD_TYPE)

set(CMAKE_BUILD_TYPE Release CACHE STRING "Build type" FORCE)

endif()

message(STATUS "Build type: ${CMAKE_BUILD_TYPE}")

message(STATUS "C flags, Debug configuration: ${CMAKE_C_FLAGS_DEBUG}")

message(STATUS "C flags, Release configuration: ${CMAKE_C_FLAGS_RELEASE}")

message(STATUS "C flags, Release configuration with Debug info: ${CMAKE_C_FLAGS_RELWITHDEBINFO}")

message(STATUS "C flags, minimal Release configuration: ${CMAKE_C_FLAGS_MINSIZEREL}")

message(STATUS "C++ flags, Debug configuration: ${CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_DEBUG}")

message(STATUS "C++ flags, Release configuration: ${CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE}")

message(STATUS "C++ flags, Release configuration with Debug info: ${CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELWITHDEBINFO}")

message(STATUS "C++ flags, minimal Release configuration: ${CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_MINSIZEREL}")

$ mkdir -p build

$ cd build

$ cmake ..

...

-- Build type: Release

-- C flags, Debug configuration: -g

-- C flags, Release configuration: -O3 -DNDEBUG

-- C flags, Release configuration with Debug info: -O2 -g -DNDEBUG

-- C flags, minimal Release configuration: -Os -DNDEBUG

-- C++ flags, Debug configuration: -g

-- C++ flags, Release configuration: -O3 -DNDEBUG

-- C++ flags, Release configuration with Debug info: -O2 -g -DNDEBUG

-- C++ flags, minimal Release configuration: -Os -DNDEBUG

$ cmake -D CMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Debug ..

-- Build type: Debug

-- C flags, Debug configuration: -g

-- C flags, Release configuration: -O3 -DNDEBUG

-- C flags, Release configuration with Debug info: -O2 -g -DNDEBUG

-- C flags, minimal Release configuration: -Os -DNDEBUG

-- C++ flags, Debug configuration: -g

-- C++ flags, Release configuration: -O3 -DNDEBUG

-- C++ flags, Release configuration with Debug info: -O2 -g -DNDEBUG

-- C++ flags, minimal Release configuration: -Os -DNDEBUG

We have demonstrated how to set a default build type and how to override it from the command line. With this, we can control whether a project is built with optimization flags or with all optimizations turned off, and instead debugging information on. We have also seen what kind of flags are used for the various available configurations, as this depends on the compiler of choice. Instead of printing the flags explicitly during a run of CMake, one can also peruse the output of running cmake --system-information to find out what the presets are for the current combination of platform, default compiler, and language. In the next recipe, we will discuss how to extend or adjust compiler flags for different compilers and different build types.

We have shown how the variable CMAKE_BUILD_TYPE (documented at this link: https://cmake.org/cmake/help/v3.5/variable/CMAKE_BUILD_TYPE.html) defines the configuration of the generated build system. It is often helpful to build a project both in Release and Debug configurations, for example when assessing the effect of compiler optimization levels. For single-configuration generators, such as Unix Makefiles, MSYS Makefiles or Ninja, this requires running CMake twice, that is a full reconfiguration of the project. CMake however also supports multiple-configuration generators. These are usually project files offered by integrated-development environments, most notably Visual Studio and Xcode which can handle more than one configuration simultaneously. The available configuration types for these generators can be tweaked with the CMAKE_CONFIGURATION_TYPES variable which will accept a list of values (documentation available at this link: https://cmake.org/cmake/help/v3.5/variable/CMAKE_CONFIGURATION_TYPES.html).

The following CMake invocation with the Visual Studio:

$ mkdir -p build

$ cd build

$ cmake .. -G"Visual Studio 12 2017 Win64" -D CMAKE_CONFIGURATION_TYPES="Release;Debug"

will generate a build tree for both the Release and Debug configuration. You can then decide which of the two to build by using the --config flag:

$ cmake --build . --config Release

The previous recipes showed how to probe CMake for information on the compilers and how to tune compiler optimizations for all targets in your project. The latter task is a subset of the general need to control which compiler flags are used in your project. CMake offers a lot of flexibility for adjusting or extending compiler flags and you can choose between two main approaches:

In this recipe, we will show both approaches.

We will compile an example program to calculate the area of different geometric shapes. The code has a main function in a file called compute-areas.cpp:

#include "geometry_circle.hpp"

#include "geometry_polygon.hpp"

#include "geometry_rhombus.hpp"

#include "geometry_square.hpp"

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

using namespace geometry;

double radius = 2.5293;

double A_circle = area::circle(radius);

std::cout << "A circle of radius " << radius << " has an area of " << A_circle

<< std::endl;

int nSides = 19;

double side = 1.29312;

double A_polygon = area::polygon(nSides, side);

std::cout << "A regular polygon of " << nSides << " sides of length " << side

<< " has an area of " << A_polygon << std::endl;

double d1 = 5.0;

double d2 = 7.8912;

double A_rhombus = area::rhombus(d1, d2);

std::cout << "A rhombus of major diagonal " << d1 << " and minor diagonal " << d2

<< " has an area of " << A_rhombus << std::endl;

double l = 10.0;

double A_square = area::square(l);

std::cout << "A square of side " << l << " has an area of " << A_square

<< std::endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

The implementations of the various functions are contained in other files: each geometric shape has a header file and a corresponding source file. In total, we have four header files and five source files to compile:

.

├── CMakeLists.txt

├── compute-areas.cpp

├── geometry_circle.cpp

├── geometry_circle.hpp

├── geometry_polygon.cpp

├── geometry_polygon.hpp

├── geometry_rhombus.cpp

├── geometry_rhombus.hpp

├── geometry_square.cpp

└── geometry_square.hpp

We will not provide listings for all these files but rather refer the reader to https://github.com/dev-cafe/cmake-cookbook/tree/v1.0/chapter-01/recipe-08.

Now that we have the sources in place, our goal will be to configure the project and experiment with compiler flags:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.5 FATAL_ERROR)

project(recipe-08 LANGUAGES CXX)

message("C++ compiler flags: ${CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS}")

list(APPEND flags "-fPIC" "-Wall")

if(NOT WIN32)

list(APPEND flags "-Wextra" "-Wpedantic")

endif()

add_library(geometry

STATIC

geometry_circle.cpp

geometry_circle.hpp

geometry_polygon.cpp

geometry_polygon.hpp

geometry_rhombus.cpp

geometry_rhombus.hpp

geometry_square.cpp

geometry_square.hpp

)

target_compile_options(geometry

PRIVATE

${flags}

)

add_executable(compute-areas compute-areas.cpp)

target_compile_options(compute-areas

PRIVATE

"-fPIC"

)

target_link_libraries(compute-areas geometry)

In this example, the warning flags -Wall, -Wextra, and -Wpedantic will be added to the compile options for the geometry target; both the compute-areas and geometry targets will use the -fPIC flag. Compile options can be added with three levels of visibility: INTERFACE, PUBLIC, and PRIVATE.

The visibility levels have the following meaning:

The visibility levels of target properties are at the core of a modern usage of CMake and we will revisit this topic often and extensively throughout the book. Adding compile options in this way does not pollute the CMAKE_<LANG>_FLAGS_<CONFIG> global CMake variables and gives you granular control over what options are used on which targets.

How can we verify whether the flags are correctly used as we intended to? Or in other words, how can you discover which compile flags are actually used by a CMake project? One approach is the following and it uses CMake to pass additional arguments, in this case the environment variable VERBOSE=1, to the native build tool:

$ mkdir -p build

$ cd build

$ cmake ..

$ cmake --build . -- VERBOSE=1

... lots of output ...

[ 14%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/geometry.dir/geometry_circle.cpp.o

/usr/bin/c++ -fPIC -Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic -o CMakeFiles/geometry.dir/geometry_circle.cpp.o -c /home/bast/tmp/cmake-cookbook/chapter-01/recipe-08/cxx-example/geometry_circle.cpp

[ 28%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/geometry.dir/geometry_polygon.cpp.o

/usr/bin/c++ -fPIC -Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic -o CMakeFiles/geometry.dir/geometry_polygon.cpp.o -c /home/bast/tmp/cmake-cookbook/chapter-01/recipe-08/cxx-example/geometry_polygon.cpp

[ 42%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/geometry.dir/geometry_rhombus.cpp.o

/usr/bin/c++ -fPIC -Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic -o CMakeFiles/geometry.dir/geometry_rhombus.cpp.o -c /home/bast/tmp/cmake-cookbook/chapter-01/recipe-08/cxx-example/geometry_rhombus.cpp

[ 57%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/geometry.dir/geometry_square.cpp.o

/usr/bin/c++ -fPIC -Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic -o CMakeFiles/geometry.dir/geometry_square.cpp.o -c /home/bast/tmp/cmake-cookbook/chapter-01/recipe-08/cxx-example/geometry_square.cpp

... more output ...

[ 85%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/compute-areas.dir/compute-areas.cpp.o

/usr/bin/c++ -fPIC -o CMakeFiles/compute-areas.dir/compute-areas.cpp.o -c /home/bast/tmp/cmake-cookbook/chapter-01/recipe-08/cxx-example/compute-areas.cpp

... more output ...

The preceding output confirms that the compile flags were correctly set according to our instructions.

The second approach to controlling compiler flags involves no modifications to CMakeLists.txt. If one wants to modify compiler options for the geometry and compute-areas targets in this project, it is as easy as invoking CMake with an additional argument:

$ cmake -D CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS="-fno-exceptions -fno-rtti" ..

As you might have guessed, this command will compile the project, deactivating exceptions and runtime type identification (RTTI).

The two approaches can also be coupled. One can use a basic set of flags globally, while keeping control of what happens on a per target basis. We can use CMakeLists.txt and running this command:

$ cmake -D CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS="-fno-exceptions -fno-rtti" ..

This will configure the geometry target with -fno-exceptions -fno-rtti -fPIC -Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic, while configuring compute-areas with -fno-exceptions -fno-rtti -fPIC.

Most of the time, flags are compiler-specific. Our current example will only work with GCC and Clang; compilers from other vendors will not understand many, if not all, of those flags. Clearly, if a project aims at being truly cross-platform, this problem has to be solved. There are three approaches to this.

The most typical approach will append a list of desired compiler flags to each configuration type CMake variable, that is, to CMAKE_<LANG>_FLAGS_<CONFIG>. These flags are set to what is known to work for the given compiler vendor, and will thus be enclosed in

if-endif clauses that check the CMAKE_<LANG>_COMPILER_ID variable, for example:

if(CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER_ID MATCHES GNU)

list(APPEND CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS "-fno-rtti" "-fno-exceptions")

list(APPEND CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_DEBUG "-Wsuggest-final-types" "-Wsuggest-final-methods" "-Wsuggest-override")

list(APPEND CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE "-O3" "-Wno-unused")

endif()

if(CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER_ID MATCHES Clang)

list(APPEND CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS "-fno-rtti" "-fno-exceptions" "-Qunused-arguments" "-fcolor-diagnostics")

list(APPEND CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_DEBUG "-Wdocumentation")

list(APPEND CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE "-O3" "-Wno-unused")

endif()

A more refined approach does not tamper with the CMAKE_<LANG>_FLAGS_<CONFIG> variables at all and rather defines project-specific lists of flags:

set(COMPILER_FLAGS)

set(COMPILER_FLAGS_DEBUG)

set(COMPILER_FLAGS_RELEASE)

if(CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER_ID MATCHES GNU)

list(APPEND CXX_FLAGS "-fno-rtti" "-fno-exceptions")

list(APPEND CXX_FLAGS_DEBUG "-Wsuggest-final-types" "-Wsuggest-final-methods" "-Wsuggest-override")

list(APPEND CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE "-O3" "-Wno-unused")

endif()

if(CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER_ID MATCHES Clang)

list(APPEND CXX_FLAGS "-fno-rtti" "-fno-exceptions" "-Qunused-arguments" "-fcolor-diagnostics")

list(APPEND CXX_FLAGS_DEBUG "-Wdocumentation")

list(APPEND CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE "-O3" "-Wno-unused")

endif()

Later on, it uses generator expressions to set compiler flags on a per-configuration and per-target basis:

target_compile_option(compute-areas

PRIVATE

${CXX_FLAGS}

"$<$<CONFIG:Debug>:${CXX_FLAGS_DEBUG}>"

"$<$<CONFIG:Release>:${CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE}>"

)

We have shown both approaches in the current recipe and have clearly recommended the latter (project-specific variables and target_compile_options) over the former (CMake variables).

Both approaches work and are widely used in many projects. However, they have shortcomings. As we have already mentioned, CMAKE_<LANG>_COMPILER_ID is not guaranteed to be defined for all compiler vendors. In addition, some flags might become deprecated or might have been introduced in a later version of the compiler. Similarly to CMAKE_<LANG>_COMPILER_ID, the CMAKE_<LANG>_COMPILER_VERSION variable is not guaranteed to be defined for all languages and vendors. Although checking on these variables is quite popular, we think that a more robust alternative would be to check whether a desired set of flags works with the given compiler, so that only effectively working flags are actually used in the project. Combined with the use of project-specific variables, target_compile_options, and generator expressions, this approach is quite powerful. We will show how to use this check-and-set pattern in Recipe 3, Writing a function to test and set compiler flags, in Chapter 7, Structuring Projects.

Programming languages have different standards available, that is, different versions that offer new and improved language constructs. Enabling new standards is accomplished by setting the appropriate compiler flag. We have shown in the previous recipe how this can be done, either on a per-target basis or globally. With its 3.1 version, CMake introduced a platform- and compiler-independent mechanism for setting the language standard for C++ and C: setting the <LANG>_STANDARD property for targets.

For the following example, we will require a C++ compiler compliant with the C++14 standard or later. The code for this recipe defines a polymorphic hierarchy of animals. We use std::unique_ptr for the base class in the hierarchy:

std::unique_ptr<Animal> cat = Cat("Simon");

std::unique_ptr<Animal> dog = Dog("Marlowe);

Instead of explicitly using constructors for the various subtypes, we use an implementation of the factory method. The factory is implemented using C++11 variadic templates. It holds a map of creation functions for each object in the inheritance hierarchy:

typedef std::function<std::unique_ptr<Animal>(const std::string &)> CreateAnimal;

It dispatches them based on a preassigned tag, so that creation of objects will look like the following:

std::unique_ptr<Animal> simon = farm.create("CAT", "Simon");

std::unique_ptr<Animal> marlowe = farm.create("DOG", "Marlowe");

The tags and creation functions are registered to the factory prior to its use:

Factory<CreateAnimal> farm;

farm.subscribe("CAT", [](const std::string & n) { return std::make_unique<Cat>(n); });

farm.subscribe("DOG", [](const std::string & n) { return std::make_unique<Dog>(n); });

We are defining the creation functions using C++11 lambda functions. Notice the use of std::make_unique to avoid introducing the naked new operator. This helper was introduced in C++14.

We will construct the CMakeLists.txt step by step and show how to require a certain standard (in this case C++14):

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.5 FATAL_ERROR)

project(recipe-09 LANGUAGES CXX)

set(CMAKE_WINDOWS_EXPORT_ALL_SYMBOLS ON)

add_library(animals

SHARED

Animal.cpp

Animal.hpp

Cat.cpp

Cat.hpp

Dog.cpp

Dog.hpp

Factory.hpp

)

set_target_properties(animals

PROPERTIES

CXX_STANDARD 14