Appendix B. OAuth2 grant types

- OAuth2 Password grant

- OAuth2 Client credentials grant

- OAuth2 Authorization code grant

- OAuth2 Implicit credentials grant

- OAuth2 Token Refreshing

From reading chapter 7, you might be thinking that OAuth2 doesn’t look too complicated. After all, you have an authentication service that checks a user’s credentials and issues a token back to the user. The token can, in turn, be presented every time the user wants to call a service protected by the OAuth2 server.

Unfortunately, the real world is never simple. With the interconnected nature of the web and cloud-based applications, users have come to expect that they can securely share their data and integrate functionality between different applications owned by different services. This presents a unique challenge from a security perspective because you want to integrate across different applications while not forcing users to share their credentials with each application they want to integrate with.

Fortunately, OAuth2 is a flexible authorization framework that provides multiple mechanisms for applications to authenticate and authorize users without forcing them to share credentials. Unfortunately, it’s also one of the reasons why OAuth2 is considered complicated. These authentication mechanisms are called authentication grants. OAuth2 has four forms of authentication grants that client applications can use to authenticate users, receive an access token, and then validate that token. These grants are

- Password

- Client credential

- Authorization code

- Implicit

In the following sections I walk through the activities that take place during the execution of each of these OAuth2 grant flows. I also talk about when to use one grant type over another.

B.1. Password grants

An OAuth2 password grant is probably the most straightforward grant type to understand. This grant type is used when both the application and the services explicitly trust one another. For example, the EagleEye web application and the EagleEye web services (the licensing and organization) are both owned by ThoughtMechanix, so there’s a natural trust relationship that exists between them.

Note

To be explicit, when I refer to a “natural trust relationship” I mean that the application and services are completely owned by the same organization. They’re managed under the same policies and procedures.

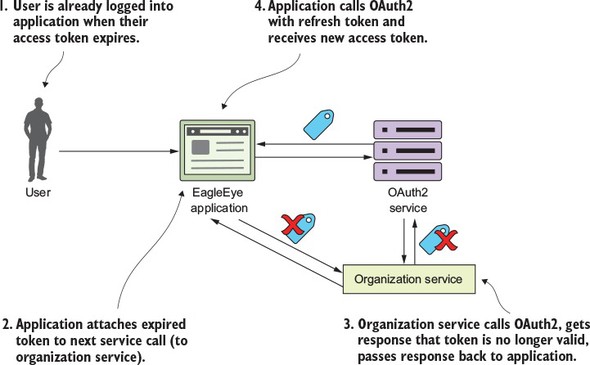

When a natural trust relationship exists, there’s little concern about exposing an OAuth2 access token to the calling application. For example, the EagleEye web application can use the OAuth2 password grant to capture the user’s credentials and directly authenticate against the EagleEye OAuth2 service. Figure B.1 shows the password grant in action between EagleEye and the downstream services.

Figure B.1. The OAuth2 service determines if the user accessing the service is an authenticated user.

In figure B.1 the following actions are taking place:

- Before the EagleEye application can use a protected resource, it needs to be uniquely identified within the OAuth2 service. Normally, the owner of the application registers with the OAuth2 application service and provides a unique name for their application. The OAuth2 service then provides a secret key back to registering the application. The name of the application and the secret key provided by the OAuth2 service uniquely identifies the application trying to access any protected resources.

- The user logs into EagleEye and provides their login credentials to the EagleEye application. EagleEye passes the user credentials, along with the application name/application secret key, directly to the EagleEye OAuth2 service.

- The EagleEye OAuth2 service authenticates the application and the user and then provides an OAuth2 access token back to the user.

- Every time the EagleEye application calls a service on behalf of the user, it passes along the access token provided by the OAuth2 server.

- When a protected service is called (in this case, the licensing and organization service), the service calls back into the EagleEye OAuth2 service to validate the token. If the token is good, the service being invoked allows the user to proceed. If the token is invalid, the OAuth2 service returns back an HTTP status code of 403, indicating that the token is invalid.

B.2. Client credential grants

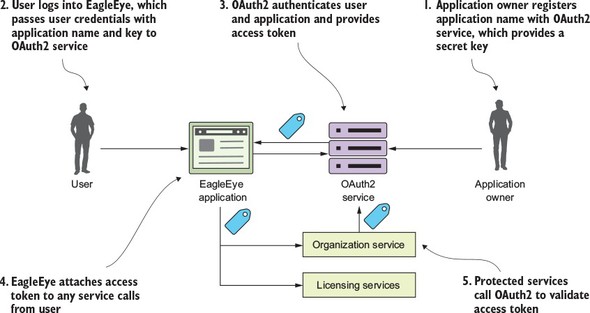

The client credentials grant is typically used when an application needs to access an OAuth2 protected resource, but no human being is involved in the transaction. With the client credentials grant type, the OAuth2 server only authenticates based on application name and the secret key provided by the owner of the resource. Again, the client credential task is usually used when both applications are owned by the same company. The difference between the password grant and the client credential grant is that a client credential grant authenticates by only using the registered application name and the secret key.

For example, let’s say that once an hour the EagleEye application has a data analytics job that runs. As part of its work, it makes calls out to EagleEye services. However, the EagleEye developers still want that application to authenticate and authorize itself before it can access the data in those services. This is where the client credential grant can be used. Figure B.2 shows this flow.

Figure B.2. The client credential grant is for “no-user-involved” application authentication and authorization.

- The resource owner registers the EagleEye data analytics application with the OAuth2 service. The resource owner will provide the application name and receive back a secret key.

- When the EagleEye data analytics job runs, it will present its application name and secret key provided by the resource owner.

- The EagleEye OAuth2 service will authenticate the application using the application name and the secret key provided and then return back an OAuth2 access token.

- Every time the application calls one of the EagleEye services, it will present the OAuth2 access token it received with the service call.

B.3. Authorization code grants

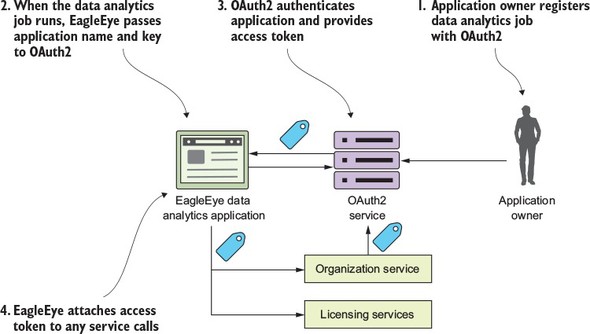

The authorization code grant is by far the most complicated of the OAuth2 grants, but it’s also the most common flow used because it allows different applications from different vendors to share data and services without having to expose a user’s credentials across multiple applications. It also enforces an extra layer of checking by not letting a calling application immediately get an OAuth2 access token, but rather a “pre-access” authorization code.

The easy way to understand the authorization grant is through an example. Let’s say you have an EagleEye user who also uses Salesforce.com. The EagleEye customer’s IT department has built a Salesforce application that needs data from an EagleEye service (the organization service). Let’s walk through figure B.3 and see how the authorization code grant flow works to allow Salesforce to access data from the EagleEye organization service, without the EagleEye customer ever having to expose their EagleEye credentials to Salesforce.

Figure B.3. The authentication code grant allows applications to share data without exposing user credentials.

- The EagleEye user logs in to EagleEye and generates an application name and application secret key for their Salesforce application. As part of the registration process, they’ll also provide a callback URL back to their Salesforce-based application. This callback URL is a Salesforce URL that will be called after the EagleEye OAuth2 server has authenticated the user’s EagleEye credentials.

- The user configures their Salesforce application with the following information:

- Their application name they created for Salesforce

- The secret key they generated for Salesforce

- A URL that points to the EagleEye OAuth2 login page

- Now when the user tries to use their Salesforce application and access their EagleEye data via the organization service, they’ll be redirected over to the EagleEye login page via the URL described in the previous bullet point. The user will provide their EagleEye credentials. If they’ve provided valid EagleEye credentials, the EagleEye OAuth2 server will generate an authorization code and redirect the user back to SalesForce via the URL provided in number 1. The authorization code will be sent as a query parameter on the callback URL.

- The custom Salesforce application will persist this authorization code. Note: this authorization code isn’t an OAuth2 access token.

- Once the authorization code has been stored, the custom Salesforce application can present the Salesforce application the secret key they generated during the registration process and the authorization code back to EagleEye OAuth2 server. The EagleEye OAuth2 server will validate that the authorization code is valid and then return back an OAuth2 token to the custom Salesforce application. This authorization code is used every time the custom Salesforce needs to authenticate the user and get an OAuth2 access token.

- The Salesforce application will call the EagleEye organization service, passing an OAuth2 token in the header.

- The organization service will validate the OAuth2 access token passed in to the EagleEye service call with the EagleEye OAuth2 service. If the token is valid, the organization service will process the user’s request.

Wow! I need to come up for air. Application-to-application integration is convoluted. The key to note from this entire process is that even though the user is logged into Salesforce and they’re accessing EagleEye data, at no time were the user’s EagleEye credentials directly exposed to Salesforce. After the initial authorization code was generated and provided by the EagleEye OAuth2 service, the user never had to provide their credentials back to the EagleEye service.

B.4. Implicit grant

The authorization grant is used when you’re running a web application through a traditional server-side web programming environment like Java or .NET. What happens if your client application is a pure JavaScript application or a mobile application that runs completely in a web browser and doesn’t rely on server-side calls to invoke third-party services?

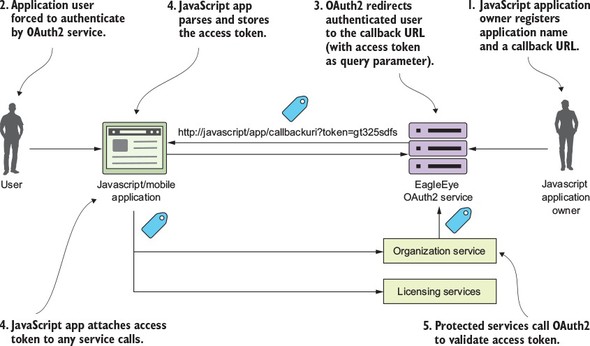

This is where the last grant type, the implicit grant, comes into play. Figure B.4 shows the general flow of what occurs in the implicit grant.

Figure B.4. The implicit grant is used in a browser-based Single-Page Application (SPA) JavaScript application.

With an implicit grant, you’re usually working with a pure JavaScript application running completely inside of the browser. In the other flows, the client is communicating with an application server that’s carrying out the user’s requests and the application server is interacting with any downstream services. With an implicit grant type, all the service interaction happens directly from the user’s client (usually a web browser). In figure B.4, the following activities are taking place:

- The owner of the JavaScript application has registered the application with the EagleEye OAuth2 server. They’ve provided an application name and also a callback URL that will be redirected with the OAuth2 access token for the user.

- The JavaScript application will call to the OAuth2 service. The JavaScript application must present a pre-registered application name. The OAuth2 server will force the user to authenticate.

- If the user successfully authenticates, the EagleEye OAuth2 service won’t return a token, but instead redirect the user back to a page the owner of the JavaScript application registered in step one. In the URL being redirected back to, the OAuth2 access token will be passed as a query parameter by the OAuth2 authentication service.

- The application will take the incoming request and run a JavaScript script that will parse the OAuth2 access token and store it (usually as a cookie).

- Every time a protected resource is called, the OAuth2 access token is presented to the calling service.

- The calling service will validate the OAuth2 token and check that the user is authorized to do the activity they’re attempting to do.

Keep several things in mind regarding the OAuth2 implicit grant:

- The implicit grant is the only grant type where the OAuth2 access token is directly exposed to a public client (web browser). In the authorization grant, the client application gets an authorization code returned back to the application server hosting the application. With an authorization code grant, the user is granted an OAuth2 access by presenting the authorization code. The returned OAuth2 token is never directly exposed to the user’s browser. In the client credentials grant, the grant occurs between two server-based applications. In the password grant, both the application making the request for a service and the services are trusted and are owned by the same organization.

- OAuth2 tokens generated by the implicit grant are more vulnerable to attack and misuse because the tokens are made available to the browser. Any malicious JavaScript running in the browser can get access to the OAuth2 access token and call the services you retrieved the OAuth2 token for on your behalf and essentially impersonate you.

- The implicit grant type OAuth2 tokens should be short-lived (1-2 hours). Because the OAuth2 access token is stored in the browser, the OAuth2 spec (and Spring Cloud security) doesn’t support the concept of a refresh token in which a token can be automatically renewed.

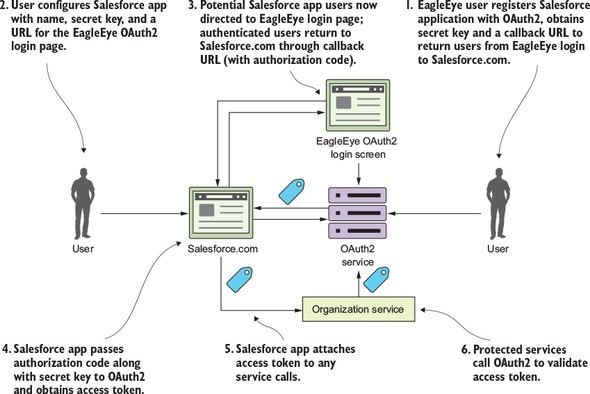

B.5. How tokens are refreshed

When an OAuth2 access token is issued, it has a limited amount of time that it’s valid and will eventually expire. When the token expires, the calling application (and user) will need to re-authenticate with the OAuth2 service. However, in most of the Oauth2 grant flows, the OAuth2 server will issue both an access token and a refresh token. A client can present the refresh token to the OAuth2 authentication service and the service will validate the refresh token and then issue a new OAuth2 access token. Let’s look at figure B.5 and walk through the refresh token flow:

- The user has logged into EagleEye and is already authenticated with the EagleEye OAuth2 service. The user is happily working, but unfortunately their token has expired.

- The next time the user tries to call a service (say the organization service), the EagleEye application will pass the expired token to the organization service.

- The organization service will try to validate the token with the OAuth2 service, which return an HTTP status code 401 (unauthorized) and a JSON payload indicating that the token is no longer valid. The organization service will return an HTTP 401 status code back to the calling service.

- The EagleEye application gets the 401 HTTP status code and the JSON payload indicating the reason the call failed back from the organization service. The EagleEye application will then call the OAuth2 authentication service with the refresh token. The OAuth2 authentication service will validate the refresh token and then send back a new access token.

Figure B.5. The refresh token flow allows an application to get a new access token without forcing the user to re-authenticate.