Chapter 8. Event-driven architecture with Spring Cloud Stream

- Understanding event-driven architecture processing and its relevance to microservices

- Using Spring Cloud Stream to simplify event processing in your microservices

- Configuring Spring Cloud Stream

- Publishing messages with Spring Cloud Stream and Kafka

- Consuming messages with Spring Cloud Stream and Kafka

- Implementing distributed caching with Spring Cloud Stream, Kafka, and Redis

When was the last time you sat down with another person and had a conversation? Think back about how you interacted with that other person. Was it a totally focused exchange of information where you said something and then did nothing else while you waited for the person to respond in full? Were you completely focused on the conversation and let nothing from the outside world distract you while you were speaking? If there were more than two people in the conversation, did you repeat something you said perfectly over and over to each conversation participant and wait in turn for their response? If you said yes to these questions, you have reached enlightenment, are a better human being than me, and should stop what you’re doing because you can now answer the age-old question, “What is the sound of one object clapping?” Also, I suspect you don’t have children.

The reality is that human beings are constantly in a state of motion, interacting with their environment around them, while sending out and receiving information from the things around them. In my house a typical conversation might be something like this. I’m busy washing the dishes while talking to my wife. I’m telling her about my day. She’s looking at her phone and she’s listening, processing what I’m saying, and occasionally responding back. As I’m washing the dishes, I hear a commotion in the next room. I stop what I’m doing, rush into the next room to find out what’s wrong and see that our rather large nine-month-old puppy, Vader, has taken my three-year-old son’s shoe, and is trotting around the living room carrying the shoe like a trophy. My three-year-old isn’t happy about this. I run through the house, chasing the dog until I get the shoe back. I then go back to the dishes and my conversation with my wife.

My point in telling you this isn’t to tell you about a typical day in my life, but rather to point out that our interaction with the world isn’t synchronous, linear, and narrowly defined to a request-response model. It’s message-driven, where we’re constantly sending and receiving messages. As we receive messages, we react to those messages, while often interrupting the primary task that we’re working on.

This chapter is about how to design and implement your Spring-based microservices to communicate with other microservices using asynchronous messages. Using asynchronous messages to communicate between applications isn’t new. What’s new is the concept of using messages to communicate events representing changes in state. This concept is called Event Driven Architecture (EDA). It’s also known as Message Driven Architecture (MDA). What an EDA-based approach allows you to do is to build highly decoupled systems that can react to changes without being tightly coupled to specific libraries or services. When combined with microservices, EDA allows you to quickly add new functionality into your application by merely having the service listen to the stream of events (messages) being emitted by your application.

The Spring Cloud project has made it trivial to build messaging-based solutions through the Spring Cloud Stream sub-project. Spring Cloud Stream allows you to easily implement message publication and consumption, while shielding your services from the implementation details associated with the underlying messaging platform.

8.1. The case for messaging, EDA, and microservices

Why is messaging important in building microservice-based applications? To answer that question, let’s start with an example. We’re going to use the two services we’ve been using throughout the book: your licensing and organization services. Let’s imagine that after these services are deployed to production, you find that the licensing service calls are taking an exceedingly long time when doing a lookup of organization information from the organization service. When you look at the usage patterns of the organization data, you find that the organization data rarely changes and that most of the data reads from the organization service are done by the primary key of the organization record. If you could cache the reads for the organization data without having to incur the cost of accessing a database, you could greatly improve the response time of the licensing service calls.

As you look at implementing a caching solution, you realize you have three core requirements:

- The cached data needs to be consistent across all instances of the licensing service— This means that you can’t cache the data locally within the licensing service because you want to guarantee that the same organization data is read regardless of the service instance hitting it.

- You cannot cache the organization data within the memory of the container hosting the licensing service— The run-time container hosting your service is often restricted in size and can access data using different access patterns. A local cache can introduce complexity because you have to guarantee your local cache is synced with all of the other services in the cluster.

- When an organization record changes via an update or delete, you want the licensing service to recognize that there has been a state change in the organization service— The licensing service should then invalidate any cached data it has for that specific organization and evict it from the cache.

Let’s look at two approaches for implementing these requirements. The first approach will implement the above requirements using a synchronous request-response model. When the organization state changes, the licensing and organization services communicate back and forth via their REST endpoints. The second approach will have the organization service emit an asynchronous event (message) that will communicate that the organization service data has changed. With the second approach, the organization service will publish a message to a queue that an organization record has been updated or deleted. The licensing service will listen with the intermediary, see that an organization event has occurred, and clear the organization data from its cache.

8.1.1. Using synchronous request-response approach to communicate state change

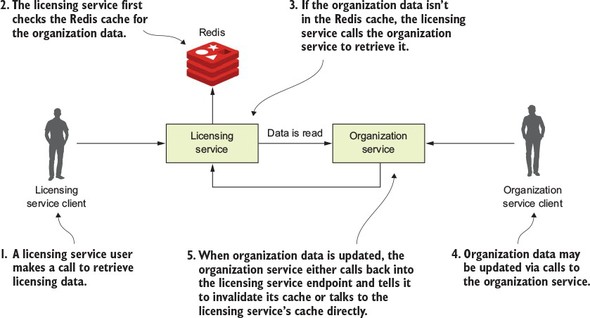

For your organization data cache, you’re going to use Redis (http://redis.io/), a distributed key-value store database. Figure 8.1 provides a high-level overview of how to build a caching solution using a traditional synchronous, request-response programming model.

Figure 8.1. In a synchronous request-response model, tightly coupled services introduce complexity and brittleness.

In figure 8.1, when a user calls the licensing service, the licensing service will need to also look up organization data. The licensing service will first check to retrieve the desired organization by its ID from the Redis cluster. If the licensing service can’t find the organization data, it will call the organization service using a REST-based endpoint and then store the data returned in Redis, before returning the organization data back to the user. Now, if someone updates or deletes the organization record using the organization service’s REST endpoint, the organization service will need to call an endpoint exposed on the licensing service, telling it to invalidate the organization data in its cache. In figure 8.1, if you look at where the organization service calls back into the licensing service to tell it to invalidate the Redis cache, you can see at least three problems:

- The organization and licensing services are tightly coupled.

- The coupling has introduced brittleness between the services. If the licensing service endpoint for invalidating the cache changes, the organization service has to change.

- The approach is inflexible because you can’t add new consumers of the organization data even without modifying the code on the organization service to know that it has called the other service to let it know about the change.

Tight coupling between services

In figure 8.1 you can see tight coupling between the licensing and the organization service. The licensing service always had a dependency on the organization service to retrieve data. However, by having the organization service directly communicate back to the licensing service whenever an organization record has been updated or deleted, you’ve introduced coupling back from the organization service to the licensing service. For the data in the Redis cache to be invalidated, the organization service either needs an endpoint on the licensing service exposed that can be called to invalidate its Redis cache, or the organization service has to talk directly to the Redis server owned by the licensing service to clear the data in it.

Having the organization service talk to Redis has its own problems because you’re talking to a data store owned directly by another service. In a microservice environment, this a big no-no. While one can argue that the organization data rightly belongs to the organization service, the licensing service is using it in a specific context and could be potentially transforming the data or have built business rules around it. Having the organization service talking directly to the Redis service can accidently break rules the team owning the licensing service has implemented.

Brittleness between the services

The tight coupling between the licensing service and the organization service has also introduced brittleness between the two services. If the licensing service is down or running slowly, the organization service can be impacted because the organization service is now communicating directly with the licensing service. Again, if you had the organization service talk directly to licensing service’s Redis data store, you’ve now created a dependency between the organization service and Redis. In this scenario, any problems with the shared Redis server now have the potential to take down both services.

Inflexible in adding new consumers to changes in the organization service

The last problem with this architecture is that it’s inflexible. With the model in figure 8.1, if you had another service that was interested in when the organization data changes, you’d need to add another call from the organization service to that other service. This means a code change and redeployment of the organization service. If you use the synchronous, request-response model for communicating state change, you start to see almost a web-like pattern of dependency between your core services in your application and other services. The centers of these webs become your major points of failure within your application.

While messaging adds a layer of indirection between your services, you can still introduce tight coupling between two services using messaging. Later in the chapter you’re going to send messages between the organization and licensing service. These messages are going to be serialized and de-serialized to a Java object using JSON as the transport protocol for the message. Changes to the structure of the JSON message can cause problems when converting back and forth to Java if the two services don’t gracefully handle different versions of the same message type. JSON doesn’t natively support versioning. However, you can use Apache Avro (https://avro.apache.org/) if you need versioning. Avro is a binary protocol that has versioning built into it. Spring Cloud Stream does support Apache Avro as a messaging protocol. However, using Avro is outside the scope of this book, but we did want to make you aware that it does help if you truly need to worry about message versioning.

8.1.2. Using messaging to communicate state changes between services

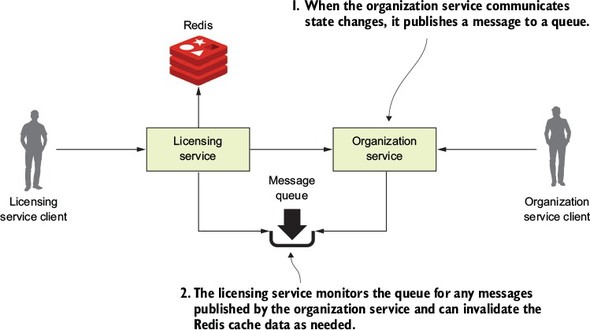

With a messaging approach, you’re going to inject a queue in between the licensing and organization service. This queue won’t be used to read data from the organization service, but will instead be used by the organization service to publish when any state changes within the organization data managed by the organization service occurs. Figure 8.2 demonstrates this approach.

Figure 8.2. As organization state changes, messages will be written to a message queue that sits between the two services.

In the model in figure 8.2, every time organization data changes, the organization service publishes a message out to a queue. The licensing service is monitoring the queue for messages and when a message comes in, clears the appropriate organization record out of the Redis cache. When it comes to communicating state, the message queue acts as an intermediary between the licensing and organization service. This approach offers four benefits:

- Loose coupling

- Durability

- Scalability

- Flexibility

Loose coupling

A microservices application can be composed of dozens of small and distributed services that have to interact with each other and are interested in the data managed by one another. As you saw with the synchronous design proposed earlier, a synchronous HTTP response creates a hard dependency between the licensing and organization service. We can’t eliminate these dependencies completely, but we can try to minimize dependencies by only exposing endpoints that directly manage the data owned by the service. A messaging approach allows you to decouple the two services because when it comes to communicating state changes, neither service knows about each other. When the organization service needs to publish a state change, it writes a message to a queue. The licensing service only knows that it gets a message; it has no idea who has published the message.

Durability

The presence of the queue allows you to guarantee that a message will be delivered even if the consumer of the service is down. The organization service can keep publishing messages even if the licensing service in unavailable. The messages will be stored in the queue and will stay there until the licensing service is available. Conversely, with the combination of a cache and the queuing approach, if the organization service is down, the licensing service can degrade gracefully because at least part of the organization data will be in its cache. Sometimes old data is better than no data.

Scalability

Since messages are stored in a queue, the sender of the message doesn’t have to wait for a response back from the consumer of the message. They can go on their way and continue their work. Likewise, if a consumer reading a message off the queue isn’t processing messages fast enough, it’s a trivial task to spin up more consumers and have them process those messages off the queue. This scalability approach fits well within a microservices model because one of the things I’ve been emphasizing through this book is that it should be trivial to spin up new instances of a microservice and have that additional microservice become another service that can process work off the message queue holding the messages. This is an example of scaling horizontally. Traditional scaling mechanisms for reading messages off a queue involved increasing the number of threads that a message consumer could process at one time. Unfortunately, with this approach, you were ultimately limited by the number of CPUs available to the message consumer. A microservice model doesn’t have this limitation because you’re scaling by increasing the number of machines hosting the service consuming the messages.

Flexibility

The sender of a message has no idea who is going to consume it. This means you can easily add new message consumers (and new functionality) without impacting the original sending service. This is an extremely powerful concept because new functionality can be added to an application without having to touch existing services. Instead, the new code can listen for events being published and react to them accordingly.

8.1.3. Downsides of a messaging architecture

Like any architectural model, a messaging-based architecture has tradeoffs. A messaging-based architecture can be complex and requires the development team to pay close attention to several key things, including

- Message handling semantics

- Message visibility

- Message choreography

Message handling semantics

Using messages in a microservice-based application requires more than understanding how to publish and consume messages. It requires you to understand how your application will behave based on the order messages are consumed and what happens if a message is processed out of order. For example, if you have strict requirements that all orders from a single customer must be processed in the order they are received, you’re going to have to set up and structure your message handling differently than if every message can be consumed independently of one another.

It also means that if you’re using messaging to enforce strict state transitions of your data, you need to think as you’re designing your application about scenarios where a message throws an exception, or an error is processed out of order. If a message fails, do you retry processing the error or do you let it fail? How do you handle future messages related to that customer if one of the customer messages fails? Again, these are all topics to think through.

Message visibility

Using messages in your microservices often means a mix of synchronous service calls and processing in services asynchronously. The asynchronous nature of messages means they might not be received or processed in close proximity to when the message is published or consumed. Also, having things like a correlation ID for tracking a user’s transactions across web service invocations and messages is critical to understanding and debugging what’s going on in your application. As you may remember from chapter 6, a correlation ID is a unique number that’s generated at the start of a user’s transaction and passed along with every service call. It should also be passed with every message that’s published and consumed.

Message choreography

As alluded to in the section on message visibility, messaging-based applications make it more difficult to reason through the business logic of their applications because their code is no longer being processed in a linear fashion with a simple block request-response model. Instead, debugging message-based applications can involve wading through the logs of several different services where the user transactions can be executed out of order and at different times.

The previous sections weren’t meant to scare you away from using messaging in your applications. Rather, my goal is to highlight that using messaging in your services requires forethought. I recently completed a major project where we needed to bring up and down a stateful set of AWS server instances for each one of our customers. We had to integrate a combination of microservice calls and messages using both AWS Simple Queueing Service (SQS) and Kafka. While the project was complex, I saw first-hand the power of messaging when at the end of the project we realized that we’d need to deal with having to make sure that we retrieved certain files off the server before the server could be terminated. This step had to be carried out about 75% of the way through the user workflow and the overall process couldn’t continue until the process was completed. Fortunately, we had a microservice (called our file recovery service) that could do much of the work to check and see if the files were off the server being decommissioned. Because the servers communicate all of their state changes (including that they’re being decommissioned) via events, we only had to plug the file recovery server into an event stream coming from the server being decommissioned and have them listen for a “decommissioning” event.

If this entire process had been synchronous, adding this file-draining step would have been extremely painful. But in the end, we needed an existing service we already had in production to listen to events coming off an existing messaging queue and react. The work was done in a couple of days and we never missed a beat in our project delivery. Messages allow you to hook together services without the services being hard-coded together in a code-based workflow.

8.2. Introducing Spring Cloud Stream

Spring Cloud makes it easy to integrate messaging into your Spring-based microservices. It does this through the Spring Cloud Stream project (https://cloud.spring.io/spring-cloud-stream/). The Spring Cloud Stream project is an annotation-driven framework that allows you to easily build message publishers and consumers in your Spring application.

Spring Cloud Stream also allows you to abstract away the implementation details of the messaging platform you’re using. Multiple message platforms can be used with Spring Cloud Stream (including the Apache Kafka project and RabbitMQ) and the implementation-specific details of the platform are kept out of the application code. The implementation of message publication and consumption in your application is done through platform-neutral Spring interfaces.

Note

For this chapter, you’re going to use a lightweight message bus called Kafka (https://kafka.apache.org/). Kafka is a lightweight, highly performant message bus that allows you asynchronously send streams of messages from one application to one or more other applications. Written in Java, Kafka has become the de facto message bus for many cloud-based applications because it’s highly reliable and scalable. Spring Cloud Stream also supports the use of RabbitMQ as a message bus. Both Kafka and RabbitMQ are strong messaging platforms, and I chose Kafka because that’s what I’m most familiar with.

To understand Spring Cloud Stream, let’s begin with a discussion of the Spring Cloud Stream architecture and familiarize ourselves with the terminology of Spring Cloud Stream. If you’ve never worked with a messaging based platform before, the new terminology involved can be somewhat overwhelming.

8.2.1. The Spring Cloud Stream architecture

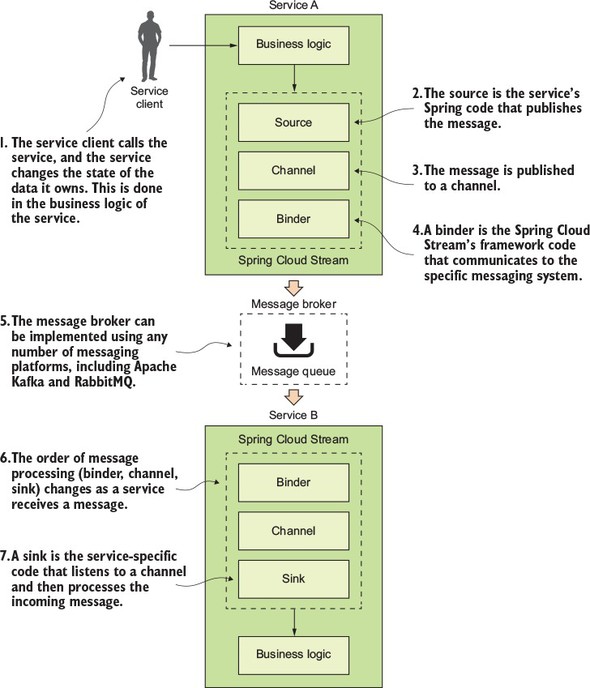

Let’s begin our discussion by looking at the Spring Cloud Stream architecture through the lens of two services communicating via messaging. One service will be the message publisher and one service will be the message consumer. Figure 8.3 shows how Spring Cloud Stream is used to facilitate this message passing.

Figure 8.3. As a message is published and consumed, it flows through a series of Spring Cloud Stream components that abstract away the underlying messaging platform.

With the publication and consumption of a message in Spring Cloud, four components are involved in publishing and consuming the message:

- Source

- Channel

- Binder

- Sink

Source

When a service gets ready to publish a message, it will publish the message using a source. A source is a Spring annotated interface that takes a Plain Old Java Object (POJO) that represents the message to be published. A source takes the message, serializes it (the default serialization is JSON), and publishes the message to a channel.

Channel

A channel is an abstraction over the queue that’s going to hold the message after it has been published by the message producer or consumed by a message consumer. A channel name is always associated with a target queue name. However, that queue name is never directly exposed to the code. Instead the channel name is used in the code, which means that you can switch the queues the channel reads or writes from by changing the application’s configuration, not the application’s code.

Binder

The binder is part of the Spring Cloud Stream framework. It’s the Spring code that talks to a specific message platform. The binder part of the Spring Cloud Stream framework allows you to work with messages without having to be exposed to platform--specific libraries and APIs for publishing and consuming messages.

Sink

In Spring Cloud Stream, when a service receives a message from a queue, it does it through a sink. A sink listens to a channel for incoming messages and de-serializes the message back into a plain old Java object. From there, the message can be processed by the business logic of the Spring service.

8.3. Writing a simple message producer and consumer

Now that we’ve walked through the basic components in Spring Cloud Stream, let’s look at a simple Spring Cloud Stream example. For the first example, you’re going to pass a message from your organization service to your licensing service. The only thing you’ll do with the message in the licensing service is to print a log message to the console.

In addition, because you’re only going to have one Spring Cloud Stream source (the message producer) and sink (message consumer) in this example, you’re going to start the example with a few simple Spring Cloud shortcuts that will make setting up the source in the organization service and a sink in the licensing service trivial.

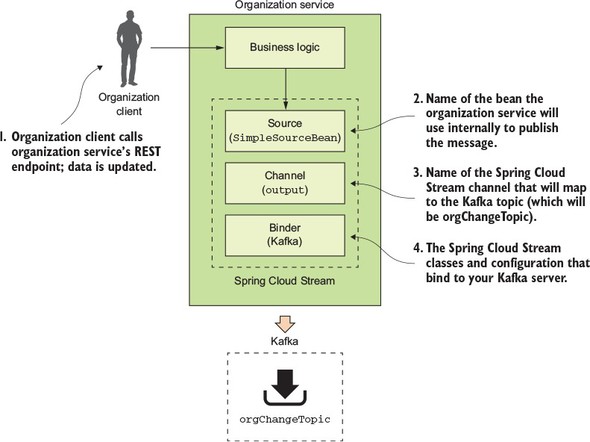

8.3.1. Writing the message producer in the organization service

You’re going to begin by modifying the organization service so that every time organization data is added, updated, or deleted, the organization service will publish a message to a Kafka topic indicating that the organization change event has occurred. Figure 8.4 highlights the message producer and build on the general Spring Cloud Stream architecture from figure 8.3.

Figure 8.4. When organization service data changes it will publish a message to Kafka.

The published message will include the organization ID associated with the change event and will also include what action occurred (Add, Update or Delete).

The first thing you need to do is set up your Maven dependencies in the organization service’s Maven pom.xml file. The pom.xml file can be found in the organization-service directory. In the pom.xml, you need to add two dependencies: one for the core Spring Cloud Stream libraries and the other to include the Spring Cloud Stream Kafka libraries:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-stream</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-starter-stream-kafka</artifactId>

</dependency>

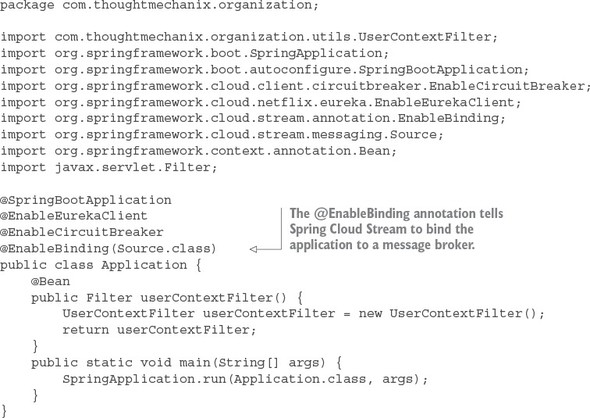

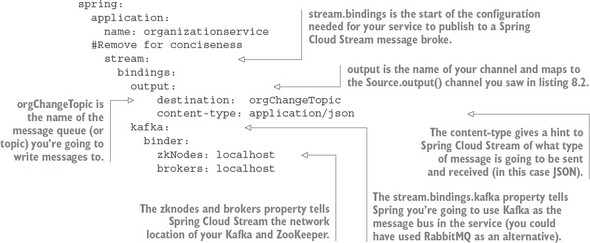

Once the Maven dependencies have been defined, you need to tell your application that it’s going to bind to a Spring Cloud Stream message broker. You do this by annotating the organization service’s bootstrap class organization-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/organization/Application.java with an @EnableBinding annotation. The following listing shows the organization service’s Application.java source code.

Listing 8.1. The annotated Application.java class

In listing 8.1, the @EnableBinding annotation tells Spring Cloud Stream that you want to bind the service to a message broker. The use of Source.class in the @EnableBinding annotation tells Spring Cloud Stream that this service will communicate with the message broker via a set of channels defined on the Source class. Remember, channels sit above a message queue. Spring Cloud Stream has a default set of channels that can be configured to speak to a message broker.

At this point you haven’t told Spring Cloud Stream what message broker you want the organization service to bind to. We’ll get to that shortly. Now, you can go ahead and implement the code that will publish a message.

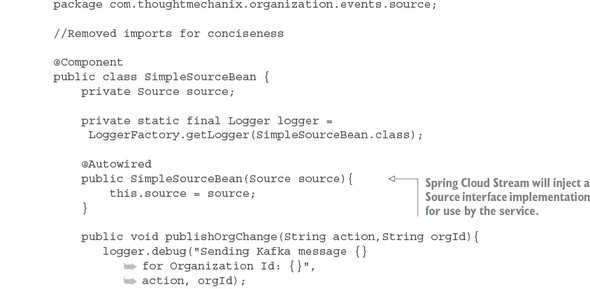

The message publication code can be found in the organization-service/src/com/thoughtmechanix/organization/events/source/SimpleSourceBean.java class. The following listing shows the code for this class.

Listing 8.2. Publishing a message to the message broker

In listing 8.2 you inject the Spring Cloud Source class into your code. Remember, all communication to a specific message topic occurs through a Spring Cloud Stream construct called a channel. A channel is represented by a Java interface class. In this listing you’re using the Source interface. The Source interface is a Spring Cloud defined interface that exposes a single method called output(). The Source interface is a convenient interface to use when your service only needs to publish to a single channel. The output() method returns a class of type MessageChannel. The MessageChannel is how you’ll send messages to the message broker. Later in this chapter, I’ll show you how to expose multiple messaging channels using a custom interface.

The actual publication of the message occurs in the publishOrgChange() method. This method builds a Java POJO called OrganizationChangeModel. I’m not going to put the code for the OrganizationChangeModel in the chapter because this class is nothing more than a POJO around three data elements:

- Action— This is the action that triggered the event. I’ve included the action in the message to give the message consumer more context on how it should process an event.

- Organization ID— This is the organization ID associated with the event.

- Correlation ID— This is the correlation ID the service call that triggered the event. You should always include a correlation ID in your events as it helps greatly with tracking and debugging the flow of messages through your services.

When you’re ready to publish the message, use the send() method on the MessageChannel class returned from the source.output() method.

source.output().send(MessageBuilder.withPayload(change).build());

The send() method takes a Spring Message class. You use a Spring helper class called MessageBuilder to take the contents of the OrganizationChangeModel class and convert it to a Spring Message class.

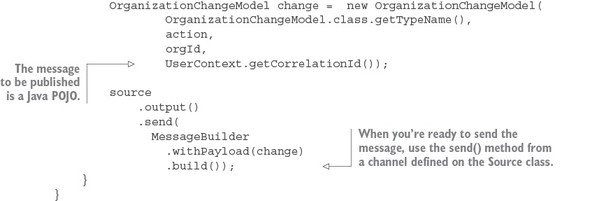

This all the code you need to send a message. However, at this point, everything should feel a little bit like magic because you haven’t seen how to bind your organization service to a specific message queue, let alone the actual message broker. This is all done through configuration. Listing 8.3 shows the configuration that does the mapping of your service’s Spring Cloud Stream Source to a Kafka message broker and a message topic in Kafka. This configuration information can be localized in your service’s application.yml file or inside a Spring Cloud Config entry for the service.

Listing 8.3. The Spring Cloud Stream configuration for publishing a message

The configuration in listing 8.3 looks dense, but it’s straightforward. The configuration property spring.stream.bindings.output in the listing maps the source.output() channel in listing 8.2 to the orgChangeTopic on the message broker you’re going to communicate with. It also tells Spring Cloud Stream that messages being sent to this topic should be serialized as JSON. Spring Cloud Stream can serialize messages in multiple formats, including JSON, XML, and the Apache Foundation’s Avro format (https://avro.apache.org/).

The configuration property, spring.stream.bindings.kafka in listing 8.3, also tells Spring Cloud Stream to bind the service to Kafka. The sub-properties tell Spring Cloud Stream the network addresses of the Kafka message brokers and the Apache ZooKeeper servers that run with Kafka.

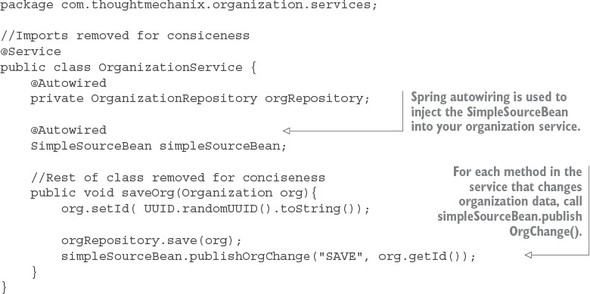

Now that you have the code written that will publish a message via Spring Cloud Stream and the configuration to tell Spring Cloud Stream that it’s going to use Kafka as a message broker, let’s look at where the publication of the message in your organization service actually occurs. This work will be done in the organization-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/organization/services/OrganizationService.java class. The following listing shows the code for this class.

Listing 8.4. Publishing a message in your organization service

One of the most common questions I get from teams when they’re first embarking on their message journey is exactly how much data should go in their messages. My answer is, it depends on your application. As you may notice, in all my examples I only return the organization ID of the organization record that has changed. I never put a copy of the changes to the data in the message. In my examples (and in many of the problems I deal with in the telephony space), the business logic being executed is sensitive to changes in data. I used messages based on system events to tell other services that data state has changed, but I always force the other services to go back to the master (the service that owns the data) to retrieve a new copy of the data. This approach is costlier in terms of execution time, but it also guarantees I always have the latest copy of the data to work with. A chance still exists that the data you’re working with could change right after you’ve read it from the source system, but that’s much less likely than blindly consuming the information right off the queue.

Think carefully about how much data you’re passing around. Sooner or later, you’ll run into a situation where the data you passed is stale. It could be stale because a problem caused it to sit in a message queue too long, or a previous message containing data failed, and the data you’re passing in the message now represents data that’s in an inconsistent state (because your application relied on the message’s state rather than the actual state in the underlying data store). If you’re going to pass state in your message, also make sure to include a date-time stamp or version number in your message so that the services consuming the data can inspect the data being passed and ensure that it’s not older than the copy of the data they already have. (Remember, data can be retrieved out of order.)

8.3.2. Writing the message consumer in the licensing service

At this point you’ve modified the organization service to publish a message to Kafka every time the organization service changes organization data. Anyone who’s interested can react without having to be explicitly called by the organization service. It also means you can easily add new functionality that can react to the changes in the organization service by having them listen to messages coming in on the message queue. Let’s now switch directions and look at how a service can consume a message using Spring Cloud Stream.

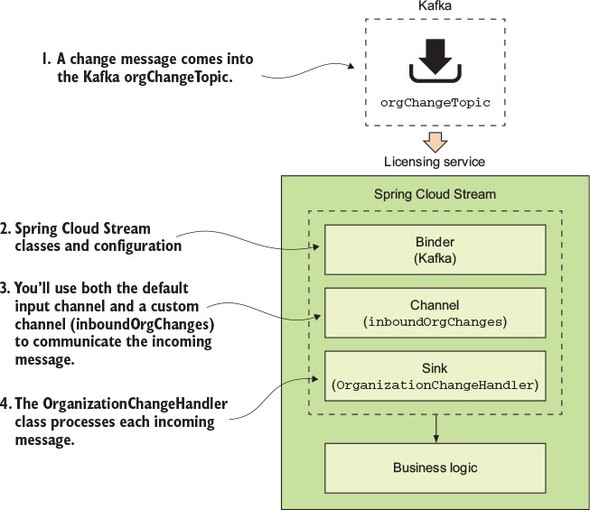

For this example, you’re going to have the licensing service consume the message published by the organization service. Figure 8.5 shows where the licensing service will fit into the Spring Cloud architecture first shown in figure 8.3.

Figure 8.5. When a message comes into the Kafka orgChangeTopic, the licensing service will respond.

To begin, you again need to add your Spring Cloud Stream dependencies to the licensing services pom.xml file. This pom.xml file can found in licensing-service directory of the source code for the book. Similar to the organization-service pom.xml file you saw earlier, you add the following two dependency entries:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-stream</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-starter-stream-kafka</artifactId>

</dependency>

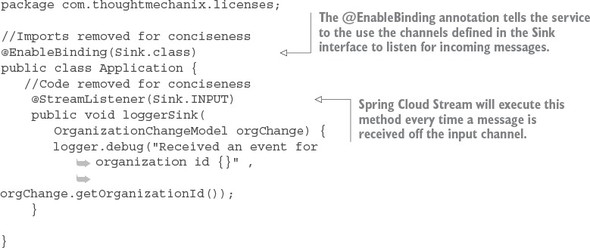

Then you need to tell the licensing service that it needs to use Spring Cloud Stream to bind to a message broker. Like the organization service, we’re going to annotate the licensing services bootstrap class (licensing-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/Application.java) with the @EnableBinding annotation. The difference between the licensing service and the organization service is the value you’re going to pass to the @EnableBinding annotation, as shown in the following listing.

Listing 8.5. Consuming a message using Spring Cloud Stream

Because the licensing service is a consumer of a message, you’re going to pass the @EnableBinding annotation the value Sink.class. This tells Spring Cloud Stream to bind to a message broker using the default Spring Sink interface. Similar to the Spring Cloud Steam Source interface described in section 8.3.1, Spring Cloud Stream exposes a default channel on the Sink interface. The channel on the Sink interface is called input and is used to listen for incoming messages on a channel.

Once you’ve defined that you want to listen for messages via the @EnableBinding annotation, you can write the code to process a message coming off the Sink input channel. To do this, use the Spring Cloud Stream @StreamListener annotation.

The @StreamListener annotation tells Spring Cloud Stream to execute the loggerSink() method every time a message is received off the input channel. Spring Cloud Stream will automatically de-serialize the message coming off the channel to a Java POJO called OrganizationChangeModel.

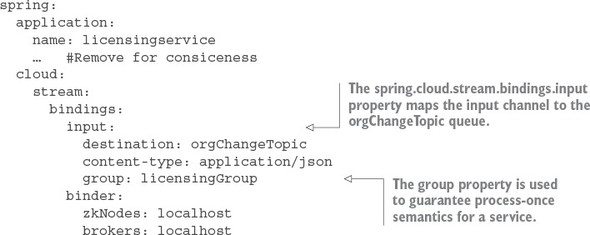

Once again, the actual mapping of the message broker’s topic to the input channel is done in the licensing service’s configuration. For the licensing service, its configuration is shown in the following listing and can be found in the licensing service’s licensing-service/src/main/resources/application.yml file.

Listing 8.6. Mapping the licensing service to a message topic in Kafka

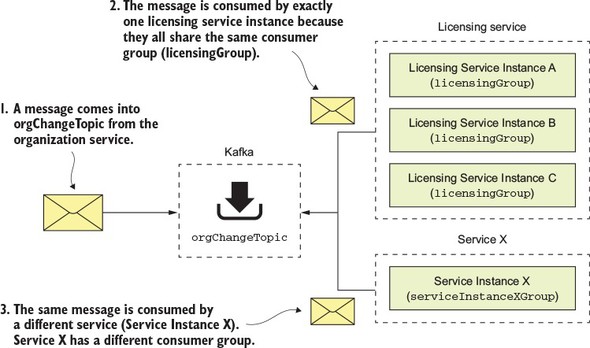

The configuration in this listing looks like the configuration for the organization service. It has, however, two key differences. First, you now have a channel called input defined under the spring.cloud.stream.bindings property. This value maps to the Sink.INPUT channel defined in the code from listing 8.5. This property maps the input channel to the orgChangeTopic. Second, you see the introduction of a new property called spring.cloud.stream.bindings.input.group. The group property defines the name of the consumer group that will be consuming the message.

The concept of a consumer group is this: You might have multiple services with each service having multiple instances listening to the same message queue. You want each unique service to process a copy of a message, but you only want one service instance within a group of service instances to consume and process a message. The group property identifies the consumer group that the service belongs to. As long as all the service instances have the same group name, Spring Cloud Stream and the underlying message broker will guarantee that only one copy of the message will be consumed by a service instance belonging to that group. In the case of your licensing service, the group property value will be called licensingGroup.

Figure 8.6 illustrates how the consumer group is used to help enforce consume-once semantics for a message being consumed across multiple services.

Figure 8.6. The consumer group guarantees a message will only be processed once by a group of service instances.

8.3.3. Seeing the message service in action

At this point you have the organization service publishing a message to the org-Change-Topic every time a record is added, updated, or deleted and the licensing service receiving the message of the same topic. Now you’ll see this code in action by updating an organization service record and watching the console to see the corresponding log message appear from the licensing service.

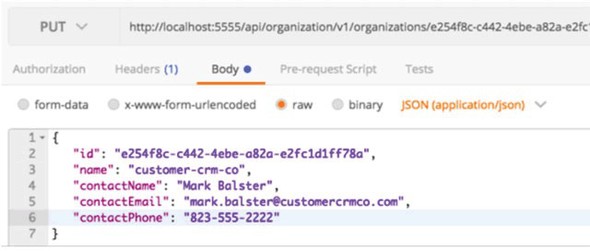

To update the organization service record, you’re going to issue a PUT on the organization service to update the organization’s contact phone number. The endpoint you’re going to update with is http://localhost:5555/api/organization/v1/organizations/e254f8c-c442-4ebe-a82a-e2fc1d1ff78a. The body you’re going to send on the PUT call to the endpoint is

{

"contactEmail": "mark.balster@custcrmco.com",

"contactName": "Mark Balster",

"contactPhone": "823-555-2222",

"id": "e254f8c-c442-4ebe-a82a-e2fc1d1ff78a",

"name": "customer-crm-co"

}

Figure 8.7 shows the returned output from this PUT call.

Figure 8.7. Updating the contact phone number using the organization service

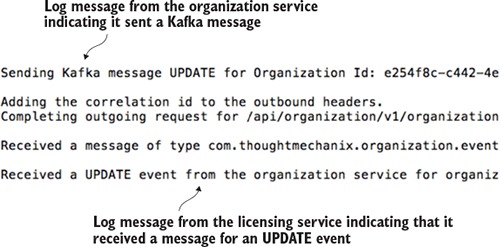

Once the organization service call has been made, you should see the following output in the console window running the services. Figure 8.8 show this output.

Figure 8.8. The console shows the message from the organization service being sent and then received.

Now you have two services communicating with each other using messaging. Spring Cloud Stream is acting as the middleman for these services. From a messaging perspective, the services know nothing about each other. They’re using a messaging broker to communicate as an intermediary and Spring Cloud Stream as an abstraction layer over the messaging broker.

8.4. A Spring Cloud Stream use case: distributed caching

At this point you have two services communicating with messaging, but you’re not really doing anything with the messages. Now you’ll build the distributed caching example we discussed earlier in the chapter. You’ll have the licensing service always check a distributed Redis cache for the organization data associated with a particular license. If the organization data exists in the cache, you’ll return the data from the cache. If it doesn’t, you’ll call the organization service and cache the results of the call in a Redis hash.

When data is updated in the organization service, the organization service will issue a message to Kafka. The licensing service will pick up the message and issue a delete against Redis to clear out the cache.

Using Redis as a distributed cache is very relevant to microservices development in the cloud. With my current employer, we build our solution using Amazon’s Web Services (AWS) and are a heavy user of Amazon’s DynamoDB. We also use Amazon’s ElastiCache (Redis) to

- Improve performance for lookup of commonly held data— By using a cache, we’ve significantly improved the performance of several of our key services. All the tables in the products we sell are multi-tenant (hold multiple customer records in a single table), which means they can be quite large. Because caching tends to pin “heavily” used data we’ve seen significant performance improvements by using Redis and caching to avoid the reads out to Dynamo.

- Reduce the load (and cost) on the Dynamo tables holding our data— Accessing data in Dynamo can be a costly proposition. Every read you make is a chargeable event. Using a Redis server is significantly cheaper for reads by a primary key then a Dynamo read.

- Increase resiliency so that our services can degrade gracefully if our primary data store (Dynamo) is having performance problems— If AWS Dynamo is having problems (it does occasionally happen), using a cache such as Redis can help your service degrade gracefully. Depending on how much data you keep in your cache, a caching solution can help reduce the number of errors you get from hitting your data store.

Redis is far more than a caching solution, but it can fill that role if you need a distributed cache.

8.4.1. Using Redis to cache lookups

Now you’re going to begin by setting up the licensing service to use Redis. Fortunately, Spring Data already makes it simple to introduce Redis into your licensing service. To use Redis in the licensing service you need to do four things:

- Configure the licensing service to include the Spring Data Redis dependencies

- Construct a database connection to Redis

- Define the Spring Data Redis Repositories that your code will use to interact with a Redis hash

- Use Redis and the licensing service to store and read organization data

Configure the licensing service with Spring Data Redis dependencies

The first thing you need to do is include the spring-data-redis dependencies, along with the jedis and common-pools2 dependencies, into the licensing service’s pom.xml file. The dependencies to include are shown in the following listing.

Listing 8.7. Adding the Spring Redis Dependencies

<dependency> <groupId>org.springframework.data</groupId> <artifactId>spring-data-redis</artifactId> <version>1.7.4.RELEASE</version> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>redis.clients</groupId> <artifactId>jedis</artifactId> <version>2.9.0</version> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>org.apache.commons</groupId> <artifactId>commons-pool2</artifactId> <version>2.0</version> </dependency>

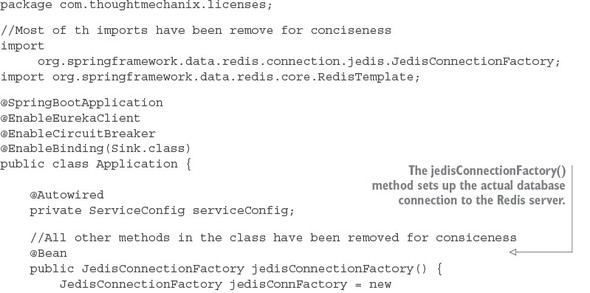

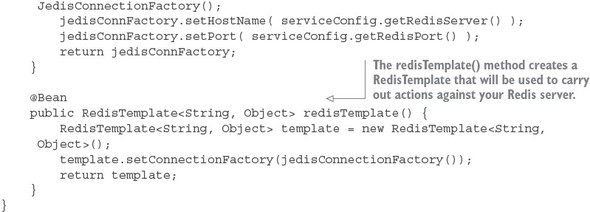

Constructing the database connection to a Redis server

Now that you have the dependencies in Maven, you need to establish a connection out to your Redis server. Spring uses the open source project Jedis (https://github.com/xetorthio/jedis) to communicate with a Redis server. To communicate with a specific Redis instance, you’re going to expose a JedisConnection-Factory in the licensing-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/Application.java class as a Spring Bean. Once you have a connection out to Redis, you’re going to use that connection to create a Spring RedisTemplate object. The RedisTemplate object will be used by the Spring Data repository classes that you’ll implement shortly to execute the queries and saves of organization service data to your Redis service. The following listing shows this code.

Listing 8.8. Establishing how your licensing service will communicate with Redis

The foundational work for setting up the licensing service to communicate with Redis is complete. Let’s now move over to writing the logic that will get, add, update, and delete data from Redis.

Defining the Spring Data Redis repositories

Redis is a key-value store data store that acts like a big, distributed, in-memory HashMap. In the simplest case, it stores data and looks up data by a key. It doesn’t have any kind of sophisticated query language to retrieve data. Its simplicity is its strength and one of the reasons why so many projects have adopted it for use in their projects.

Because you’re using Spring Data to access your Redis store, you need to define a repository class. As may you remember from early on in chapter 2, Spring Data uses user-defined repository classes to provide a simple mechanism for a Java class to access your Postgres database without having to write low-level SQL queries.

For the licensing service, you’re going to define two files for your Redis repository. The first file you’ll write will be a Java interface that’s going to be injected into any of the licensing service classes that are going to need to access Redis. This inter- face (licensing-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/repository/OrganizationRedisRepository.java) is shown in the following listing.

Listing 8.9. OrganizationRedisRepository defines methods used to call Redis

package com.thoughtmechanix.licenses.repository;

import com.thoughtmechanix.licenses.model.Organization;

public interface OrganizationRedisRepository {

void saveOrganization(Organization org);

void updateOrganization(Organization org);

void deleteOrganization(String organizationId);

Organization findOrganization(String organizationId);

}

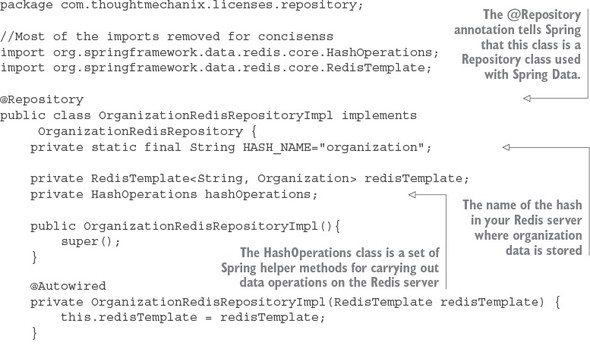

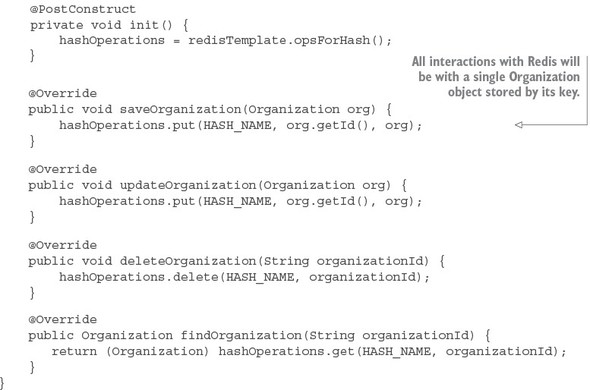

The second file is the implementation of the OrganizationRedisRepository interface. The implementation of the interface, the licensing-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/repository/OrganizationRedisRepositoryImpl.java class, uses the RedisTemplate Spring bean you declared earlier in listing 8.8 to interact with the Redis server and carry out actions against the Redis server. The next listing shows this code in use.

Listing 8.10. The OrganizationRedisRepositoryImpl implementation

The OrganizationRedisRepositoryImpl contains all the CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) logic used for storing and retrieving data from Redis. There are two key things to note from the code in listing 8.10:

- All data in Redis is stored and retrieved by a key. Because you’re storing data retrieved from the organization service, organization ID is the natural choice for the key being used to store an organization record.

- The second thing to note in is that a Redis server can contain multiple hashes and data structures within it. In every operation against the Redis server, you need to tell Redis the name of the data structure you’re performing the operation against. In listing 8.10, the data structure name you’re using is stored in the HASH_NAME constant and is called “organization.”

Using Redis and the licensing service to store and read organization data

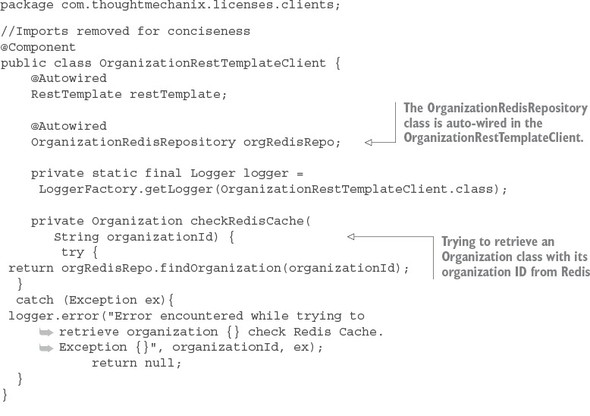

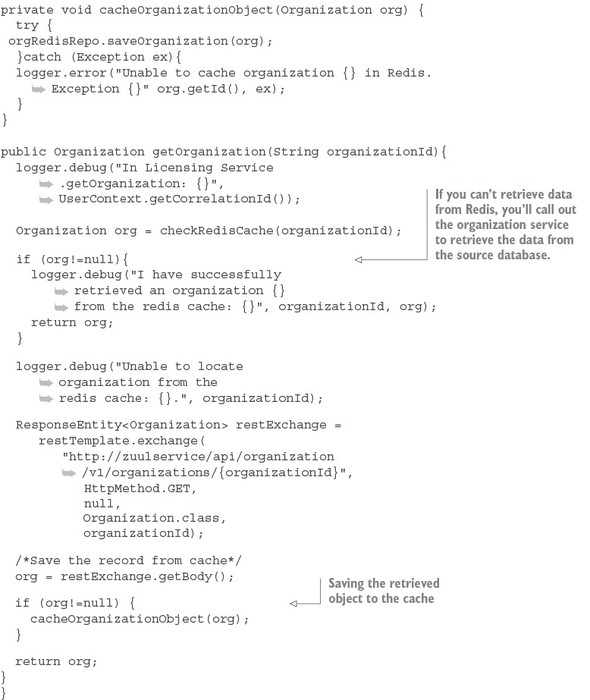

Now that you have the code in place to perform operations against Redis, you can modify your licensing service so that every time the licensing service needs the organization data, it will check the Redis cache before calling out to the organization service. The logic for checking Redis will occur in the licensing-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/clients/OrganizationRestTemplate Client.java class. The code for this class is shown in the following listing.

Listing 8.11. OrganizationRestTemplateClient class will implement cache logic

The getOrganization() method is where the call to the organization service takes place. Before you make the actual REST call, you attempt to retrieve the Organization object associated with the call from Redis using the checkRedisCache() method. If the organization object in question is not in Redis, the code will return a null value. If a null value is returned from the checkRedisCache() method, the code will invoke the organization service’s REST endpoint to retrieve the desired organization record. If the organization service returns an organization, the returned organization object will be cached using the cacheOrganizationObject() method.

Note

Pay close attention to exception handling when interacting with the cache. To increase resiliency, we never let the entire call fail if we cannot communicate with the Redis server. Instead, we log the exception and let the call go out to the organization service. In this particular use case, caching is meant to help improve performance and the absence of the caching server shouldn’t impact the success of the call.

With the Redis caching code in place, you should hit the licensing service (yes, you only have two services, but you have a lot of infrastructure) and see the logging messages in listing 8.10. If you were to do two back-to-back GET requests on the following licensing service endpoint, http://localhost:5555/api/licensing/v1/organizations/e254f8c-c442-4ebe-a82a-e2fc1d1ff78a/licenses/f3831f8c-c338-4ebe-a82a-e2fc1d1ff78a, you should see the following two output statements in your logs:

licensingservice_1 | 2016-10-26 09:10:18.455 DEBUG 28 --- [nio-8080-exec-

1] c.t.l.c.OrganizationRestTemplateClient : Unable to locate

organization from the redis cache: e254f8c-c442-4ebe-a82a-e2fc1d1ff78a.

licensingservice_1 | 2016-10-26 09:10:31.602 DEBUG 28 --- [nio-8080-exec-

2] c.t.l.c.OrganizationRestTemplateClient : I have successfully

retrieved an organization e254f8c-c442-4ebe-a82a-e2fc1d1ff78a from the

redis cache: com.thoughtmechanix.licenses.model.Organization@6d20d301

The first line from the console shows the first time you tried to hit the licensing service endpoint for organization e254f8c-c442-4ebe-a82a-e2fc1d1ff78a. The licensing service first checked the Redis cache and couldn’t find the organization record it was looking for. The code then calls the organization service to retrieve the data. The second line that was printed from the console shows that when you hit the licensing service endpoint a second time, the organization record is now cached.

8.4.2. Defining custom channels

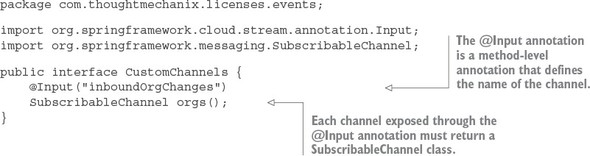

Previously you built your messaging integration between the licensing and organization services to use the default output and input channels that come packaged with the Source and Sink interfaces in the Spring Cloud Stream project. However, if you want to define more than one channel for your application or you want to customize the names of your channels, you can define your own interface and expose as many input and output channels as your application needs.

To create a custom channel, call inboundOrgChanges in the licensing service. You can define the channel in the licensing-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/events/CustomChannels.java interface, as shown in the following listing.

Listing 8.12. Defining a custom input channel for the licensing service

The key takeaway from listing 8.12 is that for each custom input channel you want to expose, you mark a method that returns a SubscribableChannel class with the @Input annotation. If you want to define output channels for publishing messages, you’d use the @OutputChannel above the method that will be called. In the case of an output channel, the defined method will return a MessageChannel class instead of the SubscribableChannel class used with the input channel:

@OutputChannel("outboundOrg")

MessageChannel outboundOrg();

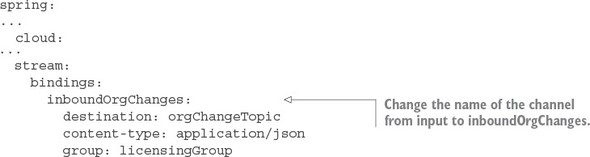

Now that you have a custom input channel defined, you need to modify two more things to use it in the licensing service. First, you need to modify the licensing service to map your custom input channel name to your Kafka topic. The following listing shows this.

Listing 8.13. Modifying the licensing service to use your custom input channel

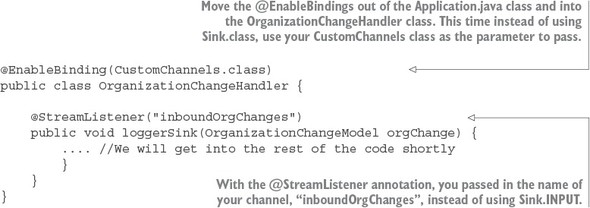

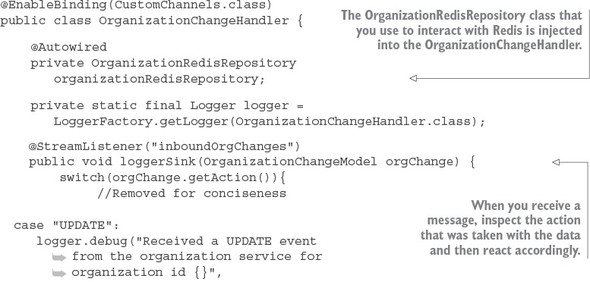

To use your custom input channel, you need to inject the CustomChannels interface you defined into a class that’s going to use it to process messages. For the distributed caching example, I’ve moved the code for handling an incoming message to the following licensing-service class: licensing-service/src/main/java/com/-thoughtmechanix/licenses/events/handlers/OrganizationChange Handler.java. The following listing shows the message handling code that you’ll use with the inboundOrgChanges channel you defined.

Listing 8.14. Using the new custom channel in the OrganizationChangeHandler

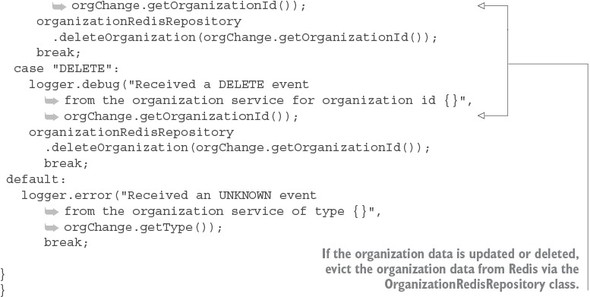

8.4.3. Bringing it all together: clearing the cache when a message is received

At this point you don’t need to do anything with the organization service. The service is all set up to publish a message whenever an organization is added, updated, or deleted. All you have to do is build out the OrganizationChangeHandler class from listing 8.14. The following listing shows the full implementation of this class.

Listing 8.15. Processing an organization change in the licensing service

8.5. Summary

- Asynchronous communication with messaging is a critical part of microservices architecture.

- Using messaging within your applications allows your services to scale and become more fault tolerant.

- Spring Cloud Stream simplifies the production and consumption of messages by using simple annotations and abstracting away platform-specific details of the underlying message platform.

- A Spring Cloud Stream message source is an annotated Java method that’s used to publish messages to a message broker’s queue.

- A Spring Cloud Stream message sink is an annotated Java method that receives messages off a message broker’s queue.

- Redis is a key-value store that can be used as both a database and cache.