Chapter 1. Welcome to the cloud, Spring

- Understanding microservices and why companies use them

- Using Spring, Spring Boot, and Spring Cloud for building microservices

- Learning why the cloud and microservices are relevant to microservice-based applications

- Building microservices involves more than building service code

- Understanding the parts of cloud-based development

- Using Spring Boot and Spring Cloud in microservice development

The one constant in the field of software development is that we as software developers sit in the middle of a sea of chaos and change. We all feel the churn as new technologies and approaches appear suddenly on the scene, causing us to reevaluate how we build and deliver solutions for our customers. One example of this churn is the rapid adoption by many organizations of building applications using microservices. Microservices are distributed, loosely coupled software services that carry out a small number of well-defined tasks.

This book introduces you to the microservice architecture and why you should consider building your applications with them. We’re going to look at how to build microservices using Java and two Spring framework projects: Spring Boot and Spring Cloud. If you’re a Java developer, Spring Boot and Spring Cloud will provide an easy migration path from building traditional, monolithic Spring applications to microservice applications that can be deployed to the cloud.

1.1. What’s a microservice?

Before the concept of microservices evolved, most web-based applications were built using a monolithic architectural style. In a monolithic architecture, an application is delivered as a single deployable software artifact. All the UI (user interface), business, and database access logic are packaged together into a single application artifact and deployed to an application server.

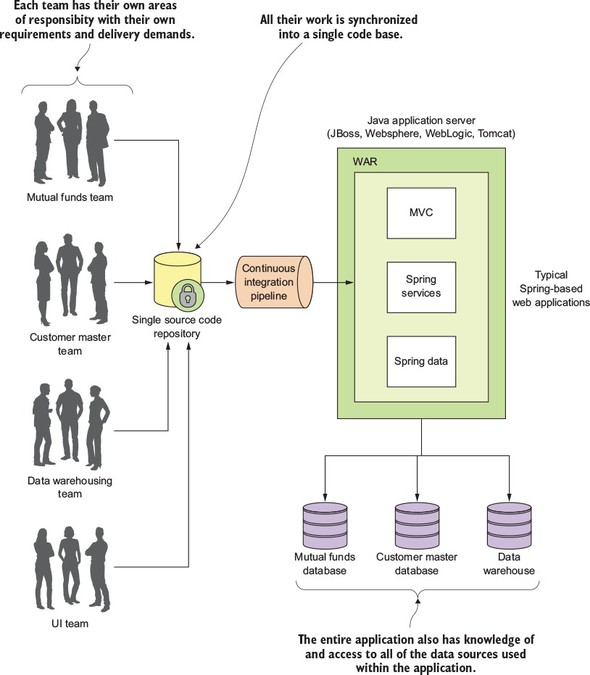

While an application might be a deployed as a single unit of work, most of the time there will be multiple development teams working on the application. Each development team will have their own discrete pieces of the application they’re responsible for and oftentimes specific customers they’re serving with their functional piece. For example, when I worked at a large financial services company, we had an in-house, custom-built customer relations management (CRM) application that involved the coordination of multiple teams including the UI, the customer master, the data warehouse, and the mutual funds team. Figure 1.1 illustrates the basic architecture of this application.

Figure 1.1. Monolithic applications force multiple development teams to artificially synchronize their delivery because their code needs to be built, tested, and deployed as an entire unit.

The problem here is that as the size and complexity of the monolithic CRM application grew, the communication and coordination costs of the individual teams working on the application didn’t scale. Every time an individual team needed to make a change, the entire application had to be rebuilt, retested and redeployed.

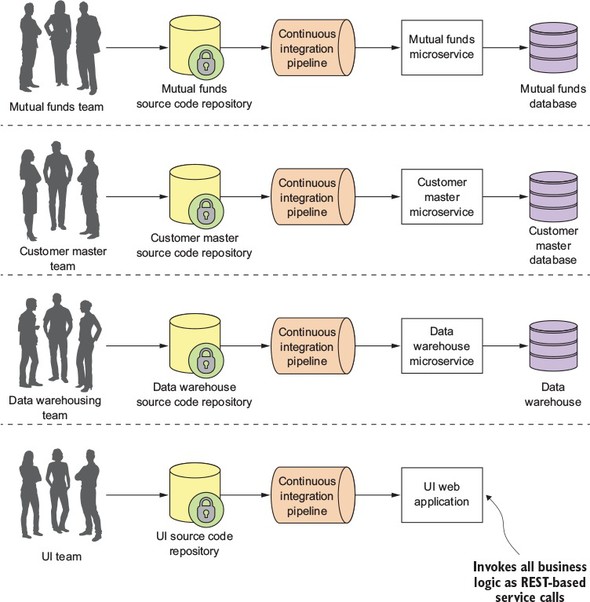

The concept of a microservice originally crept into the software development community’s consciousness around 2014 and was a direct response to many of the challenges of trying to scale both technically and organizationally large, monolithic applications. Remember, a microservice is a small, loosely coupled, distributed service. Microservices allow you to take a large application and decompose it into easy-to--manage components with narrowly defined responsibilities. Microservices help combat the traditional problems of complexity in a large code base by decomposing the large code base down into small, well-defined pieces. The key concept you need to embrace as you think about microservices is decomposing and unbundling the functionality of your applications so they’re completely independent of one another. If we take the CRM application we saw in figure 1.1 and decompose it into microservices, it might look like what’s shown in figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2. Using a microservice architecture our CRM application would be decomposed into a set of microservices completely independent of each other, allowing each development team to move at their own pace.

Looking at figure 1.2, you can see that each functional team completely owns their service code and service infrastructure. They can build, deploy, and test independently of each other because their code, source control repository, and the infrastructure (app server and database) are now completely independent of the other parts of the application.

A microservice architecture has the following characteristics:

- Application logic is broken down into small-grained components with well-defined boundaries of responsibility that coordinate to deliver a solution.

- Each component has a small domain of responsibility and is deployed completely independently of one another. Microservices should have responsibility for a single part of a business domain. Also, a microservice should be reusable across multiple applications.

- Microservices communicate based on a few basic principles (notice I said principles, not standards) and employ lightweight communication protocols such as HTTP and JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) for exchanging data between the service consumer and service provider.

- The underlying technical implementation of the service is irrelevant because the applications always communicate with a technology-neutral protocol (JSON is the most common). This means an application built using a microservice application could be built with multiple languages and technologies.

- Microservices—by their small, independent, and distributed nature—allow organizations to have small development teams with well-defined areas of responsibility. These teams might work toward a single goal such as delivering an application, but each team is responsible only for the services on which they’re working.

I often joke with my colleagues that microservices are the gateway drug for building cloud applications. You start building microservices because they give you a high degree of flexibility and autonomy with your development teams, but you and your team quickly find that the small, independent nature of microservices makes them easily deployable to the cloud. Once the services are in the cloud, their small size makes it easy to start up large numbers of instances of the same service, and suddenly your applications become more scalable and, with forethought, more resilient.

1.2. What is Spring and why is it relevant to microservices?

Spring has become the de facto development framework for building Java-based applications. At its core, Spring is based on the concept of dependency injection. In a normal Java application, the application is decomposed into classes where each class often has explicit linkages to other classes in the application. The linkages are the invocation of a class constructor directly in the code. Once the code is compiled, these linkage points can’t be changed.

This is problematic in a large project because these external linkages are brittle and making a change can result in multiple downstream impacts to other code. A dependency injection framework, such as Spring, allows you to more easily manage large Java projects by externalizing the relationship between objects within your application through convention (and annotations) rather than those objects having hard-coded knowledge about each other. Spring sits as an intermediary between the different Java classes of your application and manages their dependencies. Spring essentially lets you assemble your code together like a set of Lego bricks that snap together.

Spring’s rapid inclusion of features drove its utility, and the framework quickly became a lighter weight alternative for enterprise application Java developers looking for a way to building applications using the J2EE stack. The J2EE stack, while powerful, was considered by many to be bloatware, with many features that were never used by application development teams. Further, a J2EE application forced you to use a full-blown (and heavy) Java application server to deploy your applications.

What’s amazing about the Spring framework and a testament to its development community is its ability to stay relevant and reinvent itself. The Spring development team quickly saw that many development teams were moving away from monolithic applications where the application’s presentation, business, and data access logic were packaged together and deployed as a single artifact. Instead, teams were moving to highly distributed models where services were being built as small, distributed services that could be easily deployed to the cloud. In response to this shift, the Spring development team launched two projects: Spring Boot and Spring Cloud.

Spring Boot is a re-envisioning of the Spring framework. While it embraces core features of Spring, Spring Boot strips away many of the “enterprise” features found in Spring and instead delivers a framework geared toward Java-based, REST-oriented (Representational State Transfer)[1] microservices. With a few simple annotations, a Java developer can quickly build a REST microservice that can be packaged and deployed without the need for an external application container.

While we cover REST later in chapter 2, it’s worthwhile to read Roy Fielding’s PHD dissertation on building REST-based applications (http://www.ics.uci.edu/~fielding/pubs/dissertation/top.htm). It’s still one of the best explanations of REST available.

Note

While we cover REST in more detail in chapter 2, the core concept behind REST is that your services should embrace the use of the HTTP verbs (GET, POST, PUT, and DELETE) to represent the core actions of the service and use a lightweight web-oriented data serialization protocol, such as JSON, for requesting and receiving data from the service.

Because microservices have become one of the more common architectural patterns for building cloud-based applications, the Spring development community has given us Spring Cloud. The Spring Cloud framework makes it simple to operationalize and deploy microservices to a private or public cloud. Spring Cloud wraps several popular cloud-management microservice frameworks under a common framework and makes the use and deployment of these technologies as easy to use as annotating your code. I cover the different components within Spring Cloud later in this chapter.

1.3. What you’ll learn in this book

This book is about building microservice-based applications using Spring Boot and Spring Cloud that can be deployed to a private cloud run by your company or a public cloud such as Amazon, Google, or Pivotal. With this book, we cover with hands-on examples

- What a microservice is and the design considerations that go into building a microservice-based application

- When you shouldn’t build a microservice-based application

- How to build microservices using the Spring Boot framework

- The core operational patterns that need to be in place to support microservice applications, particularly a cloud-based application

- How you can use Spring Cloud to implement these operational patterns

- How to take what you’ve learned and build a deployment pipeline that can be used to deploy your services to a private, internally managed cloud or a public cloud provider

By the time you’re done reading this book, you should have the knowledge needed to build and deploy a Spring Boot-based microservice. You’ll also understand the key design decisions need to operationalize your microservices. You’ll understand how service configuration management, service discovery, messaging, logging and tracing, and security all fit together to deliver a robust microservices environment. Finally, you’ll see how your microservices can be deployed within a private or public cloud.

1.4. Why is this book relevant to you?

If you’ve gotten this far into reading chapter 1, I suspect that

- You’re a Java developer.

- You have a background in Spring.

- You’re interested in learning how to build microservice-based applications.

- You’re interested in how to use microservices to build cloud-based applications.

- You want to know if Java and Spring are relevant technologies for building microservice-based applications.

- You’re interested in seeing what goes into deploying a microservice-based application to the cloud.

I chose to write this book for two reasons. First, while I’ve seen many good books on the conceptual aspects of microservices, I couldn’t a find a good Java-based book on implementing microservices. While I’ve always considered myself a programming language polyglot (someone who knows and speaks several languages), Java is my core development language and Spring has been the development framework I “reach” for whenever I build a new application. When I first came across Spring Boot and Spring Cloud, I was blown away. Spring Boot and Spring Cloud greatly simplified my development life when it came to building microservice-based applications running in the cloud.

Second, as I’ve worked throughout my career as both an architect and engineer, I’ve found that many times the technology books that I purchase have tended to go to one of two extremes. They are either conceptual without concrete code examples, or are mechanical overviews of a particular framework or programming language. I wanted a book that would be a good bridge and middle ground between the architecture and engineering disciplines. As you read this book, I want to give you a solid introduction to the microservice patterns development and how they’re used in real-world application development, and then back these patterns up with practical and easy-to-understand code examples using Spring Boot and Spring Cloud.

Let’s shift gears for a moment and walk through building a simple microservice using Spring Boot.

1.5. Building a microservice with Spring Boot

I’ve always had the opinion that a software development framework is well thought out and easy to use if it passes what I affectionately call the “Carnell Monkey Test.” If a monkey like me (the author) can figure out a framework in 10 minutes or less, it has promise. That’s how I felt the first time I wrote a sample Spring Boot service. I want you to have to the same experience and joy, so let’s take a minute to see how to write a simple “Hello World” REST-service using Spring Boot.

In this section, we’re not going to do a detailed walkthrough of much of the code presented. Our goal is to give you a taste of writing a Spring Boot service. We’ll go into much more detail in chapter 2.

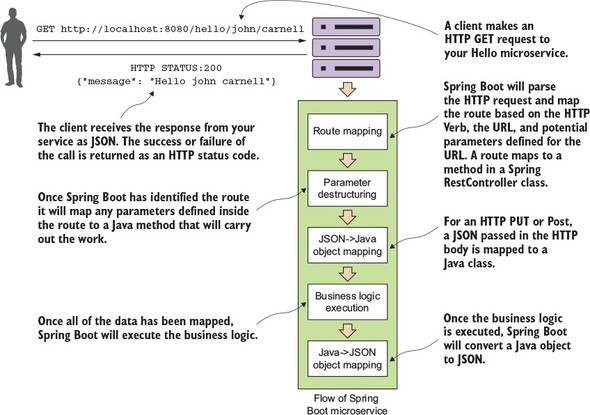

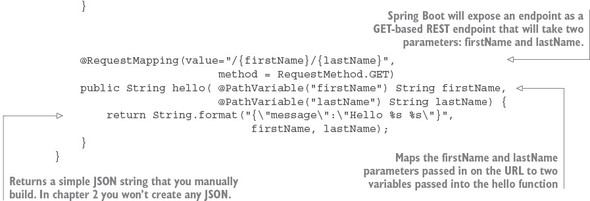

Figure 1.3 shows what your service is going to do and the general flow of how Spring Boot microservice will process a user’s request.

Figure 1.3. Spring Boot abstracts away the common REST microservice task (routing to business logic, parsing HTTP parameters from the URL, mapping JSON to/from Java Objects), and lets the developer focus on the business logic for the service.

This example is by no means exhaustive or even illustrative of how you should build a production-level microservice, but it should cause you to take a pause because of how little code it took to write it. We’re not going to go through how to set up the project build files or the details of the code until chapter 2. If you’d like to see the Maven pom.xml file and the actual code, you can find it in the chapter 1 section of the downloadable code. All the source code for chapter 1 can be retrieved from the GitHub repository for the book at https://github.com/carnellj/spmia-chapter1.

Note

Please make sure you read appendix A before you try to run the code examples for the chapters in this book. Appendix A covers the general pro-ject layout of all the projects in the book, how to run the build scripts, and how to fire up the Docker environment. The code examples in this chapter are simple and designed to be run natively right from your desktop without the information in additional chapters. However, in later chapters you’ll quickly begin using Docker to run all the services and infrastructure used in this book. Don’t go too far into the book without reading appendix A on setting up your desktop environment.

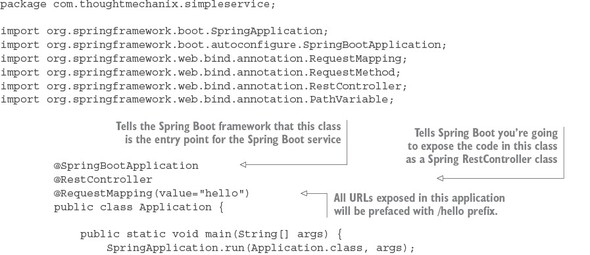

For this example, you’re going to have a single Java class called simpleservice/src/com/thoughtmechanix/application/simpleservice/Application.java that will be used to expose a REST endpoint called /hello.

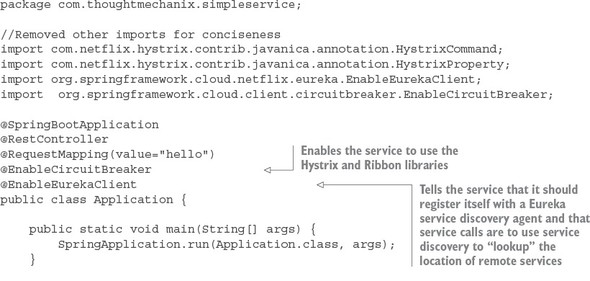

The following listing shows the code for Application.java.

Listing 1.1. Hello World with Spring Boot: a simple Spring microservice

In listing 1.1 you’re basically exposing a single GET HTTP endpoint that will take two parameters (firstName and lastName) on the URL and then return a simple JSON string that has a payload containing the message “Hello firstName lastName”. If you were to call the endpoint /hello/john/carnell on your service (which I’ll show shortly) the return of the call would be

{"message":"Hello john carnell"}

Let’s fire up your service. To do this, go to the command prompt and issue the following command:

mvn spring-boot:run

This command, mvn, will use a Spring Boot plug-in to start the application using an embedded Tomcat server.

The Spring Boot framework has strong support for both Java and the Groovy programming languages. You can build microservices with Groovy and no project setup. Spring Boot also supports both Maven and the Gradle build tools. I’ve limited the examples in this book to Java and Maven. As a long-time Groovy and Gradle aficionado, I have a healthy respect for the language and the build tool, but to keep the book manageable and the material focused, I’ve chosen to go with Java and Maven to reach the largest audience possible.

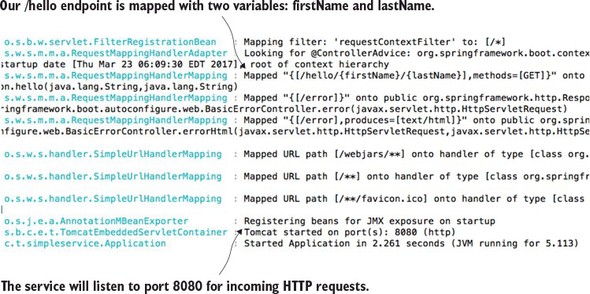

If everything starts correctly, you should see what’s shown in figure 1.4 from your command-line window.

Figure 1.4. Your Spring Boot service will communicate the endpoints exposed and the port of the service via the console.

If you examine the screen in figure 1.4, you’ll notice two things. First, a Tomcat server was started on port 8080. Second, a GET endpoint of /hello/{firstName}/{lastName} is exposed on the server.

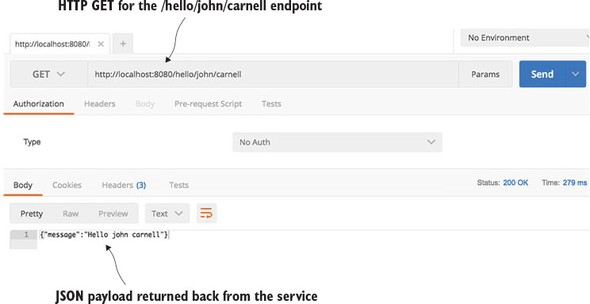

You’re going to call your service using a browser-based REST tool called POSTMAN (https://www.getpostman.com/). Many tools, both graphical and command line, are available for invoking a REST-based service, but I’ll use POSTMAN for all my examples in this book. Figure 1.5 shows the POSTMAN call to the http://localhost:8080/hello/john/carnell endpoint and the results returned from the service.

Figure 1.5. The response from the /hello endpoint shows the data you’ve requested represented as a JSON payload.

Obviously, this simple example doesn’t demonstrate the full power of Spring Boot. But what it should show is that you can write a full HTTP JSON REST-based service with route-mapping of URL and parameters in Java with as few as 25 lines of code. As any experienced Java developer will tell you, writing anything meaningful in 25 lines of code in Java is extremely difficult. Java, while being a powerful language, has acquired a reputation of being wordy compared to other languages.

We’re done with our brief tour of Spring Boot. We now have to ask this question: because we can write our applications using a microservice approach, does this mean we should? In the next section, we’ll walk through why and when a microservice approach is justified for building your applications.

1.6. Why change the way we build applications?

We’re at an inflection point in history. Almost all aspects of modern society are now wired together via the internet. Companies that used to serve local markets are suddenly finding that they can reach out to a global customer base. However, with a larger global customer base also comes global competition. These competitive pressures mean the following forces are impacting the way developers have to think about building applications:

- Complexity has gone way up— Customers expect that all parts of an organization know who they are. “Siloed” applications that talk to a single database and don’t integrate with other applications are no longer the norm. Today’s applications need to talk to multiple services and databases residing not only inside a company’s data center, but also to external service providers over the internet.

- Customers want faster delivery— Customers no longer want to wait for the next annual release or version of a software package. Instead, they expect the features in a software product to be unbundled so that new functionality can be released quickly in weeks (even days) without having to wait for an entire product release.

- Performance and scalability— Global applications make it extremely difficult to predict how much transaction volume is going to be handled by an application and when that transaction volume is going to hit. Applications need to scale up across multiple servers quickly and then scale back down when the volume needs have passed.

- Customers expect their applications to be available— Because customers are one click away from a competitor, a company’s applications must be highly resilient. Failures or problems in one part of the application shouldn’t bring down the entire application.

To meet these expectations, we, as application developers, have to embrace the paradox that to build high-scalable and highly redundant applications we need to break our applications into small services that can be built and deployed independently of one another. If we “unbundle” our applications into small services and move them away from a single monolithic artifact, we can build systems that are

- Flexible— Decoupled services can be composed and rearranged to quickly deliver new functionality. The smaller the unit of code that one is working with, the less complicated it is to change the code and the less time it takes to test deploy the code.

- Resilient— Decoupled services mean an application is no longer a single “ball of mud” where a degradation in one part of the application causes the whole application to fail. Failures can be localized to a small part of the application and contained before the entire application experiences an outage. This also enables the applications to degrade gracefully in case of an unrecoverable error.

- Scalable— Decoupled services can easily be distributed horizontally across multiple servers, making it possible to scale the features/services appropriately. With a monolithic application where all the logic for the application is intertwined, the entire application needs to scale even if only a small part of the application is the bottleneck. Scaling on small services is localized and much more cost-effective.

To this end, as we begin our discussion of microservices keep the following in mind:

Small, Simple, and Decoupled Services = Scalable, Resilient, and Flexible Applications

1.7. What exactly is the cloud?

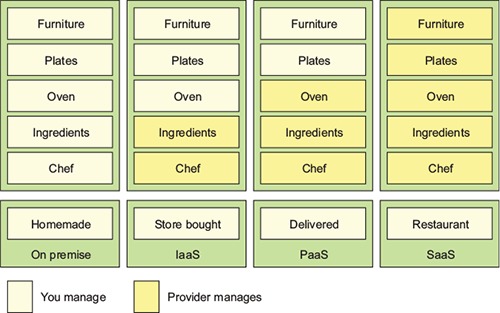

The term “cloud” has become overused. Every software vendor has a cloud and everyone’s platform is cloud-enabled, but if you cut through the hype, three basic models exist in cloud-based computing. These are

- Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS)

- Platform as a Service (PaaS)

- Software as a Service (SaaS)

To better understand these concepts, let’s map the everyday task of making a meal to the different models of cloud computing. When you want to eat a meal, you have four choices:

- You can make the meal at home.

- You can go to the grocery store and buy a meal pre-made that you heat up and serve.

- You can get a meal delivered to your house.

- You can get in the car and eat at restaurant.

Figure 1.6 shows each model.

Figure 1.6. The different cloud computing models come down to who’s responsible for what: the cloud vendor or you.

The difference between these options is about who’s responsible for cooking these meals and where the meal is going to be cooked. In the on-premise model, eating a meal at home requires you to do all the work, using your own oven and ingredients already in the home. A store-bought meal is like using the Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) model of computing. You’re using the store’s chef and oven to pre-bake the meal, but you’re still responsible for heating the meal and eating it at the house (and cleaning up the dishes afterward).

In a Platform as a Service (PaaS) model you still have responsibility for the meal, but you further rely on a vendor to take care of the core tasks associated with making a meal. For example, in a PaaS model, you supply the plates and furniture, but the restaurant owner provides the oven, ingredients, and the chef to cook them. In the Software as a Service (SaaS) model, you go to a restaurant where all the food is prepared for you. You eat at the restaurant and then you pay for the meal when you’re done. you also have no dishes to prepare or wash.

The key items at play in each of these models are ones of control: who’s responsible for maintaining the infrastructure and what are the technology choices available for building the application? In a IaaS model, the cloud vendor provides the basic infrastructure, but you’re accountable for selecting the technology and building the final solution. On the other end of the spectrum, with a SaaS model, you’re a passive consumer of the service provided by the vendor and have no input on the technology selection or any accountability to maintain the infrastructure for the application.

I’ve documented the three core cloud platform types (IaaS, PaaS, SaaS) that are in use today. However, new cloud platform types are emerging. These new platforms include Functions as a Service (FaaS) and Container as a Service (CaaS). FaaS-based (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Function_as_a_Service) applications use technologies like Amazon’s Lambda technologies and Google Cloud functions to build applications deployed as “serverless” chunks of code that run completely on the cloud provider’s platform computing infrastructure. With a FaaS platform, you don’t have to manage any server infrastructure and only pay for the computing cycles required to execute the function.

With the Container as a Service (CaaS) model, developers build and deploy their microservices as portable virtual containers (such as Docker) to a cloud provider. Unlike an IaaS model, where you the developer have to manage the virtual machine the service is deployed to, with CaaS you’re deploying your services in a lightweight virtual container. The cloud provider runs the virtual server the container is running on as well as the provider’s comprehensive tools for building, deploying, monitoring, and scaling containers. Amazon’s Elastic Container Service (ECS) is an example of a CaaS-based platform. In chapter 10 of this book, we’ll see how to deploy the microservices you’ve built to Amazon ECS.

It’s important to note that with both the FaaS and CaaS models of cloud computing, you can still build a microservice-based architecture. Remember, the concept of microservices revolves around building small services, with limited responsibility, using an HTTP-based interface to communicate. The emerging cloud computing platforms, such as FaaS and CaaS, are really about alternative infrastructure mechanisms for deploying microservices.

1.8. Why the cloud and microservices?

One of the core concepts of a microservice-based architecture is that each service is packaged and deployed as its own discrete and independent artifact. Service instances should be brought up quickly and each instance of the service should be indistinguishable from another.

As a developer writing a microservice, sooner or later you’re going to have to decide whether your service is going to be deployed to one of the following:

- Physical server— While you can build and deploy your microservices to a physical machine(s), few organizations do this because physical servers are constrained. You can’t quickly ramp up the capacity of a physical server and it can become extremely costly to scale your microservice horizontally across multiple physical servers.

- Virtual machine images— One of the key benefits of microservices is their ability to quickly start up and shut down microservice instances in response to scalability and service failure events. Virtual machines are the heart and soul of the major cloud providers. A microservice can be packaged up in a virtual machine image and multiple instances of the service can then be quickly deployed and started in either a IaaS private or public cloud.

- Virtual container— Virtual containers are a natural extension of deploying your microservices on a virtual machine image. Rather than deploying a service to a full virtual machine, many developers deploy their services as Docker containers (or equivalent container technology) to the cloud. Virtual containers run inside a virtual machine; using a virtual container, you can segregate a single virtual machine into a series of self-contained processes that share the same virtual machine image.

The advantage of cloud-based microservices centers around the concept of elasticity. Cloud service providers allow you to quickly spin up new virtual machines and containers in a matter of minutes. If your capacity needs for your services drop, you can spin down virtual servers without incurring any additional costs. Using a cloud provider to deploy your microservices gives you significantly more horizontal scalability (adding more servers and service instances) for your applications. Server elasticity also means that your applications can be more resilient. If one of your microservices is having problems and is falling over, spinning up new service instances can you keep your application alive long enough for your development team to gracefully resolve the issue.

For this book, all the microservices and corresponding service infrastructure will be deployed to an IaaS-based cloud provider using Docker containers. This is a common deployment topology used for microservices:

- Simplified infrastructure management— IaaS cloud providers give you the ability to have the most control over your services. New services can be started and stopped with simple API calls. With an IaaS cloud solution, you only pay for the infrastructure that you use.

- Massive horizontal scalability— IaaS cloud providers allow you to quickly and succinctly start one or more instances of a service. This capability means you can quickly scale services and route around misbehaving or failing servers.

- High redundancy through geographic distribution— By necessity, IaaS providers have multiple data centers. By deploying your microservices using an IaaS cloud provider, you can gain a higher level of redundancy beyond using clusters in a data center.

Earlier in the chapter we discussed three types of cloud platforms (Infrastructure as a Service, Platform as a Service, and Software as a Services). For this book, I’ve chosen to focus specifically on building microservices using an IaaS-based approach. While certain cloud providers will let you abstract away the deployment infrastructure for your microservice, I’ve chosen to remain vendor-independent and deploy all parts of my application (including the servers).

For instance, Amazon, Cloud Foundry, and Heroku give you the ability to deploy your services without having to know about the underlying application container. They provide a web interface and APIs to allow you to deploy your application as a WAR or JAR file. Setting up and tuning the application server and the corresponding Java container are abstracted away from you. While this is convenient, each cloud provider’s platform has different idiosyncrasies related to its individual PaaS solution.

An IaaS approach, while more work, is portable across multiple cloud providers and allows us to reach a wider audience with our material. Personally, I’ve found that PaaS-based cloud solutions can allow you to quickly jump start your development effort, but once your application reaches enough microservices, you start to need the flexibility the IaaS style of cloud development provides.

Earlier in the chapter, I mentioned new cloud computing platforms such as Function as a Service (FaaS) and Container as a Service (CaaS). If you’re not careful, FaaS-based platforms can lock your code into a cloud vendor platform because your code is deployed to a vendor-specific runtime engine. With a FaaS-based model, you might be writing your service using a general programming language (Java, Python, JavaScript, and so on), but you’re still tying yourself heavily to the underlying vendor APIs and runtime engine that your function will be deployed to.

The services built in this book are packaged as Docker containers. One of the reasons why I chose Docker is that as a container technology, Docker is deployable to all the major cloud providers. Later in chapter 10, I demonstrate how to package microservices using Docker and then deploy these containers to Amazon’s cloud platform.

1.9. Microservices are more than writing the code

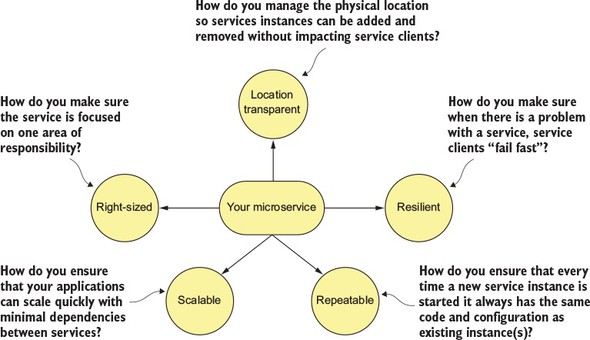

While the concepts around building individual microservices are easy to understand, running and supporting a robust microservice application (especially when running in the cloud) involves more than writing the code for the service. Writing a robust service includes considering several topics. Figure 1.7 highlights these topics.

Figure 1.7. Microservices are more than the business logic. You need to think about the environment where the services are going to run and how the services will scale and be resilient.

Let’s walk through the items in figure 1.7 in more detail:

- Right-sized— How do you ensure that your microservices are properly sized so that you don’t have a microservice take on too much responsibility? Remember, properly sized, a service allows you to quickly make changes to an application and reduces the overall risk of an outage to the entire application.

- Location transparent— How you we manage the physical details of service invocation when in a microservice application, multiple service instances can quickly start and shut down?

- Resilient— How do you protect your microservice consumers and the overall integrity of your application by routing around failing services and ensuring that you take a “fail-fast” approach?

- Repeatable— How do you ensure that every new instance of your service brought up is guaranteed to have the same configuration and code base as all the other service instances in production?

- Scalable— How do you use asynchronous processing and events to minimize the direct dependencies between your services and ensure that you can gracefully scale your microservices?

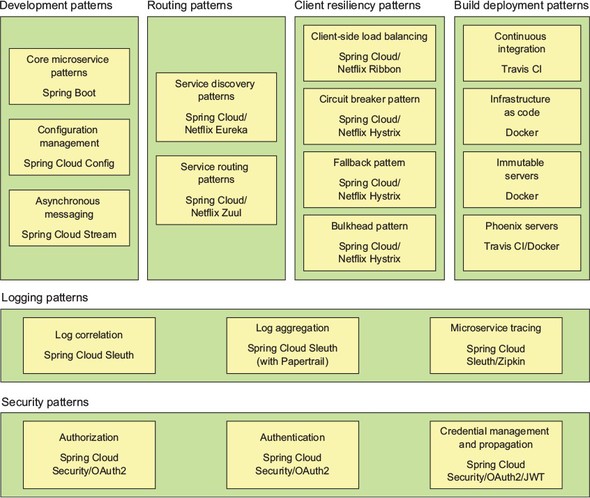

This book takes a patterns-based approach as we answer these questions. With a patterns-based approach, we lay out common designs that can be used across different technology implementations. While we’ve chosen to use Spring Boot and Spring Cloud to implement the patterns we’re going to use in this book, nothing will keep you from taking the concepts presented here and using them with other technology platforms. Specifically, we cover the following six categories of microservice patterns:

- Core development patterns

- Routing patterns

- Client resiliency patterns

- Security patterns

- Logging and tracing patterns

- Build and deployment patterns

Let’s walk through these patterns in more detail.

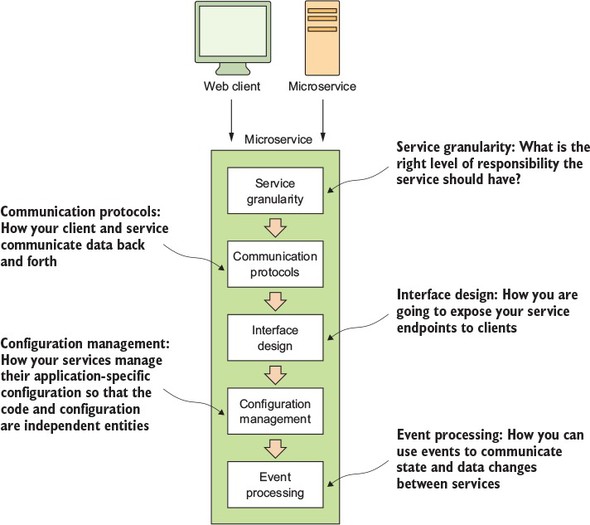

1.9.1. Core microservice development pattern

The core development microservice development pattern addresses the basics of building a microservice. Figure 1.8 highlights the topics we’ll cover around basic service design.

Figure 1.8. When designing your microservice, you have to think about how the service will be consumed and communicated with.

- Service granularity— How do you approach decomposing a business domain down into microservices so that each microservice has the right level of responsibility? Making a service too coarse-grained with responsibilities that overlap into different business problems domains makes the service difficult to maintain and change over time. Making the service too fine-grained increases the overall complexity of the application and turns the service into a “dumb” data abstraction layer with no logic except for that needed to access the data store. I cover service granularity in chapter 2.

- Communication protocols— How will developers communicate with your service? Do you use XML (Extensible Markup Language), JSON (JavaScript Object Notation), or a binary protocol such as Thrift to send data back and forth your microservices? We’ll go into why JSON is the ideal choice for microservices and has become the most common choice for sending and receiving data to microservices. I cover communication protocols in chapter 2.

- Interface design— What’s the best way to design the actual service interfaces that developers are going to use to call your service? How do you structure your service URLs to communicate service intent? What about versioning your services? A well-design microservice interface makes using your service intuitive. I cover interface design in chapter 2.

- Configuration management of service— How do you manage the configuration of your microservice so that as it moves between different environments in the cloud you never have to change the core application code or configuration? I cover managing service configuration in chapter 3.

- Event processing between services— How do you decouple your microservice using events so that you minimize hardcoded dependencies between your services and increase the resiliency of your application? I cover event processing between services in chapter 8.

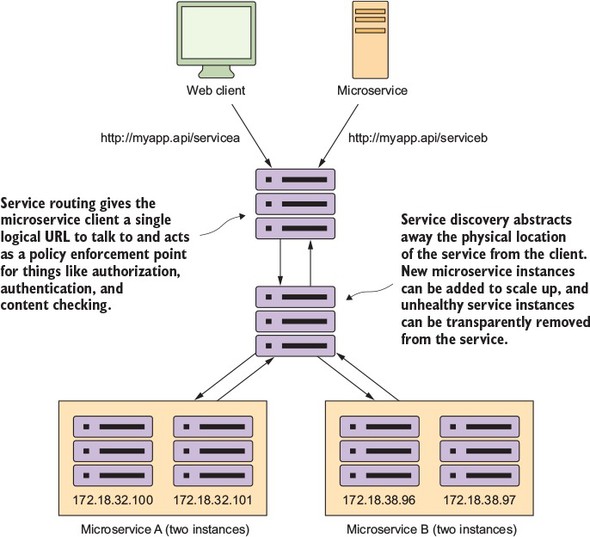

1.9.2. Microservice routing patterns

The microservice routing patterns deal with how a client application that wants to consume a microservice discovers the location of the service and is routed over to it. In a cloud-based application, you might have hundreds of microservice instances running. You’ll need to abstract away the physical IP address of these services and have a single point of entry for service calls so that you can consistently enforce security and content policies for all service calls.

Service discovery and routing answer the question, “How do I get my client’s request for a service to a specific instance of a service?”

- Service discovery— How do you make your microservice discoverable so client applications can find them without having the location of the service hardcoded into the application? How do you ensure that misbehaving microservice instances are removed from the pool of available service instances? I cover service discovery in chapter 4.

- Service routing— How do you provide a single entry point for all of your services so that security policies and routing rules are applied uniformly to multiple services and service instances in your microservice applications? How do you ensure that each developer in your team doesn’t have to come up with their own solutions for providing routing to their services? I cover service routing in chapter 6.

In figure 1.9, service discovery and service routing appear to have a hard-coded sequence of events between them (first comes service routing and the service discovery). However, the two patterns aren’t dependent on one another. For instance, we can implement service discovery without service routing. You can implement service routing without service discovery (even though its implementation is more difficult).

Figure 1.9. Service discovery and routing are key parts of any large-scale microservice application.

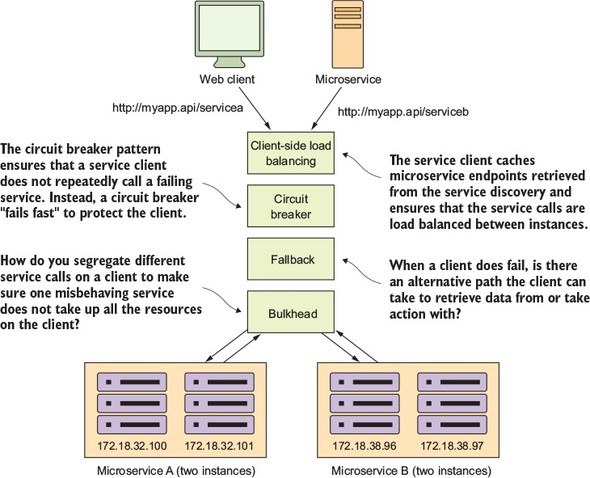

1.9.3. Microservice client resiliency patterns

Because microservice architectures are highly distributed, you have to be extremely sensitive in how you prevent a problem in a single service (or service instance) from cascading up and out to the consumers of the service. To this end, we’ll cover four client resiliency patterns:

- Client-side load balancing— How do you cache the location of your service instances on the service client so that calls to multiple instances of a microservice are load balanced to all the health instances of that microservice?

- Circuit breakers pattern— How do you prevent a client from continuing to call a service that’s failing or suffering performance problems? When a service is running slowly, it consumes resources on the client calling it. You want failing microservice calls to fail fast so that the calling client can quickly respond and take an appropriate action.

- Fallback pattern— When a service call fails, how do you provide a “plug-in” mechanism that will allow the service client to try to carry out its work through alternative means other than the microservice being called?

- Bulkhead pattern— Microservice applications use multiple distributed resources to carry out their work. How do you compartmentalize these calls so that the misbehavior of one service call doesn’t negatively impact the rest of the application?

Figure 1.10 shows how these patterns protect the consumer of service from being impacted when a service is misbehaving. I cover these four topics in chapter 5.

Figure 1.10. With microservices, you must protect the service caller from a poorly behaving service. Remember, a slow or down service can cause disruptions beyond the immediate service.

1.9.4. Microservice security patterns

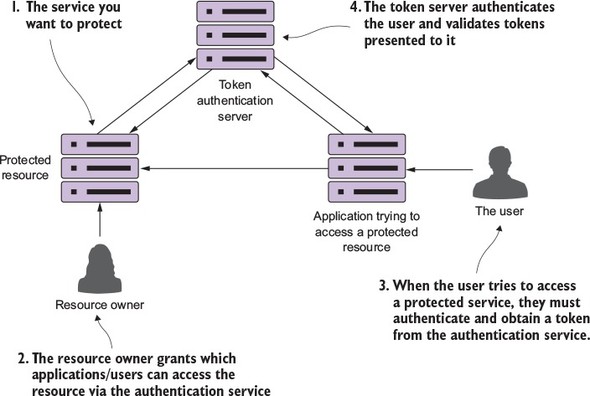

I can’t write a book on microservices without talking about microservice security. In chapter 7 we’ll cover three basic security patterns. These patterns are

- Authentication— How do you determine the service client calling the service is who they say they are?

- Authorization— How do you determine whether the service client calling a microservice is allowed to undertake the action they’re trying to undertake?

- Credential management and propagation— How do you prevent a service client from constantly having to present their credentials for service calls involved in a transaction? Specifically, we’ll look at how token-based security standards such as OAuth2 and JavaScript Web Tokens (JWT) can be used to obtain a token that can be passed from service call to service call to authenticate and authorize the user.

Figure 1.11 shows how you can implement the three patterns described previously to build an authentication service that can protect your microservices.

Figure 1.11. Using a token-based security scheme, you can implement service authentication and authorization without passing around client credentials.

At this point I’m not going to go too deeply into the details of figure 1.10. There’s a reason why security requires a whole chapter. (It could honestly be a book in itself.)

1.9.5. Microservice logging and tracing patterns

The beauty of the microservice architecture is that a monolithic application is broken down into small pieces of functionality that can be deployed independently of one another. The downside of a microservice architecture is that it’s much more difficult to debug and trace what the heck is going on within your application and services.

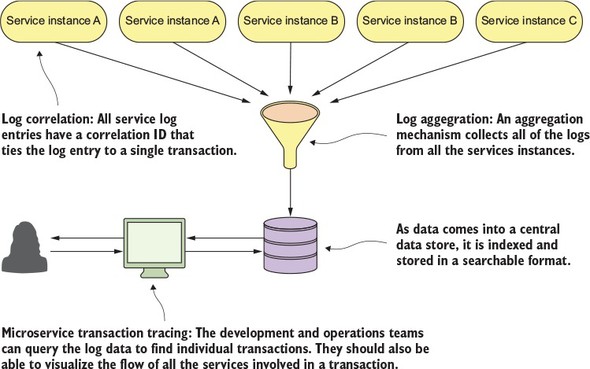

For this reason, we’ll look at three core logging and tracing patterns:

- Log correlation— How do you tie together all the logs produced between services for a single user transaction? With this pattern, we’ll look at how to implement a correlation ID, which is a unique identifier that will be carried across all service calls in a transaction and can be used to tie together log entries produced from each service.

- Log aggregation— With this pattern we’ll look at how to pull together all of the logs produced by your microservices (and their individual instances) into a single queryable database. We’ll also look at how to use correlation IDs to assist in searching your aggregated logs.

- Microservice tracing— Finally, we’ll explore how to visualize the flow of a client transaction across all the services involved and understand the performance characteristics of services involved in the transaction.

Figure 1.12 shows how these patterns fit together. We’ll cover the logging and tracing patterns in greater detail in chapter 9.

Figure 1.12. A well-thought-out logging and tracing strategy makes debugging transactions across multiple services manageable.

1.9.6. Microservice build/deployment patterns

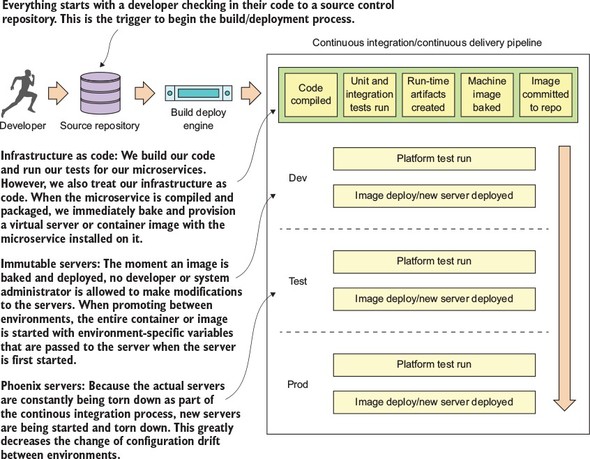

One of the core parts of a microservice architecture is that each instance of a microservice should be identical to all its other instances. You can’t allow “configuration drift” (something changes on a server after it’s been deployed) to occur, because this can introduce instability in your applications.

“I made only one small change on the stage server, but I forgot to make the change in production.” The resolution of many down systems when I’ve worked on critical situations teams over the years has often started with those words from a developer or system administrator. Engineers (and most people in general) operate with good intentions. They don’t go to work to make mistakes or bring down systems. Instead they’re doing the best they can, but they get busy or distracted. They tweak something on a server, fully intending to go back and do it in all the environments.

At a later point, an outage occurs and everyone is left scratching their heads wondering what’s different between the lower environments in production. I’ve found that the small size and limited scope of a microservice makes it the perfect opportunity to introduce the concept of “immutable infrastructure” into an organization: once a service is deployed, the infrastructure it’s running on is never touched again by human hands.

An immutable infrastructure is a critical piece of successfully using a microservice architecture, because you have to guarantee in production that every microservice instance you start for a particular microservice is identical to its brethren.

To this end, our goal is to integrate the configuration of your infrastructure right into your build-deployment process so that you no longer deploy software artifacts such as a Java WAR or EAR to an already-running piece of infrastructure. Instead, you want to build and compile your microservice and the virtual server image it’s running on as part of the build process. Then, when your microservice gets deployed, the entire machine image with the server running on it gets deployed.

Figure 1.13 illustrates this process. At the end of the book we’ll look at how to change your build and deployment pipeline so that your microservices and the servers they run on are deployed as a single unit of work. In chapter 10 we cover the following patterns and topics:

- Build and deployment pipeline— How do you create a repeatable build and deployment process that emphasizes one-button builds and deployment to any environment in your organization?

- Infrastructure as code— How do you treat the provisioning of your services as code that can be executed and managed under source control?

- Immutable servers— Once a microservice image is created, how do you ensure that it’s never changed after it has been deployed?

- Phoenix servers— The longer a server is running, the more opportunity for configuration drift. How do you ensure that servers that run microservices get torn down on a regular basis and recreated off an immutable image?

Figure 1.13. You want the deployment of the microservice and the server it’s running on to be one atomic artifact that’s deployed as a whole between environments.

Our goal with these patterns and topics is to ruthlessly expose and stamp out configuration drift as quickly as possible before it can hit your upper environments, such as stage or production.

Note

For the code examples in this book (except chapter 10), everything will run locally on your desktop machine. The first two chapters can be run natively directly from the command line. Starting in chapter 3, all the code will be compiled and run as Docker containers.

1.10. Using Spring Cloud in building your microservices

In this section, I briefly introduce the Spring Cloud technologies that you’ll use as you build out your microservices. This is a high-level overview; when you use each technology in this book, I’ll teach you the details on each as needed.

Implementing all these patterns from scratch would be a tremendous amount of work. Fortunately for us, the Spring team has integrated a wide number of battle-tested open source projects into a Spring subproject collectively known as Spring Cloud. (http://projects.spring.io/spring-cloud/).

Spring Cloud wraps the work of open source companies such as Pivotal, HashiCorp, and Netflix in delivering patterns. Spring Cloud simplifies setting up and configuring of these projects into your Spring application so that you can focus on writing code, not getting buried in the details of configuring all the infrastructure that can go with building and deploying a microservice application.

Figure 1.14 maps the patterns listed in the previous section to the Spring Cloud projects that implement them.

Figure 1.14. You can map the technologies you’re going to use directly to the microservice patterns we’ve explored so far in this chapter.

Let’s walk through these technologies in greater detail.

1.10.1. Spring Boot

Spring Boot is the core technology used in our microservice implementation. Spring Boot greatly simplifies microservice development by simplifying the core tasks of building REST-based microservices. Spring Boot also greatly simplifies mapping HTTP-style verbs (GET, PUT, POST, and DELETE) to URLs and the serialization of the JSON protocol to and from Java objects, as well as the mapping of Java exceptions back to standard HTTP error codes.

1.10.2. Spring Cloud Config

Spring Cloud Config handles the management of application configuration data through a centralized service so your application configuration data (particularly your environment specific configuration data) is cleanly separated from your deployed microservice. This ensures that no matter how many microservice instances you bring up, they’ll always have the same configuration. Spring Cloud Config has its own property management repository, but also integrates with open source projects such as the following:

- Git— Git (https://git-scm.com/) is an open source version control system that allows you to manage and track changes to any type of text file. Spring Cloud Config can integrate with a Git-backed repository and read the application’s configuration data out of the repository.

- Consul— Consul (https://www.consul.io/) is an open source service discovery tool that allows service instances to register themselves with the service. Service clients can then ask Consul where the service instances are located. Consul also includes key-value store based database that can be used by Spring Cloud Config to store application configuration data.

- Eureka— Eureka (https://github.com/Netflix/eureka) is an open source Net-flix project that, like Consul, offers similar service discovery capabilities. Eureka also has a key-value database that can be used with Spring Cloud Config.

1.10.3. Spring Cloud service discovery

With Spring Cloud service discovery, you can abstract away the physical location (IP and/or server name) of where your servers are deployed from the clients consuming the service. Service consumers invoke business logic for the servers through a logical name rather than a physical location. Spring Cloud service discovery also handles the registration and deregistration of services instances as they’re started up and shut down. Spring Cloud service discovery can be implemented using Consul (https://www.consul.io/) and Eureka (https://github.com/Netflix/eureka) as its service discovery engine.

1.10.4. Spring Cloud/Netflix Hystrix and Ribbon

Spring Cloud heavily integrates with Netflix open source projects. For microservice client resiliency patterns, Spring Cloud wraps the Netflix Hystrix libraries (https://github.com/Netflix/Hystrix) and Ribbon project (https://github.com/Netflix/Ribbon) and makes using them from within your own microservices trivial to implement.

Using the Netflix Hystrix libraries, you can quickly implement service client resiliency patterns such as the circuit breaker and bulkhead patterns.

While the Netflix Ribbon project simplifies integrating with service discovery agents such as Eureka, it also provides client-side load-balancing of service calls from a service consumer. This makes it possible for a client to continue making service calls even if the service discovery agent is temporarily unavailable.

1.10.5. Spring Cloud/Netflix Zuul

Spring Cloud uses the Netflix Zuul project (https://github.com/Netflix/zuul) to provide service routing capabilities for your microservice application. Zuul is a service gateway that proxies service requests and makes sure that all calls to your microservices go through a single “front door” before the targeted service is invoked. With this centralization of service calls, you can enforce standard service policies such as a security authorization authentication, content filtering, and routing rules.

1.10.6. Spring Cloud Stream

Spring Cloud Stream (https://cloud.spring.io/spring-cloud-stream/) is an enabling technology that allows you to easily integrate lightweight message processing into your microservice. Using Spring Cloud Stream, you can build intelligent microservices that can use asynchronous events as they occur in your application. With Spring Cloud Stream, you can quickly integrate your microservices with message brokers such as RabbitMQ (https://www.rabbitmq.com/) and Kafka (http://kafka.apache.org/).

1.10.7. Spring Cloud Sleuth

Spring Cloud Sleuth (https://cloud.spring.io/spring-cloud-sleuth/) allows you to integrate unique tracking identifiers into the HTTP calls and message channels (RabbitMQ, Apache Kafka) being used within your application. These tracking numbers, sometimes referred to as correlation or trace ids, allow you to track a transaction as it flows across the different services in your application. With Spring Cloud Sleuth, these trace IDs are automatically added to any logging statements you make in your microservice.

The real beauty of Spring Cloud Sleuth is seen when it’s combined with logging aggregation technology tools such as Papertrail (http://papertrailapp.com) and tracing tools such as Zipkin (http://zipkin.io). Papertail is a cloud-based logging platform used to aggregate logs in real time from different microservices into one queryable database. Open Zipkin takes data produced by Spring Cloud Sleuth and allows you to visualize the flow of your service calls involved for a single transaction.

1.10.8. Spring Cloud Security

Spring Cloud Security (https://cloud.spring.io/spring-cloud-security/) is an authentication and authorization framework that can control who can access your services and what they can do with your services. Spring Cloud Security is token-based and allows services to communicate with one another through a token issued by an authentication server. Each service receiving a call can check the provided token in the HTTP call to validate the user’s identity and their access rights with the service.

In addition, Spring Cloud Security supports the JavaScript Web Token (https://jwt.io). The JavaScript Web Token (JWT) framework standardizes the format of how a OAuth2 token is created and provides standards for digitally signing a created token.

1.10.9. What about provisioning?

For the provisioning implementations, we’re going to make a technology shift. The Spring framework(s) are geared toward application development. The Spring frameworks (including Spring Cloud) don’t have tools for creating a “build and deployment” pipeline. To implement a “build and deployment” pipeline you’re going to use the following tools: Travis CI (https://travis-ci.org) for your build tool and Docker (https://www.docker.com/) to build the final server image containing your microservice.

To deploy your built Docker containers, we end the book with an example of how to deploy the entire application stack built throughout this book to Amazon’s cloud.

1.11. Spring Cloud by example

In the last section, we walked through all the different Spring Cloud technologies that you’re going to use as you build out your microservices. Because each of these technologies are independent services, it’s obviously going to take more than one chapter to explain all of them in detail. However, as I wrap up this chapter, I want to leave you with a small code example that again demonstrates how easy it is to integrate these technologies into your own microservice development effort.

Unlike the first code example in listing 1.1, you can’t run this code example because a number of supporting services need to be set up and configured to be used. Don’t worry, though; the setup costs for these Spring Cloud services (configuration service, service discovery) are a one-time cost in terms of setting up the service. Once they’re set up, your individual microservices can use these capabilities over and over again. We couldn’t fit all that goodness into a single code example at the beginning of the book.

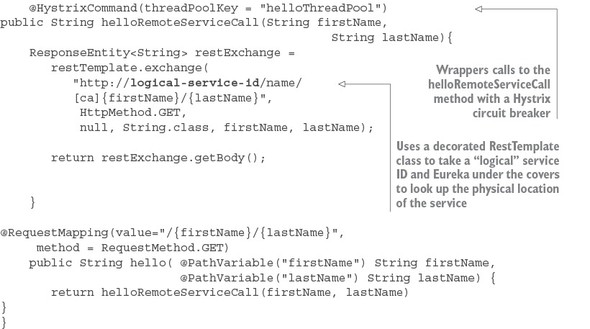

The code shown in the following listing quickly demonstrates how the service discovery, circuit breaker, bulkhead, and client-side load balancing of remote services were integrated into our “Hello World” example.

Listing 1.2. Hello World Service using Spring Cloud

This code has a lot packed into it, so let’s walk through it. Keep in mind that this listing is only an example and isn’t found in the chapter 1 GitHub repository source code. I’ve included it here to give you a taste of what’s to come later in the book.

The first thing you should notice is the @EnableCircuitBreaker and @EnableEurekaClient annotations. The @EnableCircuitBreaker annotation tells your Spring microservice that you’re going to use the Netflix Hystrix libraries in your application. The @EnableEurekaClient annotation tells your microservice to register itself with a Eureka Service Discovery agent and that you’re going to use service discovery to look up remote REST services endpoints in your code. Note that configuration is happening in a property file that will tell the simple service the location and port number of a Eureka server to contact. You first see Hystrix being used when you declare your hello method:

@HystrixCommand(threadPoolKey = "helloThreadPool") public String helloRemoteServiceCall(String firstName, String lastName)

The @HystrixCommand annotation is doing two things. First, any time the helloRemoteServiceCall method is called, it won’t be directly invoked. Instead, the method will be delegated to a thread pool managed by Hystrix. If the call takes too long (default is one second), Hystrix steps in and interrupts the call. This is the implementation of the circuit breaker pattern. The second thing this annotation does is create a thread pool called helloThreadPool that’s managed by Hystrix. All calls to helloRemoteServiceCall method will only occur on this thread pool and will be isolated from any other remote service calls being made.

The last thing to note is what’s occurring inside the helloRemoteServiceCall method. The presence of the @EnableEurekaClient has told Spring Boot that you’re going to use a modified RestTemplate class (this isn’t how the Standard Spring RestTemplate would work out of the box) whenever you make a REST service call. This RestTemplate class will allow you to pass in a logical service ID for the service you’re trying to invoke:

ResponseEntity<String> restExchange = restTemplate.exchange (http://logical-service-id/name/{firstName}/{lastName}

Under the covers, the RestTemplate class will contact the Eureka service and look up the physical location of one or more of the “name” service instances. As a consumer of the service, your code never has to know where that service is located.

Also, the RestTemplate class is using Netflix’s Ribbon library. Ribbon will retrieve a list of all the physical endpoints associated with a service. Every time the service is called by the client, it “round-robins” the call to the different service instances on the client without having to go through a centralized load balancer. By eliminating a centralized load balancer and moving it to the client, you eliminate another failure point (load balancer going down) in your application infrastructure.

I hope that at this point you’re impressed, because you’ve added a significant number of capabilities to your microservice with only a few annotations. That’s the real beauty behind Spring Cloud. You as a developer get to take advantage of battle-hardened microservice capabilities from premier cloud companies like Netflix and Consul. These capabilities, if used outside of Spring Cloud, can be complex and obtuse to set up. Spring Cloud simplifies their use to literally nothing more than a few simple Spring Cloud annotations and configuration entries.

1.12. Making sure our examples are relevant

I want to make sure this book provides examples that you can relate to as you go about your day-to-day job. To this end, I’ve structured the chapters in this book and the corresponding code examples around the adventures (misadventures) of a fictitious company called ThoughtMechanix.

ThoughtMechanix is a software development company whose core product, EagleEye, provides an enterprise-grade software asset management application. It provides coverage for all the critical elements: inventory, software delivery, license management, compliance, cost, and resource management. Its primary goal is to enable organizations to gain an accurate point-in-time picture of its software assets.

The company is approximately 10 years old. While they’ve experienced solid revenue growth, internally they’re debating whether they should be re-platforming their core product from a monolithic on-premise-based application or move their application to the cloud. The re-platforming involved with EagleEye can be a “make or break” moment for a company.

The company is looking at rebuilding their core product EagleEye on a new architecture. While much of the business logic for the application will remain in place, the application itself will be broken down from a monolithic design to a much smaller microservice design whose pieces can be deployed independently to the cloud. The examples in this book won’t build the entire ThoughtMechanix application. Instead you’ll build specific microservices from the problem domain at hand and then build the infrastructure that will support these services using various Spring Cloud (and some non-Spring-Cloud) technologies.

The ability to successfully adopt cloud-based, microservice architecture will impact all parts of a technical organization. This includes the architecture, engineering, testing, and operations teams. Input will be needed from each group and, in the end, they’re probably going to need reorganization as the team reevaluates their responsibilities in this new environment. Let’s start our journey with ThoughtMechanix as you begin the fundamental work of identifying and building out several of the microservices used in EagleEye and then building these services using Spring Boot.

1.13. Summary

- Microservices are extremely small pieces of functionality that are responsible for one specific area of scope.

- No industry standards exist for microservices. Unlike other early web service protocols, microservices take a principle-based approach and align with the concepts of REST and JSON.

- Writing microservices is easy, but fully operationalizing them for production requires additional forethought. We introduced several categories of microservice development patterns, including core development, routing patterns, client resiliency, security, logging, and build/deployment patterns.

- While microservices are language-agnostic, we introduced two Spring frameworks that significantly help in building microservices: Spring Boot and Spring Cloud.

- Spring Boot is used to simplify the building of REST-based/JSON microservices. Its goal is to make it possible for you to build microservices quickly with nothing more than a few annotations.

- Spring Cloud is a collection of open source technologies from companies such as Netflix and HashiCorp that have been “wrapped” with Spring annotations to significantly simplify the setup and configuration of these services.