Chapter 5. When bad things happen: client resiliency patterns with Spring Cloud and Netflix Hystrix

- Implementing circuit breakers, fallbacks, and bulkheads

- Using the circuit breaker pattern to conserve microservice client resources

- Using Hystrix when a remote service is failing

- Implementing Hystrix’s bulkhead pattern to segregate remote resource calls

- Tuning Hystrix’s circuit breaker and bulkhead implementations

- Customizing Hystrix’s concurrency strategy

All systems, especially distributed systems, will experience failure. How we build our applications to respond to that failure is a critical part of every software developer’s job. However, when it comes to building resilient systems, most software engineers only take into account the complete failure of a piece of infrastructure or a key service. They focus on building redundancy into each layer of their application using techniques such as clustering key servers, load balancing between services, and segregation of infrastructure into multiple locations.

While these approaches take into account the complete (and often spectacular) loss of a system component, they address only one small part of building resilient systems. When a service crashes, it’s easy to detect that it’s no longer there, and the application can route around it. However, when a service is running slow, detecting that poor performance and routing around it is extremely difficult because

- Degradation of a service can start out as intermittent and build momentum— The degradation might occur only in small bursts. The first signs of failure might be a small group of users complaining about a problem, until suddenly the application container exhausts its thread pool and collapses completely.

- Calls to remote services are usually synchronous and don’t cut short a long-running call— The caller of a service has no concept of a timeout to keep the service call from hanging out forever. The application developer calls the service to perform an action and waits for the service to return.

- Applications are often designed to deal with complete failures of remote resources, not partial degradations. Often, as long as the service has not completely failed, an application will continue to call the service and won’t fail fast. The application will continue to call the poorly behaving service. The calling application or service may degrade gracefully or, more likely, crash because of resource exhaustion. Resource exhaustion is when a limited resource such as a thread pool or database connection maxes out and the calling client must wait for that resource to become available.

What’s insidious about problems caused by poorly performing remote services is that they’re not only difficult to detect, but can trigger a cascading effect that can ripple throughout an entire application ecosystem. Without safeguards in place, a single poorly performing service can quickly take down multiple applications. Cloud-based, microservice-based applications are particularly vulnerable to these types of outages because these applications are composed of a large number of fine-grained, distributed services with different pieces of infrastructure involved in completing a user’s transaction.

5.1. What are client-side resiliency patterns?

Client resiliency software patterns are focused on protecting a remote resource’s (another microservice call or database lookup) client from crashing when the remote resource is failing because that remote service is throwing errors or performing poorly. The goal of these patterns is to allow the client to “fail fast,” not consume valuable resources such as database connections and thread pools, and prevent the problem of the remote service from spreading “upstream” to consumers of the client.

There are four client resiliency patterns:

- Client-side load balancing

- Circuit breakers

- Fallbacks

- Bulkheads

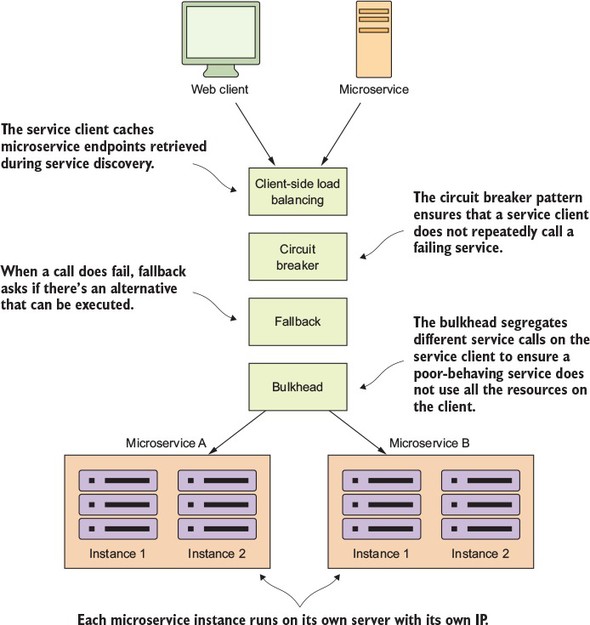

Figure 5.1 demonstrates how these patterns sit between the microservice service consumer and the microservice.

Figure 5.1. The four client resiliency patterns act as a protective buffer between a service consumer and the service.

These patterns are implemented in the client calling the remote resource. The implementation of these patterns logically sit between the client consuming the remote resources and the resource itself.

5.1.1. Client-side load balancing

We introduced the client-side load balancing pattern in the last chapter (chapter 4) when talking about service discovery. Client-side load balancing involves having the client look up all of a service’s individual instances from a service discovery agent (like Netflix Eureka) and then caching the physical location of said service instances. Whenever a service consumer needs to call that service instance, the client-side load balancer will return a location from the pool of service locations it’s maintaining.

Because the client-side load balancer sits between the service client and the service consumer, the load balancer can detect if a service instance is throwing errors or behaving poorly. If the client-side load balancer detects a problem, it can remove that service instance from the pool of available service locations and prevent any future service calls from hitting that service instance.

This is exactly the behavior that Netflix’s Ribbon libraries provide out of the box with no extra configuration. Because we covered client-side load balancing with Net-flix Ribbon in chapter 4, we won’t go into any more detail on that in this chapter.

5.1.2. Circuit breaker

The circuit breaker pattern is a client resiliency pattern that’s modeled after an electrical circuit breaker. In an electrical system, a circuit breaker will detect if too much current is flowing through the wire. If the circuit breaker detects a problem, it will break the connection with the rest of the electrical system and keep the downstream components from the being fried.

With a software circuit breaker, when a remote service is called, the circuit breaker will monitor the call. If the calls take too long, the circuit breaker will intercede and kill the call. In addition, the circuit breaker will monitor all calls to a remote resource and if enough calls fail, the circuit break implementation will pop, failing fast and preventing future calls to the failing remote resource.

5.1.3. Fallback processing

With the fallback pattern, when a remote service call fails, rather than generating an exception, the service consumer will execute an alternative code path and try to carry out an action through another means. This usually involves looking for data from another data source or queueing the user’s request for future processing. The user’s call will not be shown an exception indicating a problem, but they may be notified that their request will have to be fulfilled at a later date.

For instance, suppose you have an e-commerce site that monitors your user’s behavior and tries to give them recommendations of other items they could buy. Typically, you might call a microservice to run an analysis of the user’s past behavior and return a list of recommendations tailored to that specific user. However, if the preference service fails, your fallback might be to retrieve a more general list of preferences that’s based off all user purchases and is much more generalized. This data might come from a completely different service and data source.

5.1.4. Bulkheads

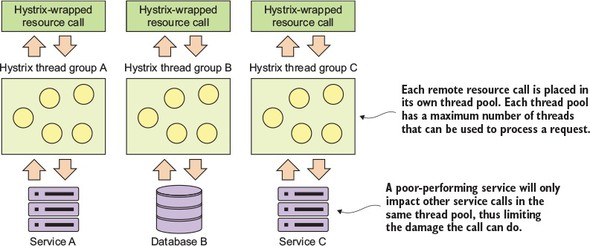

The bulkhead pattern is based on a concept from building ships. With a bulkhead design, a ship is divided into completely segregated and watertight compartments called bulkheads. Even if the ship’s hull is punctured, because the ship is divided into watertight compartments (bulkheads), the bulkhead will keep the water confined to the area of the ship where the puncture occurred and prevent the entire ship from filling with water and sinking.

The same concept can be applied to a service that must interact with multiple remote resources. By using the bulkhead pattern, you can break the calls to remote resources into their own thread pools and reduce the risk that a problem with one slow remote resource call will take down the entire application. The thread pools act as the bulkheads for your service. Each remote resource is segregated and assigned to the thread pool. If one service is responding slowly, the thread pool for that one type of service call will become saturated and stop processing requests. Service calls to other services won’t become saturated because they’re assigned to other thread pools.

5.2. Why client resiliency matters

We’ve talked about these different patterns in the abstract; however, let’s drill down to a more specific example of where these patterns can be applied. Let’s walk through a common scenario I’ve run into and see why client resiliency patterns such as the circuit breaker pattern are critical for implementing a service-based architecture, particularly a microservice architecture running in the cloud.

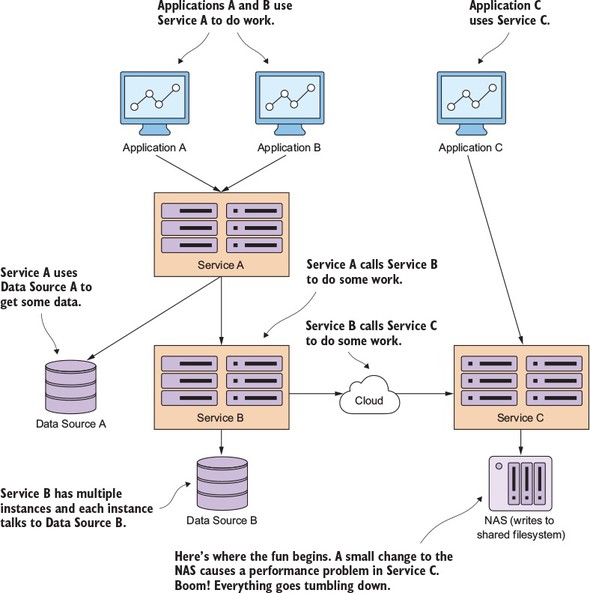

In figure 5.2, I show a typical scenario involving the use of remote resource like a database and remote service.

Figure 5.2. An application is a graph of interconnected dependencies. If you don’t manage the remote calls between these, one poorly behaving remote resource can bring down all the services in the graph.

In the scenario in figure 5.2, three applications are communicating in one fashion or another with three different services. Applications A and B communicate directly with Service A. Service A retrieves data from a database and calls Service B to do work for it. Service B retrieves data from a completely different database platform and calls out to another service, Service C, from a third-party cloud provider whose service relies heavily on an internal Network Area Storage (NAS) device to write data to a shared file system. In addition, Application C directly calls Service C.

Over the weekend, a network administrator made what they thought was a small tweak to the configuration on the NAS, as shown in bold in figure 5.2. This change appears to work fine, but on Monday morning, any reads to a particular disk subsystem start performing extremely slowly.

The developer who wrote Service B never anticipated slowdowns occurring with calls to Service C. They wrote their code so that the writes to their database and the reads from the service occur within the same transaction. When Service C starts running slowly, not only does the thread pool for requests to Service C start backing up, the number of database connections in the service container’s connection pools become exhausted because these connections are being held open because the calls out to Service C never complete.

Finally, Service A starts running out of resources because it’s calling Service B, which is running slow because of Service C. Eventually, all three applications stop responding because they run out of resources while waiting for requests to complete.

This whole scenario could be avoided if a circuit-breaker pattern had been implemented at each point where a distributed resource had been called (either a call to the database or a call to the service). In figure 5.2, if the call to Service C had been implemented with a circuit breaker, then when service C started performing poorly, the circuit breaker for that specific call to Service C would have been tripped and failed fast without eating up a thread. If Service B had multiple endpoints, only the endpoints that interacted with that specific call to Service C would be impacted. The rest of Service B’s functionality would still be intact and could fulfill user requests.

A circuit breaker acts as a middle man between the application and the remote service. In the previous scenario, a circuit breaker implementation could have protected Applications A, B, and C from completely crashing.

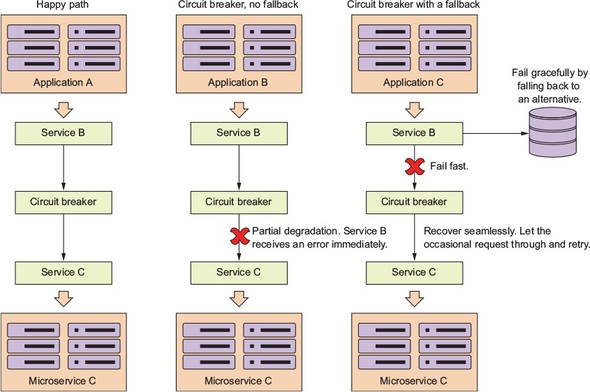

In figure 5.3, the Service B (the client) is never going to directly invoke Service C. Instead, when the call is made, Service B is going to delegate the actual invocation of the service to the circuit breaker, which will take the call and wrap it in a thread (usually managed by a thread pool) that’s independent of the originating caller. By wrapping the call in a thread, the client is no longer directly waiting for the call to complete. Instead, the circuit breaker is monitoring the thread and can kill the call if the thread runs too long.

Figure 5.3. The circuit breaker trips and allows a misbehaving service call to fail quickly and gracefully.

Three scenarios are shown in figure 5.3. In the first scenario, the happy path, the circuit breaker will maintain a timer and if the call to the remote service completes before the timer runs out, everything is good and Service B can continue its work. In the partial degradation scenario, Service B will call Service C through the circuit breaker. This time, though, Service C is running slow and the circuit breaker will kill the connection out to the remote service if it doesn’t complete before the timer on the thread maintained by the circuit breaker times out.

Service B will then get an error from making the call, but Service B won’t have resources (that is, its own thread or connection pools) tied up waiting for Service C to complete. If the call to Service C is timed-out by the circuit breaker, the circuit breaker will start tracking the number of failures that have occurred.

If enough errors on the service have occurred within a certain time period, the circuit breaker will now “trip” the circuit and all calls to Service C will fail without calling Service C.

This tripping of the circuit allows three things to occur:

- Service B now immediately knows there’s a problem without having to wait for a timeout from the circuit breaker.

- Service B can now choose to either completely fail or take action using an alternative set of code (a fallback).

- Service C will be given an opportunity to recover because Service B isn’t calling it while the circuit breaker has been tripped. This allows Service C to have breathing room and helps prevent the cascading death that occurs when a service degradation occurs.

Finally, the circuit breaker will occasionally let calls through to a degraded service, and if those calls succeed enough times in a row, the circuit breaker will reset itself.

The key thing a circuit break patterns offers is the ability for remote calls to

- Fail fast— When a remote service is experiencing a degradation, the application will fail fast and prevent resource exhaustion issues that normally shut down the entire application. In most outage situations, it’s better to be partially down rather than completely down.

- Fail gracefully— By timing out and failing fast, the circuit breaker pattern gives the application developer the ability to fail gracefully or seek alternative mechanisms to carry out the user’s intent. For instance, if a user is trying to retrieve data from one data source, and that data source is experiencing a service degradation, then the application developer could try to retrieve that data from another location.

- Recover seamlessly— With the circuit-breaker pattern acting as an intermediary, the circuit breaker can periodically check to see if the resource being requested is back on line and re-enable access to it without human intervention.

In a large cloud-based application with hundreds of services, this graceful recovery is critical because it can significantly cut down on the amount of time needed to restore service and significantly lessen the risk of a tired operator or application engineer causing greater problems by having them intervene directly (restarting a failed service) in the restoration of the service.

5.3. Enter Hystrix

Building implementations of the circuit breaker, fallback, and bulkhead patterns requires intimate knowledge of threads and thread management. Let’s face it, writing robust threading code is an art (which I’ve never mastered) and doing it correctly is difficult. To implement a high-quality set of implementations for the circuit-breaker, fallback, and bulkhead patterns would require a tremendous amount of work. Fortunately, you can use Spring Cloud and Netflix’s Hystrix library to provide you a battle-tested library that’s used daily in Netflix’s microservice architecture.

In the next several sections of this chapter we’re going to cover how to

- Configure the licensing service’s maven build file (pom.xml) to include the Spring Cloud/Hystrix wrappers.

- Use the Spring Cloud/Hystrix annotations to wrapper remote calls with a circuit breaker pattern.

- Customize the individual circuit breakers on a remote resource to use custom timeouts for each call made. I’ll also demonstrate how to configure the circuit breakers so that you control how many failures occur before a circuit breaker “trips.”

- Implement a fallback strategy in the event a circuit breaker has to interrupt a call or the call fails.

- Use individual thread pools in your service to isolate service calls and build bulkheads between different remote resources being called.

5.4. Setting up the licensing server to use Spring Cloud and Hystrix

To begin our exploration of Hystrix, you need to set up your project pom.xml to import the Spring Hystrix dependencies. You’ll take your licensing service that we’ve been building and modify its pom.xml by adding the maven dependencies for Hystrix:

<dependency> <groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId> <artifactId>spring-cloud-starter-hystrix</artifactId> </dependency> <dependency> <groupId>com.netflix.hystrix</groupId> <artifactId>hystrix-javanica</artifactId> <version>1.5.9</version> </dependency>

The first <dependency> tag (spring-cloud-starter-hystrix) tells Maven to pull down the Spring Cloud Hystrix dependencies. This second <dependency> tag (hystrix-javanica) will pull down the core Netflix Hystrix libraries. With the Maven dependencies set up, you can go ahead and begin your Hystrix implementation using the licensing and organization services you built in previous chapters.

Note

You don’t have to include the hystrix-javanica dependencies directly in the pom.xml. By default, the spring-cloud-starter-hystrix includes a version of the hystrix-javanica dependencies. The Camden.SR5 release of the book used hystrix-javanica-1.5.6. The version of hystrix-javanica had an inconsistency introduced into it that caused the Hystrix code without a fallback to throw a java.lang.reflect. UndeclaredThrowableException instead of a com.netflix. hystrix.exception.HystrixRuntimeException. This was a breaking change for many developers who used older versions of Hystrix. The hystrix-javanica libraries fixed this in later releases, so I’ve purposely used a later version of hystrix-javanica instead of using the default version pulled in by Spring Cloud.

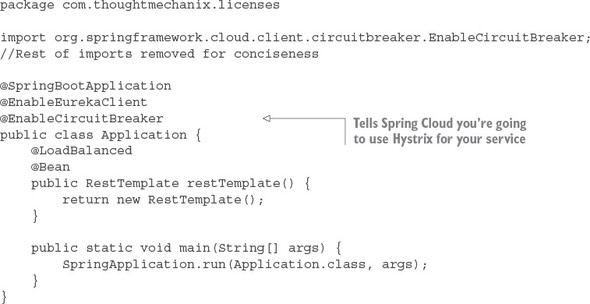

The last thing that needs to be done before you can begin using Hystrix circuit breakers within your application code is to annotate your service’s bootstrap class with the @EnableCircuitBreaker annotation. For example, for the licensing service, you’d add the @EnableCircuitBreaker annotation to the licensing-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/Application.java class. The following listing shows this code.

Listing 5.1. The @EnableCircuitBreaker annotation used to activate Hystrix in a service

Note

If you forget to add the @EnableCircuitBreaker annotation to your bootstrap class, none of your Hystrix circuit breakers will be active. You won’t get any warning or error messages when the service starts up.

5.5. Implementing a circuit breaker using Hystrix

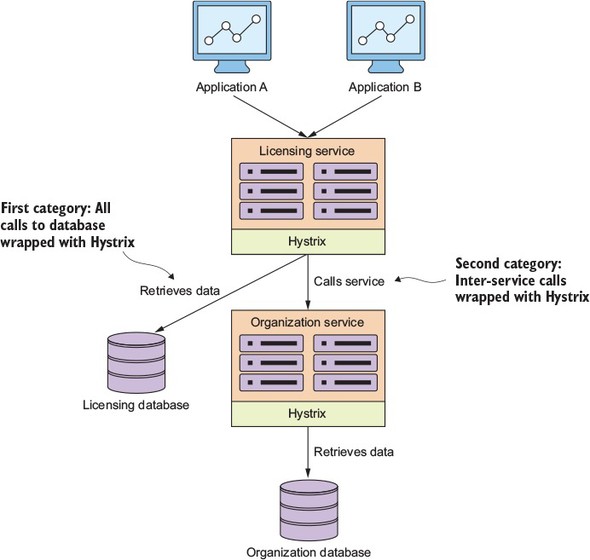

We’re going to look at implementing Hystrix in two broad categories. In the first category, you’re going to wrap all calls to your database in the licensing and organization service with a Hystrix circuit breaker. You’re then going to wrap the inter-service calls between the licensing service and the organization service using Hystrix. While these are two different categories calls, you’ll see that the use of Hystrix will be exactly the same. Figure 5.4 shows what remote resources you’re going to wrap with a Hystrix circuit breaker.

Figure 5.4. Hystrix sits between each remote resource call and protects the client. It doesn’t matter if the remote resource call is a database call or a REST-based service call.

Let’s start our Hystrix discussion by showing how to wrap the retrieval of licensing service data from the licensing database using a synchronous Hystrix circuit breaker. With a synchronous call, the licensing service will retrieve its data but will wait for the SQL statement to complete or for a circuit-breaker time-out before continuing processing.

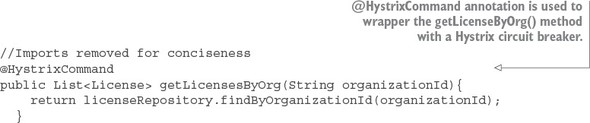

Hystrix and Spring Cloud use the @HystrixCommand annotation to mark Java class methods as being managed by a Hystrix circuit breaker. When the Spring framework sees the @HystrixCommand, it will dynamically generate a proxy that will wrapper the method and manage all calls to that method through a thread pool of threads specifically set aside to handle remote calls.

You’re going to wrap the getLicensesByOrg() method in your licensing-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/services/LicenseService.java class, as shown in the following listing.

Listing 5.2. Wrappering a remote resource call with a circuit breaker

Note

If you look at the code in listing 5.2 in the source code repository, you’ll see several more parameters on the @HystrixCommand annotation than what’s shown in the previous listing. We’ll get into those parameters later in the chapter. The code in listing 5.2 is using the @HystrixCommand annotation with all its default values.

This doesn't look like a lot of code, and it's not, but there is a lot of functionality inside this one annotation. With the use of the @HystrixCommand annotation, any time the getLicensesByOrg() method is called, the call will be wrapped with a Hystrix circuit breaker. The circuit breaker will interrupt any call to the getLicensesByOrg() method any time the call takes longer than 1,000 milliseconds.

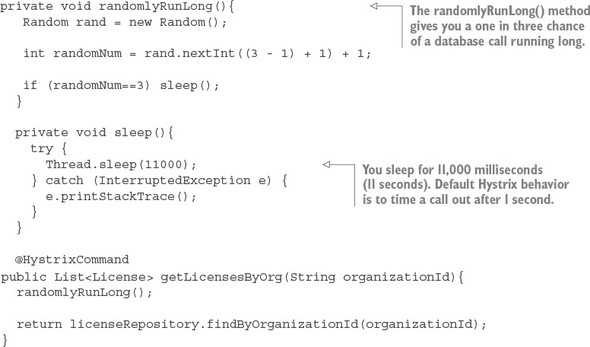

This code example would be boring if the database is working properly. Let's simulate the getLicensesByOrg() method running into a slow database query by having the call take a little over a second on approximately every one in three calls. The following listing demonstrates this.

Listing 5.3. Randomly timing out a call to the licensing service database

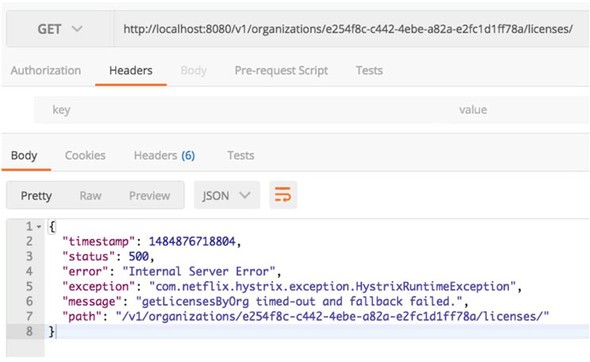

If you hit the http://localhost/v1/organizations/e254f8c-c442-4ebe-a82a-e2fc1d1ff78a/licenses/ endpoint enough times, you should see a timeout error message returned from the licensing service. Figure 5.5 shows this error.

Figure 5.5. A HystrixRuntimeException is thrown when a remote call takes too long.

Now, with @HystrixCommand annotation in place, the licensing service will interrupt a call out to its database if the query takes too long. If the database calls take longer than 1,000 milliseconds to execute the Hystrix code wrapping, your service call will throw a com.nextflix.hystrix.exception.HystrixRuntimeException exception.

5.5.1. Timing out a call to the organization microservice

The beauty of using method-level annotations for tagging calls with circuit-breaker behavior is that it’s the same annotation whether you’re accessing a database or calling a microservice.

For instance, in your licensing service you need to look up the name of the organization associated with the license. If you want to wrap your call to the organization service with a circuit breaker, it’s as simple as breaking the RestTemplate call into its own method and annotating it with the @HystrixCommand annotation:

@HystrixCommand

private Organization getOrganization(String organizationId) {

return organizationRestClient.getOrganization(organizationId);

}

Note

While using the @HystrixCommand is easy to implement, you do need to be careful about using the default @HystrixCommand annotation with no configuration on the annotation. By default, when you specify a @HystrixCommand annotation without properties, the annotation will place all remote service calls under the same thread pool. This can introduce problems in your application. Later in the chapter when we talk about implementing the bulkhead pattern, we’ll show you how to segregate these remote service calls into their own thread pools and configure the behavior of the thread pools to be independent of one another.

5.5.2. Customizing the timeout on a circuit breaker

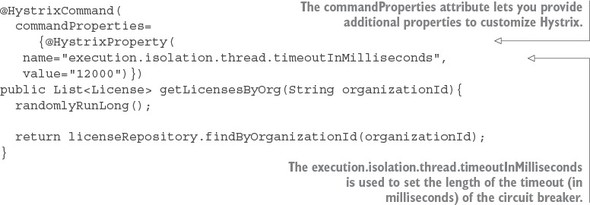

One of the first questions I often run into when working with new developers and Hystrix is how they can customize the amount of time before a call is interrupted by Hystrix. This is easily accomplished by passing additional parameters into the @HystrixCommand annotation. The following listing demonstrates how to customize the amount of time Hystrix waits before timing out a call.

Listing 5.4. Customizing the time out on a circuit breaker call

Hystrix allows you to customize the behavior of the circuit breaker through the commandProperties attribute. The commandProperties attribute accepts an array of HystrixProperty objects that can pass in custom properties to configure the Hystrix circuit breaker. In listing 5.4, you use the execution.isolation.thread.timeoutInMilliseconds property to set the maximum timeout a Hystrix call will wait before failing to be 12 seconds.

Now if you rebuild and rerun the code example, you’ll never get a timeout error because your artificial timeout on the call is 11 seconds while your @HystrixCommand annotation is now configured to only time out after 12 seconds.

It should be obvious that I’m using a circuit breaker timeout of 12 seconds as a teaching example. In a distributed environment, I often get nervous if I start hearing comments from development teams that a 1 second timeout on remote service calls is too low because their service X takes on average 5-6 seconds.

This usually tells me that unresolved performance problems exist with the service being called. Avoid the temptation to increase the default timeout on Hystrix calls unless you absolutely cannot resolve a slow running service call.

If you do have a situation where part of your service calls are going to take longer than other service calls, definitely look at segregating these service calls into separate thread pools.

5.6. Fallback processing

Part of the beauty of the circuit breaker pattern is that because a “middle man” is between the consumer of a remote resource and the resource itself, you have an opportunity for the developer to intercept a service failure and choose an alternative course of action to take.

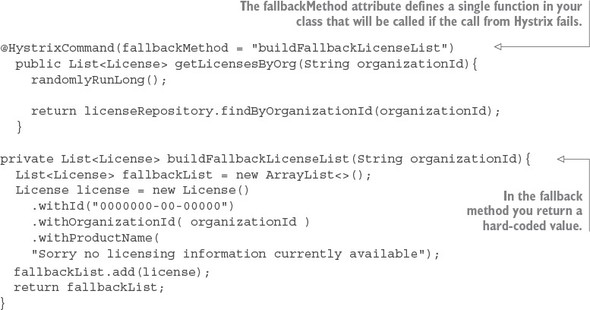

In Hystrix, this is known as a fallback strategy and is easily implemented. Let’s see how to build a simple fallback strategy for your licensing database that simply returns a licensing object that says no licensing information is currently available. The following listing demonstrates this.

Listing 5.5. Implementing a fallback in Hystrix

Note

In the source code from the GitHub repository, I comment out the fallbackMethod line so that you can see the service call randomly fail. To see the fallback code in listing 5.5 in action you’ll need to uncomment out the fallbackMethod attribute. Otherwise, you will never see the fallback actually being invoked.

To implement a fallback strategy with Hystrix you have to do two things. First, you need to add an attribute called fallbackMethod to the @HystrixCommand annotation. This attribute will contain the name of a method that will be called when Hystrix has to interrupt a call because it’s taking too long.

The second thing you need to do is define a fallback method to be executed. This fallback method must reside in the same class as the original method that was protected by the @HystrixCommand. The fallback method must have the exact same method signature as the originating function as all of the parameters passed into the original method protected by the @HystrixCommand will be passed to the fallback.

In the example in listing 5.5, the fallback method buildFallbackLicense-List() is simply constructing a single License object containing dummy information. You could have your fallback method read this data from an alternative data source, but for demonstration purposes you’re going to construct a list that would have been returned by your original function call.

The fallback strategy works extremely well in situations where your microservice is retrieving data and the call fails. In one organization I worked at, we had customer information stored in an operational data store (ODS) and also summarized in a data warehouse.

Our happy path was to always retrieve the most recent data and calculate summary information for it on the fly. However, after a particularly nasty outage where a slow database connection took down multiple services, we decided to protect the service call that retrieved and summarized the customer’s information with a Hystrix fallback implementation. If the call to the ODS failed due to a performance problem or an error, we used a fallback to retrieve the summarized data from our data warehouse tables.

Our business team decided that giving the customer’s older data was preferable to having the customer see an error or have the entire application crash. The key when choosing whether to use a fallback strategy is the level of tolerance your customers have to the age of their data and how important it is to never let them see the application having problems.

Here are a few things to keep in mind as you determine whether you want to implement a fallback strategy:

- Fallbacks are a mechanism to provide a course of action when a resource has timed out or failed. If you find yourself using fallbacks to catch a timeout exception and then doing nothing more than logging the error, then you should probably use a standard try.. catch block around your service invocation, catch the HystrixRuntimeException, and put the logging logic in the try..catch block.

- Be aware of the actions you’re taking with your fallback functions. If you call out to another distributed service in your fallback service you may need to wrap the fallback with a @HystrixCommand annotation. Remember, the same failure that you’re experiencing with your primary course of action might also impact your secondary fallback option. Code defensively. I have been bitten hard when I failed to take this into account when using fallbacks.

Now that you have your fallback in place, go ahead and call your endpoint again. This time when you hit it and encounter a timeout error (remember you have a one in 3 chance) you shouldn’t get an exception back from the service call, but instead have the dummy license values returned.

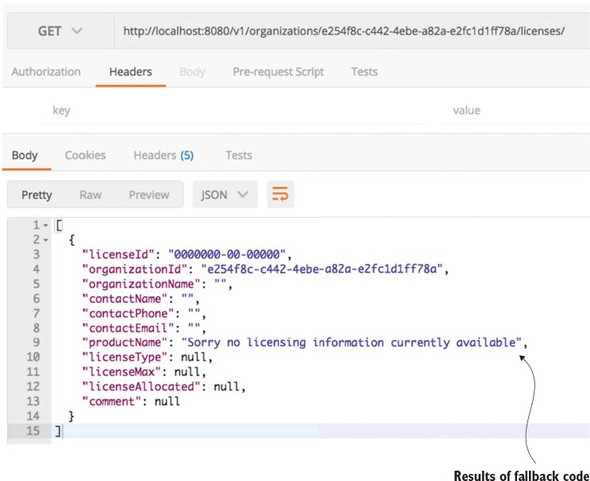

Figure 5.6. Your service invocation using a Hystrix fallback

5.7. Implementing the bulkhead pattern

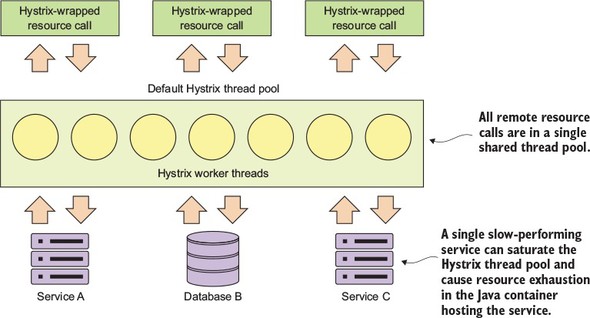

In a microservice-based application you’ll often need to call multiple microservices to complete a particular task. Without using a bulkhead pattern, the default behavior for these calls is that the calls are executed using the same threads that are reserved for handling requests for the entire Java container. In high volumes, performance problems with one service out of many can result in all of the threads for the Java container being maxed out and waiting to process work, while new requests for work back up. The Java container will eventually crash. The bulkhead pattern segregates remote resource calls in their own thread pools so that a single misbehaving service can be contained and not crash the container.

Hystrix uses a thread pool to delegate all requests for remote services. By default, all Hystrix commands will share the same thread pool to process requests. This thread pool will have 10 threads in it to process remote service calls and those remote services calls could be anything, including REST-service invocations, database calls, and so on. Figure 5.7 illustrates this.

Figure 5.7. Default Hystrix thread pool shared across multiple resource types

This model works fine when you have a small number of remote resources being accessed within an application and the call volumes for the individual services are relatively evenly distributed. The problem is if you have services that have far higher volumes or longer completion times then other services, you can end up introducing thread exhaustion into your Hystrix thread pools because one service ends up dominating all of the threads in the default thread pool.

Fortunately, Hystrix provides an easy-to-use mechanism for creating bulkheads between different remote resource calls. Figure 5.8 shows what Hystrix managed resources look like when they’re segregated into their own “bulkheads.”

Figure 5.8. Hystrix command tied to segregated thread pools

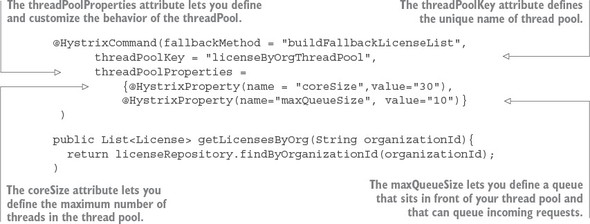

To implement segregated thread pools, you need to use additional attributes exposed through the @HystrixCommand annotation. Let’s look at some code that will

- Set up a separate thread pool for the getLicensesByOrg() call

- Set the number of threads in the thread pool

- Set the queue size for the number of requests that can queue if the individual threads are busy

The following listing demonstrates how to set up a bulkhead around all calls surrounding the look-up of licensing data from our licensing service.

Listing 5.6. Creating a bulkhead around the getLicensesByOrg() method

The first thing you should notice is that we’ve introduced a new attribute, threadPoolkey, to your @HystrixCommand annotation. This signals to Hystrix that you want to set up a new thread pool. If you set no further values on the thread pool, Hystrix sets up a thread pool keyed off the name in the threadPoolKey attribute, but will use all default values for how the thread pool is configured.

To customize your thread pool, you use the threadPoolProperties attribute on the @HystrixCommand. This attribute takes an array of HystrixProperty objects. These HystrixProperty objects can be used to control the behavior of the thread pool. You can set the size of the thread pool by using the coreSize attribute.

You can also set up a queue in front of the thread pool that will control how many requests will be allowed to back up when the threads in the thread pool are busy. This queue size is set by the maxQueueSize attribute. Once the number of requests exceeds the queue size, any additional requests to the thread pool will fail until there is room in the queue.

Note two things about the maxQueueSize attribute. First, if you set the value to -1, a Java SynchronousQueue will be used to hold all incoming requests. A synchronous queue will essentially enforce that you can never have more requests in process then the number of threads available in the thread pool. Setting the maxQueueSize to a value greater than one will cause Hystrix to use a Java LinkedBlockingQueue. The use of a LinkedBlockingQueue allows the developer to queue up requests even if all threads are busy processing requests.

The second thing to note is that the maxQueueSize attribute can only be set when the thread pool is first initialized (for example, at startup of the application). Hystrix does allow you to dynamically change the size of the queue by using the queueSizeRejectionThreshold attribute, but this attribute can only be set when the maxQueueSize attribute is a value greater than 0.

What’s the proper sizing for a custom thread pool? Netflix recommends the following formula:

(requests per second at peak when the service is healthy * 99th percentile latency in seconds) + small amount of extra threads for overhead

You often don’t know the performance characteristics of a service until it has been under load. A key indicator that the thread pool properties need to be adjusted is when a service call is timing out even if the targeted remote resource is healthy.

5.8. Getting beyond the basics; fine-tuning Hystrix

At this point we’ve looked at the basic concepts of setting up a circuit breaker and bulkhead pattern using Hystrix. We’re now going to go through and see how to really customize the behavior of the Hystrix’s circuit breaker. Remember, Hystrix does more than time out long-running calls. Hystrix will also monitor the number of times a call fails and if enough calls fail, Hystrix will automatically prevent future calls from reaching the service by failing the call before the requests ever hit the remote resource.

There are two reasons for this. First, if a remote resource is having performance problems, failing fast will prevent the calling application from having to wait for a call to time out. This significantly reduces the risk that the calling application or service will experience its own resource exhaustion problems and crashes. Second, failing fast and preventing calls from service clients will help a struggling service keep up with its load and not crash completely under the load. Failing fast gives the system experiencing performance degradation time to recover.

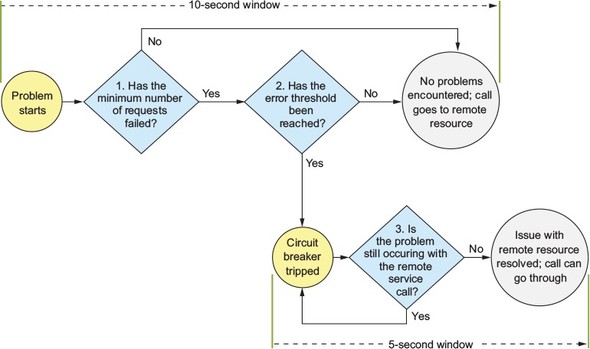

To understand how to configure the circuit breaker in Hystrix, you need to first understand the flow of how Hystrix determines when to trip the circuit breaker. Figure 5.9 shows the decision process used by Hystrix when a remote resource call fails.

Figure 5.9. Hystrix goes through a series of checks to determine whether or not to trip the circuit breaker.

Whenever a Hystrix command encounters an error with a service, it will begin a 10-second timer that will be used to examine how often the service call is failing. This 10-second window is configurable. The first thing Hystrix does is look at the number of calls that have happened within the 10-second window. If the number of calls is less than a minimum number of calls that need to occur within the window, then Hystrix will not take action even if several of the calls failed. For example, the default number of calls that need to occur before Hystrix will even consider action within the 10-second window is 20. If 15 of those calls fail within a 10-second period, not enough of the calls have occurred for them to “trip” the circuit breaker even if all 15 calls failed. Hystrix will continue letting calls go through to the remote service.

When the minimum number of remote resource calls has occurred within the 10-second window, Hystrix will begin looking at the percentage of overall failures that have occurred. If the overall percentage of failures is over the threshold, Hystrix will trigger the circuit breaker and fail almost all future calls. As we’ll discuss shortly, Hystrix will let part of the calls through to “test” and see if the service is backing up. The default value for the error threshold is 50%.

If that percentage has been exceeded, Hystrix will “trip” the circuit breaker and prevent further calls from hitting the remote resource. If that percentage of remote calls hasn’t been triggered and the 10-second window has been passed, Hystrix will reset the circuit breaker statistics.

When Hystrix has “tripped” the circuit breaker on a remote call, it will try to start a new window of activity. Every five seconds (this value is configurable), Hystrix will let a call through to the struggling service. If the call succeeds, Hystrix will reset the circuit breaker and start letting calls through again. If the call fails, Hystrix will keep the circuit breaker closed and try again in another five seconds.

Based on this, you can see that there are five attributes you can use to customize the circuit breaker behavior. The @HystrixCommand annotation exposes these five attributes via the commandPoolProperties attribute. While the threadPoolProperties attribute allows you to set the behavior of the underlying thread pool used in the Hystrix command, the commandPoolProperties attribute allows you to customize the behavior of the circuit breaker associated with Hystrix command. The following listing shows the names of the attributes along with how to set values in each of them.

Listing 5.7. Configuring the behavior of a circuit breaker

@HystrixCommand(

fallbackMethod = "buildFallbackLicenseList",

threadPoolKey = "licenseByOrgThreadPool",

threadPoolProperties ={

@HystrixProperty(name = "coreSize",value="30"),

@HystrixProperty(name="maxQueueSize"value="10"),

},

commandPoolProperties ={

@HystrixProperty(

name="circuitBreaker.requestVolumeThreshold",

value="10"),

value="10"),

@HystrixProperty(

name="circuitBreaker.errorThresholdPercentage",

@HystrixProperty(

name="circuitBreaker.errorThresholdPercentage",

value="75"),

@HystrixProperty(

name="circuitBreaker.sleepWindowInMilliseconds",

value="7000"),

value="75"),

@HystrixProperty(

name="circuitBreaker.sleepWindowInMilliseconds",

value="7000"),

@HystrixProperty(

name="metrics.rollingStats.timeInMilliseconds",

@HystrixProperty(

name="metrics.rollingStats.timeInMilliseconds",

value="15000")

@HystrixProperty(

name="metrics.rollingStats.numBuckets",

value="15000")

@HystrixProperty(

name="metrics.rollingStats.numBuckets",

value="5")}

)

public List<License> getLicensesByOrg(String organizationId){

value="5")}

)

public List<License> getLicensesByOrg(String organizationId){

logger.debug("getLicensesByOrg Correlation id: {}",

logger.debug("getLicensesByOrg Correlation id: {}",

UserContextHolder

.getContext()

.getCorrelationId());

randomlyRunLong();

return licenseRepository.findByOrganizationId(organizationId);

}

UserContextHolder

.getContext()

.getCorrelationId());

randomlyRunLong();

return licenseRepository.findByOrganizationId(organizationId);

}

The first property, circuitBreaker.requestVolumeTheshold, controls the amount of consecutive calls that must occur within a 10-second window before Hystrix will consider tripping the circuit breaker for the call. The second property, circuitBreaker.errorThresholdPercentage, is the percentage of calls that must fail (due to timeouts, an exception being thrown, or a HTTP 500 being returned) after the circuitBreaker.requestVolumeThreshold value has been passed before the circuit breaker it tripped. The last property in the previous code example, circuitBreaker.sleepWindowInMilliseconds, is the amount of time Hystrix will sleep once the circuit breaker is tripped before Hystrix will allow another call through to see if the service is healthy again.

The last two Hystrix properties (metrics.rollingStats.timeInMilliseconds and metrics.rollingStats.numBuckets) are named a bit differently than the previous properties, but they still control the behavior of the circuit breaker. The first property, metrics.rollingStats.timeInMilliseconds, is used to control the size of the window that will be used by Hystrix to monitor for problems with a service call. The default value for this is 10,000 milliseconds (that is, 10 seconds).

The second property, metrics.rollingStats.numBuckets, controls the number of times statistics are collected in the window you’ve defined. Hystrix collects metrics in buckets during this window and checks the stats in those buckets to determine if the remote resource call is failing. The number of buckets defined must evenly divide into the overall number of milliseconds set for rollingStatus.inMilliseconds stats. For example, in your custom settings in the previous listing, Hystrix will use a 15-second window and collect statistics data into five buckets of three seconds in length.

Note

The smaller the statistics window you check in and the greater the number of buckets you keep within the window will drive up CPU and memory utilization on a high-volume service. Be aware of this and fight the temptation to set the metrics collection windows and buckets to be fine-grained until you need that level of visibility.

5.8.1. Hystrix configuration revisited

The Hystrix library is extremely configurable and lets you tightly control the behavior of the circuit breaker and bulkhead patterns you define with it. By modifying the configuration of a Hystrix circuit breaker, you can control the amount of time Hystrix will wait before timing out a remote call. You can also control the behavior of when a Hystrix circuit breaker will trip and when Hystrix tries to reset the circuit breaker.

With Hystrix you can also fine-tune your bulkhead implementations by defining individual thread groups for each remote service call and then configure the number of threads associated with each thread group. This allows you to fine-tune your remote service calls because certain calls will have higher volumes then others, while other remote resource calls will have higher volumes.

The key thing to remember as you look at configuring your Hystrix environment is that you have three levels of configuration with Hystrix:

- Default for the entire application

- Default for the class

- Thread-pool level defined within the class

Every Hystrix property has values set by default that will be used by every @HystrixCommand annotation in the application unless they’re set at the Java class level or overridden for individual Hystrix thread pools within a class.

Hystrix does let you set default parameters at the class level so that all Hystrix commands within a specific class share the same configurations. The class-level properties are set via a class-level annotation called @DefaultProperties. For example, if you wanted all the resources within a specific class to have a timeout of 10 seconds, you could set the @DefaultProperties in the following manner:

@DefaultProperties(

commandProperties = {

@HystrixProperty(

name = "execution.isolation.thread.timeoutInMilliseconds",

value = "10000")}

class MyService { ... }

name = "execution.isolation.thread.timeoutInMilliseconds",

value = "10000")}

class MyService { ... }

Unless explicitly overridden at a thread-pool level, all thread pools will inherit either the default properties at the application level or the default properties defined in the class. The Hystrix threadPoolProperties and commandProperties are also tied to the defined command key.

Note

For the coding examples, I’ve hard-coded all the Hystrix values in the application code. In a production system, the Hystrix data that’s most likely to need to be tweaked (timeout parameters, thread pool counts) would be externalized to Spring Cloud Config. This way if you need to change the parameter values, you could change the values and then restart the service instances without having to recompile and redeploy the application.

For individual Hystrix pools, I will keep the configuration as close to the code as possible and place the thread-pool configuration right in the @HystrixCommand annotation. Table 5.1 summarizes all of the configuration values used to set up and configure our @HystrixCommand annotations.

Table 5.1. Configuration Values for @HystrixCommand Annotations

|

Property Name |

Default Value |

Description |

|---|---|---|

| fallbackMethod | None | Identifies the method within the class that will be called if the remote call times out. The callback method must be in the same class as the @HystrixCommand annotation and must have the same method signature as the calling class. If no value, an exception will be thrown by Hystrix. |

| threadPoolKey | None | Gives the @HystrixCommand a unique name and creates a thread pool that is independent of the default thread pool. If no value is defined, the default Hystrix thread pool will be used. |

| threadPoolProperties | None | Core Hystrix annotation attribute that’s used to configure the behavior of a thread pool. |

| coreSize | 10 | Sets the size of the thread pool. |

| maxQueueSize | -1 | Maximum queue size that will set in front of the thread pool. If set to -1, no queue is used and instead Hystrix will block until a thread becomes available for processing. |

| circuitBreaker.request-VolumeThreshold | 20 | Sets the minimum number of requests that must be processed within the rolling window before Hystrix will even begin examining whether the circuit breaker will be tripped. Note: This value can only be set with the commandPoolProperties attribute. |

| circuitBreaker.error-ThresholdPercentage | 50 | The percentage of failures that must occur within the rolling window before the circuit breaker is tripped. Note: This value can only be set with the commandPoolProperties attribute. |

| circuitBreaker.sleep-WindowInMilliseconds | 5,000 | The number of milliseconds Hystrix will wait before trying a service call after the circuit breaker has been tripped. Note: This value can only be set with the commandPoolProperties attribute. |

| metricsRollingStats.timeInMilliseconds | 10,000 | The number of milliseconds Hystrix will collect and monitor statistics about service calls within a window. |

| metricsRollingStats.numBuckets | 10 | The number of metrics buckets Hystrix will maintain within its monitoring window. The more buckets within the monitoring window, the lower the level of time Hystrix will monitor for faults within the window. |

5.9. Thread context and Hystrix

When an @HystrixCommand is executed, it can be run with two different isolation strategies: THREAD and SEMAPHORE. By default, Hystrix runs with a THREAD isolation. Each Hystrix command used to protect a call runs in an isolated thread pool that doesn’t share its context with the parent thread making the call. This means Hystrix can interrupt the execution of a thread under its control without worrying about interrupting any other activity associated with the parent thread doing the original invocation.

With SEMAPHORE-based isolation, Hystrix manages the distributed call protected by the @HystrixCommand annotation without starting a new thread and will interrupt the parent thread if the call times out. In a synchronous container server environment (Tomcat), interrupting the parent thread will cause an exception to be thrown that cannot be caught by the developer. This can lead to unexpected consequences for the developer writing the code because they can’t catch the thrown exception or do any resource cleanup or error handling.

To control the isolation setting for a command pool, you can set a command-Properties attribute on your @HystrixCommand annotation. For instance, if you wanted to set the isolation level on a Hystrix command to use a SEMAPHORE isolation, you’d use

@HystrixCommand(

commandProperties = {

@HystrixProperty(

name="execution.isolation.strategy", value="SEMAPHORE")})

Note

By default, the Hystrix team recommends you use the default isolation strategy of THREAD for most commands. This keeps a higher level of isolation between you and the parent thread. THREAD isolation is heavier than using the SEMAPHORE isolation. The SEMAPHORE isolation model is lighter-weight and should be used when you have a high-volume on your services and are running in an asynchronous I/O programming model (you are using an asynchronous I/O container such as Netty).

5.9.1. ThreadLocal and Hystrix

Hystrix, by default, will not propagate the parent thread’s context to threads managed by a Hystrix command. For example, any values set as ThreadLocal values in the parent thread will not be available by default to a method called by the parent thread and protected by the @HystrixCommand object. (Again, this is assuming you are using a THREAD isolation level.)

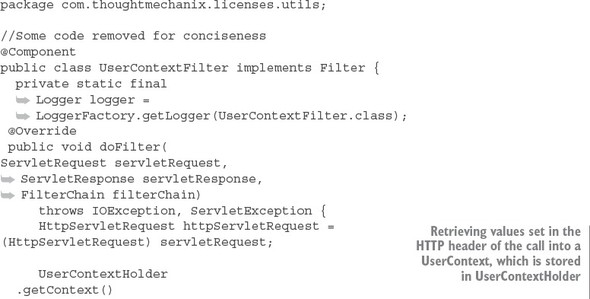

This can be a little obtuse, so let’s see a concrete example. Often in a REST-based environment you are going to want to pass contextual information to a service call that will help you operationally manage the service. For example, you might pass a correlation ID or authentication token in the HTTP header of the REST call that can then be propagated to any downstream service calls. The correlation ID allows you to have a unique identifier that can be traced across multiple service calls in a single transaction.

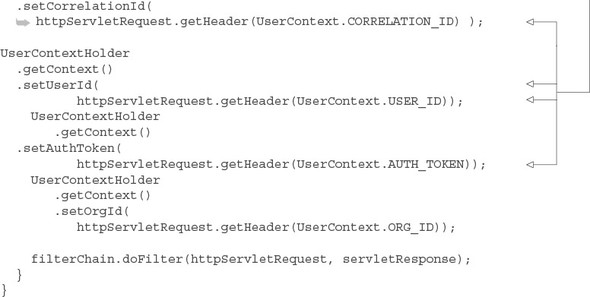

To make this value available anywhere in your service call, you might use a Spring Filter class to intercept every call into your REST service and retrieve this information from the incoming HTTP request and store this contextual information in a custom UserContext object. Then, anytime your code needs to access this value in your REST service call, your code can retrieve the UserContext from the ThreadLocal storage variable and read the value. The following listing shows an example Spring Filter that you can use in your licensing service. You can find the code at licensingservice/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/utils/UserContextFilter.java.

Listing 5.8. The UserContextFilter parsing the HTTP header and retrieving data

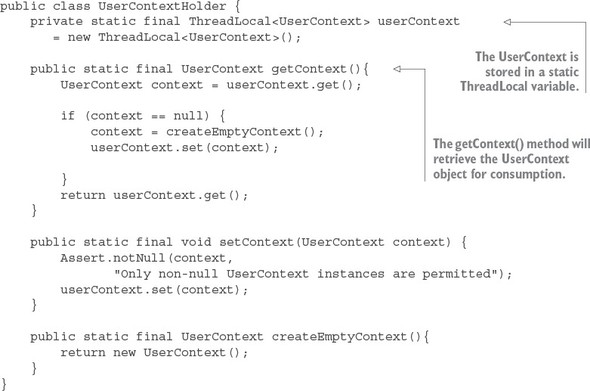

The UserContextHolder class is used to store the UserContext in a ThreadLocal class. Once it’s stored in the ThreadLocal storage, any code that’s executed for a request will use the UserContext object stored in the UserContextHolder. The UserContextHolder class is shown in the following listing. This class is found at licensing-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/utils/UserContextHolder.java.

Listing 5.9. All UserContext data is managed by UserContextHolder

At this point you can add a couple of log statements to your licensing service. You’ll add logging to the following licensing service classes and methods:

- com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/utils/UserContextFilter.java doFilter() method

- com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/controllers/LicenseService-Controller.java getLicenses() method

- com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/services/LicenseService.java getLicensesByOrg() method. This method is annotated with a @HystrixCommand.

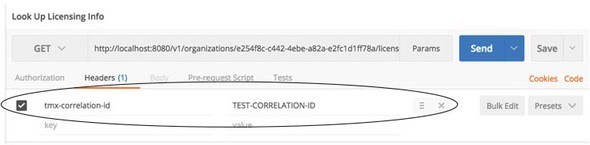

Next you’ll call your service passing in a correlation ID using an HTTP header called tmx-correlation-id and a value of TEST-CORRELATION-ID. Figure 5.10 shows a HTTP GET call to http://localhost:8080/v1/organizations/e254f8c-c442-4ebe-a82a-e2fc1d1ff78a/licenses/ in Postman.

Figure 5.10. Adding a correlation ID to the licensing service call’s HTTP header

Once this call is submitted, you should see three log messages writing out the passed-in correlation ID as it flows through the UserContext, LicenseServiceController, and LicenseServer classes:

UserContext Correlation id: TEST-CORRELATION-ID LicenseServiceController Correlation id: TEST-CORRELATION-ID LicenseService.getLicenseByOrg Correlation:

As expected, once the call hits the Hystrix protected method on License-Service.getLicensesByOrder(), you’ll get no value written out for the correlation ID. Fortunately, Hystrix and Spring Cloud offer a mechanism to propagate the parent thread’s context to threads managed by the Hystrix Thread pool. This mechanism is called a HystrixConcurrencyStrategy.

5.9.2. The HystrixConcurrencyStrategy in action

Hystrix allows you to define a custom concurrency strategy that will wrap your Hystrix calls and allows you to inject any additional parent thread context into the threads managed by the Hystrix command. To implement a custom HystrixConcurrency-Strategy you need to carry out three actions:

- Define your custom Hystrix Concurrency Strategy class

- Define a Java Callable class to inject the UserContext into the Hystrix Command

- Configure Spring Cloud to use your custom Hystrix Concurrency Strategy

All the examples for the HystrixConcurrencyStrategy can be found in the licensing-service/src/main/java/com/thoughtmechanix/licenses/hystrix package.

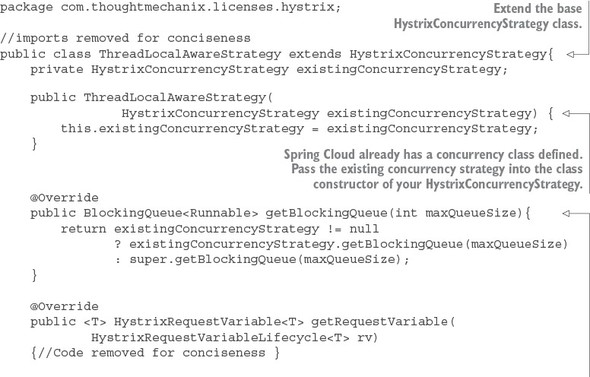

Define your custom Hystrix concurrency strategy class

The first thing you need to do is define your HystrixConcurrencyStrategy. By default, Hystrix only allows you to define one HystrixConcurrencyStrategy for an application. Spring Cloud already defines a concurrency strategy used to handle propagating Spring security information. Fortunately, Spring Cloud allows you to chain together Hystrix concurrency strategies so you can define and use your own concurrency strategy by “plugging” it into the Hystrix concurrency strategy.

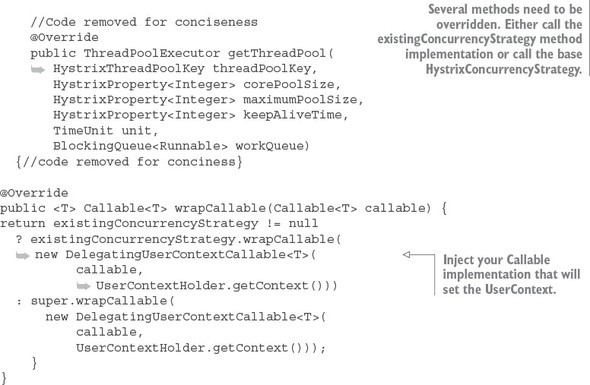

Our implementation of a Hystrix concurrency strategy can be found in the licensing services hystrix package and is called ThreadLocalAwareStrategy.java. The following listing shows the code for this class.

Listing 5.10. Defining your own Hystrix concurrency strategy

Note a couple of things in the class implementation in listing 5.10. First, because Spring Cloud already defines a HystrixConcurrencyStrategy, every method that could be overridden needs to check whether an existing concurrency strategy is present and then either call the existing concurrency strategy’s method or the base Hystrix concurrency strategy method. You have to do this as a convention to ensure that you properly invoke the already-existing Spring Cloud’s HystrixConcurrency-Strategy that deals with security. Otherwise, you can have nasty behavior when trying to use Spring security context in your Hystrix protected code.

The second thing to note is the wrapCallable() method in listing 5.11. In this method, you pass in Callable implementation, DelegatingUserContext-Callable, that will be used to set the UserContext from the parent thread executing the user’s REST service call to the Hystrix command thread protecting the method that’s doing the work within.

Define a Java Callable class to inject the UserContext into the Hystrix command

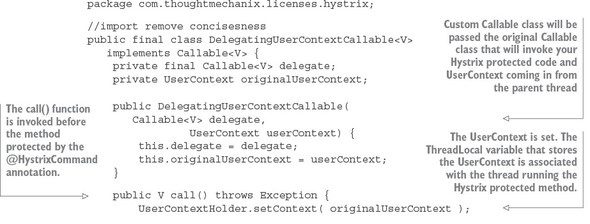

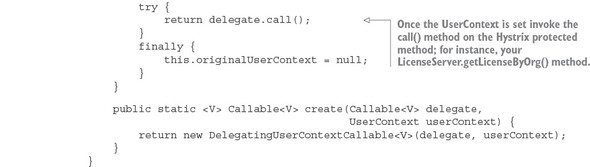

The next step in propagating the thread context of the parent thread to your Hystrix command is to implement the Callable class that will do the propagation. For this example, this call is in the hystrix package and is called DelegatingUser-ContextCallable.java. The following listing shows the code from this class.

Listing 5.11. Propagating the UserContext with DelegatingUserContextCallable.java

When a call is made to a Hystrix protected method, Hystrix and Spring Cloud will instantiate an instance of the DelegatingUserContextCallable class, passing in the Callable class that would normally be invoked by a thread managed by a Hystrix command pool. In the previous listing, this Callable class is stored in a Java property called delegate. Conceptually, you can think of the delegate property as being the handle to the method protected by a @HystrixCommand annotation.

In addition to the delegated Callable class, Spring Cloud is also passing along the UserContext object off the parent thread that initiated the call. With these two values set at the time the DelegatingUserContextCallable instance is created, the real action will occur in the call() method of your class.

The first thing to do in the call() method is set the UserContext via the UserContextHolder.setContext() method. Remember, the setContext() method stores a UserContext object in a ThreadLocal variable specific to the thread being run. Once the UserContext is set, you then invoke the call() method of the delegated Callable class. This call to delegate.call() invokes the method protected by the @HystrixCommand annotation.

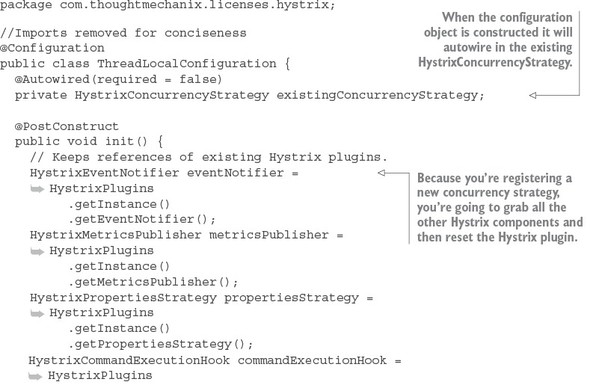

Configure Spring Cloud to use your custom Hystrix concurrency strategy

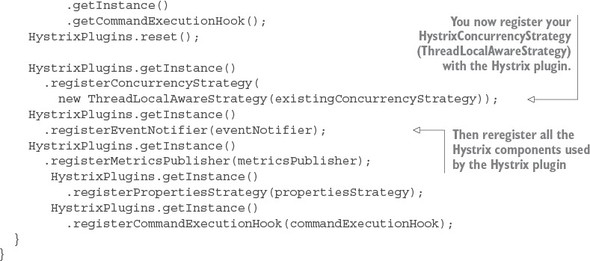

Now that you have your HystrixConcurrencyStrategy via the ThreadLocal-AwareStrategy class and your Callable class defined via the DelegatingUserContextCallable class, you need to hook them in Spring Cloud and Hystrix. To do this, you’re going to define a new configuration class. This configuration, called ThreadLocalConfiguration, is shown in the following listing.

Listing 5.12. Hooking custom HystrixConcurrencyStrategy class into Spring Cloud

This Spring configuration class basically rebuilds the Hystrix plugin that manages all the different components running within your service. In the init() method, you’re grabbing references to all the Hystrix components used by the plugin. You then register your custom HystrixConcurrencyStrategy (ThreadLocalAwareStrategy).

HystrixPlugins.getInstance().registerConcurrencyStrategy( new ThreadLocalAwareStrategy(existingConcurrencyStrategy));

Remember, Hystrix allows only one HystrixConcurrencyStrategy. Spring will attempt to autowire in any existing HystrixConcurrencyStrategy (if it exists). Finally, when you’re all done, you re-register the original Hystrix components that you grabbed at the beginning of the init() method back with the Hystrix plugin.

With these pieces in place, you can now rebuild and restart your licensing service and call it via the GET (http://localhost:8080/v1/organizations/e254f8c-c442-4ebe-a82a-e2fc1d1ff78a/licenses/) shown earlier in figure 5.10. Now, when this call is completed, you should see the following output in your console window:

UserContext Correlation id: TEST-CORRELATION-ID LicenseServiceController Correlation id: TEST-CORRELATION-ID LicenseService.getLicenseByOrg Correlation: TEST-CORRELATION-ID

It’s a lot of work to produce one little result, but it’s unfortunately necessary when you use Hystrix with THREAD-level isolation.

5.10. Summary

- When designing highly distributed applications such as a microservice-based application, client resiliency must be taken into account.

- Outright failures of a service (for example, the server crashes) are easy to detect and deal with.

- A single poorly performing service can trigger a cascading effect of resource exhaustion as threads in the calling client are blocked waiting for a service to complete.

- Three core client resiliency patterns are the circuit-breaker pattern, the fallback pattern, and the bulkhead pattern.

- The circuit breaker pattern seeks to kill slow-running and degraded system calls so that the calls fail fast and prevent resource exhaustion.

- The fallback pattern allows you as the developer to define alternative code paths in the event that a remote service call fails or the circuit breaker for the call fails.

- The bulk head pattern segregates remote resource calls away from each other, isolating calls to a remote service into their own thread pool. If one set of service calls is failing, its failures shouldn’t be allowed to eat up all the resources in the application container.

- Spring Cloud and the Netflix Hystrix libraries provide implementations for the circuit breaker, fallback, and bulkhead patterns.

- The Hystrix libraries are highly configurable and can be set at global, class, and thread pool levels.

- Hystrix supports two isolation models: THREAD and SEMAPHORE.

- Hystrix’s default isolation model, THREAD, completely isolates a Hystrix protected call, but doesn’t propagate the parent thread’s context to the Hystrix managed thread.

- Hystrix’s other isolation model, SEMAPHORE, doesn’t use a separate thread to make a Hystrix call. While this is more efficient, it also exposes the service to unpredictable behavior if Hystrix interrupts the call.

- Hystrix does allow you to inject the parent thread context into a Hystrix managed Thread through a custom HystrixConcurrencyStrategy implementation.