For online information and ordering of this and other Manning books, please visit www.manning.com. The publisher offers discounts on this book when ordered in quantity. For more information, please contact

Special Sales Department Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 Email: orders@manning.com

©2017 by Manning Publications Co. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed

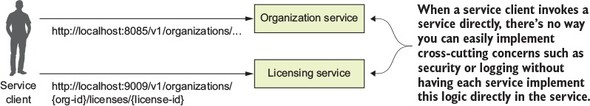

on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources

of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental

chlorine.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed

on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources

of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental

chlorine.

|

Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 |

Acquisition editor: Greg Wild Development editor: Marina Michaels Technical development editor: Raphael Villela Copyeditor: Katie Petito Proofreader: Melody Dolab Technical proofreader: Joshua White Review editor: Aleksandar Dragosavljevic Typesetter: Marija Tudor Cover designer: Marija Tudor

ISBN 9781617293986

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 – EBM – 22 21 20 19 18 17

To my brother Jason, who even in his darkest moments showed me the true meaning of strength and dignity. You are a role model as a brother, husband, and father.

Chapter 1. Welcome to the cloud, Spring

Chapter 2. Building microservices with Spring Boot

Chapter 3. Controlling your configuration with Spring Cloud configuration server

Chapter 4. On service discovery

Chapter 5. When bad things happen: client resiliency patterns with Spring Cloud and Netflix Hystrix

Chapter 6. Service routing with Spring Cloud and Zuul

Chapter 7. Securing your microservices

Chapter 8. Event-driven architecture with Spring Cloud Stream

Chapter 9. Distributed tracing with Spring Cloud Sleuth and Zipkin

Chapter 10. Deploying your microservices

Chapter 1. Welcome to the cloud, Spring

1.2. What is Spring and why is it relevant to microservices?

1.3. What you’ll learn in this book

1.4. Why is this book relevant to you?

1.5. Building a microservice with Spring Boot

1.6. Why change the way we build applications?

1.7. What exactly is the cloud?

1.8. Why the cloud and microservices?

1.9. Microservices are more than writing the code

1.9.1. Core microservice development pattern

1.9.2. Microservice routing patterns

1.9.3. Microservice client resiliency patterns

1.9.4. Microservice security patterns

1.10. Using Spring Cloud in building your microservices

1.10.3. Spring Cloud service discovery

1.10.4. Spring Cloud/Netflix Hystrix and Ribbon

Chapter 2. Building microservices with Spring Boot

2.1. The architect’s story: designing the microservice architecture

2.1.1. Decomposing the business problem

2.2. When not to use microservices

2.3. The developer’s tale: building a microservice with Spring Boot and Java

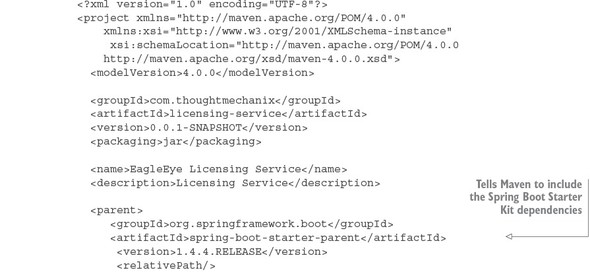

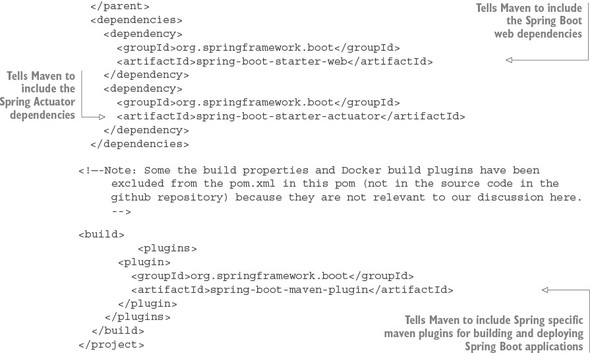

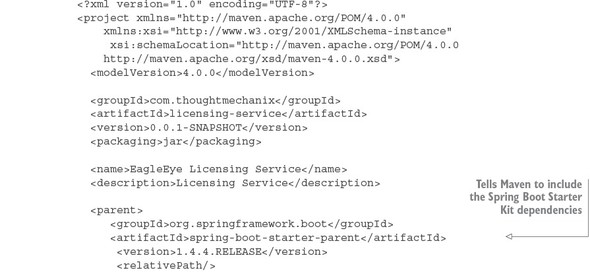

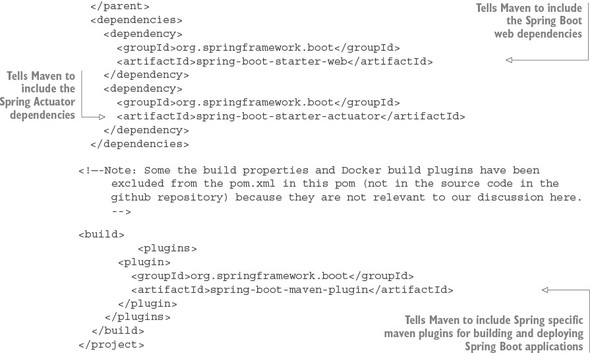

2.3.1. Getting started with the skeleton project

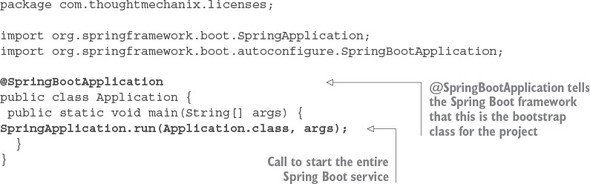

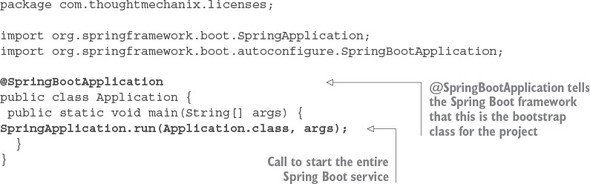

2.3.2. Booting your Spring Boot application: writing the Bootstrap class

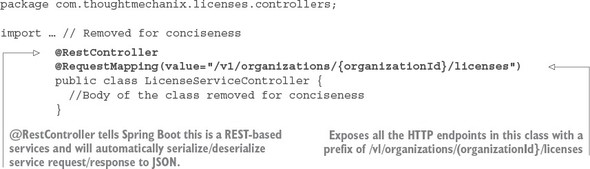

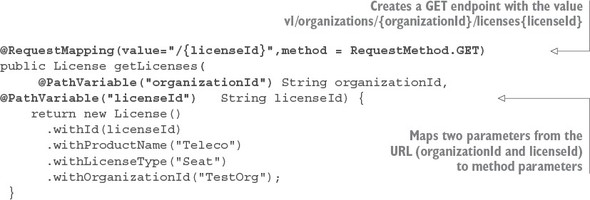

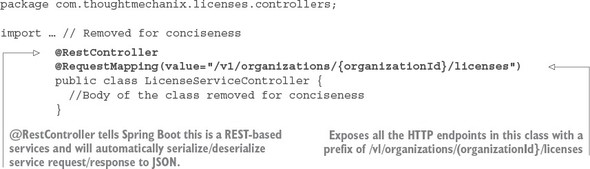

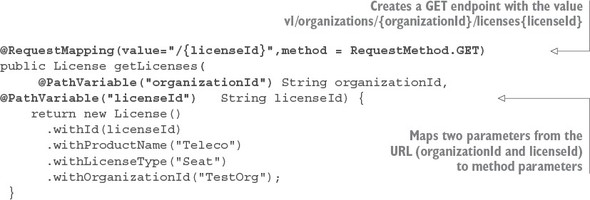

2.3.3. Building the doorway into the microservice: the Spring Boot controller

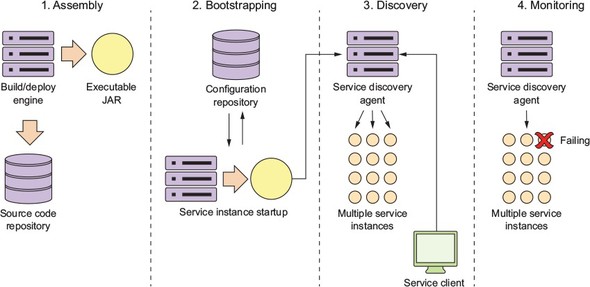

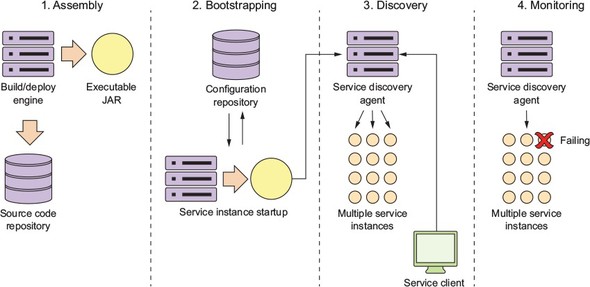

2.4. The DevOps story: building for the rigors of runtime

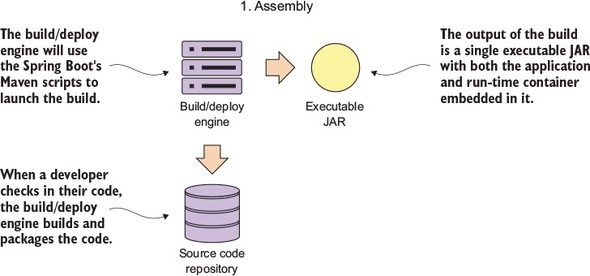

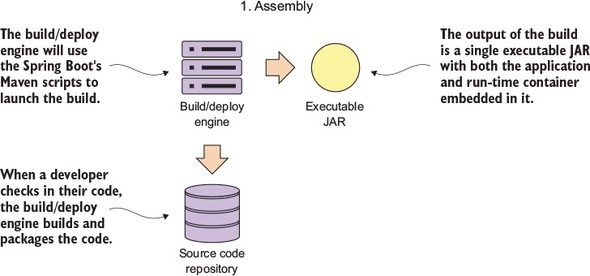

2.4.1. Service assembly: packaging and deploying your microservices

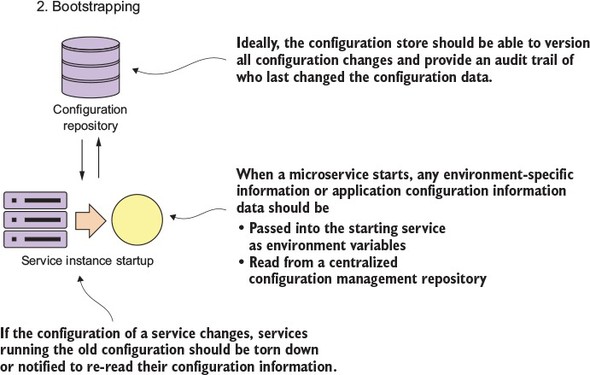

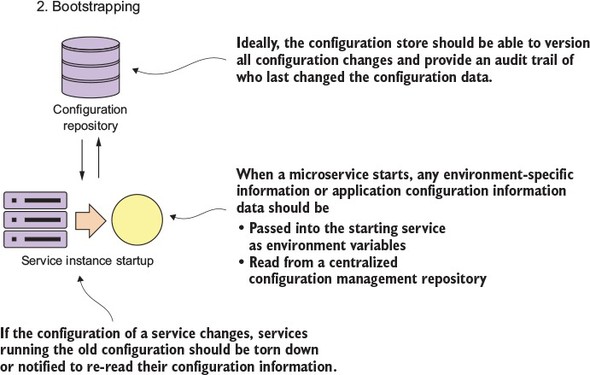

2.4.2. Service bootstrapping: managing configuration of your microservices

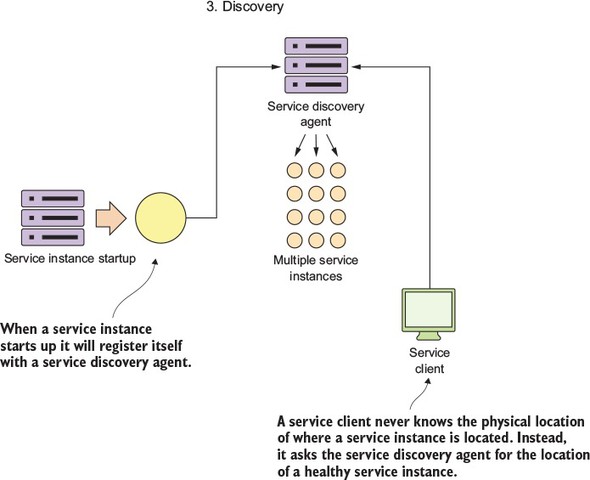

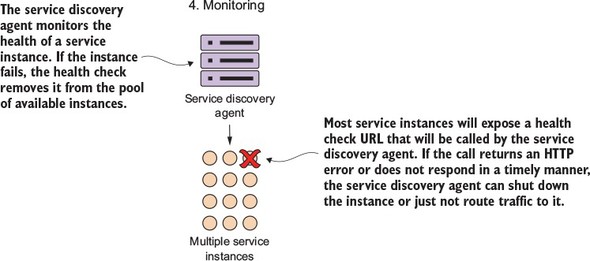

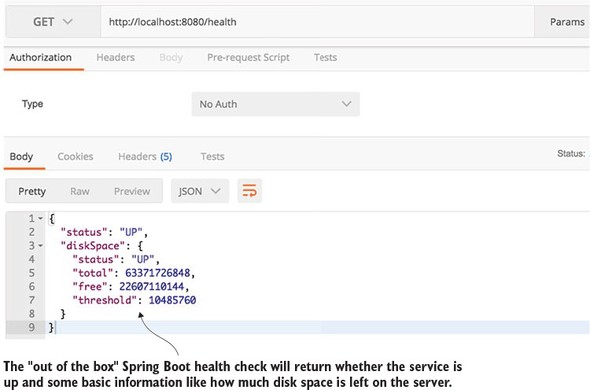

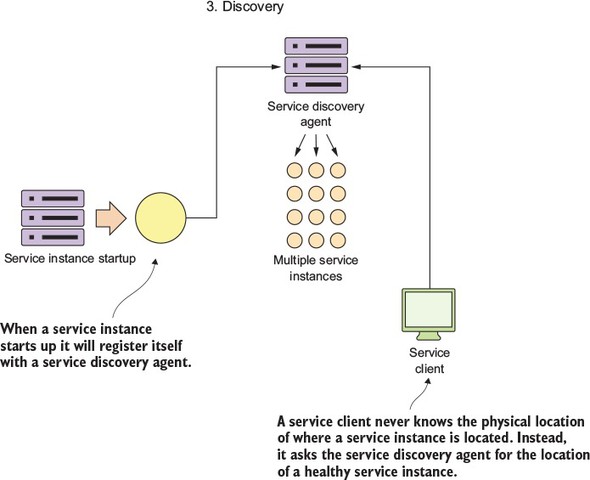

2.4.3. Service registration and discovery: how clients communicate with your microservices

Chapter 3. Controlling your configuration with Spring Cloud configuration server

3.1. On managing configuration (and complexity)

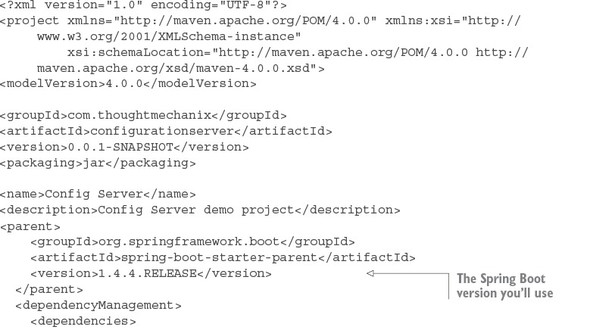

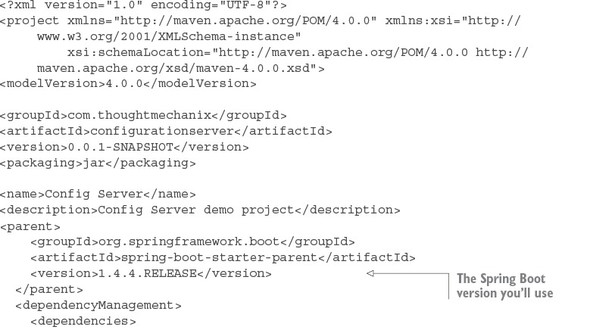

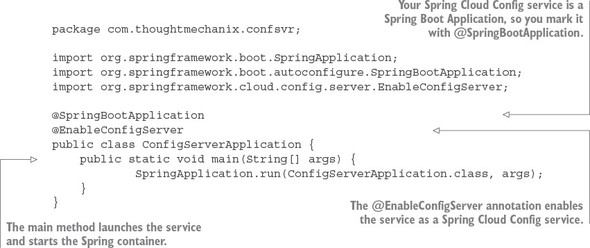

3.2. Building our Spring Cloud configuration server

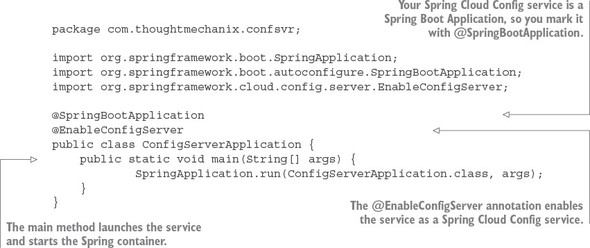

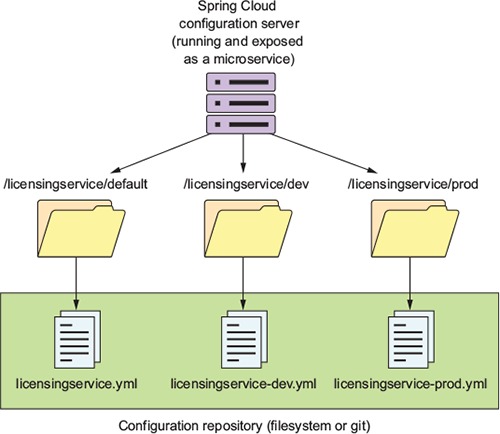

3.2.1. Setting up the Spring Cloud Config Bootstrap class

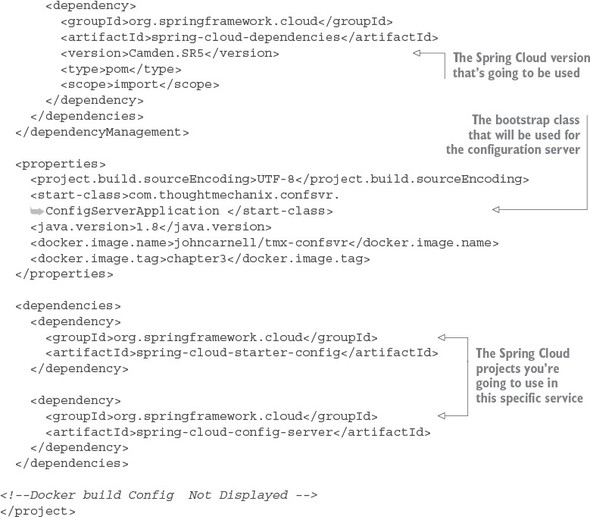

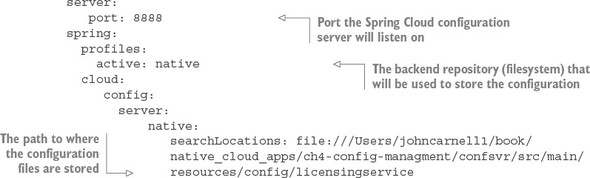

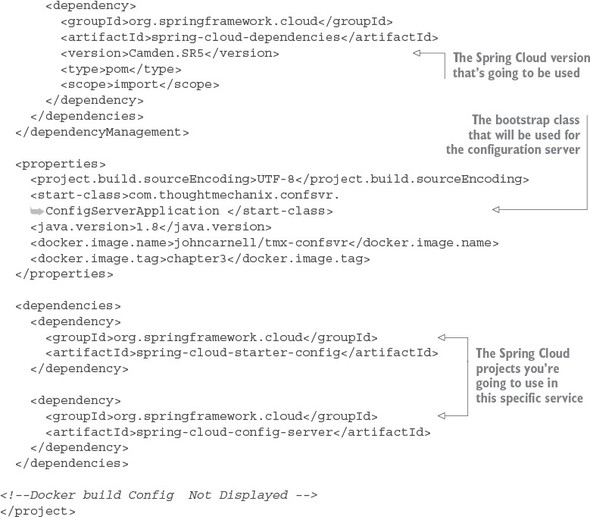

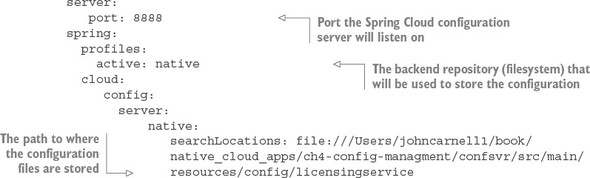

3.2.2. Using Spring Cloud configuration server with the filesystem

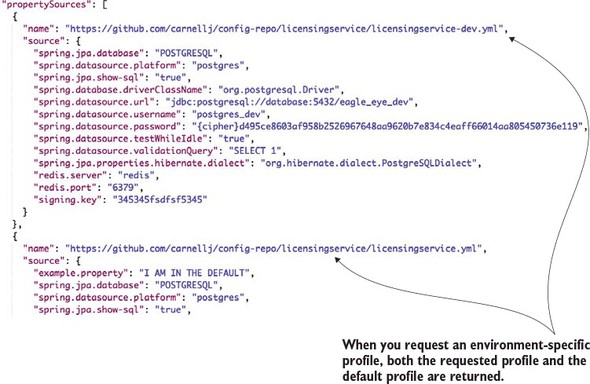

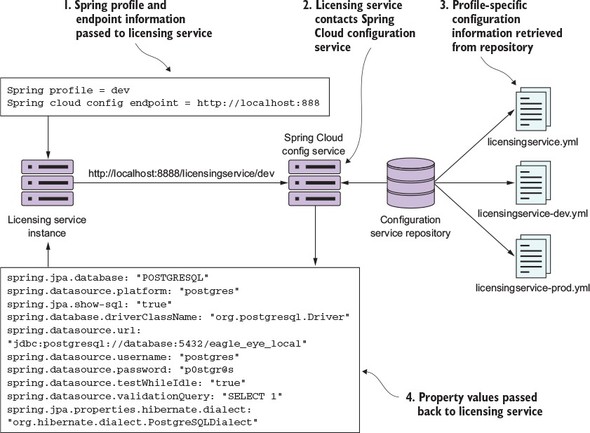

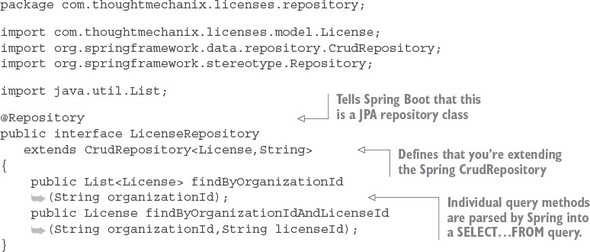

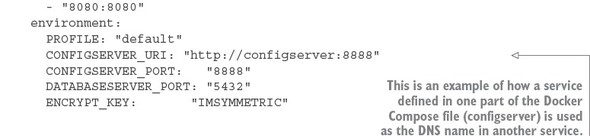

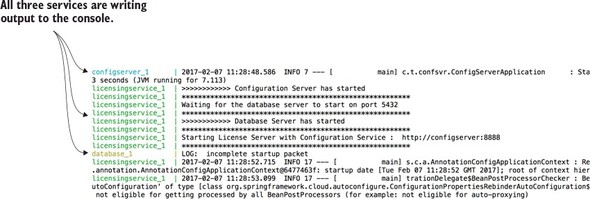

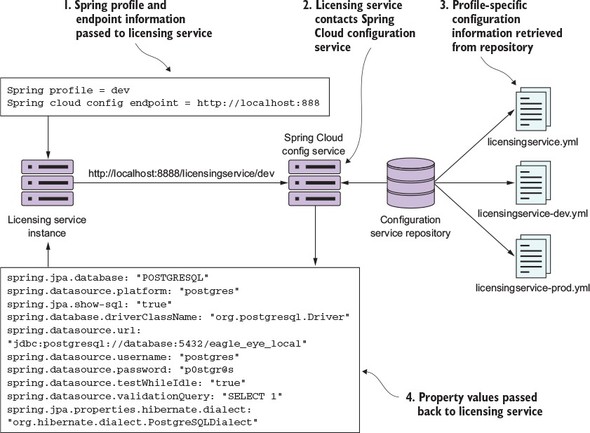

3.3. Integrating Spring Cloud Config with a Spring Boot client

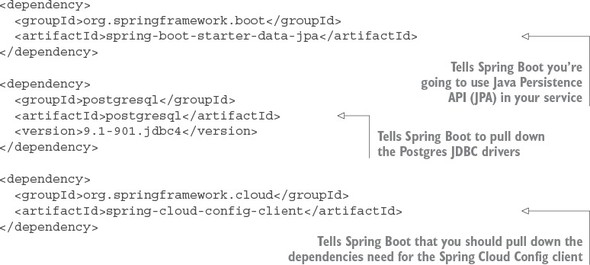

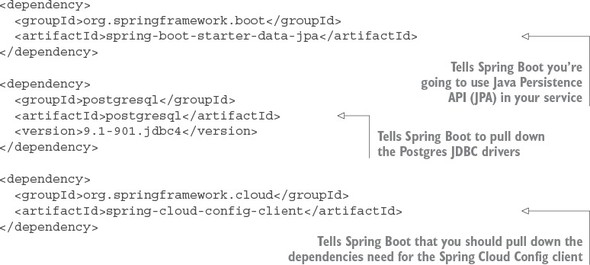

3.3.1. Setting up the licensing service Spring Cloud Config server dependencies

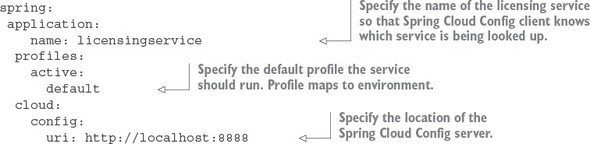

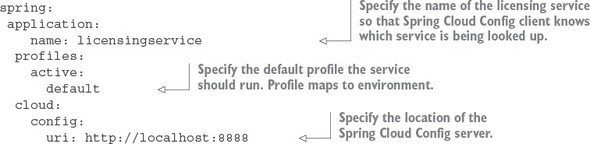

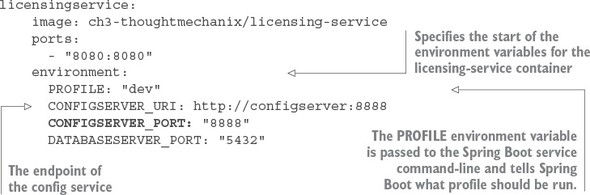

3.3.2. Configuring the licensing service to use Spring Cloud Config

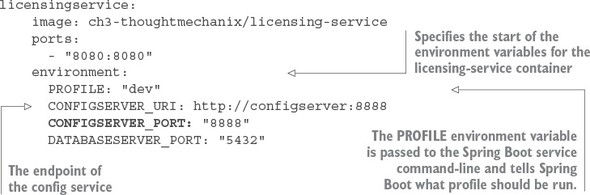

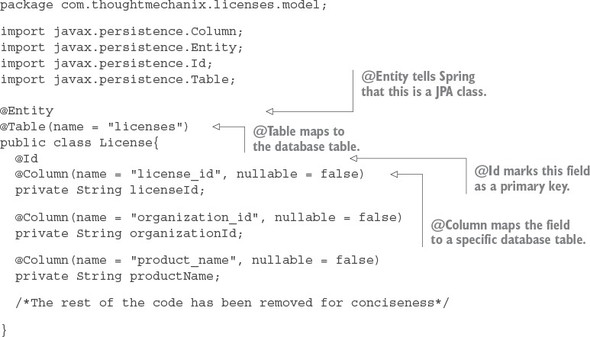

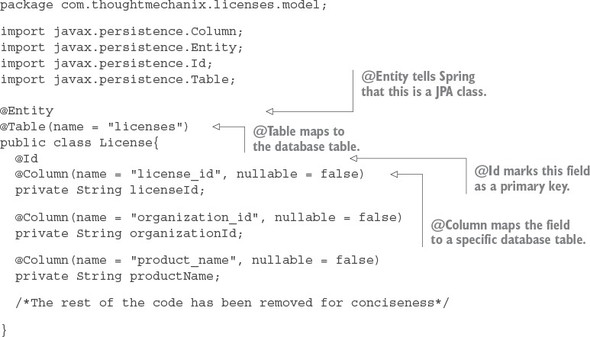

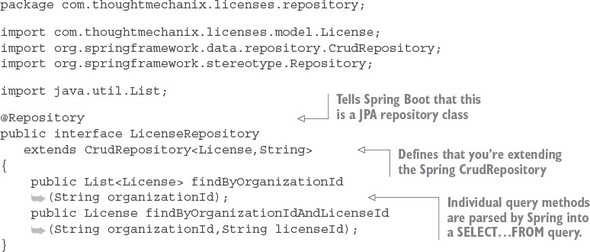

3.3.3. Wiring in a data source using Spring Cloud configuration server

3.3.4. Directly Reading Properties using the @Value Annotation

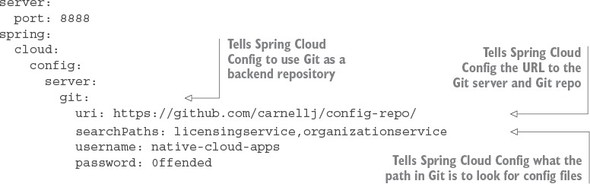

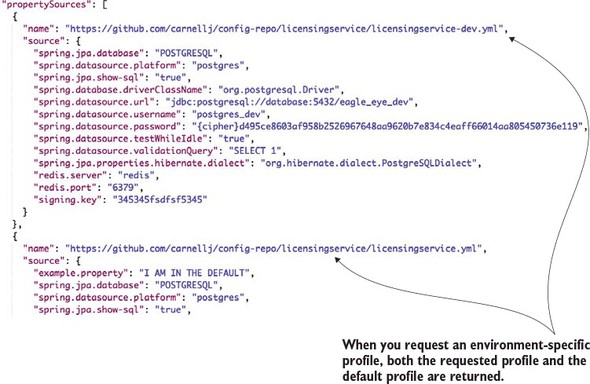

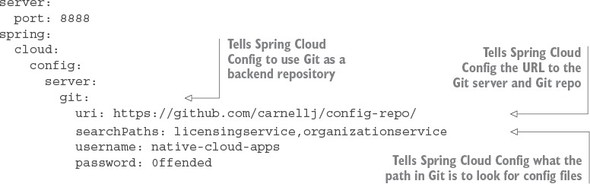

3.3.5. Using Spring Cloud configuration server with Git

3.3.6. Refreshing your properties using Spring Cloud configuration server

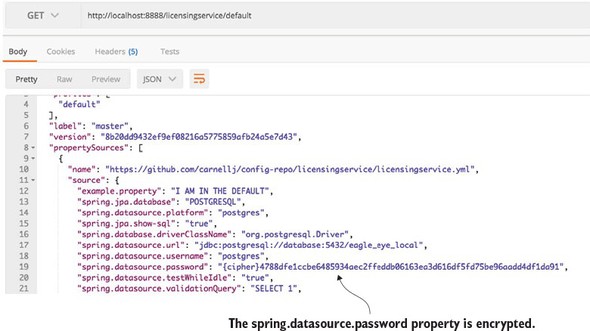

3.4. Protecting sensitive configuration information

3.4.1. Download and install Oracle JCE jars needed for encryption

3.4.2. Setting up an encryption key

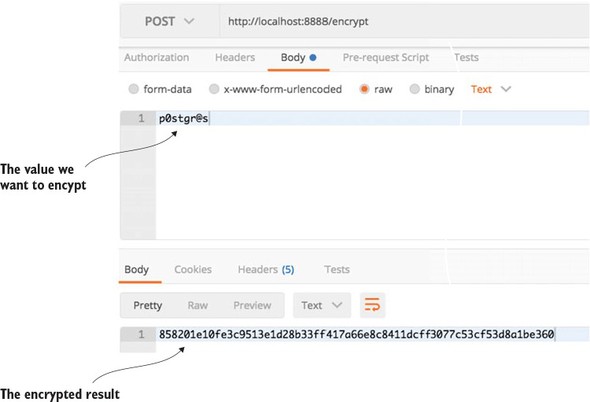

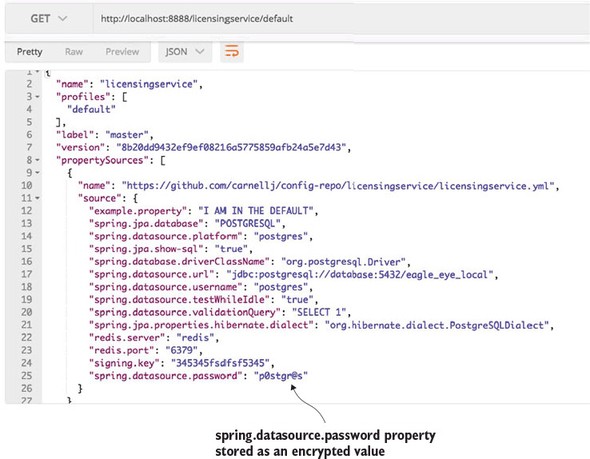

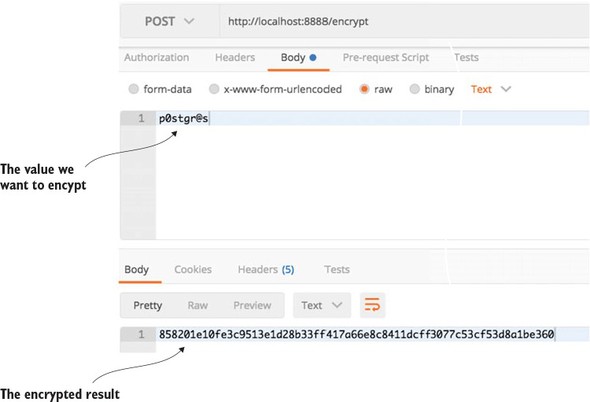

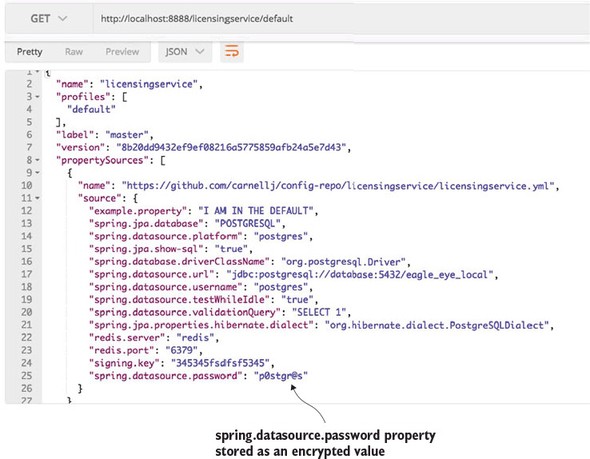

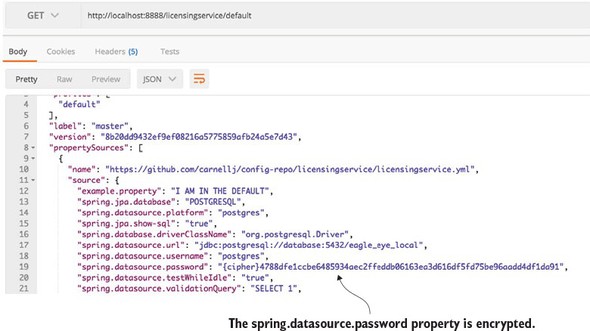

3.4.3. Encrypting and decrypting a property

3.4.4. Configure microservices to use encryption on the client side

Chapter 4. On service discovery

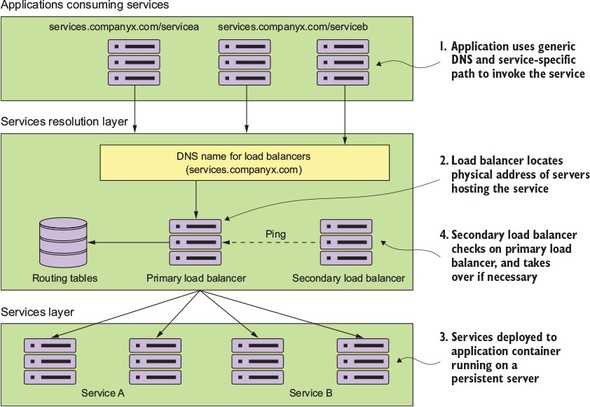

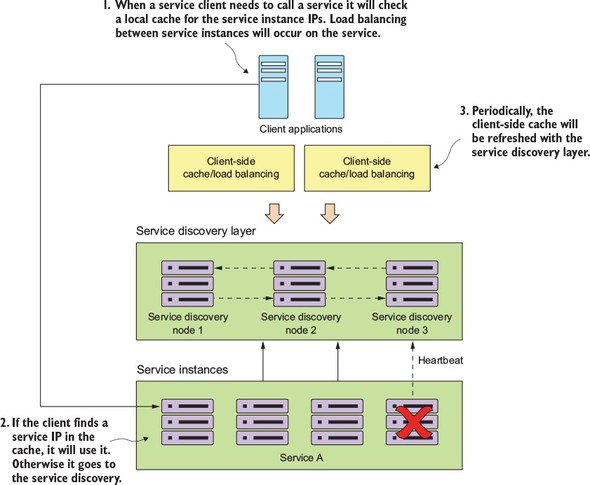

4.2. On service discovery in the cloud

4.2.1. The architecture of service discovery

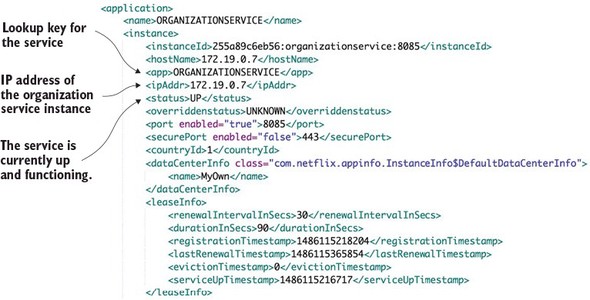

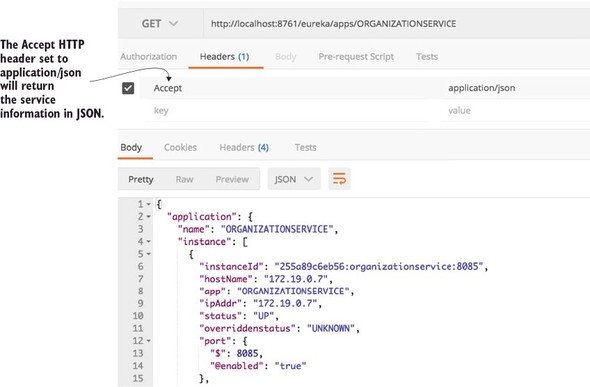

4.2.2. Service discovery in action using Spring and Netflix Eureka

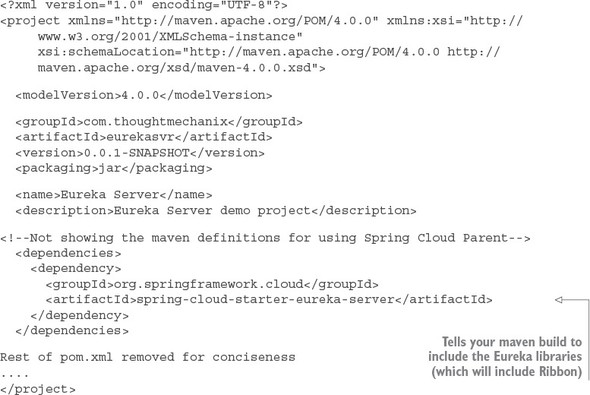

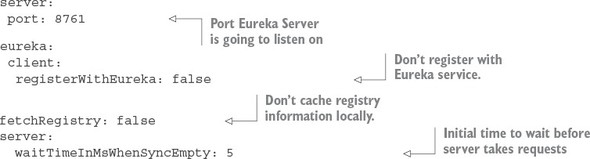

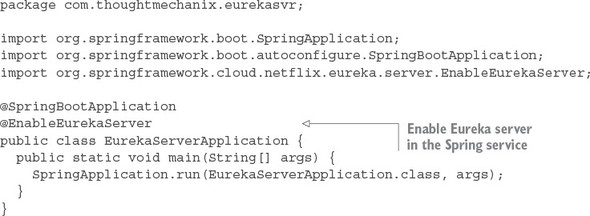

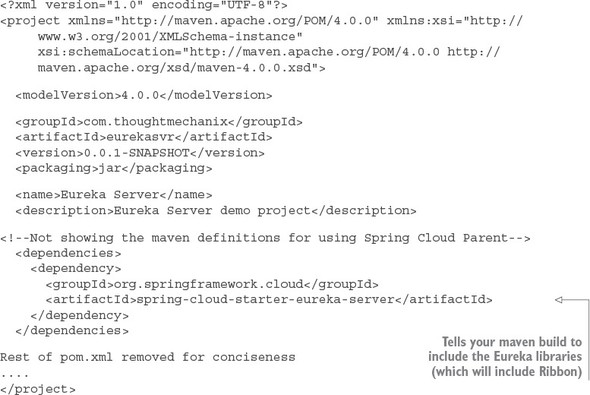

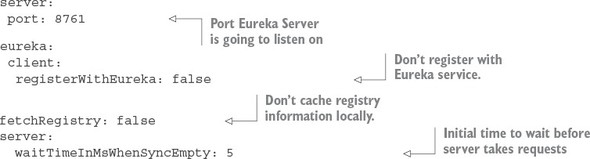

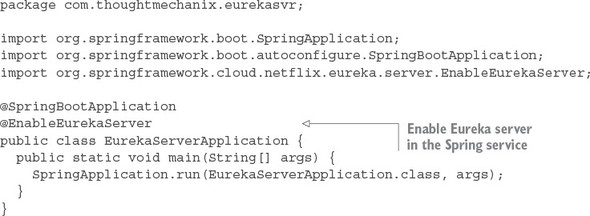

4.3. Building your Spring Eureka Service

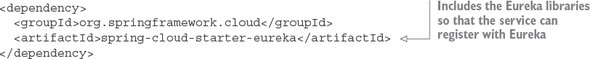

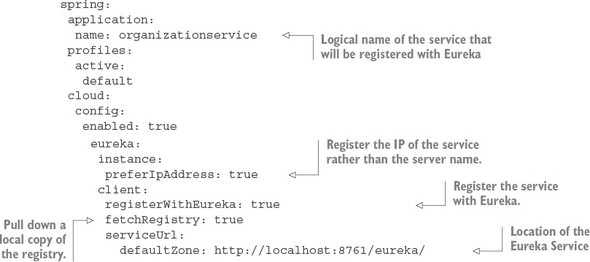

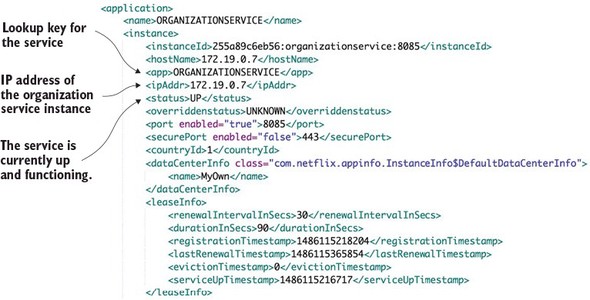

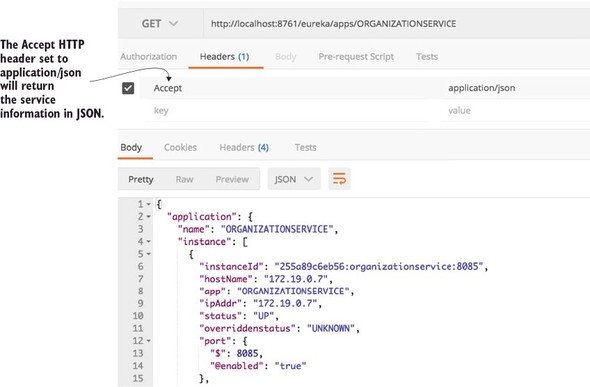

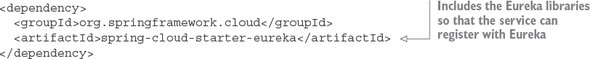

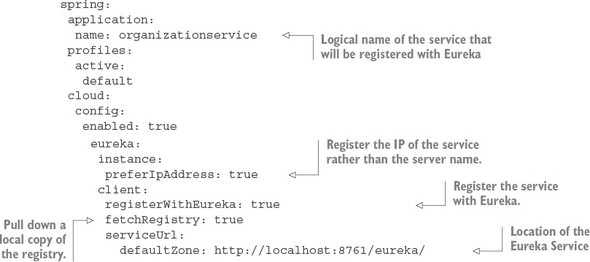

4.4. Registering services with Spring Eureka

4.5. Using service discovery to look up a service

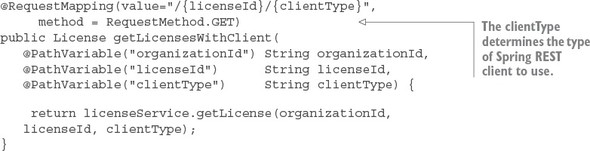

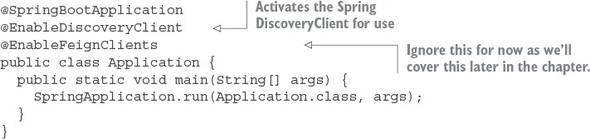

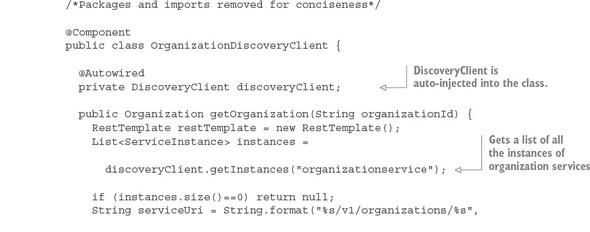

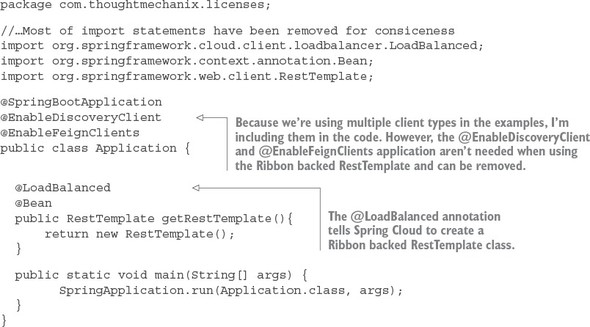

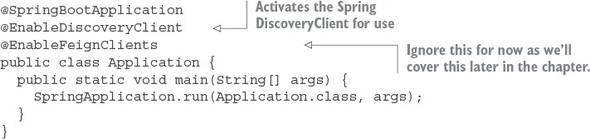

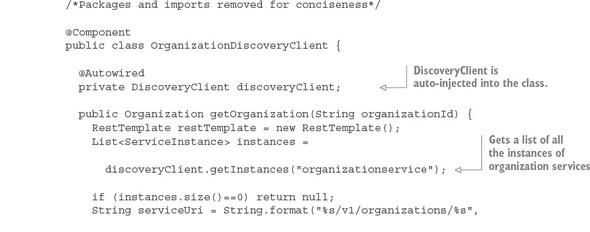

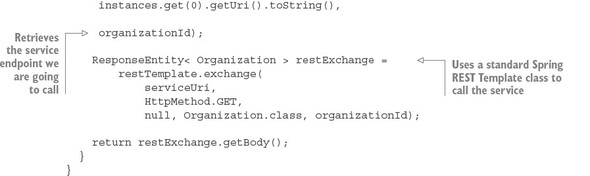

4.5.1. Looking up service instances with Spring DiscoveryClient

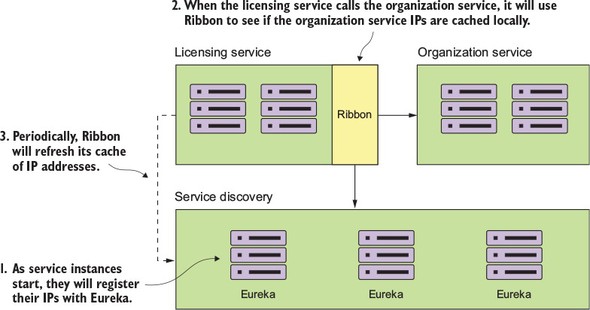

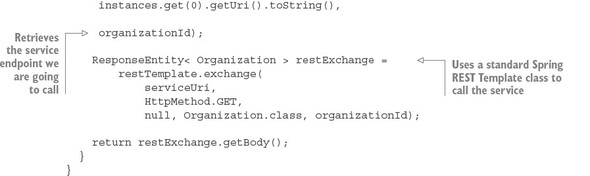

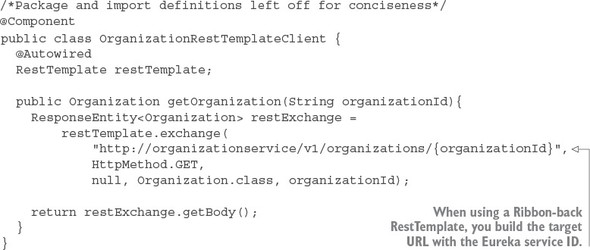

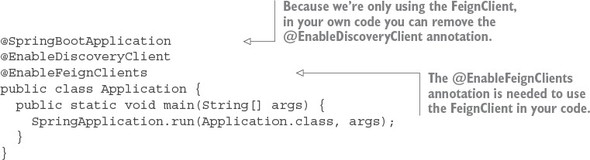

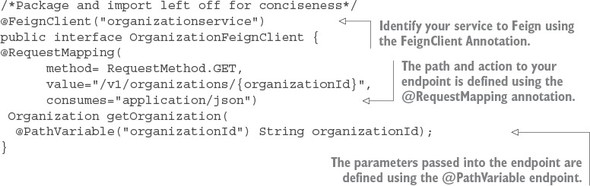

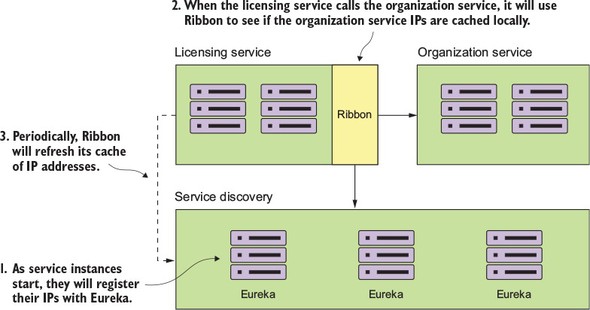

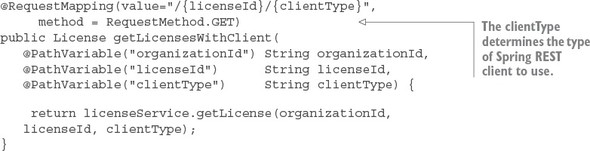

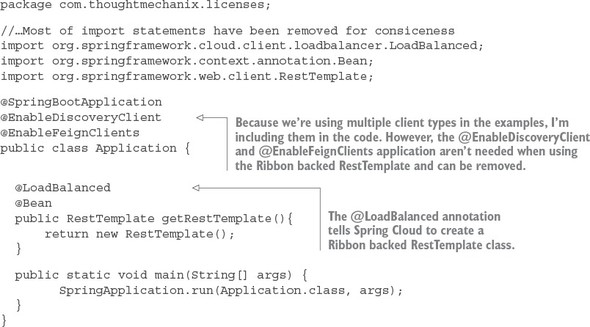

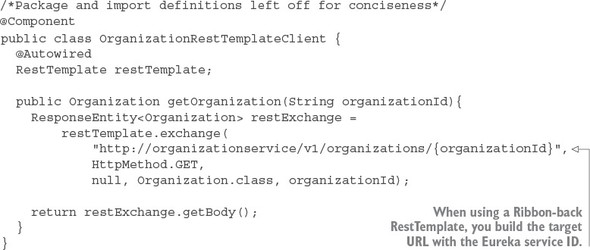

4.5.2. Invoking services with Ribbon-aware Spring RestTemplate

Chapter 5. When bad things happen: client resiliency patterns with Spring Cloud and Netflix Hystrix

5.1. What are client-side resiliency patterns?

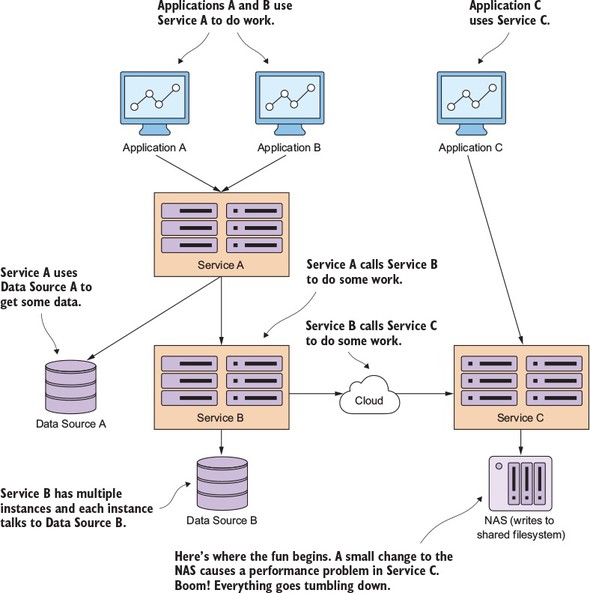

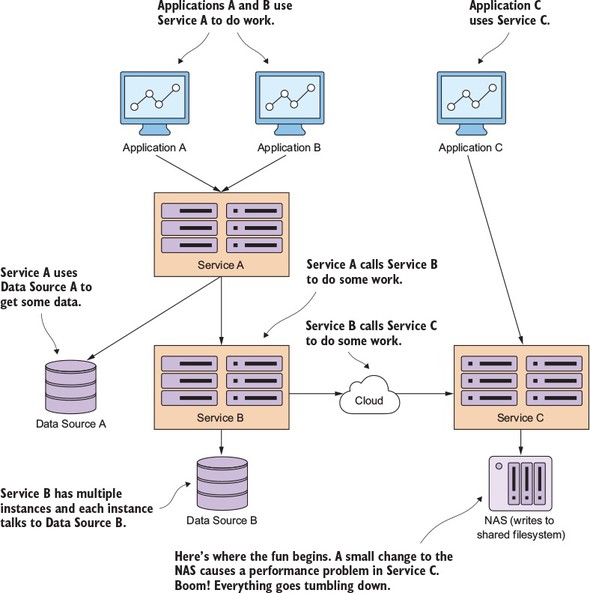

5.2. Why client resiliency matters

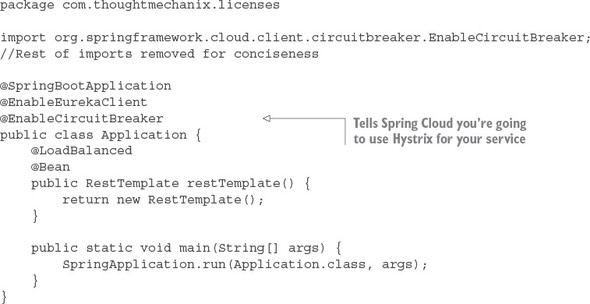

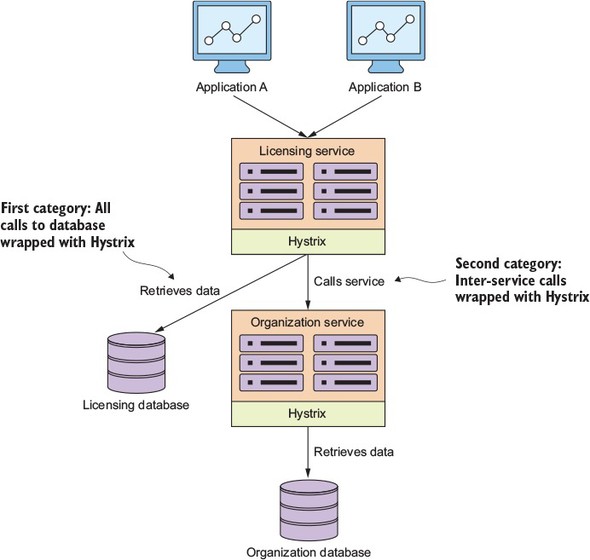

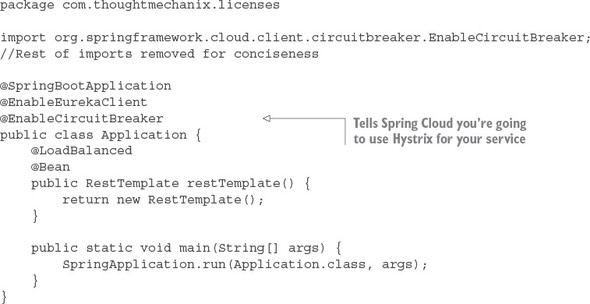

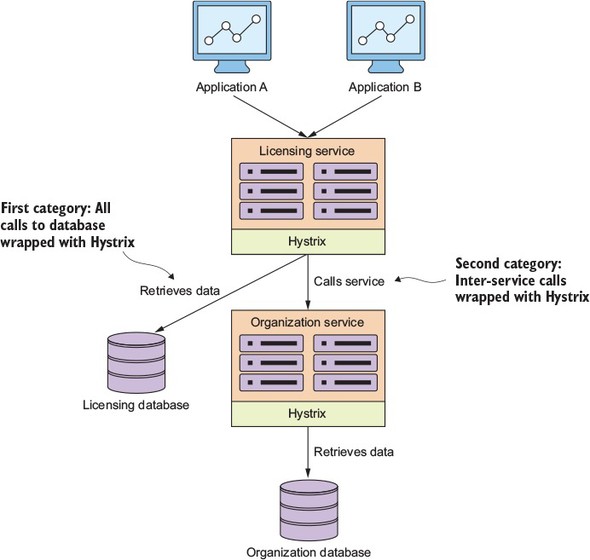

5.4. Setting up the licensing server to use Spring Cloud and Hystrix

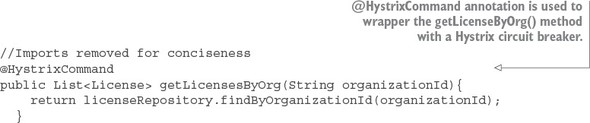

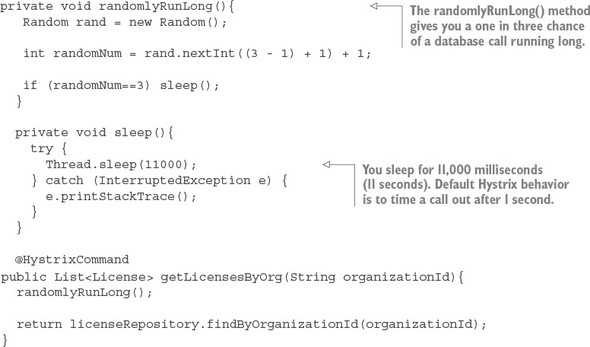

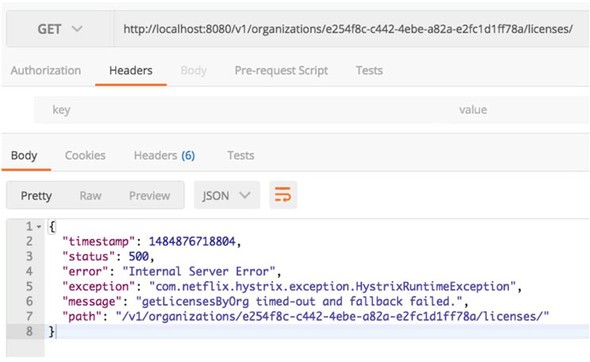

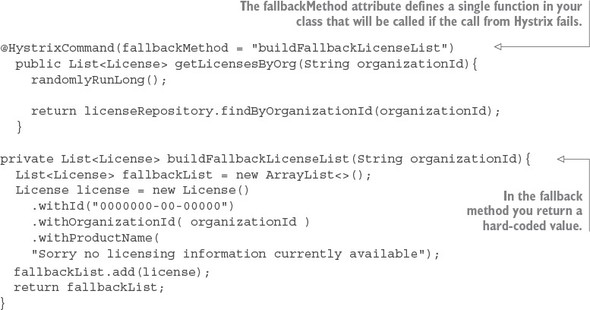

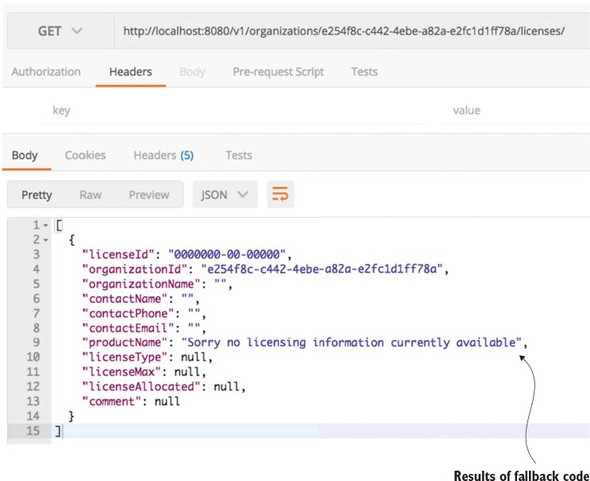

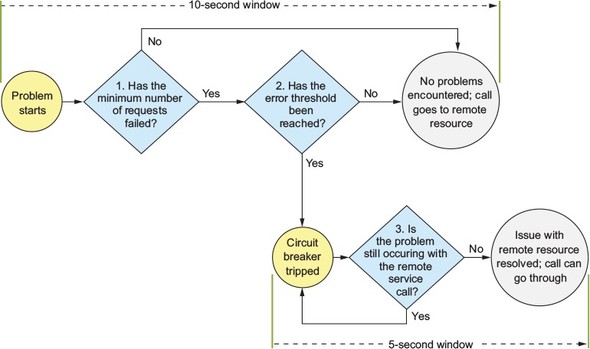

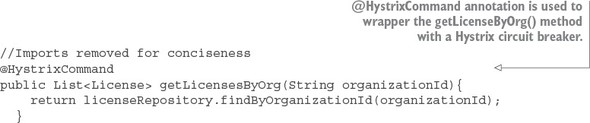

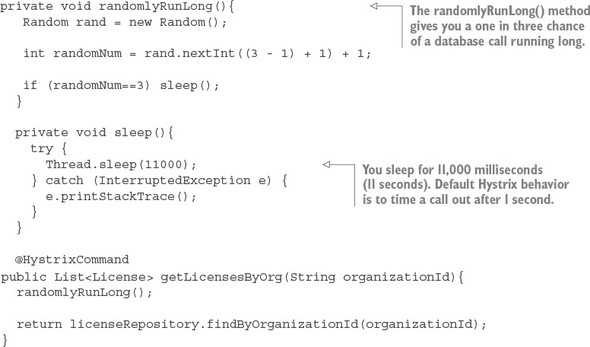

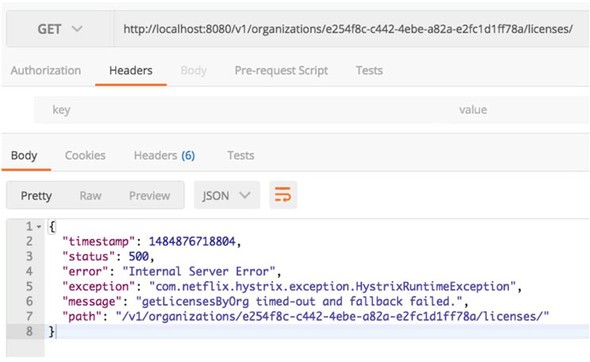

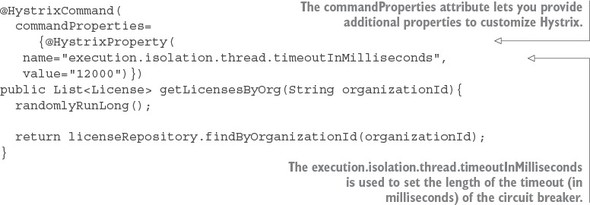

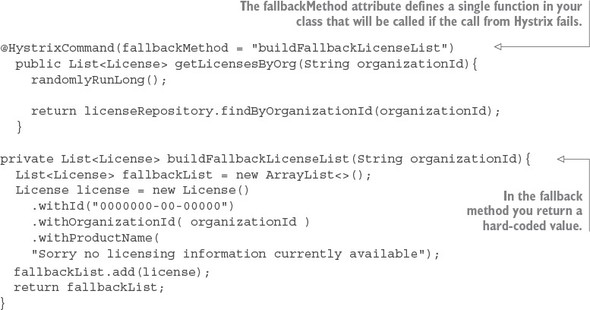

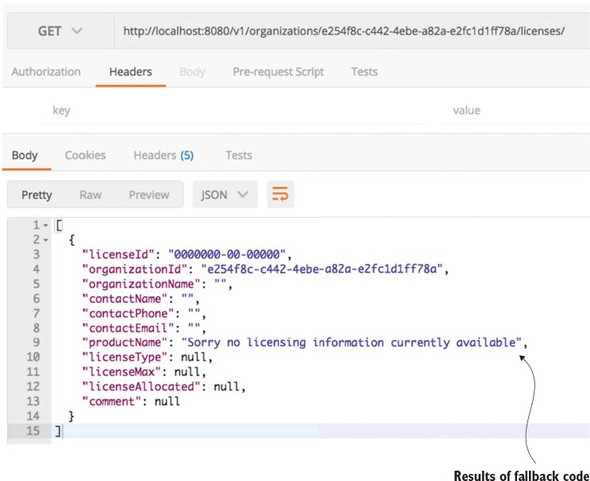

5.5. Implementing a circuit breaker using Hystrix

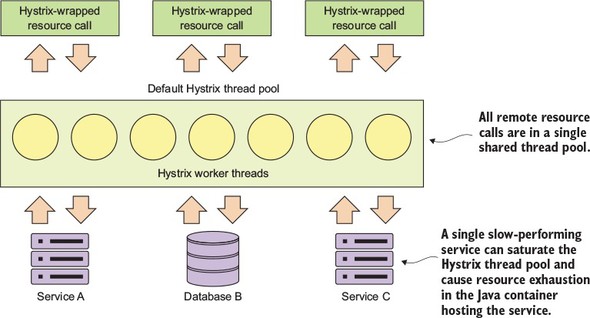

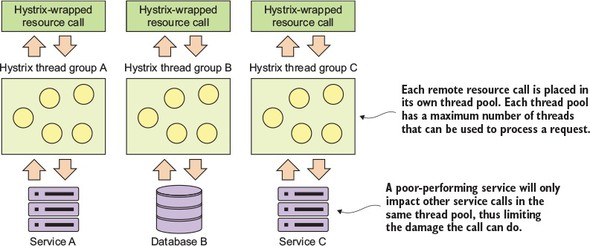

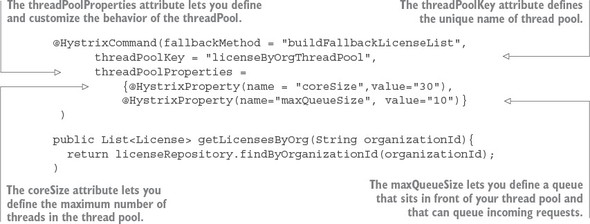

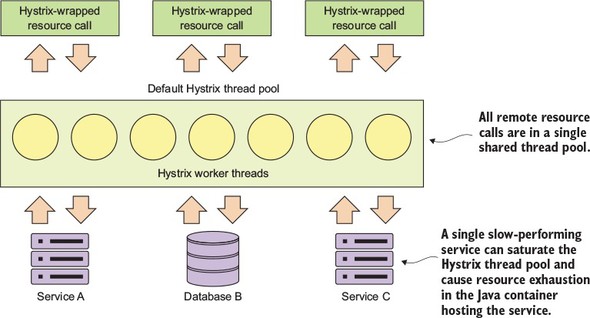

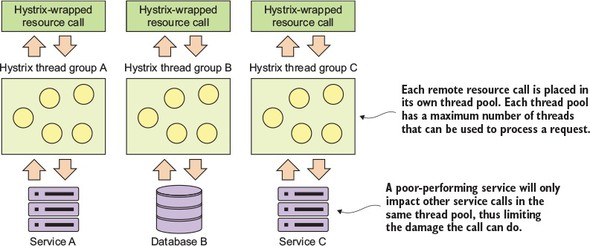

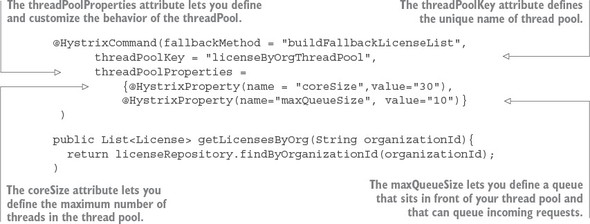

5.7. Implementing the bulkhead pattern

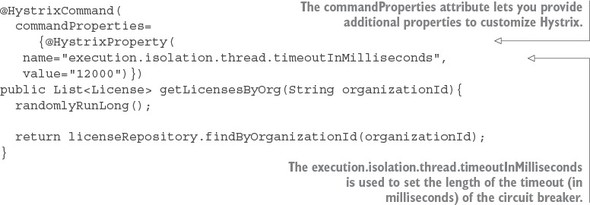

5.8. Getting beyond the basics; fine-tuning Hystrix

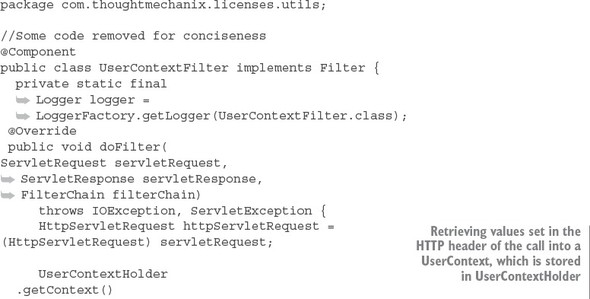

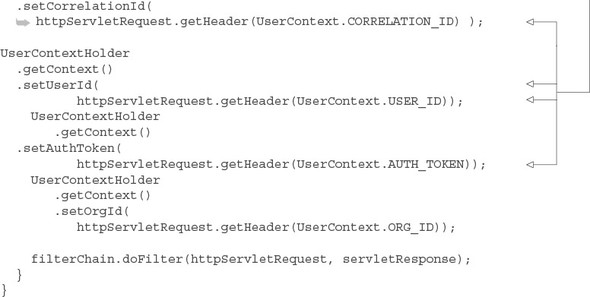

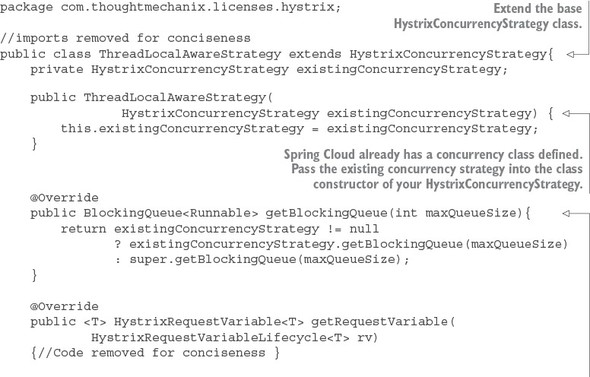

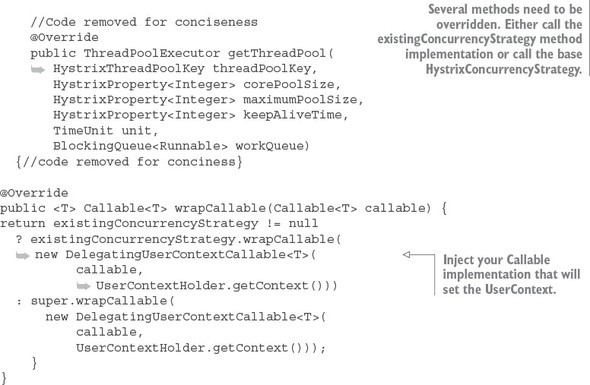

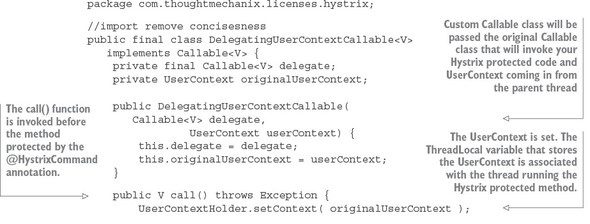

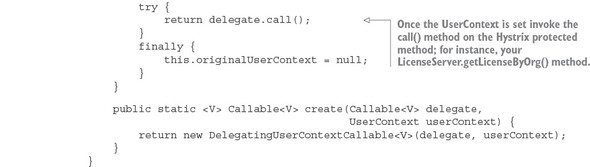

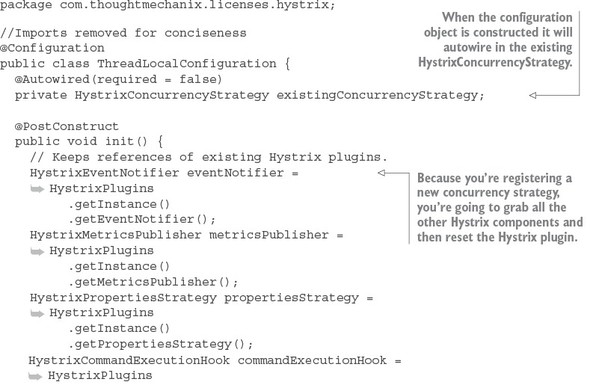

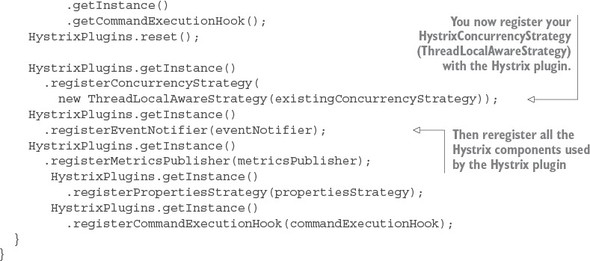

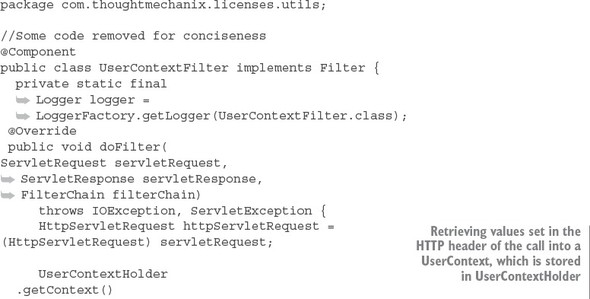

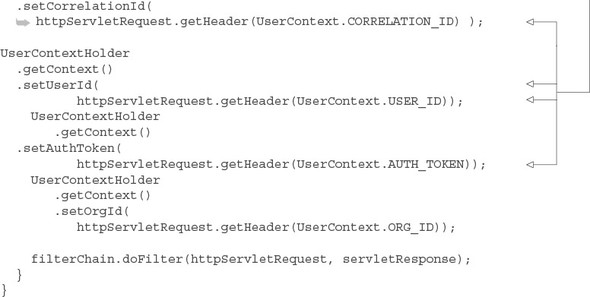

5.9. Thread context and Hystrix

Chapter 6. Service routing with Spring Cloud and Zuul

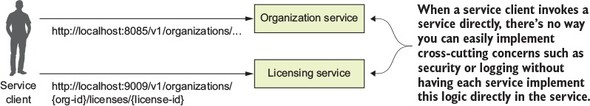

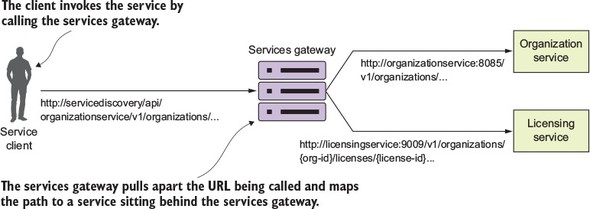

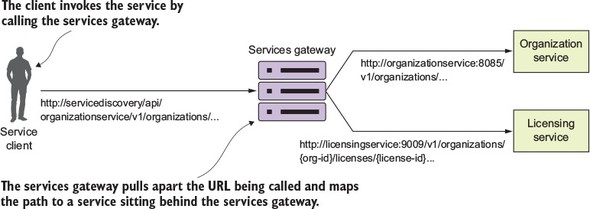

6.1. What is a services gateway?

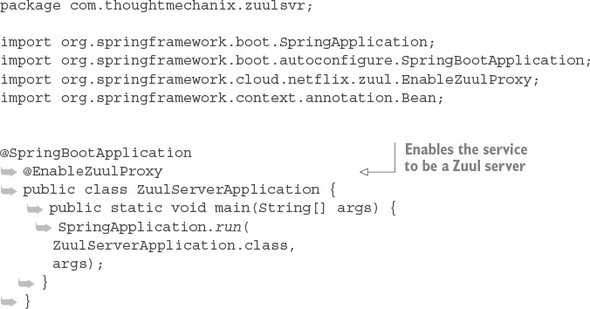

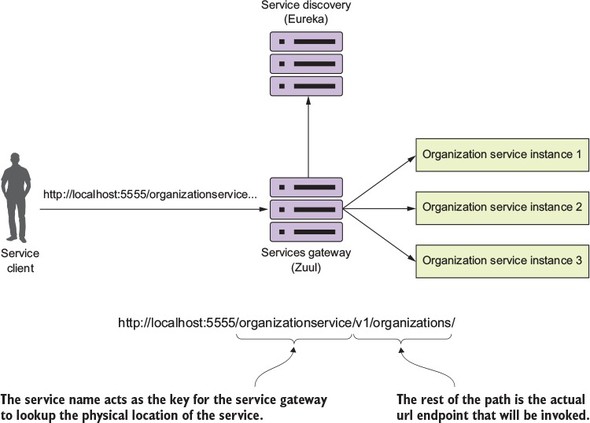

6.2. Introducing Spring Cloud and Netflix Zuul

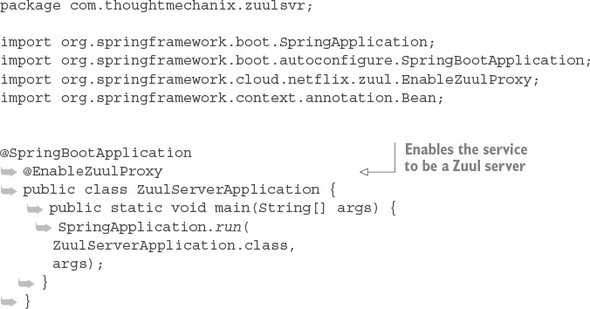

6.2.1. Setting up the Zuul Spring Boot project

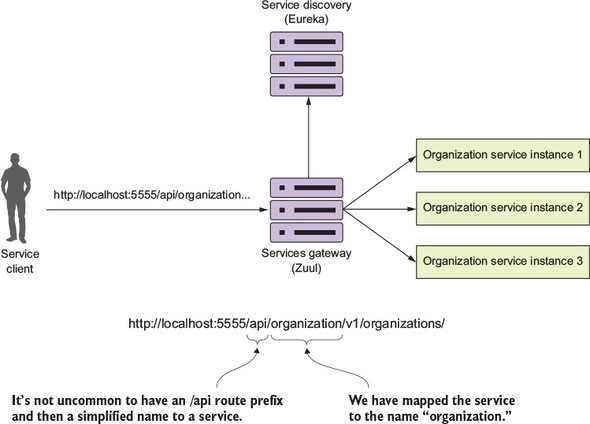

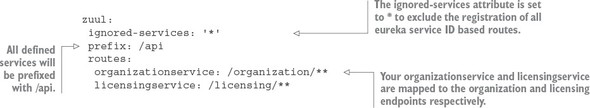

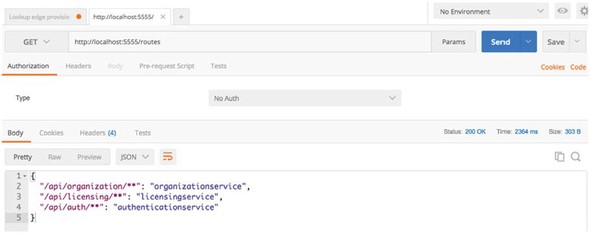

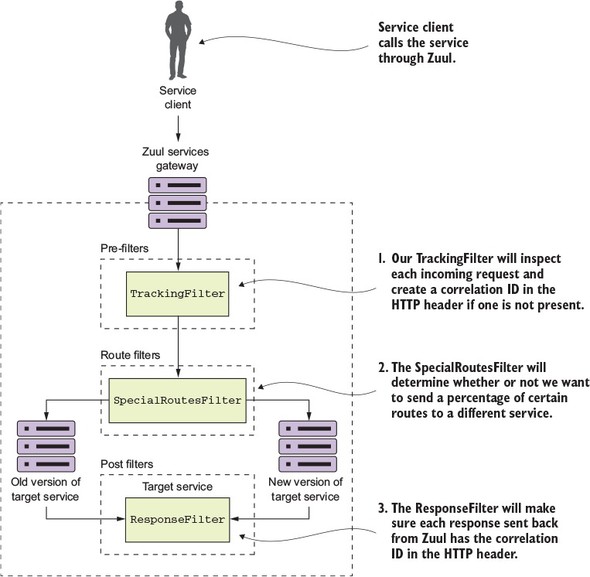

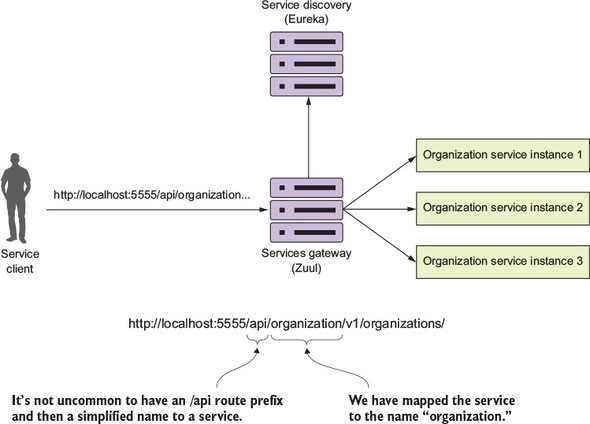

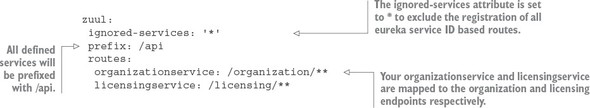

6.3. Configuring routes in Zuul

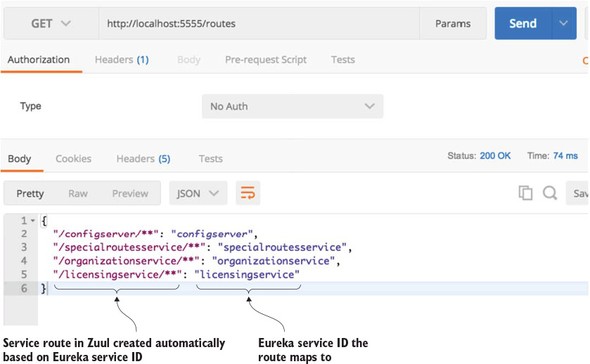

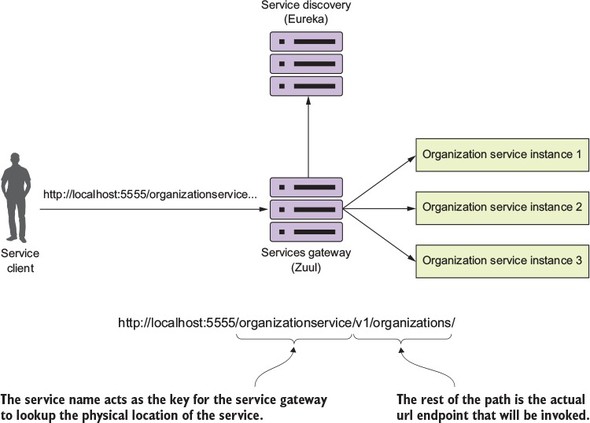

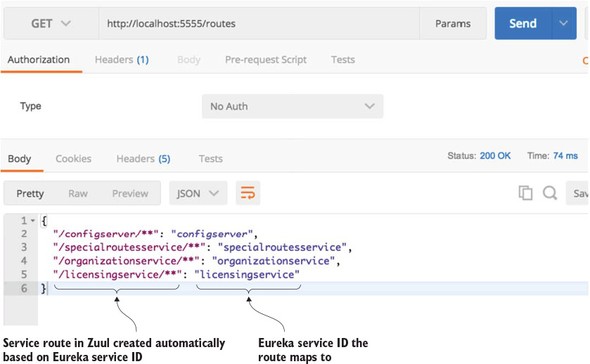

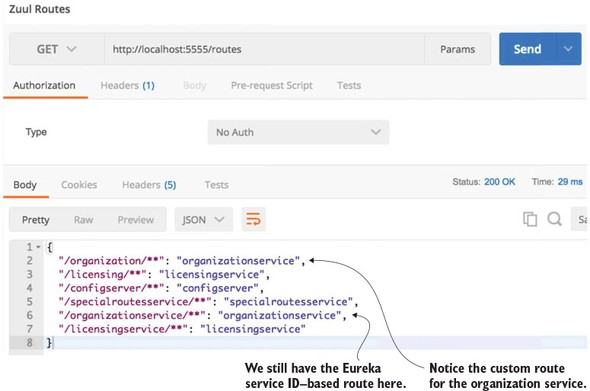

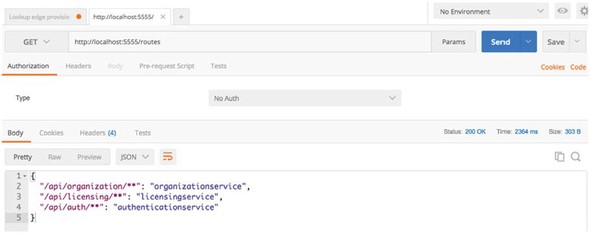

6.3.1. Automated mapping routes via service discovery

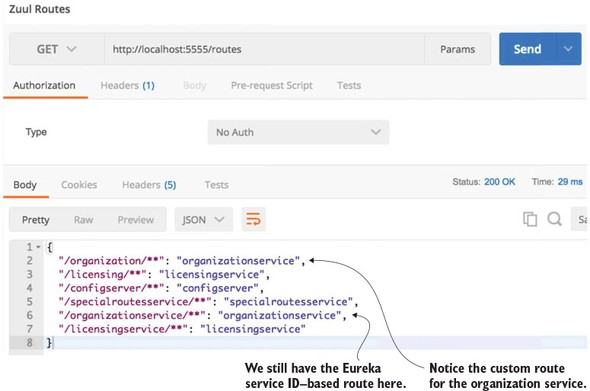

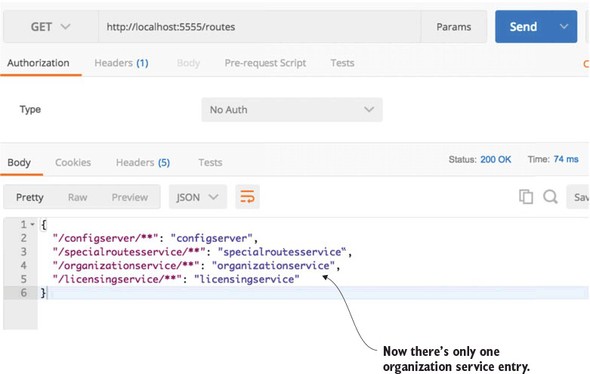

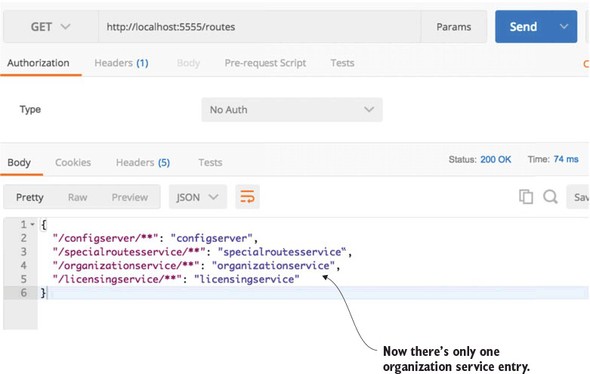

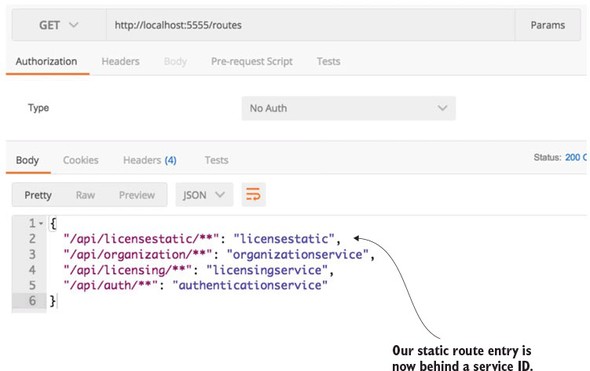

6.3.2. Mapping routes manually using service discovery

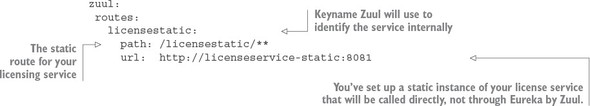

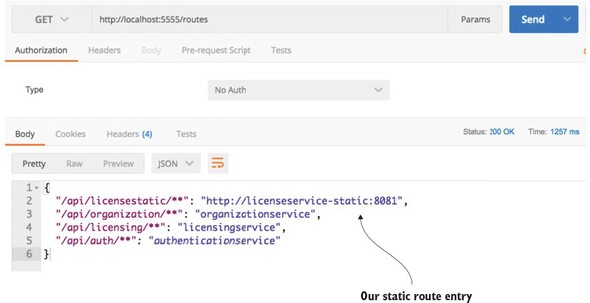

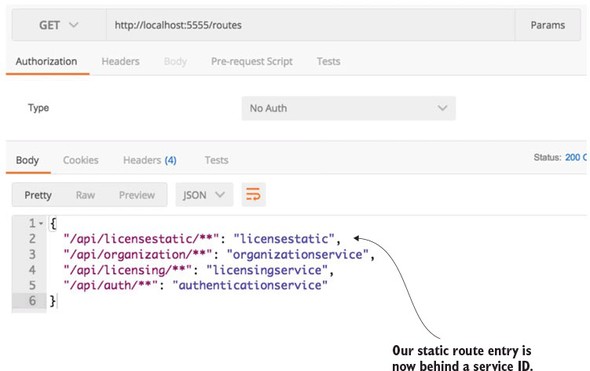

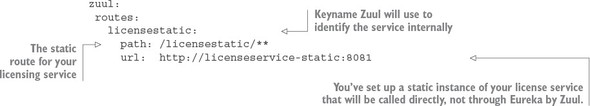

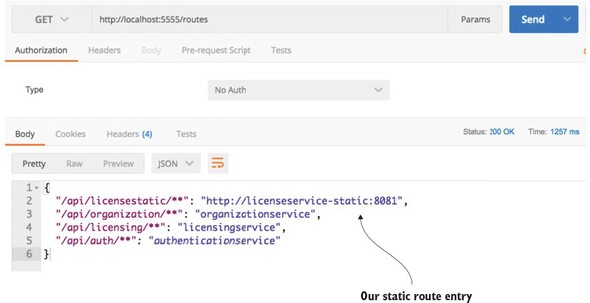

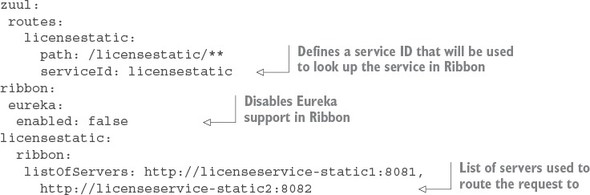

6.3.3. Manual mapping of routes using static URLs

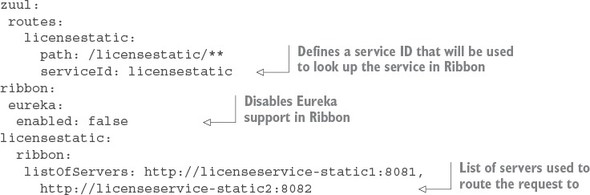

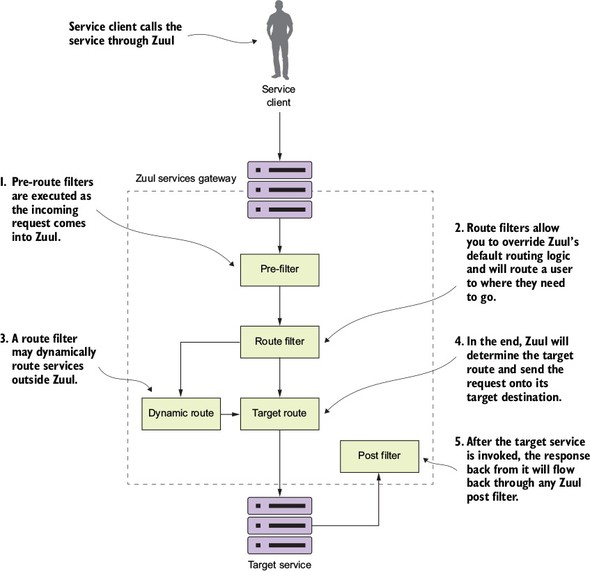

6.4. The real power of Zuul: filters

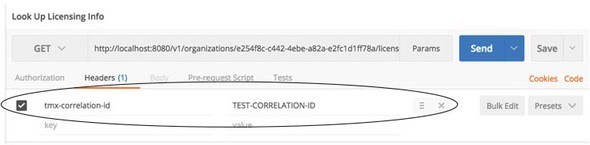

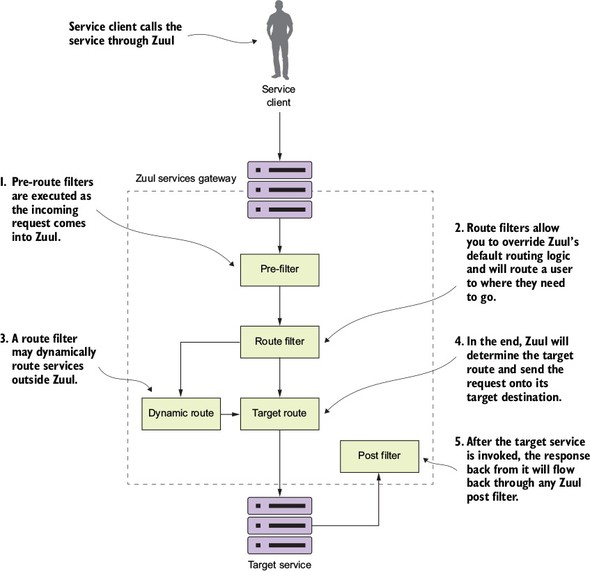

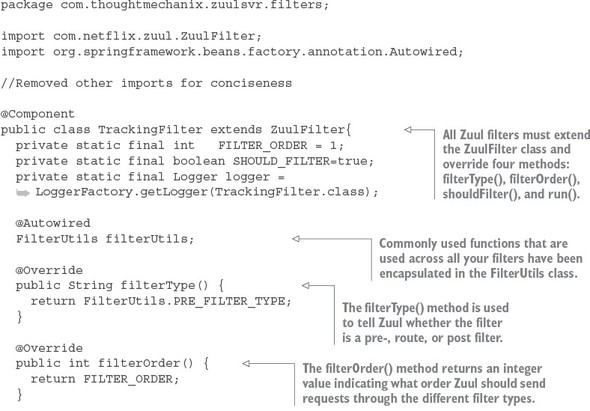

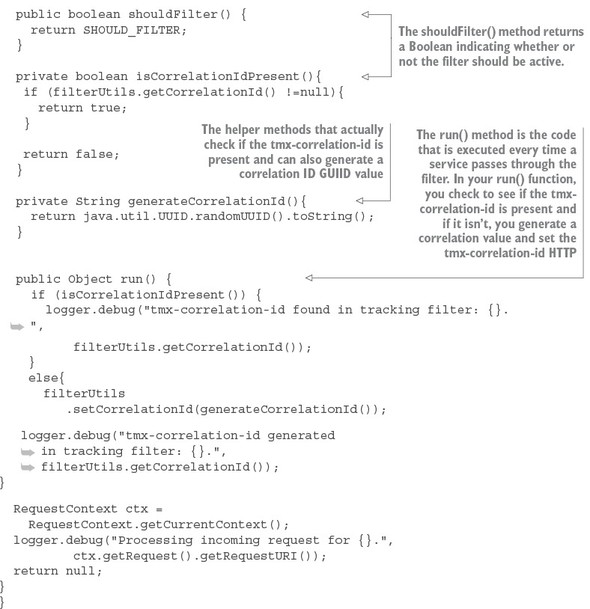

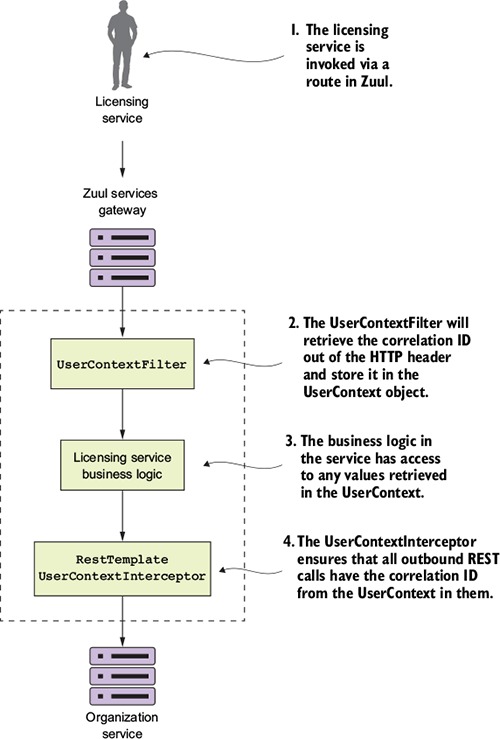

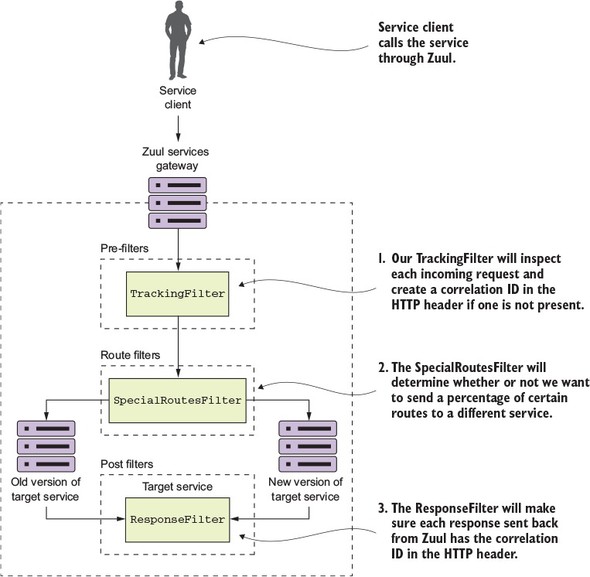

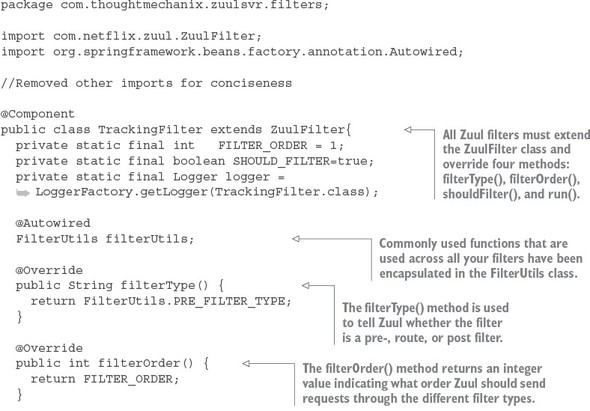

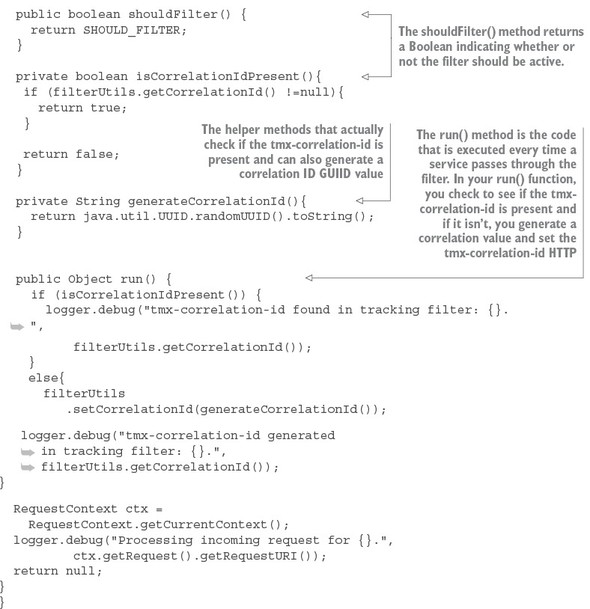

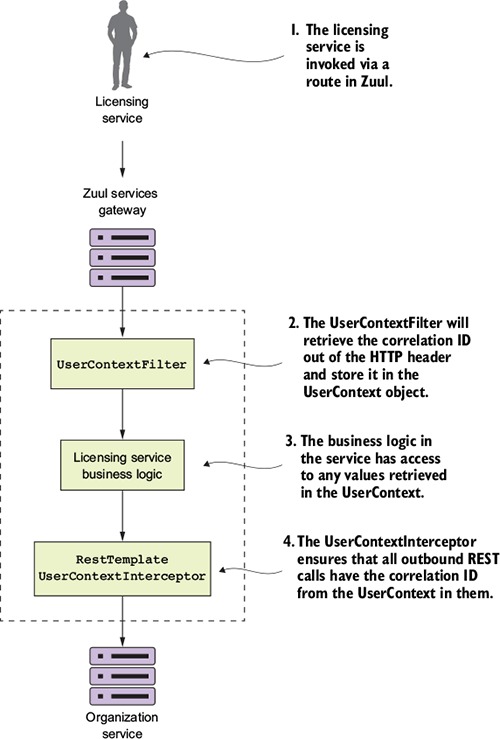

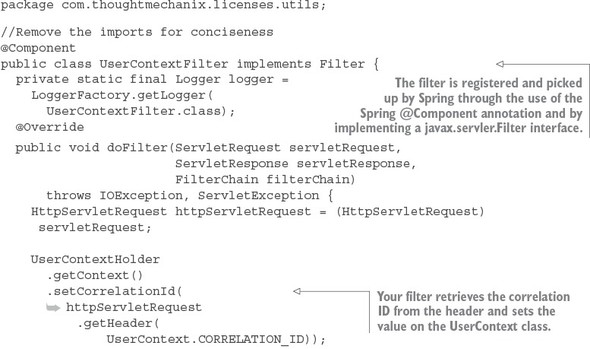

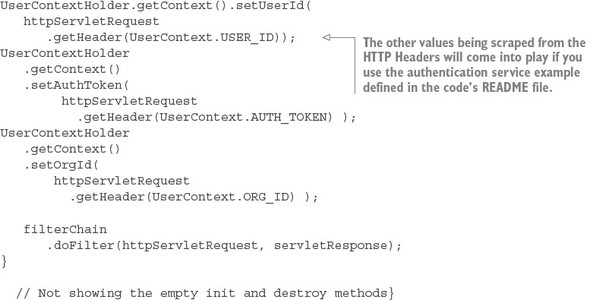

6.5. Building your first Zuul pre-filter generating correlation IDs

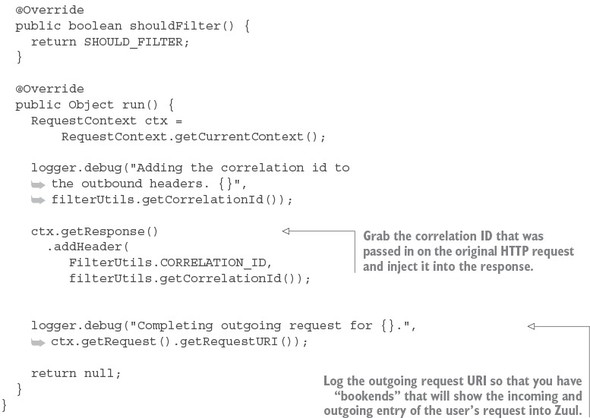

6.6. Building a post filter receiving correlation IDs

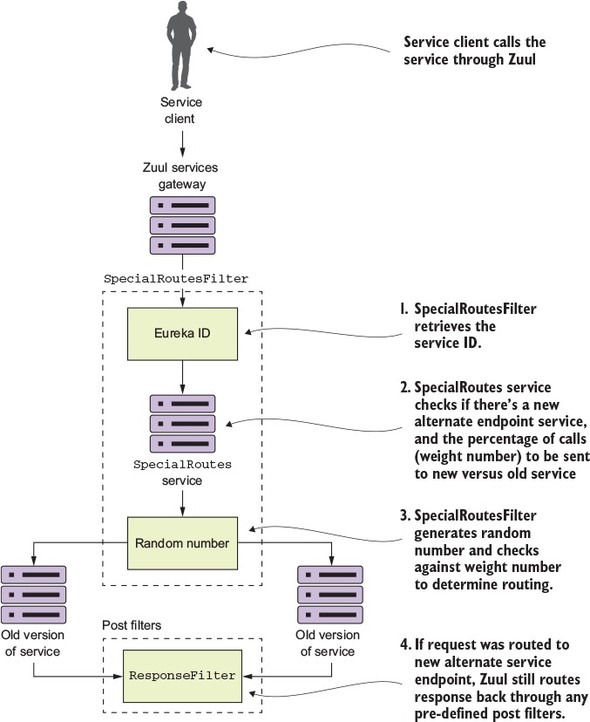

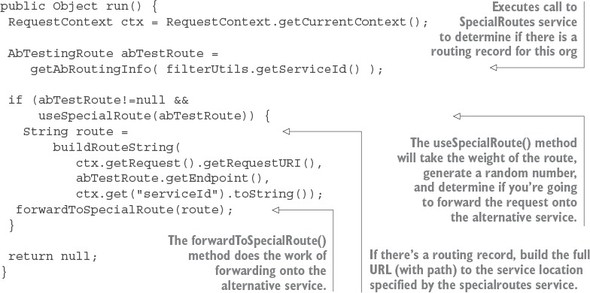

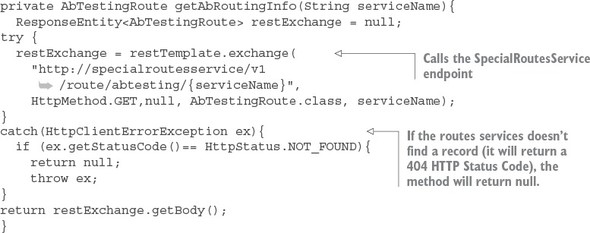

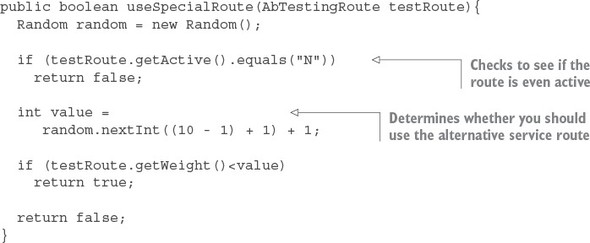

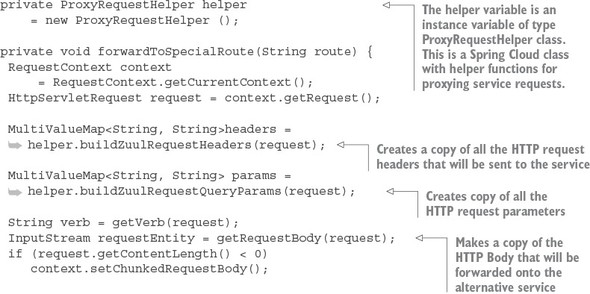

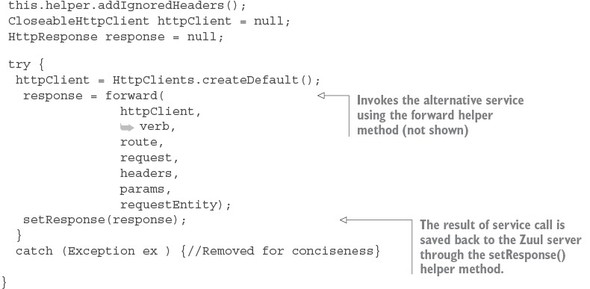

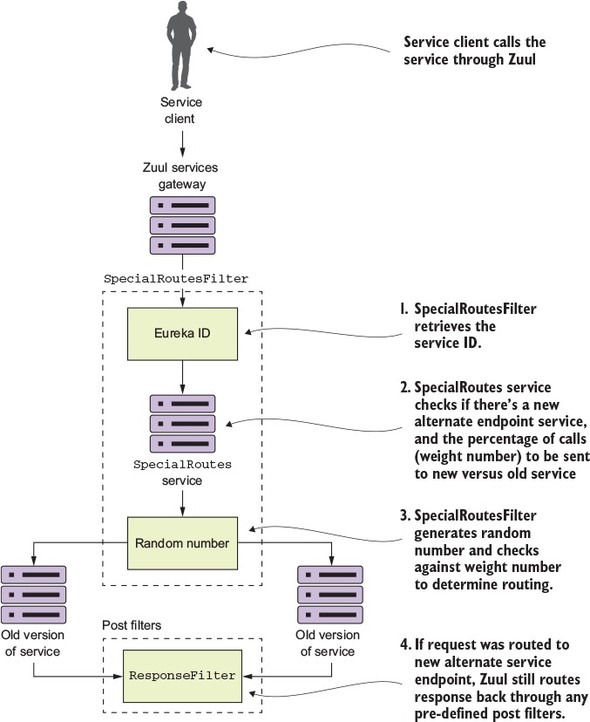

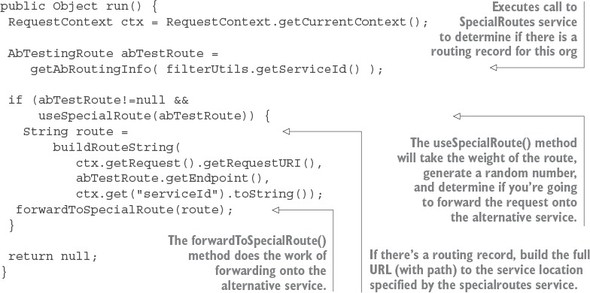

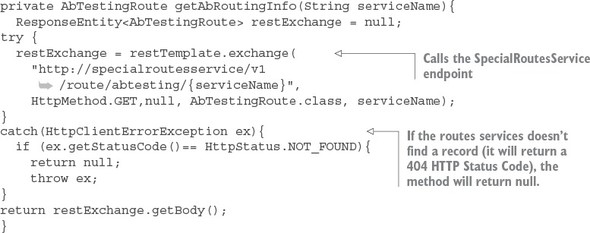

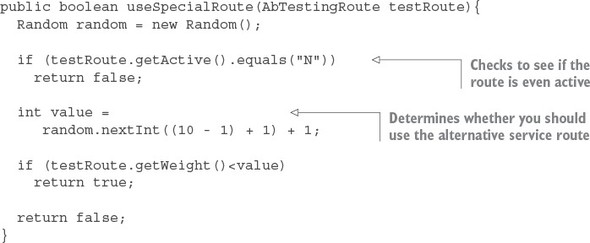

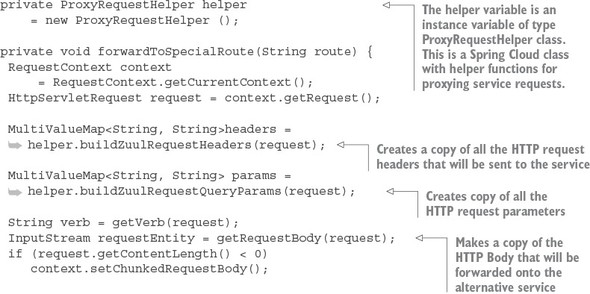

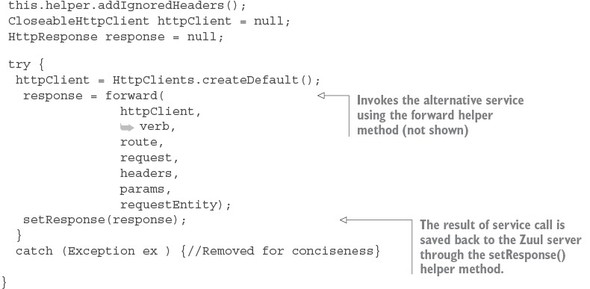

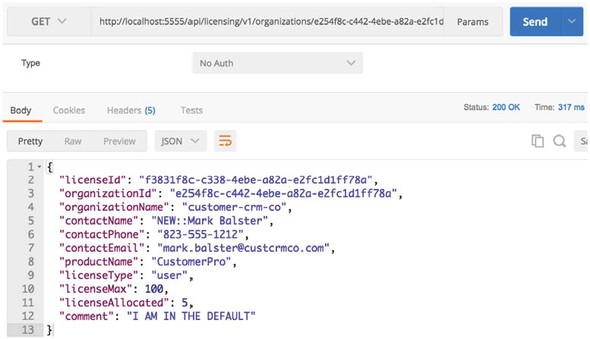

6.7. Building a dynamic route filter

6.7.1. Building the skeleton of the routing filter

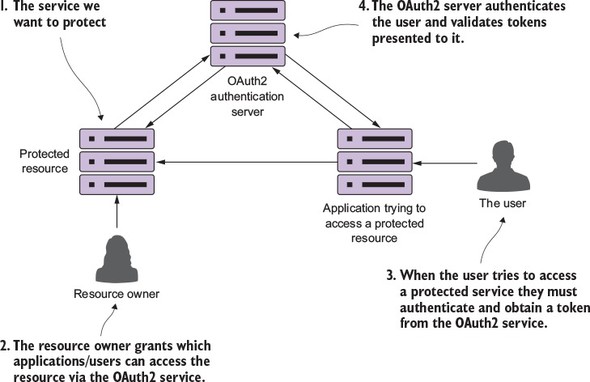

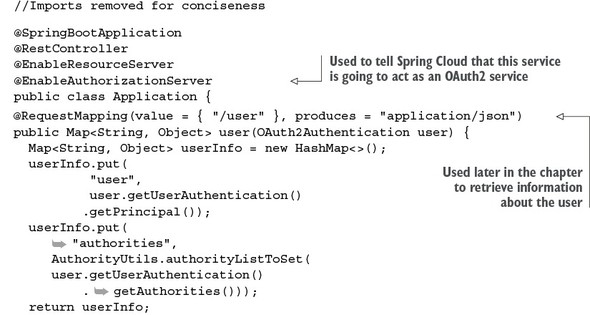

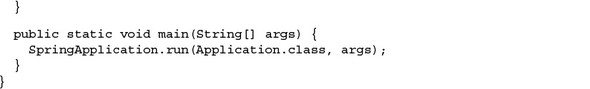

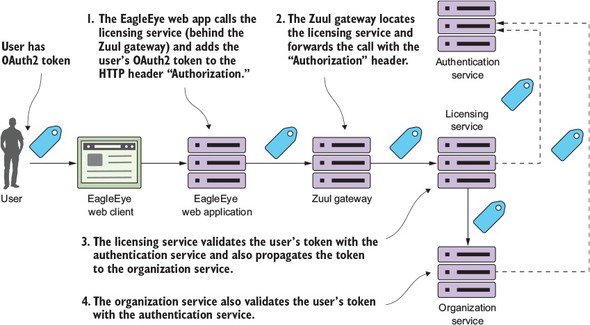

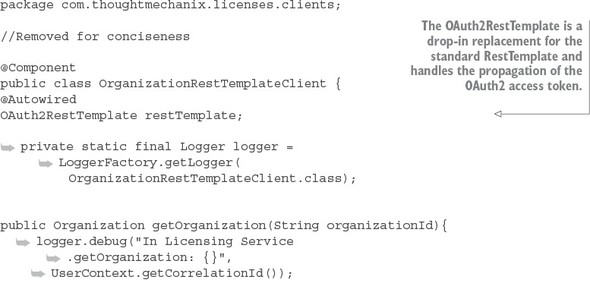

Chapter 7. Securing your microservices

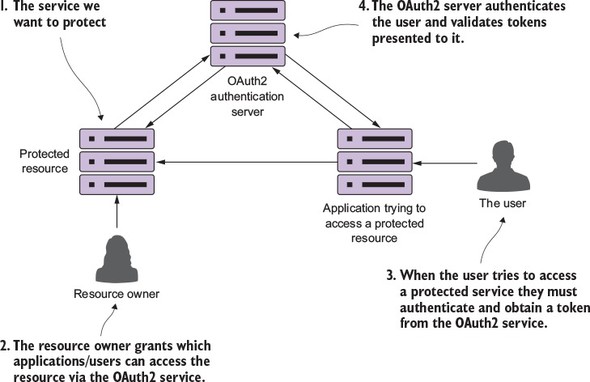

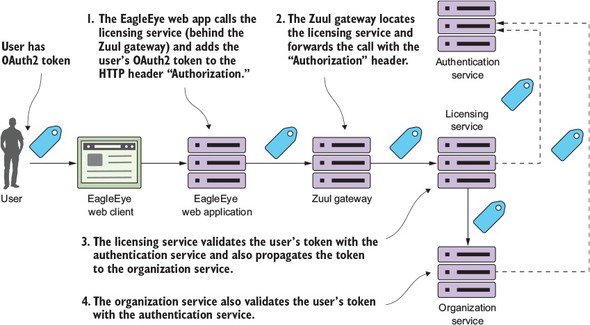

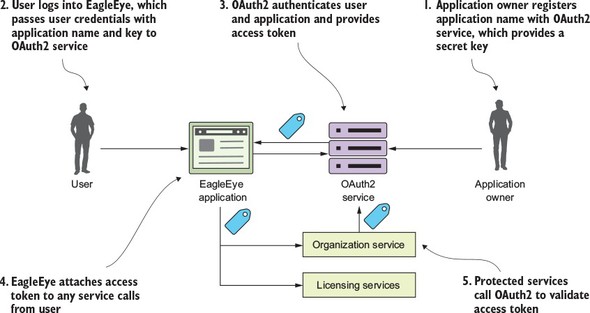

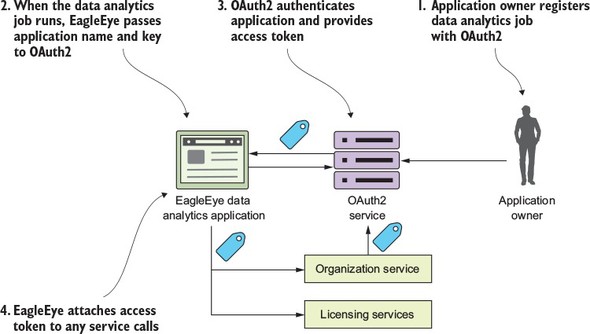

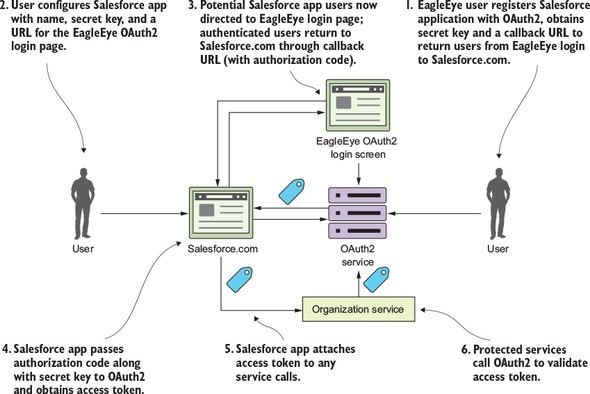

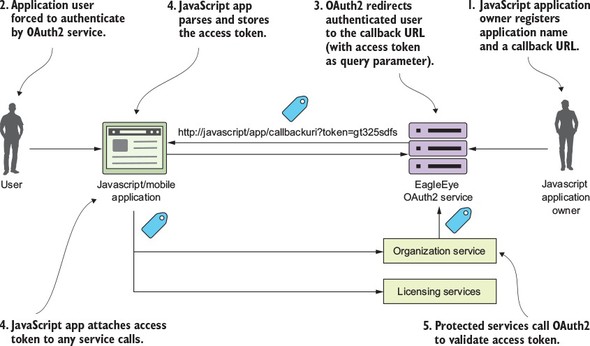

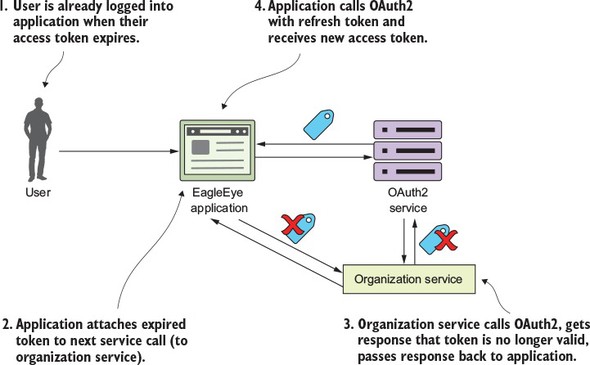

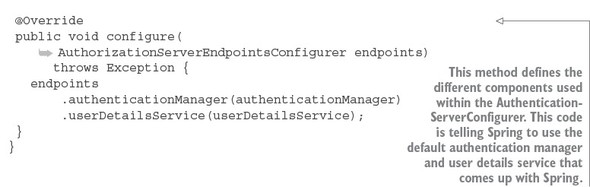

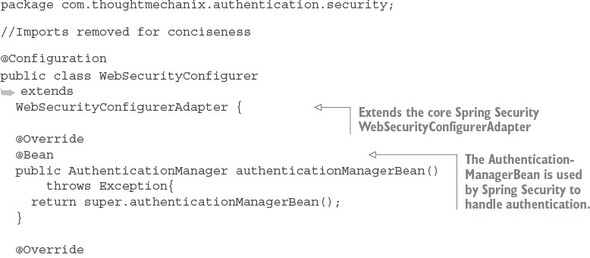

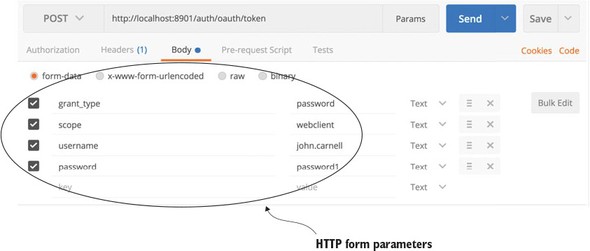

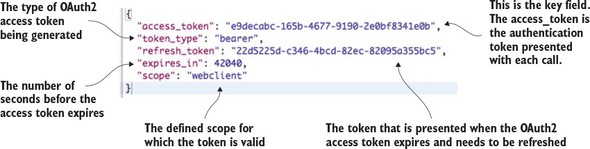

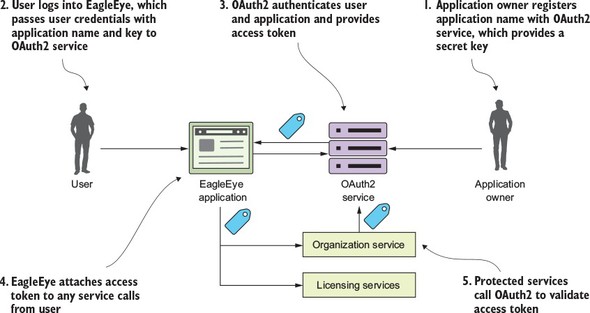

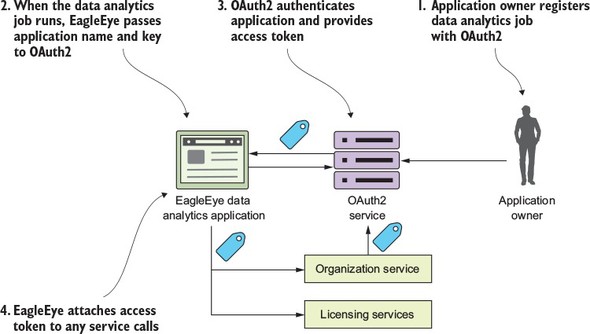

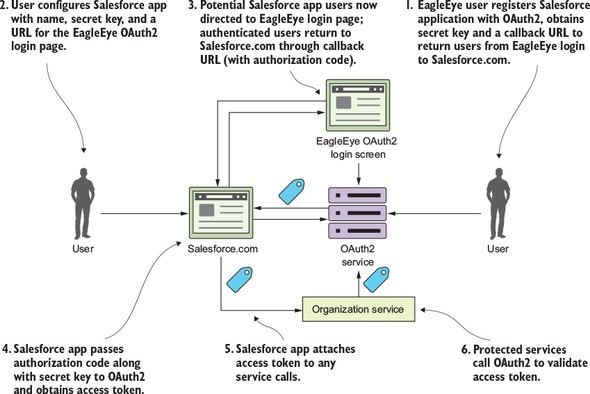

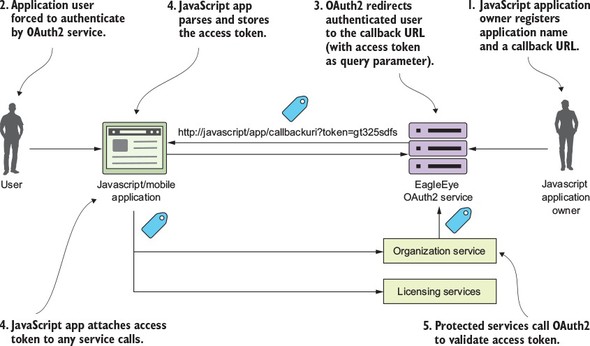

7.2. Starting small: using Spring and OAuth2 to protect a single endpoint

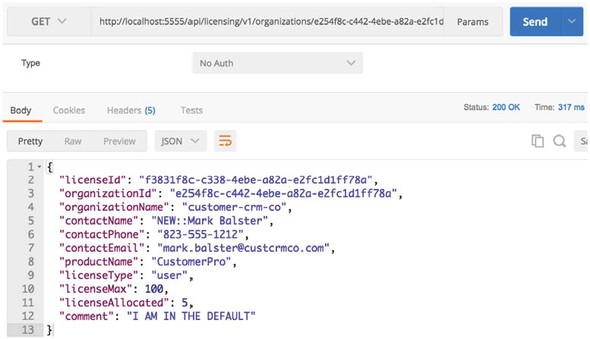

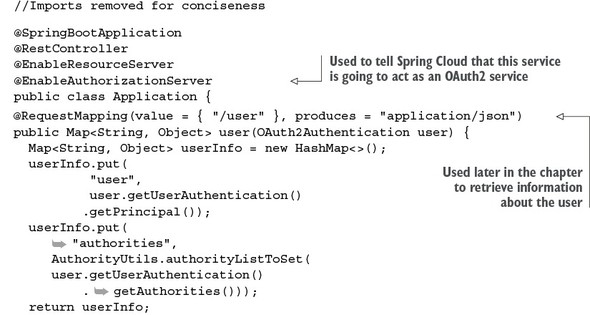

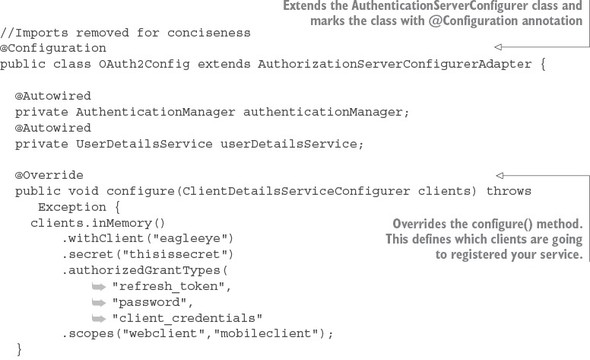

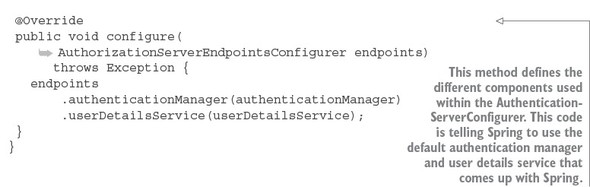

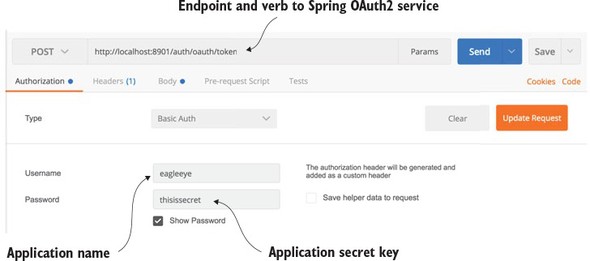

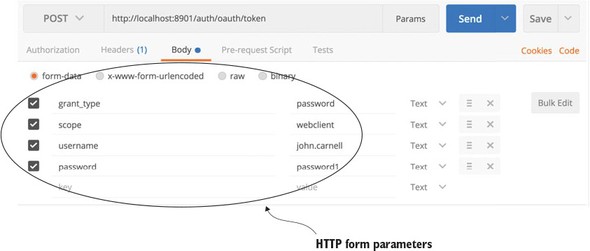

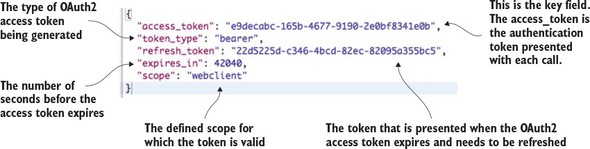

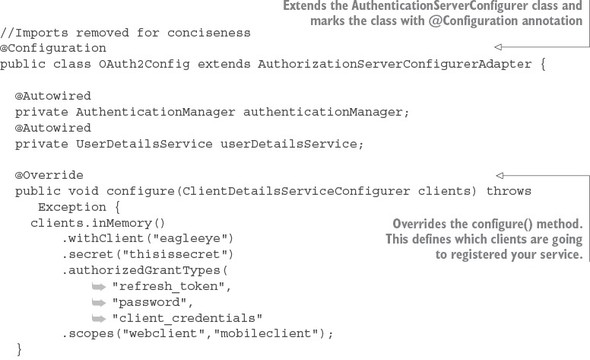

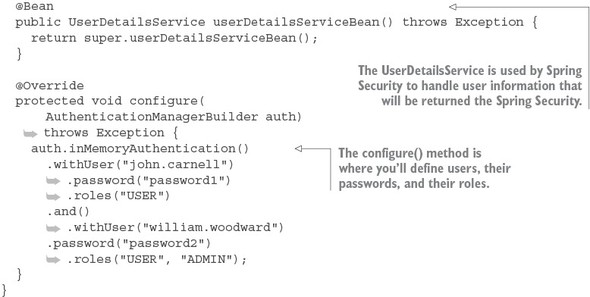

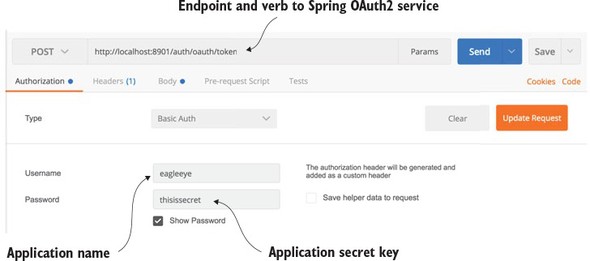

7.2.1. Setting up the EagleEye OAuth2 authentication service

7.2.2. Registering client applications with the OAuth2 service

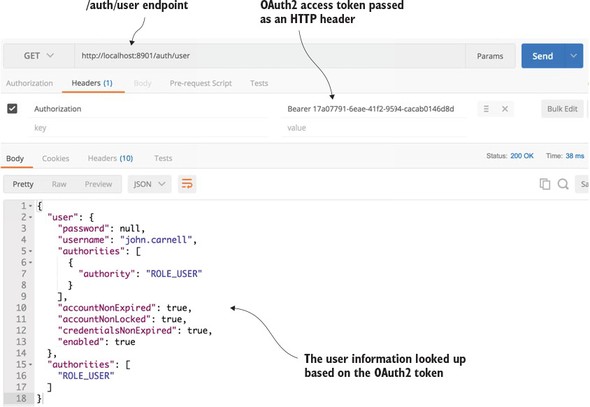

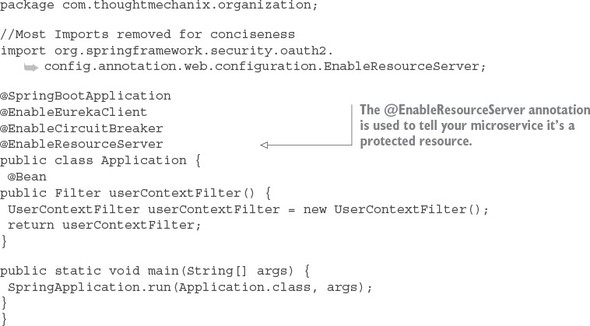

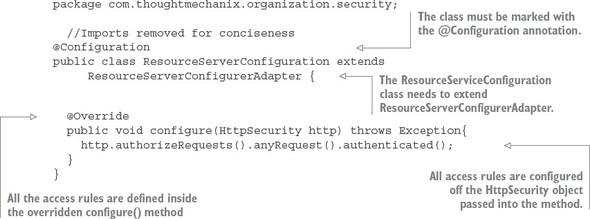

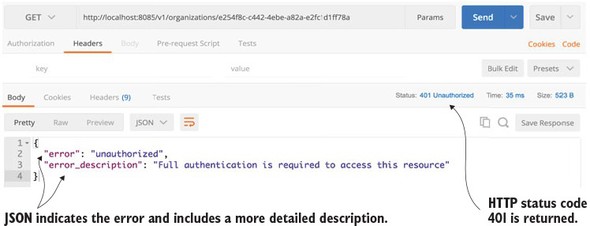

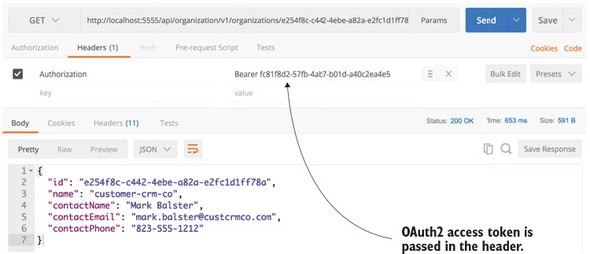

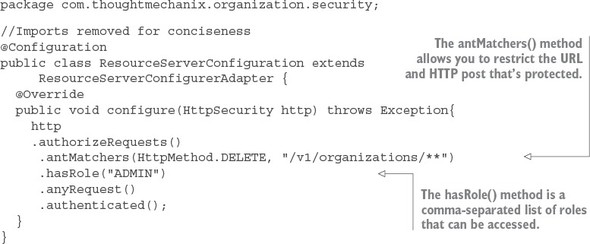

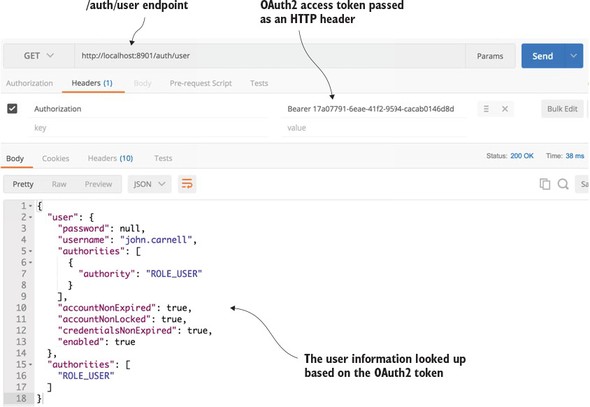

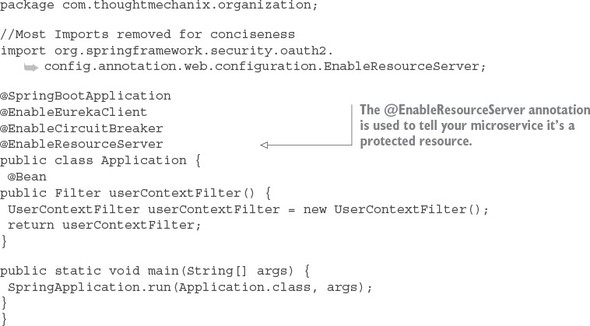

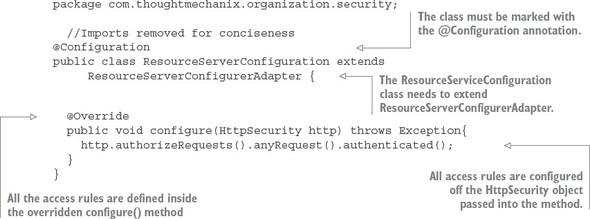

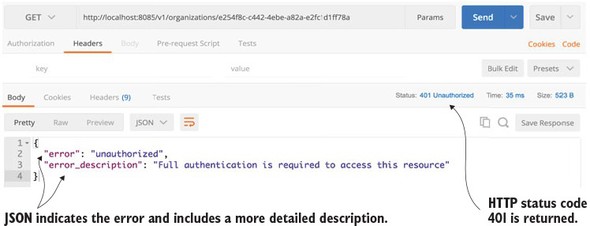

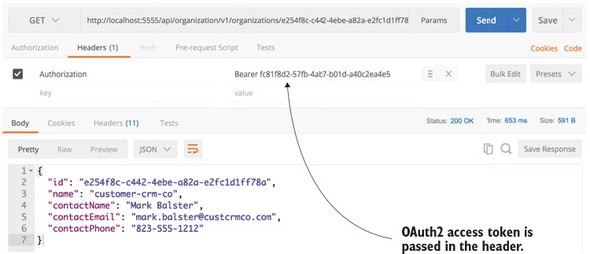

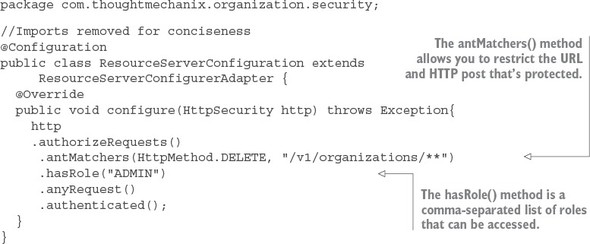

7.3. Protecting the organization service using OAuth2

7.3.1. Adding the Spring Security and OAuth2 jars to the individual services

7.3.2. Configuring the service to point to your OAuth2 authentication service

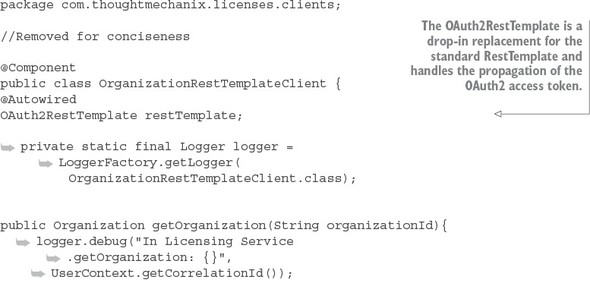

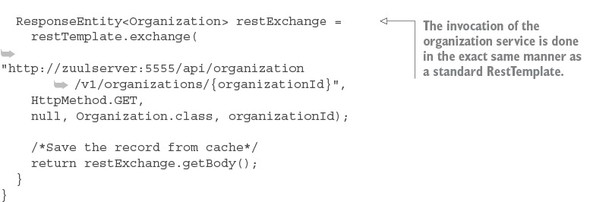

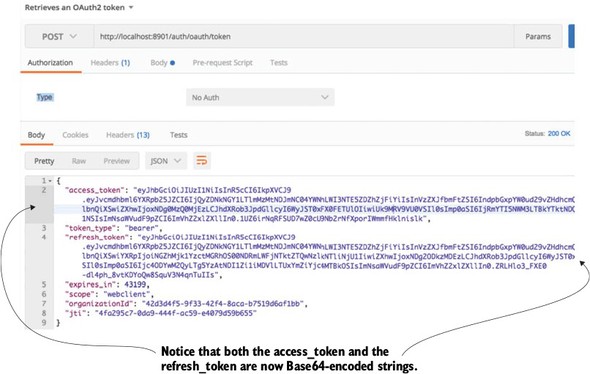

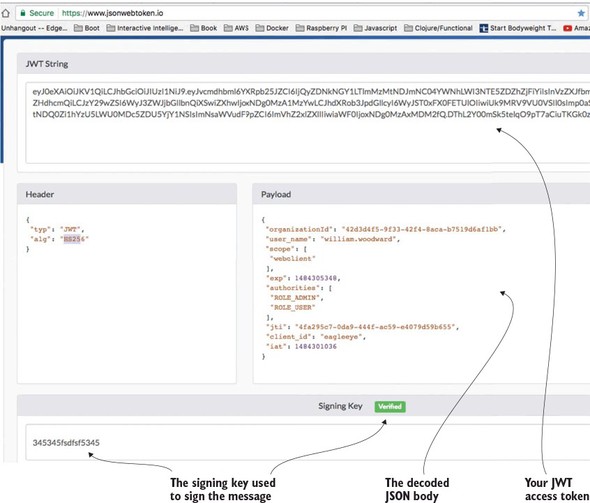

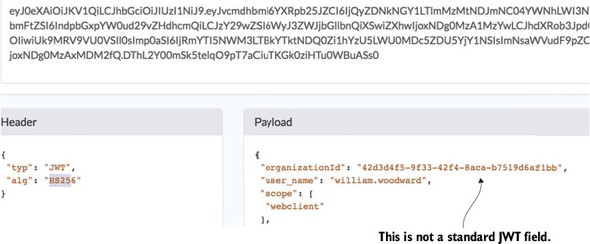

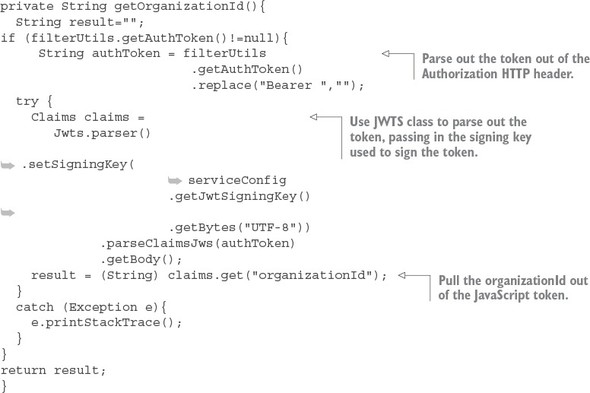

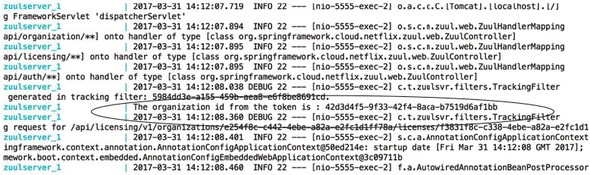

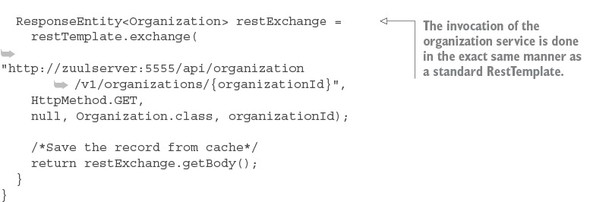

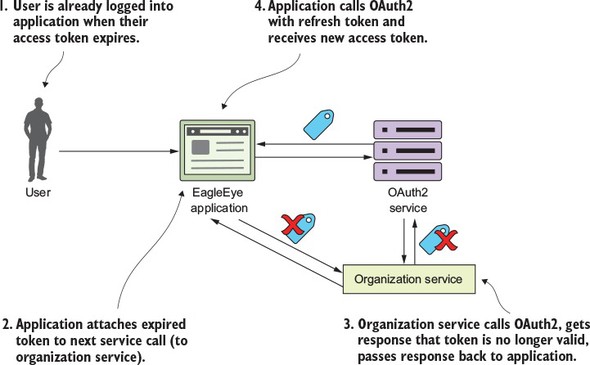

7.4. JavaScript Web Tokens and OAuth2

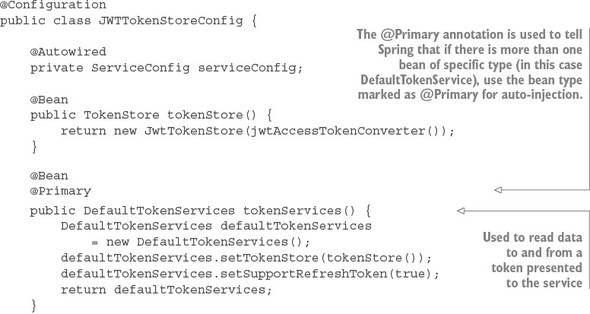

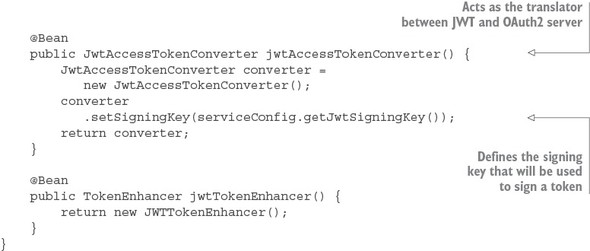

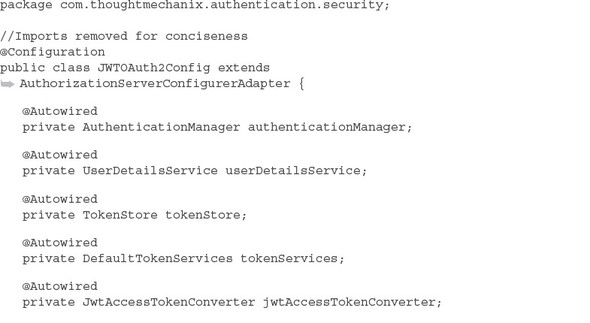

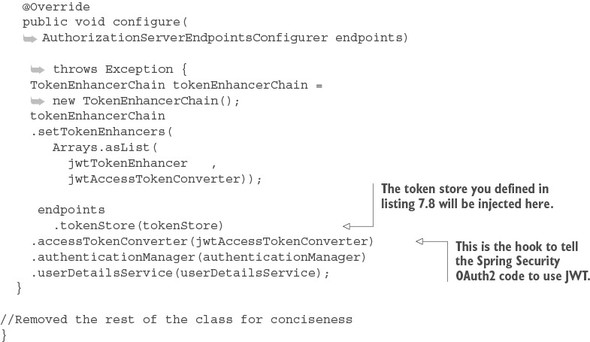

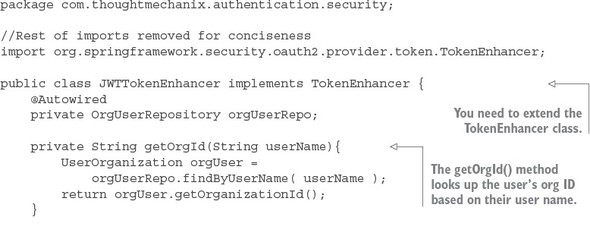

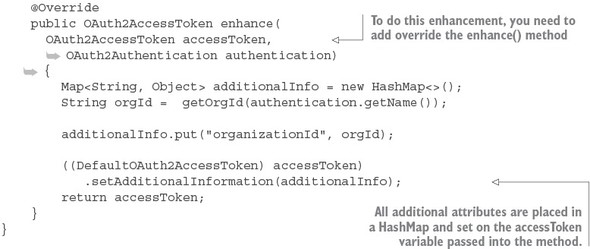

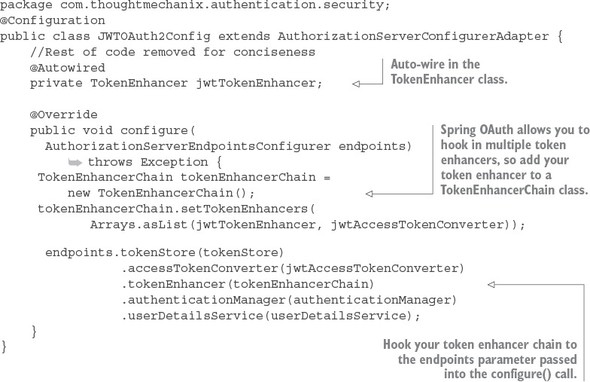

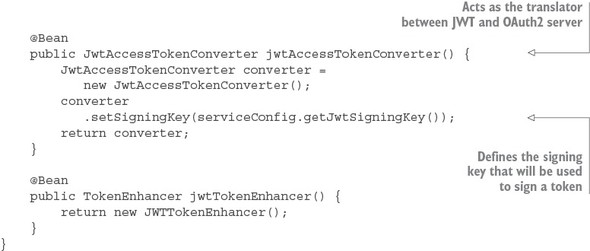

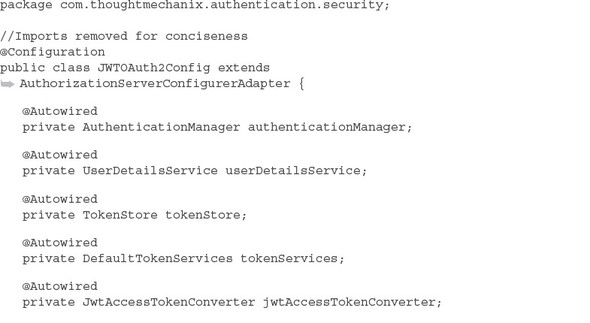

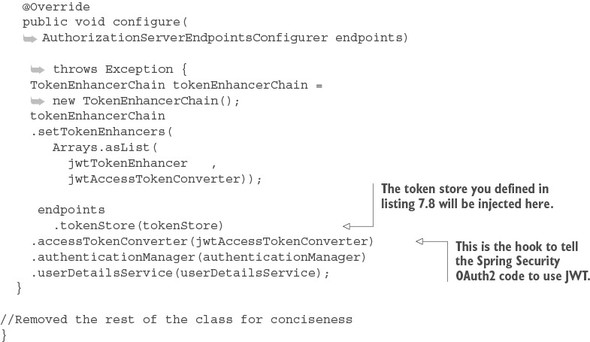

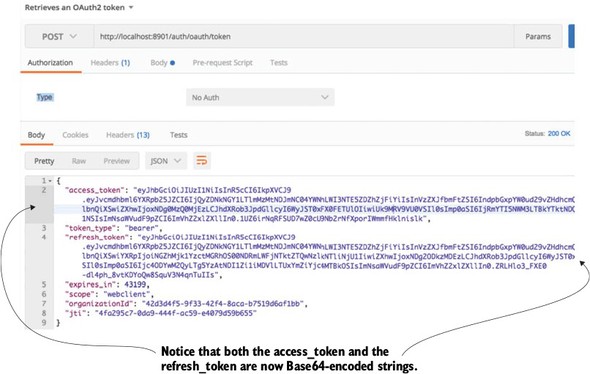

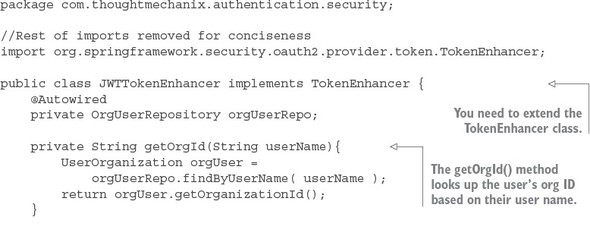

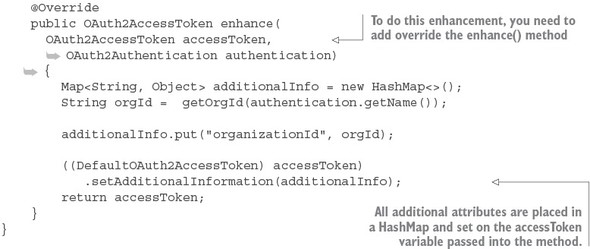

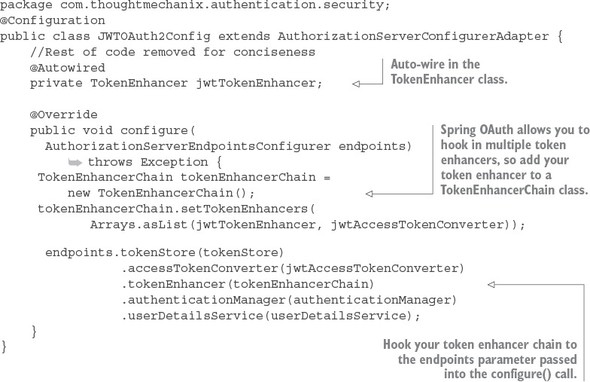

7.4.1. Modifying the authentication service to issue JavaScript Web Tokens

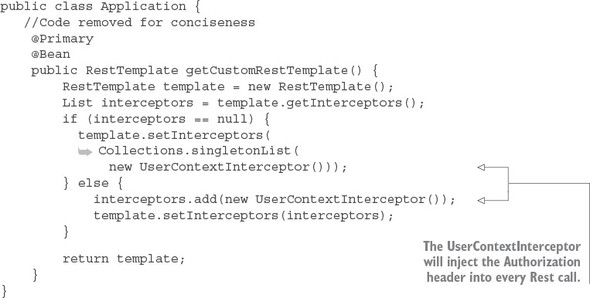

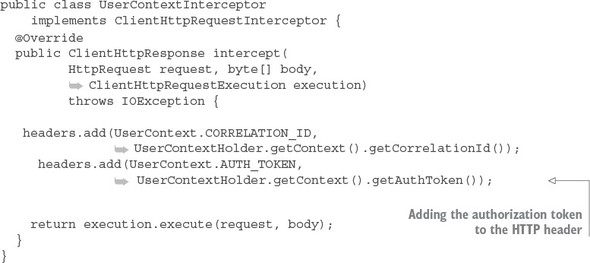

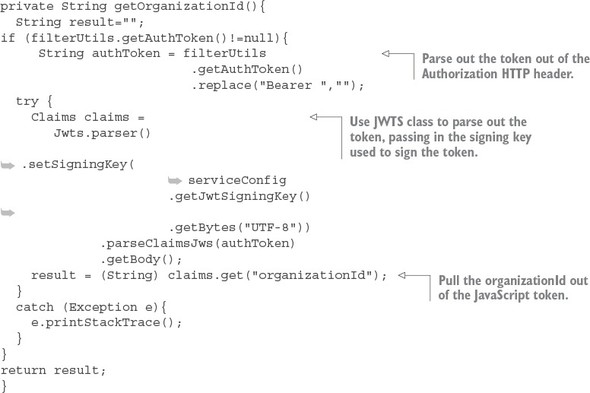

7.4.2. Consuming JavaScript Web Tokens in your microservices

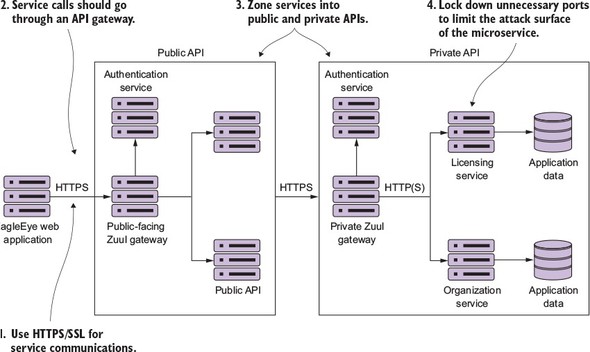

7.5. Some closing thoughts on microservice security

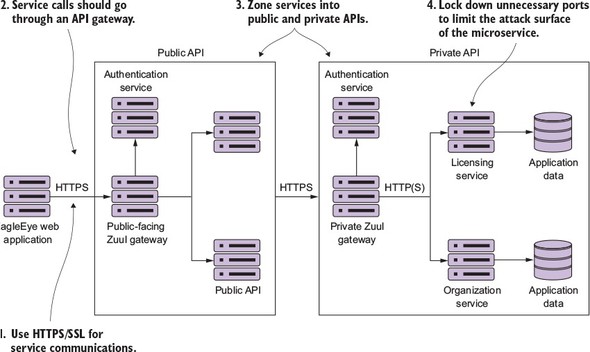

Use HTTPS/Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) for all service communication

Use a services gateway to access your microservices

Zone your services into a public API and private API

Limit the attack surface of your microservices by locking down unneeded network ports

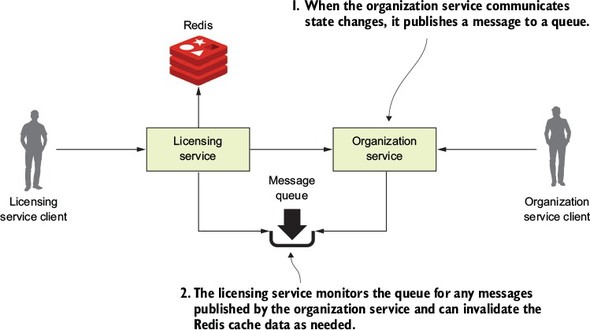

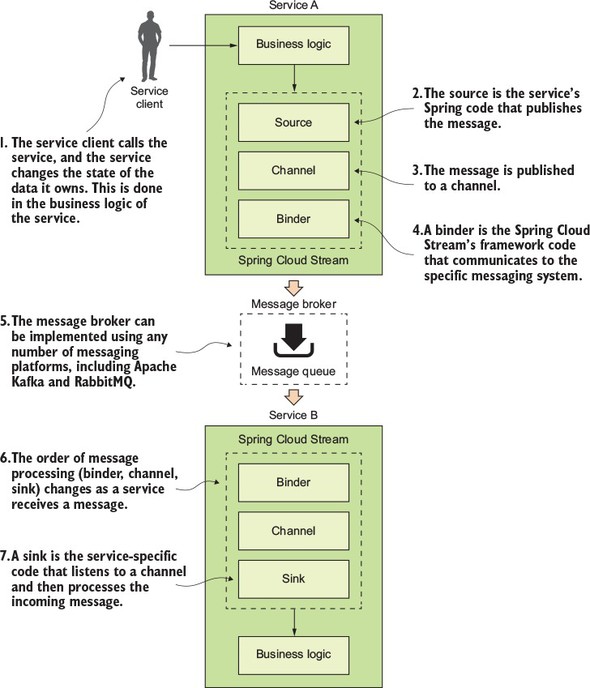

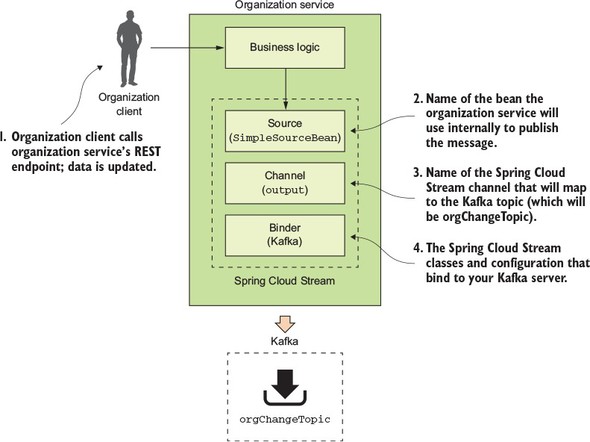

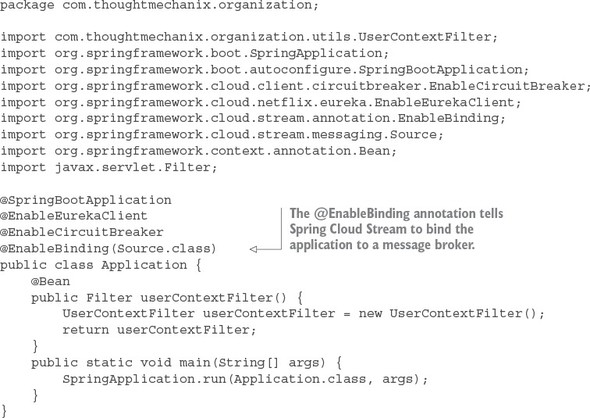

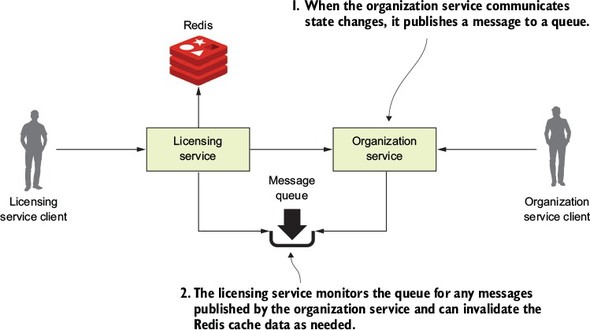

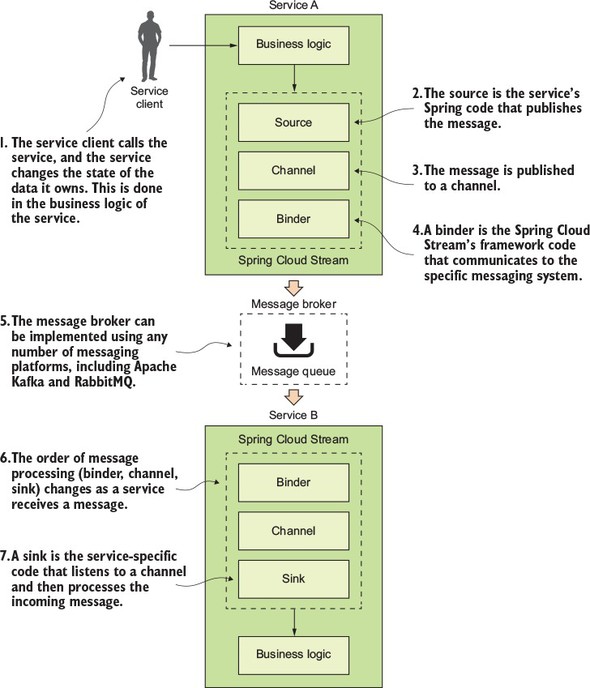

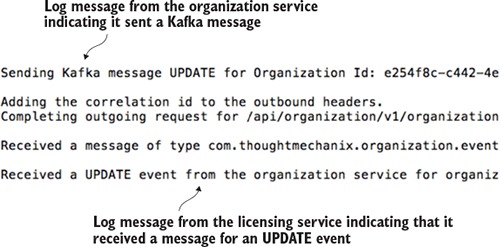

Chapter 8. Event-driven architecture with Spring Cloud Stream

8.1. The case for messaging, EDA, and microservices

8.1.1. Using synchronous request-response approach to communicate state change

8.1.2. Using messaging to communicate state changes between services

8.2. Introducing Spring Cloud Stream

8.3. Writing a simple message producer and consumer

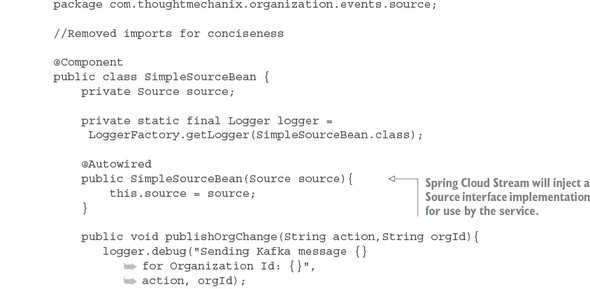

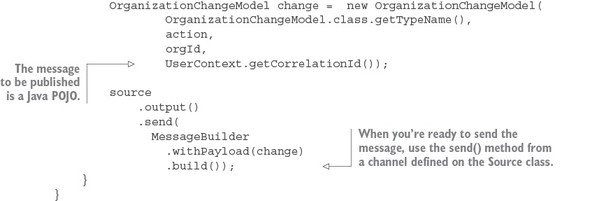

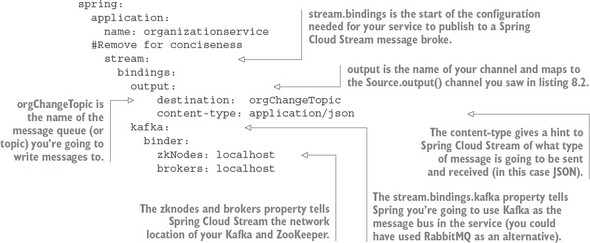

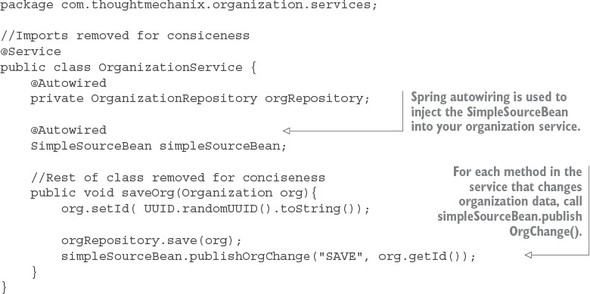

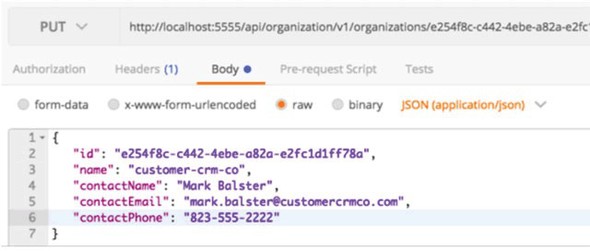

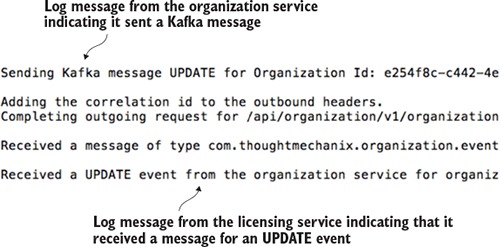

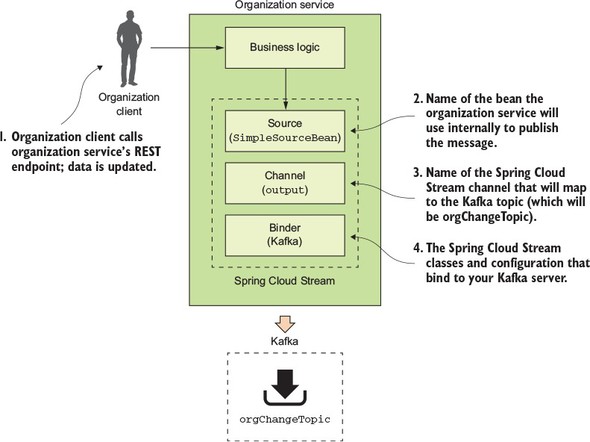

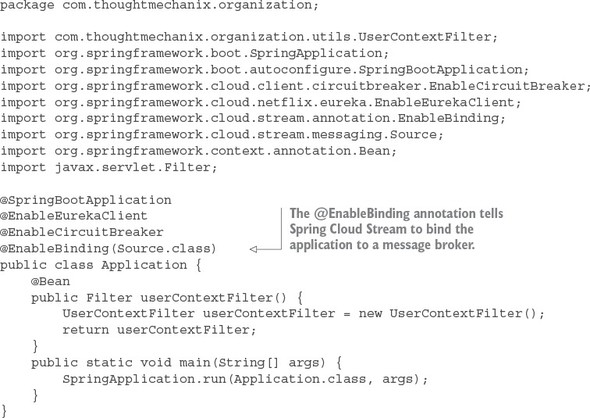

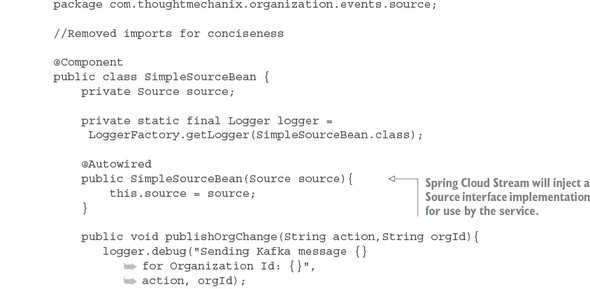

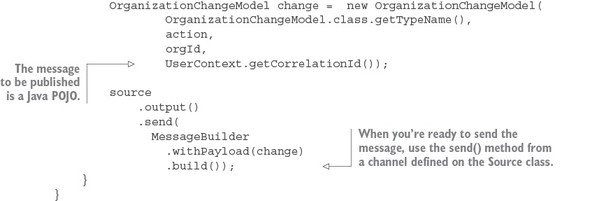

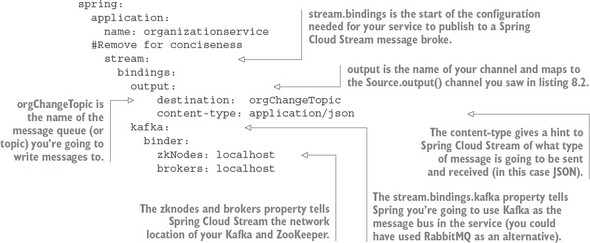

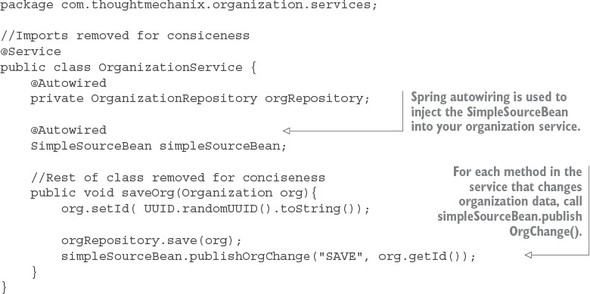

8.3.1. Writing the message producer in the organization service

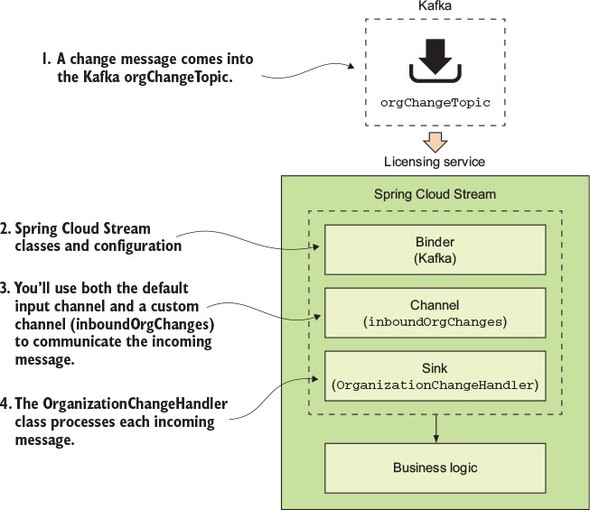

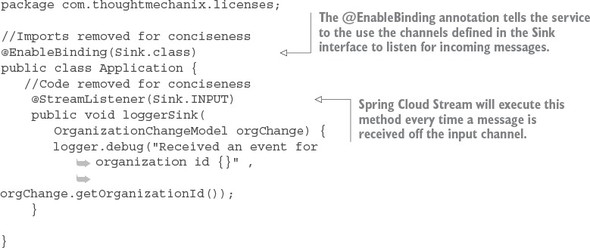

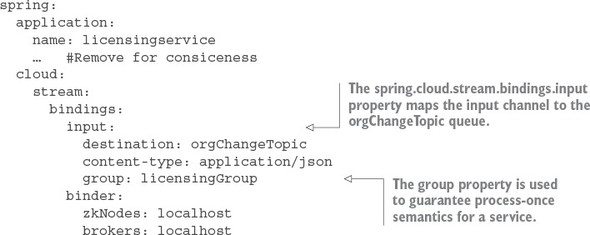

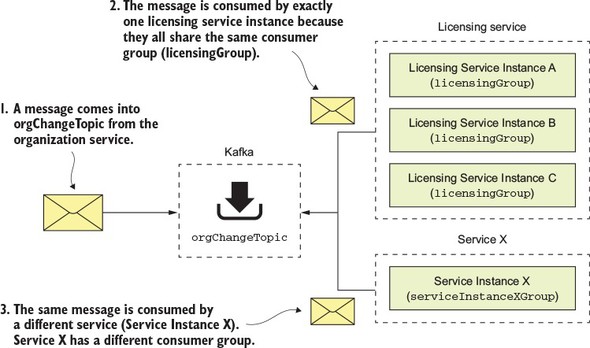

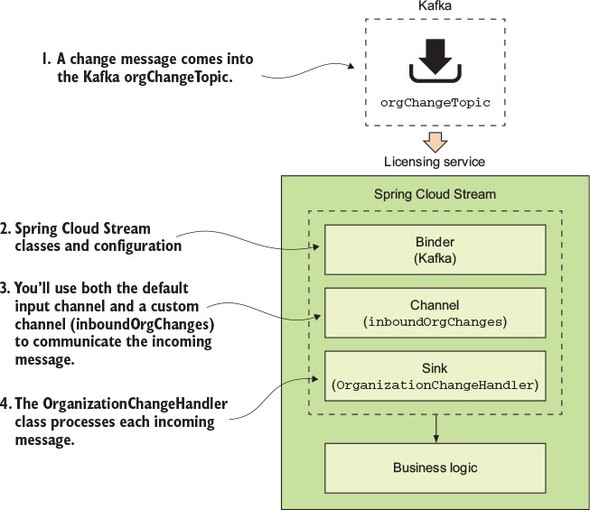

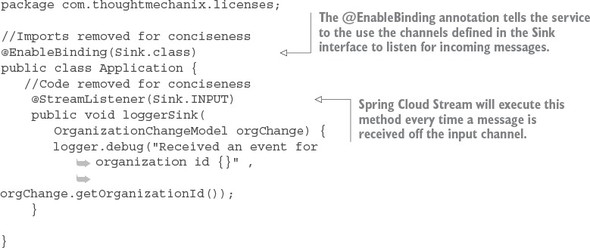

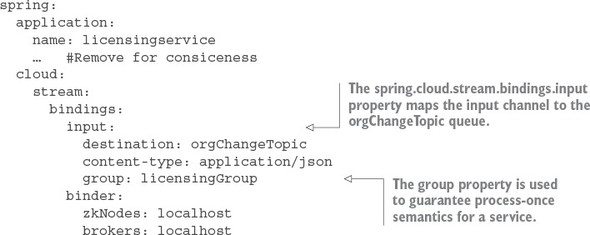

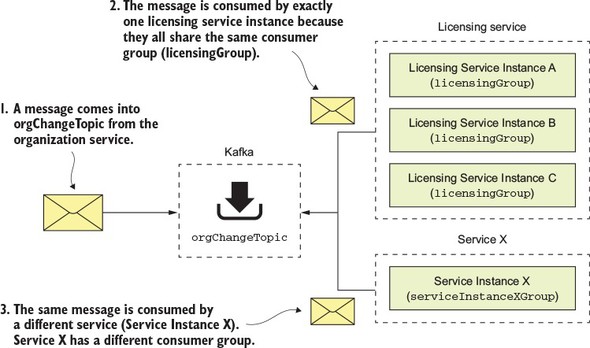

8.3.2. Writing the message consumer in the licensing service

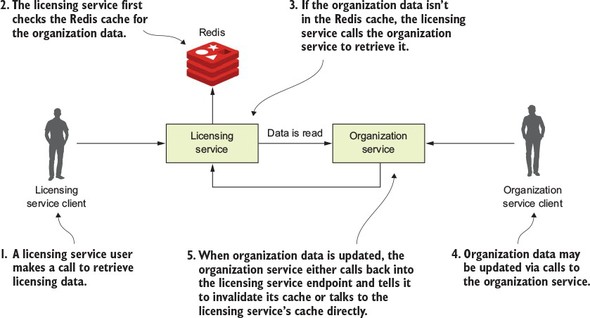

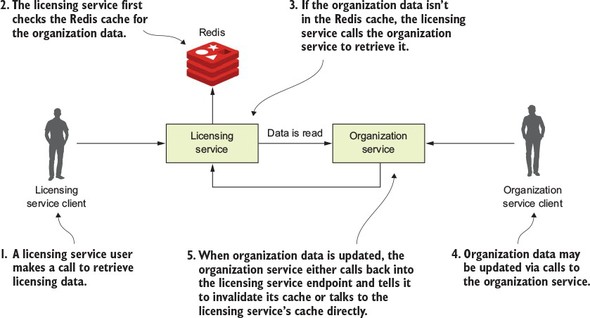

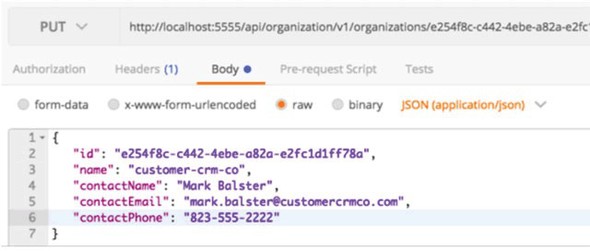

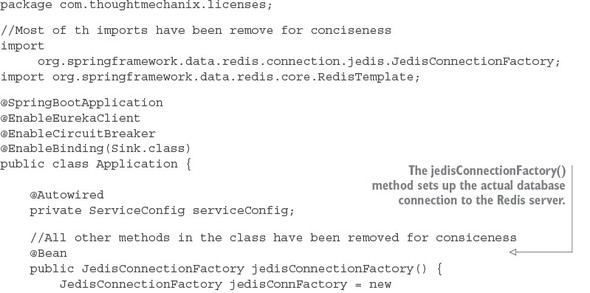

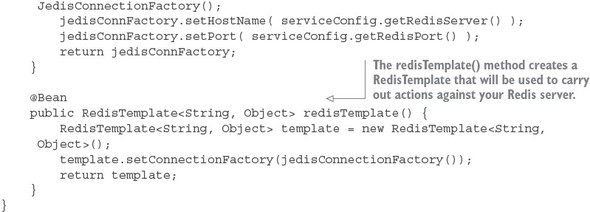

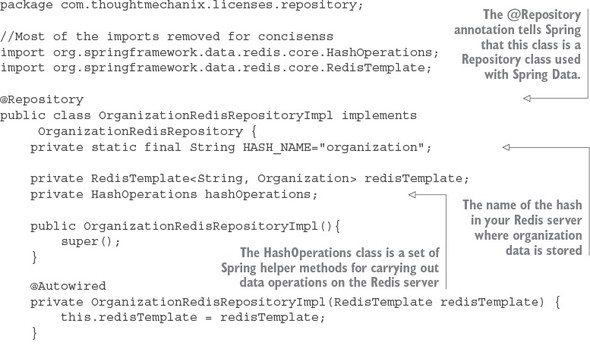

8.4. A Spring Cloud Stream use case: distributed caching

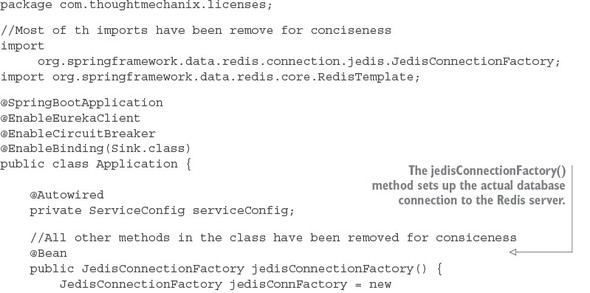

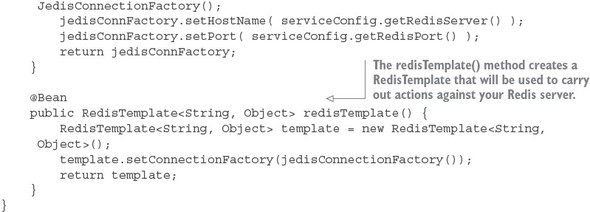

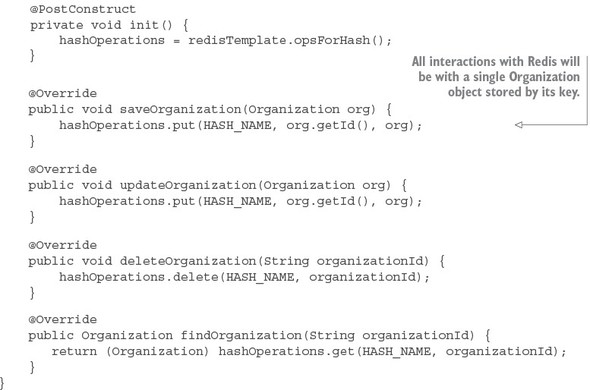

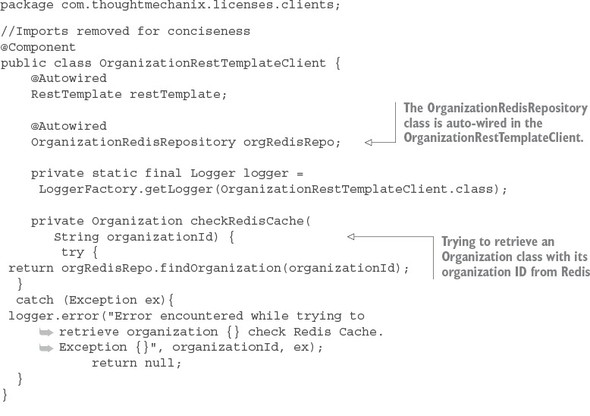

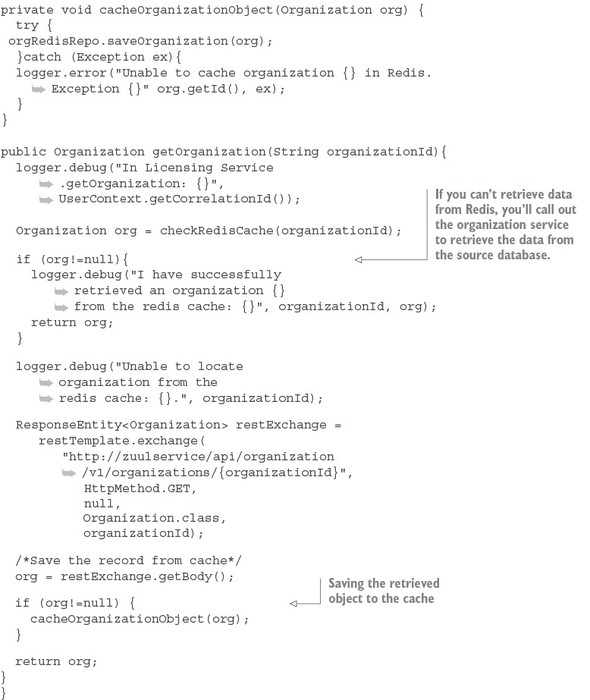

8.4.1. Using Redis to cache lookups

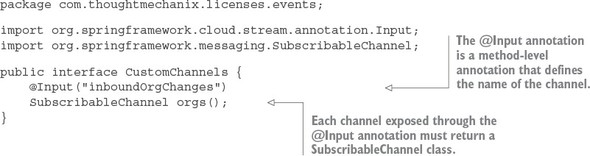

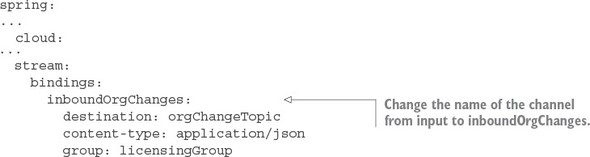

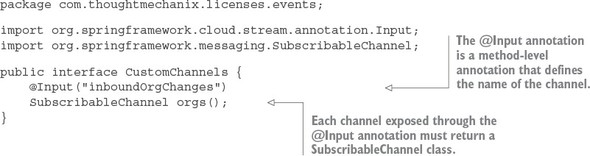

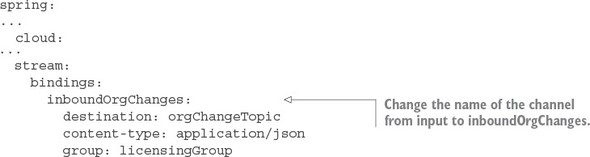

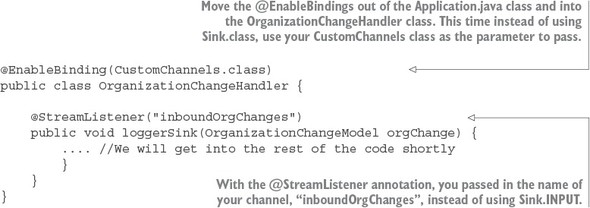

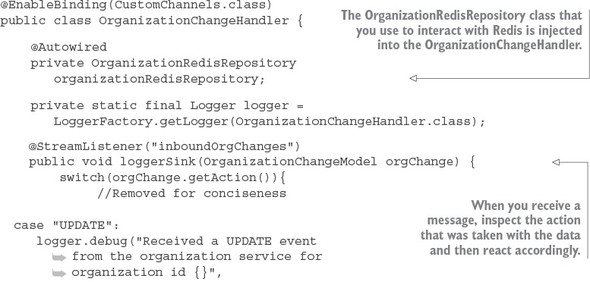

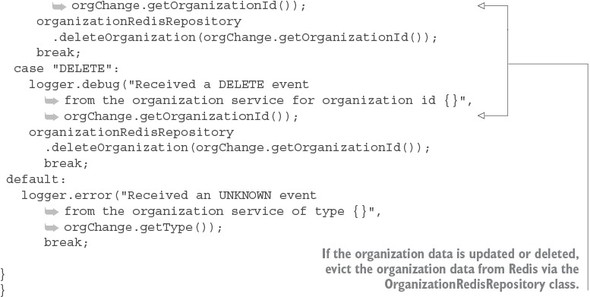

8.4.2. Defining custom channels

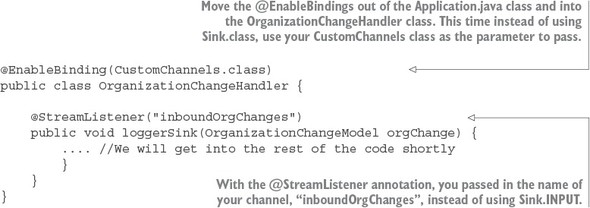

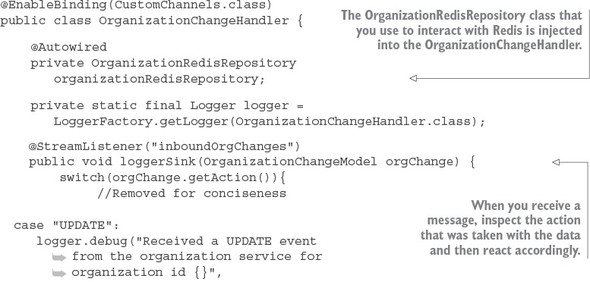

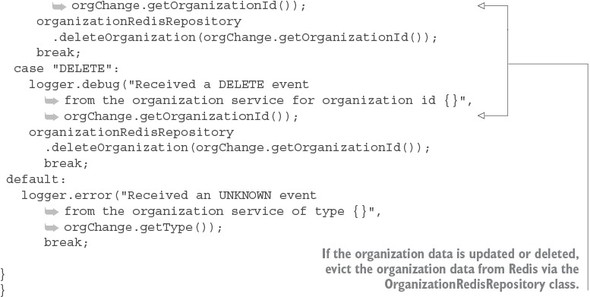

8.4.3. Bringing it all together: clearing the cache when a message is received

Chapter 9. Distributed tracing with Spring Cloud Sleuth and Zipkin

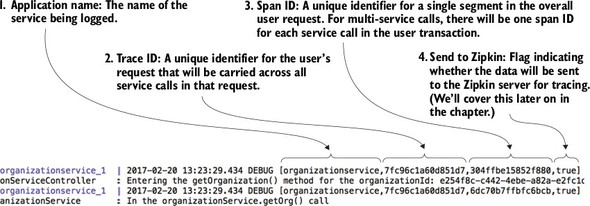

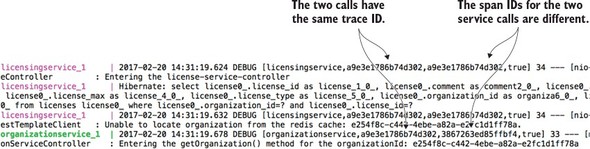

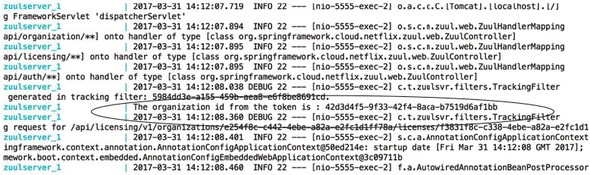

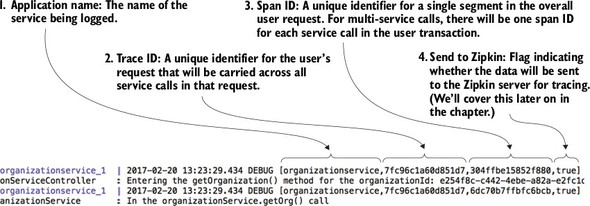

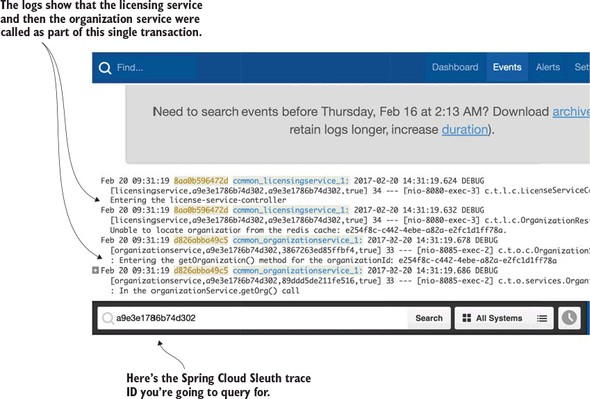

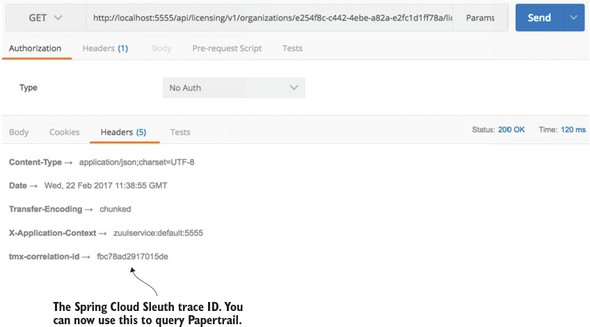

9.1. Spring Cloud Sleuth and the correlation ID

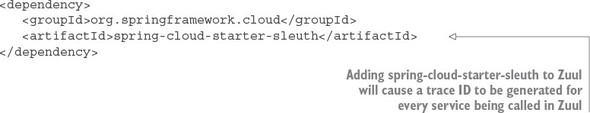

9.1.1. Adding Spring Cloud sleuth to licensing and organization

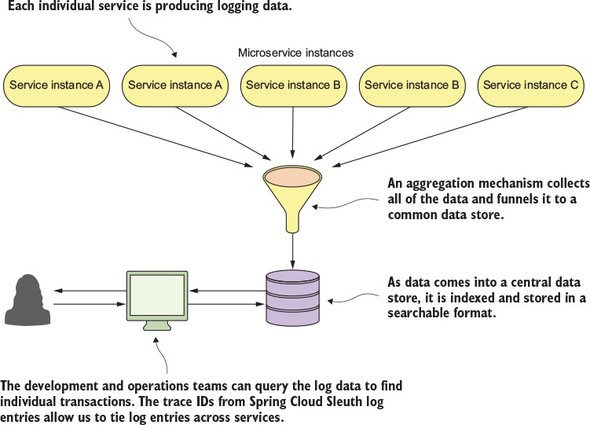

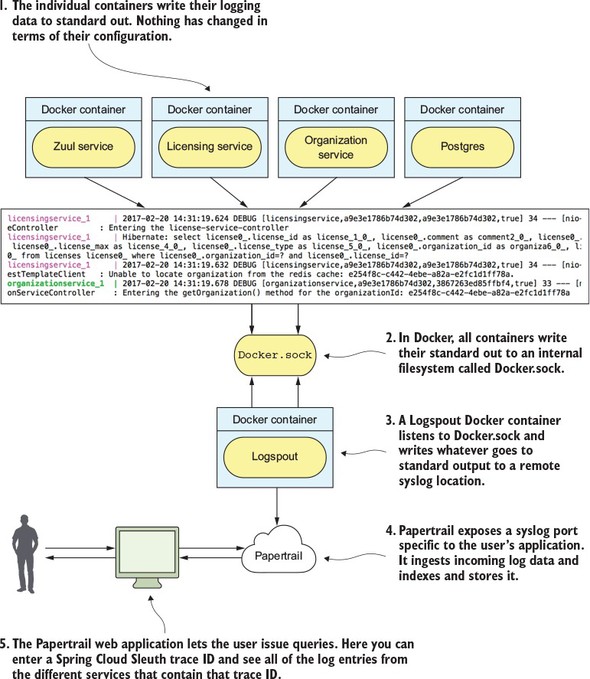

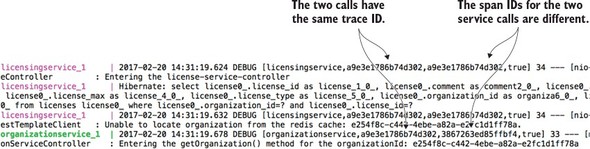

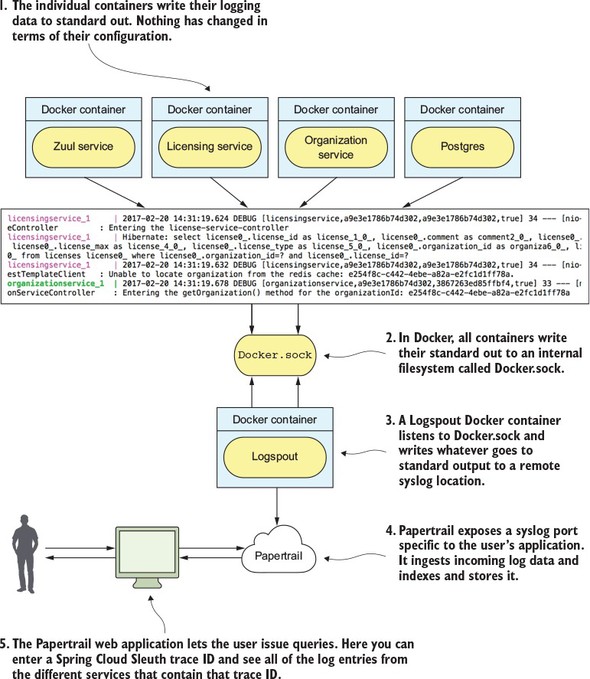

9.2. Log aggregation and Spring Cloud Sleuth

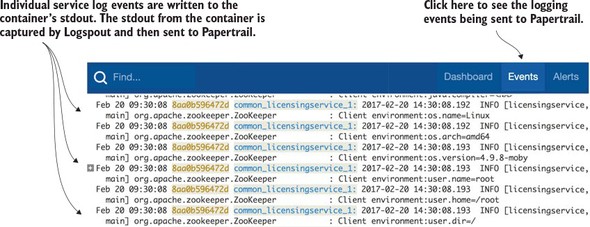

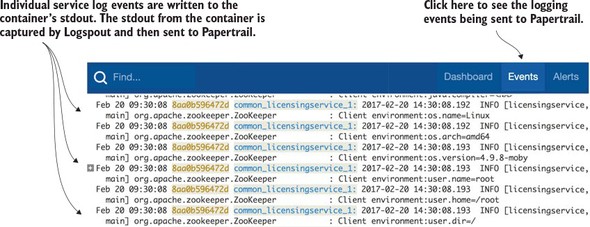

9.2.1. A Spring Cloud Sleuth/Papertrail implementation in action

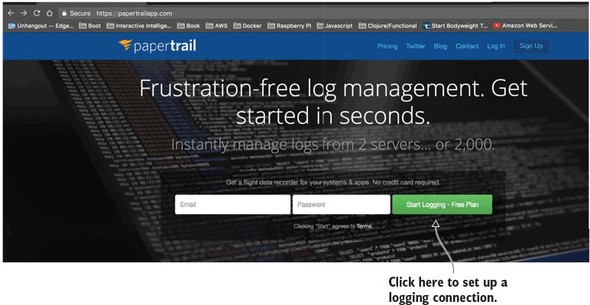

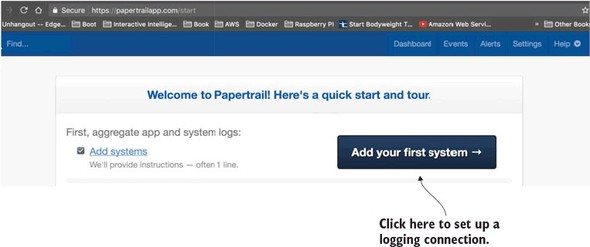

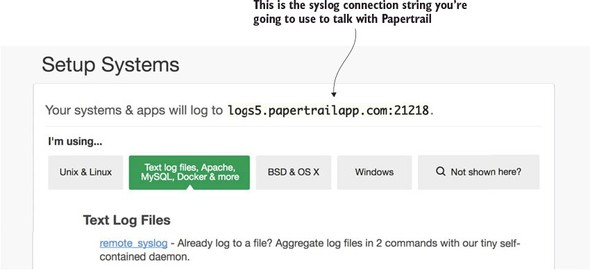

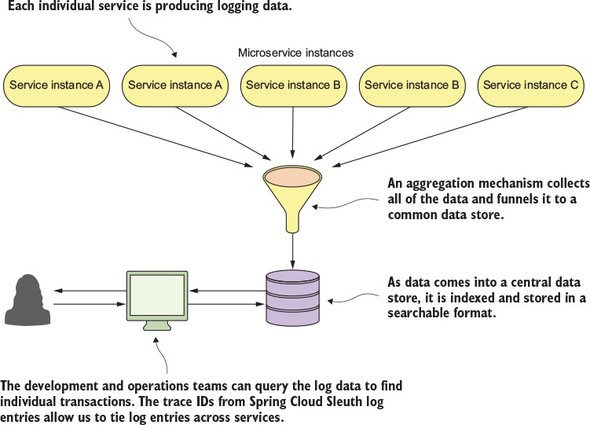

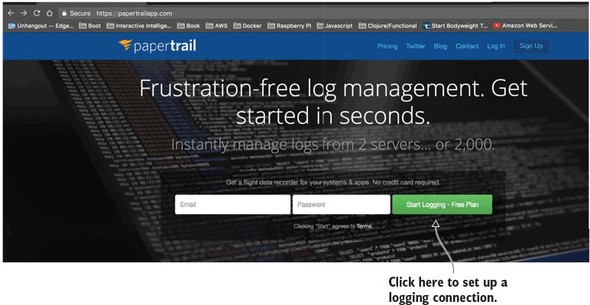

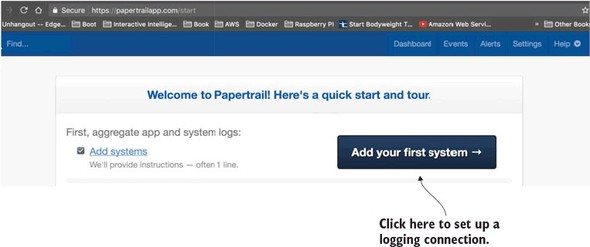

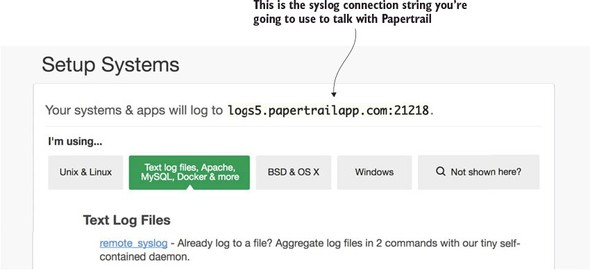

9.2.2. Create a Papertrail account and configure a syslog connector

9.2.3. Redirecting Docker output to Papertrail

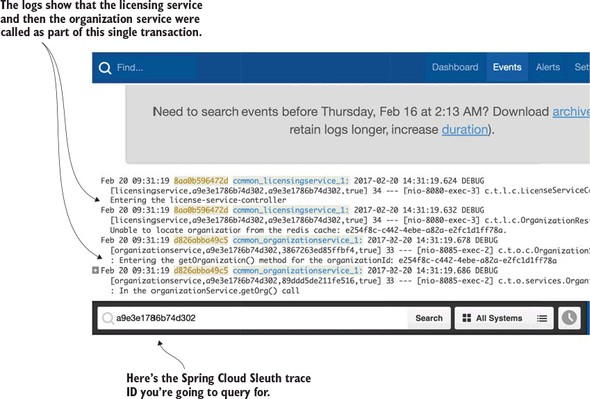

9.2.4. Searching for Spring Cloud Sleuth trace IDs in Papertrail

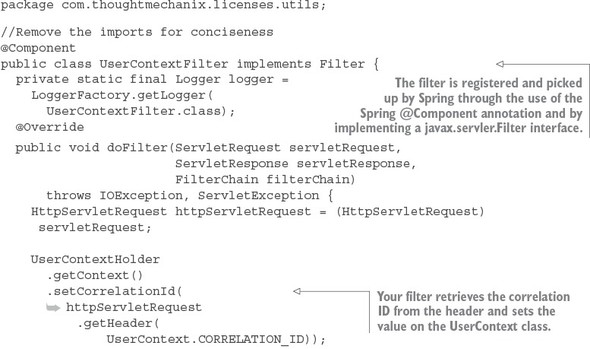

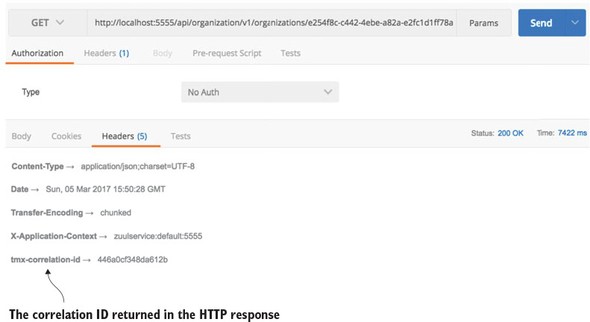

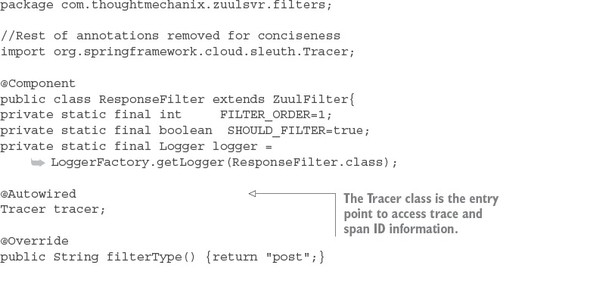

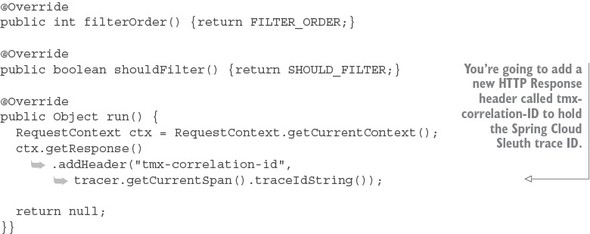

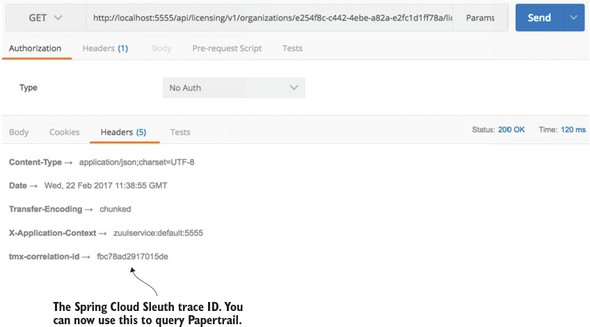

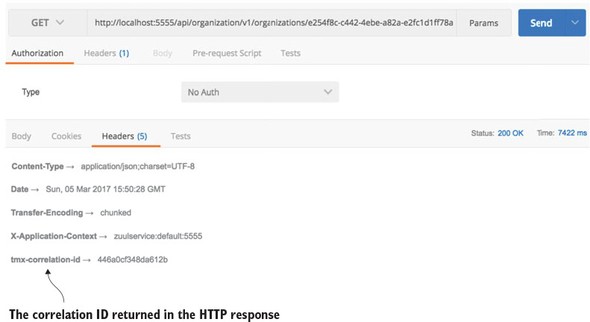

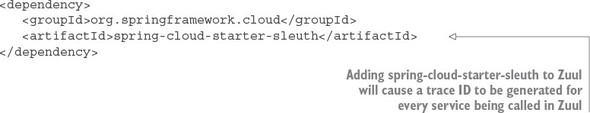

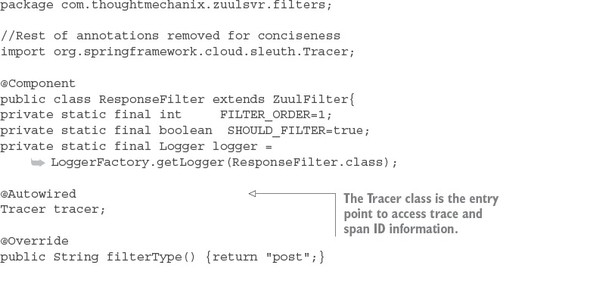

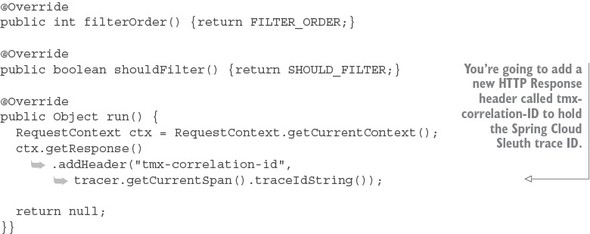

9.2.5. Adding the correlation ID to the HTTP response with Zuul

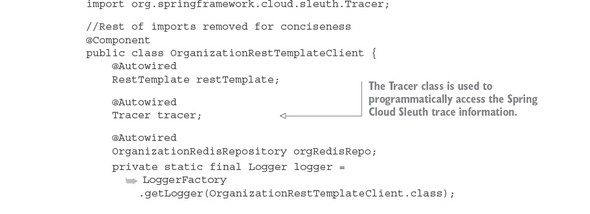

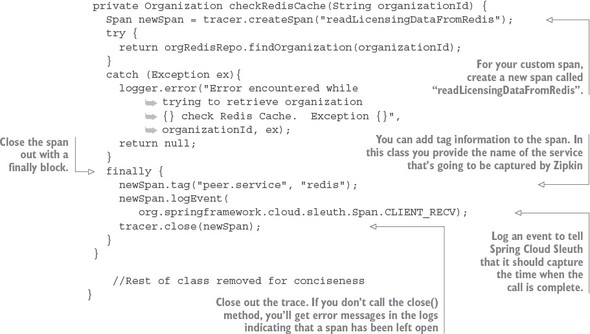

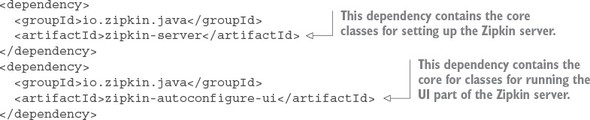

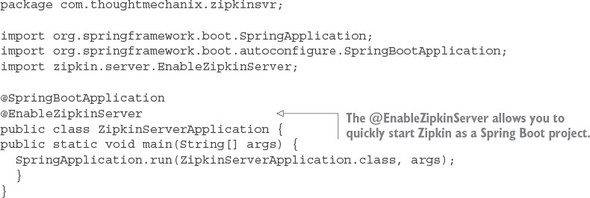

9.3. Distributed tracing with Open Zipkin

9.3.1. Setting up the Spring Cloud Sleuth and Zipkin dependencies

9.3.2. Configuring the services to point to Zipkin

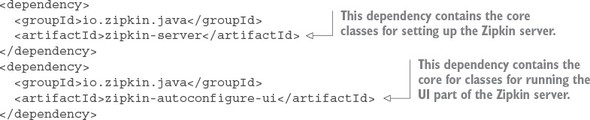

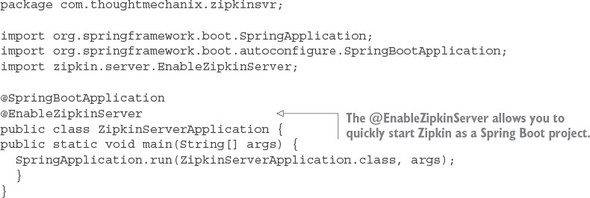

9.3.3. Installing and configuring a Zipkin server

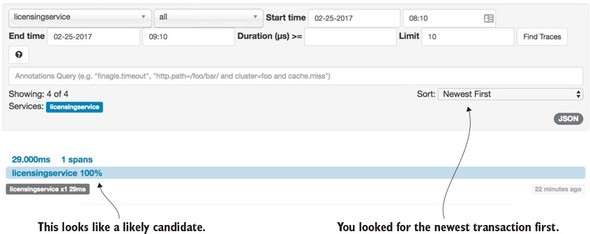

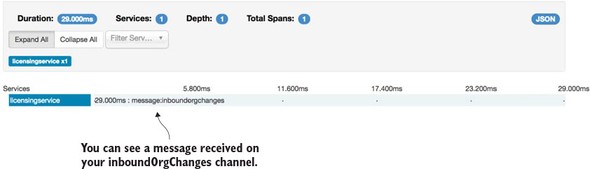

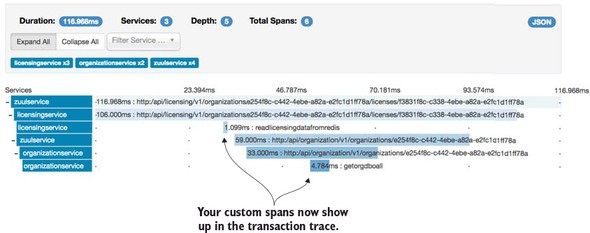

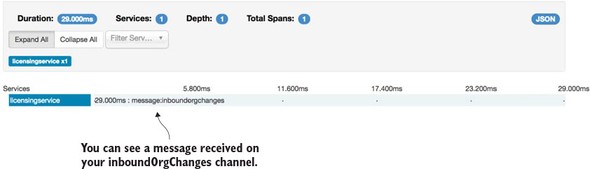

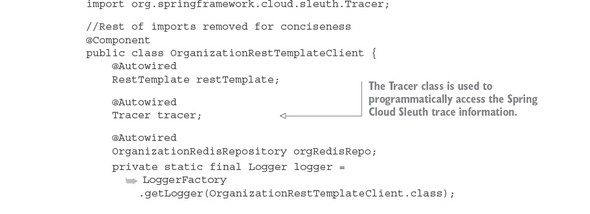

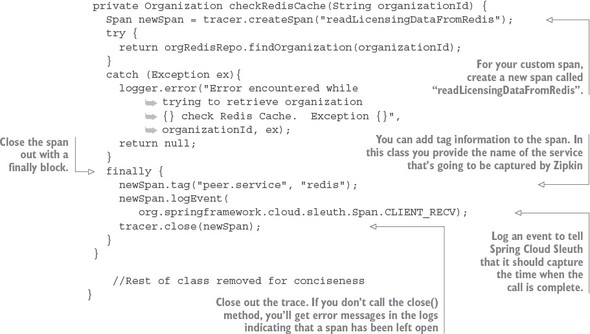

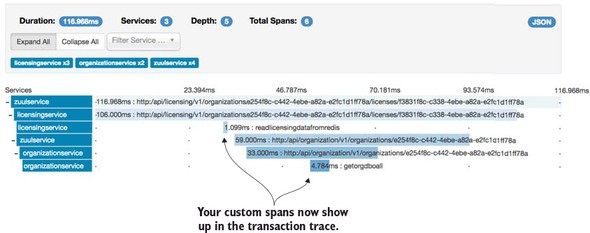

9.3.5. Using Zipkin to trace transactions

9.3.6. Visualizing a more complex transaction

Chapter 10. Deploying your microservices

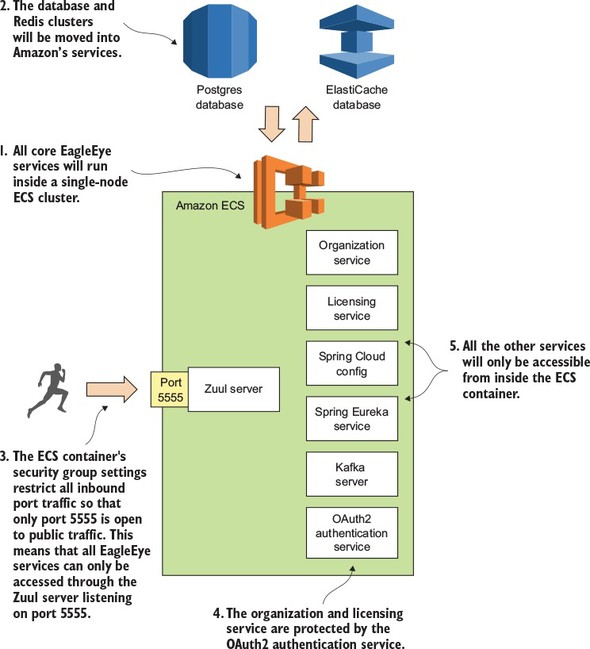

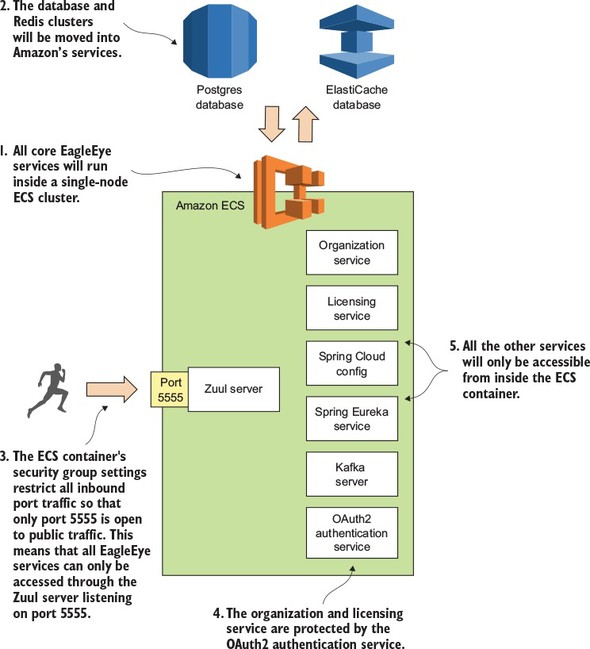

10.1. EagleEye: setting up your core infrastructure in the cloud

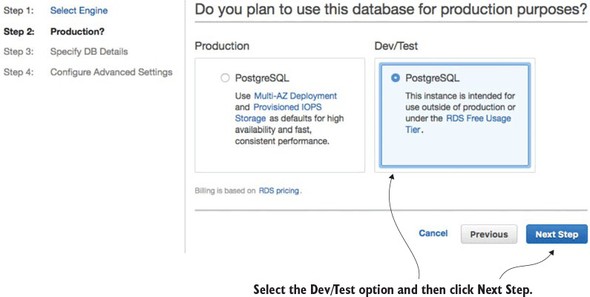

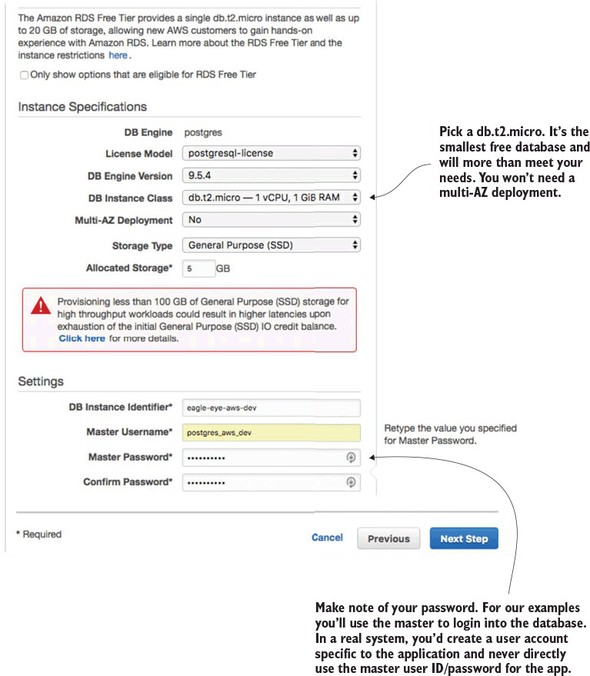

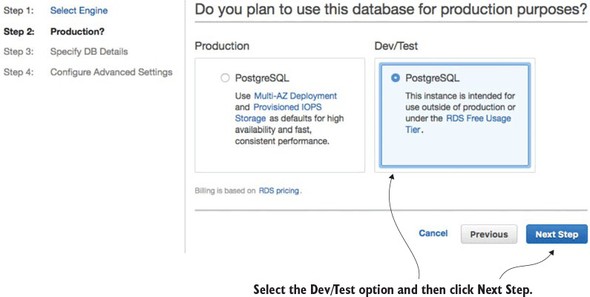

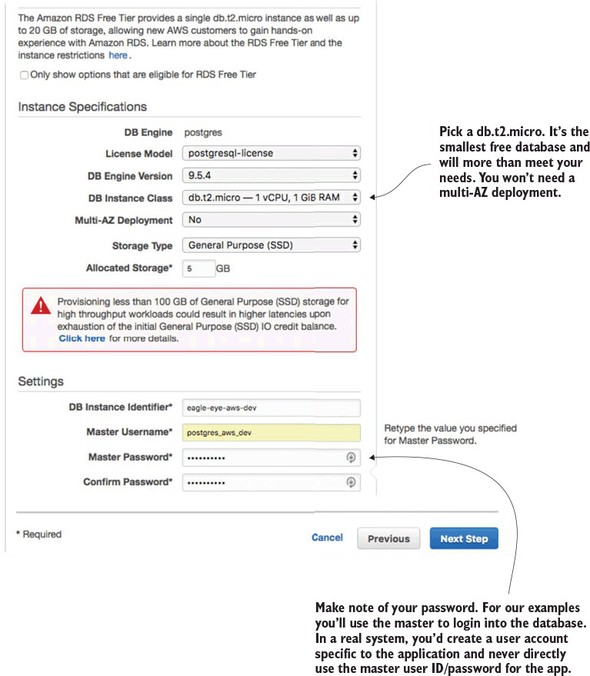

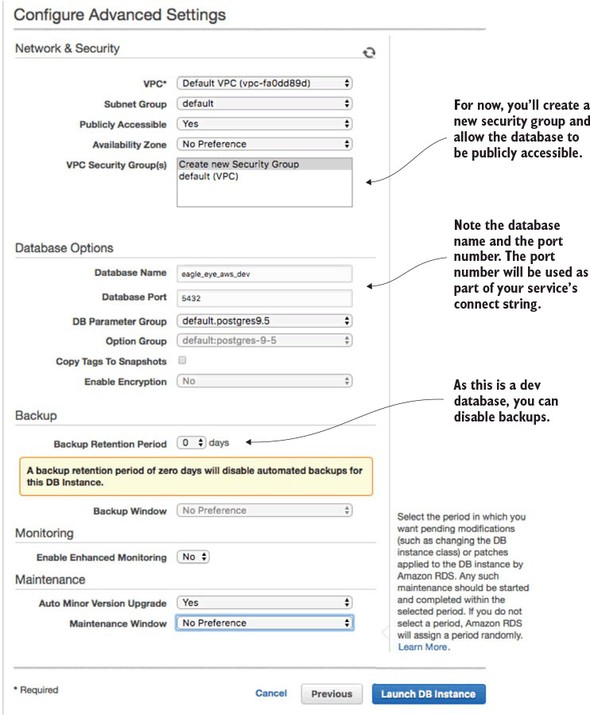

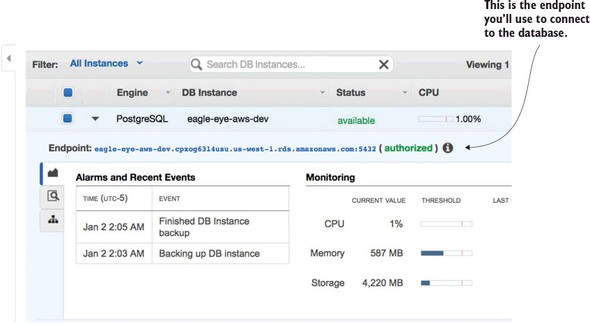

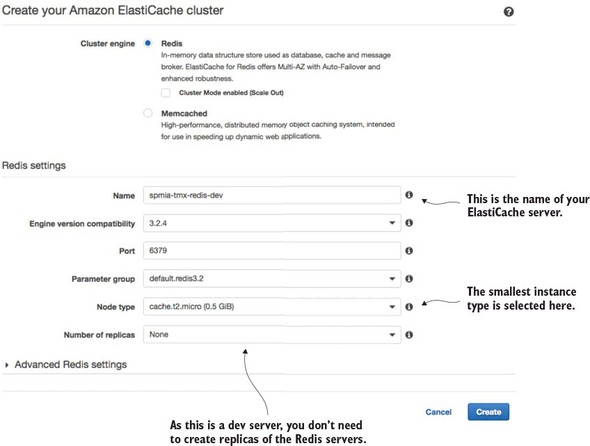

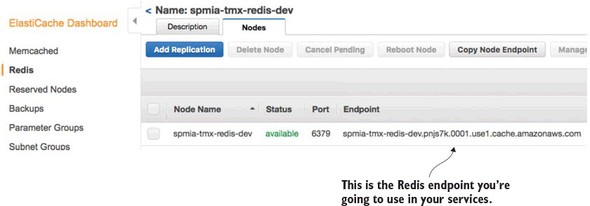

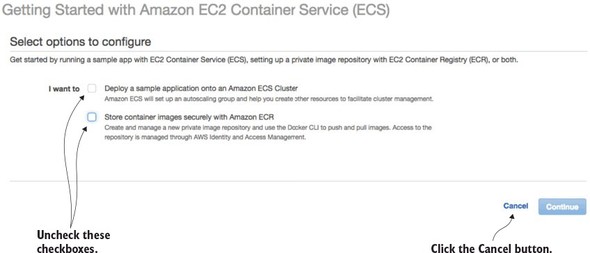

10.1.1. Creating the PostgreSQL database using Amazon RDS

10.2. Beyond the infrastructure: deploying EagleEye

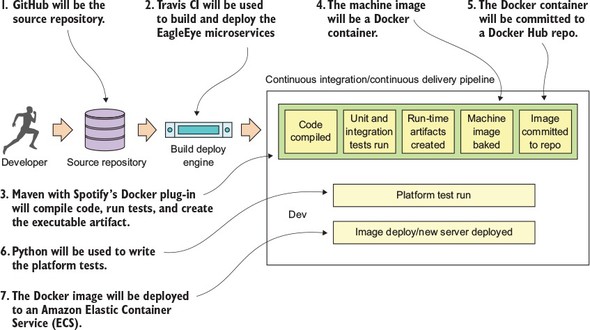

10.3. The architecture of a build/deployment pipeline

10.4. Your build and deployment pipeline in action

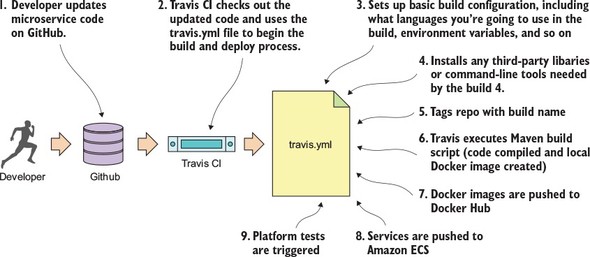

10.5. Beginning your build deploy/pipeline: GitHub and Travis CI

10.6. Enabling your service to build in Travis CI

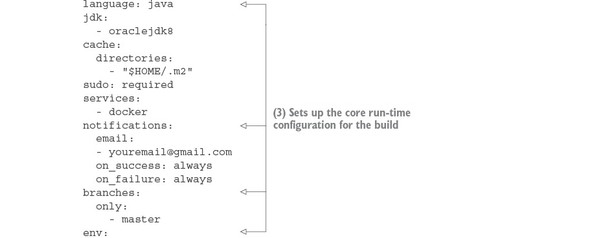

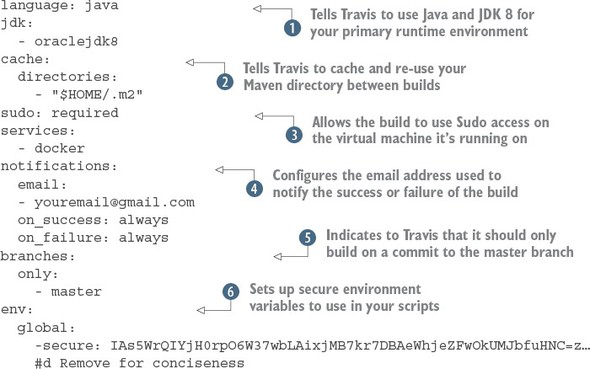

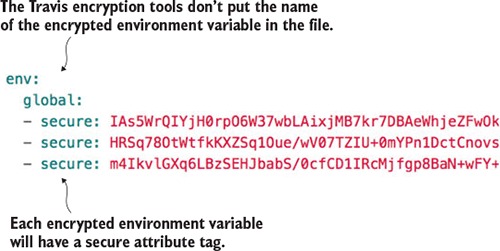

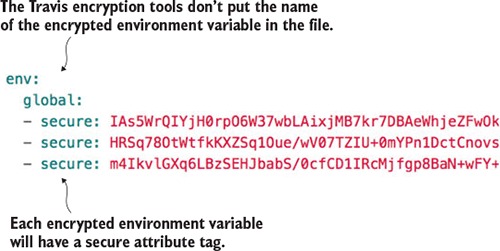

10.6.1. Core build run-time configuration

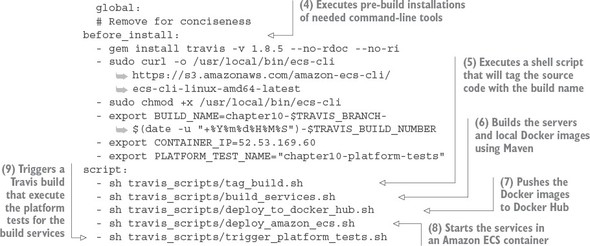

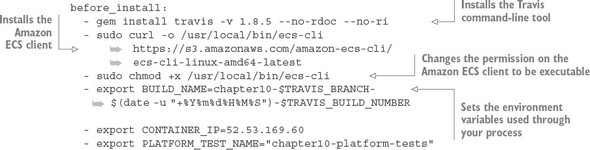

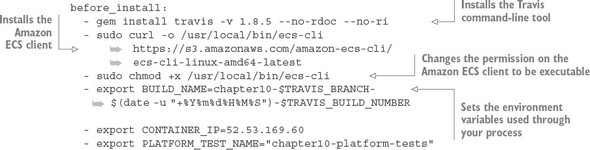

10.6.2. Pre-build tool installations

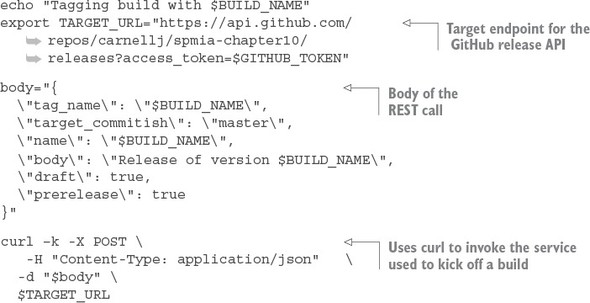

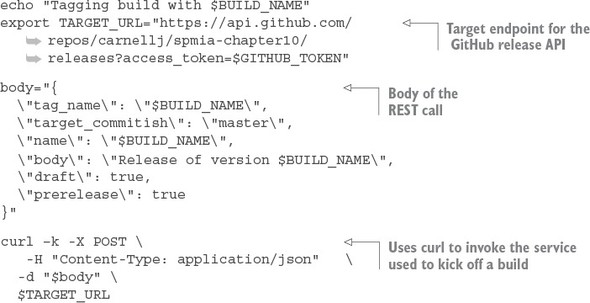

10.6.4. Tagging the source control code

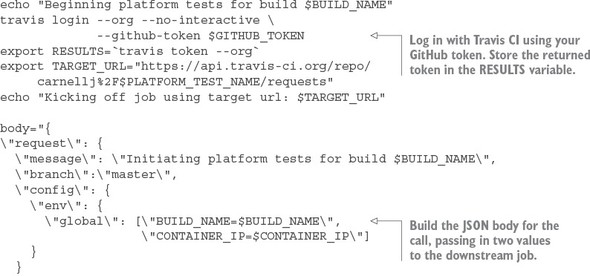

10.6.5. Building the microservices and creating the Docker images

10.6.6. Pushing the images to Docker Hub

Appendix A. Running a cloud on your desktop

A.2. Downloading the projects from GitHub

A.4. Building and compiling the projects

Appendix B. OAuth2 grant types

It’s ironic that in writing a book, the last part of the book you write is often the beginning of the book. It’s also often the most difficult part to put down on paper. Why? Because you have to explain to everyone why you’re so passionate about a subject that you spent the last one and a half years of your life writing a book about it. It’s hard to articulate why anyone would spend such a large amount of time on a technical book. One rarely writes software books for the money or the fame.

Here’s the reason why I wrote this book: I love writing code. It’s a calling for me and it’s also a creative activity—akin to drawing, painting, or playing an instrument. Those outside the field of software development have a hard time understanding this. I especially like building distributed applications. For me, it’s an amazing thing to see an application work across dozens (even hundreds) of servers. It’s like watching an orchestra playing a piece of music. While the final product of an orchestra is beautiful, the making of it is often a lot of hard work and requires a significant amount of practice. The same goes for writing a massively distributed application.

Since I entered the software development field 25 years ago, I’ve watched the industry struggle with the “right” way to build distributed applications. I’ve seen distributed service standards such as CORBA rise and fall. Monstrously big companies have tried to push big and, often, proprietary protocols. Anyone remember Microsoft’s Distributed Component Object Model (DCOM) or Oracle’s J2EE’s Enterprise Java Beans 2 (EJB)? I watched as technology companies and their followers rushed to build service-oriented architectures (SOA) using heavy XML-based schemas.

In each case, these approaches for building distributed systems often collapsed under their own weight. I’m not saying that these technologies weren’t used to build some very powerful applications. The reality is that they couldn’t keep up with the demand of the users. Ten years ago, smartphones were just being introduced to the market and cloud computing was in the earliest stage of infancy. Also, the standards and technology for distributed application development were too complicated for the average developer to understand and easily use in practice. Nothing speaks truth in the software development industry like written code. When the standards get in the way of this, the standards quickly get discarded.

When I first heard of the microservices approach to building applications I was more than a little skeptical. “Great, another silver-bullet approach to building distributed applications,” I thought. However, as I started diving into the concepts, I realized the simplicity of microservices could be a game changer. A microservice architecture focuses on building small services that use simple protocols (HTTP and JSON) to communicate. That’s it. You can write a microservice with nearly any programming language. There’s beauty in this simplicity.

However, while building an individual microservice is easy, operationalizing and scaling it is difficult. Getting hundreds of small distributed components to work together and then building a resilient application from them can be incredibly difficult to do. In distributed computing, failure is a fact of life and how your application deals with it is incredibly difficult to get right. To paraphrase my colleagues Chris Miller and Shawn Hagwood: “If it’s not breaking once in a while, you’re not building.”

It’s these failures that inspired me to write this book. I hate to build things from scratch when I don’t have to. The reality is that Java is the lingua franca for most application development efforts, especially in the enterprise. The Spring framework has for many organizations become the de facto framework for most application development. I’d already been doing application development in Java for almost 20 years (I remember the Dancing Duke applet) and Spring for almost 10 years. As I began my microservices journey, I was delighted and excited to watch the emergence of Spring Cloud.

The Spring Cloud framework provides out-of-the-box solutions for many of the common development and operational problems you’ll run into as a microservice developer. Spring Cloud lets you use only the pieces you need and minimizes the amount of work you need to do to build and deploy production-ready Java micro-services. It does this by using other battle-hardened technologies from companies and groups such as Netflix, HashiCorp, and the Apache foundation.

I’ve always considered myself an average developer who, at the end of the day, has deadlines to meet. That’s why I undertook the project of writing this book. I wanted a book that I could use in my day-to-day work. I wanted something with direct (and hopefully) straightforward code examples. I always want to make sure that the material in this book can be consumed as individual chapters or in its entirety. I hope you find this book useful and I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

As I sit down to write these acknowledgments, I can’t help but think back to 2014 when I ran my first marathon. Writing a book is a lot like running a marathon. Writing the proposal and the outline for the book is much like the training process. It gets your thoughts in shape, it focuses you for what’s ahead and, yes, near the end of the process, it can be more than a little tedious and brutal.

When you start writing the book, it’s a lot like race day. You start the marathon excited and full of energy. You know you’re trying to do something bigger than anything you might have done before and it’s both exciting and nerve-wracking. This is what you’ve trained for, but at the same time, there’s always that small voice of doubt in the back of your mind that says you won’t finish what you started.

What I’ve learned from running is that races aren’t completed one mile at a time. Instead, they’re run one foot in front of the other. The miles run are the sum of the individual footsteps. When my children are struggling with something, I laugh and ask them, “How do you write a book? One word, one single step at a time.” They usually roll their eyes, but in the end there’s no other way around this indisputable and ironclad law.

However, when you run a marathon, you might be the one running the race, but you’re never running it alone. There’s a whole team of people there to give you support, time, and advice along the way. It has been the same experience writing this book.

I’d like to start by thanking Manning for the support they gave me in writing this book. It started with Greg Wild, my acquisitions editor, who patiently worked with me as I refined the core concepts in this book and guided me through the proposal process. Along the way, Marina Michaels, my development editor, kept me honest and challenged me to become a better author. I’d also like to thank Raphael Villela and Joshua White, my technical editors, who constantly checked my work and ensured the overall quality of the examples and the code I produced. I’m extremely grateful for the time, talent, and commitment each of these individuals put into into the overall project. I’d also like to thank the reviewers who provided feedback on the manuscript throughout the writing and development process: Aditya Kumar, Adrian M. Rossi, Ashwin Raj, Christian Bach, Edgar Knapp, Jared Duncan, Jiri Pik, John Guthrie, Mirko Bernardoni, Paul Balogh, Pierluigi Riti, Raju Myadam, Rambabu Posa, Sergey Evsikov, and Vipul Gupta.

I want to close these acknowledgments with a deep sense of thanks for the love and time my family has given me in working on this project. To my wife Janet, you have been my best friend and the love of my life. When I’m tired and want to give up, I only have to listen for the sound of your footsteps next to me to know that you’re always running beside me, never telling me no, and always pushing me forward.

To my son Christopher, you’re growing up to be an incredible young man. I cannot wait for the day when you truly discover your passion, because there will be nothing in this world that can stop you from reaching your goals.

To my daughter Agatha, I’d give all the money I have to see the world through your eyes for just 10 minutes. The experience would make me a better author and more importantly a better person. Your intellect, your power of observation, and creativity humble me.

To my four-year-old son, Jack: Buddy, thank you being patient with me whenever I said, “I can’t play right now because Daddy has to work on the book.” You always make me laugh and you make this whole family complete. Nothing makes me happier than when I see you being the jokester and playing with everyone in the family.

My race with this book is done. Like my marathon, I’ve left nothing on the table in writing this book. I have nothing but gratitude for the Manning team and the MEAP readers who bought this book early and gave me so much valuable feedback. I hope in the end that you enjoy this book as much as I enjoyed writing it. Thank you.

Spring Microservices in Action was written for the practicing Java/Spring developer who needs hands-on advice and examples of how to build and operationalize microservice-based applications. When I wrote this book, I wanted it to be based around core microservice patterns that aligned with Spring Boot and Spring Cloud examples that demonstrated the patterns in action. As such, you’ll find specific microservice design patterns discussed in almost every chapter, along with examples of the patterns implemented using Spring Boot and Spring Cloud.

Spring Microservices in Action consists of 10 chapters and two appendixes:

Spring Microservices in Action includes code in every chapter. All code examples are available in my GitHub repository, and each chapter has its own repository. You can find an overview page with links to each chapter’s code repository at https://github.com/carnellj/spmia_overview. A zip containing all source code is also available from the publisher’s website at www.manning.com/books/spring-microservices-in-action.

All code in this book is built to run on Java 8 using Maven as the main build tool. Please refer to appendix A of this book for full details on the software tools you’ll need to compile and run the code examples.

One of the core concepts I followed as I wrote this book was that the code examples in each chapter should run independently of those in the other chapters. As such, every service we create for a chapter builds to a corresponding Docker image. When code from previous chapters is used, it’s included as both source and a built Docker image. We use Docker compose and the built Docker images to guarantee that you have a reproducible run-time environment for every chapter.

This book contains many examples of source code both in numbered listings and in line with normal text. In both cases, source code is formatted in a fixed-width font like this to separate it from ordinary text. Sometimes code is also in bold to highlight code that has changed from previous steps in the chapter, such as when a new feature adds to an existing line of code.

In many cases, the original source code has been reformatted; we’ve added line breaks and reworked indentation to accommodate

the available page space in the book. In rare cases, even this wasn’t enough, and listings include line-continuation markers

( ). Additionally, comments in the source code have often been removed from the listings when the code is described in the text.

Code annotations accompany many of the listings, highlighting important concepts.

). Additionally, comments in the source code have often been removed from the listings when the code is described in the text.

Code annotations accompany many of the listings, highlighting important concepts.

Purchase of Spring Microservices in Action includes free access to a private web forum run by Manning Publications where you can make comments about the book, ask technical questions, and receive help from the author and from other users. To access the forum and subscribe to it, point your web browser to www.manning.com/books/spring-microservices-in-action. This page provides information on how to get on the forum once you’re registered, what kind of help is available, and the rules of conduct on the forum.

Manning’s commitment to our readers is to provide a venue where a meaningful dialog between individual readers and between readers and the author can take place. It is not a commitment to any specific amount of participation on the part of the author, whose contributions to the AO remain voluntary (and unpaid). We suggest you ask the author challenging questions, lest his interest stray!

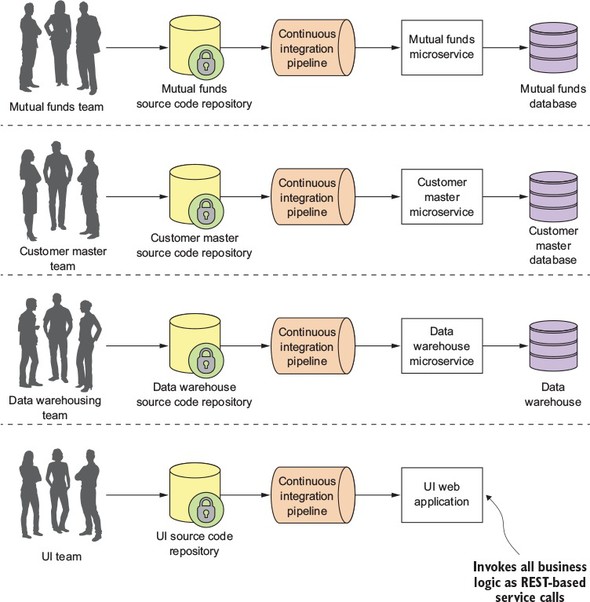

JOHN CARNELL is a senior cloud engineer at Genesys, where he works in Genesys’s PureCloud division. John spends the majority of his day hands-on building telephony-based microservices using the AWS platform. His day-to-day job centers on designing and building microservices across a number of technology platforms including Java, Clojure, and Go.

John is a prolific speaker and writer. He regularly speaks at local user groups and has been a regular speaker on “The No Fluff Just Stuff Software Symposium.” Over the last 20 years, John has authored, co-authored, and been a technical reviewer for a number of Java-based technology books and industry publications.

John holds a Bachelor of the Arts (BA) from Marquette University and a Masters of Business Administration (MBA) from the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh.

John is a passionate technologist and is constantly exploring new technologies and programming languages. When John isn’t speaking, writing, or coding, he lives with his wife Janet, his three children, Christopher, Agatha, and Jack, and yes, his dog Vader, in Cary, North Carolina.

During his free time (which there’s very little of) John runs, chases after his children, and studies Filipino martial arts.

John can be reached at john_carnell@yahoo.com.

The figure on the cover of Spring Microservices in Action is captioned a “A Man from Croatia.” This illustration is taken from a recent reprint of Balthasar Hacquet’s Images and Descriptions of Southwestern and Eastern Wenda, Illyrians, and Slavs, published by the Ethnographic Museum in Split, Croatia, in 2008. Hacquet (1739–1815) was an Austrian physician and scientist who spent many years studying the botany, geology, and ethnography of many parts of the Austrian Empire, as well as the Veneto, the Julian Alps, and the western Balkans, inhabited in the past by peoples of the Illyrian tribes. Hand drawn illustrations accompany the many scientific papers and books that Hacquet published.

The rich diversity of the drawings in Hacquet’s publications speaks vividly of the uniqueness and individuality of the eastern Alpine and northwestern Balkan regions just 200 years ago. This was a time when the dress codes of two villages separated by a few miles identified people uniquely as belonging to one or the other, and when members of a social class or trade could be easily distinguished by what they were wearing. Dress codes have changed since then and the diversity by region, so rich at the time, has faded away. It is now often hard to tell the inhabitant of one continent from another, and today the inhabitants of the picturesque towns and villages in the Slovenian Alps or Balkan coastal towns are not readily distinguishable from the residents of other parts of Europe.

We at Manning celebrate the inventiveness, the initiative, and the fun of the computer business with book covers based on costumes from two centuries ago, brought back to life by illustrations such as this one.

The one constant in the field of software development is that we as software developers sit in the middle of a sea of chaos and change. We all feel the churn as new technologies and approaches appear suddenly on the scene, causing us to reevaluate how we build and deliver solutions for our customers. One example of this churn is the rapid adoption by many organizations of building applications using microservices. Microservices are distributed, loosely coupled software services that carry out a small number of well-defined tasks.

This book introduces you to the microservice architecture and why you should consider building your applications with them. We’re going to look at how to build microservices using Java and two Spring framework projects: Spring Boot and Spring Cloud. If you’re a Java developer, Spring Boot and Spring Cloud will provide an easy migration path from building traditional, monolithic Spring applications to microservice applications that can be deployed to the cloud.

Before the concept of microservices evolved, most web-based applications were built using a monolithic architectural style. In a monolithic architecture, an application is delivered as a single deployable software artifact. All the UI (user interface), business, and database access logic are packaged together into a single application artifact and deployed to an application server.

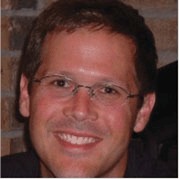

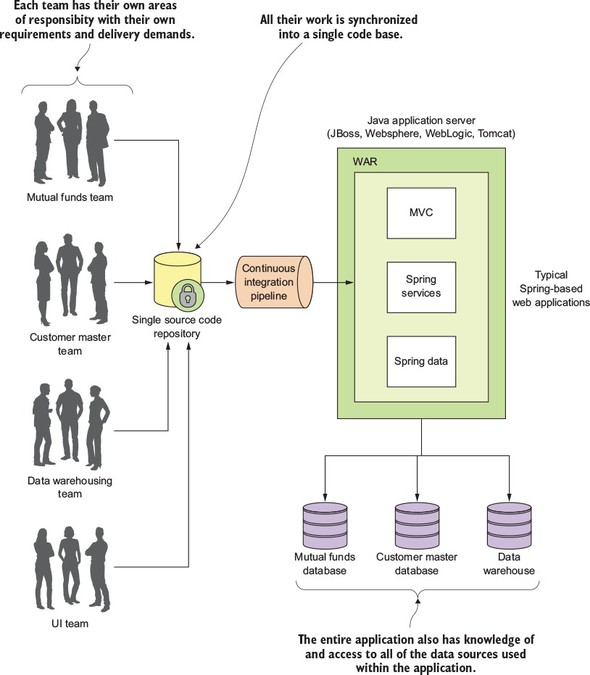

While an application might be a deployed as a single unit of work, most of the time there will be multiple development teams working on the application. Each development team will have their own discrete pieces of the application they’re responsible for and oftentimes specific customers they’re serving with their functional piece. For example, when I worked at a large financial services company, we had an in-house, custom-built customer relations management (CRM) application that involved the coordination of multiple teams including the UI, the customer master, the data warehouse, and the mutual funds team. Figure 1.1 illustrates the basic architecture of this application.

The problem here is that as the size and complexity of the monolithic CRM application grew, the communication and coordination costs of the individual teams working on the application didn’t scale. Every time an individual team needed to make a change, the entire application had to be rebuilt, retested and redeployed.

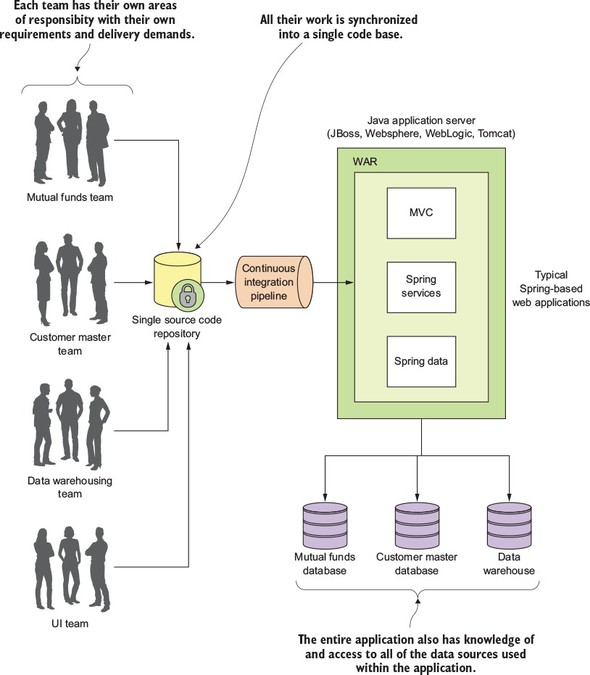

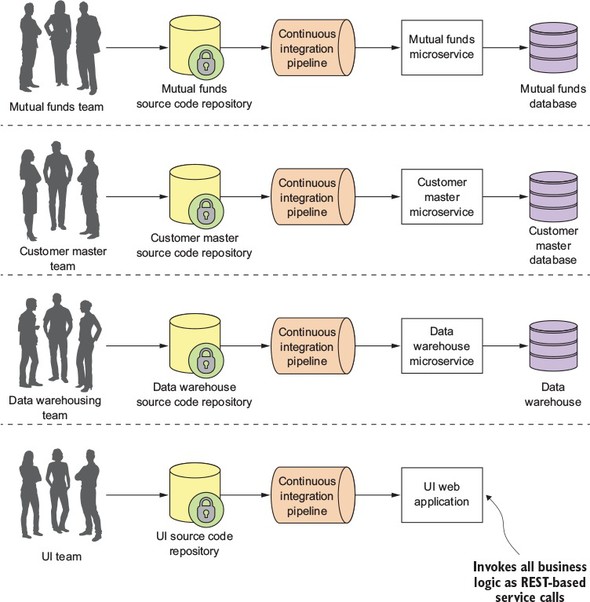

The concept of a microservice originally crept into the software development community’s consciousness around 2014 and was a direct response to many of the challenges of trying to scale both technically and organizationally large, monolithic applications. Remember, a microservice is a small, loosely coupled, distributed service. Microservices allow you to take a large application and decompose it into easy-to--manage components with narrowly defined responsibilities. Microservices help combat the traditional problems of complexity in a large code base by decomposing the large code base down into small, well-defined pieces. The key concept you need to embrace as you think about microservices is decomposing and unbundling the functionality of your applications so they’re completely independent of one another. If we take the CRM application we saw in figure 1.1 and decompose it into microservices, it might look like what’s shown in figure 1.2.

Looking at figure 1.2, you can see that each functional team completely owns their service code and service infrastructure. They can build, deploy, and test independently of each other because their code, source control repository, and the infrastructure (app server and database) are now completely independent of the other parts of the application.

A microservice architecture has the following characteristics:

I often joke with my colleagues that microservices are the gateway drug for building cloud applications. You start building microservices because they give you a high degree of flexibility and autonomy with your development teams, but you and your team quickly find that the small, independent nature of microservices makes them easily deployable to the cloud. Once the services are in the cloud, their small size makes it easy to start up large numbers of instances of the same service, and suddenly your applications become more scalable and, with forethought, more resilient.

Spring has become the de facto development framework for building Java-based applications. At its core, Spring is based on the concept of dependency injection. In a normal Java application, the application is decomposed into classes where each class often has explicit linkages to other classes in the application. The linkages are the invocation of a class constructor directly in the code. Once the code is compiled, these linkage points can’t be changed.

This is problematic in a large project because these external linkages are brittle and making a change can result in multiple downstream impacts to other code. A dependency injection framework, such as Spring, allows you to more easily manage large Java projects by externalizing the relationship between objects within your application through convention (and annotations) rather than those objects having hard-coded knowledge about each other. Spring sits as an intermediary between the different Java classes of your application and manages their dependencies. Spring essentially lets you assemble your code together like a set of Lego bricks that snap together.

Spring’s rapid inclusion of features drove its utility, and the framework quickly became a lighter weight alternative for enterprise application Java developers looking for a way to building applications using the J2EE stack. The J2EE stack, while powerful, was considered by many to be bloatware, with many features that were never used by application development teams. Further, a J2EE application forced you to use a full-blown (and heavy) Java application server to deploy your applications.

What’s amazing about the Spring framework and a testament to its development community is its ability to stay relevant and reinvent itself. The Spring development team quickly saw that many development teams were moving away from monolithic applications where the application’s presentation, business, and data access logic were packaged together and deployed as a single artifact. Instead, teams were moving to highly distributed models where services were being built as small, distributed services that could be easily deployed to the cloud. In response to this shift, the Spring development team launched two projects: Spring Boot and Spring Cloud.

Spring Boot is a re-envisioning of the Spring framework. While it embraces core features of Spring, Spring Boot strips away many of the “enterprise” features found in Spring and instead delivers a framework geared toward Java-based, REST-oriented (Representational State Transfer)[1] microservices. With a few simple annotations, a Java developer can quickly build a REST microservice that can be packaged and deployed without the need for an external application container.

While we cover REST later in chapter 2, it’s worthwhile to read Roy Fielding’s PHD dissertation on building REST-based applications (http://www.ics.uci.edu/~fielding/pubs/dissertation/top.htm). It’s still one of the best explanations of REST available.

While we cover REST in more detail in chapter 2, the core concept behind REST is that your services should embrace the use of the HTTP verbs (GET, POST, PUT, and DELETE) to represent the core actions of the service and use a lightweight web-oriented data serialization protocol, such as JSON, for requesting and receiving data from the service.

Because microservices have become one of the more common architectural patterns for building cloud-based applications, the Spring development community has given us Spring Cloud. The Spring Cloud framework makes it simple to operationalize and deploy microservices to a private or public cloud. Spring Cloud wraps several popular cloud-management microservice frameworks under a common framework and makes the use and deployment of these technologies as easy to use as annotating your code. I cover the different components within Spring Cloud later in this chapter.

This book is about building microservice-based applications using Spring Boot and Spring Cloud that can be deployed to a private cloud run by your company or a public cloud such as Amazon, Google, or Pivotal. With this book, we cover with hands-on examples

By the time you’re done reading this book, you should have the knowledge needed to build and deploy a Spring Boot-based microservice. You’ll also understand the key design decisions need to operationalize your microservices. You’ll understand how service configuration management, service discovery, messaging, logging and tracing, and security all fit together to deliver a robust microservices environment. Finally, you’ll see how your microservices can be deployed within a private or public cloud.

If you’ve gotten this far into reading chapter 1, I suspect that

I chose to write this book for two reasons. First, while I’ve seen many good books on the conceptual aspects of microservices, I couldn’t a find a good Java-based book on implementing microservices. While I’ve always considered myself a programming language polyglot (someone who knows and speaks several languages), Java is my core development language and Spring has been the development framework I “reach” for whenever I build a new application. When I first came across Spring Boot and Spring Cloud, I was blown away. Spring Boot and Spring Cloud greatly simplified my development life when it came to building microservice-based applications running in the cloud.

Second, as I’ve worked throughout my career as both an architect and engineer, I’ve found that many times the technology books that I purchase have tended to go to one of two extremes. They are either conceptual without concrete code examples, or are mechanical overviews of a particular framework or programming language. I wanted a book that would be a good bridge and middle ground between the architecture and engineering disciplines. As you read this book, I want to give you a solid introduction to the microservice patterns development and how they’re used in real-world application development, and then back these patterns up with practical and easy-to-understand code examples using Spring Boot and Spring Cloud.

Let’s shift gears for a moment and walk through building a simple microservice using Spring Boot.

I’ve always had the opinion that a software development framework is well thought out and easy to use if it passes what I affectionately call the “Carnell Monkey Test.” If a monkey like me (the author) can figure out a framework in 10 minutes or less, it has promise. That’s how I felt the first time I wrote a sample Spring Boot service. I want you to have to the same experience and joy, so let’s take a minute to see how to write a simple “Hello World” REST-service using Spring Boot.

In this section, we’re not going to do a detailed walkthrough of much of the code presented. Our goal is to give you a taste of writing a Spring Boot service. We’ll go into much more detail in chapter 2.

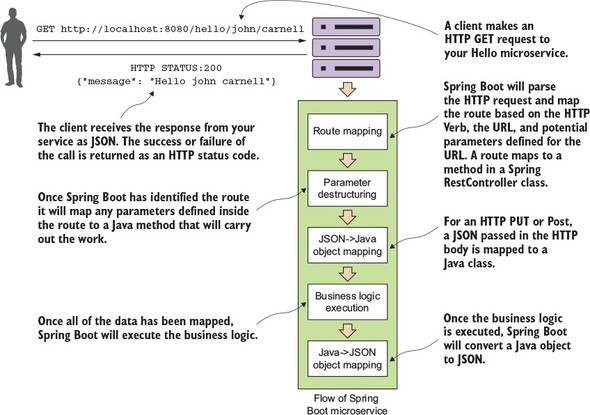

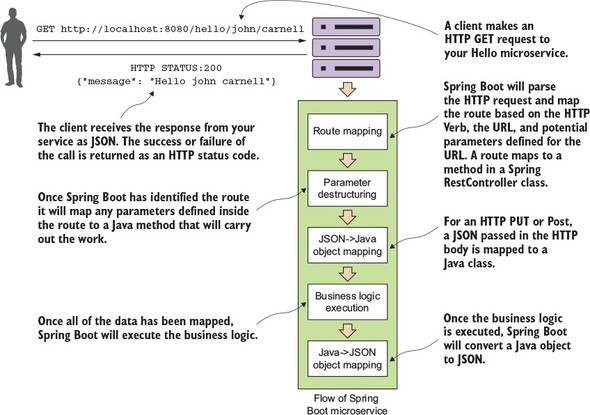

Figure 1.3 shows what your service is going to do and the general flow of how Spring Boot microservice will process a user’s request.

This example is by no means exhaustive or even illustrative of how you should build a production-level microservice, but it should cause you to take a pause because of how little code it took to write it. We’re not going to go through how to set up the project build files or the details of the code until chapter 2. If you’d like to see the Maven pom.xml file and the actual code, you can find it in the chapter 1 section of the downloadable code. All the source code for chapter 1 can be retrieved from the GitHub repository for the book at https://github.com/carnellj/spmia-chapter1.

Please make sure you read appendix A before you try to run the code examples for the chapters in this book. Appendix A covers the general pro-ject layout of all the projects in the book, how to run the build scripts, and how to fire up the Docker environment. The code examples in this chapter are simple and designed to be run natively right from your desktop without the information in additional chapters. However, in later chapters you’ll quickly begin using Docker to run all the services and infrastructure used in this book. Don’t go too far into the book without reading appendix A on setting up your desktop environment.

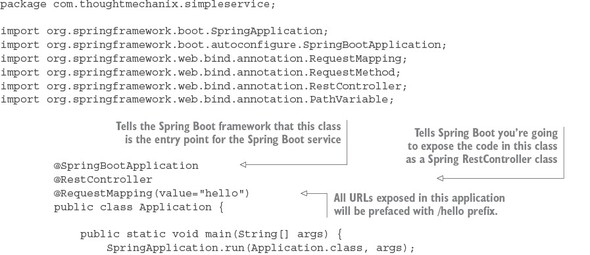

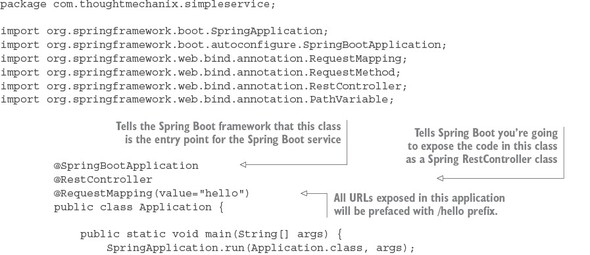

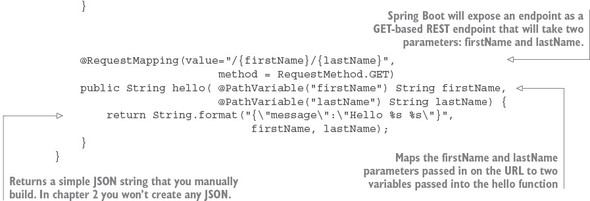

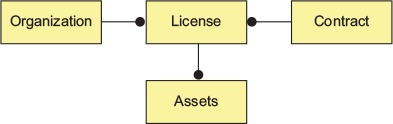

For this example, you’re going to have a single Java class called simpleservice/src/com/thoughtmechanix/application/simpleservice/Application.java that will be used to expose a REST endpoint called /hello.

The following listing shows the code for Application.java.

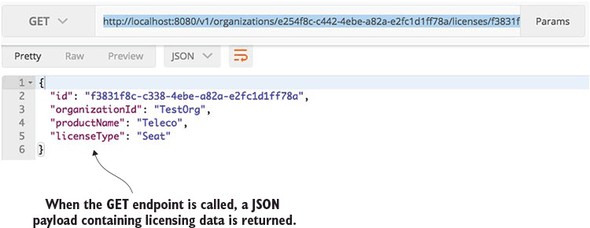

In listing 1.1 you’re basically exposing a single GET HTTP endpoint that will take two parameters (firstName and lastName) on the URL and then return a simple JSON string that has a payload containing the message “Hello firstName lastName”. If you were to call the endpoint /hello/john/carnell on your service (which I’ll show shortly) the return of the call would be

{"message":"Hello john carnell"}

Let’s fire up your service. To do this, go to the command prompt and issue the following command:

mvn spring-boot:run

This command, mvn, will use a Spring Boot plug-in to start the application using an embedded Tomcat server.

The Spring Boot framework has strong support for both Java and the Groovy programming languages. You can build microservices with Groovy and no project setup. Spring Boot also supports both Maven and the Gradle build tools. I’ve limited the examples in this book to Java and Maven. As a long-time Groovy and Gradle aficionado, I have a healthy respect for the language and the build tool, but to keep the book manageable and the material focused, I’ve chosen to go with Java and Maven to reach the largest audience possible.

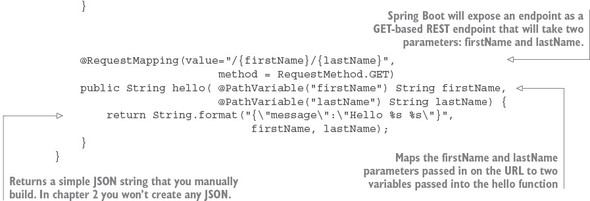

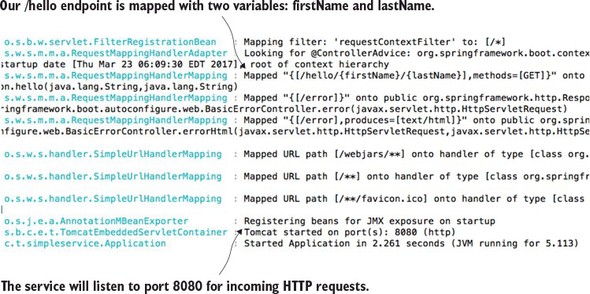

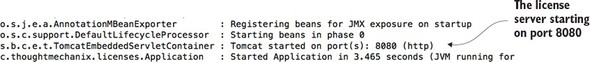

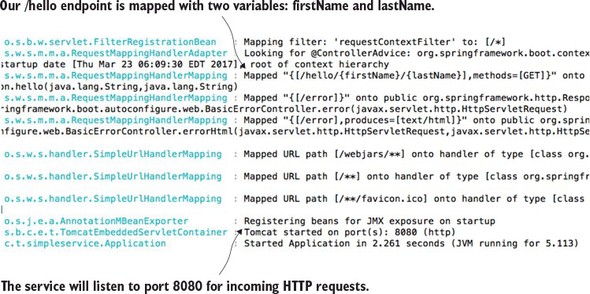

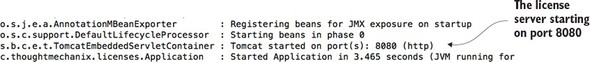

If everything starts correctly, you should see what’s shown in figure 1.4 from your command-line window.

If you examine the screen in figure 1.4, you’ll notice two things. First, a Tomcat server was started on port 8080. Second, a GET endpoint of /hello/{firstName}/{lastName} is exposed on the server.

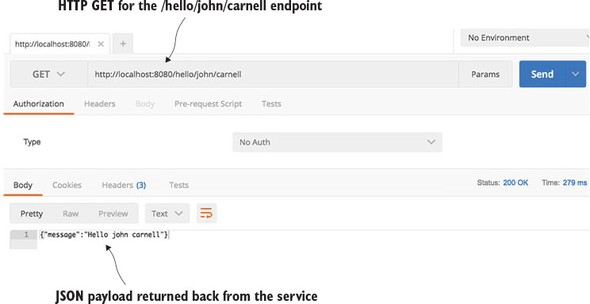

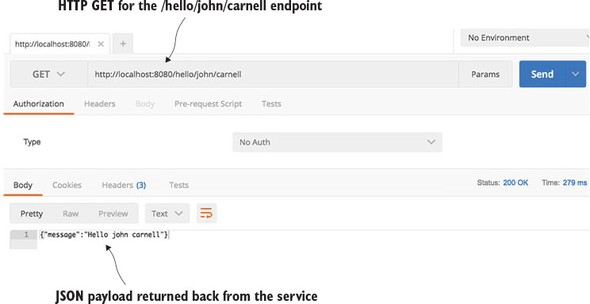

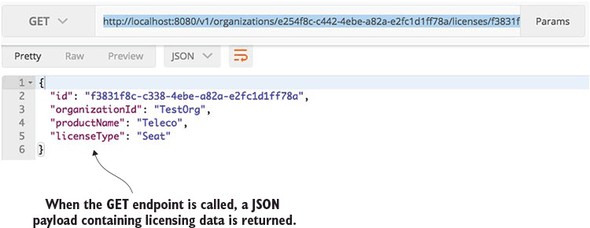

You’re going to call your service using a browser-based REST tool called POSTMAN (https://www.getpostman.com/). Many tools, both graphical and command line, are available for invoking a REST-based service, but I’ll use POSTMAN for all my examples in this book. Figure 1.5 shows the POSTMAN call to the http://localhost:8080/hello/john/carnell endpoint and the results returned from the service.

Obviously, this simple example doesn’t demonstrate the full power of Spring Boot. But what it should show is that you can write a full HTTP JSON REST-based service with route-mapping of URL and parameters in Java with as few as 25 lines of code. As any experienced Java developer will tell you, writing anything meaningful in 25 lines of code in Java is extremely difficult. Java, while being a powerful language, has acquired a reputation of being wordy compared to other languages.

We’re done with our brief tour of Spring Boot. We now have to ask this question: because we can write our applications using a microservice approach, does this mean we should? In the next section, we’ll walk through why and when a microservice approach is justified for building your applications.

We’re at an inflection point in history. Almost all aspects of modern society are now wired together via the internet. Companies that used to serve local markets are suddenly finding that they can reach out to a global customer base. However, with a larger global customer base also comes global competition. These competitive pressures mean the following forces are impacting the way developers have to think about building applications:

To meet these expectations, we, as application developers, have to embrace the paradox that to build high-scalable and highly redundant applications we need to break our applications into small services that can be built and deployed independently of one another. If we “unbundle” our applications into small services and move them away from a single monolithic artifact, we can build systems that are

To this end, as we begin our discussion of microservices keep the following in mind:

Small, Simple, and Decoupled Services = Scalable, Resilient, and Flexible Applications

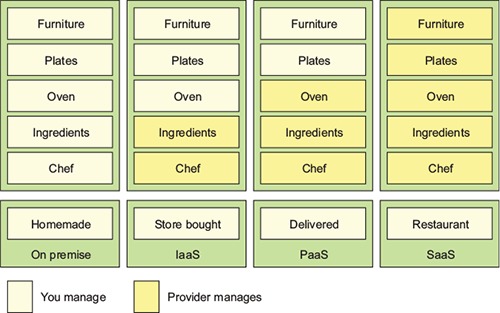

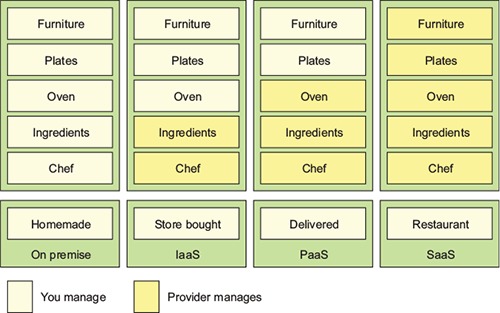

The term “cloud” has become overused. Every software vendor has a cloud and everyone’s platform is cloud-enabled, but if you cut through the hype, three basic models exist in cloud-based computing. These are

To better understand these concepts, let’s map the everyday task of making a meal to the different models of cloud computing. When you want to eat a meal, you have four choices:

Figure 1.6 shows each model.

The difference between these options is about who’s responsible for cooking these meals and where the meal is going to be cooked. In the on-premise model, eating a meal at home requires you to do all the work, using your own oven and ingredients already in the home. A store-bought meal is like using the Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) model of computing. You’re using the store’s chef and oven to pre-bake the meal, but you’re still responsible for heating the meal and eating it at the house (and cleaning up the dishes afterward).

In a Platform as a Service (PaaS) model you still have responsibility for the meal, but you further rely on a vendor to take care of the core tasks associated with making a meal. For example, in a PaaS model, you supply the plates and furniture, but the restaurant owner provides the oven, ingredients, and the chef to cook them. In the Software as a Service (SaaS) model, you go to a restaurant where all the food is prepared for you. You eat at the restaurant and then you pay for the meal when you’re done. you also have no dishes to prepare or wash.

The key items at play in each of these models are ones of control: who’s responsible for maintaining the infrastructure and what are the technology choices available for building the application? In a IaaS model, the cloud vendor provides the basic infrastructure, but you’re accountable for selecting the technology and building the final solution. On the other end of the spectrum, with a SaaS model, you’re a passive consumer of the service provided by the vendor and have no input on the technology selection or any accountability to maintain the infrastructure for the application.

I’ve documented the three core cloud platform types (IaaS, PaaS, SaaS) that are in use today. However, new cloud platform types are emerging. These new platforms include Functions as a Service (FaaS) and Container as a Service (CaaS). FaaS-based (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Function_as_a_Service) applications use technologies like Amazon’s Lambda technologies and Google Cloud functions to build applications deployed as “serverless” chunks of code that run completely on the cloud provider’s platform computing infrastructure. With a FaaS platform, you don’t have to manage any server infrastructure and only pay for the computing cycles required to execute the function.

With the Container as a Service (CaaS) model, developers build and deploy their microservices as portable virtual containers (such as Docker) to a cloud provider. Unlike an IaaS model, where you the developer have to manage the virtual machine the service is deployed to, with CaaS you’re deploying your services in a lightweight virtual container. The cloud provider runs the virtual server the container is running on as well as the provider’s comprehensive tools for building, deploying, monitoring, and scaling containers. Amazon’s Elastic Container Service (ECS) is an example of a CaaS-based platform. In chapter 10 of this book, we’ll see how to deploy the microservices you’ve built to Amazon ECS.

It’s important to note that with both the FaaS and CaaS models of cloud computing, you can still build a microservice-based architecture. Remember, the concept of microservices revolves around building small services, with limited responsibility, using an HTTP-based interface to communicate. The emerging cloud computing platforms, such as FaaS and CaaS, are really about alternative infrastructure mechanisms for deploying microservices.

One of the core concepts of a microservice-based architecture is that each service is packaged and deployed as its own discrete and independent artifact. Service instances should be brought up quickly and each instance of the service should be indistinguishable from another.

As a developer writing a microservice, sooner or later you’re going to have to decide whether your service is going to be deployed to one of the following:

The advantage of cloud-based microservices centers around the concept of elasticity. Cloud service providers allow you to quickly spin up new virtual machines and containers in a matter of minutes. If your capacity needs for your services drop, you can spin down virtual servers without incurring any additional costs. Using a cloud provider to deploy your microservices gives you significantly more horizontal scalability (adding more servers and service instances) for your applications. Server elasticity also means that your applications can be more resilient. If one of your microservices is having problems and is falling over, spinning up new service instances can you keep your application alive long enough for your development team to gracefully resolve the issue.

For this book, all the microservices and corresponding service infrastructure will be deployed to an IaaS-based cloud provider using Docker containers. This is a common deployment topology used for microservices:

Earlier in the chapter we discussed three types of cloud platforms (Infrastructure as a Service, Platform as a Service, and Software as a Services). For this book, I’ve chosen to focus specifically on building microservices using an IaaS-based approach. While certain cloud providers will let you abstract away the deployment infrastructure for your microservice, I’ve chosen to remain vendor-independent and deploy all parts of my application (including the servers).

For instance, Amazon, Cloud Foundry, and Heroku give you the ability to deploy your services without having to know about the underlying application container. They provide a web interface and APIs to allow you to deploy your application as a WAR or JAR file. Setting up and tuning the application server and the corresponding Java container are abstracted away from you. While this is convenient, each cloud provider’s platform has different idiosyncrasies related to its individual PaaS solution.

An IaaS approach, while more work, is portable across multiple cloud providers and allows us to reach a wider audience with our material. Personally, I’ve found that PaaS-based cloud solutions can allow you to quickly jump start your development effort, but once your application reaches enough microservices, you start to need the flexibility the IaaS style of cloud development provides.

Earlier in the chapter, I mentioned new cloud computing platforms such as Function as a Service (FaaS) and Container as a Service (CaaS). If you’re not careful, FaaS-based platforms can lock your code into a cloud vendor platform because your code is deployed to a vendor-specific runtime engine. With a FaaS-based model, you might be writing your service using a general programming language (Java, Python, JavaScript, and so on), but you’re still tying yourself heavily to the underlying vendor APIs and runtime engine that your function will be deployed to.

The services built in this book are packaged as Docker containers. One of the reasons why I chose Docker is that as a container technology, Docker is deployable to all the major cloud providers. Later in chapter 10, I demonstrate how to package microservices using Docker and then deploy these containers to Amazon’s cloud platform.

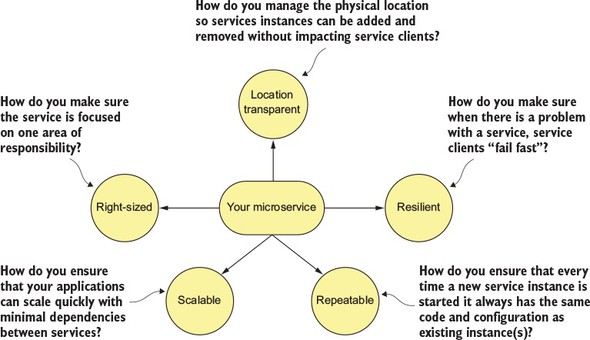

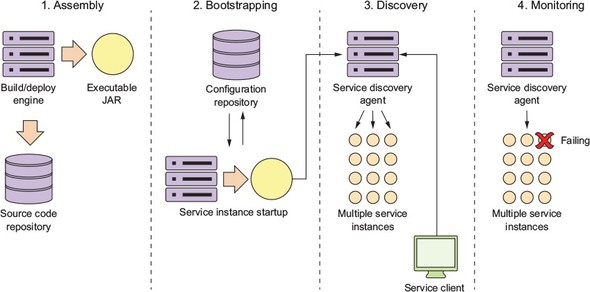

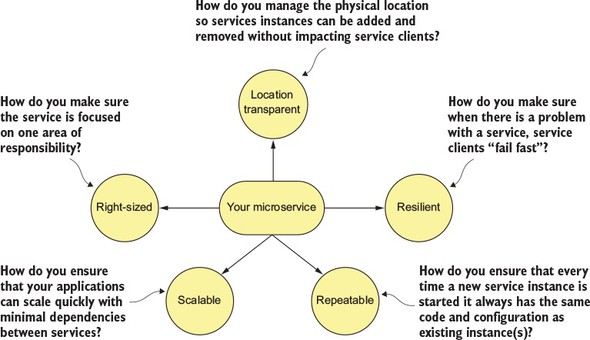

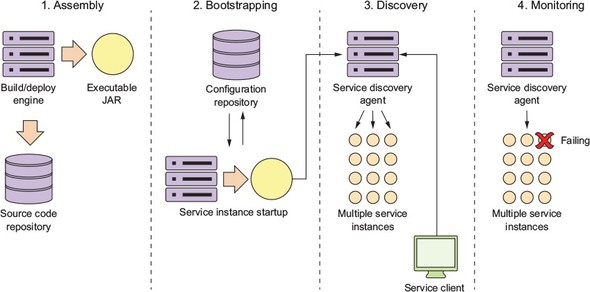

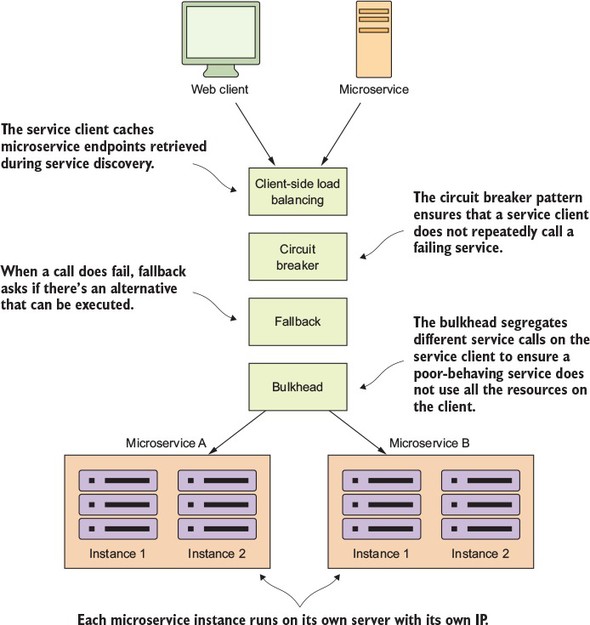

While the concepts around building individual microservices are easy to understand, running and supporting a robust microservice application (especially when running in the cloud) involves more than writing the code for the service. Writing a robust service includes considering several topics. Figure 1.7 highlights these topics.

Let’s walk through the items in figure 1.7 in more detail:

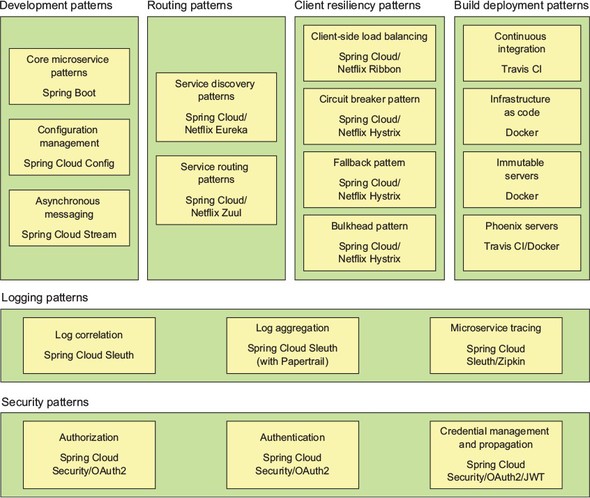

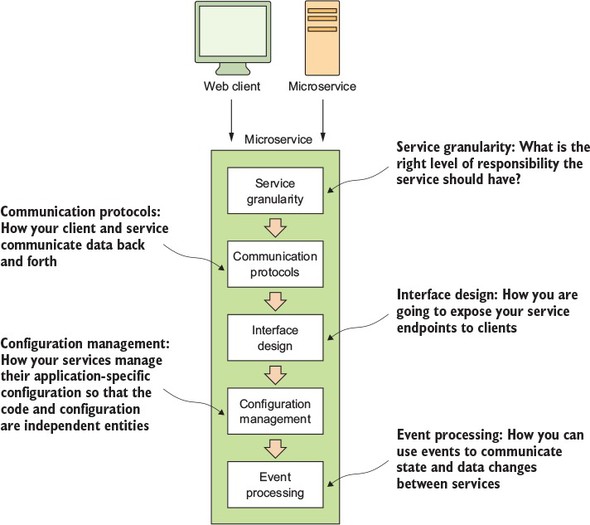

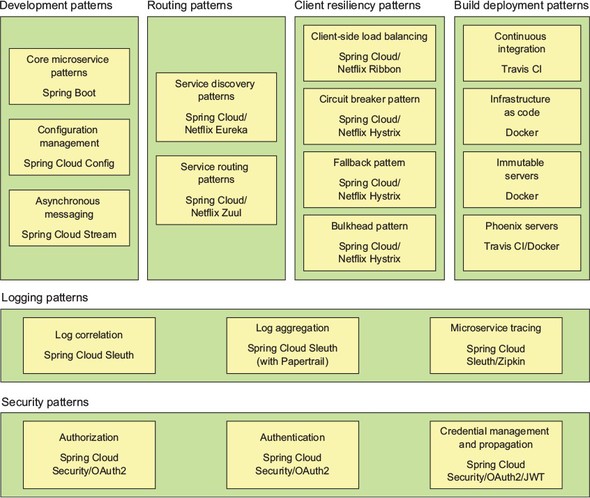

This book takes a patterns-based approach as we answer these questions. With a patterns-based approach, we lay out common designs that can be used across different technology implementations. While we’ve chosen to use Spring Boot and Spring Cloud to implement the patterns we’re going to use in this book, nothing will keep you from taking the concepts presented here and using them with other technology platforms. Specifically, we cover the following six categories of microservice patterns:

Let’s walk through these patterns in more detail.

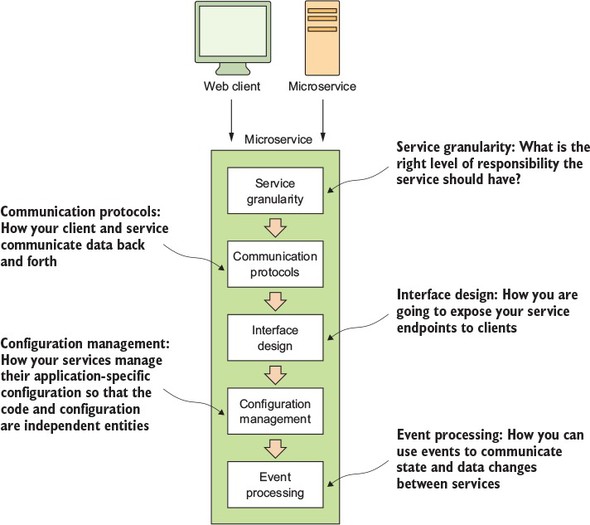

The core development microservice development pattern addresses the basics of building a microservice. Figure 1.8 highlights the topics we’ll cover around basic service design.

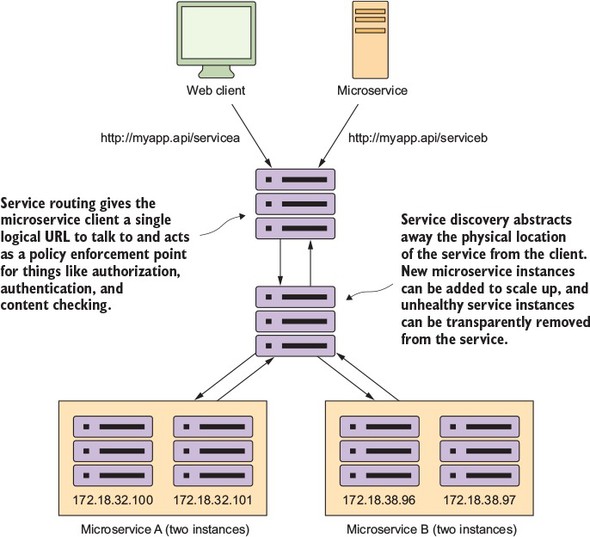

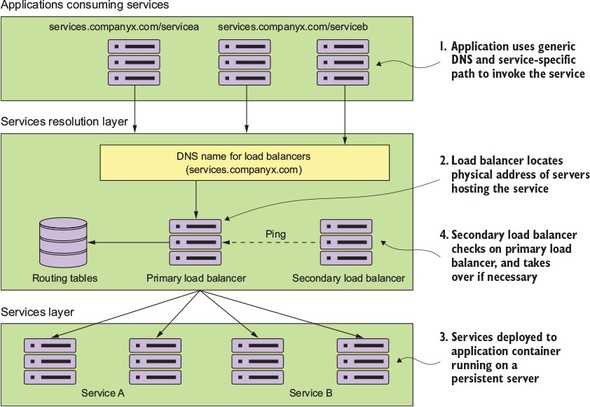

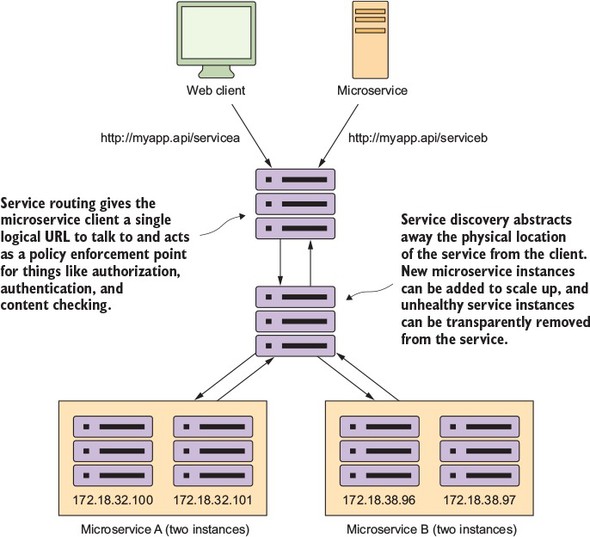

The microservice routing patterns deal with how a client application that wants to consume a microservice discovers the location of the service and is routed over to it. In a cloud-based application, you might have hundreds of microservice instances running. You’ll need to abstract away the physical IP address of these services and have a single point of entry for service calls so that you can consistently enforce security and content policies for all service calls.

Service discovery and routing answer the question, “How do I get my client’s request for a service to a specific instance of a service?”

In figure 1.9, service discovery and service routing appear to have a hard-coded sequence of events between them (first comes service routing and the service discovery). However, the two patterns aren’t dependent on one another. For instance, we can implement service discovery without service routing. You can implement service routing without service discovery (even though its implementation is more difficult).

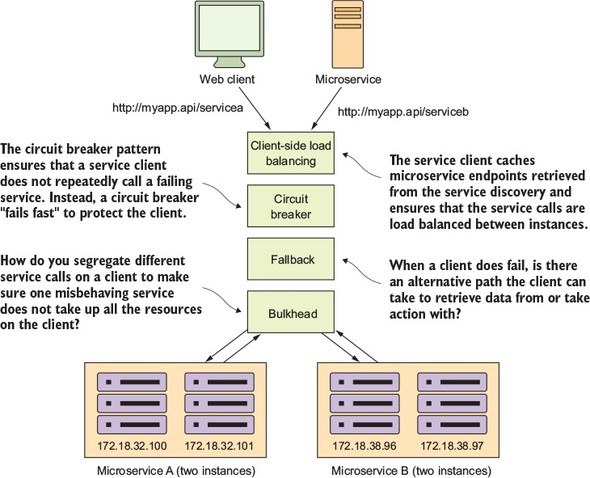

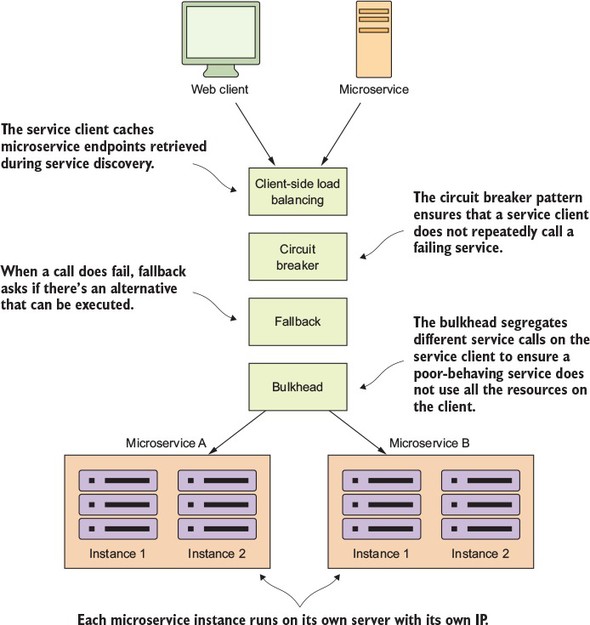

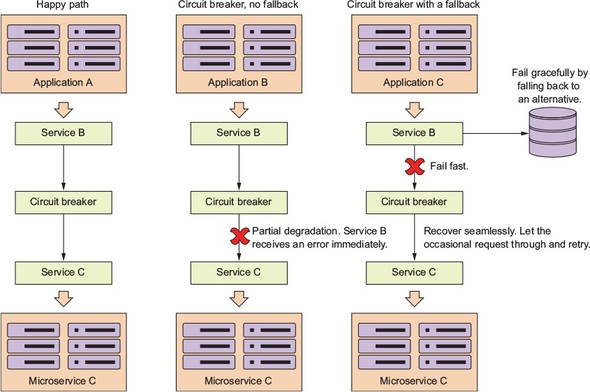

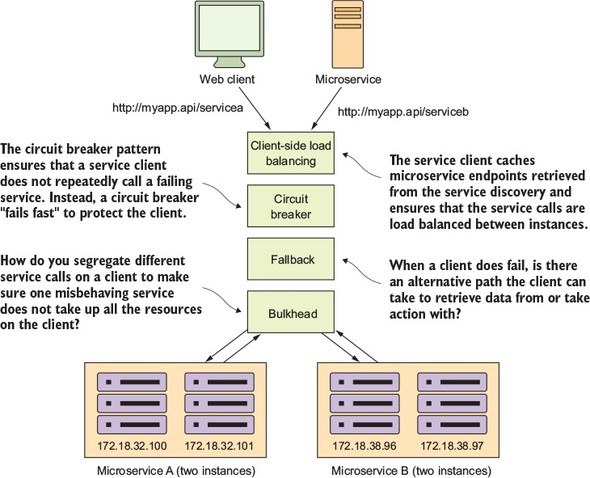

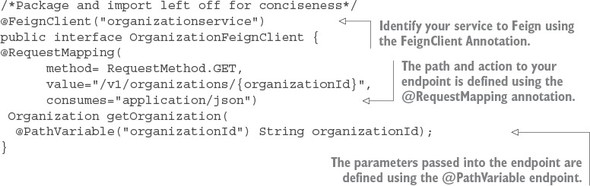

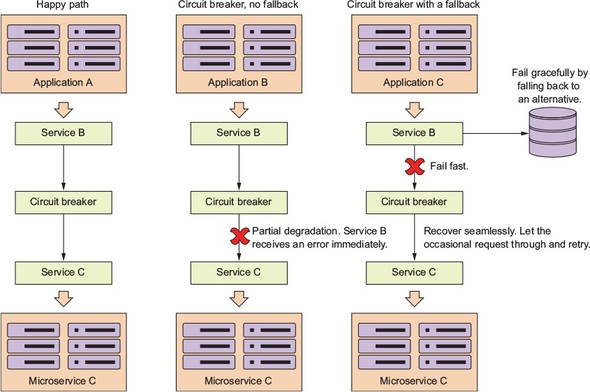

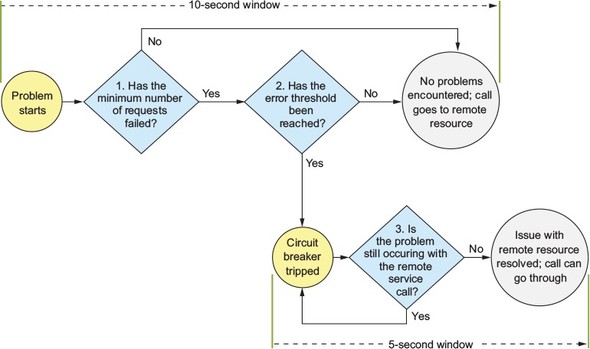

Because microservice architectures are highly distributed, you have to be extremely sensitive in how you prevent a problem in a single service (or service instance) from cascading up and out to the consumers of the service. To this end, we’ll cover four client resiliency patterns:

Figure 1.10 shows how these patterns protect the consumer of service from being impacted when a service is misbehaving. I cover these four topics in chapter 5.

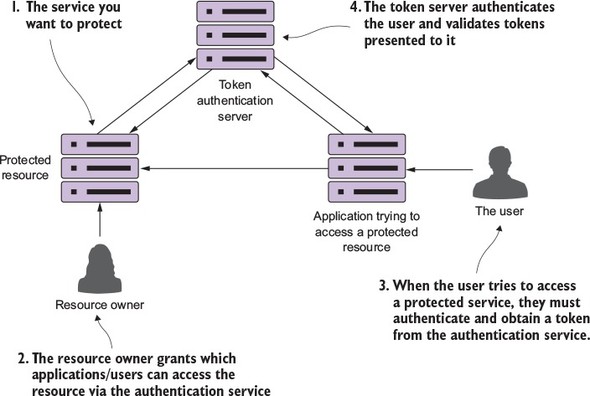

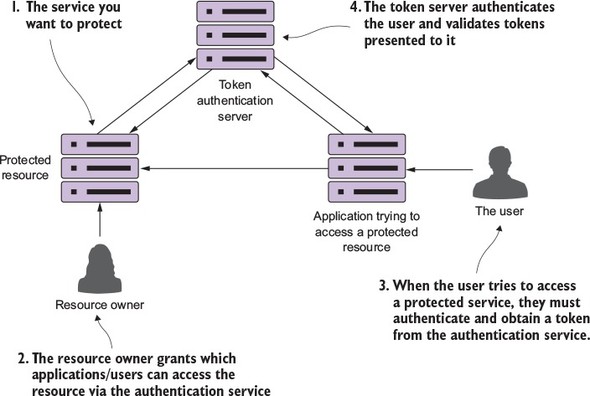

I can’t write a book on microservices without talking about microservice security. In chapter 7 we’ll cover three basic security patterns. These patterns are

Figure 1.11 shows how you can implement the three patterns described previously to build an authentication service that can protect your microservices.

At this point I’m not going to go too deeply into the details of figure 1.10. There’s a reason why security requires a whole chapter. (It could honestly be a book in itself.)

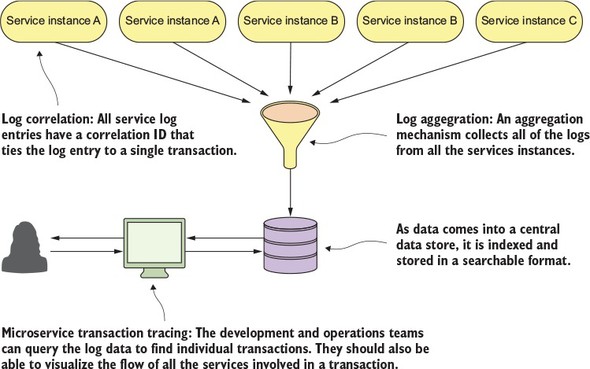

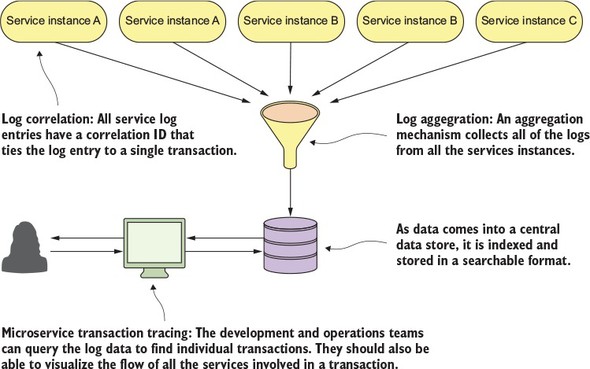

The beauty of the microservice architecture is that a monolithic application is broken down into small pieces of functionality that can be deployed independently of one another. The downside of a microservice architecture is that it’s much more difficult to debug and trace what the heck is going on within your application and services.

For this reason, we’ll look at three core logging and tracing patterns:

Figure 1.12 shows how these patterns fit together. We’ll cover the logging and tracing patterns in greater detail in chapter 9.

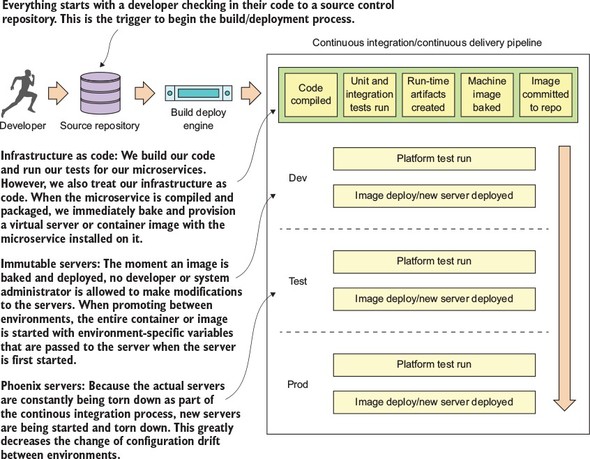

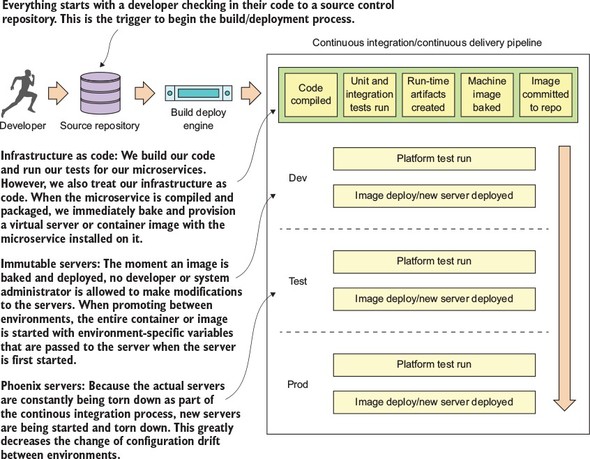

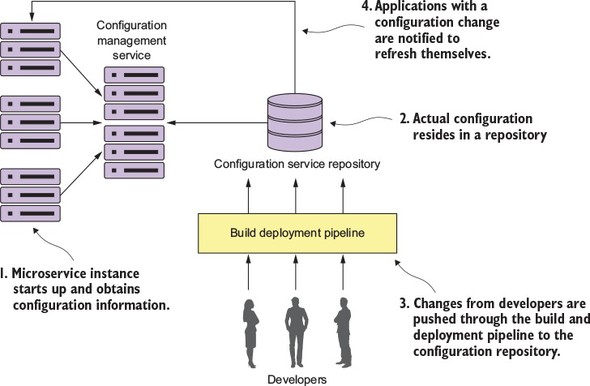

One of the core parts of a microservice architecture is that each instance of a microservice should be identical to all its other instances. You can’t allow “configuration drift” (something changes on a server after it’s been deployed) to occur, because this can introduce instability in your applications.

“I made only one small change on the stage server, but I forgot to make the change in production.” The resolution of many down systems when I’ve worked on critical situations teams over the years has often started with those words from a developer or system administrator. Engineers (and most people in general) operate with good intentions. They don’t go to work to make mistakes or bring down systems. Instead they’re doing the best they can, but they get busy or distracted. They tweak something on a server, fully intending to go back and do it in all the environments.

At a later point, an outage occurs and everyone is left scratching their heads wondering what’s different between the lower environments in production. I’ve found that the small size and limited scope of a microservice makes it the perfect opportunity to introduce the concept of “immutable infrastructure” into an organization: once a service is deployed, the infrastructure it’s running on is never touched again by human hands.

An immutable infrastructure is a critical piece of successfully using a microservice architecture, because you have to guarantee in production that every microservice instance you start for a particular microservice is identical to its brethren.

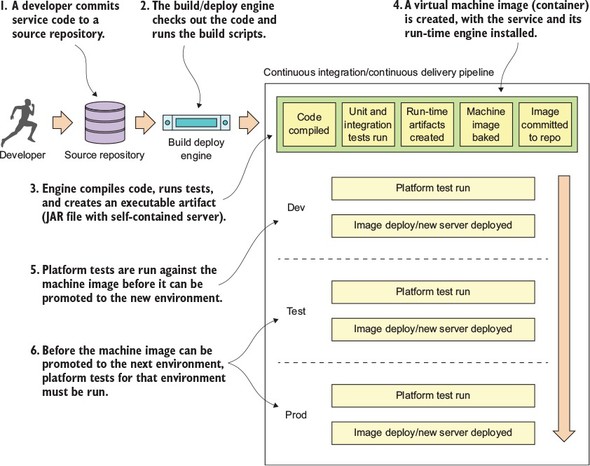

To this end, our goal is to integrate the configuration of your infrastructure right into your build-deployment process so that you no longer deploy software artifacts such as a Java WAR or EAR to an already-running piece of infrastructure. Instead, you want to build and compile your microservice and the virtual server image it’s running on as part of the build process. Then, when your microservice gets deployed, the entire machine image with the server running on it gets deployed.

Figure 1.13 illustrates this process. At the end of the book we’ll look at how to change your build and deployment pipeline so that your microservices and the servers they run on are deployed as a single unit of work. In chapter 10 we cover the following patterns and topics:

Our goal with these patterns and topics is to ruthlessly expose and stamp out configuration drift as quickly as possible before it can hit your upper environments, such as stage or production.

For the code examples in this book (except chapter 10), everything will run locally on your desktop machine. The first two chapters can be run natively directly from the command line. Starting in chapter 3, all the code will be compiled and run as Docker containers.

In this section, I briefly introduce the Spring Cloud technologies that you’ll use as you build out your microservices. This is a high-level overview; when you use each technology in this book, I’ll teach you the details on each as needed.

Implementing all these patterns from scratch would be a tremendous amount of work. Fortunately for us, the Spring team has integrated a wide number of battle-tested open source projects into a Spring subproject collectively known as Spring Cloud. (http://projects.spring.io/spring-cloud/).

Spring Cloud wraps the work of open source companies such as Pivotal, HashiCorp, and Netflix in delivering patterns. Spring Cloud simplifies setting up and configuring of these projects into your Spring application so that you can focus on writing code, not getting buried in the details of configuring all the infrastructure that can go with building and deploying a microservice application.

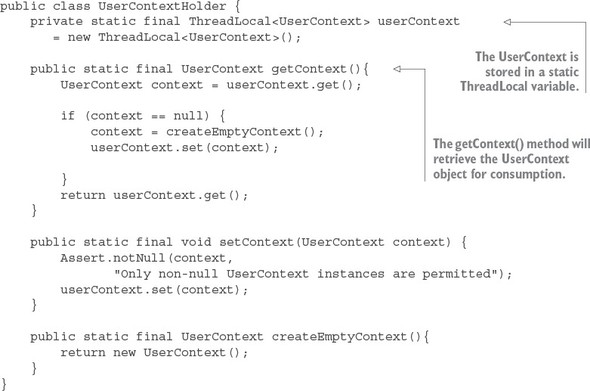

Figure 1.14 maps the patterns listed in the previous section to the Spring Cloud projects that implement them.

Let’s walk through these technologies in greater detail.

Spring Boot is the core technology used in our microservice implementation. Spring Boot greatly simplifies microservice development by simplifying the core tasks of building REST-based microservices. Spring Boot also greatly simplifies mapping HTTP-style verbs (GET, PUT, POST, and DELETE) to URLs and the serialization of the JSON protocol to and from Java objects, as well as the mapping of Java exceptions back to standard HTTP error codes.

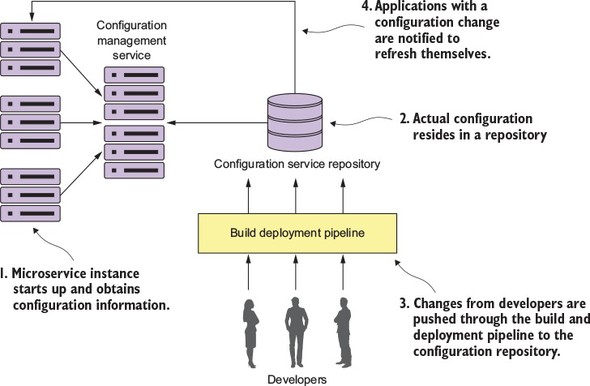

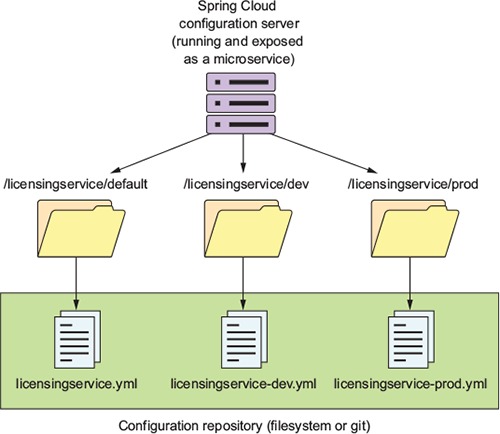

Spring Cloud Config handles the management of application configuration data through a centralized service so your application configuration data (particularly your environment specific configuration data) is cleanly separated from your deployed microservice. This ensures that no matter how many microservice instances you bring up, they’ll always have the same configuration. Spring Cloud Config has its own property management repository, but also integrates with open source projects such as the following:

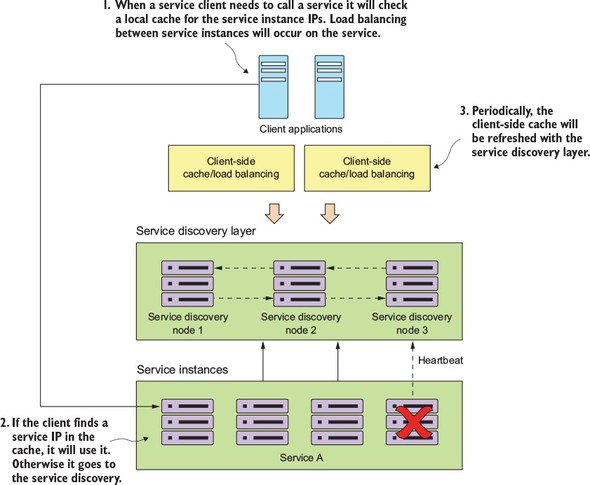

With Spring Cloud service discovery, you can abstract away the physical location (IP and/or server name) of where your servers are deployed from the clients consuming the service. Service consumers invoke business logic for the servers through a logical name rather than a physical location. Spring Cloud service discovery also handles the registration and deregistration of services instances as they’re started up and shut down. Spring Cloud service discovery can be implemented using Consul (https://www.consul.io/) and Eureka (https://github.com/Netflix/eureka) as its service discovery engine.

Spring Cloud heavily integrates with Netflix open source projects. For microservice client resiliency patterns, Spring Cloud wraps the Netflix Hystrix libraries (https://github.com/Netflix/Hystrix) and Ribbon project (https://github.com/Netflix/Ribbon) and makes using them from within your own microservices trivial to implement.

Using the Netflix Hystrix libraries, you can quickly implement service client resiliency patterns such as the circuit breaker and bulkhead patterns.

While the Netflix Ribbon project simplifies integrating with service discovery agents such as Eureka, it also provides client-side load-balancing of service calls from a service consumer. This makes it possible for a client to continue making service calls even if the service discovery agent is temporarily unavailable.

Spring Cloud uses the Netflix Zuul project (https://github.com/Netflix/zuul) to provide service routing capabilities for your microservice application. Zuul is a service gateway that proxies service requests and makes sure that all calls to your microservices go through a single “front door” before the targeted service is invoked. With this centralization of service calls, you can enforce standard service policies such as a security authorization authentication, content filtering, and routing rules.

Spring Cloud Stream (https://cloud.spring.io/spring-cloud-stream/) is an enabling technology that allows you to easily integrate lightweight message processing into your microservice. Using Spring Cloud Stream, you can build intelligent microservices that can use asynchronous events as they occur in your application. With Spring Cloud Stream, you can quickly integrate your microservices with message brokers such as RabbitMQ (https://www.rabbitmq.com/) and Kafka (http://kafka.apache.org/).

Spring Cloud Sleuth (https://cloud.spring.io/spring-cloud-sleuth/) allows you to integrate unique tracking identifiers into the HTTP calls and message channels (RabbitMQ, Apache Kafka) being used within your application. These tracking numbers, sometimes referred to as correlation or trace ids, allow you to track a transaction as it flows across the different services in your application. With Spring Cloud Sleuth, these trace IDs are automatically added to any logging statements you make in your microservice.

The real beauty of Spring Cloud Sleuth is seen when it’s combined with logging aggregation technology tools such as Papertrail (http://papertrailapp.com) and tracing tools such as Zipkin (http://zipkin.io). Papertail is a cloud-based logging platform used to aggregate logs in real time from different microservices into one queryable database. Open Zipkin takes data produced by Spring Cloud Sleuth and allows you to visualize the flow of your service calls involved for a single transaction.

Spring Cloud Security (https://cloud.spring.io/spring-cloud-security/) is an authentication and authorization framework that can control who can access your services and what they can do with your services. Spring Cloud Security is token-based and allows services to communicate with one another through a token issued by an authentication server. Each service receiving a call can check the provided token in the HTTP call to validate the user’s identity and their access rights with the service.

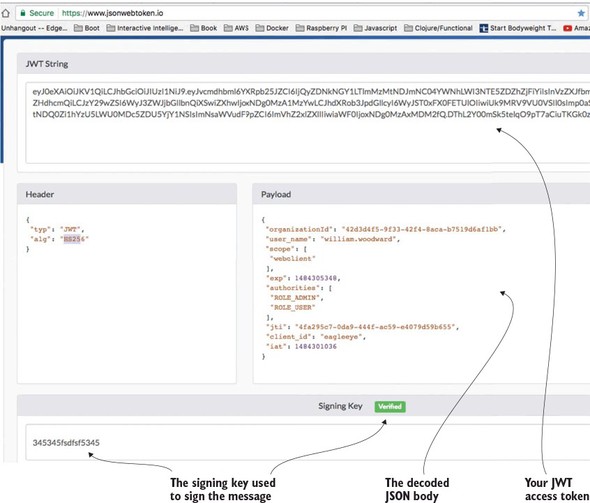

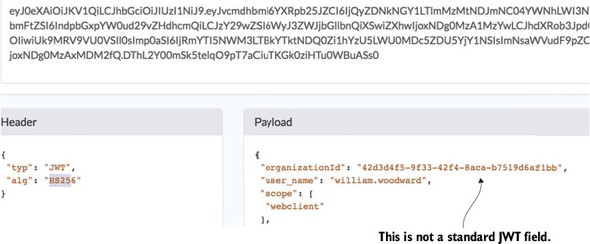

In addition, Spring Cloud Security supports the JavaScript Web Token (https://jwt.io). The JavaScript Web Token (JWT) framework standardizes the format of how a OAuth2 token is created and provides standards for digitally signing a created token.

For the provisioning implementations, we’re going to make a technology shift. The Spring framework(s) are geared toward application development. The Spring frameworks (including Spring Cloud) don’t have tools for creating a “build and deployment” pipeline. To implement a “build and deployment” pipeline you’re going to use the following tools: Travis CI (https://travis-ci.org) for your build tool and Docker (https://www.docker.com/) to build the final server image containing your microservice.

To deploy your built Docker containers, we end the book with an example of how to deploy the entire application stack built throughout this book to Amazon’s cloud.

In the last section, we walked through all the different Spring Cloud technologies that you’re going to use as you build out your microservices. Because each of these technologies are independent services, it’s obviously going to take more than one chapter to explain all of them in detail. However, as I wrap up this chapter, I want to leave you with a small code example that again demonstrates how easy it is to integrate these technologies into your own microservice development effort.

Unlike the first code example in listing 1.1, you can’t run this code example because a number of supporting services need to be set up and configured to be used. Don’t worry, though; the setup costs for these Spring Cloud services (configuration service, service discovery) are a one-time cost in terms of setting up the service. Once they’re set up, your individual microservices can use these capabilities over and over again. We couldn’t fit all that goodness into a single code example at the beginning of the book.

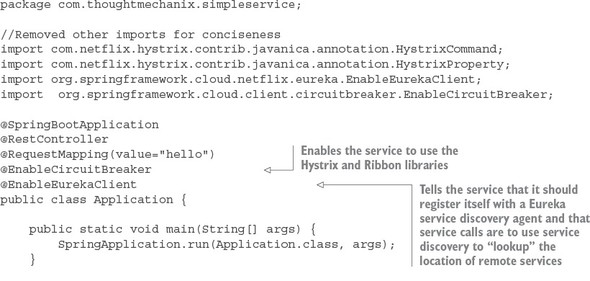

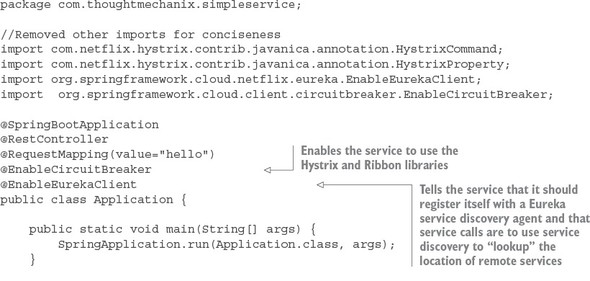

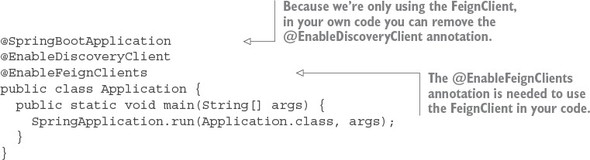

The code shown in the following listing quickly demonstrates how the service discovery, circuit breaker, bulkhead, and client-side load balancing of remote services were integrated into our “Hello World” example.

This code has a lot packed into it, so let’s walk through it. Keep in mind that this listing is only an example and isn’t found in the chapter 1 GitHub repository source code. I’ve included it here to give you a taste of what’s to come later in the book.

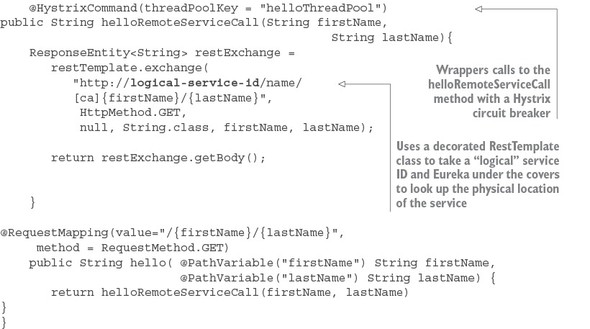

The first thing you should notice is the @EnableCircuitBreaker and @EnableEurekaClient annotations. The @EnableCircuitBreaker annotation tells your Spring microservice that you’re going to use the Netflix Hystrix libraries in your application. The @EnableEurekaClient annotation tells your microservice to register itself with a Eureka Service Discovery agent and that you’re going to use service discovery to look up remote REST services endpoints in your code. Note that configuration is happening in a property file that will tell the simple service the location and port number of a Eureka server to contact. You first see Hystrix being used when you declare your hello method:

@HystrixCommand(threadPoolKey = "helloThreadPool") public String helloRemoteServiceCall(String firstName, String lastName)

The @HystrixCommand annotation is doing two things. First, any time the helloRemoteServiceCall method is called, it won’t be directly invoked. Instead, the method will be delegated to a thread pool managed by Hystrix. If the call takes too long (default is one second), Hystrix steps in and interrupts the call. This is the implementation of the circuit breaker pattern. The second thing this annotation does is create a thread pool called helloThreadPool that’s managed by Hystrix. All calls to helloRemoteServiceCall method will only occur on this thread pool and will be isolated from any other remote service calls being made.

The last thing to note is what’s occurring inside the helloRemoteServiceCall method. The presence of the @EnableEurekaClient has told Spring Boot that you’re going to use a modified RestTemplate class (this isn’t how the Standard Spring RestTemplate would work out of the box) whenever you make a REST service call. This RestTemplate class will allow you to pass in a logical service ID for the service you’re trying to invoke:

ResponseEntity<String> restExchange = restTemplate.exchange (http://logical-service-id/name/{firstName}/{lastName}

Under the covers, the RestTemplate class will contact the Eureka service and look up the physical location of one or more of the “name” service instances. As a consumer of the service, your code never has to know where that service is located.

Also, the RestTemplate class is using Netflix’s Ribbon library. Ribbon will retrieve a list of all the physical endpoints associated with a service. Every time the service is called by the client, it “round-robins” the call to the different service instances on the client without having to go through a centralized load balancer. By eliminating a centralized load balancer and moving it to the client, you eliminate another failure point (load balancer going down) in your application infrastructure.

I hope that at this point you’re impressed, because you’ve added a significant number of capabilities to your microservice with only a few annotations. That’s the real beauty behind Spring Cloud. You as a developer get to take advantage of battle-hardened microservice capabilities from premier cloud companies like Netflix and Consul. These capabilities, if used outside of Spring Cloud, can be complex and obtuse to set up. Spring Cloud simplifies their use to literally nothing more than a few simple Spring Cloud annotations and configuration entries.

I want to make sure this book provides examples that you can relate to as you go about your day-to-day job. To this end, I’ve structured the chapters in this book and the corresponding code examples around the adventures (misadventures) of a fictitious company called ThoughtMechanix.

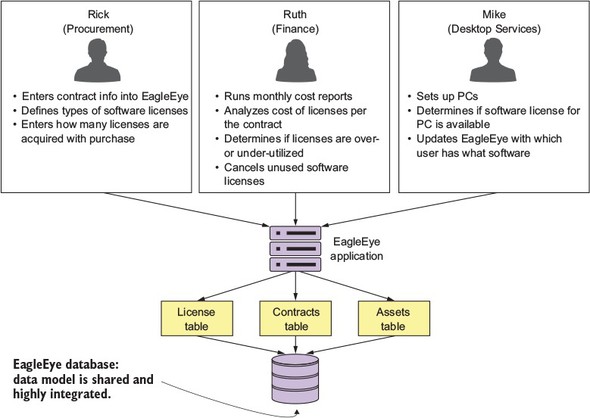

ThoughtMechanix is a software development company whose core product, EagleEye, provides an enterprise-grade software asset management application. It provides coverage for all the critical elements: inventory, software delivery, license management, compliance, cost, and resource management. Its primary goal is to enable organizations to gain an accurate point-in-time picture of its software assets.

The company is approximately 10 years old. While they’ve experienced solid revenue growth, internally they’re debating whether they should be re-platforming their core product from a monolithic on-premise-based application or move their application to the cloud. The re-platforming involved with EagleEye can be a “make or break” moment for a company.

The company is looking at rebuilding their core product EagleEye on a new architecture. While much of the business logic for the application will remain in place, the application itself will be broken down from a monolithic design to a much smaller microservice design whose pieces can be deployed independently to the cloud. The examples in this book won’t build the entire ThoughtMechanix application. Instead you’ll build specific microservices from the problem domain at hand and then build the infrastructure that will support these services using various Spring Cloud (and some non-Spring-Cloud) technologies.

The ability to successfully adopt cloud-based, microservice architecture will impact all parts of a technical organization. This includes the architecture, engineering, testing, and operations teams. Input will be needed from each group and, in the end, they’re probably going to need reorganization as the team reevaluates their responsibilities in this new environment. Let’s start our journey with ThoughtMechanix as you begin the fundamental work of identifying and building out several of the microservices used in EagleEye and then building these services using Spring Boot.

The history of software development is littered with the tales of large development projects that after an investment of millions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of software developer hours, and with many of the best and brightest minds in the industry working on them, somehow never managed to deliver anything of value to their customers and literally collapsed under their own complexity and weight.

These mammoth projects tended to follow large, traditional waterfall development methodologies that insisted that all the application’s requirements and design be defined at the beginning of the project. So much emphasis was placed on getting all the specifications for the software “correct” that there was little leeway to meet new business requirements, or refactor and learn from mistakes made in the early stages of development.

The reality, though, is that software development isn’t a linear process of definition and execution, but rather an evolutionary one where it takes several iterations of communicating with, learning from, and delivering to the customer before the development team truly understands the problem at hand.

Compounding the challenges of using traditional waterfall methodologies is that many times the granularity of the software artifacts being delivered in these projects are

A microservice-based architecture takes a different approach to delivering functionality. Specifically, microservice-based architectures have these characteristics:

Why are these microservice architecture attributes important to cloud-based development? Cloud-based applications in general have the following:

This chapter provides you with the foundation you need to target and identify microservices in your business problem, build the skeleton of a microservice, and then understand the operational attributes that need to be in place for a microservice to be deployed and managed successfully in production.

To successfully design and build microservices, you need to approach microservices as if you’re a police detective interviewing witnesses to a crime. Even though every witness saw the same events take place, their interpretation of the crime is shaped by their background, what was important to them (for example, what motivates them), and what environmental pressures were brought to bear at that moment they witnessed the event. Participants each have their own perspectives (and biases) of what they consider important.

Like a successful police detective trying to get to the truth, the journey to build a successful microservice architecture involves incorporating the perspectives of multiple individuals within your software development organization. Although it takes more than technical people to deliver an entire application, I believe that the foundation for successful microservice development starts with the perspectives of three critical roles:

In this chapter, I’ll demonstrate how to design and build a set of microservices from the perspective of each of these roles using Spring Boot and Java. By the time the chapter concludes, you’ll have a service that can be packaged and deployed to the cloud.

An architect’s role on a software project is to provide a working model of the problem that needs to be solved. The job of the architect is to provide the scaffolding against which developers will build their code so that all the pieces of the application fit together.

When building a microservices architecture, a project’s architect focuses on three key tasks:

In the face of complexity, most people try to break the problem on which they’re working into manageable chunks. They do this so they don’t have to try to fit all the details of the problem in their heads. Instead, they break the problem down abstractly into a few key parts and then look for the relationships that exist between these parts.

In a microservices architecture, the architect breaks the business problem into chunks that represent discrete domains of activity. These chunks encapsulate the business rules and the data logic associated with a particular part of the business domain.

Although you want microservices to encapsulate all the business rules for carrying out a single transaction, this isn’t always feasible. You’ll often have situations where you need to have groups of microservices working across different parts of the business domain to complete an entire transaction. An architect teases apart the service boundaries of a set of microservices by looking at where the data domain doesn’t seem to fit together.

For example, an architect might look at a business flow that’s to be carried out by code and realize that they need both customer and product information. The presence of two discrete data domains is a good indication that multiple microservices are at play. How the two different parts of the business transaction interact usually becomes the service interface for the microservices.

Breaking apart a business domain is an art form rather than a black-and-white science. Use the following guidelines for identifying and decomposing a business problem into microservice candidates:

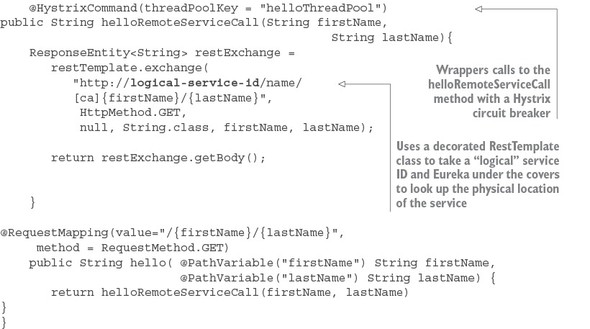

Let’s take these guidelines and apply them to a real-world problem. Chapter 1 introduced an existing software product called EagleEye that’s used for managing software assets such as software licenses and secure socket layer (SSL) certificates. These items are deployed to various servers throughout an organization.

EagleEye is a traditional monolithic web application that’s deployed to a J2EE application server residing within a customer’s data center. Your goal is to tease apart the existing monolithic application into a set of services.

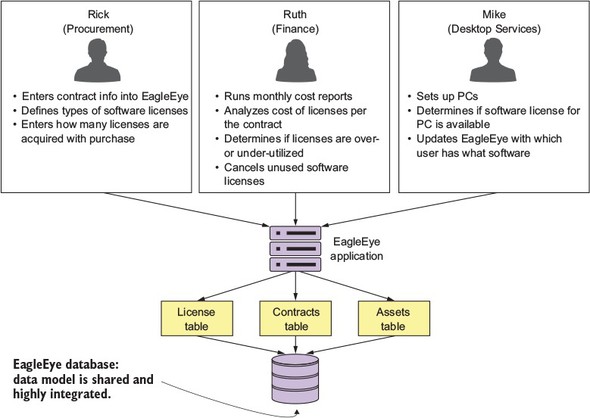

You’re going to start by interviewing all the users of the EagleEye application and discussing with them how they interact and use EagleEye. Figure 2.1 captures a summary of the conversations you might have with the different business customers. By looking at how the users of EagleEye interact with the application and how the data model for the application is broken out, you can decompose the EagleEye problem domain into the following microservice candidates.

In the figure, I’ve highlighted a number of nouns and verbs that have come up during conversations with the business users. Because this is an existing application, you can look at the application and map the major nouns back to tables in the physical data model. An existing application may have hundreds of tables, but each table will usually map back to a single set of logical entities.

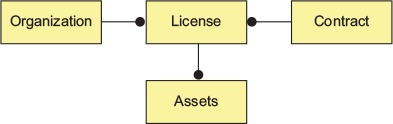

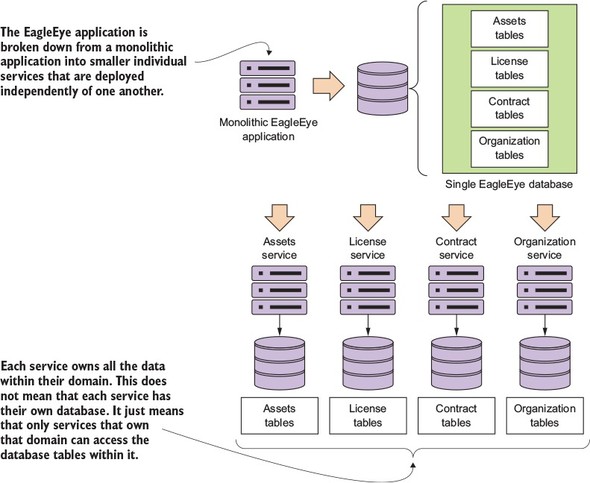

Figure 2.2 shows a simplified data model based on conversations with EagleEye customers. Based on the business interviews and the data model, the microservice candidates are organization, license, contract, and assets services.

Once you have a simplified data model, you can begin the process of defining what microservices you’re going to need in the application. Based on the data model in figure 2.2, you can see the potential for four microservices based on the following elements:

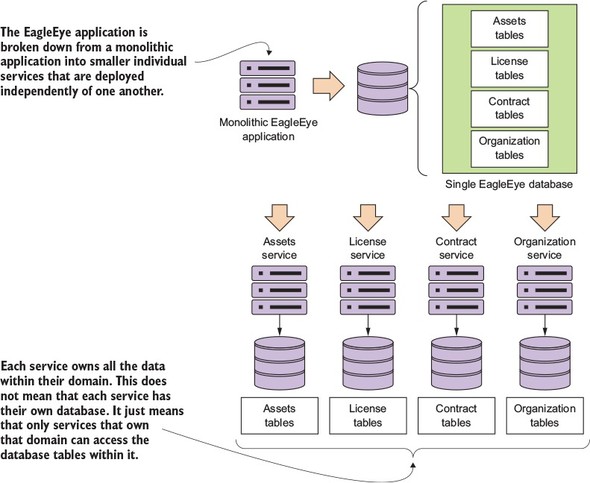

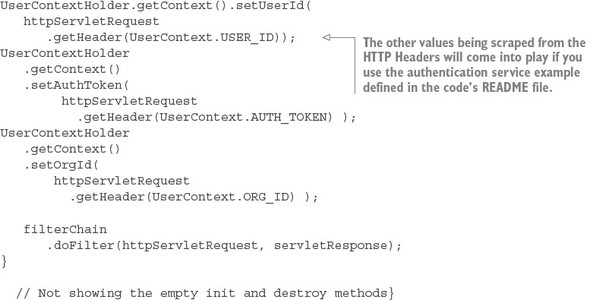

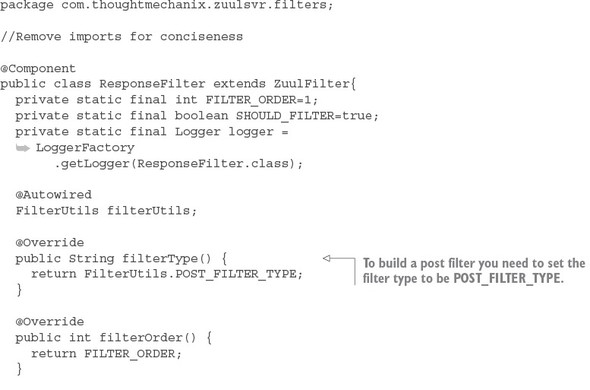

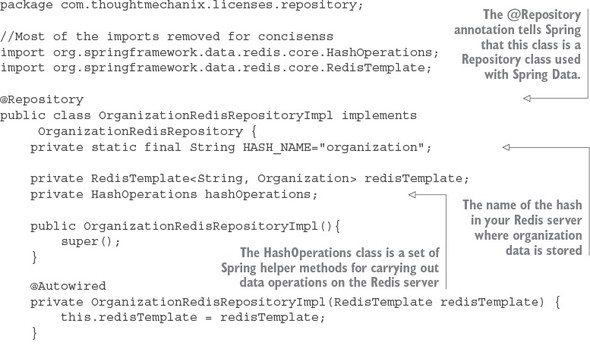

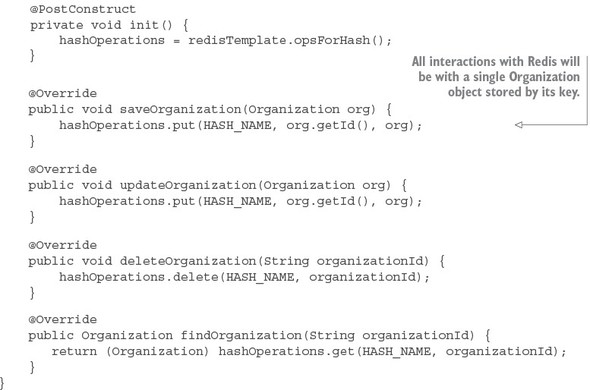

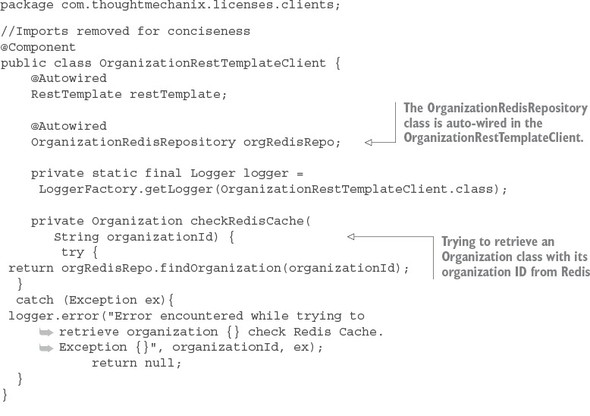

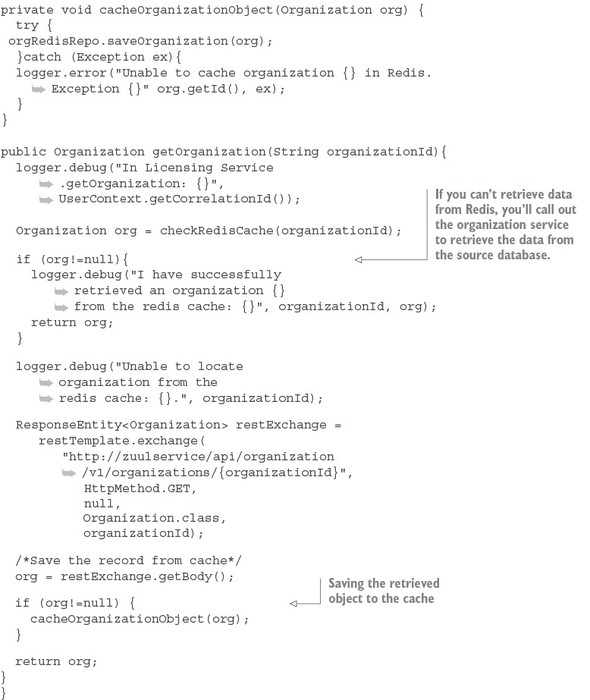

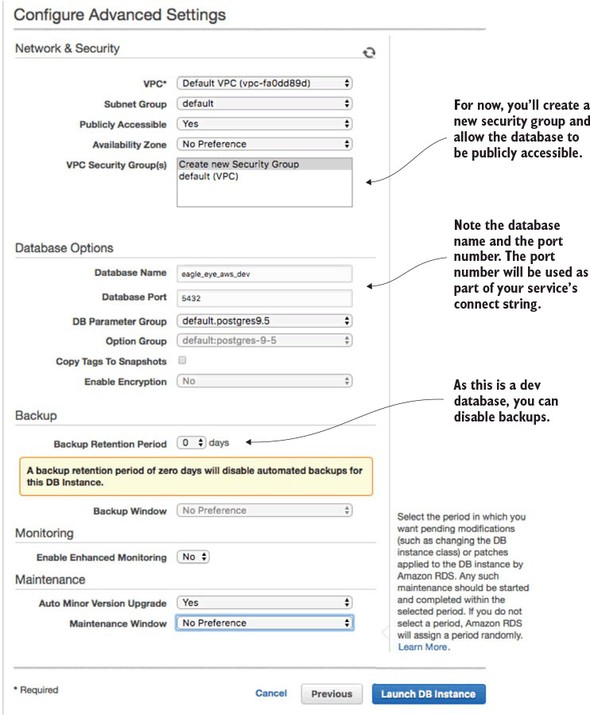

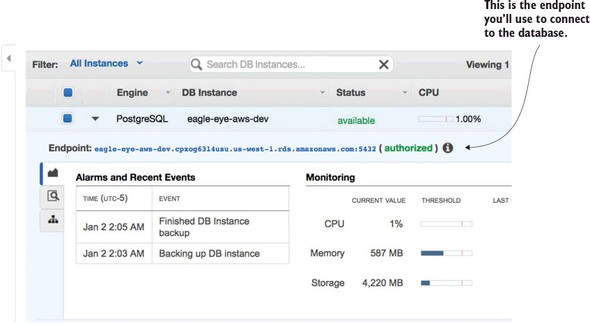

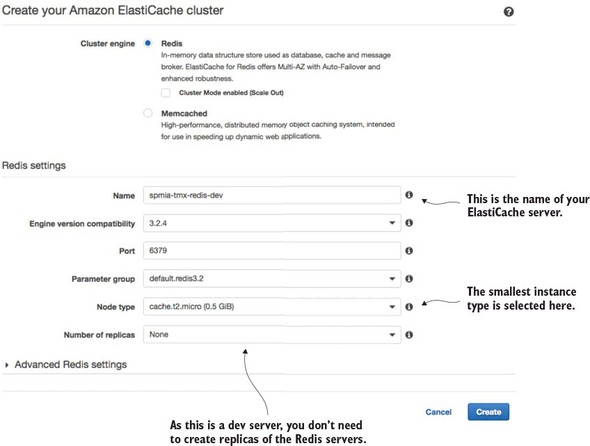

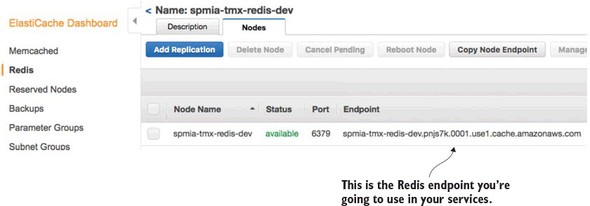

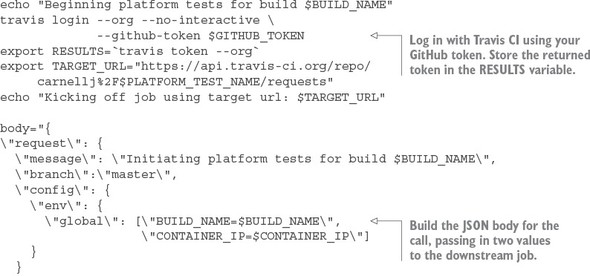

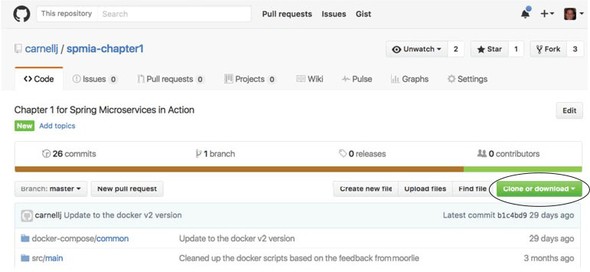

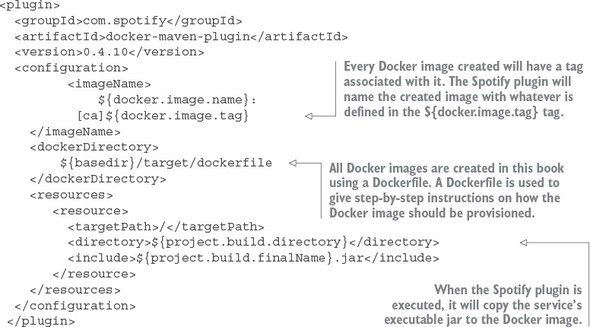

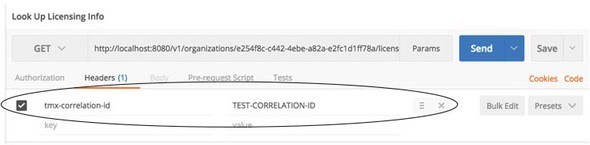

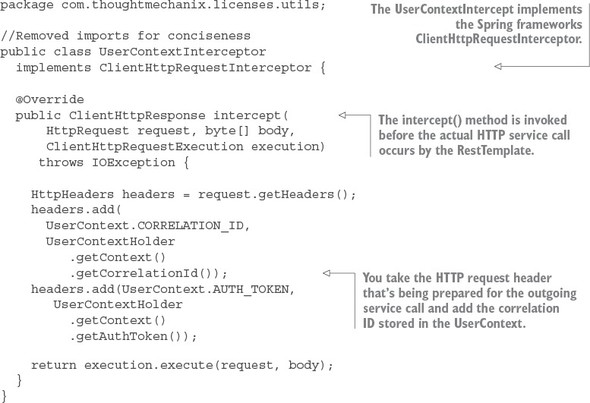

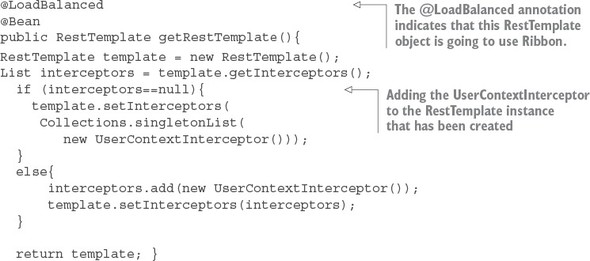

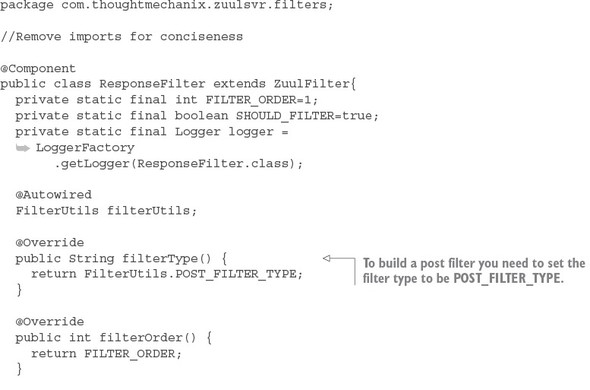

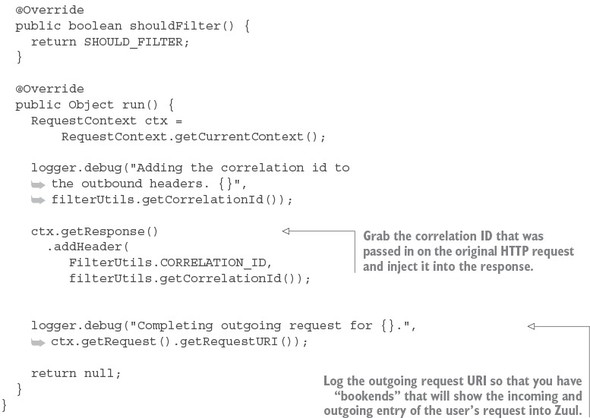

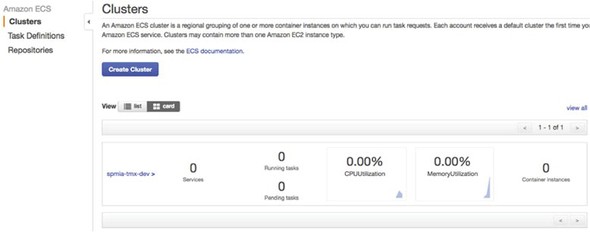

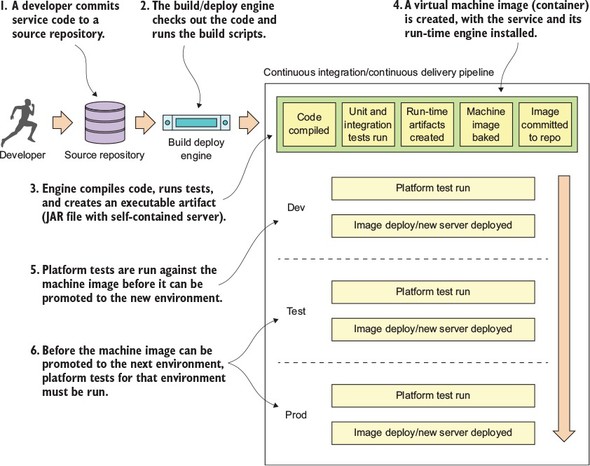

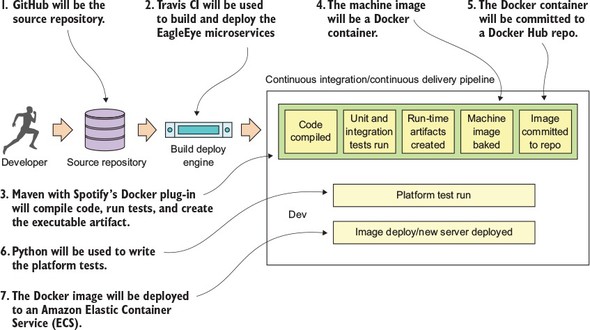

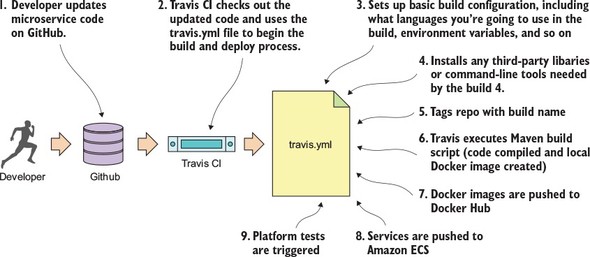

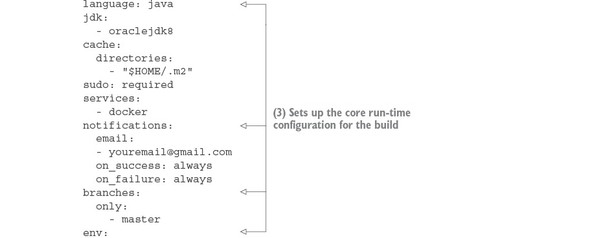

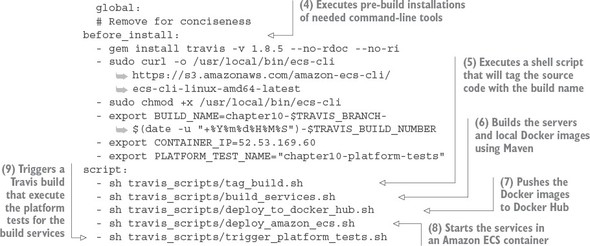

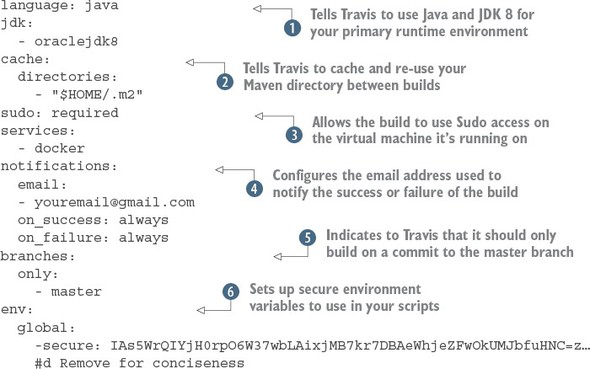

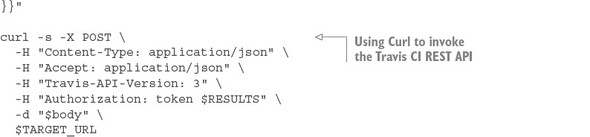

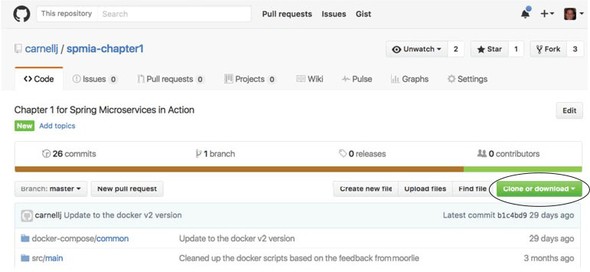

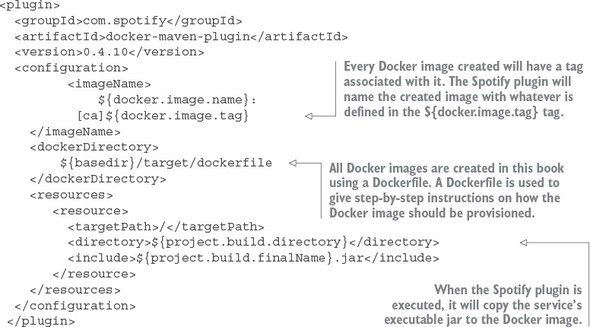

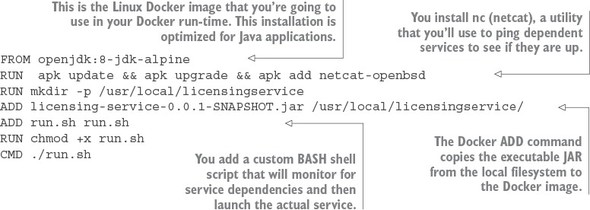

The goal is to take these major pieces of functionality and extract them into completely self-contained units that can be built and deployed independently of each other. But extracting services from the data model involves more than repackaging code into separate projects. It’s also about teasing out the actual database tables the services are accessing and only allowing each individual service to access the tables in its specific domain. Figure 2.3 shows how the application code and the data model become “chunked” into individual pieces.