Chapter 4. Middleware

- Writing middleware functions: a function with three arguments

- Writing and using error-handling middleware: a function with four arguments

- Using open source middleware functions, like Morgan for logging and express.static for serving static files

Without any framework like Express, Node gives you a pretty simple API. Create a function that handles requests, pass it to http.createServer, and call it a day. Although this API is simple, your request handler function can get unwieldy as your app grows.

Express helps to mitigate some of these issues. One of the ways it does this is through the use of something called middleware. Framework-free Node has you writing a single large request handler function for your entire app. Middleware allows you to break these request handler functions into smaller bits. These smaller functions tend to handle one thing at a time. One might log all of the requests that come into your server; another might parse special values of incoming requests; another might authenticate users.

Conceptually, middleware is the biggest part of Express. Most of the Express code you write is middleware in one way or another. Hopefully, after this chapter, you’ll see why!

4.1. Middleware and the middleware stack

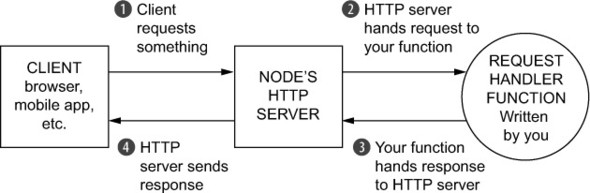

At the end of the day, web servers listen for requests, parse those requests, and send responses. The Node runtime will get these requests first and turn them from raw bytes into two JavaScript objects that you can handle: one object for the request (req) and one object for the response (res). When working with Node.js by itself, the flow looks like figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1. When working with Node by itself, you have one function that gives you a request object representing the incoming request and a response object representing the response node should send back to the client.

These two objects will be sent to a JavaScript function that you’ll write. You’ll parse req to see what the user wants and manipulate res to prepare your response.

After a while, you’ll have finished writing to the response. When that has happened, you’ll call res.end. This signals to Node that the response is all done and ready to be sent over the wire. The Node runtime will see what you’ve done to the response object, turn it into another bundle of bytes, and send it over the internet to whoever requested it.

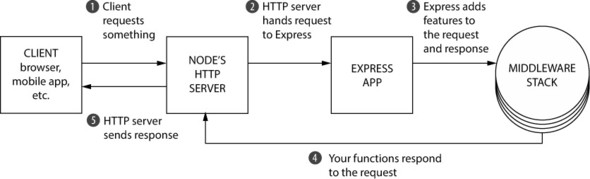

In Node, these two objects are passed through just one function. But in Express, these objects are passed through an array of functions, called the middleware stack. Express will start at the first function in the stack and continue in order down the stack, as shown in figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2. When working in Express, the one request handler function is replaced with a stack of middleware functions.

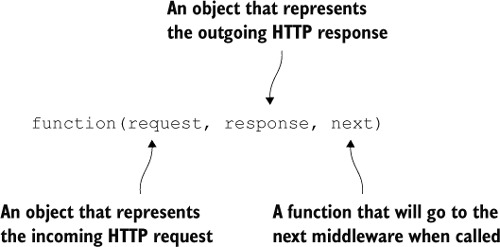

Every function in this stack takes three arguments. The first two are req and res from before. They’re given to you by Node, although Express decorates them with a few convenience features that we discussed in the previous chapter.

The third argument to each of these functions is itself a function, conventionally called next. When next is called, Express will go on to the next function in the stack. Figure 4.3 shows the signature of a middleware function.

Figure 4.3. All middleware functions have the same signature with three functions: request, response, and next.

Eventually, one of these functions in the stack must call res.end, which will end the request. (In Express, you can also call some other methods like res.send or res.send-File, but these call res.end internally.) You can call res.end in any of the functions in the middleware stack, but you must only do it once or you’ll get an error.

This might be a little abstract and foggy. Let’s see an example of how this works by building a static file server.

4.2. Example app: a static file server

Let’s build a simple little application that serves files from a folder. You can put anything in this folder and it’ll be served—HTML files, images, or an MP3 of yourself singing Celine Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On.”

This folder will be called static and it will live in your project’s directory. If there’s a file called celine.mp3 and a user visits /celine.mp3, your server should send that MP3 over the internet. If the user requests /burrito.html, no such file exists in the folder, so your server should send a 404 error.

Another requirement is that your server should log every request, whether or not it’s successful. It should log the URL that the user requested with the time that they requested it.

This Express application will be made up of three functions on the middleware stack:

- The logger —This will output the requested URL and the time it was requested to the console. It’ll always continue on to the next middleware. (In terms of code, it’ll always call next.)

- The static file sender —This will check if the file exists in the folder. If it does, it’ll send that file over the internet. If the requested file doesn’t exist, it’ll continue on to the final middleware (once again, calling next).

- The 404 handler —If this middleware is hit, it means that the previous one didn’t find a file, and you should return a 404 message and finish up the request.

You could visualize this middleware stack like the one shown in figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4. The middleware stack of our static file server application

Enough talking. Let’s build this thing.

4.2.1. Getting set up

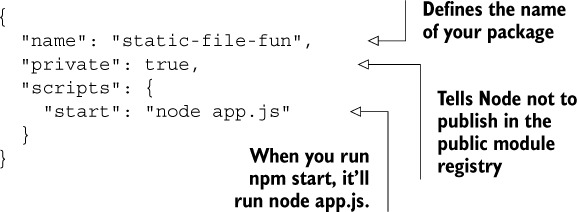

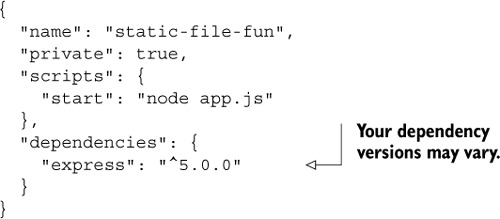

Start by making a new directory. You can call it whatever you’d like; let’s choose static-file-fun. Inside this directory, create a file called package.json, as shown in the following listing. This file is present in every Node.js project and describes metadata about your package, from its title to its third-party dependencies.

Listing 4.1. The package.json file for your static file application

Once you’ve saved this package.json, you’ll want to install the latest version of Express. From inside this directory, run npm install express --save. This will install Express into a directory called node_modules inside of this folder. It’ll also add Express as a dependency in package.json. package.json will now look like the following listing.

Listing 4.2. Updated package.json file for your static file application

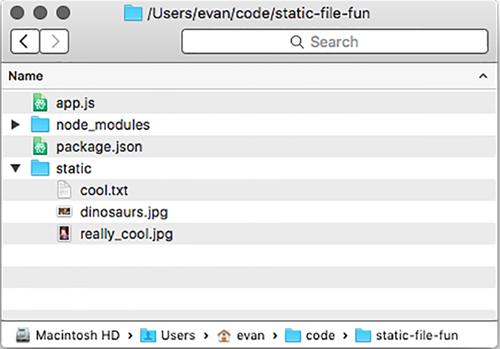

Next, create a folder called static inside of this new project directory (right next to package.json). Put a few files inside—maybe an HTML file or an image or two. It doesn’t really matter what you put in there, but put some files that your example app will serve.

As a last step, create app.js in the root of your project, which will contain all of your app’s code. Your folder structure will look something like the one in figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5. The directory structure of static-file-fun

When you want to run this app, you’ll run npm start. This command will look inside your package.json file, see that you’ve added a script called start, and run that command. In this case, it’ll run node app.js.

Running npm start won’t do anything yet—you haven’t written your app—but you’ll run that whenever you want to run your application.

Okay. Let’s write the app!

Why use npm start at all—why don’t you run node app.js instead? There are three reasons you might do this.

It’s a convention. Most Node web servers can be started with npm start, regardless of the project’s structure. If instead of app.js someone had chosen application.js, you’d have to know about that change. The Node community seems to have settled on a common convention here.

It allows you to run a more complex command (or set of commands) with a relatively simple one. Your app is pretty simple now, but starting it could be more complex in the future. Perhaps you’ll need to start up a database server or clear a giant log file. Keeping this complexity under the blanket of a simple command helps keep things consistent and more pleasant.

The third reason is a little more nuanced. npm lets you install packages globally, so you can run them just like any other terminal command. Bower is a common one, letting you install front-end dependencies from the command line with the bower command. You install things like Bower globally on your system. npm scripts allow you to add new commands to your project without installing them globally, so that you can keep all of your dependencies inside your project, allowing you to have unique versions per project. This comes in handy for things like testing and build scripts, as you’ll see down the line.

At the end of the day, you could run node app.js and never type npm start, but I find the reasons just mentioned compelling enough to do it.

4.2.2. Writing your first middleware function: the logger

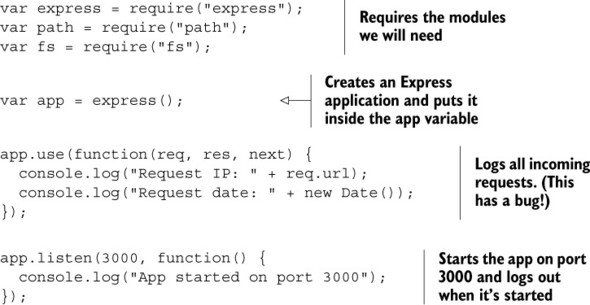

You’ll start by making your app log requests. Put the code in the following listing inside app.js.

Listing 4.3. Start app.js for your static file server

For now, all you have is an application that logs every request that comes into the server. Once you’ve set up your app (the first few lines), you call app.use to add a function to your application’s middleware stack. When a request comes in to this application, that function will be called.

Unfortunately, even this simple app has a critical bug. Run npm start and visit localhost:3000 in your browser to see it.

You’ll see the request being logged into the console, and that’s great news. But your browser will hang—the loading spinner will spin and spin and spin, until the request eventually times out and you get an error in your browser. That’s not good!

This is happening because you didn’t call next. When your middleware function is finished, it needs to do one of two things:

- It needs to finish responding to the request (with res.end or one of Express’s convenience methods like res.send or res.sendFile).

- It needs to call next to continue on to the next function in the middleware stack.

If you do either of those, your app will work just fine. If you do neither, inbound requests will never get a response; their loading spinners will never stop spinning (this is what happened previously). If you do both, only the first response finisher will go through and the rest will be ignored, which is almost certainly unintentional!

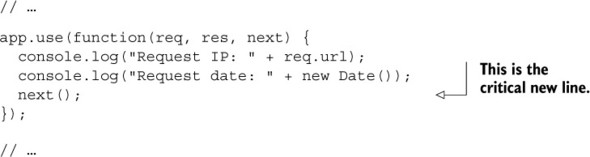

These bugs are usually pretty easy to catch once you know how to spot them. If you’re not responding to the request and you’re not calling next, it’ll look like your server is super slow. You can fix your middleware by calling next, as shown in the next listing.

Listing 4.4. Fixing your logging middleware

Now, if you stop your app, run npm start again, and visit http://localhost:3000 in your browser, you should see your server logging all of the requests and immediately failing with an error message (something like “Cannot GET /”). Because you’re never responding to the request yourself, Express will give an error to the user, and it will happen immediately.

Now that you’ve written your logger, let’s write the next part—the static file server middleware.

So far, when you change your code, you have to stop your server and start it again. This can get repetitive! To alleviate this problem, you can install a tool called nodemon, which will watch all of your files for changes and restart if it detects any.

You can install nodemon by running npm install nodemon --global.

Once it’s installed, you can start a file in watch mode by replacing node with nodemon in your command. If you typed node app.js earlier, just change it to nodemon app.js, and your app will continuously reload when it changes.

4.2.3. The static file server middleware

At a high level, this is what the static file server middleware should do:

1. Check if the requested file exists in the static directory.

2. If it exists, respond with the file and call it a day. In code terms, this is a call to res.sendFile.

3. If the file doesn’t exist, continue to the next middleware in the stack. In code terms, this is a call to next.

Let’s turn that requirement into code. You’ll start by building it yourself to understand how it works, and then you’ll shorten it with some helpful third-party code.

You’ll make use of Node’s built-in path module, which will let you determine the path that the user requests. To determine whether the file exists, you’ll use another Node built-in: the fs module.

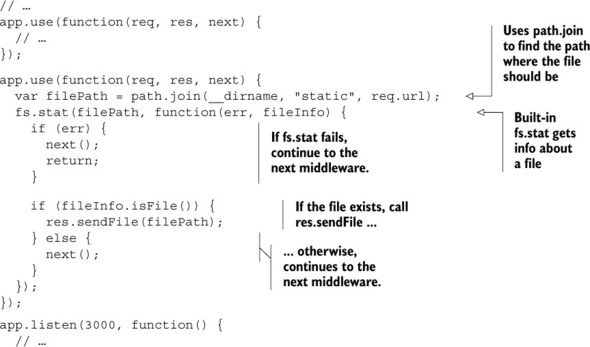

Add the code in the following listing to app.js after your logging middleware.

Listing 4.5. Adding static file middleware to the middleware stack

The first thing you do in this function is use path.join to determine the path of the file. If the user visits /celine.mp3, req.url will be the string "/celine.mp3". Therefore, filePath will be something like "/path/to/your/project/static/celine.mp3". The path will look pretty different depending on where you’ve stored your project and on your operating system, but it’ll be the path to the file that was requested.

Next, you call fs.exists, which takes two arguments. The first is the path to check (the filePath you just figured out) and the second is a function. When Node has figured out information about the file, it’ll call this callback with two arguments. The callback’s first argument is an error, in case something goes wrong. The second argument is an object that has some methods about the file, such as isDirectory() or isFile(). We use the isFile() method to determine whether the file exists.

Express applications have asynchronous behavior like this all the time. That’s why we must have next in the first place! If everything were synchronous, Express would know exactly where every middleware ended: when the function finished (either by calling return or hitting the end). You wouldn’t need to have next anywhere. But because things are asynchronous, you need to manually tell Express when to continue on to the next middleware in the stack.

Once the callback has completed, you run through a simple conditional. If the file exists, send the file. Otherwise, continue on to the next middleware.

Now, when you run your app with npm start, try visiting resources you’ve put into the static file directory. If you have a file called secret_plans.txt in the static file folder, visit localhost:3000/secret_plans.txt to see it. You should also continue to see the logging, just as before.

If you visit a URL that doesn’t have a corresponding file, you should still see the error message from before. This is because you’re calling next and there’s no more middleware in the stack. Let’s add the final one—the 404 handler.

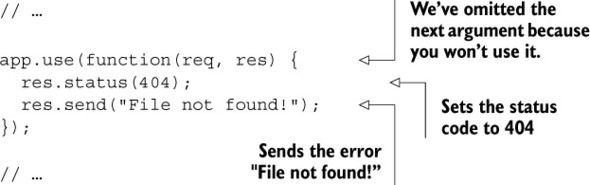

4.2.4. 404 handler middleware

The 404 handler shown in the next listing is the last function in your middleware stack. It’ll always send a 404 error, no matter what. Add this after the previous middleware.

Listing 4.6. Your final middleware: the 404 handler

This is the final piece of the puzzle. Now, when you start your server, you’ll see the whole thing in action. If you visit a file that’s in the folder, it’ll show up. If not, you’ll see your 404 error. And all the while, you’ll see logs in the console.

For a moment, try moving the 404 handler. Make it the first middleware in the stack instead of the last. If you rerun your app, you’ll see that you always get a 404 error no matter what. Your app hits the first middleware and never continues on. The order of your middleware stack is important—make sure your requests flow through in the proper order.

Here’s what the app should look like.

Listing 4.7. The first version of the static file app (app.js)

var express = require("express");

var path = require("path");

var fs = require("fs");

var app = express();

app.use(function(req, res, next) {

console.log("Request IP: " + req.url);

console.log("Request date: " + new Date());

next();

});

app.use(function(req, res, next) {

var filePath = path.join(__dirname, "static", req.url);

fs.stat(filePath, function(err, fileInfo) {

if (err) {

next();

return;

}

if (fileInfo.isFile()) {

res.sendFile(filePath);

} else {

next();

}

});

});

app.use(function(req, res) {

res.status(404);

res.send("File not found!");

});

app.listen(3000, function() {

console.log("App started on port 3000");

});

But as always, there’s more you can do.

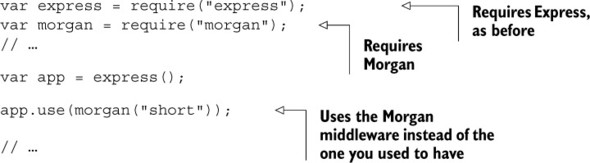

4.2.5. Switching your logger to an open source one: Morgan

A common piece of advice in software development is “don’t reinvent the wheel.” If someone else has already solved your problem, it’s often a good idea to take their solution and move on to better things.

That’s what you’ll do with your logging middleware. You’ll remove the hard work you put in (all five lines) and use a piece of middleware called Morgan (https://github.com/expressjs/morgan). It’s not baked into core Express, but it is maintained by the Express team.

Morgan describes itself as “request logger middleware,” which is exactly what you want. Run npm install morgan --save to install the latest version of the Morgan package. You’ll see it inside a new folder inside of node_modules, and it’ll also appear in package.json.

Now, let’s change app.js to use Morgan instead of your logging middleware, as shown in the next listing.

Listing 4.8. app.js that now uses Morgan

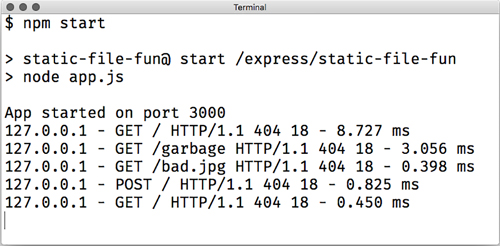

Now, when you run this app, you’ll see output like that shown in figure 4.6, with the IP address and a bunch of other useful information.

Figure 4.6. Our application’s logs after adding Morgan

So, what’s happening here? morgan is a function that returns a middleware function. When you call it, it will return a function like the one you wrote previously; it’ll take three arguments and call console.log. Most third-party middleware works this way—you call a function that returns the middleware, which you then use. You could have written the previous one like the following.

Listing 4.9. An alternative use of Morgan

var morganMiddleware = morgan("short");

app.use(morganMiddleware);

Notice that you’re calling Morgan with one argument: a string, "short". This is a Morgan-specific configuration option that dictates what the output should look like. There are other format strings that have more or less information: "combined" gives a lot of info; "tiny" gives a minimal output. When you call Morgan with different configuration options, you’re effectively making it return a different middleware function.

Morgan is the first example of open source middleware you’ll use, but you’ll use a lot throughout this book. You’ll use another one to replace your second middleware function: the static file server.

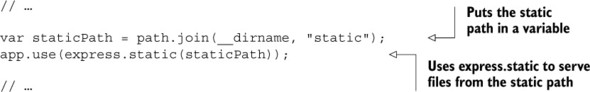

4.2.6. Switching to Express’s built-in static file middleware

There’s only one piece of middleware that’s bundled with Express, and it replaces your second middleware.

It’s called express.static. It works a lot like the middleware we wrote, but it has a bunch of other features. It does several complicated tricks to achieve better security and performance, such as adding a caching mechanism. If you’re interested in more of its benefits, you can read my blog post at http://evanhahn.com/express-dot-static-deep-dive/.

Like Morgan, express.static is a function that returns a middleware function. It takes one argument: the path to the folder you’ll be using for static files. To get this path, you’ll use path.join, like before. Then you’ll pass it to the static middleware.

Replace your static file middleware with the code in the following listing.

Listing 4.10. Replacing your static file middleware with Express’s

It’s a bit more complicated because it has more features, but express.static functions quite similarly to what you had before. If the file exists at the path, it will send it. If not, it will call next and continue on to the next middleware in the stack.

If you restart your app, you won’t notice much difference in functionality, but your code will be much shorter. Because you’re using battle-tested middleware instead of your own, you’ll also be getting a much more reliable set of features.

Now your app code looks like this.

Listing 4.11. The next version of your static file app (app.js)

var express = require("express");

var morgan = require("morgan");

var path = require("path");

var app = express();

app.use(morgan("short"));

var staticPath = path.join(__dirname, "static");

app.use(express.static(staticPath));

app.use(function(req, res) {

res.status(404);

res.send("File not found!");

});

app.listen(3000, function() {

console.log("App started on port 3000");

});

I think you can call your Express-powered static file server complete for now. Well done, hero.

4.3. Error-handling middleware

Remember when I said that calling next would continue on to the next middleware? I lied. It was mostly true but I didn’t want to confuse you.

There are two types of middleware. You’ve been dealing with the first type so far—regular middleware functions that take three arguments (sometimes two when next is discarded). Most of the time, your app is in normal mode, which looks only at these middleware functions and skips the other.

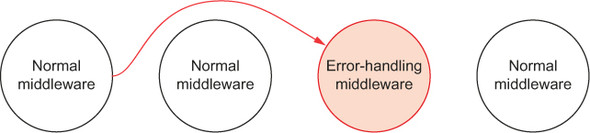

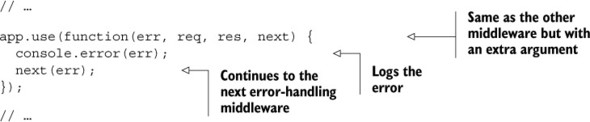

There’s a second kind that’s much less-used: error-handling middleware. When your app is in error mode, all regular middleware is ignored and Express will execute only error-handling middleware functions. To enter error mode, simply call next with an argument. It’s convention to call it with an error object, as in next(new Error ("Something bad happened!")).

These middleware functions take four arguments instead of two or three. The first one is the error (the argument passed into next), and the remainder are the three from before: req, res, and next. You can do anything you want in this middleware. When you’re done, it’s just like other middleware: you can call res.end or next. Calling next with no arguments will exit error mode and move onto the next normal middleware; calling it with an argument will continue onto the next error-handling middleware if one exists.

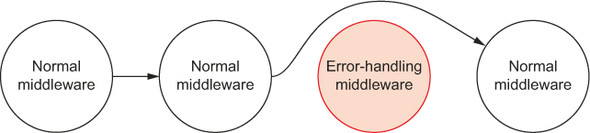

Let’s say you have four middleware functions in a row. The first two are normal, the third handles errors, and the fourth is normal. If no errors happen, the flow will look something like figure 4.7.

Figure 4.7. If all goes well, error-handling middleware will be skipped.

If no errors happen, it’ll be as if the error-handling middleware never existed. To reiterate more precisely, “no errors” means “next was never called with any arguments.” If an error does happen, then Express will skip over all other middleware until the first error-handling middleware in the stack. It might look like figure 4.8.

Figure 4.8. If there’s an error, Express will skip straight to the error-handling middleware.

While not enforced, error-handling middleware is conventionally placed at the end of your middleware stack, after all the normal middleware has been added. This is because you want to catch any errors that come cascading down from earlier in the stack.

Express’s error-handling middleware does not handle errors that are thrown with the throw keyword, only when you call next with an argument.

Express has some protections in place for these exceptions. The app will return a 500 error and that request will fail, but the app will keep on running. Some errors like syntax errors, however, will crash your server.

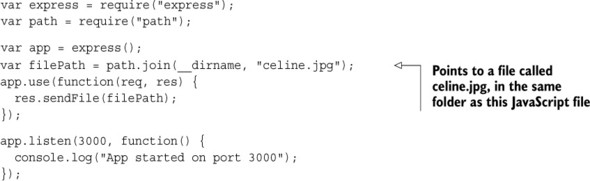

Let’s say that you’re writing a really simple Express app that sends a picture to the user, no matter what. We’ll use res.sendFile just like before. The following listing shows what that simple app might look like.

Listing 4.12. A simple app that always sends a file

This code should look like a simplified version of the static file server you built previously. It’ll unconditionally send celine.jpg over the internet.

But what if that file doesn’t exist on your computer? What if it has trouble reading the file? You’ll want to have some way of handling that error. Error-handling middleware to the rescue!

To enter error mode, you’ll start by using a convenient feature of res.sendFile: it can take an extra argument, which is a callback. This callback is executed after the file is sent, and if there’s an error in sending, it’s passed an argument. If you wanted to print its success, you might do something like the following listing.

Listing 4.13. Printing whether a file successfully sent

res.sendFile(filePath, function(err) {

if (err) {

console.error("File failed to send.");

} else {

console.log("File sent!");

}

});

Instead of printing the success story to the console, you can enter error mode by calling next with an argument if there’s an error. You can do something like this next listing.

Listing 4.14. Entering error mode if a file fails to send

// ...

app.use(function(req, res, next) {

res.sendFile(filePath, function(err) {

if (err) {

next(new Error("Error sending file!"));

}

});

});

// ...

Now that you’re in this error mode, you can handle it.

It’s common to have a log of all errors that happen in your app, but you don’t usually display this to users. A long JavaScript stack trace might be pretty confusing to a nontechnical user. It might also expose your code to hackers—if a hacker can get a glimpse into how your site works, they can find things to exploit.

Let’s write simple middleware that logs errors but doesn’t respond to the error. It’ll look a lot like your middleware from before, but instead of logging request information, it’ll log the error. You could add the following to your file after all the normal middleware.

Listing 4.15. Middleware that logs all errors

Now, when an error comes through, you’ll log it to the console so that you can investigate it later. But there’s more that needs to be done to handle this error. This is similar to before—the logger did something, but it didn’t respond to the request. Let’s write that part.

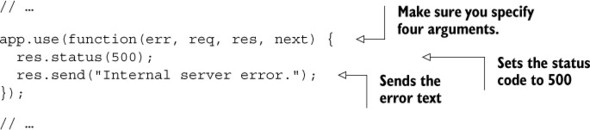

You can add this code after the previous middleware. This will simply respond to the error with a 500 status code.

Listing 4.16. Responding to the error

Keep in mind that, no matter where this middleware is placed in your stack, it won’t be called unless you’re in error mode—in code, this means calling next with an argument.

You may notice that this error-handling middleware has four arguments but we don’t use all of them. Express uses the number of arguments of a function to determine which middleware handles errors and which doesn’t.

For simple applications, there aren’t loads and loads of places where things can go wrong. But as your apps grow, you’ll want to remember to test errant behavior. If a request fails and it shouldn’t, make sure you handle that gracefully instead of crashing. If an action should perform successfully but fails, make sure your server doesn’t explode. Error-handling middleware can help this along.

4.4. Other useful middleware

Two different Express applications can have pretty different middleware stacks. Our example app’s stack is just one of many possible middleware configurations, and there are lots out there that you can use.

There’s only one piece of middleware that’s bundled with Express, and that’s express.static. You’ll be installing and using lots of other middleware throughout this book.

Although these modules aren’t bundled with Express, the Express team maintains a number of middleware modules:

- body-parser for parsing request bodies. For example, when a user submits a form. See more at https://github.com/expressjs/body-parser.

- cookie-parser for parsing cookies from users. It needs to be paired with another Express-supported middleware like express-session. Once you’ve done this, you can keep track of users, providing them with user accounts and other features. We’ll explore this in greater detail in chapter 7. https://github.com/expressjs/cookie-session has more details.

- Compression for compressing responses to save on bytes. See more at https://github.com/expressjs/compression.

You can find the full list on the Express homepage at http://expressjs.com/resources/middleware.html. There’s also a huge number of third-party middleware modules that we’ll explore. To name two:

- Helmet —Helps to secure your applications. It doesn’t magically make you more secure, but a small amount of work can protect you from a lot of hacks. Read more at https://github.com/helmetjs/helmet. (I maintain this module, by the way, so I have to promote it!)

- connect-assets —Compiles and minifies your CSS and JavaScript assets. It will also work with CSS preprocessors like SASS, SCSS, LESS, and Stylus, should you choose to use them. See https://github.com/adunkman/connect-assets.

This is hardly an exhaustive list. I also recommend a number of helpful modules in appendix A if you’re thirsty for even more helpers.

4.5. Summary

- Express applications have a middleware stack. When a request enters your application, requests go through this middleware stack from the top to the bottom, unless they’re interrupted by a response or an error.

- Middleware is written with request handler functions. These functions take two arguments at a minimum: first, an object representing the incoming request; second, an object representing the outgoing response. They often take a function that tells them how to continue on to the next middleware in the stack.

- There are numerous third-party middleware written for your use. Many of these are maintained by Express developers.