Chapter 1. What is Express?

- Node.js, a JavaScript platform typically used to run JavaScript on servers

- Express, a framework that sits on top of Node.js’s web server and makes it easier to use

- Middleware and routing, two features of Express

- Request handler functions

Before we talk about Express, we need to talk about Node.js.

For most of its life, the JavaScript programming language has lived inside web browsers. It started as a simple scripting language for modifying small details of web pages but grew into a complex language, with loads of applications and libraries. Many browser vendors like Mozilla and Google began to pump resources into fast JavaScript runtimes, and browsers got much faster JavaScript engines as a result.

In 2009, Node.js came along. Node.js took V8, Google Chrome’s powerful JavaScript engine, out of the browser and enabled it to run on servers. In the browser, developers had no choice but to pick JavaScript. In addition to Ruby, Python, C#, Java, and other languages, developers could now choose JavaScript when developing server-side applications.

JavaScript might not be the perfect language for everyone, but Node.js has real benefits. For one, the V8 JavaScript engine is fast, and Node.js encourages an asynchronous coding style, making for faster code while avoiding multithreaded nightmares. JavaScript also had a bevy of useful libraries because of its popularity. But the biggest benefit of Node.js is the ability to share code between browser and server. Developers don’t have to do any kind of context switch when going from client and server. Now they can use the same code and the same coding paradigms between two JavaScript runtimes: the browser and the server.

Node.js caught on—people thought it was pretty cool. Like browser-based JavaScript, Node.js provides a bevy of low-level features you’d need to build an application. But like browser-based JavaScript, its low-level offerings can be verbose and difficult to use.

Enter Express, a framework that acts as a light layer atop the Node.js web server, making it more pleasant to develop Node.js web applications.

Express is philosophically similar to jQuery. People want to add dynamic content to their web pages, but the vanilla browser APIs can be verbose, confusing, and limited in features. Developers often have to write boilerplate code, and a lot of it. jQuery exists to cut down on this boilerplate code by simplifying the APIs of the browser and adding helpful new features. That’s basically it.

Express is exactly the same. People want to make web applications with Node.js, but the vanilla Node.js APIs can be verbose, confusing, and limited in features. Developers often have to write a lot of boilerplate code. Express exists to cut down on this boilerplate code by simplifying the APIs of Node.js and adding helpful new features. That’s basically it!

Like jQuery, Express aims to be extensible. It’s hands-off about most parts of your applications’ decisions and is easily extended with third-party libraries. Throughout this book and your Express career, you’ll have to make decisions about your applications’ architectures, and you’ll extend Express with a bevy of powerful third-party modules.

You probably didn’t pick up this book for the “in short” definition, though. The rest of this chapter (and book, really) will discuss Express in much more depth.

Note

This book assumes that you’re proficient in JavaScript but not Node.js.

1.1. What is this Node.js business?

Node.js is not child’s play. When I first started using Node.js, I was confused. What is it?

Node.js (often shortened to Node) is a JavaScript platform—a way to run JavaScript. Most of the time, JavaScript is run in web browsers, but there’s nothing about the JavaScript language that requires it to be run in a browser. It’s a programming language just like Ruby or Python or C++ or PHP or Java. Sure, there are JavaScript runtimes bundled with all popular web browsers, but that doesn’t mean that it has to be run there. If you were running a Python file called myfile.py, you would run python myfile.py. But you could write your own Python interpreter, call it SnakeWoman, and run snakewoman myfile.py. Its developers did the same with Node.js; instead of typing javascript myfile.js, you type node myfile.js.

Running JavaScript outside the browser lets you do a lot—anything a regular programming language could do, really—but it’s mostly used for web development.

Okay, so you can run JavaScript on the server—why would you do this?

A lot of developers will tell you that Node.js is fast, and that’s true. Node.js isn’t the fastest thing on the market by any means, but it’s fast for two reasons.

The first is pretty simple: the JavaScript engine is fast. It’s based on the engine used in Google Chrome, which has a famously quick JavaScript engine. It can execute JavaScript like there’s no tomorrow, processing thousands of instructions a second.

The second reason for its speed lies in its ability to handle concurrency, and it’s a bit less straightforward. Its performance comes from its asynchronous workings.

The best real-world analogy I can come up with is baking. Let’s say I’m making muffins. I have to prepare the batter and while I’m doing that, I can’t do anything else. I can’t sit down and read a book, I can’t cook something else, and so on. But once I put the muffins in the oven, I don’t have to stand there looking at the oven until they’re done—I can do something else. Maybe I start preparing more batter. Maybe I read a book. In any case, I don’t have to wait for the muffins to finish baking for me to be able to do something else.

In Node.js, a browser might request something from your server. You begin responding to this request and another request comes in. Let’s say both requests have to talk to an external database. You can ask the external database about the first request, and while that external database is thinking, you can begin to respond to the second request. Your code isn’t doing two things at once, but when someone else is working on something, you’re not held up waiting.

Other runtimes don’t have this luxury built in by default. Ruby on Rails, for example, can process only one request at a time. To process more than one at a time, you effectively have to buy more servers. (There are, of course, many asterisks to this claim.)

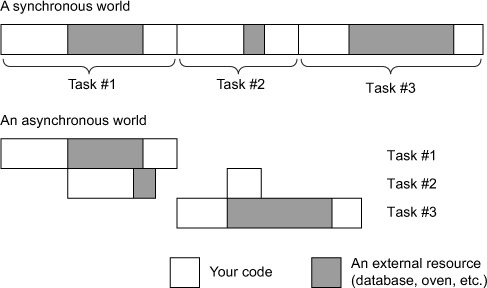

Figure 1.1 demonstrates what this might look like.

Figure 1.1. Comparing asynchronous code (like Node.js) to synchronous code. Note that asynchronous code can complete much faster, even though you’re never executing your code in parallel.

I don’t mean to tell you that Node.js is the fastest in the world because of its asynchronous capabilities. Node.js can squeeze a lot of performance out of one CPU core, but it doesn’t excel with multiple cores. Other programming languages truly allow you to actively do two things at once. To reuse the baking example: other programming languages let you buy more ovens so that you can bake more muffins simultaneously. Node.js is beginning to support this functionality but it’s not as first-class in Node.js as it is in other programming languages.

Personally, I don’t believe that performance is the biggest reason to choose Node.js. Although it’s often faster than other scripting languages like Ruby or Python, I think the biggest reason is that it’s all one programming language.

Often, when you’re writing a web application, you’ll be using JavaScript. But before Node.js, you’d have to code everything in two different programming languages. You’d have to learn two different technologies, paradigms, and libraries. With Node.js, a back-end developer can jump into front-end code and vice versa. Personally, I think this is the most powerful feature of the runtime.

Other people seem to agree: some developers have created the MEAN stack, which is an all-JavaScript web application stack consisting of MongoDB (a database controlled by JavaScript), Express, Angular.js (a front-end JavaScript framework), and Node.js. The JavaScript everywhere mentality is a huge benefit of Node.js.

Large companies such as Wal-Mart, the BBC, LinkedIn, and PayPal are even getting behind Node.js. It’s not child’s play.

1.2. What is Express?

Express is a relatively small framework that sits on top of Node.js’s web server functionality to simplify its APIs and add helpful new features. It makes it easier to organize your application’s functionality with middleware and routing; it adds helpful utilities to Node.js’s HTTP objects; it facilitates the rendering of dynamic HTML views; it defines an easily implemented extensibility standard. This book explores those features in a lot more depth, so all of that lingo will be demystified soon.

1.2.1. The functionality in Node.js

When you’re creating a web application (to be more precise, a web server) in Node.js, you write a single JavaScript function for your entire application. This function listens to a web browser’s requests, or the requests from a mobile application consuming your API, or any other client talking to your server. When a request comes in, this function will look at the request and determine how to respond. If you visit the homepage in a web browser, for example, this function could determine that you want the homepage and it will send back some HTML. If you send a message to an API endpoint, this function could determine what you want and respond with JSON (for example).

Imagine you’re writing a web application that tells users the time and time zone on the server. It will work like this:

- If the client requests the homepage, your application will return an HTML page showing the time.

- If the client requests anything else, your application will return an HTTP 404 “Not Found” error and some accompanying text.

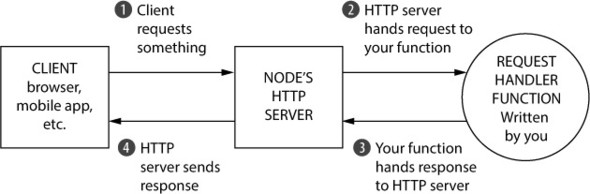

If you were building your application on top of Node.js without Express, a client hitting your server might look like figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2. The flow of a request through a Node.js web application. Circles are written by you as the developer; squares are out of your domain.

The JavaScript function that processes browser requests in your application is called a request handler. There’s nothing too special about this; it’s a JavaScript function that takes the request, figures out what to do, and responds. Node.js’s HTTP server handles the connection between the client and your JavaScript function so that you don’t have to handle tricky network protocols.

In code, it’s a function that takes two arguments: an object that represents the request and an object that represents the response. In your time/time zone application, the request handler function might check for the URL that the client is requesting. If they’re requesting the homepage, the request handler function should respond with the current time in an HTML page. Otherwise, it should respond with a 404. Every Node.js application is just like this: it’s a single request handler function responding to requests. Conceptually, it’s pretty simple.

The problem is that the Node.js APIs can get complex. Want to send a single JPEG file? That’ll be about 45 lines of code. Want to create reusable HTML templates? Figure out how to do it yourself. Node.js’s HTTP server is powerful, but it’s missing a lot of features that you might want if you were building a real application.

Express was born to make it easier to write web applications with Node.js.

1.2.2. What Express adds to Node.js

In broad strokes, Express adds two big features to the Node.js HTTP server:

- It adds a number of helpful conveniences to Node.js’s HTTP server, abstracting away a lot of its complexity. For example, sending a single JPEG file is fairly complex in raw Node.js (especially if you have performance in mind); Express reduces it to one line.

- It lets you refactor one monolithic request handler function into many smaller request handlers that handle only specific bits and pieces. This is more maintainable and more modular.

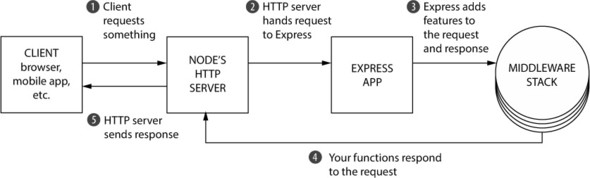

In contrast to figure 1.2, figure 1.3 shows how a request would flow through an Express application.

Figure 1.3. The flow of a request through an Express. Once again, circles are code you write and squares are out of your domain.

Figure 1.3 might look more complicated, but it’s much simpler for you as the developer. There are essentially two things going on here:

- Rather than one large request handler function, Express has you writing many smaller functions (many of which can be third-party functions and not written by you). Some functions are executed for every request (for example, a function that logs all requests), and other functions are only executed sometimes (for example, a function that handles only the homepage or the 404 page). Express has many utilities for partitioning these smaller request handler functions.

- Request handler functions take two arguments: the request and the response. Node’s HTTP server provides some functionality; for example, Node.js’s HTTP server lets you extract the browser’s user agent in one of its variables. Express augments this by adding extra features such as easy access to the incoming request’s IP address and improved parsing of URLs. The response object also gets beefed up; Express adds things like the sendFile method, a one-line command that translates to about 45 lines of complicated file code. This makes it easier to write these request handler functions.

Instead of managing one monolithic request handler function with verbose Node.js APIs, you write multiple small request handler functions that are made more pleasant by Express and its easier APIs.

1.3. Express’s minimal philosophy

Express is a framework, which means you’ll have to build your app the Express way. But the Express way isn’t too opinionated; it doesn’t give you a very rigid structure. That means you can build many different kinds of applications, from video chat applications to blogs to APIs.

It’s very rare to build an Express app of any size that uses only Express. Express by itself probably doesn’t do everything you need, and you’ll likely find yourself with a large number of other libraries that you integrate into your Express applications. (We’ll look at many of these libraries throughout the book.) You can have exactly what you need without any extra cruft, and it enables you to confidently understand every part of your application. In this way, it lends itself well to the do-one-thing-well philosophy from the Unix world.

But this minimalism is a double-edged sword. It’s flexible and your apps are free of unused cruft, but it does very little for you in comparison to other frameworks. This means that you make mistakes, you have to make far more decisions about your application’s architecture, and you have to spend more time hunting for the right third-party modules. You get less out of the box.

Some might like a flexible framework, others might want more rigidity. PayPal, for instance, likes Express but built a framework on top of it that more strictly enforces conventions for their many developers. Express doesn’t care how you structure your apps, so two developers might make different decisions.

Because you’re given the reins to steer your app in any direction, you might make an unwise decision that’ll bite you later down the line. Sometimes, I look back on my still-learning-Express applications and think, “Why did I do things this way?”

To write less code yourself, you wind up hunting for the right third-party packages to use. Sometimes, it’s easy—there’s one module that everyone loves and you love it too and it’s a match made in heaven. Other times, it’s harder to choose, because there are a lot of okay-ish ones or a small number of pretty good ones. A bigger framework can save you that time and headache, and you’ll simply use what you’re given.

There’s no right answer to this, and this book isn’t going to try to debate the ultimate winner of the fight between big and small frameworks. But the fact of the matter is that Express is a minimalist framework, for better or for worse!

1.4. The core parts of Express

All right, so Express is minimal, and it sugarcoats Node.js to make it easier to use. How does it do that?

When you get right down to it, Express has just four major features: middleware, routing, subapplications, and conveniences. There’s a lot of conceptual stuff in the next few sections, but it’s not just hand-waving; we’ll get to the nitty-gritty details in the following chapters.

1.4.1. Middleware

As you saw earlier, raw Node.js gives you one request handler function to work with. The request comes into your function and the response goes out of your function.

Middleware is poorly named, but it’s a term that’s not Express-specific and has been around for a while. The idea is pretty simple: rather than one monolithic request handler function, you call several request handler functions that each deal with a small chunk of the work. These smaller request handler functions are called middleware functions, or middleware.

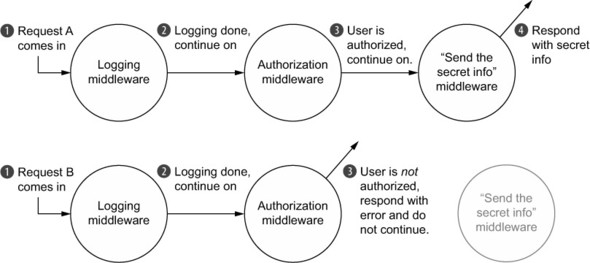

Middleware can handle tasks from logging requests to sending static files to setting HTTP headers. The first middleware function you might use in an application is a logger—it logs every request that comes into your server. When the logger has finished logging, it will continue on to the next middleware in the chain. This next middleware function might authenticate users. If they’re visiting a forbidden URL, it will respond with a “not authorized” page. If they are allowed to visit it, they can continue to the next function in the chain. The next function might send the homepage and be done. An illustration of two possible options is shown in figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4. Two requests flowing through middleware functions. Notice that middleware sometimes continues on, but sometimes it responds to requests.

In figure 1.4, the logging middleware is first in the chain and is always called, so something will always be noted in the log file. Next, the logging middleware continues to the next one in the chain, the authorization middleware. The authorization middleware decides, by some decree, whether the user is authorized to keep going. If they are, the authorization middleware signals that it wants to continue on to the next middleware in the chain. Otherwise, the middleware sends a “you’re not authorized!” message to the user and halts the chain. (This message could be an HTML page or a JSON response or anything else, depending on the application.) The last middleware, if it’s called, will send secret information and not continue to any further middleware in the chain. (Once again, this last middleware can send any kind of response, from HTML to JSON to an image file.)

One of the biggest features of middleware is that it’s relatively standardized, which means that lots of people have developed middleware for Express (including folks on the Express team). That means that if you can dream up the middleware, someone has probably already made it. There’s middleware to compile static assets like LESS and SCSS; there’s middleware for security and user authentication; there’s middleware to parse cookies and sessions.

1.4.2. Routing

Routing is better named than middleware. Like middleware, it breaks the one monolithic request handler function into smaller pieces. Unlike middleware, these request handlers are executed conditionally, depending on what URL and HTTP method a client sends.

For example, you might build a web page with a homepage and a guestbook. When the user sends an HTTP GET to the homepage URL, Express should send the homepage. But when they visit the guestbook URL, it should send them the HTML for the guestbook, not for the homepage! And if they post a comment in the guestbook (with an HTTP POST to a particular URL), this should update the guestbook. Routing allows you to partition your application’s behavior by route.

The behavior of these routes is, like middleware, defined in request handler functions. When the user visits the homepage, it will call a request handler function, written by you. When the user visits the guestbook URL, it will call another request handler function, also written by you.

Express applications have middleware and routes; they complement one another. For example, you might want to log all of the requests, but you’ll also want to serve the homepage when the user asks for it.

1.4.3. Subapplications

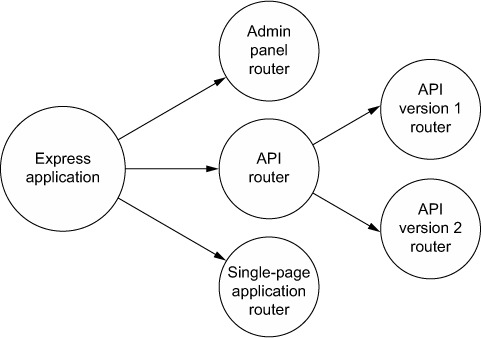

Express applications can often be pretty small, even fitting in just one file. As your applications get larger, though, you’ll want to break them up into multiple folders and files. Express is unopinionated about how you scale your app, but it provides one important feature that’s super helpful: subapplications. In Express lingo, these miniapplications are called routers.

Express allows you to define routers that can be used in larger applications. Writing these subapplications is almost exactly like writing normal-sized ones, but it allows you to further compartmentalize your app into smaller pieces. You might have an administration panel in your app, and that can function differently from the rest of your app. You could put the admin panel code side-by-side with the rest of your middleware and routes, but you can also create a subapplication for your admin panel. Figure 1.5 shows how an Express application might be broken up with routers.

Figure 1.5. An example diagram showing how a large application could be broken up into routers

This feature doesn’t really shine until your applications get large, but when they do, it’s extraordinarily helpful.

1.4.4. Conveniences

Express applications are made up of middleware and routes, both of which have you writing request handler functions, so you’ll be doing that a lot!

To make these request handler functions easier to write, Express has added a bunch of niceties. In raw Node.js, if you want to write a request handler function that sends a JPEG file from a folder, that’s a fair bit of code. In Express, that’s only one call to the sendFile method. Express has a bunch of functionality for rendering HTML more easily; Node.js keeps mum. It also comes with myriad functions that make it easier to parse requests as they come in, like grabbing the client’s IP address.

Unlike the previous features, these conveniences don’t conceptually change how you organize your app, but they can be super helpful.

1.5. The ecosystem surrounding Express

Express, like any tool, doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It lives in the Node.js ecosystem, so you have a bevy of third-party modules that can help you, such as interfaces with databases. Because Express is extensible, lots of developers have made third-party modules that work well with Express (rather than general Node.js), such as specialized middleware or ways to render dynamic HTML.

1.5.1. Express vs. other web application frameworks

Express is hardly the first web application framework, nor will it be the last. And Express isn’t the only framework in the Node.js world. Perhaps its biggest competitor is Hapi.js, an unopinionated, relatively small framework that has routing and middleware-like functionality. It’s different from Express in that it doesn’t aim to smooth out Node.js’s built-in HTTP server module but to build a rather different architecture. It’s a pretty mature framework and it is used by Mozilla, OpenTable, and even the npm registry. Although I doubt there’s much animosity between Express developers and Hapi developers, Hapi is the biggest competitor to Express.

There are larger frameworks in the Node.js world as well, perhaps the most popular of which is the full-stack Meteor. Express is unopinionated about how you build your applications but Meteor has a strict structure. Express deals only with the HTTP server layer; Meteor is full-stack, running code on both client and server. These are simply design choices—one isn’t inherently better than the other.

The same way Express piles features atop Node.js, some folks have decided to pile features atop Express. Folks at PayPal created Kraken; although Kraken is technically just Express middleware, it sets up a lot of your application, from security defaults to bundled middleware. Sails.js is another up-and-coming framework built atop Express that adds databases, WebSocket integration, API generators, an asset pipeline, and more. Both of these frameworks are more opinionated than Express by design.

Express has several features, just one of which is middleware. Connect is a web application framework for Node.js that’s only the middleware layer. Connect doesn’t have routing or conveniences; it’s just middleware. Express once used Connect for its middleware layer, and although it now does middleware without Connect, Express middleware is completely compatible with Connect middleware. That means that any middleware that works in Connect also works in Express, which adds a huge number of helpful third-party modules to your arsenal.

This is JavaScript, so there are countless other Node.js web application frameworks out there, and I’m sure I’ve offended someone by not mentioning theirs.

Outside the Node.js world, there are comparable frameworks. Express was very much inspired by Sinatra, a minimal web application framework from the Ruby world. Sinatra, like Express, has routing and middleware-like functionality. Sinatra has inspired many clones and reinterpretations of many other programming languages, so if you’ve ever used Sinatra or a Sinatra-like framework, Express will seem familiar. Express is also like Bottle and Flask from the Python world.

Express isn’t as much like Python’s Django or Ruby on Rails or ASP.NET or Java’s Play; those are larger, more opinionated frameworks with lots of features. Express is also unlike PHP; although it is code running on the server, it’s not as tightly coupled with HTML as vanilla PHP is.

This book should tell you that Express is better than all of these other frameworks, but it can’t—Express is simply one of the many ways to build a server-side web application. It has real strengths that other frameworks don’t have, like Node.js’s performance and the ubiquitous JavaScript, but it does less for you than a larger framework might do, and some people don’t think JavaScript is the finest language out there. We could argue forever about which is best and never come to an answer, but it’s important to see where Express fits into the picture.

1.5.2. What Express is used for

In theory, Express could be used to build any web application. It can process incoming requests and respond to them, so it can do things that you can do in most of the other frameworks mentioned earlier. Why would you choose Express over something else?

One of the benefits of writing code in Node.js is the ability to share JavaScript code between the browser and the server. This is helpful from a code perspective because you can literally run the same code on client and server. It’s also very helpful from a mental perspective; you don’t have to get your mind in server mode and then switch into client mode—it’s all the same thing at some level. That means that a front-end developer can write back-end code without having to learn a whole new language and its paradigms, and vice-versa. There is some learning to do—this book wouldn’t exist otherwise—but a lot of it is familiar to front-end web developers.

Express helps you do this, and people have come up with a fancy name for one arrangement of an all-JavaScript stack: the MEAN stack. Like the LAMP stack stands for Linux, Apache, MySQL, and PHP, MEAN, as I mentioned earlier, stands for MongoDB (a JavaScript-friendly database), Express, Angular (a front-end JavaScript framework), and Node.js. People like the MEAN stack because it’s full-stack JavaScript and you get all of the aforementioned benefits.

Express is often used to power single-page applications (SPAs). SPAs are very JavaScript-heavy on the front end, and they usually require a server component. The server is usually required to simply serve the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, but there’s often a REST API, too. Express can do both of these things quite well; it’s great at serving HTML and other files, and it’s great at building APIs. Because the learning curve is relatively low for front-end developers, they can whip up a simple SPA server with little new learning required.

When you write applications with Express, you can’t get away from using Node.js, so you’re going to have the E and the N parts of the MEAN stack, but the other two parts (M and A) are up to you because Express is unopinionated. Want to replace Angular with Backbone.js on the front end? Now it’s the MEBN stack. Want to use SQL instead of MongoDB? Now it’s the SEAN stack. Although MEAN is a common bit of lingo thrown around and a popular configuration, you can choose whichever you want. In this book, we’ll cover the MongoDB database, so we’ll use the MEN stack: MongoDB, Express, and Node.js.

Express also fits in side by side with a lot of real-time features. Although other programming environments can support real-time features like WebSocket and WebRTC, Node.js seems to get more of that than other languages and frameworks. That means that you can use these features in Express apps; because Node.js gets it, Express gets it too.

1.5.3. Third-party modules for Node.js and Express

The first few chapters of this book talk about core Express—things that are baked into the framework. In very broad strokes, these are routes and middleware. But more than half of the book covers how to integrate Express with third-party modules.

There are loads of third-party modules for Express. Some are made specifically for Express and are compatible with its routing and middleware features. Others aren’t made for Express specifically and work well in Node.js, so they also work well with Express.

In this book, we’ll pick a number of third-party integrations and show examples. But because Express is unopinionated, none of the contents of this book are the only options. If I cover Third-Party Tool X in this book, but you prefer Third-Party Tool Y, you can swap them out.

Express has some small features for rendering HTML. If you’ve ever used vanilla PHP or a templating language like ERB, Jinja2, HAML, or Razor, you’ve dealt with rendering HTML on the server. Express doesn’t come with any templating languages built in, but it plays nicely with almost every Node.js-based templating engine, as you’ll see. Some popular templating languages come with Express support, but others need a simple helper library. In this book, we’ll look at two options: EJS (which looks a lot like HTML) and Pug (which tries to fix HTML with a radical new syntax).

Express doesn’t have any notion of a database. You can persist your application’s data however you choose: in files, in a relational SQL database, or in another kind of storage mechanism. In this book, we’ll cover the popular MongoDB database for data storage. As we talked about earlier, you should never feel boxed in with Express. If you want to use another data store, Express will let you.

Users often want their applications to be secure. There are a number of helpful libraries and modules (some for raw Node.js and some for Express) that can tighten the belt of your Express applications. We’ll explore all of this in chapter 10 (which is one of my favorite chapters, personally). We’ll also talk about testing your Express code to make sure that the code powering your apps is robust.

An important thing to note: there’s no such thing as an Express module—only a Node.js module. A Node.js module can be compatible with Express and work well with its API, but they’re all just JavaScript served from the npm registry, and you install them the same way. Just like in other environments, some modules integrate with other modules, where others can sit alongside. At the end of the day, Express is just a Node.js module like any other.

I really hope this book is helpful and chock-full of knowledge, but there’s only so much wisdom one author can jam into a book. At some point, you’re going to need to spread your wings and find answers. Let me do my best to guide you:

For API documentation and simple guides, the official http://expressjs.com/site is the place to go. You can also find example applications all throughout the Express repository, at https://github.com/strongloop/express/tree/master/examples. I found these examples helpful when trying to find the right way to do things. There are loads of examples in there; check them out!

For Node.js modules, you’ll be using Node.js’s built-in npm tool and installing things from the registry at https://www.npmjs.com/. If you need help finding good modules, I’d give Substack’s “finding modules” a read at http://substack.net/finding_modules. It’s a great summary of how to find quality Node.js packages.

Express used to be built on another package called Connect, and it’s still largely compatible with Connect-made modules. If you can’t find a module for Express, you might have luck searching for Connect. This also applies if you’re searching for answers to questions. And as always, use your favorite search engine.

1.6. The obligatory Hello World

Every introduction to a new code thing needs a Hello World, right?

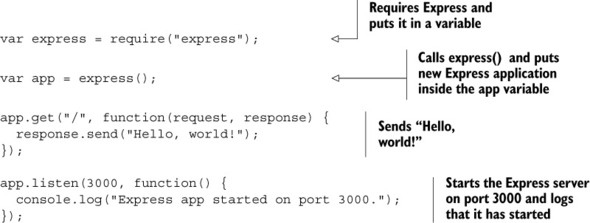

Let’s look at one of the simplest Express applications you can build: the “Hello World.” We’ll delve into this in much greater detail throughout the book, so don’t worry if not all of this makes sense right now. Here’s Hello World in Express.

Listing 1.1. Hello World in Express

Once again, if not all of this makes sense to you, don’t worry. But you might be able to see that you’re creating an Express application, defining a route that responds with “Hello, world!”, and starting your app on port 3000. There are a few steps you’ll need to do to run this—all of that will become clear in the next couple of chapters.

You’ll learn all of Express’s secrets soon.

1.7. Summary

- Node.js is a powerful tool for writing web applications, but it can be cumbersome to do so. Express was made to smooth out that process.

- Express is a minimal, unopinionated framework that’s flexible.

- Express has a few key features:

- Middleware which is a way to break your app into smaller bits of behavior. Generally, middleware is called one by one, in a sequence.

- Routing similarly breaks your app up into smaller functions that are executed when the user visits a particular resource; for example, showing the homepage when the user requests the homepage URL.

- Routers can further break up large applications into smaller, composable subapplications.

- Most of your Express code involves writing request handler functions, and Express adds a number of conveniences when writing these.