In this chapter we are going to study two models of computations: finite state machines and stack machines.

Model of computation is akin to the language you are using to describe the solution to a problem. Typically, a problem that is really hard to solve correctly in one model of computation can be close to trivial in another. This is the reason programmers who are knowledgeable about many different models of computations can be more productive. They solve problems in the model of computation that is most suitable and then they implement the solution with the tools they have at their disposal.

When you are trying to learn a new model of computation, do not think about it from the “old” point of view, like trying to think about finite state machines in terms of variables and assignments. Try to start fresh and logically build the new system of notions.

We already know much about Intel 64 and its model of computation, derived from von Neumann’s. This chapter will introduce finite state machines (used to implement regular expressions) and stack machines akin to the Forth machine.

7.1 Finite State Machines

7.1.1 Definition

Deterministic finite state machine (deterministic finite automaton) is an abstract machine that acts on input string, following some rules.

We will use “Finite automatons” and “state machines” interchangeably. To define a finite automaton, the following parts should be provided:

A set of states.

Alphabet—a set of symbols that can appear in the input string.

A selected start state.

One or multiple selected end states

Rules of transition between states. Each rule consumes a symbol from input string. Its action can be described as: “if automaton is in state S and an input symbol C occurs, the next current state will be Z.”

If the current state has no rule for the current input symbol, we consider the automaton behavior undefined.

The undefined behavior is a concept known more to mathematicians than to engineers. For the sake of brevity we are describing only the “good” cases. The “bad” cases are of no interest to us, so we are not defining the machine behavior in them. However, when implementing such machines, we will consider all undefined cases as erroneous and leading to a special error state.

Why bother with automatons? Some tasks are particularly easy to solve when applying such paradigm of thinking. Such tasks include controlling embedded devices and searching substrings that match a certain pattern.

For example, we are checking, whether a string can be interpreted as an integer number. Let’s draw a diagram, shown in Figure 7-1. It defines several states and shows possible transitions between them.

The alphabet consists of letters, spaces, digits, and punctuation signs.

The set of states is {A, B, C}.

The initial state is A.

The final state is C.

Figure 7-1. Number recognition

We start execution from the state A. Each input symbol causes us to change current state based on available transitions.

Note

Arrows labeled with symbol ranges like 0. . . 9 actually denote multiple rules. Each of these rules describes a transition for a single input character.

Table 7-1 shows what will happen when this machine is being executed with an input string +34. This is called a trace of execution.

Table 7-1. Tracing a finite state machine shown in Figure 7-1, input is: +34

OLD STATE | RULE | NEW STATE |

|---|---|---|

A | + | B |

B | 3 | C |

C | 4 | C |

The machine has arrived into the final state C. However, given an input idkfa, we could not have arrived into any state, because there are no rules to react to such input symbols. This is where the automaton’s behavior is undefined. To make it total and always arrive in either yes- state or no-state, we have to add one more final state and add rules in all existing states. These rules should direct the execution into the new state in case no old rules match the input symbol.

7.1.2 Example: Bits Parity

We are given a string of zeros and ones. We want to find out whether there is an even or an odd number of ones. Figure 7-2 shows the solver in the form of a finite state machine.

Figure 7-2. Is the number of ones even in the input string?

The empty string has zero ones; zero is an even number. Because of this, the state A is both the starting and the final state.

All zeros are ignored no matter the state. However, each one occurring in input changes the state to the opposite one. If, given an input string, we arrive into the finite state A, then the number of ones is even. If we arrive into the finite state B, then it is odd.

Confusion

In finite state machines, there is no memory, no assignments, no if-then-else constructions. This is thus a completely different abstract machine comparing to the von Neumann’s. There is really nothing but states and transitions between them. In the von Neumann model, the state is the state of memory and register values.

7.1.3 Implementation in Assembly Language

After designing a finite state machine to solve a specific problem, it is trivial to implement this machine in an imperative programming language such as assembly or C.

Following is a straightforward way to implement such machines in assembly:

Make the designed automaton total: every state should possess transition rules for any possible input symbol. If this is not the case, add a separate state to design an error or an answer “no” to the problem being solved.

For simplicity we will call it the else-rule.

Implement a routine to get an input symbol. Keep in mind that a symbol is not necessarily a character: it can be a network packet, a user action, and other kinds of global events.

For each state we should

Create a label.

Call the input reading routine.

Match input symbol with the ones described in transition rules and jump to corresponding states if they are equal.

Handle all other symbols by the else-rule .

To implement the exemplary automaton in assembly, we will make it total first, as shown in Figure 7-3

Figure 7-3. Check if the string is a number: a total automaton

We will modify this automaton a bit to force the input string to be null-terminated, as shown in Figure 7-4. Listing 7-1 shows a sample implementation.

Figure 7-4. Check if the string is a number: a total automaton for a null-terminated string

Listing 7-1. automaton_example_bits.asm

section .text; getsymbol is a routine to; read a symbol (e.g. from stdin); into al

_A:call getsymbolcmp al, '+'je _Bcmp al, '-'je _B; The indices of the digit characters in ASCII; tables fill a range from '0' = 0x30 to '9' = 0x39; This logic implements the transitions to labels; _E and _Ccmp al, '0'jb _Ecmp al, '9'ja _Ejmp _C_B:call getsymbolcmp al, '0'jb _Ecmp al, '9'ja _Ejmp _C_C:call getsymbolcmp al, '0'jb _Ecmp al, '9'ja _Etest al, aljz _Djmp _C_D:; code to notify about success_E:; code to notify about failure

This automaton is arriving into states D or E; the control will be passed to the instructions on either the _D or _E label.

The code can be isolated inside a function returning either 1 (true) in state _D or 0 (false) in state _E.

7.1.4 Practical Value

First of all, there is an important limitation : not all programs can be encoded as finite state machines. This model of computation is not Turing complete, it cannot analyze complex recursively constructed texts, such as XML-code.

C and assembly language are Turing complete, which means that they are more expressive and can be used to solve a wider range of problems.

For example, if the string length is not limited, we cannot count its length or the words in it. Each result would have been a state, and there is only a limited number of states in finite state machines, while the word count can be arbitrary large as well as the strings themselves.

Question 114

Draw a finite state machine to count the words in the input string. The input length is no more than eight symbols.

The finite state machines are often used to describe embedded systems, such as coffee machines. The alphabet consists of events (buttons pressed); the input is a sequence of user actions.

The network protocols can often also be described as finite state machines. Every rule can be annotated with an optional output action: “if a symbol X is read, change state to Y and output a symbol Z.” The input consists of packets received and global events such as timeouts; the output is a sequence of packets sent.

There are also several verification techniques , such as model checking, that allow one to prove certain properties of finite automatons—for example, “if the automaton has reached the state B, he will never reach the state C.” Such proofs can be of a great value when building systems required to be highly reliable.

Question 115

Draw a finite state machine to check whether there is an even or an odd number of words in the input string.

Question 116

Draw and implement a finite state machine to answer whether a string should be trimmed from left, right, or both or should not be trimmed at all. A string should be trimmed if it starts or ends with consecutive spaces.

7.1.5 Regular Expressions

Regular expressions are a way to encode finite automatons. They are often used to define textual patterns to match against. It can be used to search for occurences of a specific pattern or to replace them. Your favorite text editor probably implements them already.

There are a number of regular expressions dialects. We will take as an example a dialect akin to one used in the egrep utility.

A regular expression R can be:

A letter.

A sequence of two regular expressions: R Q.

Metasymbols ˆ and $, matching against the beginning and the end of the line.

A pair of grouping parentheses with a regular expression inside: (R).

An OR expression: R | Q.

R* denotes zero or more repetitions of R.

R+ denotes one or more repetitions of R.

R? denotes zero or one repetitions of R.

A dot matches against any character.

Brackets denote a range of symbols, for example [0-9] is an equivalent of (0|1|2|3|4|5|6|7|8|9).

You can test regular expressions using the egrep utility. It process its standard input and filters only those lines that match a given pattern. To prevent the from being processed by the shell, enclose it in single quotes like this: egrep 'expression'.

Following are some examples of simple regular expressions:

hello .+ matches against hello Frank or hello 12; does not match against hello.

[0-9]+ matches against an unsigned integer, possibly starting with zeros.

-?[0-9]+ matches against a possibly negative integer, possibly starting with zeros.

0|(-?[1-9][0-9]*) matches against any integer that does not start with zero (unless it is zero).

These rules allow us to define a complex search pattern. The regular expressions engine will try to match the pattern starting with every position in text.

The regular expression engines usually follow one of these two approaches:

Using a straightforward approach, trying to match all described symbol sequences. For example, matching a string ab against regular expression aa?a?b may result in such sequence of events:

Trying to match against aaab — failure.

Trying to match against aab — failure.

Trying to match against ab — success.

So, we are trying out different branches of decisions until we hit a successful one or until we see definitively that all options lead to a failure.

This approach is usually quite fast and also simple to implement. However, there is a worst-case scenario in which the complexity starts growing exponentially. Imagine matching a string:

aaa...a (repeat a n times)

against a regular expression:

a?a?a?...a?aaa...a (repeat a? n times, then repeat a n times)

The given string will surely match the regular expression. However, when applying a straightforward approach the engine will have to go through all possible strings that do match this regular expression. To do it, it will consider two possible options for each a? expression, namely, those containing a and those not containing it. There will be 2n such strings. It is as many as there are subsets in a set of n elements. You do not need more symbols than there are in this line of text to write a regular expression, which a modern computer will evaluate for days or even years. Even for a length n = 50 the number of options will hit 250 = 1125899906842624 options.

Such regular expressions are called “pathological” because due to the matching algorithm nature they are handled extremely slowly.

Constructing a finite state machine based on a regular expression.

It is usually a NFA (Non-deterministic Finite Automaton). As opposed to DFA (Deterministic Finite Automaton), they can have multiple rules for the same state and input symbol. When such a situation occurs, the automaton performs both transitions and now has several states simultaneously. In other words, there is no single state but a set of states an automaton is in.

This approach is a bit slower in general but has no worst-case scenario with exponential working time. Standard Unix utilities such as grep are using this approach.

How to build a NFA from a regular expression? The rules are pretty straightforward:

A character corresponds to an automaton, which accepts a string of one such character, as shown in Figure 7-5.

Figure 7-5. NFA for one character

We can enlarge the alphabet with additional symbols, which we put in the beginning and end of each line.

This way we handle ˆ and $ just as any other symbol.

Grouping parentheses allow one to apply rules to the symbol groups. They are only used for correct regular expression parsing. In other words, they provide the structural information needed for a correct automaton construction.

OR corresponds to combining two NFAs by merging their starting state. Figure 7-5 illustrates the idea.

Figure 7-6. Combining NFAs via OR

An asterisk has a transition to itself and a special thing called ϵ-rule. This rule occurs always. Figure 7-7 shows the automaton for an expression a*b.

Figure 7-7. NFA: implementing asterisk

? is implemented in a similar fashion to *. R+ is encoded as RR*.

Question 117

Using any language you know, implement a grep analogue based on NFA construction. You can refer to [11] for additional information.

Question 118

Study this regular expression: ˆ1?$|ˆ(11+?)\1+$. What might be its purpose? Imagine that the input is a string consisting of characters 1 uniquely. How does the result of this regular expression matching correlate with the string length?

7.2 Forth Machine

Forth is a language created by Charles Moore in 1971 for the 11-meter radio telescope operated by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) at Kitt Peak, Arizona. This system ran on two early minicomputers joined by a serial link. Both a multiprogrammed system and a multiprocessor system (in that both computers shared responsibility for controlling the telescope and its scientific instruments), it was controlling the telescope, collecting data, and supporting an interactive graphics terminal to interact with the telescope and analyze recorded data.

Today, Forth rests a unique and interesting language, both entertaining to learn and a great thing to change the perspective. It is still used, mostly in embedded software, due to an amazing level of interactivity. Forth can also be quite efficient.

Forth interpreters can be seen in such places as

FreeBSD loader.

Robot firmwares.

Embedded software (printers).

Space ships software.

It is thus safe to call Forth a system programming language.

It is not hard to implement Forth interpreter and compiler for Intel 64 in assembly language. The rest of this chapter will explain the details. There are almost as many Forth dialects as Forth programmers; we will use our own simple dialect.

7.2.1 Architecture

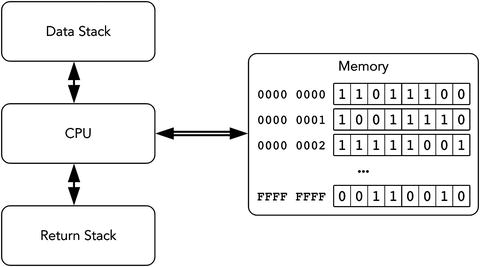

Let’s start by studying a Forth abstract machine. It consists of a processor, two separate stacks for data and return addresses, and linear memory, as shown in Figure 7-8.

Figure 7-8. Forth machine: architecture

Stacks should not necessarily be part of the same memory address space.

The Forth machine has a parameter called cell size. Typically, it is equal to the machine word size of the target architecture. In our case, the cell size is 8 bytes. The stack consists of elements of the same size.

Programs consist of words separated by spaces or newlines. Words are executed consecutively. The integer words denote pushing into the data stack. For example, to push numbers 42, 13, and 9 into the data stack you can write simply 42 13 9.

There are three types of words:

Integer words, described previously.

Native words, written in assembly.

Colon words, written in Forth as a sequence of other Forth words.

The return stack is necessary to be able to return from the colon words, as we will see later.

Most words manipulate the data stack. From now on when speaking about the stack in Forth we will implicitly consider the data stack unless specified otherwise.

The words take their arguments from the stack and push the result there. All instructions operating on the stack consume their operands. For example, words +, -, *, and / consume two operands from the stack, perform an arithmetic operation, and push its result back in the stack. A program 1 4 8 8 + * + computes the expression (8 + 8) * 4 + 1.

We will follow the convention that the second operand is popped from the stack first. It means that the program '1 2 -' evaluates to −1, not 1.

The word : is used to define new words. It is followed by the new word’s name and a list of other words terminated by the word ;. Both semicolon and colon are words on their own and thus should be separated by spaces.

A word sq, which takes an argument from the stack and pushes its square back, will look as follows:

: sq dup * ;Each time we use sq in the program, two words will be executed: dup (duplicate cell in top of the stack) and * (multiply two words on top of the stack).

To describe the word’s actions in Forth it is common to use stack diagrams:

swap (a b -- b a)In parentheses you see the stack state before and after word execution. The stack cells are names to highlight the changes in stack contents. So, the swap word swaps two topmost elements in stack.

The topmost element is on the right, so the diagram 1 2 corresponds to Forth pushing first 1, then 2 as a result of execution of some words.

rot places on top the third number from stack:

rot (a b c -- b c a)7.2.2 Tracing an Exemplary Forth Program

Listing 7-2 shows a simple program to calculate the discriminant of a quadratic equation 1x 2 + 2x + 3 = 0.

Listing 7-2. forth_discr

: sq dup * ;: discr rot 4 * * swap sq swap - ;1 2 3 discr

Now we are going to execute discr a b c step by step for some numbers a, b, and c. The stack state at the end of each step is shown on the right.

a ( a )b ( a b )c ( a b c )

Then the discr word is executed. We are stepping into it.

rot ( b c a )4 ( b c a 4 )* ( b c (a*4) )* ( b (c*a*4) )swap ( (c*a*4) b )sq ( (c*a*4) (b*b) )swap ( (b*b) (c*a*4) )- ( (b*b - c*a*4) )

Now we do the same from the start, but for a = 1, b = 2, and c = 3.

1 ( 1 )2 ( 1 2 )3 ( 1 2 3 )rot ( 2 3 1 )4 ( 2 3 1 4 )* ( 2 3 4 )* ( 2 12 )swap ( 12 2 )sq ( 12 4 )swap ( 4 12 )- ( -8 )

7.2.3 Dictionary

A dictionary is a part of a Forth machine that stores word definitions. Each word is a header followed by a sequence of other words.

The header stores the link to the previous word (as in linked lists), the word name itself as a null-terminated string, and some flags. We have already studied a similar data structure in the assignment, described in section 5.4. You can reuse a great part of its code to facilitate defining new Forth words. See Figure 7-9 for the word header generated for the discr word described in section 7.2.2

Figure 7-9. Word header for discr

7.2.4 How Words Are Implemented

There are three ways to implement words .

Indirect threaded code

Direct threaded code

Subroutine threaded code

We are using a classic indirect threaded code way. This type of code needs two special cells (which we can call Forth registers):

PC points at the next Forth command. We will see soon that the Forth command is an address of an address of the respective word’s assembly implementation code. In other words, this is a pointer to an executable assembly code with two levels of indirection.

W is used in non-native words. When the word starts its execution, this register points at its first word.

These two registers can be implemented through a real register usage. Alternatively, their contents can be stored in memory.

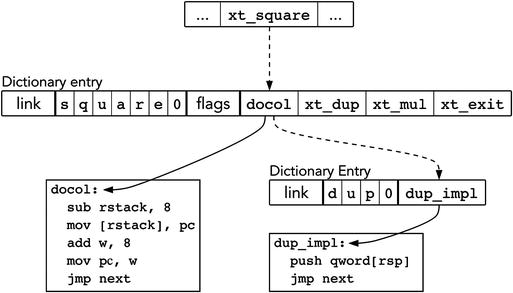

Figure 7-10 shows how words are structured when using the indirect threaded code technique . It incorporates two words: a native word dup and a colon word square.

Figure 7-10. Indirect threaded code

Each word stores the address of its native implementation (assembly code) immediately after the header. For colon words the implementation is always the same: docol. The implementation is called using the jmp instruction.

Execution token is the address of this cell, pointing to an implementation. So, an execution token is an address of an address of the word implementation. In other words, given the address A of a word entry in the dictionary, you can obtain its execution token by simply adding the total header size to A.

Listing 7-3 provides us with a sample dictionary. It contains two native words (starting at w_plus and w_dup) and a colon word (w_sq).

Listing 7-3. forth_dict_sample.asm

section .dataw_plus:dq 0 ; The first word's pointer to the previous word is zerodb '+',0db 0 ; No flagsxt_plus: ; Execution token for `plus`, equal to; the address of its implementationdq plus_implw_dup:dq w_plusdb 'dup', 0db 0xt_dup:dq dup_implw_double:dq w_dupdb 'double', 0db 0dq docol ; The `docol` address -- one level of indirectiondq xt_dup ; The words consisting `dup` start here.dq xt_plusdq xt_exitlast_word: dq w_doublesection .textplus_impl:pop raxadd rax, [rsp]mov [rsp], raxjmp nextdup_impl:push qword [rsp]jmp next

The core of the Forth engine is the inner interpreter. It is a simple assembly routine fetching code from memory. It is shown in Listing 7-4.

Listing 7-4. forth_next.asm

next:mov w, pcadd pc, 8 ; the cell size is 8 bytesmov w, [w]jmp [w]

It does two things:

It reads memory starting at PC and sets up PC to the next instruction. Remember, that PC points to a memory cell, which stores execution token of a word.

It sets up W to the execution token value. In other words, after next is executed, W stores the address of a pointer to assembly implementation of the word.

Finally, it jumps to the implementation code.

Every native word implementation ends with the instruction jmp next. It ensures that the next instruction will be fetched.

To implement colon words we need to use a return stack in order to save and restore PC before and after a call.

While W is not useful when executing native words, it is quite important for the colon words. Let us take a look at docol, the implementation of all colon words, shown in Listing 7-5 It also features exit, another word designed to end all colon words.

Listing 7-5. forth_docol.asm

docol:sub rstack, 8mov [rstack], pcadd w, 8 ; 8mov pc, wjmp nextexit:mov pc, [rstack]add rstack, 8jmp next

docol saves PC in the return stack and sets up new PC to the first execution token stored inside the current word. The return is performed by exit, which restores PC from the stack.

This mechanism is akin to a pair of instructions call/ret.

Question 119

Read [32]. What is the difference between our approach (indirect threaded code) and direct threaded code and subroutine threaded code? What advantages and disadvantages can you name?

To better grasp the concept of an indirect threaded code and the innards of Forth, we prepared a minimal example shown in Listing 7-6. It uses routines developed in the first assignment from section 2.7.

Take your time to launch it (the source code is shipped with the book) and check that it really reads a word from input and outputs it back.

Listing 7-6. itc.asm

%include "lib.inc"global _start%define pc r15%define w r14%define rstack r13section .bssresq 1023rstack_start: resq 1input_buf: resb 1024section .text; this one cell is the programmain_stub: dq xt_main; The dictionary starts here; The first word is shown in full; Then we omit flags and links between nodes for brevity; Each word stores an address of its assembly implementation; Drops the topmost element from the stackdq 0 ; There is no previous nodedb "drop", 0db 0 ; Flags = 0xt_drop: dq i_dropi_drop:add rsp, 8jmp next; Initializes registersxt_init: dq i_initi_init:mov rstack, rstack_startmov pc, main_stubjmp next; Saves PC when the colon word startsxt_docol: dq i_docoli_docol:sub rstack, 8mov [rstack], pcadd w, 8mov pc, wjmp next; Returns from the colon wordxt_exit: dq i_exiti_exit:mov pc, [rstack]add rstack, 8jmp next; Takes a buffer pointer from stack; Reads a word from input and stores it; starting in the given bufferxt_word: dq i_wordi_word:pop rdicall read_wordpush rdxjmp next; Takes a pointer to a string from the stack; and prints itxt_prints: dq i_printsi_prints:pop rdicall print_stringjmp next; Exits programxt_bye: dq i_byei_bye:mov rax, 60xor rdi, rdisyscall; Loads the predefined buffer addressxt_inbuf: dq i_inbufi_inbuf:push qword input_bufjmp next; This is a colon word, it stores; execution tokens. Each token; corresponds to a Forth word to be; executedxt_main: dq i_docoldq xt_inbufdq xt_worddq xt_dropdq xt_inbufdq xt_printsdq xt_bye; The inner interpreter. These three lines; fetch the next instruction and start its; executionnext:mov w, [pc]add pc, 8jmp [w]; The program starts execution from the init word_start: jmp i_init

7.2.5 Compiler

Forth can work in either interpreter or compiler mode. Interpreter just reads commands and executes them.

When executing the colon : word, Forth switches into compiler mode. Additionally, the colon : reads one next word and uses it to create a new entry in the dictionary with docol as implementation. Then Forth reads words, locates them in dictionary, and adds them to the current word being defined.

So, we have to add another variable here, which stores the address of the current position to write words in compile mode. Each write will advance here by one cell.

To quit compiler mode we need special immediate words. They are executed no matter which mode we are in. Without them we would never be able to exit compiler mode. The immediate words are marked with an immediate flag.

The interpreter puts numbers in the stack. The compiler cannot embed them in words directly, because otherwise they will be treated as execution tokens. Trying to launch a command by an execution token 42 will most certainly result in a segmentation fault. However, the solution is to use a special word lit followed by the number itself. The lit’s purpose is to read the next integer that PC points at and advance PC by one cell further, so that PC will never point at the embedded operand.

7.2.5.1 Forth Conditionals

We will make two words stand out in our Forth dialect: branch n and 0branch n. They are only allowed in compilation mode!

They are similar to lit n because the offset is stored immediately after their execution token.

7.3 Assignment: Forth Compiler and Interpreter

This section will describe a big assignment: writing your own Forth interpreter.

Before we start, make sure you have understood the Forth language basics. If you are not certain of it, you can play around with any free Forth interpreter, such as gForth.

Question 120

Look the documentation for commands sete, setl, and their counterparts.

Question 121

What does cqo instruction do? Refer to [15].

It is convenient to store PC and W in some general purpose registers, especially the ones that are guaranteed to survive function calls unchanged ( caller-saved ): r13, r14, or r15.

7.3.1 Static Dictionary, Interpreter

We are going to start with a static dictionary of native words. Adapt the knowledge you received in section 5.4. From now on we cannot define new words in runtime.

For this assignment we will use the following macro definitions:

native, which accepts three arguments:

Word name;

A part of word identifier; and

Flags.

It creates and fills in the header in .data and a label in .text. This label will denote the assembly code following the macro instance.

As most words will not use flags, we can overload native to accept either two or three arguments. To do it, we create a similar macro definition which accepts two arguments and launches native with three arguments, the third being substituted by zero and the first two passed as-is, as shown in Listing 7-7.

Listing 7-7. native_overloading. asm

%macro native 2native %1, %2, 0%endmacro

Compare two ways of defining Forth dictionary: without macros (shown in Listing 7-8) and with them (shown in Listing 7-9).

Listing 7-8. forth_dict_example_nomacro.asm

section .dataw_plus:dq w_mul ; previousdb '+',0db 0xt_plus:dq plus_implsection .textplus_impl:pop raxadd [rsp], raxjmp next

Listing 7-9. forth_dict_example_macro.asm

native '+', pluspop raxadd [rsp], raxjmp next

Then define a macro colon, analogous to the previous one. Listing 7-10 shows its usage.

Listing 7-10. forth_colon_usage.asm

colon '>', greaterdq xt_swapdq xt_lessdq exit

Do not forget about docol address in every colon word! Then create and test the following assembly routines :

find_word, which accepts a pointer to a null-terminated string and returns the address of the word header start. If there is no word with such name, zero is returned.

cfa (code from address), which takes the word header start and skips the whole header till it reaches the XT value.

Using these two functions and the ones you have already written in section 2.7, you can write an interpreter loop. The interpreter will either push a number into the stack or fill the special stub, consisting of two cells, shown in Listing 7-11.

It should write the freshly found execution token to program_stub. Then it should point PC at the stub start and jump to next. It will execute the word we have just parsed, and then pass control back to interpreter.

Remember, that an execution token is just an address of an address of an assembly code . This is why the second cell of the stub points at the third, and the third stores the interpreter address—we simply feed this data to the existing Forth machinery.

Listing 7-11. forth_program_stub.asm

program_stub: dq 0xt_interpreter: dq .interpreter.interpreter: dq interpreter_loop

Figure 7-11 shows the pseudo code illustrating interpreter logic.

Figure 7-11. Forth interpreter: pseudocode

Remember that the Forth machine also has memory. We are going to pre-allocate 65536 Forth cells for it.

Question 122

Should we allocate these cells in .data section, or are there better options?

To let Forth know where the memory is, we are going to create the word mem, which will simply push the memory starting address on top of the stack.

7.3.1.1 Word list

You should first make an interpreter that supports the following words :

.S – prints all stack contents; does not change it. To implement it, save rsp before interpreter start.

Arithmetic: + - * /, = <. The comparison operations push either 1 or 0 on top of the stack.

Logic: and, not. All non-zero values are considered true; zero value is considered false. In case of success these instructions push 1, otherwise 0. They also destruct their operands.

Simple stack manipulations:

rot (a b c -- b c a)swap (a b -- b a)dup (a -- a a)drop (a -- ). ( a -- ) pops the number from the stack and outputs it.

Input/output:

key ( -- c)—reads one character from stdin; The top cell in stack stores 8 bytes, it is a zero extended character code.

emit ( c -- )—writes one symbol into stdout.

number ( -- n )—reads a signed integer number from stdin (guaranteed to fit into one cell).

mem—stores the user memory starting address on top of the stack.

Working with memory :

! (address data -- )—stores data from stack starting at address.

c! (address char -- )—stores a single byte by address.

@ (address -- value)—reads one cell starting from address

c@ (address -- charvalue)—reads a single byte starting from address Then test the resulting interpreter.

Then create a memory region for the return stack and implement docol and exit. We recommend allocating a register to point at the return stack’s top.

Implement colon-words or and greater using macro colon and test them.

7.3.2 Compilation

Now we are going to implement compilation . It is easy!

We need to allocate other 65536 Forth cells for the extensible part of the dictionary.

Add a variable state, which is equal to 1 when in compilation mode, 0 for interpretation mode.

Add a variable here, which points at the first free cell in the preallocated dictionary space.

Add a variable last_word, which stores the address of the last word defined.

Add two new colon words, namely, : and ;.

Colon:

1: word ← stdin

2: Fill the new word’s header starting at here. Do not forget to update it!

3: Add docol address immediately at here; update here.

4: Update last_word.

5: state ← 1;

6: Jump to next.

Semicolon should be marked as Immediate !

1: here ← XT of the word exit ; update here.

2: state ← 0;

3: Jump to next.

Here is what the compiler loop looks like. You can implement it separately, or mix with interpreter loop you already implemented.

1: compiler loop :

2: word ← word from stdin

3: if word is empty then

4: exit

5: if word is present and has address addr then

6: xt ← cf a(addr)

7: if word is marked Immediate then

8: interpret word

9: else

10: [here] ← xt

11: here ← here + 8

12: else

13: if word is a number n then

14: if previous word was branch or 0branch then

15: [here] ← n

16: here ← here + 8

17: else

18: [here] ← xt lit

19: here ← here + 8

20: [here] ← n

21: here ← here + 8

22: else

23: Error: unknown word

Implement 0branch and branch and test them (refer to section 7.3.3 for a complete list of Forth words with their meanings).

Question 123

Why do we need a separate case for branch and 0branch?

7.3.3 Forth with Bootstrap

We can divide the Forth interpreter into two parts. The very necessary one is called inner interpreter ; it is written in assembly . Its purpose is to fetch the next XT from memory. This is the next routine, shown in Listing 7-4.

The other part is the outer interpreter , which accepts user input and either compiles the word to the current definition or executes it right away. The exciting thing about it is that this interpreter can be defined as a colon word. In order to accomplish that we have to define some additional Forth words.

We have created Forthress, a Forth dialect described in this chapter. The interpreter and compiler are shipped with this book as well. Here is the full set of words known to Forthress.

drop( a -- )

swap( a b -- b a )

dup( a -- a a )

rot( a b c -- b c a )

Arithmetic:

+ ( y x -- [ x + y ] )

* ( y x -- [ x * y ] )

/ ( y x -- [ x / y ] )

% ( y x -- [ x mod y ] )

- ( y x -- [x - y] )

Logic :

not( a -- a' ) a’ = 0 if a != 0 a’ = 1 if a == 0

=( a b -- c ) c = 1 if a == b c = 0 if a != b

count( str -- len ) Accepts a null-terminated string, calculates its length.

. Drops element from stack and sends it to stdout.

.S Shows stack contents. Does not pop elements.

init Stores the data stack base. It is useful for .S.

docol This is the implementation of any colon word. The XT itself is not used, but the implementation (known as docol) is.

exit Exit from colon word.

>r Push from return stack into data stack.

r> Pop from data stack into return stack.

r@ Non-destructive copy from the top of return stack to the top of data stack.

find( str -- header addr ) Accepts a pointer to a string, returns pointer to the word header in dictionary.

cfa( word addr -- xt ) Converts word header start address to the execution token.

emit( c -- ) Outputs a single character to stdout.

word( addr -- len ) Reads word from stdin and stores it starting at address addr. Word length is pushed into stack.

number ( str -- num len) Parses an integer from string.

prints ( addr -- ) Prints a null-terminated string.

bye Exits Forthress

syscall ( call num a1 a2 a3 a4 a5 a6 -- new rax ) Executes syscall The following regis- ters store arguments (according to ABI) rdi, rsi, rdx, r10, r8, and r9.

branch <offset> Jump to a location. Location is an offset relative to the argument end For example:

|branch| 24 | <next command>ˆ branch adds 24 to this address and stores it in PC0branch <offset> Branch is a compile-only word. Jump to a location if TOS = 0. Location is calculated in a similar way. 0branch is a compile-only word.

lit <value> Pushes a value immediately following this XT.

inbuf Address of the input buffer (is used by interpreter/compiler).

mem Address of user memory.

last word Header of last word address.

state State cell address. The state cell stores either 1 (compilation mode) or 0 (interpretation mode).

here Points to the last cell of the word currently being defined.

execute ( xt -- ) Execute word with this execution token on TOS.

@ ( addr -- value ) Fetch value from memory.

! ( addr val -- ) Store value by address.

@c ( addr -- char ) Read one byte starting at addr.

, ( x -- ) Add x to the word being defined.

c, ( c -- ) Add a single byte to the word being defined.

create ( flags name -- ) Create an entry in the dictionary whose name is the new name. Only immediate flag is implemented ATM.

: Read word from stdin and start defining it.

; End the current word definition

interpreter Forthress interpreter/compiler.

We encourage you to try to build your own bootstrapped Forth. You can start with a working interpreter loop written in Forth. Modify the file itc.asm, shown in Listing 7-6, by introducing the word interpreter and writing it using Forth words only.

7.4 Summary

This chapter has introduced us to two new models of computation: finite state machines (also known as finite automatons) and stack machines akin to the Forth machine. We have seen the connection between finite state machines and regular expressions, used in multiple text editors and other text processing utilities. We have completed the first part of our journey by building a Forth interpreter and compiler, which we consider a wonderful summary of our introduction to assembly language. In the next chapter we are going to switch to the C language to write higher-level code. Your knowledge of assembly will serve as a foundation for your understanding of C because of how close its model of computation is to the classical von Neumann model of computation.

Question 124

What is a model of computation?

Question 125

Which models of computation do you know?

Question 126

What is a finite state machine?

Question 127

When are the finite state machines useful?

Question 128

What is a finite automaton?

Question 129

What is a regular expression?

Question 130

How are regular expressions and finite automatons connected?

Question 131

What is the structure of the Forth abstract machine?

Question 132

What is the structure of the dictionary in Forth?

Question 133

What is an execution token?

Question 134

What is the implementation difference between embedded and colon words?

Question 135

Why are two stacks used in Forth?

Question 136

Which are the two distinct modes that Forth is operating in?

Question 137

Why does the immediate flag exist?

Question 138

Describe the colon word and the semicolon word.

Question 139

What is the purpose of PC and W registers?

Question 140

What is the purpose of next?

Question 141

What is the purpose of docol?

Question 142

What is the purpose of exit?

Question 143

When an integer literal is encountered, do interpreter and compiler behave alike?

Question 144

Add an embedded word to check the remainder of a division of two numbers. Write a word to check that one number is divisible by another.

Question 145

Add an embedded word to check the remainder of a division of two numbers. Write a word to check the number for primarity.

Question 146

Write a Forth word to output the first n number of the Fibonacci sequence.

Question 147

Write a Forth word to perform system calls (it will take the register contents from stack). Write a word that will print “Hello, world!” in stdout.