Chapter 5 already provided a short overview of dynamic libraries (also known as shared objects). This chapter will revisit dynamic libraries and expand our knowledge by introducing the concepts of the Program Linkage Table and the Global Offset Table. As a result, we will be able to build a shared library in pure assembly and C, compare the results, and study its structure. We will also study a concept of code models, which is rarely discussed but gives a consistent view of several important details of assembly code generation.

15.1 Dynamic Loading

As you might remember, an ELF (Executable and Linkable Format) file contains three headers:

The main header, located at an offset zero. It defines the general information about the file, including the entry point and offsets to two tables elaborated below.

You can view it using the readelf -h command.

Section headers table, which contains information about different ELF sections.

You can view it using the readelf -S command.

Program headers table, which contains information about the file segments. Each segment is a runtime structure, which contains one or more sections, defined in the section headers table.

You can view it using the readelf -l command.

The initial stage of loading an executable is to create an address space and perform memory mappings according to the program headers table with appropriate permissions. This is performed by the operating system kernel. Once the virtual address space is set, the other program has to interfere (i.e., dynamic loader). The latter should be an executable program, and fully relocatable (so it should be able to be loaded at whatever address we want).

The purpose of the dynamic linker is to

Determine all dependencies and load them.

Perform relocation of the applications and dependencies.

Initialize the application and its dependencies and pass the control to the application. Now, the program execution will start.

Determining dependencies and loading them is relatively easy: it boils down to searching dependencies recursively and checking whether the object has been already loaded or not. Initializing is also not very mystified. The relocation, however, is of interest to us.

There are two kinds of relocations :

Links to locations in the same object. The static linker is performing all such relocations since they are known at the link time.

Symbol dependencies, which are usually in the different object.

The second kind of relocation is more costly and is performed by the dynamic linker.

Before doing relocations , we need to do a lookup first to find the symbols we want to link. There is a notion of lookup scope of an object file, which is an ordered list containing some other loaded objects. The lookup scope of an object file is used to resolve symbols necessary for it. The way it is computed is described in [24] and is rather complex, so we refer you to the relevant document in case of need.

The lookup scope consists of three parts, which are listed in reverse order of search—that is, the symbol gets searched in the third part of the scope first.

Global lookup scope, which consists of the executable file and all its dependencies, including dependencies of the dependencies, etc. They are enumerated in a breadth-first search fashion, that is:

The executable itself.

Its dependencies.

The dependencies of its first dependency, then of the second, etc. Each object is loaded only once.

The part constructed if DF_SYMBOLIC flag is set in the ELF executable file metadata. It is considered legacy; its usage is discouraged, so we are not studying it here.

Objects loaded dynamically with all their dependencies by means of dlopen function call. They are not searched for normal lookups.

Each object file contains a hash table which is used for lookup.1 This table stores the symbol information and is used to quickly find the symbol by its name. The first object in the lookup scope, which contains the needed symbol, is linked, which allows for symbol overloading—for example, using LD_PRELOAD mechanism—which will be explored in section 15.5.

The hash table size and the number of exported symbols are affecting the lookup time. When the -O flag for linker is provided,2 it tries to optimize these parameters for better lookup speed. Remember, that in languages such as C++, not only are the symbol names computed based on, for example, function name, but they have all their namespaces (and classname) encoded, which may easily result in names of several hundred characters. In the case of collisions in hash tables (which are usually frequent), the string comparison should be performed between the symbol name we are looking for and all symbols in the bucket we have chosen by computing its hash.

The modern GNU-style hash tables provide an additional heuristic of using a Bloom filter3 in order to quickly answer a question: “is this symbol even defined in this object file?” That makes unnecessary lookups much less frequent, which positively impacts performance.

15.2 Relocations and PIC

Now, what kind of relocations are performed? We have seen the process of relocations during static linking in Chapter 5. Can we do the same, relocating all code and data elements? The answer is yes, we can, and until common architectures added special features to ease the position-independent code writing, it was extensively used. However, this approach has the following drawbacks:

Relocations are slow to perform, especially when dependencies are numerous. That can delay the startup of the application.

The . text section cannot be shared, because it has to be patched. While static linking implies patching object file contents when building the final object file, dynamic linking implies patching object files in memory. Not only does it waste memory, it also poses a security risk, because, for example, shellcode can rewrite the program in memory directly to alter its behavior.

Nowadays, PIC is the recommended way, and it allows to keep .text read-only (while .data cannot be shared anyway).

The number of relocations will be smaller, because no code relocations will be performed. PIC implies using two utility tables:Global Offset Table (GOT) and Program Linkage Table (PLT).

15.3 Example: Dynamic Library in C

Before we start studying GOT and PLT, let us create a minimal working example of a dynamic library in C. It is actually quite easy.

Our program will consist of two files: mainlib.c (shown in Listing 15-1) and dynlib.c (shown in Listing 15-2).

Listing 15-1. mainlib.c

extern void libfun( int value );int global = 100;int main( void ) {libfun( 42 );return 0;}

Listing 15-2. dynlib.c

#include <stdio.h>extern int global;void libfun(int value) {printf( "param: %d\n", value );printf( "global: %d\n", global );}

As we see, there is a global variable in the main file, which we will want to share with the library; the library explicitly states that it is extern. The main file has the declaration of the library function (which is usually placed in the header file, shipped with the compiled library).

To compile these files, the following commands should be issued:

> # creating object file for the main part> gcc -c -o mainlib.o mainlib.c> # creating object file for the library> gcc -c -fPIC -o dynlib.o dynlib.c> gcc -o dynlib.so -shared dynlib.o # creating dynamic library itself> # creating an executable and linking it with the dynamic library> gcc -o main mainlib.o dynlib.so

First, we create object files as usual. Then we build the dynamic library using -shared flag. When we build an executable, we provide all dynamic libraries from which it depends, because this information should be included in ELF metadata. Notice the usage of -fPIC flag, which forces to generate position-independent code. We will see the effects of this flag on assembly later.

Let’s check the file dependencies using ldd.

> ldd mainlinux-vdso.so.1 => (0x00007fffcd428000)lib.so => not foundlibc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007ff988d60000)/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007ff989200000)

Our fresh library is present in the list of dependencies, but ldd cannot find it. An attempt to launch the executable fails with the expected message:

./main: error while loading shared libraries:lib.so: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

The libraries are searched in the default locations (such as /lib/). Ours is not there, so we have another option: an environment variable LD_LIBRARY_PATH is parsed to get a list of additional directories where the libraries might be located. As soon as we set it to the current directory, ldd finds the library. Note, that the search starts with the directories defined in LD_LIBRARY_PATH and proceeds to the standard directories.

> export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=.> ldd mainlinux-vdso.so.1 => (0x00007ffff1315000)lib.so => ./lib.so (0x00007f3a7bc70000)libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007f3a7b890000)/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f3a7c000000)

The launch produces expected results.

> ./mainparam: 42global: 100

15.4 GOT and PLT

15.4.1 Accessing External Variables

To keep .text read-only and never patch it due to relocations, we add a level of indirection when addressing any symbol that is not guaranteed to be defined in the same object—in other words, for every symbol defined in executable or shared object file after the static linking. This indirection is performed through a special Global Offset Table.

Two facts are important to make PIC code work.

Intel 64 makes it possible to address instruction operands relative to rip register. It is possible to get the current rip value using a pair of call and pop instructions, but the hardware support surely helps performance-wise.

The offset between the .text section and .data section is known at link time, that is, when the dynamic library is being created. It also means that the distance between rip and the beginning of the .data section is also known. So, we place the Global Offset Table in the .data section or near it. It will hold the absolute addresses of global variables.

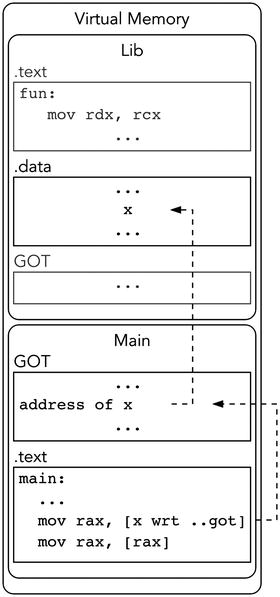

We address the GOT cell relatively to rip and get an absolute address of the global variable from there—see Figure 15-1.

Figure 15-1. Accessing global variable through GOT

Let’s see, how the variable global, created in the main executable file, is addressed in the dynamic library. To do it, we are going to study a fragment of objdump -D -Mintel-mnemonic output, shown in Listing 15-3.

Listing 15-3. libfun

00000000000006d0 <libfun>:# Function prologue6d0: 55 push rbp6d1: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp6d4: 48 83 ec 10 sub rsp,0x10# Second argument for printf( "param: %d\n", value );6d8: 89 7d fc mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x4],edi6db: 8b 45 fc mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x4]6de: 89 c6 mov esi,eax# First argument for printf( "param: %d\n", value );6e0: 48 8d 3d 32 00 00 00 lea rdi,[rip+0x32]# Printf call; no XMM registers used6e7: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x06ec: e8 bf fe ff ff call 5b0 <printf@plt># Second argument for printf( "global: %d\n", global );6f1: 48 8b 05 e0 08 20 00 mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x2008e0]6f8: 8b 00 mov eax,DWORD PTR [rax]6fa: 89 c6 mov esi,eax# First argument for printf( "global: %d\n", global );6fc: 48 8d 3d 21 00 00 00 lea rdi,[rip+0x21]# Printf call; no XMM registers used703: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x0708: e8 a3 fe ff ff call 5b0 <printf@plt># Function epilogue70d: 90 nop70e: c9 leave70f: c3 ret

Remember that the source code is shown in Listing 15-2. We are interested in seeing how the global variables are accessed.

First, note that the first argument of printf (which is the address of the format string, residing in .rodata ) is accessed not in a typical way.

In such cases, we used to have an absolute address value (which would have been filled by linker during the relocation, as explained in section 5.3.2). However, here an address relative to rip is used. As we understand, rdi as the first argument should hold the address of the format string. So, this address is stored in memory by the address [rip + 0x32]. This place is a part of GOT.

Now, let’s see, how global is accessed from the dynamic library code. In fact, the mechanism is absolutely the same, though there is a need in one more memory read. First we read the GOT contents in

mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x2008e0]to get the address of global, then we read its value by accessing the memory again in

mov eax,DWORD PTR [rax].Quite simple for global variables. For functions, however, the implementation is a bit more complicated.

15.4.2 Calling External Functions

While the exact same approach could have worked for functions, an additional feature is implemented to perform the lazy, on-demand function lookup. Let us first discuss the reasons for it.

Looking up symbol definitions is not trivial, as we have seen in this chapter. There are usually many more functions than the global variables exported, and only a small fraction of them are actually called during program execution (e.g., error handling functions). In general, when programmers get a dynamic library to use with their program, they often acquire a third-party library which has much more functions than they actually need to call.

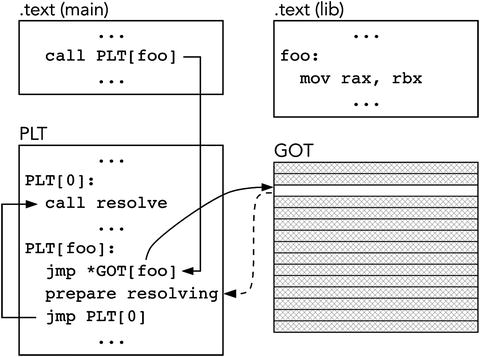

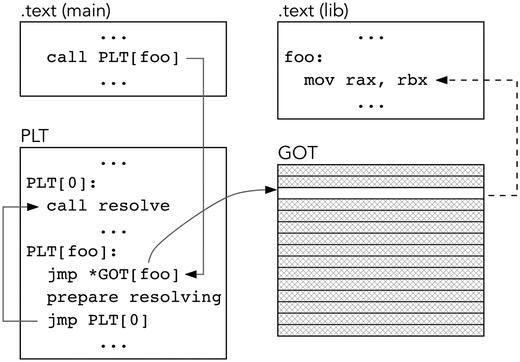

We add another level of indirection through the special Program Linkage Table (PLT). It resides in the .text section. Each function called by the shared library has an entry in PLT. Each entry is a small chunk of executable code, which is linked statically and thus can be called directly. Instead of calling a function, whose address would have been stored in GOT, we call the stub entry for it.

To illustrate it, we sketch a PLT in Listing 15-4.

Listing 15-4. plt_sketch.asm

; somewhere in the programcall func@plt; PLTPLT_0: ; the common partcall resolver...PLT_n: func@plt:jmp [GOT_n]PLT_n_first:; here the arguments for resolver are preparedjmp PLT_0GOT:...GOT_n:dq PLT_n_first

Now, what is happening there?

The function call refers to PLT entry bypassing GOT.

The zero-th PLT entry defines the “common code” of all entries. They all end up jumping to this entry.

An n-th entry starts with the jump to an address, stored in the n-th GOT entry. The default value of this entry is the address of the next instruction after this jump! In our example, it is denoted by the label PLT_n_first. So, the first time the function is called we jump to the next instruction, effectively performing a NOP operation.

This code prepares arguments for the dynamic loader and jumps to the common code in PLT_0.

In PLT_0 the loader is called. It performs lookup and resolves the function address, filling GOT_n with the actual function address.

The next function call will involve no dynamic loader: the PLT_n stub will be called, which will immediately jump to the resolved function, whose address now resides in GOT.

Refer to Figures 15-2 and 15-3 for a schematic of changes in PLT due to symbol resolution process.

Figure 15-2. PLT before linking function in runtime

Figure 15-3. PLT after linking function in runtime

Question 293

Read in man ld.so about environment variables (such as LD_BIND_NOT), which can alter the loader behavior.

15.4.3 PLT Example

To be completely fair, we will study the code generated for the example shown in section 15.3.

The main function calls libfun, which is performed through PLT as we expected.

Disassembly of section .text:00000000004006a6 <main>:push rbpmov rbp,rspmov edi,0x2acall 400580 <libfun@plt>mov eax,0x0pop rbpret

Next, let’s see how PLT looks like. The PLT entry for libfun is called libfun@plt. Find it in Listing 15-5.

Listing 15-5. plt_rw.asm

Disassembly of section .init:0000000000400550 <_init>:sub rsp,0x8mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a9d] # 600ff8 <_DYNAMIC+0x1e0>test rax,raxje 400565 <_init+0x15>call 4005a0 <__libc_start_main@plt+0x10>add rsp,0x8retDisassembly of section .plt:0000000000400570 <libfun@plt-0x10>:push QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a92] # 601008 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x8>jmp QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a94] # 601010 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x10>nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]0000000000400580 <libfun@plt>:imp QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a92] # 601018 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x18>push 0x0jmp 400570 <_init+0x20>0000000000400590 <__libc_start_main@plt>:jmp QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a8a] # 601020 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x20>push 0x1jmp 400570 <_init+0x20>Disassembly of section .got:0000000000600ff8 <.got>:...Disassembly of section .got.plt:0000000000601000 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_>:...

The first instruction is a jump into GOT to its third element (because each entry is 8 bytes long and the offset is 0x18). Then the push instruction is issued, whose operand is the function number in PLT. For libfun it is 0x0, for libc_start_main it is 0x1.

The next instruction in libfun@plt is a jump to _init+0x20, which is strange, but if we check the actual _init address, we will see, that

_init is at 0x400550.

_init+0x20 is at 0x400570.

libfun@plt-0x10 is at 0x400570 as well, so they are the same.

This address is also the start of .plt section and, according to the explanation previously, should correspond to the “common” code shared by all PLT entries. It pushes one more GOT value into the stack and takes an address of the dynamic loader from GOT to jump to it.

The comments issued by objdump show that the last two values refer to addresses 0x601008 and 0x601010. As we see, they should be stored somewhere in .got.plt section, which is the part of GOT related to PLT entries. Listing 16 shows the contents of this section.

Listing 15-6. got_plt_dump_ex.c

Contents of section .got.plt:0x601000 180e6000 00000000 00000000 000000000x601010 00000000 00000000 86054000 000000000x601020 96054000 00000000

By looking carefully we see that starting at the address 0x601018 the following bytes are located:

86 05 40 00 00 00 00 00Remembering the fact that Intel 64 uses little endian, we conclude that the actual quad word stored here is 0x400586, which is really the address of libfun@plt + 6, in other words, the address of the push 0x0 instruction. That illustrates the fact that the initial values for functions in GOT point at the second instructions of their respective PLT entries.

15.5 Preloading

Setting up the LD_PRELOAD variable allows you to preload shared objects before any other library (including the C standard library). The functions from this library will have a priority lookup-wise, so they can override the functions defined in the normally loaded shared objects.

The dynamic loader ignores the LD_PRELOAD value if the effective user ID and the real user ID do not match. This is done for security reasons.

We are going to write and compile a simple program, shown in Listing 15-7.

Listing 15-7. preload_launcher.c

#include <stdio.h>int main(void) {puts("Hello, world!");return 0;}

It does nothing spectacular, but it is important that it uses the puts function, defined in the C standard library. We are going to overwrite it with our version of puts, which ignores its input and simply outputs a fixed string.

When this program is launched, the standard puts function is being executed.

Now let us make a simple dynamic library with the contents shown in Listing 15-8. It proxies the puts function with its alternative, which ignores its argument and always outputs a fixed string.

Listing 15-8. prelib.c

#include <stdio.h>int puts( const char* str ) {return printf("We took control over your C library! \n");}

We compile it using the following commands:

> gcc -o preload_launcher preload_launcher.c> gcc -c -fPIC prelib.c> gcc -o prelib.so -shared prelib.o

Note that the executable was not linked against the dynamic library. Listing 15-9 shows the effect of setting the LD_PRELOAD variable.

Listing 15-9. ld_preload_effect

> export LD_PRELOAD=> ./a.outHello, world!> export LD_PRELOAD=$PWD/prelib.so> ./a.outWe took control over your C library!

As we see, if the LD_PRELOAD contains a path to a shared object that defines some functions, they will override other functions that are present in the process address space.

Question 294

Refer to the assignment. Use this technique to test your malloc implementation against some standard utilities from coreutils.

Question 295

Read about dlopen, dlsym, dlclose functions.

15.6 Symbol Addressing Summary

Before we start with assembly and C examples, let us summarize the possible cases considering symbol addressing. The main executable file is usually not relocatable or position independent and loaded by a fixed absolute address, say, 0x40000.4 The dynamic library is nowadays built using position-independent code and thus its .text can be placed anywhere; in other sections the relocations might be needed.

The symbol can be:

Defined in executable and used locally there.

This is trivial, because the symbols will be bound to absolute addresses. The data addressing will be absolute, the code jumps and calls will usually be generated with offsets relative to rip.

Defined in dynamic library and used only there locally (unavailable to external objects).

In the presence of PIC, it is done by using rip-relative addressing (for data) or relative offsets (for function calls). The more general case will be discussed later in section 15.10.

NASM uses the rel keyword to achieve rip-relative addressing. This does not involve GOT or PLT.

Defined in executable and used globally.

This requires the GOT usage (and also PLT for functions) if the user is external. For internal usage the rules are the same: we do not need GOT or PLT for addressing inside the same object file.

Defined in dynamic library and used globally.

Should be a part of linked list item rather than a paragraph on its own.

15.7 Examples

It is very possible to write a dynamic library in assembly language, which will be position independent and will use GOT and PLT tables.

Linking with gcc

The recommended way of linking libraries is by using GCC. However, for this chapter we will sometimes use more primitive ld to show what is really done in greater detail. When the C runtime is involved, never use ld.

We will also limit ourselves with Intel 64 as always. The PIC code was a bit harder to write before rip-relative addressing was introduced.

15.7.1 Calling a Function

In the first example, the following features will be shown:

Addressing dynamic library data inside the same library.

Calling a function of dynamic library from the main executable file.

This example consists of main.asm (Listing 15-10) and lib.asm (Listing 15-11). The Makefile is provided in Listing 15-12 to show the building process. Notice that providing the dynamic linker explicitly is mandatory unless you are using the GCC to link files (which will take care of the appropriate dynamic linker path). See section 15.7.2 for more explanations.

Listing 15-10. ex1-main.asm

extern _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_global _startextern sofunsection .text_start:call sofun wrt ..plt; `exit` system callmov rdi, 0mov rax, 60syscall

The first thing that we notice is that extern _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ is usually imported in every file that is dynamically linked.5

The main file imports the symbol called sofun. Then, the call contains not only the function name but also the wrt ..plt qualifier.

Referring to a symbol using wrt ..plt forces the linker to create a PLT entry. The corresponding expression will be evaluated to an offset to PLT entry relative to the current position in code. Before static linkage, this offset is unknown, but it will be filled by the static linker. The type of this kind of relocation should be a rip-relative relocation (like the one used in call or jmp-like instructions). ELF structure does not provide means to address the PLT entries by their absolute addresses.

Listing 15-11. ex1-lib.asm

extern _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_global sofun:functionsection .rodatamsg: db "SO function called", 10.end:section .textsofun:mov rax, 1mov rdi, 1lea rsi, [rel msg]mov rdx, msg.end - msgsyscallret

Notice that the global symbol sofun is marked as :func (there should be no space before the colon). It is very important to mark exported functions like this in case they should be accessed by other objects dynamically.

The .end label allows us to calculate the string length statically to feed it to the write system call. The important change is the rel keyword usage.

The code is position independent, so the absolute address of msg can be arbitrary. Its offset relative to this point in code (lea rsi, [rel msg] instruction) is fixed. So, we can use lea to calculate its address as an offset from rip. This line will be compiled to lea rsi, [rip + offset], where offset is a constant that will be filled in by the static linker.

The latter form ([rip + offset]) is syntactically incorrect in NASM.

Listing 15-12 shows the Makefile used to build this example. Before launching, make sure that the environment variable LD_LIBRARY_PATH includes the current directory, otherwise you can simply type

export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=.for test purposes and then launch the executable.

Listing 15-12. ex1-makefile

main: main.o lib.sold --dynamic-linker=/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 main.o lib.so -o mainlib.so: lib.old -shared lib.o -o lib.solib.o:nasm -felf64 lib.asm -o lib.omain.o: main.asmnasm -felf64 main.asm -o main.o

Question 296

Perform an experiment. Omit the wrt ..plt construction for the call and recompile everything. Then use objdump -D -Mintel-mnemonic on the resulting main executable to check whether the PLT is still in the game or not. Try to launch it.

15.7.2 On Various Dynamic Linkers

The dynamic linker is not set in stone. It is encoded as part of metadata in the ELF file and can be viewed by means of ldd.

During linkage, you can control, which dynamic linker will be chosen, for example,

ld --dynamic-linker=/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2If you do not specify it, ld will choose the default path, which might lead to a nonexistent file in your case.

If the dynamic linker does not exist, the attempt to load the library will result in a cryptic message which does not make any sense. Suppose that you have built an executable main and it uses a library so_lib, and the LD_LIBRARY_PATH is set correctly.

./mainbash: no such file or directory: ./main> ldd ./mainlinux-vdso.so.1 => (0x00007ffcf7f9f000)so_lib.so => ./so_lib.so (0x00007f0e1cc0a000)

The problem is that the linkage was done without an appropriate dynamic linker provided and the ELF metadata does not hold a correct path to it. Relinking the object files with an appropriate dynamic linker path should solve this problem. For example, in the Debian Linux distribution installed on the virtual machine, shipped with this book, the dynamic linker is /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2.

15.7.3 Accessing an External Variable

For the next example, we will make the message string reside in the main executable file; except for that, the code will stay the same. It will allow us to show how to access the external variable.

The main file is shown in Listing 15-13, while the library source is shown in Listing 15-14.

Listing 15-13. ex2-main.asm

extern _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_global _startextern sofunglobal msg:data (msg.end - msg)section .rodatamsg: db "SO function called -- message is stored in 'main'", 10.end:section .text_start:call sofun wrt ..pltmov rdi, 0mov rax, 60syscall

Listing 15-14. ex2-lib.asm

extern _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_global sofun:funcextern msgsection .textsofun:mov rax, 1mov rdi, 1mov rsi, [rel msg wrt ..got]mov rdx, 50syscallret

It is very important to mark the dynamically shared data declaration with its size. The size is given as an expression, which may include labels and operations on them, such as subtraction. Without the size, the symbol will be treated as global by the static linker (visible to other modules during static linking phase) but will not be exported by the dynamic library.

When the variable is declared as global with its size and type (:data), it will live in the .data section of the executable file rather than the library! Because of this, you will always have to access it through GOT, even in the same file.

The GOT, as we know, stores the addresses of the variables global to the process. So, if we want to know the address of msg, we have to read an entry from GOT. However, as the dynamic library is position independent, we have to address its GOT relatively to rip as well. If we want to read its value, we need an additional memory read after fetching its address from GOT.

If the variable is declared in the dynamic library and accessed in the main executable file, it should be done with exactly the same construction: its address can be read from [rel varname wrt ..got]. If you need to store an address of the GOT variable, use the following qualifier:

othervar: dq global_var wrt ..symFor additional information, refer to section 7.9.3 of [27].

15.7.4 Complete Assembly Example

Listing 15-15 and Listing 15-16 show a complete example with all common features needed from dynamic library .

Listing 15-15. ex3-main.asm

extern _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_extern fun1global commonmsg:data commonmsg.end - commonmsgglobal mainfun:functionglobal _startsection .rodatacommonmsg: db "fun2", 10, 0.end:mainfunmsg: db "mainfun", 10, 0section .text_start:call fun1 wrt ..pltmov rax, 60mov rdi, 0syscallmainfun:mov rax, 1mov rdi, 1mov rsi, mainfunmsgmov rdx, 8syscallret

Listing 15-16. ex3-lib. asm

extern _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_extern commonmsgextern mainfunglobal fun1:functionsection .rodatamsg: db "fun1", 10section .textfun1:mov rax, 1mov rdi, 1lea rsi, [rel msg]mov rdx, 6syscallcall fun2call mainfun wrt ..pltretfun2:mov rax, 1mov rdi, 1mov rsi, [rel commonmsg wrt ..got]mov rdx, 5syscallret

15.7.5 Mixing C and Assembly

Disclaimer: we are going to provide an example which is compiler and architecture specific, so in your case the process may vary. However, the core ideas will stay more or less the same.

What can complicate mixing C and assembly code is that you have to take into account the C standard library and link everything correctly.

The easiest way is to build the object files separately with GCC and NASM , respectively, and then link them using GCC as well. Other than that, there is not much to fear. Listing 15-17 and Listing 15-8 show an example of calling the assembly library from C.

Listing 15-17. ex4-main.c

#include <stdio.h>extern int sofun( void );extern const char sostr[];int main( void ) {printf( "%d\n", sofun() );puts( sostr );return 0;}

In the main file, an external function sofun is called from the dynamic library. Its result is printed to stdout by printf. Then the string, taken from the dynamic library, is output by puts. Note that the global string is the global character buffer, not a pointer!

Listing 15-18. ex4-lib.asm

extern _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_extern putsglobal sostr:data (sostr.end - sostr)global sofun:functionsection .rodatasostr: db "sostring", 10, 0.end:localstr: db "localstr", 10, 0section .textsofun:lea rdi, [rel localstr]call puts wrt ..pltmov rax, 42ret

In the library, the sofun is defined as well as the sostr global string. sofun calls puts, the standard C library function with the localstr address as an argument. As the library is written in a position-independent way, the address should be calculated as an offset from rip; hence the lea command is used. This function always returns 42.

Listing 15-19 shows the relevant Makefile.

Listing 15-19. ex4-Makefile

all: mainmain: main.o lib.sogcc -o main main.o lib.solib.so: lib.ogcc -shared lib.o -o lib.solib.o: lib.asmnasm -felf64 lib.asm -o lib.omain.o: main.asmgcc -ansi -c main.c -o main.oclean:rm -rf *.o *.so main

15.8 Which Objects Are Linked?

The C standard library is usually implemented as one or many static libraries (which, for example, define _start) and a dynamic library, containing the function we are used to call. The library structure is strictly architecture dependent, but we are going to perform several experiments to investigate it.

The relevant documentation for our specific case can be found in [3].

How do we find which libraries GCC links the executable to? We can make an experiment using GCC with the –v argument.

Following is the list of the additional arguments GCC will implicitly accept during the final linkage according to the Makefile, shown in Listing 15-19:

/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/collect2-plugin/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/liblto_plugin.so-plugin-opt=/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/lto-wrapper-plugin-opt=-fresolution=/tmp/ccqEOGnU.res-plugin-opt=-pass-through=-lgcc-plugin-opt=-pass-through=-lgcc_s-plugin-opt=-pass-through=-lc-plugin-opt=-pass-through=-lgcc-plugin-opt=-pass-through=-lgcc_s--sysroot=/--build-id--eh-frame-hdr-m elf_x86_64--hash-style=gnu-dynamic-linker /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2-o main/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/../../../x86_64-linux-gnu/crt1.o/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/../../../x86_64-linux-gnu/crti.o/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/crtbegin.o-L/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9-L/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/../../../x86_64-linux-gnu-L/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/../../../../lib-L/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu-L/lib/../lib-L/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu-L/usr/lib/../lib-L/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/../../..main.olib.so-lgcc--as-needed -lgcc_s--no-as-needed -lc-lgcc--as-needed -lgcc_s--no-as-needed /usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/crtend.o/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/4.9/../../../x86_64-linux-gnu/crtn.o

The lto abbreviation corresponds to “link-time optimizations”, which is of no interest to us. The interesting part consists of additional libraries linked. These are:

crti.o

crtbegin.o

crtend.o

crtn.o

crt1.o

ELF files support multiple sections, as we know. A separate section .init is used to store code that will be executed before main, another section .fini is used to store code that is called when the program terminates. These sections’ contents are split into multiple files. crti and crto contain the prologue and epilogue of__init function (and likewise for__fini function). These two functions are called before and after the program execution, respectively. crtbegin and crtend contain other utility code included in .init and .fini sections. They are not always present. We want to repeat that their order is important. crt1.o contains the _start function.

To prove our statements, we are going to disassemble crti.o, crtn.o, and crt1.o files using good old

objdump -D -Mintel-mnemonic.Listings 15-20, 15-22, and 15-21 show the refined disassembly.

Listing 15-20. da_crti

/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/crti.o: file format elf64-x86-64Disassembly of section .init:0000000000000000 <_init>:0: sub rsp, 0x84: mov rax, QWORD PTR [rip+0x0] # b <_init+0xb>b: test rax, raxe: je 15 <_init+0x15>10: call 15 <_init+0x15>Disassembly of section .fini:0000000000000000 <_fini>:0: sub rsp, 0x8

Listing 15-21. da_crtn

/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/crtn.o: file format elf64-x86-64Disassembly of section .init:0000000000000000 <.init>:0: add rsp,0x84: retDisassembly of section .fini:0000000000000000 <.fini>:0: add rsp,0x84: ret

Listing 15-22. da_crt1

/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/crt1.o: file format elf64-x86-64Disassembly of section .text:0000000000000000 <_start>:0: xor ebp,ebp2: mov r9,rdx5: pop rsi6: mov rdx,rsp9: and rsp,0xfffffffffffffff0d: push raxe: push rspf: mov r8,0x016: mov rcx,0x01d: mov rdi,0x024: call 29 <_start+0x29>29: hlt

As we see, these form functions end up in the executable. To see the complete linked and relocated code, we are going to take a part of objdump -D -Mintel-mnemonic output for the resulting file, as shown in Listing 15-23.

Listing 15-23. dasm_init_fini

Disassembly of section .init:00000000004005d8 <_init>:4005d8: sub rsp,0x84005dc: mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a15] # 600ff8 <_DYNAMIC+0x1e0>4005e3: test rax,rax4005e6: je 4005ed <_init+0x15>4005e8: call 400650 <__libc_start_main@plt+0x10>4005ed: add rsp,0x84005f1: retDisassembly of section .text:0000000000400660 <_start>:400660: xor ebp,ebp400662: mov r9,rdx400665: pop rsi400666: mov rdx,rsp400669: and rsp,0xfffffffffffffff040066d: push rax40066e: push rsp40066f: mov r8,0x400800400676: mov rcx,0x40079040067d: mov rdi,0x400756400684: call 400640 <__libc_start_main@plt>400689: hltDisassembly of section .fini:0000000000400804 <_fini>:400804: sub rsp,0x8400808: add rsp,0x840080c: ret

15.9 Optimizations

What impacts the performance when working with a dynamic library?

First of all, never forget the -fPIC compiler option.6 Without it, even the .text section will be relocated, making dynamic libraries way less attractive to use. It is also crucial to disable some optimizations that might prevent dynamic libraries from working correctly.

As we have seen, when the function is declared static in the dynamic library and thus is not exported, it can be called directly without the PLT overhead. Always use static to limit visibility to a single file.

It is also possible to control visibility of the symbols in a compiler-dependent way. For example, GCC recognizes four types of visibility (default, hidden, internal, protected), of which only the first two are of interest to us. The visibility of all symbols altogether can be controlled using the -fvisibility compiler switch, as follows:

> gcc -fvisibility=hidden ... # will hide all symbols from shared objectThe “default” visibility level implies that all non-static symbols are visible from outside the shared object. By using __attribute__ directive, we can finely control visibility on a per-symbol basis. Listing 15-24 shows an example.

Listing 15-24. visibility_symbol.c

int__attribute__ (( visibility( "default" ) ))func(int x) { return 42; }

The good thing that you can do is to hide all symbols of the shared object and explicitly mark the symbols with default visibility. This way you will fully describe the interface. It is especially good because no other symbols will be exposed and you will be free to change the library internals without breaking binary compatibility of any kind.

The data relocations can slow things down a bit. Every time a variable in .data is storing an address of another variable, it should be initialized by dynamic linker once the absolute address of the latter becomes known. Avoid such situations when possible.

Since the access to local symbols bypasses PLT, you might want to reference only “hidden” functions inside your code and make publicly available wrappers for the functions you want to export. Only the calls to the wrappers will use PLT. Listing 15-25 shows an example.

Listing 15-25. so_adapter.c

static int _function( int x ) { return x + 1; }void otherfunction( ) {printf(" %d \n", _function( 41 ) );}int function( int x ) { return _function( x ); }

To eliminate possible overhead of the wrapper functions, a technique exists of writing symbol aliases (which is also compiler specific). GCC handles it by using alias attribute. Listing 15-26 shows an example.

Listing 15-26. gcc_alias.c

#include <stdio.h>int global = 42;extern int global_alias__attribute__ ((alias ("global"), visibility ("hidden" ) ));void fun( void ) {puts("1337\n");}extern void fun_alias( void )__attribute__ ((alias ("fun"), visibility ("hidden" ) ));int tester(void) {printf( "%d\n", global );printf( "%d\n", global_alias );fun();fun_alias();return 0;}

When we compile it using gcc - shared -O3 -fPIC and disassemble it, we see the code shown in Listing 15-27 (disassembly for tester function).

Listing 15-27. gcc_aliased_gain.asm

; global -> rsi787: mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x20084a] # 200fd8 <_DYNAMIC+0x1c8>78e: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rax]790: mov esi,eax792: lea rdi,[rip+0x46] # 7df <_fini+0xf>799: mov eax,0x079e: call 650 <printf@plt>; global_alias -> rsi7a3: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rip+0x20088f] # 201038 <global>7a9: mov esi,eax7ab: lea rdi,[rip+0x2d] # 7df <_fini+0xf>7b2: mov eax,0x07b7: call 650 <printf@plt>; calling global `fun`7bc: call 640 <fun@plt>; calling aliased `fun` directly7c1: call 770 <fun>

The global and global_aliased are handled differently; the latter requires one less memory read. The function call of fun is also handled more efficiently, bypassing PLT and thus sparing an extra jump.

Finally, remember, that the zero-initialized globals are always faster to initialize. However, we strongly advocate against global variables usage.

More information about shared object optimizations can be found in [13].

Note

The common way of linking against libraries is by using -l key, for example, gcc -lhello. The only two differences with specifying the full file path are

-lhello will search for a library named libhello.a (so, prefixed with lib and with an extension .a).

The library is searched in the standard list of directories. It is also searched in custom directories , which can be supplied using -L option. For example, to include the directory /usr/libcustom and the current directory, you can type

> gcc -lhello -L. -L/usr/libcustom main.c

Remember, the order in which you supply libraries matters.

15.10 Code Models

The code models are a rarely discussed topic. [24] can be viewed as a reference for this matter, and we are going to discuss code models in this section.

The starting point for the discussion is the fact, that rip-relative addressing is limited. [15] elaborates that the offset should be an immediate value of 32 bits maximum. This leaves us with ± 2 GB offsets. Making it possible to use 64-bit offsets directly is wasteful since most code would never use the extra bits; however, such offsets are directly encoded into the instructions themselves, making the code take up more space, which is not good for instruction cache. The address space size is far greater than 32 bits, so what do we do when 32 bits are not enough?

A code model is a convention to which the programmer and the compiler both adhere; it describes the constraints on the program that will use the object file that is currently being compiled. The code generation depends on it. In short, when the program is relatively small, there is no harm in using 32-bit offsets. However, when it can be large enough, the slower 64-bit offsets, which are handled by multiple instructions, should be used.

The 32-bit offsets correspond to the small code model; the 64-bit offsets correspond to the large code model. There is also a sort of compromise called the medium code model. All these models are treated differently in context of position-dependent and position-independent code, so we are going to review all six possible combinations.

There can be other code models, such as the kernel code model, but we will leave them out of this volume. If you make your own operating system you can invent one for your own pleasure.

The relevant GCC option is -mcmodel, for example, -mcmodel=large. The default model is the small model.7

The GCC manual says the following about the -mcmodel option8:

-mcmodel=smallGenerate code for the small code model: the program and its symbols must be linked in the lower 2 GB of the address space. Pointers are 64 bits. Programs can be statically or dynamically linked. This is the default code model.-mcmodel=kernelGenerate code for the kernel code model . The kernel runs in the negative 2 GB of the address space. This model has to be used for Linux kernel code.-mcmodel=mediumGenerate code for the medium model: the program is linked in the lower 2 GB of the address space. Small symbols are also placed there. Symbols with sizes larger than -mlarge-data-threshold are put into large data or BSS sections and can be located above 2GB. Programs can be statically or dynamically linked.-mcmodel=largeGenerate code for the large model. This model makes no assumptions about addresses and sizes of sections.

To illustrate the differences in compiled code when using different code models, we are going to use a simple example shown in Listing 15-28.

Listing 15-28. cm-example.c

char glob_small[100] = {1};char glob_big[10000000] = {1};static char loc_small[100] = {1};static char loc_big[10000000] = {1};int global_f(void) { return 42; }static int local_f(void) { return 42; }int main(void) {glob_small[0] = 42;glob_big[0] = 42;loc_small[0] = 42;loc_big[0] = 42;global_f();local_f();return 0;}

We will use the following line to compile it:

gcc -O0 -g cm-example.cThe -g flag adds debug information such as .line section, which describes the correspondence between assembly instructions and the source code lines.

In this example, there are bigger and smaller arrays. It matters only for medium code model, hence we will omit the big array accesses from other disassembly listings.

15.10.1 Small Code Model (No PIC)

In the small code model the program is limited in size. All objects should be within 4GB of each other to be linked. The linking can be done either statically or dynamically. As this is the default code model, we are not going to see anything interesting here.

By feeding the -S key to objdump we will intersperse the assembly code with the source C lines (if the corresponding file was compiled with -g flag). The full command sequence will look as follows:

gcc -O0 -g cm-example.c -o exampleobjdump -D -Mintel-mnemonic -S example

Listing 15-29 shows the compiled assembly.

Listing 15-29. mc-small

; glob_small[0] = 42;4004f0: c6 05 49 0b 20 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rip+0x200b49],0x2a; loc_small[0] = 42;4004fe: c6 05 3b a2 b8 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rip+0xb8a23b],0x2a; global_f();40050c: e8 c5 ff ff ff call 4004d6 <global_f>; local_f();400511: e8 cb ff ff ff call 4004e1 <local_f>

The second column shows us the hex codes of the bytes that correspond to each instruction. The array accesses are performed explicitly relative to rip, and the calls accept the offsets (which are also implicitly relative to rip). We can see that the size of data accessing instructions is 7 bytes of which 1 byte is the value (0x2a) and 4 bytes encode the offset relative to rip. It illustrates the core idea of the small code model: rip-relative addressing.

15.10.2 Large Code Model (No PIC)

Now let us compile the same code using the large code model (-mcmodel=large).

; glob_small[0] = 42;4004f0: 48 b8 40 10 60 00 00 mov rax,0x6010404004f7: 00 00 004004fa: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2a; loc_small[0] = 42;40050a: 48 b8 40 a7 f8 00 00 mov rax,0xf8a740400511: 00 00 00400514: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2a; global_f();400524: 48 b8 d6 04 40 00 00 mov rax,0x4004d640052b: 00 00 0040052e: ff d0 call rax; local_f();400530: 48 b8 e1 04 40 00 00 mov rax,0x4004e1400537: 00 00 0040053a: ff d0 call rax

Both data accesses and calls are performed uniformly. We always start by moving an immediate value into one of the general purpose registers and then reference memory using the address stored in this register.9

For a cost of a more spacious assembly code (and probably a bit slower one) we take the safest road possible allowing to reference anything in any part of the 64-bit virtual address space.

15.10.3 Medium Code Model (No PIC)

In the medium code model, the arrays of size greater than specified by the -mlarge-data-threshold compiler parameter are placed into a special .ldata and .lbss section. These sections can be placed above the 2GB mark. Basically, it is a small code model except for big chunks of data, which are placed separately. Performance-wise it is better than accessing everything via 64-bit pointers, because of locality.

The disassembly for the sources compiled with -mcmodel=medium is as follows:.

glob_small[0] = 42;400530: c6 05 09 0b 20 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rip+0x200b09],0x2aglob_big[0] = 42;400537: 48 b8 40 11 a0 00 00 movabs rax,0xa0114040053e: 00 00 00400541: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2aloc_small[0] = 42;400544: c6 05 75 0b 20 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rip+0x200b75],0x2aloc_big[0] = 42;40054b: 48 b8 c0 a7 38 01 00 movabs rax,0x138a7c0400552: 00 00 00400555: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2aglobal_f();400558: e8 b9 ff ff ff call 400516 <global_f>local_f();40055d: e8 bf ff ff ff call 400521 <local_f>

As we see, the generated code is using the large model to access big arrays and the small one for the rest of accesses. It is quite clever and might save you if you only need to work with a big chunk of statically allocated data.

15.10.4 Small PIC Code Model

Now we are going to investigate the position-independent counterparts of these three code models. As before, the small model will not surprise us, because up to now we have only worked with a small code model. For convenience, we provide the example code compiled with gcc -g -O0 -mcmodel=small -fpic.

glob_small[0] = 42;4004f0: 48 8d 05 49 0b 20 00 lea rax,[rip+0x200b49]# 601040 <glob_small>4004f7: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2aglob_big[0] = 42;4004fa: 48 8d 05 bf 0b 20 00 lea rax,[rip+0x200bbf]# 6010c0 <glob_big>400501: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2aloc_small[0] = 42;400504: c6 05 35 a2 b8 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rip+0xb8a235],0x2a# f8a740 <loc_small>loc_big[0] = 42;40050b: c6 05 ae a2 b8 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rip+0xb8a2ae],0x2a# f8a7c0 <loc_big>global_f();400512: e8 bf ff ff ff call 4004d6 <global_f>local_f();400517: e8 c5 ff ff ff call 4004e1 <local_f>

The static arrays are accessed easily relative to rip as expected. The globally visible arrays are accessed through GOT, which implies an additional read from the table itself to get its address.

15.10.5 Large PIC Code Model

Interesting things start to emerge when using a large code model with position-independent code. Now we cannot use rip-relative addressing to get to the GOT, because it can be further than 2GB in address space! Because of this, we need to allocate a register to store its address (rbx in our case).

# Standard prologue400594: 55 push rbp400595: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp# What is that?400598: 41 57 push r1540059a: 53 push rbx40059b: 48 8d 1d f9 ff ff ff lea rbx,[rip+0xfffffffffffffff9]# 40059b <main+0x7>4005a2: 49 bb 65 0a 20 00 00 movabs r11,0x200a654005a9: 00 00 004005ac: 4c 01 db add rbx,r11# Accessing global symbolsglob_small[0] = 42;4005af: 48 b8 e8 ff ff ff ff movabs rax,0xffffffffffffffe84005b6: ff ff ff4005b9: 48 8b 04 03 mov rax,QWORD PTR [rbx+rax*1]4005bd: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2a# Accessing local symbolsloc_small[0] = 42;4005d1: 48 b8 40 97 98 00 00 movabs rax,0x9897404005d8: 00 00 004005db: c6 04 03 2a mov BYTE PTR [rbx+rax*1],0x2a# Calling global functionglobal_f();4005ed: 49 89 df mov r15,rbx4005f0: 48 b8 56 f5 df ff ff movabs rax,0xffffffffffdff5564005f7: ff ff ff4005fa: 48 01 d8 add rax,rbx4005fd: ff d0 call rax# Calling local functionlocal_f();4005ff: 48 b8 75 f5 df ff ff movabs rax,0xffffffffffdff575400606: ff ff ff400609: 48 8d 04 03 lea rax,[rbx+rax*1]40060d: ff d0 call raxreturn 0;40060f: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x0}400614: 5b pop rbx400615: 41 5f pop r15400617: 5d pop rbp400618: c3 ret

This example needs to be studied carefully. First we want to break down the unusual code in the function prologue .

400598: 41 57 push r1540059a: 53 push rbx40059b: 48 8d 1d f9 ff ff ff lea rbx,[rip+0xfffffffffffffff9]# 40059b <main+0x7>4005a2: 49 bb 65 0a 20 00 00 movabs r11,0x200a654005a9: 00 00 004005ac: 4c 01 db add rbx,r11

We use rbx and r15 because they are callee-saved . They are used here to build up the GOT address out of the following two components:

The address of the current instruction, calculated in lea rbx,[rip+0xfffffffffffffff9]. The operand is equal to -6, while the instruction itself is 6 bytes long. When it is being executed, the rip value points to the next address after the instruction.

Then the number 0x200a65 is being added to rbx. It is done through another register, because adding an immediate operand of 64 bits wide is not supported by the add instruction (check the instruction description in [15]!).

This number is a displacement of GOT relative to the address of lea rbx,[rip+0xfffffffffffffff9], which, as we know, is always known at link time in position-independent code.10

The ABI considers that r15 should hold GOT address at all times. rbx is also used by GCC for its convenience.

The GOT absolute address is unknown at link time since the code is written to be position independent.

Now to the data accesses: the global symbol is accessed through GOT the same way as in non-PIC code; however, as the GOT address is stored in rbx, we have to compute the entry address using more instructions.

# Accessing global symbolsglob_small[0] = 42;4005af: 48 b8 e8 ff ff ff ff movabs rax,0xffffffffffffffe84005b6: ff ff ff4005b9: 48 8b 04 03 mov rax,QWORD PTR [rbx+rax*1]4005bd: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2a

The entry is located with a negative offset of -24 relatively to the rbx (r15) value. This displacement can be of arbitrary length, so we need to store it in a register to consider cases where it cannot be contained in 32 bits. Then we load the GOT entry to rax and use this address for our purposes (in this case we store a value in the array start).

The variables not visible as other objects are accessed using GOT as well. However, we are not reading their addresses from GOT. Rather than that, we use the rbx value as the base (as it points somewhere in the data segment). Every global variable has a fixed offset from this base, so we can just pick this offset and use the base indexed addressing mode.

# Accessing local symbolsloc_small[0] = 42;4005d1: 48 b8 40 97 98 00 00 movabs rax,0x9897404005d8: 00 00 004005db: c6 04 03 2a mov BYTE PTR [rbx+rax*1],0x2a

This is obviously faster, so whenever you can, you should prefer limiting symbol visibility as explained in section 15.9

The local functions are called in the same manner. Their address is calculated relative to GOT and stored in a register. We cannot simply use the call command, because its immediate operand is limited to 32 bits (in its description given in [15], there are only operand types rel16 and rel32, but no rel64).

# Calling local functionlocal_f();4005ff: 48 b8 75 f5 df ff ff movabs rax,0xffffffffffdff575400606: ff ff ff400609: 48 8d 04 03 lea rax,[rbx+rax*1]40060d: ff d0 call rax

Calling global functions is done in a more traditional way. Its PLT entry is used, whose address is also calculated as a fixed offset to a known GOT position.

# Calling global functionglobal_f();4005ed: 49 89 df mov r15,rbx4005f0: 48 b8 56 f5 df ff ff movabs rax,0xffffffffffdff5564005f7: ff ff ff4005fa: 48 01 d8 add rax,rbx4005fd: ff d0 call rax

15.10.6 Medium PIC Code Model

The medium code model , as in non-PIC code, is a mixture of large and small code models.

We can think of it as a small PIC code model with an addition of big arrays, residing separately.

int main(void) {40057a: 55 push rbp40057b: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp# Different from small model: we save GOT address locally.40057e: 48 8d 15 7b 0a 20 00 lea rdx,[rip+0x200a7b]glob_small[0] = 42;400585: 48 8d 05 b4 0a 20 00 lea rax,[rip+0x200ab4]40058c: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2aglob_big[0] = 42;40058f: 48 8b 05 62 0a 20 00 mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a62]400596: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2aloc_small[0] = 42;400599: c6 05 20 0b 20 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rip+0x200b20],0x2aloc_big[0] = 42;4005a0: 48 b8 c0 97 d8 00 00 movabs rax,0xd897c04005a7: 00 00 004005aa: c6 04 02 2a mov BYTE PTR [rdx+rax*1],0x2aglobal_f();4005ae: e8 a3 ff ff ff call 400556 <global_f>local_f();4005b3: e8 b0 ff ff ff call 400568 <local_f>return 0;4005b8: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x0}4005bd: 5d pop rbp4005be: c3 ret

The GOT address is also in reach of rip-relative addressing, so its address is loaded with one instruction.

40057e: 48 8d 15 7b 0a 20 00 lea rdx,[rip+0x200a7b]It is thus not always needed to dedicate a register for it, since this address will not be used everywhere.

The code references are considered to be in reach of 32-bit rip-relative offsets. So, calling any functions is trivial.

global_f();4005ae: e8 a3 ff ff ff call 400556 <global_f>local_f();4005b3: e8 b0 ff ff ff call 400568 <local_f>

As for the data accesses, the accesses to global variables are performed uniformly no matter the size. The GOT is involved in any case, and it contains 64-bit global variables addresses, so we have the possibility of addressing anything for free.

glob_small[0] = 42;400585: 48 8d 05 b4 0a 20 00 lea rax,[rip+0x200ab4]40058c: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2aglob_big[0] = 42;40058f: 48 8b 05 62 0a 20 00 mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a62]400596: c6 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rax],0x2a

The local variables, however, differ. Small arrays can be accessed relative to rip.

loc_small[0] = 42;400599: c6 05 20 0b 20 00 2a mov BYTE PTR [rip+0x200b20],0x2a

Local big arrays are found relative to GOT starting addresses, as in the large model.

loc_big[0] = 42;4005a0: 48 b8 c0 97 d8 00 00 movabs rax,0xd897c04005a7: 00 00 004005aa: c6 04 02 2a mov BYTE PTR [rdx+rax*1],0x2a

15.11 Summary

In this chapter we have received the knowledge we need to understand the machinery behind dynamic library loading and usage. We have written a library in assembly language and in C and successfully linked it to an executable.

For further reading we address you above all to a classic article [13] and to the ABI description [24].

In the next chapter we are going to speak about compiler optimizations and their effects on performance as well as about specialized instruction set extensions (SSE/AVX), aimed to speed up certain types of computations.

Question 297

What is the difference between static and dynamic linkage?

Question 298

What does the dynamic linker do?

Question 299

Can we resolve all dependencies at the link time? What kind of system should we be working with in order for this to be possible?

Question 300

Should we always relocate the .data section?

Question 301

Should we always relocate the .text section?

Question 302

What is PIC?

Question 303

Can we share a .text section between processes when it is being relocated?

Question 304

Can we share a .data section between processes when it is being relocated?

Question 305

Can we share a .data section when it is being relocated?

Question 306

Why are we compiling dynamic libraries with an -fPIC flag?

Question 307

Write a simple dynamic library in C from scratch and demonstrate the calling function from it.

Question 308

What is ldd used for?

Question 309

Where are the libraries searched?

Question 310

What is the environment variable LD_LIBRARY_PATH for?

Question 311

What is GOT? Why is it needed?

Question 312

What makes GOT usage effective?

Question 313

How come that position-independent code can address GOT directly but cannot address global variables directly?

Question 314

Is GOT unique for each process?

Question 315

What is PLT?

Question 316

Why don’t we use GOT to call functions from different objects (or do we)?

Question 317

What does the initial GOT entry for a function point at?

Question 318

How do we preload a library and what can it be used for?

Question 319

In assembly, how is the symbol addressed if it is defined in the executable and accessed from there?

Question 320

In assembly, how is the symbol addressed if it is defined in the library and accessed from there?

Question 321

In assembly, how is the symbol addressed if it is defined in the executable and accessed from everywhere?

Question 322

In assembly, how is the symbol addressed if it is defined in the library and accessed from everywhere?

Question 323

How do we control the visibility of a symbol in a dynamic library? How do we make it private for the library but accessible from anywhere in it?

Question 324

Why do people sometimes write wrapper functions for those used in library?

Question 325

How do we link against a library that is stored in libdir?

Question 326

What is a code model and why do we care about code models?

Question 327

What limitations impose the small code model?

Question 328

Which overhead does the large code model carry?

Question 329

What is the compromise between large and small code models?

Question 330

When is the medium model most useful?

Question 331

How do large code models differ for PIC and non-PIC code?

Question 332

How do medium code models differ for PIC and non-PIC code?

Footnotes

1 We will not provide the details on what the hash tables are or how are they implemented, but if you do not know about them, we highly advise you to read about them! This is an absolutely classic data structure used everywhere. A good explanation can be found in [10]

2 Do not confuse with -O flag for the compiler!

3 A probabilistic data structure that is widely used. It allows us to quickly check whether an element is contained in a certain set, but the answer “yes” is subject to an additional check, while “no” is always certain.

4 This is not always the case, for example, OS X recommends that all executables are made position independent.

6 The -fpic option implies a limit on GOT size for some architectures, which is often faster.

7 Not all compilers and GCC versions support the large model.

8 Note that there are different descriptions for different architectures.

9 If you encounter the movabs instruction, consider it equivalent to the mov instruction.

10 Obviously, here r15 and rbx hold not the beginning of GOT but its end, but it does not matter.