This chapter covers virtual memory as implemented in Intel 64. We are going to start by motivating an abstraction over physical memory and then getting a general understanding of how it looks like from a programmer’s perspective. Finally, we will dive into implementation details to achieve a more complete understanding.

4.1 Caching

Let’s start with a truly omnipresent concept called caching .

The Internet is a big data storage. You can access any part of it, but the delay after you made a query can be significant. To smoothen your browsing experience, web browser caches web pages and their elements (images, style sheets, etc.). This way it does not have to download the same data over and over again. In other words, the browser saves the data on the hard drive or in RAM (random access memory) to give much faster access to a local copy. However, downloading the whole Internet is not an option, because the storage on your computer is very limited.

A hard drive is much bigger than RAM but also a great deal slower. This is why all work with data is done after preloading it in RAM. Thus main memory is being used as a cache for data from external storage.

Anyway, a hard drive also has a cache on its own...

On CPU crystal there are several levels of data caches (usually three: L1, L2, L3). Their size is much smaller than the size of main memory, but they are much faster too (the closest level to the CPU is almost as close as registers). Additionally, CPUs possess at least an instruction cache (queue storing instructions) and a Translation Lookaside Buffer to improve virtual memory performance.

Registers are even faster than caches (and smaller) so they are a cache on their own.

Why is this situation so pervasive? In information system, which does not need to give strict guarantees about its performance levels, introducing caches often decreases the average access time (the time between a request and a response). To make it work we need our old friend locality: in each moment of time we only have a small working set of data.

The virtual memory mechanism allows us, among other things, to use physical memory as a cache for chunks of program code and data.

4.2 Motivation

Naturally, given a single task system where there is only one program running at any moment of time, it is wise just to put it directly into physical memory starting at some fixed address. Other components (device drivers, libraries) can also be placed into memory in some fixed order.

In a multitasking-friendly system, however, we prefer a framework supporting a parallel (or pseudo parallel) execution of multiple programs. In this case an operating system needs some kind of memory management to deal with these challenges:

Executing programs of arbitrary size (maybe even greater than physical memory size). It demands an ability to load only those parts of program we need in the near future.

Having several programs in memory at the same time.

Programs can interact with external devices, whose response time is usually slow. During a request to a slow piece of hardware that may last thousands of cycles, we want to lend precious CPUs to other programs. Fast switching between programs is only possible if they are already in memory; otherwise we have to spend much time retrieving them from external storage.

Storing programs in any place of physical memory.

If we achieve that, we can load pieces of programs in any free part of the memory, even if they are using absolute addressing.

In case of absolute addressing, like mov rax, [0x1010ffba], all addresses including starting address become fixed: all exact address values are written into machine code.

Freeing programmers from memory management tasks as much as possible.

While programming, we do not want to think about how different memory chips on our target architectures can function, what is the amount of physical memory available, etc. Programmers should pay closer attention to program logic instead.

Effective usage of shared data and code.

Whenever several programs want to access the same data or code (libraries) files, it is a waste to duplicate them in memory for each additional user.

Virtual memory usage addresses these challenges.

4.3 Address Spaces

Address space is a range of addresses. We see two types of address spaces:

Physical address, which is used to access the bytes on the real hardware. Naturally, there is a certain memory capacity a processor cannot exceed. It is based on addressing capabilities. For example, a 32-bit system cannot address more than 4GB of memory per process, because 232 different addresses roughly correspond to 4GB of addressed memory. However, we could put less memory inside the machine capable of addressing 4GB, like, 1GB or 2GB. In this case some addresses of the physical address space will become forbidden, because there are no real memory cells behind them.

Logical address is the address as an application sees it.

In instruction mov rax, [0x10bfd] there is a logical address: 0x10bfd.

A programmer has an illusion that he is the sole memory user. Whatever memory cell he addresses, he never sees data or instructions of other programs, which are running with his own in parallel. Physical memory holds several programs at time, however.

In our circumstances virtual address is synonymous to logical address.

Translation between these two address types is performed by a hardware entity called Memory Management Unit (MMU) with help of multiple translation tables, residing in memory.

4.4 Features

Virtual memory is an abstraction over physical memory. Without it we would work directly with physical memory addresses.

In the presence of virtual memory we can pretend that every program is the only memory consumer, because it is isolated from others in its own address space.

The address space of a single process is split into pages of equal length (usually 4KB). These pages are then dynamically managed. Some of them can be backed up to external storage (in a swap file), and brought back in case of a need.

Virtual memory offers some useful features , by assigning an unusual meaning to memory operations (read, write) on certain memory pages.

We can communicate with external devices by means of Memory Mapped Input/Output (e.g., by writing to the addresses, assigned to some device, and reading from them).

Some pages can correspond to files, taken from external storage with the help of the operating system and file system.

Some pages can be shared among several processes.

Most addresses are forbidden—their value is not defined, and an attempt to access them results in an error.1 This situation usually results in abnormal termination of program.

Linux and other Unix-based systems use a signal mechanism to notify applications of exceptional situations. It is possible to assign a handler to almost all types of signals.

Accessing a forbidden address will be intercepted by the operating system, which will throw a SIGSEGV signal at the application. It is quite common to see an error message, Segmentation fault, in this situation.

Some pages correspond to files, taken from storage (executable file itself, libraries, etc.), but some do not. These anonymous pages correspond to memory regions of stack and heap —dynamically allocated memory. They are called so because there are no names in file system to which they correspond. To the contrary, an image of the running executable data files and devices (which are abstracted as files too) all have names in the file system.

A continuous area of memory is called a region if:

It starts at an address, which is multiple of a page size (e.g., 4KB).

All its pages have the same permissions.

If the free physical memory is over, some pages can be swapped to external storage and stored in a swap file, or just discarded (in case they correspond to some files in file system and were not changed, for example). In Windows, the file is called PageFile.sys, in *nix systems a dedicated partition is usually allocated on disk. The choice of pages to be swapped is described by one of the replacement strategies, such as:

Least recently used.

Last recently used.

Random (just pick a random page).

Any kind of a system with caching has a replacement strategy.

Question 47

Read about different replacement strategies. What other strategies exist?

Each process has a working set of pages. It consists of his exclusive pages present in physical memory.

Allocation

What happens when a process needs more memory? It cannot get more pages on its own, so it asks the operating system for more pages. The system provides it with additional addresses.

Dynamic memory allocation in higher-level languages (C++, Java, C#, etc.) eventually ends up querying pages from the operating system, using the allocated pages until the process runs out of memory and then querying more pages.

4.5 Example: Accessing Forbidden Address

Now we are going to see a memory map of a single process with our own eyes. It shows which pages are available and what they correspond to. We will observe different kinds of memory regions:

Corresponding to executable file, loaded into memory, itself.

Corresponding to code libraries.

Corresponding to stack and heap ( anonymous pages ).

Just empty regions of forbidden addresses.

Linux offers us an easy-to-use mechanism to explore various useful information about processes, called procfs. It implements a special purpose file system, where by navigating directories and viewing files, one can get access to any process’s memory, environment variables, etc. This file system is mounted in the /proc directory.

Most notably, the file /proc/PID/maps shows a memory map of process with identifier PID.2

Let’s write a simple program , which enters a loop (and thus does not terminate) (Listing 4-1). It will allow us to see its memory layout while it is running.

Listing 4-1. mappings_loop.asm

section .datacorrect: dq -1section .textglobal _start_start:jmp _start

Now we have to launch a file /proc/?/maps, where ? is the process ID. See the complete terminal contents in Listing 4-2.

Listing 4-2. mappings_loop

> nasm -felf64 -o main.o mappings_loop.asm> ld -o main main.o> ./main &[1] 2186> cat /proc/2186/maps00400000-00401000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 144225 /home/stud/main00600000-00601000 rwxp 00000000 08:01 144225 /home/stud/main7fff11ac0000-7fff11ae1000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0 [stack]7fff11bfc000-7fff11bfe000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso]7fff11bfe000-7fff11c00000 r--p 00000000 00:00 0 [vvar]ffffffffff600000-ffffffffff601000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vsyscall]

Left column defines the memory region range. As you may notice, all regions are contained between addresses ending with three hexadecimal zeros. The reason is that they are composed of pages whose size is 4KB each (= 0x1000 bytes).

We observe that different sections defined in the assembly file were loaded as different regions. The first region corresponds to the code section and holds encoded instructions; the second corresponds to data.

As you see, the address space is huge and spans from 0-th to 264 −1-th byte. However, only a few addresses are allocated; the rest are being forbidden.

The second column shows read, write, and execution permissions on pages. It also indicates whether the page is shared among several processes or it is private to this specific process.

Question 48

Read about meaning of the fourth (08:01) and fifth (144225) column in man procfs.

So far we did nothing wrong. Now let’s try to write into a forbidden location.

Listing 4-3. Producing segfault: segfault_badaddr.asm

section .datacorrect: dq -1section .textglobal _start_start:mov rax, [0x400000-1]; exitmov rax, 60xor rdi, rdisyscall

We are accessing memory at address 0x3fffff, which is one byte before the code segment start. This address is forbidden and hence the writing attempt results in a segmentation fault, as the message suggests.

> ./main Segmentation fault4.6 Efficiency

Loading a missing page into physical memory from a swap file is a very costly operation, involving a huge amount of work from operating system. How come this mechanism turned out not only to be effective memory-wise but also to perform adequately? The key success factors are:

Thanks to locality, the need to load additional pages occurs rarely. In the worst case we have indeed very slow access; however, such cases are extremely rare. Average access time stays low.

In other words, we rarely try to access a page which is not loaded in physical memory.

It is clear that efficiency could not be achieved without the help of special hardware. Without a cache of translated page addresses TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer) we would have to use a translation mechanism all the time. TLB stores the starting physical addresses for some pages we will likely to work with. If we translate a virtual address inside one of these pages, the page start will be immediately fetched from TLB.

In other words, we rarely try to translate an address from a page, that we did not recently locate in physical memory.

Remember that a program that uses less memory can be faster because it produces fewer page faults.

Question 49

What is an associative cache? Why is TLB one?

4.7 Implementation

Now we are going to dive into details and see how exactly the translation happens.

Note

For now we are only talking about a dominant case of 4KB pages. Page size can be tuned and other parameters will change accordingly; refer to section 4.7.3 and [15] for additional details.

4.7.1 Virtual Address Structure

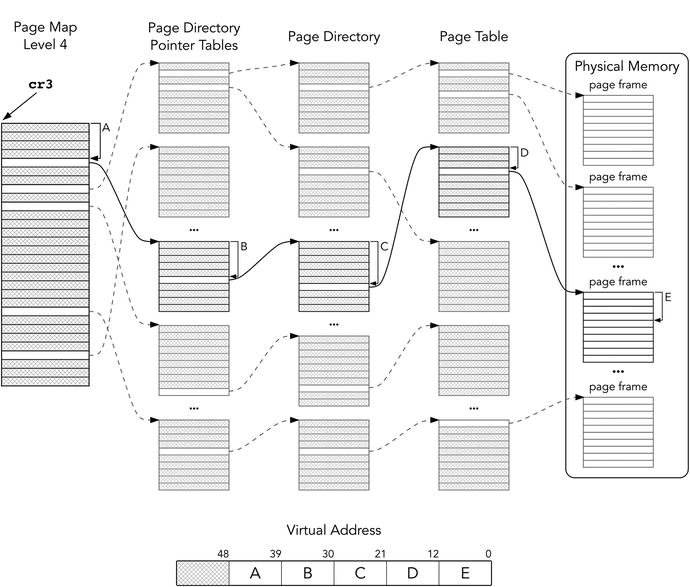

Each virtual 64-bit address (e.g., ones we are using in our programs) consists of several fields, as shown in Figure 4-1.

Figure 4-1. Structure of virtual address

The address itself is in fact only 48 bits wide; it is sign-extended to a 64-bit canonical address. Its characteristic is that its 17 left bits are equal. If the condition is not satisfied, the address gets rejected immediately when used.

Then 48 bits of virtual address are transformed into 52 bits of physical address with the help of special tables.3

Bus Error

When occasionally using a non-canonical address you will see another error message: Bus error.

Physical address space is divided into slots to be filled with virtual pages. These slots are called page frames . There are no gaps between them, so they always start from an address ending with 12 zero bits.

The least significant 12 bits of virtual address and of physical page correspond to the address offset inside page, so they are equal.

The other four parts of virtual address represent indexes in translation tables. Each table occupies exactly 4KB to fill an entire memory page. Each record is 64 bits wide; it stores a part of the next table’s starting address as well as some service flags.

4.7.2 Address Translation in Depth

Figure 4-2 reflects the address translation process .

Figure 4-2. Virtual address translation schematic

First, we take the first table starting address from cr3. The table is called Page Map Level 4 (PML4). Fetching elements from PML4 is performed as follows:

Bits 51:12 are provided by cr3.

Bits 11:3 are bits 47:39 of the virtual address.

The last three bits are zeroes.

The entries of PML4 are referred as PML4E. The next step of fetching an entry from the Page Directory Pointer table mimics the previous one:

Bits 51:12 are provided by selected PML4E.

Bits 11:3 are bits 38:30 of the virtual address.

The last three bits are zeroes.

The process iterates through two more tables until at last we fetch the page frame address (to be precise, its 51:12 bits). The physical address will use them and 12 bits will be taken directly from the virtual address.

Are we going to perform so many memory reads instead of one now? Yes, it does look bulky. However, thanks to the page address cache, TLB , we usually access memory on already translated and memorized pages. We should only add the correct offset inside page, which is blazingly fast.

As TLB is an associative cache; it is quickly providing us with translated page addresses given a starting virtual address of the page.

Note that translation pages can be cached for a faster access. Figure 4-3 specifies the Page Table Entry format.

Figure 4-3. Page table entry

P Present (in physical memory)

W Writable (writing is allowed)

U User (can be accessed from ring3)

A Accessed

D Dirty (page was modified after being loaded—e.g., from disk)

EXB Execution-Disabled Bit (forbids executing instructions on this page)

AVL Available (for operating system developers)

PCD Page Cache Disable

PWT Page Write-Through (bypass cache when writing to page)

If P is not set, an attempt to access the page results in an interrupt with code #PF (Page fault). The operating system can handle it and load the respective page. It can also be used to implement lazy file memory mapping. The file parts will be loaded in memory as needed.

The operating system uses W bit to protect the page from being modified. It is needed when we want to share code or data between processes, avoiding unnecessary doubling. Shared pages marked with W can be used for data exchange between processes.

Operating system pages have U bit cleared. If we try to access them from ring3, an interrupt will occur.

In absence of segment protection the virtual memory is the ultimate memory guarding mechanism.

On segmentation faults

In general, segmentation faults occurs when there is an attempt to access memory with insufficient permissions (e.g., writing into read-only memory). In case of forbidden addresses we can consider them to have no valid permissions, so accessing them is just a particular case of memory access with insufficient permissions.

EXB (also called NX) bit forbids code execution . The DEP (Data Execution Prevention) technology is based on it. When a program is being executed, parts of its input can be stored in a stack or its data section. A malicious user can exploit its vulnerabilities to mix encoded instructions into the input and then execute them. However, if data and stack section pages are marked with EXB, no instructions can be executed from them. The .text section, however, will remain executable, but it is usually protected from any modifications by W bit anyway.

4.7.3 Page Sizes

The structure of tables of a different hierarchy level is very much alike. The page size may be tuned to be 4KB, 2MB, or 1GB. Depending on the structure, this hierarchy can shrink to a minimum of two levels. In this case PDP will function as a page table and will store part of a 1GB frame. See Figure 4-4 to see how the entry format changes depending on page size.

Figure 4-4. Page Directory Pointer table and Page Directory table entry format

This is controlled by the 7-th bit in the respective PDP or PD entry. If it is set, the respective table maps pages; otherwise, it stores addresses of the next level tables.

4.8 Memory Mapping

Mapping means “projection,” making correspondence between entities (files, devices, physical memory), and virtual memory regions. When the loader fills the process’s address space, when a process requests pages from the operating system, when the operating system projects files from a disk into processes’ address spaces—these are examples of memory mapping.

A system call mmap is used for all types of memory mapping. To perform it we follow the same simple steps described in Chapter 2. Table 4-1 shows its arguments.

Table 4-1. mmap System Call

REGISTER | VALUE | MEANING |

|---|---|---|

rax | 9 | System call identifier |

rdi | addr | An operating system attempts to map into pages starting from this specific address. This address should correspond to a page start. A zero address indicates that the operating system is free to choose any start. |

rsi | len | Region size |

rdx | prot | Protection flags (read, write, execute…) |

r10 | flags | Utility flags (shared or private, anonymous pages, etc.) |

r8 | fd | Optional descriptor of a mapped file. The file should therefore be opened. |

r9 | offset | Offset in file. |

After a call to mmap, rax will hold a pointer to the newly allocated pages.

4.9 Example: Mapping File into Memory

We need another system call, namely, open. It is used to open a file by name and to acquire its descriptor . See Table 4-2 for details.

Table 4-2. open System Call

REGISTER | VALUE | MEANING |

|---|---|---|

rax | 2 | System call identifier |

rdi | file name | Pointer to a null-terminated string, name.holding file |

rsi | flags | A combination of permission flags (read only, write only, or both). |

rdx | mode | If sys open is called to create a file, it will hold its file system permissions. |

Mapping file in memory is done in three simple steps :

Open file using open system call. rax will hold file descriptor.

Call mmap with relevant arguments. One of them will be the file descriptor, acquired at step 1.

Use print_string routine we have created in Chapter 2. For the sake of brevity we omit file closing and error checks.

4.9.1 Mnemonic Names for Constants

Linux was written in C, so to ease interaction with it some useful constants are predefined in a C way. The line

#define NAME 42defines a substitution performed in compile time. Whenever a programmer writes NAME, the compiler substitutes it with 42. This is useful to create mnemonic names for various constants. NASM provides similar functionality using

%define directive%define NAME 42

See section 5.1 “Preprocessor” for more details on how such substitutions are made.

Let’s take a look at a man page for mmap system call, describing its third argument prot.

The prot argument describes the desired memory protection of the mapping (and must not conflict with the open mode of the file). It is either PROT_NONE or the bitwise OR of one or more of the following flags:PROT_EXEC Pages may be executed.PROT_READ Pages may be read.PROT_WRITE Pages may be written.PROT_NONE Pages may not be accessed.

PROT_NONE and its friends are examples of such mnemonic names for integers used to control mmap behavior. Remember that both C and NASM allow you to perform compile-time computations on constant values, including bitwise AND and OR operations. Following is an example of such computation:

%define PROT_EXEC 0x4%define PROT_READ 0x1mov rdx, PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC

Unless you are writing in C or C++, you will have to check these predefined values somewhere and copy them to your program.

Following is how to know the specific values of these constants for Linux:

Search them in header files of the Linux API in /usr/include.

Use one of the Linux Cross Reference (lxr) online, like: http://lxr.free-electrons.com .

We do recommend the second way for now, as we do not know C yet. You may even use a search engine like Google and type lxr PROT_READ as a search query to get relevant results immediately after following the first link.

For example, here is what LXR shows when being queried PROT_READ:

PROT_READDefined as a preprocessor macro in:arch/mips/include/uapi/asm/mman.h, line 18arch/xtensa/include/uapi/asm/mman.h, line 25arch/alpha/include/uapi/asm/mman.h, line 4arch/parisc/include/uapi/asm/mman.h, line 4include/uapi/asm-generic/mman-common.h, line 9

By following one of these links you will see

18 #define PROT_READ 0x01 /* page can be read */So, we can type %define PROT_READ 0x01 in the beginning of the assembly file to use this constant without memorizing its value.

4.9.2 Complete Example

Create a file test.txt with any contents and then compile and launch the file listed in Listing 4-4 in the same directory. You will see file contents written to stdout.

Listing 4-4. mmap.asm

; These macrodefinitions are copied from linux sources; Linux is written in C, so the definitions looked a bit; different there.; We could have just looked up their values and use; them directly in right places; However it would have made the code much less legible%define O_RDONLY 0%define PROT_READ 0x1%define MAP_PRIVATE 0x2section .data; This is the file name. You are free to change it.fname: db 'test.txt', 0section .textglobal _start; These functions are used to print a null terminated stringprint_string:push rdicall string_lengthpop rsimov rdx, raxmov rax, 1mov rdi, 1syscallretstring_length:xor rax, rax.loop:cmp byte [rdi+rax], 0je .endinc raxjmp .loop.end:ret_start:; call openmov rax, 2mov rdi, fnamemov rsi, O_RDONLY ; Open file read onlymov rdx, 0 ; We are not creating a file; so this argument has no meaningsyscall; mmapmov r8, rax ; rax holds opened file descriptor; it is the fourth argument of mmapmov rax, 9 ; mmap numbermov rdi, 0 ; operating system will choose mapping destinationmov rsi, 4096 ; page sizemov rdx, PROT_READ ; new memory region will be marked read onlymov r10, MAP_PRIVATE ; pages will not be sharedmov r9, 0 ; offset inside test.txtsyscall ; now rax will point to mapped locationmov rdi, raxcall print_stringmov rax, 60 ; use exit system call to shut down correctlyxor rdi, rdisyscall

4.10 Summary

In this chapter we have studied the concept and the implementation of virtual memory. We have elaborated it as a particular case of caching. Then we have reviewed the different types of address spaces (physical, virtual) and the connection between them through a set of translation tables. Then we dived into the virtual memory implementation details.

Finally, we have provided a minimal working example of the memory the mapping using Linux system calls. We will use it again in the assignment for Chapter 13, where we will base our dynamic memory allocator on it. In the next chapter we are going to study the process of translation and linkage to see how an operating system uses the virtual memory mechanism to load and execute programs.

Question 50

What is virtual memory region?

Question 51

What will happen if you try to modify the program execution code during its execution?

Question 52

What are forbidden addresses?

Question 53

What is a canonical address?

Question 54

What are the translation tables?

Question 55

What is a page frame?

Question 56

What is a memory region?

Question 57

What is the virtual address space? How is it different from the physical one?

Question 58

What is a Translation Lookaside Buffer?

Question 59

What makes the virtual memory mechanism performant?

Question 60

How is the address space switched?

Question 61

Which protection mechanisms does the virtual memory incorporate?

Question 62

What is the purpose of EXB bit?

Question 63

What is the structure of the virtual address?

Question 64

Does a virtual and a physical address have anything in common?

Question 65

Can we write a string in .text section? What happens if we read it? And if we overwrite it?

Question 66

Write a program that will call stat, open, and mmap system calls (check the system calls table in Appendix C). It should output the file length and its contents.

Question 67

Write the following programs, which all map a text file input.txt containing an integer x in memory using a mmap system call, and output the following:

x! (factorial, x! = 1 · 2 · · · · · (x − 1) · x). It is guaranteed that x ≥ 0.

0 if the input number is prime, 1 otherwise.

Sum of all number’s digits.

x-th Fibonacci number.

Checks if x is a Fibonacci number.