In this chapter we will explore the multithreading capabilities provided by the C language. Multithreading is a topic for a book on its own, so we will concentrate on the language features and relevant properties of the abstract machine rather than good practices and program architecture-related topics.

Until C11, the support of the multithreading was external to the language itself, via libraries and nonstandard tricks. A part of it (atomics) is now implemented in many compilers and provides a standard-compliant way of writing multithreaded applications. Unfortunately, to this day, the support of threading itself is not implemented in most toolchains, so we are going to use the library pthreads to write down code examples. We will still use the standard-compliant atomics.

This chapter is by no means an exhaustive guide to multithreaded programming, which is a beast worth writing a dedicated book about, but it will introduce the most important concepts and relevant language features. If you want to become proficient in it, we recommend lots of practice, specialized articles, books such as [34], and code reviews from your more experienced colleagues.

17.1 Processes and Threads

It is important to understand the difference between two key concepts involved in most talks about multithreading: threads and processes.

A

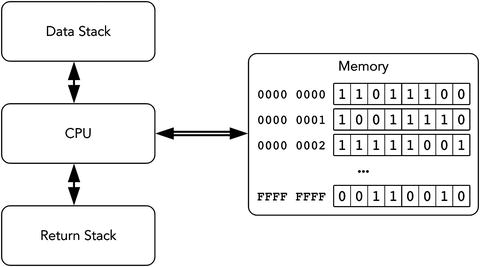

process is a resource container that collects all kinds of runtime information and resources a program needs to be executed. A process contains the following:

An address space, partially filled with executable code, data, shared libraries, other mapped files, etc. Parts of it can be shared with other processes.

All other kinds of associated state such as open file descriptors, registers, etc.

Information such as process ID, process group ID, user ID, group ID . . .

Other resources used for interprocess communication: pipes, semaphores, message queues . . .

thread is a stream of instructions that can be scheduled for execution by the operating system.

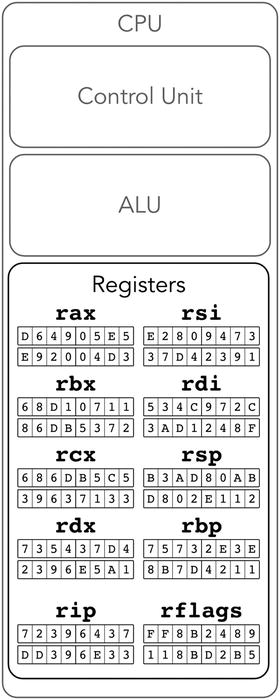

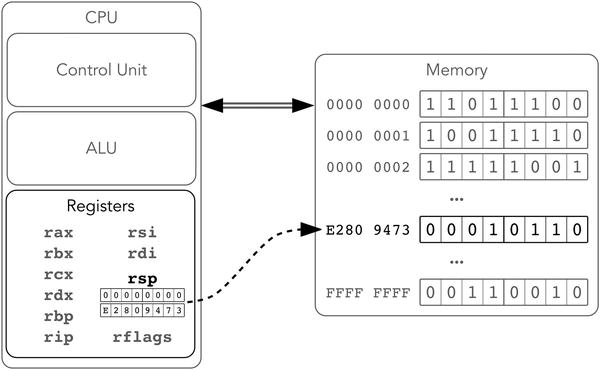

The operating system does not schedule processes but threads. Each thread lives as a part of a process and has a piece of process state, which is its own.

Registers.

Stack (technically, it is defined by the stack pointer register; however, as all processor’s threads share the same address space, one of them can access the stacks of other threads, although this is rarely a good idea).

Properties of importance to the scheduler such as priority.

Pending and blocked signals.

Signal mask.

When the process is closed, all associated resources are freed, including all its threads, open file descriptors, etc.

17.2 What Makes Multithreading Hard?

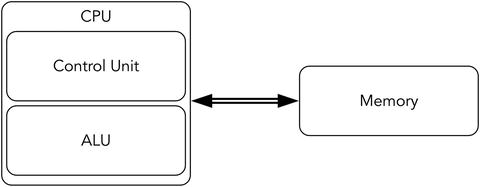

Multithreading allows you to make use of several processor cores (or several processors) to execute threads at the same time. For example, if one thread is reading file from a disk (which is a very slow operation), the other might use the pause to perform CPU-heavy computations, distributing CPU (central processing unit) load more uniformly in time. So, it can be faster, if your program can benefit from it.

Threads should often work on the same data. As long as the data is not modified by any of them, there are no problems working with it, because reading data has zero effect on other threads execution. However, if the shared data is being modified by one (or multiple) threads, we face several problems, such as the following:

When does thread A see the changes performed by B?

In which order do threads change the data? (As we have seen in the Chapter 16, the instructions can be reordered for optimization purposes.)

How can we perform operations on the complex pieces of data without other threads interfering?

When these problems are not addressed properly, a very problematic sort of bug appears, which is hard to catch (because it only appears casually, when the instruction of the different threads are executed in a specific, unlucky order). We will try to establish an understanding and study these problems and how they can be solved.

17.3 Execution Order

When we started to study the C abstract machine

, we got used to thinking that the sequence of C statements corresponds to the actions performed by the compiled machine instructions—naturally, in the same order. Now it is time to dive into the more pragmatic details of why it is not really the case.

We tend to describe algorithms in a way that is easier to understand, and this is almost always a good thing. However, the order given by the programmer is not always optimal performance-wise.

For example, the compiler might want to improve locality without changing the code semantics. Listing 17-1 shows an example.

Listing 17-1.

ex_locality_src.c

char x[1000000], y[1000000];

...

x[4] = y[4];

x[10004] = y[10004];

x[5] = y[5];

x[10005] = y[10005];

Listing 17-2 shows a possible translation result.

Listing 17-2.

ex_locality_asm1.asm

mov al,[rsi + 4]

mov [rdi+4],al

mov al,[rsi + 10004]

mov [rdi+10004],al

mov al,[rsi + 5]

mov [rdi+5],al

mov al,[rsi + 10005]

mov [rdi+10005],al

However, it is evident, that this code could

be rewritten to ensure better locality; that is, first assign x[4] and x[5], then assign x[10004] and x[10005], as shown in Listing 17-3.

Listing 17-3.

ex_locality_asm2.asm

mov al,[rsi + 4]

mov [rdi+4],al

mov al,[rsi + 5]

mov [rdi+5],al

mov al,[rsi + 10004]

mov [rdi+10004],al

mov al,[rsi + 10005]

mov [rdi+10005],al

The effects of these two instruction sequences are similar if the abstract machine only considers one CPU: given any initial machine state, the resulting state after their executions will be the same. The second translation result often performs faster, so the compiler might prefer it. This is the simple case of memory reordering, a situation in which the memory accesses are reordered comparing to the source code.

For single thread applications, which are executed “really sequentially,” we can often expect the order of operations to be irrelevant as long as the observable behavior will be unchanged. This freedom ends as soon as we start communicating between threads.

Most inexperienced programmers do not think

much about it because they limit themselves with single-threaded programming. In these days, we can no longer afford not to think about parallelism because of how pervasive it is and how it is often the only thing that can really boost the program performance. So, in this chapter, we are going to talk about memory reorderings and how to set them up correctly.

17.4 Strong and Weak Memory Models

Memory reorderings

can be performed by the compiler (as shown above), or by the processor itself, in the microcode. Usually, both of them are being performed and we will be interested in both of them. A uniform classification can be created for them all.

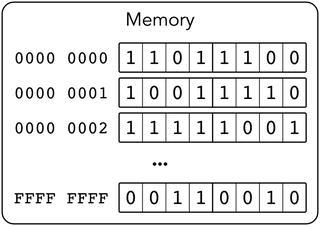

A memory model tells us which kinds of reorderings of load and store instructions can be expected. We are not interested in the exact instructions used to access memory most of the time (mov, movq, etc.), only the fact of reading or writing to memory is of importance to us.

There are two extreme poles: weak and strong memory models. Just like with the strong and weak typing, most existing conventions fall somewhere between, closer to one or another. We have found a classification made by Jeff Preshing [31] to be useful and will stick to it in this book.

According to it, the memory

models can be divided into four categories, enumerated from the more relaxed ones to the stronger ones.

Really weak.

In these models, any kind of memory reordering can happen (as long as the observable behavior of a single-threaded program is unchanged, of course).

Weak with data dependency ordering (such as hardware memory model of ARM v7).

Here we speak about one particular kind of data dependency: the one between loads. It occurs when we need to fetch an address from memory and then use it to perform another fetch, for example,

Mov rdx, [rbx]

mov rax, [rdx]

In C this is the situation when we use the ➤ operator to get to a field of a certain structure through the pointer to that structure.

Really weak memory models do not guarantee data dependency ordering.

Usually strong (such as hardware memory model of Intel 64).

It means that there is a guarantee that all stores are performed in the same order as provided. Some loads, however, can be moved around.

Intel 64 is usually falling into this category.

Sequentially consistent.

This can be described as what you see when you debug a non-optimized program step by step on a single processor core. No memory reordering ever happens.

17.5 Reordering Example

Listing 17-4 shows an exemplary situation when memory reordering can give us a bad day. Here two threads are executing the statements contained

in functions thread1 and thread2, respectively.

Listing 17-4.

mem_reorder_sample.c

int x = 0;

int y = 0;

void thread1(void) {

x = 1;

print(y);

}

void thread2(void) {

y = 1;

print(x);

}

Both threads share variables x and y. One of them performs a store into x and then loads the value of y, while the other one does the same, but with y and x instead.

We are interested in two types of memory accesses: load and store. In our examples, we will often omit all other actions for simplicity.

As these instructions are completely independent (they operate on different data), they can be reordered inside each thread without changing observable behavior, giving us four options: store + load or load + store for each of two threads. This is what a compiler can do for its own reasons. For each option six possible execution orders exist. They depict how both threads advance in time relative to one another.

We show them as sequences of 1 and 2; if the first thread made a step, we write 1; otherwise the second one made a step.

1-1-2-2

1-2-1-2

2-1-1-2

2-1-2-1

2-2-1-1

1-2-2-1

For example, 1-1-2-2 means that the first process has executed two steps, and then the second process did the same. Each sequence corresponds to four different scenarios. For example

, the sequence 1-2-1-2 encodes one of the traces, shown in Table 17-1:

Table 17-1. Possible Instruction Execution Sequences If Processes Take Turns as 1-2-1-2

1 | store x | store x | load y | load y |

2 | store y | load x | store y | load x |

1 | load y | load y | store x | store x |

2 | load x | store y | load x | store y |

If we observe these possible traces for each execution order, we will come up with 24 scenarios (some of which will be equivalent). As you see, even for the small examples these numbers can be large enough.

We do not need all these possible traces anyway; we are interested in the position of load relatively to store for each variable. Even in Table 17-1 many possible combinations are present: both x and y can be stored, then loaded, or loaded, then stored. Obviously, the result of load is dependent on whether there was a store before.

Were reorderings not in the game, we would be limited: any of the two specified loads should have been preceded by a store because so it is in the source code; scheduling instructions in a different manner cannot change that. However, as the reorderings are present, we can sometimes achieve an interesting outcome: if both of these threads have their instructions reordered, we come to a situation shown in Listing 17-5.

Listing 17-5.

mem_reorder_sample_happened.c

int x = 0;

int y = 0;

void thread1(void) {

print(y);

x = 1;

}

void thread2(void) {

print(x);

y = 1;

}

If the strategy 1-2-*-* (where * denotes any of the threads) is chosen, we execute load x and load y first, which will make them appear to equal to 0 for everyone who uses these loads’ results

It is indeed possible in case compiler reordered these operations. But even if they are controlled well or disabled, the memory reorderings, performed by CPU, still can produce such an effect.

This example demonstrates that the outcome

of such a program is highly unpredictable. Later we are going to study how to limit reorderings by the compiler and by CPU; we will also provide a code to demonstrate this reordering in the hardware.

17.6 What Is Volatile and What Is Not

The C memory model

, which we are using, is quite weak. Consider the following code:

int x,y; x = 1;

y = 2;

x = 3;

As we have already seen, the instructions can be reordered by the compiler. Even more, the compiler can deduce that the first assignment is the dead code, because it is followed in another assignment to the same variable x. As it is useless, the compiler can even remove this statement.

The volatile keyword addresses this issue. It forces the compiler to never optimize the writes and reads to the said variable and also suppresses any possible instruction reorderings. However, it only enforces these restrictions to one single variable and gives no guarantee about the order in which writes to different volatile variables are emitted. For example, in the previous code, even changing both x and y type to volatile int will impose an order on assignments of each of them but will still allow us to interleave the writes freely as follows:

volatile int x, y;

x = 1;

x = 3;

y = 2;

Or like this:

volatile int x, y;

y = 2;

x = 1;

x = 3;

Obviously, these guarantees are not sufficient for multithreaded applications. You cannot use volatile variables to organize an access to the shared data, because these accesses can be moved around freely enough.

To safely access shared data, we need two guarantees.

The read or write actually takes place. The compiler could have just cached the value in the register and never write it back to memory.

This is the guarantee volatile provides. It is enough to perform memory-mapped I/O (input/output), but not for multithreaded applications.

No memory reordering

should take place. Let us imagine we use volatile variable as a flag, which indicates that some data is ready to be read. The code prepares data and then sets the flag; however, reordering can place this assignment before the data is prepared.

Both hardware and compiler reorderings matter here. This guarantee is not provided by volatile variables.

In this chapter, we study two mechanisms that provide both of the following guarantees:

Volatile variables are used extremely rarely. They suppress optimization, which is usually not something we want to do.

17.7 Memory Barriers

Memory barrier

is a special instruction or statement that imposes constraints on how the reorderings can be done. As we have seen in the Chapter 16, compilers or hardware can use many tricks to improve performance in the average case, including reordering, deferred memory operations, speculative loads or branch prediction, caching variables in registers, etc. Controlling them is vital to ensure that certain operations are already performed, because the other thread’s logic depends on it.

In this section, we want to introduce the different kinds of memory barriers and give us a general idea about their possible implementations on Intel 64.

An example of the memory barrier preventing reorderings by compiler is the following GCC directive:

asm volatile("" ::: "memory")

The asm directive is used to include inline assembly code directly into C programs. The volatile keyword together with the "memory" clobber argument describes that this (empty) piece of inline assembly cannot be optimized away or moved around and that it performs memory reads and/or writes. Because of that, the compiler is forced to emit the code to commit all operations to memory (e.g., store the values of the local variables, cached in registers). It does not prevent the processor from performing speculative reads past this statement, so it is not a memory barrier for the processor itself.

Obviously, both compiler and CPU memory barriers are costly because they prevent optimizations. That is why we do not want to use them after each instruction.

There are several kinds of memory barriers

. We will speak about those that are defined in the Linux kernel documentation, but this classification is applicable in most situations.

Write memory barrier.

It guarantees that all store operations specified in code before the barrier will appear to happen before all store operations specified after the barrier.

GCC uses asm volatile(""::: "memory") as a general memory barrier. Intel 64 uses the instruction sfence.

Read memory barrier.

Similarly, it guarantees that all load operations specified in code before the barrier will appear to happen before all load operations specified after the barrier. It is a stronger form of data dependency barrier.

GCC uses asm volatile(""::: "memory") as a general memory barrier. Intel 64 uses the instruction lfence.

Data dependency barriers.

Data dependency barrier considers the dependent reads, described in section 17.4. It can be thus considered a weaker form of read memory barrier. No guarantees about independent loads or any kinds of stores are provided.

General memory barriers

This is the ultimate barrier, which forces every memory change specified in code before it is committed. It also prevents all following operations to be reordered in a way they appear to be executed before the barrier.

GCC uses asm volatile(""::: "memory") as a general memory barrier. Intel 64 uses the instruction mfence.

Acquire operations.

This is a class of operations, united by a property called Acquire semantics. If an operation performs reads from shared memory and is guaranteed to not be reordered with the following reads and writes in the source code, it is said to have this property.

In other words, it is similar to a general memory barrier, but the code that follows will not be reordered in a way to be executed before this barrier.

Release operations.

Release

semantics

is a property of such operations. If an operation performs writes to shared memory and is guaranteed to not be reordered with the previous reads and writes in the source code, it is said to have this property.

In other words, it is similar to a general memory barrier but still allows the more recent operations to be reordered in a position before the release operation.

Acquire and release operations, thus, are one-way barriers for reorderings in a way.

Following is an example of a single assembly command mfence, inlined by GCC:

asm ("mfence" )

By combining it with the compiler barrier, we get a line that both prevents compiler reordering and also acts as a full memory barrier.

asm volatile("mfence" ::: "memory")

Any function call whose definition is not available in the current translation unit and that is not an intrinsic (a cross-platform substitute of a specific assembly instruction) is a compiler memory barrier.

17.8 Introduction to pthreads

POSIX threads

(pthreads) is a standard describing a certain model of program execution. It provides means to execute code in parallel and to control the execution. It is implemented as a library pthreads, which we are going to use throughout this chapter.

The library contains C types, constants, and procedures (which are prefixed with pthread_). Their declarations are available in the pthread.h header. The functions provided by it fall into one of the following groups:

In this section we are going to study several examples to become familiar with pthreads.

To perform multithreaded computations you have the following two options:

Spawn multiple threads in the same process.

The threads share the same address space, so the data exchange is relatively easy and fast. When the process terminates, so do all of its threads.

Spawn multiple processes; each of them has its own default thread. These threads communicate via mechanisms provided by the operating system (such as pipes).

This is not that fast; also spawning a process is slower than spawning just a thread, because it creates more operating system structures (and a separate address space). The communication between processes often implies one or more (sometimes implicit) copy operations.

However, separating program logic into separate processes can have a positive impact on security and robustness, because each thread only sees the exposed part of the processes others than its own.

Pthreads allows you to spawn multiple threads in a single process, and that is what you usually want to do.

17.8.1 When to Use Multithreading

Sometimes multithreading

is convenient for the program logic. For example, you usually should not accept a network packet and draw the graphical interface in the same thread. The graphical interface should react to user actions (clicks on the buttons) and be redrawn constantly (e.g., when the corresponding window gets covered by another window and then uncovered). The network action, however, will block the working thread until it is done. It is thus convenient to split these actions into different threads to perform them seemingly simultaneously.

Multithreading can naturally improve performance, but not in all cases. There are CPU bound tasks and IO bound tasks.

CPU bound code can be sped up if given more CPU time. It spends most of the CPU time doing computations, not reading data from disk or communicating with devices.

IO bound code cannot be sped

up with more CPU time because it is slowed by its excessive usage of memory or external devices.

Using multithreading to speed CPU bound programs might be beneficial. A common pattern is to use a queue with the requests that are dispatched to the worker threads from a thread pool–a set of created threads that are either working or waiting for work but are not re-created each time there is a need of them. Refer to Chapter 7 of [23] for more details.

As for how many threads we need, there is no universal recipe. Creating threads, switching between them, and scheduling them produces an overhead. It might make the whole program slower if there is not much work for threads to do. In computation-heavy tasks some people advise to spawn n − 1 threads, where n is the total number of processor cores. In tasks that are sequential by their own nature (where every step depends directly on the previous one) spawning multiple threads will not help. What we do recommend is to always experiment with the number of threads under different workloads to find out which number suits the most for the given task.

17.8.2 Creating Threads

Creating threads

is easy. Listing 17-6 shows an example.

Listing 17-6.

pthread_create_mwe.c

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

void* threadimpl( void* arg ) {

for(int i = 0; i < 10; i++ ) {

puts( arg );

sleep(1);

}

return NULL;

}

int main( void ) { pthread_t t1, t2;

pthread_create( &t1, NULL, threadimpl, "fizz" );

pthread_create( &t2, NULL, threadimpl, "buzzzz" );

pthread_exit( NULL );

puts("bye");

return 0;

}

Note that the code that uses pthread library must be compiled with -pthread flag, for example,

> gcc -O3 -pthread main.c

That specifying -lpthread will not give us an esteemed result. Linking with the sole libpthread.a is not enough: there are several preprocessor options that are enabled by -pthread (e.g., _REENTRANT). So, whenever the -pthread option is available,1 use it.

Initially, there is only one thread

which starts executing the main function. A pthread_t type stores all information about some other thread, so that we can control it using this instance as a handle. Then, the threads are initialized with pthread_create function with the following signature:

int pthread_create(

pthread_t *thread,

const pthread_attr_t *attr,

void *(*start_routine) (void *),

void *arg);

The first argument is a pointer to the pthread_t instance to be initialized. The second one is a collection of attributes, which we will touch later–for now, it is safe to pass NULL instead.

The thread starting function should accept a pointer and return a pointer. It accepts a void* pointer to its argument. Only one argument is allowed; however, you can easily create a structure or an array, which encapsulates multiple arguments, and pass a pointer to it. The return value of the start_routine is also a pointer and can be used to return the work result of the thread.2 The last argument is the actual pointer to the argument, which will be passed to the start_routine function.

In our example, each thread is implemented the same way: it accepts a pointer (to a string) and then repeatedly outputs it with an interval of approximately one second. The sleep function, declared in unistd.h, suspends the current thread for a given number of seconds.

After ten iterations, the thread returns. It is equivalent to calling the function pthread_exit with an argument. The return value is usually the result of the computations performed by the thread; return NULL if you do not need it. We will see later how it is possible to get this value from the parent thread.

However, the naive return from the

main function will lead to process termination. What if other threads still exist? The main thread should wait for their termination first! This is what pthread_exit does when it is called in the main thread: it waits for all other threads to terminate and then terminates the program. All the code that follows will not be executed, so you will not see the bye message in stdout.

This program will output a pair of buzz and fizz lines in random order ten times and then exit. It is impossible to predict whether the first or the second thread will be scheduled first, so each time the order can differ. Listing 17-7 shows an exemplary output.

Listing 17-7.

pthread_create_mwe_out

> ./main

fizz

buzzzz

buzzzz

fizz

fizz

buzzzz

fizz

buzzzz

fizz

buzzzz

buzzzz

fizz

buzzzz

fizz

buzzzz

fizz

buzzzz

fizz

buzzzz

fizz

As you see, the string bye is not printed, because the corresponding puts call is below the pthread_exit call.

The maximum number of threads spawned depends on implementation. In Linux, for example, you can use ulimit -a to get relevant information.

The threads can create other threads; there is no limitation on that.

It is indeed guaranteed by the

pthreads implementation that a call for pthread_create acts as a full compiler memory barrier as well as a full hardware memory barrier.

pthread_attr_init is used to initialize an instance of an opaque type pthread_attr_t (implemented as an

incomplete type

). Attributes provide additional parameters for threads such as stack size or address.

The following functions are used to set attributes

:

pthread_attr_setaffinity_np–the thread will prefer to be executed on a specific CPU core.

pthread_attr_setdetachstate–will we be able to call pthread_join on this thread, or will it be detached (as opposed to joinable). The purpose of pthread_join will be explained in the next section.

pthread_attr_setguardsize–sets up the space before the stack limit as a region of forbidden addresses of a given size to catch stack overflows.

pthread_attr_setinheritsched–are the following two parameters inherited from the parent thread (the one where the creation happened), or taken from the attributes themselves?

pthread_attr_setschedparam–right now is all about scheduling priority, but the additional parameters can be added in the future.

pthread_attr_

setschedpolicy–how will the scheduling be performed. Scheduling policies with their respective descriptions can be seen in man sched.

pthread_attr_setscope–refers to the contention scope system, which defines a set of threads against which this thread will compete for CPU (or other resources).

pthread_attr_setstackaddr–where will the stack be located?

pthread_attr_setstacksize–what will be the thread stack size?

pthread_attr_setstack–sets both stack address and stack size.

All of them have their “get” counterparts (e.g., pthread_attr_getscope).

17.8.3 Managing Threads

What we have learned is already enough to perform work in parallel. However, we have no means of synchronization yet, so once we have distributed the work for the threads, we cannot really use the computation results of one thread in other threads.

The simplest form of synchronization

is thread joining. The idea is simple: by calling thread_join on an instance of pthread_t we put the current thread into the waiting state until the other thread is terminated. Listing 17-8 shows an example.

Listing 17-8.

thread_join_mwe.c

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void* worker( void* param ) {

for( int i = 0; i < 3; i++ ) {

puts( (const char*) param );

sleep(1);

}

return (void*)"done";

}

int main( void ) {

pthread_t t;

void* result;

pthread_create( &t, NULL, worker, (void*) "I am a worker!" );

pthread_join( t, &result );

puts( (const char*) result );

return 0;

}

The thread_join accepts two arguments

: the thread itself and the address of a void* variable, which will be initialized with the thread execution result.

Thread joining acts as a full barrier because we should not place before the joining any reads or writes that are planned to happen after.

By default, the threads are created joinable, but one might create a detached thread. It might bring a certain benefit: the resources of the detached thread can be released immediately upon its termination. The joinable thread, however, will be waiting to be joined before its resources can be released. To create a detached thread

Create an attribute instance pthread_attr_t attr;

Initialize it with pthread_attr_init( &attr );

Call pthread_attr_setdetachstate( &attr, PTHREAD_CREATE_DETACHED ); and

Create the thread by using pthread_create with a &attr as the attribute argument.

The current thread can be explicitly changed from joinable to detached by calling pthread_detach(). It is impossible to do it the other way around.

17.8.4 Example: Distributed Factorization

We have picked a simple CPU

bound program of counting the factors of a number. First, we are going to solve it using the most trivial brute-force method on a single core. Listing 17-9 shows the code.

Listing 17-9.

dist_fact_sp.c

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <inttypes.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <malloc.h>

uint64_t factors( uint64_t num ) {

uint64_t result = 0;

for (uint64_t i = 1; i <= num; i++ )

if ( num % i == 0 ) result++;

return result;

}

int main( void ) {

/* volatile to prevent constant propagation */

volatile uint64_t input = 2000000000;

printf( "Factors of %"PRIu64": %"PRIu64"\n", input, factors(input) );

return 0;

}

The code is quite simple: we naively iterate over all numbers from 1 to the input and check whether they are factors or not. Note that the input value is marked volatile to prevent the whole result from being computed during the compilation. Compile the code with the following command:

> gcc -O3 -std=c99 -o fact_sp dist_fact_sp.c

We will start parallelization with a dumbed-down version of multithreaded code, which will always perform computations in two threads and will not be architecturally beautiful. Listing 17-10 shows it.

Listing 17-10.

dist_fact_mp_simple.c

#include <pthread.h>

#include <inttypes.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int input = 0;

int result1 = 0;

void* fact_worker1( void* arg ) {

result1 = 0;

for( uint64_t i = 1; i < input/2; i++ )

if ( input % i == 0 ) result1++;

return NULL;

}

int result2 = 0;

void* fact_worker2( void* arg ) {

result2 = 0;

for( uint64_t i = input/2; i <= input; i++ )

if ( input % i == 0 ) result2++;

return NULL;

}

uint64_t factors_mp( uint64_t num ) {

input = num;

pthread_t thread1, thread2;

pthread_create( &thread1, NULL, fact_worker1, NULL );

pthread_create( &thread2, NULL, fact_worker2, NULL );

pthread_join( thread1, NULL );

pthread_join( thread2, NULL );

return result1 + result2;

}

int main( void ) {

uint64_t input = 2000000000;

printf( "Factors of %"PRIu64": %"PRIu64"\n",

input, factors_mp(input ));

return 0;

}

Upon launching it produces the same result, which is a good sign.

Factors of 2000000000: 110

What is this program

doing? Well, we split the range (0, n] into two halves. Two worker threads are computing the number of factors in their respective halves. Then when both of them have been joined, we are guaranteed that they have already had performed all computations. The results just need to be summed up.

Then, in Listing 17-11 we show the multithreaded program that uses an arbitrary number of threads to compute the same result. It has a better-thought-out architecture

.

Listing 17-11.

dist_fact_mp.c

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <inttypes.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <malloc.h>

#define THREADS 4

struct fact_task {

uint64_t num;

uint64_t from, to;

uint64_t result;

};

void* fact_worker( void* arg ) {

struct fact_task* const task = arg;

task-> result = 0;

for( uint64_t i = task-> from; i < task-> to; i++ )

if ( task->num % i == 0 ) task-> result ++;

return NULL;

}

/* assuming threads_count < num */

uint64_t factors_mp( uint64_t num, size_t threads_count ) {

struct fact_task* tasks = malloc( threads_count * sizeof( *tasks ) );

pthread_t* threads = malloc( threads_count * sizeof( *threads ) );

uint64_t start = 1;

size_t step = num / threads_count;

for( size_t i = 0; i < threads_count; i++ ) {

tasks[i].num = num;

tasks[i].from = start;

tasks[i].to = start + step;

start += step;

}

tasks[threads_count-1].to = num+1;

for ( size_t i = 0; i < threads_count; i++ )

pthread_create( threads + i, NULL, fact_worker, tasks + i );

uint64_t result = 0;

for ( size_t i = 0; i < threads_count; i++ ) {

pthread_join( threads[i], NULL );

result += tasks[i].result;

}

free( tasks );

free( threads );

return result;

}

int main( void ) {

uint64_t input = 2000000000;

printf( "Factors of %"PRIu64": %"PRIu64"\n",

input, factors_mp(input, THREADS ) );

return 0;

}

Suppose we are using t threads

. To count the number of factors of n, we split the range from 1 to n on t equal parts. We compute the number of factors in each of those intervals and then sum up the results.

We create a type to hold the information about single task called struct fact_task. It includes the number itself, the range bounds to and to, and the slot for the result, which will be the number of factors of num between from and to.

All workers who calculate the number of factors are implemented alike, as a routine fact_worker, which accepts a pointer to a struct fact_task, computes the number of factors, and fills the result field.

The code performing thread launch and results collection is contained in the factors_mp function, which, for a given number of threads, is

Allocating the task descriptions and the thread instances;

Initializing the task descriptions;

Starting all threads;

Waiting for each thread to end its execution by using join and adding up its result to the common accumulator result; and

Freeing all allocated memory

.

So, we put the thread creation into a black box, which allows us to benefit from the multithreading.

This code can be compiled with the following command:

> gcc -O3 -std=c99 -pthread -o fact_mp dist_fact_mp.c

The multiple threads are decreasing the overall execution time on a multicore system for this CPU bound task.

To test the execution time, we will stick with the time utility again (a program, not a shell builtin command). To ensure, that the program is being used instead of a shell builtin, we prepend it with a backslash.

> gcc -O3 -o sp -std=c99 dist_fact_sp.c && \time ./sp

Factors of 2000000000: 110

21.78user 0.03system 0:21.83elapsed 99%CPU (0avgtext+0avgdata 524maxresident)k

0inputs+0outputs (0major+207minor)pagefaults 0swaps

> gcc -O3 -pthread -o mp -std=c99 dist_fact_mp.c && \time ./mp

Factors of 2000000000: 110

25.48user 0.01system 0:06.58elapsed 387%CPU (0avgtext+0avgdata 656maxresident)k

0inputs+0outputs (0major+250minor)pagefaults 0swaps

The multithreaded program took 6.5 seconds

to be executed, while the single-threaded version took almost 22 seconds. That is a big improvement.

In order to speak about performance we are going to introduce the notion of speedup. Speedup

is the improvement in speed of execution of a program executed on two similar architectures with different resources. By introducing more threads we make more resources available, hence the possible improvement might take place.

Obviously, for the first example we have chosen a task that is easy and more efficient to solve in parallel. The speedup will not always be that substantial, if any; however, as we see, the overall code is compact enough (could be even less would we not take extensibility into account—for example, fix a number of threads, instead of using it as a parameter).

17.8.5

Mutexes

While thread joining is an accessible technique, it does not provide means to control the thread execution “on the run.” Sometimes we want to ensure that the actions performed in one thread are not being performed before some other action in the other threads are performed. Otherwise, we will get a situation where the system is not always working in a stable manner: its output will become dependent on the actual order in which the instructions from the different threads will be executed. It occurs when working with the mutable data shared between threads. Such situations are called data races, because the threads compete for the resources, and any thread can win and get to them first.

To prevent such situations, there is a number of tools, and we will start with mutexes.

Mutex

(a shorthand for “mutual exclusion”) is an object that can be in two states: locked and unlocked. We work with them using two queries.

Lock. Changes the state from unlocked to locked. If the mutex is locked, then the attempting thread waits until the mutex is unlocked by other threads.

Unlock. If the mutex is locked, it becomes unlocked.

Mutexes are often used to provide an exclusive access to a shared resource (like a shared piece of data). The thread that wants to work with the resource locks the mutex, which is exclusively used to control an access to a resource. After the work with the resource is finished, the thread unlocks the mutex.

Mutex locking and unlocking acts as both a compiler and full hardware memory barriers, so no reads or writes can be reordered before locking or after unlocking.

Listing 17-12 shows an example program which needs a mutex.

Listing 17-12.

mutex_ex_counter_bad.c

#include <pthread.h>

#include <inttypes.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

pthread_t t1, t2;

uint64_t value = 0;

void* impl1( void* _ ) {

for (int n = 0; n < 10000000; n++) {

value += 1;

}

return NULL;

}

int main(void) {

pthread_create( &t1, NULL, impl1, NULL );

pthread_create( &t2, NULL, impl1, NULL );

pthread_join( t1, NULL );

pthread_join( t2, NULL );

printf( "%"PRIu64"\n", value );

return 0;

}

This program has two threads

, implemented by the function impl1. Both threads are constantly incrementing the shared variable value 10000000 times.

This program should be compiled with the optimizations disabled to prevent this incrementing loop from being transformed into a single value += 10000000 statement (or we can make value volatile).

gcc -O0 -pthread mutex_ex_counter_bad.c

The resulting output is, however, not 20000000, as we might have thought, and is different each time we launch the executable:

> ./a.out

11297520

> ./a.out

10649679

> ./a.out

13765500

The problem is that incrementing a variable is not an atomic operation from the C point of view. The generated assembly code conforms to this description by using multiple instructions to read a value, add one, and then put it back. It allows the scheduler to give the CPU to another thread “in the middle” of a running increment operation. The optimized code might or might not have the same behavior.

To prevent this mess we are going to use a mutex to grant a thread a privilege to be the sole one working with value. This way we enforce a correct behavior. Listing 17-13 shows the modified program.

Listing 17-13.

mutex_ex_counter_good.c

#include <pthread.h>

#include <inttypes.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

pthread_mutex_t m; //

pthread_t t1, t2;

uint64_t value = 0;

void* impl1( void* _ ) {

for (int n = 0; n < 10000000; n++) {

pthread_mutex_lock( &m );//

value += 1;

pthread_mutex_unlock( &m );//

}

return NULL;

}

int main(void) {

pthread_mutex_init( &m, NULL ); //

pthread_create( &t1, NULL, impl1, NULL );

pthread_create( &t2, NULL, impl1, NULL );

pthread_join( t1, NULL );

pthread_join( t2, NULL );

printf( "%"PRIu64"\n", value );

pthread_mutex_destroy( &m ); //

return 0;

}

Its output is consistent (although takes more time to compute):

> ./a.out

20000000

The mutex

m is associated by the programmer with a shared variable value. No modifications of value should be performed outside the code section between the m lock and unlock. If this constraint is satisfied, there is no way value can be changed by another thread once the lock is taken. The lock acts as a memory barrier as well. Because of that, value will be reread after the lock is taken and can be cached in a register safely. There is no need to make the variable value volatile, since it will only suppress optimizations and the program is correct anyway.

Before a mutex can be used, it should be initialized with pthread_mutex_init, as seen in the main function. It accepts attributes, just like the pthread_create function, which can be used to create a recursive mutex, create a deadlock detecting mutex, control the robustness (what happens if the mutex owner thread dies?), and more.

To dispose of a mutex, the call to pthread_mutex_unlock is used.

17.8.6 Deadlocks

A sole mutex

is rarely a cause of problems. However, when you lock multiple mutexes at a time, several kinds of strange situations can happen. Take a look at the example shown in Listing 17-14.

Listing 17-14.

deadlock_ex

mutex A, B;

thread1 () {

lock(A);

lock(B);

unlock(B);

unlock(A);

}

thread2() {

lock(B);

lock(A);

unlock(A);

unlock(B);

}

This pseudo code demonstrates a situation where both threads can hang forever. Imagine that the following sequence of actions happened due to unlucky scheduling:

After that, the threads will try to do the following:

Thread 1 will attempt to lock B, but B is already locked by thread 2.

Thread 2 will attempt to lock A, but A is already locked by thread 1.

Both threads will be stuck in this state forever. When threads are stuck in a locked state waiting for each other to perform unlock, the situation is called deadlock.

The cause of the deadlock is the different order in which the locks are being taken by different threads. It leads us to a simple rule that will save us most of the times when we need to lock several mutexes at a time.

17.8.7 Livelocks

Livelock is a situation

in which two threads are stuck but not in a waiting-for-mutex-unlock state. Their states are changing, but they are not really progressing. For example, pthreads does not allow you to check whether the mutex is locked or not. It would be useless to provide information about the mutex state, because once you obtain information about it, the latter can already be changed by the other thread.

if ( mutex is not locked ) {

/* We still do not know if the mutex is locked or not.

Other thread might have locked or unlocked it

several times already. */

}

However, pthread_mutex_trylock is allowed, which either locks a mutex or returns an error if it has already been locked by someone. Unlike pthread_mutex_lock, it does not block the current thread waiting for the unlock. Using pthread_mutex_trylock can lead to livelock situations. Listing 17-15 shows a simple example in pseudo code.

Listing 17-15.

livelock_ex

mutex m1, m2;

thread1() {

lock( m1 );

while ( mutex_trylock m2 indicates LOCKED ) {

unlock( m1 );

wait for some time;

lock( m1 );

}

// now we are good because both locks are taken

}

thread2() {

lock( m2 );

while ( mutex_trylock m1 indicates LOCKED ) {

unlock( m2 );

wait for some time;

lock( m2 );

}

// now we are good because both locks are taken

}

Each thread tries to defy the principle

“locks should always be performed in the same order.” Both of them want to lock two mutexes m1 and m2.

The first thread performs as follows:

This pause is meant to provide the other thread time to lock m1 and m2 and perform whatever it wants to do. However, we might be stuck in a loop when

Thread 1 locks m1, thread 2 locks m2.

Thread 1 sees that m2 is locked and unlocks m1 for a time.

Thread 2 sees that m1 is locked and unlocks m2 for a time.

Go back to step one.

This loop can take forever to complete or can produce significant delays; it is entirely up to the operating system scheduler. So, the problem with this code is that execution traces exist that will forever prevent threads from progress.

17.8.8 Condition Variables

Condition variables

are used together with mutexes. They are like wires transmitting an impulse to wake up a sleeping thread, waiting for some condition to be satisfied.

Mutexes implement synchronization by controlling thread access to a resource; condition variables, on the other hand, allow threads to synchronize based upon additional rules. For example, in case of shared data, the actual value of data might be a part of such rule.

The core of condition variables usage consists of three new entities:

The condition variable itself of type pthread_cond_t.

A function to send a wake-up signal through a condition variable pthread_cond_signal.

A function to wait until a wake-up signal comes through a condition variable pthread_cond_wait.

These two functions should only be used between a lock and unlock of the same mutex.

It is an error to call pthread_cond_signal before pthread_cond_wait, otherwise the program might be stuck.

Let us study a minimal working example shown in Listing 17-16.

Listing 17-16.

condvar_mwe.c

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <unistd.h>

pthread_cond_t condvar = PTHREAD_COND_INITIALIZER;

pthread_mutex_t m;

bool sent = false;

void* t1_impl( void* _ ) {

pthread_mutex_lock( &m );

puts( "Thread2 before wait" );

while (!sent)

pthread_cond_wait( &condvar, &m );

puts( "Thread2 after wait" );

pthread_mutex_unlock( &m );

return NULL;

}

void* t2_impl( void* _ ) {

pthread_mutex_lock( &m );

puts( "Thread1 before signal" );

sent = true;

pthread_cond_signal( &condvar );

puts( "Thread1 after signal" );

pthread_mutex_unlock( &m );

return NULL;

}

int main( void ) {

pthread_t t1, t2;

pthread_mutex_init( &m, NULL );

pthread_create( &t1, NULL, t1_impl, NULL );

sleep( 2 );

pthread_create( &t2, NULL, t2_impl, NULL );

pthread_join( t1, NULL );

pthread_join( t2, NULL );

pthread_mutex_destroy( &m );

return 0;

}

Running this code

will produce the following output:

./a.out

Thread2 before wait

Thread1 before signal

Thread1 after signal

Thread2 after wait

Initializing a condition variable can be performed either through an assignment of a special preprocessor constant PTHREAD_COND_INITIALIZER or by calling pthread_cond_init. The latter can accept a pointer to attributes of type pthread_condattr_t akin to pthread_create or pthread_mutex_init.

In this example, two threads are created: t1, performing instructions from t1_impl, and t2, performing ones from t2_impl.

The first thread locks the mutex m. It then waits for a signal that can be transmitted through the condition variable condvar. Note that pthread_cond_wait also accepts the pointer to the currently locked mutex.

Now t1 is sleeping, waiting for the signal to come. The mutex m becomes immediately unlocked! When the thread gets the signal, it will relock the mutex automatically and continue its execution from the next statement after pthread_cond_wait call.

The other thread is locking the same mutex m and issuing a signal through condvar. pthread_cond_signal sends the signal through condvar, unblocking at least one of the threads, blocked on the condition variable condvar.

The pthread_cond_

broadcast

function would unblock all threads waiting for this condition variable, making them contend for the respective mutex as if they all issued pthread_mutex_lock. It is up to the scheduler to decide in which order will they get access to the CPU.

As we see, condition variables let us block until a signal is received. An alternative would be a “busy waiting” when a variable’s value is constantly checked (which kills performance and increases unnecessary power consumption) as follows:

while (somecondition == false);

We can of course put the thread to sleep for a time, but this way we will still wake up either too rarely to react to the event in time or too often:

while (somecondition == false)

sleep(1); /* or something else that lets us sleep for less time */

Condition variables let us wait just enough time and continue the thread execution in the locked state.

An important moment should be explained. Why did we introduce a shared variable sent? Why are we using it together with the condition variable? Why are we waiting inside the while (!sent) cycle?

The most important reason is that the implementation is permitted to issue spurious wake-ups to a waiting thread. It means that the thread can wake up from waiting on a signal not only after receiving it but at any time. In this case, as the sent variable is only set before sending the signal, spurious wake-up will check its value and if it is still equal to false will issue the pthread_cond_wait again.

17.8.9 Spinlocks

A mutex

is a sure way of doing synchronization. Trying to lock a mutex which is already taken by another thread puts the current thread into a sleeping state. Putting the thread to sleep and waking it up has its costs, notably for the context switch, but if the waiting is long, these costs justify themselves. We spend a little time going to sleep and waking up, but in a prolonged sleep state the thread does not use the CPU.

What would be an alternative? The active idle, which is described by the following simple pseudo code:

while ( locked == true ) {

/* do nothing */

}

locked = true;

The variable locked is a flag showing whether some thread took the lock or not. If another thread took the lock, the current thread will constantly poll its value until it is changed back. Otherwise it proceeds to take the lock on its own. This wastes CPU time (and increases power consumption), which is bad. However, it can increase performance in case the waiting time is expected to be very short. This mechanism is called

spinlock

.

Spinlocks only make sense on multicore and multiprocessor systems. Using spinlock in a single core is useless. Imagine a thread enters the cycle inside the spinlock. It keeps waiting for other thread to change the locked value, but no other thread is executing at this very time, because there is only one core switching from thread to thread. Eventually the scheduler will put the current thread to sleep and allow other threads to perform, but it just means that we have wasted CPU cycles executing an empty loop for no reason at all! In this case, going to sleep right away is always better, and hence there is no use for a spinlock.

This scenario can of course occur on a multicore system as well, but there is also a (usually) good chance, that the other thread will unlock the spinlock before the time quantum given to the current thread expires.

Overall, using spinlocks can be beneficial or not; it depends on the system configuration, program logic, and workload. When in doubt, test and prefer using mutexes (which are often implemented by first taking a spinlock for a number of iterations and then falling into the sleep state if no unlock occurred).

Implementing a fast and correct spinlock in practice is not that trivial. There are questions to be answered, such as the following:

Do we need a memory barrier on lock and/or unlock? If so, which one? Intel 64, for example, has lfence, sfence, and mfence.

How do we ensure that the flag modification is atomic? In Intel 64, for example, an instruction xchg suffices (with lock prefix in case of multiple processors).

pthreads provide us with a carefully designed and portable mechanism of spinlocks. For more information, refer to the man pages for the following functions:

pthread_spin_lock

pthread_spin_destroy

pthread_spin_unlock

17.9 Semaphores

Semaphore

is a shared integer variable on which three actions can be performed.

Initialization with an argument N. Sets its value to N.

Wait (enter). If the value is not zero, it decrements it. Otherwise waits until someone else increments it, and then proceeds with the decrement.

Post (leave). Increments its value.

Obviously the value of this variable, not directly accessible, cannot fall below 0.

Semaphores are not part of pthreads specification; we are working with semaphores whose interface is described in the POSIX standard. However, the code that uses the semaphores should be compiled with a -pthread flag.

Most UNIX-like operating systems implement both standard pthreads features and semaphores. Using semaphores is fairly common to perform synchronization between threads.

Listing 17-17 shows an example of semaphore usage.

Listing 17-17.

semaphore_mwe.c

#include <semaphore.h>

#include <inttypes.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

sem_t sem;

uint64_t counter1 = 0;

uint64_t counter2 = 0;

pthread_t t1, t2, t3;

void* t1_impl( void* _ ) {

while( counter1 < 10000000 ) counter1++;

sem_post( &sem );

return NULL;

}

void* t2_impl( void* _ ) {

while( counter2 < 20000000 ) counter2++;

sem_post( &sem );

return NULL;

}

void* t3_impl( void* _ ) {

sem_wait( &sem );

sem_wait( &sem );

printf("End: counter1 = %" PRIu64 " counter2 = %" PRIu64 "\n",

counter1, counter2 );

return NULL;

}

int main(void) {

sem_init( &sem, 0, 0 );

pthread_create( &t3, NULL, t3_impl, NULL );

sleep( 1 );

pthread_create( &t1, NULL, t1_impl, NULL );

pthread_create( &t2, NULL, t2_impl, NULL );

sem_destroy( &sem );

pthread_exit( NULL );

return 0;

}

The sem_init function initializes the semaphore

. Its second argument is a flag: 0 corresponds to a process-local semaphore (which can be used by different threads), non-zero value sets up a semaphore visible to multiple processes.3 The third argument sets up the initial semaphore value. A semaphore is deleted using the sem_destroy function. In the example, two counters and three threads are created. Threads t1 and t2 increment the respective counters to 1000000 and 20000000 and then increment the semaphore value sem by calling sem_post. t3 locks itself decrementing the semaphore value twice. Then, when semaphore was incremented twice by other threads, t3 prints the counters into stdout.

The pthread_exit call ensures that the main thread will not terminate prematurely, until all other threads finish their work.

Semaphores come up handy in such tasks as

Forbidding more than n processes to simultaneously execute a code section.

Making one thread wait for another to complete a specific action, thus imposing an order on their actions.

Keeping no more than a fixed number of worker threads performing a certain task in parallel. More threads than needed might decrease performance.

It is not true that a semaphore

with two states is fully analogous to a mutex. Unlike mutex, which can only be unlocked by the same thread that locked it, semaphores can be changed freely by any thread.

We will see another example of the semaphore usage in Listing 17-18 to make two threads start each loop iteration simultaneously (and when the loop body is executed, they wait for other loops to finish an iteration).

Manipulations with semaphores obviously act like both compiler and hardware memory barriers.

For more information on semaphores, refer to the man pages for the following functions:

em_close

sem_destroy

sem_getvalue

sem_init

sem_open

sem_post

sem_unlink

sem_wait

17.10 How Strong Is Intel 64?

Abstract machines with relaxed memory model can be tough to follow. Out of order writes, return values from the future, and speculative reads are confusing. Intel 64 is considered to be usually strong. In most cases, it guarantees quite a few constraints

to be satisfied, including, but not limited to, the following:

Stores are not reordered with older stores.

Stores are not reordered with older loads.

Loads are not reordered with other loads.

In a multiprocessor system, stores to the same location have a total order.

There are also exceptions

, such as the following:

A full list of guarantees can be found in volume 3, section 8.2.2 of [15].

However, according to [15], “reads may be reordered with older writes to different locations but not with older writes to the same location.” So, do not be fooled: memory reorderings do occur. A simple program shown in Listing 17-18 demonstrates the memory reordering done by hardware. It implements an example already shown in Listing 17-4, where there are two threads and two shared variables x and y. The first thread performs store x and load y, the second ones performs store y and load x. The compiler barrier ensures that these two statements are translated into assembly in the same order. As section 17.10 suggests, the stores and loads into independent locations can be reordered

. So, we cannot exclude the hardware memory reordering here, as x and y are independent!

Listing 17-18.

reordering_cpu_mwe.c

#include <pthread.h>

#include <semaphore.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <inttypes.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

sem_t sem_begin0, sem_begin1, sem_end;

int x, y, read0, read1;

void *thread0_impl( void *param )

{

for (;;) {

sem_wait( &sem_begin0 );

x = 1;

// This only disables compiler reorderings:

asm volatile("" ::: "memory");

// The following line disables also hardware reorderings:

// asm volatile("mfence" ::: "memory");

read0 = y;

sem_post( &sem_end );

}

return NULL;

};

void *thread1_impl( void *param )

{

for (;;) {

sem_wait( &sem_begin1 );

y = 1;

// This only disables compiler reorderings:

asm volatile("" ::: "memory");

// The following line disables also hardware reorderings

// asm volatile("mfence" ::: "memory");

read1 = x;

sem_post( &sem_end );

}

return NULL;

};

int main( void ) {

sem_init( &sem_begin0, 0, 0);

sem_init( &sem_begin1, 0, 0);

sem_init( &sem_end, 0, 0);

pthread_t thread0, thread1;

pthread_create( &thread0, NULL, thread0_impl, NULL);

pthread_create( &thread1, NULL, thread1_impl, NULL);

for (uint64_t i = 0; i < 100000; i++)

{

x = 0;

y = 0;

sem_post( &sem_begin0 );

sem_post( &sem_begin1 );

sem_wait( &sem_end );

sem_wait( &sem_end );

if (read0 == 0 && read1 == 0 ) {

printf( "reordering happened on iteration %" PRIu64 "\n", i );

exit(0);

}

}

puts("No reordering detected during 100000 iterations");

return 0;

}

To check it we perform multiple experiments. The

main function

acts as follows:

Initialize threads and two starting semaphores as well as an ending one.

x = 0, y = 0

Notify the threads that they should start performing a transaction.

Wait for both threads to complete the transaction.

Check whether the memory reordering took place. It is seen when both load x and load y returned zeros (because they were reordered to be placed before store s).

If the memory reordering has been detected, we are notified about it and the process exits. Otherwise it tries again from step (2) up to the maximum of 100000 attempts.

Each thread waits for a signal to start from main, performs the transaction, and notifies main about it. Then it starts all over again.

After launching you will see that 100000 iterations are enough to observe a memory reordering.

> gcc -pthread -o ordering -O2 ordering.c

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 128

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 12

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 171

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 80

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 848

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 366

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 273

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 105

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 14

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 5

> ./ordering

reordering happened on iteration 414

It might seem magical, but it is the level lower than the assembly language even that is seen here and that introduces rarely observed (but still persistent) bugs in the software. Such bugs

in multithreaded software are very hard to catch. Imagine a bug appearing only after four months of uninterrupted execution, which corrupts the heap and crashes the program 42 allocations after it triggers! So, writing high-performance multithreaded software in a lock-free manner requires tremendous expertise.

So, what we need to do is to add mfence instruction. Replacing the compiler barrier with a full memory barrier asm volatile( "mfence":::"memory"); solves the problem and the reorderings disappear completely. If we do it, there will be no reorderings detected no matter how many iterations we try.

17.11 What Is Lock-Free Programming?

We have seen how we can ensure the consistency of the operations when working in a multithreaded environment. Every time we need to perform a complex operation on shared data or resources without other threads intervening we lock a mutex that we have associated to this resource or memory chunk.

We say that the code is lock-

free if the following two constraints are satisfied:

In other words, it is a family of techniques that ensure safe manipulation with the shared data without using mutexes.

We almost always expect only a part of the program code to satisfy the lock-free property. For example, a data structure, such as a queue, may be considered lock-free if the functions that are used to manipulate it are lock-free. So, it does not prevent us from locking up completely, but as far as we are calling functions such as enqueue or dequeue, progress will be made.

From the programmer’s perspective, lock-free programming is different from traditional mutex usage because it introduces two challenges that are usually covered by mutexes.

Reorderings. While mutex manipulations imply compiler and hardware memory barriers, without them you have to be specific about where to place memory barriers. You will not want to place them after each statement because it kills performance.

Non-atomic operations. The operations between mutex lock and unlock are safe and atomic in a sense. No other thread can modify the data associated with the mutex (unless there are unsafe data manipulations outside the lock-unlock section). Without that mechanism we are stuck with very few atomic operations, which we will study later in this chapter.

On most modern processors

reads and writes of naturally aligned native types are atomic. Natural alignment means aligning the variable to a boundary that corresponds to its size.

On Intel 64 there is no guarantee that reads and writes larger than 8 bytes are atomic. Other memory interactions are usually non-atomic. It includes, but is not limited to,

16-byte reads and writes performed by SSE (Streaming SIMD Extensions) instructions.

String operations (movsb instruction and the like).

Many operations are atomic on a single-processor system but not in a multiprocessor system (e.g., inc instruction).

Making them atomic requires a special lock prefix to be used, which prevents other processors from doing their own read-modify-write sequence between the stages of the said instructions. An inc <addr> instruction, for instance, has to read bytes from memory and write back their incremented value. Without lock prefix, they can intervene in between, which can lead to a loss of value.

Here are some examples of non-atomic operations:

char buf[1024];

uint64_t* data = (uint64_t*)(buf + 1);

/* not atomic: unnatural alignment */

*data = 0;

/* not atomic: increment can need a read and a write */

++global_aligned_var;

/* atomic write */

global_aligned_var = 0;

void f(void) {

/* atomic read */

int64_t local_variable = global_aligned_var;

}

These cases are architecture-specific. We also want to perform more complex operations atomically (e.g., incrementing the counter). To perform them safely without using mutexes the engineers invented interesting basic operations, such as compare-and-swap (CAS). Once this operation is implemented as a machine instruction on a specific architecture, it can be used in combination with more trivial non-atomic reads and writes to implement many lock-free algorithms

and data structures.

CAS instruction acts as an atomic sequence of operations, described by the following equivalent C function:

bool cas(int* p , int old, int new) {

if (*p != old) return false;

*p = new;

return true;

}

A shared counter, which you are reading and writing back a modified value, is a typical case when we need a CAS instruction to perform an atomical increment or decrement. Listing 17-19 shows a function to perform it.

Listing 17-19.

cas_counter.c

int add(int* p, int add ) {

bool done = false;

int value;

while (!done) {

value = *p;

done = cas(p, value, value + add );

}

return value + add;

}

This example shows a typical pattern, seen in many CAS-based algorithms. They read a certain memory location, compute its modified value, and repeatedly try to swap the new value back if the current memory value is equal to the old one. It fails in case this memory location was modified by another thread; then the whole read-modify-write cycle is repeated.

Intel 64 implements CAS instructions cmpxchg, cmpxchg8b, and cmpxchg16b. In case of multiple processors, they also require a lock prefix to be used.

The instruction cmpxchg is of a particular interest. It accepts two operands: register or memory and a register. It compares rax

4 with the first operand. If they are equal, zf flag is set, the second operand’s value is loaded into the first. Otherwise, the actual value of the first operand is loaded into rax and zf is cleared.

These instructions can be used

as a part of implementation of mutexes and semaphores.

As we will see in section 17.12.2, there is now a standard-compliant way of using compare-and-set operations (as well as manipulating with atomic variables). We recommend sticking to it to prevent non-portable code and use atomics whenever you can. When you need complex operations to be performed atomically, use mutexes or stick with the lock-free data structure implementations done by experts: writing lock-free data structures has proven to be a challenge.

17.12 C11 Memory Model

17.12.1 Overview

Most of the time we want to write code that is correct on every architecture. To achieve that, we base it on the memory model described in the C11 standard. The compiler might implement some operations in a straightforward manner or emit special instructions to enforce certain guarantees, when the actual hardware architecture is weaker.

Contrary to Intel 64, the C11 memory model is rather weak. It guarantees data dependency ordering, but nothing more, so in the classification mentioned in section 17.4 it corresponds to the second one: weak with dependency ordering. There are other hardware architectures that provide similar weak guarantees, for example ARM.

Because of C weakness, to write portable code we cannot assume that it will be executed on an usually strong architecture, such as Intel 64

, for two reasons.

When recompiled for other, weaker architecture, the observed program behavior will change because of how the hardware reorderings work.

When recompiled for the same architecture, compiler reorderings that do not break the weak ordering rules imposed by the standard might occur. That can change the observed program behavior, at least for some execution traces.

17.12.2 Atomics

The important C11 feature that can be used to write fast multithreaded programs is atomics (see section 7.17 of [7]). These are special variable types, which can be modified atomically. To use them, include the header stdatomic.h.

Apparently, an architecture support is needed to implement them efficiently. In the worst-case scenario, when the architecture does not support any such operation, every such variable will be paired with a mutex, which will be locked to perform any modification of the variable or even to read it.

Atomics allow us to perform

thread-safe operations on common data in some cases. It is often possible to do without heavy machinery involving mutexes. However, writing data structures such as queue in a lock-free way is no easy task. For that we highly advise using such existing implementations as “black boxes.”

C11 defines a new _Atomic() type specifier. You can declare an atomic integer as follows:

_Atomic(int) counter;

_Atomic transforms the name of a type into the name of an atomic type. Alternatively, you can use the atomic types directly as follows:

atomic_int counter;

A full correspondence between _Atomic(T) and atomic_T direct type forms can be found in section 7.17.6 of [7].

Atomic local variables should not be initialized directly; instead, the macro ATOMIC_VAR_INIT should be used. It is understandable, because on some architectures with fewer hardware capabilities each such variable should be associated with a mutex, which has to be created and initialized as well. Global atomic variables are guaranteed to be in a correct initial state. ATOMIC_VAR_INIT should be used during the variable declaration coupled with initialization; however, if you want to initialize the variable later, use atomic_init macro.

void f(void) {

/* Initialization during declaration */

atomic_int x = ATOMIC_VAR_INIT( 42 );

atomic_int y;

/* initialization later */

atomic_init( &y, 42 );

}

It is your responsibility to guarantee that the atomic variable initialization ends before anything else is done with it. In other words, concurrent access to the variable being initialized is a data race.

Atomic variables should only be manipulated through an interface, defined in the language standard. It consists of several operations, such as load, store, exchange, etc. Each of them exists in two versions.

An explicit version, which accepts an extra argument, describing the memory ordering

. Its name ends with _explicit. For example, the load operation is

T atomic_load_explicit( _Atomic(T) *object, memory_order order );

An implicit version, which implies the strongest memory ordering (sequentially consistent). There is no _explicit suffix. For example,

T atomic_load( _Atomic(T) *object );

17.12.3 Memory Orderings in C11

The memory ordering

is described by one of enumeration constants (in order of increasing strictness).

memory_order_relaxed implies the weakest model: any memory reordering is possible as long as the single thread program’s observable behavior is left untouched.

memory_order_consume is a weaker version of memory_order_acquire.

memory_order_acquire means that the load operation has an acquire semantics.

memory_order_release means that the store operation has a release semantics.

memory_order_acq_rel combines acquire and release semantics.

memory_order_seq_cst implies that no memory reordering is performed for all operations that are marked with it, no matter which atomic variable is being referenced.

By providing an explicit memory ordering constant, we can control how we want to allow the operations to be observably reordered. It includes both compiler reorderings and hardware reorderings, so when the compiler sees that compiler reorderings do not provide all the guarantees we need, it will also issue platform-specific instructions, such as sfence.

The memory_order_consume option is rarely used. It relies on the notion of “consume operation.” This operation is an event that occurs when a value is read from memory and then used afterward in several operations, creating a data dependency.

In weaker architectures such as PowerPC or ARM its usage can bring a better performance due to exploitation of the data dependencies to impose a certain ordering on memory accesses. This way, the costly hardware memory barrier instruction is spared, because these architectures guarantee the data dependency ordering without explicit barriers. However, due to the fact that this ordering is so hard to implement efficiently and correctly in compilers, it is usually mapped directly to memory_order_acquire, which is a slightly stronger version. We do not recommend using it. Refer to [30] for additional information.

The

acquire

and

release semantics

of these memory ordering options

correspond directly to the notions we studied in section 17.7.

The memory_order_seq_cst corresponds to the notion of sequential consistency, which we elaborated in section 17.4. As all non-explicit operations with atomics accept it as a default memory ordering value, C11 atomics are sequentially consistent by default. It is the safest route and also usually faster than mutexes. Weaker orderings are harder to get right, but they allow for a better performance as well.

The atomic_thread_fence(memory_order order) allows us to insert a memory barrier (compiler and hardware ones) with a strength corresponding to the specified memory ordering. For example, this operation has no effect for memory_order_relaxed, but for a sequentially consistent ordering in Intel 64 the mfence instruction will be emitted (together with compiler barrier).

17.12.4 Operations

The following operations

can be performed on atomic variables (T denotes the non-atomic type, U refers to the type of the other argument for arithmetic operations; for all types except pointers, it is the same as T, for pointers it is ptrdiff_t).

void atomic_store(volatile _Atomic(T)* object, T value);

T atomic_load(volatile _Atomic(T)* object);

T atomic_exchange(volatile _Atomic(T)* object, desired);

T atomic_fetch_add(volatile _Atomic(T)* object, U operand);

T atomic_fetch_sub(volatile _Atomic(T)* object, U operand);

T atomic_fetch_or (volatile _Atomic(T)* object, U operand);

T atomic_fetch_xor(volatile _Atomic(T)* object, U operand);

T atomic_fetch_and(volatile _Atomic(T)* object, U operand);

bool atomic_compare_exchange_strong(

volatile _Atomic(T)* object, T * expected, T desired);

bool atomic_compare_exchange_weak(

volatile _Atomic(T)* object, T * expected, T desired);

All these operations can be used with an _explicit suffix to provide a memory ordering as an additional argument.

Load and store functions do not need a further explanation; we will discuss the other ones briefly.