12. Adopting a Completely New Workflow

If you’ve stuck around this long, congratulations! You have all the pieces of a significantly different workflow. That’s probably both very exciting and incredibly scary. I remember the first time we tried element collages at WSOL and were so proud that we’d adopted a new technique. It wasn’t long after we started making the first one that I also began to worry about spending too much time on them and thinking, “What happens if the client doesn’t get it?”

There are no easy answers to some of the transitional questions that come from hammering out a completely new workflow. This chapter is dedicated to taking a look at how all of the techniques in this book come together and, more importantly, how to institute these changes internally and externally.

Looking Back at Moving Forward

We’ve covered a lot, and it’s easy to lose sight of where everything fits into a process. As we take a quick look back, keep in mind that the takeaways aren’t necessarily technical but conceptual. While there’s no Make This Responsive button in Photoshop, you can employ intelligent methods of design that make the RWD process more efficient.

Full-Page Photoshop Comps Are Disharmonious with RWD

It’s certainly not an absolute rule, but full-page, static comps do very little to help our clients and stakeholders understand the complexities of responsive web design. We’re able to show only one moment in time through full-page comps, and any attempt at showing every potential moment, or at least multiple ones, is futile. The static nature of comps also hinders our ability to show design behaviors such as animation, transitions, transforms, hover effects, and more.

Designing in the Browser Helps, But Not As Much As We’d Like

The browser has proven itself to be a more appropriate home for web design, and CSS has come a long way to now supporting just about any effect you can pull of in Photoshop. Theoretically, we could kill Photoshop and use code 100 percent of the time. The reality is that many of us have difficulty overcoming how code is a layer abstracted from the direct manipulation we loved in Photoshop. The result is our designs look boxy and bland and are often hard to distinguish from the rest of the industry.

2 Cups Browser, 1 Cup Photoshop

Direct manipulation makes Photoshop a great environment for ideation, but the browser is the rightful home for executing and implementing the majority of our design decisions and, more importantly, testing and evaluating them. Using one entity in moderation can help overcome where the other falls short. There’s no longer a clear division between the “Photoshop phase” and the “development phase.” For efficiency and accuracy, it’s imperative we weave between both environments as needed.

Vetting Direction Efficiently Is Critical

What worked in doing three full-page comps was that it provided a semblance of choice between distinct directions. Though we aim to be agile and flexible, exploring multiple directions is still valuable. Exercises such as moodboards and visual inventories help bring our project teams into the process of defining the most appropriate direction up front so we can continually refine as we work toward a finished site

Style Can Be Established Through Small Exercises

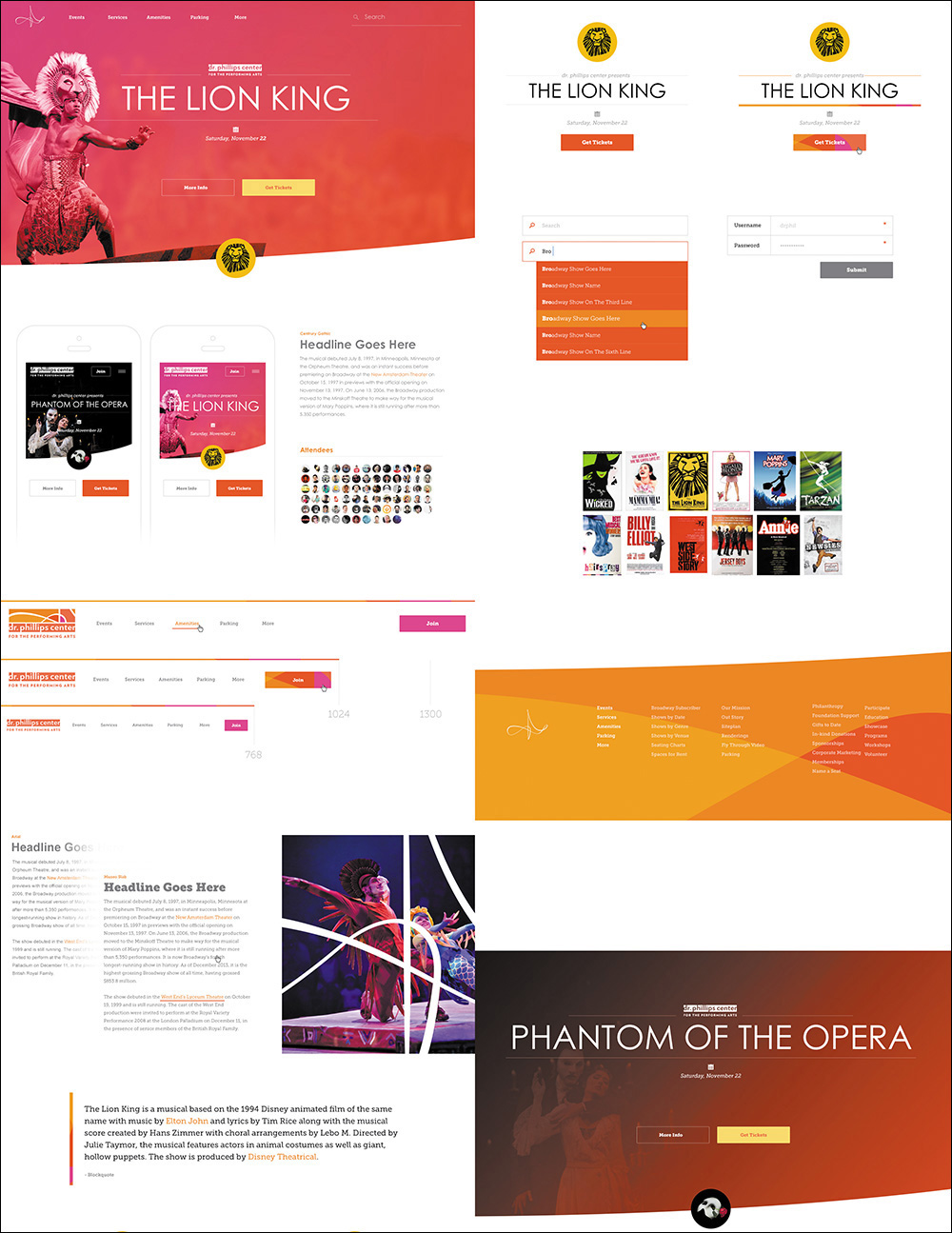

Full-page comps were a bear to create, especially if we tried to show multiple pages at multiple sizes. Rarely does a footer or ad block inspire the entire direction of a site, so why figure out the pixel-perfect details now? Instead, exploration through style tiles, style prototypes, and element collages help establish style without needing to define such minutiae (see Figure 12.1). Better yet, they help us frame the style of an entire system rather than a specific page.

Page-Building Is Easier with Component-Based Systems

While it’s true that we’re eventually implementing pages in web design, focusing on the design and style specifications for a homepage often causes us to ignore those for interior pages. The propensity to “one-off” a component to fit the page is fairly high, which can contribute to an inconsistent experience across the site. By establishing components prior to pages, we collect all the Legos we’ll need for building castles, cars, and pretty much anything else we’ll ever need.

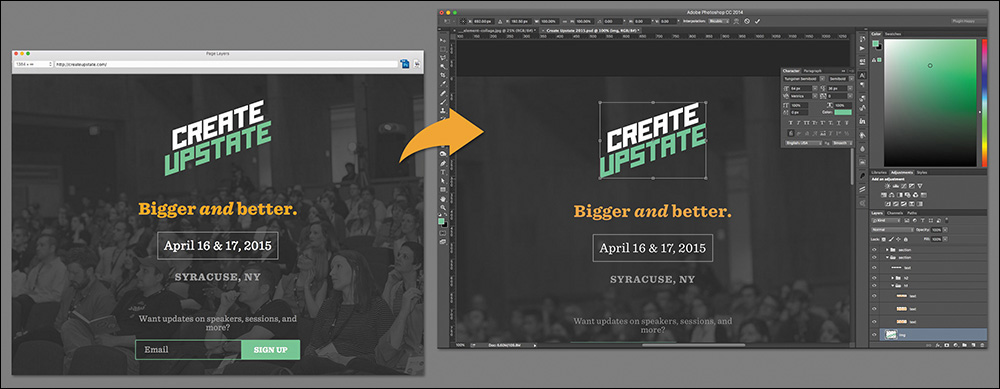

Page Layers Makes Going from HTML to Photoshop Simple

Getting stuck in CSS is fairly common for most designers. Staring at code isn’t the best way to breed creativity and ingenuity. Although we don’t have page comps to revert to, we can take chunks or entire pages from the browser back into a fully layered PSD with Page Layers (see Figure 12.2). Some quick “sketching” from there should help us think through unique solutions rather than rely on ones we’re used to executing through code.

New Extraction Tools Get Us Back to the Browser Quicker

If we’re continually going back and forth between Photoshop and the browser, we can’t stumble getting in and out of either. Page Layers helps us go from HTML to PSD, but until recently there was no quick way to export our artwork. Photoshop CC has introduced two great features called Generator and Extract Assets to address this pain point, and Extract in the browser can help developers glean top-level style information without ever needing to open Photoshop.

We Can Customize Photoshop for RWD with Useful Third-Party Extensions

When we get used to a particular workflow, it’s easy to accept things as they are and not be aware of the potential time-saving tools that take a little digging to unearth. Through the help of clever third-party extensions, you can build a customized Photoshop that addresses the majority of our pain points, including some of the RWD-specific ones we’re discovering every day.

A Little Etiquette Goes a Long Way

No matter how slick we are individually in Photoshop, disorganization and a lack of consideration to others on our team might be crippling our workflows. With all of the moving pieces in a responsive workflow, clarity in our artwork should never be an issue since we can control it fairly easily. Naming layers, being nondestructive with our images, and wrangling type decisions can help PSD inheritors get in and out of your work in no time.

On Adoption

The first major design conference I attended was Future of Web Design NYC 2011. I traveled with my creative director and front-end developer, and the ideas shared on stage were so mind-blowing that they produced copious amounts of excitement among the three of us. In fact, we spent the car ride back up to Syracuse engaged in nonstop plotting about all the things we vowed to change in our current process, which we were all in agreement about.

We got back to work that Monday chomping at the bit, ready to share what we’d learned through the lens of “Here are all the things we need to start doing.” I vividly recall the first companywide meeting being well-received, so we held another one a week later on changing how we wireframe and prototype. What we didn’t expect was that a few people were so agitated that we wanted to change how they did things that they stormed out of the room not even halfway through the meeting.

Tip

Don’t go it alone if you don’t have to. Pushing for organizational and/or process change is a task best suited for groups. Sometimes, finding just one other advocate can help establish credibility for your claim, while also creating a sense of accountability for both of you to keep the momentum going. Try finding a co-worker or colleague who can help you assess and challenge new workflow strategies so you’ll be prepared to convince others.

I say this not to temper your excitement about visual inventories or element collages but to warn you that radical process changes aren’t always popular internally and externally. It’s critical that you don’t lose your excitement for experimenting with new workflows, but driving change is going to take more than a few efforts to make happen.

When we talk about transforming your process from full-page comps to designing in the browser and element collages, take a moment and realize how many facets of your current workflow and organization that new approach will affect: You need to bill differently. You need to adjust project timelines. You need to bring developers in earlier and keep designers on later. Tinkering with your business model or your company’s can be difficult.

These aren’t subtle shifts. These are major considerations, most of which take time to facilitate. If you don’t find they’re worth it in the end, you will have done a lot of reshuffling for not much return on investment.

While it’s easier to suggest change when a process is completely broken, most design teams have processes that are adequate but in need of better efficiency. The sell can be a hard one, but it’s rewarding if you care about designing responsively.

Strategies for Getting Buy-in Internally

Before you can illustrate the effectiveness of moodboards or style prototypes to your clients, you need to be sold on them internally. Your job as Chief Workflow Transformer is to present a compelling case to the people you work with. If you work on your own, you’ll still want to be sure you’re thoroughly convinced (which I hope you are).

Here are some effective methods for obtaining buy-in within your company.

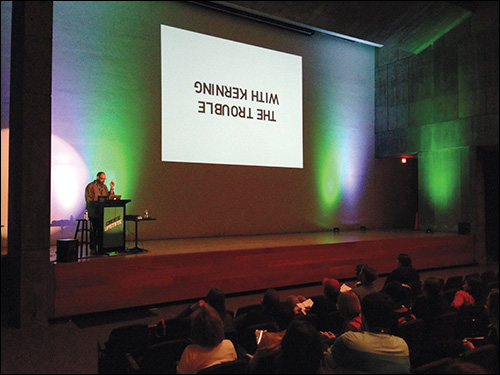

Give Presentations

A good sell rarely starts with disclaimers or stating reasons for concern. You need to start with the good stuff, the stuff that convinced you in the first place. You may not be the best presenter or think you have an audience for this material, but trust me, you do (see Figure 12.3).

Start by putting together a presentation. Use whatever tool you’re most comfortable with; for me, it’s Keynote. One of the most effective ways I’ve found to drive home the need for a better process is to weave back and forth between pain points and remedies. The tone you want to establish isn’t “Here are all the things we do wrong, and here’s how to do them right.” Rather, you want something more along the lines of “Here are some areas we can be even more efficient in, and here are some ways to get there.” Nobody responds well when they feel like they’re being attacked, so try to convey your message as helping rather than criticizing.

In any case, presenting organized material to your team should alert them that you’re serious about this making some change.

Set Realistic Expectations

After delivering the goods, it’s worthwhile to convey that you don’t expect changes overnight. You shouldn’t; there’s still a lot of figuring out to do even if everyone is on board. In a waterfall process where a designer produces comps and hands them off to a developer, the roles and their timing are clear. In a process where we jump back and forth between the browser and Photoshop, the monthly hand-offs change to daily conversations that require a little ideation, some development, and testing. That makes an impact on everyone’s daily schedules and routines.

I heard of one design agency that, upon adopting a new responsive process, restructured their office. Since the traditional divide between designers and developers creates inefficiencies when going from idea to code, they sat developers next to designers. The thinking was that if both parties were in better proximity to one another, they would find it easier to tackle responsive issues from both angles instead of one and then the other.

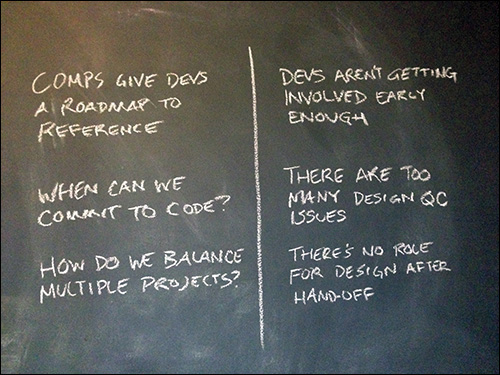

It’s prudent to have a group discussion about potential concerns before jumping into a completely restructured workflow (see Figure 12.4): How will we bill for this? Will anyone’s roles change? How quickly can we make a visual inventory? All of these questions can’t be resolved without some trial and error, but the hope is that understanding that it’ll take a bit of figuring out should disarm anyone from stating that it’s not possible. It’s your job to communicate why it’s worth it.

Figure 12.4 Have a round-table discussion about the pros and cons to adopting new methods, and encourage everyone to voice any concerns.

Work the Food Chain

Begin by presenting your new RWD methods to the people with whom you work most directly. You want to get buy-in from the people in roles most similar to yours. In doing so, you create allies for trying to convince bigger fish in your organization. Failure to get fellow designers and developers on board before approaching C-level folks means you run the risk of alienating your colleagues, who may not be on board with everything you present.

With a small group of supporters established, refine and tailor your presentation to others. They may have different interests than designers, so address those. For instance, it may be worth highlighting how a new workflow would facilitate better client communication.

Attend Conferences

It’s hard to argue with anyone who is up-to-date, and almost everyone respects those who willingly seek learning opportunities such as those found at industry conferences. You won’t return as an expert on all aspects of design, but attending conferences establishes you as connected to the design community. There’s authority in that.

When you make workflow pitches and presentations, stating examples and insight from conferences goes a long way in establishing objective credibility (see Figure 12.5 on the next page). If you can describe best practices used successfully by designers elsewhere, your audience will be less likely to regard your pitch as completely subjective. Attend conferences as often as you can, and report back to your team how other designers are tackling the same problems you have.

You want your team excited to try a few new things. Openly discuss the merits of various approaches and workflow tweaks to get everyone on board and advocating for change. You’re looking for unbridled enthusiasm, not passive agreement.

Strategies for External Getting Buy-In

Once you have buy-in from the team, it’s time to reach out to your clients and stakeholders, who likely haven’t ever dealt with anything outside of receiving three full-page comps for sign-off. Don’t underestimate this fact: Your customer may take pride in equating this traditional approach with how web design works. Making your pitch successful may require some rewiring and education.

Reset Expectations

When I got my driveway installed, I had only one point of reference for how it was typically done and was reluctant to take the contractor at his word when he suggested paving it in two phases instead of all at once. He said this isn’t how everyone does it, or even how he’s always done it, but he’s found that it produces a driveway that lasts longer. Up to this point, I had always thought paving a driveway was simple: You pour some asphalt down, smooth it, and walk away forever. According to my contractor, this approach is problematic.

It’s highly possible that he duped me. What he did establish, however, is that he’s the expert and has a reason for doing something I might not be familiar with. I respect that and feel our design clients do as well. Visual inventories and component libraries aren’t familiar to them, but if we sell the value of their role in a responsive project, we have decent odds of convincing them to abandon the comp approach they likely experienced last time they had their site redesigned.

Outlining the timing and role of every exercise in your new process goes a long way toward gaining the trust of your client. If you substitute element collages for full-page comps without giving them any warning, they’ll probably be confused as to what they are and why they help the process. Start by providing a road map of every design conversation you plan on having from project kickoff to project delivery.

Increase Communication and Involvement

As you learned in Chapters 5 and 6, bringing your clients and stakeholders into the design process can be a foreign concept if you’re used to presenting work for approval. But it’s an effective approach, and I’d even argue a necessary one for a responsive workflow; you need their input for design direction and decisions throughout the entire process, so it doesn’t make sense to work in a silo between milestones.

Providing opportunities for clients to be involved will help you get external buy-in to a new process. If your clients continually feel like a valued part of finding the solution—which they should be—they’ll be less resistant to trying new methods. When they try to cling to traditional approaches, present them with the option of contributing to the success of a new method: We’d love to try style tiles because they’ll get us into a direction more quickly. Would you mind helping us find a few viable approaches? This should get them excited to participate.

Tip

Don’t be afraid to engage your clients with exercises similar to the ones we designers use. Sketching sessions, however rough, can help clients communicate their perspectives in terms you’re familiar with, especially if their industry may not be so familiar to you.

When framed as an attempt to stay on top of the increasingly moving target the Web has become, new approaches and the opportunity to contribute to them should appeal to both us and the ones we work for.

Affirm Where Things Are Going

A traditional process has clear objectives for its deliverables. A design comp leads to an HTML & CSS rendering, which leads to a CMS implementation. Relying on small exercises to define design direction and style exploration can make it harder to see where all of it is going.

One of the best ways to curb frustration is to continually set up what you’ve done so far, what you’re currently doing, and how it will impact the next part of the project. For example, “Last time, we had a great conversation about some viable directions to explore looking at the visual inventory. We’ve taken that input and crafted some element collages to discuss today. This discussion will help us continue to define the course we’re on and determine what styles are most appropriate moving forward when we produce high-fidelity prototypes of a few templates to review.”

Communicate with your clients and stakeholders how the input they supply helps shape the direction of each exercise. Set a framework for the kind of feedback you’ll need for the next step.

What Happens When Things Go Wrong

Just because any of the strategies in this book seem better than comps doesn’t mean they’re safe from trouble. The next few sections describe some of the heavier issues that might arise.

The Client Can’t Settle on a Direction

If your client responds to every visual inventory characteristic or element collage exploration with “That seems like it would work,” the root cause can be hard to nail down. Yes, you may have presented some stunning options and made it an objectively difficult decision to start paring down, but it’s also possible you haven’t given them not enough differentiation between the options.

It’s OK if two directions are determined to be viable in a visual inventory. Go forth and explore them. However, you should be able to pit the advantages of one against the other the clearer the directions come into view: Do you think your users will appreciate the active color palette’s connection to your logo? Asking critical questions about each direction may help your client articulate how appropriate each one is.

Remember, your client is an expert in their field just as you are in yours. Try asking questions that require them to lean on their knowledge of their customer base. With their customers in mind, it may be easier to vet which direction is more appropriate.

The Element Collage Misses the Mark Entirely

Just like full-page comps, the execution of element collages has the potential to fall short of client expectations. Try not to get stuck in a loop of editing an element collage based on requests like “Change the blue to red, and bring the header up a little bit.” This kind of feedback won’t allow a direction to evolve; it just communicates to a client that they have the authority to make specific design edits.

Instead, poor input received from a moodboard or visual inventory could be the root cause. Don’t blame your client. It could be a product of poor questions on your part. In any event, revisit what was established in these conversations again to ensure you’re on the right track. Then, pair the feedback against what you explored in Photoshop. If you’re missing the mark on execution, ask your client to better articulate what it is that doesn’t align like they hoped.

Should you need to drastically adjust an element collage, take solace in the fact that doing so takes only a fraction of the time full-page mockups do. Trashing a 20-hour comp leads to much misery. Trashing a six-hour element collage, while not ideal, is still a relatively small course of action to get back on track.

Designer/Developer Discord Still Exists

Involving developers earlier and designers later isn’t always going to result in everyone singing “Kumbaya.” Frustrations with designers not understanding how code works and developers not being able to color their way out of a wet paper bag may still exist after you thought uniting everyone on a new workflow was a good thing. Don’t worry, it was; but fostering effective designer/developer communication is a whole other animal.

Etiquette will help, as will more frequent interactions and conversations. The hope is that both of these will give you an opportunity for better understanding of design and development techniques and methodologies. You’ll reach true harmony when you succeed in blurring the line between which person is capable of doing what. A designer who codes effectively and a developer capable of making intelligent design decisions make for a powerful team, but don’t expect it to happen overnight if it doesn’t already exist. It’ll come.

Adjusting Your Perspective on Tools

In writing this book, I’ve experienced an epiphany of sorts about Photoshop in a responsive process. It’s hard to justify keeping it around, though I’d like to believe I’ve made a strong case for doing so, and I hope I’ve helped you see how advantage it is to do so. Even so, tools that aim to replace it will continue to come.

My advice is to continue to entertain such alternatives because staying open at this juncture of the Web’s evolution is essential to keeping up with it. But you should also assess how you use your tools as viable alternatives.

Repurposing Tools May Be Better Than Getting New Ones

With new tools and techniques popping up seemingly every day, there has never been a better time to assess the tools and techniques you currently employ. It may take turning Photoshop and how you use it on its head, but the result is that it addresses RWD process pain points in ways that other tools can’t—for me, anyway.

Those words, “for me,” are critical to adopting a successful responsive workflow. There’s no single approach that stands above the others for everyone because the situations, clients, and projects a designer encounters can vary so greatly. Find what works for you, share it, and continually improve on it.

To move web design forward, you need to ask the question, “How can I use the tools I have to solve this problem?” rather than, “What tool solves all of the problems I have?” The distinction is crucial to being innovative or simply chasing the newest app of the week.

Train yourself to be a critical thinker, a professional interrogator, and a problem solver. Allow your process to reflect that. In doing so, you’ll find our friend Photoshop to be of great use, and the more unconventionally you use it, the better it will serve you.