iptables consists of four tables of rules, each with its own distinct purpose:

- Filter table: For basic protection of our servers and clients, this is the only table that we would normally use

- NAT table: Network Address Translation (NAT) is used to connect the public internet to private networks

- Mangle table: This is used to alter network packets as they go through the firewall

- Security table: The security table is only used for systems that have SELinux installed

Since we're currently only interested in basic host protection, we'll only look at the filter table. Each table consists of chains of rules, and the filter table consists of the INPUT, FORWARD, and OUTPUT chains. Since our CentOS 7 machine uses Red Hat's firewalld, we'll look at this on our Ubuntu machine.

However, if your organization is still running its network with version 6 of either Red Hat or CentOS, then your machines are still running with iptables, since firewalld isn't available for them.

We'll first look at our current configuration with sudo iptables -L command:

donnie@ubuntu:~$ sudo iptables -L

[sudo] password for donnie:

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

donnie@ubuntu:~$

And remember, we said that you need a separate component of iptables to deal with IPv6. Here we will use sudo ip6tables -L command:

donnie@ubuntu:~$ sudo ip6tables -L

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

donnie@ubuntu:~$

In both cases, you see that there are no rules, and that the machine is wide open. Unlike the SUSE and Red Hat folk, the Ubuntu folk expect you to do the work of setting up a firewall. We'll start by creating a rule that will allow the passage of incoming packets from servers to which our host has requested a connection:

sudo iptables -A INPUT -m conntrack --ctstate ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT

Here's the breakdown of this command:

- -A INPUT: The -A places a rule at the end of the specified chain, which in this case is the INPUT chain. We would have used a -I had we wanted to place the rule at the beginning of the chain.

- -m: This calls in an iptables module. In this case, we're calling in the conntrack module for tracking connection states. This module allows iptables to determine whether our client has made a connection to another machine, for example.

- --ctstate: The ctstate or connection state, portion of our rule is looking for two things. First, it's looking for a connection that the client established with a server. Then, it looks for the related connection that's coming back from the server, in order to allow it to connect to the client. So, if a user were to use a web browser to connect to a website, this rule would allow packets from the web server to pass through the firewall to get to the user's browser.

- -j: This stands for jump. Rules jump to a specific target, which in this case is ACCEPT. (Please don't ask me who came up with this terminology.) So, this rule will accept packets that return from the server with which the client has requested a connection.

Our new ruleset looks like this:

donnie@ubuntu:~$ sudo iptables -L

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

ACCEPT all -- anywhere anywhere ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED

Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

donnie@ubuntu:~$

We'll next open up port 22 in order to allow us to connect through Secure Shell. For now, we don't want to open any more ports, so we'll finish this with a rule that blocks everything else:

sudo iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport ssh -j ACCEPT

sudo iptables -A INPUT -j DROP

Here's the breakdown:

- -A INPUT: As before, we want to place this rule at the end of the INPUT chain with a -A.

- -p tcp: The -p indicates the protocol that this rule affects. This rule affects the TCP protocol, of which Secure Shell is a part.

- --dport ssh: When an option name consists of more than one letter, we need to precede it with two dashes, instead of just one. The --dport option specifies the destination port on which we want this rule to operate. (Note that we could also have listed this portion of the rule as --dport 22, since 22 is the number of the SSH port.)

- -j ACCEPT: Put it all together with -j ACCEPT, and we have a rule that allows other machines to connect to this one through Secure Shell.

- The DROP rule at the end silently blocks all connections and packets that aren't specifically allowed in by our two ACCEPT rules.

- sudo iptables -A INPUT -j DROP: It causes the firewall to silently block packets, without sending any notification back to the source of those packets.

- sudo iptables -A INPUT -j REJECT: It would also cause the firewall to block packets, but it would also send a message back to the source about the fact that the packets have been blocked. In general, it's better to use DROP, because we normally want to make it harder for malicious actors to figure out what our firewall configuration is.

Finally, we have an almost complete, usable ruleset for our INPUT chain:

donnie@ubuntu:~$ sudo iptables -L

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

ACCEPT all -- anywhere anywhere ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED

ACCEPT tcp -- anywhere anywhere tcp dpt:ssh

DROP all -- anywhere anywhere

Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

donnie@ubuntu:~$

It's almost complete, because there's still one little thing that we forgot. That is, we need to allow traffic for the loopback interface. That's okay, because it gives us a good chance to see how to insert a rule where we want it, if we don't want it at the end. In this case, we'll insert the rule at INPUT 1, which is the first position of the INPUT chain:

sudo iptables -I INPUT 1 -i lo -j ACCEPT

When we look at our new ruleset, we'll see something that's rather strange:

donnie@ubuntu:~$ sudo iptables -L

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

ACCEPT all -- anywhere anywhere

ACCEPT all -- anywhere anywhere ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED

ACCEPT tcp -- anywhere anywhere tcp dpt:ssh

DROP all -- anywhere anywhere

Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

donnie@ubuntu:~$

Hmmm...

The first rule and the last rule look the same, except that one is a DROP and the other is an ACCEPT. Let's look at it again with the -v option:

donnie@ubuntu:~$ sudo iptables -L -v

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT 0 packets, 0 bytes)

pkts bytes target prot opt in out source destination

0 0 ACCEPT all -- lo any anywhere anywhere

393 25336 ACCEPT all -- any any anywhere anywhere ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED

0 0 ACCEPT tcp -- any any anywhere anywhere tcp dpt:ssh

266 42422 DROP all -- any any anywhere anywhere

Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT 0 packets, 0 bytes)

pkts bytes target prot opt in out source destination

Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT 72 packets, 7924 bytes)

pkts bytes target prot opt in out source destination

donnie@ubuntu:~$

Now, we see that lo, for loopback, shows up under the in column of the first rule, and any shows up under the in column of the last rule. This all looks great, except that if we were to reboot the machine right now, the rules would disappear. The final thing that we need to do is make them permanent. There are several ways to do this, but the simplest way to do this on an Ubuntu machine is to install the iptables-persistent package:

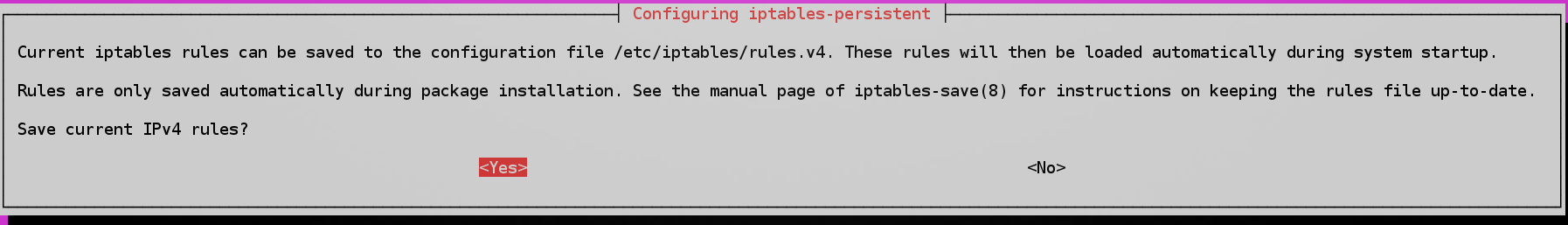

sudo apt install iptables-persistent

During the installation process, you'll be presented with two screens that ask whether you want to save the current set of iptables rules. The first screen will be for IPv4 rules, and the second will be for IPv6 rules:

You'll now see two new rules files in the /etc/iptables directory:

donnie@ubuntu:~$ ls -l /etc/iptables*

total 8

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 336 Oct 10 10:29 rules.v4

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 183 Oct 10 10:29 rules.v6

donnie@ubuntu:~$

If you were to now reboot the machine, you'd see that your iptables rules are still there and in effect.