The following are two reasons why you would want to keep track of what network services are running on your system:

- To ensure that no legitimate network services that you don't need are running

- To ensure that you don't have any malware that's listening for network connections from its master

The netstat command is both handy and easy to use for these instances. First, let's say that you want to see a list of network services that are listening, waiting for someone to connect to them:

donnie@linux-0ro8:~> netstat -lp -A inet

(Not all processes could be identified, non-owned process info

will not be shown, you would have to be root to see it all.)

Active Internet connections (only servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 0 0 *:ideafarm-door *:* LISTEN -

tcp 0 0 localhost:40432 *:* LISTEN 3296/SpiderOakONE

tcp 0 0 *:ssh *:* LISTEN -

tcp 0 0 localhost:ipp *:* LISTEN -

tcp 0 0 localhost:smtp *:* LISTEN -

tcp 0 0 *:db-lsp *:* LISTEN 3246/dropbox

tcp 0 0 *:37468 *:* LISTEN 3296/SpiderOakONE

tcp 0 0 localhost:17600 *:* LISTEN 3246/dropbox

tcp 0 0 localhost:17603 *:* LISTEN 3246/dropbox

udp 0 0 *:57228 *:* 3376/plugin-contain

udp 0 0 192.168.204.1:ntp *:* -

udp 0 0 172.16.249.1:ntp *:* -

udp 0 0 linux-0ro8:ntp *:* -

udp 0 0 localhost:ntp *:* -

udp 0 0 *:ntp *:* -

udp 0 0 *:58102 *:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 *:db-lsp-disc *:* 3246/dropbox

udp 0 0 *:43782 *:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 *:36764 *:* -

udp 0 0 *:21327 *:* 3296/SpiderOakONE

udp 0 0 *:mdns *:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 *:mdns *:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 *:mdns *:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 *:mdns *:* -

raw 0 0 *:icmp *:* 7 -

donnie@linux-0ro8:~>

The breakdown is as follows:

- -lp: The l means that we want to see which network ports are listening. In other words, we want to see which network ports are waiting for someone to connect to them. The p means that we want to see the name and process ID number of the program or service that is listening on each port.

- -A inet: This means that we only want to see information about the network protocols that are members of the inet family. In other words, we want to see information about the raw, tcp, and udp network sockets, but we don't want to see anything about the Unix sockets that only deal with interprocess communications within the operating system.

Since this output is from the OpenSUSE workstation that I just happen to be using at the moment, you won't see any of the usual server-type services here. However, you do see a few things that you likely won't want to see on your servers. For example, let's look at the very first item:

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 0 0 *:ideafarm-door *:* LISTEN -

The Local Address column specifies the local address and port of this listening socket. The asterisk means that this socket is on the local network, and ideafarm-door is the name of the network port that is listening. (By default, netstat will show you the names of ports whenever possible, by pulling the port information out of the /etc/services file.)

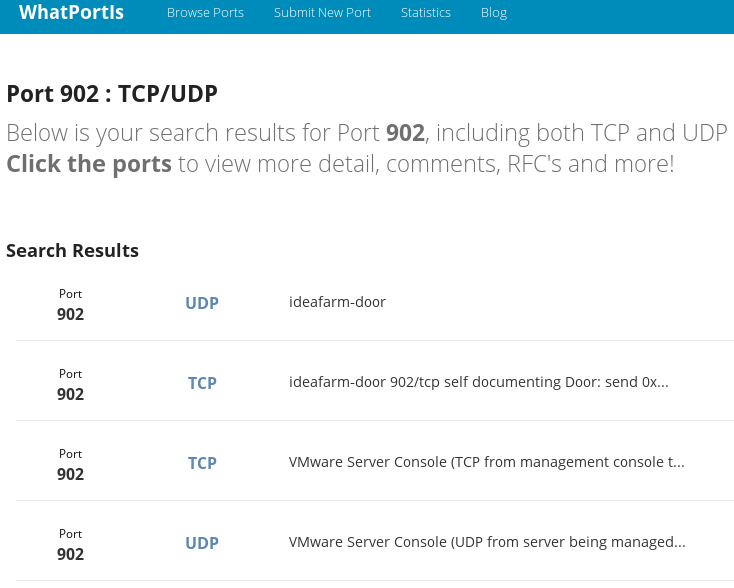

Now, because I didn't know what the ideafarm-door service is, I used my favorite search engine to find out. By plugging the term ideafarm-door into DuckDuckGo, I found the answer:

The top search result took me to a site named WhatPortIs. According to this, the ideafarm-door is in reality port 902, which belongs to the VMware Server Console. Okay, that makes sense because I do have VMware Player installed on this machine. So, that's all good.

Next on the list is:

tcp 0 0 localhost:40432 *:* LISTEN 3296/SpiderOakONE

This item shows the local address as localhost and that the listening port is port 40432. This time, the PID/Program Name column actually tells us what this is. SpiderOak ONE is a cloud-based backup service that you might or might not want to see running on your server.

Now, let's look at a few more items:

tcp 0 0 *:db-lsp *:* LISTEN 3246/dropbox

tcp 0 0 *:37468 *:* LISTEN 3296/SpiderOakONE

tcp 0 0 localhost:17600 *:* LISTEN 3246/dropbox

tcp 0 0 localhost:17603 *:* LISTEN 3246/dropbox

Here, we see that Dropbox and SpiderOak ONE are both listed with the asterisk for the local address. So, they're both using the local network address. The name of the port for Dropbox is db-lsp, which stands for Dropbox LAN Sync Protocol. The SpiderOak ONE port doesn't have an official name, so it's just listed as port 37468. The bottom two lines show that Dropbox also uses the local machine's address, on ports 17600 and 17603.

So far we've looked at nothing but TCP network sockets. Let's see how they differ from UDP sockets:

udp 0 0 192.168.204.1:ntp *:* -

udp 0 0 172.16.249.1:ntp *:* -

udp 0 0 linux-0ro8:ntp *:* -

The first thing to note is that there's nothing under the State column. That's because with UDP, there are no states. They actually are listening for data packets to come in, and they're ready to send data packets out. But since that's about all that UDP sockets can do, there was really no sense in defining different states for them.

In the first two lines, we see some strange local addresses. That's because I have both VMware Player and VirtualBox installed on this workstation. The local addresses of these two sockets are for the VMware and VirtualBox virtual network adapters. The last line shows the hostname of my OpenSUSE workstation as the local address. In all three cases, the port is the Network Time Protocol port, for time synchronization.

Let's now look at one last set of UDP items:

udp 0 0 *:58102 *:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 *:db-lsp-disc *:* 3246/dropbox

udp 0 0 *:43782 *:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 *:36764 *:* -

udp 0 0 *:21327 *:* 3296/SpiderOakONE

udp 0 0 *:mdns *:* 5598/chromium --pas

Here, we see that my Chromium web browser is ready to accept network packets on a few different ports. We also see that Dropbox uses UDP to accept discovery requests from other local machines that have Dropbox installed. I assume that port 21327 performs the same function for SpiderOak ONE.

Of course, since this machine is my workhorse workstation, Dropbox and SpiderOak ONE are almost indispensable to me. I installed them myself, so I've always know that they were there. However, if you see anything like this on a server, you'll want to investigate to see if the server admins know that these programs are installed, and then find out why they're installed. It could be that they're performing a legitimate function, and it could be that they're not.

If you want to see port numbers and IP addresses instead of network names, add the n option. We have the following code:

donnie@linux-0ro8:~> netstat -lpn -A inet

(Not all processes could be identified, non-owned process info

will not be shown, you would have to be root to see it all.)

Active Internet connections (only servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:902 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN -

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:40432 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 3296/SpiderOakONE

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:22 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN -

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:631 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN -

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:25 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN -

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:17500 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 3246/dropbox

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:37468 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 3296/SpiderOakONE

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:17600 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 3246/dropbox

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:17603 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 3246/dropbox

udp 0 0 192.168.204.1:123 0.0.0.0:* -

udp 0 0 172.16.249.1:123 0.0.0.0:* -

udp 0 0 192.168.0.222:123 0.0.0.0:* -

udp 0 0 127.0.0.1:123 0.0.0.0:* -

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:123 0.0.0.0:* -

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:17500 0.0.0.0:* 3246/dropbox

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:50857 0.0.0.0:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:43782 0.0.0.0:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:44023 0.0.0.0:* 10212/plugin-contai

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:36764 0.0.0.0:* -

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:21327 0.0.0.0:* 3296/SpiderOakONE

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:5353 0.0.0.0:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:5353 0.0.0.0:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:5353 0.0.0.0:* 5598/chromium --pas

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:5353 0.0.0.0:* -

raw 0 0 0.0.0.0:1 0.0.0.0:* 7 -

donnie@linux-0ro8:~>

All you have to do to view the established TCP connections is to leave out the l option. On my workstation, this makes for a very long list, so I'll only show a few items:

donnie@linux-0ro8:~> netstat -p -A inet

(Not all processes could be identified, non-owned process info

will not be shown, you would have to be root to see it all.)

Active Internet connections (w/o servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 1 0 linux-0ro8:41670 ec2-54-88-208-223:https CLOSE_WAIT 3246/dropbox

tcp 0 0 linux-0ro8:59810 74-126-144-106.wa:https ESTABLISHED 3296/SpiderOakONE

tcp 0 0 linux-0ro8:58712 74-126-144-105.wa:https ESTABLISHED 3296/SpiderOakONE

tcp 0 0 linux-0ro8:caerpc atl14s78-in-f2.1e:https ESTABLISHED 10098/firefox

. . .

. . .

The Foreign Address column shows the address and port number of the machine at the remote end of the connection. The first item shows that the connection with a Dropbox server is in a CLOSE_WAIT state. This means that the Dropbox server has closed the connection, and we're now waiting on the local machine to close the socket.

Because the names of those foreign addresses don't make much sense, let's add the n option to see IP addresses instead:

donnie@linux-0ro8:~> netstat -np -A inet

(Not all processes could be identified, non-owned process info

will not be shown, you would have to be root to see it all.)

Active Internet connections (w/o servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 0 1 192.168.0.222:59594 37.187.24.170:443 SYN_SENT 10098/firefox

tcp 0 0 192.168.0.222:59810 74.126.144.106:443 ESTABLISHED 3296/SpiderOakONE

tcp 0 0 192.168.0.222:58712 74.126.144.105:443 ESTABLISHED 3296/SpiderOakONE

tcp 0 0 192.168.0.222:38606 34.240.121.144:443 ESTABLISHED 10098/firefox

. . .

. . .

This time we see something new. The first item shows a SYN_SENT state for the Firefox connection. This means that the local machine is trying to establish a connection to the foreign IP address. Also, under Local Address, we see the static IP address for my OpenSUSE workstation.

If I had space to display the entire netstat output here, you'd see nothing but tcp under the Proto column. That's because the UDP protocol doesn't establish connections in the same way that the TCP protocol does.

If you need more information about netstat, see the netstat man page.