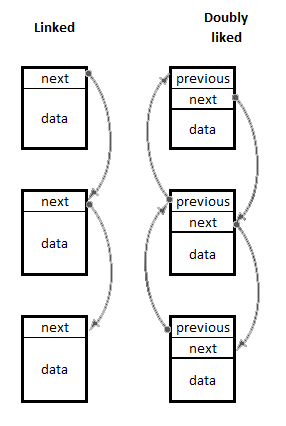

Linked lists, as the name suggests, consists, of data items (nodes) that are linked to one another by means of pointers. Basically, there are two types of linked lists:

- Linked list: This is where each node has a pointer to the following node

- Doubly linked list: This is where each node has a pointer to the following and previous nodes

The following diagram illustrates the difference:

Linked lists of both types may be addressed in a few ways. Obviously, there is at least a pointer to the first node of the list (called top), which is optionally accompanied by a pointer to the last node of the list (called tail). There is, of course, no limit to the amount of auxiliary pointers, should there be a need for such. Pointer fields in the nodes are typically referred to as next and previous. As we can see in the diagram, the last node of a linked list and the first and the last nodes of a doubly linked list have next, previous, and next fields that point nowhere-such pointers are considered terminators denoting the end of the list and are typically populated with null values.

Before proceeding to the sample code, let's make a tiny change to the structure we've been using in this chapter and add the next and previous pointers. The structure should look like this:

struc strtabentry [s]

{

.length dw .pad - .string

.string db s, 0

.pad rb 30 - (.pad - .string)

.previous dd ? ; Pointer to the next node

.next dd ? ; Pointer to the previous node

.size = $ - .length

}

We will leave the make_strtab macro intact as we still need something to build a set of strtabentry structures; however, we will not consider it to be an array of structures any more. Also, we will add a variable (of type double word) to store the top pointer. Let's name it list_top.

Instead or writing a macro instruction that would link the four structures into a doubly linked list, we will write a procedure for adding new nodes to the list. The procedure requires two parameters--a pointer to the list_top variable and a pointer to the structure we want to add to the list. If we were writing in C, then the prototype of the corresponding function would be as follows:

void add_node(strtabentry** top, strtabentry* node);

However, since we are not writing in C, we will put down the following code:

add_node:

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

push eax ebx ecx

virtual at ebp + 8

.topPtr dd ?

.nodePtr dd ?

end virtual

virtual at ebx

.scx strtabentry ?

end virtual

virtual at ecx

.sbx strtabentry ?

end virtual

mov eax, [.topPtr] ; Load pointer to list_top

mov ebx, [.nodePtr] ; Load pointer to new structure

or dword [eax], 0 ; Check whether list_top == NULL

jz @f ; Simply store the structure pointer

; to list_top if true

mov ecx, [eax] ; Load ECX with pointer to current top

mov [.scx.next], ecx ; node->next = top

mov [.sbx.previous], ebx ; top->previous = node

@@:

mov [eax], ebx ; top = node

pop ecx ebx eax

leave

ret 8

Now, having the procedure ready, we will call it from our main procedure:

_start:

push strtabName + 40 ; Let the second structure be the first

push list_top ; in the list

call add_node

push strtabName + 120 ; Then we add fourth structure

push list_top

call add_node

push strtabName + 80 ; Then third

push list_top

call add_node

push strtabName ; And first

push list_top

call add_node

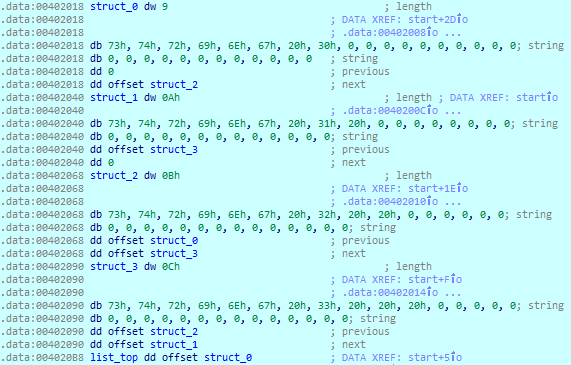

The first, second, third, and fourth refers to positions of structures in memory, not to positions of nodes in the doubly linked list. Thus, after the last line of the preceding code is executed, we have a doubly linked list of strtabentry structures (shown by their position in the linked list) {0, 2, 3, 1}. Let's take a look at the following screenshot for a demonstration of the result:

For the sake of convenience, the structures are named struct_0, struct_1, struct_2, and struct_3 in accordance with the order of their appearance in memory. The last line is the top pointer list_top. As we can see, it points to struct_0, which was the last we added to the list, and struct_0, in turn, only has a pointer to the next structure, while its previous pointer has a NULL value. The struct_0 structure's next pointer points to struct_2, struct_2 structure's next points to struct_3, and the previous pointers lead us back in the reverse order.

Obviously, linked lists (those with a single, either forward or backward), link are a bit simpler than doubly linked lists as we only have to take care of a single pointer member of a node. It may be a good idea to implement a separate structure that describes a linked list node (whether simple or doubly linked) and have a set of procedures for the creation/population of linked lists, search of a node, and removal of a node. The following structure would suffice:

; Structure for a simple linked list node

struc list_node32

{

.next dd ? ; Pointer to the next node

.data dd ? ; Pointer to data object, which

; may be anything. In case data fits

; in 32 bits, the .data member itself

; may be used for storing the data.

}

; Structure for a doubly linked list node

struc dllist_node32

{

.next dd ?

.previous dd ? ; Pointer to the previous node

.data dd ?

}

If, on the other hand, you are writing code for the long mode (64-bit), the only change you need to make is replacing dd (which stands for a 32-bit double word) with dq (which stands for a 64-bit quad word) in order to be able to store long mode pointers.

In addition to this, you may also want or need to implement a structure that will describe a linked list, as a whole, having all the required pointers, counters, and so on (in our example, it was the list_top variable; not quite a structure, but it did its job well enough). However, when it comes to an array of linked lists, it would be much more convenient to utilize an array of pointers to linked lists, as this would provide easier access to members of the array, thus making your code less error prone, simpler, and faster.