Prior to beginning with the obfuscation of the call instruction itself, we will define a utility macro called random:

; The %t below stands for the current

; timestamp (at the compile time)

random_seed = %t

; This macro sets 'r' to current random_seed

macro random r

{

random_seed = ((random_seed *\

214013 +\

2531011) shr 16) and 0xffffffff

r = random_seed

}

The random macro generates a pseudo-random integer and returns it in the parameter variable. We will need this tiny portion of randomization in order to add some diversity to our call implementation occurrences. The macro itself (let us call it f_call) makes use of the EAX register; therefore, we would either take care of preserving this register before the f_call invocation or only use this macro with procedures returning a value in the EAX register as, otherwise, the value of the register would be lost. Also, it is only suitable for direct calls due to the way it handles the parameter.

At last, we come to the macro itself. As the best way to understand the code is to look at the code, let's peer into the macro:

; This macro has a parameter - the label (address)

; of the procedure to call

macro f_call callee

{

; First we declare a few local labels

; We need them to be local as this macro may be

; used more than once in a procedure

local .reference_addr,\

.out,\

.ret_addr,\

.z,\

.call

; Now we need to calculate the reference address

; for all further address calculations

call .call

.call:

add dword[esp], .reference_addr - .call

; Now the address or the .reference_addr label

; is at [esp]

; Jump to the .reference_addr

ret

; Add some randomness

random .z

dd .z

; The ret instruction above returns to this address

.reference_addr:

; Calculate the address of the callee:

; We load the previously generated random bytes into

; the .z compile time variable

load .z dword from .reference_addr - 4

mov eax, [esp - 4] ; EAX now contains the address

; of the .reference_addr label

mov eax, [eax - 4] ; And now it contains the four

; random bytes

xor eax, callee xor .z ; EAX is set to the address of

; the callee

; We need to set up return address for the callee

; before we jump to it

sub esp, 4 ; This may be written as

; 'add esp, -4' for a bit of

; additional obfuscation

add dword[esp], .ret_addr - .reference_addr

; Now the value stored on stack is the address of

; the .ret_addr label

; At last - jump to the callee

jmp eax

; Add even more randomness

random .z

dd .z

random .z

dd .z

; When the callee returns, it falls to this address

.ret_addr:

; However, we want to obfuscate further execution

; flow, so we add the following code, which sets

; the value still present on stack (address of the

; .ret_addr) to the address of the .out label

sub dword[esp - 4], -(.out - .ret_addr)

sub esp, 4

ret

; The above two lines are, in fact, an equivalent

; of 'jmp dword[esp - 4]'

; Some more randomness

random .z

dd .z

.out:

}

As we may see, there are no complex computations involved in this particular obfuscation attempt and, even more, the code is still readable and understandable, but let's replace the line call fgets in our patch_section.asm file with f_call fgets, recompile, and re-apply the patch to the executable.

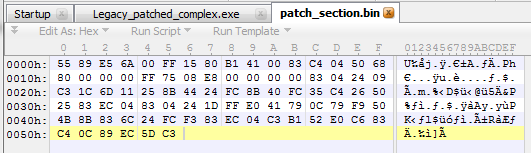

The new patch is significantly bigger--86 bytes instead of 35 bytes:

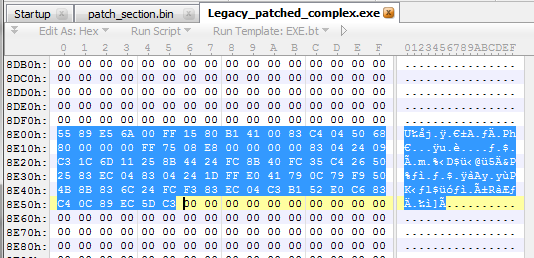

Copy these bytes and paste them into the Legacy.exe file at the 0x8e00 offset, as shown in the following screenshot:

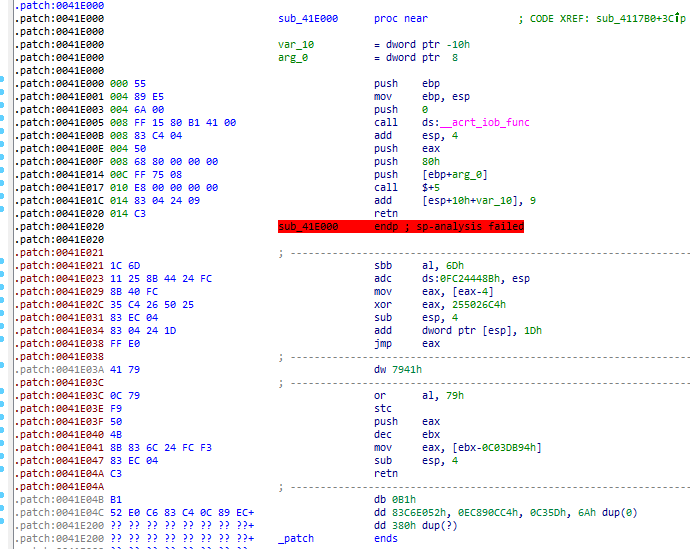

Running the executable, we will obtain the same result as we did in the previous chapter, so no visible difference at this stage. However, let's take a look at what the code looks like in the disassembler:

We can't say that the code is heavily obfuscated here, but it should give you an idea of what may be done with the aid of relatively simple macros used with the Flat Assembler. The preceding example may still be read with a tiny effort, but the application of a few more obfuscation tricks would render it literally unreadable and almost irreversible without a debugger.