The idea behind internationalization is to ensure that everything that gets output on the site can be translated into the enabled languages through a common mechanism--in this case, using the Interface Translation module. This refers to content, visible configuration values, and the strings and texts that come out of modules and themes. But there are many different ways this can happen, so let's see how in each of these cases we would ensure that our information can be translated.

A principle rule when writing Drupal modules or themes is to always use English as the code language. This is to ensure consistency and keep open the possibility that other developers will work on the same codebase, which may not speak a particular language. This is also the case for text used to be displayed in the UI. It should not be the responsibility of the code to output the translated text, but rather to always keep it consistent, that is, in English.

Of course, this is dependent on it being done right, in order to allow it to be translated via interface translation. There are multiple ways this can be ensured, depending on the circumstances.

The most common scenario we need to be aware of is when we have to print out to the user, in a PHP, string of text. Drupal 7 developers should already be familiar with the t() function through which these strings are run. This function still exists and should be used whenever we are not inside a class context:

return t('The quick brown fox');

However, when we are inside a class, we should check if any of the parents are using the StringTranslationTrait. If not, we should use it in our class and then we'll be able to do this instead:

return $this->t('The quick brown fox');

Even better still, we should inject the TranslationManager service into our class because the preceding mentioned trait makes use of it.

None of the examples given before should be new to us, as we've been using these throughout the code we've been writing in this book. But what actually happens behind the scenes?

The t() and StringTranslationTrait::t() functions both create and return an instance of TranslatableMarkup (essentially delegating to its constructor), which upon rendering (being cast to a string), will return the formatted and translated string. The responsibility of the actual translation is delegated to the TranslationManager service. This process has two parts. Static analyzers pick up on these text strings and add them to the database in the list of strings that need to be localized. These can then be translated by users via the user interface. Second, at runtime, the strings get formatted and the translated version is shown, depending on the current language context. Because of the first part, we should never do something like this:

return $this->t($my_text);

The reason is that static analyzers can no longer pick up on the strings that need to be translated. Moreover, if the text is coming from user input, it can lead to XSS attacks if not properly sanitized before.

That being said, we can still have dynamic, that is, formatted, text output using this method, and we've seen this in action as well:

$count = 5;

return $this->t('The quick brown fox jumped @count times', ['@count' => $count]);

In this case, we have a dynamic variable (which can be part of user input), which will be used to replace the placeholder @count from the text. Drupal takes care of sanitizing the variable before outputting the string to the user. Alternatively, we can also use the % prefix to define a placeholder we want Drupal to wrap with <em class="placeholder">. The cool thing is that, when performing translations, users can shift the placeholder in the sentence to accommodate language specificity.

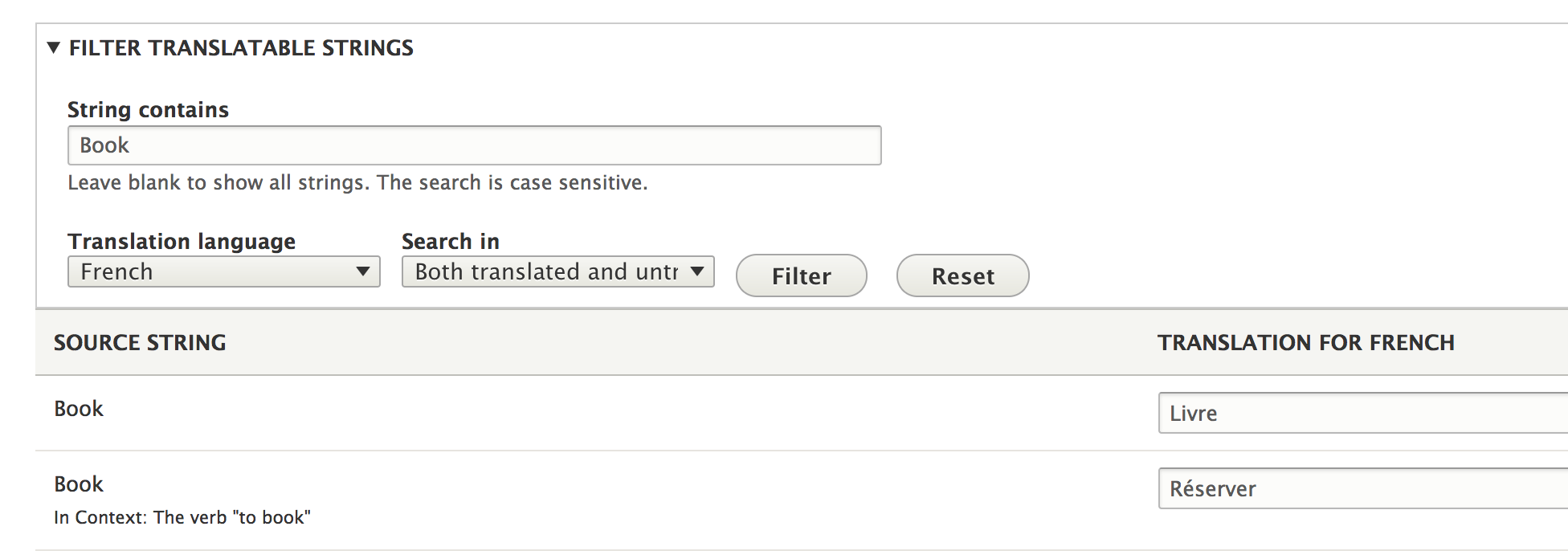

One of the intended consequences of the static analyzer picking out and storing the strings that need to be translated is that, by default, each individual string is only translated once. This is good in many cases but also poses some problems when the same English string has different meanings (which map to different translations in other languages). To counter this issue, we can specify a context to the string that needs to be translated so that we can identify which meaning we actually want to translate. This is where the third parameter of the t() function (and method) we saw in the previous paragraphs comes into play.

For example, let's consider the word Book, which is translated by default in its meaning as a noun. But we may have a submit button on a form that has the value Book, which clearly has a different meaning as a call to action. So in the latter case, we could do it like this:

t('Book', [], ['context' => 'The verb "to book"']);

Now in the interface translation, we will have both versions available.

Another helpful tip is that we can also account for plurals in the string translations. The StringTranslationTrait::formatPlural() helps with this by creating a PluralTranslatableMarkup object similar to the TranslatableMarkup, but with some extra parameters to account for differences when it comes to plurals. This comes in very handy in our preceding example with the brown fox jumping a number of times, because if the fox jumps only once, the resulting string would not be grammatically correct anymore. So instead, we can do the following:

$count = 5; return $this->formatPlural($count, 'The quick brown fox jumped 1 time', 'The quick brown fox jumped @count times')];

The first parameter is the actual count (the differentiator between singular and plural). The second and third parameters are the singular and plural versions respectively. You'll also notice that since we specified the count already, we don't have to specify it again in the arguments array. It's important to note that the placeholder name inside the string needs to be @count if we want the renderer to understand its purpose.

The string translation techniques we discussed so far also work in other places--not just in PHP code. For example, in JavaScript we would do something like this:

Drupal.t('The quick brown fox jumped @count times', {'@count': 5});

Drupal.formatPlural(5, 'The quick brown fox jumped 1 time', 'The quick brown fox jumped @count times');

So, based on this knowledge, I encourage you to go back and fix our incorrect use of the string output in JavaScript in the previous chapter.

In Twig, we'd have something like this (for simple translations):

{{ 'Hello World.'|trans }}

{{ 'Hello World.'|t }}

Both of the above lines do the same thing. To handle plurals (and placeholders), we can use the {% trans %} block:

{% set count = 5 %}

{% trans %}

The quick brown fox jumped 1 time.

{% plural count %}

The quick brown fox jumped {{ count }} times.

{% endtrans %}

Finally, the string context is also possible like so:

{% trans with {'context': 'The verb "to book"'} %}

Book

{% endtrans %}

In annotations, we have the @Translation() wrapper, as we've seen already a few times when creating plugins or defining entity types.

Finally, in YAML files, some of the strings are translatable by default (so we don't have to do anything):

- Module names and descriptions in .info.yml files

- The _title (together with the optional _title_context) key values under the defaults section of .routing.yml files

- The title (together with the optional title_context) key values in .links.action.yml, .links.task.yml and .links.contextual.yml files

Dates are also potentially problematic when it comes to localization, as different locales show dates differently. Luckily, Drupal provides the DateFormatter service, which handles this for us. For example:

\Drupal::service('date.formatter')->format(time(), 'medium');

The first parameter of this formatter is the UNIX timestamp of the date we want to format. The second parameter indicates the format to use (either one of the existing formats or custom). Drupal comes with a few predefined date formats, but site builders can define others as well as, which can be used here. However, if the format is custom, the third parameter is a a PHP date format string suitable for input to date(). The fourth parameter is a time zone identifier we want to format the date in, and the final parameter can be used to specify the language to localize to directly (regardless of the current language of the site).