The primary plugin type for creating a field is, as we discussed, the FieldType. It is responsible for defining the field structure, how it is stored in the database, and various other settings. Moreover, it also defines a default widget and formatter plugin that will be autoselected when we create the field in the UI. You see, a single field type can work with more than one widget and formatter. If more exist, the site builder can choose one when creating the field and adding it to an entity type bundle.

Otherwise, it will be the default; each field needs one because without a widget, users can't add data, and without a formatter, they can't see it. Also, as you'd expect, widgets and formatters can also work with more than one field type.

The field we will create in this section is for the license plate data, which, as we saw, needs two individual pieces of information--a code (such as the state code) and the number. License plates around the world are more complex than this, but I chose this example to keep things simple.

Our new FieldType plugin needs to go inside the Plugin/Field/FieldType namespace of a new module we will create called license_plate. Although not mandatory, the class name should end with the word Item. It's a pretty standard thing done in Drupal core, and we will follow suit. So, let's take a look at our LicensePlateItem plugin implementation and then talk about its code:

namespace Drupal\license_plate\Plugin\Field\FieldType;

use Drupal\Component\Utility\Random;

use Drupal\Core\Field\FieldDefinitionInterface;

use Drupal\Core\Field\FieldItemBase;

use Drupal\Core\Field\FieldStorageDefinitionInterface;

use Drupal\Core\Form\FormStateInterface;

use Drupal\Core\TypedData\DataDefinition;

/**

* Plugin implementation of the 'license_plate_type' field type.

*

* @FieldType(

* id = "license_plate",

* label = @Translation("License plate"),

* description = @Translation("Field for creating license plates"),

* default_widget = "default_license_plate_widget",

* default_formatter = "default_license_plate_formatter"

* )

*/

class LicensePlateItem extends FieldItemBase {}

I omitted the class contents, as we will be adding the methods one by one and discussing them individually. However, first, we have the plugin annotation, which is very important. We have the typical plugin metadata such as the ID, label, and description and also will indicate the plugin IDs for the widget and formatter that will be used by default with this field type. Make a note of those, because we will create them soon.

Speaking from experience, often, when creating a field type, you'll extend the class of an already existing field type plugin, such as a text field or an entity reference. This is because Drupal core already comes with a great set of available types, and, usually, all you need is either to make some tweaks to an existing one or maybe combine them or add an extra functionality.

This makes things easier, and you don't have to copy and paste code or come up with it again yourself. Naturally, though, at some point, you'll be extending from FieldItemBase because that is the base class all field types need to extend from.

In our example, however, we will extend straight from the FieldItemBase abstract class because we want our field to stand on its own. Also, it's not super practical to extend from any existing ones in this case. That is not to say, though, that it doesn't have commonalities with other field types, such as TextItem, for example.

Let's now take a look at the first method:

/**

* {@inheritdoc}

*/

public static function defaultStorageSettings() {

return [

'number_max_length' => 255,

'code_max_length' => 5,

] + parent::defaultStorageSettings();

}

The first thing we do in our class is override the defaultStorageSettings() method. The parent class method returns an empty array; however, it's still a good idea to include whatever it returns to our own array. If the parent method changes and returns something later on, we are a bit more robust.

The purpose of this method is two-fold--specify what storage settings this field has and set some defaults for them. Also, note that it is a static method, which means that we are not inside the plugin instance. However, what are storage settings, you may ask?

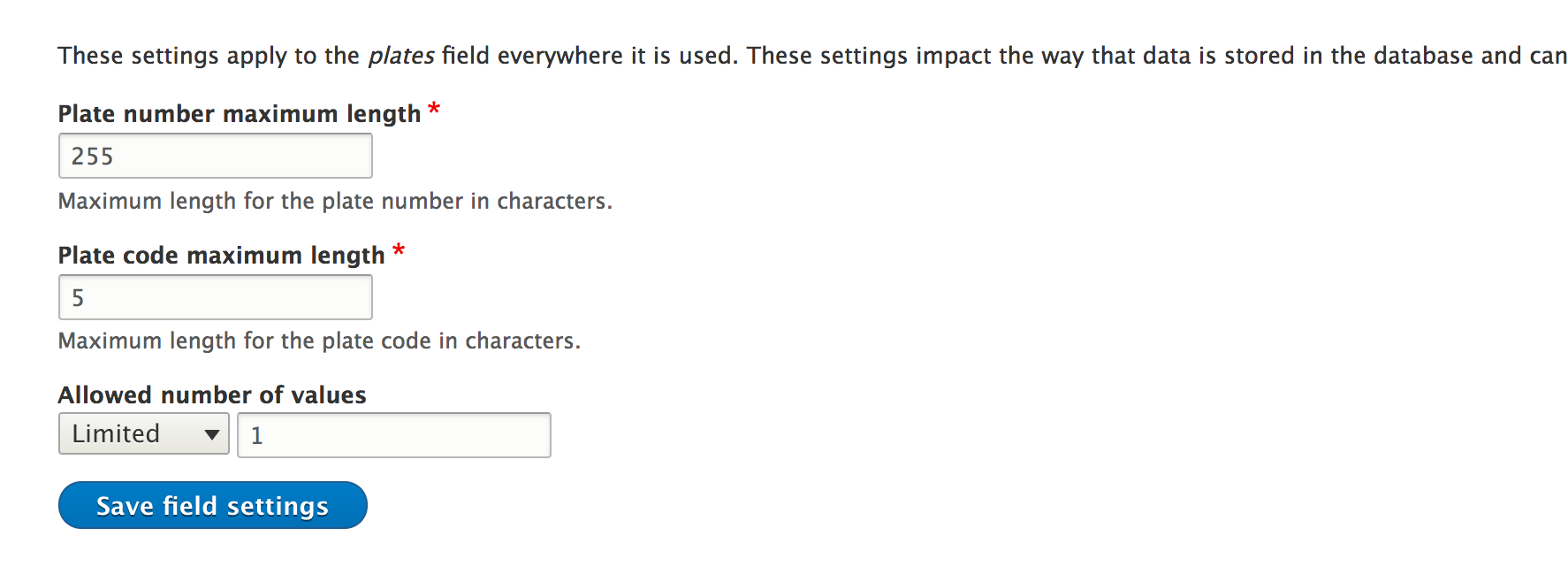

Storage settings are the configuration that applies to the field everywhere it's used. As you may know, a field can be added to multiple bundles of an entity type. In Drupal 7, you could reuse a field even across entity types, but this is no longer possible, so fields are now reusable only on the bundles of a single entity type. You'll need to create another field of that type if you need it on some other content entity type. So, the storage settings are those that apply to this field across each bundle it is attached to.

They usually deal with things related to the schema--how the database table columns are constructed for this field but they also deal with a lot of other things. Also, even more important to know is that once there is data in the field tables, they cannot be changed. It makes sense, as you cannot easily change database tables when there is data in them. This restriction is something we enforce, as we will see in a bit.

In our example, we only have two storage settings--number_max_length and code_max_length. These will be used when defining the schema for the two-table columns, where the license plate data will be stored (as the maximum length that can be stored in those table fields). By default, we will go with the ever-so-used 255 maximum length on the number column and 5 for the code column, but these are just defaults. The user will be able to change them when creating the field or when editing, as long as there is no data yet.

Next, we can write our storage settings form, which allows users to provide the actual settings when creating a field:

/**

* {@inheritdoc}

*/

public function storageSettingsForm(array &$form, FormStateInterface $form_state, $has_data) {

$elements = [];

$elements['number_max_length'] = [

'#type' => 'number',

'#title' => t('Plate number maximum length'),

'#default_value' => $this->getSetting('number_max_length'),

'#required' => TRUE,

'#description' => t('Maximum length for the plate number in characters.'),

'#min' => 1,

'#disabled' => $has_data,

];

$elements['code_max_length'] = [

'#type' => 'number',

'#title' => t('Plate code maximum length'),

'#default_value' => $this->getSetting('code_max_length'),

'#required' => TRUE,

'#description' => t('Maximum length for the plate code in characters.'),

'#min' => 1,

'#disabled' => $has_data,

];

return $elements + parent::storageSettingsForm($form, $form_state, $has_data);

}

The preceding method is called by the main field configuration form, and we need to return an array of form elements from it that can be used to set values to the storage settings we defined earlier. We have access to the main $form and $form_state of the form where this is embedded, as well as a handy Boolean $has_data, which tells us whether there is already any data in this field. We use this to disable the elements we don't want to be changed if there is data in the field (in our case, both).

So, basically, our form consists of two number form elements (both required), whose values default to the lengths we specified earlier. The number form element also comes with #min and #max properties, which we can use to restrict the number to a range. Also, we obviously want our minimum lengths to be a positive number, that is, above 1. This method is relatively straightforward to understand if you get the basics of the Form API, which you should by now.

Finally, for our storage handling, we will need to implement the schema method and define our table columns:

/**

* {@inheritdoc}

*/

public static function schema(FieldStorageDefinitionInterface $field_definition) {

$schema = [

'columns' => [

'number' => [

'type' => 'varchar',

'length' => (int) $field_definition->getSetting('number_max_length'),

],

'code' => [

'type' => 'varchar',

'length' => (int) $field_definition->getSetting('code_max_length'),

],

],

];

return $schema;

}

This is another static method, but one that receives the current fields's FieldStorageDefinitionInterface instance. From there, we can access the settings the user has saved when creating the field, and based on those, we define our schema. If you've been paying attention in the preceding chapter, when we discussed hook_schema(), this should already be very clear to you. What we need to return is an array of column definitions keyed by their name. So, we define two columns of the varchar type with the maximum lengths the user has configured--no rocket science involved. Of course, we could have had more storage settings and had this schema definition even more configurable if we'd wanted to.

With these three methods, our storage handling is complete; however, our field type is not quite. We still have a couple more things to take care of.

Apart from storage, as we discussed, fields also deal with data representation at the code level with TypedData structures. So, our field type needs to define its individual properties for which we create storage. For this, we have two main methods--first, to actually define the properties, and then, to set some potential constraints on them:

/**

* {@inheritdoc}

*/

public static function propertyDefinitions(FieldStorageDefinitionInterface $field_definition) {

$properties['number'] = DataDefinition::create('string')

->setLabel(t('Plate number'));

$properties['code'] = DataDefinition::create('string')

->setLabel(t('Plate code'));

return $properties;

}

The preceding code will look very familiar to the one in Chapter 6, Data Modeling and Storage, when we talked about TypedData. Again, this is a static method, which needs to return the DataDefinitionInterface instance for the individual properties. We choose to call them number and code, respectively, and set some sensible labels--nothing too complicated.

The preceding code is actually enough to define the properties, but if you remember, our storage has some maximum lengths in places-meaning that the table columns are only so long. So, if the data that gets into our field is longer, the database engine will throw a fit in a not so graceful way. In other words, it will throw a big exception, and we can't have that. So, there are two things we can do to prevent that--put the same maximum length on the form widget to prevent users from inputting more than they should and add a constraint on our data definitions. The second one is more important because it ensures that the data is valid in any case, whereas the first one only deals with forms. However, since Drupal 8 is so much more API oriented, if we create an entity programmatically and set its field values, we bypass forms completely. However, not to worry; we will also take care of the form, so our users can have a nicer experience and are aware of the maximum size of the values they need to input.

So, let's add the following constraints:

/**

* {@inheritdoc}

*/

public function getConstraints() {

$constraints = parent::getConstraints();

$constraint_manager = \Drupal::typedDataManager()->getValidationConstraintManager();

$number_max_length = $this->getSetting('number_max_length');

$code_max_length = $this->getSetting('code_max_length');

$constraints[] = $constraint_manager->create('ComplexData', [

'number' => [

'Length' => [

'max' => $number_max_length,

'maxMessage' => t('%name: may not be longer than @max characters.', [

'%name' => $this->getFieldDefinition()->getLabel() . ' (number)',

'@max' => $number_max_length

]),

],

],

'code' => [

'Length' => [

'max' => $code_max_length,

'maxMessage' => t('%name: may not be longer than @max characters.', [

'%name' => $this->getFieldDefinition()->getLabel() . ' (code)',

'@max' => $code_max_length

]),

],

],

]);

return $constraints;

}

Since our field class actually implements the TypedDataInterface, it also has to implement the getConstraints() method (which the TypedData parent already starts up). However, we can override it and provide our own constraints based on our field values.

We are taking a slightly different approach here of adding constraints than what we've seen in Chapter 6, Data Modeling and Storage. Instead of adding them straight to the data definitions, we will create them manually using the validation constraint manager (which is the plugin manager of the Constraint plugin type we saw in Chapter 6, Data Modeling and Storage). This is because fields use a specific ComplexDataConstraint plugin, which can combine the constraints of multiple properties (data definitions). Do note that even if we had only one property in this field, we'd still be using this constraint plugin.

The data needed to create this constraint plugin is a multidimensional array keyed by the property name, which contains constraint definitions (as we saw in Chapter 6, Data Modeling and Storage) for each of them. So, we have a Length constraint for both properties, whose options denote a maximum length and a corresponding message if exceeded. If we wanted, we could have had a minimum length in the same way also--min and minMessage. As for the actual length, we will use the values chosen by the user when creating the field (the storage maximum). Now, regardless of the form widget, our field will not validate unless the maximum lengths are respected.

It's time to finish this class with the following last two methods:

/**

* {@inheritdoc}

*/

public static function generateSampleValue(FieldDefinitionInterface $field_definition) {

$random = new Random();

$values['number'] = $random->word(mt_rand(1, $field_definition->getSetting('number_max_length')));

$values['code'] = $random->word(mt_rand(1, $field_definition->getSetting('code_max_length')));

return $values;

}

/**

* {@inheritdoc}

*/

public function isEmpty() {

// We consider the field empty if either of the properties is left empty.

$number = $this->get('number')->getValue();

$code = $this->get('code')->getValue();

return $number === NULL || $number === '' || $code === NULL || $code === '';

}

With generateSampleValue(), we create some random words that fit within our field--that's it. This can be used when profiling or site building for populating the field with values. Arguably, this is not going to be your top priority, but it is good to know.

Finally, we have the isEmpty() method, which is used to determine whether the field has values or not. It may seem pretty obvious, but it's an important method, especially for us, and you can probably deduce from the implementation why. When creating the field in the UI, the user can specify whether it's required or not. However, typically, that applies (or should apply) to the entire set of values within the field. Also, if the field is not required, and the user only inputs a license plate code without a number, what kind of useful value is that to save? So, we want to make sure that both of them have something before even considering this field as having a value (not being empty), and that is what we are checking in this method.

Now that we are finished with the actual plugin class, there is one last thing that we need to take care of, something that we tend to forget, myself included--configuration schema. Our new field is a configurable field whose settings are stored--guess where?--in configuration. Also, as you remember, all configuration needs to be defined by a schema. Drupal already takes care of those storage settings that come from the parent. However, we need to include ours. So, let's create the typical license_plate.schema.yml (inside config/schema), where we will put the definitions for the field type and any others that we will need in this module.

Then, we can have the following code inside it:

field.storage_settings.license_plate_type:

type: mapping

label: 'License plate storage settings'

mapping:

number_max_length:

type: integer

label: 'Max length for the number'

code_max_length:

type: integer

label: 'Max length for the code'

The actual definition will already be familiar, so the only thing that is interesting to explain is its actual naming. The pattern is field.storage_settings.[field_type_plugin_id]. Drupal will dynamically read the schema and apply it to the settings of the actual FieldStorageConfig entity being exported.

That's it for our FieldType plugin. When creating a new field of this type, we have the two storage settings we can configure (which will be disabled when editing if there is actual field data already in the database):

Unless we work only programmatically or via an API to manage the entities that use this field, it won't really be useful, as there are no widgets or formatters it can work with. So, we will need to create those as well.