Earlier I warned about the entity access controls we've been talking about not being taken into account during queries (either written by us or Views). This is something to pay attention to. For example, if you make a listing of entities, you will need to ensure that users have access to these entities before printing the results out. The problem here occurs when using the built-in paging capabilities of either the entity query or database API. That's because the pager information will reflect all the query results. So, if you don't print the inaccessible entities, there will be a mismatch between the pager information and visible results.

If you remember, in Chapter 6, Data Modeling and Storage, I mentioned that when it comes to nodes, the entity query takes access into account. If you want to avoid that, you should use the accessCheck(FALSE) method on the query builder. Let's elaborate a bit on this.

First, this method is available on all entity types, not just nodes. However, it is really useful only for those which have defined a status field to denote that entities can be either published or unpublished (or/off, enabled/disabled however you prefer). The query will simply add a condition to that field and only return the ones with the status that equals 1. Also, passing FALSE to this method simply removes that condition.

Second, the Node entity type has a much more powerful built-in access system called access grants. These have been there from previous versions of Drupal, and this is why we have it available in D8 as well. Unfortunately, it is not there for other entity types. However, if you really need it, you could technically write it yourself now that you know how the entity access system works in general, and can look into how the node access grants are built. But what is this system about?

The node access grants system is a granular way by which we can control access to any of the operations on a node. This is done using a combination of realms and grants. When a node is saved, we have the opportunity to create access records for that node that contain the following information:

- realm (string): A category for our access records. Typically, this is used to denote specific functionality under which the access control happens.

- gid (grant ID) (int): The ID of the grant by which we can verify the user trying to access the node. Typically, this will map to either a role or a custom-defined "group" that users belong to. For example, a manager user type (from the earlier example) can map to the grant ID 1. You'll understand this in a moment.

- grant_view, grant_update, grant_delete (int): Boolean indicating whether this access record is for this operation.

- langcode (string): The language of the node this access record should apply to.

Then, we can return grant records for a given user when they try to access the node. For a given user, we can return multiple grants as part of multiple realms.

The node access records get stored inside the node_access table, and it's a good idea to keep checking that table while you are developing and preparing your access records. By default, if there are no modules that provide access records, there will be only one row in that table referencing the Node ID "0" and the realm all. This means that basically the node access grants system is not used, and all nodes are accessible for viewing in all realms. That is to say, default access rules apply. Once a module creates records, as we will see, this row is deleted.

To better understand how this system works, let's see a practical code example. For this, we'll get back to our User Types module and create some node access restrictions based on these user types. We'll start with an easy example and then expand on it to make it more complex (and more useful).

To begin with, we want to make sure that Article nodes are only viewable by users of all three types (so there are still some restrictions, as users need to have a type). Page nodes, on the other hand, are restricted to managers and board members. So let's get it done.

All the work we do now takes place inside the .module file of the module. First, let's create a rudimentary mapping function to which we can provide a user type string (as we've seen before) and which returns a corresponding grant ID. We will then use this consistently to get the grant ID of a given user type:

/**

* Returns the access grant ID for a given user type.

*

* @param $type

*

* @return int

*/

function user_types_grant_mapping($type) {

$map = [

'employee' => 1,

'manager' => 2,

'board_member' => 3

];

if (!isset($map[$type])) {

throw new InvalidArgumentException('Wrong user type provided');

}

return $map[$type];

}

It's nothing too complicated. We have our three user types that map to simple integers. Also, we throw an exception if a wrong user type is passed--now comes the fun part.

Working with node access grants restrictions involves the implementation of two hooks--one for creating the access records of the nodes, and the other to provide the grants of the current user. Let's first implement hook_node_access_records():

/**

* Implements hook_node_access_records().

*/

function user_types_node_access_records(\Drupal\node\NodeInterface $node) {

$bundles = ['article', 'page'];

if (!in_array($node->bundle(), $bundles)) {

return [];

}

$map = [

'article' => [

'employee',

'manager',

'board_member',

],

'page' => [

'manager',

'board_member'

]

];

$user_types = $map[$node->bundle()];

$grants = [];

foreach ($user_types as $user_type) {

$grants[] = [

'realm' => 'user_type',

'gid' => user_types_grant_mapping($user_type),

'grant_view' => 1,

'grant_update' => 0,

'grant_delete' => 0,

];

}

return $grants;

}

This hook is invoked whenever a node is being saved, and it needs to return an array of access records for that node. As expected, the parameter is the node entity.

The first thing we do is simply return an empty array if the node is not one of the ones we are interested in. If we return no access records, this node will be given one single record for the realm all with the grant ID of 1 for the view operation. This means that it is accessible in accordance to the default node access rules.

Then, we will create a simple map of the user types we want viewing our node bundles. Also, for each user type that corresponds to the current bundle, we create an access record for the user_type realm with the grant ID that maps to that user type, and with permission to view this node.

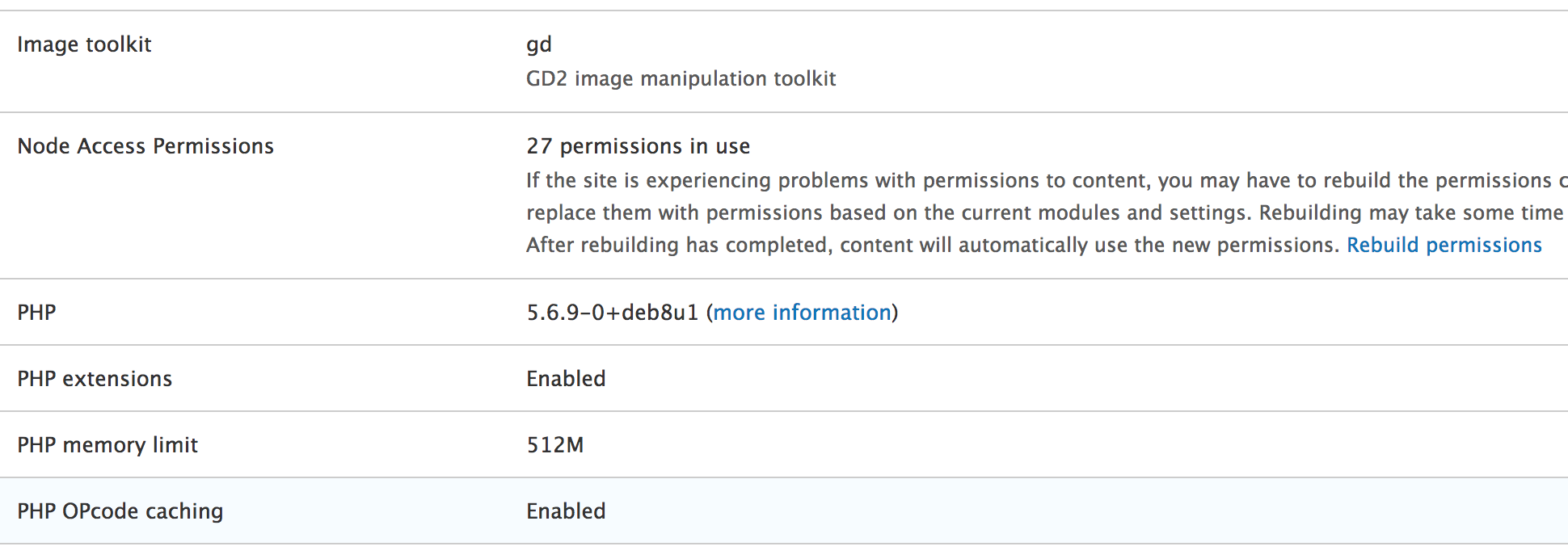

There are two ways we can trigger this hook and persist the access records. We can edit and save a node, which will create the records for that node, or we can rebuild the permissions that will do so for all the nodes on the site. The link to do so can be found on the status report page:

It's a good idea to rebuild the permissions while developing to make sure that your changes get applied to all the nodes. Once we do this, our nodes now become inaccessible to basically anyone (except the super user with the ID of 1). That's because we now need to specify the grants a given user should have by implementing hook_node_grants():

/**

* Implements hook_node_grants().

*/

function user_types_node_grants(\Drupal\Core\Session\AccountInterface $account, $op) {

if ($account->isAnonymous()) {

return [];

}

if ($op !== 'view') {

return [];

}

$user = \Drupal::entityTypeManager()->getStorage('user')->load($account->id());

$user_type = $user->get('field_user_type')->value;

if (!$user_type) {

return [];

}

try {

$gid = user_types_grant_mapping($user_type);

}

catch (InvalidArgumentException $e) {

return [];

}

return ['user_type' => [$gid]];

}

This hook is invoked by the node access system every time access is being checked on a given node (for a given operation). Moreover, it is also invoked when running entity queries against the node entity type and the access check has not been disabled. Finally, it is also invoked in database API queries when the node_access tag is used. Remember the query alters based on tags that we talked about in Chapter 8, The Database API?

As an argument, it receives the user account for which access needs to be checked--the grants that it has within the node access grants system of the given operation. So, what we do here is start by returning an empty array (no grants) if the user is anonymous or the operation they are attempting to do is not view--you have not been granted access. The same thing happens if the user entity does not have any value in the field_user_type field. If they do, however, we get the corresponding grant ID and return an array of access grants keyed by the realm. For each realm, we can include more than one grant ID. In this case, though, it is only once since the user can only be of one type. We can also return multiple realms if needed, and, of course, other modules may do so as well, the results being centralized and used in the access logic.

With this in place, all our page nodes are now available for viewing only to board member and manager users, whereas articles are available for viewing to employees as well. If users don't have any type, they don't have access. The great thing is that these restrictions are now being taken into account also when running queries. So, we can automatically exclude from query results the nodes to which users don't have access. This works with Views as well.

Let's now enhance this solution with the following changes:

- Unpublished article nodes are only available to managers and board members

- Managers also have access to update and delete articles and pages

The first one is easy. After we define our internal map inside user_types_node_access_records(), we can unset the employee from the array in case the node is unpublished:

if (!$node->isPublished()) {

unset($map['article'][0]);

}

This was a very simple example, but one meant to draw your attention to an important but often forgotten point. If you create access records for a node, you will need to account for the node status yourself. This means that if you grant access to someone to view a node, they will have access to view that node, regardless of the status (publishing state). Also, more often than not, this is not something you want. So, just make sure that you consider this point when implementing access grants.

Now, let's see how we can alter our logic to allow managers to update and delete nodes (both articles and pages). This is how user_types_node_access_records() looks like now:

$bundles = ['article', 'page'];

if (!in_array($node->bundle(), $bundles)) {

return [];

}

$view_map = [

'article' => [

'employee',

'manager',

'board_member',

],

'page' => [

'manager',

'board_member'

]

];

if (!$node->isPublished()) {

unset($view_map['article'][0]);

}

$manage_map = [

'article' => [

'manager',

],

'page' => [

'manager',

]

];

$user_types = $view_map[$node->bundle()];

$manage_user_types = $manage_map[$node->bundle()];

$grants = [];

foreach ($user_types as $user_type) {

$grants[] = [

'realm' => 'user_type',

'gid' => user_types_grant_mapping($user_type),

'grant_view' => 1,

'grant_update' => in_array($user_type, $manage_user_types) ? 1 : 0,

'grant_delete' => in_array($user_type, $manage_user_types) ? 1 : 0,

];

}

return $grants;

What we are doing different is, first, we rename the $map variable to $view_map in order to reflect the actual grant associations. Then, we create a $manage_map to hold the user types that can edit and delete the nodes. Based on this map, we can then set the grant_update and grant_delete values to 1 for the user types that are allowed. Otherwise, they stay as they were.

All we need to do now is go back to the hook_node_grants() implementation and remove the following:

if ($op !== 'view') {

return [];

}

We are now interested in all operations, so users should be provided all the possible grants. After rebuilding the permissions, manager user types will be able to update and delete articles and pages, while the other user types won't have these permissions. This does have many implications for queries because those use the view operation.

Before closing the topic on the node access grants, you should also know that there is an alter hook available that can be used to modify the access records created by other modules--hook_node_access_records_alter(). This is invoked after all the modules provide their records for a given node, and you can use it to alter whatever they provided before being stored.

The access grants system, as mentioned, is limited to the node entity type. It has been there from previous versions of Drupal, and it didn't quite make it to become standard across the entity system. There is talk, however, of doing this, but it's quite incipient.

To better understand how it works under the hood in case you want to write your own such system, I encourage you to explore the NodeAccessControlHandler. You'll note that its checkAccess() method delegates to the NodeGrantDatabaseStorage service responsible for invoking the grant hooks we've seen before. Moreover, you can also check out the node_query_node_access_alter implementation of hook_query_QUERY_TAG_alter() in which the Node module uses the same grant service to alter the query in order to take into account the access records. It's not the easiest system to dissect, especially if you are a beginner, but well worth going through and to learn more.