Chapter 13. Time Series Clustering

So far in this book, we have worked mostly with cross-sectional data, in which we have observations for entities at a single point in time. This includes the credit card dataset with transactions that happened over two days and the MNIST dataset with images of digits. For these datasets, we applied unsupervised learning to learn the underlying structure in the data and to group similar transactions and images together without using any labels whatsoever.

Unsupervised learning is also very valuable for work with time series data, in which we have observations for a single entity at different time intervals. We need to develop a solution that can learn the underlying structure of data across time, not just for a particular moment in time. If we develop such a solution, we can identify similar time series patterns and group them together.

This is very impactful in fields such as finance, medicine, robotics, astronomy, biology, metereology, etc. since professionals in these fields spend a lot of time analyzing data to classify current events based on how similar they are to past events. By grouping current events together with similar past events, these professionals are able to more confidently decide on the right course of action to take.

In this chapter, we will work on clustering time series data based on pattern similarity. Clustering time series data is a purely unsupervised approach and does not require annotation of data for training, although annotated data is necessary for validating the results as with all other unsupervised learning experiments.

Note

There is a third group of data that combines cross-sectional and time-series data. This is known as panel or longitudinal data.

ECG Data

To make the time series clustering problem more tangible, let’s introduce a specific real-world problem. Imagine if we were working in healthcare and had to analyze electrocardiogram (EKG/ECG) readings. ECG machines record the electrical activity of the heart over a period of time using electrodes placed over the skin. The ECG measures activity over approximately 10 secords, and the recorded metrics help detect any cardiac problems.

Most ECG readings record normal heartbeat activity, but the abnormal readings are the ones healthcare professionals must identify to react preemptively before any adverse cardiac event - such as cardiac arrest - occurs. The ECG produces a line graph with peaks and valleys so the task of classifying a reading as normal or abnormal is a straightforward pattern recognition task, well suited for machine learning.

Real-world ECG readings are not so cleanly displayed, making classification of the images into these various buckets difficult and error-prone.

For example, variations in the amplitude of the waves (the height of the center line to the peak or trough), the period (the distance from one peak to the next), the phase shift (horizontal shifting), and the vertical shift are challenges for any machine-driven classification system.

Approach to Time Series Clustering

Any approach to time series clustering will require us to handle these types of distortions. As you may recall, clustering relies on distance measures to determine how close in space data is to other data so that similar data can be grouped together into distinct and homogenous clusters.

Clustering time series data works similarly, but we need a distance measure that is scale- and shift-invariant so that similar time series data is grouped together regardless of trivial differences in amplitude, period, phase shift, and vertical shift.

k-Shape

One of the state-of-the-art approaches to time series clustering that meets this criteria is k-Shape, which was first introduced at ACM SIGMOD in 2015 by John Paparrizos and Luis Gravano.1

k-Shape uses a distance measure that is invariant to scaling and shifting to preserve the shapes of time-series sequencies while comparing them. Specifically, k-Shape uses a normalized version of cross-correlation to compute cluster centroids and then, in every iteration, updates the assignment of time series to these clusters.

In addition to being invariant to scaling and shifting, k-Shape is domain-independent and scalable, requiring minimal parameter tuning. Its iterative refinement procedures scales linearly in the number of sequences. These characteristics have led it to become one of the most powerful time series clustering algorithms available today.

By this point, it should be clear that k-Shape operates similarly to k-means - both algorithms use an iterative approach to assign data to groups based on the distance between the data and the centroid of the nearest group. The critical difference is in how k-Shape calculates distances - it uses shaped-based distance that relies on cross-correlations.

Time Series Clustering using k-Shape on ECG Five Days

Let’s build a time series clustering model using k-Shape.

In this chapter, we will rely on data from the UCR time-series collection. Because the file size exceeds one hundred megabytes, the file is not accessible on GitHub. You will need to download the files directly from the UCR Time Series website.

This is the largest public collection of class-labeled time-series datasets - 85 in total. These datasets are from multiple domains, so we can test how well our solution does across domains. Each time series belongs to only one class, so we also have labels to validate the results of our time series clustering.

Data Preparation

Let’s begin by loading the necessary libraries.

'''Main'''importnumpyasnpimportpandasaspdimportos,time,reimportpickle,gzip,datetimefromosimportlistdir,walkfromos.pathimportisfile,join'''Data Viz'''importmatplotlib.pyplotaspltimportseabornassnscolor=sns.color_palette()importmatplotlibasmplfrommpl_toolkits.axes_grid1importGrid%matplotlibinline'''Data Prep and Model Evaluation'''fromsklearnimportpreprocessingasppfromsklearn.model_selectionimporttrain_test_splitfromsklearn.model_selectionimportStratifiedKFoldfromsklearn.metricsimportlog_loss,accuracy_scorefromsklearn.metricsimportprecision_recall_curve,average_precision_scorefromsklearn.metricsimportroc_curve,auc,roc_auc_score,mean_squared_errorfromkeras.utilsimportto_categoricalfromsklearn.metricsimportadjusted_rand_scoreimportrandom'''Algos'''fromkshape.coreimportkshape,zscoreimporttslearnfromtslearn.utilsimportto_time_series_datasetfromtslearn.clusteringimportKShape,TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariancefromtslearn.clusteringimportTimeSeriesKMeansimporthdbscan'''TensorFlow and Keras'''importtensorflowastfimportkerasfromkerasimportbackendasKfromkeras.modelsimportSequential,Modelfromkeras.layersimportActivation,Dense,Dropout,Flatten,Conv2D,MaxPool2Dfromkeras.layersimportLeakyReLU,Reshape,UpSampling2D,Conv2DTransposefromkeras.layersimportBatchNormalization,Input,Lambdafromkeras.layersimportEmbedding,Flatten,dotfromkerasimportregularizersfromkeras.lossesimportmse,binary_crossentropyfromIPython.displayimportSVGfromkeras.utils.vis_utilsimportmodel_to_dotfromkeras.optimizersimportAdam,RMSpropfromtensorflow.examples.tutorials.mnistimportinput_data

We will use the tslearn package to access the python-based k-Shape algorithm. Tslearn has a similar framework to Scikit-learn but is geared towards work with time series data.

Next, let’s load the training and test data from the ECGFiveDays dataset, which was downloaded from the UCR Time Series archive. The first column in this matrix has the class labels, while the rest of the columns are the values of the time series data.

We will store the data as X_train, y_train, X_test, and y_test.

# Load the datasetscurrent_path=os.getcwd()file='\\datasets\\ucr_time_series_data\\'data_train=np.loadtxt(current_path+file+"ECGFiveDays/ECGFiveDays_TRAIN",delimiter=",")X_train=to_time_series_dataset(data_train[:,1:])y_train=data_train[:,0].astype(np.int)data_test=np.loadtxt(current_path+file+"ECGFiveDays/ECGFiveDays_TEST",delimiter=",")X_test=to_time_series_dataset(data_test[:,1:])y_test=data_test[:,0].astype(np.int)

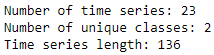

Figure 13-1 shows the number of time series, the number of unique classes, and the length of each time series.

# Basic summary statistics("Number of time series:",len(data_train))("Number of unique classes:",len(np.unique(data_train[:,0])))("Time series length:",len(data_train[0,1:]))

Figure 13-1. ECG five days summary

There are 23 time series, 2 unique classes, and each time series has a length of 136.

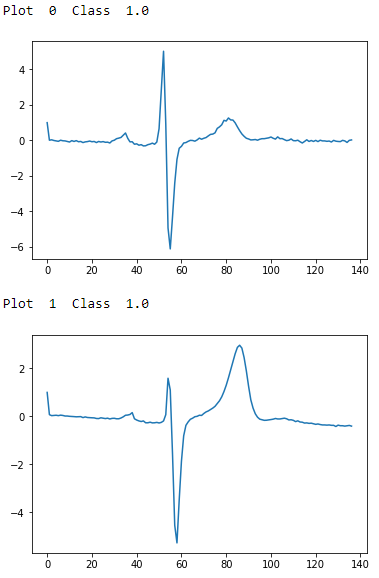

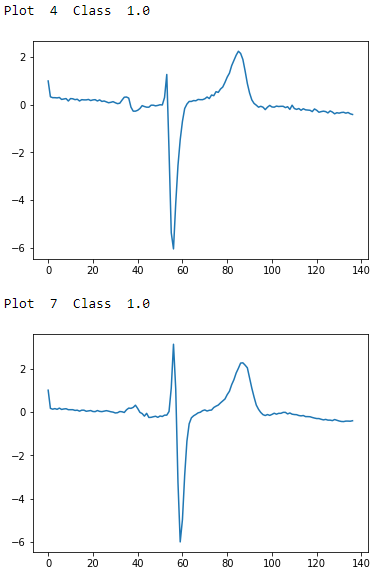

Figure 13-2 shows a few examples of each class; now we know what these ECG readings look like.

# Examples of Class 1.0foriinrange(0,10):ifdata_train[i,0]==1.0:("Plot ",i," Class ",data_train[i,0])plt.plot(data_train[i])plt.show()

Figure 13-2. ECG five days class 1.0 - first two examples

Figure 13-3. ECG five days class 1.0 - second two examples

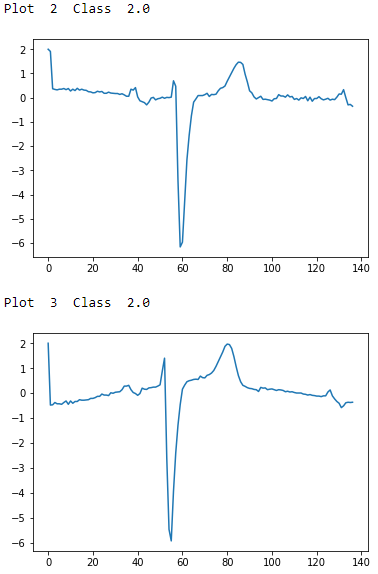

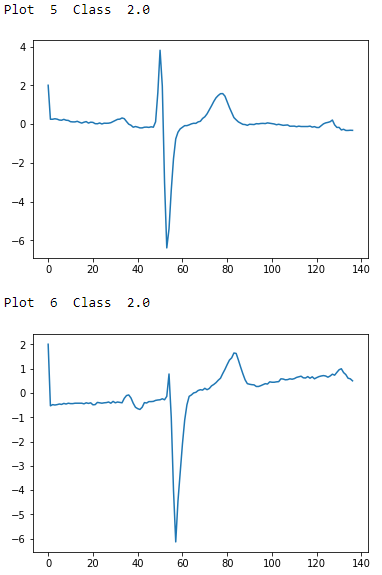

# Examples of Class 2.0foriinrange(0,10):ifdata_train[i,0]==2.0:("Plot ",i," Class ",data_train[i,0])plt.plot(data_train[i])plt.show()

Figure 13-4. ECG five days class 2.0 - first two examples

Figure 13-5. ECG five days class 2.0 - second two examples

To the naked, untrained eye, the examples from class 1.0 and class 2.0 seem indistinguisable, but these observations have been annotated by domain experts. The plots are noisy with distortions of the variety described earlier. There are differences in amplitude, period, phase shift, and vertical shift that make classification a challenge.

Let’s prepare the data for the k-Shape algorithm. We will normalize the data to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one.

# Prepare the data - ScaleX_train=TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariance(mu=0.,std=1.).fit_transform(X_train)X_test=TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariance(mu=0.,std=1.).fit_transform(X_test)

Training and Evaluation

Next, we will call the k-Shape algorithm and set the number of clusters as 2, the max iterations to perform as one hundred, and the number of rounds of training as one hundred.2

# Train using k-Shapeks=KShape(n_clusters=2,max_iter=100,n_init=100,verbose=0)ks.fit(X_train)

To measure the goodness of the time series clustering, we will use the adjusted Rand index, a measure of the similarity between two data clusterings adjusted for the chance grouping of elements. This is related to the accuracy measure.3

Intuitively, the Rand index measures the number of agreements in cluster assignments between the predicted clusterings and the true clusterings. If the model has an adjusted Rand index with a value close to 0.0, it is purely randomly assigning clusters; if the model has an adjusted Rand index with a value close to 1.0, the predicted clusterings match the true clusterings exactly.

We will use the Scikit-learn implementation of the adjusted Rand index, called the adjusted_rand_score.

Let’s generate clustering predictions and then calculate the adjusted Rand index.

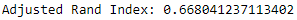

# Make predictions and calculate adjusted Rand indexpreds=ks.predict(X_train)ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_train[:,0],preds)("Adjusted Rand Index:",ars)

Based on this run, the adjusted Rand index is 0.668 (see Figure 13-6). If you perform this training and prediction several times, you will notice the adjusted Rand index will vary a bit but remains well above 0.0 at all times.

Figure 13-6. ECG five days adjusted rand index on train set

Let’s predict on the test set and calculate the adjusted Rand index for it.

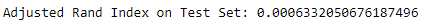

# Make predictions on test set and calculate adjusted Rand indexpreds_test=ks.predict(X_test)ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_test[:,0],preds_test)("Adjusted Rand Index on Test Set:",ars)

The adjusted Rand index is considerably lower on the test set, barely above 0 (see Figure 13-7). The cluster predictions are nearly chance assignments - the time series are being grouped based on similarity with little success.

Figure 13-7. ECG five days adjusted rand index on test set

If we had a much larger training set to train our k-Shape-based time series clustering model, we would expectbetter performance on the test set.

Time Series Clustering Using k-Shape on ECG 5000

Instead of the ECGFiveDays dataset, which has only 23 observations in the training set and 861 in the test set, let’s use a much larger dataset of ECG readings.

The ECG5000 dataset - also available on the UCR Time Series archive - has five thousand ECG readings (i.e., time series) in total across the train and test sets.

Data Preparation

We will load in the datasets and make our own train and test split, with 80% of the five thousand readings in the custom train set and the remaining 20% in the custom test set. With this much larger training set, we should be able to develop a time series clustering model that has much better performance, both on the train set and, most importantly, on the test set.

# Load the datasetscurrent_path=os.getcwd()file='\\datasets\\ucr_time_series_data\\'data_train=np.loadtxt(current_path+file+"ECG5000/ECG5000_TRAIN",delimiter=",")data_test=np.loadtxt(current_path+file+"ECG5000/ECG5000_TEST",delimiter=",")data_joined=np.concatenate((data_train,data_test),axis=0)data_train,data_test=train_test_split(data_joined,test_size=0.20,random_state=2019)X_train=to_time_series_dataset(data_train[:,1:])y_train=data_train[:,0].astype(np.int)X_test=to_time_series_dataset(data_test[:,1:])y_test=data_test[:,0].astype(np.int)

Let’s explore this dataset.

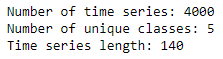

# Summary statistics("Number of time series:",len(data_train))("Number of unique classes:",len(np.unique(data_train[:,0])))("Time series length:",len(data_train[0,1:]))

Figure 13-8 displays the basic summary statistics. There are four thousand readings in the training set, which are grouped into five distinct classes, and each time series has a length of 140.

Figure 13-8. ECG 5000 summary

Let’s also consider how many of the readings belong to each of these classes.

# Calculate number of readings per class("Number of time series in class 1.0:",len(data_train[data_train[:,0]==1.0]))("Number of time series in class 2.0:",len(data_train[data_train[:,0]==2.0]))("Number of time series in class 3.0:",len(data_train[data_train[:,0]==3.0]))("Number of time series in class 4.0:",len(data_train[data_train[:,0]==4.0]))("Number of time series in class 5.0:",len(data_train[data_train[:,0]==5.0]))

The distribution is shown in Figure 13-9. Most of the readings fall in class 1, followed by class 2. Significantly fewer readings belong to clases 3, 4, and 5.

Let’s take the average time series reading from each class to get a better sense of how the various classes look.

# Display readings from each classforjinnp.unique(data_train[:,0]):dataPlot=data_train[data_train[:,0]==j]cnt=len(dataPlot)dataPlot=dataPlot[:,1:].mean(axis=0)(" Class ",j," Count ",cnt)plt.plot(dataPlot)plt.show()

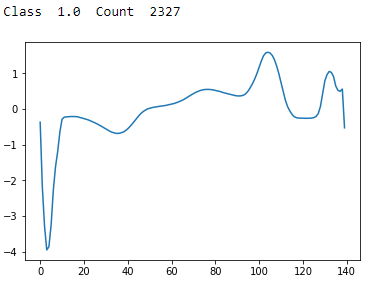

Figure 13-9. ECG 5000 class 1.0

Class 1 has a sharp trough followed by a sharp peak and stabilization. This is the most common type of reading.

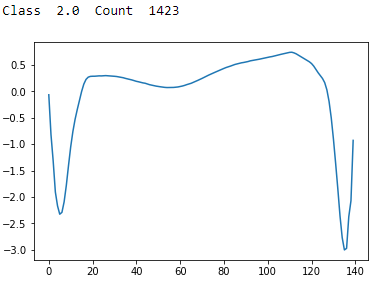

Figure 13-10. ECG 5000 class 2.0

Class 2 has a sharp trough followed by a recovery and then an even sharper and lower trough with a partial recovery. This is the second most common type of reading.

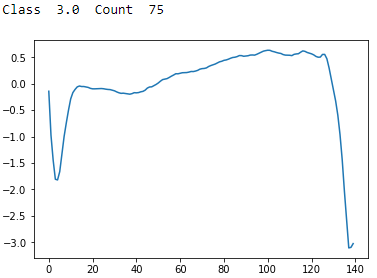

Figure 13-11. ECG 5000 class 3.0

Class 3 has a sharp trough followed by a recovery and then an even sharper and lower trough with no recovery. There are few examples of these in the dataset.

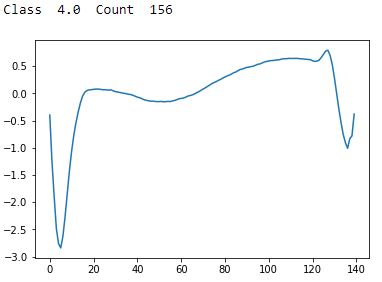

Figure 13-12. ECG 5000 class 4.0

Class 4 has a sharp trough followed by a recovery and then a shallow trough and stabilization. There are few examples of these in the dataset.

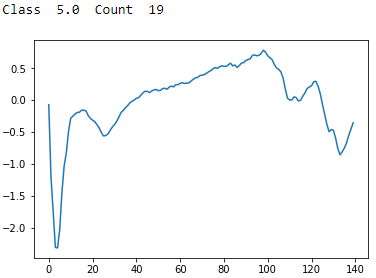

Figure 13-13. ECG 5000 class 5.0

Class 5 has a sharp trough followed by an uneven recovery, a peak, and then an unsteady decline to a shallow trough. There are very few examples of these in the dataset.

Training and Evaluation

As before, let’s normalize the data to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one. Then, we will fit the k-shape algorithm, setting the number of clusters to five this time. Everything else remains the same.

# Prepare data - ScaleX_train=TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariance(mu=0.,std=1.).fit_transform(X_train)X_test=TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariance(mu=0.,std=1.).fit_transform(X_test)# Train using k-Shapeks=KShape(n_clusters=5,max_iter=100,n_init=10,verbose=1,random_state=2019)ks.fit(X_train)

Let’s evaluate the results on the training set.

# Predict on train set and calculate adjusted Rand indexpreds=ks.predict(X_train)ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_train[:,0],preds)("Adjusted Rand Index on Training Set:",ars)

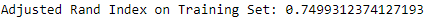

Figure 13-14 shows the adjusted Rand index on the training set. It is considerably stronger at 0.75.

Figure 13-14. ECG 5000 adjusted rand index on training set

Let’s evaluate the results on the test set, too.

# Predict on test set and calculate adjusted Rand indexpreds_test=ks.predict(X_test)ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_test[:,0],preds_test)("Adjusted Rand Index on Test Set:",ars)

The adjusted Rand index on the test set is much higher, too (see Figure 13-15). It is 0.72.

Figure 13-15. ECG 5000 adjusted rand index on test set

By increasing the training set to four thousand time series (from 23), we have a considerably better-performing time series clustering model.

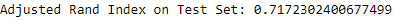

Let’s explore the predicted clusters some more to see just how homogenous they are. For each predicted cluster, we will evaluate the distribution of true labels. If the clusters are well-defined and homogenous, most of the readings in each cluster should have the same true label.

# Evaluate goodness of the clusterspreds_test=preds_test.reshape(1000,1)preds_test=np.hstack((preds_test,data_test[:,0].reshape(1000,1)))preds_test=pd.DataFrame(data=preds_test)preds_test=preds_test.rename(columns={0:'prediction',1:'actual'})counter=0foriinnp.sort(preds_test.prediction.unique()):("Predicted Cluster ",i)(preds_test.actual[preds_test.prediction==i].value_counts())()cnt=preds_test.actual[preds_test.prediction==i]\.value_counts().iloc[1:].sum()counter=counter+cnt("Count of Non-Primary Points: ",counter)

Figure 13-16 displays the homogeneity of the clusters.

Figure 13-16. ECG 5000 k-shape predicted cluster analysis

The majority of the readings within each predicted cluster belong to just one true label class. This highlights just how well defined and homogenous the k-Shape-derived clusters are.

Time Series Clustering Using k-Means on ECG 5000

For the sake of completeness, let’s compare the results of k-Shape with results from k-Means. We will use the tslearn library to perform the training and evaluate using the adjusted Rand index as before.

We will set the number of clusters as five, the number of max iterations for a single run as one hundred, the number of independent runs as one hundred, the metric distance as euclidean, and random state as 2019.

# Train using Time Series k-Meanskm=TimeSeriesKMeans(n_clusters=5,max_iter=100,n_init=100,\metric="euclidean",verbose=1,random_state=2019)km.fit(X_train)# Predict on training set and evaluate using adjusted Rand indexpreds=km.predict(X_train)ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_train[:,0],preds)("Adjusted Rand Index on Training Set:",ars)# Predict on test set and evaluate using adjusted Rand indexpreds_test=km.predict(X_test)ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_test[:,0],preds_test)("Adjusted Rand Index on Test Set:",ars)

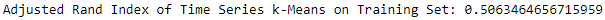

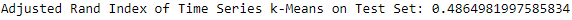

The TimeSeriesKMean algorithm runs even faster than k-Shape using the euclidean distance metric. But the results are not as good (see Figures 13-17 and 13-18).

Figure 13-17. ECG 5000 adjusted rand index on training set using k-means

The adjusted Rand index on the training set is 0.506.

Figure 13-18. ECG 5000 adjusted rand index on test set using k-means

The adjusted Rand index on the test set is 0.486.

Time Series Clustering Using Hierarchical DBSCAN on ECG 5000

Finally, let’s apply hierarchical DBSCAN, which we explored earlier in the book, and evaluate its performance.

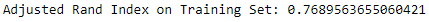

We will run HDBSCAN with its default parameters and evaluate performance using the adjusted Rand index.

# Train model and evaluate on training setmin_cluster_size=5min_samples=Nonealpha=1.0cluster_selection_method='eom'prediction_data=Truehdb=hdbscan.HDBSCAN(min_cluster_size=min_cluster_size,\min_samples=min_samples,alpha=alpha,\cluster_selection_method=cluster_selection_method,\prediction_data=prediction_data)preds=hdb.fit_predict(X_train.reshape(4000,140))ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_train[:,0],preds)("Adjusted Rand Index on Training Set:",ars)

The adjusted Rand index on the training set is an impressive 0.769 (see Figure 13-19).

Figure 13-19. ECG 5000 adjusted rand index on training set using HDBSCAN

The adjusted Rand index on the training set is an impressive 0.769.

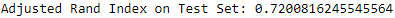

Let’s evaluate on the test set.

# Predict on test set and evaluatepreds_test=hdbscan.prediction.approximate_predict(\hdb,X_test.reshape(1000,140))ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_test[:,0],preds_test[0])("Adjusted Rand Index on Test Set:",ars)

The adjusted Rand index on the training set is an equally impressive 0.720 (see Figure 13-20).

Figure 13-20. ECG 5000 adjusted rand index on test set using HDBSCAN

Comparing the Time Series Clustering Algorithms

HDBSCAN and k-Shape performed similarly well on the ECG 5000 dataset, while k-Means performed worse.

However, we cannot draw strong conclusions by evaluating the performance of these three clustering algorithms on just a single time series dataset.

Let’s run a larger experiment to see how these three clustering algorithms stack up against one another.

First, we will load all the directories and files in the UCR Time Series Classification folder so we can iterate through them during the experiment. There are 85 datasets in total.

# Load the datasetscurrent_path=os.getcwd()file='\\datasets\\ucr_time_series_data\\'mypath=current_path+filed=[]f=[]for(dirpath,dirnames,filenames)inwalk(mypath):foriindirnames:newpath=mypath+"\\"+i+"\\"onlyfiles=[fforfinlistdir(newpath)ifisfile(join(newpath,f))]f.extend(onlyfiles)d.extend(dirnames)break

Next, let’s recycle the code for each of the three clustering algorithms and use the list of datasets we just prepared to run a full experiment. We will store the training and test adjusted Rand indices by dataset and measure the time it takes each clustering algorithm to complete the entire experiment of 85 datasets.

Full Run with k-Shape

The first experiment uses k-Shape.

# k-Shape ExperimentkShapeDF=pd.DataFrame(data=[],index=[vforvind],columns=["Train ARS","Test ARS"])# Train and Evaluate k-ShapeclassElapsedTimer(object):def__init__(self):self.start_time=time.time()defelapsed(self,sec):ifsec<60:returnstr(sec)+" sec"elifsec<(60*60):returnstr(sec/60)+" min"else:returnstr(sec/(60*60))+" hr"defelapsed_time(self):("Elapsed:%s"%self.elapsed(time.time()-self.start_time))return(time.time()-self.start_time)timer=ElapsedTimer()cnt=0foriind:cnt+=1("Dataset ",cnt)newpath=mypath+"\\"+i+"\\"onlyfiles=[fforfinlistdir(newpath)ifisfile(join(newpath,f))]j=onlyfiles[0]k=onlyfiles[1]data_train=np.loadtxt(newpath+j,delimiter=",")data_test=np.loadtxt(newpath+k,delimiter=",")data_joined=np.concatenate((data_train,data_test),axis=0)data_train,data_test=train_test_split(data_joined,test_size=0.20,random_state=2019)X_train=to_time_series_dataset(data_train[:,1:])y_train=data_train[:,0].astype(np.int)X_test=to_time_series_dataset(data_test[:,1:])y_test=data_test[:,0].astype(np.int)X_train=TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariance(mu=0.,std=1.)\.fit_transform(X_train)X_test=TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariance(mu=0.,std=1.)\.fit_transform(X_test)classes=len(np.unique(data_train[:,0]))ks=KShape(n_clusters=classes,max_iter=10,n_init=3,verbose=0)ks.fit(X_train)(i)preds=ks.predict(X_train)ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_train[:,0],preds)("Adjusted Rand Index on Training Set:",ars)kShapeDF.loc[i,"Train ARS"]=arspreds_test=ks.predict(X_test)ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_test[:,0],preds_test)("Adjusted Rand Index on Test Set:",ars)kShapeDF.loc[i,"Test ARS"]=arskShapeTime=timer.elapsed_time()

It takes approximately an hour to run the k-Shape algorithm. We’ve stored the adjusted Rand indices and will use these to compare k-Shape with k-Means and hdbscan soon.

Note

The time we measured for k-Shape is based on the hyperparameters we set for the experiment as well as the local hardware specifications for the machine on which the experiments were run. A different choice of hyperparameters and hardware specifications could result in dramatically different experiment times.

Full Run with k-Means

Next up is k-Means.

# k-Means Experiment - FULL RUN# Create dataframekMeansDF=pd.DataFrame(data=[],index=[vforvind],\columns=["Train ARS","Test ARS"])# Train and Evaluate k-Meanstimer=ElapsedTimer()cnt=0foriind:cnt+=1("Dataset ",cnt)newpath=mypath+"\\"+i+"\\"onlyfiles=[fforfinlistdir(newpath)ifisfile(join(newpath,f))]j=onlyfiles[0]k=onlyfiles[1]data_train=np.loadtxt(newpath+j,delimiter=",")data_test=np.loadtxt(newpath+k,delimiter=",")data_joined=np.concatenate((data_train,data_test),axis=0)data_train,data_test=train_test_split(data_joined,\test_size=0.20,random_state=2019)X_train=to_time_series_dataset(data_train[:,1:])y_train=data_train[:,0].astype(np.int)X_test=to_time_series_dataset(data_test[:,1:])y_test=data_test[:,0].astype(np.int)X_train=TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariance(mu=0.,std=1.)\.fit_transform(X_train)X_test=TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariance(mu=0.,std=1.)\.fit_transform(X_test)classes=len(np.unique(data_train[:,0]))km=TimeSeriesKMeans(n_clusters=5,max_iter=10,n_init=10,\metric="euclidean",verbose=0,random_state=2019)km.fit(X_train)(i)preds=km.predict(X_train)ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_train[:,0],preds)("Adjusted Rand Index on Training Set:",ars)kMeansDF.loc[i,"Train ARS"]=arspreds_test=km.predict(X_test)ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_test[:,0],preds_test)("Adjusted Rand Index on Test Set:",ars)kMeansDF.loc[i,"Test ARS"]=arskMeansTime=timer.elapsed_time()

It takes less than five minutes for k-Means to run through all 85 datasets.

Full Run with HDBSCAN

Finally, we have hdbscan.

# HDBSCAN Experiment - FULL RUN# Create dataframehdbscanDF=pd.DataFrame(data=[],index=[vforvind],\columns=["Train ARS","Test ARS"])# Train and Evaluate HDBSCANtimer=ElapsedTimer()cnt=0foriind:cnt+=1("Dataset ",cnt)newpath=mypath+"\\"+i+"\\"onlyfiles=[fforfinlistdir(newpath)ifisfile(join(newpath,f))]j=onlyfiles[0]k=onlyfiles[1]data_train=np.loadtxt(newpath+j,delimiter=",")data_test=np.loadtxt(newpath+k,delimiter=",")data_joined=np.concatenate((data_train,data_test),axis=0)data_train,data_test=train_test_split(data_joined,\test_size=0.20,random_state=2019)X_train=data_train[:,1:]y_train=data_train[:,0].astype(np.int)X_test=data_test[:,1:]y_test=data_test[:,0].astype(np.int)X_train=TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariance(mu=0.,std=1.)\.fit_transform(X_train)X_test=TimeSeriesScalerMeanVariance(mu=0.,std=1.)\.fit_transform(X_test)classes=len(np.unique(data_train[:,0]))min_cluster_size=5min_samples=Nonealpha=1.0cluster_selection_method='eom'prediction_data=Truehdb=hdbscan.HDBSCAN(min_cluster_size=min_cluster_size,\min_samples=min_samples,alpha=alpha,\cluster_selection_method=\cluster_selection_method,\prediction_data=prediction_data)(i)preds=hdb.fit_predict(X_train.reshape(X_train.shape[0],\X_train.shape[1]))ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_train[:,0],preds)("Adjusted Rand Index on Training Set:",ars)hdbscanDF.loc[i,"Train ARS"]=arspreds_test=hdbscan.prediction.approximate_predict(hdb,X_test.reshape(X_test.shape[0],\X_test.shape[1]))ars=adjusted_rand_score(data_test[:,0],preds_test[0])("Adjusted Rand Index on Test Set:",ars)hdbscanDF.loc[i,"Test ARS"]=arshdbscanTime=timer.elapsed_time()

It takes less than 10 minutes for hdbscan to run through all 85 datasets.

Compare all three time series clustering approaches

Now, let’s compare all three clustering algorithms to see which fared the best. One approach is to calculate the average adjusted Rand indices on the training and test sets, respectively, for each of the clustering algorithms.

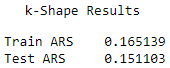

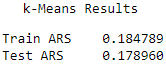

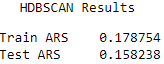

Here are the scores for each of the algorithms (see Figures 13-21, 13-22, and 13-23).

Figure 13-21. k-shape average adjusted rand index

Figure 13-22. k-means average adjusted rand index

Figure 13-23. HDBSCAN average adjusted rand index

The results are fairly comparable, with k-Means having the highest Rand indices, followed closely by k-Shape and HDBSCAN.

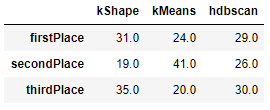

To validate some of these findings, let’s count how many times each algorithm placed first, second, or third across all the 85 datasets.

# Count top place finishestimeSeriesClusteringDF=pd.DataFrame(data=[],index=kShapeDF.index,\columns=["kShapeTest",\"kMeansTest",\"hdbscanTest"])timeSeriesClusteringDF.kShapeTest=kShapeDF["Test ARS"]timeSeriesClusteringDF.kMeansTest=kMeansDF["Test ARS"]timeSeriesClusteringDF.hdbscanTest=hdbscanDF["Test ARS"]tscResults=timeSeriesClusteringDF.copy()foriinrange(0,len(tscResults)):maxValue=tscResults.iloc[i].max()tscResults.iloc[i][tscResults.iloc[i]==maxValue]=1minValue=tscResults.iloc[i].min()tscResults.iloc[i][tscResults.iloc[i]==minValue]=-1medianValue=tscResults.iloc[i].median()tscResults.iloc[i][tscResults.iloc[i]==medianValue]=0

# Show resultstscResultsDF=pd.DataFrame(data=np.zeros((3,3)),\index=["firstPlace","secondPlace","thirdPlace"],\columns=["kShape","kMeans","hdbscan"])tscResultsDF.loc["firstPlace",:]=tscResults[tscResults==1].count().valuestscResultsDF.loc["secondPlace",:]=tscResults[tscResults==0].count().valuestscResultsDF.loc["thirdPlace",:]=tscResults[tscResults==-1].count().valuestscResultsDF

k-Shape had the most first place finishes, followed by HDBSCAN. k-Means had the most second place finishes, performing neither the best but also not the worst on the majority of the datasets (see Figure 13-24).

Figure 13-24. Comparison summary

Based on this comparison, it is hard to conclude that one algorithm universally trounces all the others. While k-Shape has the most first place finishes, it is considerably slower than the other two algorithms.

And, k-Means and HDBSCAN both hold their own, winning first place on a healthy number of datasets.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we explored time series data for the first time in the book and demonstrated the power of unsupervised learning to group time series patterns based on their similarity to one another and without requiring any labels.

We explored three clustering algorithms in detail - k-Shape, k-Means, and HDBSCAN. While k-Shape is regarded as the best of the bunch today, the other two algorithms perform quite well, too.

Most importantly, the results from the 85 time series datasets we worked with highlight the importance of experimentatione. As with most of machine learning, no single algorithm trounces all other algorithms.

Rather, you must constantly expand your breadth of knowledge and experiment to see which approaches work best for the problem at hand. Knowing what to apply when is the hallmark of a good data scientist.

With the many different unsupervised learning approaches you’ve learned through this book, hopefully you will be better equipped to solve more of the problems you face going forward.

1 The paper is publicly available here.

2 For more on the hyperparameters, please visit the official k-Shape documentation.

3 For more on the Rand index.