Let’s set up a Spin and PASM template and make sure you can compile the Spin and PASM program, that you can connect to the Propeller and download the binary file, and that you can see the output.

A few notes: Spin is sensitive to indentation (PASM is not). Comments begin with a single quote (') and continue for the remainder of the line. Block comments are delineated by curly braces ({ and }).

In general, strive for simplicity and clarity in the code when starting out (even at the expense of speed). Once the code is working, you can tweak portions to speed them up if you need better performance.

Neither Spin nor PASM is sensitive to case. Nevertheless, we will hold to these conventions:

- All caps are used for block identifiers (CON, OBJ, VAR, PUB, PRI, and DAT), constants, and function names (also called method names).

- Words in function names are separated by underscores (_).

- Variable names use lowercase and “camel case” (capitalized second and later words, for example, sampsPerSecond).

- An underscore is used as the first letter of variables in PASM code.

- A lowercase p is used as the first letter of array address variable names (“pointers”) in functions.

Finally, Spin has a flexible and friendly way of representing numbers. Prepend $ (dollar sign) for hexadecimal numbers and % (percent sign) for binary; numbers without a preceding symbol are decimal numbers. You can insert underscores anywhere in a number, and they are ignored by the compiler. They are syntactic “sugar” to help reduce errors—particularly with binary numbers

with long strings of ones and zeros. So, you can say this:

1 pi4 := 3 _1415 ' the _ is ignored pi4 =31415

2 pi4 := $7A_B7

3 pi4 := %0111 _1010_1011_0111

Binary and Decimal and Hex, Oh My

The Propeller (and computers in general) store numbers in binary format.

- In a decimal representation of a number (what we are used to in real life), digits can range from 0 to 9, and a number like 42 is read as “2 times 1 plus 4 times 10.”

- In a binary representation, only the digits 0 and 1 are allowed, and the number 42 is represented as 101010, which is read as (right to left) “0 times 1 plus 1 times 2 plus 0 times 4 plus 1 times 8 plus 0 times 16 plus 1 times 32” (32 + 8 + 2 = 42).

- In a hexadecimal (or hex) representation, digits range from 0 to 9 and A to F (where A is 10, B is 11, up to F, which is 15). The number 42 is represented as 2A, which is read as “A, which is 10, times 1 plus 2 times 16” (32 + 10 = 42).

In this book (and many computer books), a hex number is written as 0x2A (the 0x signals that the number should be interpreted as a hex number). However, in a Spin or PASM program, that would be written as $2A. In a C program, that would be written as 0x2A.

In this book and in C, a binary number is written as 0b00101010. In Spin and PASM, it is written as %0010_1010.

Yes, I know, it would be nice if we could all agree to use the same vocabulary, but what a boring world that would be!

1 theAnswerDec := 42 ' decimal 42

2 theAnswerHex := $2A ' hexadecimal 0x2A

3 theAnswerBin := %00101010 ' binary 0 b00101010.

By convention, we show only as many decimal numbers as needed, so for example for the number 7, we don’t say 007, just 7. However, also by convention we always show hex numbers in groups of two, so we would write that as $07 or 0x07, and in binary we show groups of eight: %0000_0111 or 0b00000111.

There are 8 binary digits per byte and 2 bytes per word (16 bits) and 4 bytes per long (32 bits). A byte is a collection of 8 bits. A byte can contain unsigned numbers from 0 to 255; a word can contain numbers from 0 to 65,535; and a long can contain numbers from 0 to 4,294,967,295 (about 4 billion).

The advantage of a hex representation

is that each byte (a collection of 8 bits) can be succinctly and naturally written as two hex digits. The largest number that can be written in 8 bits is the number you and I know in decimal as 255 (5 times 1 plus 5 times 10 plus 2 times 100) or binary 11111111 (I won’t write out the sums here, but you should). In hex, that number is FF (15 times 1 plus 15 times 16). There are many advantages to this method of writing numbers and many resources on the Web for understanding it.

One enormously useful tool is a calculator app that has a “programmer’s mode” that can show numbers in the different bases (bases are the underlying number system, either binary, decimal, or hex).

3.1 Negative Numbers

If we decide that an eight-bit number is unsigned, then it can store numbers from 0 to 255 (%0000_0000 to %1111_1111: 1 times 1 plus 1 times 2 plus 1 times 4, etc., up to 1 times 128 = 255).

However, if we decide that an 8-bit number is signed, then it can store numbers from -128 to 127. The most significant bit is referred to as the sign bit, and if it is 1, then the number is a negative number. Thus, the same set of bits (e.g., i =%1111_1111) would be i = 255 if i were signed, and it would be i = –1 if i were unsigned.

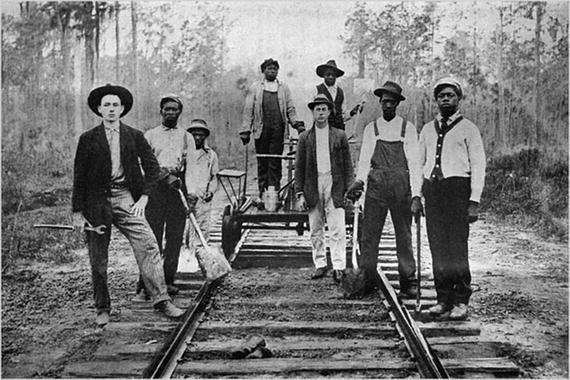

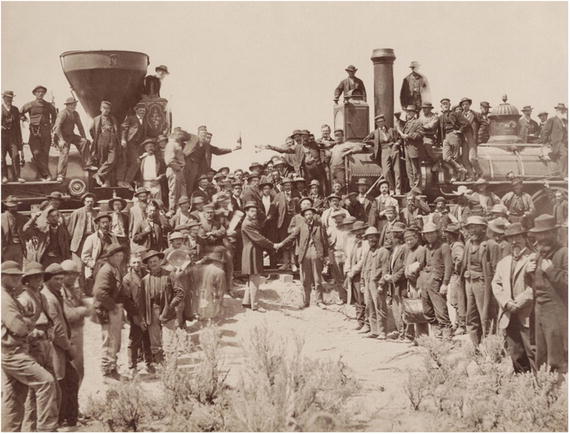

Negative numbers are stored in a “two’s-complement” representation.1 You don’t need to worry about the details of what that means, except to be careful when changing the size of storage from, for example, 8 bits to 32 bits. Now that we have “laid the rails” for our work (Figure 3-1 shows some actual rails!), let’s look at how the propeller implements memory.

Figure 3-1

A crew of railroad workers poses for the camera in 1911. Photographer unknown. In Nelson, Scott Reynolds (2007), Ain’t Nothing but a Man: My Quest to Find the Real John Henry, National Geographic Books, ISBN: 9781426300004

.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/51/A_crew_of_railroad_workers_poses_for_the_camera_in_1911.jpg

. Wikimedia Commons, no license attached.

3.2 Memory Layout

Absolute memory addresses increase from zero, incrementing by one for each byte. There are three storage lengths in the propeller: bytes, words (2 bytes), and longs (4 bytes).

Propellers are little-endian devices. Thus, the lowest byte of a long number is stored at a lower memory location than the higher bytes in that number. (Note that the Propeller happily allows you to modify any memory location!)

3.3 Spin Template

Let’s start with the Spin file. Listing 3-1 is a template that you can use to make sure your Propeller is working and connected and that the compiler and loader on your computer are working. There are a couple of options for the computer side. Parallax supports an excellent Propeller Tool2 (Windows only), and there is a cross-platform PropellerIDE tool3 (both of which have a compiler, program loader, and serial terminal included). I use separate command-line tools for compiling the code (openspin) and loading the Propeller (propeller-load), which are included with the PropellerIDE package.

The Propeller Tool and the PropellerIDE tool both include an editor that colorizes the code and handles indentation properly. You can also use a stand-alone text editor (such as Atom, emacs, and vi) and use command-line tools.

3.3.1 Hello, World

Trust Me, It’s Good for You!

I know this seems silly, but instead of downloading this file from GitHub or cutting and pasting this from the screen, type in the whole file by hand! It may seem like a waste of time, but I guarantee you that in the process of finding bugs and fixing them, you will learn way more than you can imagine.

1 {*

2 * Spin Template - curly braces are block comments

3 *}

4 ' single quotes are line comments

5 CON ' Clock mode settings

6 _CLKMODE = XTAL1 + PLL16X

7 _XINFREQ = 5_000_000

8

9 ' system freq as a constant

10 FULL_SPEED = (( _clkmode - xtal1) >> 6) * _xinfreq

11 ' ticks in 1ms

12 ONE_MS = FULL_SPEED / 1_000

13 ' ticks in 1us

14 ONE_US = FULL_SPEED / 1_000_000

15

16 CON ' Pin map

17

18 DEBUG_TX_TO = 30

19 DEBUG_RX_FROM = 31

20

21 CON ' UART ports

22 DEBUG = 0

23 DEBUG_BAUD = 115200

24

25 UART_SIZE = 100

26 CR = 13

27 LF = 10

28 SPACE = 32

29 TAB = 9

30 COLON = 58

31 COMMA = 44

32

33 OBJ

34 UARTS : " FullDuplexSerial4portPlus_0v3 " ' 1 COG for 3 serial ports

35 NUM : " Numbers " ' Object for writing numbers to debug

36

37 VAR

38 byte mainCogId, serialCogId

39

40 PUB MAIN

41

42 mainCogId := cogid

43 LAUNCH_SERIAL_COG

44 PAUSE_MS(500)

45

46 UARTS.STR(DEBUG, string (CR, LF, " mainCogId : "))

47 UARTS.DEC(DEBUG, mainCogId)

48 UARTS.STR(DEBUG, string (CR, LF, "Hello, World !", CR, LF))

49 repeat

50 PAUSE_MS(1000)

51

52 PUB LAUNCH_SERIAL_COG

53 " method that sets up the serial ports

54 NUM.INIT

55 UARTS.INIT

56 ' Add DEBUG port

57 UARTS.ADDPORT(DEBUG, DEBUG_RX_FROM, DEBUG_TX_TO, -1, -1, 0, %000000, DEBUG_BAUD)

58 UARTS.START

59 serialCogId := UARTS.GETCOGID

60 ' Start the ports

61 PAUSE_MS(300)

62

63 PUB PAUSE_MS(mS)

64 waitcnt(clkfreq /1000 * mS + cnt)

65

66 ' Program ends here

Listing 3-1

Spin Program Template for “Hello, World”

- Lines 1–4: Comments.

- Lines 5–31: Constants (CON) blocks. They are separated into individual blocks solely for purposes of organization.

- Lines 33–37: Objects (OBJ) block. The compiler will read the files named in quotes to the right of the colon (after appending .spin to the name) and assign constants and methods to the symbol to the left of the colon. So, all functions in Numbers.spin are available as NUM.FUNCTION_NAME. A function is a block of code that can be called, possibly with arguments (you will sometimes see them referred to as methods).

- Lines 39–40: Variables declaration block VAR. Variables declared here are initialized to zero. The size of memory is determined by the variable type (byte, word, or long).

- Lines 42–50: The first function in the top-level (or entry) file is executed by the Spin compiler in cog 0. By convention, we call it MAIN.

- Lines 52–65: Functions that can be called by MAIN.

The first CON block

is the declaration of a set of constants for the Propeller clock. For now, simply copy the lines. I’ll come back to what they mean later. The second and third blocks are constants for the serial port. In constant blocks, the constant name and value are separated by an equal sign (=). Later in the code, assignment to variables is done using :=.

The next block (OBJ) is like #include in C; it’s a way to bring in external libraries. The desired name for the library and the string containing the file name of the library (without the .spin extension) are separated by a colon.

LIBNAME : "LibFile" ' read in file LibFile.spin and assign it to LIBNAME

From now on you can refer to the functions and constants in that library by invoking this:

LIBNAME.LIBFUNCTION to call a function or method LIBFUNCTION in library LIBNAME and LIBNAME#LIBCONSTANT to refer to a constant LIBCONSTANT defined in that library4.

The next block is a VAR where

variables are declared and initialized to zero.

Finally, the actual program begins at the first PUB method (named MAIN by convention). This block is run automatically after the program is loaded on the Propeller. This is the “entry point” into the program (like int main() in C). From within MAIN you can call functions with any required arguments in parentheses. If there are no arguments, there is no need for the parentheses.

In the template some of the function calls are part of Spin (cogid, for example), some are written by us (PAUSE_MS), and some are part of an object or library (UARTS.STR). Functions may return a value (for example, cogid does), which we can assign to a variable using := (a colon followed by the equal sign).

3.3.2 Running the Program

If you have openspin and propeller-load (or propman) on your path (Linux and macOS),5 the following are the commands to run from a terminal.

The following will create a .binary file:

$ openspin ./spin_template.spin

The following command will send it to the Propeller. Your serial port number will differ. The propeller-load program is invoked with the -r and -t flags that instruct the Propeller to run the program after it is downloaded and to start a terminal to view messages from the Propeller, respectively.

$ propeller-load -p /dev/cu.usbserial-A103FFE0 \

-t -r spin_template.binary

Propeller Version 1 on /dev/cu.usbserial-A103FFE0

Loading spin_template.binary to hub memory

3924 bytes sent

Verifying RAM ... OK

[Entering terminal mode. Type ESC or Control-C to exit.]

mainCogId: 0

Hello, World!

Congratulations! You have successfully seen that the Propeller is attached, that you can communicate with it, that the clock is set correctly, and that you can compile and download a program and view the output. That’s a lot!

3.4 PASM Template

Let’s add a minimal PASM cog called HELLO. Here we will include the code for the new cog at the end of the template.spin file (copy the template to hello0.spin). Later, when we start working on the real code, we will put the Spin and PASM code in their own files. The main changes in the file are shown in Listing 3-2.

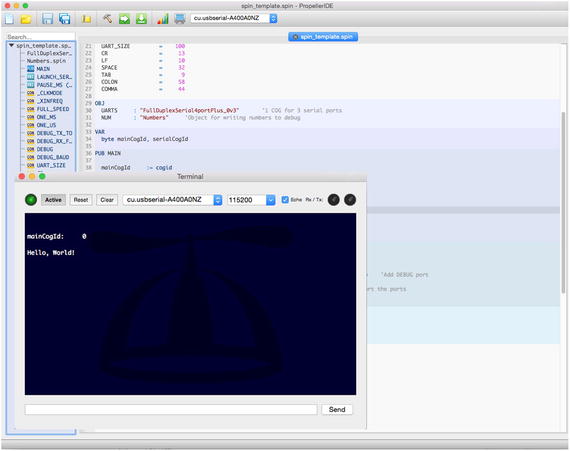

Figure 3-2

Main window and terminal window for PropellerIDE

1 ...

2 ' in VAR

3 byte helloCogId

4

5 ...

6 ' in MAIN

7 helloCogId := -1

8 helloCogId := cognew(@HELLO, 0)

9

10 UARTS.STR(DEBUG, string (CR, LF, " helloCogId : "))

11 UARTS.DEC(DEBUG, helloCogId)

12 UARTS.PUTC(DEBUG, CR)

13 UARTS.PUTC(DEBUG, LF)

14 ...

15

16 ' in a new DAT section at end

17 DAT ' pasm cog HELLO

18 HELLO ORG 0

19

20 :mainLoop

21 jmp #:mainLoop

22

23 FIT 496

Listing 3-2

Changes to spin template.spin to Include PASM Cog Code (ch3/pasm template.spin)

This PASM code is the text between the DAT block marker and the FIT 496 instruction. This program does very little; it just runs an infinite loop (the jmp command jumps to the line labeled :mainLoop, which brings it right back to the jmp...).

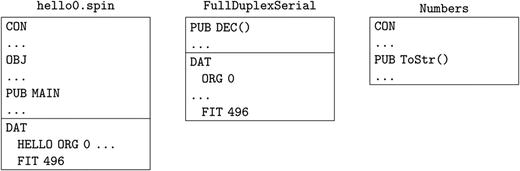

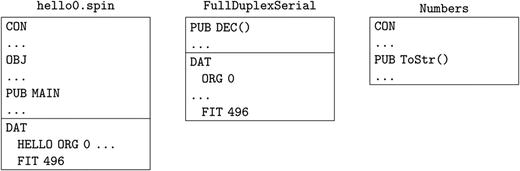

The structure of the files and cogs is as follows. The file hello0.spin has the MAIN method, as well as a DAT section where the PASM program HELLO is defined. The file FullDuplexSerial has a Spin part where the methods DEC, HEX, PUTC, and so on, are defined, as well as a DAT part for the PASM code. Finally, the Numbers.spin file has only Spin code.

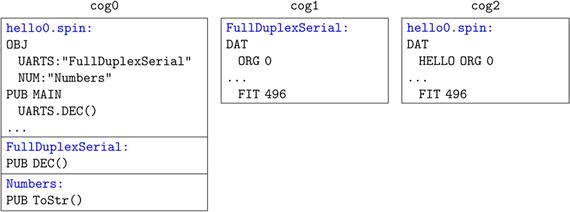

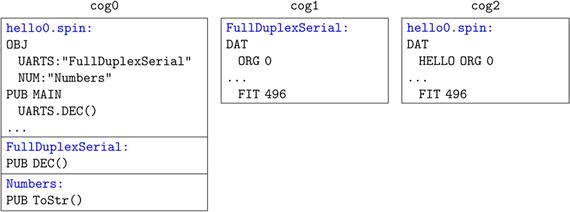

However the “cog view” of the Propeller is more like the following. The MAIN method calls a UARTS method (in the FullDuplexSerial file/object) named UARTS.START. This method includes a call to cognew that starts a new cog that manipulates the serial port lines with the correct timing. In addition, the MAIN method itself calls cognew. Each cognew command launches a new cog with code that is in the appropriate DAT section. At the end of the MAIN method, the cogs are as follows:

So, for example, when MAIN calls

the method UARTS.DEC(), that code runs in cog 0, but it passes instructions to cog 1 that does the actual hardware manipulations of the serial line.

Cog 0 isn’t a special cog. When the Propeller boots, it loads a Spin interpreter into cog 0 that reads, interprets, and executes Spin code (code that is stored in hub memory). You can launch a second cog that also has a Spin interpreter, but in this tutorial, we will load PASM code into those new cogs.

Now run this (along with print statements to print out the serial and hello cog IDs):

% propman -t hello0.binary

pm.loader: [cu.usbserial-A400A0NZ] Preparing image... pm.loader: [cu.usbserial-A400A0NZ] Downloading to RAM... pm.loader: [cu.usbserial-A400A0NZ] Verifying RAM... pm.loader: [cu.usbserial-A400A0NZ] Success!

Entering terminal on cu.usbserial-A400A0NZ

Press Ctrl+C to exit

--------------------------------------

mainCogId: 0

Hello, World

serialCogId: 1

helloCogId: 2

(In this case I used the propman command

instead of propeller-load.) Congratulations again! You have started a PASM cog successfully.

3.5 Template for PASM Code in a Separate File

Unless your PASM code is very simple, you will want to move that code to a separate file. This will allow you to turn that functionality into an object that can be included in any project.

Edit hello0.spin and create two files: hello_Demo.spin and hello_pasm.spin. The file hello_Demo is derived from hello0 with the changes shown in Listing 3-3.

1 ...

2 OBJ

3 ... ' add this

4 HELLO: " hello_pasm " 'pasm cog is in a different file

5

6 PUB MAIN

7 ...

8

9 helloCogId := -1

10 ' replace cognew (@HELLO, 0) with the following 2 lines

11 HELLO.INIT

12 helloCogId:= HELLO.START

13

14 ' HELLO.STOP would stop the cog

15 ...

16 ' delete the DAT section

Listing 3-3

Changes to pasm template.spin When PASM Code Is in a Separate File (ch3/hello Demo.spin and ch3/hello pasm.spin)

The line in the OBJ section will include the hello_pasm code as HELLO. Next, instead of calling cognew directly, you initialize and start the cog by calling functions in the library HELLO. The HELLO.START method will return the number of the newly launched cog.

Create a new file called hello_pasm.spin and type in the code in Listing 3-4.

1 {*

2 * pasm template for code in a separate file from main

3 *}

4

5 VAR

6 byte ccogid

7

8 PUB INIT

9 ccogid := -1

10

11 PUB START

12 STOP

13 ccogid:=cognew(@HELLO, 0)

14 return ccogid

15

16 PUB STOP

17 if ccogid <> -1

18 cogstop(ccogid)

19 ccogid:= -1

20

21 DAT ' pasm cog HELLO

22 HELLO ORG 0

23

24 : mainLoop

25 jmp #:mainLoop

26

27 FIT 496

Listing 3-4

Contents of hello_pasm.spin

- Lines 5–6: Declare a variable ccogid that is local to this file. ccogid is either 0–7 for a valid cog number or -1 if the cog is not running.

- Lines 8–9: The INIT method, well, initializes variables. In this case, you want to ensure that ccogid is set to -1 to indicate that the cog is not running (when the variable is first declared, it is set to zero, which isn’t what you want).

- Lines 11–19: The START and STOP methods are straightforward. Start a new cog (after stopping it, in case it is already running) and return the number of the newly launched cog. To stop a cog, make sure it really is running and then stop it. Set the cog ID to -1 to indicate that it is no longer active.

3.6 Summary

In this chapter, I laid some rails for running a new PASM cog. The cog does nothing so far. Again, I want to emphasize that once you launch a cog, it is entirely separate from other cogs. It has access to hub memory, but if two cogs want to share information through the hub, they both need some way to know where to look. The most confusing part of programming PASM for beginners is getting information into and out of the cogs (at least it was for me!).

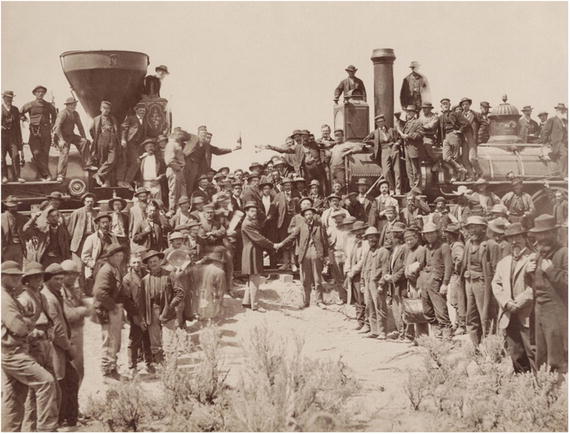

Shall we try to connect the cogs? Figure 3-3 is a famous photograph of the ceremony when the two halves of the US Transcontinental railroad met and one could take a train from New York to San Francisco! Take a break and continue with the next chapter when you are ready.

Figure 3-3

Connecting the Eastern and Western halves of the Transcontinental Railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah, May 10, 1869.

Footnotes

4

The two libraries are available on the Propeller Object Exchange (obex.parallax.com) or in the GitHub repo (

https://github.com/sanandak/propbook-code

).

5

Using sh or bash on a Mac, the command is as follows: export PATH=/Applications/PropellerIDE.app/Contents/MacOS/:$PATH. On Linux, the command is as follows: export PATH=/opt/parallax/bin:$PATH.