Parallax and the community have put enormous effort into bringing a C compiler to the Propeller. The advantage to using C is that it is a stable, established language with a large knowledge base. In addition, there are hundreds of books and web sites devoted to teaching C, and you can use many libraries and pieces of example code in your programs. Many of the programs that run the backbone (or the engine, Figure 12-1) of the Internet are written in C.

12.1 The C Language

This section is a short primer on C. I encourage you to get a copy of The C Programming Language by Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie, which is the authoritative guide to C. Here are a few important rules

to remember:

- C is case sensitive.

- Statements must end with a semicolon (;).

- Blocks are enclosed in paired curly braces (indentation is not important).1 while (x < 100) {2 x += 1;3 }

- Block comments have /* at the beginning and */ at the end. Line comments start with //.

- Variable naming follows the same rules as in Spin.

- Numbers are in decimal if naked, hexadecimal if preceded by 0x, and binary if preceded by b.1 /* a block comment2 * three assignments that do the same thing3 */4 x = 42; // decimal . This is a line comment5 x = 0x2A; // hex6 x = b00101010; // binaryHere are some Spin and C parallels:

Figure 12-1

In the engineer’s cab on the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad. Photographer Jack Delano, Library of Congress, Farm Security Administration archives (

https://goo.gl/pHmY5t

).

1 #define NSAMPS_MAX 128

Listing 12-1

define Statements in C

1 #include <stdio.h>

2 #include <propeller.h>

Listing 12-2

#include Statements in C

VAR: Variables

can be defined as either local variables that are available only within a function or as global variables that are available to all functions in the program. To define (reserve space for) a variable, do the following:

1 int nsamps, ncompr;

2 char packBuf[512];

3 unsigned int spiSem;

Variable definitions are either for individuals (nsamps, etc.) or for arrays (packBuf[512]). The type of the variable precedes its name. Variables types are the integers char, short, int (8-, 16-, and 32-bit, respectively), and a 32-bit float. The integer types can be either signed or unsigned.

Assignment and math

: These are similar to Spin but use an equal sign instead of :=. Addition, multiplication, and division are the same as in Spin. The modulo operator is the percent sign (%).

1 int x, y, z;

2 x = 12;

3 x += 42;

4 y = x/5; // integer division

5 z = x % 5; // remainder of x/5

6 z = x++; // post - increment: increment x, and store in z

7 z = ++x; // pre - increment: store x in z, then increment x

Relational and logical operators

: These are similar to Spin, but with these differences:

- The not equal operator is !=.

- The AND operator is && and the OR operator is ||.

- The NOT operator is !.

- The “less-than-or-equal and “greater-than-or-equal” relations are <= and >=.”

In conditional statements, 0 (zero) is false, and any nonzero value is true.

Flow control

: There are four flow control statements.

- This is a for loop:1 /* for (<init >; <end condition >; <per - loop action >)2 * The most common for - loop runs N times3 * number of times as below.4 * An infinite loop is for (;;) { <stmts > }.5 * (you can have blank init, end or per - loop)6 */7 for(i=0; i<N; i++) {8 x++;9 y--;10 }

- These are while and do...while:1 // while loop. The block only runs if the relation is true.2 while (x < 100) {3 y++;4 }5 // do ... while loop. The block always runs once6 // and then check the relation.7 do {8 y++9 } while (x < 100);

- This is a switch... case :1 switch(menuItems) {2 case MENUITEM0: // if menuItems == MENUITEM0,3 do_menu0(); // execute block up to the break.4 break;5 /*** DANGER **6 * you must have a break at the end7 * of the case block.8 * the break will return control to the switch.9 * without the break, control will pass to the10 * next case block.11 *** YOU WERE WARNED **12 */13 case MENUITEM1:14 do_menu1();15 break;16 default: // you can include a case that handles17 // unknown values18 handle_unknownMenu();19 }

Pointers and arrays

: Every variable and array has a memory address. The address of variables is given thusly:

1 int x;

2 /* this defines a pointer to an int */

3 int *px;

4 x = 42;

5

6 /* this obtains the address of x and stores it in px */

7 px = &x;

8

9 /* this obtains the value stored at the location

10 pointed to by px */

11 y = *px; // now y is 42

Arrays

are stored in contiguous memory, and the address of the array is the address of the first element of the array.

1 int sampsBuf[128];

2 int packBuf[512];

3

4 // arrays are zero -based, sampsBuf[0]... sampsBuf[127]

5 y = sampsBuf[12];

6

7 // the memory address of an array is obtained by

8 // referring to the array.

9 // the n-th element of the array is obtained by

10 // adding n to the address, treating that as a pointer

11 // here we get the 12 th element (12 th int) of sampsBuf

12 y = *(sampsBuf +12);

13

14 // the compiler knows that packbuf is a char array

15 // so packBuf +12 refers to the 12 th element (12 th byte),

16 // in this case

17 z = *(packBuf +12);

Pointer arithmetic

is needed when you want to modify the value of variables in a function.

1 ...

2 int main() {

3 int x = 42;

4 int y;

5 int *px = &x;

6 y = incrementNum(x);

7 // x is still 42, but y is 43.

8 incrementNumPtr (px);

9 // x is now 43.

10 }

11

12 /* incrementNum - increment a variable

13 * args: n - variable to be incremented

14 * return: incremented value

15 */

16 int incrementNum(int n) { // n is a local copy of x. x is unaffected.

17 return (n++);

18 }

19

20 /* incrementNumPtr - increment the value of a variable.

21 * args: *pn - a pointer to an int

22 * return: none

23 * effect: the variable pointed to by pn is incremented

24 */

25 void incrementNumPtr(int *pn) {

26 // pn is a pointer to the int, and *pn is the int itself

27 *pn++; // * binds tightly, so parens (* pn)++ not needed.

28 }

12.2 Programming the Propeller in C

To program the Propeller with C code, we have to recognize a few constraints of the device. The first, and most critical, is that hub memory is limited to 32KB and that cog RAM is limited to 2KB. Next, the Propeller has eight cogs, and the C compiler and linker have to handle launching new cogs properly. In this book, I will discuss three cases (cases that I think cover most of the likely projects).

SimpleIDE creates a workspace when you first install it. If you have downloaded the repository from

https://github.com/sanandak/propbook-code.git

, then there is a SimpleIDE workspace in propbook-code. Select Tools ➤ Properties and set the workspace to the downloaded directory (.../propbook-code/SimpleIDE).

- If the size of the C program (after compiling) is less than approximately 30KB, then it will fit entirely in hub memory. The compiler will place your code into hub along with a kernel (approximately sized 2KB, for a total size of less than 32KB). The kernel is a program that copies instructions from your code into a cog and executes them. This is known as the large memory model (LMM). The main drawback of LMM is that every instruction resides in the hub and is copied to cog memory before execution, slowing down the program. In almost every way, though, this is a standard C program. Cogs can be launched and stopped; the counters and special registers like ina and outa can be read and set; the locks can be used; and so on.

- If there is a need for a faster speed from some part of the program, we can place that C code in a Cog-C file (with the extension .cogc). This part of the code must compile to assembly code that is less than 2KB in size, and it will be placed into cog RAM and run at full speed. The rest of the program will continue to operate under LMM mode. I call this the mixed-mode Cog-C model. The advantage is that the program will run at full speed. The drawback is that the assembly code produced by the compiler may not be as efficient as code that you write.

- The final model is where the speed-critical code is written in PASM and is saved on a cog. This cog is now fully under your control. You can optimize it for your needs (of course, as with the previous case, the code has to be less than 2KB in size). The rest of the code continues to run under LMM. This is called the mixed-mode PASM model.

12.2.1 SimpleIDE

To write the code, compile and link it, download it to the Propeller, and view the output, we will use the SimpleIDE application, which is an integrated development environment (IDE)

. This is a cross-platform IDE (Windows, Linux, and macOS) that is aware of all three of the models and does the detailed work of compiling the programs correctly and linking them in the right way.

The place to start with SimpleIDE is at

http://learn.propeller.com

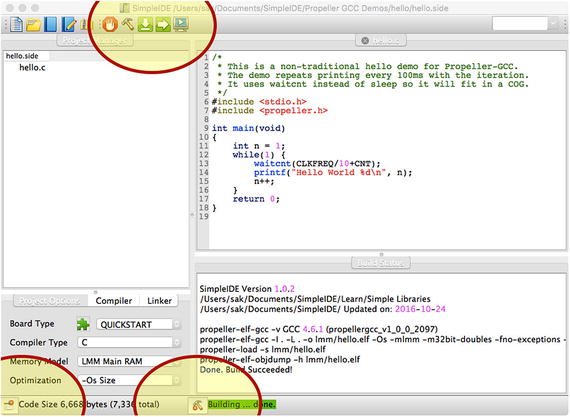

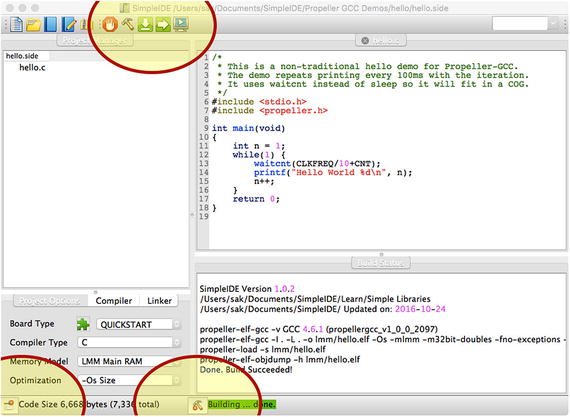

where you can download the program and step through a series of excellent tutorials on using the program and developing LMM projects (see Figure 12-2).

Figure 12-2

SimpleIDE window

with Project Manager button, Build Window button (at bottom of picture), and Build button (the hammer at the top of the picture) highlighted

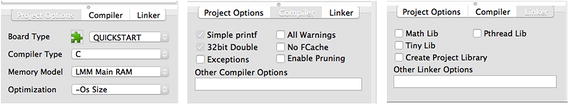

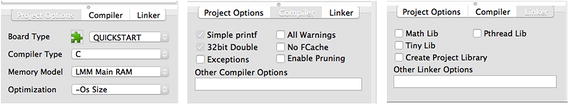

There are three tabs in the Project Manager: the Project Options tab, the Compiler tab, and the Linker tab. The settings shown in Figure 12-3 are good for the examples in this book, so make sure you set yours properly.

Figure 12-3

Settings for the Project Options, Compiler, and Linker tabs

12.2.2 Hello World

After installing SimpleIDE, you will have a number of examples in the Propeller GCC Demos folder (in the SimpleIDE workspace). One of those is called Welcome. Open the project file Welcome.side and build it; you should see messages in the build window ending with “Build Succeeded!” At the bottom of the window a message shows the size of the program (in this case, about 7KB). If the program successfully builds, you can download and run it on the Propeller and have the output displayed on a terminal by clicking the icon at the top that shows a screen with an arrow.

I have modified the code slightly, but it is very straightforward, as shown in Listing 12-3.

1 # include <stdio.h>

2 # include <propeller.h>

3

4 int main(void) {

5 int n = 1;

6 while (1) {

7 waitcnt(CLKFREQ/10 + CNT);

8 printf(" Hello World %d\n", n);

9 n++;

10 }

11 return 0;

12 }

Listing 12-3

Hello World Program in C (SimpleIDE/My Projects/ch11/Welcome.c)

Lines 1–2: The stdio library has the printf function. However, because it is a complex (and large) function, the Compiler tab includes the option to use a “Simple printf” that reduces the size somewhat. The propeller library has the Propeller-specific functions such as waitcnt and waitpeq and the special registers such as CNT, INA, and so on.

Lines 4–13: The main program is similar to the PUB MAIN method in Spin. This function shouldn’t exit; it should initialize some variables and then enter an infinite loop.

Line 5: Define the variable n and initialize it to 1.

Line 6: Enter an infinite loop.

Line 7:

waitcnt

is similar to the waitcnt in Spin, but it has only one argument. The processor will pause at this line until the counter value is equal to the argument of waitcnt. In this case, this is the current count value plus 1 second. The variable CLKFREQ contains the number of counts in 1 second (generally 80 million at top speed, but it depends on the external crystal and the phase-locked loop value).

Line 8: The printf function prints a formatted string to the terminal. Look at the manual page for printf for how to format numbers. In short, %d prints a decimal number, %x prints the number in hexadecimal format, and %f prints a floating-point value.

Line 9: Increment the value of n.

Running the program will result in the following in the terminal window with a new message every tenth of a second:

Hello World 1

Hello World 2

Hello World 3

...

12.2.3 Launching a New Cog

To launch a new cog in LMM, we must define a function and then pass that function to the

cogstart function

.

Start a new C project (Open ➤ New) named compr_cog0. Set the Project Options, Compiler, and Linker options as before.

For the purposes of display and discussion, I have split the file compr_cog0.c into three separate parts, but really all three parts are in one file. Every multicog program will have these three parts.

Part 1 in Listing 12-4 is the front matter where the libraries are included, the shared memory for the stack and the shared variables is set aside, and the constants are defined.

1 /*

2 compr - cog0.c - start a new cog to perform compression.

3 */

4

5 /* libraries */

6 # include <stdio.h>

7 # include <propeller.h>

8

9 /* defines */

10

11 // size of stack in bytes

12 # define STACK_SIZE_BYTES 200

13 // compression constants

14 # define NSAMPS_MAX 128

15 # define CODE08 0b01

16 # define CODE16 0b10

17 # define CODE24 0b11

18 # define TWO_BYTES 0x7F // any diff values greater than this are 2 bytes

19 # define THREE_BYTES 0 x7FF // diff values greater than this are 3 bytes

20

21

22 /* global variables */

23 // reserved space to be passed to cogstart

24 static unsigned int comprCogStack[STACK_SIZE_BYTES >> 2];

25

26 // shared vars

27 volatile int nsamps;

28 volatile int ncompr;

29 volatile int sampsBuf[NSAMPS_MAX];

30 volatile char packBuf[NSAMPS_MAX <<2]; // 128 * 4

31 volatile int comprCodesBuf[NSAMPS_MAX >>4]; // 128 / 16

Listing 12-4

Part 1: Front Matter

for File compr_cog0.c

Line 12: The stack is a region of memory used by the kernel to store internal variables and state. It should be at least 150 bytes plus 4 bytes per function call in the cog.

Lines 14–19: Constants

used by all cogs

.

Line 24: Declare and reserve space for the stack here.

Lines 27–31: Shared variables have a volatile qualifier to signal the compiler not to remove them during optimization. If the compiler thinks a variable is unused, it won’t reserve space for it. However, it is possible that a variable is used by a Spin or PASM cog unknown to the compiler.

Part 2, shown in Listing 12-5, is the code for the cog. Define a function that is called by the main cog. This function (and any functions that it calls) will run in a separate cog from the main cog. However, this cog will have access to the variables declared earlier. Those are global variables and available to all functions in the file.

1 /* cog code - comprCog

2 use nsamps and ncompr to signal with main cog

3 start compression when nsamps != 0

4 signal completion with ncompr > 0

5 signal error with ncompr = 0

6 compress sampsBuf to packBuf - NOT DONE YET

7 populate comprCodesBuf - NOT DONE YET

8 - args: pointer to memory space PAR - UNUSED

9 - return: none

10 */

11 void comprCog(void *p) {

12 int i, nc, nbytes, codenum, codeshift, code;

13 int diff, adiff;

14

15 while (1) {

16 if (nsamps == 0) {

17 continue; // loop continuously while nsamps is 0

18 } else {

19 // perform the compression here

20 if (nsamps > NSAMPS_MAX || nsamps < -NSAMPS_MAX) {

21 ncompr = 0; // signal error

22 nsamps = 0;

23 continue;

24 }

25 ncompr = 3; // signal completion

26 nsamps = 0; // prevent another cycle from starting

27 }

28 }

29 }

Listing 12-5

Part 2: Compression Cog Code

in File compr_cog0.c

Line 11: The cog function

definition. void comprCog() means that this doesn’t return any value. The argument (void *p) means

that an address is passed in—this is the equivalent of PAR. However, because we are using the global variables to pass information between cogs, we won’t use PAR.

Lines 12–13: Local variables used by the cog.

Line 15: Infinite loop that contains the actual code that does the work of the cog.

Lines 16–18: If nsamps is set to nonzero by main, enter the section that does the work.

Lines 20–26: Error checking and, finally, the work of this cog. Set ncompr to 3 and nsamps to 0. (We will add code to do the actual compression later.)

Part 3, shown in Listing 12-6, is the entry point for the program, including the main function and the code that runs first. Again, this cog has access to the global variables. It also starts the new cog and interacts with it by setting and reading variables in those global variables.

1 /* main cog - initializes variables and starts new cogs.

2 * don 't exit - start infinite loop as the last thing.

3 */

4 int main(void)

5 {

6 int comprCogId = -1;

7 int i;

8

9 nsamps = 0;

10 ncompr = -1;

11

12 printf(" starting main \n");

13

14 /* start a new cog with

15 * (1) address of function to run in the new cog

16 * (2) address of the memory to pass to the function

17 * (3) address of the stack

18 * (4) size of the stack, in bytes

19 */

20 comprCogId = cogstart (&comprCog, NULL, comprCogStack, STACK_SIZE_BYTES);

21 if(comprCogId < 0) {

22 printf(" error starting compr cog \n");

23 while (1) {;}

24 }

25

26 printf(" started compression cog %d\n", comprCogId);

27

28 /* start the compression cog by setting nsamps to 1 */

29 sampsBuf[0] = 0xEFCDAB;

30 nsamps = 1;

31

32 /* wait until the compression cog sets ncompr to a non -neg, number */

33 while(ncompr < 0) {

34 ;

35 }

36

37 printf(" nsamps = %d, ncompr = %d\n", nsamps, ncompr);

38 printf(" samp0 = %x, packBuf = %x %x %x\n", sampsBuf[0], packBuf[0], packBuf[1], packBuf[2]);

39

40 while (1)

41 {

42 ;

43 }

44 }

Listing 12-6

Part 3: Main Code

in File compr_cog0.c

Line 20: This is the key in main. The

cogstart function

takes four arguments. The first is the address of the function to place in the new cog: &comprCog. The ampersand symbol (&) in C is to obtain the address of a variable or function. The next argument is the address of memory that will be passed to the cog in PAR (the “locker number” in the analogy in Chapter 6). In this case, because we are using global variables to exchange information, we won’t use PAR and can pass NULL (which is, as it states, the null pointer). The third and fourth arguments are the address of the reserved stack space and its length in bytes, respectively. The stack is a region of memory that the kernel needs to store variables and counters.

Line 30: Here we set nsamps=1, which signals the compression cog to begin its work.

Lines 33–35: The compression cog

will set ncompr to a non-negative number when it completes its work. The main cog waits in this loop until it sees that the compression cog is finished.

Lines 37–38: Print out the results.

nsamps

should now be zero, and ncompr should now be non-negative.

Line 40: Enter an infinite loop, doing nothing.

The output from running this program is as follows:

starting main

started compression cog 1

nsamps = 0, ncompr = 3

samp0 = EFCDAB, packBuf = 0 0 0

We have shown that we can communicate with the compression cog. How fast is it? To compare this to the Spin and PASM compression codes from the previous chapters, let’s implement the compression code.

12.2.4 Compression Code in C

We will edit comprCog to include the packing. Replace the code with the code in Listing 12-7. This forms the difference between successive samples and checks the length of the difference. Depending on that length, it saves the difference as either 1, 2, or 3 bytes of packBuf. (For simplicity I haven’t included the part that populates the compression code comprCodesBuf.)

1 /* cog code - comprCog

2 use nsamps and ncompr to signal with main cog

3 start compression when nsamps != 0

4 signal completion with ncmopr > 0

5 signal error with ncompr = 0

6 compress sampsBuf to packBuf

7 populate comprCodesBuf - NOT YET DONE

8 - args: pointer to memory space PAR - UNUSED

9 - return: none

10 */

11 void comprCog(void *p) {

12 int i, nc, nbytes, codenum, codeshift, code;

13 int diff, adiff;

14

15 while (1) {

16 if(nsamps == 0) {

17 continue; // loop continuously while nsamps is 0

18 } else {

19 // perform the compression here

20 if(nsamps > NSAMPS_MAX || nsamps < -NSAMPS_MAX) {

21 ncompr = 0; // signal error

22 nsamps = 0;

23 continue;

24 }

25 for(i=0; i< nsamps; i++) {

26 if(i ==0) { // first samp

27 memcpy(packBuf,(char *)sampsBuf, 3);

28 nc = 3;

29 } else {

30 diff = sampsBuf[i] - sampsBuf[i -1];

31 adiff = abs(diff);

32 if(adiff < TWO_BYTES) {

33 nbytes = 1;

34 } else if(adiff < THREE_BYTES) {

35 nbytes = 2;

36 } else {

37 nbytes = 3;

38 }

39 // copy the correct number of bytes from diff

40 // to packBuf

41 memcpy(packBuf +nc,(char *)diff, nbytes);

42 nc += nbytes;

43 }

44 }

45 ncompr = nc; // signal completion

46 nsamps = 0; // prevent another cycle from starting

47 }

48 }

49 }

Listing 12-7

Compression Code Version 2 (ch11/compr cog1.side)

Line 26–28: Here the first sample is packed. The memcpy function will copy three bytes from the memory location sampsBuf to the memory location packBuf. There are no indices on the two arrays because we are operating on the start of both arrays (sampsBuf[0] is copied to packBuf[0..2]).

Lines 30–38: Form the difference and check the length of its absolute value.

Line 41: Copy the appropriate number of bytes of the difference to packBuf.

Lines 45–46: Signal the main cog that the compression is complete by setting ncompr to the number of bytes used in packBuf. Set nsamps to zero so that the loop doesn’t start again.

Add the following to the main cog:

1 printf(" nsamps = %d, ncompr = %d\n", nsamps, ncompr);

2 printf(" nsamps = %d, ncompr = %d\n", nsamps, ncompr);

3 printf(" samp0 = %x, packBuf = %x %x %x\n", sampsBuf[0], packBuf[0],

4 % packBuf[1], packBuf[2]);

5

6 // NEW CODE STARTS HERE >>>

7 for(i=0; i< NSAMPS_MAX; i++) {

8 sampsBuf[i] = 10000*(i +1000);

9 }

10

11 ncompr = -1;

12 t0 = CNT;

13 nsamps =128;

14 /* wait until the compression cog sets ncompr to a non -neg number */

15 while(ncompr < 0) {

16 ;

17 }

18 t0 = CNT - t0;

19 printf(" nsamps = %d, ncompr = %d\n", nsamps, ncompr);

20 printf(" samp0 = %x, packBuf = %x %x %x\n", sampsBuf[0], packBuf[0], packBuf[1], packBuf[2]);

21 printf(" dt = %d\n", t0);

22 // NEW CODE ENDS HERE <<<

23

24

25 while (1)

26 {

27 ;

28 }

Lines 7–9: Initialize sampsBuf.

Lines 12–18: Time how long it takes to perform the compression of 128 samples.

The results are as follows:

starting main

started compression cog 1

nsamps = 0, ncompr = 3

samp0 = EFCDAB, packBuf = AB CD EF

nsamps = 0, ncompr = 384

samp0 = 989680, packBuf = 80 96 98

dt = 151600

Table 12-1 compares the time taken to perform the compression in different languages. Clearly the fastest language is PASM, with C being about one-fifth the speed of PASM.

Table 12-1

Comparison of Time Taken to Compress Data Using Different Methods

Language | Number of Counts to Compress 128 Samples |

|---|---|

Spin code | 1.5 million counts |

PASM code | 22,000 counts |

C code (LMM) | 150,000 counts |

Spin is 1/10th the speed of C. In the next chapter, we will program the compression cog using Cog-C mode, where the cog code is downloaded to the cog all at once and run there. (Recall that in LMM mode the code is held on the hub, and one instruction at a time is downloaded and run on the cog.)

Because I know that I won’t be using pure-C mode for the final version, I’m not going to complete the compression and decompression code—that can be an exercise for you!

12.3 Summary

The simplest multicog technique in C is the large memory model (Listing 12-8 has a template to get you started). Here, all the code for all the cogs is stored in the hub, along with a kernel, which is a small program that copies instructions to each cog as needed and executes them. The code for each cog is defined as a function that is called by the cogstart instruction

.

- Set aside a chunk of memory for the stack.

- Define variables that will be shared by all the cogs.

- Define a function pureCCog whose code will be run in a separate cog (note that the external variables are available here).

- In the main function, call cogstart with the address of pureCCog. The external variables are available here too.

1 # define STACK_SIZE_INT 100

2 # define STACK_SIZE_BYTES 4 * STACK_SIZE_INT

3

4 // This is a critical number that is difficult to estimate

5 // In a later chapter I will discuss how to set it

6 static unsigned int pureCCogStack[STACK_SIZE_INT];

7

8 // these are shared with all cogs and must be

9 // declared `` volatile '''

10 volatile int variable1;

11 volatile int variable2;

12 volatile int dataArray[100];

13

14 // function to run in new cog - mustn't return

15 void pureCCog(void *p) {

16 while (1) {

17 ...

18 // access variable1, variable2, and dataArray[]

19 }

20 }

21

22 // the main function - mustn't return

23 int main() {

24 int pureCCogId;

25 // the calling protocol for new cogs

26 pureCCogId = cogstart (&pureCCog, NULL, pureCCogStack, STACK_SIZE_BYTES);

27 while (1) {

28 ...

29 // main cog can access variable1, variable2, dataArray[]

30 }

31 }

Listing 12-8

Template for Pure-C Code