It is relatively straightforward to debug Spin code. You can insert commands to print the value of variables to the terminal. This is a time-honored way to debug code, and though tedious, it works. In Listings 11-1 and 11-2, I show how I monitor the value of a variable.

1 PUB MAIN

2 ...

3 UARTS.STR(DEBUG, string(" nsamps = "))

4 UARTS.DEC(DEBUG, nsamps)

5 UARTS.PUTC(DEBUG, CR)

Listing 11-1

Debugging Spin Code

with Print Commands

Insert print statements like this in your Spin code, and you can examine the value of variables at different places.

I find that the verbose set of commands gets inconvenient, so I have defined a method called PRINTF.

1

2 PUB MAIN

3 ...

4 PRINTF(DEBUG, string(" nc "), nc, 1)

5 ...

6 '

7 ' Convenience method to print `n' to port `p' with the following format :

8 ' PRINTF(DEBUG, string(" nc "), nc, 1)

9 ' nc :3, 0x03, 0 b0000011

10 PRI PRINTF(p, lbl, n, len)

11 ' p is the serial port, lbl is the string label

12 ' n is the number to print

13 ' len is the number of bytes to display in the hex and binary

14 UARTS.STR(p, lbl)

15 UARTS.PUTC(p, COLON)

16 UARTS.DEC(p, n)

17 UARTS.STR(p, string(COMMA, " 0x"))

18 UARTS.HEX(p, n, len *2)

19 UARTS.STR(p, string(COMMA, " 0b"))

20 UARTS.BIN(p, n, len *8)

21 UARTS.PUTC(p, CR)

22 UARTS.PUTC(p, LF)

Listing 11-2

Convenience Method to Print Out a Variable’s Value

We can’t do the same in PASM code, though. There isn’t a simple way to print to the terminal from PASM code, so I will demonstrate two different methods for examining variable values

in PASM. These methods of debugging are referred to as logging (see Figure 11-1 for another example of logging; the size of those logs is astonishing and the sight of them cut down is quite sad!)

Figure 11-1

Redwood logs on train from forest to mill.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9a/Redwood_Logging_Train.jpg

.

11.1 Logging to a Hub Array

The first logging technique is to save values to a hub array

that can be printed out at leisure. The second is to write a long from one cog to another (from a PASM cog to a Spin cog) using a set of hardware pins and Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI). Here I will look at the first technique. We already looked at the SPI logging in Chapter 7.

- 1.We will define a new array in Spin called logBuf.

- 2.We will define a new variable in the PASM code called clogBufPtr.

- 3.Before the cog is launched, we will place the address of logBuf into clogBufPtr.

Recall from Chapter 6 that there are two ways to pass parameters to a PASM cog: by using the cognew command and by storing the parameter in the cog code before it is launched. We are using the second method in Listing 11-3.

1 CON

2 LOGLEN = 256

3

4 VAR

5 logBuf[LOGLEN]

6

7 PUB START

8 _clogBufPtr := @logBuf

9 ccogid := cognew(@STEIM, @myns)

10 ...

11

12 DAT 'pasm cog

13 STEIM ORG 0

14

15 ... instructions

16 rdlong _cns _cnsPtr wz

17

18 ... variables

19 _ccode24 long CODE24

20

21 _clogBufPtr long 0

22

23 ... reserved space

24 _cnsPtr res 1

25

26 FIT 496

27 ... system registers (PAR, CNT, etc)

Listing 11-3

Debugging PASM Code by Passing the Address of the Log Buffer in a Register

We can now write to logBuf from PASM

, and the Spin code can print out those values. There is one important caveat: the PASM code and the Spin code run at very different speeds. The PASM code will populate the logBuf array, and at some later time, the Spin code will print it out. For that reason, you should include a label during logging. This label will be some unique identifier that tells you where the log value was written, during which iteration of the loop, and so on.

11.2 Spin Code

Add the following to steim_pasm.spin:

1 CON

2 LOGLEN = 256

3 ...

4 VAR

5 byte logIdx

6

7 long logBuf[LOGLEN]

8

9 PUB GETLOG

10 '' return address of log array

11 return @logBuf

12

13 PUB GETLOGLEN

14 '' return length of log

15 return logIdx

Here we define a new array where the log values will be stored, as well as new methods GETLOG and GETLOGLEN that return the address and populated length of that array.

In the main Spin file steim_pasm_Demo.spin, you can use the code in Listing 11-4 to print out the contents of the log array.

1 VAR

2 byte loglen

3 long logBufPtr

4

5 PUB MAIN

6 ...

7

8 logBufPtr := COMPR.GETLOG

9 loglen := COMPR.GETLOGLEN

10 repeat j from 0 to loglen -1

11 UARTS.HEX(DEBUG, long [logBufPtr][j], 8)

Listing 11-4

Debugging PASM Code by Sharing a Log Buffer; Spin Code

11.3 PASM Code

Populating the log array is done with wrlong instructions in PASM. The hub address of the log array is available in _clogBufPtr. We first save that value to _clogBufPtrSav so that we can reset to that location when we reach the end of the array.

In Listing 11-5, we implement the logging code. In addition to the storage for the logged data itself, we define a variable _clogIdx and a constant _clogMaxIdx. Every time we write to the log array, we increment the former; when the index reaches the end of the array, we reset the index to the beginning of the array.

1

2 mov r0, par

3 add r0, #16

4 rdlong _ccomprcodebufPtr, r0

5

6 ''>>> ADD THIS TO INITIALIZATION SECTION OF PASM CODE

7 call #INIT_LOG

8 ''<<<

9 mov _cj, #0 ' j-th samp

10

11 ''>>> ADD THESE SUBROUTINE DEFENITIONS

12 INIT_LOG

13 mov _clogIdx, #0

14 mov _clogBufPtr, _clogBufPtrSav

15 INIT_LOG_ret ret

16

17 LOG

18 '' write logVal to logBuf

19 '' increment logIdx

20 '' treat as circular buffer

21 wrlong _clogVal, _clogBufPtr

22 add _clogBufPtr, #4

23 add _clogIdx, #1

24 wrlong _clogIdx, _clogIdxPtr

25

26 ' wrap around ?

27 test _clogIdx, _clogMaxIdx wz

28 if_nz jmp #:logdone

29

30 mov _clogIdx, #0

31 mov _clogBufPtr, _clogBufPtrSav

32 :logdone

33 LOG_ret ret

34

35 ...

36

37 ''>>> ADD THESE VARIABLE DECLARATIONS

38 _clogMaxIdx long LOGLEN -1 ' 0 to loglen -1

39 _clogIdx long 0

40 _clogVal long 0

41

42 _clogBufPtr long 0

43 _clogBufPtrSav long 0

44 ...

Listing 11-5

Debugging PASM Code by Sharing a Log Buffer; PASM Code

The LOG subroutine keeps track

of the index into the log array and resets to the start when it reaches the end. It writes the value in _clogVal to the current address in the log array, increments that address, and resets the address to the beginning of the array if needed.

11.4 Bug Fix

The failure at the end of the previous chapter can now be tracked down. By placing the following statements at strategic places, I discovered that I had made a mistake in writing the compression code longs:

mov _clogVal, xxx

call #LOG

When there are 128 samples, the compression code array is 8 longs in length (2 bits per sample). However, I was mistakenly writing a ninth long, which overwrote memory of another array. (As it turns out, this was the packBuf array, but it could have been anything.)

Figure 11-2 shows the compression flowchart again, but I have added a check to the right of “16th samp?” shape. If this is also the last sample, jump out of the loop and finalize.

If, for example, there are exactly 16 samples to compress, the compression code is written only once.

On the first sample to the 15th sample, control flows down from “16th samp?” to “Done?” and then back up to “16th samp?”

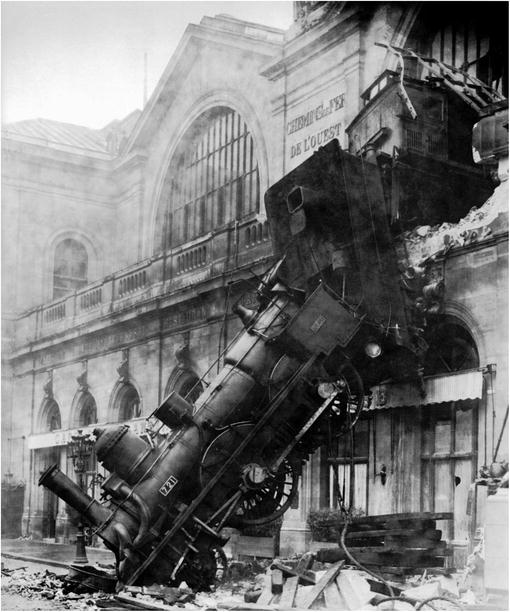

On the last sample, the “16th samp?” query is true, so we go to the right, but the “Done?” query is also true, so we exit the loop and write the compression code at the end (without that question, we would write the compression code twice). In Figure 11-3, we show the consequences of over-running ones bounds!

Figure 11-2

Flowchart for processing samples, with addition of a check for the final sample before writing the compression code. Compare this figure to Figure 9-1

.

PASM code will allow you modify any memory location. There is no checking of array lengths or bounds. It’s all up to you!

Figure 11-3

Train wreck at Gare Montparnasse, Paris, 1895. The train entered the station at a dangerously fast 40–60km/hr, and when the air brake on the locomotive failed, the train crossed the entire concourse (100m) and crashed through a 60cm thick wall before falling to the street below

.