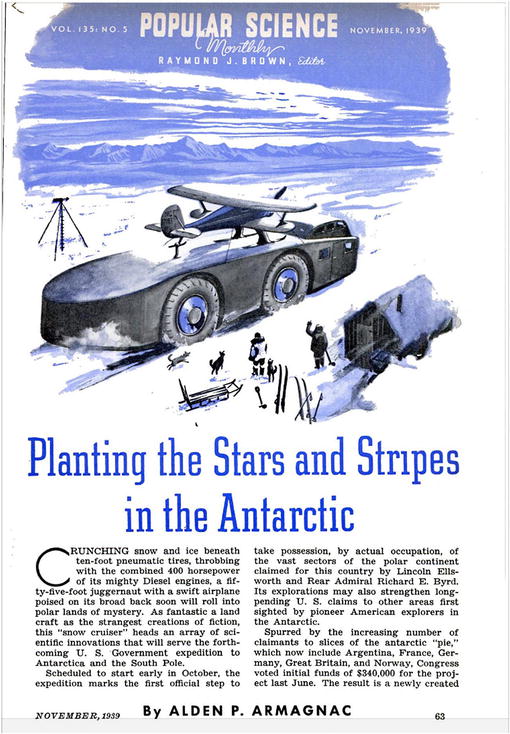

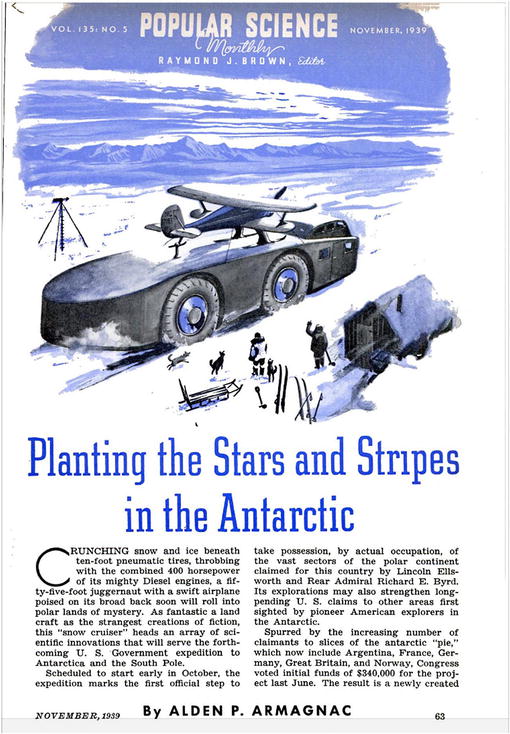

Let’s now look at using PASM and C in the same stretch of code using a technique called inline assembly. You can use this when you require the fastest possible execution of a small section of repeated code. The main part of the code remains in C, but the critical section is written in PASM. In Figure 16-1, there is a drawing of the Antarctic Snow Cruiser: a hybrid exploration vehicle that was ahead of its times.

In this example, we will read the input pin MISO 32 times and shift the value into a variable called val. This is done in SPI (see the previous chapter) where data is transferred serially, one bit at a time.

Here is how we did it in C:

1 // get value of miso pin and put it in low bit

2 bit = (INA & MISOMask) >> MISO ;

3 // shift bit into val

4 val |= bit << j;

If we were to do this in PASM, we would use the following instructions:

1 test ina, misoMask wc ' set C to the miso pin value

2 rcl val, #1 ' rotate val left and set LSB to C

The PASM code is faster because there are only two instructions to perform, but the C code has six: the AND of INA and MISOMask, the right shift by MISO bits, the assign to bit, the assign to j, the left shift by j, and the OR with val.

We can inject the PASM instructions into the middle of the C code to improve performance, as shown in Listing 16-1.

1 ...

2

3 // get value of miso pin and put in low bit

4 // bit = (INA & MISOMask) >> MISO ;

5 // val |= bit << j;

6 __asm__ (

7 " test %[mask], ina wc\n\t"

8 "rcl %[val], #1\n\t"

9 : // outputs

10 [val] "+r" (val)

11 : // inputs

12 [mask] "r" (mask)

13 );

14 ...

Listing 16-1

Modified Version of spiMaster.cogc

That Uses Inline Assembly

- Lines 4–5: The commented-out C version of reading MISO.

- Lines 6–13: The inline assembly injection of the two PASM instructions.

16.1 Inline Assembler

Let’s try to decode that gobbledygook!

The inline assembly has the pattern shown in Listing 16-2.

1 __asm__ (

2 "<pasm instruction>"

3 "<pasm instruction>"

4 : <output variable>,

5 <output variable>

6 : <input variable>,

7 <input variable>

8 );

Listing 16-2

Inline Assembly Format

PASM instructions

are standard instructions, with one difference: any variables you want to use in the instruction are referred to as %[<varname>]. These variables can be shared with the C code. This is done via the output and input sections (after the colons). Each PASM instruction is enclosed in quotes. Successive PASM instructions should not have commas, but they can be on different lines.

You can have more than one input/output variable

separated by commas. Let’s look at lines 7 and 8 in Listing 16-1 in detail.

- test ina, %[miso] wc: test is a PASM instruction with two arguments, and we specify a wc effect. What it does is compare the bit of miso that is high (bit 12) with ina and set the C flag to 1 if ina is 1. The expression %[...] will refer to the variables named in the input and output sections.

- rcl %[val], #1 will shift the variable val left by 1 bit and will shift C into bit 0.

The variables %[miso] and %[val] refer to the variables miso and val in the C code because of these statements (lines 10 and 12 of Listing 16-1):

- [val] "+r" (val) . This says the variable val in the C code should be given the name val in the PASM code so that PASM instructions can refer to %[val]. The "+r" says that this is both an input variable and an output variable. It is modified inside the PASM instructions, and then that modified value is available to the C code.

- [miso] "r" (miso). The "r" says that miso is solely an input variable and isn’t modified in the PASM.

You can refer to the variables by different names in C and in PASM, but why complicate things? (The C variable name is to the right of "+r" in parentheses, and the PASM variable name is to the left of "+r" in square brackets.)

Figure 16-1

Antarctic Snow Cruiser. A hybrid tractor, tank, laboratory, and aircraft carrier for Antarctic exploration intended for use by Admiral Byrd in 1939. Alas, its weight was too much for the snow surface, and it was never used. Popular Science Monthly, v. 135, no. 5, Nov., 1939.

http://bit.ly/2eJOofM

: public domain.

16.2 spiSlave.cogc Inline Assembly

The spiSlave.cogc C code can also be modified to use inline assembly, as shown in Listing 16-3.

1 ...

2 // bit = (val >> j) & 0x01 ; // get jth bit

3 // OUTA ^= (-bit ^ OUTA ) & MISOMask ; // set miso pin of outa to bit

4 __asm__ (

5 "shl %[val], #1 wc\n\t"

6 " muxc outa, %[mask]\n\t"

7 : // outputs (+r) for inputs

8 [val] "+r" (val)

9 : // inputs

10 [mask] "r" (mask)

11 );

12 ...

Listing 16-3

Modified Version of spiSlave.cogc

to Use Inline Assembly

- Lines 2–3: Commented-out C code that set the MISO pin.

- Lines 4–11: Injected PASM code to replace the C code.

- Line 5: shl %[val], #1 wc will set C to the most significant bit of val.

- Line 6: muxc outa, %[mask] will set outa to the value of C at those bit locations specified in mask.

- Line 8 : val is a C variable that will be modified by PASM instructions.

- Line 10: mask is an input variable only; it isn’t modified here.

16.3 Timing

Running this version of the code results in the following:

master id = 1 slave id = 2 sem = 1

Time to read 128 longs = 334128

i=0 data=0

i=1 data=1

...

This is about twice as fast as the C version.

16.4 Summary

The ability to inline PASM code brings an impressive increase in speed while still allowing us to use regular C code for the majority of the work. To use this technique, include an assembler directive at the location where the time-consuming (or bit-twiddling-intensive) code is present.

1 ...

2 // c code here

3 int i, j;

4 i = 12;

5 __asm__ (

6 "mov %[j], %[i]\n\t" // the \n is needed to separate the

7 "add %[j], #42\ n\t" // two instructions. The compiler copies these

8 // verbatim and without the \n it would see

9 // ``mov j, iadd j, #42''

10 // which is a nonsense instruction

11 : /* output variable j is modified in the asm */

12 [j] "+r" (j)

13 : /* input variable i is not modified */

14 [i] "r" (i)

15 )

16 // c code continues

17 // here, i is still 12, but j = 54