THE MURDER OF KATHLEEN PETERSON, 2001

STAIRCASE OF DEATH

A brutal murder? A tragic accident? A bizarre bird strike? The mysterious fate of successful businesswoman Kathleen Peterson whipped up a storm of bitter controversy and wild theorizing that has never abated.

To the outside world, the Petersons had everything: a beautiful home, a loving marriage, and successful careers. Kathleen Peterson earned a six-figure salary with a telecommunications company. Her husband, Michael, was a full-time novelist. This idyllic image was shattered when, in December 2001, Kathleen was found dead at the bottom of a now-infamous staircase in the couple’s North Carolina home. The investigation that followed uncovered lies, adultery and financial woes—and another death at the bottom of a different staircase. It all led to Michael’s eventual conviction, but some believe there’s an altogether different explanation for Kathleen’s death.

Kathleen, 48, and Michael, 58, had both been married before when they met in the mid-1980s. Their meeting was facilitated by their children, who were friends. Kathleen had a teenage daughter named Caitlin. Michael had two sons, Clayton and Todd, from his first marriage, as well as two adopted daughters, named Margaret and Martha.

In 1992, this Brady Bunch-style family moved into a sprawling home on Cedar Street in Durham, North Carolina. Five years later, Michael and Kathleen exchanged vows, making their union official. Caitlin described them as “the most ideal parents.”1

Clockwise: DA Jim Hardin holds up a photo of murder victim Kathleen Peterson at her husband Michael’s 2003 trial; Michael Peterson speaks to reporters after agreeing to an “Alford plea”; SBI agent Duane Deaver explains his blood spatter test to the court; the prosecution compares Kathleen Peterson’s injuries with those of Elizabeth Ratliff.

After moving into the Cedar Street home, Michael started writing columns on city politics for the local newspaper, The Herald-Sun. His increased public profile prompted him to run for mayor—a bid that ended badly following revelations that he had exaggerated his military record. He had claimed he was awarded a Purple Heart after being wounded by shrapnel in Vietnam. In reality, he was awarded the medal after he had been hurt in a car accident. Despite this embarrassment, Michael still hoped to enter the political arena. In 2001, a few months before Kathleen’s death, he ran for City Council, but again, lost. When officials moved so quickly to charge him with his wife’s murder, he wondered if local politics had something to do with it.

A DESPERATE HUSBAND

In the early hours of December 9, 2001, Michael frantically called 911. “My wife had an accident. She’s still breathing,” he cried. “She fell down the stairs. She’s still breathing, please come.”2 Police and medics arrived, but the scene was not as they expected. Michael had said he spent three hours by the pool that night. Yet, although the temperature outside was only around 55°F (12.7°C), all he was wearing were shorts and a T-shirt. Kathleen was lying in a pool of blood at the foot of the stairs. Blood spatter climbed the walls and reached the ceiling. Then came the autopsy findings: Kathleen’s head had been sliced open in places. The medical examiner determined that she had died as the result of a beating, not a fall down the stairs.

December 11, 2001 / Michael Peterson is charged with his wife Kathleen’s murder.

Michael insisted he was innocent. He said that he and Kathleen had been drinking, and that she had also taken a Valium. He could only surmise that the combination of the drug with alcohol made her unsteady on her flip flop-clad feet, causing her to tumble down the wooden staircase. “I’ve whispered her name more than 1,000 times, and I can’t stop crying. I would have never done anything to hurt her,” Michael told reporters outside the Durham County Jail.3

Prosecutors didn’t buy it. While they did find alcohol in Kathleen’s system, the blood alcohol content was only 0.07 percent—below the legal limit to drive in North Carolina. Investigators learned that she had suffered from headaches and dizziness for weeks before her fall and had even lost her vision for a half-hour at one point. Nevertheless, they claimed to have found too much evidence that pointed to Michael as the culprit—including another dead body.

LOOK TO THE PAST

Sixteen years before Kathleen was found dead, a 43-year-old woman named Elizabeth Ratliff died in similar fashion. Ratliff was an American working as a teacher at an airbase near Frankfurt, Germany. She was also a friend of Michael’s, who lived in Germany for a spell with his first wife and two sons. On November 25, 1985, Ratliff died after falling down the stairs. As in Kathleen’s case, there was a lot of blood at the scene. “The blood was all the way up the staircase,” said her friend, Cheryl Appel-Schumacher, who later helped to clean up.4 The authorities had accepted that the death was an accident and that Elizabeth had suffered a brain hemorrhage while climbing the stairs. Michael helped to organize Elizabeth’s funeral and subsequently adopted her daughters.

When North Carolina prosecutors heard of Michael’s proximity to another staircase-related death, they announced that the similarities were too many to be coincidental. “Here I have two cases. Two women that appeared to die the same way. Two women that are associated with Michael Peterson. Lightning don’t strike the same place twice,” Detective Art Holland told a television reporter.5 Elizabeth’s body was exhumed in Texas, and a medical examiner from North Carolina performed a new autopsy. Her verdict: Elizabeth had been beaten to death and the German authorities had overlooked the evidence.

Jim Hardin, the district attorney who prosecuted Peterson, did a great deal of research into the suspect, a lot of which was severely damning. The couple had $143,000 in credit card debt—nearly equal Kathleen’s annual salary. In addition, Kathleen was insured for $1.4 million—which Michael would pocket if her death were accidental.6 Hardin presented a compelling argument that this sum would solve Michael’s financial problems and allow him to “continue to live the affluent, privileged life to which he had been accustomed.”7

“FROM WHAT WE’VE FOUND, EVERY ASPECT OF MIKE PETERSON’S LIFE IS A LIE.”

However, there was another revelation that prosecutors proffered as the most likely murder motive—Michael had been emailing men to solicit sex and had a cache of gay pornography on his computer. Michael had been emailing a man named Brent Wolgamott for sex. Wolgamott testified that he had exchanged about 20 emails with Michael and talked to him on the phone between August 30 and September 5, 2001. He had planned to meet Michael for a rendezvous, but he stood Michael up and never heard from him again. Wolgamott testified that Michael made it clear he was committed to his wife.

“If it’s an idyllic relationship in this marriage, why is he emailing somebody else to meet for sexual relations outside of marriage?” asked Assistant District Attorney David Saacks.9 He suggested that Kathleen could have found the pornographic photos or the sex-soliciting emails on Michael’s computer and confronted him, which would have been a clear motive for Michael to murder her.

BLOOD AND THE BLOW POKE

Hardin pointed to the abundance of blood at the scene as proof Michael was lying about Kathleen’s fate. During the 2003 trial, the prosecutor called to testify Duane Deaver, a State Bureau of Identification (SBI) agent deemed by Judge Orlando Hudson to be an expert in blood spatter evidence. Deaver told jurors that he had conducted a series of experiments that pointed away from Kathleen having accidentally fallen and toward a beating. Michael’s lawyers presented their own blood-spatter expert: Dr. Henry Lee asserted that the blood in the stairwell was, in fact, consistent with a fall. Once Kathleen hit her head, she could have coughed up blood while dazed and staggering. Lee went even further by insisting the amount of blood precluded a beating.

No murder weapon was found at the scene, but prosecutors offered one anyway. Kathleen’s sister Candace had given her a fireplace blow poke as a Christmas gift in 1984. According to pathologist Dr. Deborah Radisch, the 40-inch (101.6 cm) brass tool was the perfect instrument for inflicting the lacerations found on Kathleen’s scalp. The blow poke was found—covered with dead bugs and cobwebs—in a garage during the trial. Hardin questioned a detective who had searched the garage, subtly suggesting that the blow poke had been planted there.

THE FIGHT GOES ON

On October 10, 2003, jurors sided with the prosecution. Michael was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. His adopted daughters—whose mother’s death had been used to prove Michael’s guilt—sobbed in the courtroom, certain of his innocence. Kathleen’s family—including her daughter Caitlin, who had split with her siblings-by-marriage in believing Michael guilty—applauded the conviction.

Michael’s lawyers kept fighting. Throughout the investigation, they had cooperated with a film crew who produced The Staircase, a groundbreaking French television documentary that generated worldwide interest in Michael’s case. Two days after the conviction, they started the appeal process, arguing that evidence connected with Elizabeth’s death never should have been admitted. They challenged Deaver’s testimony and qualifications, arguing that he had exaggerated his credentials during the trial. Their objections fell on deaf ears until 2011, when the agent was fired from the SBI for failing to report blood test results that helped lead to the wrongful murder conviction of an innocent man named Greg Taylor, who spent almost 17 years in prison.

Paulette Sutton—a nationally recognized expert in blood pattern analysis—testified that Deaver’s methods were antiquated and unscientific. According to an Associated Press story, she “chuckled as she watched videos of [Deaver] beating a Styrofoam head and blood-soaked sponge in an attempt to recreate the blood splatters found on Peterson’s shoes and in the stairwell.” Sutton’s testimony helped overturn Michael’s conviction and in 2011, Judge Hudson ruled that Deaver had misled jurors—and that Michael would get a new trial.

Michael spent eight years in prison proclaiming his innocence—but prosecutors still insisted on his guilt. In 2017, facing the prospect of a trial at 73 years old, Michael entered an Alford plea to a manslaughter charge. The plea is treated as a guilty plea for sentencing purposes, but Michael received less than the eight years he had already served. This meant he could walk away a free man. Michael said that taking the Alford plea was the most difficult thing he had ever done, but he believed police and prosecutors “would do anything to convict me. And I am not going to put my life and my freedom in their hands.”10 Prosecutors considered the plea a win. Durham District Attorney Roger Echols stated: “It has always been, and remains today, the State’s position that Michael Peterson is responsible for the death of Kathleen Peterson.”11

OWL ATTACK?

The Staircase documentary unwittingly recruited armchair detectives worldwide to proffer theories explaining what could have happened to Kathleen that night. Most are split between the two scenarios presented at trial: that either Michael killed his wife, or she fell in a manner that caused multiple injuries to her head.

However, the most intriguing theory suggests the case is more a “hoo-dun-it” than a whodunit. In 2003, Larry Pollard, a friend of Michael’s, asked prosecutors to reopen the case because of information that pointed to another culprit altogether: an owl. Looking at autopsy photos, Pollard said that some of the gashes on Kathleen’s body looked like marks from an owl’s exceptionally sharp talons. Pollard consulted with ornithological experts who agreed that the pattern and shape of the cuts on Kathleen’s head looked far more like an owl attack than a fireplace tool.

Hardin dismissed this theory as being completely ridiculous, but owl attacks are not as outlandish as they might seem. Kate Davis, executive director of a wild bird education organization in Florence, Italy, said raptors are known to get aggressive when defending their nests and hatchlings. They tend to attack at night; Michael’s phone call to 911 was at 2:40 a.m. Kathleen was holding clumps of her own hair, mixed with wood splinters and needles from a cedar tree. Could an owl have become entangled in her hair?

When the SBI eventually acknowledged finding a “microscopic feather” on a clump of hair in Kathleen’s hand, Pollard shouted: “The feather has been found!”12 With Michael’s plea agreement, however, the Owl Theory will never have its day in court. Michael himself said he has run out of theories: “The only thing I know absolutely, positively, is that I had nothing to do with Kathleen’s death.”13

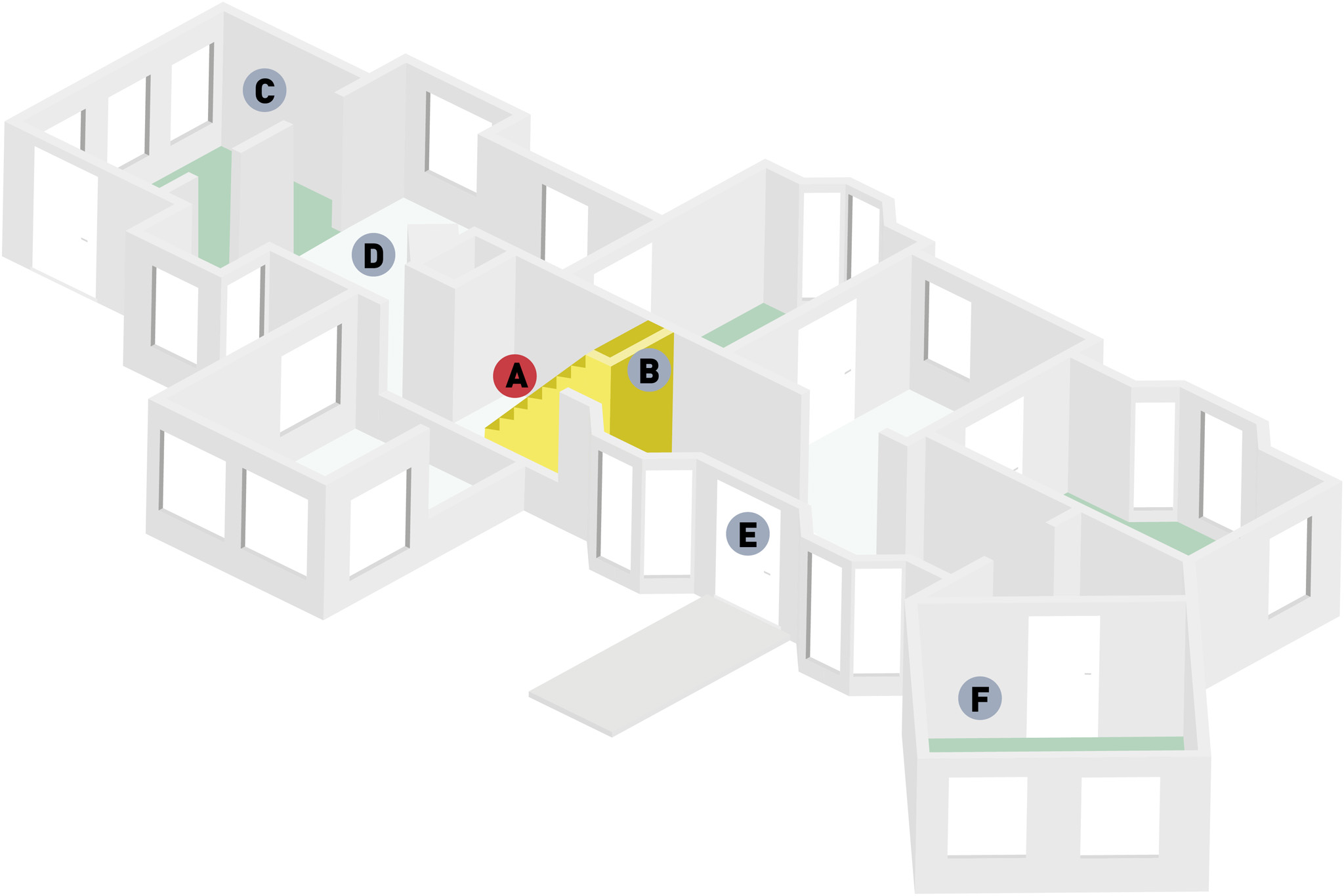

THE MAIN FLOOR

Kathleen Peterson’s body

Kathleen Peterson’s body

Staircase

Staircase

Utility room

Utility room

Kitchen

Kitchen

Front door

Front door

Library/office

Library/office

A paramedic shows the jury how Michael Peterson was holding his wife’s body.