THE MURDER OF LYNNE HARPER, 1959

THE LAST BIKE RIDE

A tragic series of events followed by a biased police investigation resulted in a 14-year-old boy becoming the youngest-ever inmate on Canada’s Death Row.

The murder of Lynne Harper and subsequent arrest of a 14-year-old boy contains many of the hallmarks of a wrongful conviction. The investigation focused on Steven Truscott as the main suspect; evidence was corrupted to look incriminating, and at a time when people had uncritical attitudes toward the justice system, he was convicted of her murder with almost no questions asked. Since then, however, some highly questionable police work has come to light and the science that found the teenager guilty has been thoroughly discredited. But if Steven Truscott was wrongly accused over half a century ago, then who really killed Lynne Harper?

SUMMER BIKE RIDE

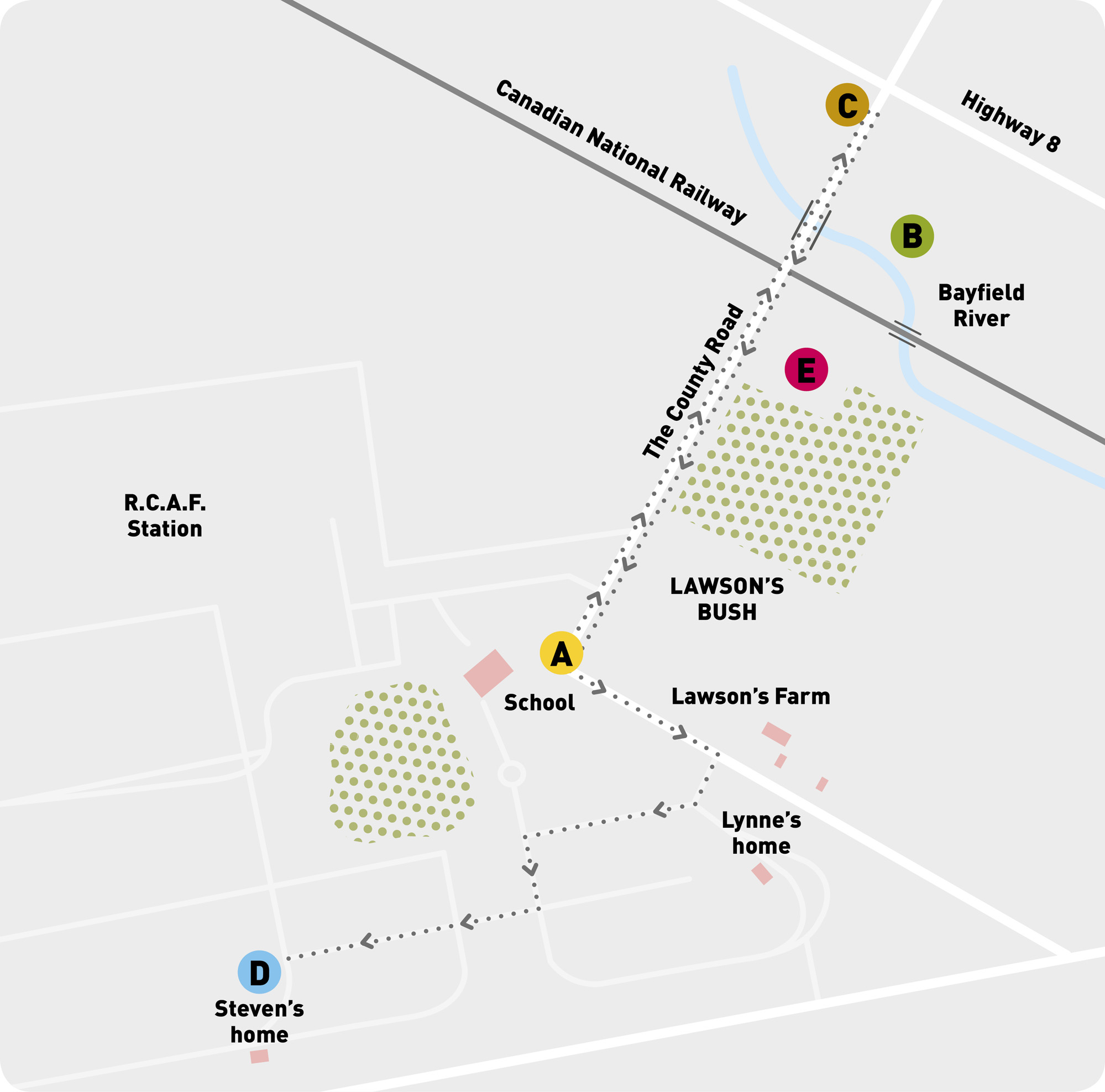

It was the summer of 1959, and Steven Truscott’s father was stationed at Clinton Air Force Base in Clinton, Ontario. The teenager attended the Air Vice Marshal Hugh Campbell School located on the north side of the base. It was here that he met 12-year-old Lynne Harper, the daughter of an officer at the Clinton base. On June 9, 1959, Lynne had dinner with her family before going outside at around 6:15 p.m. It was a pleasant summer evening and the sun had not yet set. According to Steven, he started chatting with Lynne outside their school at around 7:00 p.m. He said that she asked if he could give her a ride on his bicycle to Highway 8, where she planned to hitchhike to a quaint white house just north of the highway. The owner of the house kept ponies and Lynne loved ponies. Steven agreed, Lynne perched herself on the handlebars of his bicycle and off they went. Several witnesses would later state that they spotted the pair biking on a country road running alongside the Bayfield River, a popular spot for swimming and fishing, which was on the way to Highway 8.

Main images: Lynne Harper; the crime scene in Lawson’s Bush.

Top to bottom: Provincial Police Commissioner Harold Graham, who arrested Steven Truscott in 1959; Steven Truscott leaving the Supreme Court after cross-examination in 1966; 14-year-old Steven Truscott after his arrest.

What happened next is the crux of the case. Steven asserts that he dropped Lynne off on Highway 8 and as he glanced back while biking toward Bayfield Bridge, he saw her climb into a “late model Chevrolet” with yellow plates. The car then drove east. Others have argued that, instead, Steven took Lynne into nearby woodland known as Lawson’s Bush, where he raped and strangled her.

DISCOVERING THE BODY

When Lynne didn’t return home that night, her worried father called police to report her missing. A search party was swiftly assembled, and an extensive search for the young girl ensued. Two days later, a search party member from the Clinton base made a terrible discovery in Lawson’s Bush. Partially hidden among the foliage was the semi-naked, lifeless body of Lynne Harper. She had been raped and subsequently strangled to death with her own white, sleeveless blouse, which was still around her pale neck. Her face and chest were dotted with maggots, and larvae had gathered near the buttocks. These gruesome details, ignored at the time, would one day be used as crucial evidence.

The autopsy was conducted in a cramped and poorly lit room at a Clinton funeral home. The regional pathologist, Dr. John Penistan, issued three versions of the autopsy report, all of which had a different time of death. He finally concluded that Lynne had died on June 9 between 7:15 p.m. and 7:45 p.m. The first two autopsy reports declared that she had died after 8:00 p.m., but by the time the third autopsy report was issued, police had announced that Steven Truscott was the main suspect in the slaying. In order for him to become so, the timeline of events had to be tweaked to put the time of Lynne Harper’s murder before 8:00 p.m. This was because Steven had been seen riding his bicycle near the schoolyard at approximately 8:00 p.m. and was home shortly after that time to look after his siblings.

June 12, 1959 / Steven Truscott is arrested for the murder of Lynne Harper.

TEENAGER ON TRIAL

Steven Truscott was arrested and put on trial for the murder of his schoolfriend, strongly protesting his innocence the entire time. The time of Lynne Harper’s death and Steven’s whereabouts remained two key issues at his trial. Ultimately, the courtroom testimony of Dr. Penistan was comparable to a noose tightening around Steven’s neck. The doctor claimed that the murder had occurred between 7:00 p.m. and 7:45 p.m., when Lynne Harper had been in the company of Steven. He based this assertion on the fact that he had found a full meal in Lynne Harper’s stomach, the stomach normally takes two hours to empty, and her last meal had been at 5.45 p.m. Subsequent medical research, however, has shown that the stomach may take up to six hours to empty.

Despite a total lack of physical evidence against him, Steven Truscott was found guilty and sentenced to hang. His death sentence was commuted to life in prison in 1960, the same year that his first appeal was denied. In 1966, the Supreme Court of Canada upheld his conviction; three years later, Steven was released on parole. Following his release, he went on to marry and have three children while living under an assumed name. He kept a low profile until 2000 when his case was featured on the CBC TV investigative program The Fifth Estate, which portrayed the trial as a miscarriage of justice. In 2001, the Association in Defence of the Wrongfully Convicted successfully filed an appeal to have the case reopened.

A QUESTION OF TIMING

In 2006, five judges of the Ontario Court of Appeal began a landmark review of the case and Steven Truscott stood trial once again in a bid to clear his name. Much of the proceedings focused on evidence that was unavailable to his lawyers at his original trial.

Dr. Michael Pollanen, Ontario’s chief pathologist, took the stand to announce that in his opinion, the original pathologist did not have enough evidence to support his finding that Lynne Harper had died within a 45-minute window on the night of June 9, 1959. Dr. Pollanen said that “the time of death window must be broadened to include June 9 and June 10.”1 Blowflies, maggots, and insect activity on the body raised reasonable doubts that she died as early as the original pathologist had determined. During the 1950s, forensic entomology—the study of insects and decomposition—was practically nonexistent. Despite this, the insects were thankfully still collected at the time. Knowing when insects deposit their eggs or larvae on a corpse gives a clearer estimation of the time of death; the maggots and larvae found on Lynne’s body were in the first stage of development. Forensic entomologist Gail Anderson concluded that the insects began to colonize on Lynne’s body on June 10, indicating that she had been killed much later than previously claimed.

Truscott’s story about his last moments with Lynne Harper were also readressed in the Ontario Court of Appeal. During the 1959 trial, Lynne’s parents had insisted that their daughter would never hitchhike, refuting his account. However, Catherine Beamer—who had been a close friend of both Lynne and Steven—stated that hitchhiking was common, and that she and Lynne had done it “at least 15 to 20 times.”

New testimony that harmed the defense came from one of the original witnesses, Karen Daum. In 1959, Daum (who was 9 years old at the time) told police that she had seen Steven and Lynne near the railway tracks—north of Lawson’s Bush—at about 7:15 p.m. However, in 2006, she testified that she had actually seen the pair further south. She recalled that Truscott had veered toward her, causing her to fall off her bike into a ditch south of the trail leading to Lawson’s Bush.

SUSPECTS REVEALED

At the Ontario Court of Appeal, the defense argued that once the local police officers made Steven Truscott their prime suspect, the murder investigation ground to a halt, and other leads and tips were ignored. Several alternative suspects in the case were acknowledged in the court documents but never publicly identified by name. They included a convicted pedophile who was stationed at the Clinton base at the time of the murder. This unidentified man came to the attention of the police in 1997 after a retired officer informed them that he believed the man was capable of murdering a child.

Another suspect was a former salesman who drove a 1957 Chevy and often visited the Clinton base. He first came to police attention when he broke into the home of retired detective Barry Ruhl and assaulted his wife before Ruhl overpowered and arrested him. Ruhl investigated this anonymous man and came to the conclusion that he was a suspect in several murders—including that of Lynne Harper.

Court documents also referred to a convicted rapist who lived in the nearby town of Seaforth and worked as an electrician on the Clinton base. He had visited the Harpers’ home before the murder to repair a clothes dryer. Shortly after Lynne’s murder, he moved to the US, where he was charged with sexual offenses, for which he was acquitted.

THE SUSPECT MINISTER

The fourth suspect mentioned in the documents was a minister who was later accused of sexual assault by his own adult daughters. One of them informed police that when she was 6 years old, she hid in her father’s car when he took it out for a drive. She claimed that he stopped on a gravel road and opened the trunk. She peeked out of the window and allegedly saw him carrying the body of a girl toward some trees. About half an hour later, he returned to the car alone.

The final suspect—and the only other one to ever be publicly identified—was an airman who had once been stationed at Clinton base. At the time of the crime, he was stationed at Aylmer and had a home in Seaford. He was an alcoholic with psychiatric problems and a sexual interest in children. Twelve days before Lynne Harper was murdered, he was released after being arrested for attempting to lure little girls to his car in nearby St. Thomas. This suspect would later be identified as Sgt. Alexander Kalichuk, who had passed away in 1975.2 Many Clinton residents believe that the military deflected blame for Lynne Harper’s murder to protect its reputation and, as evidence, point to the disappearance of military records from 1959.

THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE

In August 2007, Steven Truscott was acquitted of all charges. His defense team wanted him to declared “factually innocent,” but the court ruled that was impossible because “in a case of circumstantial evidence like this, there is certainly nothing on this record that would lead you to the conclusion that he’s factually innocent.”3 It is rare for a defendant to be declared innocent after being found guilty unless there is DNA evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that another person perpetrated the crime. It was a long-awaited ending and most observers were satisfied with the outcome, altough, as Steven pointed out: “The Crown had most of this information 48 years, two months, and 19 days ago.”4 Steven remained highly critical of the legal system that had put him through so much.

“THE CROWN CHOOSES TO NOT THINK ABOUT JUSTICE. IT WOULD ALMOST APPEAR THEY’RE MORE INTERESTED IN CONVICTIONS.”

On that hot summer’s evening in 1959, Steven Truscott and Lynne Harper—perched precariously on his handlebars—biked away from their school, onto the highway, and into Canadian legal history. Any retrial is now unlikely, owing to the amount of time that has passed. Most of those involved in the case are long since dead and evidence has been lost or destroyed. The murderer that robbed Lynne Harper of her life also robbed Steven Truscott of his childhood and left him living under a cloud of suspicion for nearly half a century.

STEVEN’S MOVEMENTS

Steven and Lynne meet at school at about 7 p.m.

Steven and Lynne meet at school at about 7 p.m.

Location of witnesses who see Steven and Lynne bike across bridge

Location of witnesses who see Steven and Lynne bike across bridge

Location that Steven claims Lynne entered Chevrolet

Location that Steven claims Lynne entered Chevrolet

Steven arrives home just after 8 p.m.

Steven arrives home just after 8 p.m.

Lynne’s body found on June 11

Lynne’s body found on June 11

Stakes mark the location of Lynne Harper’s body at Lawson’s Bush.